Abstract

Even in this era of parameter-heavy statistical modeling requiring large training datasets, we believe explicit symbolic models of grammar have much to offer, especially when it comes to modeling complex syntactic phenomena using a minimal number of parameters. It is the goal of explanatory symbolic models to make explicit a minimal set of features that license phrase structure, and thus, they should be of interest to engineers seeking parameter-efficient language models. Relative clauses have been much studied and have a long history in linguistics. We contribute a feature-driven account of the formation of a variety of basic English relative clauses in the Minimalist Program framework that is precisely defined, descriptively adequate, and computationally feasible in the sense that we have not observed an exponential scaling with the number of heads in the Lexical Array. Following previous work, we assume an analysis involving a uT feature and uRel feature, possibly simultaneously valued. In this article, we show a detailed mechanical implementation of this analysis and describe the structures computed for that, which, and who/whom relatives for standard English.

1 Introduction

Relative clauses have been the subject of much research in modern Generative Grammar.[1] These constructions are of particular interest because the head noun of the relative clause appears to be doubly licensed. In (1)a, resp. (1)b, the relative clause head noun man appears to obtain both grammatical case and a theta-role in two distinct positions (assuming that there is only one head noun man); i.e., as an object (resp. subject) of the relative clause verb saw (resp. loves) and as an object of the matrix verb like.

| (1) | (a) I don’t like [the man who John saw |

| (b) I don’t like [the man who |

Analyses of relative clauses in the Generative Grammar tradition have attempted to explain the structure of relative clauses and clarify how a relative N is licensed. Analyses can be loosely categorized into matching analyses, in which there are two separate relative nouns that have the same reference, and head promotion/raising analyses in which there is only one relative noun that undergoes movement. In an operator movement analysis, like that in (2)a (Chomsky 1977, Chomsky and Lasnik 1995), a relative operator is base generated in the relative clause and raises to the specifier of the CP. It then gets its interpretation by being associated with an external noun, expressed through coindexation here. In another account, shown in (2)b, there are two separate relative nouns that have the same reference, and the lower noun is deleted under identity (cf. Citko 2001). Both of these types of analyses in (2)a–b have been referred to as matching analyses, as there are two separate relative nouns. In a head promotion/raising account, the nominal head of a relative clause undergoes movement outside of the clause, as in (2)c (Brame 1968, Schachter 1973, Vergnaud 1974, Kayne 1994, Borsley 1997, Bianchi 2000, etc.). Unlike a matching analysis, there is only one relative noun which undergoes movement, and it is basically licensed in two positions.

| (2) | a) I don’t like the man1 [who/OP1 C John saw |

| b) I don’t like the man2 [[who/OP |

|

| c) I don’t like the [man2 [[who/D |

The matching analysis does not face the problem of a single noun receiving case and a theta-role in two positions, as it makes use of separate but co-indexed nouns. On the other hand, a raising analysis does not require a separate matching/coindexation operation. A thorough comparison of the various approaches, and their variants, is beyond the scope of this article,[2] but we adopt a version of the raising/promotion account in which new NPs with the same core noun lexeme can be formed through Internal Merge (IM), obviating the need for a separate matching operation. At the same time, we avoid the problem of a single noun receiving multiple theta-role and case assignments, through the use of separate D heads.

English relative clauses pose a non-trivial problem as they vary with respect to the content of the head and edge of the CP, as summarized in Table 1. None of the standard English relative clauses permit which/who that;[3] there being a well-known ban on doubly filled COMP (cf. Chomsky and Lasnik 1977, among others). Object relatives permit an empty COMP (indicated by Ø), but subject-relative clauses do not.

Examples of core relative clauses4

| Type of relative | Restrictions | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a) | Object relative | which/that/Ø |

|

| *which that | |||

| who(m)/Ø | |||

| *who that | |||

| b) | Subject relative | who |

|

| that | |||

| *who that | |||

| * Ø | |||

| c) | Object headless relative | what |

|

| *what that | |||

| d) | Subject headless relative | what |

|

| *what that |

This article presents a computational model of relative clauses based on linguistic proposals in the Minimalist Program (MP)[4] framework (Chomsky 1995, 2001).[5] We have a full computer implementation of the theory, verified across all core examples presented in this article.[6] The detailed step-by-step derivations computed by the program are too lengthy for inclusion in the body of this article; they may be found in the online Appendix, thus permitting the reader to verify the accuracy of our claims.[7] These derivations should also prove helpful to both linguists and engineers who wish to understand how the components of the theory interact in full detail. To our knowledge, this is the first computer implementation in the MP framework to accurately generate the complete set of basic subject and object English relative clause constructions, while also accounting for the usage of which, that, and who(m) in relative clauses.

1.1 Computational modeling of linguistic theory

The computational implementation of linguistic theory requires overcoming substantial barriers including (1) the careful selection of compatible sub-theories of grammar, a particularly important aspect as relative clauses involve both theories of the noun phrase (NP) and sentential structure (CP); and (2) theory mechanization, as linguistic theories are not specified with a mechanical architecture in mind. We take a linguistically-faithful automatic computer program to be one that autonomously assembles syntactic derivations (beginning with a list of primitive lexical items). The MP continues a long line of inquiry into the nature of the language faculty; this being a theory of competence, and our implementation concretely realizes the generative procedure. The problems of externalization, e.g., the mapping of linguistic representation into instructions to the sensory-motor system, and the problem of (efficient) parsing are important ones for which scientifically motivated answers are still limited. In this article, we limit our attention to the modeling of the generative procedure. We emphasize that the generative procedure does not automatically imply a psychologically realistic parser; it generates structures and sentences starting from a list of (user-supplied) lexical heads.[8]

Let us consider the general problem of concrete modeling. First, the theory should be precise and substantial enough to withstand scrutiny. It must be possible to algorithmically specify details down to the level of the linguistic primitives assumed in the MP framework, i.e., Merge (combing syntactic objects [SOs]) and probe-goal feature checking (agreement relations between features on two SOs). This is a non-trivial requirement as theoretical development in the MP framework proceeds apace and in a radical fashion.[9] Suppose we are able to select a sufficiently precise and broad theory. We also need to provide a computationally tractable implementation. For example, the implementation should not exhibit combinatorial characteristics, such as in terms of temporary syntactic ambiguity or lexical ambiguity, that require exponentially scaled resources, e.g., as the list of initial heads grows. Finally, in line with broader MP goals, we submit that an implementation of a particular phenomenon should be succinct in terms of the number of construction-specific theoretical devices required, ideally none. Every grammatical feature or data structure we specifically introduce to limit or control derivations is an additional burden, not only to acquisition and evolution but also with respect to the goal of simplifying core syntax. As we will show, our system is parameter-efficient in this sense. Since relative clauses embed sentential structure, any model of relativization must also include substantial modeling of sentential structure and therefore will be of broad relevance to general modeling of grammar.

We need to also motivate the MP framework itself. For theoretical linguistics, this requires little justification: the goal of a universal theory built around binary Merge has resulted in a large body of work (since Government-Binding theories of the late seventies) that has contributed greatly to the understanding of language. However, there remains a substantial gap from theoretical to computer models. Müller (2015, 35) writes that there are no “large-scale computer implementations that incorporate insights from Mainstream Generative Grammar.” We believe we have substantially narrowed that gap by clearly demonstrating that theoretical achievements can be implemented. Furthermore, Müller (2015, 37) writes that the system presented in Fong and Ginsburg (2012), which is similar to the system presented in this article, “neither parses nor generates a single sentence from any natural language”. We wish to clarify that we compute linguistic derivations which are spelled out as phrases and sentences of English.

We do not employ a phrase structure grammar-based formalism in this article, choosing instead to implement devices described by theory directly. We are aware that there is a substantial body of work centered around the Minimalist Grammar formalism, e.g., Stabler (1997, 2011), including computational implementations such as Hale (2003), Harkema (2001), and Torr et al. (2019), and Indurkya (2021). A detailed comparison of our work with an equivalent Minimalist Grammar is a topic that is beyond the scope of this article.[10] There are also proposals for relative clauses in other linguistic frameworks such as Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG), e.g., Sag (1997), that lend themselves to computational implementation, e.g., Müller (2015). Sag (1997) takes a construction-specific approach to relative clauses, slicing them up into a sort hierarchy.[11] In Chomsky’s MP, construction-specific rules are frowned upon: the goal being to reduce constructions to universal primitives. We also include key examples from Sag (1997) and show how they are handled in the MP framework.[12]

1.2 The Minimalist Program

It is important to note that the MP is a program of research inviting many different theories under the umbrella of eliminating complex operations in favor of the simplest possible operations that can be conceived (thereby contributing to evolutionary plausibility). Our model follows much of the theory outlined by Chomsky (2000, 2001, 2008). We review the core assumptions and mechanisms.

At the heart of the theory is binary set-Merge, the simplest possible operation is taking two objects that, when iterated, create a hierarchical structure. Merge can result in either a symmetric structure, resulting from set-Merge, or an asymmetric structure, resulting from pair-Merge (Chomsky 2000, 2004). Pair-Merge is asymmetric in that one of the two merged objects in Pair-Merge is rendered inaccessible to further operations (not so in set-Merge). Set-Merge can be internal or external. IM encodes displacement from within an SO, and External Merge (EM) combines two distinct SOs, encoding argument structure. As a concrete example, EM applies to an object DP and a transitive verbal root V forming the set {V, DP}, followed by EM twice to form the theta configuration {DP, {v*, {V, DP}}}. v* is a verbalizer that licenses the outer DP subject. For unergatives, e.g., sleep, the equivalent configuration is {DP, {v, V}}}, and v is the corresponding verbalizer.

In Chomsky (2000), agreement is implemented using (mostly) local c-command between a probe and a goal. A probe searches top–down into its c-command domain. T (tense), a probe, has unvalued phi-features (person, number, gender) that must match valued phi-features on the goal. For example, in {T, {DP, {v*, {V, DP}}}}, T finds the first DP, the subject. Similarly, unvalued phi-features on v*, a probe, match corresponding valued features on the DP object. Implicit in this model is that features that remain unvalued will crash a derivation. In this article, we use uF to represent unvalued F, F a feature: e.g., uT will be an unvalued T feature that needs to be valued in the course of a syntactic derivation.[13]

In our model, movement is generally considered to be feature-driven.[14] Heads may have an Edge Feature (EF) that permits movement to the edge of a phrase. For example, in (3)a, the EF on T results in the movement of a subject from a v*P internal position to the edge of TP, and an EF on an interrogative complementizer, CQ, forces the movement of a wh-phrase to C in (3)b (for visible wh-movement).

| (3) | a) I T[EF] read |

| b) What CQ[EF] did you read |

We assume that theta-roles are associated with a determiner head D (rather than N).[15] For example, when V merges with an object DP, V assigns a theta-role to the DP, which lands on the D head of the object.

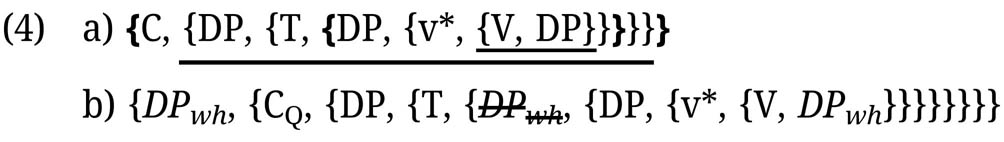

We also adopt Chomsky’s Phase Theory (Chomsky 2001). Assuming the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC), once a phase is complete, constituents inside the complement of a phase head are invisible to operations (highlighted by underlining). However, constituents displaced to the edge of a phase may be accessed outside of the phase. Phase heads are usually assumed to be transitive v* and C (possibly, also D). Thus, v*P and CP (highlighted by boldface {…}) are the phases in (4)a. Cyclic movement must involve iterated displacement through the edge of each phase, as in (4)b.

Given the variety of possible feature mechanisms, one should seek to constrain the grammatical feature system that shapes syntactic derivations as much as possible, as suggested by Chomsky’s MP.[16] Formal language theory tells us that Turing-computability, i.e., arbitrarily powerful devices, can be built on formal features (Black (1986) and Johnson (1988)). The use of formal features should be kept to a minimum, and conceptually unnecessary ones should be eliminated from the theory.[17] Narrow syntax may make use of other features relevant to the interfaces. For example, we assume Q (question) and wh will be read at the semantic interface, and inflectional Case and phi-features will be read at Spell-Out. However, formal features, e.g., Edge, or its earlier incarnation, the EPP (Extended Projection Principle)[18] or ECM (Exceptional Case Marking), are arguably fundamentally limited to Merge syntax, and therefore should be deleted prior to Interpretation and Externalization.[19] The introduction of new features during the course of a derivation is also not permitted. Examples of such devices from the past include indices, as used in Binding theory, or the γ-feature, from the Barriers framework (Chomsky 1986).[20]

We posit, following fundamental MP assumptions, that there is a one-time selection of heads into a Lexical Array (LA) from the lexicon for Merge, but no explicit staging of features (as in MG, see note 10). In our implementation, the LA is ordered as a queue of heads (for input to Merge) purely for computational convenience.[21]

2 The basic model

In this section, we briefly summarize the theoretical aspects underlying our account.

We implement a revised version of Gallego’s (2006) relative clause analysis, which builds on work by Pesetsky and Torrego (2001) (henceforth P&T). P&T propose that nominative case results from a checked uT feature (uT = uninterpretable T) on a head D. The head T locally c-commands the subject DP and checks the DP’s uT feature, resulting in nominative Case. Embedded C also possesses a uT feature, which can be checked in two ways. One way is by raising T to the edge of C and T checks the uT on C. An alternative way is by raising the subject DP to the edge of CP, in which case the already checked uT on D of the subject checks uT on C. When checked by T, the uT feature on embedded C is pronounced as that (e.g., Mary thinks that Sue will buy the book; P&T 2001, 373). When a nominative subject raises to the edge of CP to check the uT feature on C (e.g., Mary thinks Sue will buy the book), there is no pronunciation of that.

Although in principle, two methods for checking the uT feature on C are available, P&T utilize economy to account for that-trace effects and the English subject/object wh-movement asymmetry.[22] In principle, multiple Agree operations are possible in this system. Abstractly, in (5)a, uF1 and uF2 on X are checked by Y and W, respectively. In (5)b, Z checks both uF1 and uF2 at once instead. Economy dictates that we prefer a single operation (over multiple operations) and, therefore, (5)b over (5)a.

| (5) | a) Agree(X[ |

| b) Agree(X[ |

Note that the preference for a single Agree relation over a multiple Agree relation does not make any predictions about the presence of that in cases where both are possible, as in (6)a. Note that P&T assume that in constructions in which there is wh-movement out of an embedded clause, there is a uWh feature in a non-interrogative C that hosts a wh-phrase. The uT feature on C can be checked by T, (6)b, in which case that is pronounced. The uT feature can also be checked by the subject, (6)c in which case that is not pronounced. Therefore, that is optional, and there is no preference for or against that.

| (6) | a) What did John say (that) Mary will buy? (P&T 2001:370) |

| b) Whati did John say [CP

|

|

| c) What

i

did John say [CP

|

Gallego extends P&T’s proposal to relative clauses, i.e., that that is the pronunciation of uT in C. In addition, Gallego assumes that a relative clause C has a uRel feature that is checked by a relative DP containing a corresponding iRel (i = interpretable) feature. Economy, following P&T, comes into play if both uT and uRel on C can be checked by a single goal. Gallego’s analysis is noteworthy in that it attempts to provide a unified account of relative clause formation and the distribution of which/who(m)/that/Ø.

According to Gallego, in (7)a, who man originates in the subject position of the clause, from where it moves to the relative CP edge, followed by further movement of man to a higher position in the CP. Assume the subject relative D who contains both an iRel feature and nominative case. Applying economy, who checks both uT and uRel on C via a single Agree relation, as shown in (7)b. There is no pronunciation of that crucially because who, not T, checks uT on C. Gallego proposes that uT and uRel have EPP subfeatures, a complication that we do not adopt and that forces who man to raise to the edge of the CP. Gallego also proposes that there is an extra projection, referred to as cP, in the left periphery that ‘introduces a subject of predication (Gallego 2006, 157)’. This c has uPhi features with EPP subfeatures. The uPhi probe for matching phi-features that are interpretable and the uPhi find iPhi on man in (7)a–b. The EPP sub-feature of uPhi forces man to raise to the edge of the cP. Example (7)a with that is blocked by economy: pronunciation of that would require uT on C to be checked by T, and uRel on C to be checked by who, separately. However, economy dictates who man checks both uT and uRel features on C simultaneously.

| (7) | a) the man who loves Mary/*the man who that loves Mary |

| b) [DP the [cP man j c[uPhi,EPP] [CP [ DP who man j ] i C[uT,EPP] [uRel,EPP] [ DP who man j ] i T [ DP who man j ] i loves Mary]]]]] (Adapted from Gallego 2006, 156) |

An issue is that Gallego’s analysis requires an extra cP projection in the left periphery. It is also not entirely clear why c can attract N from inside of a relative D and not the head of the DP itself, viz. D.

In (8)a, Gallego assumes the subject boy contains a null D and, following Chomsky (2001), that a null D must remain in situ. Furthermore, the uRel on C (conveniently) lacks an EPP sub-feature so that uRel on C is checked by iRel on null D without triggering movement. The uT’s EPP sub-feature then causes T to raise to C and be pronounced as that. (Note that this analysis also implies that the relative DP boy does not move to Spec-T either, as it has a null D.)

| (8) | a) the boy that called Mary |

| b) [DP the [cP boy j c[uPhi,EPP] [CP that i + C[uT,EPP][uRel] Ti [ DP D REL boy j ] called Mary]]] (Adapted from Gallego 2006, 158) |

This analysis has two potential problems. First, it requires a stipulation that a relative DP with a null D cannot move. Furthermore, there is lexical proliferation for C containing uRel. As uRel typically has an EPP sub-feature, this must be modified for relatives containing a null D, as they do not move in Gallego’s account. Therefore, C with uRel must come in two versions: one with an EPP subfeature (as in (7)b) and one without an EPP sub-feature (as in (8)b).

Gallego’s analysis is also unable to account for the ill-formedness of (9)a; it has difficulty accounting for doubly filled Comp effects. As the structure (9)b indicates, T should be able to check uT on C, resulting in the pronunciation of that. Because the relative DP is an object, it does not have nominative case, and thus, it is unable to check uT on C. Hence, that must be pronounced, as in (9)a. But (9)a is ungrammatical in standard English.

| (9) | a) *The car which that John sold. (Gallego 2006, 160) |

| b) [DP the [cP carj c[uPhi,EPP] [CP[DP which carj]i thatk + C[uT,EPP][uRel,EPP] Johnz Tk Johnz sold [DPwhich carj]i]]] |

We adopt a modified version of Gallego’s core proposals about uT feature checking on a relative C and about economy. While we follow Gallego’s insights regarding uT and uRel feature checking, we omit the extra cP projection and we do not utilize EPP subfeatures. We are able to account for the distribution of the relative D and a noun in the examples above, including the ban on *who that in (7). Also contrary to Gallego, we have no stipulation that a DP with a null D is unable to move. Our analysis, to be discussed below, is able to account for the ill-formedness of (9)a, and we also extend this analysis to account for headless relatives (which Gallego does not investigate) and genitive relatives, as well as other related relative clause types. Note that we assume the judgments of standard English about relative clauses; in particular, no doubly filled COMP. However, there are varieties of English that permit a doubly filled Comp, suggesting there may be some dialectical variation in whether or not a relative D can check a uT feature. We discuss this in detail in Section 5.

