Abstract

Objectives

Clinical laboratories invest substantial time and resources to mitigate measurement error but potential errors during the preanalytical phase of testing are not subjected to the same level of scrutiny. Herein, we assess the proportions of intravenous (IV) fluid contamination sufficient to exceed common performance metrics and compare it to contaminated results flagged by current protocols.

Methods

Basic metabolic panels performed between 01/2017 and 07/2022 were extracted from the laboratory information system (n=928,742). Contamination was simulated for common IV fluid types. The thresholds at which contaminated results exceeded total allowable error (TEa), reference change values (RCV), or changed normality/critical flags were calculated. The mixture ratio of IV fluid contamination detected by technologists during routine analysis was estimated.

Results

The TEa and RCV was exceeded at a mixture ratio ≤0.10 for chloride, glucose, calcium, and potassium for both normal saline (NS) and 5 % dextrose in water (D5W). At a simulated mixture ratio of 0.10, 51.39 % of calcium and 21.17 % of potassium results would be expected to be incorrectly reported with an abnormal/critical flag with NS contamination and 99.74 % of sodium and 100 % of glucose results to be incorrectly flagged with D5W. Retrospective results flagged as contaminated revealed a median mixture ratio of 0.18 and 0.24 for D5 and non-D5 fluids.

Conclusions

At a mixture ratio of at least 0.10, IV fluid contamination causes relevant error between patients’ true concentrations and those reported. However, current procedures cannot reliably detect 10 % contamination.

Introduction

Laboratory errors contribute to a cascade of downstream consequences affecting patient care [1] including delays in diagnosis, incorrect treatment, and increased healthcare costs, among others [2], [3], [4]. One common cause of error is contamination of specimens by intravenous (IV) fluids that were infused through the same line from which the specimen was drawn [5], [6], [7], [8]. Currently, there is no consensus method for detecting contamination of specimens by IV fluids and many laboratories use human judgment and univariate delta checks [9]; a quality control-based system that assesses the feasibility between a patient’s current result relative to a previous result. Importantly, these methods lack sensitivity for detecting gross contamination (>10 %) of specimens by IV fluids [10], [11], [12], [13].

Recent studies aimed at improving detection of contaminated specimens have used more advanced methods such as statistically guided protocols that assess the feasibility of multiple analytes [14] and incorporating multi-analyte delta checks derived from simulation experiments [12] which can identify ∼10 % contamination with IV fluids. Thus, while modern approaches have improved the sensitivity for detection of IV fluid contamination, it is not clear to what degree contamination severity impacts a sample analytically or clinically. Studies published to date have used a heuristic approach to define criteria that will best identify relevant IV fluid contamination (i.e. 10 % contamination).

Extensive efforts have been made to define, standardize, and harmonize the assessment of analytical quality [15, 16]. These efforts have brought about valuable metrics such as total allowable error (TEa) [17, 18], and the reference change value (RCV) [19], [20], [21]. TEa captures the acceptable extent to which serial measurements on the same specimen can differ, while the RCV approximates the threshold at which two serial measurements of an analyte from a single patient represents a significant difference that cannot be explained by analytical factors and biologic variability. These metrics contribute to an overall error budget which are often applied only to the analytical phase, but are potentially helpful targets for laboratories to ensure quality during all phases of testing [22]. To our knowledge, no study to date has assessed the impact of IV fluid contamination on BMP results through the lens of TEa or RCV. Moreover, while the concepts of TEa and RCV are well-known to laboratorians, clinical providers are often less familiar with these concepts [23]. However, the application of reference intervals to provide abnormal or critical flags is universal. Nonetheless, the clinical impact of IV fluid contamination on abnormal/critical flags has not been explored.

Herein, we objectively assess the thresholds at which contamination introduces “relevant” laboratory error – using total allowable error (TEa), reference change values (RCV), and the impact on abnormal or critical flags. We then assess the distribution of severity in contaminated specimens that are detected by our current workflow.

Materials and methods

Data aggregation and processing

This study was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB #202202030). All BMP results performed at Barnes-Jewish Hospital between January 1, 2017, and July 1, 2022, were extracted from the laboratory information system (Cerner, Kansas City, USA). Only BMPs for which all eight components were reported into the medical record were included (n=928,742).

Results reported as above or below a threshold value were replaced with that threshold (e.g. a sodium reported as ‘>180 mEq/L’ was replaced with 180 mEq/L). Anion gap was calculated as the sodium concentration minus the sum of chloride and total carbon dioxide concentrations. Only results reported and verified in the clinician-facing electronic medical record (EMR) that may have guided medical decision-making were included in the analysis.

