Effect of bone marrow mononuclear cells therapy on long-term survival of patients with liver cirrhosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using propensity score matching

-

Mengfan Ruan

and Xingshun Qi

Abstract

Background

Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) therapy should be effective for the improvement of liver function and short-term outcome in patients with liver cirrhosis, but few studies have explored the long-term prognosis of cirrhotic patients treated with BMMNCs.

Methods

In this retrospective study, eligible patients with liver cirrhosis were selected by using propensity score matching (PSM). Effect of BMMNCs on death was explored by Cox regression analysis, as well as competing risk analysis, where liver transplantation was a competing event. Hazard ratio (HR) and sub-distribution HR (sHR) were calculated. Subgroup analyses were performed based on the age, sex, Child-Pugh class, and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score.

Results

Overall, 260 patients were included, of whom 130 were treated with transhepatic arterial transplantation of BMMNCs. The median follow-up duration was 5.27 (range: 0.37–16.62) years. By adjusting by age, sex, and Child-Pugh score, multivariate Cox regression (HR = 0.707, P = 0.020) and competing risk analyses (sHR = 0.709, P = 0.026) demonstrated that BMMNCs were independently associated with a lower risk of death in cirrhotic patients in the overall analysis. Univariate Cox regression analyses demonstrated that BMMNCs were significantly associated with a decreased risk of death in the subgroup analyses of age ≤50 years (HR= 0.533, P = 0.016), male (HR = 0.626, P = 0.010), Child-Pugh class B (HR = 0.638, P = 0.026), and MELD score > 12 (HR = 0.483, P = 0.002), but not age > 50 years (P = 0.097), female (P = 0.170), Child-Pugh class A (P = 0.309), Child-Pugh class C (P = 0.369), or MELD score ≤12 (P = 0.096).

Conclusion

BMMNCs can provide additional survival benefits in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Liver diseases cause about 2 million deaths per year, accounting for 4% of the total deaths globally, primarily due to cirrhosis and its complications.[1] Cirrhosis is associated with long-term inflammation caused by a variety of causes, including viral hepatitis, steatohepatitis, alcohol abuse, and autoimmune hepatitis.[2] Patients with early cirrhosis are often asymptomatic, while those with decompensated cirrhosis can suffer from progressive aggravation of portal hypertension, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and liver failure, which compromises the quality of life and survival.[2, 3, 4] When the liver is slightly and transiently damaged, it can be repaired by rapid proliferation of hepatocytes; by comparison, when cirrhosis develops, especially decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplantation is the only curative treatment.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] However, only a minority of patients who meet the criteria for liver transplantation can undergo liver transplantation due to the lack of liver donors, its high cost, and the requirement of life-long immunosuppressants.[11] Therefore, it is particularly important to seek for other alternatives to repair chronically injured liver and regenerate hepatic parenchymal.[12]

Currently, cell therapy has emerged as a promising approach for the treatment of liver-related diseases due to its self-renewal, paracrine, and immunomodulatory effects.[13,14] Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) are a heterogeneous cell population, including hematopoietic stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and immune cells. This cell population can produce its therapeutic effect mainly through multiple ways. First, hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells to participate in liver tissue repair. Second, mesenchymal stem cells can promote hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and inhibit fibrosis process by secreting hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other bioactive factors. Third, immune regulatory cells can reduce liver inflammatory microenvironment.[15,16] Because complex preparation or culture of BMMNCs is not required, they become an attractive option for cell therapy in regenerative medicine. Thus, they have been widely used in experimental and clinical studies.[17,18] Until now, several studies have shown the efficacy of BMMNCs for the treatment of cirrhosis.[19, 20, 21] Notably, current evidence supports the benefits of BMMNCs for improving liver function and short-term prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis, but their effects on long-term survival have been rarely explored yet.[22,23] Herein, we attempt to address this issue by reviewing the data of cirrhotic patients who were hospitalized at our center and followed for more than 10 years.

Materials and methods

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command with an ethical approval number (Y[2024]208). The patient’s informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Study design

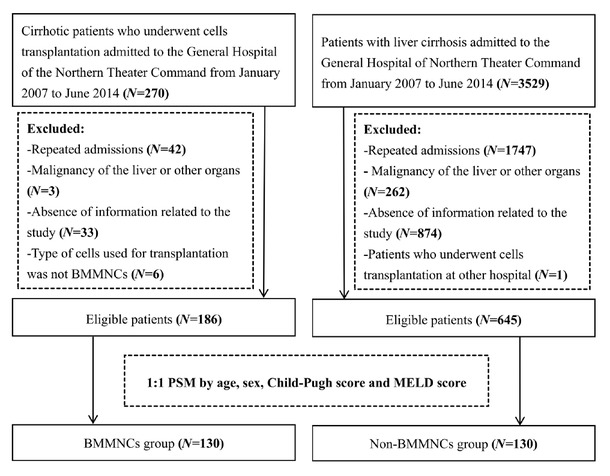

By searching the diagnostic code of liver cirrhosis in the electronic medical record system of our hospital, a total of 3799 patients with liver cirrhosis who were consecutively admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology of our hospital from January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2014 were identified. Among them, 270 patients with cirrhosis underwent cells transplantation during hospitalization, who are considered as the BMMNCs group. The exclusion criteria of the BMMNCs group were as follows: (1) repeated admissions of the same patients; (2) patients with a history of liver or other malignancy; (3) patients with incomplete data information related to the study; and (4) the type of cells used for transplantation was not BMMNCs. The remaining 3529 patients with cirrhosis received conventional treatment without cells transplantation during hospitalization, who are considered as the non-BMMNCs group. The exclusion criteria of the non-BMMNCs group were as follows: (1) repeated admissions of the same patients; (2) patients with a history of liver or other malignancy; (3) patients with incomplete data information related to the study; and (4) patients who underwent BMMNCs transplantation at other hospital.

Propensity score matching analysis

Propensity score matching (PSM) method was used to select the control group from 831 eligible patients with liver cirrhosis. In this study, multivariable logistic regression model was used to estimate propensity scores for all patients with the following baseline characteristics as covariates, including age, gender, Child-Pugh score, and model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score. According to the propensity score calculated, the one-to-one PSM analysis was performed using the nearest neighbour method with a caliper of 0.2.[24]

Baseline data collection

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data at admissions were collected, including age, gender, etiology of liver cirrhosis (i.e., hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and alcohol abuse), decompensation event (i.e., ascites, HE, and gastrointestinal bleeding), hemoglobin (Hb), white blood cell, platelet count, total bilirubin, albumin (ALB), aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, serum creatinine, serum sodium, and international normalized ratio. Child-Pugh and MELD scores were calculated.[25]