Suppose all relative D heads check a uRel feature. We assume there is variation in whether or not a relative D may also check a uT feature on C. When relative D can check both a uRel and uT feature, pronunciation of that (only when uT on C is checked by T) is blocked due to economy. Only when relative D is unable to check uT on C, then T can (raise and) check uT on C and that can be pronounced. Finally, we use an unvalued D feature to trigger extraction of the relative noun, termed “relabeling” in the study by Cecchetto and Donati (2015).

Consider sentence (10)a and its subject relative counterpart in (10)b.

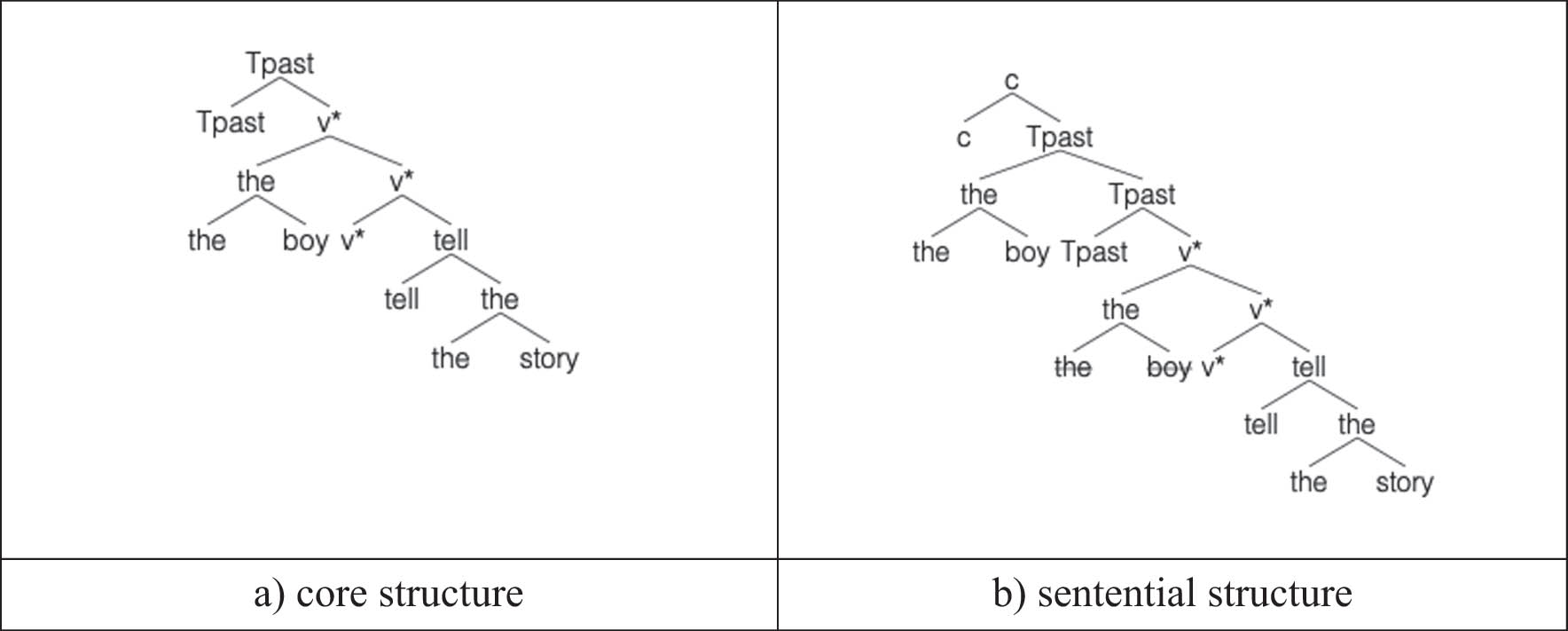

| (10) | a) the boy told the story |

| b) the boy who told the story (Keenan and Hawkins 1987, 63) |

(10)a has the core structure shown in Figure 1, typically assumed in Minimalist syntax.[23] Root tell selects for an internal argument, the story, and transitive v* combines with the phrase headed by tell to form a basic verb phrase. Case-Agreement proceeds by minimal c-command. For example, v* c-commands and values accusative Case on the internal argument. v* also provides for an external argument (EA) position in its specifier, occupied by the boy. Tpast selects for v*P and c-commands the EA, valuing nominative Case. In English, Tpast also provides for a surface subject position that must be filled, the so-called EPP property. In Figure 1b, the boy raises to the edge of TP. Only the highest copy is pronounced, and unpronounced copies are indicated by strikethrough. As part of Case-Agreement, Tpast picks up number and person feature values associated with the EA, resulting in English subject–verb agreement. The heads Tpast, v*, and the root tell combine at Spellout to form told. (Note that we indicate C as c, Crel as crel, and the relative determiner Drel as drel in our diagrams.)

Example of syntactic structure for the boy told the story.

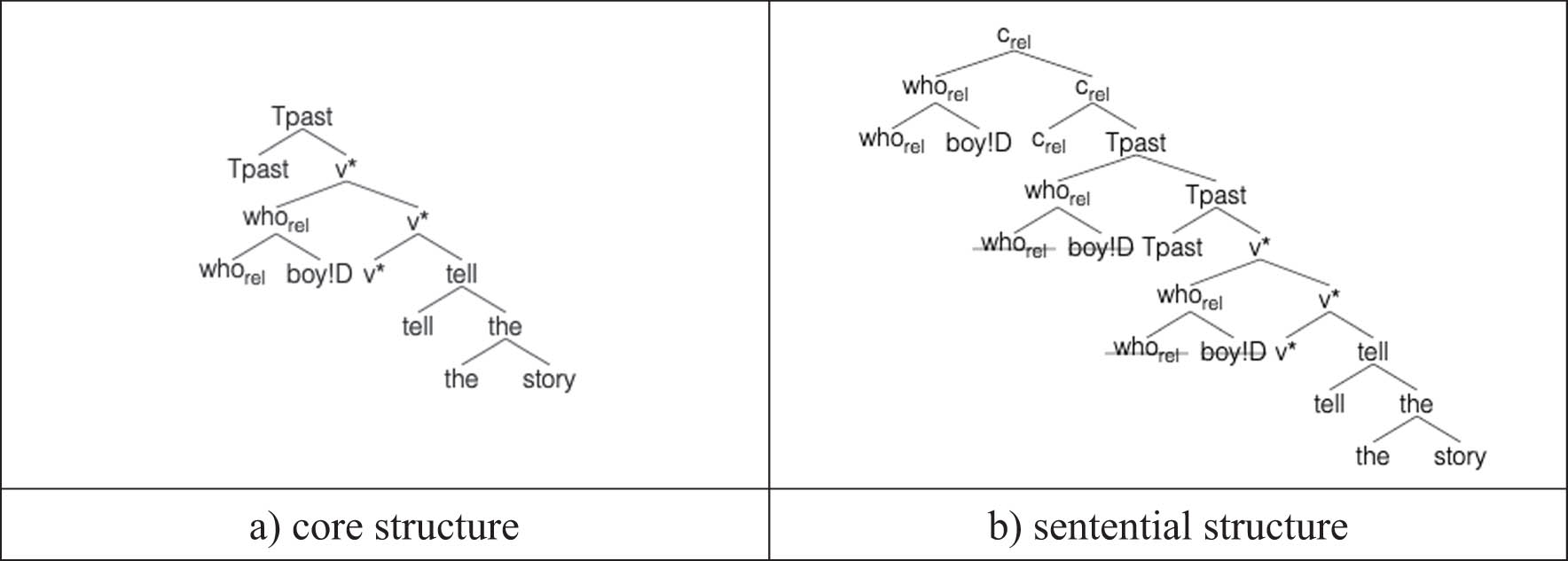

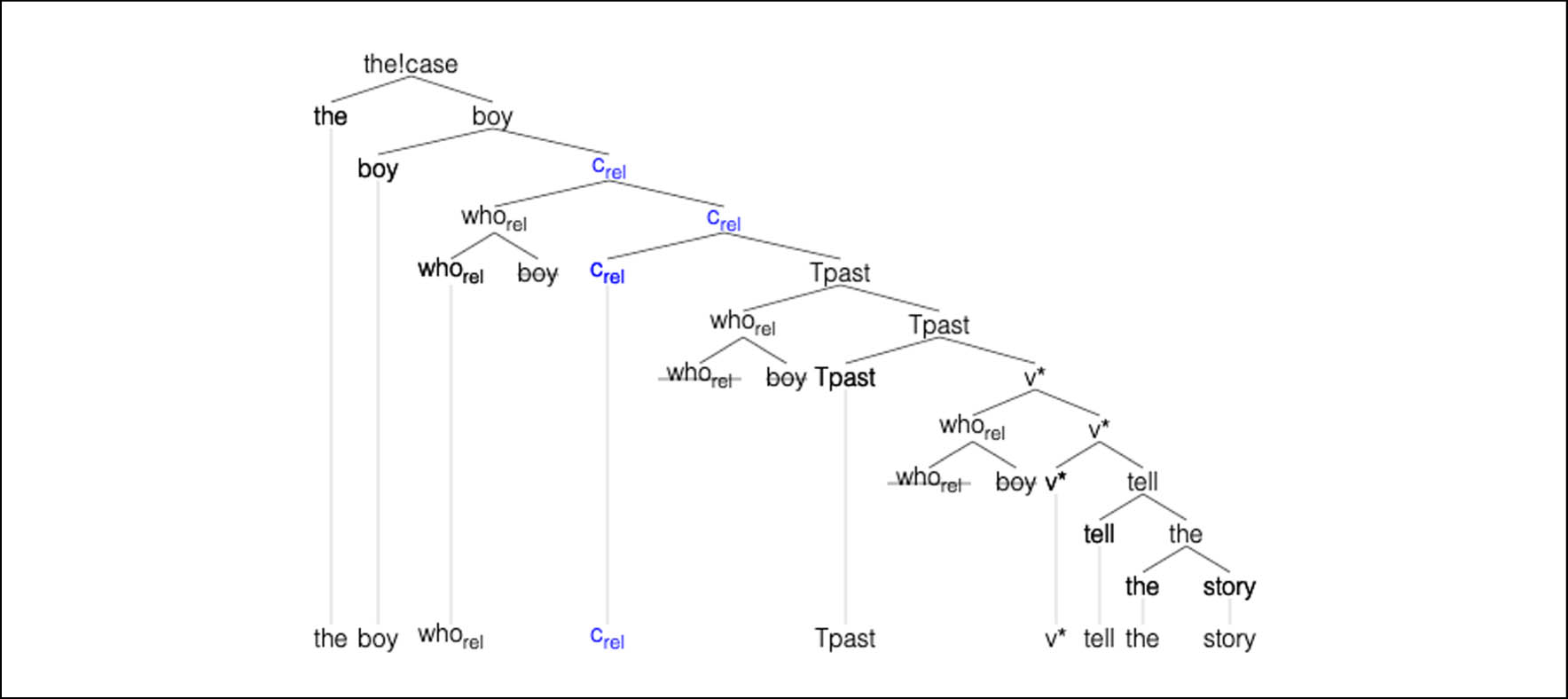

Example (10)b has the same underlying core as (10)a, with two crucial featural differences that will drive relativization. We assume rel to be a formal feature marking the DP that undergoes relativization, which is the EA headed by whorel in Figure 2. The clausal head Crel attracts this EA (containing rel) to its edge. We crucially assume the noun boy has an unchecked D feature (uD), indicated by !D, normally checked through Merge with a determiner D. We assume all (and only) relative Ds lack the ability to check uD. Thus, boy may subsequently emerge from sentential structure to head a new NP, and its unchecked D-feature will be checked by the (regular) determiner the, as shown in Figure 3.[24] As only the highest copy may be pronounced, vertical lines in Figure 3 are used to pick out possible pronounced elements of the frontier of the structure.[25]

Relative clause structure for the boy who told the story.

DP structure for the boy who told the story.

To summarize, uD on N, if left unchecked, enables N to (raise and) relabel a relative clause. N then gets its uD feature checked by a higher D in a regular sentence. The feature-checking details regarding uD, uT, and uRel are summarized in Table 2.

Feature checking

| Feature | Checked by |

|---|---|

| uD on N | iD of D (Drel is unable to check uD) |

| uT | T (pronounced as that), by nominative case (which is a form of T), or by certain relative Ds |

| uRel on Crel | iRel of Drel |

A reviewer asks how examples such as (11) in which the relative book on syntax, not a simple head, can be accounted for under this relabeling proposal. As the PP on syntax is an adjunct, the relevant structure is 〈book, {on, syntax}〉, where book and the PP on syntax are pair-Merged, as indicated by the angle brackets. Since pair-Merge is asymmetric, the adjunct on syntax is essentially invisible, and book on syntax is treated exactly the same as the single-head book; thus, it can relabel.[26]

| (11) | the [book on syntax] that I read |

Relativization productively occurs with external and internal arguments, and even oblique, i.e., non-core, arguments, as will be illustrated in the following sections. In each case, the mechanism is the same, i.e., a relative determiner (Drel) heading the argument to be relativized is attracted by a relative complementizer (Crel). There is no theta role clash (or theta criterion violation) with this movement-based account as we assume theta roles are hosted in D.[27] In Figure 3, external the (not boy) bears the theta role assigned to the entire DP when it is Merged as an argument in a higher clause, and the lowest copy of who rel (not boy) bears the theta role assigned to the EA of tell. As the and who rel are distinct, there is no theta problem.

We next summarize the algorithm used to derive the structure in Figure 1. Assume all sentences involve a selection of heads from the Lexicon to feed Merge. A head may bear both formal features, e.g., D and Case on nominals (discussed previously), and unvalued phi-features (person, number in English) on T and v*. Unvalued formal features must be valued in the course of a derivation (or else the derivation will not converge). Heads may also bear interpretable features, e.g., Q on wh-words and intrinsic phi-features on nominals, e.g., first-person-singular on I/me. A head that probes for matching values gets only one opportunity to value its unvalued formal features, viz. when it is first Merged. If a head H merges with a phrase YP, as in HP = {H, YP}, YP is the c-command search domain for H’s formal features. Once HP is merged with another head or phrase, H is inactivated as a probe and cannot search again. As this policy is strict, leftover unvalued features on H will crash the computation, and no convergent structure will be produced.

As the algorithm selects only the first head of a sequence for Merge, heads selected from the Lexicon are sequenced precisely for proper assembly.[28] For (10)a, the sequence of heads that derives the structure shown in Figure 1 is given in (12)a.

| (12) | a) [story, the, tell, v*, [the, boy], Tpast, C] |

| b) [story, the, tell, v*, [whorel, boy], Tpast, Crel, the] |

Sequence (12)a is read from left to right with the algorithm selecting the appropriate Merge action based on the current state, i.e., the SO constructed so far and the first input head.[29] In most cases, there will be only one possible Merge action per state. Non-determinism, i.e., more than one possible Merge action, is limited solely to linguistic choice points; e.g., the option to pied-pipe a preposition with a DP in English or the T-to-C option described in this article, both producing derivations that separately converge.[30] Let us sketch the steps for Figure 1: step (i) Merge combines story and the, forming a DP; (ii) tell, the next head in the list, merges with the DP formed in (i), we obtain {tell, {the, story}} (a VP); (iii) the next head, v*, merges with the VP from (ii), forming {v*, VP}; (iv) the sub-list [the, boy] initiates a sub-computation producing {the, boy}, which replaces [the, boy] in the list of heads, (v) the v* phrase in (iii) Merges with {the, boy}, the EA, forming {EA, {v*, VP}} (a v*P); (vi) the head Tpast Merges with the v*P from (v), forming {Tpast, v*P}; (vii) English T has an EF which triggers IM for {Tpast, v*P}. By minimal search, EA, being the highest accessible DP, is raised, forming {EA, {Tpast, v*P}}. In step (viii), the last head, C, Merges to head the clause. Note there is no ambiguity as to which sub-phrase must label the merged structure at each step. Therefore, the derivation is deterministic (and efficient in this sense). Minimal search itself is implemented using a stack to maximize the efficiency of the search. Phrases with unvalued features (or rel) are placed onto a stack when merged initially. When IM is triggered or a head probes to value unvalued features, generally only the top stack element is consulted. For IM, the top stack element is extracted, i.e., raised. As a goal, the top stack element features must be used (to satisfy the probe). Hence, minimal search typically involves no search at all, and minimal c-command naturally results.[31] The derivation of Figure 3 proceeds similarly with the sequence of heads in (12)b. One crucial difference between (12)a and (12)b is that Crel in (12)b possesses EF, triggering IM after the equivalent of step (viii), and the EA {whorel, boy} raises (in a similar fashion to wh-phrase fronting triggered by CQ).

The system that we implemented is based on the feature-driven Merge model of Chomsky (2000, 2001, 2008, and other work).[32] In this work, Chomsky assumes there is a one-time selection of items from the Lexicon to form an LA. Merge of Lexical Items is recursively applied to form an aggregate SO. An SO can be selected and Merged from the LA (EM), or it can be Merged from within the current SO; this is the process of movement (IM). The term Workspace refers to the LA and SO at any given stage. For a convergent derivation, the Workspace must consist solely of a single SO, with formal features eliminated. Any remaining uninterpretable features in the SO, or leftover LA items, will crash the derivation.

Multiple threads of derivation are in principle possible if there are multiple possible operations, i.e., choice points, at any given point in the derivation. An example of a theoretical choice point that we use is the possibility of uT on C being checked either by movement of T (resulting in pronunciation of that) or by nominative case on the subject (in which that is not pronounced). In such cases, e.g., “the man (that) John saw,” the model correctly generates two different structures starting from the same LA. Another linguistic choice point will permit the option of pied-piping for cases like “the man to who/whom I talked” and “the man who/whom I talked to.” Note that we assume that who and whom are inflectional variants of the same word who. Again, two different structures will be generated from the same LA. The model we describe has only linguistic choice points predicted by the theory; there are no temporary ambiguities attributable solely to the algorithm or data structures required. In this sense, our model is maximally efficient with respect to the theory.

Assuming we begin, as does Chomsky, with a one-time LA, our LA is selected in order, purely for computational efficiency.[33] As the LA is ordered as a queue, the current SO has the choice of EM with the first item in the sequence, or ignoring the LA, the choice of IM, i.e., selecting a sub-SO from within itself. Based on the current SO and the head currently first in line in the LA, our machine will correctly select the right operation one step at a time to converge on the intended SO. (In the case of non-convergence, the machine will end up in a state with no possible continuation, call this a crash.) Lexical items selected from the LA may have unvalued and valued features. In the case of an LA head with an unvalued feature, when it is first Merged to the current SO, it must probe the existing SO for a matching valued feature. For efficiency, we assume all required probing for valued features can be accomplished during this first Merge time; i.e., no second chances are permitted nor needed.[34]

Our model also incorporates an operation of Last Resort that enables an unlicensed relative head to move to the edge of a phase. If heads with remaining unvalued features are not to crash the derivation, the phrases they head must move to the edge of the Phase to save and keep the derivation going. This Last Resort operation happens automatically. A general remark about feature-driven movement is in order at this point: a head with an EF licenses movement to its phrase edge. Without it, movement is not permitted. Hence, for Last Resort to operate, either we must assume all Phases have an optional EF, or movement is generally licensed to all Phase edges.[35]

The model that we created is complete in the sense that all convergent derivations are grammatical and all grammatical sentences in this article are generated. For a summary of the basic operations of our model, please see the Appendix.

