Abstract

Since George Lucas’s film A New Hope was first screened in 1977, the Star Wars saga has become a pop-culture phenomenon incorporating films, videogames, books, merchandise, and a quasi-religious philosophy, but linguistic research on Star Wars is scarce and has mainly focused on language use in the films. There is as yet no investigation of the impact of Star Wars on the English language, and the present study fills this gap using corpus-linguistic methods to investigate the extent to which characteristic words and constructions from the Star Wars universe have become established in English. Five Star Wars-derived items included in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), namely Jedi, Padawan, lightsabre (with spelling variants), Yoda, and the characteristic construction to the dark side were analysed regarding their frequency of occurrence in four corpora of present-day English (COCA, COHA, BNC, BNC Spoken 2014) and coded regarding their level of independence from the original films. The results show that over one-third of the uses of the investigated Star Wars-derived items are innovative (like the BNC example Other imbibers have gone over to the dark side of beer, rejecting the pasteurised lager produced by the breweries) and thus well integrated into the English language.

1 Introduction

For many users, popular culture represents an important aspect of their everyday life – and thus also of their everyday linguistic input. Fans who watch series like The Simpsons or Star Trek over a long period of time are therefore highly familiar with the main characters’ repeated catchphrases, such as Homer Simpson’s “D’Oh” or Mr. Spock’s “Live long and prosper”. Through frequency of exposure and salience, these catchphrases are stored in the language users’ minds and thus, through their entrenchment in the users, become part of the language in general (cf. Schmid 2020). Their widespread use and popularity means that the catchphrases can be alluded to, for example, in jokes, newspaper headlines, or memes such as “Live long and prospurr” (where Mr. Spock is petting a cat; Leroy 2022). To understand the point, readers need to be familiar with and recognize the original catchphrase. However, the linguistic items in question are usually full sentences or interjections (cf., e.g., the list of the 100 greatest catchphrases in TV compiled by TV Land cable network; Associated Press 2006); they are linked to one particular character, for example, from a popular-culture film; and through their use the original context is evoked on purpose. In this sense they differ from neologisms entering a language, since the widespread use of individual words in many different contexts usually makes it necessary for successful new words to become (more) independent from their original context of coinage. This is possibly also the reason why Crystal (2011: 249–250) concludes that while “films have introduced hundreds of catchphrases into English, such as Make my day! and May the Force be with you”, they have only occasionally provided “new words, or new senses of old words”. One of the few counterexamples he mentions is the word mini-me (“a person closely resembling a smaller version of another” according to Crystal’s 2011: 250 definition). This word with now widespread use in fashion, where it typically refers to mothers and their little daughters with matching clothing (e.g., Pursglove 2020), originates in the Austin Powers films – and one may assume that most celebrities and their followers indulging in mini-me fashion are unaware of the term’s origin lying in the name of Dr. Evil’s clone in the Austin Powers films.

The importance of popular culture as the subject of empirical linguistic research is increasingly recognized in recent publications about linguistic aspects of popular culture (e.g., Schubert and Werner 2022; Werner 2018). However, one very important universe is still barely explored – that of the Star Wars saga, an “epic space-opera media franchise” (Wikipedia 2022a) whose core consists of the three films A New Hope (1977), The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and Return of the Jedi (1983) as well as three prequels (1999–2005) and three sequels (2015–2019). This is highly surprising in view of the fact that the Star Wars universe is extremely widely known, that it already encompasses the second generation of viewers, and that it has expanded considerably ever since Disney obtained the rights for the Star Wars franchise, both in terms of spin-offs like Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016) and the series The Mandalorian (since 2019) and in terms of the increased amount of merchandise in the form of toys and theme park attractions (such as Galaxy’s Edge in Disneyland; Wikipedia 2022b). The Star Wars saga is much more than a simple worldwide box office success, as this pop-culture phenomenon incorporates films, computer games, books, and merchandise, and the most ardent fans even understand Star Wars as a quasi-religious philosophy (see Davidsen 2016). Still, the search for “Star Wars” in the Scopus database reveals that linguistic research on Star Wars is only a relatively recent phenomenon and that it mainly focuses on language use in the films themselves (e.g., Yuliyana and Bram’s 2019 syntactic analysis of Master Yoda’s unusual word order; Allen’s 2019 onomastic analysis of the characters’ names in the spin-off Star Wars Rebels; and Kleiven’s 2021 study of attitudinal language use).

There is as yet no research on the extent to which words and constructions from Star Wars have become part of the English language and are used in present-day English beyond the confines of their original usage context. The present study therefore fills this gap by investigating the domains in which Star-Wars-derived words and constructions occur in actual speech data as recorded in corpora of present-day English. The assumption underlying this research is that the establishment of lexical items and constructions from popular culture in the English language should be reflected (a) in their general frequency of use in general-language corpora and (b) in their use in contexts and with meanings without direct reference to the films and books that they originate from.

2 Star Wars-derived words and constructions in present-day English corpora

2.1 Material

The Star Wars universe offers a large range of characteristic vocabulary items that could be considered in an empirical study, such as Wookie, Death Star, X-wing, TIE fighter, carbonite, droid, Millennium Falcon, Ewok, or Endor. Many of the characteristic items are names of characters or places in the Star Wars universe, or relate to starships, weapons, or other aspects of technology. However, it is not uncommonly the case that some words from technical language registers become part of general language – for example, vaccine (from medicine) or combustion (from chemistry).

To investigate vocabulary with sufficiently high frequency, the empirical study reported here is based on three entries that were added to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in its October 2019 update (OED 2019) with some coverage in the press and sci-fi forums (e.g., Rayne 2019) shortly before the release of the film The Rise of Skywalker (Dent 2019), namely Jedi, lightsabre, and Padawan. The OED subentry for the Force was disregarded due to the amount of noise expected. This sample was complemented by dark side (which was added to the OED in December 2021) in the characteristic construction to the dark side, and by Yoda, for which there has been an OED entry since 2016.

