Abstract

Gliomas are particularly challenging due to their high invasiveness, frequent recurrence, and elevated mortality rates. Despite the availability of treatments like surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, each of these methods faces significant limitations. This has led to a pressing demand for new strategies against gliomas. In this landscape, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown significant potential in recent years. However, the application of MSCs in glioma therapy encounters various challenges. A significant advancement in this field is the utilization of exosomes (Exo), key secretions of MSCs. These exosomes not only carry the benefits inherent in MSCs but also exhibit unique physicochemical properties that make them effective drug carriers. Consequently, MSCs Exo is gaining recognition as a sophisticated drug delivery system, specifically designed for glioma treatment. The scope of MSCs Exo goes beyond being just an innovative drug delivery mechanism; it also shows potential as a standalone therapeutic option. This article aims to provide a detailed summary of the essential role of MSCs Exo in glioma progression and its growing importance as a drug delivery carrier in the fight against this formidable disease.

Introduction

Gliomas, as the predominant primary brain tumors within the central nervous system, account for 80 % of all primary brain malignanciesm [1]. Among these, the World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) stands out as the most aggressive form, characterized by a median survival time of merely 15 months [2]. Despite advancements in surgical techniques, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, the prognosis for glioma patients remains grim [3]. These therapies face several limitations: the impossibility of completely excising the tumor surgically, the risk of radiation-induced damage to adjacent healthy brain tissue, and significant challenges such as the difficulty for chemotherapy drugs to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and the emergence of resistance to chemotherapy [4, 5]. In light of these constraints, the focus of research is shifting towards MSCs as an innovative therapeutic strategy to overcome the shortcomings in glioma treatment [4, 6]. A key attribute of MSCs is their natural tendency to home to tumor sites, a characteristic that could be exploited for targeted therapy [7]. Once localized at the tumor, MSCs exhibit anti-tumor activities by suppressing tumor cell growth and promoting apoptosis [6, 8, 9]. However, the interaction with the tumor microenvironment (TME) can influence MSCs to develop a pro-tumor phenotype, potentially exacerbating tumor progression [10, 11]. This dual nature of MSCs in the tumor context makes their role highly controversial. Furthermore, MSC-based treatments are not just about cell-to-cell contact but also involve the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs), notably exosomes. These exosomes play a crucial role in modulating the immune response and reshaping the microenvironment, fostering conditions favorable for tissue repair and potentially counteracting tumor growth [8, 12].

Exo represents small vesicles excreted by a multitude of cell types, containing proteins, RNA, DNA fragments, lipids, and metabolites, they can migrate to target cells through diverse mechanisms, modulating their functional responsiveness [13], [14], [15]. In recent years, exosomes have emerged as promising candidates for glioma treatment. These vesicles are particularly effective in directly delivering chemotherapeutic drugs, such as Doxorubicin (DOX) and Paclitaxel (PTX), to tumor sites [16], [17], [18]. This targeted delivery not only reduces chemoresistance but also minimizes the systemic side effects typically associated with such treatments. Further enhancing their therapeutic potential, engineered exosomes can be modified to express miRNA, mRNA, and siRNA, which are instrumental in inhibiting glioma cell proliferation, invasion, and migration [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. Gliomas, characterized by high vascularization, can also be targeted through the anti-angiogenic properties of exosomes [24, 25]. Overcoming drug resistance, a significant hurdle in effective glioma treatment is another area where engineered exosomes show promise. By enhancing the sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents, these exosomes can play a crucial role in treatment efficacy [26], [27], [28]. Additionally, the immunosuppressive microenvironment of gliomas contributes to their heterogeneity and treatment resistance. Here, exosomes can exert an immunomodulatory effect, reshaping this microenvironment and counteracting tumor invasion [29], [30], [31]. Despite their potential, one of the challenges with exosomes is their relatively low targeting ability. Recent research has focused on engineering modifications to improve their specificity towards glioma cells [26, 32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. Moreover, combining exosome-based therapies with other physical treatment methods, such as focused ultrasound and local magnetic positioning, shows promise in increasing their BBB penetration and accumulation within the brain, thereby enhancing therapeutic outcomes [34, 38, 39].

MSCs Exo display both tumor-promoting and suppressing functions [40, 41]. The outcomes of MSCs Exo’s actions might depend on their origin, constituents, and the tumor’s stage. Their potential as a drug delivery system is significant, especially when compared to conventional nanocarriers, as they can cross the BBB, are stable, and have reduced immunogenicity and toxicity [42], [43], [44]. However, the challenge of targeting precision remains. In summary, this article reviews the role of MSCs Exo in glioma progression and their potential as a drug delivery system. It highlights the advancements in using MSCs Exo for glioma treatment, offering insights into their application in this challenging field.

Mesenchymal stem cells and exosomes

Mesenchymal stem cells

MSCs are multipotent, non-hematopoietic progenitor cells found in tissues like adipose, bone marrow, dental pulp, umbilical cord, and placenta [45]. These cells can differentiate into various cell types, including osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [46]. Notably, MSCs can modulate tumor cell proliferation and immune responses [47], exerting either suppressive or promotive effects on tumor progression [10, 48]. They target multiple components in the TME, including immune cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts [49], as depicted in Figure 1. Additionally, MSCs can transform into tumor-associated MSCs (TA-MSCs), adopting a tumor-supportive phenotype that facilitates tumor growth [10, 11]. Despite their dual role in influencing tumor cells, the mechanisms underlying MSCs’ functional transformation and their homing to tumors remain areas of active research. Some studies suggest that MSCs are drawn to tumors by interactions between specific cytokines and chemokine receptors, such as SDF-1/CXCR 4, SCF-c-Kit, HGF/c-Met, VEGF/VEGFR, PDGF/PDGFR, and MCP-1/CCR 2 [50]. Their low immunogenicity and strong tumor tropism, coupled with ease of acquisition and rapid proliferation, make MSCs promising carriers for anti-tumor biotherapeutics, including cytokines, chemotherapeutic agents, and oncolytic viruses [51, 52].

Origin, differentiation, and effects of MSCs on the TME (the figure was drawn using AI and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license).

However, tissue-derived MSCs face challenges such as donor variability and limited scalability. An alternative source of MSCs is embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). However, ESCs pose significant immune rejection risks and ethical concerns, while iPSCs are plagued by genetic instability. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) can differentiate into MSCs, producing uniform mesenchymal tissues without teratoma formation and can further differentiate in vitro [53], [54], [55]. These hESC-derived MSCs (hES-MSCs) offer advantages in scalability and quality consistency and may have enhanced immunomodulatory functions compared to MSCs [56]. In tumor-bearing mice, the direct injection of hES-MSCs engineered with adenovirus and lentivirus vectors into xenografts or into the contralateral hemisphere can inhibit tumor growth and prolong survival time [57]. The differentiation of iPSCs into MSCs is currently a highly researched area. Utilizing a non-viral, non-integrating reprogramming platform to generate iPSCs results in more stable pluripotent cells, which can then differentiate more effectively. This method leads to the production of iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) that not only tackle the challenges of heterogeneity and scalability associated with traditional MSCs but also retain their significant therapeutic benefits [58, 59]. iMSCs have demonstrated effectiveness in inhibiting tumor proliferation and metastasis in various cancer models [60], [61], [62].

MSCs are derived from a variety of tissues, including adipose tissue, bone marrow, dental pulp, umbilical cord, and placenta. These cells exhibit the potential to differentiate into diverse cell types such as osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes. In the TME, MSCs interact with different cellular components including immune cells, endothelial cells, and tumor-associated fibroblasts. These interactions are crucial in modulating the proliferation and immune responses of tumor cells. MSCs play a dual role in tumor progression, where they can either suppress or promote tumor growth, depending on various factors in the TME.

Exosomes and their advantages as drug delivery vehicles

Exosomes, a major type of EVs, are secreted by all cell types and contribute to intercellular communication. These vesicles vary in size, biogenesis, and content, encapsulating a range of biomolecules such as signaling molecules, RNA, proteins, DNA fragments, carbohydrates, and lipids [63]. EVs are ubiquitous in bodily fluids including urine, blood, tears, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and breast milk [64], and play a critical role in regulating cell function, morphology, and outcomes through various signaling pathways upon reaching their target cells. According to the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV), EVs are classified into three subtypes: exosomes (30–150 nm), microvesicles (100–1,000 nm), and apoptotic bodies (1,000–6,000 nm), distinguished by their size and biogenesis [63]. Originating within multivesicular bodies (MVBs), exosomes are released into the extracellular matrix and can target both nearby and distant cells, significantly influencing cellular processes in both normal and pathological conditions [65], [66], [67].

