Abstract

Based on a large corpus of video and eye-tracking data and inspired by multimodal conversation analysis, this paper analyses how visitors discover natural phenomena during their use of hands-on exhibits in a science and technology centre (STC). In these discoveries, individual multisensorial experiences of natural phenomena are communicatively transferred from one visitor to another. This paper describes two contrasting sequential formats of joint discoveries in the STC. In the first and more frequent case, experiences are socially shared by focussing the co-visitors’ visual attention on one point in their interactional space, while in the second case perceptions are socially shared via reproduction sequences, i.e. by repeating the actions that have led to the discovery with exchanged roles. We will argue that in these reproduction sequences, sharing experiences can be understood via the concept of “intercorporeality” (Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2014 [1945]. Phenomenology of perception. London, New York: Routledge). Our paper contributes to the current debate on intercorporeality, as it empirically shows that it is analytically fruitful to extend the concept to situations without simultaneous perception.

1 Introduction

Science and technology centres (STCs) are a modern type of museum. They are often referred to as “interactive” (but see Heath et al. 2005), since they replace the classic museum displays by exhibits that can and must be manipulated by their visitors in order to bring about the respective phenomena. The STCs’ basic idea of transferring scientific knowledge is to enable visitors to construct new knowledge about natural phenomena by allowing them to experience those phenomena ‘with all their senses’. Thus, knowledge construction is imagined as intimately related to the embodied experience of the relevant phenomena, an approach to learning often labelled as “experiential” or “discovery learning” (Bruner 1961). In our video and eye-tracking corpus of visitor interactions in a large STC (see Section 3), discoveries are a pervasive element: Visitors continuously signal to each other that they have had some novel and exciting experience while engaging with the hands-on exhibits of the STC. Often, this marks the start or endpoint of a sequence of knowledge construction.

The aim of the present paper is to describe two contrasting formats of discoveries in the STC, which we have reconstructed based on our corpus, using the methods of multimodal conversation analysis. These two formats represent two contrasting solutions to the problem of how individual sensory experiences can be shared in interaction. In discovery format I, sharing an experience is achieved by directing one’s partner’s attention to the discovered phenomenon in the ‘common perceptual space’ (Hausendorf 2010). In discovery format II, on the contrary, the problem of sharing perceptions is solved by means of a reproduction sequence, i.e. by re-doing the actions that have led to the discovery, but with exchanged roles. We will argue that the concept of “intercorporeality” (Merleau-Ponty 2014 [1945]; see also Meyer et al. 2017) can give us insights into the way individual experiences are shared in this second discovery format.

After a short outline of previous research in Section 2, we briefly describe our data in Section 3. Sections 4 and 5 reconstruct the two contrasting formats, and discuss the question of how participants deploy them as two solutions to the problem of how to ‘share’ perceptions. In format II, the performance of the same bodily activities is the basis for the assumption of having identical perceptions (see Section 6).

2 Discoveries, noticings and intercorporeality

In this paper, we want to show that discoveries in the STC can be seen as a special kind of “noticings” (cf. also Kesselheim et al. 2021). Noticings have been defined by Schegloff (2007: 219) in a well-known quote as follows:

Doing a noticing makes relevant some feature(s) of the setting, including the prior talk, which may not have been previously taken as relevant. It works by mobilizing attention on the features which it formulates or registers, but it treats them as its source, while projecting the relevance of some further action in response to the act of noticing.

Now, discoveries in the STC are not just noticings that happen to occur in a science and technology centre. They are transformed into discoveries by the participants negotiating the discovery-relevance of a noticing, viz. by constructing the jointly noticed thing as novel and spectacular, and by actively tying the ongoing activity as well as the noticed thing itself to the context of science (see Sections 4 and 5).

In spite of being related to science, discoveries in the STC are not scientific discoveries either. Scientific discoveries have been repeatedly studied from an ethnomethodological perspective. The spectrum ranges from the famous paper by Garfinkel and colleagues on the discovery of the Crab pulsar, which led to the Nobel Prize being awarded to its discoverers (Garfinkel et al. 1981), to recent research on discoveries in the physics lab (e.g. Sormani 2011) or discoveries as part of processes of teaching and learning (Koschmann and Zemel 2009, 2011). In these studies, discoveries are represented as a lengthy process of problem solving, leading from a first “noticing” (or “reporting”) to a “discovery achieved” (Koschmann and Zemel 2009). By contrast, discoveries in the STC are often highly reduced, the whole discovery work sometimes being compressed into a short multimodal noticing.

