Abstract

In this paper we introduce the notion of Timing of Belief (ToB) as a relevant factor of variation in common ground (CG) management in sentence-peripheral particles across different languages. CG management traces the epistemic development of mutual beliefs between speaker and addressee. Evidence for the relevance of ToB comes from a small-scale acceptability study which tested the relevance of ToB for particles in English, German, and Spanish. While these languages all possess grammaticalized structures to encode different types of knowledge asymmetries between speaker and addressee, they vary with respect to the sensitivity or encoding of ToB. The evident relevance of ToB for CG management suggests that models which focus on the dynamic character of CG development require further expansion. We hope that the fine-graded differences in CG management reported here serve to inspire an engagement with the notion of ToB and the variation we find across languages and dialects.

Funding source: SSHRC Insight Grant (Towards a formal typology of confirmationals) Prof. Martina Wiltschko PhD

Appendix: Experimental stimuli

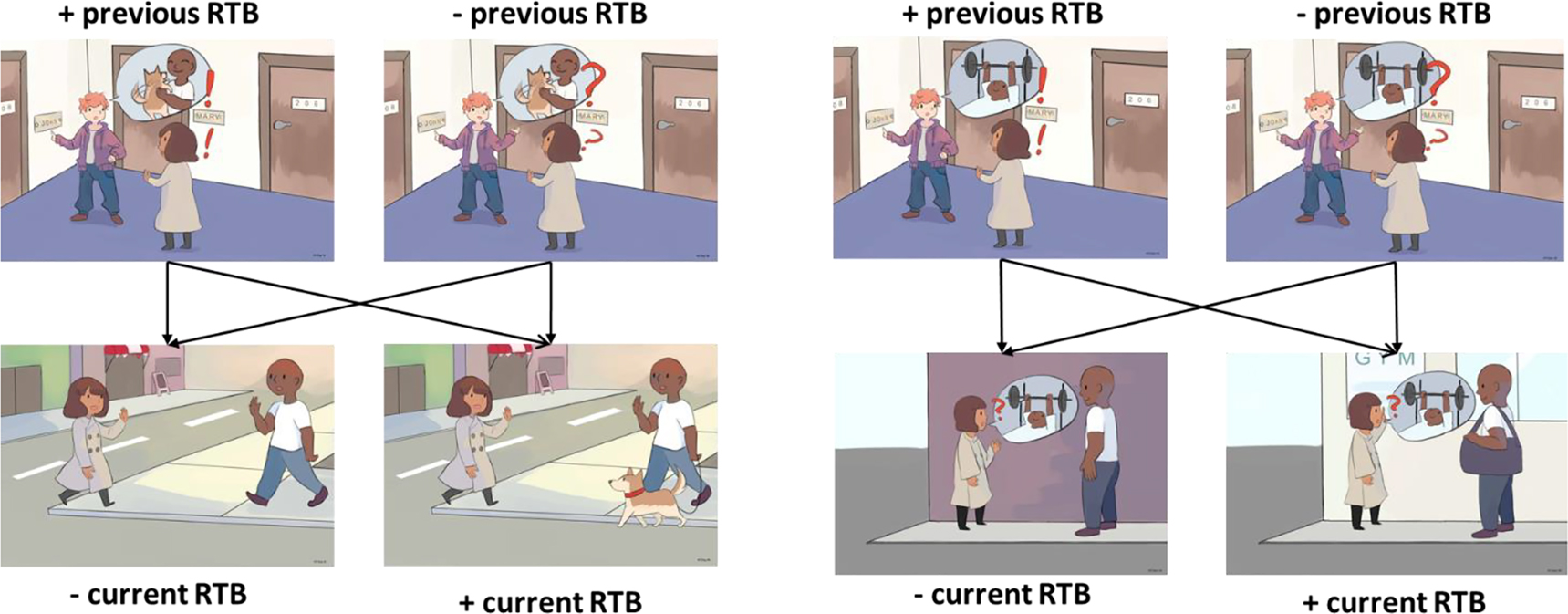

Stimuli configuration with (a) “new dog” context (b) “gym” context.

