Associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and gastric cancer and precancerous lesions in men: A 11.8-year prospective study

-

Jiayue Li

and Shaoming Wang

Abstract

Background and objectives

Sex steroid hormones have been hypothesized to be associated with the risk of gastric cancer (GC); however, it has not been widely validated in prospective studies. We aimed to investigate the associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and the risk of gastric cancer and precancerous lesions in a prospective cohort of Chinese men.

Methods

Using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and electrochemical luminescence immunoassay, we examined 20 sex steroid hormone metabolites and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in serum from 470 eligible men, including high-grade lesions or GC (n = 32), intestinal metaplasia (IM, n = 146), and 1:2 matched normal participants (n = 292) from 2007 to 2012. IM and normal participants were further followed up until December 2021, during which 32 new GC cases were identified with a median follow-up of 11.8 years. Associations between baseline sex steroid hormone metabolites and IM, high-grade lesions and gastric cancer were assessed using logistic regression, and associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and incident GC risk were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression in the prospective analysis.

Results

In the cross-sectional analysis, androstenedione levels were potentially associated with IM risk and significantly associated with high-grade lesions or GC risk (ORcontinuous = 2.45, 95% CI: 1.01–5.95). Higher concentrations of 17α-hydroxypregnenolone (ORcontinuous = 2.35, 95% CI: 1.13–4.88), progesterone (ORcontinuous = 2.68, 95% CI: 1.09–6.61), and estrone (ORcontinuous = 5.36, 95% CI: 1.28–22.52) were also associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC. Furthermore, significant positive associations between GC risk and serum levels of SHBG (HRcontinuous = 2.57, 95% CI: 1.04–6.36), epitestosterone (HRcontinuous = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.07–4.15) and pregnenolone (HRcontinuous = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.03–1.63) were identified in the follow-up study focusing on participants diagnosed as normal or IM. Notably, the subgroup analyses stratified by H. pylori status revealed similar associations between androstenedione, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, progesterone, estrone, SHBG, pregnenolone, and GC risk.

Conclusions

Several sex hormone metabolites were significantly associated with gastric cancer and its precancerous lesions, indicating a role for sex hormones in gastric carcinogenesis and potentially providing novel biomarkers for the identification of high-risk populations and risk prediction for GC.

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common malignancy globally, exhibiting striking geographic and ethnic disparities in its distribution. East Asian populations, particularly in China, bear the highest burden, with China alone accounting for 37.0% of global GC cases and 39.5% of GC-related deaths.[1, 2, 3] This epidemiological pattern correlates strongly with Helicobacter pylori infection rates, a key driver of gastric carcinogenesis through chronic inflammatory processes. In China, the H. pylori prevalence reaches 49.6%,[4] sustaining pathological progression from intestinal metaplasia (IM, a critical precancerous lesion) through dysplasia to invasive adenocarcinoma.[5] Regional differences in the natural history of IM are also notable: while the annual progression rate from IM to GC is approximately 0.25% in Western Europe, it reaches 10% in East Asian populations.[6,7] Reflecting this risk, China’s 2024 Guidelines for GC Screening and Early Diagnosis/Treatment recommend stratified endoscopic surveillance (at 1- to 3-year intervals) based on IM severity. These guidelines highlight the urgent need for early identification of IM in high-risk populations.

Another defining feature of GC burden is its marked sex disparity. In China, the age-standardized incidence rate of GC in 2022 was more than twice as high in men (19.47 per 100, 000) as in women (8.29 per 100, 000).[8] Traditionally, this disparity has been attributed to differences in exposure to established risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.[9,10] However, accumulating evidence suggests that these factors alone cannot fully explain the observed sex differences.[11,12] Sex hormones have been implicated in gastric carcinogenesis. This includes: (a) associations between reproductive factors and the risk of GC from results of epidemiological surveys;[13,14] (b) associations between hormone replacement therapy and a lower GC risk,[15] as well as anti-estrogen therapy and a higher GC risk in women;[16] and (c) association between androgen deprivation therapy and a lower GC risk in men with prostate cancer.[17] Experimental studies have also provided evidence to support this hypothesis, including the involvement of sex steroid hormones in the inflammatory process,[18,19] and the expression of sex hormone receptors in GC tissue.[20] In addition, a Mendelian randomization analysis using public Genome-Wide Association Study statistics showed a role of testosterone in the development of GC.[21]

Given this context, a growing number of studies have begun to explore associations between circulating sex hormone metabolites and GC risk. For example, a case-control study in a Mexican population found that higher concentrations of circulating dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) were associated with a lower risk of GC,[22] while a prospective study in the UK reported that elevated sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased GC risk in men.[23] Conversely, a nested case-control study conducted in the Chinese population reported no overall association between androgens and estrogens and GC risk.[24] These inconsistencies may be attributed to differences in study design (e.g., case-control[22] vs. prospective [23,24] study), population background (e.g., European and American [22,23] vs. East Asian[24]), and the sensitivity of laboratory methodologies (e.g., gas chromatography-mass spectrometry;[22] chemiluminescent immunoassay;[23] radioimmunoassays [24]). Notably, most existing research has been conducted in Western populations and has focused primarily on GC, with limited investigation into East Asian populations or earlier precancerous stages such as IM. To address this gap, our study aims to evaluate the associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and the risk of both GC and precancerous lesions, including IM, in a high-risk East Asian population.