Insofar as discoveries draw attention to something visible in the participants’ spatial environment, they are intimately linked to the interactive construction of “interactional space” (e.g., Mondada 2009): By ‘co-orienting’ their attention to some noticed feature in their surroundings, participants can be said to create a ‘common perceptual space’ (Hausendorf 2010). However, in the STC, the phenomena to be discovered are often kinaesthetic or proprioceptive in nature and include feelings of imbalance or dizziness, the bodily perception of small electric shocks, etc. The question is: How can the experience of these embodied phenomena be shared? Here, “intercorporeality” (Merleau-Ponty 2014 [1945]) moves into focus as a sort of “prereflexive”[1] alignment of the bodies in interaction, through which the interaction partners “co-perceive not only the situation at hand, but also the embodied experiences of one another and the surrounding world that they presently inhabit together” (Meyer et al. 2017: xxvii). The concept of intercorporeality is frequently exemplified with activities like shaking hands or dancing,[2] where the participant’s experience of the other’s body and the simultaneous experience of one’s own body are inextricably enmeshed. In this paper, we will show that participants draw from intercorporeality to share embodied experiences even in cases where they have to use the exhibit one after the other and the individual experiences they want to share originate from two temporally separated situations. The participants bridge this time gap by communicatively ‘blending’ or ‘compressing’ the two situations into one (Sweetser 2001) and, in doing so, allowing an assumption of the effectiveness of intercorporeality as a mechanism to share experiences.

3 Corpus

The empirical basis of this paper is a corpus of video and eye-tracking recordings of visitor interactions gathered at the Swiss Science Center Technorama (Winterthur) within a project entitled “Interactive Discoveries”. The recordings, which are between 20 and 30 min long, document stretches of self-guided visits of more than 100 couples or small groups of visitors.[3] The interaction was filmed using two hand-held video cameras. Additionally, in about half of the recordings binocular head-mounted eye-tracking glasses (Ergoneers and SMI) were used. The resulting data were transformed into synchronised split screen videos. These videos are the empirical basis of our reconstruction of the two formats of joint discoveries.

4 Joint discoveries in shared perceptual space

In this section, we describe the core elements of a discovery in the STC. We focus on the specific conversational tasks of the participants – i.e. their observable orientations – when they manifest a noticing (initiation), when they produce the projected reaction (acknowledgement), which transforms the noticeable into a jointly noticed thing, and when they activate the institution STC as the relevant context of understanding (contextualization).