Simulating IV fluid contamination

Motivated by the results of wet-bench mixing experiments [5, 6, 10], IV fluid contamination was simulated as a mixture between the results of real patient samples and the concentrations in common IV fluids. Mixture ratios ranged from 0 to 1, incrementing by 0.01 – where a ratio of 0.50 indicates equal parts patient sample and IV fluid. Supplementary Figure 1 presents a schematic overview of the approach. Simulated errors were validated with an in vitro mixing study with a subset of the fluids described, and specimens were analyzed on a Roche cobas 8,000 chemistry analyzer consistent with previously published studies [10]. Contamination by each of the ten most common IV fluid solutions was simulated, the compositions of which are described in Supplementary Figure 2.

Assessing the analytical impact of contamination via TEa and RCV

TEa thresholds were adopted from the CLIA ‘88 requirements for analytical quality [24]. For analytes without CLIA-defined, absolute TEa thresholds (chloride and CO2), the absolute thresholds from the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (RCPA) [25] were used. Reference change values (RCV) were calculated using the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Biological Variation Database [26], which applies the asymmetric approach [27]. As such, contamination that caused an increase in the analyte-of-interest was compared to the appropriate RCVIncrease, while those that caused a decrease were compared with the RCVDecrease. The mean of the high and low-level analytical coefficients of variation (CV) from our hospital laboratory’s most recent 30 days of quality control analysis were used as the CVa for the calculation. Median RCV value calculations were used for the final analysis. The TEa and RCV thresholds used for comparison are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Each of these thresholds were applied to the simulated contamination set, and the mixture ratios at which a majority of contaminated specimens exceeded these thresholds were calculated to mirror the approach used when defining a qualitative cut-off from quantitative measurement data.

Assessing impact on reference intervals and critical flags

To assess the clinical impact of contamination, we applied the abnormal and critical thresholds for each analyte to the simulated contamination set and calculated the proportion of results that would be incorrectly flagged at each mixture ratio. Supplementary Table 2 demonstrates the list of high and low abnormal thresholds and critical values used.

Comparison to the current approach

The procedure used to assess for the presence of contamination of specimens include feasibility flags, delta checks, and manual technologist review. A list of delta check rules and feasibility flags can be found in Supplementary Table 2. Interpretation of potential contamination was at the discretion of each technologist using routine clinical workflows. When a potentially contaminated specimen was identified, the technologists contact the clinical provider and indicate a concern for contamination. If the provider agreed that contamination was the most likely explanation, the results were suppressed and an interpretive comment applied. The absence of the interpretive comment for contamination was used as an objective assessment that a reported result was not identified as contaminated by the current procedure.

Retrospectively flagged results were stratified into those containing and not containing 5 % dextrose using a glucose measurement of 300 mg/dL as a cut-off. The mixture ratio for dextrose contamination was approximated as the increase in glucose divided by 5,000. For example, a glucose result that increased from 100 mg/dL to 600 mg/dL would be assigned a mixture ratio of 0.10 ([600 − 100]/5,000). Non-dextrose contamination was approximated using the decrease in calcium such that a decrease from 9.0 mg/dL to 8.1 mg/dL would be assigned a mixture ratio of 0.10.

Performing the analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.2.3 using the {tidyverse} [28] and {targets} [29] frameworks. All code written to perform these analyses is available publicly on GitHub at https://github.com/nspies13/contamination_simulation with the anonymized input data available on FigShare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23805456.v1 [30].