Exogenous nanomaterials, commonly used as drug carriers, face challenges such as triggering autoimmune responses, causing thrombosis, generating cytotoxic effects, and low clearance rates in organs [68]. These issues limit their clinical application. In contrast, Exo offer advantages due to their endogenous nature, providing greater stability than synthetic polymers and liposomes. Exo exhibits properties conducive to immune surveillance, possesses an extended half-life, and shows potential in targeting receptor cells. Its ability to cross the BBB and carry diverse molecules like proteins, lipids, RNA, and DNA fragments is notable [69], [70], [71]. As such, Exo is emerging as a superior vehicle for the systemic delivery of targeted drugs. Encapsulation of anti-tumor drugs in exosomes enhances drug solubility, bioavailability, and stability, while reducing rapid drug clearance and unintended tissue deposition [72]. However, the efficiency of exosome targeting in GBM is limited, as intravenously administered Exo predominantly accumulates in the spleen and liver, with only a small fraction reaching the tumor site [73]. To overcome this, engineered Exo with tumor-targeting capabilities can be developed, enhancing their accumulation at tumor sites and marking a novel trend in translational medicine [74].

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes

MSCs, recognized as a pivotal source for clinical cell therapy, are widely considered the ideal carriers for anti-cancer biological agents. Despite their potential, utilizing MSCs as therapeutic carriers presents challenges, including unstable differentiation, potential vascular clotting, and infection risks. Exosomes, key secretions of MSCs, inherit many of their parent cells’ advantages [75]. These exosomes, thanks to their unique physicochemical properties, can surmount the limitations of MSCs in drug delivery applications. It is noteworthy that MSCs produce a higher quantity of exosomes compared to other cell types [76], and these exosomes demonstrate strong tumor-targeting capabilities [77, 78], reduced immunogenicity [79], and an enhanced ability to penetrate the BBB [80].

Encapsulation of chemotherapy drugs using MSCs Exo significantly enhances their ability to inhibit tumor proliferation and progression, while maintaining high biosafety. For instance, drugs delivered via MSCs exosomes are less likely to cause myocardial damage compared to free chemotherapeutic drugs [81]. MSCs have inherent tumor-tropic properties, which are believed to be due to their ability to home to tumor sites in response to inflammatory signals [82]. This characteristic is exploited to use MSC-derived exosomes as vehicles for drug delivery to tumor sites, including gliomas. The specificity of these exosomes in targeting tumor cells arises from multiple aspects: (1) surface proteins: exosomes express specific surface proteins that interact with receptors or molecules uniquely or overexpressed on tumor cells [83]; (2) microenvironmental factors: the tumor microenvironment, including hypoxia and inflammatory signals, may modulate exosome uptake by tumor cells [78, 84]; (3) genetic and molecular targeting: exosomes can be engineered to carry molecules like small siRNA, miRNA, circRNA, lncRNA, or specific drugs that target molecular pathways critical for tumor cell survival [85], [86], [87], [88], [89]. Additionally, further enhancing MSC-Exo’s tumor-targeting by jointly altering surface properties and contents through covalent modifications or genetic engineering shows their potential from basic research to clinical application [83, 90, 91].

The effects and underlying mechanisms of MSC-Exo on glioma progression

Tumor-promoting effects

Research has established that exosomes from MSCs can accelerate glioma progression (refer to Figure 2). Figueroa et al. identified a novel element in the glioma matrix, termed Glioma Associated-human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (GA-HMSCs). These cells, isolated from surgical specimens and used within five generations in experiments, secrete exosomes that carry miR-1587 to Glioma Stem Cells (GSCs), leading to a reduction in nuclear receptor corepressor 1 (NCOR1) expression. This interaction notably increases GSC proliferation, clonality, and tumorigenicity in both in vitro and in vivo environments, underscoring the vital role of GA-HMSCs in tumor support and the significance of tumor-stroma interactions in tumor development [92]. Extending this research, Qiu et al. generated Glioma Associated Mesenchymal Stem Cells (GA-MSCs) from bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) from both mice and humans. They discovered that exosomal miR-21 from GA-MSCs boosts CD73 expression in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). CD73, functioning as an ectonucleotidase, fosters an immunosuppressive environment via adenosine production. Moreover, subsequent investigations showed glioma-derived exosomal CD44 triggers the miR-21/SP1/DNMT1 feedback loop in MSCs. This increases miR-21 levels in MSCs exosomes, thereby amplifying the immunosuppressive effects of glioma exosomes. Interestingly, the study suggests that modified dendritic cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-21 inhibitors could target GA-MSCs and reduce CD73 expression on MDSCs, potentially synergizing with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy. This indicates that while GA-MSCs can promote glioma growth and immunosuppression, there is potential for therapeutic intervention through the modulation of exosomal content [93].

The promotive effects of exosomes from MSCs on glioma (the figure was drawn using AI and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license).

Specifically, MSCs Exo miR-1587 targets and reduces the levels of NCOR1. This reduction is directly associated with a significant increase in both the growth and clonality of GSCs. Additionally, MSCs play a crucial role as signal amplifiers. They intensify the immunosuppressive effects exerted by glioma exosomes, thereby contributing substantially to the progression of glioma.