3 Derivations of basic relative clauses

Our model crucially accounts for the (im)possibility of that in a variety of relative clauses. Consider (13), in which that can be either pronounced or unpronounced.

| (13) | the book that/Ø I read (Gallego 2006, 151) |

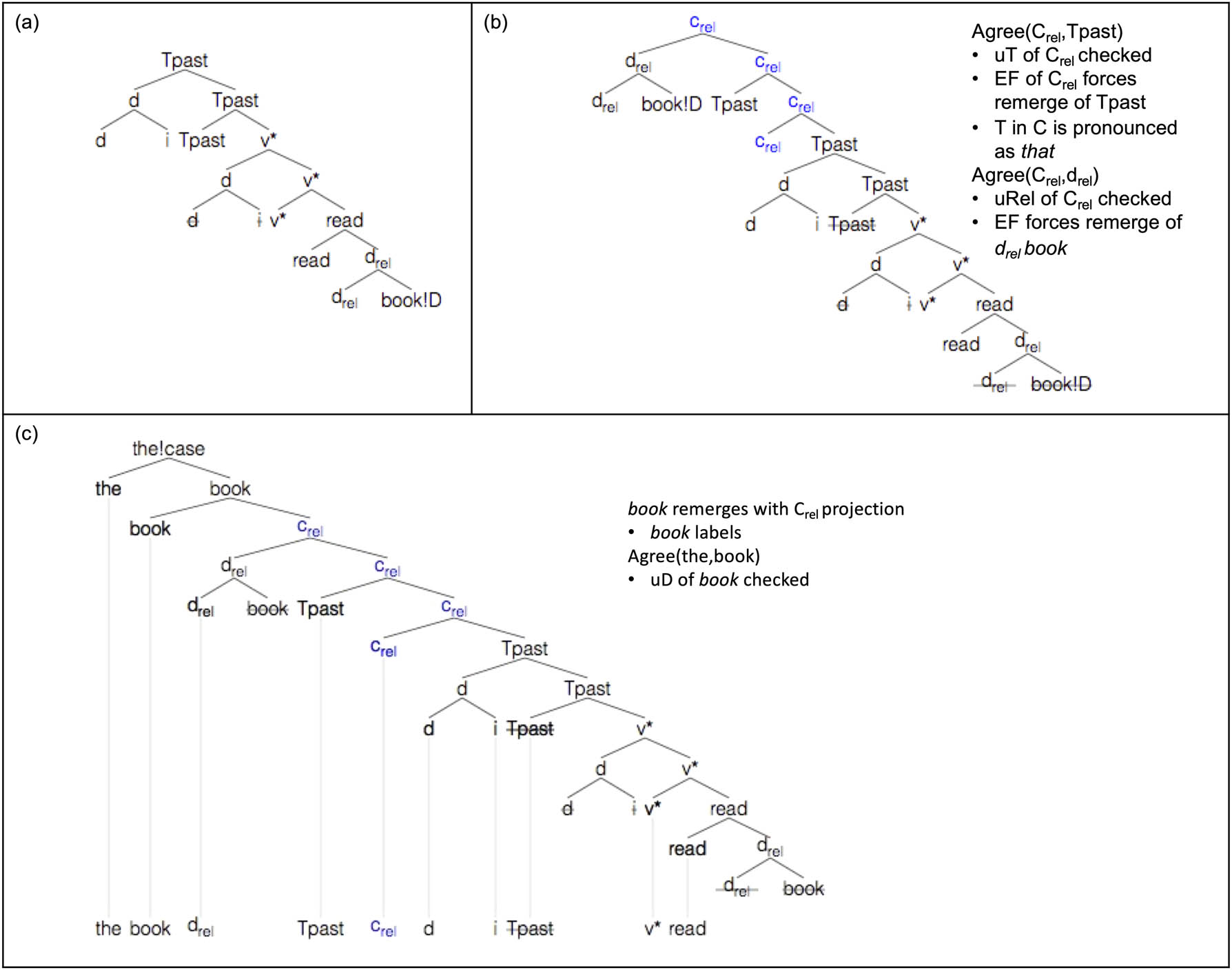

Snapshots of the derivation of (13) with that are shown in Figure 4. In Figure 4a, TP is the current SO, and Crel is about to be Merged from the LA. In Figure 4b, Crel has been Merged, and its unvalued features uRel and uT have been checked by Drel and T, respectively. uT on Crel, checked by T, results in pronunciation of that. As Crel possesses an EF, the DP {Drel, book} raises to the edge of CP. We assume Drel cannot check the D feature on the noun (in this case, book), freeing book to raise as shown in Figure 4c. Book is a head and therefore labels{book, CP}. Finally, the external D is merged, checking uD on book. Note that the diagram correctly indicates Case (shown as !case) is currently unvalued on the external D head the. Its Case will be valued via probe-goal agreement when the relative clause is integrated into a larger environment, as in “They like the book that I read.”

Derivation of the book that I read.

The corresponding derivation of (13) without that is given in Figure 5 – in this case, the option of uT being checked by the subject (instead of T) is taken, so that is not pronounced. The remainder of the derivation, as illustrated in Figure 5a and b, is the same as in the case with that, described earlier.

Derivation of the book Ø I read.

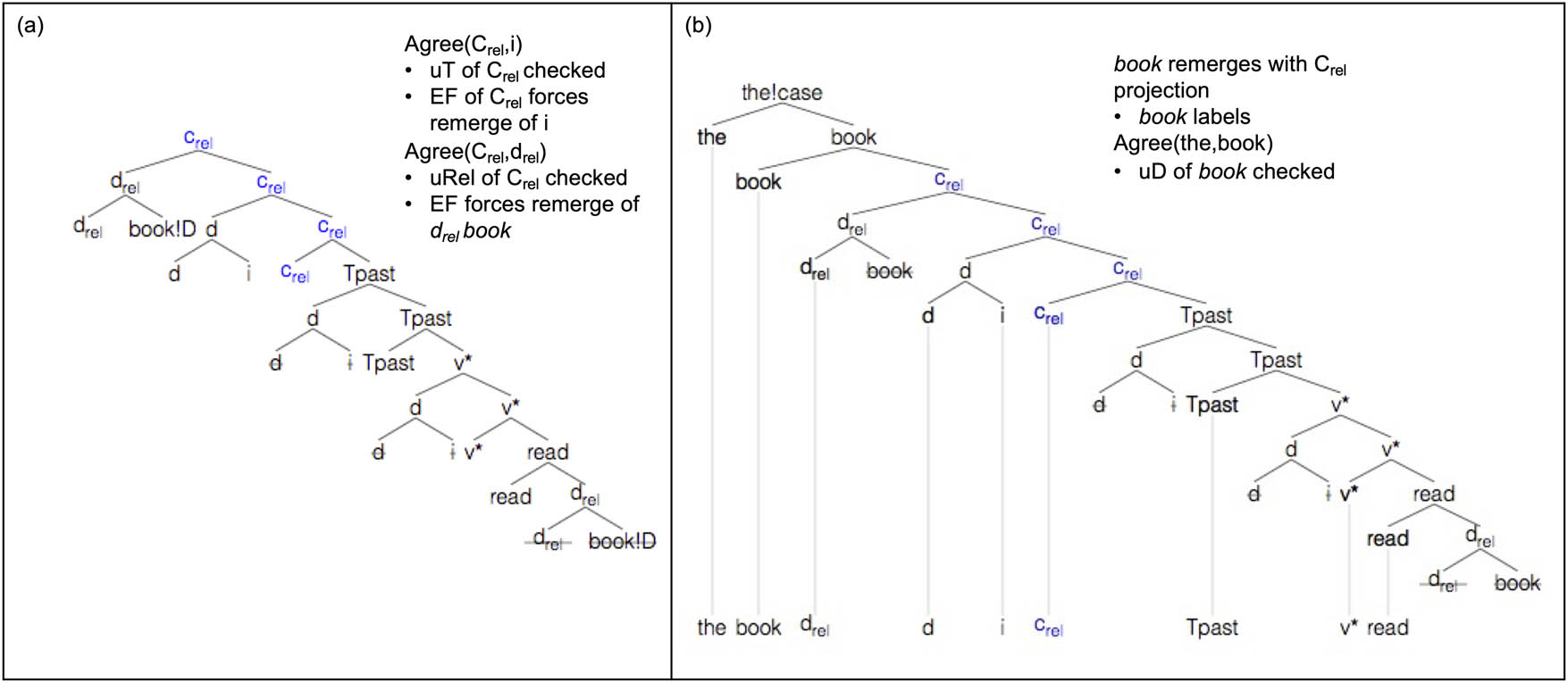

Example (14) contains a covert Drel within a PP headed by to. The two licit derivations are shown in Figures 6 and 7. We assume talk to is a verb-particle construction, where to is a particle and Case is valued by v*.[36] In this case, pied-piping is generally blocked, as *the man to that I talked and *the man to I talked are ill-formed. One explanation for the lack of pied-piping here is that to followed by an empty category disallows pied-piping (Chomsky 2001, 28).

| (14) | the man that/Ø I talked to |

Derivation of the man that I talked to.

Derivation of the man Ø I talked to.

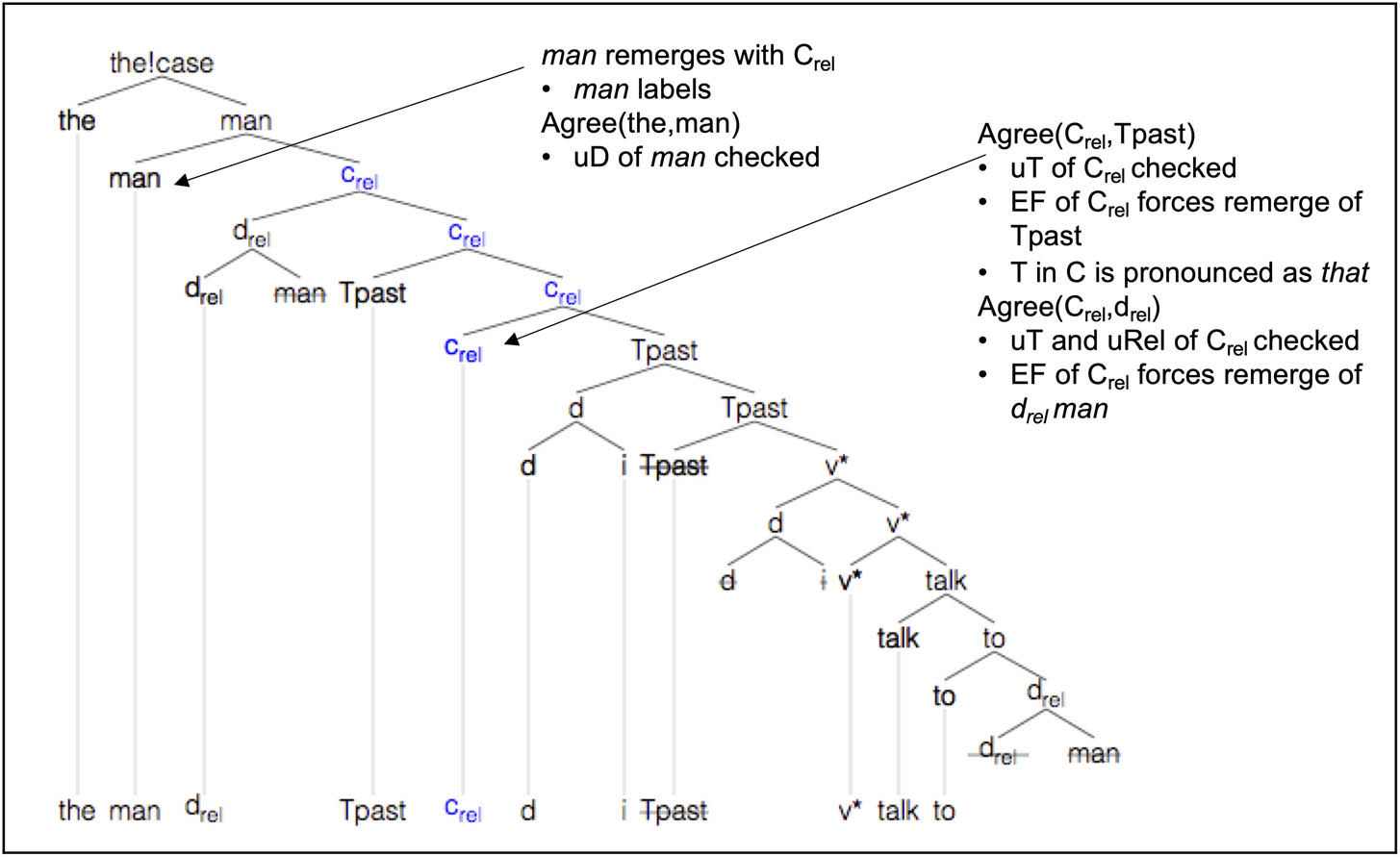

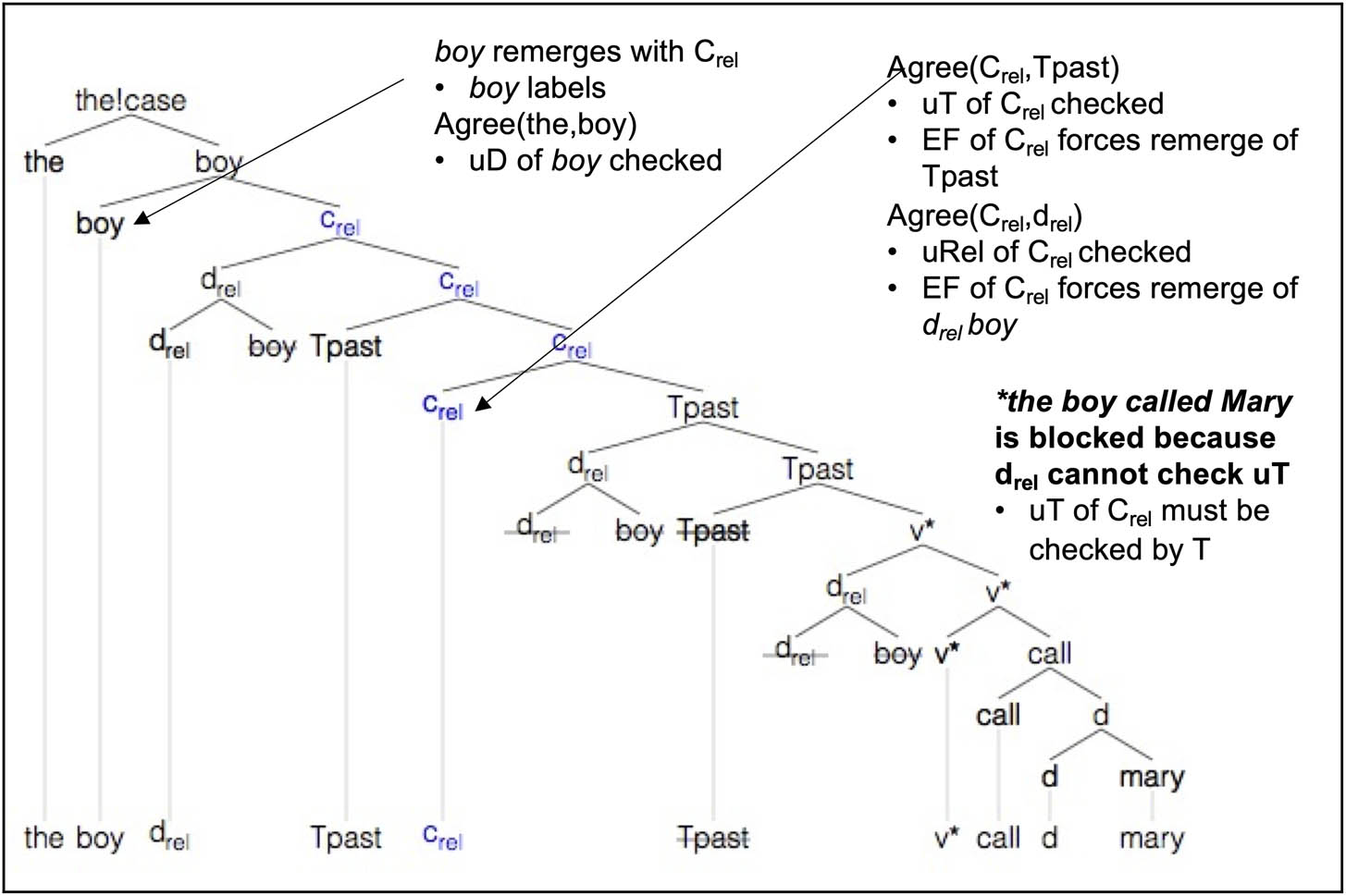

Consider the case of the subject relative in (15)a–b.

| (15) | a) the boy that/who called Mary |

| b) *the boy called Mary (ill-formed as a relative clause) |

In the previous examples, i.e., (13) and (14), Drel is covert. (15)b can be explained if covert Drel generally cannot check uT on Crel. Then the only available option is for T to raise to check uT on C, obligatorily pronounced as that in (15)a, and illustrated in Figure 8.[37] The covert/overt distinction neatly divides uT (on Crel) valuation; in short, covert Drel cannot check uT and overt Drel can. Thus, the wh-relative counterpart of (15)b, i.e., the boy who called Mary, is available.

Derivation of the boy that called Mary.