Results

Defining analytically relevant contamination thresholds

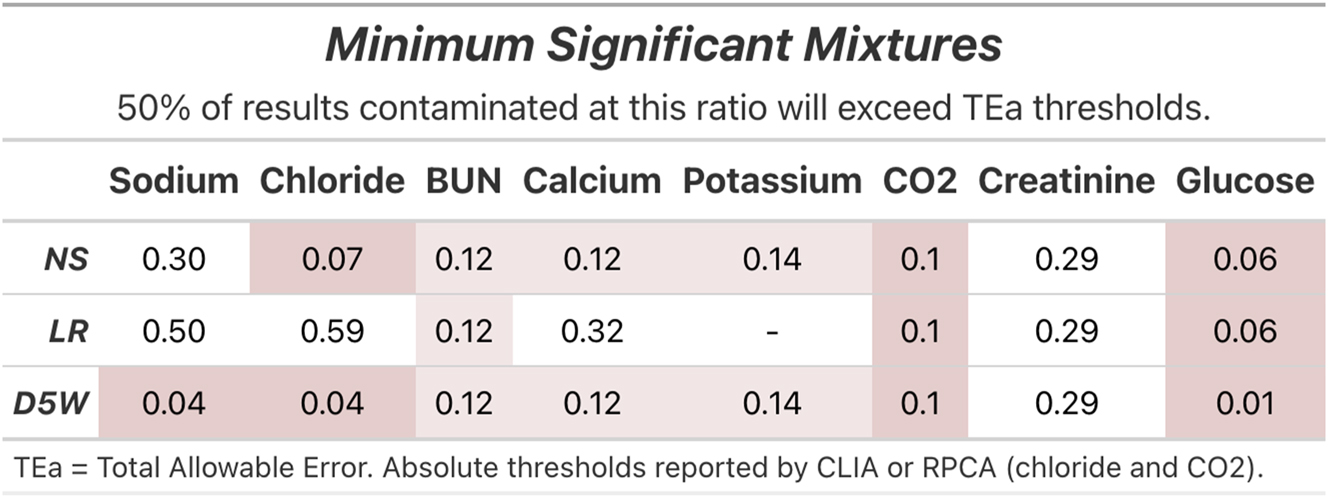

Figure 1 summarizes the ratios at which half of the simulated mixtures exceeded TEa for each analyte measured on the BMP for three common fluids; 0.9 % normal saline (NS), lactated Ringer’s (LR), and 5 % dextrose in water (D5W). Supplementary Figure 3 demonstrates the same data for D5NS, D5LR, D5 in 0.45 % NS with and without potassium chloride, 3 % normal saline, and water. A mixture ratio of 0.01 was sufficient to exceed the TEa of 6 mg/dL for glucose in IV fluids containing D5, while mixtures at 0.06 exceeded TEa for non-D5 containing IV fluids. Total CO2 was also markedly sensitive to contamination across all fluids, with a majority of contaminated results exceeding the absolute threshold of 2 mmol/L defined by the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (RPCA) at a mixture ratio of 0.10 for all IV fluids. Chloride, BUN, calcium and potassium exceeded TEa thresholds in a majority of specimens contaminated by NS at ratios of 0.07, 0.12, 0.12, and 0.14, respectively. However, higher mixture ratios were required for a majority of specimens to exceed TEa for LR solutions. Sodium was the analyte least susceptible to saline contamination, though mixtures of 0.04 and 0.08 were sufficient to exceed the TEa of 4 mmol/L for IV fluids that contain water and 0.45 % sodium chloride solutions (Supplementary Figure 3).

The mixture ratios at which half of the simulated contamination results exceeded the quality metric thresholds for total allowable error (TEa). Red and pink highlight fluid-analyte combinations for which a majority of results exceed TEa at mixture ratios of less than 0.1 and 0.25, respectively.

