Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to investigate the Canadian mainstream online media report of Huawei, the Chinese IT company and critical actor in China’s OFDI attempt, and how the media deviate or conform to the Government’s and the social and political elites’ position(s).

Design/methodology/approach

Content analysis and discourse analysis were performed to analyse the news articles from The Globe and Mail concerning Huawei from the beginning of 2018 to March 2019. Public opinions, represented by the Nanos polls available from the news articles were also analysed.

Findings

We found that Huawei was mainly framed as national security threat vs valued partner in the national debate whether to allow Huawei to contribute to Canada’s 5G construction before the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, and the centre of the Sino-West conflict after the critical incident. The Globe and Mail tried to index multiple sources, while sticking to the long-formed schema about China and Chinese enterprises, which has a deep effect on the public opinions. The journalists rose to be the predominant source of the news report and seemed to be acting on their own after the critical incident, showing an event-driven tendency.

Practical implications

It helps the readers to understand the bias embedded in media report in its political contexts. Journalists should take caution because they could reenforce the same schema even though efforts have been made to maintain media’s democratic façade.

Social implications

It shows that MNCs and international media have a much closer relationship than we expect. The media in the western world could make or break a MNC’s prospect in a country.

Originality/value

It contributes to the contextualization of such media theories as indexing hypothesis and cascading activation model. In an era of anti-globalization and media war, such theories need to be re-examined especially when it comes to the report about foreign affairs concerning a country and its MNCs from a different ideological camp.

1 Introduction

Decades of high-speed economic growth have wrought incredible changes in China and have also changed the relationship of China with the Western world. Chinese trade surpluses with many Western countries are quite large. While most of that advantage in trade is a result of the huge manufacturing industry and cheap labor, China seeks to reposition itself on the global economic stage and has been developing its high-tech industry. As part of this drive, many large and domestically successful corporations have expanded abroad. One such company, Huawei, is at the forefront of this trend. Its rapid expansion and technological expertise surprised its Western counterparts. By 2019 Huawei had deployed its products and services to over 170 countries (Huawei Official Website) and in the 3rd quarter of 2019 had captured 18.6 % of the global smartphone market (Statista.com). Huawei is also a leader in the development of 5G technology (Kania and Sheppard 2019).

Huawei’s operations in Canada provide an interesting case highlighting the intersection between international technology development cooperation and media reporting on these cooperative ventures. Huawei has operated in Canada since 2008 (Robertson and Castaldo 2018) and signed cooperative agreements with Canada’s telecommunication providers to build Canada’s next-generation 5G networks by 2019. While Canada had been testing the water with the prospect of accepting foreign direct investment (FDI) from China, the media have been very critical. Most countries tend to be very critical of foreign intervention in areas of national interest. This is particularly true when the investing nation is from another ideological camp. This clearly applies to Western media coverage of China. Media coverage carries with it decades of ideological, political and historical burdens which influence the writing and interpretation of China’s interaction with the Western world. Most coverage of China skews negative, with this trend evident in the US media (Chen and Gunster 2019), but also apparent in other countries such as Canada.

Both theoretical and empirical evidence indicates that media framing has a strong influence on public perceptions of other countries (Brewer et al. 2003; Kiousis and Wu 2008; Manheim and Albritton 1984; Wanta et al. 2004). In the case of FDI (foreign direct investment) from China, reporting following the standard critical line is more easily accepted and reporting diverging from this accepted stance is discounted. This has been confirmed in studies examining media coverage of China in both the United States and the United Kingdom (Chen and Gunster 2019).

However, while the United States government has taken an aggressive and primarily negative stance concerning its relationship with China, the Canadian government stance was comparatively ambiguous (Evans 2017). Until the week of May, 19, 2022, “Canada was the only member of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance – which also includes Australia, Britain, New Zealand and the United States – that had not yet banned or restricted the use of Huawei 5G mobile equipment” (Curry and Polsadzki 2022). In addition, few media framing studies have looked at Canadian media. This lack, coupled with the differing governmental policies, creates a unique situation we believe is well worth studying.

Our study looks at how Canada’s largest national daily newspaper, The Globe and Mail, framed Huawei in its published articles between January, 2018 and March, 2019. During this time a national debate was taking place over whether Huawei should be allowed to contribute to Canada’s 5G network construction. On Dec. 6th 2018, G & M first reported Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO, was arrested by Canada at the request of the US on their suspicion of her violation of the sanction against Iran. The Chinese embassy in Ottawa immediately strongly protested and demanded her release. Meng asked the court to grant her bail on December 10th. That same day, the Chinese government threatened serious consequences for Canada if it did not free Meng immediately. The following day, Meng was released on a $10,000,000 bail and China detained two Canadians, one of whom was a former diplomat. A third Canadian was detained later in the month although Trudeau indicated this was not related to the Meng arrest. This event led the China–Canada relationship to hit an all-time low. Hence, we would, in addition, compare how the media framed Huawei before and after this critical event.

2 Literature review

As a result of the indelible connection between Huawei’s proposed Canadian FDI and the Canadian foreign policy stance toward China, we find indexing hypothesis and cascading activation model provides relevant insight. Both the media and the public audience are often influenced by the government when it comes to foreign affairs and policies (Entman 2003).

First we review news framing in general and then specifically in the case of China. Second, we look at both the indexing hypothesis and the cascading activation model. Finally, we elaborate an event driven model will be explained to supplement the two theories.

2.1 The concept of framing and framing of China

News framing is the central organizing principle of news stories (Entman 1993; Gamson and Lasch 1983; Gamson and Modigliani 1989; Pan and Kosicki 1993). To frame is “to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (Entman 1993: 52). The media frame is “a central organizing idea for news content that supplies a context and suggests what the issue is through the use of selection, emphasis, exclusion, and elaboration” (Tankard 2001). When covering a news event, journalists decide which elements to include or exclude in a story. Therefore, a single news event can be framed in various ways, producing different versions containing different attributes. These frames then influence the audience’s understanding of news stories.

Entman (1991) stated that frames provide mentally stored principles for information processing, characteristics of the news text, and describe attributes of the news itself. He also pointed out that an “event-specific-schema” is an understanding of the reported event that “guides individuals’ interpretation of initial information and their processing of all succeeding information about it” (1991: 7). He concluded that the frame can make opposing information more difficult for the typical inexpert audience member to discern and employ in developing an independent interpretation. As a result, the media greatly influences the majority’s view of policy or politics. Similar ideas are echoed by other scholars (e.g., Saleem 2007) in the area of foreign affairs and policies. Since the audience typically does not have first-hand information about the issues being reported, it primarily relies on the media to provide details and event-specific-schema. Hence, the audience view is even more likely to be significantly shaped by the media when it comes to foreign affairs and other countries.

When looking specifically at China, research general finds that, notwithstanding China’s tremendous economic growth, the Western media still frame China as “a country characterized by low wages, heavy pollution, political repression, human rights abuses, decaying social services, and social unrest” (Chen and Gunser 2019: 3; Goodrum et al. 2011; Ooi and D’arcangelis 2017; Tilt and Xiao 2010). Stravo (2014: 172) adds that Western media characterizes the Chinese as “secretive, unreliable, and authoritarian – bad global citizens”. Chen and Gunster (2019) noted that this trend is especially evident in the U.S. media. Lams (2016) writes that this is also true in European media reporting on China as in Belgium and the Netherlands media reporting is also consistently negative. In fact, “China is consistently portrayed by the [SIC] Western media with frames that focus on human rights, political containment, and economic trade” (Willnat and Luo 2011: 259).

As indicated above, Western media reporting tends to focus on the Chinese government (Huang and Leung 2006; Lams 2016) and hence is heavily event-driven and context dependent (De Swert and Wouters 2011; Lams 2016). In global television news, for instance, the representation of China is unidimensional with little attention given to cultural and social achievements (Willnat and Luo 2011). In the European transnational media, the rise of China is discussed primarily in economic, trade, finance and business reports, and caution is expressed with respect to the country’s rising global status (Zhang 2010). Goodrum et al.’s (2011) comparison of China-related news at national and local levels found that while the national Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) focuses on negative political stories concerning China, the Toronto Star and the Chinese language newspaper Ming Pao publish business- and culture related stories, thereby presenting a more comprehensive picture of China.

Chen and Gunster (2019) studied the representation of China by Canada’s alternative media, focusing on report on energy and environmental issues in the province of British Columbia. They found that China’s image within British Columbia’s alternative public sphere is characterized by the tension between two conflicting images – a negative frame of a powerful, foreign entity that unduly influences Canada’s economic policies and a positive frame as a global leader in renewable energy and, increasingly, in global climate negotiations. Nevertheless, the negative image was significantly more prominent than the positive one. They argued that readers of these news sources would view the Chinese government as a fearful foreign power aggressively expanding its influence in Canada. In many respects, such representations echo the anti-China and anti-communism rhetoric in the mainstream media. Goodrum et al. (2011) studied Canadian media at national, local and hyper-local levels and found that although China has a great economic impact on Canada, it was covered only as a marginal content in the Canadian international news mix. They concluded that in most cases, the coverage served to reinforce Canadian national identity and depicted China in a negative manner.

