Abstract

We explore the potential and limitations of using artificial intelligence to quantify philosophical health. Philosophical health is an approach to well-being defined as the dynamic coherence between thoughts, values, and actions in harmony with the world. As both AI and philosophical practice gain prominence in contemporary life, their intersection raises fundamental questions about measurement, meaning, and human flourishing. To substantiate our analysis, we present the Philosophical Health Compass (PHC), a quantitative instrument designed to assess six dimensions of philosophical wellbeing: bodily sense, sense of self, sense of belonging, sense of the possible, sense of purpose, and philosophical sense. Through analysis of this instrument, we investigate whether philosophical health – traditionally approached through qualitative exploration and dialogue – could meaningfully benefit from AI-assisted quantification. We introduce the C.I.P.H.E.R. Model (Crealectic Intelligence and Philosophical Health for Enriched Realities) as a human-in-the-loop framework for responsible integration of AI in philosophical practice. The article argues that while quantification offers valuable research opportunities, philosophical health assessment must preserve human sovereignty and philosophical pluralism. We conclude that AI can conditionally enhance philosophical health evaluation if implemented within boundaries that maintain the essentially human character of philosophical reflection, suggesting a complementary rather than substitutive relationship between quantitative tools and qualitative dialogue.

1 Introduction

The unstoppable march of AI-powered technologies has led us to a point where the most intimate aspects of human existence – finding or cultivating love, nurturing mental health, and determining career paths – can now be partly automated via apps and algorithms.[1] But what about this most personal matter: philosophical health and self-knowledge? While recent developments in artificial intelligence have shown promising capabilities in areas once thought uniquely human,[2] the question of whether philosophical well-being can be algorithmically measured and enhanced remains both technically intriguing and ethically complex.

The notion of philosophical health has ancient roots reaching back to Socrates’ assertion that “the unexamined life is not worth living” and extending through Hellenistic schools that saw philosophy as a therapeutic practice.[3] This tradition, now often called “philosophy as a way of life,” understood philosophical practice not primarily as abstract theorizing but as a practical discipline oriented toward human flourishing or eudaimonia.[4] In contemporary times, this approach has been revitalized through philosophical counseling,[5] philosophical practice,[6] and critical inquiries into the relationship between wisdom and well-being.[7]

Philosophical health emerges from this tradition as a distinct paradigm, defined as “a state of fruitful coherence between a person’s ways of thinking and their ways of acting” or more fully as “the dynamic adequation between thoughts and actions in a spirit of compossibility with the rest of the world.”[8] Unlike clinical mental health approaches focused on symptom reduction or behavioral modification, philosophical health emphasizes meaning-making, value-coherence, and ethical engagement with oneself and the world.

The suggestion of using AI to assess philosophical health may seem at first glance contradictory to traditional philosophical approaches. Critics have argued that we already expect too much from technology and risk diminishing essential aspects of the human experience.[9] Their concerns echo earlier philosophical traditions that emphasize the irreducibly personal nature of self-knowledge, from Kierkegaard’s subjective truth to Heidegger’s concept of authentic being. After all, philosophical self-knowledge has historically been forged in the crucible of lived experience, relationships, and intimate struggles.

However, recent advances in AI present intriguing possibilities that warrant careful philosophical examination. Large language models have demonstrated capabilities for nuanced dialogue,[10] while pattern recognition algorithms can identify correlations that elude human perception.[11] These technologies raise fundamental questions about the nature of philosophical health and its assessment: Can then philosophical well-being be meaningfully quantified? Should AI play a role in this process? What boundaries must be established to preserve the essentially human character of philosophical reflection?

To address these questions, this article examines the Philosophical Health Compass (PHC), a new quantitative assessment tool designed by Luis de Miranda in dialogue with colleagues from the Philosophical Health International research group to complement his qualitative SMILE_PH methodology (Sense-Making Interviews Looking at Elements of Philosophical Health). The PHC evaluates six dimensions of philosophical health: bodily sense, sense of self, sense of belonging, sense of the possible, sense of purpose, and philosophical sense.[12] By analyzing this instrument within the broader context of AI and philosophical practice, we investigate both the promises and perils of quantifying philosophical well-being.

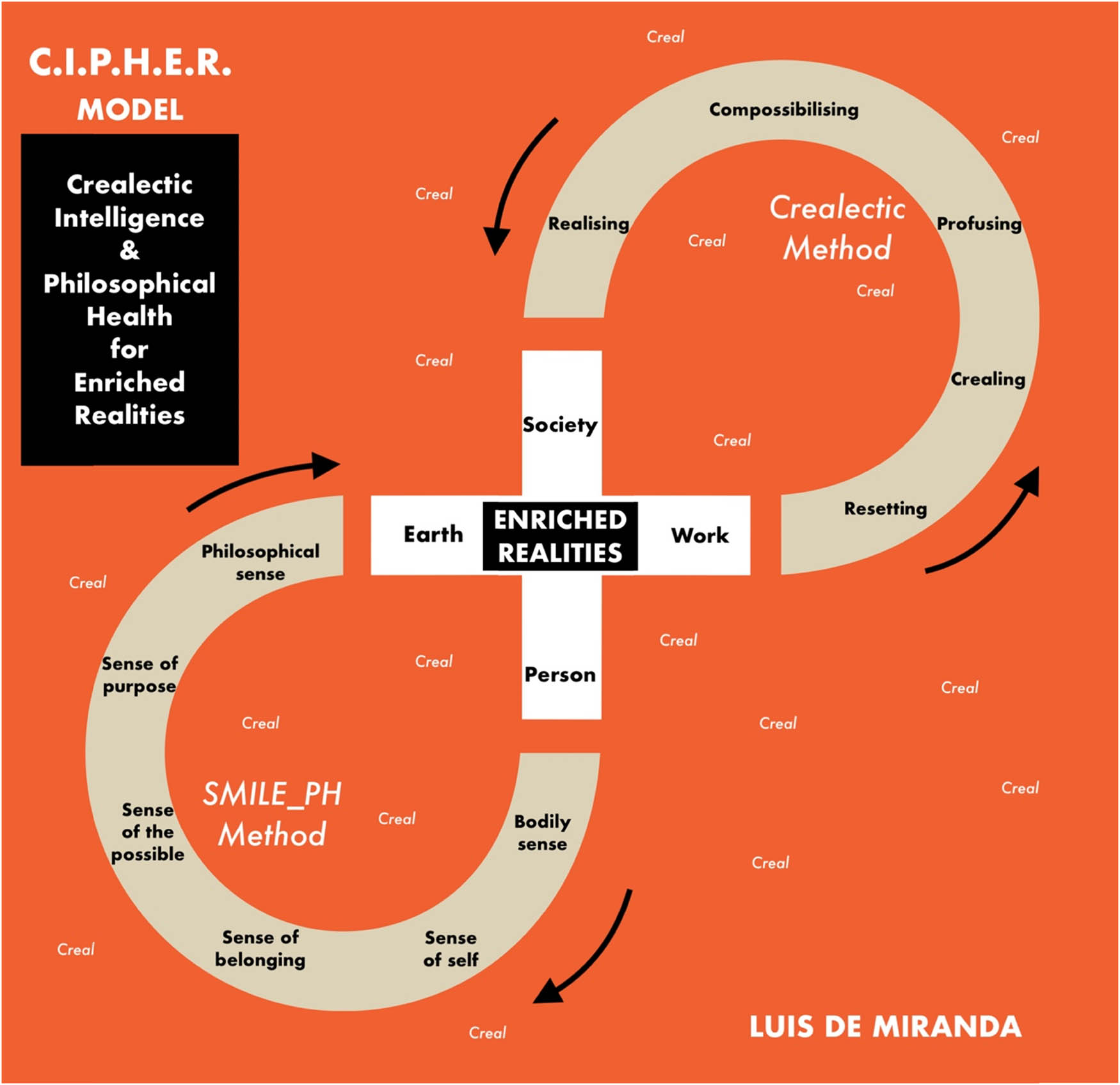

Our investigation proceeds through several interconnected inquiries: First, we explore the conceptual foundations of philosophical health, distinguishing it from clinical approaches and establishing its six dimensions. Second, we examine the philosophical problem of measurement and quantification in relation to wisdom and well-being. Third, we analyze the Philosophical Health Compass as a specific attempt to quantify philosophical health. Fourth, we introduce the C.I.P.H.E.R. Model (Crealectic Intelligence and Philosophical Health for Enriched Realities) as a framework for human-AI collaboration in philosophical practice. Finally, we consider the ethical implications of AI-assisted philosophical health assessment.