2.2 Corpora

These target items were searched in their unlemmatized, case-insensitive base form in four corpora to yield the number of occurrences of each item (presented in Table 1):

the British National Corpus (2007 XML edition; BNC)

the spoken component of the British National Corpus 2014 (BNC Spoken 2014)

the Corpus of Historical American English (2019; COHA)

Number of occurrences of the unlemmatized Star Wars items across corpora.

| Star Wars item | BNC | BNC Spoken 2014 | COCAa | COHA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jedi | 14 | 10 | 4,478 | 290 | 4,792 |

| light sabre | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 9 |

| light saber | 0 | 0 | 105 | 8 | 113 |

| light-sabre | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| light-saber | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| lightsabre | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| lightsaber | 0 | 2 | 805 | 60 | 867 |

| Padawan | 0 | 1 | 291 | 61 | 353 |

| Yoda | 3 | 24 | 899 | 85 | 1,011 |

| to the dark side | 4 | 1 | 545 | 33 | 583 |

| Total | 22 | 38 | 7,153 | 539 | 7,752 |

-

aThe total number of hits for Jedi in the COCA webtool is 4,478, but not all hits are listed in the webtool’s results list with context, which is required for the manual annotation. For instance, the hits with the numbers 104, 114, and 124 are missing, so that the number of COCA KWIC list lines that could be used for further processing here was only 4,423.

In view of possible alternative spellings of the word light + sabre/saber – following British or American conventions regarding the final two letters; and using hyphenation, spacing or concatenation (cf. Sanchez-Stockhammer 2018) – the corpora were systematically searched for all spelling variants of the word.

2.3 Method

With a view to the systematic annotation and analysis of the data across corpora, the KWIC lists retrieved from the online corpus query tools were copied into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for further processing of the keywords with their surrounding context.

To ensure diffusion and prevent repeated use inside the same text from skewing the results, the data was filtered by applying Excel’s duplicate-deleting function either to the column with the identifiers of individual texts in the corpus (for BNC and BNC Spoken 2014) or to the column with information on the source (i.e., the URL for COCA and COHA).

For each search item with more than 100 hits in a specific corpus, a random sample of 100 hits was selected by using the Excel random number generator, sorting the random numbers by size and keeping the first 100 hits. If there were fewer than 100 hits in a specific corpus, all instances were considered (see Table 2). To ensure comparability, the sample light + saber was drawn exclusively from the instances with the spelling lightsaber, which is most common in all corpora (except the BNC, whose single hit with the spelling light sabre was not considered following the orthographic restriction). Due to overlap in random samples from COCA and COHA, 36 out of 643 contexts are included twice in the data set.

Number of items per corpus that were annotated with regard to usage context.

| BNC | BNC Spoken 2014 | COCA | COHA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jedi | 7 | 8 | 100 | 67 | 182 |

| lightsaber | 0 | 2 | 100 | 22 | 124 |

| Padawan | 0 | 1 | 40 | 6 | 47 |

| Yoda | 2 | 8 | 100 | 49 | 159 |

| to the dark side | 4 | 1 | 100 | 26 | 131 |

| Total | 13 | 20 | 440 | 170 | 643 |

The resulting sample of usage contexts was manually annotated in a separate column of the Excel spreadsheet to indicate the membership of each context in one of five categories, described below with their most important subcategories.

In the process of coding, ample use was made of the extended context of the samples to achieve a high level of accuracy in the categorization. As is usually the case in categorization, there were borderline cases, but each item was only assigned to the one category that represented the most likely interpretation. For increased readability, the Star Wars items were printed in bold in the corpus examples below.

2.3.1 No or unclear reference to Star Wars (N)

In cases of the first category, there is no reference to Star Wars, as can be seen in the literal use of the construction to the dark side in (1) or in the film title in (2). In other contexts, such as (3), the reference to Star Wars is unclear (e.g., due to a common cognitive metaphor relating darkness to evil).

| The house was dark on that side. […] He walked round the house. One room was lighted, on the other side. […] Gorm Smallin went back to the dark side . (COHA) |

| Taxi to the dark side (COHA) |

| If we pull in money from some dirty source or so-called borrow it from an unsuspecting, innocent source, and we open ourselves up to the dark side . (COHA) |

Instances in this category were disregarded in the analysis of the impact of Star Wars on the English language.

2.3.2 Reference to Star Wars films or texts as films or texts (= focus on form; F)

The contexts in cases in the second category suggest a direct reference to the Star Wars films; for example, the very frequently used title seen in (4). The category also includes the titles of other fictional texts from the Star Wars universe (like film scripts), as in (5).

| “Return of the Jedi ” is the Best Star Wars Movie of All Time (COCA) |

| Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi -- Omen is the second in a nine-book series (COCA) |

Items in this category may refer to the filming process, as in (6). This is also the case when the names of the actors are mentioned in a usage context, as shown in (7).

| now you know Yoda is obviously a CGI (COCA) |

| with Rey (Daisy Ridley) handing a lightsaber to perhaps the only remaining Jedi in the galaxy: an elderly Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) (COHA) |

This category includes references to the target items being shown or viewed on the screen, as in (8); more indirect references to the visuals of the films’ images, as in (9); and references that focus on visual aspects of the Star Wars universe that are related to the films’ images, as in (10).

| by the time Master Yoda steps up to Count Dooku and represents for the Jedi, you’ll wonder why you were squirming in your seat an hour ago (COHA) |

| You’re short. – Short! You remember Yoda ? (COCA) |

| a three-headed mutant that looks like Yoda (COCA) |

The items in this category are all intertextual and tend to focus on form. They represent the lowest level of integration of Star Wars items into the English language.