Coverage of Chinese enterprises has also been predominantly negative (Zhang et al. 2015). This is especially the case in the current environment of increased anti-globalization and protectionism (Chazan 2017; Mullen 2017; Stratmann 2017). The strained Sino-US relationship spills over and influences media coverage and will probably do so for the foreseeable future, especially during a firm’s initial establishment phase in Western markets. This striking contrast between the fast advancement of Chinese firms’ overseas operations and the negative Western media reports about China and Chinese firms certainly deserves increased academic attention (Fang and Chimenson 2017).

We strongly support this call for increased academic scrutiny and believe it is particularly applicable to the understanding of media coverage of Huawei’s international expansion. We focus on the Canadian mainstream national media report and predict that the tone would be largely negative, given the fact that Canada’s influential southern neighbor, the United States, has taken an antagonistic stance to China in general and to Huawei in particular. We are also interested, however, in the Canadian government’s reaction to Huawei’s operations and how the media and the stated government positions differ. In addition, we will look at Canada’s non-administration elites and the popular public opinion. According to Entman’s (2003) cascading activation model, all four elements (the government, other social and political elites, the media and the public opinion) play a role in the public sphere when it comes to foreign policy issues, with the elites wielding the most power. Hence, it would be relevant to look at all these players’ attitudes and views towards Huawei through the lenses of the media, whose frames are readily available for scrutiny.

2.2 Indexing hypothesis and the cascading activation model

According to Althaus et al. (1996), indexing hypothesis provides valuable insight for understanding media foreign policy coverage in democratic countries. Journalists seek to maintain balance by reporting opposing ideas as well as official governmental positions. While the press reports governmental information regarding policy stances and decision, the press is also supposed to be a guarantee for democracy and thus has an obligation to investigate governmental policies and to provide a platform for public debate. The press is supposed to strike a balance between these two requirements in its news reporting. As a result, in both news coverage and editorials, news professionals ‘index’ a wide range of viewpoints on issues which percolate in the news (Bennett 1990).

Hence, “indexing hypothesis applies most centrally to the question of how the range of positive, legitimate, or otherwise ‘credible’ news sources is established by journalists” (Bennett 1990: 107). Arguably, prestigious national news organizations carry more influence in this indexing process. Bennett (1990: 122) adds that the indexing process might be expected to operate most consistently in covering the issues of “military decisions, foreign affairs, trade and macroeconomic policy”. In the case of Huawei, Canada’s foreign policy was ambiguous. At the same time, many other sources have voiced their views. Ideally, the media’s role is to candidly report this national debate and index all voices from different sources, although, in reality, it often favors certain sides over others. Under this assumption, we expect that frames in Huawei reporting would be distributed along both positive and negative sides, with some emphasis on the negative given the findings from previous studies and the media traditions.

Entman (2003) builds on the indexing hypothesis to propose the cascading activation model, which states that newsworthy ideas typically flow from the government to other political elite, then the news media pick up them and quickly pass them on to the public. While this process can be reversed, when that occurs, it takes much more energy due to the layered structure of the cascading. In spreading ideas from the public up to where they influence the thinking of elites and governmental officials, the main road is again through the media. Entman (2003) added that at all levels of the process there are mixed motives, varying level of competence, and a great degree of uncertainty and pressure. The public is not always a passive receiver and can, on occasion, influence its construction through the media, reversing the flow of the cascading activation.

Entman (2003) argues that when it comes to foreign affairs and policies, the public will most likely rely on the media to tell them what to think and how to act because the media is mostly likely their only source of information. However, in today’s new media era, the public have more sources of information on foreign affairs and policies, and thus have more power to perform the “pumping effect” to reverse the cascading. Still, Ha et al. (2022) compared the U.S. and Chinese news media on the trade war between the two countries and found that the cascading activation model can be applied to both the U.S. and Chinese news media. They concluded that in international conflicts, the influence of the government on the news media, including both the traditional and new media they investigated, irrespective of their political tendencies, is stronger because national interests can unite the government and the news media. The media rely on their national government as the main source of news.

In the case of Huawei, it is still not clear which of these influences is more significant. Does the Canada administration have a significant influence on the media and resulting public opinion, or do the three entities (administration, elites and the media) work hand in hand to strengthen each other? In addition, how do foreign sources influence the dynamic of the cascading? When the media expresses concern about government policies it may turn to foreign sources for support (Althaus et al. 1996). In this case, the media finds ample support due to the US government’s decision to ban Huawei involvement in 5G network development in the US and its pressure on the Canadian government to do the same.

Both the indexing hypothesis and the cascading model were derived in the context of the US media, but they have also been applied in other countries’ media contexts even though scarcely. For example, Valenzano (2009) used the model to study Canadian newspapers’ report of the US foreign policy over the war on terror. Smith et al. (2010) adopted the model to study both the US and the world media outlets on the financial crisis. So did Justus and Hess (2006) who applied the model in the US and the world media outlets to study the death of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in the war on terror.

Because we are interested in whether cascading activation model can be applied in media contexts other than the US and specifically in our case, we propose a hypothesis based on the theory as follow: The newspaper’s main frames of Huawei will be mostly from government officials and other political and social elites. We expect that our findings would contribute to test and enrich the theories.

2.3 An event driven model

Although both the indexing hypothesis and the cascading activation model provide significant insight, some scholars argue that they are too centered on the influence of elites. They add that dramatic events may undermine official narratives, influence news coverage and therefore must also be considered (e.g., Baum and Groeling 2009; Bennett and Lawrence 1995; Lawrence 2000; Wolfsfeld 1997). Thus, while they accept the influence of political elites on coverage, dramatic events may shape the way that the news media cover issues and thus potentially disrupt the control of political elites. Such events are non-routine, affect a large number of people, and involve conflict, all qualities that resonate with journalists’ perceptions of newsworthiness (Lawrence 2000; Oliver and Myers 1999).

Dramatic events provide “news icons,” vivid images or descriptions that “evoke larger cultural themes” (Bennett and Lawrence 1995: 22), which then shape the media’s presentation of subsequent events. Wolfsfeld (1997) goes even further, arguing that unexpected events can disrupt the control of political elites and provide opportunities for less powerful groups to shape media framing. Such events may serve to illustrate or strengthen the claims of less powerful groups and thus spur journalists to include their frames in news coverage (Wolfsfeld 1997: 45).

Studies have been carried out on the influence of such dramatic events on media coverage and framing. Speer (2017) carried out a content analysis study comparing New York Times coverage of the Iraq war before and after the Samarra bombing. His findings suggested that dramatic events encourage journalists to promote particular frames over others rather than simply mirroring official viewpoints. He concluded that his findings provided support both for Entman’s (2004) ‘cascading activation model’ and a more event-driven model of news coverage (e.g., Lawrence 2000). However, his findings did not refute the indexing hypothesis but suggested “a more nuanced version of it would be more appropriate, because coverage was not tightly indexed to the range of views amongst officials” (Lawrence 2000: 298).

Lams (2016: 154) argues, “Deconstructing the framing process is a way to resist stereotypical imaginaries of fixed identities in terms of us/them polarities, imaginaries of fear and conflict and manipulation of simplistic ideas.” We want to know how the Canadian media frames Huawei, a giant IT company from China, and deconstruct the framing process by not only presenting the statistical results but also analyzing the actual text.

Hence, the following research questions are proposed:

RQ1:

What frames and tones (based on the frames) in general (positive or negative) were adopted in Canadian media’s coverage of Huawei during the selected time frame?

RQ2:

How did the Canadian media coverage of Huawei reflect the attitudes and view of government officials, other political and social elites, and others?

RQ3:

How did frames and sources differ before and after the arrest of Meng Wanzhou?

3 Methods

Content analysis is a systematic, replicable technique for compressing many words of text into fewer content categories based on explicit rules of coding (Krippendorff 1980; Weber 1990). As a result, it is a useful technique which allows us to discover and describe the focus of individual, group, institutional, or social attention (Weber 1990). This technique has often been used to analyze data from mass media. We used content and discourse analysis to achieve the purpose of this study. First, we identified and coded all articles concerning Huawei in our sample timeframe. Statistical analysis revealed frequency of coded frames and sources as well as correlations between frames and sources. Finally, discourse analysis was conducted on select typical articles. Examples from these articles are quoted below to help explain the major frames.

