Abstract

Purpose

Guided by the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication model (CERC, Reynolds and Seeger 2005. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication 10(1). 43–55.), the present study aimed to study how X (formerly Twitter) users sensemaking and efficacy based message. Additionally, the study also aimed to understand how the World Health Organization (WHO) responded to the emerging conversation.

Methods

Unsupervised machine learning was conducted on 6.1 million tweets between January and March 2020 to understand sensemaking about COVID-19 among X users. Additionally, content analysis was used to examine if the World Health Organization (WHO) responded to popular emerging conversations via content on their own X handle.

Findings

The majority of dominant topics in COVID-19 tweets from January to March 2020 related to understanding the virus and the crisis it caused. X users tried to make sense of their surroundings and re-create their familiar world by framing events. Content analysis revealed that WHO engaged in effective social listening and responded quickly to dominant X conversations to help people make sense of the situation.

Practical Implications

The initial stage of COVID-19 pandemic was marked with uncertainty. However, WHO had a robust communication strategy and addressed the dominant conversation during the time frame including debunking misinformation.

Originality/Value

The present study fills the research gap by situating the themes in the context of the health crisis and extending the CERC model to user-generated content via the lens of sensemaking and efficacy messages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the study segmented the timelines into smaller time intervals to understand how sensemaking evolved over time.

1 Introduction

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization received reports of several pneumonia-like cases in Wuhan, China. Since then, a global health threat has grappled the world. During a health crisis, effective communication is critical to helping people understand the situation and take appropriate action to reduce risk (e.g., Vos and Buckner 2016). Social media has become a popular way to exchange messages, especially about health (e.g., Park et al. 2016; Tan and Datta 2023; Thygesen et al. 2021). During a health crisis, users seek real-time health information (Lachlan et al. 2016). Providers and health organizations can use social media to share real-time health information (Kullar et al. 2020). Given the dynamic nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, social media was vital in keeping people informed and helping them make sense of the uncertainty (Tan and Datta 2023; Thygesen et al. 2021). Vos and Buckner (2016) found that during the H7N9 bird flu outbreak, X (formerly Twitter) became a primary channel for messages that helped users with the process of sensemaking during the public health emergency. Given that a crisis event typically involves fear, anxiety, uncertainty and panic (Kayes 2004), previous crisis communication research (Veil et al. 2008) highlights the need for messages that allow people to make sense, comprehend and enhance understanding of the crisis (Weick et al. 2005) as well as encourage individuals to take appropriate action (Colville et al. 2013).

In fact, the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication model (CERC; Reynolds and Seeger 2005) from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that early in a health crisis, messages should help with sensemaking as well as raise awareness of ongoing risks and prepare people to take appropriate measures to mitigate them. The CERC is an important theoretical framework in the realm of health and crisis communication that adopts a stage-model approach (Reynolds and Seeger 2005), helping to identify, understand, and address the different types of information and communication strategies relevant to the discrete phases and stages of a crisis or risk event (Sellnow and Seeger 2013; Troy et al. 2022). Previous research of public health emergencies (e.g., Kieh et al. 2017; Lwin et al. 2018; Vos and Buckner 2016) have utilized the CERC model for examining communication efforts. For example, Lwin et al. (2018) used CERC to thematically analyze the strategic use of Facebook posts related to the Zika virus in Singapore.

The first objective of this study was to examine COVID-19 pandemic tweets during the initial stage using the CERC model (Reynolds and Seeger 2005) to better understand the sensemaking of X users. Specifically, we used unsupervised machine learning techniques to understand how a global audience was making sense of the unfolding crisis and sharing information about COVID-19 on X. Prior studies (e.g., Abd-Alrazaq et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2020) have examined dominant topics on X using unsupervised machine learning. The present study is building on previous literature by situating the themes in the context of the health crisis and extending the CERC model to user-generated content via the lens of sensemaking and efficacy messages in context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The CERC model’s structured framework, along with its emphasis on principles like timely, accurate, credible, and empathetic communication, as well as promoting action (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2018), aligns well with the characteristics of the social media and social listening, making it a suitable lens for this analysis. Additionally, the study segmented the timelines into smaller time intervals to understand how sensemaking evolved over time.

The researchers also sought to explore how WHO addressed popular topics discussed on X to help people make sense of and disseminate self-efficacy messages and when WHO shared messages with the public. According to Weick and Sutcliffe (2006), lack of attention and focus can hinder sensemaking, especially when dealing with large amounts of information. Timing is especially important as fake news gets seen far more than the information correcting the falsehood (Vosoughi et al. 2018). Additionally, another problem observed during the COVID-19 pandemic was the spread of “infodemic”- an overabundance of information which can pose challenges for the public (Erku et al. 2021). One of the ways to counter this problem is via social listening and use of machine learning (Eysenbach 2020). Notably absent from prior research is the understanding of the role and the use of machine learning tools for social listening by health organizations during a major health crisis. We chose WHO as the main health organization because it is a trusted source of health information and regularly communicates with its stakeholders via X (Hönings et al. 2022). In health emergencies, the World Health Organization also serves a prominent role in helping countries organize assistance and responses, especially in terms of helping craft “press releases” and “talking points” (Medford-Davis and Kapur 2014: 3). Additionally, WHO had also stated that the organization had proactively developed analytical tools using artificial intelligence to detect emerging narratives gaining traction in online discussions during the COVID-19 (World Health Organization 2021). Overall, the current study builds up on the existing research and fills a critical gap, extending the utility of the CERC framework to examine communication surrounding infectious disease pandemics like COVID-19 and understand how WHO effectively used social listening to detect and respond to emerging online discussions.

2 Literature review

2.1 CERC framework, sensemaking, and self-efficacy

Health crises occur in myriad formats, places, etc., and so institutions need effective methods for communicating key information to the public (e.g., Seeger et al. 2020). One such communication model is Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication model, developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to “educate and equip public health professionals for expanding public health communication responsibilities in emergency situations” (Veil et al. 2008: 26). The CERC model has been used in prior public health crisis research such as influenza (Vos and Buckner 2016), Ebola (Kieh et al. 2017), Zika outbreak (Lwin et al. 2018), etc. to analyze communication strategies and their impact on public perception and behavior. The findings demonstrated the adaptability of the CERC model for effective communication across various stages of disease outbreak (pre-outbreak, during and post outbreak). However, the researchers (Lwin et al. 2018) assert the need for further testing and refinement of the CERC model to understand health outbreak communication on other social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter), as well as for other infectious diseases.

CERC views any crisis as an ongoing event that progresses through stages with specific and unique communication needs and strategies (Miller et al. 2021; Reynolds and Seeger 2005; Veil et al. 2008). Pre-crisis, initial event, maintenance, resolution, and evaluation are the CERC’s five stages of crisis progression. This study focuses on the first two stages: pre-crisis and initial event. We focused on the first phase of the pandemic, from December 31, 2019 (when a Chinese doctor alerted WHO to the virus) to April 1, 2020 (a few weeks into the pandemic when the majority of the world was experiencing quarantine).

Pre-crisis is an incubation stage where a threat has emerged but the crisis has not yet unfolded (Seeger et al. 2020). Because crises are unpredictable, messages distributed at this stage include warnings to educate the public about the risks and information to help them monitor and prepare in case the threat becomes a crisis (Seeger et al. 2020).

The initial event stage of the crisis is the triggering event that indicates the crisis is underway. At this stage, the crisis is fast developing, often eliciting a strong sense of threat, panic, and ambiguity among publics because information about the crisis remains scattered, incomplete, or even contradictory (Reynolds and Seeger 2014). Aiming to reduce uncertainty and reassure the public about the various measures taken to improve the situation, CERC advises communicators to provide timely updates. Messages should include statements that are sympathetic and reassuring to the affected groups. The messages should also be simple and provide general information about immediate risks, the crisis, expected outcomes, and appropriate actions including self-efficacy promotion (Reynolds and Seeger 2014; Seeger, Reynolds & Day 2020). Sensemaking and self-efficacy are key processes at this stage of CERC.

2.1.1 Sensemaking

The CERC sensemaking concept comes from Karl Weick’s seminal work (1988, 1995). Making sense of an event that is “novel, ambiguous, confusing, or in some other way violates expectations” is called sensemaking (Maitlis and Christianson 2014: 57). Negative events or situations often create ambiguity and uncertainty in a crisis. To restore or renew their understanding of the world they have always known, people tend to take explicit steps to make sense of events based on personal experience (Festila et al. 2021; Weick 1988). They may or may not be fact-based in their efforts to find meaning, order, and reduce the uncertainty during a crisis (Weick et al. 2005). Action, comprehension and evaluation of potential responses, identifying patterns, and informing future interpretations are all possible through sensemaking (Festila et al. 2021; Weick 1995).