Incorporating intra-individual variation via the reference change value

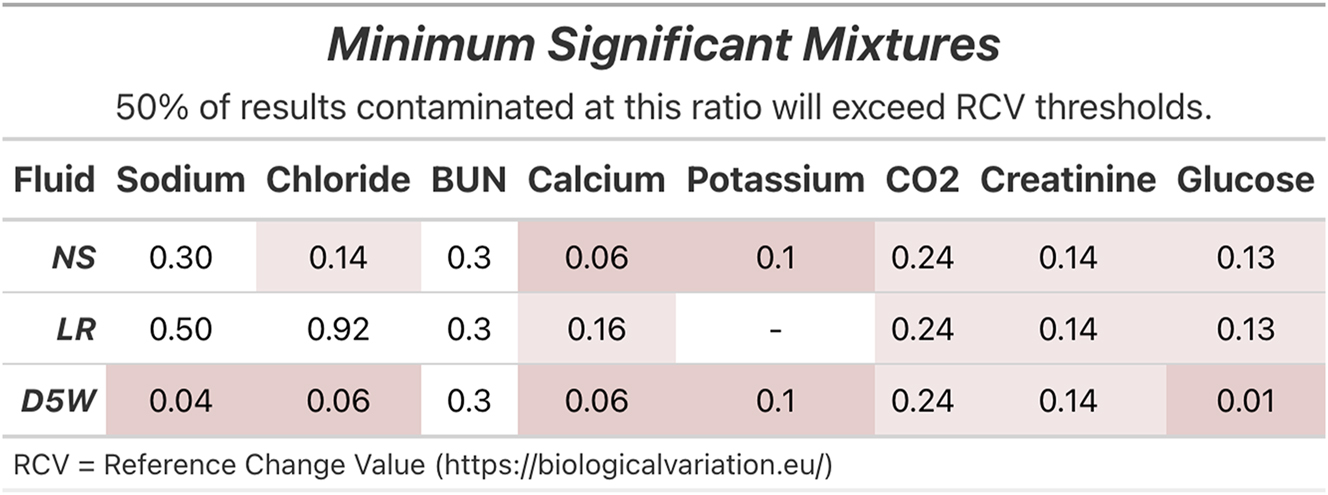

Figure 2 displays the mixture ratio from simulated contamination at which the difference between contaminated results and the accompanying non-contaminated result would exceed the RCV in 50 % of cases. More fluid types are displayed in Supplementary Figure 4. D5 at mixture ratios of 0.01 caused a majority of results to exceed the RCVIncrease of 15 % for glucose. Calcium and potassium also demonstrated relatively low mixture ratios at which relevant RCV thresholds were exceeded, requiring a ratio of 0.06 and 0.10 for NS contamination. A majority of LR-contaminated results exceeded the RCVDecrease of 6 % for calcium at a mixture ratio of 0.16. In contrast to TEa, creatinine results were more sensitive to the RCVDecrease of 13 %, requiring a mixture ratio of 0.14 for a majority to exceed the threshold across all fluids, while CO2 and BUN were less sensitive to the RCVDecrease threshold than to TEa, requiring a mixture of 0.24 and 0.30, respectively, across all fluids.

The mixture ratios at which half of the simulated contamination results exceeded the relevant reference change value (RCV) by increase or decrease relative to the ground truth result. Red and pink highlight fluid-analyte combinations for which a majority of results exceeded RCV at mixture ratios of less than 0.1 and 0.25, respectively.

Defining clinically relevant thresholds through incorrect normality and critical flags