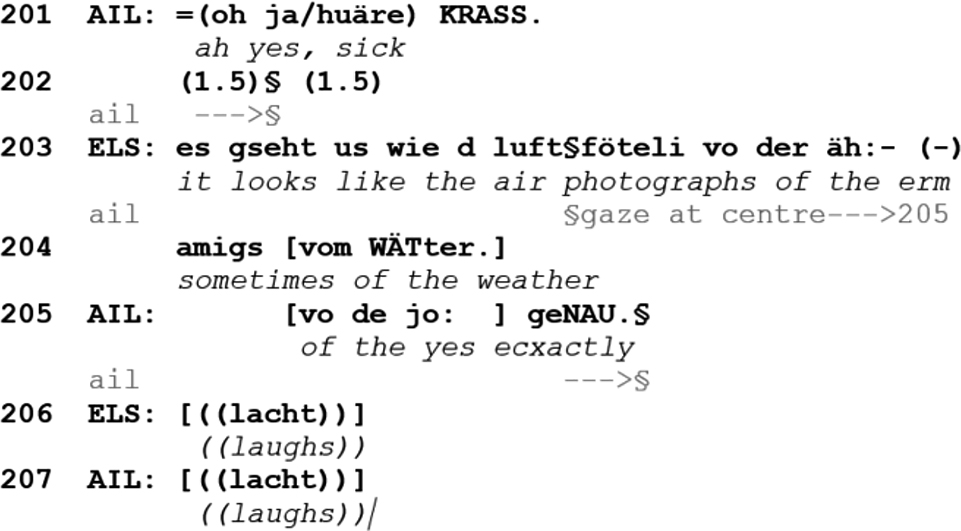

While the following extract (Extract 1) is a case of our discovery format I, the constitutive tasks that make up a discovery in the STC are essentially the same in format II (see Section 5). Aileen (AIL) and Elias (ELS) have just arrived at an exhibit named “Tornado”. They use a special torch to illuminate a ‘slice’ of a steam spiral, which winds upwards from the centre bottom of the exhibit (see video). The extract begins when Elias draws Aileen’s attention to the dark centre of the ‘slice’.

Extract 1: Tornado[4]

At the beginning of Extract 1, Elias sets the discovery sequence in motion. He recognizably produces an initiation of a noticing by addressing the following tasks (derived from the above quote by Schegloff, see Kesselheim et al. 2021:

formulating or registering some feature of the setting

making it/them relevant

projecting some response by the interaction partner, namely a (re-)orientation of attention to the noticeable.

Elias registers the centre of the slice by indicating its position with a presentational copula construction consisting of the deictic expression ‘here’ (“da”, with pointing gesture) and the local description ‘in the middle’ (“i de mitti”, l. 195), and he verbally categorizes the noticed thing as a ‘(kind of) tornado’ (l. 197). Elias marks the noticed thing as relevant by making a sudden step forward and by pointing to the centre of the ‘tornado’ from a short distance, which makes it necessary for him to bow his upper body into the frame of the exhibit. The action Elias is projecting is, indeed, that Aileen should also orient her attention to the identified noticeable: In stepping a little bit sidewards, Elias creates a sort of empty space in the centre of the exhibit frame, which invites Aileen to enter this space. Moreover, by executing his pointing gesture with the little finger, from sideways and with the arm held close to the body (Figure 1, enlarged section), Elias clearly orients towards not blocking Aileen’s view, thus transforming the empty space into a ‘space-for-observation’.

Elias projects Aileen’s reorientation to the noticeable by creating a ‘space-for-observation’.

Aileen recognizably produces an acknowledgement by orienting to each task of the initiation.[5] By bending over to the area that has been multimodally identified by Elias’, she bodily constructs the noticeable registered by her partner as something that requires a close look; and by uttering ‘yes’ (l. 198), she displays that she sees the noticeable the way Elias does: as a tornado. Aileen confirms the relevance of the noticeable: She helps Elias to highlight its novel character by means of the “change of state token” ‘ah’ (l. 198; cf. Heritage 1984)[6] and supports his referring to the small steam whirl in terms of a huge natural phenomenon. She even upgrades the relevance of the noticed thing (cf. Pomerantz 1984) with her interjection ‘sick!’ (“KRASS”, l. 201). Finally, Aileen produces the response projected by her partner: She visibly directs her attention to the noticed feature, by stepping closer and bowing forward towards the noticeable in the middle of the hands-on exhibit (l. 197/198, Figure 2) – her persistent gaze on the noticed thing being observable in our eye-tracking data.

Aileen fills in the multimodally identified ‘space-for-observation’.

Together, Aileen and Elias contextualise their noticing as part of their joint activity in the institution setting of the STC. By referring to the thin thread of steam as ‘a tornado’, they reproduce a basic semiotic principle of the museum, namely that the exhibits represent something outside the exhibition space, here: a powerful natural phenomenon.[7] Furthermore, they activate the context of nature and science by comparing the ‘tornado’ to the ‘aerial photographs’ of weather phenomena (l. 203–204.). These “contextualizations” (Gumperz 1992) together activate a specific background of understanding (nature, science, and the STC as an institution of science communication) and give Aileen’s and Elias’ noticing a specific meaning: They make it recognizable as a discovery in the institution STC.

In the joint discovery process, Aileen has explicitly “affiliated” (Stivers 2008) with Elias’ stance towards the noticeable. Insofar as “access” to the relevant information is a precondition of affiliation (as Stivers has pointed out), Aileen can be seen to implicitly claim access to Elias’ visual perception – and this claim is not challenged by Elias. In other words, in this discovery sequence the two visitors display that for them Elias’ visual experience has been successfully shared.