In a global health crisis (e.g., COVID-19) where normal life operations, functions, and routines break down, people feel compelled to make sense of things and ask themselves and others questions like “what’s the story?” “Now what?” Within crisis communication, Vos and Buckner (2016) found that spreading information about the H7N9 virus on X promoted sensemaking by informing the public about the crisis. Sensemaking occurred by putting the emerging crisis into context, educating the public (e.g., virus spread and case count), accommodating the unexpected, and identifying patterns. Dailey and Starbird (2015) discovered that people used X for collective sensemaking of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill by understanding how to interpret the complexities of the technical and scientific crisis.

2.1.2 Self-efficacy

Moving from the pre-crisis stage to the initial event, instilling a sense of self-efficacy – in addition to facilitating sensemaking – becomes paramount (Reynolds and Seeger 2005). Self-efficacy is confidence in one’s ability to change behavior and respond to specific situations (Bandura 1997). In a crisis, self-efficacy encourages people to believe that the suggested crisis response is feasible and worth adopting. More importantly, self-efficacy empowers people to take action because it fosters self-belief that they can perform the recommended behavior to reduce risk (Coombs 2009). A sense of control in a crisis reduces uncertainty, confusion, and ambiguity. Reynolds and Quinn (2008) recommended disseminating information that can reduce the spread of infectious diseases. These messages included frequent handwashing, avoiding touching one’s face, social distance, wearing a mask, avoiding places with poor ventilation, and cleaning and disinfecting touched surfaces (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023b).

Thus, the first goal of the current study was to address the following research question:

RQ1:

During the pre-pandemic period, which types of (a) sense-making messages and (b) self-efficacy messages appeared on X?

2.2 Social media, infodemic, and social listening

During the COVID-19 crisis, social media became a source of infodemic, an epidemic of information that may or may not be accurate (Lu et al. 2021; Tangcharoensathien et al. 2020; Zarocostas 2020). Eysenbach (2020) described the COVID-19 infodemic using the “informational cake model,” according to which the volume of information has four levels: (a) science, (b) policy and practice, (c) news media, and (d) social media. The social media platforms constitute the largest portion of the cake, containing the largest amount of unfiltered information.

An infodemic can hinder sensemaking. In the context of COVID-19, a flood of inconsistent, inconclusive, and contradictory information on social media can confuse the public. Instead of helping people comprehend what is happening, an infodemic can “pose concerns for the public to distinguish fact from fiction and, for government agencies to conduct evidence-based policy making” (Erku et al. 2021: 1955). Previous research has connected various infodemics to misinformation (e.g., Chowdhury et al. 2023; Do Nascimento et al. 2022), and misinformation impacted COVID-19 (Chowdhury et al. 2023). Misinformation in health communication could be fatal to people (Cheng and Nishikawa 2022), especially considering that COVID-19 contributed to the deaths of 6.7 million people as of January 2023 (World Health Organization n.d.). Social media users lacking medical expertise engaged in messaging to delegitimize public health officials, too (Chen et al. 2023). Eysenbach (2020) proposed several infodemic management strategies. One was constant social media monitoring or listening (i.e., “infovigilance”).

Social listening is the practice of monitoring social media data and discussions (Stewart and Young 2018). At one point during the COVID-19 pandemic, tweets about COVID-19 were circulated every 45 ms (Josephson and Lambe 2020). Since social media permits rapid diffusion of pandemic-related health information, the role of social listening warrants further attention. Real-time monitoring of COVID-19 conversations on social media can help cut through the noise and help affected communities respond effectively to threats. Public often uses social media platforms, including X, for sensemaking during crisis, such as COVID-19 (Thygesen et al. 2021; Valiavska and Smith-Frigerio 2023). Incorporating social listening into public health messaging helps people understand the disease and its scope, potentially reducing the effects of an infodemic and providing direct access to accurate information. However, organizations are limited in their effectiveness in combating misinformation (e.g., Bode and Vraga 2018; Liu et al. 2022; Vraga and Bode 2018). Liu et al. (2022) found that people with close connections can help stem the flow of misinformation, but sometimes efforts to fact check can actually have the reverse effect and strengthen some people’s belief in inaccurate information. Thus, experts do have limitations in their ability to correct already formed narratives.

Because of the volume and complexity of data collected from social media and UGC platforms, machine learning is an appropriate tool for social listening. Machine learning encompasses a wide range of computer-based data mining techniques designed to uncover complex patterns in large datasets and potentially inform decision-making. Previous research suggests that machine learning can highlight conversations during epidemics like the Zika virus (e.g., Miller et al. 2017). WHO emphasized/described the usage of AI and machine learning tools for social listening and infodemic management during the COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization 2021). Understanding social media conversations is important, but so is understanding how WHO used that vast amount of data to identify emerging trends, and address those trends swiftly. Therefore, the second goal of the current study was to address the following research question:

RQ2:

During the initial phase of COVID-19, how did WHO address dominant message categories on X (a) to help with sensemaking and (b) to formulate self-efficacy messages (c) help address misinformation?

3 Methods

3.1 Study design

To analyze the large dataset and answer the research questions, we used three methods. First, we used unsupervised machine learning to analyze content called Latent Dirichlet Allocations (LDA). LDA is a well-known unsupervised machine learning technique that uses Bayesian statistics to identify themes or patterns in unstructured text (Blei 2012; Kabir 2022). Scholars previously used this method to analyze COVID-19-related X data (Abd-Alrazaq et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2020). Emergent topics are not labeled by the LDA and need human interpretation. So, once the topics emerged, we used thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006; Kumble et al. 2022) to interpret the tweets. After identifying themes, we used content analysis to see if WHO used X to address dominant conversations.

3.2 Data collection

We scraped relevant data using “Tweepy” and “GetOldTweets” (Henrique, n.d) libraries on Python for dates ranging (December 31, 2019–March 31, 2020) while the situation was unfolding and on-going. Some of the notable events (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023a) during this time period were as follows:

China’s WHO office was “informed of several cases of a pneumonia of unknown etiology” on December 31, 2019.

WHO declared the virus a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” on January 31, 2020.

WHO named the virus COVID-19 on February 11, 2020.

WHO labeled “COVID-19 a pandemic” on March 11, 2020.

Additionally, this data was collected before the academic license for X existed. Some of the previous studies (e.g., Bacsu et al. 2021) have also used the same library to get X data. Search queries included “#2019nCov,” “#coronavirus,” “#Wuhan,” (for the first month in the date range), and “#COVID-19.” After cleaning the data for duplicates and removing WHO tweets from the main dataset, we analyzed 6,168,274 user-generated tweets in English. We conducted a second search using “Tweepy” to collect tweets sent by WHO (n = 2086).

3.3 Latent Dirichlet allocation

LDA uses probabilistic calculations to infer topics from a document (e.g., tweets) using a bag of words approach (Blei 2012; Kabir 2022; Wheeler et al. 2024). Given that the initial stages of the pandemic were unprecedented, and information was unfolding (the study authors did a thorough read of the WHO’s tweets during that timeframe to notice the change of information), the dataset was divided into smaller time ranges based on the timeline of events that unfolded and the volume of tweets generated. January and February 2020 had relatively fewer tweets (i.e., less than one million). Therefore, the authors did bi-weekly LDA models during those months. Since the number of tweets increased to over one million per week in March 2020, the authors conducted LDA analysis weekly, running a total of eight (8) LDA analyses using the following steps.

3.3.1 Data cleaning

The first step involved a thorough cleaning of the textual data and removing non-relevant components as those can hinder the coherence of the LDA model. Data cleaning for each LDA model was similar and is listed in Table 1 in the order in which each step was performed.

3.3.2 Topic determination

LDA models need researchers to enter the number of topics (k) that the model should generate. For this step, we performed tuning runs with LDA over a number of topics (k = 2–10) for each of the data. Additionally, LDA hyper-tuning parameters i.e., topic density within tweets (α) and word density within a topic (β) were also varied. We tested each k with α and β values ranging from 0.01–1.0 for each of the eight LDA models. For each combination of k, α, and β we calculated a coherence value measure (Cv), developed by Röder et al. (2015). A higher Cv value indicates better text-to-topic model coherence. A combination of k, α, and β that resulted in Cv >= 95 % of max Cv underwent further evaluation via topic visualization for the final model run and implementation.

