Abstract

While conventional optical sensors hold historical significance, they face inherent limitations in sensitivity, operational intricacies, and bulky size. A breakthrough in this realm comes from the advent of metasurface sensors, which leverage nanoscale optical effects, thereby expanding the horizons of optical sensing applications. However, past methods employed in metasurface sensors predominantly rely on wavelength shifts or intensity changes with high-Q resonances, thereby significantly restricting the detection bandwidth. In response to these challenges, this study introduces a plasmonic gradient metasurface-based sensor (PGMS) designed for refractive index detection across a wide wavelength spectrum. Through the utilization of the Pancharatnam–Berry phase method, the PGMS achieves a distinctive 2π phase shift, facilitating the simultaneous generation of specular and deflected beams. The introduction of a far-field intensity ratio (I* = I +1/I 0) amplifies the change in optical response by maximizing the deflected beam’s intensity while minimizing specular reflection. Experimental validation attests to the PGMS’s consistent performance across diverse media and wavelengths, successfully overcoming challenges associated with oxidation issues. Furthermore, the incorporation of a normalization factor enhances the PGMS’s sensing performance and versatility for broadband optical sensing, accommodating variations in the refractive index. Particularly sensitive in green wavelengths, the PGMS demonstrates its potential in visible spectrum applications, such as biomedical diagnostics and environmental monitoring. This research not only addresses challenges posed by conventional sensors but also propels optical sensing technologies into a realm of heightened sensitivity and adaptability.

1 Introduction

Traditional optical sensors have historically played a crucial role in the fields of science and engineering, offering precise measurement capabilities and widespread applicability. However, they do come with inherent limitations, including sensitivity constraints to minute variations and challenges when deployed in complex environments. Moreover, they often necessitate bulky equipment or intricate optical setups, resulting in increased costs and operational complexity. In response to these limitations, metasurface sensors have emerged. These sensors leverage nanoscale optical effects by fine-tuning the design of meta-atoms, granting them exceptional flexibility and tunability [1]–[3]. Consequently, metasurface sensors represent a significant technological breakthrough, expanding the application horizons of optical sensing.

Metasurface sensors possess substantial application value and significance across a multitude of fields today. They harness nanophotonic resonances and phenomena within metals and high-index semiconductors, merging the realms of optics and electronics to achieve exceptional sensitivity in spectral reconstruction [4], [5], polarization detection [6], [7], depth and edge characterization [8]–[10], and molecular fingerprint retrieval [11]. Their impact extends to contemporary domains such as science, medicine, environmental monitoring, and information technology. Notably, the application of metasurface sensors in refractive index detection [12], [13] and the biomedical sector [11], [14], [15] holds particular significance. These sensors enable the detection of minute concentrations of biomolecules [16], offering substantial potential for early drug screening and advancements in biomedical research [17]. Moreover, metasurface sensors provide real-time [18], [19], label-free sample analysis [20], supplying vital tools for clinical diagnostics and epidemic surveillance [21].

Within the domain of metasurface sensors for refractive index detection, two fundamental scenarios are in play. The first scenario centers on the resonant wavelength shift when nanostructures are placed in different media [22]–[24]. To observe these shifts in resonant wavelengths clearly, it is crucial for the designed nanostructures to have a relatively high quality factor (Q factor) in the optical spectra [25]–[27]. Indeed, a high Q factor not only aids in this observation but also enhances the figure of merit (FOM) [28]–[30], subsequently improving sensing performance. The development and optimization of resonant meta-atoms, including specific resonant modes like Mie resonances [31]–[33], toroidal modes [34]–[36], and non-radiative anapole modes [37], [38], have enabled strong near-field enhancement and confinement. This innovative approach has the potential to significantly enhance sensitivity when detecting changes in refractive index. Notably, these resonances often exhibit a relatively high Q factor, further contributing to their effectiveness in sensing applications. However, it is important to note that refractive index detection based on wavelength shifts can introduce measurement errors, especially when the medium to be detected exhibits high dispersion within the working bandwidth. The second scenario involves detecting changes in refractive index by characterizing optical intensity at a fixed wavelength [39]–[41]. Consequently, measurement accuracy is higher for dispersive media. Nevertheless, to enhance the intensity difference for different media, the resonant feature must, once again, possess a relatively high Q factor [42]. The requirement for a high Q factor is less desirable when the goal is to expand the working bandwidth of metasurface sensors, which applies to both of the abovementioned approaches.

Previous research has delved into the development of broadband metasurface sensors employing high Q factor nanostructures. For instance, in order to discern the unique signatures of biomolecules across a wide range of wavelengths, scientists have employed a strategy that involves interleaving metasurface chips [14], [16], [43]. Each individual chip is designed to perform sensing at a specific wavelength. Nonetheless, the approach of using interleaved metasurfaces has the potential to increase the device’s footprint, thereby sacrificing one of the key advantages of compact dimensions associated with metasurfaces. While designing metasurfaces with multi-resonant features [44] or angle-dependent response [11] is a practical approach for broadband sensing, the specific requirements for spectral response can complicate the optimization process of the metasurface [45]. Thus, the challenge of striking a balance between sensitivity enhancements and working bandwidth remains an ongoing concern that researchers are actively addressing as they strive to achieve the optimal performance of metasurface sensors.