3.1 Data

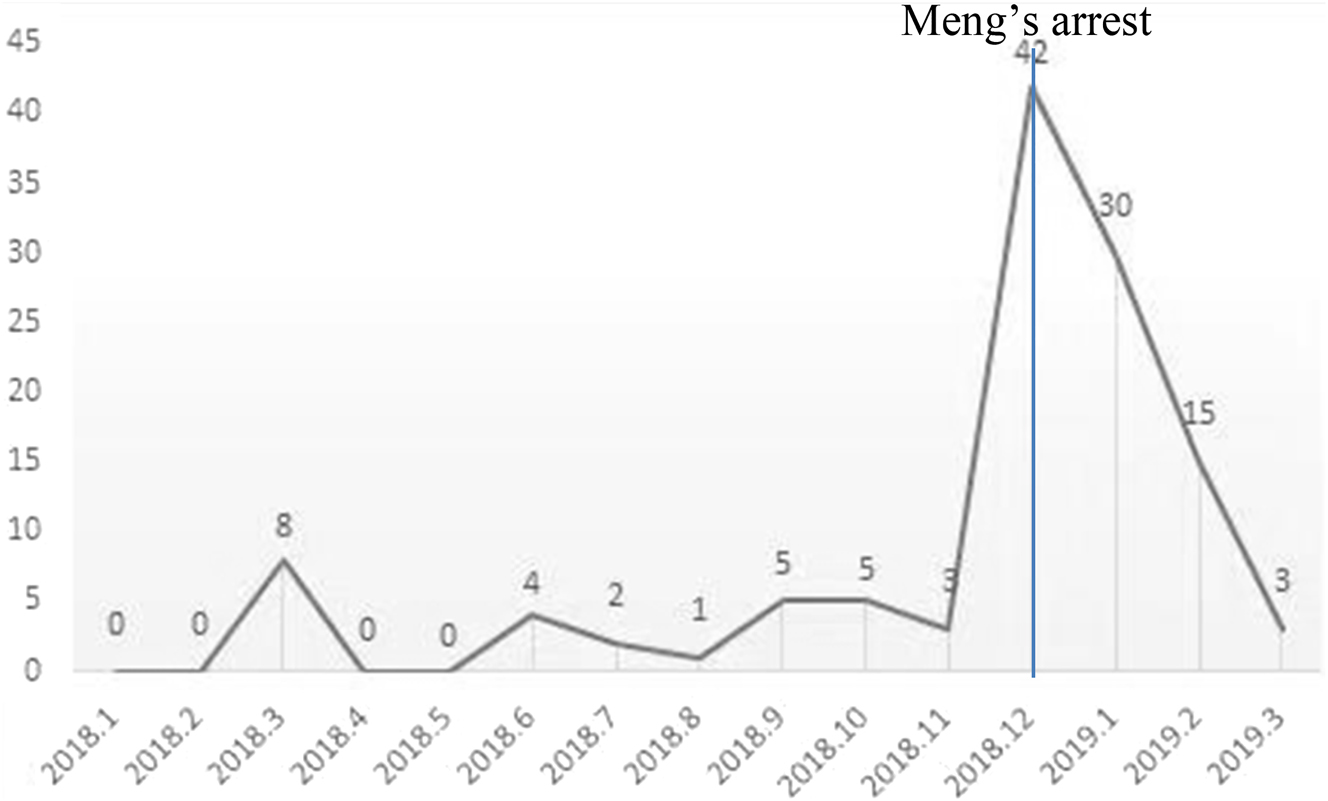

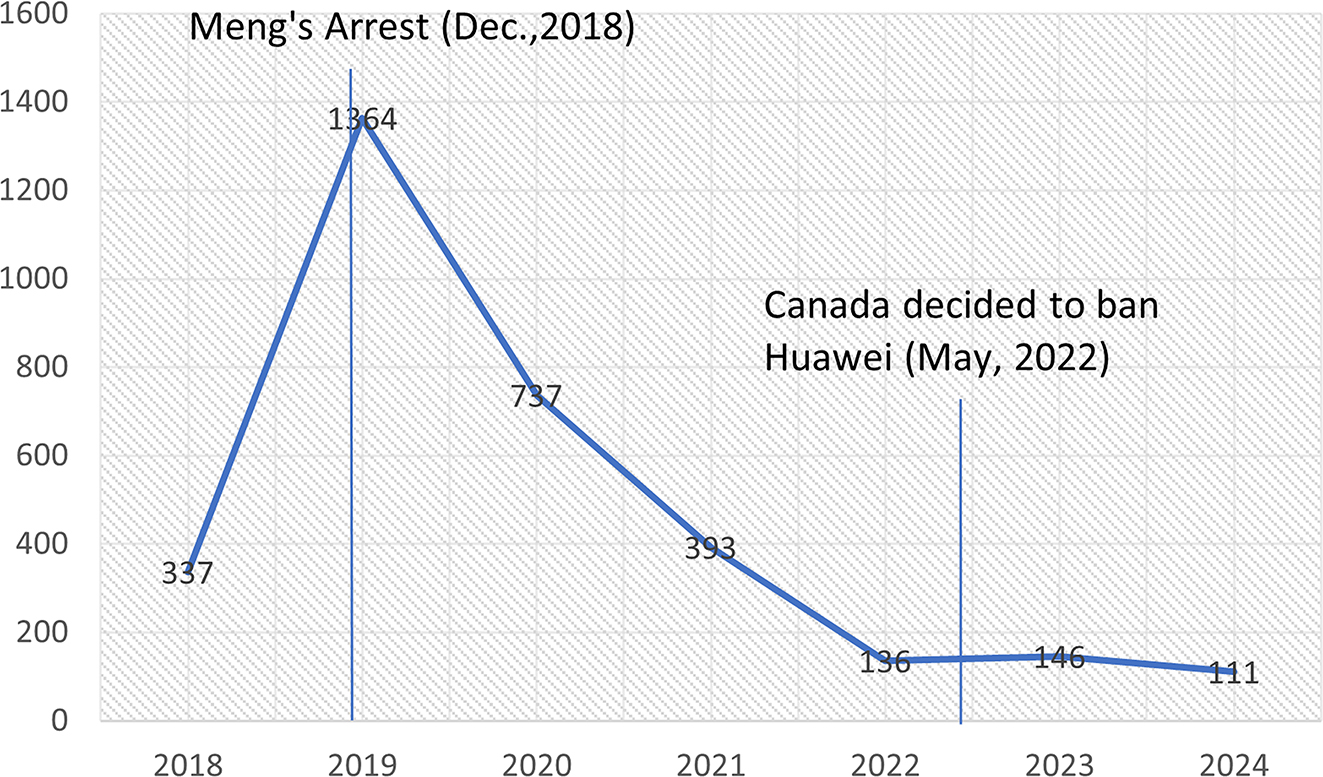

We chose The Globe and Mail (called The G & M hereinafter) as our major data source because it is the most influential national newspaper in Canada, thus fitting one of the conditions of the indexing hypothesis. The Globe and Mail has a weekly readership of 6 million in 2024 and is Canada’s most read newspaper on weekdays and Saturdays. It is regarded by some as Canada’s “newspaper of record”[1] (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2009). 332 articles containing the word “Huawei” were found on the official The G & M website between the date of Jan. 1st, 2018 and the date of March 30th, 2019. These articles include news articles, opinion articles, editor’s letters, and readers’ letters. Then, we found that there were only 53 items containing the word “Huawei” before Dec. 6th, 2018, the day when The G & M reported the arrest of Meng Wanzhou by Canadian government, and 279 articles turned up between Dec. 6th, 2018, the report of the arrest of Meng Wanzhou and March 30th, 2019, the end of our sampled period. The authors then read all the articles of the sample period in order to filter out those whose main topics were unrelated to Huawei but merely mentioned Huawei peripherally. We also filtered out editor and reader letters. Our final sample of 118 articles were news reports. Twenty-eight were from before the arrest of Meng Wanzhou and 90 were published after the arrest. The trend of frequency of the filtered Huawei news articles during the 15 months’ period on a monthly basis is shown in Figure 1. The trend of frequency of the unfiltered news article on Huawei by year from 2018 to 2024 is shown in Figure 2. Both trends show that the media’s interest in Huawei peaked in 2019 when the 5G debate was heated and when Meng Wanzhou was arrested.

Selected Huawei news article frequency by month during the sample period.

Unfiltered Huawei news article frequency by year from 2018 to 2024.

3.1.1 Coding scheme

The authors read all 118 articles in order to understand their main topics. They found that during the time frame sampled, Huawei was at the center of a national debate on whether Huawei should be the primary contractor for Canada’s 5G technology development. In these articles, reasons both supporting and against Huawei’s participation were present in the articles. Thus, Huawei was often portrayed with multiple image layers constructed by the media and it was difficult to distinguish the main frame of image construction from the minor frames. As a result, since we wanted to record all the layers of image of Huawei in Globe and Mail’s reports, we decided not to distinguish between main and minor frames. All writing (i.e., words, phrases and sentences) constructing the image of Huawei were recorded and meanings were interpreted in the context of the whole article. Then, all the identified themes were collapsed into categories which were further paraphrased into frames which were used to portray Huawei. Altogether, six frames were identified in this process. In order to define these frames, the authors recorded example words, phrases and sentences quoted or paraphrased from the articles for each frame. This coding scheme serves as a guideline for coders to follow while coding all the articles in our article pool. Since we are also interested in the sources of the frames, we added source codes to our coding scheme (see Tables 1 and 2).

Acronyms and their representation.

| Acronym of the frame/source | Full name of the frame/source |

|---|---|

| NST | Huawei is a national security threat to Canada. |

| IPP | Huawei’s aim is to pursue intellectual property. |

| ACD | Huawei is the agent of China dominance of the world. |

| VP | Huawei is our valued partner. |

| PC | Huawei is the pride of China. |

| CC | Huawei is the center of conflict. |

| CG | Canadian government |

| CSE | Canada’s social and political elites |

| AGO | American government officials |

| JOUR | Journalists |

| HM | Huawei management |

| ChGO | Chinese government officials |

| OtherS | Other sources |

3.1.2 Coding

Three graduate students in business English studies were trained to code the articles. They were told to find all the frames constructing the image of Huawei and their corresponding sources and fill out the coding sheet for each article. The themes should be interpreted in the context of the whole article.