5 Joint discoveries in a non-shared perceptual space

In our corpus, the vast majority of the discovery sequences follows the pattern described so far. However, there are some cases where the visitors clearly orient to the communicative tasks of a discovery, but where there is no joint bodily alignment towards a particular point in space, which is a characteristic element of our discovery format I. Extract 2 is an example.

Two young men, Cedric (CED) and Jayden (JAY), have just read the instruction text of an exhibit consisting of a moveable board with a regular pattern of vertical stripes. As the text explains, one visitor is supposed to stand one-legged in front of the board while the other swings the board to the right and left (with the unstated result that the moving environment causes a strong feeling of imbalance in the first visitor). Cedric, who has taken the position in front of the board, prompts his friend to ‘do it’.

Extract 2: Stripes I

In Extract 2, Jayden and Cedric bring about a discovery. Cedric initiates the discovery with a vocalization plus the interjection “fuck!” (l. 209), without any indication of what the features are, he tries to register. This indication rather comes from his spreading his arms and moving them erratically around. At the same time, these arm movements amplify the small balancing movements of his upper body, and thus make his experience of imbalance more relevant (cf. also his loud laughter). Since Cedric’s bodily activity does not contain any vector pointing to a place in the spatial environment, the movements project a (re-)orientation of attention towards Cedric himself, instead. And in fact, in the following acknowledgement, Jayden’s gaze stays oriented towards Cedric’s experiencing body, more exactly to his hand and his face,[8] instead of immediately shifting to the moveable board where Cedric’s experience takes its visible origin. At the same time, Jayden affiliates (Stivers 2008) with the way Cedric has framed the relevance of his experience, by producing a positive reaction with a ‘smiling voice’ (l. 210).[9]

Instead of the visual (re-)orientation to the noticed feature in the spatial environment, in this second discovery format we find a shift of attention to the experiencing participant. However, this shift of attention seems not to be enough for the participants to assume that they have successfully shared an experience here: The (re-)orientation is not the endpoint of this type of discoveries. What typically follows, instead, is what we term a reproduction sequence. In this kind of sequence, the acknowledging participant repeats the actions that led his partner to experience the noticed thing. Extract 3, the direct continuation of Extract 2, is an example of such a reproduction sequence.

Extract 3: Stripes II

In this sequence, the exact repetition of Cedric’s previous actions is a clear orientation. Cedric prompts his friend to try out the exhibit (‘come on, do it!’, l. 212). He ‘overlays’ Jayden’s current usage of the exhibit with an exhilarated account of his own intentions and thoughts during his first-time usage of the exhibit. Thereby, he ‘blends’ Jayden’s current experience with his own previous one, formulating his utterance in such a way that it can also be understood as a kind of ‘live comment’ on his friend’s current feelings with the help of the second person pronoun ‘you’ (see Section 6). Furthermore, while the experiment allows for a broad range of positions and postures, the two friends take almost exactly the same positions, the current exhibit user standing far left, very close to the frame, holding up one leg (Figures 3 and 4).

![Figure 3:

Cedric’s position when he prepares to try out the exhibit, just before he loses balance (l. 208, CED: MACH ma, [#3]).](/document/doi/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0101/asset/graphic/j_lingvan-2020-0101_fig_003.jpg)

Cedric’s position when he prepares to try out the exhibit, just before he loses balance (l. 208, CED: MACH ma, [#3]).

![Figure 4:

Reproduction sequence in the moment of line 215: CED: du denks_so du: (.) du hättsch die baLANce [#4].](/document/doi/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0101/asset/graphic/j_lingvan-2020-0101_fig_004.jpg)

Reproduction sequence in the moment of line 215: CED: du denks_so du: (.) du hättsch die baLANce [#4].