In this study, we propose and experimentally present a plasmonic gradient metasurface-based sensing platform capable of refractive index detection across a wide spectrum of wavelengths (refer to Figure 1A for the conceptual schematic). The incorporation of a phase gradient facilitates the generation of both specular and deflected beams in the far field, providing multiple parameters for signal detection and analysis. To achieve a 2π phase modulation across a wide wavelength spectrum, we employ the Pancharatnam–Berry (PB) phase method in the construction of the gradient metasurface. In our quest to bolster detection sensitivity, we introduce a figure of merit defined as the far-field intensity ratio I* of the specular and deflected beams: I* = I

+1/I

0. This approach amplifies the change in optical response by maximizing the intensity of the deflected beam (I

+1) while minimizing the specular reflection intensity (I

0). In conjunction with the plasmonic resonant characteristics and phase gradient response, this method ensures high sensitivity throughout the visible wavelength range, as assessed by evaluating the normalized intensity ratio

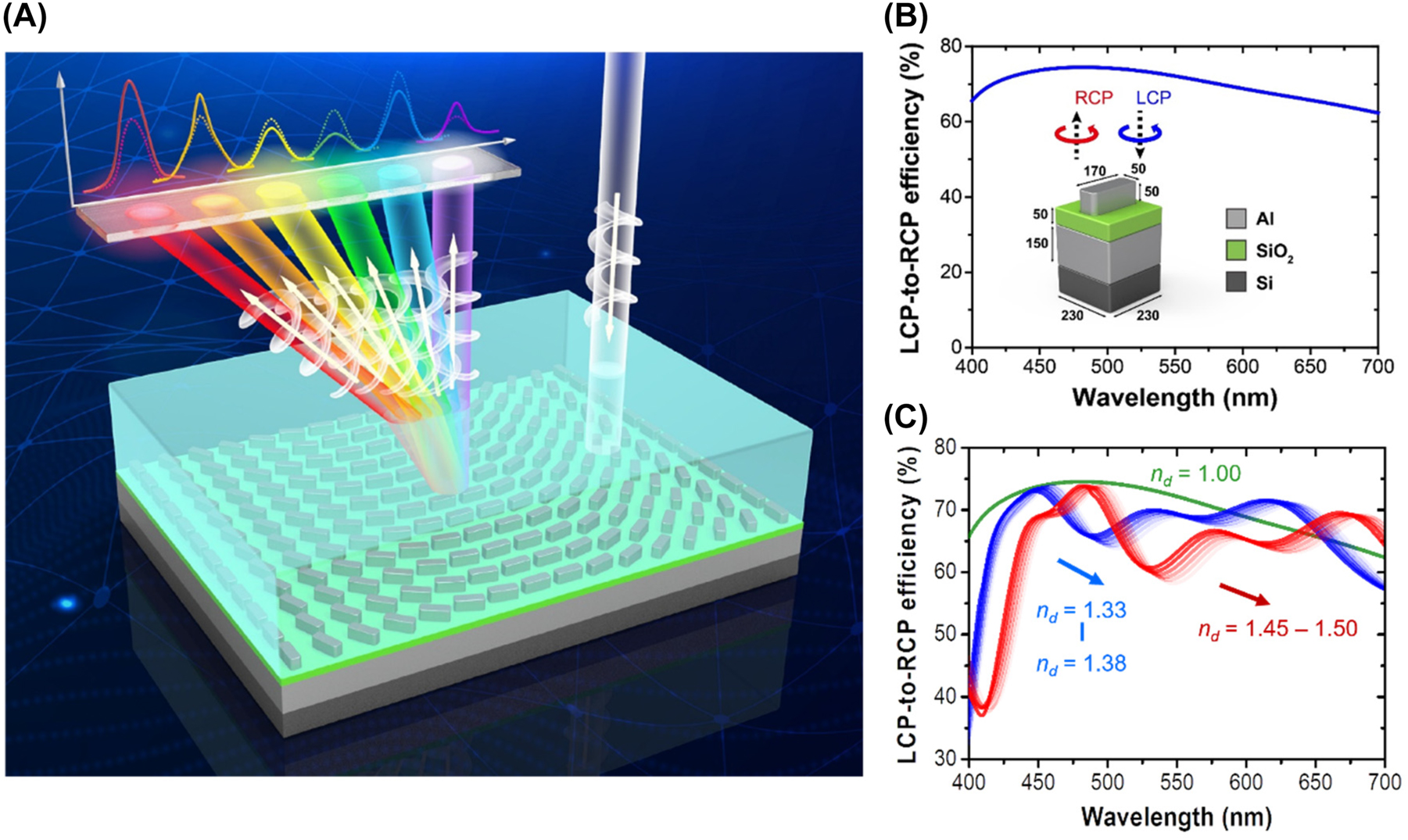

Design for the Al-based meta-atom of the PGMS. (A) A schematic illustration demonstrates the refractive index sensing mechanism utilizing a plasmonic gradient metasurface-based sensor. Variations in the environmental refractive index are observed to alter the intensity of the deflected beam (I +1), thereby offering a pathway for material characterization. This sensor allows the detection of optical responses at various wavelengths within the same image plane. (B) The simulated LCP-to-RCP conversion efficiency of the Al meta-atom. Inset: the geometric dimensions of designed meta-atom (unit: nm). (C) Simulated circular-polarized conversion efficiency of the meta-atom within its surrounding environment is examined across a range of refractive indices n d.

2 Results and discussion

Figure 1B shows the simulated circular cross-polarized reflection spectrum of the proposed plasmonic meta-atom for the PGMS, with the inset highlighting the optimized physical dimensions of the meta-atom. Notably, the plasmonic meta-atom exhibits a polarization conversion efficiency exceeding 60 % across the spectral range from 400 to 700 nm. Before delving into the practicality of optical sensing using gradient metasurfaces, our initial focus is on investigating the optical response of the plasmonic meta-atom in various surrounding environments. It is important to emphasize that while achieving broadband high conversion efficiency is advantageous for high-performance metasurface components and devices, it is less suitable for sensing applications across a wide spectrum. As shown in Figure 1C, the characteristics of the circular cross-polarized spectrum undergo a significant transformation, shifting from a relatively broad high reflection to multiple peaks and dips as the environmental refractive index varies from 1 to 1.33. These variations result from the diverse strengths of magnetic resonances, which, in turn, are a consequence of the dipole-dipole coupling between the topmost meta-atom and the back reflector (see Supporting Information for field profiles). This striking variation presents a challenge when attempting to distinguish resonant peak shifts, especially for those who prefer to rely on wavelength shifts as the figure of merit for sensing. Although there is a substantial intensity difference at certain wavelengths, the reflection intensity remains almost constant at multiple spectral positions. This minimal intensity variation complicates the task of achieving broadband optical sensing. When the changes in the environmental refractive index are relatively small, such as within the range of 1.33–1.38 or from 1.45 to 1.5, the spectral features remain relatively stable. Nevertheless, a slight change in the resonant wavelength shift (or intensity change at a fixed wavelength) is still noticeable at several spectral positions. These findings highlight that highly-reflective broadband meta-atoms may not be the most suitable option for creating effective broadband metasurface sensors.