Groups and definitions

Eligible patients were divided into BMMNCs group and non-BMMNCs group. BMMNCs group was defined as patients with liver cirrhosis who underwent conventional therapy in combination with BMMNCs transplantation, and non-BMMNCs group as patients with liver cirrhosis who received conventional therapy alone. According to the current clinical guidelines, including the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, conventional treatment strategies of liver cirrhosis and its complications mainly include etiological therapy, antifibrotic drugs, albumin supplementation, diuresis, endoscopic variceal treatment, and other symptomatic treatments.[26, 27]

Procedures

Collection and isolation of BMMNCs

After patients signed written informed consents, subcutaneous injection of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was given at a dosage of 100 μg as bone marrow mobilization for 2 consecutive days before BMMNCs collection. At the day of BMMNCs collection, they were placed in a sterile room, and their posterior superior iliac spines were selected as the point of bone marrow puncture. After local sterilization and anesthesia, 150–200 mL of bone marrow was extracted by an 18-gauge bone marrow puncture needle. Then, remove bone fragments and fat particles through a 70–200 μm filter, add unfractionated heparin, and store at 4 ℃ for less than 24 h. Separate cell components by density gradient. Dilute bone marrow blood with PBS at a ratio of 1: 1–1: 2. Then, they were carefully superimposed on Ficol-Paque (density 1.077 g/mL), centrifuged (400–450 g, 30–40 min, room temperature, no brake) to collect mononuclear cell layers, and washed with PBS 2–3 times (300 g, 10 min). Isolated cells were resuspended with saline. After that, the number of cells was counted using Trypan blue staining or automatic cell counter. The target number of cells was usually 2–4×108 MNC/ kg body weight. Cell viability was measured using Trypan blue rejection (> 90% viability) or 7-AAD/Annexin V flow assay. Cell quality was strictly controlled, as follows: the microbial test of aerobic bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, and fungi was negative, the endotoxin test was < 5EU/kg, and the proportion and number of CD34+ cells in the cells were required to reach the predetermined target dose. The cell separation and purification took about 2.5–3 h. Then, according to the clinical requirements, the cells were fully mixed with 1–5 mL of normal saline in a cell transfer tube, the total volume was about 13–15 mL per patient, and 2 mL was reserved at the Department of Medical Laboratory of our hospital for subsequent quality monitoring. The cell transfer tube was marked with the patient’s name and bed number, wrapped with surgical foreskin, and placed in an ice bucket for clinical use.

Transplantation of BMMNCs

Under digital subtraction angiography, a femoral artery puncture cannula was inserted into the proper hepatic artery to observe intrahepatic vascular conditions and space-occupying lesions. About 10 mL of the spare cell suspensions were then slowly injected through the left and right hepatic arteries within 3 h. After extubation, the puncture site was bandaged with pressure. The lower extremity on the side of puncture remained immobilized for 6 h. Transplantation should be performed within 6 h after cells isolation and purification.

Follow up

All patients were followed by reviewing their inpatient or outpatient medical records and conducting telephone interviews. The last follow-up date was November 6, 2023. Specific dates of death during follow-up were requested as well as liver transplantation, if any.

Statistical analyses

PSM was employed to identify the patients assigned to the BMMNCs group and non-BMMNCs group. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and median (range), and compared using the student t tests or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were expressed as frequency (percentage) and compared with the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Cox regression and competing risk analyses were performed to explore the predictors of death in cirrhotic patients. Hazard ratio (HR) and sub-distribution hazard ratio (sHR) and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Multivariate Cox regression analyses and competing risk analyses were performed by adjusting for age, sex, and Child-Pugh score to explore whether BMMNCs transplantation was an independent predictor of death. Competing event for death was liver transplantation. Kaplan-Meier curve and Nelson-Aalen cumulative risk curve analyses were used to evaluate the cumulative rates of death, and compared by the logrank tests and Gray’s tests, respectively. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the impact of BMMNCs transplantation on the prognosis of cirrhotic patients according to the age, sex, Child-Pugh class, and MELD score. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/ SE 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) software, IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA), and R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with packages ggplot2, survival, survminer, cmprsk and forestplot.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 831 patients were potentially eligible, of whom 186 received conventional therapy in combination with BMMNCs transplantation and 645 received conventional therapy alone. After PSM, 130 patients were included in each group (Figure 1).

Flowchart of patients’ screening and grouping. BMMNCs: bone marrow mononuclear cells; PSM, propensity score matching; MELD: model for end-stage liver disease.

Baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Their mean age was 53.27 ± 11.12 years, and 172 (66.2%) patients were male. The most common etiology of liver cirrhosis was hepatitis B virus infection (43.1%). The mean MELD and Child-Pugh scores were 12.07 ± 5.28 and 7.60 ± 2.02, respectively.

Characteristics of included patients.

| Overall group (N=260) |

BMMNCs group (N=130) |

Non-BMMNCs group (N=130) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. Pts | Mean ± SD, Median (range) or Frequency (percentage) | No. Pts | Mean ± SD, Median (range) or Frequency (percentage) | No. Pts | Mean ± SD, Median (range) or Frequency (percentage) | P Value |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 260 | 53.27 ± 11.12 | 130 | 52.96 ± 10.97 | 130 | 53.58 ± 11.30 | 0.652 |

| 53.78 (20.10-82.68) | 54.04 (25.85-82.68) | 53.29 (20.10-78.39) | |||||

| Male (%) | 260 | 172 (66.2%) | 130 | 85 (65.4%) | 130 | 87 (66.9%) | 0.793 |

| Etiology of liver cirrhosis | |||||||

| HBV infection alone (%) | 260 | 112 (43.1%) | 130 | 77 (59.2%) | 130 | 35 (26.9%) | <0.001 |

| HCV infection alone (%) | 260 | 25 (9.6%) | 130 | 14 (10.8%) | 130 | 11 (8.5%) | 0.528 |

| Alcohol-related liver disease alone (%) | 260 | 66 (25.4%) | 130 | 16 (12.3%) | 130 | 50 (38.5%) | <0.001 |

| Complications at admission | |||||||

| Ascites (%) | 260 | 153 (58.8%) | 130 | 76 (58.5%) | 130 | 77 (59.2%) | 0.900 |

| HE (%) | 260 | 17 (6.5%) | 130 | 8 (6.2%) | 130 | 9 (6.9%) | 0.802 |

| GIB (%) | 260 | 60 (23.1%) | 130 | 18 (13.8%) | 130 | 42 (32.3%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||||||

| 97.88 ± 27.69 | 103.71 ± 25.70 | 92.10 ± 28.47 | |||||

| HB (g/L) | 259 | 98.00 (31.00-165.00) | 129 | 104.00 (44.00-161.00) | 130 | 92.00 (31.00-165.00) | <0.001 |