Tumor-suppressing effects

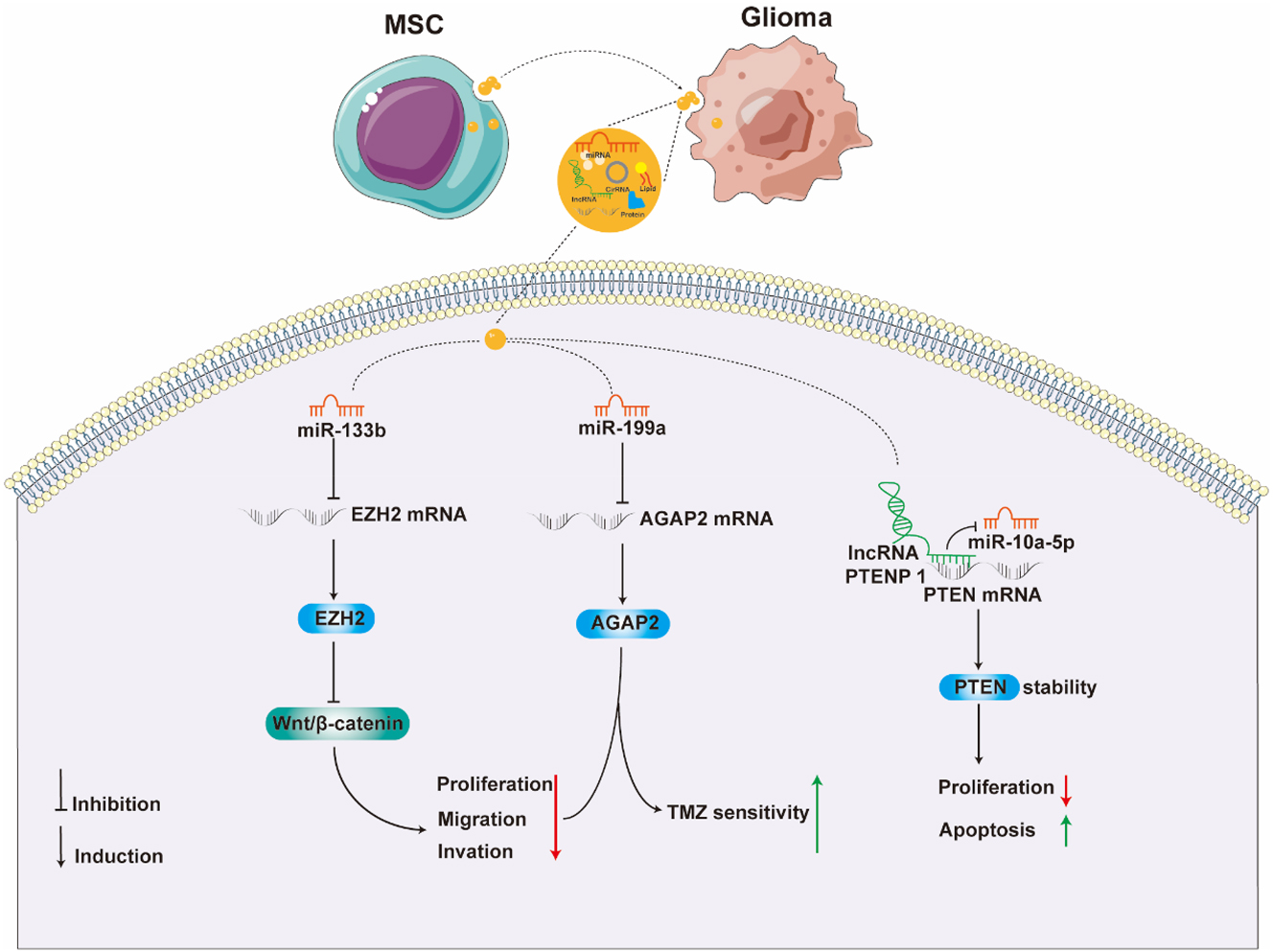

Recent research, as depicted in Figure 3, suggests that MSCs-Exo might play a role in hindering glioma progression. Parsaei et al. conducted a study where C6 cells were co-cultured with exosomes from varying concentrations of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (rBMMSCs). Their findings revealed that these exosomes predominantly induce cell death by promoting apoptosis, and at the same time, they noted a direct linear correlation between exosome concentration and cytotoxicity [94]. Further supporting these findings, Xu and colleagues discovered that exosomes from mouse BM-MSCs, containing miR-133b, significantly inhibit the expression of EZH2. This inhibition likely suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby reducing proliferation, migration, and invasion of glioma U87 cells in vitro. Complementary in vivo studies also demonstrate the capability of these exosomes to impede the progression of gliomas [95]. Additionally, research has indicated that long non-coding RNA PTENP1, encapsulated in exosomes from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs), plays a crucial role. It binds competitively with miR-10a-5p, stabilizing PTEN, which leads to the inhibition of U87 cell proliferation and promotion of apoptosis [96]. Yu et al. reported that exosomes from human MSCs (hMSCs) can transport miR-199a to U251 glioma cells. This transport inhibits cell proliferation, invasion, and migration by modulating AGAP2 expression. Moreover, hMSCs overexpressing miR-199a significantly enhanced the chemosensitivity to temozolomide and curtailed in vivo tumor growth [97]. Table 1 presents a summary, encompassing the origins and passage numbers of MSCs, as well as an overview of the roles, underlying mechanisms, and experimental models associated with MSCs-Exo in the context of glioma research.

Inhibitory effects of MSCs Exo on glioma (the figure was drawn using AI and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license).

Effects and related mechanisms of MSCs Exo on glioma (“N/A” indicates not mentioned or not applicable).

| Donor cell | Receptor cell | Passage number of cell | Exo cargo | Expression | Mechanisms/targets | Function | Study model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-HMSCs | GSCs | Within five generations | miR-1587 | Up | NCOR1 | Increase tumorigenicity of GSCs | In vitro and in vivo (GSCs-nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [92] |

| GA-MSCs | MDSCs | N/A | miR-21 | Up | CD73 | Amplifying immunosuppressive signals | In vitro and in vivo (GL261-C57BL/6 in situ tumor formation) | [93] |

| rBMMSCs | C6 | The third passage | N/A | N/A | N/A | Promote c6 cell apoptosis, inhibit migration and invasion | In vitro | [94] |

| MSCs | U87 | The third passage | miR-133 b | N/A | Wnt/β-catenin-EZH 2 | Inhibit glioma cell proliferation, migration and invasion | In vitro and in vivo (U87-nude mice subcutaneous tumor formation) | [95] |

| hUC-MSCs | U87 | Within 8 passages | lncRNA PTENP 1 | N/A | miR-10a-5 p/PTEN | Promote U87 cell apoptosis, inhibit proliferation | In vitro | [96] |

| hMSCs | U251 | The third passage | miR-199 a | N/A | AGAP 2 | Inhibit glioma cell proliferation, migration and invasion; enhance the chemosensitivity of temozolomide | In vitro and in vivo (U251-Balb/c nude mice subcutaneous tumor formation) | [97] |

MSC Exo is capable of transporting miRNA or lncRNA, which through modulation of the expression or stability of EZH2, AGAP2, and PTEN, impacts the apoptosis, growth, migration, invasion, and drug tolerance of glioma cells, constraining glioma advancement.

Advancements of MSCs Exo in glioma therapy

Introduction to exosome drug loading methods

As depicted in Figure 4, there are two primary methods for loading therapeutic drugs into MSCs Exo: (1) the direct method involves encapsulating drugs into exosomes using various techniques; (2) the indirect method includes generating exosomes that carry different biomolecules (like nucleic acids, proteins) through genetic engineering or by co-incubating cells with therapeutic drugs. For direct drug encapsulation into exosomes, techniques such as electroporation, incubation, extrusion, ultrasonication, saponification, and freeze-thaw cycles are employed. Incubation, being the most common method, is simple but has relatively low efficiency in drug loading. Electroporation, in contrast, is more efficient but risks disrupting exosome structure due to electric field-induced protein or RNA clusters, potentially reducing drug delivery effectiveness [98]. Ultrasonication is noted for its high efficiency, but it can also damage exosome structure and lead to protein aggregation [99]. While ultrasonication is more damaging to exosomal integrity compared to other methods [100]. Extrusion stands out by producing uniform exosomes, thereby enhancing drug delivery efficiency [101]. However, improper mechanical pressure during extrusion can harm the exosome structure [102]. Freeze-thaw cycles, commonly used in drug delivery systems, may alter the physicochemical properties of the exosome membrane and are less efficient than ultrasonication in drug loading [101, 102]. Currently, incubation and electroporation are the most frequently used techniques for drug loading in MSCs Exo. With their notable drug delivery advantages, MSCs Exo have been extensively utilized in tumor treatment strategies.

Schematic diagram of exosome drug loading techniques (the figure was drawn using AI and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license).

Two primary techniques are employed to produce exosomes containing therapeutic agents: the direct and indirect methods.

The indirect method involves either incubating cells with drug molecules or using transfection or transduction with expression vectors. These approaches prompt cells to release Exo that carry drug molecules, viral proteins, nucleic acids, and proteins.

The direct method starts with isolating exosomes. Subsequently, therapeutic drugs are loaded into these Exo either through passive incubation or active methods such as electroporation, saponin treatment, freeze-thaw cycles, ultrasonication, and extrusion.

Treatment of glioma with drug-loaded MSCs exo

Del Fattore et al. successfully loaded vincristine into MSC EVs derived from the umbilical cord using a co-incubation method with drugs and cells. Their research demonstrated a notably increased cytotoxic effect on U87 glioblastoma cells compared to both free vincristine and unloaded EVs, thereby confirming the efficacy of MSC EVs in delivering anti-tumor drugs directly to glioblastoma cells [103]. Additionally, researchers investigated the loading of various concentrations of atorvastatin into exosomes from human endometrial mesenchymal stem cells (hEnMSCs) using an incubation technique. These exosomes were then co-cultured with 3D spheroids of U87 glioblastoma and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). The findings indicated that hEnMSCs-Exo loaded with atorvastatin significantly inhibited angiogenesis and tumor migration and proliferation. Notably, higher concentrations of atorvastatin in the exosomes resulted in more pronounced anti-tumor effects [25] (Figure 5A). In conclusion, encapsulating anti-cancer drugs in exosomes not only enhances their solubility, bioavailability, and stability but also prevents rapid drug degradation and undesirable distribution to various tissues. Due to their nano-sized dimensions, exosomes are capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, enabling efficient and targeted drug delivery to the brain. Consequently, exosomes loaded with anti-tumor drugs, such as those from MSCs, represent a highly promising and effective approach for glioblastoma therapy, warranting further investigation.

Drug loading and miRNA overexpression in MSCs exosomes for glioma treatment (the figure was drawn using AI and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license). (A) Drugs are loaded into MSCs exosomes through co-incubation, influencing gliomas’ proliferation, angiogenesis, and cytotoxic response. (B) miRNA overexpression in exosomes, facilitated by plasmid transfection, impacts glioma characteristics such as drug resistance, proliferative capacity, migration ability, apoptosis efficiency, and angiogenic potential.

MSCs Exo-mediated overexpression of miRNA in glioma therapy

Enhance the sensitivity of chemotherapy or anti-cancer agents

Sharif et al. discovered that miR-124, transported via exosomal mechanisms or independently, can be successfully delivered to U87 GBM cells in conjunction with Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells (WJ-MSCs) from the human umbilical cord. This process targets cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6), thereby enhancing the chemosensitivity of U87 cells to temozolomide (TMZ) and reducing their migration [27]. In the context of TMZ resistance, miR-9 is upregulated in GBM cells and contributes to the expression of the drug efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp). To mitigate miR-9’s role in promoting drug resistance, a Cyanine 5(Cy5)-labeled anti-miR-9 strategy was employed. This research revealed that exosomes from hMSCs were crucial in the delivery of anti-miR-9. Additionally, these hMSC-derived exosomes, when overexpressing anti-miR-9, effectively reduced P-gp levels, reversing TMZ resistance in U87 and T98G GBM cells [28]. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) has emerged as a promising anticancer agent. It’s been shown that therapeutic miR-7, overexpressed in TRAIL-BMMSCs and loaded into cell-derived exosomes, enhances TRAIL sensitivity by targeting and suppressing X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), leading to significant apoptosis in U87 cells. Moreover, in vivo studies highlight that mouse BMMSCs co-expressing TRAIL and miR-7, through their exosomes, synergize to exert an anti-tumor effect [104].