2.3.3 References to the Star Wars universe (= focus on content; U)

Items in this category refer to the Star Wars universe in discussing content from the relevant films, books, or fan fiction, as in (11).

| On Yavin 4 Luke Skywalker has formed an academy to reestablish the Jedi Knights, former guardians of the Old Republic. (COCA) |

This may involve accounts provided by a narrator, as in (12), but also discussions of what particular characters from the Star Wars saga said or might say, as in (13), including alleged quotes, such as that found in (14) – in contrast to Yoda’s actual quote: “Try not. Do. Or do not. There is no try.”

| Luke starts to gather force attuned students. Befriends a promising student-takes him as his padawan . (COCA) |

| Gandhi did not say that. Somebody like Gandhi said that. […] It might have been Yoda . (COHA) |

| Yoda says there is no try, only do. (COCA) |

This category also covers metalinguistic uses, such as (15):

| you probably don’t need to explain what a Jedi is in every new book or film (COCA) |

The items in this category take the existence of the Star Wars universe for granted and imply the (quasi-real) existence of characters like Yoda, as reflected in (16), or of concepts like Jedihood. The usage contexts in category U thus differ from the usage contexts in category F (where one can always discern a reference to a film or text with an author, actors, visual effects, and so on).

| P.S. Are you related to Yoda? (COCA) |

2.3.4 Reference to Star Wars merchandise or real-world objects (M)

Other uses of the target items may refer to Star Wars merchandise and real-world objects such as video games (17) or toys (18):

| I will have to turn off the sound because my Padawan is annoying. (COCA) |

| dueling with Star Wars’ lightsaber is now an actual sport. (COCA) |

We also find references to visual artwork (with the exception of film, which is covered by the category F), as in (19), whose wider context situates it at an exhibition, and references to other objects, as in (20).

| My favorite was one showing Han Solo as a bearded lightsaber wielder. (COCA) |

| A lightsaber used in the original Star Wars was bought for $200,000 at a recent auction. (COHA) |

This also includes references to (people wearing) Star Wars-derived costumes:

| The union of a storm trooper and a Jedi princess? (COHA) |

For the usage contexts in this category, objects or practices from Star Wars have become part of the real world, with the ensuing physical and economic consequences (like enabling a real person to touch the objects).

2.3.5 Innovative use of Star Wars-derived items in the real world (I)

The most interesting category for the present study comprises the use of Star Wars-derived words and constructions in new contexts. This may involve innovative uses such as the metaphorical uses in (22) and (23).

| I’m afraid of his sensual powers. Ryan, the man is a sexual Jedi . Whatever he asks you to do, you just do it. (COCA) |

| I was taking pain pills and doing cocaine and I’m a Jedi apparently because I could take enormous amounts of it. (COCA) |

Star Wars-related concepts may be integrated into the real world as if they were real (even though it may be done jokingly), such as in the discussion of tools in (24).

| “Now if you could get me one of those light swords” # [1] “ Lightsaber ,” Gene corrected. (COHA) |

This category also covers the combination of Star Wars-derived items with other fictional universes, such as those of Peter Pan in (25) and Game of Thrones in (26).

| Tinkerbell with a lightsaber ? (COCA) |

| Someone please give Arya Stark (er, “no one”) and her staff the Darth Maul lightsaber treatment. (COHA) |

The items in this category testify to the integration of Star Wars-derived vocabulary and constructions into the English language, as the surrounding context is not related to Star Wars at all. This can be seen, for example, in various uses that deal with human relationships:

| So how do you hold on to your Zen when your husband’s in a bad mood? […] To get him to sync with you (and not you with him), just sit back and let your good vibes work a Jedi mind trick on him. If this is an ongoing issue, wait till he’s calm, then talk long-term stress relief (COCA) |

| Wow! That’s how it’s done, young Padawan . – Nice. – Going on a date next week. Things are looking up for Cisco Ramon. (COCA) |

3 Results and discussion

Table 1 provides an overview of the total number of occurrences of Jedi, lightsaber (with spelling variants), Padawan, Yoda, and to the dark side in BNC, BNC Spoken 2014, COCA, and COHA. With a total of 7,752 uses in the corpora under consideration, one may draw the conclusion that Star Wars-derived words and constructions are frequent enough to constitute a relevant phenomenon for general English.