Experimental stimuli for the English survey

| (1) Text accompanying the panel with a previous RTB |

| John tells Mary that their common friend Greg has a new dog: |

| John: “Greg got a super cute new puppy dog!” |

| Mary: “Oh, I didn’t know. Nice!” |

| John tells Mary that their common friend Greg is now working out at Crossfit: |

| John: “Greg is getting super strong – he’s working out now!” |

| Mary: “Oh, I didn’t know – Nice! |

| (2) Text accompanying the panel without a previous RTB |

| John asks Mary whether their common friend Greg has a new dog: |

| John: “Hey, do you know: did Greg get a puppy?” |

| Mary: “Oh, I have no idea!” |

| John asks Mary whether their common friend Greg is working out these days: |

| John: “Hey, do you know if Greg is going to the Gym lately?” |

| Mary: “Oh, I have no idea!” |

| (3) Text accompanying the panels with and without a current RTB |

| Shortly after, Mary runs into Greg on the street. |

| Mary: “Hey Greg, how are you? You’ve got a dog now, eh?” |

| Shortly after Mary runs into Greg on the street. |

| Mary: “Hey Greg, how are you? You are working out now, eh?” |

Experimental stimuli for the German survey

| Text accompanying the panel with a previous RTB |

| Hans erzählt Maria, dass ihr gemeinsamer Bekannter Gregor jetzt im Crossfit trainieren geht. |

| Hans: “Gregor wird richtig stark, der trainiert jetzt auch.” |

| Maria: “Oh ja? Interessant!” |

| Hans erzählt Maria dass ihr gemeinsamer Freund Gregor einen neuen Hund hat. |

| Hans: “Gregor hat jetzt einen total süßen Hund!” |

| Maria “Oh ja? Interessant, er wollte ja immer schon mal einen Hund haben.” |

| Text accompanying the panel without a previous RTB |

| Hans fragt Maria ob ihr gemeinsamer Freund Gregor einen neuen Hund hat. |

| Hans: “Hat Gregor jetzt einen neuen Hund?” |

| Maria: “Hm, keine Ahnung, das weiß ich nicht.” |

| Hans fragt Maria, ob ihr gemeinsamer Bekannter Gregor jetzt auch ins Fitnessstudio geht. |

| Hans: “He, weißt du, ob der Hans trainieren geht? |

| Maria: “Hm, keine Ahnung, das weiß ich nicht.” |

| Text accompanying the panels with and without a current RTB |

| Am nächsten Tag begegnet Maria Gregor auf der Straße. |

| Maria: “Hallo Gregor, wie geht’s? Du hast jetzt einen Hund, gell?” |

| Am nächsten Tag begegnet Maria Gregor auf der Straße. |

| Maria: “Hallo Gregor, wie geht’s? Du gehst jetzt auch trainieren, gell?” |

Experimental stimuli for the Spanish survey

| Text accompanying the panel with a previous RTB |

| Juan le comenta a María que su amigo en común Greg tiene un perro nuevo: |

| Juan: “¡Greg tiene un perrito súpermono!” |

| María: “¡Qué me dices! ¡Qué bien!” |

| Juan le comenta a María que su amigo en común Greg está yendo al gimnasio: |

| Juan: “Greg está súper en forma, está yendo al gimnasio!” |

| María: “Oh, no lo sabía … ¡Guau!” |

| Text accompanying the panel without a previous RTB |

| Juan le pregunta a María si su amigo en común Greg tiene un perro nuevo: |

| Juan: “Oye, ¿sabes si Greg tiene un perrito?” |

| María: “Hmmm ¡ni idea!” |

| Juan le pregunta a María si su amigo en común Greg está yendo al gimnasio: |

| Juan: “Oye, ¿sabes si Greg está yendo al gimnasio últimamente?” |

| María: “Uy, ¡ni idea!” |

| Text accompanying the panels with and without a current RTB |

| Poco después María se encuentra a Greg por la calle: |

| María: “Hola, Gregor, ¿cómo te va? ¡Hace tantísimo que no nos vemos! Tienes un perrito, ¿no?” |