Throughout this exploration, we maintain that while technology might enhance our understanding of philosophical health, it should remain in service rather than replacement of human philosophical reflection. The question is not simply whether AI can quantify philosophical health, but whether it should – and if so, under what conditions. As we navigate this terrain, we seek a balanced approach that embraces the potential benefits of technological augmentation while preserving the essentially human character of philosophical wisdom.

2 Philosophical Health: Conceptual Foundations

The concept of philosophical health emerges from a long tradition of viewing philosophy as a therapeutic or transformative practice. From Socrates’ emphasis on self-examination to the Stoics’ philosophical exercises[13] and contemporary philosophical counseling movements,[14] philosophers have recognized that philosophical reflection can contribute to human flourishing in ways distinct from clinical psychological interventions. However, the specific notion of “philosophical health” represents a novel framework for understanding how philosophical practice can enhance human well-being through systematic attention to meaning-making and value-coherence.

Philosophical health can be defined as “the dynamic adequation between thoughts and actions in a spirit of compossibility with the rest of the world.”[15] This definition draws on both ancient and modern philosophical traditions: the concept of adequation echoes classical theories of truth as correspondence (Aquinas), while compossibility derives from Leibniz’s theory of possible worlds.[16] The term “compossibility” refers to the active harmony of possible or actual elements that constitute a coherent world – not everything that is individually possible is “compossible” or compatible within a given system of reality.

This framework aligns with but extends beyond contemporary virtue ethics and philosophical practice. While therapeutic philosophy often focuses on problem-solving or emotional regulation,[17] philosophical health emphasizes the broader goal of achieving what MacIntyre calls “narrative unity” and integrity in one’s life.[18] This unity encompasses not only internal coherence but also what Taylor describes as an orientation within moral frameworks[19] and what Ricoeur terms “ethical aim,” the project of living well with and for others in just institutions or societies.[20]

Unlike clinical approaches that often focus on symptom reduction or behavior modification according to predetermined norms, philosophical health is non-pathological and non-clinical. It recognizes the diversity of philosophical traditions and avoids imposing a singular vision of human flourishing. As Banicki observes, philosophical work, in this way, focuses on the philosophical understanding of our concrete life struggles, purposes, and worldviews.[21]

The relationship between philosophical health and autonomous thinking merits particular attention. As Kant argued, and contemporary scholars have elaborated, genuine thinking requires both the courage to use one’s own understanding and the wisdom to recognize its limits.[22] This doesn’t mean that thinking can be isolated; as Arendt emphasized, thinking is inherently dialogical, even when conducted alone.[23] The practice of philosophical health can be facilitated through philosophical dialogue, within a more or less structured context. But the effort to think is always personal and embodied.

Among the methodologies developed for philosophical counseling, the SMILE_PH method (Sense-Making Interviews Looking at Elements of Philosophical Health) offers a systematic approach to exploring and enhancing philosophical health.[24] This semi-structured dialogue framework builds on established traditions in philosophical practice while incorporating insights from contemporary research in psychology[25] and meaning-making.[26] The method consists of six interconnected elements, each addressing a fundamental aspect of philosophical well-being:

The Bodily Sense begins with embodiment, recognizing what Merleau-Ponty termed the “lived body” as the foundation of human experience.[27] Through phenomenological self-examination, we become aware of our embodied presence in spacetime. This dimension acknowledges what Johnson calls the “meaning of the body” – how bodily experience shapes understanding and values.[28] As Sheets-Johnstone argues, “Movement forms the I that moves before the I that moves forms movement.”[29]

The Sense of Self builds on contemporary theories of selfhood,[30] exploring the reflexive awareness characteristic of human consciousness. This approach integrates insights from both phenomenological traditions[31] and contemporary cognitive science while maintaining a focus on philosophical rather than psychological aspects of self-understanding. As Taylor notes, the self is a potential speaker who exists within “webs of interlocution.”[32]

The Sense of Belonging examines what Heidegger called “being-with” (Mitsein) and what contemporary social philosophers term “social ontology.”[33] Recent research supports the philosophical intuition that belonging constitutes a fundamental aspect of human flourishing,[34] and that, beyond well-being, there can be such thing as well-belonging.[35]

The Sense of the Possible draws on existential philosophy’s emphasis on possibility and project,[36] exploring one’s relationship with potential futures but also potentiality as a source of action. The SMILE_PH method was initially developed through research with individuals living with spinal cord injury, revealing how philosophical health transcends physical limitation.[37] This aligns with Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy while extending it into philosophical dimensions.[38]

The Sense of Purpose engages with what Frankfurt calls “volitional necessity” – the things we can’t help caring about[39] – and what Korsgaard terms “practical identity.”[40] This connects individual purpose to universal ethical principles, echoing Kant’s conception of the categorical imperative.[41]

The Philosophical Sense examines one’s overall worldview or what German Enlightenment figures called Weltanschauung. This continues to involve a critical examination of assumptions and beliefs, similar to what Socrates termed the “examined life,” while integrating our worldview, cosmology, or ideology. This meta-cognitive dimension allows for the integration of the other elements while maintaining awareness of their theoretical foundations.

These six elements work together to promote what Aristotle called eudaimonia – not mere happiness but flourishing through the realization of human potential. The SMILE_PH method has been empirically tested in various contexts, including philosophical counseling, showing promise in both clinical and non-clinical settings.[42] However, its philosophical orientation distinguishes it from purely psychological approaches, maintaining focus on meaning, value, and ethical engagement rather than symptom reduction or behavioral modification.

Understanding philosophical health as distinct from mental health becomes particularly crucial as we consider the role of AI in human flourishing. While AI might assist with certain aspects of psychological well-being through data analysis and pattern recognition, philosophical health involves elements of meaning-making and value-coherence that require first-person reflection – the human cogito (“I think”). This distinction will prove essential as we explore how AI might support rather than supplant philosophical practice.

3 The Question of Quantification

The attempt to quantify philosophical health raises questions about measurement itself and the nature of what we seek to understand. At stake is not merely a methodological concern but a philosophical one: can wisdom, meaning, and philosophical coherence be meaningfully expressed through proportions? This question connects to longstanding debates in the philosophy of science, phenomenology, and ethics regarding the quantification of human experience.

The desire for measurement has deep cultural and intellectual roots. As Heidegger observed, “The fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as picture,” suggesting that modern thinking increasingly frames reality as something to be discretized, calculated, represented, and controlled.[43] More recently, Muller has critiqued what he terms “the tyranny of metrics” – the obsession with quantification that can distort the very values it purports to measure.[44] This tension between qualitative experience and quantitative assessment is particularly acute when examining philosophical health.

Historical attempts to quantify philosophical concepts have often encountered significant challenges. From Bentham’s felicific calculus calculating our amount of pleasure to contemporary measurements of subjective well-being, efforts to assign numerical values to qualitative states face what philosophers call the “commensurability problem” – whether fundamentally different values can be measured on a common scale.[45] As Nussbaum suggests, the plurality of goods cannot be reduced to a single metric without distortion.[46]

Yet, measurement also offers distinct advantages. As Kingma notes, well-designed quantitative tools can reveal patterns across populations that might not be apparent through individual case studies.[47] Moreover, measurement can facilitate comparative analysis, enabling researchers to track changes over time and across different contexts and populations. This potential for systematic knowledge generation makes quantification attractive, despite its philosophical limitations.