Both discovery formats share the same basic structure: an initiation (registering an individual sensory perception, projecting a response by the partner), an acknowledgement (transforming the noticeable into a jointly noticed, bringing about its novel and spectacular character) and a contextualisation (linking the activity to the institutional context). However, while in format I the initiation leads to a reorientation of attention towards the experienced phenomenon in the ‘shared perceptual space’ (Hausendorf 2010), in format II the reorientation is directed towards the experiencing subject, instead. And while the reorientation towards the experienced phenomenon is sufficient for the participants to assume that they have successfully shared the relevant experience, the same does not hold for the reorientation towards the experiencing subject. In format II, sharing the relevant experience is clearly the job of the reproduction sequence.[10]

5.1 Intercorporeality in reproduction sequences

In the following, we want to argue that the concept of intercorporeality can help us to better understand how embodied experiences are shared in the reproduction sequences. In order to do so, we will show first that the participants indeed display an increase in co-perception during the reproduction sequences. Then we will reconstruct how they define their situation in a way that makes the assumption plausible that intercorporeality is at work here and allows them to share their embodied experiences.

We want to start with a series of observations that can be seen as indications that in the reproduction sequence the participants display a greater degree of co-perception than in the discovery sequence (Extract 2).

Cedric displays a deeper engagement in Jayden’s repeating the process of discovery than when he himself made the discovery, experiencing the imbalance for the first time. Cedric’s laughter is more intensive than in the discovery sequence, showing an increased level of participation during the observation of the experiencing participant (see Extract 2, l. 209, and Extract 3, l. 212).

Our eye-tracking data show: While Jayden only gazed at Cedric’s hands when they started to move in the discovery sequence (Extract 2, l. 208), Cedric stays focused on Jayden, monitoring those body parts where the signs of imbalance will become manifest, even before Jayden starts to show imbalance (Extract 3, l. 215–219). In other words: Cedric is able to anticipate where the experience of imbalance will find its visible expression in his friend. This kind of anticipation has been described as a result of co-perception in the literature on intercorporeality (Meyer et al. 2017: xxiii).

When Jayden is already shaking, but still holds his balance, Cedric pushes the board harder, thereby increasing his friend’s struggle with balance. This is a way of actively shaping the other’s activity, a “feed-forward mechanism” that has been described as an effect of co-perception (Fuchs and De Jaegher 2009, 466).

Finally, Jayden explicitly formulates his embodied reproduction of Cedric’s discovery as the ‘missing link’ to fully understanding his partner’s embodied expression of his experience during the ‘first discovery’. At the very moment his body starts shaking a little, he comments: ‘oh (I can now can I) understand what’s going on’ (Extract 3, l. 216).

This last observation is especially interesting, since several authors within the phenomenological cognitive sciences suggest that already when we observe our interaction partner experiencing something, the visible manifestations of his or her “proprio- and interoceptive bodily feelings” create “corresponding or complementary bodily feelings” in us (Froese and Fuchs 2012: 212). Here, Jayden displays that the observation was not sufficient for him to fully grasp the experience manifested by Cedric’s reactions (being the first time he has used this exhibit), and that only the sensorimotor experience led him to a “[f]ully fleshed out form[ ] of intercorporeal reciprocity” (Meyer et al. 2017: xxvi), allowing him the assumption to understand the phenomenon in the way his partner understood it.

Now, can we say that this display of an enhanced co-perception indicates that in the reproduction sequences sharing experience is based on the mechanism of intercorporeality? As has been mentioned before, the reproduction sequences differ considerably from the prototypical examples typically discussed in the literature on intercorporeality. From the perspective of intercorporeality, sharing experiences is based in concrete situations of co-perception, i.e. moments where the interaction partners perceive their bodies as being at the same time the subject and object of a joint activity: shaking hands, kissing, jointly steering a canoe, etc. In reproduction sequences above, however, the relevant embodied experiences are made by the two participants one after the other.

In the rest of this paper, we want to argue that the concrete design of the reproduction sequences can be understood as a systematic solution to the problem of basing the mutual understanding of embodied experiences on intercorporeality in situations where the participants cannot experience the relevant phenomena simultaneously. The participants’ strategy consists in bringing their situation closer to the prototypical situation of intercorporeality by

carefully reproducing the activities that led the ‘first experiencer’ to his or her experience during the discovery sequence, enhancing the “sensorimotor inclusion profile” (Loenhoff 2017: 39) and

by actively conflating the experiences of the discovery sequence and those of the reproduction sequence into a common experience resulting from an activity constructed as being one joint activity.