In order to improve inter-coder reliability, we did three rounds of test coding with all three coders. In each round of test coding, we randomly selected articles from the article pool, deducting the selected articles from the previous round(s) in the second and the third rounds. If the coders found accounts, comments or description about Huawei that did not fit in any of the coding frames, they were asked to mark this material and to bring it to the training session. In each session, all three coders and one of the authors would discuss any codes where there was disagreement as well as potential new themes which did not fit in any of the existing frames. The author who carried out the training made the final coding decisions. Hence the coding scheme underwent several iterations until there was agreement among coders and no new themes or sources were identified. The inter-coder reliability reached 86.6 % agreement among three coders in the last round.

After the training was completed, the remaining articles were divided into three groups and each coder coded one group of articles independently. At the end, all the coding sheets were put together and keyed into an excel file. Scores of frames and sources were calculated. The results are shown in Tables 3 and 4 in the section of Result.

Coding scheme.

| Frames | Sub-frames and examples |

|---|---|

| 1. National Security Threat (NST) | A) Huawei’s identity (e.g., Agent of Chinese ruling party and close relation with Chinese authorities) |

| B) Ariticle 7 of China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law | |

| C) Conduct espionage activities in host country | |

| D) Western allies’ banning and warning | |

| E) Canadian authorities carried out investigation | |

| F) Cyber intelligence threat | |

| G) Surveillance capability | |

| 2. Intellectual Property Pursuer (IPP) | A) Cooperation with Canadian universities |

| B) Canadian taxpayers’ money used to support Chinese company | |

| C) Seeking technology and know-how from western companies | |

| D) Law breaking | |

| 3. Agent of Chinese Dominance (ACD) | A) China buying political influence |

| B) Unfair market player | |

| C) Prevent the growth of Canada’s own telecommunication industry | |

| D)A global telecom superpower | |

| D) Disruptive to economic landscape of Canada | |

| 4. Valued Partner (VP) | A) Leading giant in global 5G market |

| B) Provider of less costly network equipment | |

| C) Already cooperating with Canadian tele companies | |

| D) Support R&D in host country | |

| E) Law-abiding, and never a problem | |

| F) Good relationship with many countries globally | |

| G) Entered Canadian market for over 10 years, funding lots of activities | |

| H) Help Canada to build strategic relationship with China | |

| I) Huawei’s 5G security threat is exaggerated, and can be controlled | |

| 5. Pride of China (PC) | A) China’s most prominent corporate success/biggest private company/corporate jewel |

| B) Flagship of Chinese MNEs, and spearhead of China’s “go abroad” policy | |

| C) China’s tech giant, representing China’s rise in global telecom industry | |

| D) Innovation powerhouse | |

| E) Corporate culture | |

| 6. Center of Sino-West Conflict (CC) | A) Triangle tensions among Canada-China-US |

| B) Breaking the US sanction against Iran | |

| C) Scapegoat of US strategies to constrain China | |

| D) The new cold war | |

| E) Target of western strike/unfair treatment | |

| 7. Others |

| Frame sources | |

|---|---|

| A) Canadian Government officials (CG) | |

| B) Canadian social elite (CSE) | |

| C) American government officials or social elite (AGO) | |

| D) Journalist (JOUR) | |

| E) Huawei management (HM) | |

| F) Chinese government officials or scholars (ChGO) | |

| G) Others |

Distribution of frequency of frames.

| NST | IPP | ACD | VP | PC | CC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the arrest | 100 % | 14.29 % | 10.71 % | 50 % | 0 % | 0 % |

| After the arrest | 73.86 % | 13.64 % | 10.23 % | 31.82 % | 13.64 % | 65.91 % |

| Total | 80.17 % | 13.79 % | 10.34 % | 36.21 % | 10.34 % | 50 % |

-

Since an article may include more than one frame, numbers will total to more than 100 %.

Distribution of frequency of frame sources.

| Source | CG | CSE | AGO | JOUR | HM | ChGO | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 46.43 % | 46.43 % | 67.86 % | 53.57 % | 32.14 % | 0 % | 10.71 % |

| After | 22.72 % | 20.45 % | 27.27 % | 90.91 % | 14.77 % | 10.23 % | 12.50 % |

| Total | 28.45 % | 26.72 % | 37.07 % | 81.90 % | 18.97 % | 7.76 % | 12.07 % |

-

Since more than one source is often cited in an article, numbers will total more than 100 %.

3.2 Discourse analysis

Discourse, in general terms, refers to actual practices of talking and writing (Woodilla 1998). Discourse analysis explores the relationships between a text, its production and the context in which it is produced (Philips and Hardy 2002) and is a natural for the purposes of our study. We use discourse analysis to examine the Huawei frames in The G & M articles. We look at the content of the frames, how certain frames are emphasized over other frames, the positive or negative tone of the frames, the socio-cultural implications associated with the frames, and the potential impact they may have on their readers. Specifically, we tried to look at how the journalists use language to inform the public opinion on the national debate whether Huawei should be accepted as a major contractor in Canada’s 5G technology development. Both micro-level (e.g., linguistic features) and macro-level (e.g., meanings and underlying assumptions) were analyzed. Examples of representative adaptations are given to explain the major frames. In doing so, we provide a detailed understanding of the media discourse that constructed the frames of Huawei which supplements the initial content analysis.

4 Result and analysis

Huawei became a significant Canadian news topic primarily due to the national debate about its potential contribution to Canada’s 5G infrastructure. Hence, we expected that most of the news articles should feature both sides of the story, indexing a variety of views from Canadian government, other social and political elites, as well as other sources. We did not distinguish between major and minor frames, but instead identified and coded all frames found in the sampled articles.

4.1 Frequencies of frames before and after the critical event

Research question one asked what frames and tones in general (positive or negative) were adopted in Canadian media’s coverage of Huawei during the selected timeframe. Analysis of the 118 selected articles in The G & M identified frames – National Security Threat (NST), Intellectual Property Seeker (IPS), Agent of China Dominance (ACD), Valued Partner (VP), Pride of China (PC), and Center of the Sino-West conflict (CC). From frequency analysis, our result shows that the main frames are NST (>80 %), CC (=50 %), and VP (>36 %). Table 3 summaries how often these frames appear over the entire time frame sampled as well as before and after the critical event. All of these frames take a negative to neutral view of Huawei’s influence in Canada except for one – the Valued Partner frame.

Research question two asked how the Canadian media coverage of Huawei reflect the attitudes and view of government officials and those of other political and social elites. We coded all sources that the journalists quoted in the articles. Seven source categories were identified: Canadian government officials (CGO), other Canadian social and political elites (CSE), American government officials (AGO), journalists (JOUR), Huawei Management (HM), Chinese government officials (ChGO), and other sources (OtherS). Table 4 presents the total source frequency as well as source frequency before and after the arrest.