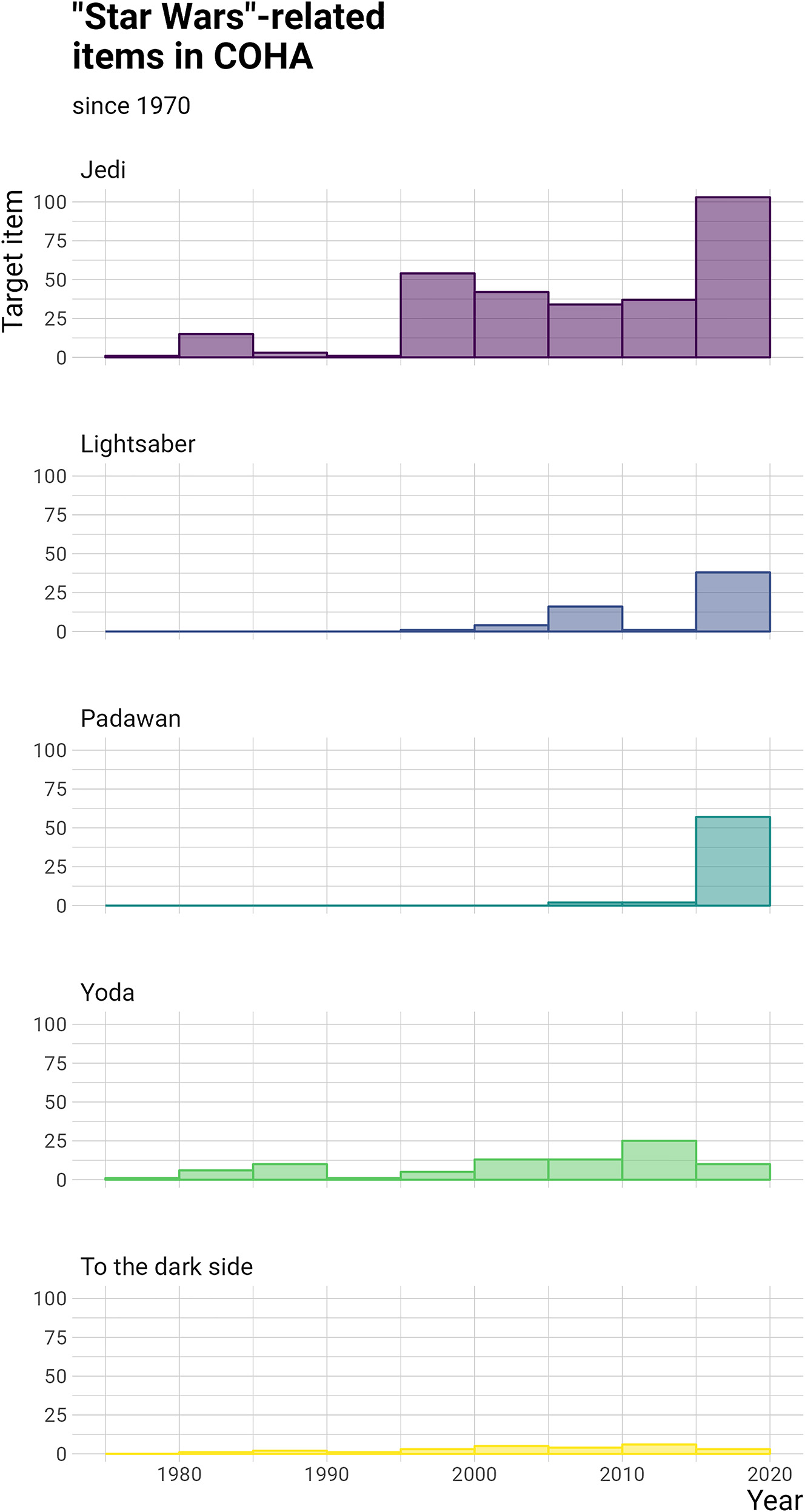

If we examine the frequency of use of the Star Wars-derived items across time, as is done in Figure 1 for all COHA hits (including repeated hits within the same document) of all search items for five-year periods, we notice an increase in the use of Jedi, lightsaber, and particularly Padawan, whereas the frequencies of Yoda and to the dark side are more evenly distributed.

Diachronic development: Frequency of Star Wars-derived items in COHA (1975–2020).

The first six uses of Jedi in COHA (from 1978 to 1984) all refer to the films – either by direct reference to the film title Return of the Jedi, to the films’ actors, as in (29), or to the filming process, as in (30).

| Even that unflappable knight of the Jedi , Obi-Wan Kenobi-otherwise known as Sir Alec Guinness (COHA) |

| an 800-year-old guru gnome who teaches the Jedi way and who has been so finely put together by Frank Oz (COHA) |

In the late 1990s, the COHA uses of Jedi are characterized by a large number of references to fan fiction or the Star Wars books. The picture then becomes more mixed, until the 2017 release of the eighth film in the franchise, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, makes references to the film title dominate the final years of the COHA sample again.

Lightsaber, by contrast, begins with many contexts of use that are related to Star Wars content – that is, fictional texts. It is only later that merchandising becomes more important on such a scale that it eventually becomes the dominant category.