The philosophical problem of measurement involves what Husserl called the “mathematization of nature” – the process by which lived experience is translated into mathematical formalism.[48] This process necessarily involves abstraction and reduction, raising questions about what is preserved and what is lost. As Bergson argued, quantification typically involves spatial metaphors that may not adequately capture the temporal, flowing, and continuous nature of lived experience and duration:[49] Life is not discrete in the sense that it is an emergent whole, not its parts only.

In the specific context of philosophical health, quantification faces several distinct challenges. First is what we might call the perspectival problem – philosophical well-being may look radically different according to different philosophical traditions. A stoic conception of flourishing, emphasizing rational control and emotional equanimity, differs markedly from an existentialist emphasis on authenticity, creation, and engagement, or a Buddhist focus on non-attachment and compassion.

Second is the normative problem – measurement implicitly establishes norms against which individuals are evaluated. This raises questions about who determines these norms and whether they inadvertently privilege certain cultural or philosophical perspectives. As Foucault demonstrated, measurement practices are never neutral but always embedded in power relations that shape what counts as “normal” or “healthy.”[50]

Third is the granularity problem – philosophical health involves subtle qualities of experience and reflection that may resist capture through standardized questions. What Wittgenstein called the “fine grain” of experience – in fact not even a grain but a continuous flow – may be lost when translated into numerical scores.[51] This is particularly true for the meta-cognitive aspects of philosophical reflection, where awareness of one’s own thinking processes plays a crucial role. Think about dreams, and how their reality space is continuous in phenomenological, first-person experience rather than in facts.

Despite these challenges, quantification may offer potential benefits for understanding or democratizing philosophical health. First, it provides a structured framework for exploring key dimensions that might otherwise remain implicit or overlooked. As Campbell observes, Measurement involves the explicit statement of rules for assigning numbers to objects to represent quantities of attributes.[52] This critical explicitness can clarify and relativize the conceptual terrain even when the measurement itself is imperfect.

Second, quantification facilitates more systematic research across populations, potentially revealing patterns that would not be visible through individual case studies alone. This broader perspective can help identify common challenges and effective practices that might inform philosophical counseling and education.

Third, quantitative approaches can complement qualitative methods through triangulation – using multiple methods to compensate for the limitations of each. As mixed-methods researchers have argued, integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches often provides richer insights than either approach alone.[53]

The Philosophical Health Compass represents a specific attempt to navigate these tensions by providing a structured quantitative assessment while acknowledging the irreducible qualitative dimensions of philosophical well-being. The compass serves as a complementary assessment tool that prepares for – and does not replace – in-depth semi-structured interviews and enables comparative analysis. This complementary relationship still acknowledges what Merleau-Ponty called the “primacy of perception” – the foundational role of lived experience, shared in the interviews, that precedes, grounds, and prevents any attempt at mere quantification.[54]

Moreover, the integration of AI into this process introduces additional complexity. AI systems excel at pattern recognition and statistical analysis, potentially enhancing the utility of quantitative assessments. Yet they may also amplify the risks of reductionism and standardization that philosophers have long criticized. As Dreyfus argued, AI approaches often fail to capture the “embodied, situated aspect of human intelligence” that is central to philosophical reflection.[55]

The challenge, then, is to develop a dynamic approach that might reduce its normativity by introducing elements of co-creation with the interviewees. Such an approach would recognize the “pharmakon” ambivalent nature of measurement technologies – simultaneously medicine and poison – requiring careful attention to their proper use and limitations.[56] This attention becomes especially crucial when measurement is augmented by artificial intelligence, which may detect patterns and connections beyond human perception while potentially obscuring the very human qualities that philosophical health seeks to nurture.

4 The Philosophical Health Compass: A Quantitative Approach

The Philosophical Health Compass (PHC, as given in Appendix) emerges as a response to the need for more structured and scalable assessment in philosophical health research. While qualitative methods like the SMILE_PH protocol provide rich individual narratives, their limitations in standardization constrain systematic research across populations. The PHC aims to complement these approaches by offering a quantitative framework that can be used alongside in-depth philosophical dialogues.

The development of the PHC followed directly from extensive philosophical counseling practice, which emphasized the pertinence of examining philosophical health through six distinct yet interconnected existential dimensions. The formulation of specific questionnaire items emerged from a systematic analysis of counseling session narratives, where recurring themes and client experiences were synthesized into conceptual constructs while preserving the nuanced nature of philosophical dialogue.

The PHC consists of 48 items, with eight statements corresponding to each of the six dimensions of philosophical health. These statements were crafted to capture alternatively positive and negative aspects of each dimension, allowing for a nuanced assessment of an individual’s philosophical health profile. The questionnaire employs a five-point rating scale – Completely untrue (1), Rarely true (2), Undecided (3), Often true (4), and Completely True (5) – incorporating alternating positive and negative item formulations to mitigate response biases and enhance reliability.

Each dimension is explored through statements that address various aspects of that particular sense. For example, the “Bodily Sense” dimension includes items such as “I feel full of vitality” and “I feel disconnected from nature, both within myself and in my surroundings.” The first statement draws from Bergson’s concept of élan vital and contemporary vitality research,[57] while the second addresses eco-phenomenology[58] and research on nature-connectedness. Together, the eight items provide a comprehensive but not exhaustive assessment of an individual’s relationship with their embodied existence.

Similarly, the “Sense of Self” dimension examines consistency across situations, self-understanding, personal responsibility, and the recognition of strengths or challenges to self-coherence. The statement “I tend to be the same person in all situations,” for instance, addresses the philosophical problem of personal identity persistence, drawing among others from Ricoeur’s concept of narrative identity.[59] Meanwhile, “I take responsibility for shaping who I am” draws among others from Sartre’s existential philosophy of radical responsibility and agency,[60] supported by contemporary research on psychological ownership[61] and personal agency.[62]

The “Sense of Belonging” dimension captures what Heidegger termed Mitsein (being-with) through statements like “I experience meaningful connections with others” and “I maintain my independence while belonging to groups.” These items reflect the fundamental tension between individuation and sociation that Simmel identified as central to social life,[63] as well as what de Miranda terms “well-belonging” – the capacity to participate in community while maintaining individual autonomy.[64]

The “Sense of the Possible” dimension, particularly crucial for philosophical health, includes statements such as “I believe many possibilities exist even in difficult circumstances” and “I turn obstacles into opportunities for enrichment.” These items address what Sartre identified as the fundamental structure of human consciousness – its orientation toward possibilities[65] – and resonate with contemporary research on resilience and post-traumatic growth.[66]

The “Sense of Purpose” dimension explores how individuals develop and maintain meaningful life directions through items like “I am inspired by values that are meaningful to me” and “I remain committed to my chosen purpose even in challenging situations.” These statements connect to Taylor’s concept of “strong evaluation”[67] and Nietzsche’s notion of amor fati, examining how individuals integrate their values into consistent life-affirming projects.

The “Philosophical Sense” dimension serves as both a capstone and meta-perspective, examining an individual’s capacity for conceptual thinking and meaning-making as well as the unveiling of a personal cosmology. Items such as “I notice patterns that help me make sense of life” and “I recognize how my worldview influences my decisions” explore the reflective and integrative aspects of philosophical thinking that allow individuals to make coherent, critical, and systematic meaning of their experiences.

The theoretical grounding of each item is significant, as it connects the quantitative assessment to substantial philosophical traditions and contemporary research which were explored more exhaustively in previous literature on the SMILE_PH method.[68] Each of the 48 statements has been carefully formulated to capture different aspects of philosophical engagement with experience. This careful formulation aims to ensure that the quantitative assessment retains philosophical depth rather than reducing complex existential dimensions to simplistic metrics.