Inhibition of tumor proliferation and migration

Lang et al. utilized a miR-124a lentiviral vector to transduce human MSCs derived from bone marrow. They co-cultured these cells with GSCs using isolated MSCs-Exo-miR124, which significantly reduced the viability and clonogenicity of GSCs. When used to intervene in GSC267-bearing nude mice, MSC s-Exo-miR124 enabled 50 % of the mice to achieve long-term survival. Mechanistic studies revealed that miR-124a suppresses tumor proliferation by silencing Forkhead box A2 (FoxA2), leading to abnormal intracellular lipid accumulation [21]. Katakowski’s work involved transfecting rat bone marrow-derived MSCs with miR-146b expression plasmids. By co-culturing overexpressing miR-146b MSCs derived exosomes with 9L cells, the growth ability of 9L cells was reduced. Further, intratumoral injection of these exosomes in in situ brain tumor rat models significantly diminished the growth of glioma xenografts [22]. Kim et al. discovered that hMSCs Exo overexpressing miRNA-584-5P inhibit u87 cell proliferation and migration while promoting apoptosis. This effect is achieved by targeting Cytochrome P450 2J2 (CYP2J2) and suppressing the Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. In subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice treated with these MSCs Exo, tumor volume and weight were notably reduced [20]. Research has shown that exosomes from hMSCs overexpressing miR-375 inhibit U87 solute carrier family 31 member 1 (SLC31A1) expression in glioma cells, suppressing their proliferation, migration, and invasion, and promoting apoptosis. In vivo experiments have confirmed that these exosomes can inhibit the growth of xenografted tumors in nude mice [105]. Yan et al. discovered that bone mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC)-derived exosomes containing miR-512-5p can suppress U87 cell proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest by downregulating Jagged1 (JAG1) expression. BMSC-Exo-miR-512-5p has been shown to inhibit the growth of mouse glioblastoma, thus prolonging survival [106]. Focused ultrasound (FUS) facilitates a transient, reversible, and localized opening of the BBB. Zhan et al. used hBMSCs-derived Exo as carriers for the tumor-suppressing gene miR-1208. Post-FUS exposure, an increased number of Exo carrying miR-1208 crossed the BBB, enhancing the uptake of miR-1208 by glioma cells U251 and U373. Mechanistically, miR-1208 suppresses methyltransferase-like 3(METTL3) expression, reducing the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation level of Nucleoporin 214 (NUP214) mRNA. This reduction leads to decreased NUP214 expression and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway activity, effectively suppressing tumor growth in vivo and in vitro [39].

Anti-angiogenesis

Vasculogenic mimicry (VM) provides an alternative microvascular circulation in tumors, independent of VEGF-driven angiogenesis. This process results in the formation of highly patterned vascular channels, particularly noted in gliomas, where VM structures are formed by differentiated tumor cells [107]. VM bypasses standard angiogenic mechanisms, a critical factor in sustaining the malignancy progression in GBM [108]. However, the molecular basis of VM formation remains only partially understood, leading to a lack of targeted therapies. In addressing this, Zhang et al. engineered hMSCs to produce exosomes with increased miR-29a-3p expression. This innovation inhibits glioma cell migration and VM formation, presenting a potential augmentation to current clinical treatments targeting angiogenesis [24]. In summary, modulating miRNA overexpression within exosomes can influence glioma characteristics, including drug resistance, growth, migration, apoptosis proficiency, and angiogenesis, offering promising avenues for effective glioma therapy (Figure 5B).

Engineering MSCs Exo for enhanced targeting

Strategies for the engineered modification of Exo

The limited therapeutic effectiveness of chemotherapy drugs largely stems from their systemic and non-targeted nature. In contrast, exosomes, while promising as drug delivery carriers, still face challenges in targeting efficiency. To address this, researchers have developed engineered exosomes for cell-specific targeting. By modifying their surface molecules, these exosomes gain cell and tissue specificity, allowing for the targeted delivery of specific tumor treatment molecules. The surface modification of exosomes can be achieved through genetic engineering or chemical modification. Genetic engineering involves fusing the gene sequences of guide proteins or peptides with those of select exosomal membrane proteins, thus displaying these guiding elements on the exosome surface. On the other hand, chemical modification employs conjugation reactions or lipid assembly to display a range of natural and synthetic ligands. However, the intricate nature of the exosome surface can sometimes reduce the efficiency of these reactions and potentially compromise the integrity and functionality of the carriers.

Currently, genetic engineering is a prevalent method for modifying exosomal surface proteins. In this process, ligands or targeting peptides are first fused with the genes of transmembrane proteins present on the exosome surface. Donor cells are then transfected with plasmids encoding these fusion proteins, leading to the production of exosomes that carry targeted ligands on their surface. A notable example is the work of Michelle E, who designed targeted peptide-Lamp2b fusion proteins with incorporated glycosylation sequences. These sequences protect the peptides from degradation and increase the overall expression of Lamp2b fusion proteins in both cells and exosomes. The glycosylation enhances the stability of these peptides, improving the targeting capabilities of the exosomes towards neuroblastoma cells [109].

Additionally, a technique known as “click chemistry” has been developed for covalently attaching modifications to the exosome surface. This method is advantageous due to its compatibility and rapid reaction rates. Nonetheless, careful control of several parameters, such as pressure, temperature, and osmotic pressure, is crucial during modification to prevent exosome rupture [110]. For instance, researchers have successfully targeted brain injury areas in cerebral ischemia models by attaching c(RGDyK) peptides to the exosome surface using bioorthogonal chemistry [111]. Another approach involves using non-covalent modifications to incorporate specific ligands or receptors onto exosome surfaces [110]. Kooijmans and colleagues, for example, combined epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-specific nanobodies with phospholipid (DMPE)-polyethylene glycol derivatives to create nanobody-polyethylene glycol (PEG) micelles. These micelles can be integrated into exosome surfaces without altering their morphology, size distribution, or protein composition, significantly extending their circulation time and enhancing their tumor cell targeting capabilities [112].

The role of engineered modified MSCs Exo in glioma treatment

Rahmani et al. engineered MSCs Exo to merge with the anti-EGFRvIII antibody (ab139 scfv) linked to transmembrane protein Lamp 2b, and encapsulated both cytidine deaminase (CDA) and miR-34a, genes known for inducing apoptosis. The study revealed a significantly higher apoptosis induction rate in U87EGFRvIII cells compared to U87 cells, showcasing the selectivity of the engineered exosomes. Notably, after introducing CDA, miR-34a, and CDAmiR, the mortality rates in U87 cells were 6 %, 9 %, and 12 %, respectively, whereas for U87EGFRvIII cells, they increased to 13 %, 21 %, and 40 %. This indicates that bioengineered exosomes, carrying two gene therapy agents and targeting EGFRvIII antigen, substantially elevate apoptosis rates in GBM cells [32] (Figure 6A). Addressing TMZ-resistant GBM cells, which exhibit high heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX-1) expression, researchers modified bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell exosomes (BMSC Exo) with HMOX-1 specific short peptides (HSSP) and encapsulated TMZ and STAT3 specific small interfering RNA (siSTAT3). In vitro and in vivo experiments showed that HSSP-BMSC Exo effectively targeted anti-TMZ GBM and, by silencing STAT3, modulated the STAT3-O6 methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) pathway to induce apoptosis in TMZ resistant U251 (U251-TR) cells, thereby restoring drug sensitivity in these gliomas (Figure 6B). The allogeneic engineered HSSP-BMSC Exo thus emerges as an excellent carrier for TMZ-resistant GBM, characterized by outstanding biocompatibility, effective BBB penetration, prolonged blood circulation time, and specific targeting [33]. In conclusion, mesenchymal stem cell exosomes offer a versatile platform for loading anti-tumor drugs. By attaching protein encoding sequences or polypeptide links to their surface, their targeting ability can be significantly enhanced, optimizing the therapeutic impact. The therapeutic actions and mechanisms of MSCs Exo in glioma treatment are detailed in Table 2.

Engineered MSCs Exo in glioma treatment (the figure was drawn using AI and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license).