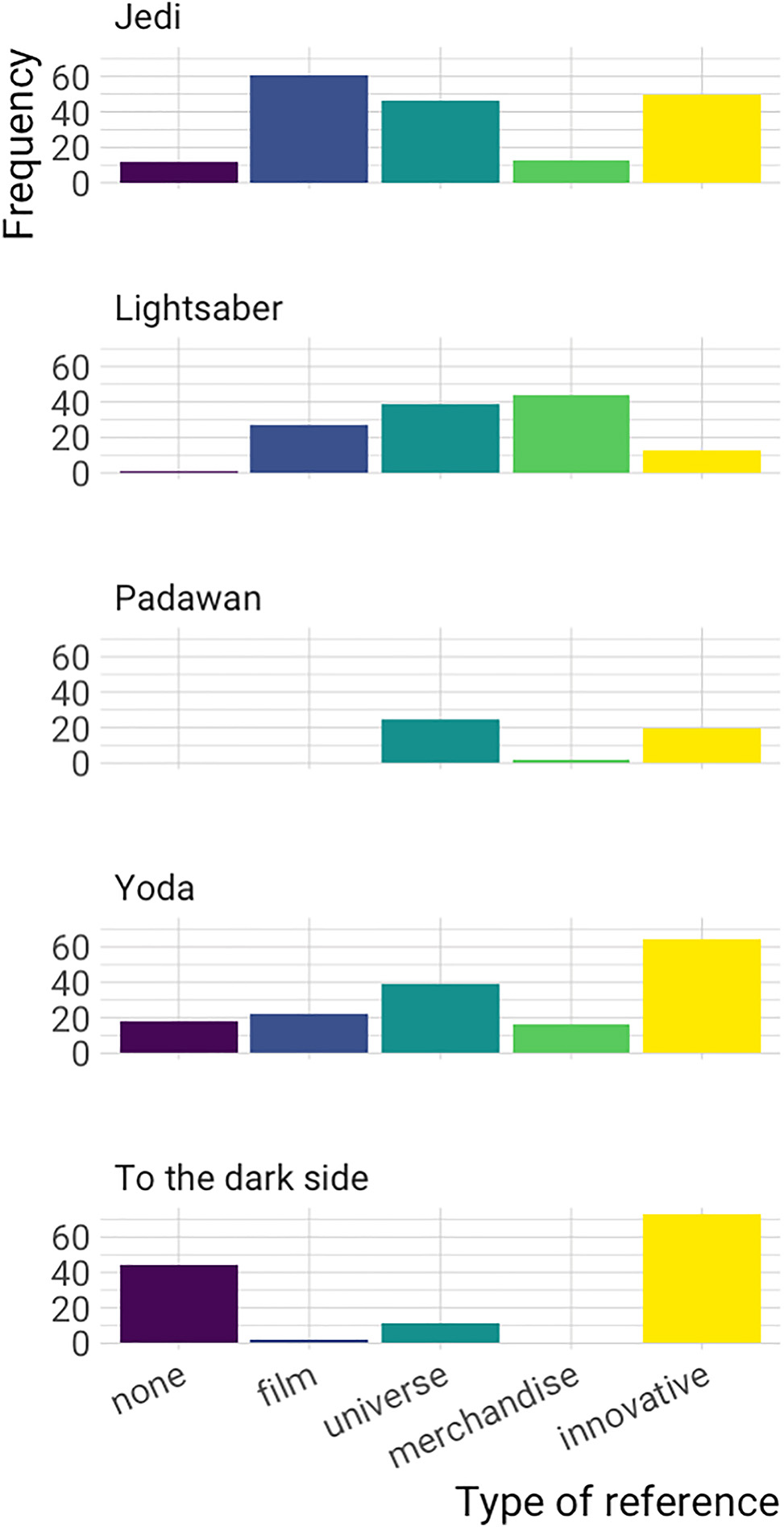

As regards the contexts in which the Star Wars-derived items are used in the various corpora of present-day English, Table 3 in the Appendix provides an overview with examples for all categories. Figure 2 shows that the items differ in the extent to which they are used in more Star Wars universe-related or more innovative contexts.

Type of reference in the use of Star Wars-derived items (BNC, BNC Spoken 2014, COCA, and COHA).

To the dark side stands out regarding the large number of unrelated or unclear uses. This is due to the archetypal association of darkness with something negative, as seen in (31):

| the Dark Knight owes much of his force of will to the dark side in all of us (COCA) |

Interestingly, however, none of the COHA hits for to the dark side from the time before Star Wars has this archetypal association of becoming immoral or evil (see Table 4). This permits the tentative explanation that at least in this particular construction, the archetypal use that we now experience as common or usual is a consequence of the use of to the dark side in the Star Wars films and the subsequent discourse.

Many corpus hits for Jedi are direct references to the film title Return of the Jedi, and lightsaber stands out in the extent to which it is used in contexts referring to merchandise. A new generation is now using lightsabres as toys representing a concept that is part of a shared cultural background, even in cases where neither the children nor their parents have watched the Star Wars films.

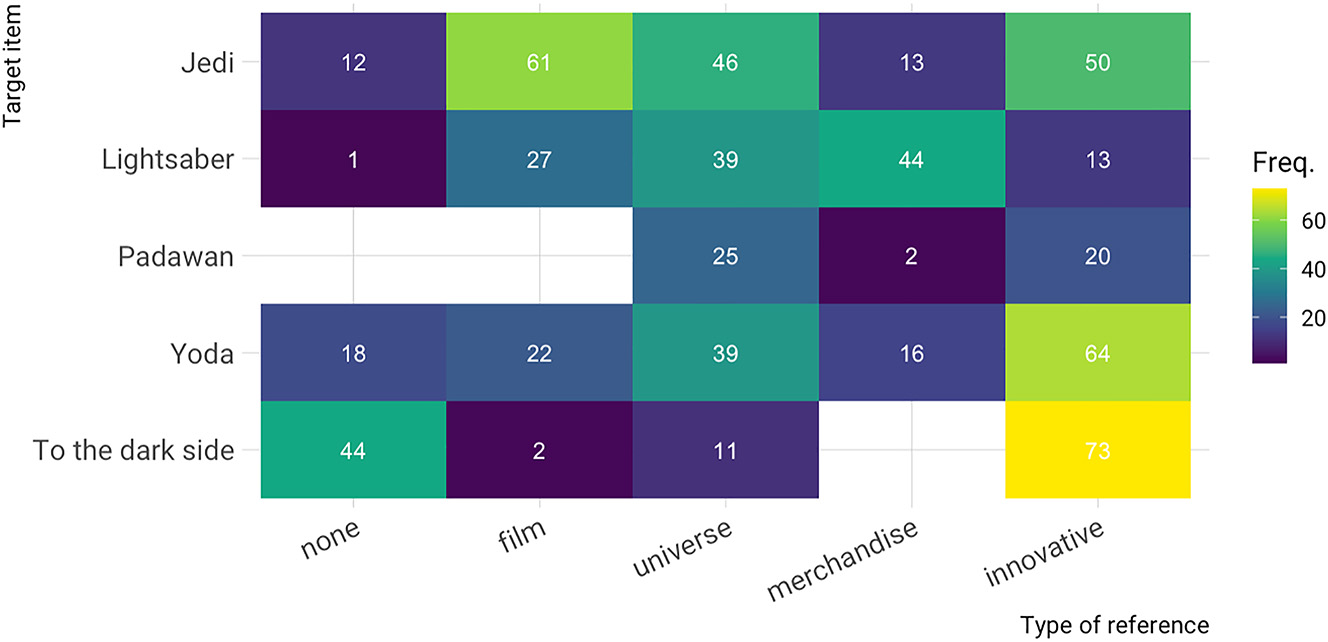

What also becomes immediately obvious from Figure 2 is the large number of items in the last category with innovative uses. The heatmap in Figure 3 shows that innovative uses of to the dark side represent the largest category (n = 73).

Heatmap for the type of reference in the use of Star Wars-derived items across corpora (BNC, BNC Spoken 2014, COCA, and COHA).