| WBC (109/L) | 259 | 4.95 ± 3.21 | 129 | 4.91 ± 3.30 | 130 | 5.00 ± 3.14 | 0.530 |

| 4.20 (1.20-24.70) | 4.10 (1.20-19.20) | 4.40 (1.20-24.70) | |||||

| 91.64 ± 64.93 | 88.53 ± 57.76 | 94.73 ± 71.44 | |||||

| PLT (109/L) | 259 | 74.00 (17.00-464.00) | 129 | 71.00 (21.00-320.00) | 130 | 80.50 (17.00-464.00) | 0.526 |

| 34.04 ± 37.31 | 32.56 ± 32.97 | 35.53 ± 41.28 | |||||

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 260 | 22.20 (3.80-372.10) | 130 | 24.35 (5.00-332.60) | 130 | 21.50 (3.80-372.10) | 0.400 |

| ALB (g/L) | 260 | 32.72 ± 6.93 | 130 | 34.14 ± 6.82 | 130 | 31.31 ± 6.76 | <0.001 |

| 32.85 (12.40-52.10) | 34.30 (15.40-52.10) | 31.10 (12.40-45.90) | |||||

| 63.06 ± 94.46 | 63.43 ± 100.89 | 62.78 ± 87.94 | |||||

| AST (U/L) | 260 | 41.00 (9.00-1079.00) | 130 | 42.50 (10.00-1079.00) | 130 | 39.00 (9.00-819.00) | 0.322 |

| 49.99 ± 107.65 | |||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 260 | 30.50 (6.00-1460.00) | 130 | 47.88 ± 70.60 34.00 (9.00-756.00) | 130 | 52.10 ± 135.18 27.00 (6.00-1460.00) | 0.013 |

| 109.99 ± 82.66 | 107.73 ± 89.95 | 112.26 ± 74.95 | |||||

| AKP (U/L) | 260 | 86.50 (34.00-631.00) | 130 | 83.50 (35.00-631.00) | 130 | 88.85 (34.00-466.60) | 0.286 |

| 79.66 ± 95.11 | 86.95 ± 107.96 | 72.38 ± 80.00 | |||||

| Scr (μmol/L) | 260 | 60.00 (30.00-904.00) | 130 | 65.00 (30.00-904.00) | 130 | 57.00 (30.00-742.00) | 0.005 |

| 139.19 ± 4.00 | 139.95 ± 3.50 | 138.44 ± 4.32 | |||||

| Na (mmol/L) | 258 | 139.70 (122.70-147.70) | 128 | 140.60 (129.40-146.80) | 130 | 139.35 (122.70-147.70) | 0.004 |

| INR | 260 | 1.32 ± 0.38 | 130 | 1.30 ± 0.35 | 130 | 1.34 ± 0.41 | 0.380 |

| 1.22 (0.82-3.64) | 1.20 (0.88-2.49) | 1.23 (0.82-3.64) | |||||

| 7.60 ± 2.02 | 7.40 ± 2.06 | 7.81 ± 1.96 | |||||

| Child-Pugh score | 260 | 7.00 (5.00-13.00) | 130 | 7.00 (5.00-13.00) | 130 | 8.00 (5.00-13.00) | 0.085 |

| Child-Pugh class | |||||||

| A (%) | 260 | 81 (31.2%) | 130 | 47 (36.2%) | 130 | 34 (26.2%) | 0.082 |

| B (%) | 260 | 136 (52.3%) | 130 | 61 (46.9%) | 130 | 75 (57.7%) | 0.082 |

| C (%) | 260 | 43 (16.5%) | 130 | 22 (16.9%) | 130 | 21 (16.2%) | 0.867 |

| 12.07 ± 5.28 | 11.69 ± 4.76 | 12.45 ± 5.74 | |||||

| MELD score | 260 | 10.59 (2.39-31.57) | 130 | 10.69 (2.39-27.17) | 130 | 10.50 (6.43-31.57) | 0.650 |

ALB, albumin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; BMMNCs, bone marrow mononuclear cells; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HB, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; No. Pts, number of patients; Na, serum sodium; PLT, platelet count; SD, standard deviation; Scr, serum creatinine; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell.

The proportion of male (65.4% vs. 66.9%, P = 0.793), age (52.96 ± 10.97 years vs. 53.58 ± 11.30 years, P = 0.652), MELD score (11.69 ± 4.76 vs. 12.45 ± 5.74, P = 0.650), and Child-Pugh score (7.40 ± 2.06 vs. 7.81 ± 1.96, P = 0.085) were not significantly different between BMMNCs group and non-BMMNCs group. BMMNCs group had significantly higher Hb level (103.71 ± 25.70 g/L vs. 92.10 ± 28.47 g/L, P < 0.001) and ALB level (34.14 ± 6.82 g/L vs. 31.31 ± 6.76 g/L, P < 0.001), but a lower proportion of GIB (13.8% vs. 32.3%, P < 0.001) than non-BMMNCs group (Table 1).

Overall analysis

During a median follow-up period of 5.27 years (range: 0.37–16.62 years), 5 (1.9%) underwent liver transplantation and 130 (50.0%) died.

Univariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that BMMNCs transplantation was significantly associated with a lower risk of death in cirrhotic patients (HR = 0.648, 95% CI = 0.484–0.868, P = 0.004). Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that BMMNCs transplantation was still independently associated with a lower risk of death (HR = 0.707, 95%CI = 0.528–0.946, P = 0.020).

Univariate competing risk analysis demonstrated that BMMNCs transplantation was significantly associated with a lower risk of death in cirrhotic patients (sHR = 0.652, 95%CI = 0.488–0.871, P = 0.004). Multivariate competing risk analysis also showed that BMMNCs transplantation was significantly associated with a lower risk of mortality (sHR = 0.709, 95%CI = 0.524–0.959, P = 0.026).

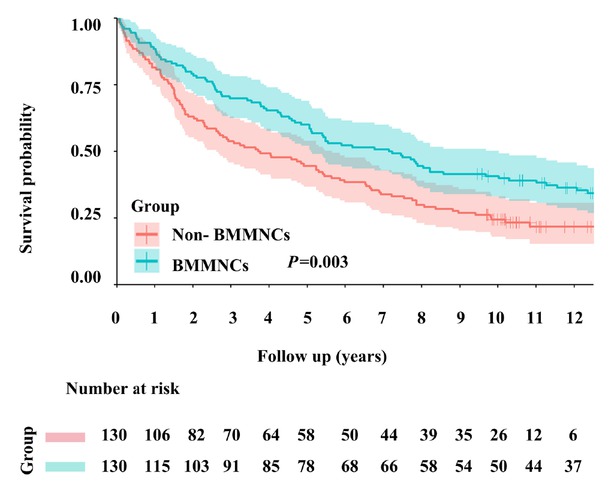

The 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year cumulative survival rates were 88.5%, 70.0%, 59.2%, and 39.9% in the BMMNCs group and 80.8%, 53.1%, 44.6%, and 24.5% in the non-BMMNCs group. Kaplan-Meier curve analysis demonstrated that BMMNCs group had a significantly higher cumulative survival rate than non-BMMNCs group (P = 0.003) (Figure 2).

Kaplan-Meier curve analyses demonstrating the cumulative rates of survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. BMMNCs: bone marrow mononuclear cells.