How can this strategy be observed in Extract 3?

Enhancing the sensorimotor inclusion profile: There is a conspicuous orientation of the ‘second experiencer’ towards the most exact possible reproduction of the actions of the ‘first experiencer’. In Extract 3, Cedric and Jayden exactly adopt the position of their respective partner during the discovery sequence (compare Figures 3 and 4, above). The idea seems to be to make the own sensorimotor and visual experiences in the reproduction sequence resemble as closely as possible the experiences of the respective partner during the discovery, because these embodied experiences are the basis which allows the participants to understand their partner in a preconceptual, “carnal” way (Meyer et al. 2017: xix). In this process, the role change enhances the “sensorimotor inclusion profile” (Loenhoff 2017: 39) of the situation: In fact, the role reversal adds another layer of perceptions made with other senses to the experience made so far (cf. the concept of “crossmodal perceptual enhancement”, Klemen and Chambers 2012: 122). In Cedric’s case, the interoceptive experience of imbalance and the compensating movements of upper body and arms (during his own discovery) are now complemented with the visual experience of seeing someone losing his balance (in the reproduction sequence). Jayden, on the other hand, perceives what the imbalance feels like within his body and can ‘bodily understand’ the movements Cedric made before as movements to regain balance.

Actively conflating the two situations/experiences into one: In Extract 3, we can observe that the two visitors make some effort to construct their temporally separated experience of the imbalance as jointly experiencing the same phenomenon – i.e. they construct it as a situation of co-perception.[11] This is done by the following means:

When Jayden reproduces the manipulation sequence in front of the board, Cedric overlays Jayden’s actual experience with the description of his own former experience of the phenomenon (see above). He finely aligns the production of his utterance to Jayden’s activities of reproducing the relevant experience in lines 214 and 215 by lengthening of vowels (“du:”) and a micropause. By doing so, the accented syllable “baLANce” (i.e. the climax of his formulation of his expectation before it is proven wrong by the discovery sequence) is produced at the very moment Jayden lifts his foot and starts experiencing the effect of the moving board.

Furthermore, by using the second person singular, Cedric does not specify whether he is talking about his own past experience (‘you’ as an impersonal pronoun, cf. Auer and Stukenbrock 2018) or whether he is doing a kind of live comment on Jayden’s current experiences (‘you’ as referring to Jayden). In doing so, he intensifies the entanglement between the two individual experiences, blending them into a common one.[12]

By conscientiously ‘copying’ their respective spatial positions, by verbally overlaying the first and second experience and by using the second person singular when describing (presumably) one’s own experience, the two participants actively construct their repeated exhibit use as one situation of co-perception.

All these observations suggest that the participants design the reproduction sequences in a way that maximally facilitates the assumption that intercorporeality is effectively at work although the experience of imbalance is made in two successive steps and the participants cannot directly experience the effect of the other’s activities in their own body. This is done by approximating their experiential situation to the prototypical (simultaneous) situations of intercorporeality, namely by “compressing” two experiential situations into a single one and by creating a maximal reciprocity of perspectives between subject/object of observation and subject/object of experience.

6 Conclusion

In the present paper, we have reconstructed and contrasted two sequential formats of joint discoveries in the science and technology centre. While the most characteristic element of format I is a swift (re-)orientation towards the discovered phenomenon, format II lacks this element: If there is a bodily reorientation at all, it is directed towards the participant who has initiated the discovery. The constitutive element rather is the “reproduction sequence”, where the visitors re-stage the discovery with exchanged roles. These two formats give us interesting insights into the participants’ diverging assumptions about the accessibility and shareability of individual sensory perceptions. In format I, the participants construct the phenomenon as being located within their common perceptual space. They share the individual experience by co-ordinating their gazes on the noticed thing. The underlying assumption is: “If we both look at the same point in our common perceptual space, we have the same visual experience.” This assumption is likely to generally apply to experiences accessible in a shared perceptual space. In format II there are no pointing gestures, there is no bowing forward etc. that would construct the noticed thing as an element of the common perceptual space. What we can observe in the reproduction sequences are attempts at communicatively transforming the two subsequent situations of individual experiences into one. The participants communicatively blur the boundaries between the two situations. They construct their activities in one situation as directly influencing the second one (cf. the analysis of the cognitive mechanisms of “compression” in Sweetser 2001). In doing so, they warrant experiencing the phenomenon once as the manipulating subject (actively influencing the experiencer’s environment, inducing the feeling of imbalance and seeing the other’s reactions) and once as the object of manipulation (experiencing the imbalance in an embodied manner). As we have argued in this article, the basic assumption seems to be: “If we construct our experiential situation as coming close to prototypical situations of co-perception, where we are at the same time subject and object of our joint activity, we can rely on intercorporeality as a basis for sharing our individual experiences.”[13]