We conducted this research in Linzhou, a rural county in China’s Henan Province, located in the Taihang Mountain area, which has among the highest GC incidence rates nationwide (140.5 per 100, 000 for cardia GC and 37.4 per 100, 000 for non-cardia GC), with local H. pylori prevalence ranging from 35.51% to 46.80%.[4,25,26] A male screening cohort has been established in this region, enabling us to conduct a prospective study to investigate the role of serum sex steroid hormones in gastric carcinogenesis. The findings from this study are expected to provide novel biomarkers for the early detection of high-risk individuals and inform precision screening strategies for GC prevention in China and other high-burden regions.

Materials and methods

Selection and description of participants

A population-based upper gastrointestinal cancer screening cohort was established from 2007 to 2012 in Linzhou, China. Given the substantial differences in sex hormone levels between men and women, and the fact that women experience significant hormonal fluctuations before and after menopause while men’s hormone levels decline gradually with age and are unaffected by reproductive cycles, we selected men as study participants. This approach ensures hormonal stability and is consistent with the design of previous related studies. After a baseline questionnaire interview and physical examination, a total of 558 men were enrolled and 10 mL of fasting blood was collected from each participant who had fasted for at least 12 h prior to the physical examination. Serum samples were immediately separated, aliquoted, and stored frozen at -70 ℃ until they were prepared for the laboratory analysis.

The endoscopic examination and biopsy procedures were described in detail in a previous study.[27] Specifically, the participants received a local anesthetic (5 mL of 1% lidocaine solution) orally 5 min before endoscope insertion, followed by a complete visual examination of the esophagus and stomach. Then, the stomach was sprayed with 0.2% indigo carmine, which stains the gastric fundic gland mucosa light red and imparts dull yellow to the pyloric gland mucosa. In areas of abnormal gastric mucosa, the dye demonstrates abnormal deposition, resulting in accentuated staining. Next, all areas with accentuated staining > 5 mm in diameter were biopsied, with the number of specimens collected (range 1–3) depending on lesion dimensions (5–19 mm, 1 biopsy; 20–39 mm, 2 biopsies; and ≥40 mm, 3 biopsies). Biopsy specimens underwent standard processing including 10% buffered formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, sectioning at 5-μm, and hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. All sides were independently evaluated by two well-trained pathologists, with discordant cases reviewed jointly to reach diagnostic consensus. Finally, the histological criteria strictly adhered to the 2020 edition of Chinese Technical Guidelines for Screening, Early Diagnosis, and Treatment of Upper Gastrointestinal Cancers.[28]

We excluded men who were diagnosed as severe atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma of the esophagus at baseline (n = 53) (Figure 1). Among the 505 eligible men, there were 32 participants diagnosed with GC (n = 19) or high-grade lesions (n = 13), 146 diagnosed with IM, and 317 normal participants. We randomly matched the IM cases with normal participants by age and village with a ratio of 1:2, and finally included 32 high-grade lesions and GC cases, 146 IM cases, and 292 normal participants in the cross-sectional analytical dataset (n = 470). From 2007 to 2021, the village health workers checked vital status and the occurrence of incident cancers and ascertained causes of deaths for all participants by monthly home visits, supplemented by quarterly crosschecks of the data in the Linzhou Cancer and Death Registries. New GC cases and all causes of death were reviewed by a panel of professional experts from the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences in Beijing, China. Diagnostic materials used in these expert reviews included medical records, pathology and cytology slides, biochemical results, X-rays, ultrasound, endoscopy, and surgical reports. The International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Revision code C16.0 was used to define CGC, and NCGC was defined with topography code C16.1–C16.9.[29] Primary causes of death were classified by the International Classification of Diseases-10.[30] By December 2021, a total of 32 new GC cases were diagnosed in the prospective analytical dataset (n = 438, including 146 IM and 292 normal participants).

Flowchart of the study for diagnostic analysis and prospective analysis. IM, intestinal metaplasia; Gastric cancer includes non-cardia gastric cancer and cardia gastric cancer.

Data collection

All participants underwent a physical examination at local hospitals and completed a standardized questionnaire according to the national upper gastrointestinal cancer screening guideline.[29] The questionnaire included items on demographics (age, sex and residence location), height, weight, smoking status (regular cigarette or pipe use for at least 6 months), alcohol consumption (any alcohol consumption in the past 12 months), history of upper gastrointestinal disease (i.e., ulcer, esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and hepatitis), and family history of cancer (at least one first-degree relative with cancer).

Laboratory analysis

H. pylori infection was measured by immunoblot assay at the laboratory of Linzhou Cancer Hospital. SHBG was tested with electrochemical luminescence immunoassay at the laboratory of the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Sex steroid hormone metabolites were assessed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system at the Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine Laboratory of Dalian Medical University. A total of 20 sex steroid hormone metabolites were quantified, including testosterone, 16 α-hydroxytestosterone, androstenedione, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, progesterone, estrone, epitestosterone, DHEA, pregnenolone, dihydrotestosterone, etiocholanolone, 17-epiestriol, estradiol, 2-methoxyestrone, 2-methoxyestradiol, 16-epiestriol, androsterone, 11-oxoetiocholanolone, and 6β-hydroxytestosterone. Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by evenly mixing aliquots of randomly assigned samples and were inserted into the analytical sequence. A total of 35 QC samples were evenly distributed on each solid phase extraction plate and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The merits of the analytical performance, including reproducibility, i.e., coefficients of variance (CVs) of the concentration determinations in these QC samples, and sensitivity of the LC-MS/MS method (limits of detection (LODs), limits of quantification (LOQs)), were reported in the Supplementary Materials. In these QC samples, CVs were less than 46% (range = 1.14%–45.98%), LODs were less than 5 μg/L (range = 0.25–5 μg/L), and LOQs were less than 5 μg/L (range = 0.25–5 μg/L).