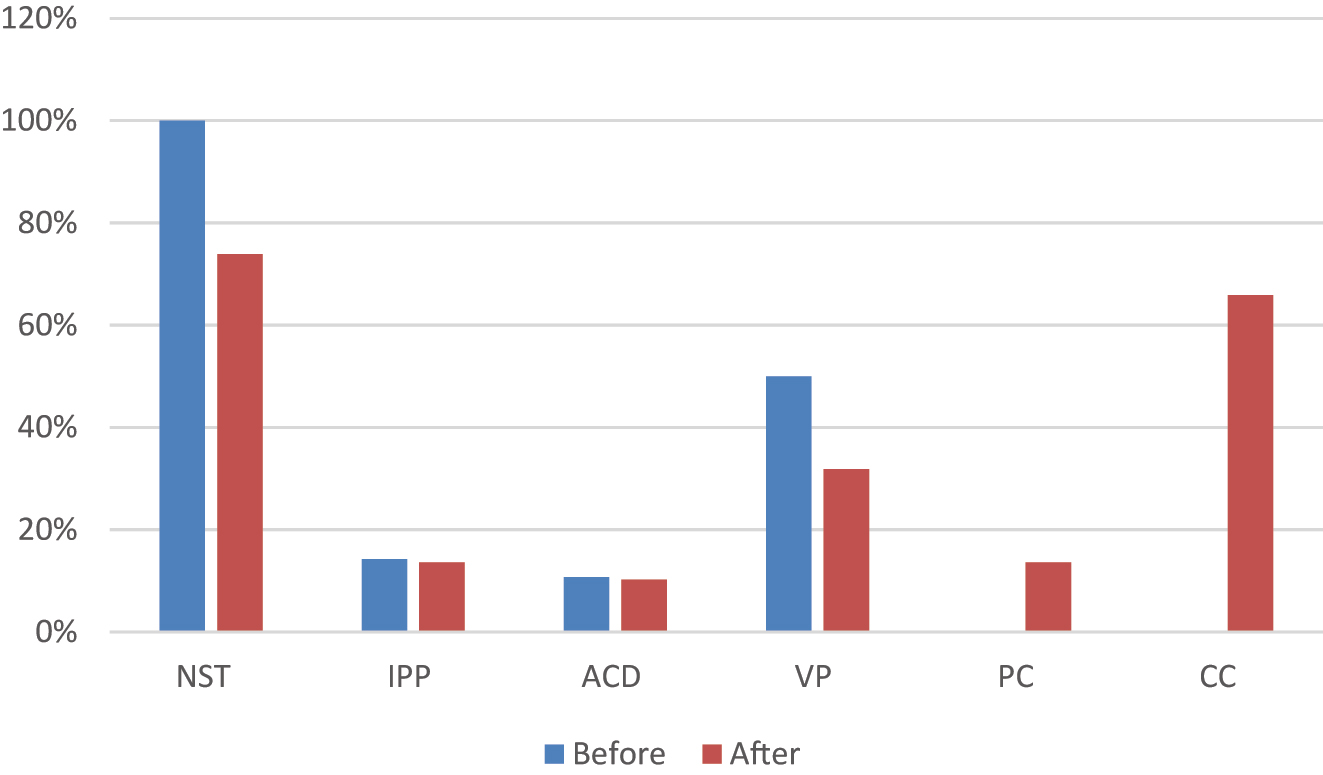

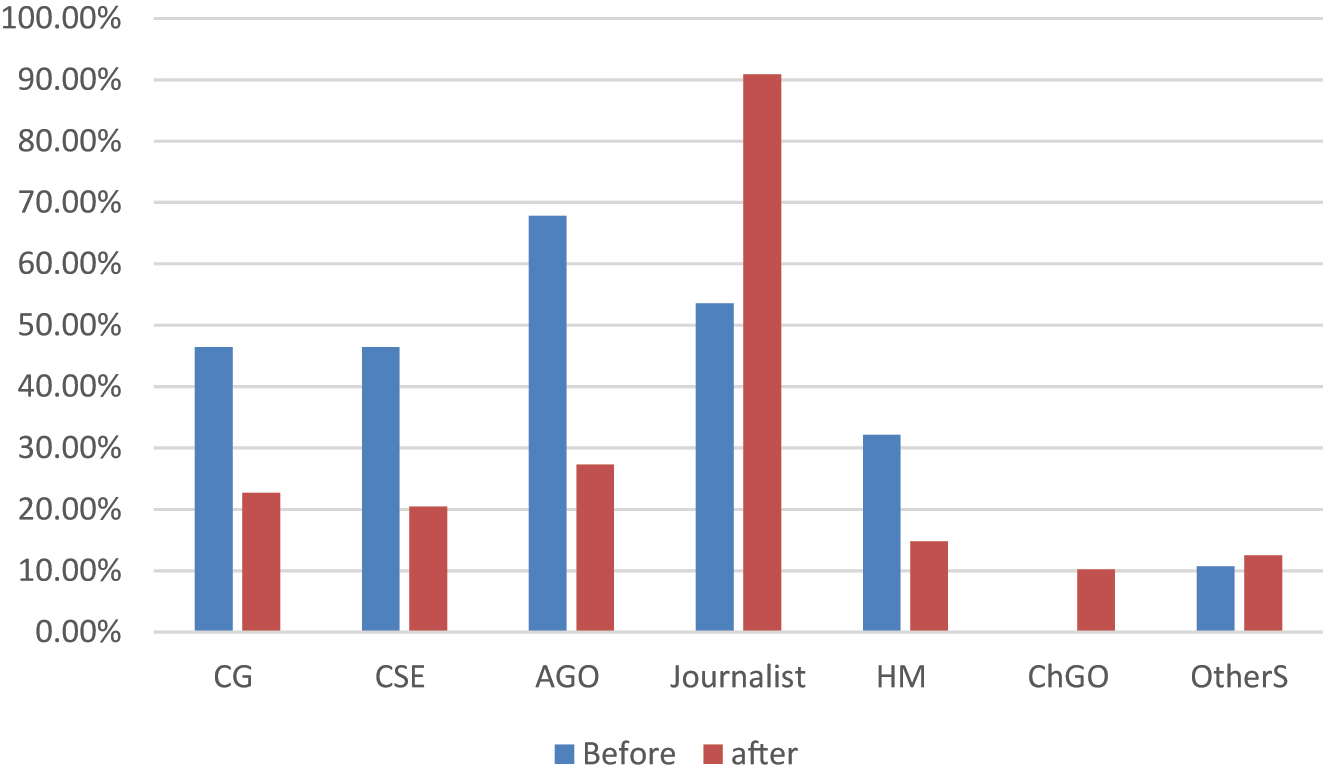

Research question three asked how the critical event of the arrest of Meng Wanzhou influenced Huawei news reports. Significant changes were found in both framing and news sources as indicated in Tables 3 and 4. The following bar charts (Figures 3 and 4) helps to compare the frequency of frames and sources before and after the arrest.

Comparing the frequency of frames before and after the arrest.

Comparing the frequency of frame sources before and after the arrest.

Two frames – “Pride of China” and “Center of Sino-West Conflict” – increased after the critical event of the arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer. The frames of “National Security Threat” and “Valued Partner” declined almost 20 %. The frames of “Intellectual Property Seeker” and “Agent of Chinese Dominance” remained almost unchanged. Before the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, four sources including Canadian government, Canadian social and political elites, American government officials, and The G & M Journalists are the most quoted sources. After the event, the G & M journalist source rose significantly to be found in 90.91 % of the articles while the rest three sources decreased significantly. Chinese government officials started to be cited in 10.23 % of the articles after the critical event. The Other Source category grew slightly to be found in 12.5 % of the articles (Table 4).

To summarize, we used frequency of codes to answer research questions one, two and three. The frames G & M adopted were predominately negative when talking about Huawei with “National Security Threat” being the most frequently adopted frame throughout the sample period we selected. Journalists were the predominant source in total during the whole sample period, although there were significant differences before and after the critical event. Finally, both frames and sources differ before and after the arrest of Meng Wanzhou. The major frames before the Meng Wanzhou incident are “National Security Threat” and “Valued Partner.” After the arrest, while “National Security Threat” remained the most frequent, the frame “Center of Sino-West Conflict” rose to be prominent as well. Comparing before and after the Meng Wanzhou event, journalists rose sharply from 53.57 % to 90.91 %. Although the American government officials (67.86 %) were the most cited sources before the Meng Wanzhou incident among all the sources identified, they dropped sharply after the incident (27.27 %). Both Canadian government officials (46.43 %) as well as Canadian social and political elites (46.43 %) were important sources for GM’s Huawei articles before the incident but reliance on these sources dropped after the incident (22.72 % and 20.45 %). Both Huawei management (18.97 %) and Chinese government officials (7.76 %) were minor sources during the sampled period in total, with Huawei management being somewhat important before the incident (32.14 %). The Chinese government was not quoted before the arrest and was only in 10.23 % of the articles after the arrest.

Our preliminary analysis of the number of articles concerning Huawei during the sampled periods (see Table 3) shows that there were infrequent direct reports about Huawei before Meng’s arrest. These reports mainly centered on the national debate about whether Huawei should be allowed to participate in Canada’s 5G infrastructure construction. Immediately after the event, the quantity of reports concerning Huawei skyrocketed. Most of these articles focused either on the event itself or on the strained relationship among China, the US and Canada because of the arrest. These articles framed Huawei as the Center of Sino-West Conflict. This frame was present even in articles which did not primarily focus on Huawei as a critical element which contributed to the Sino-West conflict.

4.2 The relationship between frames and sources

The debate over Huawei led to most articles containing multiple frames as journalists sought to index opposing views. We coded all frames identified in each article. Similarly, we identified all the sources quoted to create these frames. We present correlations between sources and frames (Table 5). Note that correlation between frames and sources does not signify that certain source tended to provide certain frame(s), but rather that they tended to appear together. Frames do not have a one-on-one correspondence to the sources identified in a single article. Frames that are positively correlated, however, indicates that they are either connected at a significant level by their connotation or that they are the counter-arguments of each other and thus generally appeared as a pair.

Significant correlations between frames and sources.

| NST | IPP | VP | CC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACD | – | 0.19a | – | – |

| VP | 0.29b | – | – | – |

| CC | −0.32b | – | −0.47b | – |

| CGO | 0.31b | – | 0.32b | −0.21a |

| CSE | – | – | 0.40b | −0.33b |

| AGO | 0.25b | – | 0.20a | −0.20a |

| JOUR | – | 0.19a | – | 0.29b |

| HM | 0.24b | – | 0.64b | −0.31b |

| CHGO | −0.26b | – | – | 0.29b |

| OtherS | – | – | 0.22a | – |

- a

p<0.05

- b

p<0.01

NST is positively correlated with the sources of Canadian government officials (p = 0.01), American government officials (p = 0.01) and Huawei Management (p = 0.01). VP is positively correlated with the sources of Canadian government officials (p = 0.01), other social and political elites (p = 0.01), Huawei Management (p = 0.01), and American government officials (p = 0.05). CC is positively correlated with the sources of journalists (p = 0.01) and Chinese government officials (p = 0.01).

Huawei management was quoted to claim that Huawei is a valued and long-term partner (VP frame) of Canada as a counter argument against the NST frame often associated with American government officials and Canadian government officials, and the two frames are indeed highly correlated with each other. However, VP frame appeared in only 36.21 % of the articles while NST frame appeared in 80.12 % of the articles, which indicates that the latter is the dominant frame and the tone of all the sampled articles is generally negative.

The G & M journalists reported the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO, and the cause of the event. That Huawei became the center of the conflict between China and the West, especially the U.S., appeared in 65.91 % of the articles published after the event. Chinese government officials were given voices even though only appeared in 10.23 % of the articles published after the event. The journalists framed Huawei as the pride of China (PC frame) to explain why the Chinese government reacted so strongly, not only criticizing and threatening but also retaliating the Canadian government by detaining two Canadians in China.