Beyond the interest in knowledge construction in the science centre, our analysis of the reproduction sequences exemplarily shows how interactive displays of intercorporeality can be observed and empirically examined in concrete situations of embodied knowledge construction. It gives new insights into the tacit assumptions underlying the communicative sharing of individual experiences (i.e. the role of the interactively constructed common perceptual space and intercorporeality). Finally, it reveals that participants not only monitor the situational preconditions for sharing experiences (e.g. whether a phenomenon has been constructed as element of the common perceptual space), but also actively manipulate the situational preconditions for sharing experiences, e.g. when they actively make the effectiveness of intercorporeality plausible in situations which considerably differ from joint activities with mutual touch.

Funding source: Swiss National Fund for Science

Award Identifier / Grant number: 162848

-

Research funding: This research is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, project no. 162848, and is located within the URPP Language and Space, University of Zurich.

References

Auer, Peter & Anja Stukenbrock. 2018. When ‘You’ means ‘I’: The German 2nd Ps. Sg. pronoun Du between genericity and subjectivity. Open Linguistics 4(1). 280–309.10.1515/opli-2018-0015Suche in Google Scholar

Brandenberger, Christina. Forthcoming. Soziale Herstellung gemeinsamer multisensorialer Wahrnehmung im Science Center.Suche in Google Scholar

Bruner, Jerome S. 1961. The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review 31(1). 21–32.10.4324/9780203088609-13Suche in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver 2021. Multimodal practices for instructing body knowledge. Linguistics Vanguard 7(s4). 20200038.10.1515/lingvan-2020-0038Suche in Google Scholar

Froese, Tom & Thomas Fuchs. 2012. The extended body: A case study in the neurophenomenology of social interaction. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 11(2). 205–235.10.1007/s11097-012-9254-2Suche in Google Scholar

Fuchs, Thomas & Hanne De Jaegher. 2009. Enactive intersubjectivity: Participatory sense-making and mutual incorporation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 8(4). 465–486.10.1007/s11097-009-9136-4Suche in Google Scholar

Garfinkel, Harold, Michael Lynch & Eric Livingston. 1981. The work of a discovering science construed with materials from the optically discovered pulsar. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 11(2). 131–158.10.1177/004839318101100202Suche in Google Scholar

Gumperz, John J. 1992. Contextualization revisited. In Alessandro Duranti & Charles Goodwin (eds.), Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon (Studies in the social and cultural foundations of language 11), 39–53. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1075/pbns.22.04gumSuche in Google Scholar

Hausendorf, Heiko. 2010. Interaktion im Raum: Interaktionstheoretische Bemerkungen zu einem vernachlässigten Aspekt von Anwesenheit. In Arnulf Deppermann & Angelika Linke (eds.), Sprache intermedial: Stimme und Schrift, Bild und Ton. Jahrbuch 2009 des Instituts für deutsche Sprache (Jahrbuch des Instituts für deutsche Sprache 2009), 163–197. Berlin: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110223613.163Suche in Google Scholar

Heath, Christian, Dirk Vom Lehn & Jonathan Osborne. 2005. Interaction and Interactives. Public Understanding of Science 14(1). 91–101.10.1177/0963662505047343Suche in Google Scholar

Heritage, John. 1984. A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis, 299–345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511665868.020Suche in Google Scholar

Kesselheim, Wolfgang, Christina Brandenberger & Christoph Hottiger. 2021. How to notice a tsunami in a water tank: Joint discoveries in a science center. Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 22. 87–113.Suche in Google Scholar