The therapeutic effects of MSCs Exo on glioma and related mechanisms (“N/A” indicates not mentioned or not applicable).

| Exo/Evs type | Receptor cell | Passage number of cell | Loading drugs/overexpressed molecules | Surface modification | Mechanisms/targets | Function | Study model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC-MSC-EVs | U87 | The third passage | Vincristine | N/A | N/A | Promote U87 cell apoptosis | In vitro | [103] |

| hEnMSCs-Exo | U87/HUVECs | The third passage | Atorvastatin | N/A | N/A | Anti-tumor angiogenesis, migration and proliferation | In vitro | [25] |

| Wharton’s jelly-MSCs-Exo | U87 | Passage 3–4 | miR-124 | N/A | CDK6 | Promote chemotherapy sensitivity of glioma cells | In vitro | [27] |

| hMSC-Exo | U87 T98G | N/A | anti-miR-9-Cy5 | N/A | miR-9 | Promote chemotherapy sensitivity of glioma cells | In vitro | [28] |

| TRAIL-MSCs-Exo | U87 | N/A | miR-7 | N/A | XIAP | Increase the sensitivity of TRAIL and synergize against tumors | In vitro and in vivo (U87-Balb/c nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [104] |

| hMSCs-Exo | GSCs | Passage 3–4 | miR-124a | N/A | (FOX)A2 | Reduce the viability and clonality of GSCs and prolong the survival of tumor-bearing mice | In vitro and in vivo (GSC267-Balb/c nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [21] |

| BMMSCs-Exo | 9L | N/A | miR-146b | N/A | EGFR/NF-κB | Inhibit the growth of 9L cells in vitro and slow down tumor progression in vivo | In vitro and in vivo (9L-Fischer rat in situ tumor formation) | [22] |

| hMSCs-Exo | U87 | N/A | miRNA-584-5P | N/A | CYP2J2-AKT/MAPK | Inhibition of U87 invasion in vitro and slowing of tumor progression in vivo | In vitro and in vivo (U87-nude mice subcutaneous tumor formation) | [20] |

| hMSCs-Exo | U87 | N/A | miR-375 | N/A | SLC31 A1 | In vitro suppression of U87’s proliferation, migration, and invasion, promotion of apoptosis, and in vivo inhibition of xenograft tumor growth in nude mice | In vitro and in vivo (xenograft tumors in nude mice/specific tumorigenesis method unclear) | [105] |

| BMSC-Exo | U87 | The third passage | miR-512-5p | N/A | JAG1 | Inhibits glioblastoma cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest in vitro, inhibits glioblastoma growth and prolongs survival in mice in vivo | In vitro and in vivo (U87-nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [106] |

| hMSCs-Exo | U251/U373 | N/A | miR-1208 | N/A | METTL3/NUP214/TGF-β | Enhances hBMSCs-Exo-miR-1208 crossing the BBB; effectively inhibits tumor growth in vivo and in vitro | In vitro and in vivo (U251-female BALB/c nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [39] |

| hMSCs-Exo | U87/A172 | N/A | miR-29a-3p | N/A | ROBO1 | Inhibits glioma cell migration and VM formation | In vitro and in vivo (U87-Balb/c nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [24] |

| UCMSC-Exo | U87 | N/A | CDA/miR-34a | Anti-EGFRvIII antibody | N/A | Promote U87 cell apoptosis | In vitro | [32] |

| BMSC-Exo | U251-TR | N/A | TMZ/siSTAT3 | HSSP | STAT3-MGMT axis | Induces apoptosis in U251-TR cells and restores sensitivity of drug-resistant glioma to TMZ | In vitro and in vivo (U251-TR-Balb/c nude mice in situ tumor formation) | [33] |

Surface modifications on exosomes enable the attachment of protein-coding sequences or peptides, which significantly enhances their targeting capabilities towards glioma cells. Additionally, these exosomes, when loaded with overexpressed gene therapy drugs or anti-tumor agents, can markedly induce apoptosis in glioma cells. This approach not only reduces chemotherapy resistance but also substantially improves the effectiveness of anti-tumor drugs.

Discussion and summary

There are still urgent issues to be resolved in the study of MSCs Exo in regulating glioma progression and its use as an engineered carrier for anti-tumor drugs. Current research primarily explores the impact of non-coding RNAs within MSCs Exo on glioma progression. However, future studies should broaden their scope to include the roles of other nucleic acids, lipids, proteins, and even mitochondria. Current studies on MSC therapy for glioma predominantly utilize BM-MSCs from humans or mice, and human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (Tables 1 and 2). One study reported that exosomes from adipose-derived MSCs do not inhibit glioma cell invasiveness [103], contrasting with another study that found exosomes from adipose sources can transfer miR-218 to breast cancer cells, reducing their invasiveness [113]. Thus, one significant challenge is identifying a consistent and suitable source of MSCs for drug delivery, as variations in MSC origins lead to exosomes with differing sizes, compositions, and functionalities. Additionally, the effect of cell passage number on exosome content remains unclear. While most research employs third or fourth generation MSCs for exosome collection, the impact of different generations on exosome contents and surface properties is not well understood. MSCs Exo retain certain characteristics of their parent cells, including tumor-specific targeting abilities. However, their specific molecular targeting mechanisms are not yet thoroughly studied. Future research should therefore delve into these molecular mechanisms to enhance targeting capabilities through genetic engineering. There is also a lack of research on how MSC exosomes affect different sources and types of glioma cells, an area that needs further exploration. Most existing research is confined to laboratory settings, presenting challenges in transitioning bioengineered MSCs Exo to clinical applications. The biological origins and mechanisms of exosomes are not fully understood, and numerous factors influence their formation, integration into target cells, profiling, and purification. These factors impact the modification and drug loading of exosomes. Another hurdle is the mass production of exosomes, requiring standardized processes for their separation, purification, drug loading, and modification. For MSCs in particular, the purification and cultivation conditions in the human body are stringent, adding to the complexity. In summary, the clinical application of MSCs Exo requires optimization in several areas, including large-scale production, separation, drug loading, and surface modification.

MSCs Exo, as a critical medium for intercellular communication, plays a pivotal role in glioma progression. While the exact function of MSCs Exo in glioma is still under debate, mainly due to variations in MSC origins and glioma progression stages, their potential as carriers for therapeutic drugs is broad and undeniable. MSCs not only possess common exosomal characteristics and unique advantages but also produce more exosomes compared to other cells, demonstrating strong tumor targeting capability. This capability could be further enhanced by surface modifications and alterations in content, improving the targeting and inhibition of glioma invasion. However, research on MSCs Exo is still in its infancy, with many unanswered questions. Our aim is to overcome these challenges soon and develop a more efficient and comprehensive glioma treatment strategy based on MSCs Exo.

Funding source: NHC Key Laboratory of Diagnosis and Therapy of Gastrointestinal Tumor Open Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: NLDTG2020005

Funding source: the Natural Science Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Gansu Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22JR5RA509

Funding source: the Gansu Province Health Industry Scientific Research Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: GSWSKY2021-017

Funding source: the Lanzhou City Chengguan District Science and Technology Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021-9-3

Funding source: the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Provincial Department of Science and Technology

Award Identifier / Grant number: 20JR5RA344

Funding source: the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 31870335

Funding source: the “Cuiying Technology Innovation” Planning Project of Lanzhou University Second Hospital

Award Identifier / Grant number: CY2021-MS-B01

Acknowledgments

The Figure was partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Tianfei Ma and Gang Su are co-first authors of the article. They reviewed the references and wrote the manuscript. Qionghui Wu, Minghui Shen and Xinli Feng edited and corrected the manuscript. Zhenchang Zhang planned the manuscript, he is the corresponding author of the article.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870335); the Natural Science Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Gansu Province (22JR5RA509); NHC Key Laboratory of Diagnosis and Therapy of Gastrointestinal Tumor Open Project (NLDTG2020005); The Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Provincial Department of Science and Technology (20JR5RA344); the Gansu Province Health Industry Scientific Research Project (GSWSKY2021-017); the Lanzhou City Chengguan District Science and Technology Project (2021-9-3); and the “Cuiying Technology Innovation” Planning Project of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (CY2021-MS-B01).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Omuro, A, DeAngelis, LM. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas a clinical review. JAMA 2013;310:1842–50, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.280319.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Molinaro, AM, Taylor, JW, Wiencke, JK, Wrensch, MR. Genetic and molecular epidemiology of adult diffuse glioma. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:405–17, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0220-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Brandes, AA, Tosoni, A, Franceschi, E, Reni, M, Gatta, G, Vecht, C. Glioblastoma in adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat 2008;67:139–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Yang, C, Lei, DQ, Ouyang, WX, Ren, JH, Li, HY, Hu, JQ, et al.. Conditioned media from human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells and umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells efficiently induced the apoptosis and differentiation in human glioma cell lines in vitro. BioMed Res Int 2014;2014:109389, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/109389.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Sai, K, Yang, QY, Shen, D, Chen, ZP. Chemotherapy for gliomas in mainland China: an overview. Oncol Lett 2013;5:1448–52, https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2013.1264.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Ho, IAW, Toh, HC, Ng, WH, Teo, YL, Guo, CM, Hui, KM, et al.. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells suppress human glioma growth through inhibition of angiogenesis. Stem Cell 2013;31:146–55, https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.1247.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Reagan, MR, Kaplan, DL. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cell tumor-homing: detection methods in disease model systems. Stem Cell 2011;29:920–7, https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.645.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Mok, PL, Leong, CF, Cheong, SK. Cellular mechanisms of emerging applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Malays J Pathol 2013;35:17–32.Search in Google Scholar