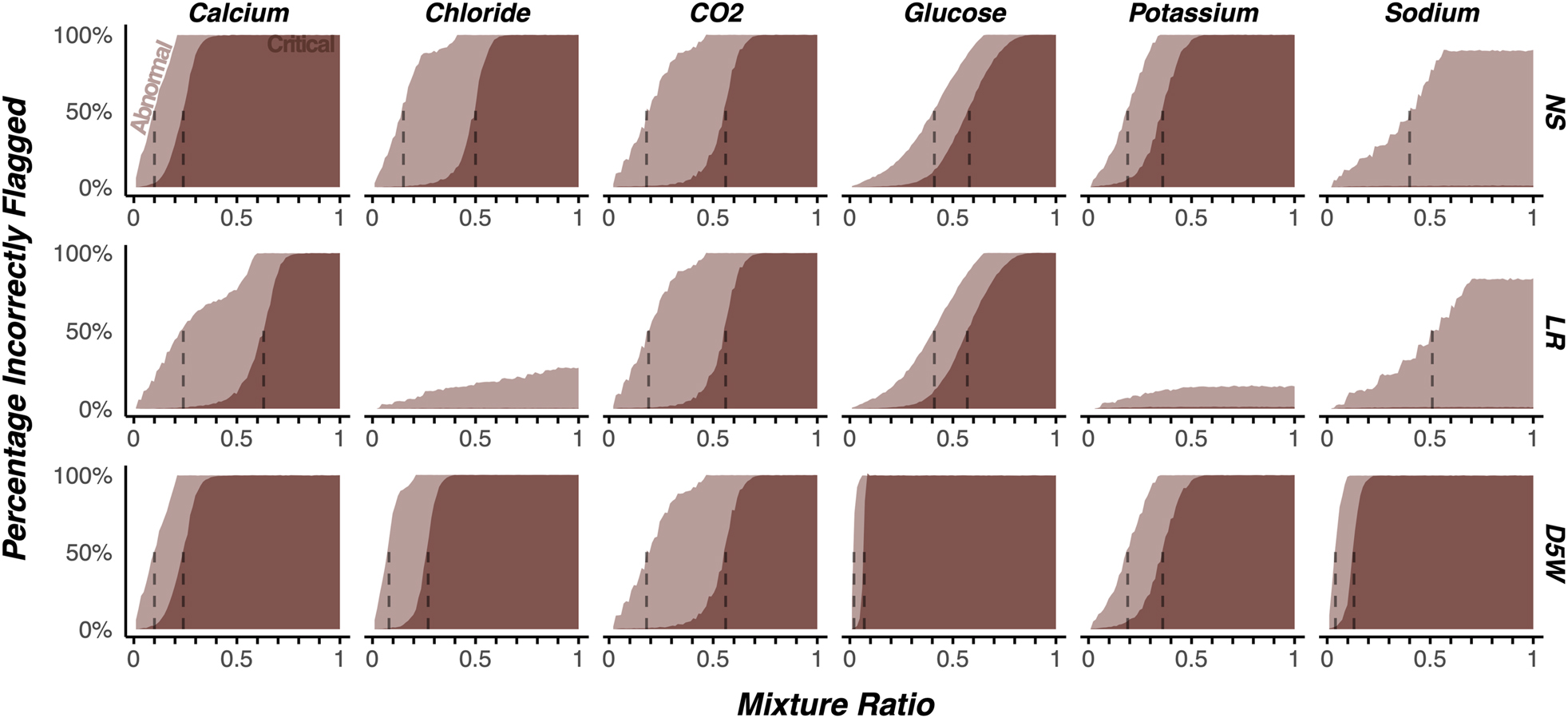

Figure 3 displays the estimated proportion of results for which the interpretation of the normality of the result would be incorrect due to contamination. The y-axis represents the proportion of results for which the true normality flag does not match that of the simulated contamination. For NS and D5W, a mixture ratio of 0.10 was sufficient to cause a majority of calcium results to be incorrectly flagged, and a ratio of 0.22 caused a majority to display an incorrect critical flag. Similar results were observed for LR contamination at mixture ratios of 0.21 and 0.62 respectively for calcium. For all fluids, a mixture ratio of 0.18 was sufficient to cause a majority of CO2 results to be incorrectly flagged, while a mixture of 0.58 would cause a majority to display an incorrect critical flag. For glucose, a mixture ratio of 0.01 was sufficient to cause a majority of results to display an incorrect abnormal flag, while a ratio of 0.08 was sufficient for critical flags. Similarly, in D5W contamination, a mixture ratio of 0.03 was sufficient to cause a majority of sodium results to be incorrectly reported, and a ratio of 0.12 caused a majority to display an incorrect critical flag. LR contaminated fluids required the highest proportion of contamination across all analytes to cause an erroneously flagged abnormal or critical result relative to NS and D5W.

The impact of simulated contamination on the proportion of results reported with incorrect abnormal or critical flags across a subset of clinically relevant analytes and fluids.

Contamination at a mixture ratio of 0.10 is sufficient to cause incorrect abnormal and critical flags

Figure 4 displays the proportion of results that change from normal to abnormal or critical at a mixture ratio of 0.10, chosen due to its impact on the metrics described above. For clarity, only a subset of particularly clinically relevant analytes are shown. A total of 51.39 % of calcium results and 21.17 % of potassium results would be incorrectly reported with an abnormal/critical flag with 10 % normal saline (NS) contamination. Of these, 47.04 % of calcium results that were within the normal range would be reported as low and 0.06 % reported as critical. Of the low calcium results, 2.34 % would be erroneously reported as critical. 13.09 % of truly normal potassium results would be erroneously reported as low, while 0.64 % reported as critical. 6.7 % of high potassium results would be erroneously reported as normal. Similar patterns were observed for the results contaminated by lactated Ringer’s (LR), though to a lesser extent. Contamination by D5W at a mixture ratio of 0.10 resulted in all results flagged as critical for glucose, regardless of their true value. Similarly, a contamination ratio of 0.10 resulted in 99.74 % of sodium results to be incorrectly flagged.

The impact of contamination at a mixture ratio of 0.10 on the proportion of results displaying each flag. On-diagonal tiles represent correctly flagged results, while off-diagonal results are incorrectly flagged. Grey tiles are those in which the result flag was correctly reported, light red tiles are off by one level (e.g. abnormal to normal), dark red are incorrect by at least two levels (e.g. critically high to normal, or abnormally high to abnormally low).

Estimating the severity of contaminated results by comparison to re-draws

Retrospective BMP results flagged as contaminated by a laboratory technologist (for which a redrawn specimen was measured within 4 h) were analyzed to assess the severity of contamination. Figure 5 displays the distribution of mixture ratios for these results. For results contaminated by a dextrose-containing fluid (blue), the median mixture ratio was 0.18, and the interquartile range was 0.09–0.27. For results contaminated by fluids without dextrose (orange), the median contamination ratio was 0.24 and interquartile range was 0.16–0.38. The bootstrapped 95 % confidence interval for the difference between the medians between D5 and non-D5 contamination was 0.03–0.11.