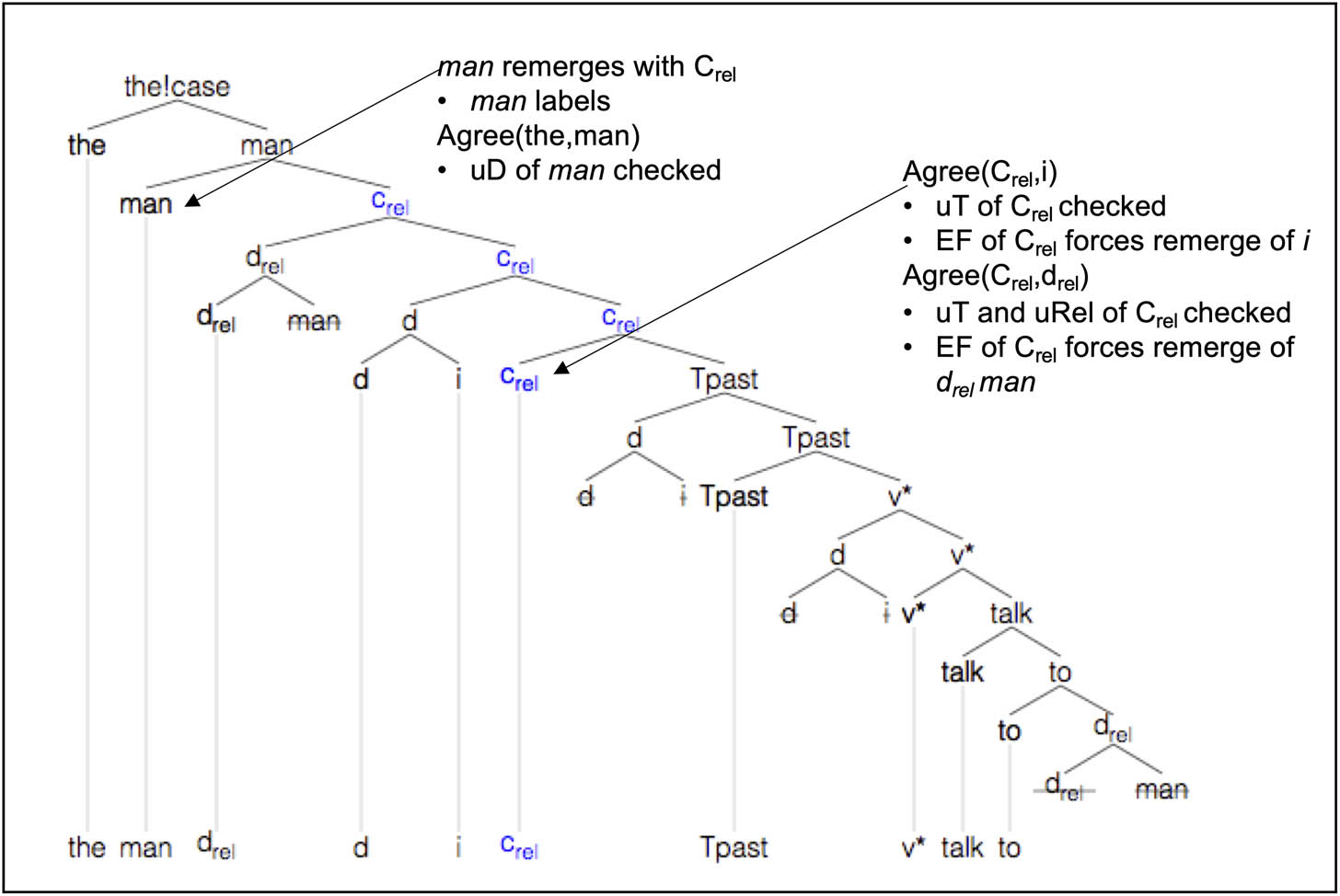

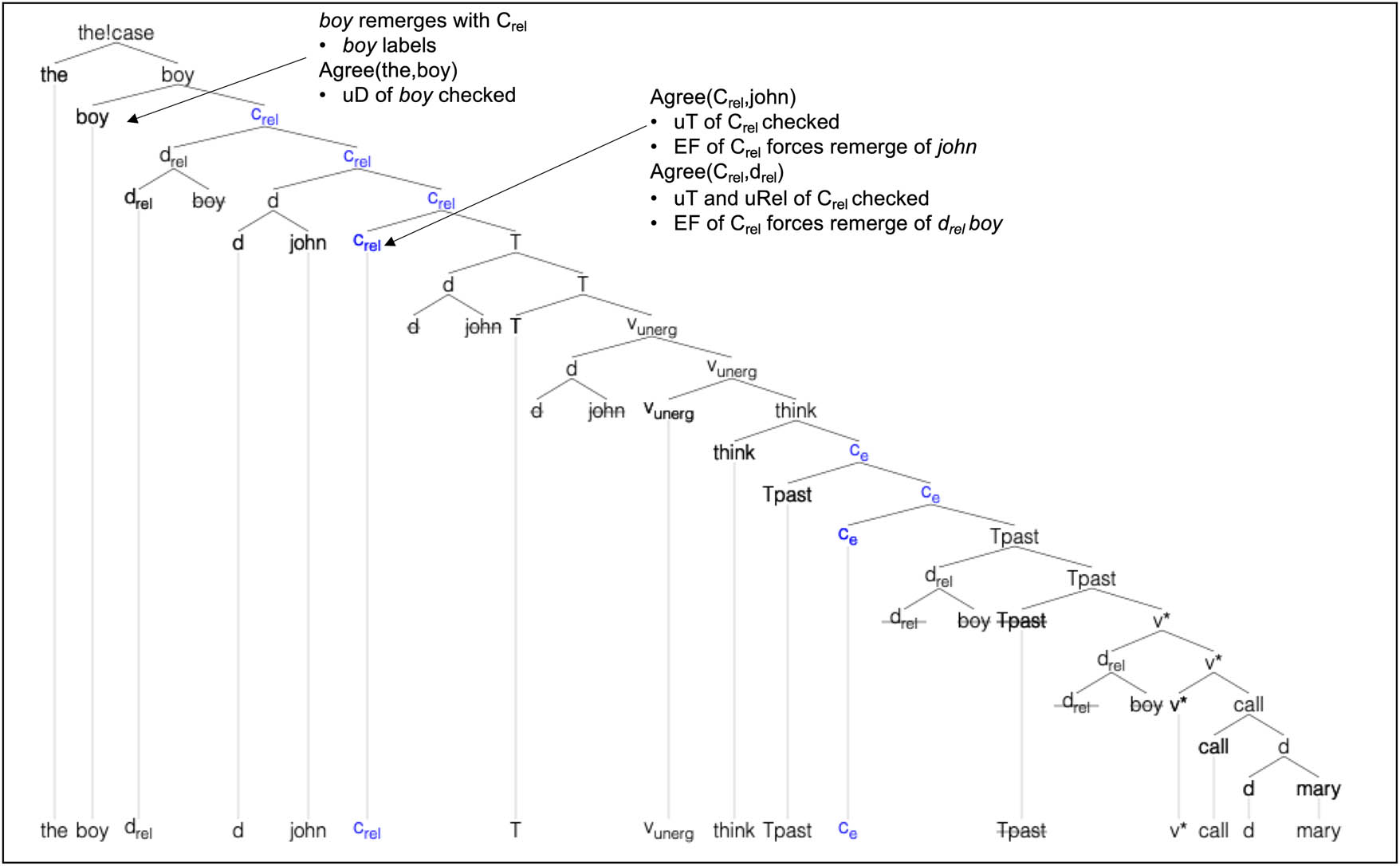

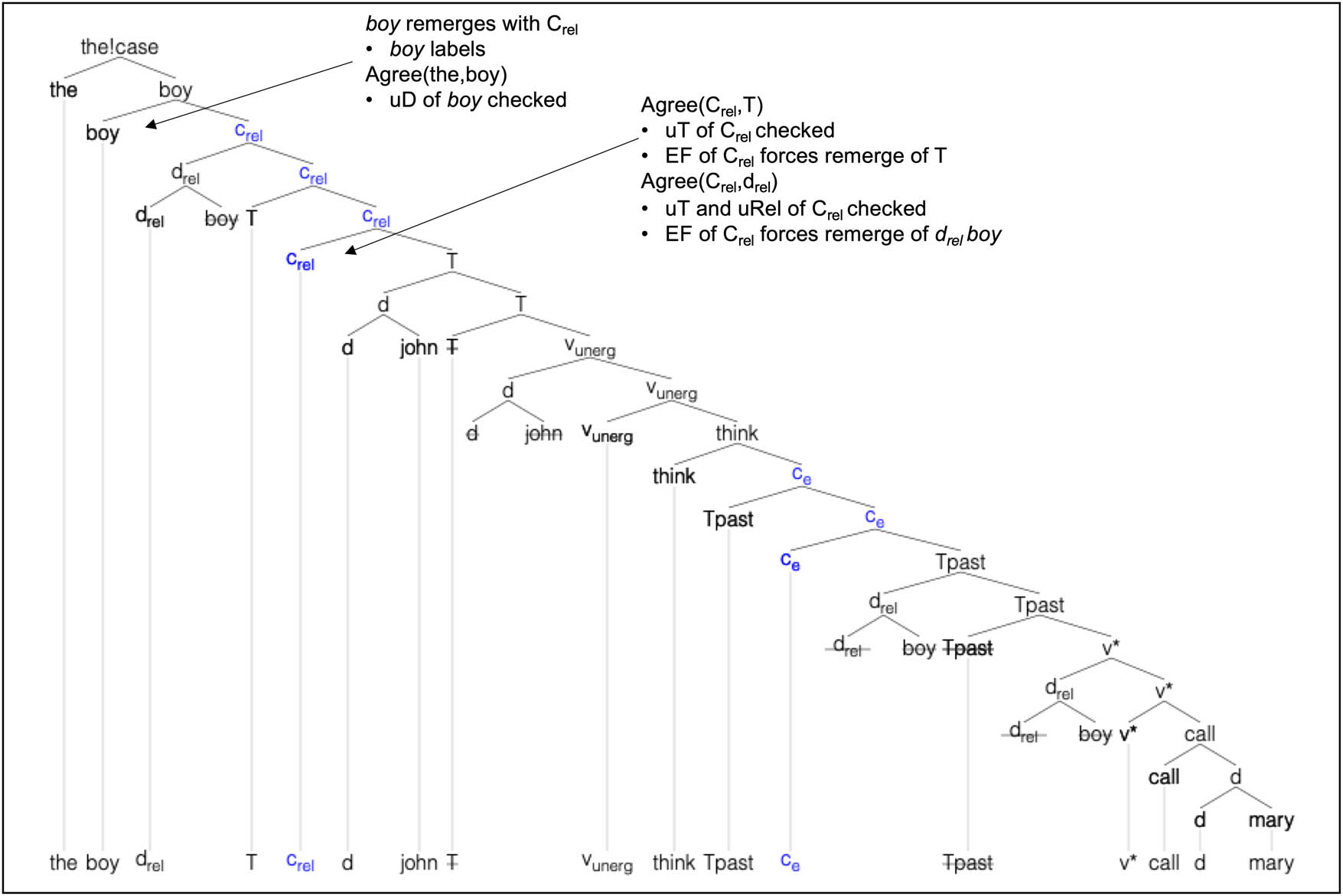

Our model can also account for long-distance subject relative clauses such as (16)a.

| (16) | a) the boy (that) John thinks (that) called Mary (from an anonymous reviewer) |

| b) the boy (that) John thinks called Mary |

Drel boy raises from the subject of embedded verb call out to the matrix CP. Since it passes through the edge of the embedded CP, there is no violation of the PIC. Drel will check the uRel feature on Crel at the matrix CP. However, in our theory, the uT feature on Crel cannot be checked by Drel, leaving it to be checked either by movement of the matrix subject to C, as in Figure 9, without the higher that, or by T-to-C, pronounced as the higher that, as in Figure 10. In the case of the embedded (non-relative) C, viz., Ce, the lower that is predicted to be obligatory because Drel from Drel boy cannot check Ce’s uT feature as it passes through the edge of the embedded CP. One of the authors of this article finds (16)b, which lacks that in the embedded clause, to be ill-formed. The other author finds (16)b perfectly acceptable (both authors are native speakers of English). This suggests for those who find (16)b fine, Drel can check the uT feature of an embedded non-relative C, and for other speakers, Drel can never check a uT feature.

Derivation of the boy John thinks that called Mary.

Derivation of the boy that John thinks that called Mary.

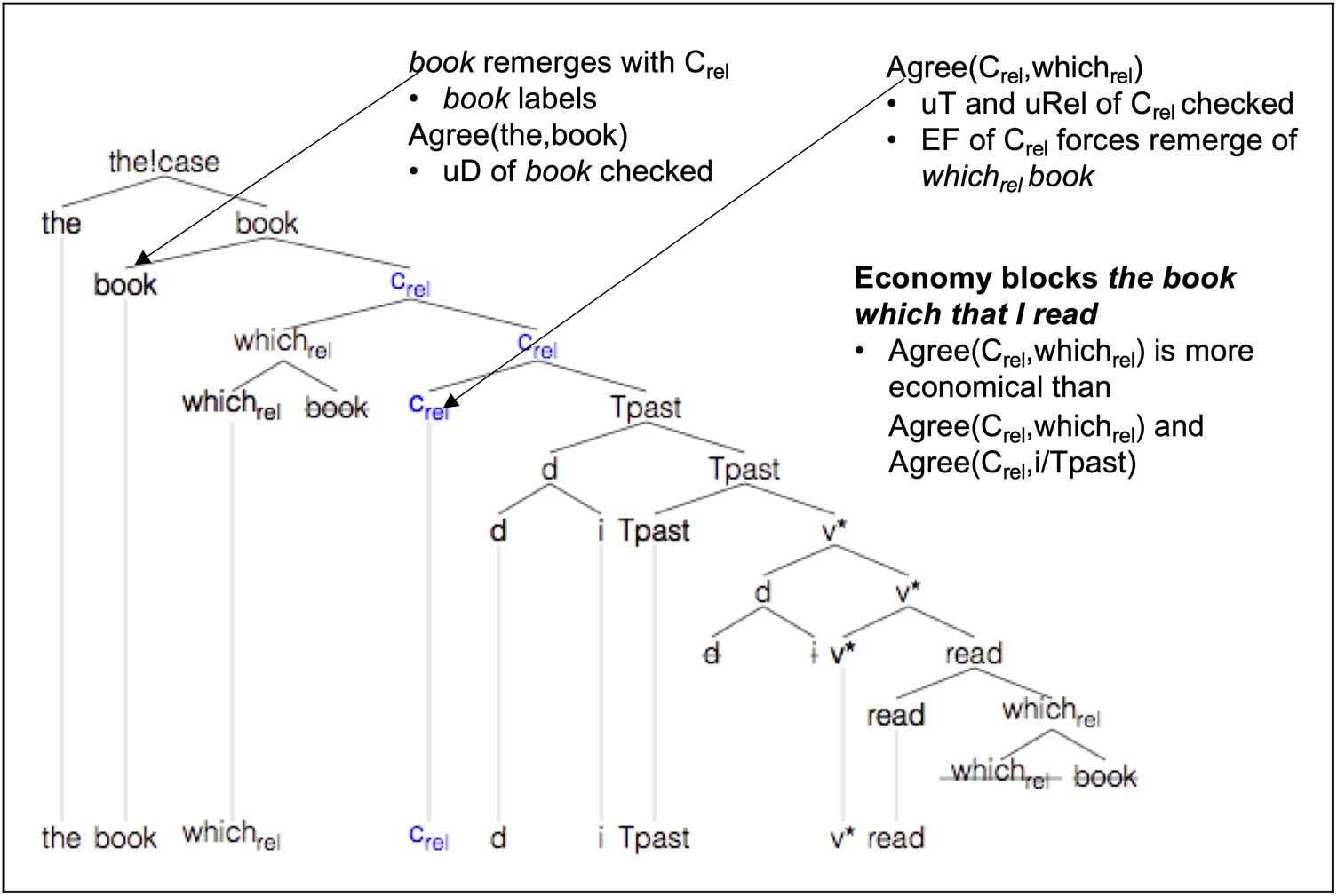

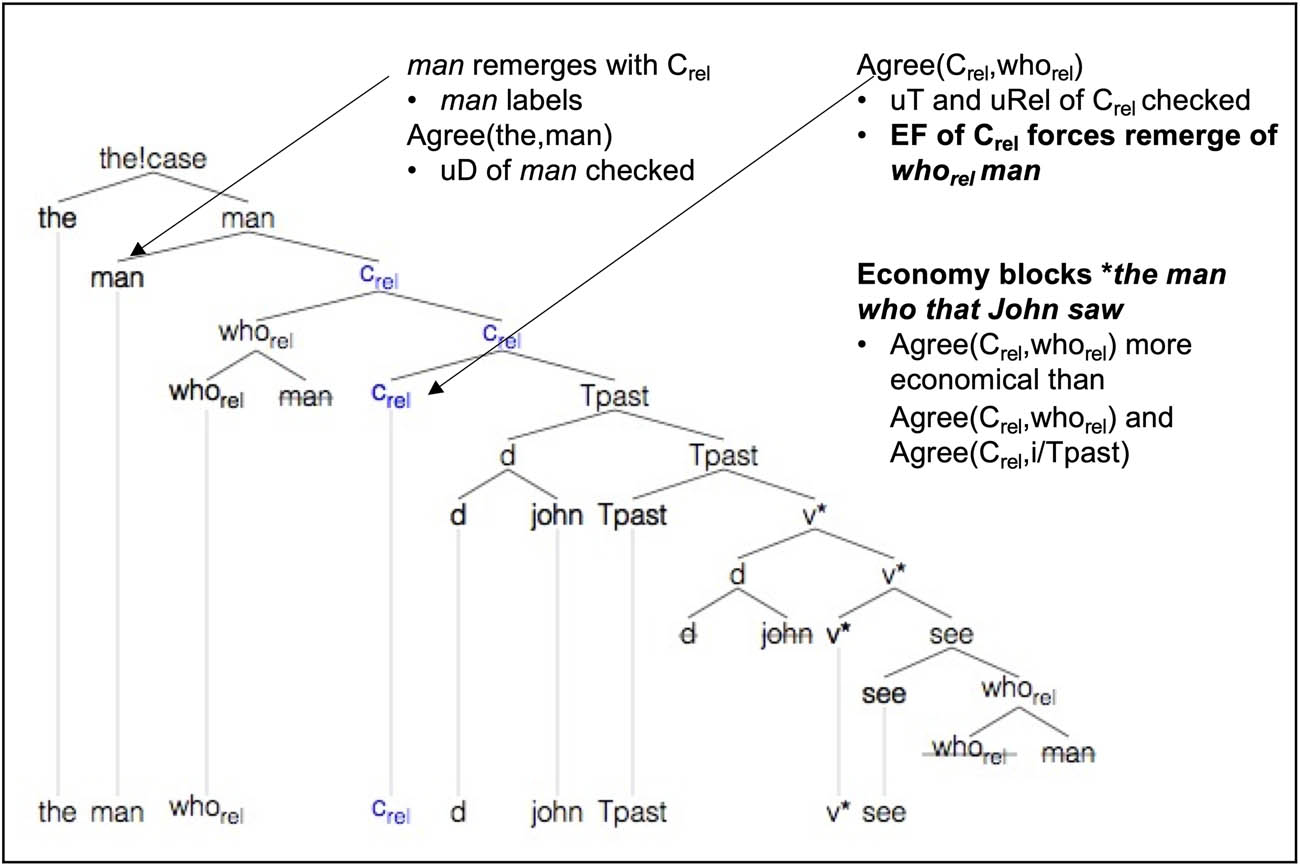

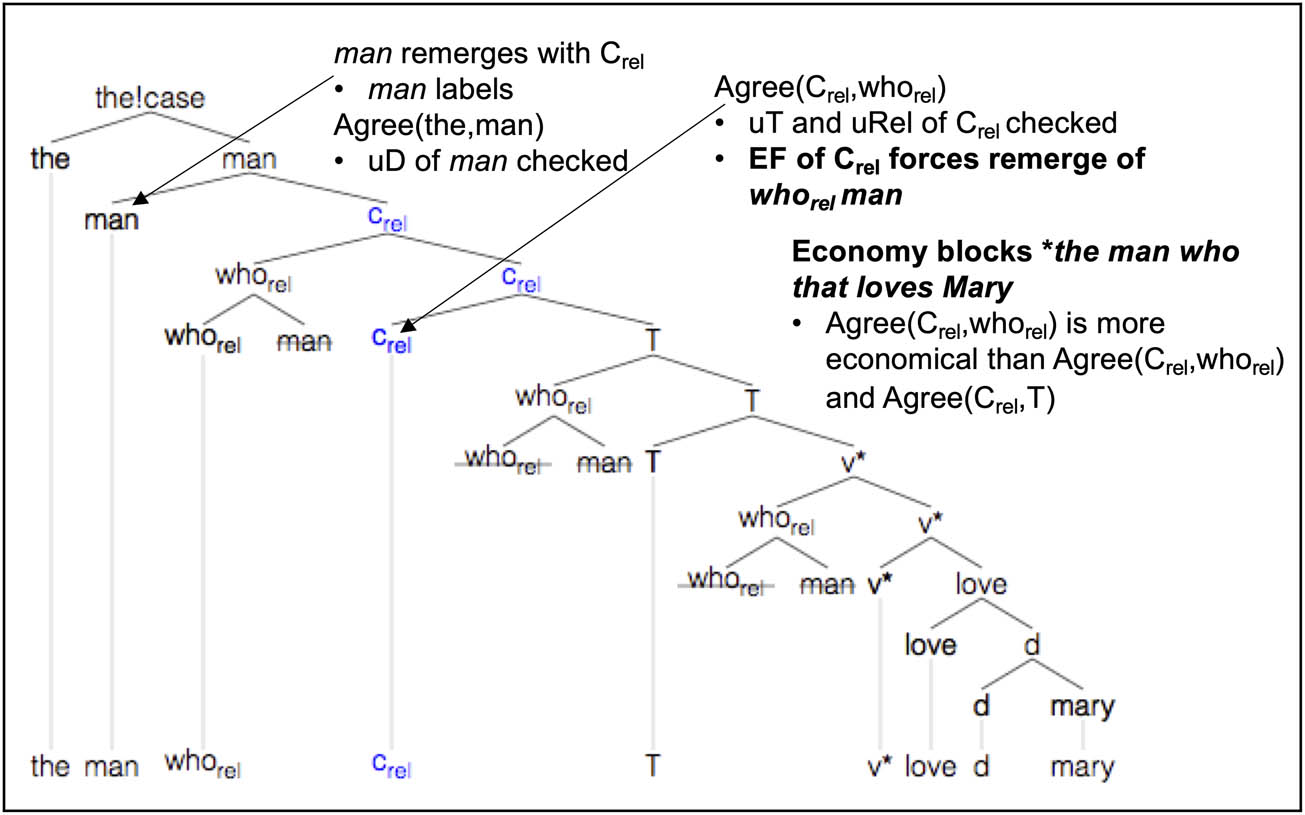

We next consider why a wh-relativizer (e.g., which and who) cannot co-occur with that in an object relative clause (17)a–d, nor in a subject relative clause (17)e–f.

| (17) | a) the book which I read |

| b) *the book which that I read (Gallego 2006, 151) | |

| c) The man who John saw | |

| d) *the man who that John saw (Gallego 2006, 154) | |

| e) the man who loves Mary | |

| f) *the man who that loves Mary (Gallego 2006, 151) |

Our proposal is that which rel and who rel are relative Ds that may value uT on Crel.[38] Economy then forces uT on Crel to always be checked by a relative wh-determiner when present. This is summarized in Table 3, which states that it is more economical for a single goal to value multiple uFs on a probe than it is for multiple goals to value the uFs. Basically, the fewer Agree operations required, the better.[39]

Economy

| Economy (of feature checking) |

Given a head X[uF1,.,uFn], n > 1, all uFi (1 ≤ i ≤ n) probe for a matching goal. Suppose distinct goals G1,…,Gm (m ≤ n) suffice to value F1 through Fn. A derivation with mmin, the fewest number of goals required, blocks all derivations with m > mmin goals39 |

In the derivation of (17)a shown in Figure 11, a single Agree relation between Crel and which rel results in simultaneous valuation of both uT and uRel on Crel. Economy blocks the option in which uRel and uT are separately checked (by which rel (or who rel ) and nominative Case on the subject, respectively). Hence, (17)b, which would require checking of uT on Crel by T, is blocked. Similarly, the derivation of (17)c, shown in Figure 12, results from a single Agree relation between Crel and who rel, and likewise, (17)d is blocked by economy.

