Abstract

Researchers seeking to analyse how intersubjectivity is established and maintained face significant challenges. The purpose of this article is to provide theoretical/methodological tools that begin to address these challenges. I develop these tools by applying several concepts from multimodal (inter)action analysis to an excerpt taken from the beginning of a tutoring session, drawn from a wider data set of nine one-to-one tutoring sessions. Focusing on co-produced higher-level actions as an analytic site of intersubjectivity, I show that lower-level actions that co-constitute a higher-level action can be delineated into tiers of materiality. I identify three tiers of materiality: durable, adjustable and fleeting. I introduce the theoretical/methodological tool tiers of material intersubjectivity to delineate these tiers analytically from empirical data, and show how these tiers identify a multimodal basis of material intersubjectivity. Building on this analysis I argue that the durable and adjustable tiers of material intersubjectivity produce the interactive substrate, which must be established in order for actions that display fleeting materiality to produce intersubjectivity. These theoretical/methodological tools extend the framework of multimodal (inter)action analysis, and I consider some potential applications beyond the example used here.

Introduction

When social actors do things together, how can we analyse the material basis of their intersubjectivity? Intersubjectivity is variously defined in the literature, and here I build on Matusov (1996) to investigate intersubjectivity as social actors co-producing higher-level actions, and specifically address the material basis of intersubjectivity. Social actors produce changes in their environment of varying durability. Those changes that are more durable produce a basis of material intersubjectivity, upon which actions with much more fleeting materiality can produce material intersubjectivity.

In this article I utilise multimodal (inter)action analysis (Norris 2004a, 2011, 2013) to conduct an analysis of the beginning of a tutoring session to show how tutor and student come to co-produce a higher-level action. I utilise several tools from multimodal (inter)action analysis to conduct my analysis, including higher and lower-level actions, modal density and the foreground/background continuum of attention/awareness, semantic/pragmatic means (Norris 2004a) and modal configurations (Norris 2009). Here, I illustrate that lower-level actions, as part of the same higher-level action, can be delineated into tiers of materiality (Pirini 2015). Through this analysis, I develop a theoretical/methodological tool called tiers of material intersubjectivity to analyse the different types of materiality established within an interaction. In addition I determine how these actions produce an interactive substrate, which provides a basis for more fleeting material intersubjectivity. Building on previous work in intersubjectivity (Matusov 1996, 2001) and utilising the theoretical basis of multimodal (inter)action analysis (Norris 2013; Scollon 1998; Wertsch 1998), these theoretical/methodological tools expand upon multimodal (inter)action analysis as a framework for analysing social interaction.

Background literature

Multimodal (inter)action analysis provides several theoretical/methodological tools for analysing interaction. In this article I analyse a data extract from a tutoring session between a tutor and a student, focusing on how tutor and student come together to achieve a complex, co-ordinated action. Through the resultant analysis I develop theoretical/methodological tools that extend the framework of multimodal (inter)action analysis. I show that intersubjectivity produced in the interaction can be analysed as a material similarity or constancy, and that this similarity permeates the higher-level actions that tutor and student produce.

Successfully co-ordinating action between two or more participants has been defined as a problem of establishing shared understanding regarding the situation (Goffman 1963; Mortimer and Wertsch 2003). Through interaction and negotiation a definition of the situation emerges that is shared between participants. This process has been explored in educational settings, where students are supported to develop a definition of the situation that matches the goals of the teacher or the institution (Wertsch 1991). Wertsch (1984) uses the notion of situation definition to argue that working in the zone of proximal development involves a more experienced person developing a hybrid definition of the situation which sits somewhere between their own ‘native’ situation definition, and the less experienced person’s ‘native’ situation definition.

Matusov (1996, 2001) has had considerable influence on the concept of intersubjectivity, by showing that concentrating on intersubjectivity as shared understanding limits studies of intersubjectivity to interactions where agreement is present. He points out that directing studies towards agreement may reduce the problem of intersubjectivity to one of symmetry. As a result, research taking this approach compares individual subjectivities to identify progress towards a state of symmetry (Matusov 1996). This critique also applies to approaches that focus on shared background knowledge as a basis for intersubjectivity (Rommetveit 1974, 1979) for similar reasons.

Matusov (1996) analyses a group of girls preparing to perform a play in school. The girls argue over the course of several sessions about many features of their play, including how they will interpret the original text. Although the girls disagree, they are clearly engaged in an intersubjective process. Matusov suggests that intersubjectivity should be studied as a problem of co-ordinating contributions to joint activity. This participatory approach does not reject traditional research on intersubjectivity. However, in order to expand intersubjective research to a wider range of social situations Matusov calls for treating intersubjectivity as a process of co-ordinating joint activity that defines individual contributions, and their co-ordination,

Working in a multimodal (inter)action analytic framework, I utilise Scollon (1998, 2001) and Wertsch’s (1998) interpretation of Vygotsky’s (1978) notion of mediated action. As such, rather than addressing my analytic attention towards an object of joint activity (Leontyev 1977) I take the mediated action as a unit of analysis. I shall address mediated action in more detail in the next section as I expand upon my methodology. However, here I wish to point out that where Matusov (1996) speaks of co-ordinating joint activity as an analytic site for intersubjectivity, within the theoretical background of multimodal (inter)action analysis it is more appropriate to speak of co-produced higher-level action.