The PHC is designed to be self-administered, with clear instructions provided to respondents regarding the timeframe they should consider when rating each statement. The questionnaire begins with explicit guidance about considering one’s typical recent experience over the past 4–6 weeks, emphasizing the importance of reflecting on how frequently or consistently each statement applies during this standard unit of existence. This timeframe was chosen for specific methodological reasons: it is long enough to identify stable patterns rather than temporary states; it allows for observation across multiple life situations; it is recent enough for accurate recall; and it provides sufficient duration to notice shifts in patterns and allow time for reflection. It also takes into account that the SMILE_PH program of dialogue usually lasts 8 weeks (8 sessions), and therefore a PHC questionnaire could be filled out before and after the in-depth dialogue sessions.

To ensure the questionnaire’s clarity and relevance, a feedback mechanism may accompany the assessment tool, which encourages further self-reflection via co-creation. This document can solicit detailed responses about the comprehensibility of items, the manageability of the questionnaire’s length, respondent engagement, and the personal relevance of the items. This feedback mechanism serves both practical purposes – improving the instrument – and philosophical ones – engaging respondents in the co-reflective assessment of the very means of their philosophical assessment.

Preliminary use of the PHC alongside the SMILE_PH methodology, for instance with 10 students and staff of the Stockholm School of Economics, who went in 2025 through 8 SMILE_PH individual sessions with Luis de Miranda, suggests several potential applications. First, it serves as a complementary assessment tool that prepares for in-depth semi-structured interviews and later enables comparative analysis. The structured format of the questionnaire could facilitate larger-scale studies than are not possible with purely qualitative approaches, potentially enabling researchers to identify patterns and correlations that might not be apparent through individual interviews alone.

Second, it contributes potentially to quantifiable data that makes it easier for researchers to incorporate philosophical health into broader health and wellbeing frameworks. This integration could help philosophical health show its pertinence alongside more established dimensions of well-being, potentially influencing broader social and healthcare policies.

Third, a standardized tool enables repeated measures over time, facilitating longitudinal research to explore how philosophical well-being evolves, whether it responds to interventions, and whether it correlates with other health or quality-of-life indicators. This temporal dimension is particularly important for understanding philosophical health as a dynamic rather than static quality.

However, these potential benefits must be balanced against the significant risk of normativity. There may not be one unique way of being philosophically healthy, contrary to what the compass might implicitly suggest. This risk is particularly acute when the instrument is combined with artificial intelligence, which may detect patterns and correlations that inadvertently establish normative standards or general imperatives without adequate philosophical reflection on their appropriateness.

The PHC represents a promising step in the development of philosophical health assessment, but its true value will emerge, we think, through its thoughtful integration with qualitative approaches and its careful validation across diverse philosophical traditions and cultural contexts. As with any attempt to quantify complex human experiences, the compass must be used not as a definitive measure but as what Gadamer might call a “horizon” – a perspective that illuminates while acknowledging its own limitations and the existence of other ways of seeing.[69]

5 Artificial Intelligence and Philosophical Practice

The integration of artificial intelligence into philosophical practice represents a frontier rich with both promise and peril. As AI systems become increasingly sophisticated in language processing, pattern recognition, and even conceptual reasoning, the question arises: what role should these technologies play in the domain of philosophical health? This question requires careful examination of the nature of AI intelligence, its relationship to human philosophical reflection, and the conditions under which human–AI collaboration might enhance rather than diminish philosophical practice.

Understanding the differences between human and artificial intelligence is crucial for this examination. As I have argued elsewhere, a good strategy to distinguish natural intelligence from artificial intelligence is to distinguish between three modes of intelligence: analytic, dialectic, and crealectic.[70] Analytic intelligence excels at logical decomposition and systematic analysis but may fall prey to what Whitehead termed the “fallacy of misplaced concreteness” – mistaking abstract models and labels for concrete reality.[71] Dialectical intelligence engages with the interplay of opposing viewpoints and the synthesis of contradictions but can be limited by power dynamics and emotional investment in established or binary positions. Crealectic intelligence, by contrast, emphasizes generative potential and multiplicity of becoming rather than mere analysis or opposition, focusing on creating new compatible possibilities (compossibilities).

Most current AI systems excel primarily at analytical and, to some extent, dialectical intelligence. Large language models can process vast amounts of text, identify patterns, and even simulate dialectical reasoning through the synthesis of multiple perspectives. However, they typically lack a first-person relationship to the “Creal” – an abbreviation for Creative Real, representing the dynamic generative potential inherent in reality.[72] This limitation becomes particularly significant when considering philosophical health, which involves not just analysis of existing patterns but openness to emergent and embodied possibilities and creative meaning-making.

The distinction between automation and human cognition further illuminates the challenges of integrating AI into philosophical practice. As Dreyfus argued, human expertise involves embodied, situated understanding that resists formalization in algorithmic terms.[73] This embodied dimension is central to philosophical health, particularly in the bodily sense dimension that recognizes our physical being as the foundation of experience. AI systems, lacking embodied and first-person existence, may miss this crucial aspect of philosophical health.

However, the relationship between automation and human cognition is more complex than simple opposition. Contemporary cognitive science suggests that many mental processes we consider uniquely human may involve forms of natural automation – what Kahneman calls “System 1” thinking.[74] We may be more automated by social rules, beliefs, habits, or language than traditional accounts suggest, yet we also possess unique capacities for self-reflection, radical creativity, and sense-making that transcend mechanical computation.

This nuanced understanding suggests that AI might complement human philosophical reflection by supporting certain cognitive processes while leaving space for distinctively human forms of intelligence. Our C.I.P.H.E.R. Model (Crealectic Intelligence and Philosophical Health for Enriched Realities) offers a framework for conceptualizing this complementary relationship. This model is not incompatible with a collaborative – cogenerative – relationship between humans and AI, ensuring that technology serves to enrich rather than supplant the human creative practive of self-understanding (Figure 1).

The CIPHER model and its 2 methods: SMILE_PH and Crealectics.

The CIPHER Model unfolds through several interconnected components, beginning with the recognition that philosophical health involves six dimensions that resist full automation. These dimensions, the same as in the SMILE_PH method – bodily sense, sense of self, sense of belonging, sense of the possible, sense of purpose, and philosophical sense – each involve forms of understanding that require embodied, emotionally engaged human reflection. AI systems might assist in analyzing certain aspects of these dimensions but cannot replace the lived experience and the first-person singular experience at their core.

Compossible with the CIPHER Model is therefore the concept of “human-in-the-loop” (HITL) implementation, where AI systems serve as tools under human guidance. By incorporating human judgment and expertise throughout the process, HITL systems achieve greater accuracy, reliability, and ethical alignment than AI operating in isolation. This human oversight becomes particularly crucial in addressing ethical concerns surrounding the use of AI in personal development.

The practical implementation of this framework involves integrating two distinct but complementary methodologies: the SMILE_PH method and the Crealectic Method. While the SMILE_PH method provides a structured approach to exploring philosophical health through dialogue, the Crealectic Method offers a systematic process for fostering creative thinking and meaningful innovation.

The Crealectic Method unfolds through five interconnected stages, each building upon the previous while maintaining flexibility for individual variation.[75] These stages begin with Resetting, where practitioners intentionally create mental space by approaching a state of tabula rasa through philosophical meditation or mindfulness exercises. This preparatory phase allows for deeper engagement with the creative potential inherent in reality, what is termed Crealing (Step 2). From this foundation of openness and possibility, the method proceeds to Profusing, encouraging the free and uncensored expression of ideas beyond conventional limitations or judgments. This generative phase leads naturally to Compossibilizing (step 4), where practitioners identify and integrate compatible elements from the profusion of possibilities and ideas. The final stage, Realizing, bridges theoretical insight and practical implementation, ensuring that creative ideas manifest in meaningful action. This is described in detail in a forthcoming book titled Crealectics as a Creative Method (de Miranda, Palgrave).