Derivation of the book which I read.

Derivation of the man who(m) John saw.

Next, consider the case of who rel in subject relative clauses as shown in (17)e-f. Again, a single Agree relation between Crel and who rel licenses (17)e, as depicted in Figure 13, and (17)f is blocked by economy.

Derivation of the man who loves Mary.

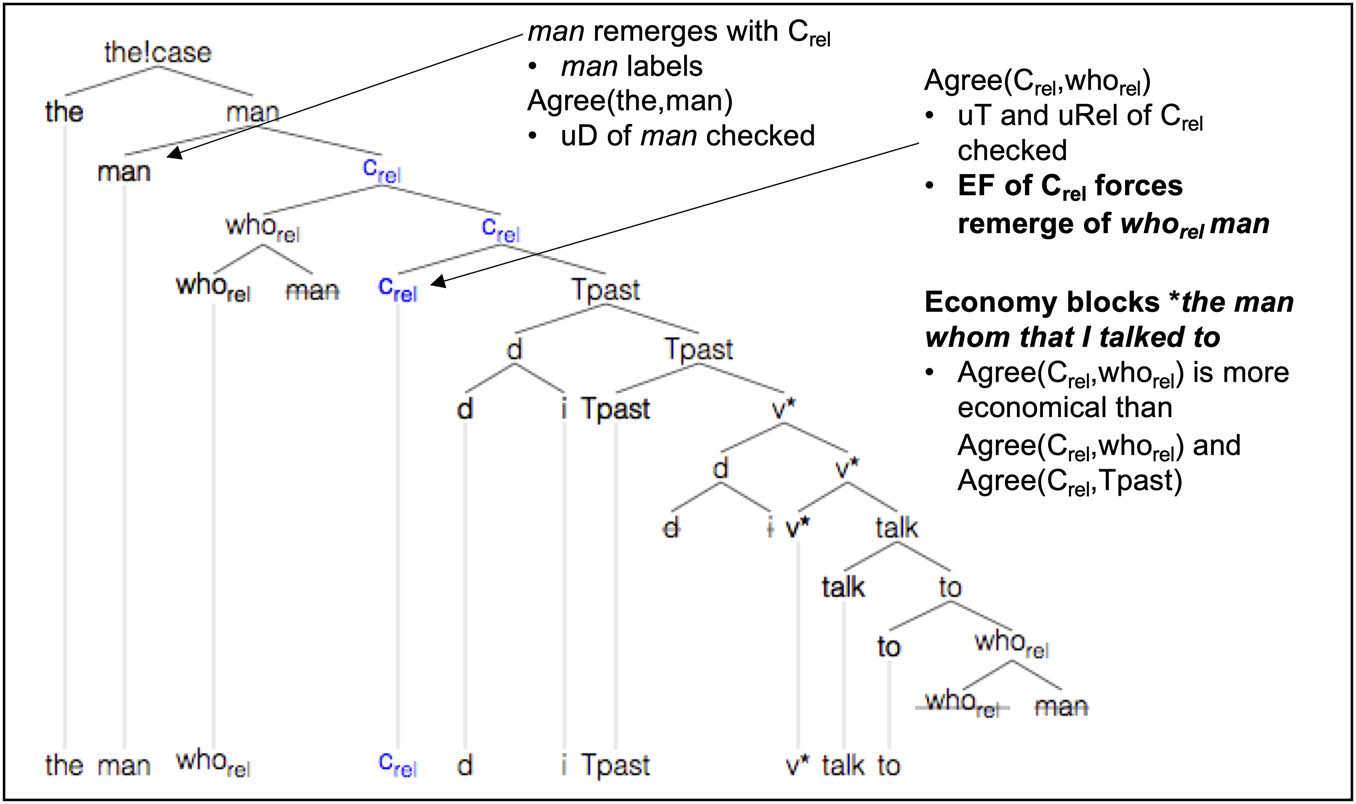

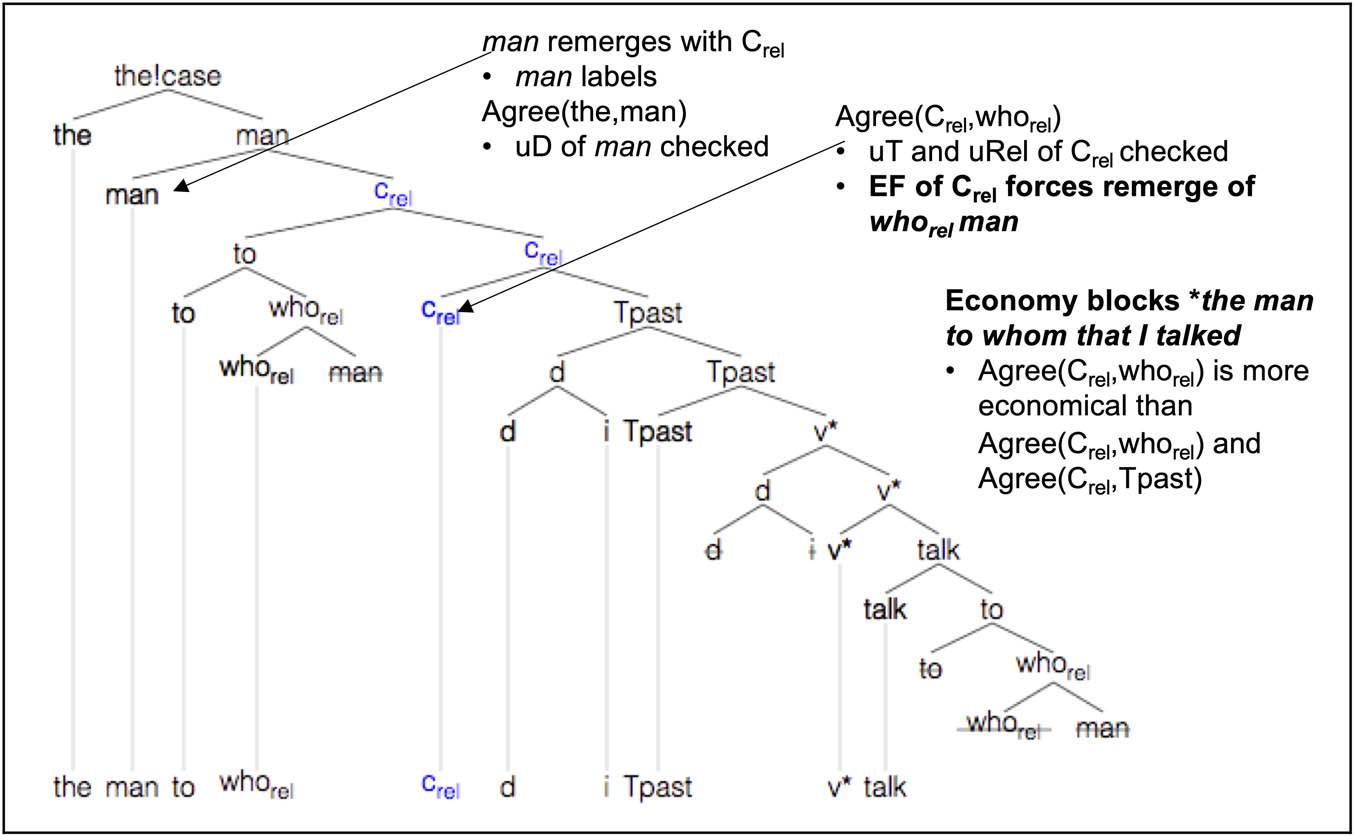

Related constructions with pied-piping can also be accounted for. Notably, pied-piping of P is optional as shown in (18)a–b, which contain whom rel , the object equivalent of who rel . To account for this, we assume that Crel may Agree with a relative DP contained within a PP, and the EF on Crel can attract either the relative DP itself or the containing PP. Pied-piping obtains in the latter case.[40]

| (18) | a) the man whom I talked to (Gallego 2006, 152) |

| b) the man to whom I talked | |

| c) *the man whom that I talked to | |

| d) *the man to whom that I talked |

The derivation of (18)a is given in Figure 14. Note we assume who rel may also be pronounced as whom at Spell-Out. For some speakers, the form of who rel can be sensitive to Case. For example, whom = who + Accusative. Crel agrees with the relative DP headed by who rel., and uT and uRel on Crel are simultaneously valued. Economy blocks the option of T separately checking uT on Crel, and (18)c is ruled out. The EF of Crel attracts the relative DP to the edge of CP, leaving to stranded. Example (18)b is analyzed in Figure 15. This is identical to Figure 14 except that the entire containing PP is raised to the edge of CP. Similarly, (18)d with that is ruled out by economy.

Derivation of the man who(m) I talked to.

Derivation of the man to who(m) I talked.

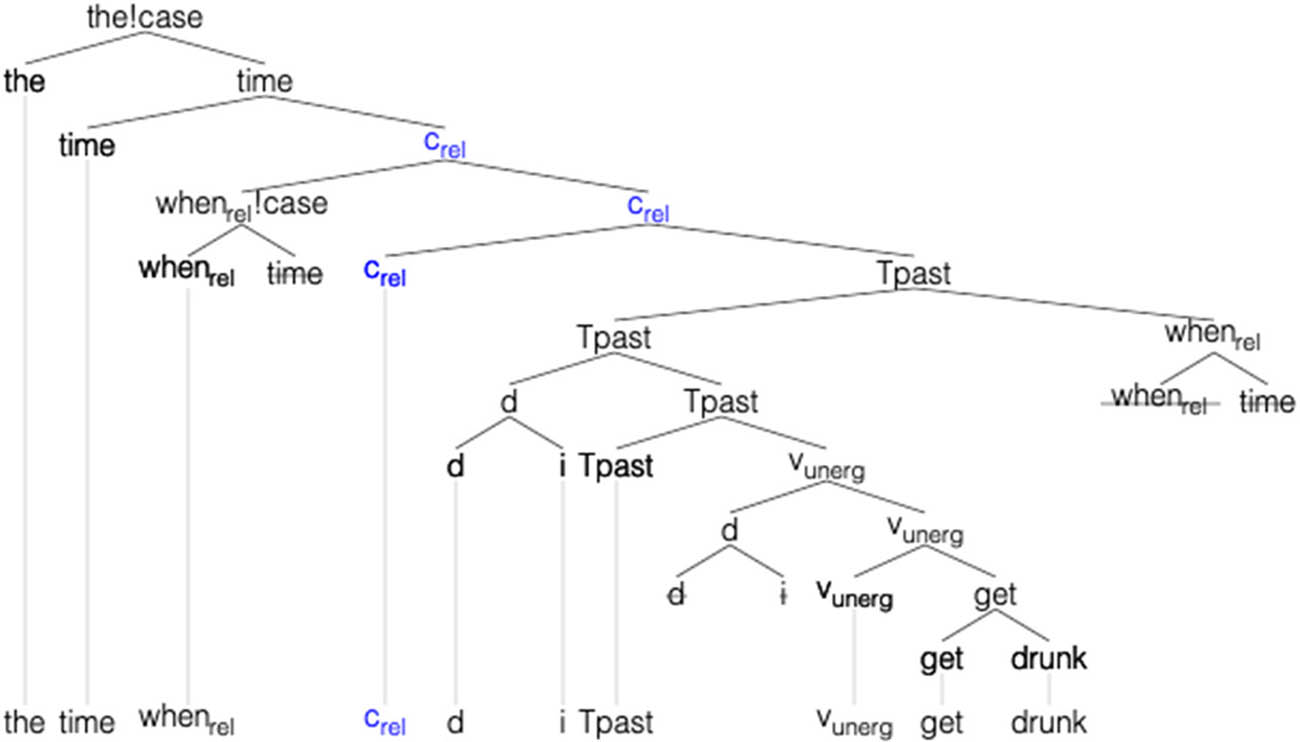

Wh-adverbials such as when can also be relativized, as in (19)a–b, from an anonymous reviewer. Note that when and where are adverbials, not determiners. We must extend the rel feature to wh-adverbials, i.e., when rel and where rel exist in the Lexicon. This raises a possible acquisition question as not all determiners have a relative counterpart.[41]

| (19) | a) the time when I got drunk |

| b) *the time when that I got drunk |

As when rel has an iRel feature and can check uT on Crel, our model straightforwardly accounts for (19)a, as shown in Figure 16. We assume that when rel time initially adjoins at the TP level (as it is a temporal modifier).[42] Furthermore, we assume that when rel checks both uT and uRel simultaneously on Crel, so economy blocks (19)b with that. Finally, the relative wh-adverbial when rel cannot value the uD of time (as is the case with all relative Ds); hence, time raises and its uD is valued via Merge with external the.[43] [44]

Derivation of the time when I got drunk.

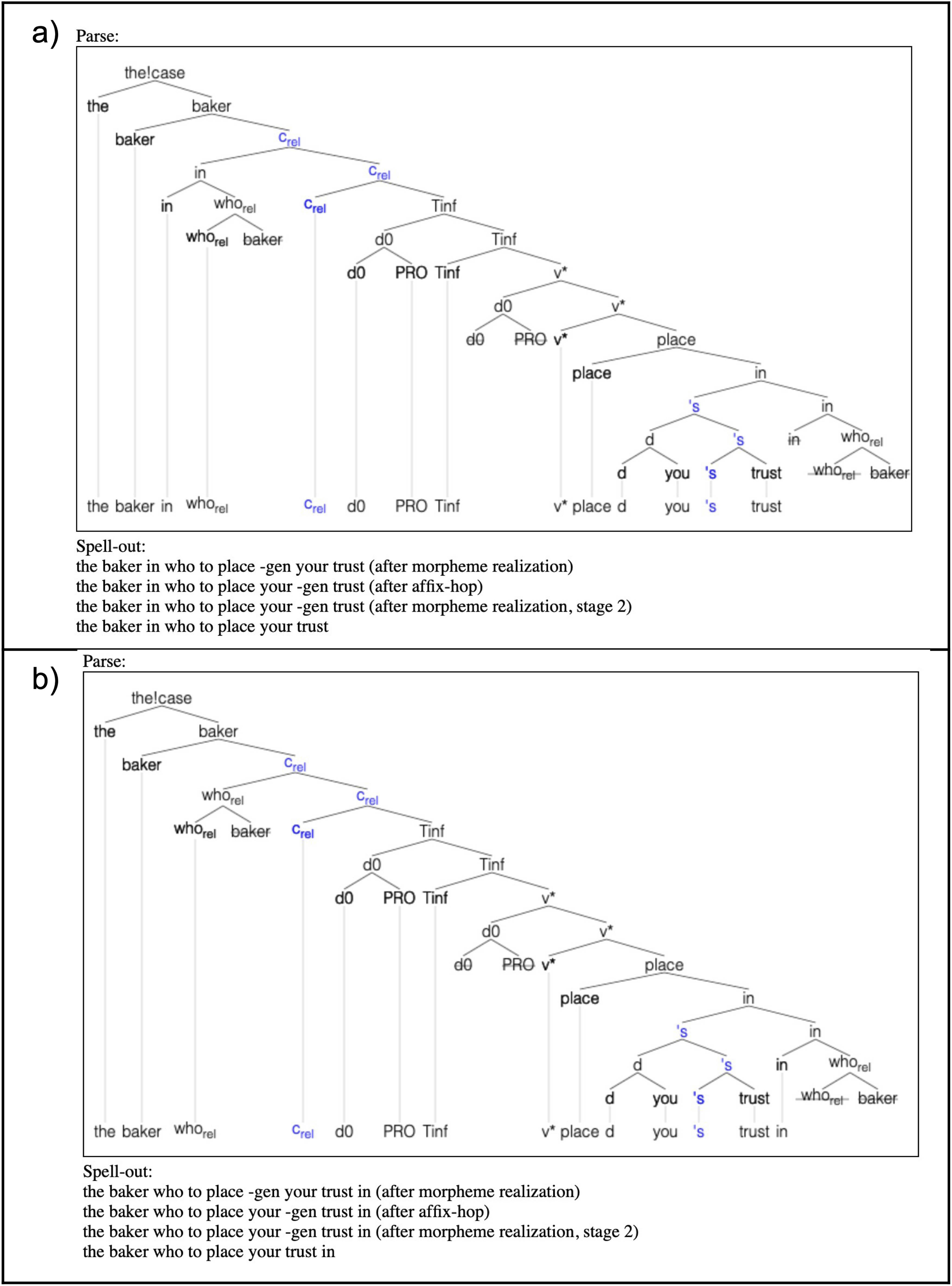

Relatives can also occur in non-finite clauses, as in (20)a–b.[45] Note that Sag (1997) indicates (20)b as being ill-formed; however, we find it grammatical. Pied-piping seems subject to dialectal variation.[46]

| (20) | a) the baker in whom to place your trust (Sag 1997, 461) |

| b) the baker whom to place your trust in (Sag 1997, 461 – marked as * by Sag) |

Relevant structures for (20)a–b are given in Figure 17. Note that we employ a non-finite T (Tinf) and a null subject (PRO). We assume a dyadic in that takes complement and specifier arguments.

Derivation of the baker in who to place your trust/the baker who to place your trust in.