Norris (2011) uses the term co-production to investigate social actors coming together to produce higher-level actions with one another. Co-production problematises the concept of co-construction, which is more commonly used in social research. Co-construction refers to the social nature of interaction as dynamic and unfolding. As a social theory, multimodal (inter)action analysis incorporates a notion of co-construction, inherent in the mediated action as a unit of analysis. Norris (2011) points out that all actions are (inter)actions, whether produced with other social actors, or with objects in the environment. The mediated action (Norris 2004a; Scollon 1998; Wertsch 1998) highlights the historical and social aspects of action that are always present. Therefore, in multimodal (inter)action analysis, co-construction can be considered as a broad underlying concept.

Co-construction is used in the same, and other ways within the wider literature pertaining to social interaction. In order to elucidate how co-production problematises co-construction I would like to highlight how co-construction is utilised in the literature in the following three ways:

As a philosophical basis

As describing the structure of talk

As describing the social functions of talk

Sociolinguistic approaches to social action take up a notion of co-construction, primarily focusing on language as a site of cultural production (Butler 1990; Holmes 1997; Weedon 1987). Studies in sociolinguistics consider, for example, the production of identity, gender and cultural groups through language. Co- construction can be seen as a philosophical basis for much of the work in sociolinguistics, as many researchers in sociolinguistics work within a social constructivist framework, where language is viewed as ‘a set of strategies for negotiating the social landscape’ (Crawford 1995, p. 17). Through language speakers actively construct aspects of their culture, and these constructions are always dynamic, situated and co-constructed.

Sociolinguistic approaches also refer to co-construction in terms of the structure of talk. When studying how New Zealand men and women construct gender identities through storytelling, Holmes (1997) identifies a continuum of joint production that applies to how stories are co-constructed. At times the narrator is given uncontested access to the floor, and at other times the listener(s) co-construct the story with extensive, and at times simultaneous input. Talk may be more or less co-constructed depending on aspects such as context, culture and gender. Similarly, Coates (2004), also working with gender and talk, points out that women more frequently co-construct utterances in a sort of ‘conversational jam session’ (p. 131) where an utterance containing a subject – verb – object might be produced by two different speakers. Co-construction in these examples is used to refer to the enactment of talk, and co-construction is shown as one element of the production of talk that varies across social settings and groups. In addition, since the focus of sociolinguistics is often on the ways in which aspects of culture are produced through talk, co-construction can refer to the cultural functions of talk. For example, because particular aspects of storytelling produce gender identity, gender identity can also be referred to as co- constructed (e. g. Coates, 2004; Holmes, 1997).

Conversation analytic approaches to talk as co-constructed take a much more sequential and micro level approach than the sociolinguistic work discussed above. Goodwin (1979) demonstrates that social actors shape their utterances as they produce them. Through analysing a sentence produced during a dinner conversation, Goodwin shows that the social actor, John, shapes his sentence as he produces it. John’s sentence production is affected by whom he gazes at, whether they meet his gaze or not, and whether what he is saying is new to them. Goodwin concludes that analysts cannot remove the analysis of sentences from the interactive process, because the sentence is produced contingent on the interactional environment.

Conversation analytic approaches to co-construction focus on the enactment of talk, but take a highly sequential approach in comparison to sociolinguistic work. Sacks (1987) points out that overwhelmingly talk is produced by one speaker at a time, and conversational analytic work has primarily addressed the ‘spontaneous playing out of the sequentially contingent and co-constructed external flow of interactional events’ (Jacoby and Ochs 1995, p. 175). Indeed, Jacoby and Ochs (1995) argue that any moment in interaction is ripe for a social actor to ‘redirect the unfolding discourse, such that individual understandings, human relationships, and the social order might be changed’ (Jacoby and Ochs 1995, p. 178).

The use of the term co-construction within sociolinguistics and conversation analysis shows that co-construction is applied in several different ways, lessening its analytical power. As I pointed out above, I argue that the notion of co-production (Norris 2011) conversely, holds more analytical power than the notion of co-construction.

Norris (2011) shows that actions are often co-produced at different levels of attention/awareness, with one social actor focusing on the co-produced higher-level action, while another pays a lower level of attention/awareness to the co-produced higher-level action. Using the concept of modal density Norris (2011) constructs a graph of the attention/awareness of two friends talking in a kitchen. One friend, Anna, is putting away her groceries, while the other, Sandra, is sitting at the kitchen table talking about her relationship with her (almost ex-) husband. Anna, however, focuses her attention on putting away her groceries. She produces high modal density as she puts away her groceries through the complexly intertwined modes of proxemics, posture, walking, gaze and object handling. At the same time, Anna attends to her friend Sandra at the mid-ground of her attention/awareness. Anna produces backchannel responses, gazes to her friend, and makes facial expressions of concern. Norris (2011) shows that Anna is producing multiple interactions simultaneously. The higher-level action of putting groceries away is not co-produced with Sandra, and would likely proceed in much the same way with or without her presence. The higher-level action of listening to Sandra is co-produced with Sandra, but Anna produces this action in a very different way compared to Sandra, who produces this higher-level action at the foreground of her attention/awareness. By addressing the multiple levels of attention/awareness that social actors produce, Norris demonstrates the utility of considering the co-production of multiple, simultaneous (multimodal) higher-level actions. Co-construction, in contrast, does not provide for multiple levels of attention/awareness, and only considers the focus of social actors’ attention/awareness. Thus, using the notion of co- construction in the above example, the analyst would wrongfully conclude that Sandra’s conversation about her difficult relationship is co-constructed by both women in their focused attention.