AI systems might support this process in various ways: analyzing text to identify recurring themes or tensions; suggesting connections between different ideas or experiences; or even generating alternative perspectives that prompt human reflection. Crucially, however, creative synthesis and qualitative sense-making remain human activities, with AI serving as a tool rather than a replacement for human wisdom.

The integration of AI into philosophical practice also raises questions about the role of dialogue and intersubjectivity. As Buber emphasized, genuine dialogue involves an I-Thou relationship that transcends instrumental engagement.[76] AI systems, as products of human design, cannot participate in such relationships in the full sense. However, they might facilitate human-to-human dialogue by providing prompts, identifying patterns, or suggesting connections that human participants might otherwise overlook.

Recent research on human-AI collaboration suggests that “centaur systems” – hybrid approaches that combine human and machine capabilities – often outperform either human or AI systems working independently.[77] Applied to philosophical practice, this suggests that AI-augmented philosophical dialogue might enhance certain aspects of the process while preserving the essentially human character of philosophical reflection. But one needs to remember that thinking is a personal, embodied and crealectic human experience that cannot be automated.

The role of AI in relation to the Philosophical Health Compass presents particular opportunities and challenges. AI systems might analyze patterns across large datasets of PHC responses, identifying correlations and suggesting potential interventions. However, such analysis must remain under human oversight to avoid reifying statistical patterns as normative standards. As Taylor reminds us, genuine self-understanding requires engagement with the capacity to reflect critically on the worth of different desires and purposes based on qualitative assessments that may not be influenced by statistical patterns.[78]

The integration of AI into philosophical practice thus requires careful attention to what might be called “philosophical sovereignty” – ensuring that human wisdom and creativity remain central while leveraging technological capabilities to enrich the process of philosophical discovery. This sovereignty is not merely a matter of oversight but of maintaining the conditions for genuine philosophical reflection, which involves elements of embodiment, intersubjectivity, and creative meaning-making that transcend algorithmic processing.

6 Ethical Implications

The integration of artificial intelligence into philosophical health assessment raises ethical questions that extend beyond general concerns about AI ethics. These questions touch upon fundamental aspects of human autonomy, authenticity, and the nature of philosophical understanding itself. Following Vallor’s framework of technological virtue ethics,[79] we must examine not only the immediate practical implications but also the long-term effects on human flourishing and philosophical development.

One primary concern involves “informational autonomy” – the capacity to make independent decisions about one’s informational space.[80] In the context of philosophical health, this raises questions about how AI systems might influence or shape users’ self-understanding and what we may call autology (the autonomous and personal logic of one’s life). While AI can provide valuable insights through pattern recognition and data analysis, there is a risk of what Frischmann and Selinger call “techno-social engineering” – the subtle shaping of human behavior and mindset through technological systems.[81] This risk becomes particularly acute in philosophical counseling, even if the goal is to enhance rather than diminish human agency.

The issue of data privacy and security in AI-assisted philosophical counseling extends beyond standard cybersecurity concerns. As Nissenbaum argues, privacy must be understood contextually, and philosophical counseling represents a unique context with its own norms and expectations.[82] The intimate nature of philosophical self-exploration demands special consideration of what Manders-Huits calls “moral identification” – the ways in which personal data relate to and potentially affect moral personhood.[83] The collection and analysis of deeply personal philosophical reflections raise questions about data sovereignty and the right to cognitive liberty.[84]

Another crucial ethical consideration involves “volitional necessity,” the relationship between our choices and our fundamental values.[85] AI systems trained on large datasets might identify patterns that reflect common human experiences, but this statistical approach risks normalizing rather than illuminating individual philosophical journeys. As Taylor argues, authentic self-understanding requires engagement with “strong evaluation” – the capacity to assess not just our preferences but the worthiness of our preferences themselves.[86]

The potential for AI systems to perpetuate or amplify existing biases takes on special significance in philosophical health contexts. Recent work has highlighted how algorithmic systems can encode and reinforce social prejudices.[87] In philosophical counseling, where questions of identity, meaning, and value are central, such biases could profoundly affect individuals’ self-understanding and development. This concern connects to broader debates about what Medina calls “epistemic injustice” in technological systems.[88]

The question of transparency and explainability in AI systems becomes particularly relevant when dealing with philosophical self-understanding. While recent work on explainable AI[89] has made progress in making algorithmic decisions more interpretable, philosophical health requires a deeper form of understanding that goes beyond mere explanation of system outputs. This connects to what Heidegger identified as “the question concerning technology” – how technological frameworks shape our understanding of ourselves and our world.[90]

Recent research on AI’s role in moral enhancement[91] and ethical guidance[91] suggests both opportunities and risks in using AI for philosophical development. While AI systems might help identify ethical inconsistencies or blind spots in our thinking, there is a risk of what Borgmann calls “device paradigm” – the tendency to treat complex human problems as merely technical challenges requiring technological solutions.[93]

The impact on human-to-human relationships in philosophical counseling also requires careful consideration. Drawing on Buber’s distinction between I-It and I-Thou relationships,[94] we must consider how AI mediation might affect the quality of philosophical dialogue. While AI may in some cases facilitate certain aspects of philosophical reflection, it should not diminish what Arendt called “human plurality,” the unique capacity for meaningful human interaction and diversified understanding.[95] As Schütz observed, The world of We is common world, intersubjectively shared.[96]

Cultural considerations present another significant ethical challenge. The PHC has been developed within a primarily – but not only – Western philosophical framework, and its applicability across different cultural contexts requires careful examination. The very concepts underlying each dimension may be understood differently in various cultural traditions. As Nussbaum warns, we must be careful not to allow a concern with universal form to obliterate our sensitivity to difference.[97] This concern becomes especially acute when AI systems trained primarily on Western philosophical texts are applied in diverse cultural contexts.

Moreover, there is a risk of excessive normativity in AI-assisted philosophical health assessment, which may conflict with the openness of the semi-structured SMILE_PH method of dialogue. This is why combining the quantitative assessment with qualitative dialogue is essential to preserve individuality and discursive freedom. Ignoring the SMILE_PH dialogues to favor only the questionnaire would damage the spirit of philosophical counseling, which focuses on people’s discursive freedom, experiential uniqueness, and cognitive singularity, rather than the statistical aspect of their psychology.

Based on these considerations, we propose several ethical principles for AI integration in philosophical health:

First, the principle of autonomous self-development: AI systems should enhance rather than replace human philosophical reflection. This aligns with what O’Neill calls “principled autonomy,” freedom guided by rational self-legislation rather than mere preference satisfaction.[98] In practical terms, this means that AI should function as a tool under human direction rather than an autonomous guide or authority.

Second, the principle of hermeneutic integrity: AI systems should preserve and enhance users’ capacity for meaningful self-interpretation. This builds for instance on Ricoeur’s concept of narrative identity[99] while acknowledging the role of technological mediation in contemporary self-understanding. AI should support rather than short-circuit the interpretive process through which individuals make sense of their experiences.

Third, the principle of philosophical authenticity: AI assistance should support rather than standardize individual philosophical development. This principle draws on existentialist insights about authentic self-creation while recognizing the social and technological context of contemporary life. As Sherman argues, authenticity is not about isolation from others but about finding one’s own path within socially compatible possibilities.[100]

Fourth, the principle of epistemic humility: AI systems should acknowledge the limitations of algorithmic approaches to philosophical understanding. This connects to what Code calls “epistemic responsibility” – the obligation to recognize and respect the boundaries of different forms of knowledge.[101] AI systems should be designed and implemented with awareness of their fundamental limitations in capturing the full richness of human philosophical experience.

These ethical principles, among others, should inform both the design and implementation of AI systems in philosophical health practices. As we develop new technologies for supporting philosophical development, we must remain mindful of the delicate balance between enhancement and preservation of human flourishing. This is particularly important when powerful technologies like AI enter the intimate domain of self-understanding.