To enhance the optical sensing performance across the entire visible spectrum, we have proposed the utilization of a plasmonic gradient metasurface as the sensing platform. In this study, the PB phase method is employed to achieve a 2π phase shift within a supercell, and this choice is motivated by two key reasons. Firstly, the PB phase offers a highly promising solution due to its dispersionless property, making it effective in generating beam deflection across a wide frequency range. Secondly, by relying on the structural orientation angle for realizing the phase shift with the PB phase method, we can maintain the high reflection characteristics of the designed meta-atom when using it to construct the gradient metasurface. Based on PB phase theory, the 2θ phase shift of the cross circularly-polarized component can be attained by rotating the nanostructure with an orientation angle θ. In fact, the phase shift linked to the orientation angle can be expressed in the circular basis using the Jones matrix as:

where J LL, J LR, J RL, and J RR represent the conversion coefficient of different components. E r and E i represent the reflected electric field and incident electric field, respectively. LCP and RCP is denoted for left-handed circular polarization and right-handed circular polarization, respectively. More details and discussions can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

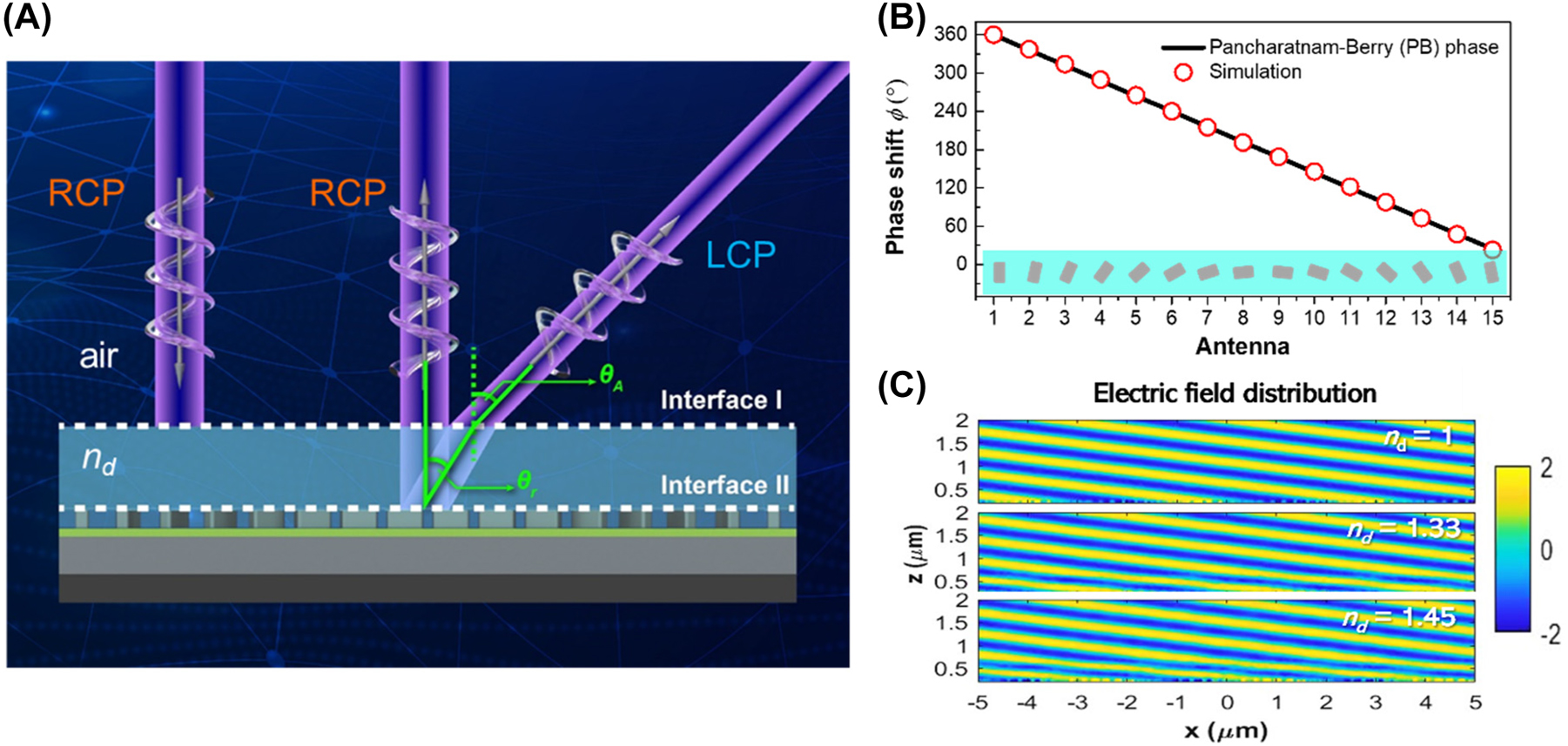

When incident light carries RCP and interacts with the PB phase-based gradient metasurface, two distinct beams are generated in the far field: the co-polarized specular reflection and cross-polarized deflection, as schematically illustrated in Figure 2A. Please note that an identical optical response can be achieved when the incident light is in LCP. The only variation lies in the deflected angle, which shifts to the opposite side relative to the normal vector of the substrate. As a result, the PGMS consistently operates effectively under the condition of circularly-polarized illumination. Despite the reflected and deflected beams exhibiting orthogonal polarization states, their simultaneous differentiation in a single-shot imaging acquisition is facilitated by the wide range of scattering angles. This eliminates the need for a polarizer or imaging device. Moreover, the concurrent generation of two beams in reflection offers additional degrees of freedom as indicators for sensing applications. In fact, the deflected angle θ r for a gradient metasurface at interface I (refer to Figure 2A) can be described by [46]–[48]:

where λ

0 is the working wavelength in free space, n

d is the refractive index of the medium to be detected, and

Working mechanism of the PGMS. (A) The schematic illustration of refractive index sensing within an analyzed medium (light blue region) with refractive index represented as n d. When RCP light is incident, it results in the simultaneous generation of spectral reflection with RCP and a deflected beam with LCP light. (B) Simulated phase shift across one supercell of the plasmonic gradient metasurface. (C) Simulated electric-field distribution (LCP component) of the PGMS within a medium with varying refractive indices. Incident wavelength: 532 nm.