3.3.3 Model selection and visualization

After identifying the highest Cv for each of the eight LDA models, the authors ran each one based on specific combinations of α and β, visualizing each of the results using the package LDAvis (Sievert and Shirley 2014). These visualizations provided specific insight into the discreteness (or lack of discreteness) of the topics.

3.3.4 Topic classification

The next step involved understanding topic distribution across the tweets (i.e., identifying which tweets belonged to which topics). Feature vector classification was conducted using the Gensim library Rehurek and Sojka (2011) in Python to determine this. Feature vector classification assigns a probabilistic ratio for each of the topics based on word weightage for each tweet and assigns the appropriate topic number to the tweet. To make the results more stringent, this study excluded tweets below 50 % probability which was assigned to topics.

3.4 Thematic analysis

After the machine learning algorithm identified the topics, it was time to identify the labels. Topic labels were created using thematic analysis (e.g., Braun and Clarke 2006; Kumble et al. 2022). Data-driven thematic analysis can be inductive (data-driven) or deductive (theory-driven), where the coding is done with the study’s main theory in mind (Braun and Clarke 2006; Lee and Barnett 2020). This study employed deductive coding to code the tweets for themes of sensemaking, efficacy, and misinformation. The authors looked at only the top two or three topics generated by the LDA model for each date range.

Braun and Clarke (2006) recommend six steps to generate themes from the dataset. The first step involves becoming familiar with the data. For this step, the authors became familiar with the top words in each topic. Next, based on the data, we generated initial codes. For this step, we randomly selected 1–4% of the tweets from each topic generated by the LDA model, depending on the sample size for the week and each author read the tweets to come up with the basic codes and also took down notes. The third step involves collating the codes and searching for themes within the data. For this step, the authors discussed the data and compared their notes, tweets, and co-occurring words to help determine topic labels. The fourth step involves reviewing potential themes. During this step, the authors resolved conflicts with the themes by discussing them further. For some topics, the authors went back to the previous step re-read the tweets and the collated codes to ensure both the authors agreed on the theme. The fifth step involves naming the themes from the codes (i.e., topics). In this step, once we identified the codes, we assigned them to 4 themes: sensemaking, efficacy, misinformation, and other. Sensemaking, and efficacy messages codes were adapted from previous research by Vos and Buckner’s (2016) coding scheme. Sensemaking codes involved themes of placing the emerging crisis into frameworks, enabling the public to comprehend what is going on (e.g., information about the spread of the virus and the number of cases), accommodating the unexpected, and identifying patterns in the crisis. Codes that indicated tweets containing non-verifiable messages were put under misinformation theme. The final step involves final analysis to ensure the themes are coherent and guided by the CERC model and picking out vivid and compelling tweets that best describe the codes, and the themes.

3.5 Content analysis of WHO’s tweets

In order to examine whether WHO addressed the dominant conversations that emerged on X during the specified time frame, content analysis was used. The authors manually checked the dominant topics for the computational models for the target weeks against the tweets that WHO posted during the corresponding period. Three coders independently reviewed tweets posted by WHO to see whether the dominant themes were present or absent and calculated the number of tweets that corresponded to the topic. The three coders reached a 98 % agreement.

4 Research findings

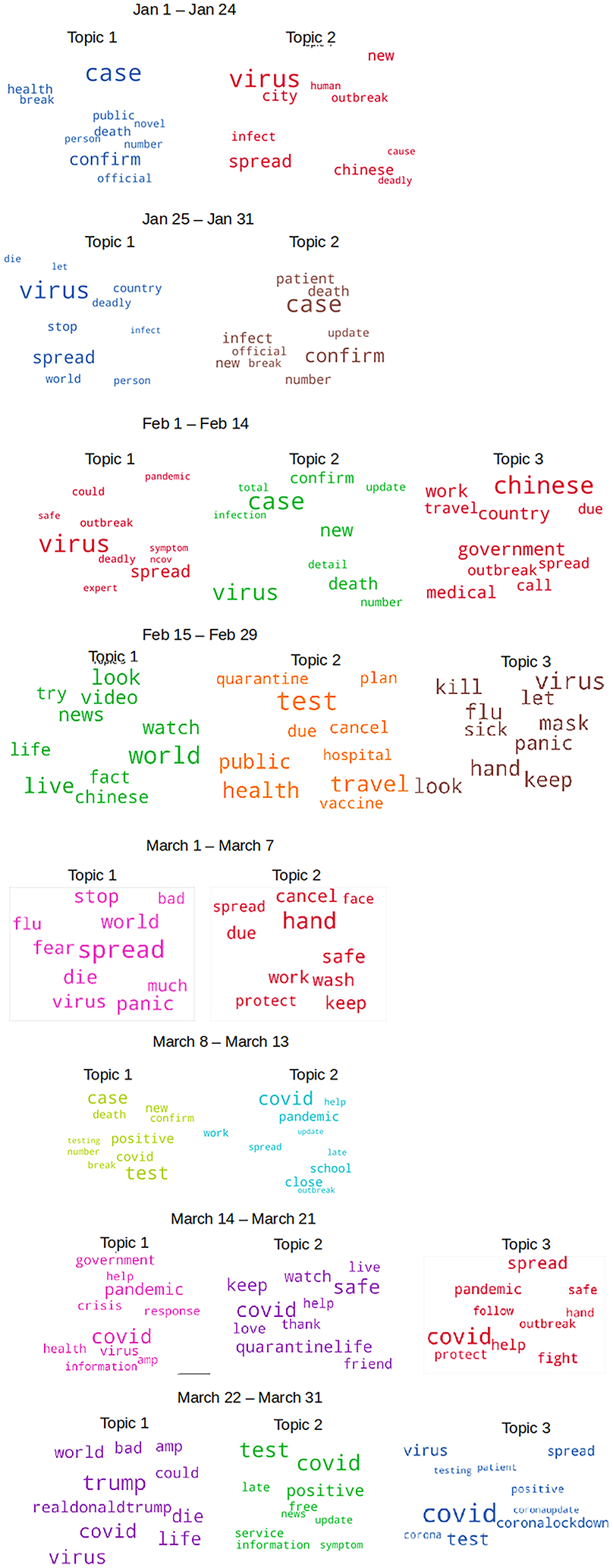

4.1 LDA topics by period

To address RQ1 and understand how publics on X made sense of the health crisis and shared self-efficacy messages, eight LDA analyses were conducted, one for each time period. Figure 1 presents the word cloud generated for the top topics during each period. The sections below detail the analysis of the top two or three topics for each period.

January 1–January 24. The authors analyzed 56,760 tweets from the first three weeks of January. The highest coherence score (Cv) was 0.35, corresponding to k = 6 discrete topics on LDAvis. A thematic analysis revealed that the top two topics for the time period were “number of cases of people suffering from nCOV-19” and “origins of the virus.”

January 25–January 31. Next 262,818 tweets from the last week of January were analyzed. The highest Cv was 0.36, corresponding to k = 8 discrete topics on LDAvis. After completing the thematic analysis, the top two topics for the time period were “outbreak and spread of the virus including blaming China” and “cases emerging outside of China and around the world.”

February 1–February 14. The authors analyzed 341,312 tweets from the first two weeks of February. The highest Cv was 0.34, corresponding to k = 6 discrete topics on LDAvis. After completing the thematic analysis, it was found that during this time period, the Twitterverse continued blaming China and the Chinese government and continued discussing the cases. Another dominant topic from this week was sharing scientific evidence about the novel virus and its spread.

February 15–February 29. A total of 477,628 tweets from the last two weeks of February were examined. The highest Cv was 0.37, corresponding to k = 6 discrete topics on LDAvis. Based on the thematic analysis, dominant conversations revolved around certain leaked Chinese videos (mostly misinformation videos) that fueled negative sentiment towards the Chinese government (20.42 % of the tweets). According to the thematic analysis, several tweets also flagged the content and corrected the misinformation. The next dominant theme was messages about quarantining cruise ship passengers. The third most popular topic was COVID-19 protection. Wearing masks, protecting eyes, and using natural remedies like lemon, garlic, and ginger to boost immunity were mentioned.

March 1–March 7. The authors analyzed 473,013 tweets from the first week of March. The highest Cv was 0.37, corresponding to k = 8 discrete topics on LDAvis. After completing the thematic analysis one of the dominant topics for this week was the impact of COVID-19, including cancellation of events and travel restrictions. The next most dominant topic was questioning the severity of COVID-19 and whataboutism vis-a-vis death rates and fatalities from other diseases like the flu.