In addition, co-construction is overwhelmingly applied to talk; so much so that even those researchers taking other non-verbal actions into account (Haddington et al. 2013), suggest that talk is most likely to be the most relevant and most important mode of communication. As a result, co- construction, when applied to the structure and social functions of talk, does not capture the multimodal nature of higher-level actions. Since each social actor engaged in a co-produced higher-level action produces a different, yet similar, higher-level action, I explore the material aspects of co-production, which provide a fundamental basis for co-produced higher-level actions, and material intersubjectivity.

Methodology

I utilise concepts from multimodal (inter)action analysis (Norris 2004a, 2011, 2013) to develop a theoretical and methodological tool for the analysis of intersubjectivity. As I pointed out above, multimodal (inter)action analysis builds on mediated discourse analysis (Scollon 1998, 2001; Wertsch 1998) and takes the mediated action as its unit of analysis. A mediated action is defined as a social actor acting with or through mediational means (Scollon 1998; Wertsch 1998), and thus can be of any scope. Higher and lower-level actions delineate mediated actions into heuristic units. While neither is logically prior, higher-level actions are defined as chains of lower-level actions bracketed with a beginning and an ending (Norris 2004a). Lower-level actions are defined as the smallest pragmatic meaning units of a mode, such as a gesture unit or an utterance (Norris 2004a). Here I am interested in the materiality of the actions that tutors and students produce as they come together and begin to engage in the co-produced higher-level action of tutoring.

I have argued elsewhere (Pirini 2014) that tutors and students produce multiple simultaneous higher-level actions as they move towards producing similar higher-level actions at the focus of their attention/awareness. These multiple higher-level actions can be analysed using modal density, which is made up of both modal complexity and modal intensity (Norris 2004a). As lower-level actions are defined as the smallest pragmatic meaning units of a mode, modal complexity and intensity refer to lower-level action complexity, and lower-level action intensity, within a higher-level action (Norris 2014).

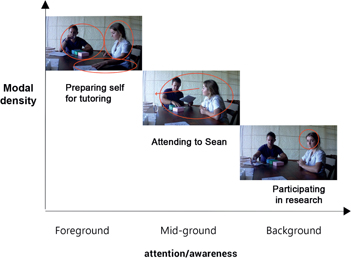

Modal density, coupled with the foreground/background continuum of attention/awareness provides an analysis of the phenomenological attention/awareness displayed by a social actor (Norris 2004a). Higher-level actions produced with the most complex interplay of lower-level actions, or the most intense lower-level actions, or a combination of the two, can be positioned at the focus of the social actor’s attention/awareness in the heuristic model below. Higher-level actions produced with lesser modal density can be positioned at a lower level of attention/awareness. The analysis can be construed as a graph of attention/awareness (Figure 1), clearly positioning higher-level actions in the foreground, mid-ground and background of a social actor’s attention/awareness.

Example of graph of foreground/background continuum of attention/awareness for a social actor adapted from Norris (2004a, p. 99).

In this example graph I depict three higher-level actions. Other configurations are possible, including no action in the focus, or no action in the mid-ground, and additional actions at the midground and background. While multiple actions are produced in the mid-ground and background, Norris (2004b) argues that only one action is possible at the focus of attention/awareness. Makboon (2015) shows that actions in the background, such as religious belief, can structure actions in the foreground. The foreground/background continuum of attention/awareness shows how multiple simultaneously produced higher-level actions intersect with one another in the mind of the social actor, while remaining as demonstrably bounded units as the actions are produced, bracketed by a beginning and an ending.

Social actors shift their attention/awareness during interaction (Norris 2008). New higher-level actions enter their attention/awareness, and ongoing higher-level actions shift along the foreground/background continuum. Shifts in focused attention/awareness are often produced along with a semantic/pragmatic means, which is a marked lower-level action that is not related to the initial higher-level action, or to the newly focused on higher-level action (Norris 2004a). The semantic aspect of the means helps social actors to shift their own focus, and the pragmatic aspect indicates to others that a social actor has shifted their attention/awareness.

Since I am interested in material intersubjectivity in co-produced action, semantic/pragmatic means and the foreground/background continuum of attention/awareness provides for the analysis of the shifting attention/awareness of social actors as they come together to co-produce action. However, even though social actors co-produce the same higher-level action, such as tutoring, each social actor produces a higher-level action from their own perspective, their actions are always different and therefore unique to each individual social actor. The material similarity that social actors produce when they co-produce higher-level actions provides an analytical target for the study of intersubjectivity. This approach avoids reducing intersubjectivity to the sum of individual contributions, since the difference between each social actor’s co-produced higher-level actions is always present in the analysis.