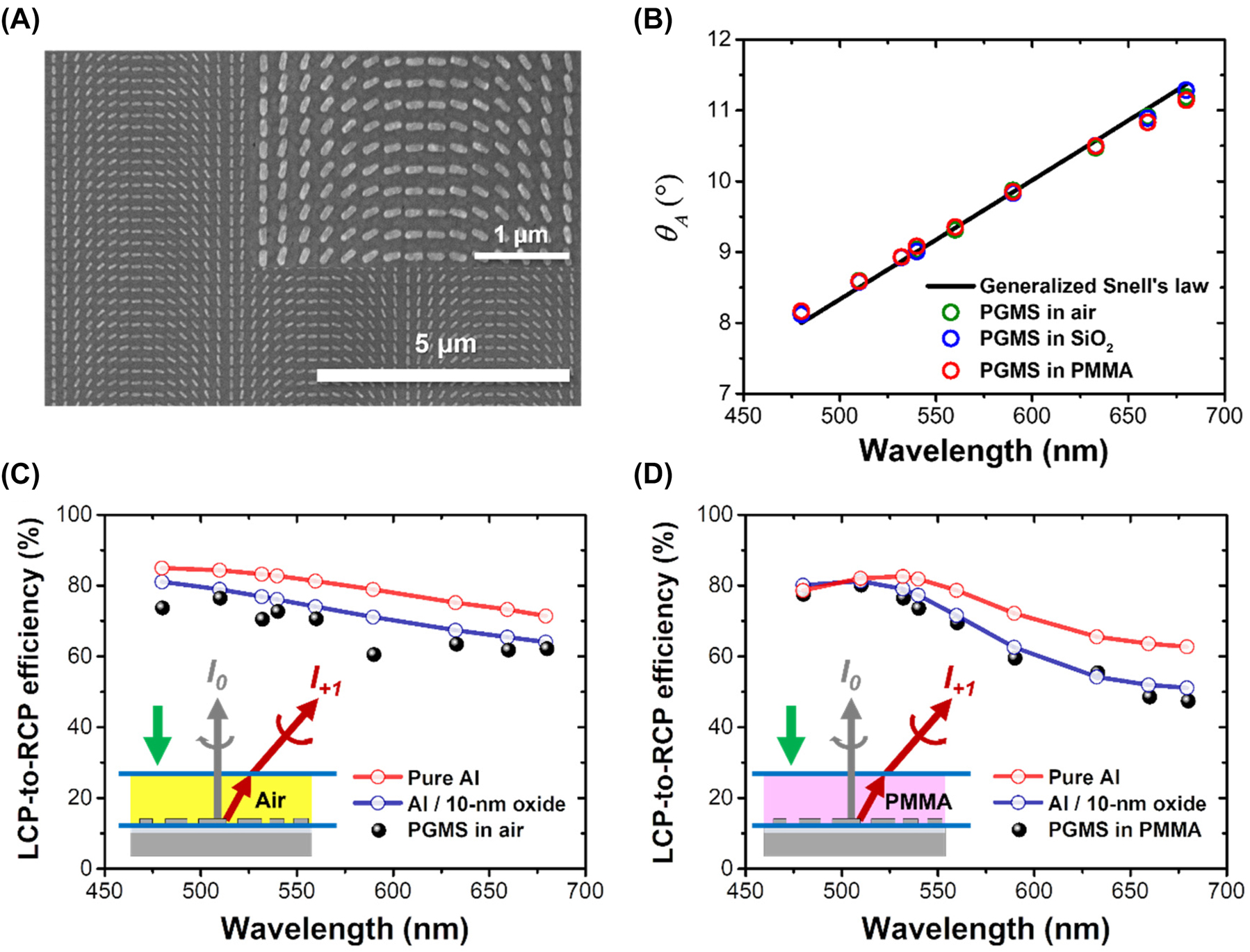

Next, we fabricated an Al-based PGMS using a standard electron beam lithography process (refer to Section 4 for more details). We then implemented experimental characterization to assess its optical performance, specifically examining the deflected angle in different surrounding media and the efficiency of deflection. Due to the limitations of the acousto-optic tunable filter utilized in our study, we conducted experiments within the wavelength range of 480–680 nm. Figure 3A presents the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the fabricated PGMS, showing uniformity and precision in both physical shape and dimensions. The optical setup employed for characterization is illustrated in Figure S1. In Figure 3B, the measured deflected angle of the PGMS sample is plotted based on captured images at various wavelengths. Importantly, these measurements closely align with the theoretically predicted values, offering robust confirmation that the deflected angle remains remarkably consistent even when the PGMS is covered by different media, despite the occurrence of the oxidation issue with the Al nanostructures. This alignment serves to validate the earlier discussions and underscores the resilience of the PGMS in maintaining its optical performance under varying conditions. To experimentally characterize the beam deflection efficiency, we spatially integrated the intensity of incident beam spots within a fixed range by replacing the PGMS with a silver mirror in the optical setup (see Figure S1) as the reference. By evaluating the deflected beams through integrating the light intensity in captured images from Figures 4A and S8, the measured beam deflection efficiency can be calculated using the intensity ratio of deflected to incident beams. The comparison of simulated and measured optical deflection efficiency in free space is provided in Figure 3C. Clearly, there is a noticeable misalignment between the experimental values (black dots) and the simulated values using the bare Al nanostructure in simulations (red circles). This discrepancy is attributed to the oxidation issue in the fabricated Al-based PGMS. To address this, we implemented simulations considering a 10 nm-thick oxidation layer covering the meta-atoms. As depicted, the simulated deflection efficiency with this additional oxidation layer demonstrates closer values and a similar trend to the experimental results, supporting the earlier assumption. To delve deeper into the analysis, Figure 3D shows the measured and simulated beam deflection efficiency for the PGMS covered by a layer of PMMA photoresist. Similarly, the observed experimental trend closely mirrors the simulated results when considering a 10 nm-thick oxidation layer. Experimental and simulated outcomes for the PGMS covered by SiO2 are detailed in Figure S2. Figure S3 provides the refractive index values of PMMA photoresist and SiO2 used in simulations, which are measured using an ellipsometer. Despite a decline in beam deflection efficiency in real samples due to the oxidation issue, the sensitivity of the plasmonic gradient metasurface as an optical sensor remains relatively high. This is attributed to the spectral reflection intensity remaining low, as elaborated in the subsequent paragraph.