Estimated mixture ratios by IV fluids using calcium or glucose as a surrogate measure in specimens identified as contaminated by a laboratory technologist during routine laboratory testing.

Discussion

In this work, we have objectively characterized the impact of IV fluid contamination through the lens of total allowable error (TEa), reference change values (RCV) and normality flags. To our knowledge, no studies exist in the published literature that use analytic targets to define the proportion of contamination that is analytical and clinically relevant. We highlight a mixture of 10 % as one that often exceeds TEa and RCV thresholds while also observing that serial results contaminated at this ratio would often display incorrect abnormal or critical flags, or perhaps worse, be incorrectly flagged as normal when the true result was critical. We also find that the distribution of mixture ratios detected by our current workflow suggests that the current approach used by our laboratory and many others is insufficient to detect relevant IV fluid contamination, especially for fluids without 5 % dextrose. Together, these results highlight that the current reliance on univariate delta checks, limit checks, feasibility flags, and manual technologist intervention lacks the appropriate sensitivity for detecting relevant contamination by common IV fluids.

Another interesting finding from this study is that the relevance of contamination is highly dependent on the type of fluid in the specimen. The more physiologically balanced composition, lactated Ringer’s, required greater mixture ratios to exceed common thresholds, while minute mixtures of D5W would likely be quite relevant. This finding generalized across TEa, RCV, and the abnormal/critical flags. A similar principle was also true for specific analytes. For example, potassium and calcium were far more brittle to contamination than sodium and creatinine. However, CO2 and BUN demonstrated marked discrepancies between TEa and RCV, with substantially more severe contamination being required to exceed these RCVs. Altogether, these results imply the potential need for more sophisticated solutions than delta checks to identify contamination.

A strength of this study was the application of reference intervals for distinguishing relevant proportions of contamination; a metric that may be more clinically relevant than TEa or RCV. Strikingly, 51.39 % of calcium results and 21.17 % of potassium results when contaminated with 10 % NS would have been incorrectly reported with an abnormal/critical flag. While speculation, it is reasonable to surmise that a potassium result that exceeds the RCV due to contamination but remains within the reference interval is less likely to elicit a response from a provider than a potassium result that is inappropriately reported as critical due to contamination with NS. Further studies are required to assess the impact of IV fluid contamination on provider action. Nonetheless, the results from this study imply that at even 10 % contamination, results and subsequent reporting flags are highly likely to be impacted potentially increasing risk of inappropriate treatment for patients. This finding was particularly striking when considering the observed mixture ratio distributions in our routine clinical processes. Median mixture ratios of 0.18 and 0.24 for D5 and non-D5 fluids may suggest that our current, technologist-driven process lacks sufficient sensitivity to detect more subtle, but still clinically relevant contamination events, though it is important to note that the distinction between these two labels was made by an ad hoc cut-off of 300 mg/dL glucose.

The impact of this work must be viewed within the broader context of the recent advances being made to categorize and reduce the impact that preanalytical errors have on patient care. While many laboratory errors are well-characterized, easily observed, and carefully monitored, progress in the area of contamination by IV fluids and other non-microbial sources has lagged [31]. The IFCC working group on laboratory error and patient safety has spearheaded efforts to define and harmonize these errors, most notably with the inclusion of contamination in the 2019 report on quality indicators [32]. However, given the absence of a gold-standard for the detection of IV fluid-contamination, practice often relies on single-analyte delta checks and feasibility flags requiring technologist intervention. If the findings in this study generalize more broadly, then the reported incidence of contamination errors may be substantially underestimated. This study highlights the need for a sensitive, robust, and generalizable approach to the detection of contamination.

There are several limitations to this work worthy of explicit review. First, the threshold used in this study (10 %) does not represent a universal consensus as to the precise mixture threshold at which a contamination event becomes clinically significant, as such a designation is inextricably linked with the clinical context in which it occurs. However, framing the often esoteric concept of contamination within the more familiar lens of the total allowable error, reference change value, and reference intervals provides valuable insight that can guide the optimization of institution-specific detection protocols. Next, while the simulation approach used in this work was motivated by the results of real-world wet bench experiments and a brief validation was performed, future work characterizing the presence and extent of inter-analyte variation in contaminated results is necessary before adapting the approach more broadly. Finally, this work highlights the findings at a single healthcare system, and the generalizability of the conclusions must be assessed by repeating the analysis on a broader scope. However, the code and anonymized data used to perform this analysis is available (see methods), with the goal of reducing the barrier to replication and reproduction.