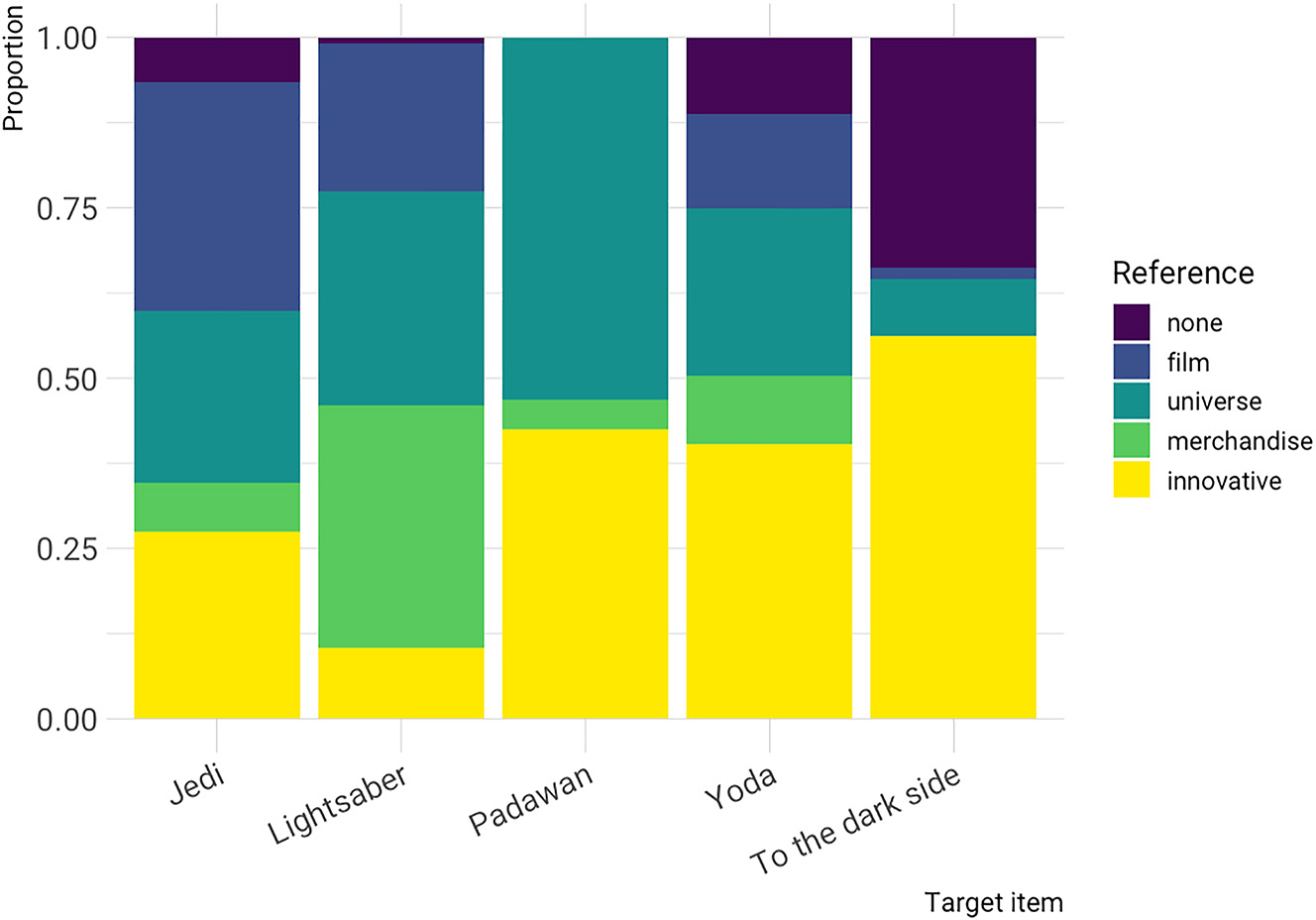

If the relative proportions of use in the categories are considered (see Figure 4), we find that to the dark side leads with more than 50 % innovative uses, followed by Padawan and Yoda.

Proportion of use types by Star Wars items (across BNC, BNC Spoken 2014, COCA, and COHA).

Of the innovative uses of to the dark side, many are related to professional contexts, as seen in (32) and (33). These usages suggest that some types of job have a bad reputation among particular restricted groups (of which developers are mentioned more than once as succumbing to the dark side and changing their job), and the dark side is associated with a higher income in many of these cases.

| Well, one developer, Rob Spectre, recently crossed over to the dark side -- marketing -- and posted an account of what he learned over there. (COCA) |

| he’s now moved to the Dark Side and become an apprentice to the moneyed elite (COCA) |

Another recurring context is a switch of brand in a particular hobby:

| after owning jets for the last 16 years went to the dark side and bought a Campbell v-drive daycruiser. (COCA) |

| Went to the dark side and bought a 5D [= Canon EOS 5D] # After years of shooting with Olympus exclusively (COCA) |

Otherwise, the expression is used in such diverse contexts as children’s behaviour, hockey playing, politics and playful advertising, for example in (36).

| Cross over to the dark side when it comes to nibbling on chocolate. (COCA) |

Padawan is used in COCA in innovative contexts to refer to different types of people, such as iTunes library novices, theological or political discussants, graduate students, and so on. The topics range from racing, motorbiking, and baseball to dressing style, dating, and successful communication, so that it can be considered very general in its meaning. It almost always occurs in combination with my or young, as in (37).

| We sat down with Boorman and the young Padawan learner in the London garage where they store their bikes. (COCA) |

This use implies that the speakers put themselves in the position of a Jedi Master or an analogous higher-order mentor teaching a disciple the ropes. A considerable number of hits for Padawan in COCA are lower case, which implies a generalization of the term, for example in (38).

| There is a bit more to it such as matching their body language and other techniques but I think this will do you just fine young padawan . (COCA) |

Many of the Yoda uses are about mentorship and wisdom, and they often quote Yoda or modify his quotes:

| To take a phrase from Yoda , “spam does not make one great.” (COCA) |

| to paraphrase Yoda , “Touch or touch not. There is no hover” (COCA) |

Many instances use a or the with Yoda, as in (41) and (42), and there are even uses with a personal pronoun, like in (43) and (44). This also seems to suggest a frequent generalized use of the term.

| the Yoda of sex (COCA) |

| a hardware Yoda (COCA) |

| Unlike Luke Skywalker in a Star Wars sequel, we may never meet our Yoda . (COCA) |

| referred to Angel as both his “sire” and his “ Yoda ,” (COCA) |

We can thus see that the outside-of-Star Wars uses of the search items depend on their possible level of semantic abstraction. Many of the uses can be considered metaphorical extensions of the original meaning or reference; for example, when Yoda is used to refer to a mentor or wise expert, or when Jedi is used for a skilled person and Padawan for someone who is being taught a lesson. Lightsabre stands out in this respect as the only physical object with many uses referring to battles with toys, and to the dark side as part of a construction with an introductory verb that expresses a change to a state that is evaluated (or known to be evaluated) as less virtuous.