Experimental verification of the fabricated PGMS. (A) Top-view SEM images of the Al-based plasmonic gradient metasurface. (B) Angle of deflected beam as a function of the incident wavelength within the visible range as meta-sensor embedded in different surrounding environment. Color circles: measurement. (C, D) Simulated (red and blue circles) and measured (black dots) circular cross-polarization conversion efficiency as the PGMS embedded in (C) air and (D) PMMA.

Sensing performance of the fabricated PGMS. (A) The far-field light intensity distributions at wavelengths of 532 nm and 633 nm for the PGMS when it is covered by different materials. (B, C) The simulated and measured normalized intensity ratios

Lastly, we investigate how the surrounding environment affects the functionality of our PGMS platform. In Figure 4A, the measured scattered images at 532 nm and 633 nm are presented when the PGMS is covered by various media (refer to Figure S4 for additional results). Once again, it is evident that the angle of the deflected beam for the same wavelength remains constant even when the analyte layer is altered. Moreover, leveraging the physical characteristics of the gradient metasurface, the intensity of specular reflection I 0 and deflected light I +1 can be simultaneously obtained without the need for any polarizer or spectrometer. This is achieved by spatially integrating the intensity of captured images within a fixed range depending on the working wavelength. One can see that I 0 consistently registers a lower value than I +1 for all wavelengths, highlighting the high operational efficiency of the proposed plasmonic gradient metasurface for broadband beam deflection. Moreover, there is a discernible difference between both I 0 and I +1 at the same wavelength when the surrounding environment undergoes changes. While this observation suggests that I 0 and I +1 can serve as indicators for optical sensing, the relatively small fluctuations in scattered intensity impede the optimal sensing performance of the PSMG.

To enhance the sensing performance of the PSMG, we introduce a figure of merit defined by the scattered intensity ratio, denoted as I* = I

+1/I

0. The design of the PSMG aims to minimize I

0 and maximize I

−1, consequently substantially boosting the detected FOM. For a fair comparison, given the relatively smaller index of SiO2, we introduce the normalized intensity ratio

where

where ∆n d represents the refractive index change. The numerical and experimental sensitivity as functions of incident wavelength are provided in Figure 4D. The similar spectral features observed in both measurement and simulation affirm the high sensing performance of the PGMS within the visible spectral range. The peak sensitivity is observed in the green wavelengths, can be attributed to the occurrence of the highest deflection efficiency within the same region. While the sensitivity values in the red region may appear relatively lower, they still consistently range between ∼10 and ∼700. These demonstrations affirm that the developed PGMS is exceptionally well-suited for broadband sensing in the visible spectrum.

3 Conclusions

In summary, our investigation introduces an innovative refractive index detection platform based on a plasmonic gradient metasurface that operates seamlessly across a broad range of wavelengths. Leveraging the PB phase method, our PGMS achieves a 2π phase shift within a supercell, paving the way for the generation of both specular and deflected beams in the far field. The PGMS emerges as a versatile and highly sensitive solution, with the introduction of the far-field intensity ratio I* (defined as I +1/I 0) serving as a key performance metric. This metric strategically enhances the optical response by maximizing the intensity of the deflected beam I +1 while minimizing specular reflection I 0. Experimental validations reinforce the robustness of the PGMS across various media and wavelengths, addressing challenges posed by oxidation issues in the Al nanostructures. The incorporation of a normalization factor further amplifies the PGMS’s adaptability for broadband optical sensing, enabling nuanced intensity variations with changes in the refractive index of the surrounding environment. The PGMS’s efficacy is underscored by its notable sensitivity, reaching peak performance in the green wavelengths. Even in regions with relatively diminished sensitivity values, spanning from ∼10 to ∼700 in the red spectrum, the PGMS consistently delivers reliable performance. While the smallest detected index change in this study is ∼0.028, we anticipate that the PGMS’s high sensitivity, particularly for green wavelengths, suggests the potential for detecting even smaller refractive index changes. Considering the dependence of our proposed metasurface on the gap plasmon configuration, a potential concern arises where the intensified plasmon field might leakage into the dielectric spacer, thereby diminishing sensitivity. An alternative strategy is to reconsider the optimization of the meta-atom. A slight increase in the dielectric spacer could result in a minor reduction in beam deflection efficiency, promoting a more noticeable exposure of the enhanced field into free space and potentially amplifying sensitivity. Another plausible avenue involves incorporating alternative multipolar resonances characterized by higher field confinement, such as toroidal modes and non-radiating anapole modes [49]–[51]. It is noteworthy that the sensing mechanism proposed can also be implemented using all-dielectric metasurfaces. The comparatively lower optical losses in high-index metasurfaces render them more suitable for optical applications in transmission, such as bio-sensing and bio-imaging [52], [53]. Nevertheless, the relatively challenging fabrication process of all-dielectric metasurfaces presents difficulties in sample preparation. Consequently, researchers often choose to employ plasmonic metasurfaces for optical applications in reflection, while reserving dielectric metasurfaces for transmission applications. In addition, we would like to point out that detecting refractive index changes in solutions with absorption remains achievable using the proposed PGMS platform. This is contingent upon the measurability of the intensities of both the specular and deflected beams through the optical setup. As shown in Figure S7, the cross-polarized conversion efficiency undergoes a noticeable decline with an increasing extinction coefficient (k). Conversely, the co-polarized intensity maintains consistency across different extinction coefficients. Despite a decrease in the intensity ratio between the LCP-to-RCP efficiency (deflected beams) and LCP-to-LCP reflection (specular beams) due to heightened absorption in the detected material, which reduces the sensitivity of the metasurface, the PGMS still facilitates refractive index detection for absorbing materials owing to the discernible intensities of both specular and deflected beams. These findings accentuate the PGMS’s potential for diverse applications in broadband sensing, such as biomedical diagnostics and environmental monitoring, within the visible spectrum. In addition to its application for refractive index sensing, the proposed PGMS platform is proficient in detecting chiral molecules. Leveraging the intrinsic property of the PB phase-based gradient metasurface, both LCP and RCP deflected beams can be simultaneously obtained when the incident light is linearly polarized. This capability allows the PGMS to detect circular dichroism in real time, revealing the versatility of the PGMS for various sensing applications. Beyond overcoming the limitations of traditional optical sensors, the developed PGMS charts a path toward advanced and highly sensitive optical sensing technologies in the foreseeable future.