In conclusion, contamination ratios of at least 0.10 are sufficient to change the TEa, RCV, and critical/abnormal flags in BMP results. Additionally, we have presented evidence that the univariate delta checks and feasibility flags lack sufficient sensitivity for identifying clinically significant contamination by IV fluids of basic metabolic panel results. Future research towards an accurate, generalizable, and implementable solution to this universal problem is imperative to improve the quality of the results we report.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Mark A Zaydman for his invaluable contributions to extracting and preparing the data used in this study.

-

Research ethics: This study was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB #202202030).

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. NCS and CWF contributed equally to this work.

-

Competing interests: CWF has received research support from Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Serbia, Beckman Coulter, Blue Jay Diagnostics, Biomerieux, Cepheid, and Qiagen; consulting fees from Biorad, Roche, Abbott, Cytobale, and Werfen; and honoraria from Abbott, Roche, and AACC. NCS has no conflicts of interest to report.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The anonymized data used for this project can be found on FigShare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23805456.v1.

-

Software availability: The code used to analyze these data and generate the figures can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/nspies13/contamination_simulation.

References

1. Mold, JW, Stein, HF. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med 1986;314:512–4. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198602203140809.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Plebani, M. Laboratory-associated and diagnostic errors: a neglected link. Diagnosis 2014;1:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0030.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Balogh, EP, Miller, BT, Ball, JR. Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, editors. Improving diagnosis in health care [Internet]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2015.10.17226/21794Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Graber, ML. The physician and the laboratory: partners in reducing diagnostic error related to laboratory testing. Pathol Patterns Rev 2006;126:S44–7. https://doi.org/10.1309/54xr770u8wtegg1h.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Jara-Aguirre, JC, Smeets, SW, Wockenfus, AM, Karon, BS. Blood gas sample spiking with total parenteral nutrition, lipid emulsion, and concentrated dextrose solutions as a model for predicting sample contamination based on glucose result. Clin Biochem 2018;55:93–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Cornes, MP. Exogenous sample contamination. Sources and interference. Clin Biochem 2016;49:1340–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.09.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Lippi, G, Avanzini, P, Sandei, F, Aloe, R, Cervellin, G. Blood sample contamination by glucose-containing solutions: effects and identification. Br J Biomed Sci 2013;70:176–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09674845.2013.11978286.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Sinha, S, Jayaram, R, Hargreaves, CG. Fatal neuroglycopaenia after accidental use of a glucose 5 % solution in a peripheral arterial cannula flush system. Anaesthesia 2007;62:615–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.04989.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Clarke, W, American Association for Clinical Chemistry, editors. Contemporary practice in clinical chemistry, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: AACC Press; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Choucair, I, Lee, ES, Vera, MA, Drongmebaro, C, El-Khoury, JM, Durant, TJS. Contamination of clinical blood samples with crystalloid solutions: an experimental approach to derive multianalyte delta checks. Clin Chim Acta 2023;538:22–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2022.10.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Iizuka, Y, Kume, H, Kitamura, M. Multivariate delta check method for detecting specimen mix-up. Clin Chem 1982;28:2244–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/28.11.2244.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Ovens, K, Naugler, C. How useful are delta checks in the 21st century? A stochastic-dynamic model of specimen mix-up and detection. J Pathol Inform 2012;3:5. https://doi.org/10.4103/2153-3539.93402.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Zhou, R, Liang, YF, Cheng, HL, Wang, W, Huang, DW, Wang, Z, et al.. A highly accurate delta check method using deep learning for detection of sample mix-up in the clinical laboratory. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022;60:1984–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2021-1171.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Baron, JM, Mermel, CH, Lewandrowski, KB, Dighe, AS. Detection of preanalytic laboratory testing errors using a statistically guided protocol. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;138:406–13. https://doi.org/10.1309/ajcpqirib3ct1ejv.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Sandberg, S, Fraser, CG, Horvath, AR, Jansen, R, Jones, G, Oosterhuis, W, et al.. Defining analytical performance specifications: consensus statement from the 1st strategic conference of the European federation of clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:833–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-0067.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Fraser, CG. The 1999 Stockholm consensus conference on quality specifications in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:837–40. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2014-0914.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Standardization IO for medical laboratories: particular requirements for quality and competence, 2nd ed. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization; 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Panteghini, M, Ceriotti, F, Jones, G, Oosterhuis, W, Plebani, M, Sandberg, S, et al.. Strategies to define performance specifications in laboratory medicine: 3 years on from the Milan strategic conference. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:1849–56. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2017-0772.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Badrick, T. Biological variation: understanding why it is so important? Pract Lab Med 2021;23:e00199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plabm.2020.e00199.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Sithiravel, C, Røysland, R, Alaour, B, Sylte, MS, Torsvik, J, Strand, H, et al.. Biological variation, reference change values and index of individuality of GDF-15. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022;60:593–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2021-0769.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Hong, J, Cho, E, Kim, H, Lee, W, Chun, S, Min, W. Application and optimization of reference change values for Delta checks in clinical laboratory. J Clin Lab Anal 2020;34:e23550. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23550.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Stroobants, AK, Goldschmidt, HMJ, Plebani, M. Error budget calculations in laboratory medicine: linking the concepts of biological variation and allowable medical errors. Clin Chim Acta 2003;333:169–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-8981(03)00181-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Emre, HO, Karpuzoglu, FH, Coskun, C, Sezer, ED, Ozturk, OG, Ucar, F, et al.. Utilization of biological variation data in the interpretation of laboratory test results – survey about clinicians’ opinion and knowledge. Biochem Med 2021;31:010705. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2021.010705.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA ‘88). 42 CFR 493, 100–578. 1988:1536–67.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Chemical pathology analytical performance specifications [Internet]. Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Quality Assurance Program. Available from: https://rcpaqap.com.au/resources/chemical-pathology-analytical-performance-specifications/ [Accessed July 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