March 8–March 13. Next 960,566 tweets from the second week of March were analyzed. The highest coherence score was 0.37, corresponding to k = 10 discrete topics on LDAvis. During this period, WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. The results from the thematic analysis indicated that one of the dominant topics for this week was this declaration and the shift to online delivery (e.g., work and education). The next most dominant topic was new cases and fatalities related to COVID-19.

March 14–March 21. There was a large increase in tweets as 1,860,130 tweets from the third week of March were examined. The highest coherence score was 0.37, corresponding to k = 8 discrete topics on LDAvis. With the declaration of the pandemic and stay-at-home orders issued in several countries around the world, one of the dominant topics that emerged during this week was life indoors. Another dominant topic was government response (or lack thereof), particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom. The next most dominant topic was COVID-19 mitigation behaviors.

March 22–March 31. A total of 1,694,047 tweets from the final 10 days of March were analyzed. The highest coherence score was 0.34, corresponding to k = 6 discrete topics on LDAvis. One of the dominant topics that emerged during this week was the politicization of the virus, primarily in the United States, and the upcoming stimulus bill. Another dominant topic was government response (or lack thereof), particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom. Another dominant topic was the lack of testing. The next most dominant topic was the call to support essential workers, including healthcare workers.

Topic word clouds with dominant co-occurring words for each topic mentioned in Table 2.

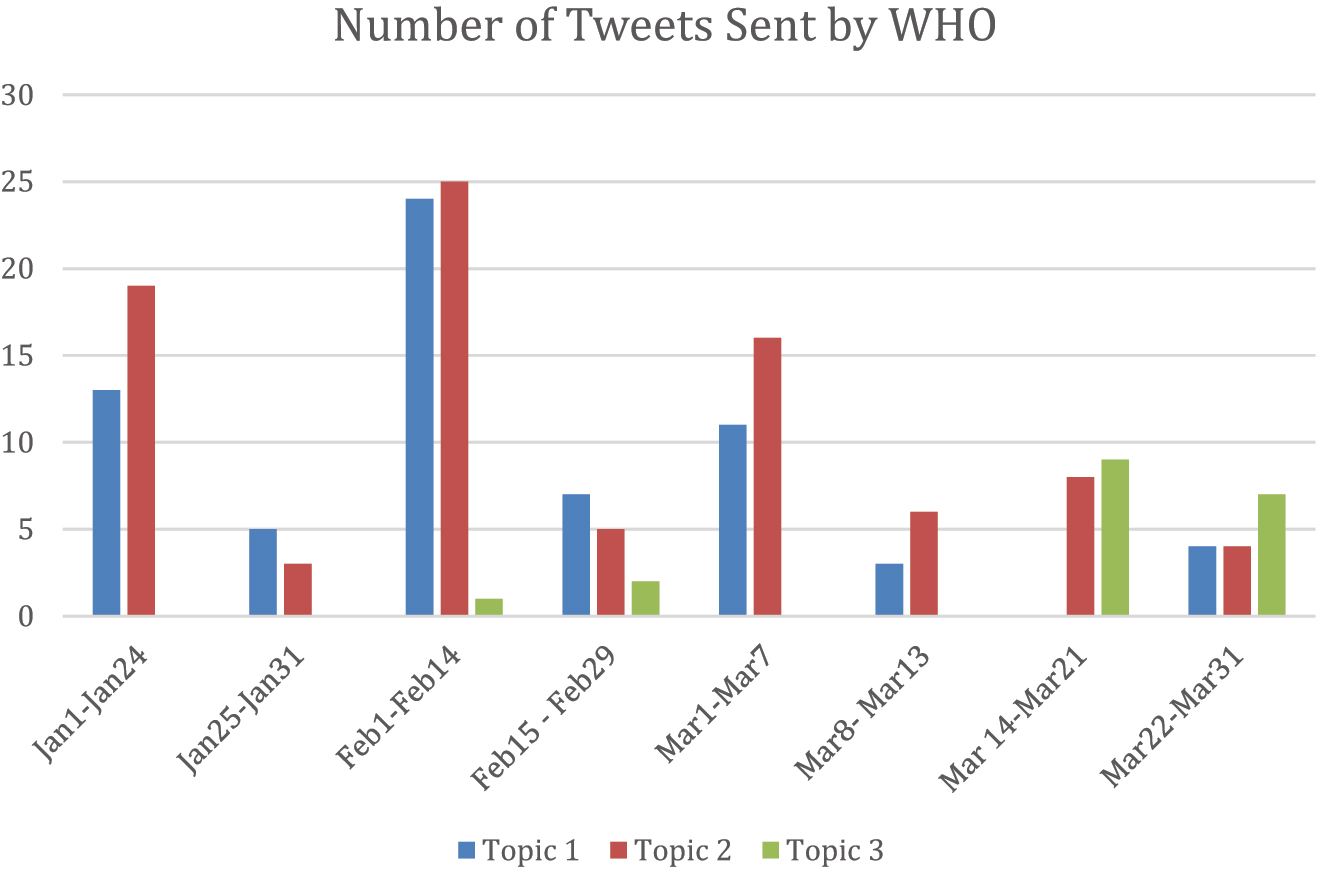

4.2 WHO tweets and social listening

A content analysis was conducted to address RQ2 as to whether WHO sent tweets addressing the dominant topics on X, potentially helping make sense of the health crisis. Three coders (including the two of the three study authors) independently looked at the dominant topics and compared them to determine whether WHO had addressed the topics during the respective periods. Results indicated that WHO disseminated tweets to address most of the topics in a timely manner. Table 2 indicates examples of tweets sent by WHO that addressed dominant topics, along with the date of the first tweet sent by WHO on that topic. Some topics (e.g., lack of effective leadership by the U.S. and U.K. governments) did not fall under the purview of WHO. Figure 2 indicates the number of tweets that WHO sent during each of the periods to address the dominant topics on X (Figure 2).

The number of tweets sent by WHO to address the dominant topics.

5 Conclusion and discussion

The current study had two objectives. First, the researchers used unsupervised machine learning LDA to analyze X trends and explore how X users interpreted a health crisis that turned into a pandemic. The study’s second goal was to see how WHO addressed popular topics on X to help with sensemaking and self-efficacy messages early in the pandemic.

5.1 X and sensemaking

The majority of dominant topics in COVID-19 tweets from January to March 2020 related to understanding the virus, and the crisis it caused. Twitter users tried to make sense of their surroundings and re-create their familiar world by framing events. Content analysis revealed that WHO engaged in effective social listening and responded quickly to dominant X conversations to help people make sense of the situation.

During January 2020, most X conversations focused on the number of reported cases, the virus’s origins and transmission, and blaming China. Attempts to frame the virus indicate an effort to reduce uncertainty and fill knowledge gaps about the unfolding health crisis. Throughout January, WHO sent out several tweets containing information that helped people understand what was going on, including the number of cases that arose both within and outside China. WHO also helped people prepare for the unexpected by providing timely information about the virus’s origins. For example, in mid-January the organization reported that an animal may have spread pneumonia-like symptoms in Wuhan, China, helping reduce ambiguity. WHO also tweeted messages expressing confidence in China, stating that China was investigating the virus, sequencing its genome, and sharing information with WHO. This type of information helped people understand the crisis.

As more information about the novel coronavirus emerged in February 2020, X users continued with the sensemaking process. During the first two weeks of February, one of the main topics of discussion was China’s role and transparency. Despite WHO’s efforts to reduce hostility, suspicion remained. Despite WHO’s efforts to promote scientific terminology, influential people and politicians kept calling COVID-19 the “Chinese Virus.” Because social media platforms thrive on message redistribution, more influential accounts than WHO could reach a larger audience and diffuse more stigma-laden tweets within the network. Towards the end of February, another dominant conversation focused on a video with misinformation about Chinese authorities mistreating COVID-19 patients. WHO began sharing information to encourage people to reduce stigma, hate, and to support those affected. WHO also enlisted the help of social media and technology companies (e.g., Google, X, Facebook) to track down misinformation.

By March 2020, the virus had gone global. By mid-March, WHO had declared COVID-19 a pandemic, and people were grappling with the new normal and how to manage quarantine. WHO addressed the issue by providing messages to promote physical and mental health. It even planned live online concerts on its X handle. Other major themes were fatality and case count. WHO assured the public that they were tracking and disseminating data promptly. The US and UK governments’ perceived inaction and the virus’s politicization were other themes (predominantly in the United States). Such topics would be difficult for any organization, let alone WHO. However, WHO did urge governments to keep citizens informed and assist those in need.