9. Khakoo, AY, Pati, S, Anderson, SA, Reid, W, Elshal, MF, RoviraII, et al.. Human mesenchymal stem cells exert potent antitumorigenic effects in a model of Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Exp Med 2006;203:1235–47, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20051921.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Whiteside, TL. Exosome and mesenchymal stem cell cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Immunol 2018;35:69–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2017.12.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Shi, Y, Du, L, Lin, L, Wang, Y. Tumour-associated mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: emerging therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16:35–52, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.193.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Seo, Y, Kim, H-S, Hong, I-S. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles as immunomodulatory therapeutics. Stem Cell Int 2019;2019:5126156, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5126156.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Mathivanan, S, Ji, H, Simpson, RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics 2010;73:1907–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Kalluri, R, LeBleu, VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020;367:eaau6977, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau6977,Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. van Niel, G, Carter, DRF, Clayton, A, Lambert, DW, Raposo, G, Vader, P. Challenges and directions in studying cell-cell communication by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022;23:369–82, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00460-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Wu, J-Y, Li, Y-J, Hu, X-B, Huang, S, Luo, S, Tang, T, et al.. Exosomes and biomimetic nanovesicles-mediated anti-glioblastoma therapy: a head-to-head comparison. J Control Release 2021;336:510–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.07.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Wang, J, Tang, W, Yang, M, Yin, Y, Li, H, Hu, F, et al.. Inflammatory tumor microenvironment responsive neutrophil exosomes-based drug delivery system for targeted glioma therapy. Biomaterials 2021;273:120784, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Thakur, A, Sidu, RK, Zou, H, Alam, MK, Yang, M, Lee, Y. Inhibition of glioma cells’ proliferation by doxorubicin-loaded exosomes via microfluidics. Int J Nanomedicine 2020;15:8331–43, https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s263956.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Qian, C, Wang, Y, Ji, Y, Chen, D, Wang, C, Zhang, G, et al.. Neural stem cell-derived exosomes transfer miR-124-3p into cells to inhibit glioma growth by targeting FLOT2. Int J Oncol 2022;61:1–12, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2022.5405.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Kim, R, Lee, S, Lee, J, Kim, M, Kim, WJ, Lee, HW, et al.. Exosomes derived from microRNA-584 transfected mesenchymal stem cells: novel alternative therapeutic vehicles for cancer therapy. BMB Rep 2018;51:406–11, https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2018.51.8.105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Lang, FM, Hossain, A, Gumin, J, Momin, EN, Shimizu, Y, Ledbetter, D, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cells as natural biofactories for exosomes carrying miR-124a in the treatment of gliomas. Neuro Oncol 2018;20:380–90, https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox152.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Katakowski, M, Buller, B, Zheng, X, Lu, Y, Rogers, T, Osobamiro, O, et al.. Exosomes from marrow stromal cells expressing miR-146b inhibit glioma growth. Cancer Lett 2013;335:201–4, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Yang, Z, Shi, J, Xie, J, Wang, Y, Sun, J, Liu, T, et al.. Large-scale generation of functional mRNA-encapsulating exosomes via cellular nanoporation. Nat Biomed Eng 2020;4:69–83, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-019-0485-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Zhang, Z, Guo, X, Guo, X, Yu, R, Qian, M, Wang, S, et al.. MicroRNA-29a-3p delivery via exosomes derived from engineered human mesenchymal stem cells exerts tumour suppressive effects by inhibiting migration and vasculogenic mimicry in glioma. Aging 2021;13:5055–68, https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202424.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Valipour, E, Ranjbar, FE, Mousavi, M, Ai, J, Malekshahi, ZV, Mokhberian, N, et al.. The anti-angiogenic effect of atorvastatin loaded exosomes on glioblastoma tumor cells: an in vitro 3D culture model. Microvasc Res 2022;143:104385, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2022.104385.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Wang, K, Kumar, US, Sadeghipour, N, Massoud, TF, Paulmurugan, R. A microfluidics-based scalable approach to generate extracellular vesicles with enhanced therapeutic microRNA loading for intranasal delivery to mouse glioblastomas. ACS Nano 2021;15:18327–46, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c07587.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Sharif, S, Ghahremani, MH, Soleimani, M. Delivery of exogenous miR-124 to glioblastoma multiform cells by Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells decreases cell proliferation and migration, and confers chemosensitivity. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2018;14:236–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-017-9788-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Munoz, JL, Bliss, SA, Greco, SJ, Ramkissoon, SH, Ligon, KL, Rameshwar, P. Delivery of functional anti-miR-9 by mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes to glioblastoma multiforme cells conferred chemosensitivity. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2013;2:e126, https://doi.org/10.1038/mtna.2013.60.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Li, C, Guan, N, Liu, F. T7 peptide-decorated exosome-based nanocarrier system for delivery of Galectin-9 siRNA to stimulate macrophage repolarization in glioblastoma. J NeuroOncol 2023;162:93–108, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04257-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Bu, N, Wu, H, Zhang, G, Zhan, S, Zhang, R, Sun, H, et al.. Exosomes from dendritic cells loaded with chaperone-rich cell lysates elicit a potent T cell immune response against intracranial glioma in mice. J Mol Neurosci 2015;56:631–43, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-015-0506-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Liu, H, Chen, L, Liu, J, Meng, H, Zhang, R, Ma, L, et al.. Co-delivery of tumor-derived exosomes with alpha-galactosylceramide on dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Cancer Lett 2017;411:182–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2017.09.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Rahmani, R, Kiani, J, Tong, WY, Soleimani, M, Voelcker, NH, Arefian, E. Engineered anti-EGFRvIII targeted exosomes induce apoptosis in glioblastoma multiforme. J Drug Target 2022:31, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1080/1061186x.2022.2152819.Search in Google Scholar

33. Rehman, FU, Liu, Y, Yang, Q, Yang, H, Liu, R, Zhang, D, et al.. Heme oxygenase-1 targeting exosomes for temozolomide resistant glioblastoma synergistic therapy. J Control Release 2022;345:696–708, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.03.036.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Li, B, Chen, X, Qiu, W, Zhao, R, Duan, J, Zhang, S, et al.. Synchronous disintegration of ferroptosis defense axis via engineered exosome‐conjugated magnetic nanoparticles for glioblastoma therapy. Adv Sci 2022;9:2105451, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202105451.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Wu, T, Liu, Y, Cao, Y, Liu, Z. Engineering macrophage exosome disguised biodegradable nanoplatform for enhanced sonodynamic therapy of glioblastoma. Adv Mater 2022;34:2110364, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202110364.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Liang, S, Xu, H, Ye, B-C. Membrane-decorated exosomes for combination drug delivery and improved glioma therapy. Langmuir 2021;38:299–308, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.1c02500.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Jia, G, Han, Y, An, Y, Ding, Y, He, C, Wang, X, et al.. NRP-1 targeted and cargo-loaded exosomes facilitate simultaneous imaging and therapy of glioma in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials 2018;178:302–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Bai, L, Liu, Y, Guo, K, Zhang, K, Liu, Q, Wang, P, et al.. Ultrasound facilitates naturally equipped exosomes derived from macrophages and blood serum for orthotopic glioma treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019;11:14576–87, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b00893.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Zhan, Y, Song, Y, Qiao, W, Sun, L, Wang, X, Yi, B, et al.. Focused ultrasound combined with miR-1208-equipped exosomes inhibits malignant progression of glioma. Br J Cancer 2023;129:1083–94, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-023-02393-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Roccaro, AM, Sacco, A, Maiso, P, Azab, AK, Tai, Y-T, Reagan, M, et al.. BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J Clin Invest 2013;123:1542–55, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci66517.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Fonsato, V, Collino, F, Herrera, MB, Cavallari, C, Deregibus, MC, Cisterna, B, et al.. Human liver stem cell-derived microvesicles inhibit hepatoma growth in SCID mice by delivering antitumor microRNAs. Stem Cells 2012;30:1985–98, https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.1161.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Yong, T, Wang, D, Li, X, Yan, Y, Hu, J, Gan, L, et al.. Extracellular vesicles for tumor targeting delivery based on five features principle. J Control Release 2020;322:555–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.03.039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Batrakova, EV, Kim, MS. Development and regulation of exosome-based therapy products. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2016;8:744–57, https://doi.org/10.1002/wnan.1395.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Pardridge, WM. A historical review of brain drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:1283, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14061283,Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Squillaro, T, Peluso, G, Galderisi, U. Clinical trials with mesenchymal stem cells: an update. Cell Transpl 2016;25:829–48, https://doi.org/10.3727/096368915x689622.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Pittenger, MF, Mackay, AM, Beck, SC, Jaiswal, RK, Douglas, R, Mosca, JD, et al.. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999;284:143–7, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.284.5411.143.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Galipeau, J, Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell 2018;22:824–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Hidalgo-Garcia, L, Galvez, J, Rodriguez-Cabezas, ME, Anderson, PO. Can a conversation between mesenchymal stromal cells and macrophages solve the crisis in the inflamed intestine? Front Pharmacol 2018;9:179, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00179.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Zhou, Y, Yamamoto, Y, Xiao, Z, Ochiya, T. The immunomodulatory functions of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells mediated via paracrine activity. J Clin Med 2019;8:1025, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8071025,Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Shah, K. Mesenchymal stem cells engineered for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012;64:739–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2011.06.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Lan, T, Luo, M, Wei, X. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:195, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01208-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Lin, W, Huang, L, Li, Y, Fang, B, Li, G, Chen, L, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cells and cancer: clinical challenges and opportunities. BioMed Res Int 2019;2019:2820853, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2820853.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Karlsson, C, Emanuelsson, K, Wessberg, F, Kajic, K, Axell, MZ, Eriksson, PS, et al.. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal progenitors – potential in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res 2009;3:39–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2009.05.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Gruenloh, W, Kambal, A, Sondergaard, C, McGee, J, Nacey, C, Kalomoiris, S, et al.. Characterization and in vivo testing of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng A 2011;17:1517–25, https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0460.Search in Google Scholar