26. Arsand, A, Fernandez-Calle, C, Webster, C, Coskun, A, Jonker, N, Sandberg, S. The EFLM biological variation database. Available from: https://biologicalvariation.eu/ [Accessed 20 Apr 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

27. Fokkema, MR, Herrmann, Z, Muskiet, FAJ, Moecks, J. Reference change values for brain natriuretic peptides revisited. Clin Chem 2006;52:1602–3. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2006.069369.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Wickham, H, Averick, M, Bryan, J, Chang, W, McGowan, L, François, R, et al.. Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 2019;4:1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Landau, WM. The targets R package: a dynamic make-like function-oriented pipeline toolkit for reproducibility and high-performance computing. J Open Source Softw 2021;6:2959. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02959.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Spies, N. 2,500,000 anonymized BMP results for the manuscript “automating the detection of IV fluid contamination using unsupervised machine learning”. Figshare; 2023:195861997 p. Available from: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/2_500_000_anonymized_BMP_results_for_the_manuscript_Automating_the_Detection_of_IV_Fluid_Contamination_Using_Unsupervised_Machine_Learning_/23805456/1 [Accessed 14 Aug 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

31. Plebani, M, O’Kane, M, Vermeersch, P, Cadamuro, J, Oosterhuis, W, Sciacovelli, L, et al.. The use of extra-analytical phase quality indicators by clinical laboratories: the results of an international survey. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016;54:e315–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0770.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Sciacovelli, L, Lippi, G, Sumarac, Z, Del Pino Castro, IG, Ivanov, A, De Guire, V, et al.. Pre-analytical quality indicators in laboratory medicine: performance of laboratories participating in the IFCC working group “laboratory errors and patient safety” project. Clin Chim Acta 2019;497:35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.07.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/labmed-2023-0098).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial to: German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine – areas of expertise – division reports from the German Congress of Laboratory Medicine 2022 in Mannheim, 13–14 October 2022

- Report

- German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine – areas of expertise: Division reports from the German Congress of Laboratory Medicine 2022 in Mannheim, 13–14 October 2022

- Original Articles

- Impact and frequency of IV fluid contamination on basic metabolic panel results using quality metrics

- A quality control procedure for central venous blood sampling based on potassium concentrations

- Establishment of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I reference interval for a hospitalized paediatric population under improved selection criteria in the Shandong area

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial to: German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine – areas of expertise – division reports from the German Congress of Laboratory Medicine 2022 in Mannheim, 13–14 October 2022

- Report

- German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine – areas of expertise: Division reports from the German Congress of Laboratory Medicine 2022 in Mannheim, 13–14 October 2022

- Original Articles

- Impact and frequency of IV fluid contamination on basic metabolic panel results using quality metrics

- A quality control procedure for central venous blood sampling based on potassium concentrations

- Establishment of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I reference interval for a hospitalized paediatric population under improved selection criteria in the Shandong area