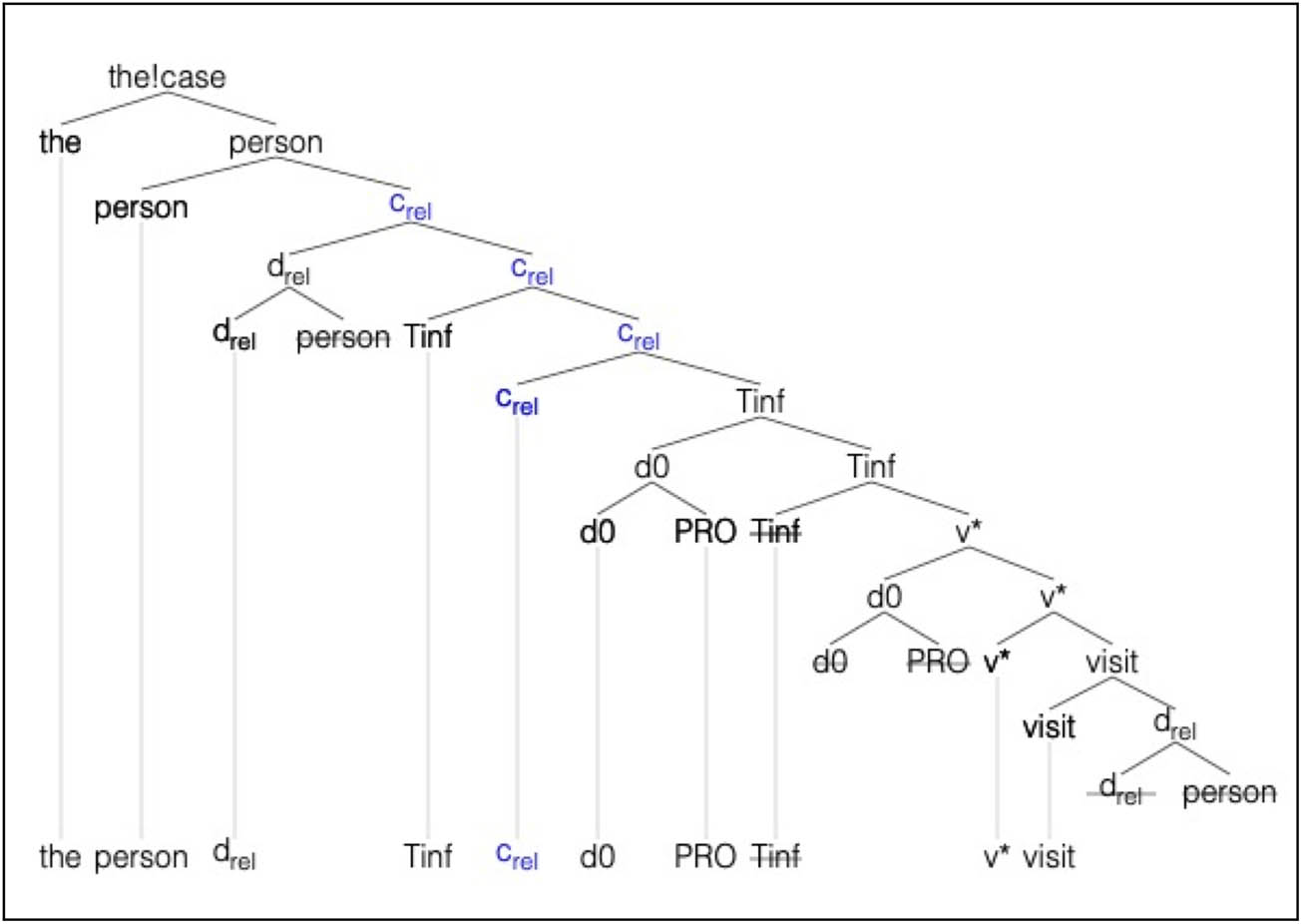

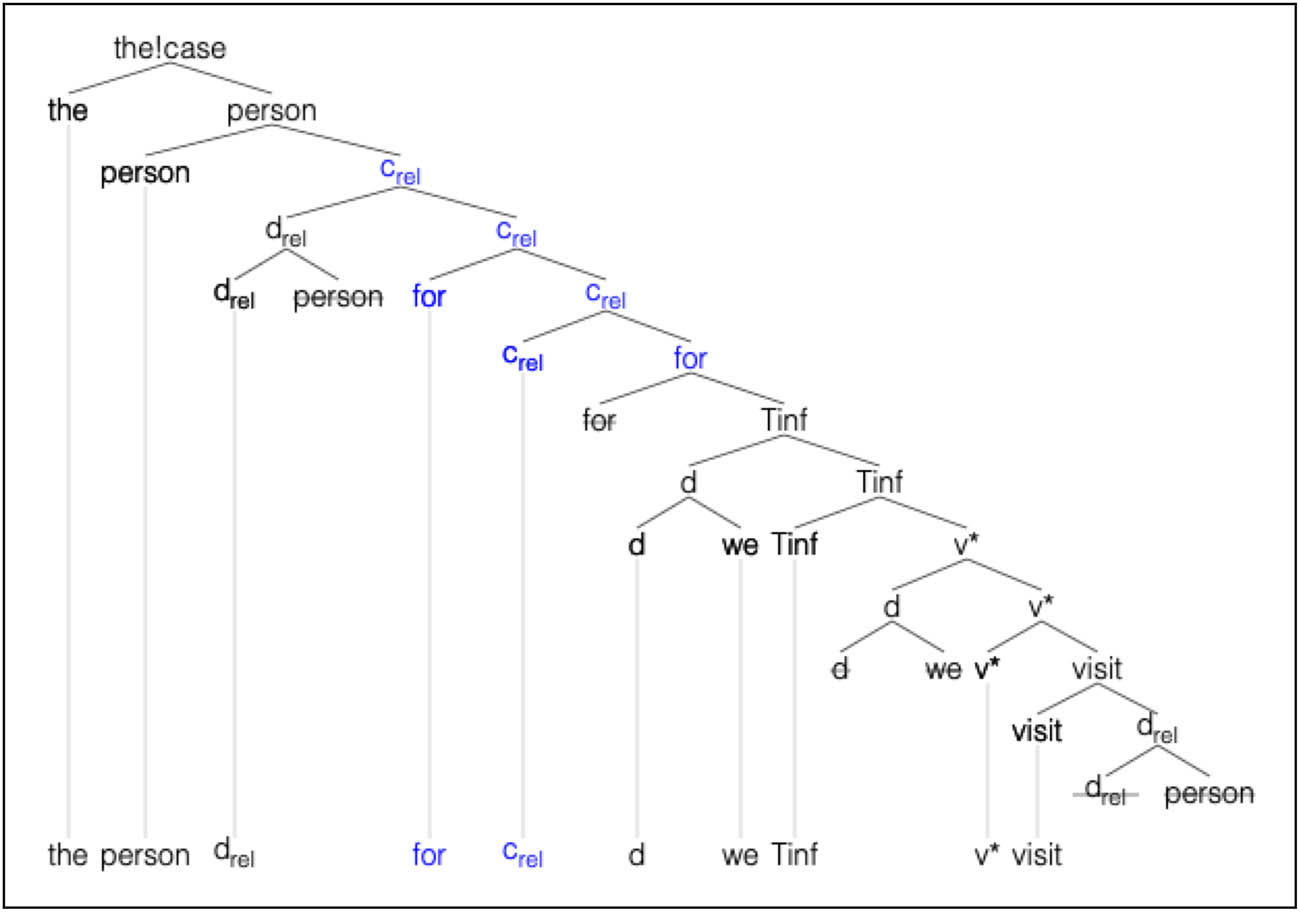

Another type of non-finite relative clause can occur with an optional for as in (21)a–b.

| (21) | a) the person to visit |

| b) the person for us to visit (Sag 1997, 464) |

Assume that Tinf (as with tensed T) and for are both capable of checking the uT feature on Crel. For (21)a, as shown in Figure 18, Tinf raises and checks the uT on Crel. The noun person raises and relabels the clause as a nominal. For (21)b, as shown in Figure 19, we assume that the complementizer for raises and checks the uT feature on Crel. Since for is closer to Crel than Tinf, Tinf does not raise given minimal search. The relative DP raises to the edge of CP, and then, person raises to relabel.

Derivation of the person to visit.

Derivation of the person for us to visit.

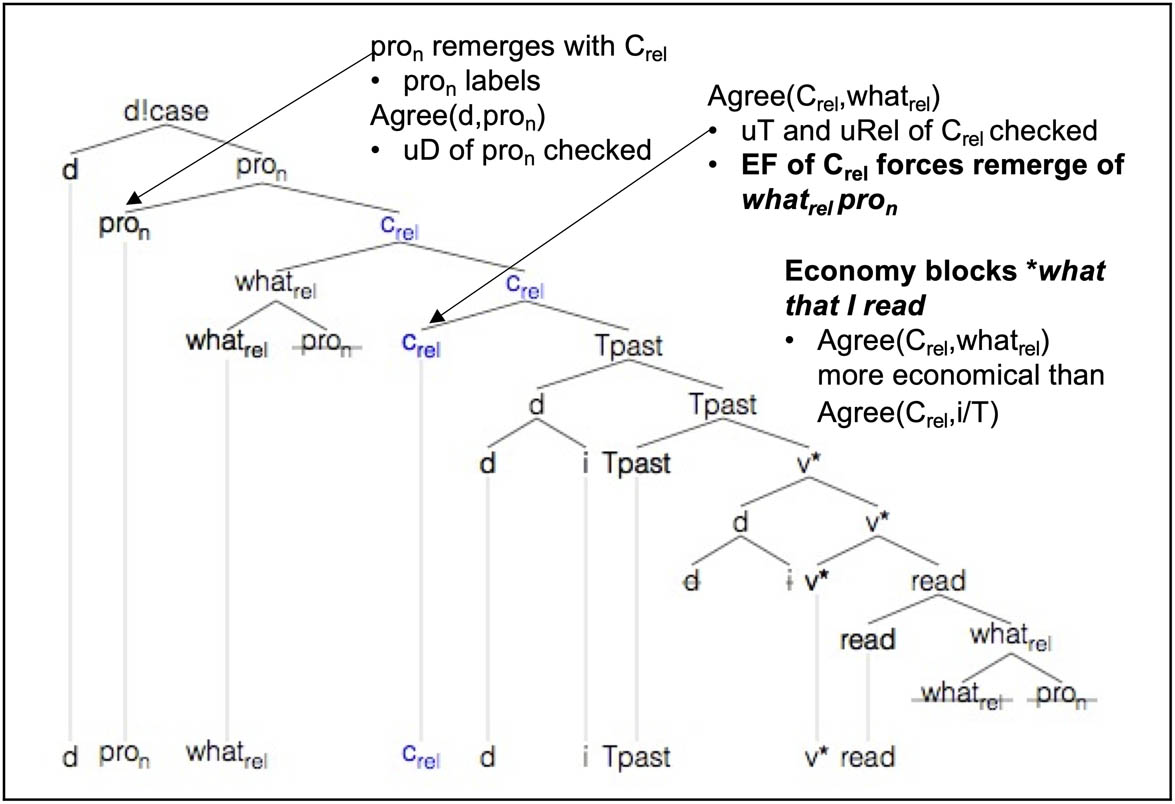

Our analysis also extends to the case of headless relatives, examples shown in (22)a–b. Headless relatives appear not to support that for Crel.

| (22) | a) what I read |

| b) *what that I read |

Assume that headless relatives contain pron, a form of pro occurring in relative clauses. We can co-opt our uRel and uT on Crel analysis by assuming that pron also has a uD feature, just as with the overt Ns so far.[47]

Figure 20 illustrates the derivation of (22)a. Suppose a relative determiner what rel, like who rel and which rel previously, agrees with Crel. In particular, permit what rel to simultaneously value uT and uRel on Crel. By economy, the option of checking uT on Crel separately via T is blocked, and (22)b is ruled out. Note that we permit pron to undergo movement before Merging with an external null D. (We do not need to stipulate a difference between covert and overt relative N with respect to movement.) This null D values uD on pron, cf. null Drel, which cannot value uD. Finally, we must also assume that pron is limited in distribution to co-occur with relative determiners only, as *the what I read is ill-formed.

Derivation of what I read.

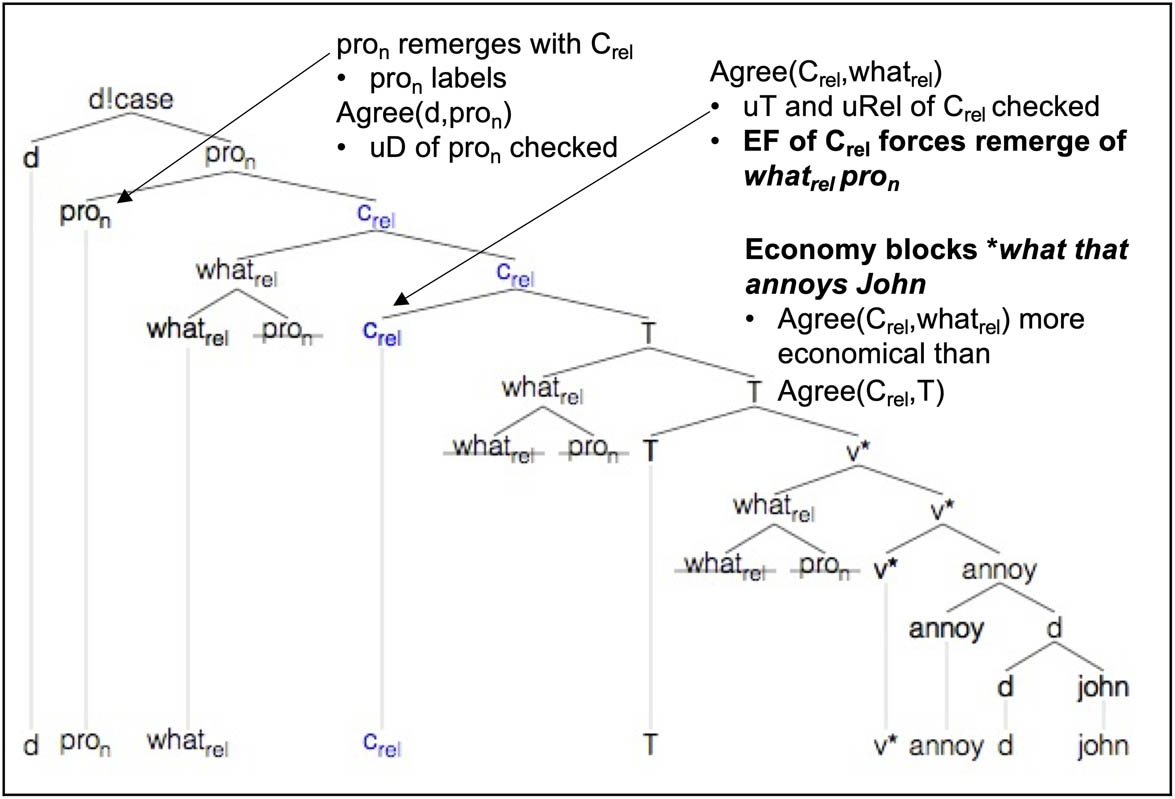

We next turn to subject headless relative clauses, accounted for in parallel fashion.

| (23) | a) what annoys John |

| b) *what that annoys John |

This is similar to the case of (22)a–b, except that the relative DP originates in the subject position here. The derivation of (23)a is shown in Figure 21.

Derivation of what annoys John.

We have developed an analysis of the distribution of who/whom/which/what and a null Drel in English. The relative determiner who occurs with human nouns, with the object variant whom occasionally used in some varieties of English.[48] Relative D which can be used with non-human NPs. A reviewer notes nothing in our syntactic analysis blocks *the man which arrived. We assume semantic feature matching for determiner-noun combinations is also involved, e.g., -human for which and +human for who. We assume that the appropriate relative pronoun is selected from the lexicon, so which rel occurs with a non-human relative noun and who rel occurs with a human relative noun. (But see also Note 3.) Otherwise, these relative Ds are identical. We have also seen that what can be used with a null NP complement.

4 Comparative and genitive relatives

Hale (2003) implemented a Minimalist Grammar that covers a variety of relative clauses from Keenan and Hawkins (1987) involving subject and object relatives, passivization, comparatives, and genitives. Although Hale covers a wide range of relative clause constructions, the reasons for the uses of the relative determiners which, who, what, and for restrictions on their use with that are not accounted for. Our model also accounts for all of the relative clause examples from Keenan and Hawkins (1987, 63), notably genitive relatives, as well as other related constructions.

The examples in (24) from Keenan and Hawkins (1987, 63) are essentially identical to examples that we have discussed earlier (Hale models (24)a, b, c, and a version of d).[49] (24)a is a subject relative (Figure 8), (24)b–c are object relatives (Figures 11 and 12). (24)d–e contain relative nouns that originate as the object of a preposition (as in Figures 14 and 15).[50] See the Appendix for complete derivations of these particular examples.[51]

| (24) | a) the boy who told the story – Subject relative |

| b) the letter which Dick wrote yesterday – Object relative | |

| c) the man who Ann gave the present to – Relative object of P | |

| d) the box which Pat brought the apples in – Relative object of P | |

| e) the dog which was taught by John – Passivized object relative (Keenan and Hawkins 1987, 63) |

We next discuss some examples from Keenan and Hawkins that require some revisions to our core model.[52]

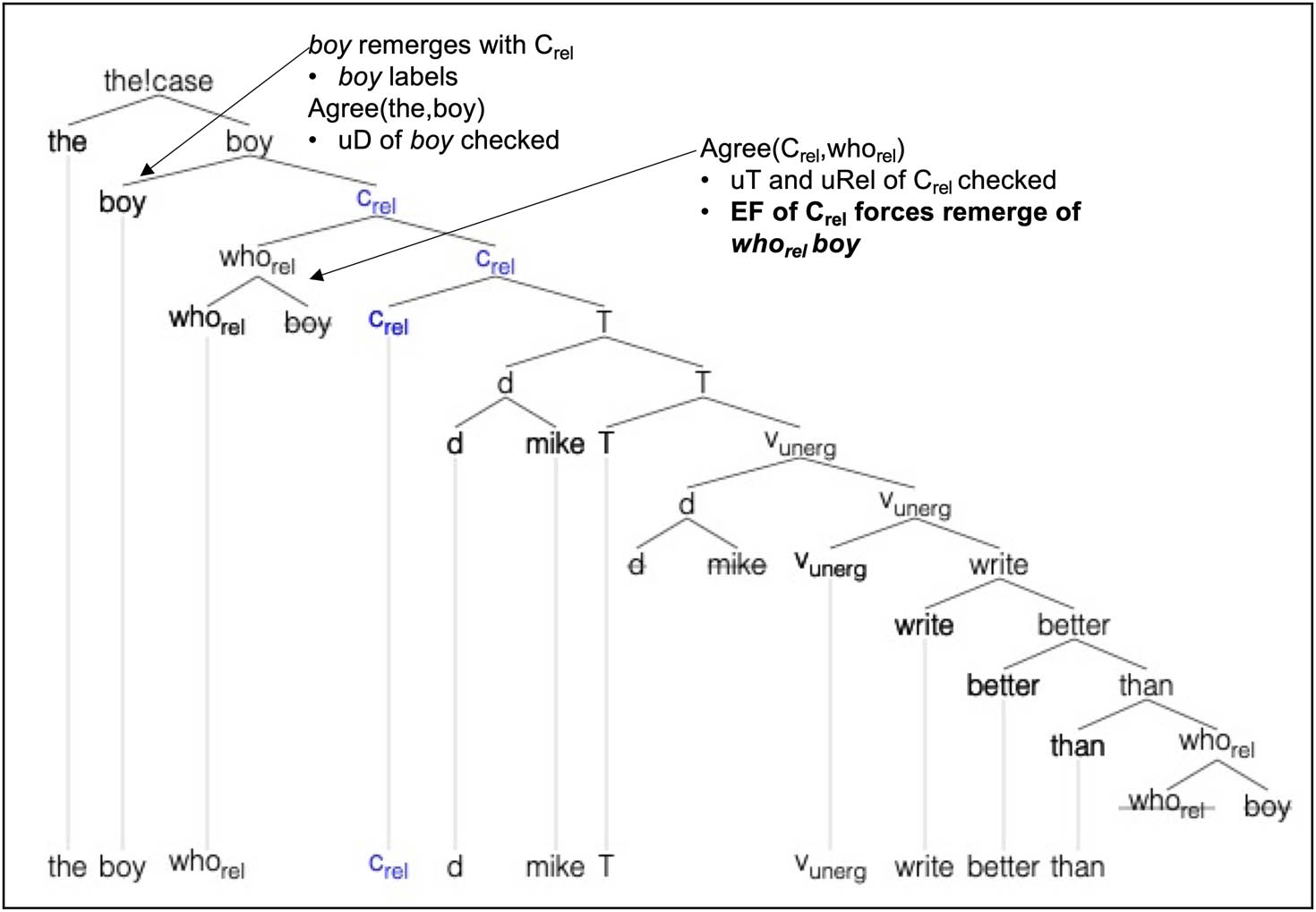

In example (25), boy originates from a relative DP object of the comparative than.[53]

| (25) | the boy who Mike writes better than (Keenan and Hawkins 1987, 63) – relative object of comparative than |

As shown in Figure 22, the relative who rel boy raises and remerges with Crel, checking uRel on Crel. The head boy with unvalued uD raises out of Crel P, then relabels and Merges with external the (which checks unvalued uD on boy).