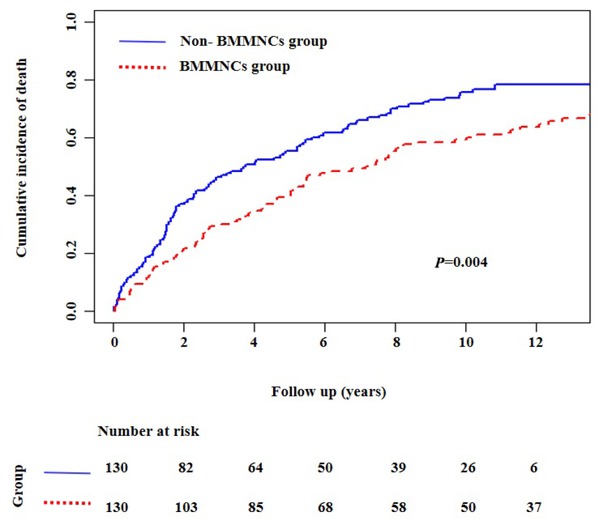

Nelson-Aalen cumulative risk curve analysis also demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of death was significantly lower in BMMNCs group than non-BMMNCs group (P = 0.004) (Figure 3).

Nelson-Aalen cumulative risk curve analyses showing the cumulative mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. BMMNCs: bone marrow mononuclear cells.

Subgroup analyses

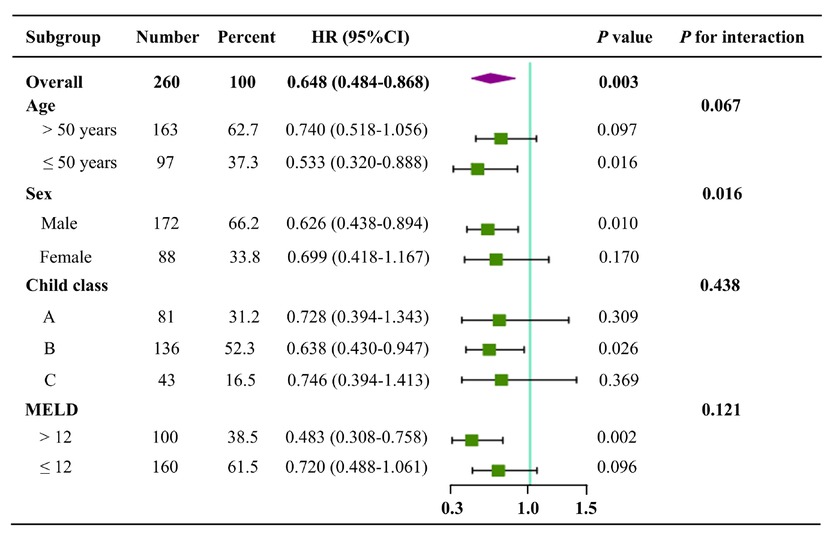

Age: Univariate Cox regression analyses showed that BMMNCs transplantation could significantly decrease the mortality in cirrhotic patients ≤50 years (HR = 0.533, 95%CI = 0.320–0.888, P = 0.016), but not those > 50 years (HR = 0.740, 95%CI = 0.518–1.056, P = 0.097) (Figure 4).

Forest plots of subgroup analyses according to age, sex, Child-Pugh class, and MELD score. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Sex: Univariate Cox regression analyses showed that BMMNCs transplantation could significantly decrease the mortality in male patients with liver cirrhosis (HR = 0.626, 95%CI = 0.438–0.894, P = 0.010), but not female patients (HR = 0.699, 95%CI = 0.418–1.167, P = 0.170) (Figure 4).

Child-Pugh class: Univariate Cox regression analyses showed that BMMNCs transplantation could significantly decrease the mortality in cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh class B (HR = 0.638, 95%CI = 0.430–0.947, P = 0.026), but not those with Child-Pugh class A (HR = 0.728, 95%C I= 0.394–1.343, P = 0.309) and C (HR = 0.746, 95%CI = 0.394–1.413, P = 0.369) (Figure 4).

MELD score: Univariate Cox regression analyses showed that BMMNCs transplantation could significantly decrease the mortality in cirrhotic patients with MELD score of > 12 (HR = 0.483, 95%CI = 0.308–0.758, P = 0.002), but not those with MELD score of ≤12 (HR = 0.720, 95%CI = 0.488–1.061, P = 0.096) (Figure 4).

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that transhepatic arterial transplantation of BMMNCs can significantly improve the prognosis of cirrhotic patients. Additionally, the benefits of BMMNCs transplantation were more pronounced in cirrhotic patients who were ≤50 years and male and had Child-Pugh class B and MELD score of > 12.

Autologous BMMNCs are a promising alternative for the treatment of advanced liver diseases. However, only short-term follow-up outcomes of BMMNCs transplantation have been reported in most of relevant studies; by comparison, the data regarding long-term prognosis of BMMNCs transplantation in cirrhosis is greatly insufficient.[23,28] Kim et al. conducted a single-arm clinical study showing that transplantation of BMMNCs is safe and can improve liver function and survival in patients with liver diseases.[29] Baldo et al. established an animal model to investigate the therapeutic effect of BMMNCs transplantation on acute liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) in rats, and found that BMMNCs transplantation can improve the survival and induce hepatocyte proliferation in rats.[30] Belardinelli et al. also conducted an animal study showing that adult-derived BMMNCs significantly improved survival in a model of acute liver failure induced by acetaminophen in rats.[31] In contrast to previous studies regarding bone marrow-derived cells for the treatment of liver disease (Table 2),[22,28,29, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44] our study not only conducted up to 16 years of follow-up, but also employed the PSM method to minimize baseline differences between the two groups, and our patients received conventional therapy combined with a single transhepatic arterial infusion of BMMNCs. Most importantly, our study had an unprecedented follow-up period of up to 16 years after transplantation of BMMNCs in cirrhotic patients and confirmed a significant survival benefit over the follow-up period. Thus, our study provides novel evidence to support the use of BMMNCs transplantation for improving the long-term prognosis of liver cirrhosis.