The topics covered after the critical event of Meng’s arrest were diverse and include Canada’s foreign policy towards China, business between China and Canada, Sino-US relations and trade talks, as well as the FVEY intelligence alliance’s (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States) attitudes and actions towards Huawei. The number of Huawei frames used by The G & M also increased compared with the frames before the arrest. The old frames of National Security Threat, Valued Partner, Intellectual Property Pursuer and Agent of China Dominance were joined by the new frames of Center of Sino-West Conflict and the Pride of China. This increase in frames indicates the Event-driven model may be the best fitting model to explain the changes that happened after the arrest.

Journalists focused on analysing the situation as a result of the arrest of Meng Wanzhou and quoted more diverse sources. In this case, the journalists themselves became the most prominent source, appearing in about 91 % of the articles after the arrest. This stands in contrast to their appearance as a source in 54 % of the articles before the arrest. The NST frame, although decreased from before the arrest, still exist in about 74 % of the articles published after the arrest. A new frame of Center of Sino-West Conflict, rose to appear in about 66 % of the sampled articles after the arrest to focus on the international relations. To conclude, more factors were taken into consideration in this national debate whether Huawei should be banned from contributing to Canada’s 5G construction. Discussions were focused on the relational consequences which Canada needs to face and what foreign policies and business strategies Canada needs to take after the arrest was carried out.

4.3 Evidence from discourse analysis supporting major frames

Numbers are cold and impersonal and often oversimplify the data. Therefore, we looked at actual texts of the sampled news articles, using discourse analysis to interpret the texts given the socio-cultural context in which they were written and to identify how frames were constructed and how some were more prominent than others. We focused on the two frames with the highest frequency counts before the critical event: National Security Threat and Valued Partner. Excerpts from the text were presented to make a point.

4.3.1 National security threat

The following paragraph is the beginning of an article titled “Ottawa warned to sever links with China’s Huawei; Security experts say federal government should act on U.S. concerns about using telecom giant’s next-generation 5G technology”, written by Roert Fife (Staff) and published on March 19, 2018 in News page: ‘Three former directors of Canada’s key national security agencies are urging the federal government to heed the warnings of U.S. intelligence services and cut Canadian ties with Huawei, the giant Chinese smartphone and telecom equipment maker.’ This is a very powerful statement. First, two types of sources are quoted in this short paragraph, former directors of Canada’s key national security agencies and U.S. intelligence services. Both are relevant sources concerning the topic in question. The former belongs to the Canadian social and political elites and can be positioned at the upper tiers of the cascading activation model. Even though the source of the U.S. intelligence services is foreign and not technically embodied in the cascading activation model, given the historically close alliance, geographical location and similar ideological view shared by both countries, it is an influential source of information for the Canadian media. Both sources were related to a strong unambiguous and direct warning that Canada should cut ties with Huawei.

After convincing arguments were provided in the first three paragraphs, the government’s attitude and view were provided in a single sentence paragraph, “Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale told The Globe and Mail in a statement on Friday that Huawei is being monitored and does not pose a risk to Canada’s cybersecurity.” The government official, the first tier of the cascade activation model, is clear about their attitude towards Huawei because he assured the public that “Huawei is being monitored” and the result is that it “does not pose a cybersecurity threat”.

The next paragraphs immediately started with a “But” as a transitional word for the following paragraph:

But Mr. Elcock, a former CSIS director, deputy minister of National Defence, and Security and Intelligence Deputy Clerk of the Privy Council, said he shares U.S. concerns about Huawei, which was founded by a former engineer in the People’s Liberation Army and has been accused of acting as an arm of Beijing.

Then, the following lengthy quote from Mr. Elcock:

I have a pretty good idea of how signal-intelligence agencies work and the rules under which they work and their various operations and … I would not want to see Huawei equipment being incorporated into a 5G network in Canada,’ Mr. Elcock told The Globe. Signals intelligence is the monitoring and interception of predominantly foreign communications by national security agencies.

This source – “a former CSIS director, deputy minister of National Defence, and Security and Intelligence Deputy Clerk of the Privy Council” – belongs to the first tier in the cascading activation model. He shared that Huawei “was founded by a former engineer in the People’s Liberation Army” and “is accused of acting as an arm of Beijing.” These phrases are meaning- and value-laden. Then, the quote contains technical jargon such as “signal-intelligence agencies,” with Mr. Elcock claiming expertise in this area and thus presented as a relevant and persuasive figure. His attitude is clearly negative as shown in the comment: “I would not want to see Huawei equipment being incorporated into 5G network in Canada.”

The cascading activation model puts the government at the highest level of influence. In this case, although the government lukewarmly provides an argument supporting Huawei, much more space is given to providing information supporting the negative side. This aligns with the indexing hypothesis, which predicts that the media will report arguments opposite to the government’s opinions, or report both sides if there is a split of opinions within the government. However, Entman (2003) also noted that the media may favor one side of an argument dependent upon factors such as the influence of long-formed schemas, mental maps and motivation. The newspaper clearly took a stance on the side of non-administration elites and US officials. The overall tone of the article is strongly negative towards Huawei, framing the company as a National Security Threat. The next frame discussed is the only positive frame used by the media during the sampled period and mainly served as a counter argument to the NST frame reported above.

4.3.2 Valued partner

In the same article, towards the end of the passage, Scott Bradley, Huawei Canada’s vice-president, is quoted, “Huawei Canada vice-president Scott Bradley said the world’s largest telecommunications manufacturer does not pose a threat to cybersecurity in Canada or the United States. The company has been operating in Canada since 2008 without any problems, he said.” He defends Huawei by providing the evidence that Huawei has been operating in Canada for over ten years without any problems. He then assures the public that Huawei conforms to the Canada government and operators’ objectives, and specifically points out that Huawei is in compliance with national security requirements in the following paragraph, “All of Huawei Canada’s business and research operations are conducted in a manner that reflects the objectives of the government and operators on a number of measurements, including national security.” Huawei’s contribution to Canada was supported by statistics provided by Mr. Bradley in the following paragraph, “Canada is a world leader in 5G and that Huawei’s investment in this technological research supports 700 jobs and contributes to a ‘thriving, competitive telecommunications ecosystem’ in the country.”

Although the tone of these statements about Huawei are positive, their force is undermined due to their source being a Huawei executive, who would be a biased source, defending Huawei naturally.

A non-Huawei source is added in the following paragraph, “On Friday, Bell provided a brief statement to The Globe: ‘Huawei is one of our longstanding network infrastructure and mobile device partners.’” However, “A spokesman for Bell Canada would not comment on whether there were security risks with Huawei products.” These statements from the spokesman for Bell Canada appeared unclear whether Huawei should be trusted when it comes national security. Even though, she admitted Huawei’s “longstanding” business partnership with her company, such an argument is altogether too weak to effectively counter the earlier NST arguments.

Another fact was brought up that concerns Huawei’s operation in Great Britain as a comparison in the following paragraph:

The Chinese telecom behemoth, which operates in 170 countries, is running parts of Britain’s broadband and mobile infrastructure, but the British government says it has mitigated the threat by checking over Huawei equipment at a cyber evaluation centre for possible back doors, faults and bugs that could be exploited for espionage purposes. The Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre was created as a compromise between security misgivings and the private sector’s desire for cheap technology.

Note that the British government proposed “a cyber evaluation centre” to mitigate “the threat.” In other words, Great Britian considered Huawei to be a threat to its national security, and the cyber evaluation centre is portrayed only as “a compromise” between “security misgivings” and “desire for cheap technology”, in other words, it is a bridge between the NST frame and the VP frame.

However, this solution was challenged by Wesley Wark in the following paragraph who was described as a security and intelligence expert and a professor at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs quoted as, “CSE does not have the same capabilities as the British Huawei evaluation centre.” He went on to conclude strongly, “any embedding of Huawei products in digital and information-critical infrastructure, especially at the federal government level, should be a no-go area.”

The last paragraph of the whole article, which provides a sense of closure and sets the conclusion tone, goes: “Huawei, founded by former Red Army officer Ren Zhenfei, has no public list of shareholders, but says it is privately owned and independent from the Chinese state.” The author strategically pointed out Huawei’s founder’s former identity as “red army officer” indicating his connection with the Chinese military, and Huawei’s status of not being listed. This discredited Huawei’s claim of being a private company independent of the Chinese state.

In conclusion, even though the National Security Threat frame and Valued Partner frame coexist, discourse analysis uncovers that the VP frame is far less powerful and convincing than the NST frame due to the very limited space given to the VP frame with either biased or ambiguous sources quoted. In contrast, the NST frame was strongly supported by mostly upper tier sources according to the cascade activation model, and foreign allies, and thus, prevails all the other frames and sets a predominantly negative tone. The possible way (building a cyber evaluation center) to mitigate the contradictory perceptions of Huawei as NST and VP was rejected as well.