4 Methods

4.1 Simulation

All simulation results were conducted using the commercial software CST Microwave Studio. For the calculation of the single meta-atom design, a unit cell boundary condition was applied along the x-direction and y-direction to simulate reflection and phase shift in an array structure. Similarly, beam deflection was simulated using the unit cell boundary condition along the x-direction and y-direction. The refractive indices of SiO2 and PMMA were determined through ellipsometry measurements. The permittivity of Al in the visible regime is characterized by the Drude model.

4.2 Fabrication

To begin, a 180-nm-thick layer of photoresist (PMMA A4) was spin-coated onto a pre-prepared silicon substrate, which was then baked on a hot plate at 180 °C for 3 min. Next, we employed electron beam lithography (Elionix ELS-7500EX) with an acceleration voltage of 50 keV and a beam current of 50 nano-amperes to define the nanopatterns on the photoresist. This was followed by a development process using the PMMA developer (MIBK:IPA = 1:3) for 2 min. Subsequently, a 50-nm-thick layer of Al was deposited via thermal evaporation at a rate of 1.0 Å/s. After a 24-h acetone treatment in the lift-off process, the meta-atoms were determined.

Supplementary information

See Supplementary Material for the supporting content.

Funding source: Center for Quantum Frontiers of Research & Technology (QFort)

Funding source: Ministry of Education, Taiwan

Award Identifier / Grant number: Yushan Fellow Program

Funding source: Core Facility Center, NCKU

Award Identifier / Grant number: Electron beam lithography system

Funding source: National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan

Award Identifier / Grant number: 111-2112-M-006-022-MY3

Award Identifier / Grant number: 111-2124-M-006-003

Award Identifier / Grant number: 112-2124-M-006-001

Award Identifier / Grant number: 112-2731-M-006-001

Acknowledgments

P.C.W. acknowledges the Yushan Fellow Program by the MOE, Taiwan for the financial support. The research is also supported in part by Higher Education Sprout Project, Center for Quantum Frontiers of Research & Technology (QFort) at NCKU.

-

Research funding: The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of advanced focused ion beam system (EM025200) of NSTC 112-2731-M-006-001 and electron beam lithography system belonging to the Core Facility Center of National Cheng Kung University (NCKU). The authors also acknowledge the support from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (Grant number: 111-2112-M-006-022-MY3; 111-2124-M-006-003; 112-2124-M-006-001), and in part from the Higher Education Sprout Project of the Ministry of Education (MOE) to the Headquarters of University Advancement at NCKU.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