| Al día siguiente, María se encuentra a Greg en la calle. Greg lleva una bolsa de gimnasio: |

| María: “¡Hombre, Greg! ¿cómo estás? Estás yendo al gimnasio, ¿no?” |

References

Avis, Walter S. 1972. So eh? is Canadian, eh? Canadian Journal of Linguistics/Revue canadienne de linguistique 17. 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0008413100007039.Suche in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68(3). 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartels, Christine. 1997. Towards a compositional interpretation of English statement and question intonation. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts dissertation. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1997-833.Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Benjamin Bolker & Steven C. Walker. 2014. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1(7). 1–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Bavelas, Janet Beavin, Peter De Jong, Harry Korman & Sarah Smock Jordan. 2012. Beyond back-channels: A three-step model of grounding in face-to-face dialogue. In Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary Workshop on Feedback Behaviors in Dialogue 5–6. September 7–8, Stevenson, WA. Available at: http://www.cs.utep.edu/nigel/feedback/proceedings/full-proceedings.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Burton, Strang & Lisa Matthewson. 2015. Targeted construction storyboards in semantic fieldwork. Methodologies in Semantic Fieldwork. 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190212339.003.0006.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190212339.003.0006Suche in Google Scholar

Burton, Strang & Martina Wiltschko 2015. The geu vs. leicht problem. In: Short’schrift for Alan Prince. Compiled by Eric, Bakovic. https://princeshortschrift.wordpress.com/squibs/burton-wiltschko/.Suche in Google Scholar

Chafe, Wallace. 1976. Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects and topics. In Charles N. Li (ed.), Subject and topic, 25–55. New York: Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Clark, Herbert H. & Susan E. Brennan. 1991. Grounding in communication. Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition 13. 127–149.10.1037/10096-006Suche in Google Scholar

Columbus, Georgie. 2010. “Ah lovely stuff, eh?”—invariant tag meanings and usage across three varieties of English. In Gries Stefan, Wulff Stefanie & Mark Davies (eds.), Corpus-linguistic applications, 85–102. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789042028012_007Suche in Google Scholar

Farkas, Donca F. & Kim B. Bruce. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27(1). 81–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffp010.Suche in Google Scholar

Groenendijk, Jeroen & Floris Roelofsen. 2009. Inquisitive semantics and pragmatics. Paper presented at the Stanford workshop on Language, Communication and Rational Agency, May 30-31, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

Grosz, Barbara J. & Candace L. Sidner. 1986. Attention, intentions, and the structure of discourse. Computational Linguistics 12(3). 175–204.Suche in Google Scholar

Golato, Andrea. 2010. Marking understanding versus receipting information in talk: Achso and ach in German interaction. Discourse Studies 12(2). 147–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445609356497.Suche in Google Scholar

Gunlogson, Christine. 2008. A question of commitment. Belgian Journal of Linguistics 22. 101–136. https://doi.org/10.1075/bjl.22.06gun.Suche in Google Scholar

Heim, Johannes M. 2019a. Turn-peripheral management of Common Ground: A study of Swabian gell. Journal of Pragmatics 141. 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.12.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Heim, Johannes. 2019b. Commitment and engagement: The role of intonation in deriving speech acts. PhD dissertation. Vancouver: UBC.Suche in Google Scholar

Heim, Johannes, Hermann Keupdjio, Zoe Wai-Man Lam, Adriana Osa-Gómez, Sonja Thoma & Martina Wiltschko. 2016. Intonation and particles as speech act modifiers: A syntactic analysis. Studies in Chinese Linguistics 37. 109–129. https://doi.org/10.1515/scl-2016-0005.Suche in Google Scholar