4.4 The public opinion

How did the public react to Huawei media reports in our sampled time frame? According to the cascading activation model, the public is at the very bottom of the hierarchy and does not have much power. In general, the public accepts the media reports. This is particularly true in matters of foreign affairs and policy. In this case, in the midst of a national debate on Huawei’s participation in Canada’s 5G construction, a critical event occurred when Huawei’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, was arrested. When China retaliated with the arrest of two Canadian men, the stakes were greatly heightened. At this point, the attitudes and opinions of the Canadian government and those of most other Canadian social and political elites diverged on the debate. According to our analysis, the media sided with the social and political elites, as well as the US and the FVEY allies. The media plays a major role in shaping the public’s impression about another country (e.g., Entman 2003; Saleem 2007), and in our case, a company from that country.

Which party, the Canadian government or the media, will have more influence on the Canadian public? The G & M took the initiative to commission Nanos, a research company to conduct polls during our sampled period. These polls give us an idea of the Canadian public opinion. A poll of 1,000 randomly chosen Canadians across the country was taken between Aug. 23 and 27, 2018. The G & M reported this poll on September 7th, 2018, “more than half of Canadians believed Canada should block Huawei from its 5G network. Only 16 per cent of people surveyed favour allowing Huawei to participate.”(The Globe and Mail Nanos 2018) The G & M concluded that most of Canadians appear to be against Huawei. In addition, the poll indicated that “most respondents also did not agree with China’s assertions that a ban would be discriminatory and hurt Canadian consumers.”

After the arrest of Meng took place The G & M reported another two Nanos polls with a six-month interval, each conducted among 1,000 randomly sampled Canadians between Dec. 30, 2018 and Jan. 5, 2019, and between May 31 and June 4, 2019 respectively. The first poll was reported to show “56 % of Canadians surveyed think the arrest of Meng is ‘primarily a justice issue’ and Canada p acted properly in detaining her for possible extradition to the United States on allegations of fraud relating to U.S. sanctions against Iran.”(The Globe and Mail Nanos 2019) Both Nanos polls found 53 % of Canadians thought Ottawa should bar Huawei from providing 5G equipment while 18 % and 20 % respectively felt this was an overreaction and Canada should allow Huawei to sell its 5G technology to domestic wireless firms.

The G & M quoted Mr. Nanos, “The key message here for the government or for any politician is that you should be extremely careful in your relations with China from a political perspective,” and “Canadians’ perspectives of China tend to be negative. They have concerns related to security and it is a political risk to being ameliorating [relations] or overly friendly to China.”

Then, an Angus Reid online poll was reported on Dec. 11, 2019. The result showed 69 % of the sampled Canadians were against Huawei’s involvement in Canada’s 5G construction. The article reporting this on-line poll said, “The poll comes as the United States continues long-standing efforts to convince its allies such as Canada to bar Huawei as a threat to national security because of the influence of the Chinese government.” However, there seemed to be a divide on the issue concerning the arrest of Meng Wanzhou. The article reported, “51 % of respondents in the latest poll said Canada should have resisted the U.S. request to arrest the Huawei executive, while 49 % said it made the right decision.”

The results of these polls show a strong tendency of the Canadians’ public opinion. It is highly in tune with the media’s predominantly negative view and attitudes towards Huawei. Comparing the poll results, one finds a stable con-position among over half of the surveyed Canadians on the national debate whether Huawei should be allowed to contribute to Canada’s 5G construction. The G & M has conveyed a strong message to the government – the predominantly negative view on Huawei – by quoting Canada’s social and political elites, the US officials, most of the other FVEY allies and the public opinions since the beginning of 2018, the starting point of our sampled period.

5 Discussion

Statistical results of the content analysis combined with the discourse analysis have provided us with a relatively insightful even though incomplete picture of The G & M’s media framing about Huawei during the sampled time period. To answer RQ1, we identified six media frames: National Security Threat, Valued Partner, Intellectual Property Seeker, Agent of China Dominance, Pride of China and Center of Sino-West Conflict. Five of these frames are negative with only one being positive. To answer RQ2, we identified the primary information sources as Canadian government officials, other Canadian political and social elites, American government officials, journalist themselves, Huawei Management, Chinese government officials, and other sources. The media framing emphasized other Canadian social and political elites and American government officials. These sources supported the con side of the Huawei 5G participation debate as opposed to the government’s more moderate position, which supported Huawei’s participation. In answering RQ3, we found that the critical event of Meng’s arrest lead to significant change in media framing. While the NST frame was still dominant, two new frames, the Center of Sino-West Conflict and the Pride of China appeared. The CSC frame became the 2nd most dominant in terms of frequency. Information sources also changed, with the journalists taking significantly more initiative in analyzing and commenting on the situation. Our hypothesis based on cascading activation model is partially supported, which indicates that modification need to be made in order for cascading activation to happen at least in media contexts outside of the US. One condition would be no event happens for a long time which brings the event driven tendency. Finally, polls done before and after the event indicate that the public opinion of Huawei did not greatly change. Over half supported the con side of the Huawei 5G participation debate and most also supported the government’s action of arresting Meng on the request of the US, which indicates the power of the media on the public has remained.

In general, our findings support indexing hypothesis (Bennette 1995). The media tried to use all frames indexing a variety of sources. In this case, the US officials and most of other FVEY allies were critical sources feeding into the NST frame. They also provide partial support for the cascading activation model (Entman 2003). In this case, however, the media seemed to reflect not the opinions of the top tier in the cascading activation model, the government, but instead followed more closely the second tier, that of other social and political elites. This may be a product of democratic efforts made by The G & M to combat the government’s view. Actively finding out and presenting the public’s opinions is another effort made by The G & M to be democratic by commissioning and reporting the Nanos polls. The G & M showed a more event driven tendency after the arrest of Meng and the subsequent Chinese government’s retaliation. A more diversified themes appeared, and more sources were quoted other than just the range of official and elite voices. Frames and topic domains about Huawei shifted to focus on the events and the consequences in international relations. Throughout the sampled period of time, public opinion is largely consistent with the media, echoing the cascading activation model. In the meanwhile, in this case, the “pump mechanism” (Entman 2003: 420) was possibly produced by the public to affect the media, through which, the government will potentially be influenced in their decision making.

Globalization brings risks and the potential clash of ideologies and cultures. The media plays a very important role in this class as it provides the information and opinions that contribute to the images of other countries in their target readers’ mind (e.g., Allen et al. 2018; Kiousis and Wu 2008). A primary schema in the minds of Western audiences is that China is “a country characterized by rampant corruption, political repression, and the mistreatment of its citizens” (Chen and Gunster 2019, p. 3), and this schema is supported by media reporting. Media frames are manifestations of such long-formed schemas which influence the public and are reinforced by the public. “The most inherently powerful frames are those fully congruent with schemas habitually used by most members of society” (Entman 2003: 422). While The G & M did show a “democratic tendency” in the national debate by quoting sources which opposed the government’s opinion, these sources and the framing of the information primarily supported the stereotypical China schema. Hence, our findings echo previous studies in that the tone of the media was negative in general (e.g., Chen and Gunster 2019; Fang and Chimenson 2017) as the con side of the national debate was greatly emphasized. Canada’s non-administration elites, as well as the US officials and other FVEY allies, were more prominent sources than the Canadian administration.

The arrest of Meng, Huawei’s CFO, and China’s subsequent retaliation are critical events which ruined the Canadian government’s hoped-for win–win approach to Sino-Canada cooperation, revealing a serious relational crisis deeply embedded in ideological, cultural, and historical differences. The West’s good will and tolerance towards China are breaking at certain point when China is much more ambitious and aiming at a much more powerful dominance than ever before. The media, in this case, The G & M reflects this trend of anti-globalization (Fang and Chimenson 2017), despite Canadian government’s more moderate position towards Huawei. The public have been consistently negative, having being largely influenced by the media over a long period of time.

6 Conclusions

The G & M made great efforts to voice opposite views against the government’s view. Despite such democratic endeavors, the media still operates under long-formed cultural schemas which may result in habitual thinking, group thinking and even false thinking. Entman (2003: 420) quoted other scholars to conclude that all (i.e., all actors in the cascading activation model are “‘cognitive misers’ (Iyengar and McGuire 1993; Sniderman et al. 1991) who work in accordance with established mental maps and habits (Fiske and Taylor 2020; Marcus 2000) and rarely undertake a comprehensive review of all relevant facts and options before responding. Few political leaders or journalists have the time to do that, and even fewer members of the public have the inclination”. Huang and Leung (2005) argue, however, that another possibility exists – that in fact it is the Chinese government’s own doing that has resulted in the negative view and attitudes portrayed in the media reporting on China and China-related entities.

The biggest limitation of this study is that the sampled period is relative short and only one mainstream on-line newspaper is sampled, resulting in a rather limited media channel being investigated. Given the rise of social media for years, it is hard to get to the conclusion that this particular media has the major influence on the public. To improve the study, social media concerning the portrayal of Huawei and how the public react to them can be investigated to supplement the data as well as to test the cascading models in today’s new media era. At last, intercoder reliability needs to be reported for each frame. This study only calculated and reported the overall inter-coder reliability.

Canada’s national debate about Huawei’s role in 5G construction almost came to an end in May, 2022, when Canada finally decided to ban Huawei from contributing to its 5G construction (Curry and Polsadzki 2022). This study casts light on how the media could fall back on the long-formed schema and bias concerning foreign affairs and policies and, as a result, reinforce these perceptions. A cautionary note can be taken by journalists when reporting on foreign corporations from emerging economies that democracy does not simply mean reporting views opposite to the government but also means reporting different voices including those from another ideological camp and being critical and reflective about long-formed perceptions.