Material changes to the environment can be analysed with considerable specificity through the analysis of lower-level actions. When I speak of materiality in relation to lower-level actions I am referring to the immediate materiality through which the lower-level action is produced. An utterance, such as the greeting ‘hello’ does not contain lasting physical materially. Because the utterance is produced through vibrations in the air in the form of soundwaves, it dissipates rapidly. Even though the effects of an utterance might be analysable within the interaction beyond the immediate material production of the utterance, the lower-level action of the utterance maintains only a fleeting physical materiality. In contrast, a lower-level action in the mode of posture, such as leaning backwards in a chair and holding this posture, is produced continuously through the body, and therefore posture displays a much more durable physical materiality than an utterance. In order to examine lower-level actions I utilise the notion of modal configuration (Norris 2009) to ‘explode’ higher-level actions into their constituent lower-level actions. Analysing lower-level actions using the concept of modal configuration reveals the varying materialities of the different lower-level actions produced.

Initiating tutoring: Analysis of multiple higher-level actions

The data for this study were collected from nine one to one tutoring sessions between experienced tutors and high school students. The excerpt I analyse comes from the beginning of a mathematics session between the tutor Sean, and the student Eleanor. The transcript (Figure 2) begins with Eleanor sitting down, which brackets the start of a higher-level action. The transcript ends with Eleanor producing a marked sigh, which functions as a semantic/pragmatic means, indicating a shift in attention/awareness as Eleanor produces a new higher-level action in her focus. Therefore the transcript includes the beginning of a higher-level action, the higher-level action of preparing herself for tutoring; and a shift to focus on another higher-level action, the higher-level action of engaging in tutoring. I show below that Eleanor focuses on preparing herself for tutoring, while also producing two other higher-level actions with less attention/awareness.

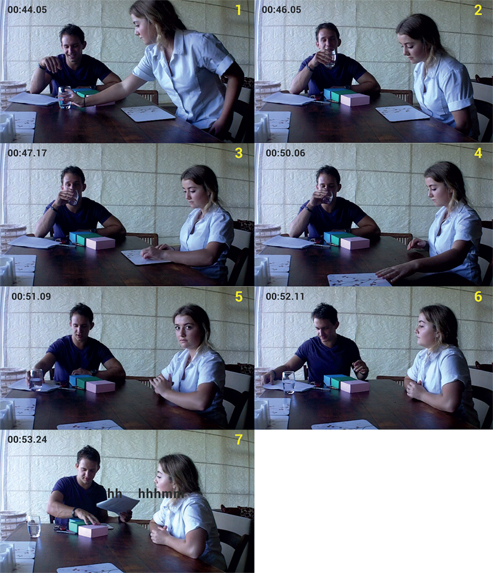

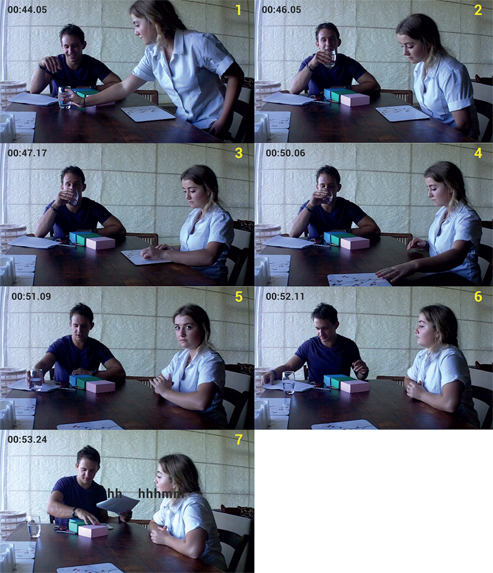

Eleanor (right of frame) settling into the tutoring session.

Eleanor arrives at the table (Figure 2) and reaches out to place a glass of water in front of Sean (Image 1). Sean has placed some papers to his right, and has lined up three boxes in front of him.

Eleanor takes her seat (Image 2), establishing a proxemic relationship to Sean and to the objects on the table. The table, the chairs and the layout of the room mediate these proxemic relationships. Sean then picks up the glass of water and takes a drink. As Eleanor sits, she gazes at the placemat on the table in front of her. She reaches out and plucks what appears to be a hair off the placemat (Image 3). Then she pushes the placemat off to her left (Image 4). She glances momentarily at the camera (Image 5) while she folds her arms in front of herself. Then Eleanor looks out of a window (Image 6), which is positioned in front of her. Her posture faces the window and she is positioned perpendicular to Sean. Sean reaches for the papers to his right, picks them up and begins to (inter)act with the boxes in front of him (Image 7). At this moment, Eleanor shifts her gaze in Sean’s general direction, without, however, focusing on the interaction with him just yet. She takes an audible in breath and then lets out a marked sigh.