4 Summary and conclusion

Language in science fiction often aims at estrangement (cf. Adams 2017), but director George Lucas mentioned in interviews that he wanted to create a “used universe” in his Star Wars films (Arango 2018) – with all the implications that this has regarding the familiarity of the setting for the viewers. This also seems to extend to the language used in the Star Wars films, some of which has become institutionalized (so that a lexical item is recognized by other speakers as known and thus item-familiar; cf. Bauer 1983: 48).

The corpus study reported here finds a substantial amount of Star Wars-related material, both vocabulary and constructions, in English-language corpora, with over one-third (34.3 %) of the annotated tokens showing innovative uses. The items in these contexts of use have arguably reached the highest level of integration into the English language through their relative independence from the Star Wars universe (which is taken for granted as a shared cultural background). These metaphorical extensions, whose status as general-language items in everyday discourse is often underlined by lower-case spelling, are complemented by another 11.7 % of usage contexts referring to merchandise or other real-world objects or concepts derived from the Star Wars saga. The data also suggests that the construction to the dark side has only been used with moral overtones since the advent of the Star Wars franchise.

We can therefore conclude from the corpus study that Star Wars has not only had an important and still ongoing impact on popular culture but also on the English language, in the sense that a substantial number of words and constructions from a galaxy far, far away have already become an established part of the English vocabulary.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Katharina Maschke and Melanie Braun for their help with the collection and processing of the data from the OED and various corpora. Special thanks to Asya Yurchenko for her great support with the graphics and to Tim Curnow for his valuable suggestions. Thank you very much as well to everyone who provided helpful feedback and inspiration during our involved discussions at the ICAME 43 conference in Cambridge.

Number of occurrences and example sentences for all types of Star Wars reference (across all corpora).

| Code | Type of reference to Star Wars | Number of occurrences | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | No or unclear reference to Star Wars

N = 75 (11.7 %) |

12 | The Dhedhi or Jedi was actually serpent of priests. (COCA) |

| 1 | This one not only had the demonic snarl, but came with lightsaber swinging action and sound effects. (COCA)a | ||

| 0 | (No examples of Padawan) | ||

| 18 | they completely outplayed Mika Yoda ’s Japanese team at the world junior championships (BNC)b | ||

| 44 | the Dark Knight owes much of his force of will to the dark side in all of us (COCA) | ||

| F |

Star Wars films or texts as films/texts (form) N = 112 (17.4 %) |

61 | “Return of the Jedi ” is the Best Star Wars Movie of All Time (COCA) |

| 27 | the lightsaber battles in “Episode III” are more like isometrics (COCA) | ||

| 0 | (No examples of Padawan) | ||

| 22 | The only actor with soul is Yoda , and he’s computer-generated. (COCA) | ||

| 2 | Could Rey turn to the Dark Side in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker? (COCA) | ||

| U |

Star Wars universe (content) N = 160 (24.9 %) |

46 | Vader was Dark Lord of the Sith, the scourge of the Jedi (COCA) |

| 39 | A lightsaber of antique-looking design was clipped to his belt. (COCA) | ||

| 25 | Obi-Wan Kenobi, Anakin Skywalker and his padawan Ahsoka Tano are stranded on a distant planet. (COCA) | ||

| 39 | Yoda says there is no try, only do. (COCA) | ||

| 11 | One will turn to the Dark side and destroy us all. (COCA) | ||

| M |

Star Wars merchandise or real-world objects N = 75 (11.7 %) |

13 | several companies that offer lightsaber combat and Jedi training classes for adults and children (COCA) |

| 44 | I have my lightsaber and my sci-fi toys (COCA) | ||

| 2 | I will have to turn off the sound because my Padawan is annoying. (COCA) | ||

| 16 | You see a Yoda doll, you take it. (COCA) | ||

| 0 | (No examples of to the dark side) | ||

| I | Innovative use of Star Wars-related items N = 220 (34.3 %) |

50 | Clancy, 50, is more than a finance Jedi . (COCA) |

| 13 | Dickie uses his sexuality as a lightsaber . I mean, it’s his power, you know. (COCA) | ||

| 20 | Be one with your external iTunes Library, young Padawan (COCA) | ||

| 64 | You’re a Yoda among cops. (COCA) | ||

| 73 | A developer crosses over to the dark side and learns marketing (COCA) |

-

aThe preceding and following nonsensical context in COCA led to classification of this example as N (even if M is also conceivable): “Adecco Group is the largest human resources company in the world, based in Glattbrugg, Switzerland. This one not only had the demonic snarl, but came with lightsaber swinging action and sound effects. Be sure to hop on over there and see what the buzz is about. Is again the figure from the Archaeopteryx” (from the website http://www.rachellegardner.com/2012/03/do-you-have-a-thick-skin/, which is no longer available). b Yoda is a Japanese surname (see, e.g., Katayama 2008). While a name change paying tribute to Star Wars cannot be entirely excluded, it was considered unlikely enough to legitimate exclusion of this item from the analyses.

Uses of to the dark side in COHA before the Star Wars films.

| Year | COHA example |

|---|---|

| 1861 | was not of this class. He had no desire to turn exclusively to the dark side , to dwell upon faults and foibles, or to waste life in unreasonable |

| 1867 | [“]They’ll eat like young hyenas!” Gorm Smallin went back to the dark side . A low window was open. He pulled off his shoes and climbed |

| 1868 | annoyance. She was one of those happy natures who prefer the bright to the dark side of the picture -- and generally have it -- for in truth more shadows |

| 1915 | where the animal “breaks down”? i.e., goes as often to the dark side as to the light side. This point gives us the limit of spectral |

| 1939 | Here, avoiding the glare of the great crackling fires, she rode to the dark side of the yurts. She dismounted from her horse, and stood motionlessly in |

| 1952 | burned above the entrance, sparkling the snow. I crossed the alley to the dark side , stopping near a fence that smelled of carbolic acid, which, as |

| 1958 | hidden persuaders and singing commercials make Huxley think man is being nudged closer to the dark side of the moonstruck world he once described. # His other examples range from |