Statistics

Baseline characteristics and the serum sex steroid hormone metabolites levels of participants were presented as median or percentage between normal and case groups. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test and chi-squared test were used to compare the statistical differences between groups for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. As the continuous sex hormone values were right-skewed, these values were logarithmically transformed to follow a normal distribution. In addition, sex steroid hormone metabolites were categorized into quartiles, based on the distributions among the normal participants at baseline. Tests for linear trend were performed on the basis of the quartiles.

In the cross-sectional analysis, conditional logistic regression, based on the age-matched IM-normal pairs, was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and IM risk. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate ORs and 95% CIs for associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and high-grade lesions or GC risk. In the prospective analysis, Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and GC risk. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld’ residuals and Kolmogorov-type supremum analysis, with evidence of equiproportionality being detected. Follow-up time in years was used as the underlying time metric and was calculated from baseline to the date of diagnosis of GC, the date of death, or the end of the follow-up period (December 31, 2021), whichever occurred first. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of upper gastrointestinal disease, family history of cancer, and H. pylori CagA infection. Additionally, participants were stratified by the H. pylori CagA infection status for the sensitivity analysis to test the effects of H. pylori infection on associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and GC and precancerous lesions.

In addition to individual sex hormones, we also calculated the following parameters using the aforementioned analytical approaches: parent estrogens (the sum of estrone and estradiol), testosterone: parent estrogens ratio, testosterone: estradiol ratio, and androstenedione: estrone ratio. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, and all P values were two-tailed. Analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics and levels of serum sex hormone metabolites

Demographic characteristics, distributions of risk factors, and levels of serum sex hormone metabolites for participants with different baseline pathological diagnoses are summarized in Table 1. A total of 470 participants were enrolled in the cross-sectional analysis. Compared to normal participants, those with IM were more likely to be infected with H. pylori (65.1% vs. 52.1%, P = 0.01). High-grade lesions or GC patients were older than normal participants (73.5 years vs. 68.0 years, P < 0.01), and generally exhibited higher median concentrations of sex hormones compared to both IM patients and normal participants.

Baseline characteristics and levels of serum sex hormone metabolites in subjects with different pathological diagnoses

| Normal participants (N = 292) | Intestinal metaplasia participants (N = 146) | P value | High-grade lesions or gastric cancer participants (N = 32) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 68.0 [62.0, 73.0] | 68.0 [62.3, 74.0] | 0.38 | 73.5 [70.0, 78.3] | <0.01 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 22.5 [20.8, 24.4] | 22.2 [20.7, 24.2] | 0.18 | 21.7 [20.5, 23.5] | 0.16 |

| Smoking (n, %) | |||||

| No | 156 (53.4%) | 84 (57.5%) | 0.48 | 12 (37.5%) | 0.13 |

| Yes | 136 (46.6%) | 62 (42.5%) | 20 (62.5%) | ||

| Drinking (n, %) | |||||

| No | 245 (83.9%) | 126 (86.3%) | 0.61 | 26 (81.3%) | 0.89 |

| Yes | 47 (16.1%) | 20 (13.7%) | 6 (18.8%) | ||

| History of upper gastrointestinal disease (n, %) | |||||

| No | 240 (82.2%) | 130 (89.0%) | 0.08 | 28 (87.5%) | 0.61 |

| Yes | 52 (17.8%) | 16 (11.0%) | 4 (12.5%) | ||

| Family history of cancer (n, %) | |||||

| No | 156 (53.4%) | 77 (52.7%) | 0.97 | 20 (62.5%) | 0.43 |

| Yes | 136 (46.6%) | 69 (47.3%) | 12 (37.5%) | ||

| H.pylori CagA* (n, %) | |||||

| No | 140 (47.9%) | 51 (34.9%) | 0.01 | 13 (40.6%) | 0.55 |

| Yes | 152 (52.1%) | 95 (65.1%) | 19 (59.4%) | ||

| Sex hormone binding globulin (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 69.1 [51.6, 94.5] | 73.4 [52.1, 102.0] | 0.21 | 87.8 [66.9, 107.0] | 0.01 |

| Testosterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 6340 [5100, 7800] | 6710 [5140, 8120] | 0.17 | 7340 [5270, 9130] | 0.13 |

| 16α-Hydroxytestosterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 1460 [1110, 1870] | 1520 [1110, 2010] | 0.40 | 1430 [1120, 1750] | 0.76 |

| Androstenedione (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 1250 [946, 1610] | 1230 [1020, 1590] | 0.52 | 1710 [1120, 2380] | <0.01 |

| 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 994 [784, 1250] | 958 [744, 1230] | 0.26 | 1210 [929, 1550] | 0.04 |

| 17α-Hydroxypregnenolone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 3490 [2440, 5040] | 3320 [2510, 4560] | 0.49 | 4670 [2750, 6590] | 0.11 |

| Progesterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 59.2 [47.4, 73.6] | 56.6 [45.6, 68.7] | 0.16 | 69.7 [49.1, 99.6] | 0.07 |

| Estrone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 63.5 [53.6, 75.2] | 64.5 [54.4, 78.6] | 0.28 | 79.5 [61.1, 93.1] | <0.01 |

| Epitestosterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 109.0 [68.7, 152.0] | 109.0 [75.3, 161.0] | 0.45 | 149.0 [91.2, 237.0] | 0.02 |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 1450 [992, 2130] | 1430 [1000, 1960] | 0.80 | 1370 [1040, 1920] | 0.70 |

| Pregnenolone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 519 [161, 788] | 531 [185, 794] | 0.83 | 665 [125, 1050] | 0.28 |

| Dihydrotestosterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 559 [443, 760] | 590 [450, 799] | 0.38 | 618 [476, 786] | 0.34 |

| Etiocholanolone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 201 [152, 264] | 214 [158, 282] | 0.33 | 215 [159, 257] | 0.97 |

| 17-Epiestriol (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 14.9 [11.5, 19.3] | 14.1 [10.6, 18.6] | 0.18 | 13.0 [10.3, 18.3] | 0.17 |

| Estradiol (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 36.9 [25.3, 47.1] | 39.5 [25.5, 52.5] | 0.26 | 36.1 [31.2, 43.0] | 0.89 |

| 2-Methoxyestrone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 18.0 [13.6, 23.7] | 17.7 [13.5, 23.3] | 0.84 | 20.1 [15.4, 31.5] | 0.16 |

| 2-Methoxyestradiol (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 12.7 [9.2, 19.2] | 12.2 [9.2, 19.2] | 0.88 | 12.5 [8.2, 20.1] | 0.97 |

| 16-Epiestriol (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 37.1 [21.0, 54.6] | 33.1 [17.1, 48.3] | 0.14 | 31.5 [16.3, 54.1] | 0.40 |

| Androsterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 356 [266, 462] | 364 [288, 493] | 0.29 | 343 [284, 442] | 0.89 |

| 11-Oxoetiocholanolone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 58.2 [26.2, 142.0] | 48.4 [23.8, 120.0] | 0.25 | 76.8 [33.5, 147.0] | 0.35 |

| 6β-Hydroxytestosterone (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 65.6 [33.8, 136.0] | 70.5 [39.0, 150.0] | 0.26 | 86.6 [29.2, 169.0] | 0.71 |

| Parent estrogens (ng/L) | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 102.0 [82.4, 119.0] | 105.0 [85.3, 125.0] | 0.22 | 112.0 [96.0, 136.0] | 0.02 |

| Testosterone: parent estrogens ratio | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 62.2 [50.8, 81.5] | 65.7 [48.5, 87.3] | 0.55 | 65.6 [49.3, 84.7] | 0.84 |

| Testosterone: estradiol ratio | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 176 [132, 250] | 179 [122, 262] | 0.83 | 194 [154, 272] | 0.31 |

| Androstenedione: estrone ratio | |||||

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 19.1 [15.5, 24.6] | 20.0 [15.9, 25.9] | 0.49 | 22.4 [17.3, 29.8] | 0.10 |

BMI: body mass index. *H.pylori CagA is one of the antibodies against Helicobacter pylori.