Heritage, John. 1984. A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (eds.), Structures of social action (Studies in conversation analysis), 299–345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511665868.020Suche in Google Scholar

Keupdjio, Hermann & Martina Wiltschko. 2018. Polar questions in Bamileke Medumba. Journal of West African Languages 45(2). 17–40.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenth, Russell. 2018. Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Malamud, Sofia A. & Tamina Stephenson. 2014. Three ways to avoid commitments: Declarative force modifiers in the conversational scoreboard. Journal of Semantics 32(2). 275–311. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffu002.Suche in Google Scholar

Osa Gomez del Campo, Adriana. 2020. Epistemic (mis)alignment in discourse: What Spanish discourse markers reveal. Vancouver: PhD dissertation UBC.Suche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. URL https://www.R-project.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Stalnaker, Robert. 1978. Assertion. In Peter Cole (ed.), Syntax and semantics, vol. 9: Pragmatics, 315–332. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.10.1163/9789004368873_013Suche in Google Scholar

Stalnaker, Robert. 2002. Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy 25(5). 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020867916902.10.1023/A:1020867916902Suche in Google Scholar

Stalnaker, Robert. 2014. Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199645169.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Wiltschko, Martina. 2014. The universal structure of categories: Toward a formal typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139833899.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiltschko, Martina. 2017. Ergative constellations in the structure of speech acts. In Jessica Coon, Diane Massam & Lisa deMena Travis (eds.), The Oxford companion to ergativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198739371.013.18.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiltschko, Martina. 2019. Now can be the end of the past or the beginning of the future. In Lisa Matthewson, Erin Guntley, Marianne Huijsmanns & Michael Rochemont (eds.), “Wa7 xweysás i nqwal’úttensa i ucwalmícwa: He loves the people’s languages” Essays in Honour of Henry Davis, 385–400. UBC Working Papers in Linguistics.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiltschko, Martina. 2021. The grammar of interactional language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108693707Suche in Google Scholar

Wiltschko, Martina & Johannes Heim. 2016. The syntax of confirmationals. In Günter Kaltenböck, Evelin. Keizer & Arne Lohrmann (eds.), Outside the clause: Form and function of extra-clausal constituents, 305–340. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.178.11wil.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiltschko, Martina & Johannes Heim. 2020. Grounding beliefs: Structured variation in Canadian discourse particles. In Blasius Achiri-Taboh (ed.), Exoticism in English tag questions: Strengthening arguments and caressing the social wheel, 37–82. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Wolf, Lavi. 2014. Degrees of assertion. Be’er Scheva: Ben Gurion University of the Negev dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Merlin & Martina Wiltschko. 2016. The confirmational marker ha in Northern Mandarin. Journal of Pragmatics 104. 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.09.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Zimmermann, Malte. 2011. Discourse particles. In Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger & Paul Portner (eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, vol. 33, 2011–2038. New York and Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Non-canonical questions from a comparative perspective: Introduction to the special collection

- A comparative corpus study on a case of non-canonical question

- Interpreting high negation in Negative Interrogatives: the role of the Other

- French questions alternating between a reason and a manner interpretation

- The pragmatics of surprise-disapproval questions: An empirical study

- Non-standard questions in English, German, and Japanese

- Timing of belief as a key to cross-linguistic variation in common ground management

- The prosody of French rhetorical questions

- Surprise questions in spoken French

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Non-canonical questions from a comparative perspective: Introduction to the special collection

- A comparative corpus study on a case of non-canonical question

- Interpreting high negation in Negative Interrogatives: the role of the Other

- French questions alternating between a reason and a manner interpretation

- The pragmatics of surprise-disapproval questions: An empirical study

- Non-standard questions in English, German, and Japanese

- Timing of belief as a key to cross-linguistic variation in common ground management

- The prosody of French rhetorical questions

- Surprise questions in spoken French