Derivation of the boy who Mike writes better than.

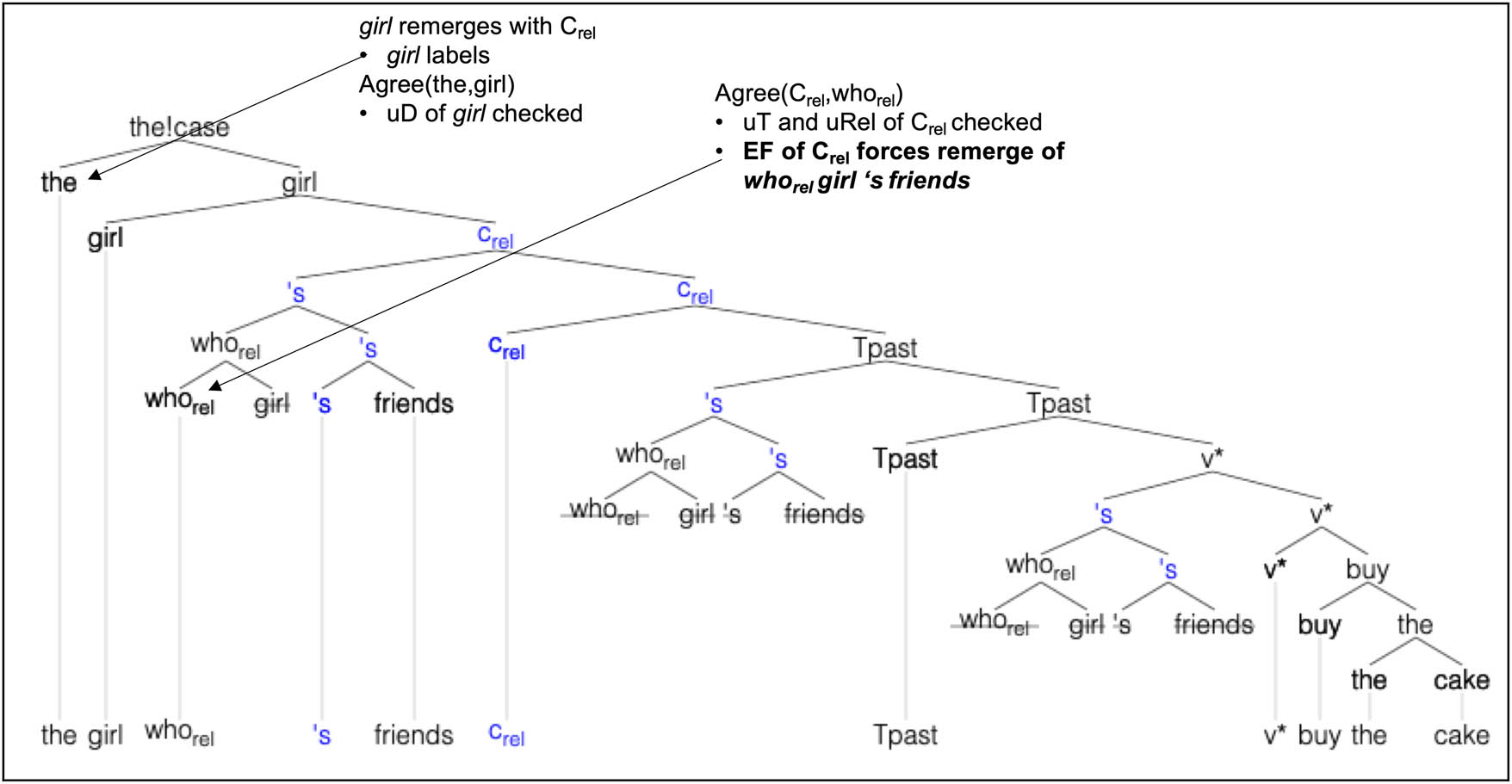

Next, we consider (26), from Keenan and Hawkins, which contains a genitive subject relative.

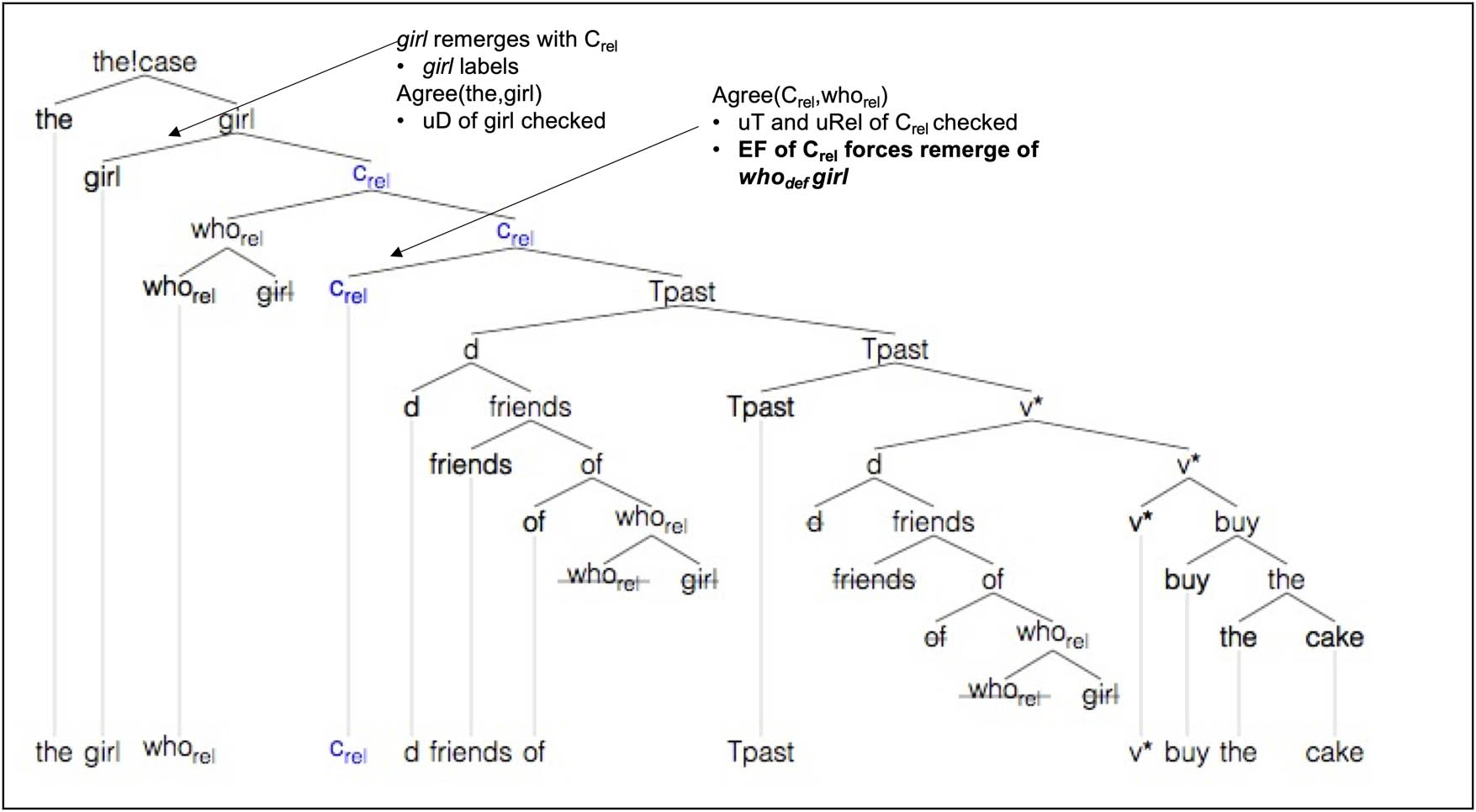

| (26) | the girl whose friends bought the cake – Genitive subject relative (Keenan and Hawkins 1987, 63) |

Figure 23 analyzes (26) as follows: the possessive subject DP who rel girl ‘s friend raises from the edge of v*P to the surface subject position at the edge of TP. This is followed by raising to the edge of CrelP (who rel checks uRel on Crel). The head girl raises and relabels the structure. We need to assume that although who rel is embedded in the specifier of the possessive DP, its Rel feature is visible to Crel and Agree (who rel , Crel) results in raising of the entire DP.[54]

Derivation of the girl whose friends bought the cake.

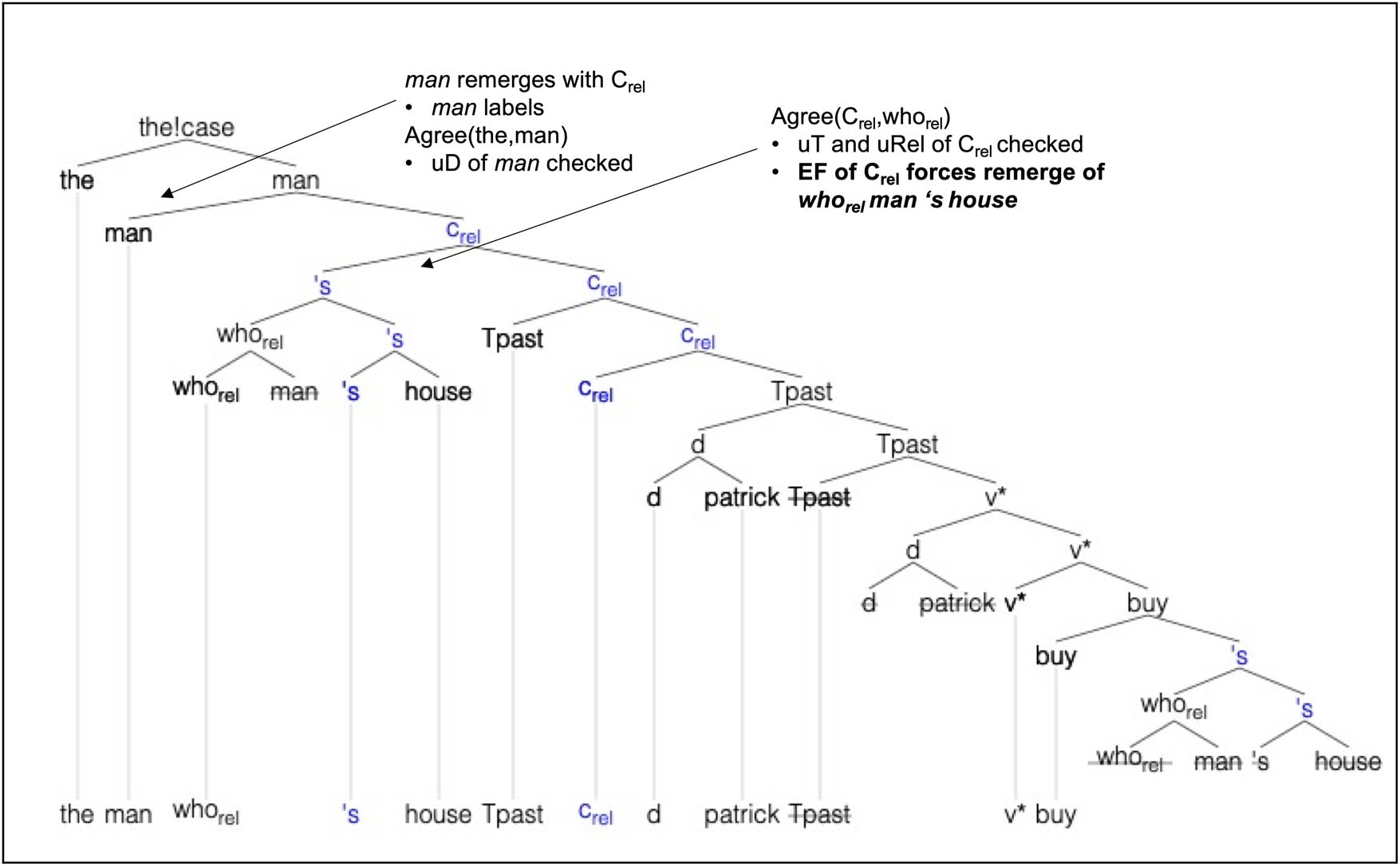

Example (27) is similar to (26) except that the genitive relative originates as an object. As shown in Figure 24, the genitive relative raises to the edge of Crel P, and the head man then further raises and relabels.[55]

| (27) | the man whose house Patrick bought – Genitive object relative (Keenan and Hawkins 1987, 63) |

Derivation of the man whose house Patrick bought.

Example (28) is similar to those shown previously in Figures 22 and 23 except that it is a passive construction (see the Appendix for the complete derivation).

| (28) | the boy whose brother was taught by Sandra – Genitive subject of passivized object relative (Keenan and Hawkins 1987, 63) |

Note that in addition to these examples from Keenan and Hawkins, our model is also able to generate related relative clause constructions with the relative contained within a PP complement headed by of. Examples (29)–(31)a correspond to the genitive relatives (26)–(28) except that the relative pronoun originates in a PP complement headed by of.[56]

| (29) | a) the girl who friends of bought the cake[57] |

| b) friend of who rel girl | |

| (30) | a) the man who Patrick bought the house of |

| b) house of who rel man | |

| (31) | a) the boy who the brother of was taught by Sandra |

| b) brother of who rel boy |

The structure of (29)a is shown in Figure 25. The relative DP who rel girl originates in a PP of-phrase that is the complement of friends, embedded within the subject. After the subject moves to the TP edge, the relative DP who rel girl moves to the Crel P edge to check the uRel feature, and head girl moves out and relabels. Example (30)a is similar except that it involves a relative object, and (31)a involves a passivized relative object.

Derivation of the girl who friends of bought the cake.

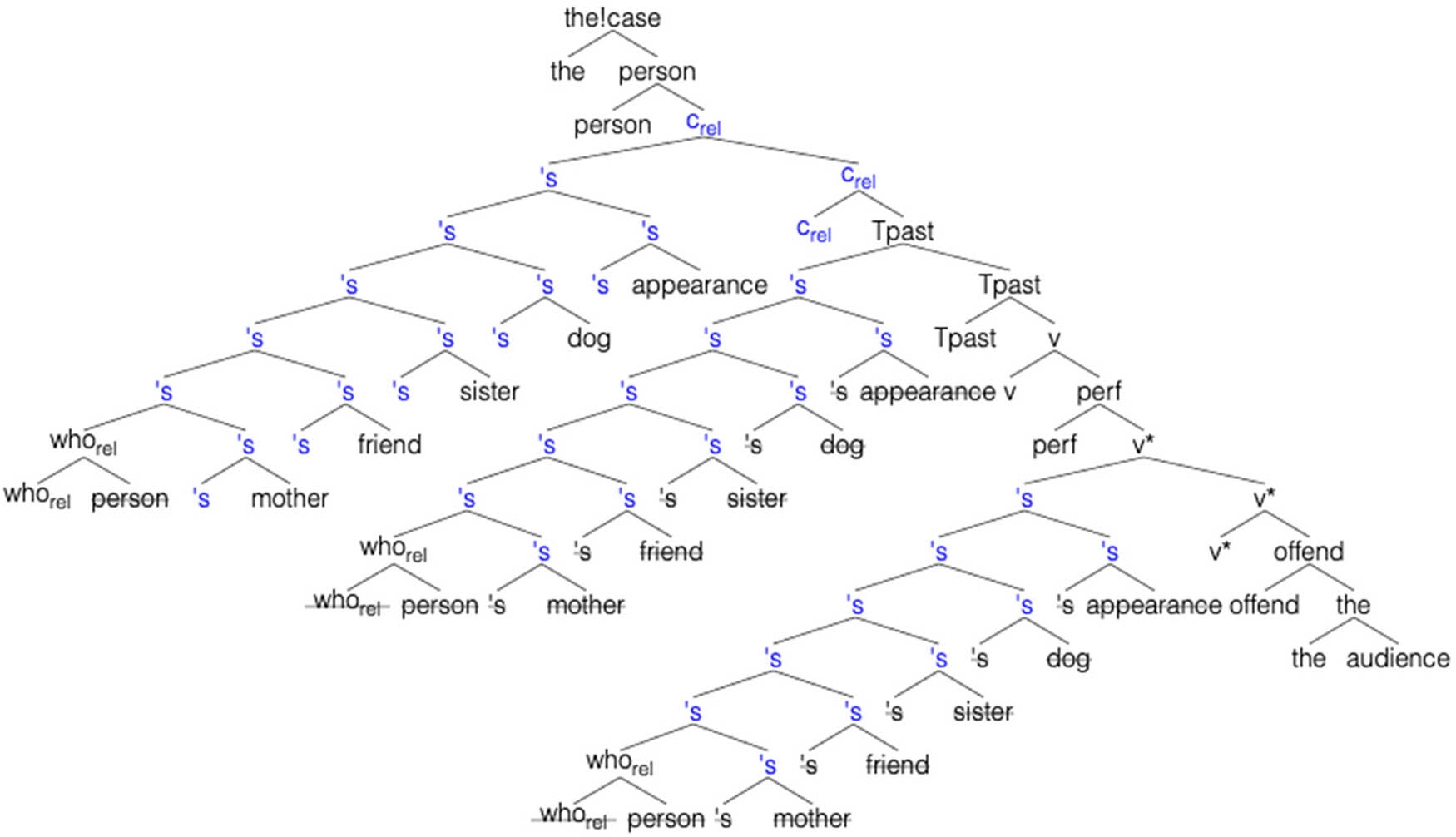

We next turn to deeply embedded genitive relatives, such as in (32).

| (32) | Give me the phone number of the person whose mother’s friend’s sister’s dog’s appearance had offended the audience. (Sag 1997, 450) |

The structure of the relative DP whose person ‘s mother’s friend’s sister’s dog’s appearance is shown in Figure 26. In our implementation, we must assume that the relative feature of deeply embedded who rel percolates up onto the highest ’s, so Crel is able to attract the entire DP to check its uRel feature.[58] See the Appendix for further examples of embedded relatives.

Embedded relative: the person whose mother’s friend’s sister’s dog’s appearance had offended the audience.