Summary of clinical studies of BMCs therapy for liver cirrhosis.

| First author (year) | Country | Liver disease | Sample size (BMCs/Control) | Average age (BMCs/Control) | Cell dose | Times of injection | Administration route | Follow-up period (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pai[44] (2008) | United Kingdom | Liver cirrhosis | 9 | 53 | 2.3×108cells/patient | Single | Hepatic artery | 12 |

| Salama[32] (2010) | Egypt | End-stage liver cirrhosis | 90/50 | 50.3/50.9 | 0.5×108cells/patient | Single | Portal vein | 24 |

| Peng[40] (2011) | China | HBV-related liver failure | 6/15 | 42.19/42.22 | (3.4±3.8)× 108 cells/patient | Single | Hepatic artery | 192 |

| Mohamadnejad[33] (2013) | Iran | Decompensated liver cirrhosis | 14/11 | 43.1/34.6 | (1.2–2.95)×108 cells/patient | Single | Peripheral vein | 48 |

| Spahr[34] (2013) | Switzerland | Alcohol-related liver disease | 28/30 | 54.0/56.0 | (0.47±0.15)× 108 cells/kg | Single | Hepatic artery | 12 |

| Park[43] (2013) | Korea | Liver failure | 5 | 44 | NA | Single | Hepatic artery | 16 |

| Xu[36] (2014) | China | HBV-related liver cirrhosis | 20/19 | 44.0/45.0 | (8.45±3.28)× 108 cells/patient | Single | Hepatic artery | 24 |

| Salama[35] (2014) | Egypt | HCV-related liver disease | 20/20 | 50.27/50.9 | 1×106cells/kg | Single | Peripheral vein | 26 |

| Bai[22] (2014) | China | Decompensated liver cirrhosis | 32/15 | 46.4/47.4 | NA | Single | Hepatic artery | 96 |

| Kantarcıoğlu [42] (2015) | Turkey | Liver cirrhosis | 12 | 39 | 1×106cells/kg | Single | Peripheral vein | 48 |

| Suk[38] (2016) | South Korea | Alcohol-related liver disease | 37/18 | 53.8/53.7 | 5×107cells/patient | Single/Multiple | Hepatic artery | 48 |

| Mohamadnejad[37] (2016) | Decompensated liver cirrhosis | (7.62±5.53)×108 cells/patient | ||||||

| Iran | 10/9 | 43.9/46.2 | (9.17±5.24)×108 cells/patient | Multiple | Portal vein | 48 | ||

| Kim[29] (2017) | South Korea | Decompensated liver cirrhosis | 19 | 52 | 0.925×108cells/kg | Single | Peripheral vein | 264 |

| Zhang[39] (2017) | China | Liver fibrosis | 30/30 | 31.0/32.1 | 6×106cells/patient | Multiple | Peripheral vein | 12 |

| Lin[41] (2017) | China | Acute-on-chronic liver failure | 56/54 | 40.0/42.8 | (1-10)×105cells/kg | Multiple | Peripheral vein | 24 |

| Schacher[28] (2021) | Brazil | Acute-on-chronic liver failure | 4/5 | 55.8/53.4 | 1×106cells/kg | Multiple | Peripheral vein | 13 |

BMCs, bone marrow-derived cells; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

In addition, our study also specifies target populations that would derive the most benefit from BMMNCs transplantation. The benefits of BMMNCs transplantation were more pronounced in cirrhotic patients who were ≤50 years and male and had Child-Pugh class B and MELD score of > 12. First, bone marrow monocytes should be more abundant and of higher quality in younger individuals, and the telomerase activity in stem cells should also be higher, which can maintain stronger self-renewal and differentiation ability. In addition, there are higher levels of stromal cell-derived factor 1 in younger individuals, which promotes BMMNCs homing.[45,46] Second, male patients have high testosterone content, which can up-regulate the expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in hepatocytes by activating androgen receptors to enhance the epidermal growth factor response secreted by BMMNCs.[47] Third, Child-Pugh class B and MELD score > 12 indicated moderate liver dysfunction, where hepatic regeneration signals can be more readily activated, thereby promoting the migration of BMMNCs to the injured area of the liver. Meanwhile, in the setting of moderate liver dysfunction, the remaining normal hepatocytes can also respond to these regenerative signals, thus contributing to the paracrine effect of BMMNCs. By comparison, in patients with severe liver dysfunction, hepatic regeneration is remarkably inhibited, compromising the effect of BMMNCs on regulation of liver microenvironment and promotion of liver tissue repair.[48, 49, 50]