The ultimate ethical question is not whether AI can assist in philosophical health assessment, but whether such assistance serves the fundamental goals of philosophical practice. As Aristotle recognized, the aim of ethics is not knowledge but action – not merely to know what is good but to become good, a person of quality. Similarly, the aim of philosophical health is not merely to understand but to existentially flourish, and technological interventions must be evaluated according to their contribution to this flourishing rather than mere efficiency or technical capability.

7 Conclusion: Toward an Integrated Approach?

The integration of artificial intelligence into philosophical health assessment represents a complex terrain, rich with both promise and peril. Our exploration of the Philosophical Health Compass and the CIPHER Model has revealed both the potential benefits of quantification and AI assistance and the significant challenges they present to the essentially human character of existential creativity and philosophical reflection. As we conclude, we return to our central question: Can and should AI help us quantify philosophical health?

The answer, we suggest, is conditionally affirmative – AI can indeed help quantify aspects of philosophical health, and such collective quantification may prove valuable under certain conditions and within specific boundaries. However, these conditions and boundaries must be carefully established to preserve “philosophical sovereignty” – ensuring that human wisdom and creativity remain central when leveraging technological capabilities to enrich the process of philosophical discovery.

The complementary nature of qualitative and quantitative approaches emerges as a central theme in our analysis. The Philosophical Health Compass serves as a complementary assessment tool that prepares for in-depth semi-structured interviews and enables comparative analysis. This complementarity acknowledges both the value of structured assessment and its inherent limitations. While the PHC offers a framework for systematic evaluation, it cannot capture the full richness of philosophical reflection that emerges through dialogue and lived experience.

Similarly, AI systems offer valuable capabilities for pattern recognition, data analysis, and even the generation of alternative perspectives, but they lack the embodied, situated understanding that characterizes human philosophical reflection. AI should serve as a tool under human direction rather than an autonomous guide or authority in philosophical or existential matters. Metrics are indications that can help a decision or an insight, but they cannot and should not produce the decision automatically, because our decisions are embodied and take place in a shared complex world.

The human-in-the-loop approach outlined in the CIPHER Model offers a promising framework for responsible integration of AI in philosophical practice. By ensuring that human judgment and expertise guide the process throughout, this approach leverages the complementary strengths of human and artificial intelligence while preserving the essentially human character of philosophical reflection. As de Miranda, Ramamoorthy and Rovatsos suggest, such “anthrobotic” systems – in which the human (anthropos) controls and keeps detached from the automation – achieve greater accuracy, reliability, and ethical alignment than AI operating in isolation.[102]

The ethical principles we have sketched – autonomous self-development, hermeneutic integrity, philosophical authenticity, and epistemic humility – could provide, once thoroughly explored and tested, guideposts for navigating this complex terrain. These principles acknowledge both the potential benefits of technological assistance and the fundamental importance of preserving human agency and diversity in philosophical development. They suggest that AI integration, if any, should be approached not as a replacement for human philosophical practice but as an enrichment of it under certain conditions.

Looking toward future developments, several research directions emerge as particularly promising. We need more fieldwork on the effectiveness of AI-assisted philosophical counseling. Additionally, comparative studies between traditional philosophical counseling and AI-assisted approaches could illuminate both the possibilities and limitations of technological integration. The effectiveness of an anthrobotic model in promoting philosophical health and self-knowledge requires further investigation through large-scale studies. Additional research should examine the model’s effectiveness across different cultural contexts and philosophical traditions. Future deployments in developing AI-assisted philosophical counseling tools will provide valuable insights into the practical implementation challenges and opportunities.

It is our claim that thoughtful philosophical practice should be practiced in a personal (or inter-personal) and embodied manner to enhance human capabilities for self-understanding, existential creativity, and meaning-making. The key lies in maintaining philosophical sovereignty – ensuring that human wisdom and biographical authorship remain central when leveraging technological capabilities to enrich the process of reality enrichment and philosophical discovery.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank the members of Philosophical Health International, in particular Christian Funke, Sena Arslan, Jonathan Eric Carroll, Rodney King, Caroline S. Gould, and Charlotta Ingvoldstad Malmgren for their help and feedback in elaborating the PHC.

-

Funding information: This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions grant agreement No. 101081293.

-

Author contribution: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the article, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

Appendix

The Philosophical Health Compass (PHC) and Its Evaluation

The following questionnaire is meant as a complement to the SMILE_PH protocol of dialogue and counseling (Sense-Making Interviews Looking at Elements of Philosophical Health).

Please respond to each statement based on your typical recent experience – how it has generally felt for you in the last 4–6 weeks. Think about how true each statement is for you based on how frequently or consistently it applies to you within this recent period.

Rating Scale:

Completely untrue (1),

Rarely true (2),

Undecided (3),

Often true (4),

Completely True (5)

Bodily Sense

I feel full of vitality.

I feel discomfort with my body.

I experience my body as a source of joy.

I don’t feel grateful for being in my body.

I am aware of and act on my body’s signals.

I feel disconnected from nature, both within myself and in my surroundings.

I move with fluidity around the physical world.

I find it difficult to gain insights from my body’s experiences.

Sense of Self

I tend to be the same person in all situations.

I struggle to recognize what makes me unique.

I believe I understand myself deeply.

I am confused about certain aspects of myself.

I take responsibility for shaping who I am.

I find it difficult to recognize my inner wisdom.

I achieve success while staying true to who I am.

I find it challenging to differentiate my strengths from my weaknesses.

Sense of Belonging

I experience meaningful connections with others

I feel disconnected from the communities around me.

I feel a strong sense of connection to the shared human experience.

I struggle to feel connected to something greater than myself.

I consider life in general as a familiar domain.

I struggle to balance time for myself with time spent connecting with others.

I maintain my independence while belonging to groups.

I don’t feel free to express my thoughts in groups.

Sense of the Possible

I believe many possibilities exist even in difficult circumstances.

I doubt my potential to create positive change in my life.

I recognize opportunities beyond current limitations.

I avoid engaging with creative challenges.

I turn obstacles into opportunities for enrichment.

I find it difficult to recognize opportunities in uncertain situations.

I believe in our shared ability to create positive change.

I struggle to balance new opportunities with existing responsibilities.

Sense of Purpose

I am inspired by values that are meaningful to me.

I lack a strong sense of purpose or direction in life.

I remain committed to my chosen purpose even in challenging situations.

I sense that my goals are focused primarily on my own success.

I can clearly articulate my higher purpose.

I find it difficult to align my actions with my ideals.

I make an effort to understand other people’s purposes.

I do not consider how my purpose benefits others.

Philosophical Sense

I face problems via conceptual thinking.

I don’t think about situations from a holistic perspective.

I notice patterns that help me make sense of life.

I rarely consider diverse perspectives when making decisions.

I link my daily actions to broader principles and values.

I struggle to make meaning out of my experiences.

I recognize how my worldview influences my decisions.

I struggle to stay reflective during challenging moments.

Feedback Document

Thank You! We greatly appreciate your participation in this questionnaire. Your feedback is invaluable in helping us refine and improve the scale for clarity, accuracy, and effectiveness.

Please take a few minutes to provide your honest thoughts and insights on the items you just completed.

Section 1: General Feedback

Overall Clarity

Were the items easy to understand?

☐ Yes

☐ No (If no, please specify which items were unclear and why.)

Length of the Scale

Did you find the number of items manageable?

☐ Too short

☐ Just right

☐ Too long

Engagement

Did you feel engaged while completing the scale?

☐ Yes

☐ No (If no, please explain why.)

Relevance

Did the items feel relevant to your personal experiences?

☐ Yes

☐ No (If no, please specify which items felt irrelevant and why.)

Section 2: Item-Specific Feedback

For each section of the scale, please note if any items were:

Confusing: The meaning was unclear or ambiguous.

Redundant: Too similar to other items.