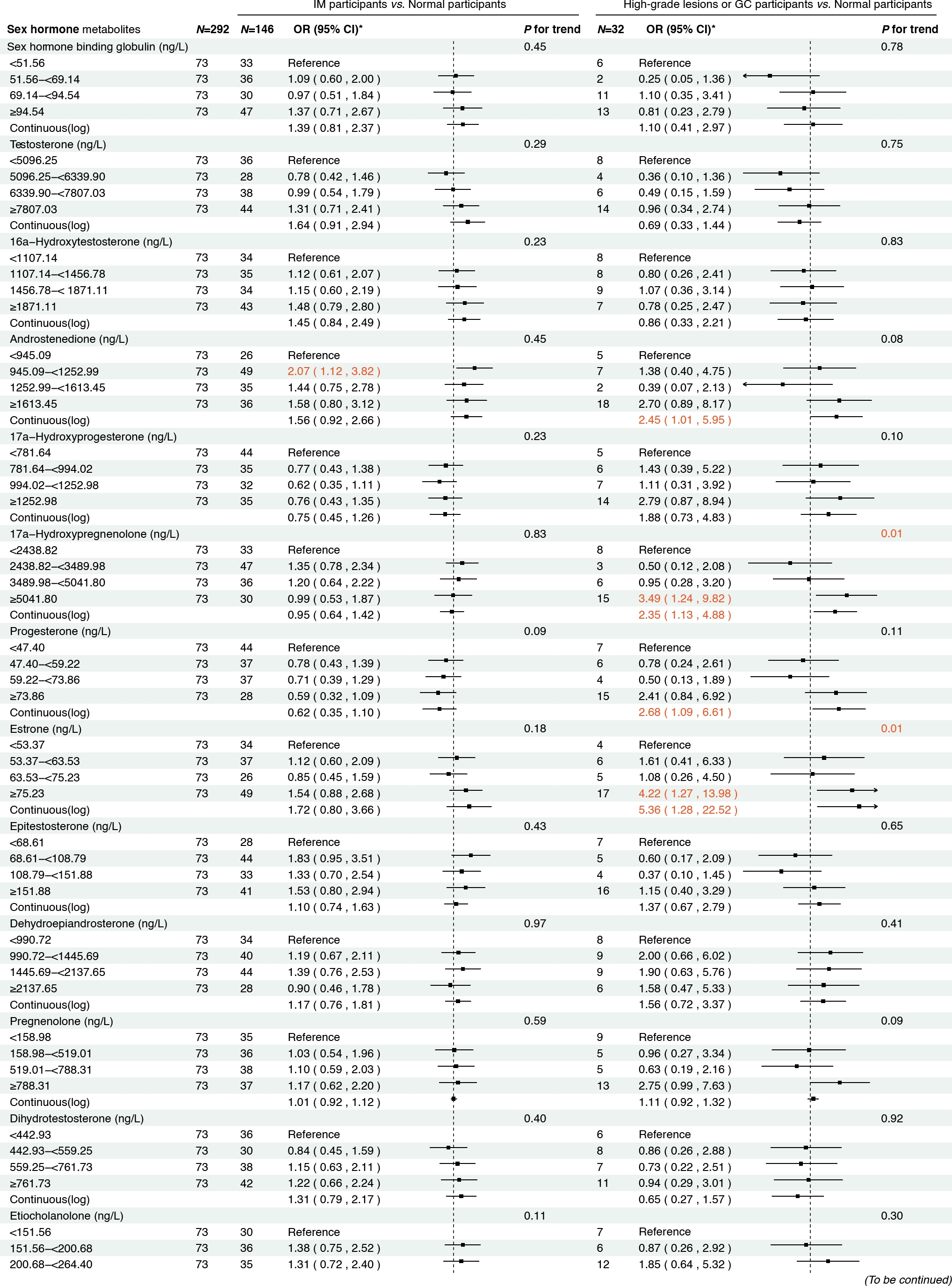

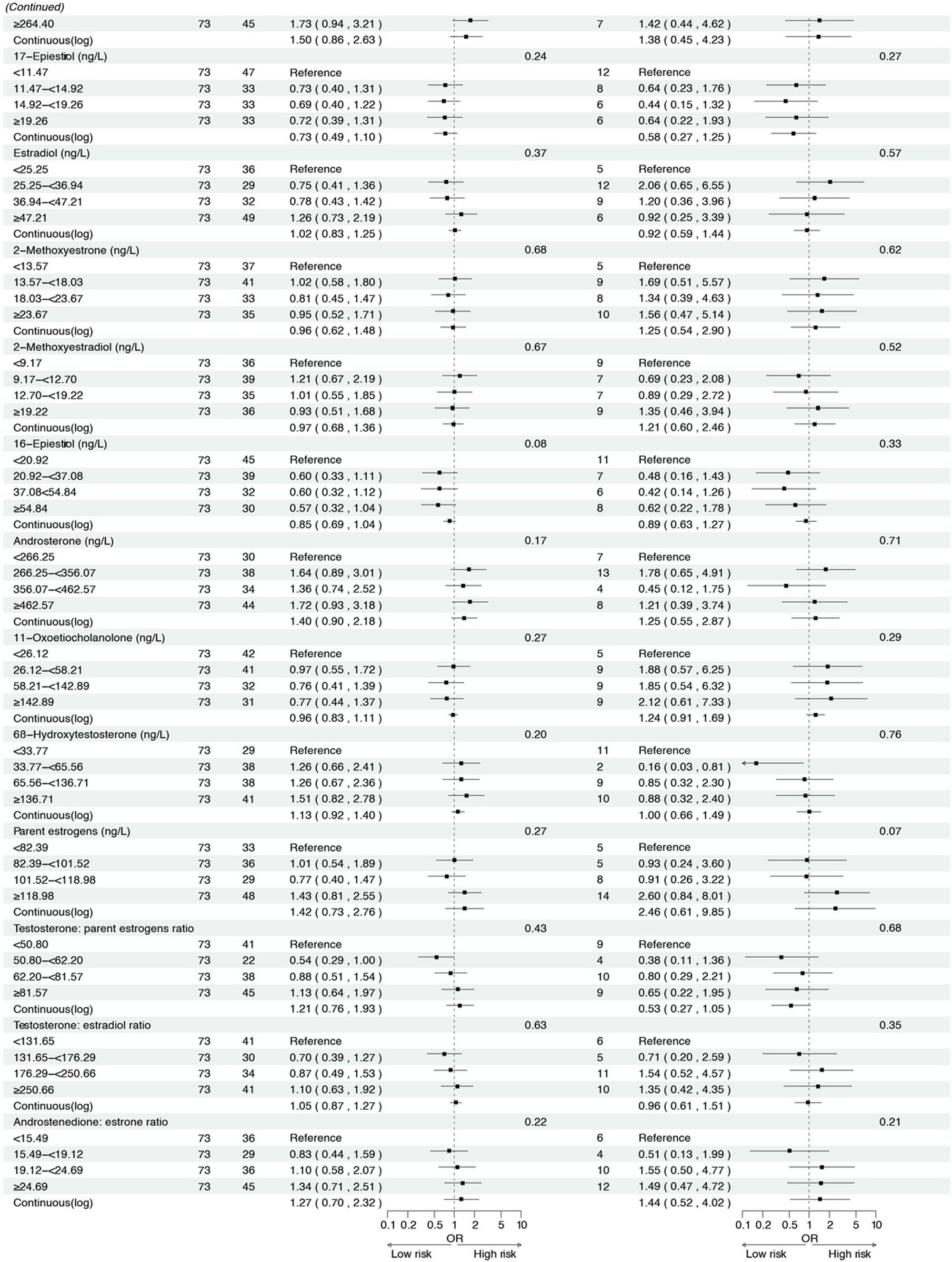

Cross-sectional analysis results

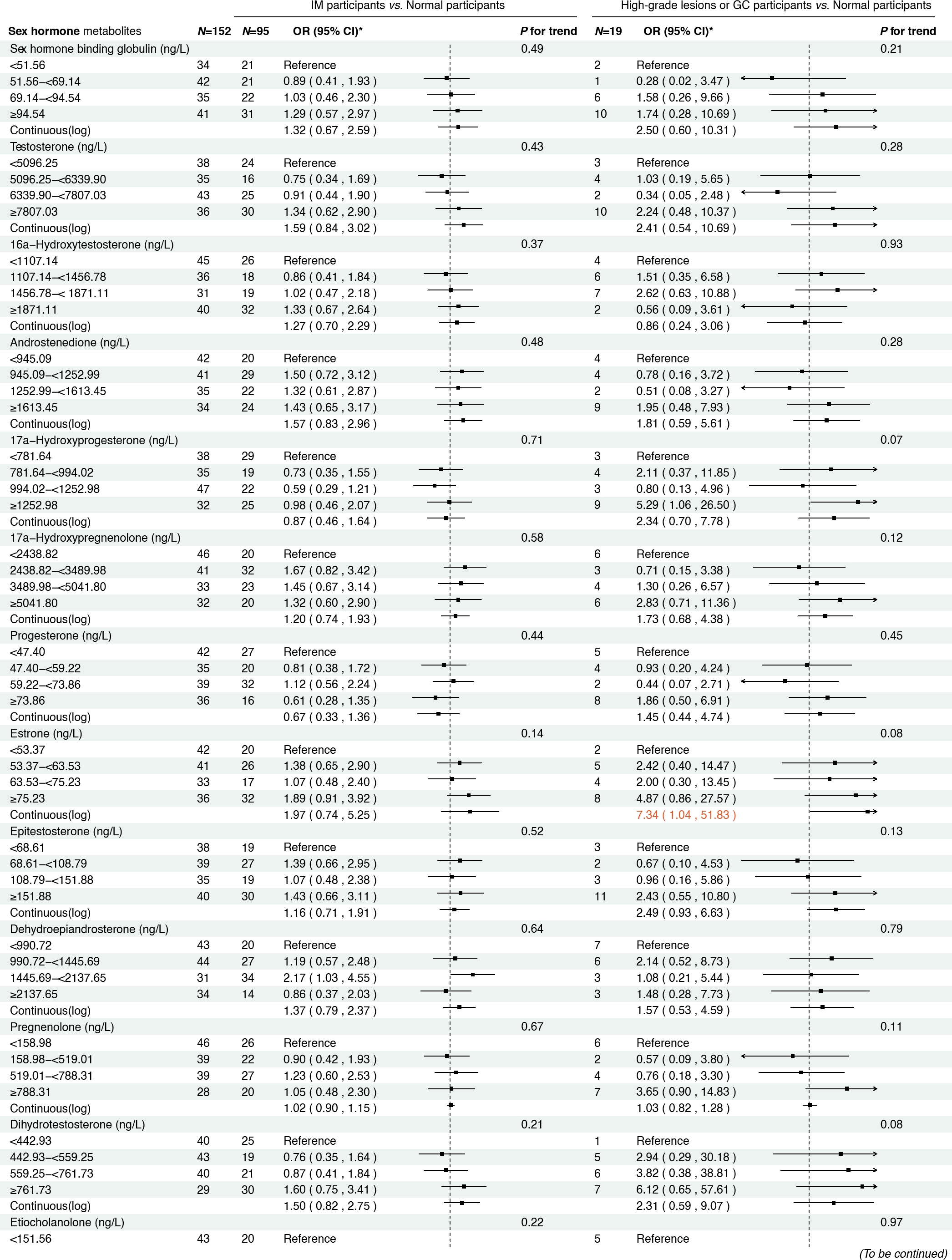

Figure 2 presents the associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and the risk of IM and high-grade lesions or GC in the cross-sectional analysis. We found that higher concentrations of androstenedione were associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC (ORcontinuous= 2.45, 95% CI: 1.01–5.95), and a similar association was observed between androstenedione and IM (ORQ2 vs. Q1 = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.12–3.82). Meanwhile, higher concentrations of 17α-hydroxypregnenolone (ORcontinuous= 2.35, 95% CI: 1.13–4.88) and estrone (ORcontinuous = 5.36, 95% CI: 1.28–22.52) were associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC, with consistent results when analyzing quartiles of 17α-hydroxypregnenolone (ORQ4 vs. Q1 = 3.49, 95% CI: 1.24–9.82, Ptrend = 0.01) and estrone (ORQ4 vs. Q1 = 4.22, 95% CI: 1.27–13.98, P trend = 0.01). Additionally, higher concentrations of progesterone (ORcontinuous = 2.68, 95% CI: 1.09–6.61) were also associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC in participants.