Keevallik, Leelo. 2021. Vocalizations in dance classes. Linguistics Vanguard 7(s4). 20200098.10.1515/lingvan-2020-0098Suche in Google Scholar

Klemen, Jane & Christopher D. Chambers. 2012. Current perspectives and methods in studying neural mechanisms of multisensory interactions. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 36(1). 111–133.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.015Suche in Google Scholar

Koschmann, Timothy & Alan Zemel. 2009. Optical pulsars and black arrows: Discoveries as occasioned productions. Journal of the Learning Sciences 18(2). 200–246.10.1080/10508400902797966Suche in Google Scholar

Koschmann, Timothy & Alan Zemel. 2011. “So that’s the ureter”: The informal logic of discovering work. Ethnographic Studies. 31–46.Suche in Google Scholar

Loenhoff, Jens. 2017. Intercorporeality as a foundational dimension of human communication. In Christian Meyer, Jürgen Streeck & J. Scott Jordan (eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction, 25–49. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190210465.003.0002Suche in Google Scholar

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2014 [1945]. Phenomenology of perception. London, New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Meyer, Christian, Jürgen Streeck & J. Scott Jordan. 2017. Introduction. In Christian Meyer, Jürgen Streeck & J. Scott Jordan (eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction, xv–xlix. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190210465.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Mondada, Lorenza. 2009. Emergent focused interactions in public places: A systematic analysis of the multimodal achievement of a common interactional space: Communicating place, space and mobility. Journal of Pragmatics 41. 1977–1999.10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.019Suche in Google Scholar

Mondada, Lorenza. 2016. Conventions for multimodal transcription. https://franzoesistik.philhist.unibas.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/franzoesistik/mondada_multimodal_conventions.pdf (accessed 9 November 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Pomerantz, Anita. 1984. Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred and dispreferred turn shapes. In Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis, 57–101. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1093/oso/9780190927431.003.0002Suche in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (ed.). 2007. Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511791208Suche in Google Scholar

Sormani, Philippe. 2011. The jubilatory YES! On the instant appraisal of an experimental finding. Ethnographic Studies 12. 59–77.Suche in Google Scholar

Stivers, Tanya. 2008. Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction 41(1). 31–57.10.1080/08351810701691123Suche in Google Scholar

Stukenbrock, Anja. 2017. Intercorporeal phantasms: Kinaesthetic alignment with imagined bodies in self-defense training. In Christian Meyer, Jürgen Streeck & J. Scott Jordan (eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction, 237–263. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190210465.003.0009Suche in Google Scholar

Sweetser, Eve. 2001. Blended spaces and performativity. Cognitive Linguistics 11(3–4). 305–333.10.1515/cogl.2001.018Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0101).

© 2021 Wolfgang Kesselheim and Christina Brandenberger, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Instructing embodied knowledge: multimodal approaches to interactive practices for knowledge constitution

- Singing and the body: body-focused and concept-focused vocal instruction

- In other gestures: Multimodal iteration in cello master classes

- Vocalizations in dance classes teach body knowledge

- Synchronization in demonstrations. Multimodal practices for instructing body knowledge

- Situating embodied action plans: pre-enacting and planning actions within knowledge communication in sports training

- Taking the trumpet up there: enactment of embodied high pitch in a multimodal body schema

- Monitoring and evaluating body knowledge: metaphors and metonymies of body position in children’s music instrument instruction

- Situating embodied instruction – proxemics and body knowledge

- The social construction of embodied experiences: two types of discoveries in the science centre

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Instructing embodied knowledge: multimodal approaches to interactive practices for knowledge constitution

- Singing and the body: body-focused and concept-focused vocal instruction

- In other gestures: Multimodal iteration in cello master classes

- Vocalizations in dance classes teach body knowledge

- Synchronization in demonstrations. Multimodal practices for instructing body knowledge

- Situating embodied action plans: pre-enacting and planning actions within knowledge communication in sports training

- Taking the trumpet up there: enactment of embodied high pitch in a multimodal body schema

- Monitoring and evaluating body knowledge: metaphors and metonymies of body position in children’s music instrument instruction

- Situating embodied instruction – proxemics and body knowledge

- The social construction of embodied experiences: two types of discoveries in the science centre