5.2 X and self-efficacy

While the X conversations were heavy on sensemaking, the results show that self-efficacy was mentioned frequently during a few of the periods. These messages helped people respond appropriately to the crisis (e.g., protective behaviors and preventive measures). Self-efficacy emerged as a dominant theme in late February. Several mentions of eye protection and masks were also noted. However, terms like “handwashing,” “six feet distance,” and “staying homesick” were not popular until March. CERC stresses the importance of self-efficacy messages early on. When a virus is new, non-vaccine self-efficacy is critical. Lack of self-efficacy messages on X was not a good sign, as previous research suggests the general public is unaware of their role in disease spread (Vos and Buckner 2016). However, the virus did not become truly global until mid-March, which could explain the delay. Additionally, this study may have missed self-efficacy tweets in other languages from people living near China because it examined English-language tweets only.

WHO began tweeting self-efficacy messages to educate the public about preventive behaviors on January 9, 2020. But this important topic fully emerge until late February. WHO’s self-efficacy messages may not have received enough retweets because social media users were not sufficiently engaged with the topic. WHO should consider partnering with social media influencers and celebrities to help spread the message. Actors and businessmen from all over the world are among the UN’s goodwill ambassadors. These influential people could help WHO spread messages by sharing those messages and setting agendas for social media users.

5.3 Misinformation in messages

This study also found messages that promoted sensemaking and self-efficacy simultaneously. Many of the tweets containing self-efficacy messages were not backed by scientific evidence. For example, by mid-February, some messages were promoting the use of garlic and lemon as preventive measures to boost immunity. Other messages suggested the use of ginger to boost immunity. Other messages suggested avoiding “foreign food” and “packages from China” in order to curtail the spread of the virus.

It is to be noted that WHO did tweet information debunking the misinformation and the myths. However, an infodemic was inevitable given the global scope of the health crisis. Concerns about the infodemic had been raised by WHO online by February 15, 2020, and subsequently, WHO organized an online conference to crowdsource on infodemic management (Tangcharoensathien et al. 2020). However, recent epidemics (Ebola, Zika, H7N9) show the prevalence of health misinformation and conspiracy theories (Chen et al. 2018; Oyeyemi et al. 2014; Vijaykumar et al. 2018).

5.4 Theoretical and practical implications

The study offers important theoretical implications. It expands the utility and adaptability of the CERC model by examining user generated content on social media platforms such as X. While bulk of research on CERC centers on the organization’s perspective (Tomasi et al. 2023) and communication strategies and tactics appropriate for the distinct phase of the evolving crisis, this study additionally demonstrates how the CERC framework examines how public processes and evaluates crisis information during the early stages of the outbreak in the digital age. Building on prior research (Lwin et al. 2018; Vos and Buckner 2016) consistent with CERC, the current study highlights the crucial role of social media platforms in disseminating public sensemaking and efficacy messages during the initial phases of a public health crisis. The findings revealed the presence of the two core CERC tenets-sensemaking and efficacy in the social media messages shared by users during the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic. These messages reflected the change in people’s awareness, understanding and sensemaking of the crisis, as well as their efforts to build self-efficacy in navigating the crisis. Such sensemaking and efficacy efforts play a key role in helping the public manage the uncertainty that arises from the crisis and assuage the anxiety that is triggered by unprecedented long-term, evolving public health crises like the pandemic.

The findings have practical implications. The study provides a case study on the understanding of the implementation of WHO’s social listening strategies to effectively address public concerns via sensemaking process and promoted protective behaviors during a global pandemic. While social listening can help experts understand dominant conversations, it can also help them infer missing ones. Health organizations can draw on these insights to refine their communication strategies, ensuring that they are not only reactive but also proactive in managing public discourse for future pandemics. Akin to previous findings on health crises (Lu et al. 2021; Tangcharoensathien et al. 2020; Zarocostas 2020), this study found people utilized social media to engage in sensemaking regarding COVID-19. However, WHO’s reactive approach to dominant conversations could be a suboptimal strategy if misinformation is prominent because fake news gets disseminated faster than information correcting the misinformation (Vosoughi et al. 2018). Additionally, health experts and organizations should explore amplifying the prosocial and accurate health messages from opinion leaders from various communities and constituencies (Liu et al. 2022). In some cases, these opinion leaders could also be more effective in correcting misinformation (Liu et al. 2022) than WHO itself.

5.5 Limitations and future direction

While the current study was robust, it has several limitations. First, we only analyzed English-language tweets. The results might not be replicable in other languages. Second, our search terms contained only certain relevant keywords. We certainly expect that our search results did not include all possible tweets about COVID-19. Finally, machine learning strategies have limitations. For example, LDA uses a “bag of words” approach, estimating the probability of certain words occurring together; furthermore, topic interpretation largely depends on human coding. Another challenge associated with machine learning is that online content can fit into multiple categories (Salminen et al. 2019). In addition, the algorithms for machine learning are not necessarily interchangeable across channels, potentially raising issues with labeling. Finally, we used only one social media platform, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results. While the results showed that WHO made every effort.

Future research should look into how health organizations use social media as part of their strategy and look at understanding the benefits and the drawback of implementation of use of latest AI tools and chatbots in combating misinformation. Additionally, scholars should focus on the diffusion speed/rate of health organizations’ messages to better understand the social listening strategies these organizations employ for future health crisis. While the current study employed a content analysis, future studies could use computational methods to calculate diffusion size and speed, in order to understand how quickly sensemaking messages are diffused within the network and better examine health organization’s real-time engagement with the public. This could be done by monitoring and mining analytic data hourly to obtain relative values (see Zhu et al. 2020 for mathematical calculations).

-

Research funding: This research was supported in part by MCOM Summer Research Grant received by the first author.

-

Competing interests: We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

-

Availability of data and material: Will be provided upon request.

-

Code availability: Will be provided upon request.

Text-processing steps for conducting LDA.

| Steps | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Tokenization | First, we split tweets into tokens i.e. breaking the tweets into individual coherent symbols that make up the human language (like words, numbers, etc.). We used the package TweetTokinizer and used Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) library to tokenize the tweets. |

| Removing punctuation | Next, we removed punctuations from all the text. |

| Text conversion | For this step, we converted all the uppercase letters into lower case letters. |

| Removal of web and shortened links | Since tweets often contain web links, we removed the weblinks i.e., http, https, bit.ly along with the website address. Having such irrelevant details can hinder the machine learning process. |

| Stop-word removal | For this step, we took out a list of irrelevant words and symbols within the dataset that might hinder the LDA process. These include articles, pronounces, symbols like @ or hashtags. |

| Lemmatization | This is a process of unification, wherein the words are returned to their base form. For example, the word difficulty would be returned to ‘difficult,” the word breathing is transformed to “breathe.” |

| Relative pruning | In order to improve the quality of the LDA model, we removed frequently occurring words (i.e., words occurring in more than 75 % of the messages) and rare words (i.e., words occurring less than 10 times per data set) as it might affect the probabilistic model and the clustering of topics. |

LDA inductive labels, example tweets.

| Codes | Themes | Example tweets | Example tweets (WHO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1–Jan 24 | |||

|

|

|||

| COVID-19 cases | Sensemaking | “cdc says Chicago woman is second coronavirus case in us #2019ncov #cdc” “Possible first instance of human to human transmission of coronavirus outside of Wuhan this happened in Vietnam” |