Uncomfortable: Made you feel uncomfortable answering.

Bodily Sense

Did any item stand out as unclear or confusing? If so, please specify:

Were there any items that felt repetitive? Please list:

Sense of Self

Were there any items you found difficult to answer? If so, which ones and why?

Did any item feel irrelevant to your experience? Please explain:

Sense of Belonging

Were there items that you felt were hard to relate to or unclear?

Did any item feel unnecessary? If so, which one(s)?

Sense of the Possible

Did you find all items meaningful and clear?

Were there items that could be improved? Please specify:

Sense of Purpose

Were there any items that felt vague or overly broad? Please describe:

Did you feel any aspect of “purpose” was missing or underrepresented?

Philosophical Sense

Did any item in this section feel confusing or overly abstract?

Are there any items you think should be added to better reflect “philosophical sense”?

Section 3: Suggestions for Improvement

Are there any words, phrases, or concepts you think should be clarified or replaced?

Did any of the items feel too extreme or absolute? Please specify:

Are there any areas or topics you feel should be added to the scale?

Do you have any other suggestions for improving the scale?

Section 4: Final Thoughts

What was your overall impression of the Philosophical Health Compass?

Would you recommend any changes to make the questionnaire more engaging or easier to complete?

References

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958.Search in Google Scholar

Arendt, Hannah. The Life of the Mind. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.Search in Google Scholar

Banicki, Konrad. “Philosophy as Therapy: Towards a Conceptual Model.” Philosophical Papers 43:1 (2014), 7–31. 10.1080/05568641.2014.901692.Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, Albert. “Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84:2 (1977), 191–215. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, Albert. “Toward a Psychology of Human Agency.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 1:2 (2006), 164–80. 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x.Search in Google Scholar

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology. Cambridge: Polity, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2004. (Original work published 1912).Search in Google Scholar

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution, translated by A. Mitchell, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. (Original work published 1907).Search in Google Scholar

Borgmann, Albert. Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Gregory and Yual Chiek. Leibniz on Compossibility and Possible Worlds. New York: Springer, 2016.10.1007/978-3-319-42695-2Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Charles S. and Ted Toadvine. (Eds.). Eco-phenomenology: Back to the Earth Itself. Albany: SUNY Press, 2003.10.1353/book4634Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Tom B., Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, and Dario Amodei. “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020), 1877–901.Search in Google Scholar

Buber, Martin. I and Thou, translated by W. Kaufmann, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970. (Original work published 1923).Search in Google Scholar

Bublitz, Jan Christoph. “My Mind is Mine!? Cognitive Liberty as a Legal Concept.” In Cognitive Enhancement, 233–64. Dordrecht: Springer, 2013. 10.1007/978-94-007-6253-4_11.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Donald T. Methodology and Epistemology for Social Science: Selected Papers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Ruth. Incommensurability, Incomparability, and Practical Reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.Search in Google Scholar

Code, Lorraine. Epistemic Responsibility. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1987.Search in Google Scholar

Danaher, John. Automation and Utopia: Human Flourishing in a World without Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019.10.4159/9780674242203Search in Google Scholar

Derrida, Jacques. “Plato’s Pharmacy.” In Dissemination, translated by B. Johnson, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Dreyfus, Hubert L. What Computers Still Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. MIT Press, 1992.Search in Google Scholar

Durkheim, Émile. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, translated by K. E. Fields, New York: Free Press, 1995. (Original work published 1912).Search in Google Scholar

Floridi, Luciano. The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977.Search in Google Scholar

Frankfurt, Harry G. The Importance of What We Care About. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.10.1017/CBO9780511818172Search in Google Scholar

Frischmann, Brett and Evan Selinger. Re-engineering Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.10.1017/9781316544846Search in Google Scholar

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method, translated by J. Weinsheimer and D. G. Marshall, London: Continuum, 2004. (Original work published 1960).Search in Google Scholar

Gallagher, Shaun. “Philosophical Conceptions of the Self.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4:1 (2000), 14–21. 10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01417-5.Search in Google Scholar

Gunning, David and David W. Aha. “DARPA’s Explainable Artificial Intelligence Program.” AI Magazine 40:2 (2019), 44–58. 10.1609/aimag.v40i2.2850.Search in Google Scholar

Hadot, Pierre. Philosophy as a Way of Life. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Heidegger, Martin. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, translated by W. Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.Search in Google Scholar

Husserl, Edmund. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1970.Search in Google Scholar

James, Ian, Rachel Ardeman-Merten, and Annica Kihlgren. “Ontological Security in Nursing Homes for Older Persons - Person-Centred Care is the Power of Balance.” The Open Nursing Journal 8 (2014), 79–87. 10.2174/1874434601408010079.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Mark. The Meaning of the Body. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

Kasparov, Garry. Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. New York: PublicAffairs, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

Kingma, Elselijn. “Health and Disease: Beyond Normativism and Naturalism.” European Journal for Philosophy of Science 9:2 (2019), 1–15. 10.1007/s13194-019-0245-x.Search in Google Scholar

Korsgaard, Christine M. The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.10.1017/CBO9780511554476Search in Google Scholar

Lahav, Ran and Maria Tillmanns. (Eds.). Essays on Philosophical Counseling. University Press of America, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Lara, Francisco and Jan Deckers. “Artificial Intelligence as a Socratic Assistant for Moral Enhancement.” Neuroethics 13 (2020), 275–87. 10.1007/s12152-019-09401-y.Search in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Alasdair. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Manders-Huits, Noëmi. “What Values in Design? The Challenge of Incorporating Moral Values into Design.” Science and Engineering Ethics 17:2 (2011), 271–87. 10.1007/s11948-010-9198-2.Search in Google Scholar

Marcus, Gary and Ernest Davis. Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust. New York: Pantheon, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Marinoff, Lou. Therapy for the Sane. London: Bloomsbury, 2003.Search in Google Scholar

Medina, José. The Epistemology of Resistance. Oxford University Press, 2013.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929023.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception, translated by D. A. Landes, London: Routledge, 2012. (Original work published 1945).Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis. “On the Concept of Creal: The Politico-Ethical Horizon of a Creative Absolute.” In The Dark Precursor: Deleuze and Artistic Research, edited by P. de Assis and P. Giudici, 510–9. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2017.10.2307/j.ctt21c4rxx.51Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis. Ensemblance: The Transnational Genealogy of Esprit de Corps. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020a.10.3366/edinburgh/9781474454193.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis. “Artificial Intelligence and Philosophical Creativity: From Analytics to Crealectics.” Human Affairs 30:4 (2020b), 597–607. 10.1515/humaff-2020-0049.Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis, Subramanian Ramamoorthy, and Michael Rovatsos. “We Anthrobot: Learning from Human Forms of Interaction and Esprit de Corps to Develop More Diverse Social Robotics.” In What Social Robots Can and Should Do, edited by J. Seibt et al., 323–32. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2016. 10.3233/978-1-61499-708-5-323.Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis. “Introducing the SMILE_PH Method: Sense-making Interviews Looking at Elements of Philosophical Health.” Methodological Innovations 16:2 (2023a), 163–77. 10.1177/20597991231180326.Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis, Rachel Levi, and Athanasios Divanoglou. “Tapping into the Unimpossible: Philosophical Health in Lives with Spinal Cord Injury.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 29:7 (2023b), 1203–10. 10.1111/jep.13859.Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis. Philosophical Health: A Practical Introduction. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2024a.10.5040/9781350405066Search in Google Scholar

de Miranda, Luis. “The Crealectic Method: From Creativity to Compossibility.” Qualitative Inquiry 1:8 (2024b). 10.1177/10778004241226693.Search in Google Scholar

Muller, Jerry Z. The Tyranny of Metrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

Nissenbaum, Helen. Privacy in Context. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression. New York: NYU Press, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

Nussbaum, Martha. The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.Search in Google Scholar

Nussbaum, Martha. The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.Search in Google Scholar