In this excerpt, Eleanor produces three higher-level actions at different levels of her attention and awareness. I have a produced a graph in Figure 3 to more clearly show the relative attention/awareness Eleanor produces. At the foreground of her attention/awareness Eleanor produces the higher-level action of preparing self for tutoring, while in the mid-ground she produces the higher-level action of attending to Sean. Lastly, in the background Eleanor produces the higher-level action of participating in research. These higher-level actions are produced simultaneously throughout the entire excerpt through Eleanor’s lower-level actions, such as gaze shifts, posture shifts, in breaths, sighing sounds, and object handling.

Eleanor’s attention/awareness as she prepares herself for tutoring.

I utilise the foreground−background continuum of attention/awareness and the concept of modal density (Norris 2004a) to determine how much attention Eleanor pays to each particular higher-level action. I now focus on the modal density of each action in more detail.

The higher-level action with the highest modal density is preparing self for tutoring. In Figure 1.3 I have highlighted a frame from the video that shows many, but of course not all, of the material aspects of this higher-level action.

Eleanor prepares herself for tutoring through her posture as she sits down (Figure 4, Image 1), through handling the placemat on the table in front of her (Figure 4, Image 2), through her proxemic relationship to Sean and his boxes and papers (Figure 4, Image 3), and finally through her marked sigh. Here, Eleanor settles herself into her chair, organises the space in front of her, and finally indicates that she is ready to begin through the marked sigh. This sigh is a semantic/pragmatic means, which indicates a shift in Eleanor’s focused attention (Norris 2004a). The semantic aspect of this means helps Eleanor to shift her own focus, and the pragmatic aspect of this means indicates to Sean that Eleanor is beginning to focus on the interaction with him and that she is now ready for the tutoring session.

Eleanor preparing herself for tutoring.

As illustrated in Figure 3, Eleanor produces the higher-level action of attending to Sean at the mid-ground of her attention/awareness, with a lower modal density than preparing herself for tutoring (Figure 5).

Eleanor attending to Sean.

Primarily Eleanor produces attention/awareness of Sean through her proxemics to him, her proxemics to the boxes he has positioned, and through her gaze. However, Eleanor does not gaze directly at Sean, but off towards his shoulder. In addition she does not open her posture widely towards Sean, and rather remains facing the window. These aspects of Eleanor’s lower-level actions demonstrate a lesser modal density of the higher-level action, and show that she attends to the interaction with Sean at a lower level of attention/awareness than preparing herself for tutoring.

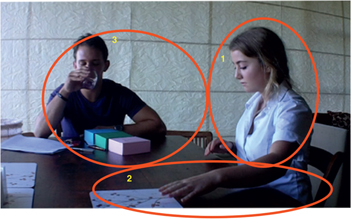

The third higher-level action that Eleanor produces in this excerpt is participating in research. She produces participating in research with low modal density, primarily through the layout of the room and her proxemics to the researcher and the camera. Eleanor also glances once at the camera after she moves the placemat as shown in Figure 6.

Eleanor producing the higher-level action of participating in research as she glances at the camera.

This glance shows Eleanor briefly increasing her attention/awareness of the research project. However, relative to her other higher-level actions Eleanor produces participating in research with low modal density, and therefore at a lower level of attention/awareness.

Thus far, I have shown how Eleanor begins to establish material intersubjectivity with Sean. She produces a proxemic relationship with him and the tutoring objects as she sits down at the table. However, her interaction with Sean is produced at the mid-ground of her attention/awareness. Eleanor focuses most strongly on preparing herself for tutoring and does not produce a particularly strong interaction with Sean at this stage. Near the end of the excerpt Eleanor indicates that she is ready to focus on the tutoring session as she produces a semantic/pragmatic means and shifts her gaze in Sean’s direction.

During this excerpt, Eleanor uses modes such as posture and proxemics in more than one higher-level action. For example, Eleanor’s posture produces preparing herself for tutoring, and attending to Sean. In addition, her position in her chair sets up proxemic relationships that are implicated in all three of the higher-level actions that she produces. It is through these multiple lower-level actions that Eleanor establishes some form of material intersubjectivity with Sean, which I address in detail in Establishing intersubjectivity below.

Establishing intersubjectivity

In this section I analyse more closely the process through which Eleanor establishes material intersubjectivity with Sean. I build on the above analysis of modal density and attention/awareness to focus on the material intersubjectivity Eleanor produces through her actions. I focus on the varying materialities that Eleanor produces via the modal configurations (Norris 2009) of higher-level actions, and the implications these have for material intersubjectivity. Modal configurations refer to ‘the hierarchical configuration of lower-level actions (or their chains) in relation to other lower-level actions (or their chains) within a higher-level action’ (Norris (in press), p. 6). This concept enables me to examine the particular materiality Eleanor produces through her actions and, more specifically, to investigate the different types of materiality.

As I discuss earlier, materiality can be more durable or more fleeting, and lower-level actions are capable of producing materiality that ranges from durable to fleeting (Norris 2004a). I categorise the materiality that lower-level actions produce into three types:

Durable materiality: Actions that persist during the interaction. Typically achieved through layout and furniture, to produce stable proxemic relationships.

Adjustable materiality: Actions that persist but are adjustable. Typically achieved through posture and movable objects.