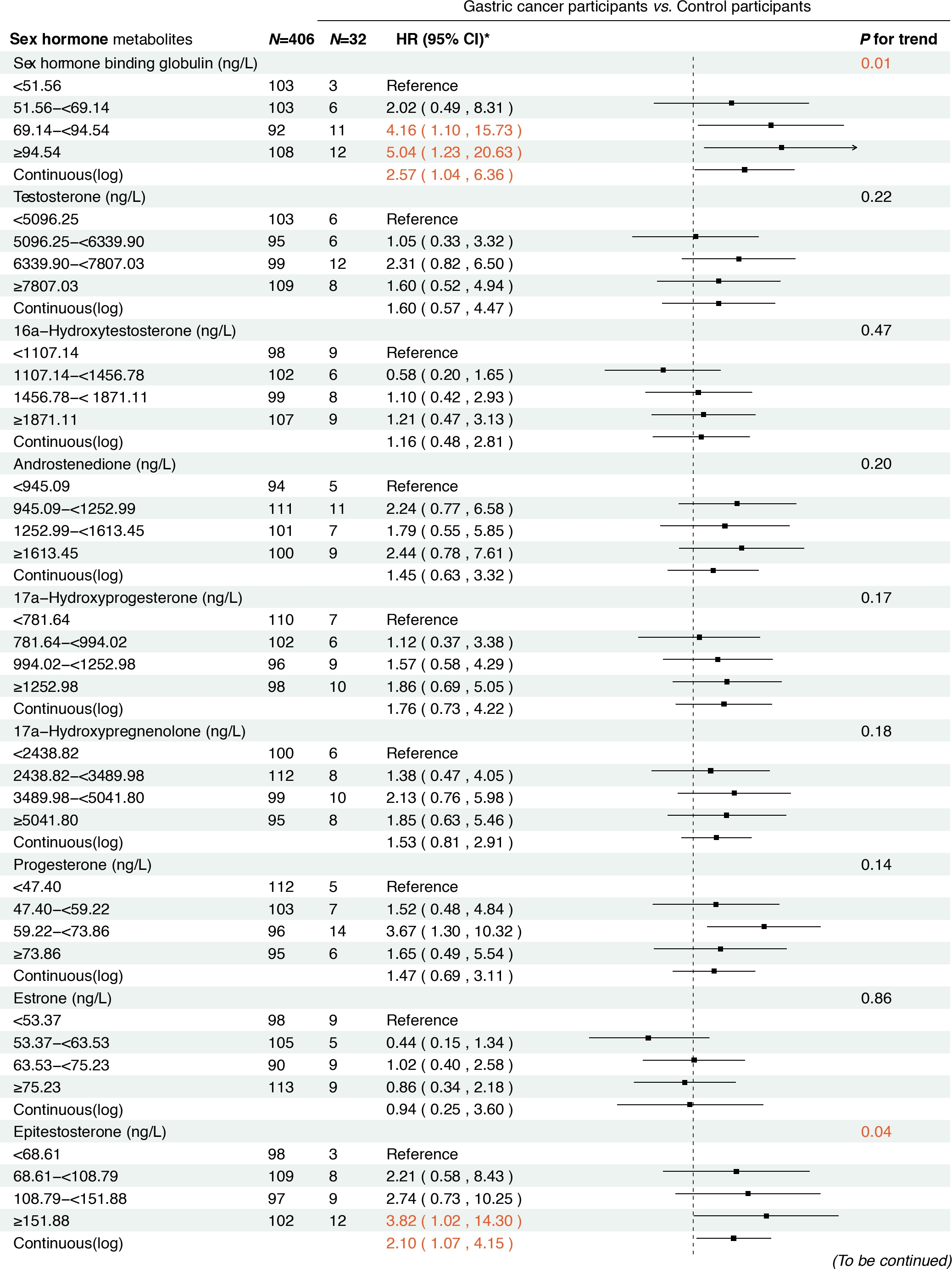

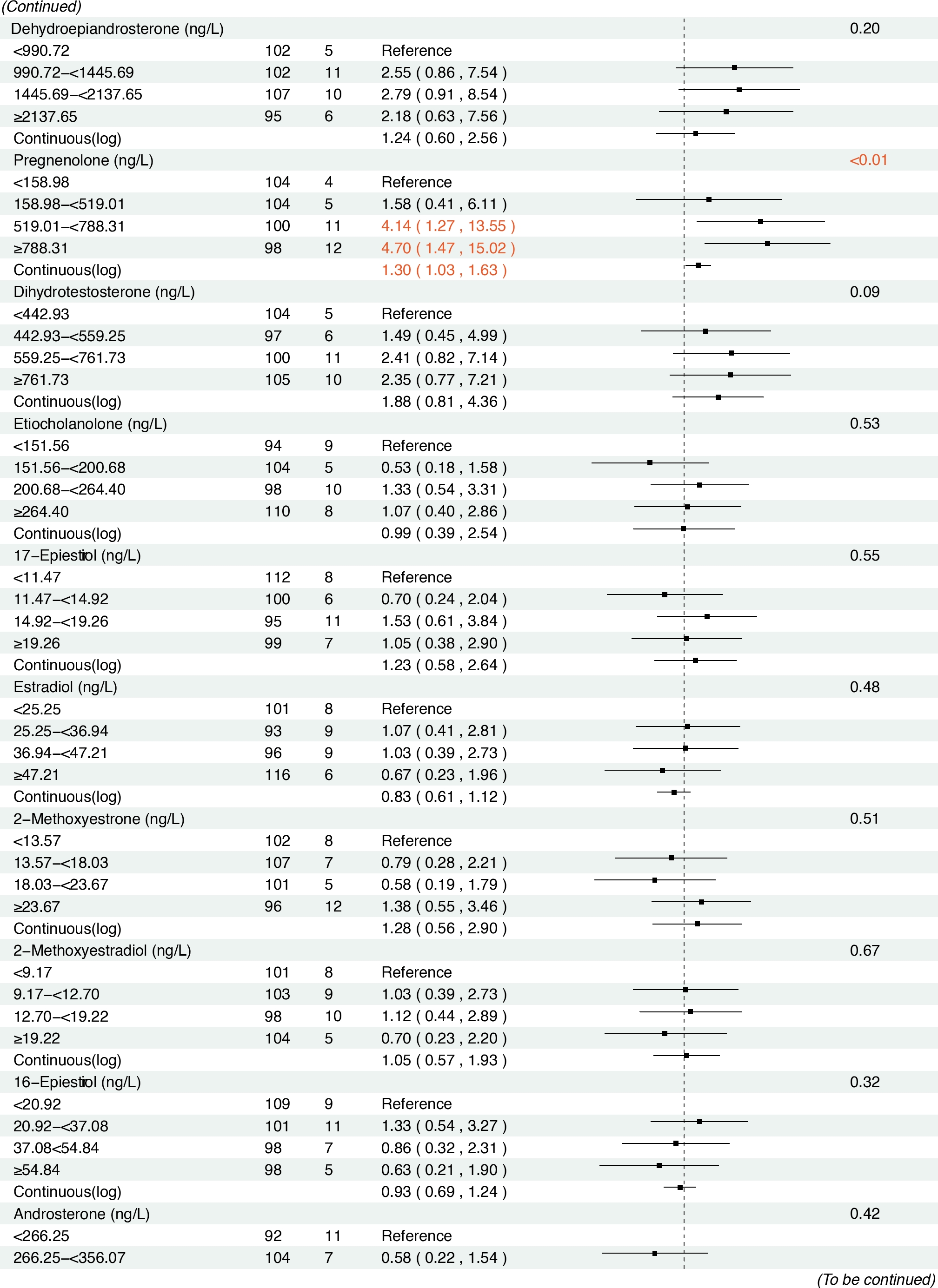