-

Data availability: Data underlying the results of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] P. Lalanne and P. Chavel, “Metalenses at visible wavelengths: past, present, perspectives,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 11, no. 3, p. 1600295, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201600295.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] G. Rui and Q. Zhan, “Tailoring optical complex fields with nano-metallic surfaces,” Nanophotonics, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 2–25, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2014-0018.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] S. Zhang, et al.., “Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 259–293, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0373.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] C.-H. Lin, S.-H. Huang, T.-H. Lin, and P. C. Wu, “Metasurface-empowered snapshot hyperspectral imaging with convex/deep (CODE) small-data learning theory,” Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 6979, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42381-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] J. Xiong, et al.., “Dynamic brain spectrum acquired by a real-time ultraspectral imaging chip with reconfigurable metasurfaces,” Optica, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 461–468, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.440013.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] P. C. Wu, et al.., “Visible metasurfaces for on-chip polarimetry,” ACS Photonics, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 2568–2573, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b01527.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Y. Intaravanne and X. Chen, “Recent advances in optical metasurfaces for polarization detection and engineered polarization profiles,” Nanophotonics, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 1003–1014, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0479.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] M. K. Chen, et al.., “A meta-device for intelligent depth perception,” Adv. Mater., vol. 35, no. 34, p. 2107465, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202107465.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] S. Yang, et al.., “Realizing depth measurement and edge detection based on a single metasurface,” Nanophotonics, vol. 12, no. 16, pp. 3385–3393, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0308.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] T. Badloe, et al.., “Bright-field and edge-enhanced imaging using an electrically tunable dual-mode metalens,” ACS Nano, vol. 17, no. 15, pp. 14678–14685, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c02471.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] A. Leitis, et al.., “Angle-multiplexed all-dielectric metasurfaces for broadband molecular fingerprint retrieval,” Sci. Adv., vol. 5, no. 5, p. eaaw2871, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw2871.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] F. A. A. Nugroho, D. Albinsson, T. J. Antosiewicz, and C. Langhammer, “Plasmonic metasurface for spatially resolved optical sensing in three dimensions,” ACS Nano, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 2345–2353, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b09508.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] H. Li, J. T. Kim, J.-S. Kim, D.-Y. Choi, and S.-S. Lee, “Metasurface-incorporated optofluidic refractive index sensing for identification of liquid chemicals through vision intelligence,” ACS Photonics, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 780–789, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.3c00057.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] A. Tittl, et al.., “Imaging-based molecular barcoding with pixelated dielectric metasurfaces,” Science, vol. 360, no. 6393, p. 1105, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aas9768.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] F. Xie, M. Ren, W. Wu, W. Cai, and J. Xu, “Chiral metasurface refractive index sensor with a large figure of merit,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 122, no. 7, p. 071701, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0135657.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] F. Yesilkoy, et al.., “Ultrasensitive hyperspectral imaging and biodetection enabled by dielectric metasurfaces,” Nat. Photon., vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 390–396, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0394-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Y. Wang, et al.., “Wearable plasmonic-metasurface sensor for noninvasive and universal molecular fingerprint detection on biointerfaces,” Sci. Adv., vol. 7, no. 4, p. eabe4553, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe4553.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] F. A. A. Nugroho, et al.., “Inverse designed plasmonic metasurface with parts per billion optical hydrogen detection,” Nat. Commun., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 5737, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33466-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] C. Jung, et al.., “Disordered-nanoparticle–based etalon for ultrafast humidity-responsive colorimetric sensors and anti-counterfeiting displays,” Sci. Adv., vol. 8, no. 10, p. eabm8598, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abm8598.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Z.-C. Chia, et al.., “Polyphenol-assisted assembly of Au-deposited polylactic acid microneedles for SERS sensing and antibacterial photodynamic therapy,” Chem. Commun., vol. 59, no. 42, pp. 6339–6342, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cc00733b.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] V. T. N. Linh, et al.., “3D plasmonic coral nanoarchitecture paper for label-free human urine sensing and deep learning-assisted cancer screening,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 224, no. 1, p. 115076, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2023.115076.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] P. C. Wu, et al.., “Vertical split-ring resonator based nanoplasmonic sensor,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 105, no. 3, p. 033105, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4891234.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] K. V. Sreekanth, et al.., “Extreme sensitivity biosensing platform based on hyperbolic metamaterials,” Nat. Mater., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 621–627, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4609.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] D. Ray, T. V. Raziman, C. Santschi, D. Etezadi, H. Altug, and O. J. F. Martin, “Hybrid metal-dielectric metasurfaces for refractive index sensing,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 8752–8759, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03613.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] X. Chen, Y. Zhang, G. Cai, J. Zhuo, K. Lai, and L. Ye, “All-dielectric metasurfaces with high Q-factor Fano resonances enabling multi-scenario sensing,” Nanophotonics, vol. 11, no. 20, pp. 4537–4549, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0394.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Y. Wang, Z. Han, Y. Du, and J. Qin, “Ultrasensitive terahertz sensing with high-Q toroidal dipole resonance governed by bound states in the continuum in all-dielectric metasurface,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1295–1307, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0582.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] H.-H. Hsiao, Y.-C. Hsu, A.-Y. Liu, J.-C. Hsieh, and Y.-H. Lin, “Ultrasensitive refractive index sensing based on the quasi-bound states in the continuum of all-dielectric metasurfaces,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 10, no. 19, p. 2200812, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202200812.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] A. J. Ollanik, I. O. Oguntoye, G. Z. Hartfield, and M. D. Escarra, “Highly sensitive, affordable, and adaptable refractive index sensing with silicon-based dielectric metasurfaces,” Adv. Mater. Technol., vol. 4, no. 2, p. 1800567, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201800567.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Z. Shen and M. Du, “High-performance refractive index sensing system based on multiple Fano resonances in polarization-insensitive metasurface with nanorings,” Opt. Express, vol. 29, no. 18, pp. 28287–28296, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.434059.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Y. Chen, C. Zhao, Y. Zhang, and C.-w. Qiu, “Integrated molar chiral sensing based on high-Q metasurface,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 8696–8703, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03506.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] J. Jang, et al.., “Full and gradient structural colouration by lattice amplified gallium nitride Mie-resonators,” Nanoscale, vol. 12, no. 41, pp. 21392–21400, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0nr05624c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Y.-T. Lin, A. Hassanfiroozi, W.-R. Jiang, M. Y. Liao, W. J. Lee, and P. C. Wu, “Photoluminescence enhancement with all-dielectric coherent metasurfaces,” Nanophotonics, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 2701–2709, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0640.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] I. O. Oguntoye, et al.., “Silicon nanodisk Huygens metasurfaces for portable and low-cost refractive index and biomarker sensing,” ACS Appl. Nano Mater., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 3983–3991, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.1c04443.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] S. Campione, et al.., “Broken symmetry dielectric resonators for high quality factor Fano metasurfaces,” ACS Photonics, vol. 3, no. 12, pp. 2362–2367, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00556.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] A. Hassanfiroozi, et al.., “A toroidal-Fano-resonant metasurface with optimal cross-polarization efficiency and switchable nonlinearity in the near-Infrared,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 9, no. 21, p. 2101007, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202101007.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] J. Jeong, et al.., “High quality factor toroidal resonances in dielectric metasurfaces,” ACS Photonics, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 1699–1707, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c00179.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] J. Yao, et al.., “Plasmonic anapole metamaterial for refractive index sensing,” PhotoniX vol. 3, no. 1, p. 23, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43074-022-00069-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] J. F. Algorri, et al.., “Anapole modes in hollow nanocuboid dielectric metasurfaces for refractometric sensing,” Nanomaterials, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 30, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9010030.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] A. Leitis, M. L. Tseng, A. John-Herpin, Y. S. Kivshar, and H. Altug, “Wafer-scale functional metasurfaces for mid-infrared photonics and biosensing,” Adv. Mater., vol. 33, no. 43, p. 2102232, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202102232.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] M.-H. Seo, et al.., “Chemo-mechanically operating palladium-polymer nanograting film for a self-powered H2 gas sensor,” ACS Nano, vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 16813–16822, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c05476.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] P. C. Wu, C. Y. Liao, J.-W. Chen, and D. P. Tsai, “Isotropic absorption and sensor of vertical split-ring resonator,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 5, no. 2, p. 160581, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201600581.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] N. Liu, M. Mesch, T. Weiss, M. Hentschel, and H. Giessen, “Infrared perfect absorber and its application as plasmonic sensor,” Nano Lett., vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 2342–2348, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl9041033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] A. McClung, S. Samudrala, M. Torfeh, M. Mansouree, and A. Arbabi, “Snapshot spectral imaging with parallel metasystems,” Sci. Adv., vol. 6, no. 38, p. eabc7646, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc7646.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] D. Rodrigo, et al.., “Resolving molecule-specific information in dynamic lipid membrane processes with multi-resonant infrared metasurfaces,” Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 2160, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04594-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] A. John-Herpin, D. Kavungal, L. von Mücke, and H. Altug, “Infrared metasurface augmented by deep learning for monitoring dynamics between all major classes of biomolecules,” Adv. Mater., vol. 33, no. 14, p. 2006054, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202006054.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] P. C. Wu, et al.., “Versatile polarization generation with an aluminum plasmonic metasurface,” Nano Lett., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 445–452, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04446.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] S. Sun, Q. He, S. Xiao, Q. Xu, X. Li, and L. Zhou, “Gradient-index meta-surfaces as a bridge linking propagating waves and surface waves,” Nat. Mater., vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 426–431, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3292.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] N. Yu, et al.., “Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction,” Science, vol. 334, no. 6054, pp. 333–337, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1210713.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] A. Hassanfiroozi, et al.., “Toroidal-assisted generalized Huygens’ sources for highly transmissive plasmonic metasurfaces,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 16, no. 6, p. 2100525, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202100525.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] A. Hassanfiroozi, Z.-S. Yang, S.-H. Huang, W. Cheng, Y. Shi, and P. C. Wu, “Vertically-stacked discrete plasmonic meta-gratings for broadband space-variant metasurfaces,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 11, no. 8, p. 2202717, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202202717.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] K. Koshelev, G. Favraud, A. Bogdanov, Y. Kivshar, and A. Fratalocchi, “Nonradiating photonics with resonant dielectric nanostructures,” Nanophotonics, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 725–745, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0024.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] M. L. Tseng, Y. Jahani, A. Leitis, and H. Altug, “Dielectric metasurfaces enabling advanced optical biosensors,” ACS Photonics, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 47–60, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c01030.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Y. Luo, et al.., “Metasurface-based abrupt autofocusing beam for biomedical applications,” Small Methods, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 2101228, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.202101228.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0809).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Enabling new frontiers of nanophotonics with metamaterials, photonic crystals, and plasmonics