Fleeting materiality: Actions that do not physically persist during the interaction. Typically achieved through gestures, spoken language, gaze, etc.

Eleanor producing intersubjectivity with Sean through the higher-level action of preparing herself for tutoring.

Here, I analyse the same transcript from Figure 2 (Figure 7) to more closely examine material intersubjectivity. When Eleanor takes her seat at the table (Images 1 and 2) she produces material intersubjectivity with Sean through the proxemic relationships maintained by layout and furniture. This relationship is relatively durable. Focusing first on layout and furniture, both the layout of the room and the furniture in it produce durable and interlinked materiality. Eleanor could move her chair backwards away from the table, or she could slide the chair down the edge of the table to be either closer to Sean or further away from him. These changes would establish a different intersubjectivity with Sean, and would be quite marked changes, which would then also persist. On a more durable level, Eleanor is unlikely to be able to move the table, and if she did it would be quite a marked endeavour, and this would have a large effect on the progression of the interaction with Sean.

Even more durable features like the floor and walls rely on architectural, practical, geographic, financial and many other influences. Eleanor is very unlikely to change these aspects during her interaction with Sean. Therefore the particular proxemic relationship with Sean that Eleanor produces through layout and furniture is of durable materiality. Layout and furniture are intimately linked to proxemic relationships, and proxemics is durable in similar ways (Norris 2010). Eleanor could stand up and move around the room. Indeed when she fetched a glass of water she did just this. However, by doing so she changed the proxemics in such a way that the interaction she produced with Sean was also strongly changed, to the extent that Eleanor was no longer producing the same higher-level action. She had shifted her attention/awareness to the higher-level action of fetching Sean a glass of water.

As Eleanor sits, she takes up a particular posture. She faces forwards and her posture is perpendicular to Sean. Eleanor maintains this posture throughout the excerpt. During the session, however, Eleanor changes her posture: sometimes rotating her torso to face Sean more directly; sometimes leaning back in her chair. The materiality that Eleanor produces through posture is adjustable. She can make changes to her posture, but her posture is always present.

Regardless of how a social actor positions their body, they always produce posture, and typically postures are taken up and held for some period of time. Rapid postural changes in a situation such as the one analysed here often indicate some sort of distress or nervousness. Either way, posture is less durable than layout and proxemics because it may change while maintaining material intersubjectivity. Objects are also changeable in a similar way as they can easily be moved around, and once positioned they persist until further acted upon. Social actors produce proxemic relationships with objects like this, and at other times may interact more directly with them, e.g . by moving them or referring to them. For example, Eleanor moves a placemat from in front of her (Image 4).

Throughout the excerpt Eleanor shifts her gaze from the glass of water (Image 1) to the placemat (Images 2 – 4), to the camera (Image 5), to the window (Image 6) and to Sean (Image 7). Eleanor’s gaze shifts produce much more fleeting changes in materiality than do postural adjustments. Similarly, Eleanor’s in breath and sigh (Image 7) produce fleeting materiality because they do not physically persist.

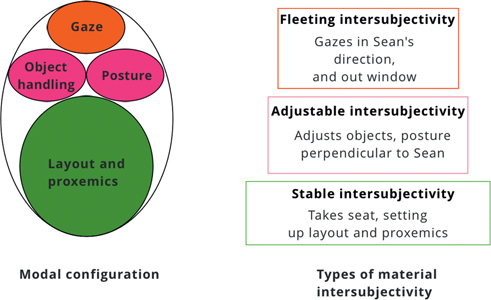

The concept of modal configuration (Norris 2009) provides a tool to examine the different types of materiality produced by Eleanor’s higher-level action of preparing herself for tutoring. The modal configuration illustrated to the left of Figure 8 shows that Eleanor’s higher-level action is comprised of lower-level actions attributed to the modes of layout and proxemics, object handling, posture, and gaze.

Modal configuration of preparing herself for tutoring and associated types of material intersubjectivity.

As described above, these concrete actions produce differing materialities. The types of materiality and the associated lower-level actions align with the tiers of material intersubjectivity illustrated to the right of the modal configuration in Figure 8.

Due to the durable and adjustable materialities of lower-level actions, Eleanor’s and Sean’s higher-level actions exhibit a similarity or constancy. The similarity comes about (from bottom to top in Figure 8) in the following ways:

Stable intersubjectivity

Produced through proxemics between Eleanor and Sean. This proxemic relationship is relatively stable due to the durability of layout and furniture.

Adjustable intersubjectivity

Produced through posture and proxemics to movable objects. Both Eleanor and Sean produce proxemic relationships to objects that become relevant as they are implicated in higher-level actions. Social actors always produce posture and, due to layout and furniture, in the excerpt Eleanor and Sean always produce posture that is at least somewhat open to each other.

Fleeting intersubjectivity

Produced through actions that only physically persist for a short time. These actions include, for example, gesture, gaze shifts, head movement, and utterances.