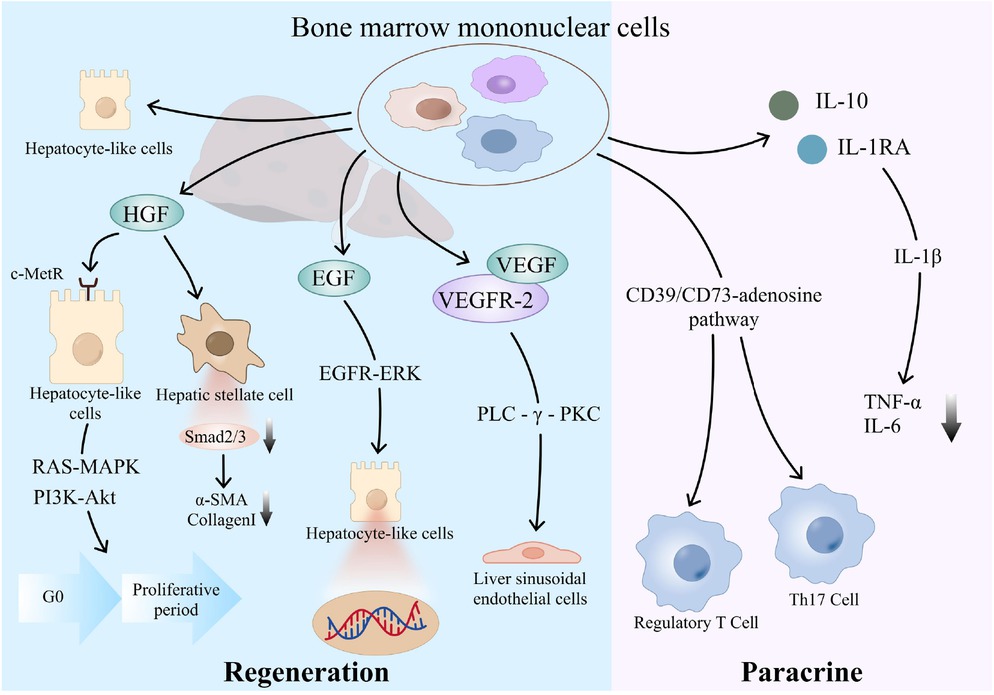

BMMNCs are known for their paracrine and regenerative promoting properties, which may play a crucial role in the regulation of liver microenvironment. First, BMMNCs is a heterogeneous cell population containing a variety of progenitor cells, in which mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells can be induced by the liver injury microenvironment to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells via the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch pathways and directly supplement functional hepatocytes.[51] It can also release a variety of growth factors, such as HGF, epidermal growth factor, and VEGF. HGF can bind to the c-Met receptor on the surface of liver cell membrane, activate the Ras-MAPK and PI3K-Akt pathways, induce the expression of cyclin, and drive hepatocytes to enter the proliferation cycle from the stationary G0 phase. Moreover, the mediation of TGF-β1 on α-SMA and collagen I expression was blocked by inhibiting Smad2/3 phosphorylation in hepatic stellate cells, and matrix metalloproteinases were upregulated to promote fiber degradation.[18,52] Epidermal growth factor enhances DNA synthesis in hepatocytes through EGFR-ERK pathway, forming a synergistic effect with HGF, which can improve the liver regeneration.[53] VEGF activates the PLC-gamma-PKC pathway by binding to VEGFR-2, stimulates the proliferation of hepatic sinusoid endothelial cells, increases functional capillary density, reduces the level of hypoxia-inducing factor-1α in liver, reduces hypoxia-driven inflammatory factors, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, increases oxygen supply to damaged liver tissue, and accelerates the repair of damaged liver tissue.[54] Second, BMMNCs can secrete IL-10 and IL-1RA, which competitively block IL-1β signaling, thereby reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, through the CD39/CD73-adenosine pathway, BMMNCs activate regulatory T cells, but suppresses Th17 cell differentiation, which contributes to the restoration of immune homeostasis, facilitates the establishment of immune tolerance, and ultimately attenuates inflammatory responses (Figure 5).[15,16] In addition, animal experiments have shown that BMMNCs can secrete anti-inflammatory proteins and reduce oxidative stress, thus promoting liver function recovery and improving the survival in rats.[55,56] Thus, stem cells should be effective for controlling inflammation. It has been shown that autologous BMMNCs transplantation seems to have good short-term efficacy in patients with viral hepatitis related liver failure.[57] Similarly, a high proportion of our study population had liver cirrhosis caused by viral hepatitis, which may be one of important causes for favorable prognosis in the BMMNCs group.

Mechanism diagram of action of BMMNCs. BMMNCs: bone marrow mononuclear cells.

In our study, a single transhepatic arterial infusion of BMMNCs was employed and G-CSF was used for bone marrow mobilization prior to cell extraction. Notably, multiple meta-analyses have shown that a single injection, transhepatic arterial infusion, and the use of bone marrow as the source of cells should be the optimal strategies for treatment of liver diseases.[58, 59, 60] This may be an important advantage of our study. First, transhepatic arterial transplantation can improve cells homing ability, which is a key prerequisite for BMMNCs to play a therapeutic role in patients with cirrhosis.[61, 62, 63] Yu et al. also indicated that enhancing cells survival rate and homing ability can augment the engraftment efficacy of cells.[64,65] Second, studies have shown that the use of G-CSF before transplantation can promote homing of BMMNCs and accelerate recovery and improve survival after liver injury by promoting endogenous repair programs.[66,67] Third, previous studies showed no significant difference in the improvement of liver function between patients who received multiple injections and those who received a single injection, suggesting that the number of BMMNCs injections may not affect the patients’ outcomes. Moreover, multiple transhepatic arterial transfusions carry a higher risk of vascular damage, thrombosis, and infection as compared to a single infusion.[58]

There are some limitations in our study. First, since this is a retrospective cohort study, the presence of selection bias and recall bias is often inevitable, which may affect the reliability of our findings to some extent. Regardless, PSM was employed to avoid these biases. Second, this study focused on the patients’ death during follow-up period. However, the specific cause of death, changes of liver function indicators, and development of decompensation events could not be provided in all patients.

In summary, BMMNCs transplantation serves as a viable alternative for cirrhotic patients who are unable to undergo liver transplantation, due to its benefits in the improvement of survival and the quality of life. In order to clarify the impact of BMMNCs transplantation on the long-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis, further large-scale prospective studies with additional end points are needed to comprehensively evaluate the short-term and long-term prognosis of patients, so as to provide more solid evidence for clinical practice.

Funding statement: The present study was partially supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Liaoning Province (2022JH2/101500032), Outstanding Youth Foundation of Liaoning Province (2022-YQ-07) and Independent Research Funding of General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (ZZKY2024018).

Acknowledgements

The abstract of this article was accepted as an oral presentation at the Asia Pacific Digestive Disease Week 2024.

-

Author Contributions

X. Qi: Conceptualization. M. Ruan, W. Ning, B. Zhang, X. Wang, and X. Qi: Data collection and audit. M. Ruan, Y. Yin, and X. Qi: Data analysis. M. Ruan, Y. Yin, H. Lin, and X. Qi: Methodology and writing. M. Ruan, Y. Yin, H. Yu, D. Zou, X. Shao, H. Li, X. Guo, J. Chen, and X. Qi: Critical comments and revision. X. Qi: Supervision. All authors have made an intellectual contribution to the manuscript and approved the submission.

-

Ethical Approval

This study was carried out following the rules of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of our hospital (Approval No. Y [2024] 208).

-

Informed Consent

Patients' written informed consents had been waived by the Medical Ethical Committee of our hospital due to the retrospective nature of this study.

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools

None declared.

-

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

1 Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol 2023;79:516–537.10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Ginès P, Krag A, Abraldes JG, Solà E, Fabrellas N, Kamath PS. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2021;398:1359–76.10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01374-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