- Reviews

- Rational design of arbitrary topology in three-dimensional space via inverse calculation of phase modulation

- Frequency comb measurements for 6G terahertz nano/microphotonics and metamaterials

- Research Articles

- Electromagnetic signal propagation through lossy media via surface electromagnetic waves

- Mode-cleaning in antisymmetrically modulated non-Hermitian waveguides

- Hollow core optical fiber enabled by epsilon-near-zero material

- Photoluminescence lifetime engineering via organic resonant films with molecular aggregates

- Photoluminescence emission and Raman enhancement in TERS: an experimental and analytic revisiting

- Scalable hot carrier–assisted silicon photodetector array based on ultrathin gold film

- Ultrafast acousto-optic modulation at the near-infrared spectral range by interlayer vibrations

- Probing the multi-disordered nanoscale alloy at the interface of lateral heterostructure of MoS2–WS2

- Topological phase transition and surface states in a non-Abelian charged nodal line photonic crystal

- Ultraviolet light scattering by a silicon Bethe hole

- Exploring plasmonic gradient metasurfaces for enhanced optical sensing in the visible spectrum

- Thermally tunable binary-phase VO2 metasurfaces for switchable holography and digital encryption

- Electrochromic nanopixels with optical duality for optical encryption applications

- Broadband giant nonlinear response using electrically tunable polaritonic metasurfaces

- Mechanically processed, vacuum- and etch-free fabrication of metal-wire-embedded microtrenches interconnected by semiconductor nanowires for flexible bending-sensitive optoelectronic sensors

- Formation of hollow silver nanoparticles under irradiation with ultrashort laser pulses

- Dry synthesis of bi-layer nanoporous metal films as plasmonic metamaterial

- Three-dimensional surface lattice plasmon resonance effect from plasmonic inclined nanostructures via one-step stencil lithography

- Generic characterization method for nano-gratings using deep-neural-network-assisted ellipsometry

- Photonic advantage of optical encoders

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Enabling new frontiers of nanophotonics with metamaterials, photonic crystals, and plasmonics

- Reviews

- Rational design of arbitrary topology in three-dimensional space via inverse calculation of phase modulation

- Frequency comb measurements for 6G terahertz nano/microphotonics and metamaterials

- Research Articles

- Electromagnetic signal propagation through lossy media via surface electromagnetic waves

- Mode-cleaning in antisymmetrically modulated non-Hermitian waveguides

- Hollow core optical fiber enabled by epsilon-near-zero material

- Photoluminescence lifetime engineering via organic resonant films with molecular aggregates

- Photoluminescence emission and Raman enhancement in TERS: an experimental and analytic revisiting

- Scalable hot carrier–assisted silicon photodetector array based on ultrathin gold film

- Ultrafast acousto-optic modulation at the near-infrared spectral range by interlayer vibrations

- Probing the multi-disordered nanoscale alloy at the interface of lateral heterostructure of MoS2–WS2

- Topological phase transition and surface states in a non-Abelian charged nodal line photonic crystal

- Ultraviolet light scattering by a silicon Bethe hole

- Exploring plasmonic gradient metasurfaces for enhanced optical sensing in the visible spectrum

- Thermally tunable binary-phase VO2 metasurfaces for switchable holography and digital encryption

- Electrochromic nanopixels with optical duality for optical encryption applications

- Broadband giant nonlinear response using electrically tunable polaritonic metasurfaces

- Mechanically processed, vacuum- and etch-free fabrication of metal-wire-embedded microtrenches interconnected by semiconductor nanowires for flexible bending-sensitive optoelectronic sensors

- Formation of hollow silver nanoparticles under irradiation with ultrashort laser pulses

- Dry synthesis of bi-layer nanoporous metal films as plasmonic metamaterial

- Three-dimensional surface lattice plasmon resonance effect from plasmonic inclined nanostructures via one-step stencil lithography

- Generic characterization method for nano-gratings using deep-neural-network-assisted ellipsometry

- Photonic advantage of optical encoders