Conclusion

In this article, by applying the theoretical/methodological tools of multimodal (inter)action analysis (Norris 2004a, 2011, 2013), I have shown that delineating actions based on materiality provides for an analysis of how intersubjectivity is established and maintained between social actors (Pirini 2015). Building on this finding I develop two theoretical/methodological tools: tiers of material intersubjectivity, and the interactive substrate.

The excerpt shows Sean and Eleanor coming to co-produce the higher-level action of tutoring. Focusing on Eleanor, I show that she produces three simultaneous higher-level actions at different levels of attention/awareness. She focuses most strongly on preparing herself for tutoring, and mid-grounds her attention towards Sean. She is also aware of participating in research, but backgrounds this action. Utilising the concept of modal configuration I determined the relationship between lower-level actions within Eleanor’s higher-level actions. At this stage materiality became relevant, as I showed that Eleanor’s lower-level actions could be delineated based on the durability of their immediate materiality. I categorised this materiality into three tiers. The first was the most materially durable tier, and I showed that Eleanor produces durable materiality through relevant furniture and person proxemics. The second tier displayed adjustable materiality, and I showed that Eleanor produces adjustable materiality through relevant posture and proxemics to movable objects. The third tier exhibited fleeting materiality, and I showed that Eleanor produces fleeting materiality through bodily movements such as utterances, gaze, and gesture.

I show that material intersubjectivity permeates all the higher-level actions that social actors produce, and that material intersubjectivity establishes a link between the multiple, simultaneous higher-level actions that social actors are engaged in.

I referred to the durable and adjustable tiers of material intersubjectivity as the interactive substrate (Pirini 2015). Actions that produce fleeting material changes require an interactive substrate to be established if they are to have an ongoing influence on the interaction. For example, in order for Eleanor’s sigh, which has fleeting materiality, to operate as a pragmatic means indicating to Sean that she is ready to begin, Sean and Eleanor must at the very least have established a certain proxemic relationship through their postures and layout. The proxemic relationship, established as part of Eleanor’s multiple simultaneous higher-level actions, produces an essential aspect of the interactive substrate upon which the fleeting materiality of the sigh can build further intersubjectivity.

Through empirical exploration and analysis of data from high school tutoring sessions, I have applied theoretical/methodological tools from multimodal (inter)action analysis (Norris 2004a, 2011, 2013) and expanded the framework by developing tiers of material intersubjectivity and the interactive substrate (Pirini 2015). These tools highlight the material aspects of intersubjectivity, and reinforce the utility of working with the concept of attention/awareness, respecting the complex lives that social actors are engaged in.

Multimodal (inter)action analysis has been applied in a wide range of interactional contexts, including kite surfing (Geenen 2013), marketing (White 2012), vegetarian identity (Makboon 2013), business coaching (Pirini 2013) and training interpreters (Krystallidou 2014). The variety of thematic applications for multimodal (inter)action analysis reflects the flexibility of the framework, and its relevance to social interaction. The tools I introduce here are grounded strongly within the theoretical basis of multimodal (inter)action analysis, and are developed through utilising established theoretical/methodological tools. As a result, tiers of material intersubjectivity and the interactive substrate can be applied widely to analyse how social actors establish intersubjectivity with one another, and how intersubjectivity is maintained, or changed, throughout an interaction.

References

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Coates, J. (2004). Women, Men, and Language: A Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in Language. London: Pearson Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Crawford, M. (1995). Talking Difference: On Gender and Language. London: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Geenen, J. (2013). Actionary Pertinence: Space to place in kitesurfing. Multimodal Communication, 2(2):123–153.10.1515/mc-2013-0007Suche in Google Scholar

Goffman, E. (1963). The neglected situation. American Anthropologist, 6(6):133–136.10.1016/B978-0-08-023719-0.50040-1Suche in Google Scholar

Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. In: Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, G. Psathas (Ed.), 97–121. New York: Irvington Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Haddington, P., Mondada, L., and Nevile, M. (2013). Being mobile: Interaction on the move. In: Interaction and Mobility, Language and the Body in Motion, P. Haddington, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Eds.). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. Retrieved from http://www.degruyter.com/view/product/18376010.1515/9783110291278Suche in Google Scholar

Holmes, J. (1997). Story-Telling in New Zealand Women’s and Men’s Talk. In: Gender and Discourse, 263–294. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. Retrieved from http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/gender-and-discourse/n12.xml10.4135/9781446250204.n12Suche in Google Scholar

Jacoby, S., and Ochs, E. (1995). Co-construction: An introduction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28(3):171–183.10.1207/s15327973rlsi2803_1Suche in Google Scholar

Krystallidou, D. (2014). Gaze and body orientation as an apparatus for patient inclusion into/exclusion from a patient-centred framework of communication. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 8(3):399–417.10.1080/1750399X.2014.972033Suche in Google Scholar

Leontyev, A. N. (1977). Activity and consciousness. Philosophy in the USSR, Problems of Dialectical Materialism. Retrieved from http://www.trotsky.org/archive/leontev/works/activity-consciousness.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

Makboon, B. (2013). The “Chosen One”: Depicting religious belief through gestures. Journal Multimodal Communication, 2(2):171–194.10.1515/mc-2013-0009Suche in Google Scholar