5 Other varieties of English

We have focused on an analysis that accounts for the structures of basic relative clauses in modern standard English. Although the relative clauses’ heads in (33)a–c are unavailable in standard modern English, they do occur in older stages of English and in some modern dialects.

| (33) | a) *which that |

| b) *who(m) that | |

| c) *Ø in a subject relative (e.g., *the boy called Mary) |

Old and Middle English allow a doubly filled CP. Examples (34)a–b are from Old English. Se is a demonstrative pronoun, although it is translated as a wh-pronoun (Ringe and Taylor 2014, 467).

| (34) | a) Se [weig se ðe læt to heofonrice] is for ði nearu & sticol |

| the way which C leads to heaven is therefore narrow and steep | |

| ‘the way which leads to heaven is therefore narrow and steep’ | |

| b) Hwæt is god butan Gode anum [se ϸe is healic godnisse] | |

| What is good except God alone who C is sublime goodness | |

| ‘what is good except God alone, who is sublime goodness’ (Ringe and Taylor 2014, 468–9) |

Examples of which that are also attested in Middle English, as shown in (35)a–b and (36).

| (35) | a) they freend which that thouh has lorn |

| ‘your friend that you have lost’ | |

| b) the conseil which that was yeven to yow by the men of lawe and the wise folk | |

| ‘the counsel that was given to you by the men of law and the wise folk’ (Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English - Kroch and Taylor 2000, per Santorini and Kroch 2007, Chapter 11) | |

| (36) | the est orisonte, which that is clepid commonly the ascendant |

| the eastern horizon which that is called commonly the ascendant | |

| ‘The eastern horizon, which is commonly called the ascendant’ (Van Gelderen 2014, 128, per Chaucer Astrolabe 660, 17–8) |

Zero subject relatives may also occur. Examples (37)a–c are cited by Bauer (1994).

| (37) | a) It was [the city gave us this job]. (Bauer 1994, 77, per Shannon 1978, 15) |

| b) Even if I found [somebody knew who I was], I won’t be them no more. (Bauer 1994, 77, per Wolfe 1977, 151) | |

| c) They used to arrest [people did that kind of thing]. (Bauer 1994, 77, per Higgens 1976, 78–79) |

Belfast English also has zero subject relatives, as in (38)a–b.

| (38) | a) There are [people don’t read the books]. |

| b) It’s always [me pays the gas bill]. (Henry 1995, 124) |

Finally, the following two examples are from Black English Vernacular/African American English.

| (39) | Ain’t [nobody know about no club] (Labov 1972, 188)[59] |

| (40) | The [man saw John] went to the store (Sistrunk 2012, 5) |

In our analysis so far, we have assumed the Lexicon contains who rel , which rel , when rel , and what rel , all of which are able to value uT on Crel. It is certainly plausible that this property could vary over individual lexical items. Thus, certain varieties of English which rel and who rel may lack this ability, thereby permitting uT on Crel to be checked separately by T or nominative Case on a subject, crucially licensing the pronunciation of that in the former case. Another point of variation concerns null Drel; we proposed earlier that null Drel, unlike overt Drel, is unable to value uT on Crel, but it appears that in some dialects null Drel may behave like overt Drel, permitting zero subject relatives, e.g., as in Belfast and African American English. To summarize, a relative D must contain a core Rel feature (by definition). However, the ability to value uT on Crel may vary diachronically and/or synchronically. To summarize, this minor change in lexical feature specification can account for the data described above and is not a problem for our computer implementation in principle.

6 Conclusion

We have built our theory and verified implementation based on the insights of Gallego’s (2006) analysis of relative clauses. Gallego, in turn, has built on the insights of P&T (2001). The fact that this refinement is possible is a sign that the MP is a viable research program. Our account makes use of a relative complementizer (Crel) with separate unvalued Rel (relative) and T (Tense) features. Rel is a construction-specific formal feature, distinguishing relatives from normal clauses. Rel and T together are subject to economic considerations, i.e., simultaneous valuation (where possible). Our verified analyses improve upon Gallego in the following ways: a) there is no need for an extra projection in the left periphery, b) there is no stipulation that a null D cannot move, c) there is no need for two types of C, one with an EPP feature, and one without, and d) we are able to account for the absence of which that in standard English. The additional stipulations of our model are that: i) a relative D cannot check a uD feature on N, in order to trigger extraction of the relative noun for relabeling, and ii) the null Drel cannot generally check a uT feature, although other relative Ds, such as which rel /who rel /whom rel /what rel /when rel , can. A natural question arises: is our three-feature system, Rel, T and D, minimal, i.e., parameter-efficient? As, in our theory, movement is driven, both EF and something akin to our unvalued D are required to initiate raising and relabeling of the relative clause into a nominal. Finally, a minimum of two features, such as Rel and T, are needed in order to exploit economy. Economy simplifies operational complexity, enabling multiple features to be valued in one operation. More broadly, in the MP framework, the functional category T selects for verbal phrase structure and further projects phrase structure (with a surface subject position).[60] In Chomsky (2008), non-selectional properties of T, e.g., phi-features, the ability to value nominative Case and Tense, do not appear in T’s lexical entry, but instead are transmitted from phase head C.

Overall, we have developed a detailed and logically consistent feature-driven theory of English relative clauses in the MP framework. We have also built a computer-implemented derivational system capable of converging on the correct analyses starting from an initial LA queue. The implementation confirms that our theory is both complete and detailed enough to constitute an (automatic) computer program. The interested reader is referred to the Appendix, which contains step-by-step computer-generated derivations, too detailed to be included in the main body of the article. The Appendix includes all the English relative clause examples discussed in the article (and others). The program is able to correctly select the precise Merge operation at each step (without human intervention), based on the state of the current SO and the first available item in the LA.[61] Moreover, our implementation permits us to verify that the model does not generate spurious analyses – unpredicted by the theory – for all example sentences.

We summarize the core relative D facts in Table 4.

Summary of relative Ds in English

| Relative D | Features | Explanation | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Drel | Rel | Drel unable to value uT | (14) the man that/Ø I talked to |

| uT on Crel must be checked by T if relative DP is a subject | (15)a the boy that called Mary | |||

| (15)b *the boy called Mary | ||||

| (b) | whichrel | Rel, T | whichrel/whorel/whomrel/whatrel/whenrel can value uT. By economy, uRel and uT on Crel must be simultaneously checked by one of the above whrel’s |

(17)a the book which I read |

| whorel | Note: that is banned | (17)c the man who John saw | ||

| whomrel | (17)e the man who loves Mary | |||

| whatrel | (19)a the time when I got drunk | |||

| whenrel | (22)a what I read | |||

| (23)a what annoys John | ||||

| (17)b *the book which that I read | ||||

| (17)d *the man who that John saw | ||||

| (17)f *the man who that loves Mary | ||||

| (19)b *the time when that I got drunk | ||||

| (22)b *what that I read | ||||

| (23)b *what that annoys John | ||||

Finally, we believe our analysis can be extended to account for data in other dialects and languages, assuming limited variation in determiner heads with respect to the ability to value uT on Crel. There are also a variety of other relative clause types that remain for future work.[62]

Abbreviations

- C

-

complementizer

- COMP

-

complementizer

- cP

-

(extra) complementizer phrase (above the normal CP)

- CP

-

complementizer phrase

- CQ

-

interrogative (Question) complementizer

- Crel

-

relative C

- CrelP

-

relative CP

- D

-

determiner

- DP

-

determiner phrase

- Drel

-

relative determiner

- EA

-

external argument

- ECM

-

exceptional case marking

- EF

-

edge feature

- EM

-

external merge

- EPP

-

extended projection principle

- H

-

head

- HPSG

-

head-drive phrase structure grammar

- IM

-

internal merge

- iPhi

-

interpretable phi-features (person, number, gender)

- LA

-

lexical array

- MG

-

minimalist grammar

- MP

-

minimalist program

- N

-

noun

- NP

-

noun phrase

- Op

-

operator

- phi-features

-

person, number, and gender features

- POSS

-

possessive head ’s

- PP

-

prepositional phrase

- pro

-

a pronoun that is not pronounced which is associated with Case positions.

- PRO

-

a pronoun that is not pronounced which is associated with non-Case positions

- pron

-

a nominal pro

- Q

-

question

- rel

-

relative feature

- SO

-

syntactic object

- T

-

tense, a feature and a functional head

- TP

-

tense phrase

- TPast

-

past tense

- uF

-

unvalued/uninterpretable feature

- uPhi

-

unvalued/uninterpretable phi-features (person, number, gender)

- uRel

-

unvalued relative feature

- iRel

-

interpretable relative feature

- uT

-

unvalued/uninterpretable T

- v

-

verb

- V

-

verb

- v*

-

transitive verbal head

- VP

-

verb phrase

- YP

-

a phrase with the head Y

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments. We would also like to thank Hiroshi Terada for technical assistance with this project. All errors are our own.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant- in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) #20K00664.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All of the derivations generated by our computer models are available in the Appendices. The two authors have built separate computational models that generate all of the derivations in this paper. The SWI-Prolog/Javascript implementation is freely available at https://sandiway.arizona.edu/mpp/mm.html for Windows, macOS and Linux. Instructions and all source code are supplied. The Python implementation is also available from the Appendices.

Appendix

The online Appendices are available at: https://sandiway.arizona.edu/mpp/appendix/.

References

Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. PhD thesis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Suche in Google Scholar

Andor, Daniel, Chris Alberti, David Weiss, Aliaksei Severyn, Alessandro Presta, Kuzman Ganchev, Slav Petrov, and Michael Collins. 2016. “Globally normalized transition-based neural networks.” In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, p. 2442–52. Berlin, Germany.10.18653/v1/P16-1231Suche in Google Scholar

Aoun, Joseph and Yen-hui Audrey Li. 2003. Essays on the representations and derivational nature of grammar: The diversity of wh-constructions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/2832.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Bauer, Laurie. 1994. Watching English change: An introduction to the study of linguistic change in standard Englishes in the 20th century. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Valentina. 1999. Consequences of antisymmetry: Headed relative clauses. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110803372Suche in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Valentina. 2000. “The raising analysis of relative clauses: A reply to Borsley.” Linguistic Inquiry 31, 123–40.10.1162/002438900554316Suche in Google Scholar

Black, Alan W. 1986. “Formal properties of Feature Grammars.” Unpublished manuscript, typescript.Suche in Google Scholar

Borsley, Robert D. 1997. “Relative clauses and the theory of phrase structure.” Linguistic Inquiry 28, 629–47.Suche in Google Scholar

Brame, Michael. 1968. “A new analysis of relative clauses: Evidence for an interpretive theory.” Unpublished manuscript, 1968, typescript.Suche in Google Scholar

Bruening, Benjamin, Dinh Xuyen, and Lan Kim. 2018. “Selection, idioms, and the structure of nominal phrases with and without classifiers.” Glossa: A journal of General Linguistics 3(42), 1–46. 10.5334/gjgl.288.Suche in Google Scholar

Bruening, Benjamin. 2020. “The head of the nominal is N, not D: N-to-D movement, hybrid agreement, and conventionalzed expressions.” Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5(15), 1–19. 10.5334/gjgl.1031.Suche in Google Scholar

Carlson, Greg. 1977. “Amount relatives.” Language 53, 520–42. 10.2307/413175.Suche in Google Scholar

Cecchetto, Carlo and Caterina Donati. 2015. (Re)labeling. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262028721.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1977. “On wh movement.” In Formal syntax, edited by Peter W. Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrain Akmajian, p. 71–132. New York: Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and binding: The Pisa Lectures. Dordrecht: Foris.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. “Minimalist inquiries: The framework.” In Step by step, edited by Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, p. 89–155. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. “Derivation by phase.” In Ken Hale: A life in language, edited by Michael Kenstowicz, p. 1–52. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4056.003.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. “Beyond explanatory adequacy.” In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, Volume 3, edited by Adriana Belletti, p. 104–132. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195171976.003.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. “On phases.” In Foundational issues in linguistic theory; essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, edited by Robert Freidin, Carlos Otero, and Maria-Luisa Zubizaretta, p. 133–66. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/7713.003.0009Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2011. “Language and other cognitive systems. What is special about language?” Language Learning and Development 7, 263–78. 10.1080/15475441.2011.584041.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2013. “Problems of Projection.” Lingua 130, 33–49. 10.1016/j.lingua.2012.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2015. “Problems of projections: Extensions.” In Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti, edited by Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann Elisa, and Simona Matteini, p. 1–16. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2021. “Minimalism: Where are we now, and where can we hope to go.” Gengo Kenkyu 160, 1–41.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam and Howard Lasnik. 1995. “The theory of principles and parameters.” In The Minimalist Program, 13–127. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam and Howard Lasnik. 1977. Filters and Control. Linguistic Inquiry 8, 425–504.Suche in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara. 2001. “Deletion under identity in relative clauses.” In Proceedings of NELS 31, 131–45.Suche in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris and Edward Stabler. 2016. “A formalization of Minimalist syntax.” Syntax 19, 43–78. 10.1111/synt.12117.Suche in Google Scholar

Culicover, Peter W. 2013. Grammar and complexity: Language at the intersection of computation and performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Deal, Amy Rose. 2009. “The origin and content of expletives: Evidence from “selection”.” Syntax 12, 285–323. 10.1111/j.1467-9612.2009.00127.x.Suche in Google Scholar

de Vries, Mark. 2002. “The syntax of relativization.” PhD thesis. Amsterdam, Netherlands: University of Amsterdam.Suche in Google Scholar

Epstein, Samuel David, Hisatsugu Kitahara, and T. Daniel Seely. 2014. “Labeling by Minimal Search: Implications for successive cyclic A-Movement and the conception of the postulate “phase”.” Linguistic Inquiry 45, 463–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43695654.10.1162/LING_a_00163Suche in Google Scholar

Fong, Sandiway and Jason Ginsburg. 2012. “Computation with doubling constituents: Pronouns and antecedents in phase theory.” In Towards a biolinguistics understanding of grammar: Essays on interfaces, edited by Anna Maria Di Sciullo, p. 303–338. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.194.14fonSuche in Google Scholar

Gallego, Angel. 2006. “T-to-C movement in relative clauses.” In Romance languages and linguistic theory 2004: Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’, Leiden, 9-11 December 2004, edited by Jenny Doetjes and Paz Gonzalez, p. 143–70. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.278.08galSuche in Google Scholar

Hale, John T. 2001. “A probabilistic Early parser as a psycholinguistic model.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Meeting of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Language Technologies, p. 1–8. Association for Computational Linguistics. 10.3115/1073336.1073357.Suche in Google Scholar

Hale, John T. 2003. “Grammar, uncertainty and sentence processing.” PhD thesis. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University.Suche in Google Scholar

Hankamer, Jorge. 1973. “Why there are two than’s in English.” In Papers from the 9th regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society edited by C. Corum, T. C. Smith-Stark, and A. Weister, p. 179–91. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.Suche in Google Scholar

Harkema, Hendrik. 2001. “Parsing minimalist languages.” PhD thesis. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles.Suche in Google Scholar

Haumann, Dagmar. 2007. Adverb licensing and clause structure in English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.105Suche in Google Scholar

Henry, Alison. 1995. Belfast English and standard English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195082913.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Higgens, George V. 1976. The judgement of Deke Hunter. London: Secker and Warburg.Suche in Google Scholar

Indurkya, Sagar. 2021. “Solving for syntax.” PhD thesis. Cambridge, MA: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, Mark. 1988. Attribute-vale logic and the theory of grammar. Stanford, CA: CSLI Lecture Notes.Suche in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Keenan, Edward L. and Sarah Hawkins. 1987. The psychological validity of the Accessibility Hierarchy.” In Universal Grammar: 15 Essays, edited by Edward L. Keenan, 60–85. London. Croom Helm.Suche in Google Scholar

Kroch, Anthony and Ann Taylor. 2000. Penn-Helsinki parsed corpus of Middle English Second Edition. http://www.ling.upenn.edu/histcorpora/PPCME2-RELEASE-3/.Suche in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1972. Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English Vernacular. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Larson, Richard K. 1985. “Bare-NP adverbs.” Linguistic Inquiry 16, 595–621.Suche in Google Scholar

Marantz, Alec. 1997. “No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon.” In University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 4(2), 201–25.Suche in Google Scholar

Müller, Gereon. 2011. Constraints on displacement: A phase-based approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/lfab.7Suche in Google Scholar

Müller, Stefan. 2015. “The CoreGram project: theoretical linguistics, theory development, and verification.” Journal of Language Modeling 3, 21–86.10.15398/jlm.v3i1.91Suche in Google Scholar

Nivre, J, 2003. “An efficient algorithm for projective dependency parsing.” In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Parsing Technology, p. 149–160. Nancy, France.Suche in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David and Esther Torrego. 2001. “T-to-C movement: Causes and consequences.” In Ken Hale: A life in language, edited by Michael Kenstowicz, p. 355–426. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4056.003.0014Suche in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David and Esther Torrego. 2007. “The syntax of valuation and the interpretability of features.” In Phrasal and clausal architecture: Syntactic derivation and interpretation. In honor of Josephy E. Emonds, edited by Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian, and Wendy Wilkins, p. 262–294. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.101.14pesSuche in Google Scholar

Radford, Andrew. 1997. Syntax: A minimalist introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139166898Suche in Google Scholar

Radford, Andrew. 2016. Analysing English sentences, second edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511980312Suche in Google Scholar

Radford, Andrew. 2019. Relative clauses: Structure and variation in everyday English. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108687744Suche in Google Scholar

Ringe, Don and Ann Taylor. 2014. The development of Old English: A linguistic history of English, volume II. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sag, Ivan A. 1997. “English relative clause constructions.” Journal of Linguistics 33, 431–83. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4176423.10.1017/S002222679700652XSuche in Google Scholar

Salzmann, Martin. 2017. Reconstruction and resumption in indirect A’-dependencies: On the prolepsis and relativization in (Swiss) German and beyond. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9781614512202Suche in Google Scholar

Santorini, Beatrice and Anthony Kroch. 2007. “The syntax of natural language: An online introduction using the Trees program.” Unpublished manuscript, 2007. http://www.ling.upenn.edu/∼beatrice/syntax-textbook.Suche in Google Scholar

Schachter, Paul. 1973. “Focus and relativization.” Language 49, 19–46.10.2307/412101Suche in Google Scholar

Shannon, Dell. 1978. Cold trail. London: Gollancz.10.18356/9c095f28-enSuche in Google Scholar

Sistrunk, Walter. 2012. The syntax of zero in African American relative clauses. PhD thesis. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.Suche in Google Scholar

Sobin, Nicholas. 2014. “Th/Ex, agreement, and case in expletive sentences.” Syntax 17, 385–416.10.1111/synt.12021Suche in Google Scholar

Stabler, Edward P. 1997. “Derivational Minimalism.” In Logical Aspects of Computational Linguistics, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 1328, edited by Christian Retoré, p. 68–95. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.10.1007/BFb0052152Suche in Google Scholar

Stabler, Edward P. 2011. “Computational perspectives on Minimalism.” In Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism, edited by Cedric Boeckx, p. 617–43. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199549368.013.0027Suche in Google Scholar

Torr, John, Milos Stanojević, Mark Steedman, and Shay B. Cohen. 2019. “Wide-coverage Neural A* parsing for Minimalist Grammars.” In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, p. 2486–505.10.18653/v1/P19-1238Suche in Google Scholar

van Gelderen, Elly. 2013. Clause structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139084628Suche in Google Scholar

van Gelderen, Elly. 2014. A history of the English language, revised edition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.183Suche in Google Scholar

Vergnaud, Jean-Roger. 1974. French relative clauses. PhD thesis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Suche in Google Scholar

Wolfe, Gene. 1977. “The eyeflash miracles.” In Best Science Fiction of the Year 6, edited by Terry Carr. London: Gollancz.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Interpreting unwillingness to speak L2 English by Japanese EFL learners

- Factors in sound change: A quantitative analysis of palatalization in Northern Mandarin

- Beliefs on translation speed among students. A case study

- Towards a unified representation of linguistic meaning

- Hedging with modal auxiliary verbs in scientific discourse and women’s language