References

Adams, Michael. 2017. The pragmatics of estrangement in fantasy and science fiction. In Miriam A. Locher & Andreas H. Jucker (eds.), Pragmatics of fiction, 329–363. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110431094-011Search in Google Scholar

Allen, Spencer L. 2019. A rebel by any other name: The onomastics of Disney’s Star Wars Rebels. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 31(1). 72–86. https://doi.org/10.3138/jrpc.2017-0020.Search in Google Scholar

Arango, Jorge. 2018. Prototypes and the used universe. Medium, 12 December. https://jarango.medium.com/prototypes-and-the-used-universe-d3580bfdafd (accessed 6 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Associated Press. 2006. TV Land lists the 100 greatest TV catchphrases. Fox News, 28 November; updated 13 January 2015. https://www.foxnews.com/story/tv-land-lists-the-100-greatest-tv-catchphrases (accessed 6 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Bauer, Laurie. 1983. English word-formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139165846Search in Google Scholar

BNC Spoken. 2014. The spoken component of the British National Corpus 2014, released in 2017. Available at: https://cqpweb.lancs.ac.uk/bnc2014spoken/.Search in Google Scholar

British National Corpus (XML edition). 2007. https://cqpweb.lancs.ac.uk/bncxmlweb/.Search in Google Scholar

Corpus of Contemporary American English. 2019. https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/ (accessed February–March 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Corpus of Historical American English. 2019. https://www.english-corpora.org/coha/ (accessed February–March 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Crystal, David. 2011. The story of English in 100 words. London: Profile.Search in Google Scholar

Davidsen, Markus Altena. 2016. From Star Wars to Jediism: The emergence of fiction-based religion. In Ernst van den Hemel & Asja Szafraniec (eds.), The future of the religious past, 376–389. New York: Fordham University Press.10.2307/j.ctt1bmzp8v.23Search in Google Scholar

Dent, Jonathan. 2019. These ARE the words you are looking for: The OED October 2019 update. OED Blog. https://public.oed.com/blog/new-words-notes-for-october-2019/ (accessed 18 July 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Katayama, Lisa. 2008. Japanese with common last name Yoda denied Facebook account. Boing Boing (blog), 26 August. https://boingboing.net/2008/08/26/japanese-with-last-n.html (accessed 22 December 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Kleiven, Ragnhild Fimreite. 2021. May the accent be with you: An attitudinal study of language use in the Star Wars trilogies. Bergen: University of Bergen Master thesis. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2760489.Search in Google Scholar

Leroy, Kath. 2022. 15 Spock memes only true Star Trek fans will understand. GameRant. Updated 14 April 2022. https://gamerant.com/star-trek-spock-memes-true-fans-understand/#animal-magnet (accessed 6 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

OED. 2019. October 2019: List of new and updated entries. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/information/updates/previous-updates/2019-2/october-2019 (accessed 4 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Pursglove, Anna. 2020. You’re not seeing double, the High Street’s gone mad for mother-and-daughter dressing. So brace yourself for … the MATCHY-MATCHY MINI MES. Daily Mail, 13 September. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-8728493/High-Streets-gone-mad-mother-daughter-dressing-brace-MINI-MES.html (accessed 18 July 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Rayne, Elizabeth. 2019. “Jedi” is now an official word in the Oxford Dictionary, so what does it really mean to be one? Syfy. https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/jedi-official-word-oxford-english-dictionary (accessed 17 July 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Sanchez-Stockhammer, Christina. 2018. English compounds and their spelling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108181877Search in Google Scholar

Schmid, Hans-Jörg. 2020. The dynamics of the linguistic system: Usage, conventionalization, and entrenchment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198814771.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Schubert, Christoph & Valentin Werner (eds.). 2022. Stylistic approaches to pop culture. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003147718Search in Google Scholar

Smiley, Bob. 2012. Don’t mess with Travis. New York: Thomas Dunne.Search in Google Scholar

Werner, Valentin (ed.). 2018. The language of pop culture. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315168210Search in Google Scholar

Wikipedia. 2022a. Star Wars. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Star_Wars (accessed 4 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Wikipedia. 2022b. Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Star_Wars:_Galaxy%27s_Edge (accessed 4 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Yuliyana, Yuliyana & Barli Bram. 2019. Uncommon word order of Yoda in Star Wars movie series: A syntactic analysis. NOBEL: Journal of Literature and Language Teaching 10(2). 103–116. https://doi.org/10.15642/nobel.2019.10.2.103-116.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction to the special issue on “The language of science fiction”

- The impact of Star Wars on the English language: Star Wars-derived words and constructions in present-day English corpora

- “To boldly go where no man has gone before”: how iconic is the Star Trek split infinitive?

- From Star Trek to The Hunger Games: emblem gestures in science fiction and their uptake in popular culture

- The language of men and women in Star Trek: The Original Series and Star Trek: Discovery

- “So, I trucked out to the border, learned to say ain’t, came to find work”: the sociolinguistics of Firefly

- Subverting motion in science fiction? Beam in the Star Trek TV series

- Perceiving with strangeness: quantifying a style of altered consciousness as estrangement in a corpus of 1960s American science fiction

- “There was much new to grok”: an analysis of word coinage in science fiction literature

- Cyberpunk, steampunk, and all that punk: genre names and their uses across communities

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction to the special issue on “The language of science fiction”

- The impact of Star Wars on the English language: Star Wars-derived words and constructions in present-day English corpora

- “To boldly go where no man has gone before”: how iconic is the Star Trek split infinitive?

- From Star Trek to The Hunger Games: emblem gestures in science fiction and their uptake in popular culture

- The language of men and women in Star Trek: The Original Series and Star Trek: Discovery

- “So, I trucked out to the border, learned to say ain’t, came to find work”: the sociolinguistics of Firefly

- Subverting motion in science fiction? Beam in the Star Trek TV series

- Perceiving with strangeness: quantifying a style of altered consciousness as estrangement in a corpus of 1960s American science fiction

- “There was much new to grok”: an analysis of word coinage in science fiction literature

- Cyberpunk, steampunk, and all that punk: genre names and their uses across communities