55. Yen, M-L, Hou, C-H, Peng, K-Y, Tseng, P-C, Jiang, S-S, Shun, C-T, et al.. Efficient derivation and concise gene expression profiling of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal progenitors (EMPs). Cell Transpl 2011;20:1529–45, https://doi.org/10.3727/096368910x564067.Search in Google Scholar

56. Lotfinia, M, Lak, S, Ghahhari, NM, Johari, B, Maghsood, F, Parsania, S, et al.. Hypoxia pre-conditioned embryonic mesenchymal stem cell secretome reduces IL-10 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Iran Biomed J 2017;21:24–31, https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.ibj.21.1.24.Search in Google Scholar

57. Bak, XY, Dang, HL, Yang, J, Ye, K, Lee, EX, Lim, SK, et al.. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells as cellular delivery vehicles for prodrug gene therapy of glioblastoma. Hum Gene Ther 2011;22:1365–77, https://doi.org/10.1089/hum.2010.212.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Jakob, M, Hambrecht, M, Spiegel, JL, Kitz, J, Canis, M, Dressel, R, et al.. Pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells show comparable functionality to their autologous origin. Cells 2020;10:33, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Baliña-Sánchez, C, Aguilera, Y, Adán, N, Sierra-Párraga, JM, Olmedo-Moreno, L, Panadero-Morón, C, et al.. Generation of mesenchymal stromal cells from urine-derived iPSCs of pediatric brain tumor patients. Front Immunol 2023;14:1022676, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1022676.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Loh, J-K, Wang, M-L, Cheong, S-K, Tsai, F-T, Huang, S-H, Wu, J-R, et al.. The study of cancer cell in stromal environment through induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Chin Med Assoc 2022;85:821–30, https://doi.org/10.1097/jcma.0000000000000759.Search in Google Scholar

61. Zhao, Q, Hai, B, Zhang, X, Xu, J, Koehler, B, Liu, F. Biomimetic nanovesicles made from iPS cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells for targeted therapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med 2020;24:102146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2019.102146.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Zhao, Q, Hai, B, Kelly, J, Wu, S, Liu, F. Extracellular vesicle mimics made from iPS cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021;12:1–13, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-020-02097-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Rezaie, J, Ahmadi, M, Ravanbakhsh, R, Mojarad, B, Mahbubfam, S, Shaban, SA, et al.. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles: the metastatic organotropism drivers. Life Sci 2022;289:120216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120216.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Vahabi, A, Rezaie, J, Hassanpour, M, Panahi, Y, Nemati, M, Rasmi, Y, et al.. Tumor cells-derived exosomal CircRNAs: novel cancer drivers, molecular mechanisms, and clinical opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol 2022;200:115038, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Zhang, Y, Liu, YF, Liu, HY, Tang, WH. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci 2019;9:19, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2,Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

66. Jadli, AS, Ballasy, N, Edalat, P, Patel, VB. Inside(sight) of tiny communicator: exosome biogenesis, secretion, and uptake. Mol Cell Biochem 2020;467:77–94, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-020-03703-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Shaban, SA, Rezaie, J, Nejati, V. Exosomes derived from senescent endothelial cells contain distinct pro-angiogenic miRNAs and proteins. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2022;22:592–601, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-022-09740-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Dang, Y, Guan, J. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Smart Mater Med 2020;1:10–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smaim.2020.04.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Matarredona, ER, Pastor, AM. Extracellular vesicle-mediated communication between the glioblastoma and its microenvironment. Cells 2019;9:96, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9010096.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70. Yang, TZ, Martin, P, Fogarty, B, Brown, A, Schurman, K, Phipps, R, et al.. Exosome delivered anticancer drugs across the blood-brain barrier for brain cancer therapy in Danio Rerio. Pharm Res 2015;32:2003–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-014-1593-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Batrakova, EV, Kim, MS. Using exosomes, naturally-equipped nanocarriers, for drug delivery. J Contr Release 2015;219:396–405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72. Gourlay, J, Morokoff, A, Luwor, R, Zhu, H-J, Kaye, A, Stylli, S. The emergent role of exosomes in glioma. J Clin Neurosci 2017;35:13–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2016.09.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Smyth, T, Kullberg, M, Malik, N, Smith-Jones, P, Graner, MW, Anchordoquy, TJ. Biodistribution and delivery efficiency of unmodified tumor-derived exosomes. J Control Release 2015;199:145–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

74. Harishkumar, M, Radha, M, Yuichi, N, Muthukalianan, GK, Kaoru, O, Shiomori, K, et al.. Designer exosomes: smart nano-communication tools for translational medicine. Bioengineering 2021;8:158, https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering8110158.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Phinney, DG, Pittenger, MF. Concise review: MSC-derived exosomes for cell-free therapy. Stem Cell 2017;35:851–8, https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.2575.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Yeo, RW, Lai, RC, Zhang, B, Tan, SS, Yin, Y, Teh, BJ, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cell: an efficient mass producer of exosomes for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013;65:336–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

77. Yang, N, Ding, Y, Zhang, Y, Wang, B, Zhao, X, Cheng, K, et al.. Surface functionalization of polymeric nanoparticles with umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell membrane for tumor-targeted therapy. ACS Appl Mater Inter 2018;10:22963–73, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b05363.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Roberts-Dalton, H, Cocks, A, Falcon-Perez, J, Sayers, E, Webber, J, Watson, P, et al.. Fluorescence labelling of extracellular vesicles using a novel thiol-based strategy for quantitative analysis of cellular delivery and intracellular traffic. Nanoscale 2017;9:13693–706, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr04128d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Ankrum, JA, Ong, JF, Karp, JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:252–60, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2816.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80. Zhao, T, Sun, F, Liu, JW, Ding, TY, She, J, Mao, F, et al.. Emerging role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in regenerative medicine. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2019;14:482–94, https://doi.org/10.2174/1574888x14666190228103230.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Li, M, Wang, J, Guo, P, Jin, L, Tan, X, Zhang, Z, et al.. Exosome mimetics derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells ablate neuroblastoma tumor in vitro and in vivo. Biomater Adv 2022;142:213161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.213161.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Kidd, S, Spaeth, E, Dembinski, JL, Dietrich, M, Watson, K, Klopp, A, et al.. Direct evidence of mesenchymal stem cell tropism for tumor and wounding microenvironments using in vivo bioluminescent imaging. Stem Cells 2009;27:2614–23, https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.187.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

83. Xu, S, Liu, B, Fan, J, Xue, C, Lu, Y, Li, C, et al.. Engineered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes with high CXCR4 levels for targeted siRNA gene therapy against cancer. Nanoscale 2022;14:4098–113, https://doi.org/10.1039/d1nr08170e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

84. Egea, V, Kessenbrock, K, Lawson, D, Bartelt, A, Weber, C, Ries, C. Let-7f miRNA regulates SDF-1α-and hypoxia-promoted migration of mesenchymal stem cells and attenuates mammary tumor growth upon exosomal release. Cell Death Dis 2021;12:516, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03789-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

85. Li, T, Wan, Y, Su, Z, Li, J, Han, M, Zhou, C. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-3940-5p inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis by targeting integrin α6. Dig Dis Sci 2021;66:1916–27, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06458-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