3 D'Amico G, Bernardi M, Angeli P. Towards a new definition of decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2022;76:202–207.10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:823–832.10.1056/NEJMra0901512Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5 Yagi S, Hirata M, Miyachi Y, Uemoto S. Liver Regeneration after Hepatectomy and Partial Liver Transplantation. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:8414.10.3390/ijms21218414Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Michalopoulos GK, Bhushan B. Liver regeneration: biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:40–55.10.1038/s41575-020-0342-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Gadd VL, Aleksieva N, Forbes SJ. Epithelial Plasticity during Liver Injury and Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2020;27:557–573.10.1016/j.stem.2020.08.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8 Raven A, Lu WY, Man TY, Ferreira-Gonzalez S, O'Duibhir E, Dwyer BJ, et al. Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature 2017;547:350–354.10.1038/nature23015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9 Campana L, Esser H, Huch M, Forbes S. Liver regeneration and inflammation: from fundamental science to clinical applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021;22:608–624.10.1038/s41580-021-00373-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10 Li Y, Lu L, Cai X. Liver Regeneration and Cell Transplantation for End-Stage Liver Disease. Biomolecules 2021;11:1907.10.3390/biom11121907Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11 Volarevic V, Nurkovic J, Arsenijevic N, Stojkovic M. Concise review: Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of acute liver failure and cirrhosis. Stem Cells 2014;32:2818–2823.10.1002/stem.1818Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12 Di-Iacovo N, Pieroni S, Piobbico D, Castelli M, Scopetti D, Ferracchiato S, et al. Liver Regeneration and Immunity: A Tale to Tell. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:1176.10.3390/ijms24021176Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13 Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature 2003;425:968–973.10.1038/nature02069Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Nussler A, Konig S, Ott M, Sokal E, Christ B, Thasler W, et al. Present status and perspectives of cell-based therapies for liver diseases. J Hepatol 2006;45:144–159.10.1016/j.jhep.2006.04.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Roord ST, de Jager W, Boon L, Wulffraat N, Martens A, Prakken B, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation in autoimmune arthritis restores immune homeostasis through CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood 2008;111:5233–5241.10.1182/blood-2007-12-128488Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16 Shi Y, Wang Y, Li Q, Liu K, Hou J, Shao C, et al. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem and stromal cells in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018;14:493–507.10.1038/s41581-018-0023-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17 Khan S, Khan RS, Newsome PN. Cell Therapy for Liver Disease: From Promise to Reality. Semin Liver Dis 2020;40:411–426.10.1055/s-0040-1717096Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18 Bianco P, Riminucci M, Gronthos S, Robey PG. Bone marrow stromal stem cells: nature, biology, and potential applications. Stem Cells 2001;19:180–192.10.1634/stemcells.19-3-180Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19 Vainshtein JM, Kabarriti R, Mehta KJ, Roy-Chowdhury J, Guha C. Bone marrow-derived stromal cell therapy in cirrhosis: clinical evidence, cellular mechanisms, and implications for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;89:786–803.10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.02.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20 Bihari C, Anand L, Rooge S, Kumar D, Saxena P, Shubham S, et al. Bone marrow stem cells and their niche components are adversely affected in advanced cirrhosis of the liver. Hepatology 2016;64:1273–1288.10.1002/hep.28754Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21 Terai S, Takami T, Yamamoto N, Fujisawa K, Ishikawa T, Urata Y, et al. Status and prospects of liver cirrhosis treatment by using bone marrow-derived cells and mesenchymal cells. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2014;20:206–210.10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0527Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22 Bai YQ, Yang YX, Yang YG, Ding SZ, Jin FL, Cao MB, et al. Outcomes of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in decompensated liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:8660–8666.10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8660Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Lyra AC, Soares MB, da Silva LF, Fortes MF, Silva AG, Mota AC, et al. Feasibility and safety of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:1067–1073.10.3748/wjg.v13.i7.1067Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24 Austin PC. The relative ability of different propensity score methods to balance measured covariates between treated and untreated subjects in observational studies. Med Decis Making 2009;29:661–677.10.1177/0272989X09341755Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25 Kim WR, Mannalithara A, Heimbach JK, Kamath PS, Asrani SK, Biggins SW, et al. MELD 3.0: The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Updated for the Modern Era. Gastroenterology 2021;161:1887–1895.10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26 European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2010;53:397–417.10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Heathcote EJ. Management of primary biliary cirrhosis. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines. Hepatology 2000;31:1005–1013.10.1053/he.2000.5984Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28 Schacher FC, Martins Pezzi da Silva A, Silla LMDR, Álvares-da-Silva MR. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Grades 2 and 3: A Phase I-II Randomized Clinical Trial. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;2021:3662776.10.1155/2021/3662776Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29 Kim JK, Kim SJ, Kim Y, Chung YE, Park YN, Kim HO, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients After Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Infusion for Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis. Cell Transplant 2017;26:1059–1066.10.3727/096368917X694778Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30 Baldo G, Giugliani R, Uribe C, Belardinelli MC, Duarte ME, Meurer L, et al. Bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation improves survival and induces hepatocyte proliferation in rats after CCl(4) acute liver damage. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:3384–3392.10.1007/s10620-010-1195-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31 Belardinelli MC, Pereira F, Baldo G, Vicente Tavares AM, Kieling CO, da Silveira TR, et al. Adult derived mononuclear bone marrow cells improve survival in a model of acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in rats. Toxicology 2008;247:1–5.10.1016/j.tox.2008.01.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Salama H, Zekri AR, Bahnassy AA, Medhat E, Halim HA, Ahmed OS, et al. Autologous CD34+ and CD133+ stem cells transplantation in patients with end stage liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:5297–5305.10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5297Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33 Mohamadnejad M, Alimoghaddam K, Bagheri M, Ashrafi M, Abdollahzadeh L, Akhlaghpoor S, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int 2013;33:1490–1496.10.1111/liv.12228Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34 Spahr L, Chalandon Y, Terraz S, Kindler V, Rubbia-Brandt L, Frossard JL, et al. Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with decompensated alcoholic liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e53719.10.1371/journal.pone.0053719Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35 Salama H, Zekri AR, Medhat E, Al Alim SA, Ahmed OS, Bahnassy AA, et al. Peripheral vein infusion of autologous mesenchymal stem cells in Egyptian HCV-positive patients with end-stage liver disease. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014;5:70.10.1186/scrt459Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36 Xu L, Gong Y, Wang B, Shi K, Hou Y, Wang L, et al. Randomized trial of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for hepatitis B virus cirrhosis: regulation of Treg/Th17 cells. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1620–1628.10.1111/jgh.12653Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37 Mohamadnejad M, Vosough M, Moossavi S, Nikfam S, Mardpour S, Akhlaghpoor S, et al. Intraportal Infusion of Bone Marrow Mononuclear or CD 133+ Cells in Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Stem Cells Transl Med 2016;5:87–94.10.5966/sctm.2015-0004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38 Suk KT, Yoon JH, Kim MY, Kim CW, Kim JK, Park H, et al. Transplantation with autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for alcoholic cirrhosis: Phase 2 trial. Hepatology 2016;64:2185–2197.10.1002/hep.28693Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39 Zhang D. A clinical study of bone mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of hepatic fibrosis induced by hepatolenticular degeneration. Genet Mol Res 2017;16:10.10.4238/gmr16019352Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40 Peng L, Xie DY, Lin BL, Liu J, Zhu HP, Xie C, et al. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in liver failure patients caused by hepatitis B: short-term and long-term outcomes. Hepatology 2011;54:820–828.10.1002/hep.24434Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41 Lin BL, Chen JF, Qiu WH, Wang KW, Xie DY, Chen XY, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 2017;66:209–219.10.1002/hep.29189Search in Google Scholar

42 Kantarcıoğlu M, Demirci H, Avcu F, Karslıoğlu Y, Babayiğit MA, Karaman B, et al. Efficacy of autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with liver cirrhosis. Turk J Gastroenterol 2015;26:244–250.10.5152/tjg.2015.0074Search in Google Scholar

43 Park CH, Bae SH, Kim HY, Kim JK, Jung ES, Chun HJ, et al. A pilot study of autologous CD34-depleted bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation via the hepatic artery in five patients with liver failure. Cytotherapy 2013;15:1571–1579.10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.05.013Search in Google Scholar

44 Pai M, Zacharoulis D, Milicevic MN, Helmy S, Jiao LR, Levicar N, et al. Autologous infusion of expanded mobilized adult bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells into patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1952–1958.10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01993.xSearch in Google Scholar

45 de Haan G, Lazare SS. Aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 2018;131:479–487.10.1182/blood-2017-06-746412Search in Google Scholar

46 Oakley EJ, Van Zant G. Age-related changes in niche cells influence hematopoietic stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell 2010;6:93–94.10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.008Search in Google Scholar

47 Nishi N, Oya H, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Miyanaka H, Wada F. Changes in gene expression of growth factors and their receptors during castration-induced involution and androgen-induced regrowth of rat prostates. Prostate 1996;28:139–152.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199603)28:3<139::AID-PROS1>3.0.CO;2-ASearch in Google Scholar