Makboon, B. (2015). Communicating Religious Belief: Multimodal Identity Production of Thai Vegetarians. Auckland, NZ: AUT University.Suche in Google Scholar

Matusov, E. (1996). Intersubjectivity Without Agreement. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 3(1):25–45. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca0301_4http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca0301_4Suche in Google Scholar

Matusov, E. (2001). Intersubjectivity as a way of informing teaching design for a community of learners classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(4):383–402.10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00002-6Suche in Google Scholar

Mortimer, E. F., and Wertsch, J. V. (2003). The Architecture and Dynamics of Intersubjectivity in Science Classrooms. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 10(3):230–244. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1003_5http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1003_5Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2004a). Analyzing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203379493Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2004b). Multimodal discourse analysis: A conceptual framework. In: Discourse and Technology: Multimodal Discourse Analysis, P. LeVine & R. Scollon (Eds.), 101–115. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2008). Some thoughts on personal identity construction. In: Advances in Discourse Studies, V. K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew, & R. H. Jones (Eds.), 132–147. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2009). Modal density and modal configurations: Multimodal actions. In: Routledge Handbook for Multimodal Analysis, C. Jewitt (Ed.), 86–99. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2010). Tempo, Auftakt, levels of actions, and practice: Rhythms in ordinary interactions. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(3):333–356.10.1558/japl.v6i3.333Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2011). Identity in Interaction: Introducing Multimodal Interaction Analysis, Vol. 4. London: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9781934078280Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2013). What is a mode? Smell, olfactory perception, and the notion of mode in multimodal mediated theory. Multimodal Communication, 2(2):155–169.10.1515/mc-2013-0008Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2014). The impact of literacy-based schooling on learning a creative practice: Modal configurations, practices and discourses. Multimodal Communication, 3(2):181–195.10.1515/mc-2014-0011Suche in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (in press). Interaction – Language in multimodal action. In: Handbook “Language in Multimodal Contexts”, N.-M. Klug and H. Stöckl (Eds.). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Pirini, J. (2013). Analysing business coaching: Using modal density as a methodological tool. Multimodal Communication, 2(2):195–215.10.1515/mc-2013-0010Suche in Google Scholar

Pirini, J. (2014). Producing shared attention/awareness in high school tutoring. Multimodal Communication, 3(2):163–179.10.1515/mc-2014-0012Suche in Google Scholar

Pirini, J. (2015). Research into Tutoring: Exploring Agency and Intersubjectivity (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Auckland, NZ: AUT University.Suche in Google Scholar

Rommetveit, R. (1974). On Message Structure. London: Wiley.Suche in Google Scholar

Rommetveit, R. (1979). On the architecture of intersubjectivity. In: Social Psychology in Transition, L. H. Strickland, F. E. Aboud, and K. J. Gergen (Eds.), 201–214. Springer US. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4615-8765-1_1610.1007/978-1-4615-8765-1_16Suche in Google Scholar

Sacks, H. (1987). On the preferences for agreement and contiguity in sequences of conversation. In: Talk and Social Organisation, G. Button and J. R. E. Lee (Eds.). California: Multilingual Matters.Suche in Google Scholar

Scollon, R. (1998). Mediated Discourse as Social Interaction: A Study of News Discourse. London; New York: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Scollon, R. (2001). Mediated Discourse : The Nexus of Practice. London; New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203420065Suche in Google Scholar

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Wertsch, J. V. (1984). The zone of proximal development: Some conceptual issues. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1984(23):7–18. http://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219842303http://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219842303Suche in Google Scholar

Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Wertsch, J. V. (1998). Mind as action. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195117530.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

White, P. (2012). Multimodality’s challenge to marketing theory: a discussion. Multimodal Communication, 1(3):305–323.10.1515/mc-2012-0017Suche in Google Scholar

©2016 by De Gruyter Mouton

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Intersubjectivity and Materiality: A Multimodal Perspective

- Multimodality, Cognitive Poetics, and Genre: Reading Grady Hendrix’s novel Horrorstör

- Matt Kish’s “Every Page of Moby-Dick, Illustrated”: A Multimodal Approach

- The Participatory Stance of the White House on Facebook: A Critical Multimodal Analysis

- Multimodal Humor in Plenary Lectures in English and in Spanish

- Book Reviews

- Archer, A., and Breuer, E.: Multimodality in Writing: The State of the Art in Theory, Methodology and Pedagogy

- Koike, D. A and Blyth, C.S.: Dialogue in Multilingual and Multimodal Communities

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Intersubjectivity and Materiality: A Multimodal Perspective

- Multimodality, Cognitive Poetics, and Genre: Reading Grady Hendrix’s novel Horrorstör

- Matt Kish’s “Every Page of Moby-Dick, Illustrated”: A Multimodal Approach

- The Participatory Stance of the White House on Facebook: A Critical Multimodal Analysis

- Multimodal Humor in Plenary Lectures in English and in Spanish

- Book Reviews

- Archer, A., and Breuer, E.: Multimodality in Writing: The State of the Art in Theory, Methodology and Pedagogy

- Koike, D. A and Blyth, C.S.: Dialogue in Multilingual and Multimodal Communities