86. Wei, H, Chen, F, Chen, J, Lin, H, Wang, S, Wang, Y, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes as nanodrug carrier of doxorubicin for targeted osteosarcoma therapy via SDF1-CXCR4 axis. Int J Nanomedicine 2022;17:3483–95, https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s372851.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Li, Z, Jiang, Y, Liu, J, Fu, H, Yang, Q, Song, W, et al.. Exosomes from PYCR1 knockdown bone marrow mesenchymal stem inhibits aerobic glycolysis and the growth of bladder cancer cells via regulation of the EGFR/PI3K/AKT pathway. Int J Oncol 2023;63:1–13, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2023.5532.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

88. Yao, X, Mao, Y, Wu, D, Zhu, Y, Lu, J, Huang, Y, et al.. Exosomal circ_0030167 derived from BM-MSCs inhibits the invasion, migration, proliferation and stemness of pancreatic cancer cells by sponging miR-338-5p and targeting the Wif1/Wnt8/β-catenin axis. Cancer Lett 2021;512:38–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.04.030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

89. Liu, S-C, Cao, Y-H, Chen, L-B, Kang, R, Huang, Z-X, Lu, X-S. BMSC-derived exosomal lncRNA PTENP1 suppresses the malignant phenotypes of bladder cancer by upregulating SCARA5 expression. Cancer Biol Ther 2022;23:1–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2022.2102360.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

90. Salunkhe, S, Dheeraj, BM, Chitkara, D, Mittal, A. Surface functionalization of exosomes for target-specific delivery and in vivo imaging & tracking: strategies and significance. J Control Release 2020;326:599–614, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.042.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

91. Mendt, M, Rezvani, K, Shpall, E. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for clinical use. Bone Marrow Transpl 2019;54:789–92, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0616-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

92. Figueroa, J, Phillips, LM, Shahar, T, Hossain, A, Gumin, J, Kim, H, et al.. Exosomes from glioma-associated mesenchymal stem cells increase the tumorigenicity of glioma stem-like cells via transfer of miR-1587GA-hMSCs regulate GSCs via exosomal miRNA. Cancer Res 2017;77:5808–19, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-2524.Search in Google Scholar

93. Qiu, W, Guo, Q, Guo, X, Wang, C, Li, B, Qi, Y, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cells, as glioma exosomal immunosuppressive signal multipliers, enhance MDSCs immunosuppressive activity through the miR-21/SP1/DNMT1 positive feedback loop. J Nanobiotechnol 2023;21:1–19, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-01997-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

94. Parsaei, H, Moosavifar, MJ, Eftekharzadeh, M, Ramezani, R, Barati, M, Mirzaei, S, et al.. Exosomes to control glioblastoma multiforme: investigating the effects of mesenchymal stem cell‐derived exosomes on C6 cells in vitro. Cell Biol Int 2022;46:2028–40, https://doi.org/10.1002/cbin.11884.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

95. Xu, H, Zhao, G, Zhang, Y, Jiang, H, Wang, W, Zhao, D, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-133b suppresses glioma progression via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by targeting EZH2. Stem Cel Res Ther 2019;10:1–14, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-019-1446-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

96. Hao, S, Ma, H, Niu, Z, Sun, S, Zou, Y, Xia, H. hUC-MSCs secreted exosomes inhibit the glioma cell progression through PTENP1/miR-10a-5p/PTEN pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019;23:10013–23, https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201911_19568.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

97. Yu, L, Gui, S, Liu, Y, Qiu, X, Zhang, G, Zhang, X, et al.. Exosomes derived from microRNA-199a-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells inhibit glioma progression by down-regulating AGAP2. Aging 2019;11:5300–18, https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102092.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

98. Kooijmans, SAA, Stremersch, S, Braeckmans, K, de Smedt, SC, Hendrix, A, Wood, MJA, et al.. Electroporation-induced siRNA precipitation obscures the efficiency of siRNA loading into extracellular vesicles. J Contr Release 2013;172:229–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.08.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

99. Haney, MJ, Klyachko, NL, Zhaoa, YL, Gupta, R, Plotnikova, EG, He, ZJ, et al.. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson’s disease therapy. J Contr Release 2015;207:18–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

100. Jafari, D, Shajari, S, Jafari, R, Mardi, N, Gomari, H, Ganji, F, et al.. Designer exosomes: a new platform for biotechnology therapeutics. BioDrugs 2020;34:567–86, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00434-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

101. Kim, MS, Haney, MJ, Zhao, Y, Mahajan, V, Deygen, I, Klyachko, NL, et al.. Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells. Nanomed-Nanotechnol 2016;12:655–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

102. Le Saux, S, Aarrass, H, Lai-Kee-Him, J, Bron, P, Armengaud, J, Miotello, G, et al.. Post-production modifications of murine mesenchymal stem cell (mMSC) derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) and impact on their cellular interaction. Biomaterials 2020;231:119675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119675.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

103. Del Fattore, A, Luciano, R, Saracino, R, Battafarano, G, Rizzo, C, Pascucci, L, et al.. Differential effects of extracellular vesicles secreted by mesenchymal stem cells from different sources on glioblastoma cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2015;15:495–504, https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2015.997706.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

104. Zhang, X, Zhang, X, Hu, S, Zheng, M, Zhang, J, Zhao, J, et al.. Identification of miRNA-7 by genome-wide analysis as a critical sensitizer for TRAIL-induced apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:5930–44, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx317.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

105. Deng, SZ, Lai, MF, Li, YP, Xu, CH, Zhang, HR, Kuang, JG. Human marrow stromal cells secrete microRNA-375-containing exosomes to regulate glioma progression. Cancer Gene Ther 2020;27:203–15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-019-0079-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

106. Yan, T, Wu, M, Lv, S, Hu, Q, Zhu, X. Zeng, A, et al.. Exosomes derived from microRNA-512-5p-transfected bone mesenchymal stem cells inhibit glioblastoma progression by targeting JAG1. Aging 2021;13:9911–26, https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202747.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

107. Wu, HB, Yang, S, Weng, HY, Chen, Q, Zhao, XL, Fu, WJ, et al.. Autophagy-induced KDR/VEGFR-2 activation promotes the formation of vasculogenic mimicry by glioma stem cells. Autophagy 2017;13:1528–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2017.1336277.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

108. Liu, XM, Zhang, QP, Mu, YG, Zhang, XH, Sai, K, Pang, JCS, et al.. Clinical significance of vasculogenic mimicry in human gliomas. J Neuro Oncol 2011;105:173–9, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-011-0578-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

109. Hung, ME, Leonard, JN. Stabilization of exosome-targeting peptides via engineered glycosylation. J Biol Chem 2015;290:8166–72, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m114.621383.Search in Google Scholar

110. Salunkhe, S, Basak, M, Chitkara, D, Mittal, A. Surface functionalization of exosomes for target-specific delivery and in vivo imaging & tracking: strategies and significance. J Contr Release 2020;326:599–614, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.042.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

111. Tian, T, Zhang, H-X, He, C-P, Fan, S, Zhu, Y-L, Qi, C, et al.. Surface functionalized exosomes as targeted drug delivery vehicles for cerebral ischemia therapy. Biomaterials 2018;150:137–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

112. Kooijmans, S, Fliervoet, L, Van Der Meel, R, Fens, M, Heijnen, H, en H PvB, et al.. PEGylated and targeted extracellular vesicles display enhanced cell specificity and circulation time. J Contr Release 2016;224:77–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

113. Shojaei, S, Moradi-Chaleshtori, M, Paryan, M, Koochaki, A, Sharifi, K, Mohammadi-Yeganeh, S. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes enriched with miR-218 reduce the epithelial–mesenchymal transition and angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Eur J Med Res 2023;28:1–12, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01463-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes: a promising delivery system for glioma therapy

- Research Articles

- A multi-cancer analysis unveils ITGBL1 as a cancer prognostic molecule and a novel immunotherapy target

- MicroRNA-302a enhances 5-fluorouracil sensitivity in HepG2 cells by increasing AKT/ULK1-dependent autophagy-mediated apoptosis

- Integrated analysis of TCGA data identifies endoplasmic reticulum stress-related lncRNA signature in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Glioblastoma with PRMT5 gene upregulation is a key target for tumor cell regression

- BRCA mutation in Vietnamese prostate cancer patients: a mixed cross-sectional study and case series

- Microglia increase CEMIP expression and promote brain metastasis in breast cancer through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Integrative machine learning algorithms for developing a consensus RNA modification-based signature for guiding clinical decision-making in bladder cancer

- Transcriptome analysis of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs)-related genes reveals prognostic value and immunotherapeutic potential in cancer

- Prognostic value of a glycolysis and cholesterol synthesis related gene signature in osteosarcoma: implications for immune microenvironment and personalized treatment strategies

- Identification of potential biomarkers in follicular thyroid carcinoma: bioinformatics and immunohistochemical analyses

- Rapid Communication