O’Neill, Onora. Autonomy and Trust in Bioethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Crystal L. “Making Sense of the Meaning Literature: An Integrative Review of Meaning Making and Its Effects on Adjustment to Stressful Life Events.” Psychological Bulletin 136:2 (2010), 257–301. 10.1037/a0018301.Search in Google Scholar

Pierce, Jon L., Tatiana Kostova, and Kurt T. Dirks. “Toward a Theory of Psychological Ownership in Organizations.” Academy of Management Review 26:2 (2001), 298–310. 10.2307/259124.Search in Google Scholar

Raabe, Peter B. Philosophical Counselling: Theory and Practice. Westport: Praeger, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

Ricoeur, Paul. Oneself as Another, translated by K. Blamey, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.Search in Google Scholar

Rodríguez-López, Paloma and Jon Rueda. “Should AI be Explainable? Formal Assurance vs Moral Concerns.” AI & Society (2022). 10.1007/s00146-022-01459-w.Search in Google Scholar

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness, translated by H. E. Barnes, New York: Washington Square Press, 1992. (Original work published 1943).Search in Google Scholar

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism is a Humanism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.10.12987/9780300242539Search in Google Scholar

Schütz, Alfred. The Phenomenology of the Social World, translated by G. Walsh and F. Lehnert, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1967.Search in Google Scholar

Searle, John R. Making the Social World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Seligman, Martin E. P. Flourish. New York: Free Press, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

Sheets-Johnstone, Maxine. The Primacy of Movement (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2011.10.1075/aicr.82Search in Google Scholar

Sherman, Nancy. The Fabric of Character: Aristotle’s Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

Simmel, Georg. On Individuality and Social Forms, edited by D. N. Levine, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971. (Original work published 1908).Search in Google Scholar

Sticker, Martin. “Kant on Thinking for Oneself and with Others – The Ethical a Priori, Openness and Diversity.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 55:6 (2021), 949–65. 10.1111/1467-9752.12596.Search in Google Scholar

Sullivan, Roger J. “The Categorical Imperative.” In Immanuel Kant’s Moral Theory, 149–64. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.10.1017/CBO9780511621116.012Search in Google Scholar

Tashakkori, Abbas and Charles Teddlie. (Eds.). Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010.10.4135/9781506335193Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.Search in Google Scholar

Tedeschi, Richard G. and Lawrence G. Calhoun. “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence.” Psychological Inquiry 15:1 (2004), 1–18. 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01.Search in Google Scholar

Tiberius, Valerie. The Reflective Life: Living Wisely with our Limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199202867.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why we Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

Vallor, Shannon. Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190498511.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Free Press, 1978.Search in Google Scholar

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations, translated by G. E. M. Anscombe, P. M. S. Hacker, and J. Schulte, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. (Original work published 1953).Search in Google Scholar

Youyou, Wu, Michal Kosinski, and David Stillwell. “Computer-based Personality Judgments are more Accurate than those Made by Humans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112:4 (2015), 1036–40. 10.1073/pnas.1418680112.Search in Google Scholar

Zahavi, Dan. Subjectivity and Selfhood. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.10.7551/mitpress/6541.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special issue: Sensuality and Robots: An Aesthetic Approach to Human-Robot Interactions, edited by Adrià Harillo Pla

- Editorial

- Sensual Environmental Robots: Entanglements of Speculative Realist Ideas with Design Theory and Practice

- Technically Getting Off: On the Hope, Disgust, and Time of Robo-Erotics

- Aristotle and Sartre on Eros and Love-Robots

- Digital Friends and Empathy Blindness

- Bridging the Emotional Gap: Philosophical Insights into Sensual Robots with Large Language Model Technology

- Can and Should AI Help Us Quantify Philosophical Health?

- Special issue: Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic, edited by Graziana Ciola (Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands), Milo Crimi (University of Montevallo, USA), and Calvin Normore (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) - Part II

- The Power of Predication and Quantification

- A Unifying Double-Reference Approach to Semantic Paradoxes: From the White-Horse-Not-Horse Paradox and the Ultimate-Unspeakable Paradox to the Liar Paradox in View of the Principle of Noncontradiction

- The Zhou Puzzle: A Peek Into Quantification in Mohist Logic

- Empty Reference in Sixteenth-Century Nominalism: John Mair’s Case

- Did Aristotle have a Doctrine of Existential Import?

- Nonexistent Objects: The Avicenna Transform

- Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic: Afterword

- Special issue: Philosophical Approaches to Games and Gamification: Ethical, Aesthetic, Technological and Political Perspectives, edited by Giannis Perperidis (Ionian University, Greece)

- Thinking Games: Philosophical Explorations in the Digital Age

- On What Makes Some Video Games Philosophical

- Playable Concepts? For a Critique of Videogame Reason

- The Gamification of Games and Inhibited Play

- Rethinking Gamification within a Genealogy of Governmental Discourses

- Integrating Ethics of Technology into a Serious Game: The Case of Tethics

- Battlefields of Play & Games: From a Method of Comparative Ludology to a Strategy of Ecosophic Ludic Architecture

- Special issue: "We-Turn": The Philosophical Project by Yasuo Deguchi, edited by Rein Raud (Tallin University, Estonia)

- Introductory Remarks

- The WE-turn of Action: Principles

- Meaning as Interbeing: A Treatment of the WE-turn and Meta-Science

- Yasuo Deguchi’s “WE-turn”: A Social Ontology for the Post-Anthropocentric World

- Incapability or Contradiction? Deguchi’s Self-as-We in Light of Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity

- The Logic of Non-Oppositional Selfhood: How to Remain Free from Dichotomies While Still Using Them

- Topology of the We: Ur-Ich, Pre-Subjectivity, and Knot Structures

- The WE-turn and the Ecology of Agency: Biosemiotic and Affordance-Theoretical Reflections

- Listening to the Daoing in the Morning

- The “WE-turn” in Jazz and Cognition: From What It Is, to How It Happens

- Cycling Conditions – Conditionalism About the Mind and Deguchi’s We-Turn

- Research Articles

- Being Is a Being

- What Do Science and Historical Denialists Deny – If Any – When Addressing Certainties in Wittgenstein’s Sense?

- A Relational Psychoanalytic Analysis of Ovid’s “Narcissus and Echo”: Toward the Obstinate Persistence of the Relational

- What Makes a Prediction Arbitrary? A Proposal

- Self-Driving Cars, Trolley Problems, and the Value of Human Life: An Argument Against Abstracting Human Characteristics

- Arche and Nous in Heidegger’s and Aristotle’s Understanding of Phronesis

- Demons as Decolonial Hyperobjects: Uneven Histories of Hauntology

- Expression and Expressiveness according to Maurice Merleau-Ponty

- A Visual Solution to the Raven Paradox: A Short Note on Intuition, Inductive Logic, and Confirmative Evidence

- From Necropower to Earthly Care: Rethinking Environmental Crisis through Achille Mbembe

- Realism Means Formalism: Latour, Bryant, and the Critique of Materialism

- A Question that Says What it Does: On the Aperture of Materialism with Brassier and Bataille

Articles in the same Issue

- Special issue: Sensuality and Robots: An Aesthetic Approach to Human-Robot Interactions, edited by Adrià Harillo Pla

- Editorial

- Sensual Environmental Robots: Entanglements of Speculative Realist Ideas with Design Theory and Practice

- Technically Getting Off: On the Hope, Disgust, and Time of Robo-Erotics

- Aristotle and Sartre on Eros and Love-Robots

- Digital Friends and Empathy Blindness

- Bridging the Emotional Gap: Philosophical Insights into Sensual Robots with Large Language Model Technology

- Can and Should AI Help Us Quantify Philosophical Health?

- Special issue: Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic, edited by Graziana Ciola (Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands), Milo Crimi (University of Montevallo, USA), and Calvin Normore (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) - Part II

- The Power of Predication and Quantification