“WHO is working with officials in #Thailand and #China following reports of confirmation of the novel #coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in a traveler from #Wuhan, China, who traveled to Thailand |

| Speculations and reasons about the originations and spreading of the virus | Sensemaking | “We seem to have a new emerging infectious disease a #coronavirus seems to be causing the #outbreak of #pneumonia in #china this is from the same family causing #sars and #mers there is probably an #animal source too like #sars and #mers #zoonosis #wuhanpneumonia @bbcworld” | @WHOThailand @WHOSEARO @WHOWPRO WHO reiterates that it is essential that investigations of the novel #coronavirus (2019-nCoV) continue in #China to identify the source of the outbreak and any animal reservoirs or intermediate hosts https://t.co/oTSIsziTly https://t.co/EnyCV5Jo2C |

|

|

|||

| Jan 25–Jan 31 | |||

|

|

|||

| The spread of the virus and blaming China | Sensemaking | “China should be responsible & ground all flights. Ground Zero for #coronavirus means they have a moral obligation to staunch the spreading of this virus.” “map: the spread of new strand of #coronavirus pictwittercom/tgeyagxt6m” | @DrTedros @WHOWPRO @WHOSEARO @pahowho @WHO_Europe @WHOEMRO @WHOAFRO “To the people of #China & to all of those around the who have been affected by this outbreak, we want you to know that the stands with you”-@DrTedros #2019nCoV” |

| Reported cases around the world | Sensemaking | “There are now 60+ cases of #CoronaVirus reported in 22 states now, including Illinois. This outbreak that originated in China is getting insaaaaaaaane.” | @DrTedros @WHOWPRO @WHOSEARO @pahowho @WHO_Europe @WHOEMRO @WHOAFRO There are now 98 #2019nCoV cases in 18 countries outside #China, including 8 cases of human-to-human transmission in four countries: Germany, Japan, Viet Nam and the United States of America-@DrTedros” |

|

|

|||

| Feb 1–Feb 14 | |||

|

|

|||

| Sharing of scientific evidence of the virus | Sensemaking | “#Coronavirus: Largest analysis of #nCoV genomic data to date confirms it originated in bats & shows low heterogeneity. Evidence suggests a hyper-variable ‘hotspot’ suggesting the existence of 2 viral subtypes. Journal of Medical Virology” | @WHOWPRO @WHOSEARO @WHO_Europe @pahowho @WHOEMRO @WHOAFRO Q: Is it safe to receive a letter or a package from China? A: Yes, it is safe. People receiving packages from China are not at risk of contracting #2019nCoV. From previous analysis, we know coronaviruses do not survive long on objects, such as letters or packages. #KnowTheFacts https://t.co/RBBqjkd5JQ” |

| Reporting of cases | Sensemaking | Cases of the new coronavirus hint at the disease’s severity, symptoms and spread SEE DETAILS AT ==> http://SURGICALMASK.vuhere.com #virus #coronavirus #sars #flu #china #trump #Vindman” | “Last week I declared a public health emergency of international concern over the outbreak of #2019nCoV. As of this morning, there are 17,238 confirmed cases in & 361 deaths. Outside, there are 151 confirmed cases in 23 countries; 1 death-@DrTedros https://t.co/JvKC0PTett |

| Questioning Chinese government | Sensemaking | CHINA IS IN FULL COVER-UP MODE. Totally normal response to common flu. The government of China is lying. The citizens know what’s going on, they fear the government more than the coronavirus. #CoronaVirus | @DrTedros “We continue to support the Chinese government’s efforts to address the #2019nCoV outbreak at the epicenter, at the source, in Wuhan. We must not forget how difficult this is for the people of Wuhan”-@DrTedros” |

|

|

|||

| Feb 15–Feb 29 | |||

|

|

|||

| Disinformation videos about China fueling stigma and fear (includes both misinformation tweets and debunking Tweets) | Misinformation | “Rampant ignorance and misinformation about the novel #Coronavirus has led to #racist and #xenophobic attacks against fellow Americans or anyone in the #UnitedStates who looks #Asian.” | @DrTedros @MunSecConf @Facebook @Google @Pinterest @TencentGlobal @Twitter @tiktok_us @YouTube we must be guided by solidarity, not stigma. The greatest enemy we face is not the #coronavirus itself; it’s the stigma that turns us against each other. We must stop stigma and hate!”-@DrTedros at #MSC2020 on #COVID19 https://t.co/BjdmDVzXlE |

| Travel related including information about quarantine of cruise passengers and several people requesting border shut-down | Sensemaking | The Japanese government’s measures against the new coronavirus are too lax. I do not feel much intelligence. Unfortunately, we recommend that foreigners not visit Japan for a while. #coronavirus #COVID2019 | @DrTedros “Of all cases outside #China, over 1/2 are among passengers on the #DiamondPrincess cruise ship. The first passengers have now disembarked, providing they have a negative test, no symptoms and no contact with a confirmed case in the past 14 days”-@DrTedros #COVID19 #coronavirus” |

| Spreading and mitigation behaviors (including misinformation about cures) | Efficacy & misinformation | Alert: Please stop buying any *foreign* food, fruits, vegetables & even other items ! #coronavirus is spreading fast … it has already spread to 28 countries . | @WHOWPRO @WHOSEARO @WHO_Europe @WHOEMRO @WHOAFRO @pahowho FACT: The risk of being infected with the new #coronavirus by touching coins, banknotes, credit cards and other objects, is very low https://t.co/TdKoGmWrIr #COVID19 #KnowtheFacts https://t.co/tYZ6UyQxjT” |

|

|

|||

| March 1–March 7 | |||

|

|

|||

| Covid-19 not as deadly (questioning severity) and spreading of conspiracy | Misinformation | #coronavirus is not as deadly as everybody put out to be more people die from many other things than coronavirus like the flu | “#COVID19 is a serious disease. It is not deadly to most people, but it can kill. We’re all responsible for reducing our own risk of infection, and if we’re infected, for reducing our risk of infecting others.”-@DrTedros #coronavirus” |

| Preventative actions (including canceling of events, travel restrictions, and safety measure) | Efficacy Message | “#coronavirus stay calm and wash your hands” | “It is prudent for travellers who are sick to delay or avoid travel to #COVID19 affected areas, in particular for elderly travellers and people with chronic diseases or underlying health conditions https://t.co/PObUcGlie0 #coronavirus https://t.co/opcTh99n2j” |

|

|

|||

| March 8–March 13 | |||

|

|

|||

| Fatalities and new cases | Sensemaking | “About half of the world’s countries now have cases of covid-19 and the death toll outside china is approaching 700 italian fatalities have now overtaken South Korea’s death count while france banned large gatherings to limit the spread of the #coronavirus” | “More than 132,000 cases of #COVID19 have now been reported to WHO, from 123 countries and territories. 5,000 people have lost their lives, a tragic milestone-@DrTedros #coronavirus” |

| Declaration of pandemic and online transition | Other | “The Los Angeles unified school district will close all schools starting monday march 16 for two weeks due the covid-19 situation #coronavirus #covid19 #lausd #losangeles #lausdteachers #utlastrong” | BREAKING “We have therefore made the assessment that #COVID19 can be characterized as a pandemic-@DrTedros #coronavirus https://t.co/JqdsM2051A” |

|

|

|||

| March 14–March 21 | |||

|

|

|||

| US and UK government’s inaction | Other | “The government are drip-feeding information about #coronavirus to journalists who post it on twitter causing alarm clear official statements please people are anxious #coronauk” | |

| Quarantine, lockdowns and life indoors | Sensemaking | “It’s okay to be confused uncertain anxious or fear your feelings are valid here are things that aren’t cancelled during #coronavirus • nature walk • laughter • music • singing • reading • hope #stayhome #socialdistancing #coronavirusupdate #phdchat #phdlife #femtech | “I’d like to thank @PaulPolman, Ajay Banga & John Denton @iccsecgen for their support and collaboration. WHO is also working with @GlblCtzn to launch the Solidarity Sessions, a series of virtual concerts with leading musicians from around the world-@DrTedros #COVID19” |

| Mitigation behaviors | Efficacy Message | “Let’s do everything we can to keep each other safe #washyourhands cover your #cough or sneeze #clean all common surfaces #stayathome | “Washing your hands will help to reduce your risk of #coronavirus infection. But it’s also an act of solidarity because it reduces the risk you will infect others in your community and around the world. Do it for yourself, do it for others-@DrTedros #COVID19” |

|

|

|||

| March 22–March 30 | |||

|

|

|||

| Politicization of virus (Mostly US based) | Others | “This pandemic is exposing so many politicians as weak corrupt selfish and incapable of true leadership if there is one good thing that comes out of this health crisis i pray for the removal of corruption and greed in our government #coronavirus #usacoronavirus #corruption” | “Solving this problem requires political coordination at the level. I will be addressing heads of state from the G20 countries. I will be asking them to work together to increase production, avoid export bans & ensure equity of distribution on the basis of need-@DrTedros” |

| Cases and testing | Sensemaking | “I’m shocked at the incompetence of our response to #coronavirus here in LA. We need testing sites around the city. Many LA residents do not have a primary physician and/or are unemployed. These people will spread the virus. #LosAngelesLockdown” | To support our call on all countries to conduct aggressive case-finding and testing, we’re also working urgently to massively increase the production and capacity for testing around the world-@DrTedros #COVID19 #coronavirus” |

| Supporting essential workers (including medical, essential businesses) | Others | “Tonight at 8 p.m., let’s applaud the dedication of our health care workers system-wide and around the globe. We thank you for your tireless efforts during the #coronavirus pandemic. Share a photo or video of yourself clapping to show your support for these #HealthCareHeroes.” | Even if we do everything else right, if we don’t prioritize protecting #healthworkers, many people will die because the health worker who could have saved their life is sick-@DrTedros #COVID19 #coronavirus” |