48 Tanabe M, Hosono K, Yamashita A, Ito Y, Majima M, Narumiya S, et al. Deletion of TP signaling in macrophages delays liver repair following APAP-induced liver injury by reducing accumulation of reparative macrophage and production of HGF. Inflamm Regen 2024;44:43.10.1186/s41232-024-00356-zSearch in Google Scholar

49 Anand L, Bihari C, Kedarisetty CK, Rooge SB, Kumar D, Shubham S, et al. Early cirrhosis and a preserved bone marrow niche favour regenerative response to growth factors in decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int 2019;39:115–126.10.1111/liv.13923Search in Google Scholar

50 Hora S, Wuestefeld T. Liver Injury and Regeneration: Current Understanding, New Approaches, and Future Perspectives. Cells 2023;12:2129.10.3390/cells12172129Search in Google Scholar

51 Spees JL, Lee RH, Gregory CA. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/ stromal cell function. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016;7:125.10.1186/s13287-016-0363-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52 Terai S, Tsuchiya A. Status of and candidates for cell therapy in liver cirrhosis: overcoming the "point of no return" in advanced liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol 2017;52:129–140.10.1007/s00535-016-1258-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53 Marti U, Burwen SJ, Jones AL. Biological effects of epidermal growth factor, with emphasis on the gastrointestinal tract and liver: an update. Hepatology 1989;9:126–138.10.1002/hep.1840090122Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54 Apte RS, Chen DS, Ferrara N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019;176:1248–1264.10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55 Umemura Y, Ogura H, Matsuura H, Ebihara T, Shimizu K, Shimazu T. Bone marrow-derived mononuclear cell therapy can attenuate systemic inflammation in rat heatstroke. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2018;26:97.10.1186/s13049-018-0566-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56 de Andrade DC, de Carvalho SN, Pinheiro D, Thole AA, Moura AS, de Carvalho L, et al. Bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation improves mitochondrial bioenergetics in the liver of cholestatic rats. Exp Cell Res 2015;336:15–22.10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.05.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57 Lukashyk SP, Tsyrkunov VM, Isaykina YI, Romanova ON, Shymanskiy AT, Aleynikova OV, et al. Mesenchymal Bone Marrow-derived Stem Cells Transplantation in Patients with HCV Related Liver Cirrhosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2014;2:217–221.10.14218/JCTH.2014.00027Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58 Zhou GP, Jiang YZ, Sun LY, Zhu ZJ. Therapeutic effect and safety of stem cell therapy for chronic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020;11:419.10.1186/s13287-020-01935-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59 Zhao L, Chen S, Shi X, Cao H, Li L. A pooled analysis of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for liver disease. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018;9:72.10.1186/s13287-018-0816-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60 Zhu CH, Zhang DH, Zhu CW, Xu J, Guo CL, Wu XG, et al. Adult stem cell transplantation combined with conventional therapy for the treatment of end-stage liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021;12:558.10.1186/s13287-021-02625-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61 Ratajczak MZ, Serwin K, Schneider G. Innate immunity derived factors as external modulators of the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis and their role in stem cell homing and mobilization. Theranostics 2013;3:3–10.10.7150/thno.4621Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62 Jiang Q, Huang K, Lu F, Deng S, Yang Z, Hu S. Modifying strategies for SDF-1/CXCR4 interaction during mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;70:1–10.10.1007/s11748-021-01696-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63 Ullah I, Subbarao RB, Rho GJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells - current trends and future prospective. Biosci Rep 2015;35:e00191.10.1042/BSR20150025Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64 Yin Y, Li X, He XT, Wu RX, Sun HH, Chen FM. Leveraging Stem Cell Homing for Therapeutic Regeneration. J Dent Res 2017;96:601–609.10.1177/0022034517706070Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65 Yu S, Yu S, Liu H, Liao N, Liu X. Enhancing mesenchymal stem cell survival and homing capability to improve cell engraftment efficacy for liver diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023;14:235.10.1186/s13287-023-03476-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

66 Jin SZ, Meng XW, Sun X, Han MZ, Liu BR, Wang XH, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances bone marrow mononuclear cell homing to the liver in a mouse model of acute hepatic injury. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:2805–2813.10.1007/s10620-009-1117-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67 Yannaki E, Athanasiou E, Xagorari A, Constantinou V, Batsis I, Kaloyannidis P, et al. G-CSF-primed hematopoietic stem cells or G-CSF per se accelerate recovery and improve survival after liver injury, predominantly by promoting endogenous repair programs. Exp Hematol 2005;33:108–119.10.1016/j.exphem.2004.09.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 Mengfan Ruan, Yuhang Yin, Wen Ning, Beilei Zhang, Hao Lin, Huiying Yu, Xiaoxi Wang, Deli Zou, Xiaodong Shao, Jiang Chen, Hongyu Li, Xiaozhong Guo, Xingshun Qi, published by De Gruyter on behalf of Scholar Media Publishing

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Prehospital neuroprotective intervention: A critical imperative evidenced by the FRONTIER trial outcomes

- Artificial intelligence in rheumatology: A transformative perspective

- Dialysis adequacy revisited: Kt/V's blind spot for phosphorus and iodine

- Review Article

- The plakin family: Potential therapeutic targets for digestive system tumors

- Original Article

- Lnc5q21.2, a novel long intergenic RNA, sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to ATR inhibitor by activating Wnt pathway

- Effect of bone marrow mononuclear cells therapy on long-term survival of patients with liver cirrhosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using propensity score matching

- Associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and gastric cancer and precancerous lesions in men: A 11.8-year prospective study

- Comprehensive investigation of cuproptosis-related genes in clinical features, biological characteristics, and immune microenvironment in B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Protocol

- A multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial of intravenous thrombolysis with tenecteplase for acute non-large vessel occlusion in extended time window (OPTION): Rationale and design

- Rapid Communication

- Association between anemia and 1-year recurrence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Prehospital neuroprotective intervention: A critical imperative evidenced by the FRONTIER trial outcomes

- Artificial intelligence in rheumatology: A transformative perspective

- Dialysis adequacy revisited: Kt/V's blind spot for phosphorus and iodine

- Review Article

- The plakin family: Potential therapeutic targets for digestive system tumors

- Original Article

- Lnc5q21.2, a novel long intergenic RNA, sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to ATR inhibitor by activating Wnt pathway

- Effect of bone marrow mononuclear cells therapy on long-term survival of patients with liver cirrhosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using propensity score matching

- Associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and gastric cancer and precancerous lesions in men: A 11.8-year prospective study

- Comprehensive investigation of cuproptosis-related genes in clinical features, biological characteristics, and immune microenvironment in B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Protocol

- A multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial of intravenous thrombolysis with tenecteplase for acute non-large vessel occlusion in extended time window (OPTION): Rationale and design

- Rapid Communication

- Association between anemia and 1-year recurrence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation