Abstract

Deguchi’s Self-as-We aims to vindicate a holistic conception of self by working out the implications of what it is to be an agent in light of the East Asian tradition. This is reminiscent of the late Nishida’s philosophy, which also presented a holistic notion of self by way of explicating the logical structure of the world in which subjects are fundamentally agents. Despite these basic resemblances, however, their overall outlooks are markedly different. What are the essential differences? We shall identify them as rooted in the metaphilosophical dimension and suggest that these can best be captured in terms of the role of contradiction. Deguchi’s approach is constructive and parsimonious in that he starts with his thesis of fundamental incapability and builds up his system by adding only those theses strictly necessary to propound his system. For this reason, Deguchi remains silent as to whether reality itself is contradictory. By contrast, Nishida’s attempt is foundational because its concern is the logical form of poietic reality, which, according to Nishida, is contradictory. Notwithstanding the virtue of metaphysical parsimony, we suggest that Deguchi might benefit from revisiting Nishida’s approach – particularly the role of contradiction therein – to lend greater cogency to his axiological proposals.

1 Introduction

Self-as-We, advocated by Yasuo Deguchi,[1] is an attempt to vindicate a holistic conception of the self by working out the implications of what it is to be an agent.[2] What is peculiar about this project is that Deguchi does so by revisiting the philosophical heritage of the East Asian tradition. The first principle of his system, the two theses of fundamental incapability, is rooted in the East Asian tradition of philosophy. In this tradition, according to Deguchi, human essence has been conceived not in terms of some intellectual capacity. Instead, the East Asian self-understanding has largely been formed by the basic fact that we cannot do anything on our own. Building upon this insight, Deguchi demonstrates that a holistic conception of self is defensible. Although the arguments Deguchi provides are independent from its genealogical peculiarities, this conception of self, called Self-as-We, also integrates three key features of the self in the East Asian tradition, i.e. holistic, somatic, and non-dualistic. Thus, we can see that the critical reception of the East Asian philosophical legacies forms an important agenda of Deguchi’s programme.

This is reminiscent of Nishida Kitarō’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity (絶対矛盾的自己同一). This was the culminating point of Nishida’s philosophy, in which he explored the logical structure of the world in which subjects are fundamentally producing agents. By way of this, Nishida also presented a conception of the self that is equipped with the aforementioned three features. The founder of the Kyoto School philosophy did this by mobilising ideas of Western philosophers such as Hegel, Kant, Leibniz, etc., but his attempt was fundamentally informed by the East Asian inspirations. Indeed, Nishida explicitly wrote that his objective is to articulate the logic of the East Asian standpoint.

We can thus recognise a basic resemblance between Deguchi’s Self-as-We and Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. Both are attempts to defend an East Asian conception of self (holistic, somatic, and non-dualistic) by examining the notion of an acting subject. Despite this shared feature, however, the overall outlooks of the two enterprises are markedly different. Indeed, their differences are so numerous and significant that one might not know where to begin when asked to compare the two.

Precisely what are the essential differences between the two? It needs to be noted that what this question is asking for is not a comparison for its own sake. Given the commonality of the underlying theme, this question invites us to consider what it is, what it takes, and what it entails to develop a holistic self by starting with the notion of an acting agent. Such a consideration is not merely speculative, furthermore. As we shall discuss later, the ultimate concern of both Deguchi and Nishida lies in issues pertaining to ethics or, more broadly, value theory. Hence, by considering Self-as-We from a different yet relevant perspective, we can examine whether there is any insight that might inform Deguchi’s on-going axiological project.

In this article, we shall identify the essential differences as rooted in the metaphilosophical dimension and show that these can be best captured in terms of the role of contradiction. Deguchi’s approach is constructive and metaphysically parsimonious in the sense that he starts with his first thesis of fundamental incapability and builds up his system by adding only those theses which are, in his view, necessary to propound his version of holistic self. For this reason, Deguchi remains silent as to whether reality itself is contradictory. By contrast, Nishida’s system is foundational because its concern is the logical form of poietic reality, which, according to Nishida, is contradictory. Notwithstanding the virtue of his metaphysical parsimony, we suggest that Deguchi might benefit from revisiting Nishida’s foundational approach – particularly the role of contradiction therein – to lend greater cogency to his axiological proposals.

In what follows, we shall first outline points of discussion when we compare Deguchi’s Self-as-We and Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. Based on this, we shall attempt to structure these comparative points, whereby we argue that the crucial point lies in the role of contradiction.

2 Precis of Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity

We shall first provide an overview of Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity.[3] Broadly speaking, Nishida’s primary concern is to elucidate the underlying logical structure of poietic reality, in which individuals interact with one another. As we shall see below, his fundamental contention is that this structure is constituted by self-negation, which gives rise to various fundamental contradictions. Furthermore, according to Nishida, this very contradictoriness serves as the foundation for the personhood of the ethical subject, normativity, and a form of value pluralism.

2.1 Metaphysics of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity

The starting point is the concept of the real world (現実の世界). The real world that Nishida investigates is the very world of which we ourselves are a part, the world in which we actually live. According to Nishida, previous philosophical conceptions of the real world are inadequate in that they view it “from the outside, without including oneself within it.”[4] Nishida points out that, in its true sense, the real world is “the world in which one is born, acts, and eventually dies.”[5] This world, Nishida contends, is non-dualistic and is not to be confused with the image which our reflective thinking projects onto it and in which there are distinctions such as subject and object or mind and matter. For Nishida, these categories are abstractly separated in thought, and reality as we experience it is something that exists prior to all such binary frameworks.[6] Nishida’s system of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity is an attempt to elucidate the logical structure of such a non-dichotomous reality.

According to Nishida, the real world is poietic in the sense that its development is unfolded as a historical process of production through the interactions of particulars. Active intuition (行為的直観), one of the key concepts in Nishida’s later philosophy, is nothing other than a concept that expresses what the acting subject is within this poietic reality. As we have seen above, the real world, as Nishida understands it, is not an abstract realm but rather a concrete reality in which we ourselves act. Accordingly, as subjects within this concrete reality, we are essentially embodied agents who exist within specific spatiotemporal conditions and engage in interactions with other entities that likewise occupy space and time. Nishida perceived that this poietic aspect of reality is grounded in a kind of self-negation, and what he calls Absolute Contradictory Self-Identity is nothing other than the dialectic such self-negation gives rise to. This dialectic can be understood as consisting of two key moments.

One is the contradictory self-identity of space and time. Nishida’s central claim is that the constitution of the present – here and now – is grounded in its self-limitation through the contradictory opposition of the past and the future. For the purpose of this article, we do not have to consider the details of this doctrine. For now, what is more important is Nishida’s philosophical concern behind it. His point was that only through such a contradictory relationship can one attain a conception of creative reality without falling into either mechanistic determinism (where the present is determined by the past) or teleological determinism (where the present is determined by the future). Thus, we can say that contradictory self-identity was tied with the poietic nature of reality in Nishida’s thought.

The second element of Nishida’s dialectic concerns the constitution of the particular as an acting being. Just as Nishida rejected the two kinds of determinism in his theory of time, he expounds his own view by way of rejecting two mistaken conceptions of the particular.

The first is what Nishida regards as the Aristotelian notion of the particular. As Nishida sees it, this view understands the particular only as a delimited part of the whole, defined by a set of universals. However, Nishida gathered that this conception of the particular did not capture the formative nature of the world. If the particulars were merely instantiations of the world’s universal properties, then how can they be acting agents? Besides, it also becomes puzzling how something new can emerge through the interaction of these particulars. Accordingly, Nishida concluded that Aristotle’s conception failed to capture the aspect of the particular as an acting being and that, therefore, it could not explain the dynamic aspect of the world as something constituted through the interactions of individuals.

The second conception of the particular which Nishida tried to correct is Leibniz’s monadology. Nishida saw it as taking the opposite approach to Aristotle by starting with the conception of the particular as an acting individual. Characterised by their strict simplicity, i.e. having no parts, Leibniz’s monads are independent entities operating solely through an internal principle of change. However, as is often pointed out, this makes no room for the idea that particulars causally interact, and Nishida regarded this flaw as fatal. As with the Aristotelian conception of the particular, Leibniz’s monadology falls short of accounting for the poietic development of the world through the interaction of particulars.

Thus, according to Nishida, neither of these two conceptions can do justice to the poietic conception of reality. A common feature of the two is the assumption that the underlying substance of reality must be either One or Many, corresponding to the two versions of determinism we saw regarding the philosophy of space and time.

It is to correct this mistaken assumption that Nishida contended that the logical structure of the real world consists in Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity, whereby the substance of the world is seen to be One and Many. Yet precisely what structure does this amount to? While there has been little research on this question, Deguchi, the other philosopher this article focuses on, has attempted to model it from the perspective of dialetheism.[7]

Dialetheism – the view that there are true contradictions (dialetheia) – was chiefly developed and defended by Graham Priest[8] and has since been applied fruitfully in many areas, notably in interpretations of Buddhist philosophical doctrines.[9] According to Deguchi, Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity amounts to a three-layered structure consisting of the world, individual selves, and material things, and their relationship involves dialetheia. Items of these categories are connected by non-transitive identity, a non-standard identity for which we cannot deduce

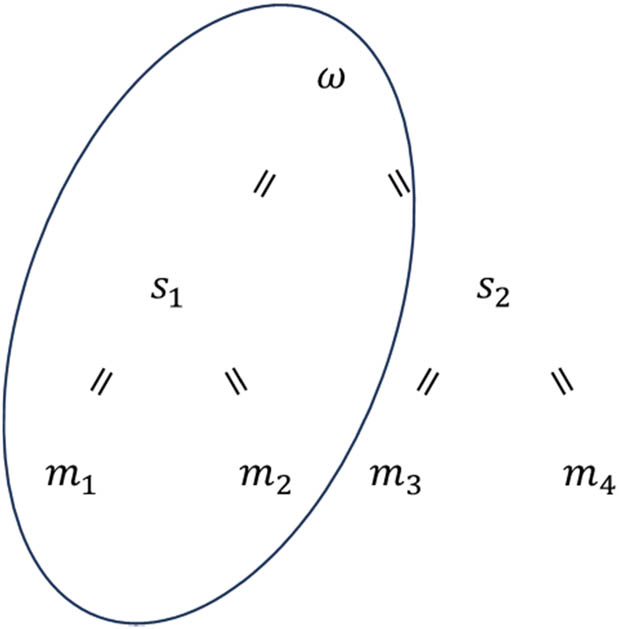

Consider the following diagram.

In this diagram,

2.2 Ethics and Value Theory of Nishida’s System

Deguchi’s Self-as-We proposes a series of WE-turns in the realm of values. Likewise, Nishida’s system was conceived with an eye to ethical and axiological concerns. To thoroughly compare these two systems, therefore, we need to consider the ethical dimension of Nishida’s later philosophy. Broadly speaking, this is twofold. In the first place, the contradictory nature of the self serves as the foundation of normativity in Nishida’s system. Building on this, Nishida presents a form of value pluralism that allows for the contradictory coexistence of different value systems.

2.2.1 Foundation of Normativity

Nishida repeatedly emphasises that the contradictoriness of the self is precisely the foundation of normativity.[11] More specifically, as Nishida engages with Kant, his concern is to ground the notion of ought (Sollen).[12] But in what sense did Nishida conceive of the self’s contradictoriness as grounding the notion of ought? To see this, recall that Nishida’s notion of the real world precedes all frameworks of binary opposition, such as subjective and objective or mind and matter. Instead, Nishida’s dialetheic world incorporates both poles of the fundamental oppositions, such that what we experience is at the intersection of the subjective and the objective.[13] Nishida clarifies this by saying, “when I move the water bottle and say that it has moved, this means that I deny myself and become the thing. And when the thing over there causes me some feeling, what it means is that the thing has become me.”[14] This dialetheic relationship of the subjective and the objective inherent in our interaction with things is transferred into that in the world of persons. In a lecture delivered in 1932,[15] Nishida elaborated this point.[16] He stressed that “Mere acting is not sufficient to express the true self.”[17] As Nishida saw it, the essence of the acting self must include personhood. Then, how is this aspect of the self-constituted? According to Nishida:

The self consists in seeing the absolute Other within oneself and seeing oneself within the absolute Other. Merely stating “absolute Other” is not enough; one must see the Other within oneself. And this Other, within which one sees oneself, cannot be said of material things – it must always bear the meaning of Thou. As Kant argued, my personhood is recognised through my recognising the personhood of others. In other words, I become I by recognising Thou.[18]

As Nishida discusses here, he agreed with Kant and post-Kantian philosophers in saying that the real world as it is inhabited by persons emerges only when the self and the Other recognise each other. Nishida saw this as a dialectical relationship of contradictory self-identity, becoming “I” and “Thou.” In Nishida’s philosophy, this was further grounded on the dialectic of being and nothingness. In another lecture in 1932,[19] Nishida states:

If so, what is Sollen? What is its relationship to the normative world and the historical world? Our self is the point of contact between two dimensions, for instance, between the subjective and the objective. We arrive at the individual when we reach the extreme of limitation of the general. We thereby arrive at the self-limitation of nothingness. At this point, the limiting aspect of being is the objective side, while the aspect of nothingness is the subjective side. Thus, the particular, the individual I, exists within the universal of nothingness that encompasses the universal of being. For this reason, the I not only faces the objective but also immediately acquires the transcendental meaning of normativity.[20]

Though the discussion is rather obscure, this passage nevertheless attests that the subjective and objective, according to Nishida, emerge only through the dialectic of being and nothingness. As this dialectic is precisely what grounds the existence of the individual I, it was tantamount to the foundation of ought. The dialetheism of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity, to which we have attended above, is nothing but the further development of this dialectic of being and nothingness. In this sense, Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity provides the foundations of normativity.[21]

2.2.2 Value Pluralism

Another key feature of Absolute Contradictory Self-Identity in Nishida’s value theory is value pluralism. It is not difficult to imagine that the contradictory relationship between the self and ought, as discussed above, naturally extends beyond the individual to encompass nations and cultural systems. What results is a version of value pluralism in which multiple value systems contradictorily coexist within the unity of the world. For example, in a lecture on the logical structure of reality in 1935, Nishida emphasised:

The idea that Eastern culture is underdeveloped and will eventually become Western culture is a mistaken view. Eastern and Western cultures have each developed independently, based on their own standpoints. Western culture alone will inevitably reach a dead end, and its further development will require the incorporation of Eastern culture. Likewise, Eastern culture will develop by incorporating Western culture. Neither Western nor Eastern culture can ignore the other. This is the true nature of cultural development. However, this does not mean that one culture transforms into another – Eastern culture does not develop into Western culture, nor does Western culture develop into Eastern culture.[22]

Nishida insisted on this interdependent development of cultures by way of explaining the opposition between the subjective and the objective.

Nishida started considering issues pertaining to culture from around 1934 onwards.[23] Noticeably, this coincides with the development of the system of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. His metaphysical discussion was connected to his discussion on culture because the notion of culture that concerned Nishida was foundational in the sense that his reflection was not about superficial cultural phenomena. For example, in The Problem of Japanese Culture (1940), Nishida makes it clear that he is not interested in comparing superficial features of different cultures.[24] Instead, he stresses that we need to investigate what lies at the bases of such observable differences by considering how their logico-metaphysical foundations emerged in the course of history. Adopting Goethe’s terminology, Nishida calls such foundations “archetype.”

Various cultures must be understood and compared in terms of such archetypes. By “archetype”, I do not mean a fixed form but rather a formative principle that infinitely generates itself. From this, various directions of formation and their potential development can be considered. The opposition and interrelation of Eastern and Western cultures must be grasped from this standpoint. This is the reason why I keep insisting that we need to conduct extensive rigorous theoretical research. European culture has solid theoretical foundations because it is grounded in Greek intellectual culture. Against this background, they critique various cultures and discuss their development. Over thousands of years of cultural conflict and friction, a single theoretical archetype has been established. However, Europeans regard this as the one and only cultural archetype, based on which they assess the stages of cultural development, viewing Eastern culture as being at an undeveloped stage. They believe that, if Eastern culture develops further, it must inevitably become the same as Western culture. Even a great thinker like Hegel held this view.[25]

Here again, we see Nishida criticising the idea that all cultural traditions, including Eastern culture, must ultimately converge into Western culture. As he states here, Nishida was not satisfied with Hegel in this regard.

Indeed, it was part of his objective in developing Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity to correct Hegel’s dialectic. As Nishida saw it, his system was an attempt to articulate the logic of Eastern philosophy. Nishida maintains that at the foundation of Eastern culture lies a certain logical structure and that this locates the subject within the world.[26] As we have seen above, this is precisely the logical structure of reality in Absolute Contradictory Self-Identity. By thus articulating the logic of Eastern culture, Nishida’s aim was, of course, not to argue that Eastern logic was superior. While acknowledging that logic is fundamentally one,[27] Nishida believed it could develop in different directions depending on the self-formative process of the historical world. For this purpose, he took it as his task to articulate the “architype” of Eastern culture and thereby to put it in a dialogue with the Western one. In Nishida’s vision, these distinct logical perspectives retain their unique identities while simultaneously contributing to the formation of a global culture as a unity.

In this sense, Nishida’s theory of cultural pluralism is grounded at the logical level, advocating for the plurality of cultural frameworks. It is in this respect that Nishida stands as one of the first philosophers to articulate value pluralism from a metaphysical standpoint.[28]

3 Key Contrasts Between Self-as-We and Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity

We have now reviewed Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. On the basis of this, let us proceed to compare Deguchi’s Self-as-We and Nishida’s system.

Given the overview, it is not difficult to notice that there are common features between the two philosophical systems. As we have suggested at the outset, both systems explore what it means for us to be acting subjects. As a result of this enquiry, both Nishida and Deguchi present an East Asian conception of self, according to which the true self is holistic, somatic, and non-dualistic. We have confirmed, furthermore, that both systems are fundamentally ethical enterprises insofar as their ultimate objective lies in the ethical implications that arise when we articulate an Eastern perspective.

Apart from these common features, however, the two systems unfold in markedly different ways. In what follows, we shall consider the differences in terms of their principle, method, and scope.

3.1 Principle

First of all, the two systems differ in terms of their principles. The principle underpinning Deguchi’s Self-as-We is the (first) thesis of fundamental incapability. Based on the insight that human beings cannot accomplish anything entirely on their own, Deguchi introduces the concept of multi-agent systems. Of course, to establish Self-as-We, one must posit further assumptions, i.e. doer externalism, an appropriate delimitation of the subject’s scope, and the conception of the self as an agent. However, compared with the first thesis of fundamental incapability, these assumptions serve only a supporting role. In this sense, we can say that the most crucial principle for Deguchi’s Self-as-We is indeed the thesis of fundamental incapability.

In contrast, for Nishida, what serves as the fundamental principle is the claim that the real world and the self are contradictory. As noted above, the “real world” in Nishida’s sense is the world we experience in our everyday lives. Rather than an either/or dichotomy of the subjective or the objective, it is a dialetheic world of both/and that is at once subjective and objective. Because Nishida’s aim is to illuminate the logical structure of precisely this dialetheic world, one must share the intuition that reality and the self are contradictory in order to enter Nishida’s system.

We could say that there is a common feature between the two principles in so far as both Deguchi’s thesis of fundamental incapability and Nishida’s contradictory conception of the world draw on an East Asian view of humanity and the world. However, the nature of each principle appears to differ greatly.

To begin with, note that we can, to a certain extent, examine the validity of Deguchi’s thesis of fundamental incapability by testing its plausibility against empirical facts. Indeed, when explaining this thesis, Deguchi himself provides an argumentation of that sort. What he does is to consider specific actions such as riding a bicycle and thereby to show that their execution presupposes certain affordances such as the production of the bicycle, the existence of an appropriate environment for riding the bicycle, etc. Of course, there are various questions about the precise nature of this demonstration. Nevertheless, we can say that a key feature of Deguchi’s thesis is that its plausibility can easily be examined in light of our ordinary experience.

By contrast, Nishida’s philosophy, though it is claimed to be about the world we directly experience, begins with an intuition that is rather elusive and, accordingly, difficult to subject to reflective scrutiny. According to Nishida, the various dualistic distinctions we conventionally accept are nothing more than projections of reflective thinking onto the world. Conversely, the primordial fact that the world of direct experience is non-dualistic cannot be captured by discursive intellect. Of course, this does not mean that Nishida’s philosophy thereby becomes an irrational doctrine based on a mystical intuition. The sort of intuition Nishida discusses is immanent in our acting (or “working” to use Nishida’s preferred term), for he repeatedly emphasises that the “real world” he speaks of is about the most commonplace, everyday experiences. Indeed, rather than a mystical experience, paradigmatic examples Nishida provides are the experiences of a carpenter or an artist engaged in creating something. Hence, the dialetheic nature of Nishida’s real world is something we can purportedly grasp by carefully observing ordinary, everyday reality.

3.2 Method

The difference in principles affects how each system is to be expounded. We can say that this divergence is a difference in methods in view of the word’s original sense, i.e. the manner in which an investigation is carried out.

In the case of Deguchi’s Self-as-We, each of the assumptions is formulated and made explicit as a separate proposition.[29] Accordingly, Deguchi’s system is structured step by step, allowing anyone engaging with it to move from recognising fundamental incapability to successively considering a series of value proposals for social transformation. In this specific sense, one might say that Deguchi’s Self-as-We is constructive.

One reason for Deguchi’s choice of this argumentative style is strategic. If we are to let the East Asian conception of the self enter the stage of contemporary philosophy, it must speak our language so that the audience can critically evaluate it. Hence, it must be reconfigured in a way that admits rational critique and examination. Otherwise, a holistic, embodied, and non-dualistic self can easily appear as an esoteric doctrine of mysticism. That might be a subject of curiosity for a historian or an anthropologist, but one cannot seriously engage with it. In any event, compared with the arguments of East Asian philosophers from whom Deguchi gets certain inspirations, his Self-as-We stands out for its style of building up a constructive line of reasoning in a step-by-step manner.

In contrast, Nishida does not appear to develop constructive arguments in the same way as Deguchi does. Indeed, Nishida’s philosophy often gives the impression of being quite the opposite of the clarity found in Deguchi’s Self-as-We. Why might this be? And in any case, does this difference in how the arguments are developed simply reflect a stylistic divergence, or does it point to a substantial difference in each philosopher’s inquiry, i.e. something that cannot be reduced to style alone? For instance, if Nishida’s arguments could be reconstructed in the same manner as Deguchi’s, one might conclude that the difference between them is purely one of style. If not, conversely, then what the methodological gap might mean shall be the subject of our examination.

To shed light on why Nishida’s system can be so challenging to grasp, we shall begin by systematically examining the potential reasons. Generally speaking, when one wishes to advance a constructive line of argument in the way that Deguchi does, the method is to first identify and articulate the fundamental topic or problem at issue, then formulate theses that address it, break them down, clarify the demonstrative structure among the resulting propositions, and finally synthesise them into a coherent framework. What, then, of Nishida’s approach?

First, when it comes to specifying the central theme or problem, it is not always clear precisely what Nishida has in mind. To be sure, as we have observed in our overview of Nishida’s system, he explicitly states that his central task is to elucidate the logical structure of the real world in which we ourselves are situated as acting agents. Thus, it is not wholly accurate to claim that Nishida fails to define his fundamental question. Nevertheless, one can still argue that it remains uncertain what, strictly speaking, Nishida takes his principal problem to be.

One aspect of this uncertainty involves Nishida’s style. He does not proceed by explicitly declaring his primary question and then systematically articulating his argument. In our own overview, we have identified Nishida’s central problematic by examining his scattered comments in various essays, lectures, and letters, interpreting them in light of the context in which his philosophy developed. Nishida himself does not, for instance, clarify at the beginning of “Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity” what exactly the issue is.

While this can be seen as a matter of style (and amenable in principle to critical reconstruction), there are also elements that cannot be explained simply by style. Specifically, the problem we have extracted from Nishida’s works occupies a highly abstract plane, and it is not obvious that such abstraction can be resolved by analysis alone. For instance, clarifying the logical structure of the world we immediately experience is itself an undertaking that raises meta-metaphysical questions of various kinds. Although enumerating these questions may help us pinpoint, to a certain extent, the issues Nishida treats, his discussion remains at a high level of abstraction and thus does not necessarily dispel the aura of abstruseness.

Moreover, when Nishida indicates that he deals with a world that includes us as acting agents, he is challenging any metaphysics that locates the cognising subject outside the world. Yet, we only discover how this challenge takes shape in light of Nishida’s reinterpretations of Western philosophical figures like Aristotle or Kant. Inevitably, such an inquiry operates within Nishida’s unique conceptual space, so we only move within a hermeneutic circle. Hence, we cannot merely reduce the difficulty of grasping Nishida’s central concern to his distinctive style. Rather, part of the difficulty supposedly lies in the nature of the problem itself.

It is not uncommon, of course, for philosophical systems throughout history to deal with problems of such abstraction, and that level of abstraction directly affects how the arguments unfold. In other words, it is not simply for stylistic reasons that Nishida’s system evades the kind of constructive demonstration we observe in Deguchi’s Self-as-We. Additionally, in examining Nishida’s argumentation, we must recall that he presupposes his own version of dialectic. Although the notion of dialectic itself is subject to discussion, Nishida’s case is especially noteworthy, given that he develops his own notion under influences ranging from Hegel and Marx to Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky. We need not elaborate on all such details here, however. As long as our concern lies in the argumentative structure, it suffices to note that Nishida’s use of dialectic reflects his conviction that negation is essential to the logical structure of reality or concepts and that any attempt to clarify their development must proceed through a staged unfolding of contradictions. This dialectical method inherently complicates the presentation of Nishida’s system, as it traces the logical movement of concepts or realities through a series of contradictions, rather than simply accumulating one demonstration after another. In this sense, too, Nishida’s system is difficult to comprehend for reasons that cannot be reduced to mere stylistic choices.

Considering all these factors, while it may not be theoretically impossible, reconstructing Nishida’s philosophy of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity into a constructive system of argumentation akin to Deguchi’s Self-as-We is likely to face significant hurdles. To be sure, as we have attempted in earlier sections, one can provide a partial reconstruction that offers some measure of clarity, but this does not mean we can reorganise Nishida’s thought as neatly as Deguchi does for his own system. If, therefore, the methodological discrepancy between Nishida’s system and Deguchi’s cannot be reduced to style alone, we must ask what precisely this implies. Before addressing this point, let us examine the difference in the scope of the issues each system aims to tackle.

3.3 Scope

Concerning the range of the problems the two philosophical systems address, one striking difference between Deguchi’s Self-as-We and Nishida’s system is that, while a substantial metaphysics of time and space underlies Nishida’s thought, such an account is notably absent from Deguchi’s discussion. Why is this so?

In our earlier overview of Nishida’s system, we have already briefly discussed why Nishida develops a philosophy of time and space. We noted that he addresses space-time because it is inextricably tied to the world’s poietic development. Accordingly, his discussion on space and time directly belongs to his principal task of clarifying the logical structure of the real world. To make the contrast with Self-as-We clear, observe that this point can also be framed in terms of his concept of the acting individual. Acting, after all, consists of concrete, creative operations unfolding in space and time, and the individual, possessed of consciousness that experiences the present, is built through the contradictory formation of space-time that Nishida advocates. In fact, according to Nishida’s notion of the real world, its creative development is effectively equivalent to individuals interacting together within that world, for it is such interactions that give rise to the poietic evolution of the world. In short, one could say that Nishida’s distinctive account of space and time assumes special importance because, in his view, it is a central component of the logical structure of the acting individual.

From this perspective, it is noticeable that Deguchi’s Self-as-We does not address the task of clarifying the logical structure of individual agency. Rather, he adopts what he calls metaphysical minimalism, and thereby deliberately remains uncommitted to the question of what the individual or action is, or the ontological basis on which such phenomena are grounded.[30]

Deguchi’s stance seems to be as follows: that the individual self exists, or that we are acting subjects, is an apodictic fact. Taking this as a given, if one can demonstrate the theses of the Self-as-We system, then the WE-turn of the actor as well as the subsequent series of axiological WE-turns can proceed without introducing any metaphysically rich structure. Of course, one may freely add such extra premises, but Deguchi would maintain that this is something best left to those who engage with his system.

This strategy appears reasonable. Of course, it needs to be noted that this rests on the assumption that adding further premises (notwithstanding the meta-philosophical difficulty of specifying what truly counts as “additional”) will not affect the content or implications of the theses that Deguchi defends. Since a comprehensive vindication of this implicit assumption is unrealistic, we should rather take Deguchi’s adoption of metaphysical minimalism as effectively declaring that it is an assumption. In any case, however, we can say that Deguchi strategically adopts metaphysical parsimony, and that is certainly an effective strategy in advocating a holistic conception of self.

Yet, if the sort of metaphysical parsimony Deguchi adopts is indeed an available option, we might in turn be tempted to ask what motivates Nishida to marshal the kind of full-fledged metaphysics we find in Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. In the next section, we shall suggest that this is rooted in the foundational nature of Nishida’s attempt.

4 Reflection: Role of Contradiction and Value Pluralism

Let us recapitulate our discussion in the previous section. We have confirmed that not only do Nishida’s system and Deguchi’s system differ in their respective starting principles, but that there is also a difference in the nature of those principles – one that directly leads to the divergent ways in which each philosophical system unfolds. Moreover, we have suggested that these differences are not simply matters of style but instead stem from the difference in the scope of the issues that Nishida and Deguchi address. Nishida’s engagement with space and time is not merely due to it being one of his occasional interests (indeed, he consistently discusses this subject when explaining Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity). Rather, since his endeavour is essentially to elucidate the logical structure of the world, he was, in a sense, inevitably obliged to undertake this task. Our question, then, has been this: if one’s purpose is to develop a holistic conception of self, it seems at first glance that Deguchi’s metaphysical parsimony might suffice, so what is the significance of constructing a weighty metaphysical system such as Nishida’s?

A crucial point in clarifying this significance relates to the fact that Nishida himself characterises his undertaking as the elucidation of the logical structure of reality. One key reason this matters is that Nishida understands “reality” to be a domain that precedes the scientific explanations or demonstrations grounded in dichotomous logic. In this sense, what Nishida pursues can be contrasted with an “explanation” of a phenomenon if we mean by it providing a system of hypotheses that best describe the behaviour of the explanandum. Such hypotheses are obtained only when we analytically examine the phenomenon. By contrast, in Nishida’s elucidation of logical structure, the object of inquiry is not something that exists in a decomposable form. Rather, it is structured in an interdependent way. For Nishida, what defines each individual is inseparable from its dialectical relationship to the whole, and this cannot be extricated from his account of the contradictory self-identity of space and time. Consequently, it should be noted that Nishida’s holistic conception of the self does not result from accepting the contradictoriness of the world. Instead, one could say that the contradictoriness of the world and the holistic nature of the self are, in some sense, tantamount. In this respect as well, Nishida’s system stands in contrast to Deguchi’s Self-as-We, in which the holistic self is derived from the thesis of fundamental incapability, whereas in Nishida’s case, embracing the contradictoriness of the world is embracing a holistic view of the self.

Seen in this light, the difference in the nature of each principle, as discussed in the previous section, also becomes clearer. In Deguchi’s notion of fundamental incapability, that principle by itself does not suffice to derive the entirety of the Self-as-We system. By contrast, accepting Nishida’s contradictory real world amounts immediately to accepting the entire structure that Nishida describes within his system.

Taking all this into account, we can say that while both Nishida and Deguchi strive to defend a holistic, embodied, and non-dualistic conception of the self, their enterprises differ greatly in character, a difference attributable to their contrasting metaphilosophical stances. In the previous section, we referred to Deguchi’s approach as constructive in character. In contrast, since Nishida’s approach examines questions such as what an individual is and what it fundamentally means for that individual to act, it may be called foundational. Furthermore, for Nishida, this foundationality is inseparable from the contradictoriness of the world. Indeed, as the contradictoriness of the world is for him also the contradictoriness of the self, we can summarise our discussion so far by saying the metaphilosophical difference between Nishida’s system and Deguchi’s essentially arises from the diverging attitudes they adopt towards the problem of how to conceive of the contradictoriness of the self.

Indeed, even though both systems defend a conception of self that is endowed with the same three features, the role played by contradiction differs markedly between the two, which is a point well worth noting. As should be clear from the foregoing discussion, in Nishida’s case, wholeness and non-dualism are intrinsically linked. To accept the self’s contradictoriness is tantamount to sharing in the real world as clarified by Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. For Deguchi, by contrast, the non-dualistic character of We is simply a trait introduced during the process of the WE-turn. In that scheme, We possesses a contradictory nature insofar as it expresses the unity of entities with opposing characteristics. As long as We itself inherits these conflicting traits from its constituent members, it is considered a dialetheic entity that bears pairs of contradictory qualities.[31] In this respect, we can say Deguchi’s Self-as-We also incorporates the non-dualistic aspect of a holistic self. However, this is only in a more limited sense than Nishida’s. This limitedness can be seen in at least three different respects.

First, as noted above, the self’s contradictoriness in Deguchi’s account is merely an added feature. In other words, the dialetheic character of We arises after the We-turn, by positing certain supplementary assumptions, and hence can be separated from the very notion of We. By contrast, contradiction is pervasive throughout Nishida’s system. In Nishida’s framework, contradiction and wholeness consistently form an inseparable structure and operate at every stage of the system’s deployment. In comparison, contradiction does not serve to characterise the development of Deguchi’s system itself.

Second, from the perspective of value theory, one might question how far the dialetheic stance in Deguchi’s system can attain substantive significance compared with Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity. We noted that in Self-as-We, the self’s contradictoriness is expressed solely in that We comprises various pairs of opposing characteristics. This is relevant for value theory as well, for the dialetheic nature of We suggests the co-existence of multiple, potentially conflicting values within a single whole, and this is certainly reminiscent of the contradictory many-and-one relationship in Nishida’s system. Thus, a position that recognises such contradictory pluralism in values, while simultaneously acknowledging a unifying wholeness, may prove valuable as a form of value pluralism. Rather than simply observing empirically that values often diverge and clash, it suggests the possibility of a more encompassing, non-restrictive viewpoint that embraces such contradictory diversity, potentially providing guidance as to what we should do in the face of polarising plurality within the normative domain.

However, since contradiction plays only a restricted role in the first sense, it remains debatable to what extent this value-theoretical significance in Self-as-We can indeed be substantive. Even if Self-as-We maintains that contradictory value systems can coexist within We, the very existence of such conflicting values is treated as a given. By contrast, Nishida’s logic of contradictory self-identity clarifies that the relationship between opposed individuals or cultures is grounded in a self-limiting process through negation, thus revealing that the formation of each contradictory value depends on the presence of the Other. Unlike Deguchi’s approach, therefore, Nishida’s account explores the very foundation of conflicting values and, as noted in our overview, this immediately gives the foundation of a unifying whole. Conversely, if one does not construct the standpoint of a collective We from such a foundational dimension, it is questionable whether the dialetheic We in Self-as-We has any substantive implication beyond merely acknowledging that individuals and value systems are diverse. For instance, one might observe that evaluating is itself a kind of action, and therefore presupposes a multi-agent system. One could say, in this sense, each individual value system depends on the existence of another. Yet if the WE-turn in value judgements simply is executed alongside a WE-turn in mental activity, that does not truly probe the depth of the contradictory tension inherent in values. There is no inherent necessity for the Other, as an opposing perspective, to be integrated into the same multi-agent system underlying that value judgement. In other words, the dialetheic value theory of Self-as-We is only limited insofar as it does not consider the contradictory interdependence of values as that of values arising through contradictions. In Deguchi’s system, conflicting value systems merely receive unity in the network of action, so it remains open to debate whether Self-as-We provides an overarching perspective that can accommodate the normative dimension.

Third and finally, in a point related to the second, because the contradictoriness of the self in Self-as-We is merely a trait of We itself, it does not manifest as a relationship between We and the individual. Here too, Deguchi’s perspective stands in contrast to Kyoto School philosophers such as Nishida or Watsuji. For instance, Watsuji noted a dialectical relationship between individuality and wholeness, and repeatedly emphasised the importance of taking due regard to this twofold nature of human existence in his project of ethics as an anthropological inquiry.[32] Similarly, as discussed above, Nishida’s system of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity attempted to ground the notion of ought precisely on this contradictory duality. By comparison, we can say that Self-as-We does not exhibit such an I-versus-We opposition. In Self-as-We, the I as individual begins as a constituent with a particular place in the greater We, then is treated as two modes of consciousness and, further, a narrative subject existing at a fictional level, culminating in four distinct layers.[33] To that extent, I is distinguished from We, and Deguchi is careful to distinguish his system from Hegel’s stance, in which the I and We converge in an objective self.[34] Hence, it would be inaccurate to say outright that Deguchi reduces I to We. Yet from the standpoint of Kyoto School philosophers like Nishida or Watsuji, the issue appears more complicated. Arguably, none of the four layers of I in Self-as-We is such an entity that stands in fundamental tension with the whole (such as the autonomous I in Kant’s philosophy). This leaves Deguchi only two options: either exclude such an I from the system altogether as incompatible, or incorporate it in such a way that, should actual conflict arise, I can only be treated as a fictional entity, which is what Deguchi effectively does. Accordingly, we can say that Deguchi circumvents the sort of contradiction that Kyoto School thinkers like Nishida and Watsuji regarded as emerging between I and We in a deeper sense. While this is certainly a viable argumentative strategy in its own right, Nishida might encourage Deguchi to reconsider it. If the dialectical relationship between the individual and the whole was indeed crucial in providing the ethical foundations of the classical Kyoto School, it is indeed regrettable that Deguchi’s latest attempt does not properly take it into account.

The three points noted above do not exhaust the matter, but they convey the sense in which, relative to Nishida’s approach, we wish to say the self’s contradictoriness plays only a restricted role in Deguchi’s system. Taking these points into account, it becomes clear that the fundamental differences lurking beneath the superficial resemblance between the two systems arise entirely from the stance each takes towards the self’s contradictory nature. Considered in this way, the relationship between fundamental incapability and the self’s contradictoriness once again becomes an issue. In the next section, we shall explore this question once more by way of concluding this article.

5 Conclusion: Incapability or Contradiction – Which is More Fundamental?

The difference between fundamental incapability and the contradictoriness of the self leads to a distinction in the respective metaphilosophical stances of Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity and Self-as-We. As far as our analysis suggests, Deguchi’s system adopts a constructive, demonstrative approach in order to persuasively present an East Asian conception of the self in contemporary philosophy. Owing to this fact, unlike Nishida’s philosophy, we are able to examine Deguchi’s conception of the self critically. Meanwhile, although Nishida’s willingness to embrace the contradictoriness of the self renders his philosophy less immediately accessible, we have seen that it can respond to foundational problems in value theory that Deguchi’s system might arguably be unable to address.

One obvious issue arising from this contrast is this: which principle is more fundamental, that of fundamental incapability or that of the self’s contradictoriness? From Nishida’s perspective, Deguchi’s notion of fundamental incapability would, at bottom, be grounded in the self’s contradictoriness. Asked why human beings cannot accomplish any action entirely on their own, Nishida’s late philosophy would reply that action as such presupposes a dialectical movement, which is itself none other than the contradictoriness of the world. Of course, Deguchi might argue that posing such a “why” question is, in fact, illegitimate. Even if one did deem it meaningful, grounding Self-as-We in something like Nishida’s self-contradictoriness might be criticised as a move that posits an overly strong premise from which everything else follows – thus violating the metaphysical parsimony Deguchi recommends. In any event, one might conclude that developing so heavily metaphysical a system, as Nishida does, serves little purpose in the pursuit of the value-theoretic project Deguchi envisions.

Yet if, as this article has suggested, there remain foundational issues in value theory that Deguchi’s system arguably cannot adequately address, one can certainly claim that revisiting Nishida’s concerns would be worthwhile. In fact, it also merits attention that Deguchi has not made clear in precisely what sense his fundamental incapability is “fundamental.” Of course, we can say it is fundamental, as Deguchi does, in that it cannot be derived from any more basic thesis. However, if in his discussion of riding a bicycle, Deguchi is simply highlighting that a range of physical, historical, and social factors must be presupposed for a given phenomenon to occur, then whether this observation actually yields normative implications is open to debate. After all, even if the agent of action shifts in light of the causal structure in the phenomenal dimension, that does not automatically entail a need to alter the conceptual architecture of the normative domain. In other words, even if one acknowledges the WE-turn of action, one might still uphold a system of responsibility, rights, etc. that relies on the autonomous I (even if it is ultimately fictitious in one sense or another). Whether the series of WE-turns of value Deguchi proposes gains greater cogency through an appeal to the kind of self-contradictoriness Nishida defends remains to be explored, but we should like to say it is a question worth pursuing.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Rein Raud, Dr Felipe Cuervo Restrepo and the anonymous reviewers for reading the manuscript and for their helpful comments. Any remaining errors are our own.

-

Funding information: This publication has been financially supported by the Kyoto Institute of Philosophy.

-

Author contributions: All authors accepted responsibility for the content of the manuscript, consented to its submission, reviewed all results/arguments, and approved the final version. JS conceived the central ideas and discussed them with ST. ST refined the argumentative structure and expanded the literature review.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References Abbreviations

NKZ Nishida, Kitarō. 『西田幾多郎全集』 [Nishida Kitarō Zenshū; Collected Works of Nishida Kitarō]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002–2009.Suche in Google Scholar

WTZ Watsuji, Tetsurō. 『和辻哲郎全集』 [Watsuji Tetsurō Zenshū; Collected Works of Watsuji Tetsurō]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1961–1978.Suche in Google Scholar

Other Sources

Deguchi, Yasuo. 「「できること」から「できなさ」へ 」[“Dekiru-koto Kara Dekinasa He”; “From Capabilitity to Incapability”]. 浅草寺佛教文化講座 [Sensō-ji Bukkyō Bunka Kōza; Senso-ji Buddhist Culture Lecture Series] 67 (2023), 99–119.Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo. “Active Intuition: Self and Dialetheism in Late Nishida’s Philosophy.” The Handbook of Intuition, edited by Ahmed Asad, et al. Cham: Springer, Forthcoming.Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo. 『AI親友論』 [AI Shin-Yū Ron; AI as Fellows]. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo. “From Incapability to We-Turn.” Meta-Science: Towards a Science of Meaning and Complex Solutions, edited by Andrej Zwitter and Takuo Dome, 41–70. Groningen: University of Groningen Press, 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo. “The WE-turn of Action: Principles.” Open Philosophy 8:1 (2025), 1–14.Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo. “The WE-turn of Value: Principles.” The Journal of Philosophical Studies 614 (2025), 1–43.10.1515/opphil-2025-0092Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo, Jay Lazar Garfield, and Graham Priest. “The Way of the Dialetheist: Contradictions in Buddhism.” Philosophy East and West 58:3 (2008), 395–402.10.1353/pew.0.0011Suche in Google Scholar

Deguchi, Yasuo and Vito Mabrucco. “Self-as-We: A conversation with Professor Yasuo Deguchi about the Ethics of Technology.” (Unpublished).Suche in Google Scholar

Priest, Graham. In Contradiction: A Study of the Transconsistent. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199263301.003.0015Suche in Google Scholar

Priest, Graham. “Non-Transitive Identity.” Cuts and Clouds: Vagueness, edited by Richard Dietz and Sebastiano Moruzzi, 406–16. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199570386.003.0024Suche in Google Scholar

Wansing, Heinrich and Daniel Skurt. “On Non-transitive “Identity”.” Graham Priest on Dialetheism and Paraconsistency, edited by Can Başkent and Thomas Macaulay Ferguson, 535–53. Cham: Springer, 2019.10.1007/978-3-030-25365-3_25Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special issue: Sensuality and Robots: An Aesthetic Approach to Human-Robot Interactions, edited by Adrià Harillo Pla

- Editorial

- Sensual Environmental Robots: Entanglements of Speculative Realist Ideas with Design Theory and Practice

- Technically Getting Off: On the Hope, Disgust, and Time of Robo-Erotics

- Aristotle and Sartre on Eros and Love-Robots

- Digital Friends and Empathy Blindness

- Bridging the Emotional Gap: Philosophical Insights into Sensual Robots with Large Language Model Technology

- Can and Should AI Help Us Quantify Philosophical Health?

- Special issue: Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic, edited by Graziana Ciola (Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands), Milo Crimi (University of Montevallo, USA), and Calvin Normore (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) - Part II

- The Power of Predication and Quantification

- A Unifying Double-Reference Approach to Semantic Paradoxes: From the White-Horse-Not-Horse Paradox and the Ultimate-Unspeakable Paradox to the Liar Paradox in View of the Principle of Noncontradiction

- The Zhou Puzzle: A Peek Into Quantification in Mohist Logic

- Empty Reference in Sixteenth-Century Nominalism: John Mair’s Case

- Did Aristotle have a Doctrine of Existential Import?

- Nonexistent Objects: The Avicenna Transform

- Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic: Afterword

- Special issue: Philosophical Approaches to Games and Gamification: Ethical, Aesthetic, Technological and Political Perspectives, edited by Giannis Perperidis (Ionian University, Greece)

- Thinking Games: Philosophical Explorations in the Digital Age

- On What Makes Some Video Games Philosophical

- Playable Concepts? For a Critique of Videogame Reason

- The Gamification of Games and Inhibited Play

- Rethinking Gamification within a Genealogy of Governmental Discourses

- Integrating Ethics of Technology into a Serious Game: The Case of Tethics

- Battlefields of Play & Games: From a Method of Comparative Ludology to a Strategy of Ecosophic Ludic Architecture

- Special issue: "We-Turn": The Philosophical Project by Yasuo Deguchi, edited by Rein Raud (Tallin University, Estonia)

- Introductory Remarks

- The WE-turn of Action: Principles

- Meaning as Interbeing: A Treatment of the WE-turn and Meta-Science

- Yasuo Deguchi’s “WE-turn”: A Social Ontology for the Post-Anthropocentric World

- Incapability or Contradiction? Deguchi’s Self-as-We in Light of Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity

- The Logic of Non-Oppositional Selfhood: How to Remain Free from Dichotomies While Still Using Them

- Topology of the We: Ur-Ich, Pre-Subjectivity, and Knot Structures

- Listening to the Daoing in the Morning

- Research Articles

- Being Is a Being

- What Do Science and Historical Denialists Deny – If Any – When Addressing Certainties in Wittgenstein’s Sense?

- A Relational Psychoanalytic Analysis of Ovid’s “Narcissus and Echo”: Toward the Obstinate Persistence of the Relational

- What Makes a Prediction Arbitrary? A Proposal

- Self-Driving Cars, Trolley Problems, and the Value of Human Life: An Argument Against Abstracting Human Characteristics

- Arche and Nous in Heidegger’s and Aristotle’s Understanding of Phronesis

- Demons as Decolonial Hyperobjects: Uneven Histories of Hauntology

- Expression and Expressiveness according to Maurice Merleau-Ponty

- A Visual Solution to the Raven Paradox: A Short Note on Intuition, Inductive Logic, and Confirmative Evidence

- From Necropower to Earthly Care: Rethinking Environmental Crisis through Achille Mbembe

- Realism Means Formalism: Latour, Bryant, and the Critique of Materialism

- A Question that Says What it Does: On the Aperture of Materialism with Brassier and Bataille

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special issue: Sensuality and Robots: An Aesthetic Approach to Human-Robot Interactions, edited by Adrià Harillo Pla

- Editorial

- Sensual Environmental Robots: Entanglements of Speculative Realist Ideas with Design Theory and Practice

- Technically Getting Off: On the Hope, Disgust, and Time of Robo-Erotics

- Aristotle and Sartre on Eros and Love-Robots

- Digital Friends and Empathy Blindness

- Bridging the Emotional Gap: Philosophical Insights into Sensual Robots with Large Language Model Technology

- Can and Should AI Help Us Quantify Philosophical Health?

- Special issue: Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic, edited by Graziana Ciola (Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands), Milo Crimi (University of Montevallo, USA), and Calvin Normore (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) - Part II

- The Power of Predication and Quantification

- A Unifying Double-Reference Approach to Semantic Paradoxes: From the White-Horse-Not-Horse Paradox and the Ultimate-Unspeakable Paradox to the Liar Paradox in View of the Principle of Noncontradiction

- The Zhou Puzzle: A Peek Into Quantification in Mohist Logic

- Empty Reference in Sixteenth-Century Nominalism: John Mair’s Case

- Did Aristotle have a Doctrine of Existential Import?

- Nonexistent Objects: The Avicenna Transform

- Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic: Afterword

- Special issue: Philosophical Approaches to Games and Gamification: Ethical, Aesthetic, Technological and Political Perspectives, edited by Giannis Perperidis (Ionian University, Greece)

- Thinking Games: Philosophical Explorations in the Digital Age

- On What Makes Some Video Games Philosophical

- Playable Concepts? For a Critique of Videogame Reason

- The Gamification of Games and Inhibited Play

- Rethinking Gamification within a Genealogy of Governmental Discourses

- Integrating Ethics of Technology into a Serious Game: The Case of Tethics

- Battlefields of Play & Games: From a Method of Comparative Ludology to a Strategy of Ecosophic Ludic Architecture

- Special issue: "We-Turn": The Philosophical Project by Yasuo Deguchi, edited by Rein Raud (Tallin University, Estonia)

- Introductory Remarks

- The WE-turn of Action: Principles

- Meaning as Interbeing: A Treatment of the WE-turn and Meta-Science

- Yasuo Deguchi’s “WE-turn”: A Social Ontology for the Post-Anthropocentric World

- Incapability or Contradiction? Deguchi’s Self-as-We in Light of Nishida’s Absolutely Contradictory Self-Identity

- The Logic of Non-Oppositional Selfhood: How to Remain Free from Dichotomies While Still Using Them

- Topology of the We: Ur-Ich, Pre-Subjectivity, and Knot Structures

- Listening to the Daoing in the Morning

- Research Articles

- Being Is a Being

- What Do Science and Historical Denialists Deny – If Any – When Addressing Certainties in Wittgenstein’s Sense?

- A Relational Psychoanalytic Analysis of Ovid’s “Narcissus and Echo”: Toward the Obstinate Persistence of the Relational

- What Makes a Prediction Arbitrary? A Proposal

- Self-Driving Cars, Trolley Problems, and the Value of Human Life: An Argument Against Abstracting Human Characteristics

- Arche and Nous in Heidegger’s and Aristotle’s Understanding of Phronesis

- Demons as Decolonial Hyperobjects: Uneven Histories of Hauntology

- Expression and Expressiveness according to Maurice Merleau-Ponty

- A Visual Solution to the Raven Paradox: A Short Note on Intuition, Inductive Logic, and Confirmative Evidence

- From Necropower to Earthly Care: Rethinking Environmental Crisis through Achille Mbembe

- Realism Means Formalism: Latour, Bryant, and the Critique of Materialism

- A Question that Says What it Does: On the Aperture of Materialism with Brassier and Bataille