References

Allen, Nathan, Andrea Lawlor & Katerina Graham. 2018. Canada’s twenty-first century discovery of China: Canadian media coverage of China and Japan. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 25(1). 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/11926422.2018.1439394.Suche in Google Scholar

Althaus, Scott, Jill Edy, Robert Entman Entman & Patricia Phalen. 1996. Revising the indexing hypothesis: Officials, media, and the Libya crisis. Political Communication 13(4). 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1996.9963128.Suche in Google Scholar

Baum, Matthew & Tim Groeling. 2009. War stories: The causes and consequences of public views of war. Prinston, NJ: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400832187Suche in Google Scholar

Bennett, Lance. 1990. Toward a theory of press-state relations. Journal of Communication 40(2). 103–125.10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.xSuche in Google Scholar

Bennett, Lance. 1995. Journalism norms and the construction of the political world. paper presented at the annual conference of the International Communication Association. Albuquerque, NM.Suche in Google Scholar

Bennett, Lance & Regina Lawrence. 1995. News icons and the mainstreaming of social change. Journal of Communication 45(3). 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1995.tb00742.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Brewer, Paul., Joseph Graf & Lars Willnat. 2003. Priming or framing: Media influence on attitudes toward foreign countries. International Communication Gazette 65(6). 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549203065006005.Suche in Google Scholar

Chazan, Guy. 2017, February 14. EU capitals seek stronger right of veto on Chinese takeovers: Berlin, Paris and Rome want legal basis to block state-backed moves on key industries. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/8c4a2f70-f2d1-11e695ee-f14e55513608 (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Sibo & Shane Gunster. 2019. China as Janus: The framing of China by British Columbia’s alternative public sphere. Chinese Journal of Communication 12(4). 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2018.1530686.Suche in Google Scholar

Curry, Bill & Alexandra Polsadzki. 2022. Canada to ban Huawei from 5G network, ministers say. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-huawei-5g-network-banned-canada/ (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

De Swert, Knut & Ruud Wouters. 2011. The coverage of China in Belgian television news: A case study on the impact of foreign correspondents on news content. Chinese Journal of Communication 4(3). 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2011.594561.Suche in Google Scholar

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2009. The Globe and Mail. web.archive.org/web/20090425174541/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/235427/The-Globe-and-Mail (accessed 6 March 2025)Suche in Google Scholar

Entman, Robert. 1991. Framing U.S. coverage of international news: Contrasts in narratives of the KAL and Iran Air incidents. Journal of Communication 41(4). 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1991.tb02328.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of communication 43(4). 51–58.10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.xSuche in Google Scholar

Entman, Robert. 2003. Cascading activation: Contesting the White House’s frame after 9/11. Political Communication 20(4). 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600390244176.Suche in Google Scholar

Entman, Robert. 2004. Projections of power: Framing news, public opinion, and US foreign policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226210735.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Evans, Paul. 2017. Canada-China relations: A note on public attitudes. Public Policy Forum. https://medium.com/ppf-consultative-forum-on-china/canada-china-relations-a-note-on-public-attitudes-50f257cc69f1 (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Fang, Tony & Dina Chimenson. 2017. The internationalization of Chinese firms and negative media coverage: The case of Geely’s acquisition of Volvo cars. Thunderbird International Business Review 59(4). 483–502. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21905.Suche in Google Scholar

Fiske, T. & Taylor, Shelley E. 2020. Social cognition: From brains to culture. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Gamson, William & Kathryn Eilene Lasch. 1983. The political culture of social welfare policy. In Shimon E. Spiro & Ephraim Yuchtman-Yaar (eds.), Evaluating the welfare state. Social and political perspectives, 397–415. New York: Academic Press.10.1016/B978-0-12-657980-2.50032-2Suche in Google Scholar

Gamson, William & Andre Modigliani. 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95(1). 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213.Suche in Google Scholar

Goodrum, Abby, Elizabeth Godo & Alex Hayter. 2011. Canadian media coverage of Chinese news: A cross-platform comparison at the national, local, and hyper-local levels. Chinese Journal of Communication 4(3). 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2011.594557.Suche in Google Scholar

Ha, Louisa, Ke Guo & Peiqin Chen. 2022. Mobilising public support for the U.S. China-trade war: A comparison of U.S. and Chinese news media. The Journal of International Communication 28(2). 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2022.2105926.Suche in Google Scholar

Huang, Yu & Christine Chi Mei Leung. 2005. Western-led press coverage of Mainland China and Vietnam during the SARS crisis: Reassessing the concept of media representation of the ‘other’. Asian Journal of Communication 15(3). 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980500261621.Suche in Google Scholar

Iyengar, Shanto & William James McGuire. 1993. Explorations in political psychology. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv11cw16rSuche in Google Scholar

Justus, Z. S. & Hess, Aaron. 2006. One Message for Many Audiences: Framing the Death of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Consortium for Strategic Communication. 1-14.Suche in Google Scholar

Kania, Elsa & Lindsey Sheppard. 2019. Why Huawei isn’t so scary. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/12/huawei-china-5g-race-technology/ (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Kiousis, Spiro & Xu Wu. 2008. International agenda-building and agenda-setting: Exploring the influence of public relations counsel on us news media and public perceptions of foreign nations. International Communication Gazette 70(1). 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048507084578.Suche in Google Scholar

Krippendorff, Klaus. 1980. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Lams, Lutgard. 2016. China: Economic magnet or rival? Framing of China in the Dutch- and French-language elite press in Belgium and The Netherlands. The International Communication Gazette 78(1–2). 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048515618117.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawrence, Regina. 2000. The politics of force. Berkeley: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Manheim, Jarol & Robert Albritton. 1984. Changing national images: International public relations and media agenda setting. American Political Science Review 78(3). 641–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961834.Suche in Google Scholar

Marcus, George E. 2000. Emotions in politics. Annual review of political science 3(1). 221–250.10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.221Suche in Google Scholar

Mullen, Jethro. 2017. Chinese exports fall as Beijing braces for Trump. CNN Money. http://money.cnn.com/2017/01/13/news/economy/china-exports-trade-trump/ (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Oliver, Pamela & Daniel Myers. 1999. How events enter the public sphere: Conflict, location, and sponsorship in local newspaper coverage of public events. American Journal of Sociology 105(1). 38–87. https://doi.org/10.1086/210267.Suche in Google Scholar

Ooi, Su-Mei & Gwen D’arcangelis. 2017. Framing China: Discourses of othering in. US news and political rhetoric. Global Media and China 2(3–4). 269–283.10.1177/2059436418756096Suche in Google Scholar

Pan, Zhongdang & Gerald Kosicki. 1993. Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication 10(1). 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963.Suche in Google Scholar

Phillips, Nelson & Cynthia Hardy. 2002. Discourse analysis: Investigating processes of social construction, 50. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Robertson, Susan & Castaldo, Joe. 2018. How Huawei has worked to build Its brand in Canada. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-how-huawei-has-worked-to-build-its-brand-in-canada/ (Accessed 6 March 2025)Suche in Google Scholar

Saleem, Noshina. 2007. U.S. media framing of foreign countries image: An analytical perspective. Canadian Journal of Media Studies 2(1). 130–162.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, William L., David, M. & Kevin, D. Melendrez. 2010. The financial crisis and mark‐to‐market accounting: An analysis of cascading media rhetoric and storytelling. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 7(3). 281-303.10.1108/11766091011072765Suche in Google Scholar

Sniderman, Paul M., Richard, A. & Philip E. Tetlock. 1991. Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511720468Suche in Google Scholar

Speer, Isaac. 2017. Reframing the Iraq war: Official sources, dramatic events, and changes in framing. Journal of Communication 67(2). 282–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12289.Suche in Google Scholar

Stavro, Elaine. 2014. SARS and alterity: The Toronto-China binary. New Political Science 36(2). 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2014.883802.Suche in Google Scholar

Stratmann, Klaus. 2017. Germany, Italy and France Push for E.U. powers to block strategic investors: The economics ministers from the Euro zone’s three-largest economies said Brussels should be able to block strategic acquisitions by state-backed investors. Handelsblatt Global. https://global.handelsblatt.com/companiesmarkets/germany-italy-and-france-push-for-e-u-powers-to-block-strategic-investors-704844 (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Tankard Jr, James. 2001. The empirical approach to the study of media framing. Framing public life, 111–121. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.10.4324/9781410605689-12Suche in Google Scholar

The Globe and Mail. In Stephen, D. Reese, Oscar, H. Gandy, Jr., August, E. Grant (eds.). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Globe_and_Mail#cite_note-5 (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

The Globe and Mail Nanos, Survey. 2018. National survey, Project 2018-1260A. https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.47/823.910.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2018-1260A-Globe-August-Huawei-Populated-report-with-tabs.pdf (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

The Globe and Mail Nanos, Survey. 2019. National survey. Project 2018-1356. https://www.nanos.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2018-1356-Globe-December-Populated-Report-with-Tabs.pdf (accessed 11 December 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Tilt, Bryan & Qing Xiao. 2010. Media coverage of environmental pollution in the People’s Republic of China: Responsibility, cover-up and state control. Media, Culture & Society 32(2). 225–245.10.1177/0163443709355608Suche in Google Scholar