References

Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.Search in Google Scholar

Abd-Alrazaq, Alaa, Dari Alhuwail, Mowafa Househ, Mounir Hamdi & Zubair Shah. 2020. Top concerns of tweeters during the COVID-19 pandemic: Infoveillance study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22(4). e19016.10.2196/19016Search in Google Scholar

Bacsu, Juanita-Dawne, Megan E. O’Connell, Allison Cammer, Mahsa Azizi, Karl Grewal, Lisa Poole, Shoshana Green, Saskia Sivananthan & Raymond J. Spiteri. 2021. Using Twitter to understand the COVID-19 experiences of people with dementia: Infodemiology study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23(2). e26254. https://doi.org/10.2196/26254.Search in Google Scholar

Blei, David M. 2012. Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM 55(4). 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1145/2133806.2133826.Search in Google Scholar

Bode, Leticia & Emily K. Vraga. 2018. See something, say something: Correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health Communication 33(9). 1131–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1331312.Search in Google Scholar

Braun, Virginia & Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2). 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.Search in Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023a. CDC Museum COVID-19 timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html (accessed 23 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023b. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/prevention/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html (accessed 28 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Bin, Jian Shao, Kui Liu, Gaofeng Cai, Zhenggang Jiang, Yuru Huang, Hua Gu & Jianmin Jiang. 2018. Does eating chicken feet with pickled peppers cause avian influenza? Observational case study on Chinese social media during the avian influenza A (H7N9) outbreak. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 4(1). e32. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.8198.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Yingying, Long Jacob, Jungmi Jun, Sei-Hill Kim, Zain Ali & Piacentine Colin. 2023. Anti-intellectualism amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The discursive elements and sources of anti-Fauci tweets. Public Understanding of Science 32(5). 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221146269.Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, John W. & Masaru Nishikawa. 2022. Effects of health literacy in the fight against the COVID-19 infodemic: The case of Japan. Health Communication 37(12). 1520–1533. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2065745.Search in Google Scholar

Chowdhury, Nashit, Ayisha Khalid & Tanvir C. Turin. 2023. Understanding misinformation infodemic during public health emergencies due to large-scale disease outbreaks: A rapid review. Journal of Public Health 31(4). 553–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01565-3.Search in Google Scholar

Coombs, W. Timothy. 2009. Conceptualizing crisis communication. In Robert L. Heath & H. Dan O’Hair (eds.), Handbook of Risk and crisis communication, 99–118. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003070726-6Search in Google Scholar

Colville, Ian, Annie Pye & Mike Carter. 2013. Organizing to counter terrorism: Sensemaking amidst dynamic complexity. Human Relations 66(9). 1201–1223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712468912.Search in Google Scholar

Dailey, Dharma & Kate Starbird. 2015. “It’s Raining Dispersants”: Collective sensemaking of complex information in crisis contexts. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference Companion on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 155–158.10.1145/2685553.2698995Search in Google Scholar

Do Nascimento, Israel Júnior Borges, Ana Beatriz Pizarro, Jussara M. Almeida, Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, Marcos André Gonçalves, Maria Björklund & David Novillo-Ortiz. 2022. Infodemics and health misinformation: A systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 100(9). 544–561. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.21.287654.Search in Google Scholar

Erku, Daniel, Sewunet Belachew, Solomon Abrha, Mahipal Sinnollareddy, Thomas Jackson, Kathryn J. Steadman & Wubshet Tesfaye. 2021. When fear and misinformation go viral: Pharmacists’ role in deterring medication misinformation during the “infodemic” surrounding COVID-19. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 17(1). 1954–1963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.032.Search in Google Scholar

Eysenbach, Gunther. 2020. How to fight an infodemic: The four pillars of infodemic management. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22(6). e21820. https://doi.org/10.2196/21820.Search in Google Scholar

Festila, Alexandra, Polymeros Chrysochou, Sophie Hieke & Camila Massri. 2021. Public sensemaking of active packaging technologies: A feature-based perspective. Public Understanding of Science 30(8). 1024–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625211015830.Search in Google Scholar

Henrique, Jefferson. n.d. A project written in Python to get old tweets which could bypass some limitations of Twitter official API. GitHub. https://github.com/Jefferson-Henrique/GetOldTweets-python (accessed 28 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Hönings, Holger, Daniel Knapp, Bích Châu Nguyễn, Daniel Richter, Williams Kelly, Isabelle Dorsch & Kaja J. Fietkiewicz. 2022. Health information diffusion on Twitter: The content and design of WHO tweets matter. Health Information & Libraries Journal 39(1). 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12361.Search in Google Scholar

Josephson, Alex & Eimear Lambe. 2020. Brand communications in times of crisis. X. https://blog.x.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/Brand-communications-in-time-of-crisis (accessed 28 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Kabir, Md Enamul. 2022. Topic and sentiment analysis of responses to Muslim clerics’ misinformation correction about COVID-19 vaccine: Comparison of three machine learning models. Online Media and Global Communication 1(3). 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1515/omgc-2022-0042.Search in Google Scholar

Kayes, D. Christopher. 2004. The 1996 Mount Everest climbing disaster: The breakdown of learning in teams. Human Relations 57(10). 1263–1284. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267040483.Search in Google Scholar

Kieh, Mark D., Elim M. Cho & Ian A. Myles. 2017. Contrasting academic and lay press print coverage of the 2013-2016 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak. PLoS One 12(6). e0179356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179356.Search in Google Scholar

Kullar, Ravina, Debra A. Goff, Timothy P. Gauthier & Tara C. Smith. 2020. To tweet or not to tweet – a review of the viral power of Twitter for infectious diseases. Current Infectious Disease Reports 22(14). 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-020-00723-0.Search in Google Scholar

Kumble, Sushma, Pratiti Diddi & Steve Bien-Aimé. 2022. “Your strength is inspirational”: How Naomi Osaka’s Twitter announcement destigmatizes mental health disclosures. Communication & Sport 0(0). 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221124584.Search in Google Scholar

Lachlan, Kenneth A., Patric R. Spence, Xialing Lin, Kristy Najarian & Maria Del Greco. 2016. Social media and crisis management: CERC, search strategies, and Twitter content. Computers in Human Behavior 54. 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.027.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Katharine & Julie Barnett. 2020. “Will polar bears melt?” A qualitative analysis of children’s questions about climate change. Public Understanding of Science 29(8). 868–880. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520952999.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Juan, Carrie Reif-Stice & Bruce Getz. 2022. The mediating role of comments’ credibility in influencing cancer cure misperceptions and social sharing. Online Media and Global Communication 1(3). 551–579. https://doi.org/10.1515/omgc-2022-0033.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Hang, Haoran Chu & Yanni Ma. 2021. Experience, experts, statistics, or just science? Predictors and consequences of reliance on different evidence types during the COVID-19 infodemic. Public Understanding of Science 30(5). 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625211009685.Search in Google Scholar

Lwin, May O., Jiahui Lu, Anita Sheldenkar & Peter J. Schulz. 2018. Strategic uses of Facebook in Zika outbreak communication: Implications for the crisis and emergency risk communication model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(9). 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091974.Search in Google Scholar

Maitlis, Sally & Marlys Christianson. 2014. Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. The Academy of Management Annals 8(1). 57–125. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.873177.Search in Google Scholar

Medford-Davis, Laura N. & G. Bobby Kapur. 2014. Preparing for effective communications during disasters: Lessons from a World Health Organization quality improvement project. International Journal of Emergency Medicine 7(15). 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1865-1380-7-15.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Ann Neville, Chad Collins, Lindsay Neuberger, Andrew Todd, Timothy L. Sellnow & Laura Boutemen. 2021. Being first, being right, and being credible since 2002: A systematic review of crisis and emergency risk communication (CERC) research. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research 4(1). 1–27. https://doi.org/10.30658/jicrcr.4.1.1.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Michele, Tanvi Banerjee, Roopteja Muppalla, William Romine & Amit Sheth. 2017. What are people tweeting about Zika? An exploratory study concerning its symptoms, treatment, transmission, and prevention. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 3(2). e7157. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.7157.Search in Google Scholar

Oyeyemi, Sunday Oluwafemi, Elia Gabarron & Rolf Wynn. 2014. Ebola, Twitter, and misinformation: A dangerous combination? BMJ 349. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6178.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Hyojung, Bryan H. Reber & Myoung-Gi Chon. 2016. Tweeting as health communication: Health organizations’ use of Twitter for health promotion and public engagement. Journal of Health Communication 21(2). 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1058435.Search in Google Scholar

Rehurek, Radim & Sojka, Petr. 2011. Gensim—statistical semantics in python. Org. Retrieved from genism.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Barbara & Sandra Crouse Quinn. 2008. Effective communication during an influenza pandemic: The value of using a crisis and emergency risk communication framework. Health Promotion Practice 9(4 Suppl.). 13S–17S. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399083252.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Barbara & Matthew W. Seeger. 2005. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication 10(1). 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730590904571.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Barbara & Matthew W. Seeger. 2014. Crisis and emergency risk communication. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ppt/cerc_2014edition_Copy.pdf (accessed 28 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Röder, Michael, Andreas Both & Alexander Hinneburg. 2015. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. Proceedings of the eighth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining, Shanghai, China, 399–408. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2684822.2685324.10.1145/2684822.2685324Search in Google Scholar

Salminen, Joni, Vignesh Yoganathan, Juan Corporan, Bernard J. Jansen & Soon-Gyo Jung. 2019. Machine learning approach to auto-tagging online content for content marketing efficiency: A comparative analysis between methods and content type. Journal of Business Research 101. 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.018.Search in Google Scholar

Seeger, Matthew, Barbara Reynolds & Ashleigh M. Day. 2020. Crisis and emergency risk communication: Past, present, and future. In Frandsen Finn & Johansen Winni (eds.), Crisis communication, 401–418. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110554236-019Search in Google Scholar

Sellnow, Timothy L. & Matthew W. Seeger. 2013. Theorizing crisis communication. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwel.Search in Google Scholar

Sievert, Carson & Kenneth E. Shirley. 2014. LDAvis: A method for visualizing and interpreting topics. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, 63–70.10.3115/v1/W14-3110Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, Margaret C. & Cory Young. 2018. Revisiting STREMII: Social media crisis communication during Hurricane Matthew. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research 1(2). 279–301. https://doi.org/10.30658/jicrcr.1.2.5.Search in Google Scholar

Tan, Zachary & Anwitaman Datta. 2023. The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic through the lens of r/Coronavirus subreddit: An exploratory study. Health and Technology 13(2). 301–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-023-00734-6.Search in Google Scholar

Tangcharoensathien, Viroj, Neville Calleja, Tim Nguyen, Tina Purnat, Marcelo D’Agostino, Sebastian Garcia-Saiso, Mark Landry, Arash Rashidian, Clayton Hamilton, Abdelhalim AbdAllah, Ioana Ghiga, Alexandra Hill, Daniel Hougendobler, Judith van Andel, Mark Nunn, Ian Brooks, Pier Luigi Sacco, Manlio De Domenico, Philip Mai, Anatoliy Gruzd, Alexandre Alaphilippe & Sylvie Briand. 2020. Framework for managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Methods and results of an online, crowdsourced WHO technical consultation. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22(6). e19659. https://doi.org/10.2196/19659.Search in Google Scholar

Thygesen, Hilde, Tore Bonsaksen, Mariyana Schoultz, Mary Ruffolo, Janni Leung, Daicia Price & Amy Østertun Geirdal. 2021. Use and self-perceived effects of social media before and after the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-national study. Health and Technology 11(6). 1347–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-021-00595-x.Search in Google Scholar

Tomasi, Stella, Sushma Kumble, Pratiti Diddi & Neeraj Parolia. 2023. The framing of initial COVID‐19 communication: Using unsupervised machine learning on press releases. Business and Society Review 128(3). 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12323.Search in Google Scholar

Troy, Cassandra L. C., Juliet Pinto & Zheng Cui. 2022. Managing complexity during dual crises: Social media messaging of hurricane preparedness during COVID-19. Journal of Risk Research 25(11-12). 1458–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2022.2116086.Search in Google Scholar

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. CERC: Crisis + Emergency Risk Communication. https://web.archive.org/web/20200518215809/https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ppt/CERC_Introduction.pdf (accessed 23 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Valiavska, Anna & Sarah Smith-Frigerio. 2023. Politics over public health: Analysis of Twitter and Reddit posts concerning the role of politics in the public health response to COVID-19. Health Communication 38(11). 2271–2280. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2063497.Search in Google Scholar

Veil Shari, Barbara Reynolds, Timothy L. Sellnow & Matthew W. Seeger. 2008. CERC as a theoretical framework for research and practice. Health Promotion Practice 9(4_suppl). 26S–34S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839908322113.Search in Google Scholar

Vijaykumar, Santosh, Glen Nowak, Itai Himelboim & Yan Jin. 2018. Virtual Zika transmission after the first US case: Who said what and how it spread on Twitter. American Journal of Infection Control 46(5). 549–557.10.1016/j.ajic.2017.10.015Search in Google Scholar

Vos, Sarah C. & Marjorie M. Buckner. 2016. Social media messages in an emerging health crisis: Tweeting bird flu. Journal of Health Communication 21(3). 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1064495.Search in Google Scholar

Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy & Sinan Aral. 2018. The spread of true and false news online. Science 359(6380). 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559.Search in Google Scholar

Vraga, Emily K. & Leticia Bode. 2018. I do not believe you: How providing a source corrects health misperceptions across social media platforms. Information, Communication & Society 21(10). 1337–1353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1313883.Search in Google Scholar

Weick, Karl E. 1988. Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies 25(4). 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00039.x.Search in Google Scholar

Weick, Karl E. 1995. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Weick, Karl E. & Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. 2006. Mindfulness and the quality of organizational attention. Organization Science 17(4). 514–524. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0196.Search in Google Scholar

Weick, Karl E., Kathleen M. Sutcliffe & David Obstfeld. 2005. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science 16(4). 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0133.Search in Google Scholar

Wheeler, Jordan M., Shiyu Wang & Allan S. Cohen. 2024. Latent Dirichlet Allocation of constructed responses. In Mark D. Shermis & Joshua Wilson (eds.), The Routledge international handbook of automated essay evaluation, 535–555. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003397618-31Search in Google Scholar

World Health Organization. 2021. WHO launches pilot of AI-powered public-access social listening tool. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-launches-pilot-of-ai-powered-public-access-social-listening-tool (accessed 23 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

World Health Organization. n.d. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 29 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Xue, Jia, Junxiang Chen, Chen Chen, Chengda Zheng, Sijia Li & Tingshao Zhu. 2020. Public discourse and sentiment during the COVID 19 pandemic: Using latent Dirichlet allocation for topic modeling on Twitter. PLoS One 15(9). e0239441. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239441.Search in Google Scholar

Zarocostas, John. 2020. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 395(10225). 676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X.Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, Xun, Youllee Kim & Haseon Park. 2020. Do messages spread widely also diffuse fast? Examining the effects of message characteristics on information diffusion. Computers in Human Behavior 103. 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.006.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Research Articles

- Comparative analysis of AI attitudes among JMC students in Brazil and the US: a mixed-methods approach

- Digital technology races between China and the US: a critical media analysis of US media coverage of China’s rise in technology and globalization

- Framing Huawei: from the target of national debate to the site of international conflict in Canada’s mainstream online newspaper

- “We are no scapegoat.”: analyzing community response to legislative targeting in U.S. Texas State Senate bill 147 discourse on Twitter (X)

- Displaying luxury on social media: Chinese university students’ perception of identity, social status, and privilege

- Understanding content dissemination on sensemaking: WHO’s social listening strategy on X during the initial phase of COVID-19

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Russian TV channels and social media in the transformation of the media field

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Research Articles

- Comparative analysis of AI attitudes among JMC students in Brazil and the US: a mixed-methods approach

- Digital technology races between China and the US: a critical media analysis of US media coverage of China’s rise in technology and globalization

- Framing Huawei: from the target of national debate to the site of international conflict in Canada’s mainstream online newspaper

- “We are no scapegoat.”: analyzing community response to legislative targeting in U.S. Texas State Senate bill 147 discourse on Twitter (X)

- Displaying luxury on social media: Chinese university students’ perception of identity, social status, and privilege

- Understanding content dissemination on sensemaking: WHO’s social listening strategy on X during the initial phase of COVID-19

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Russian TV channels and social media in the transformation of the media field