Prospective analysis results

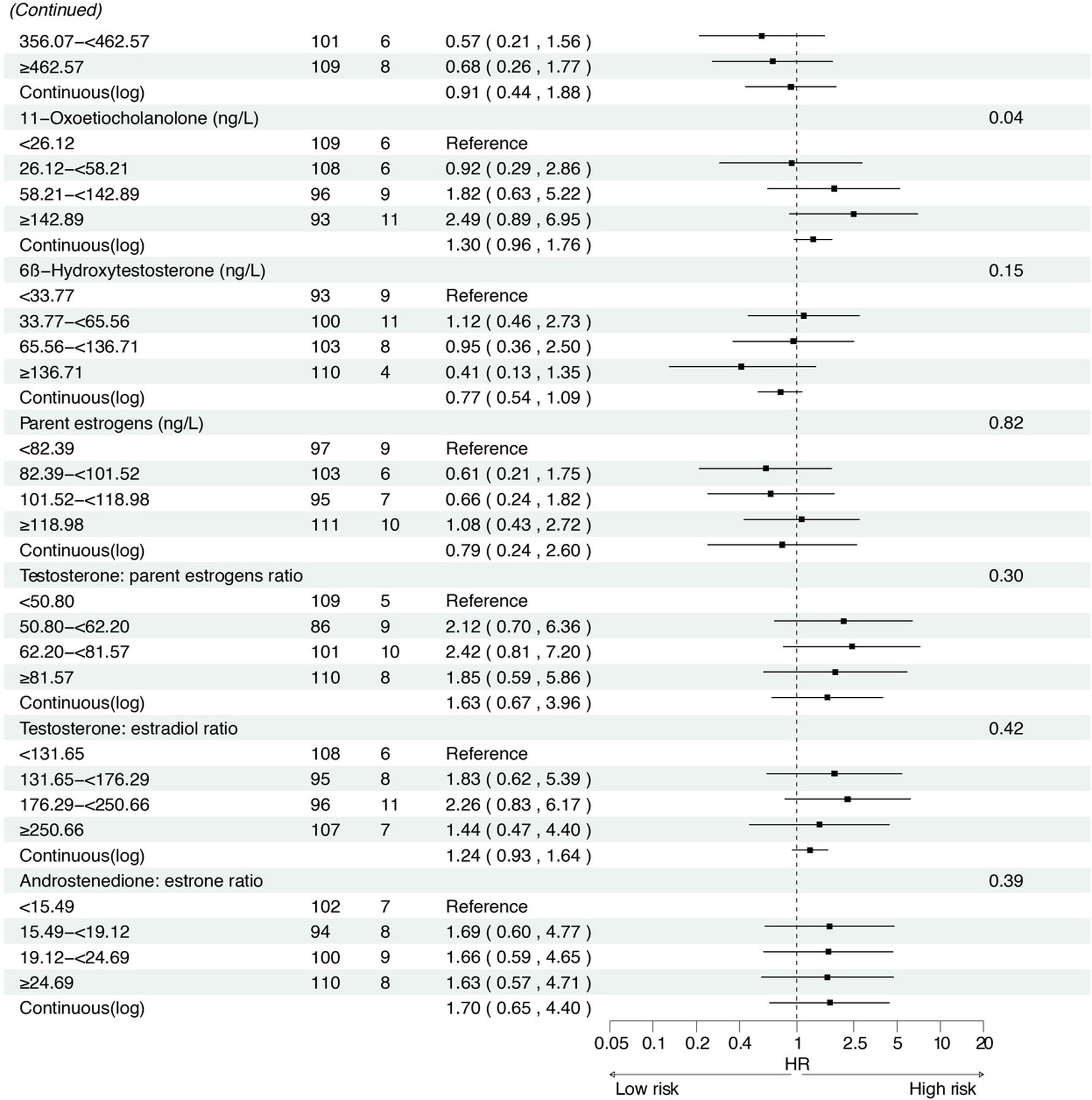

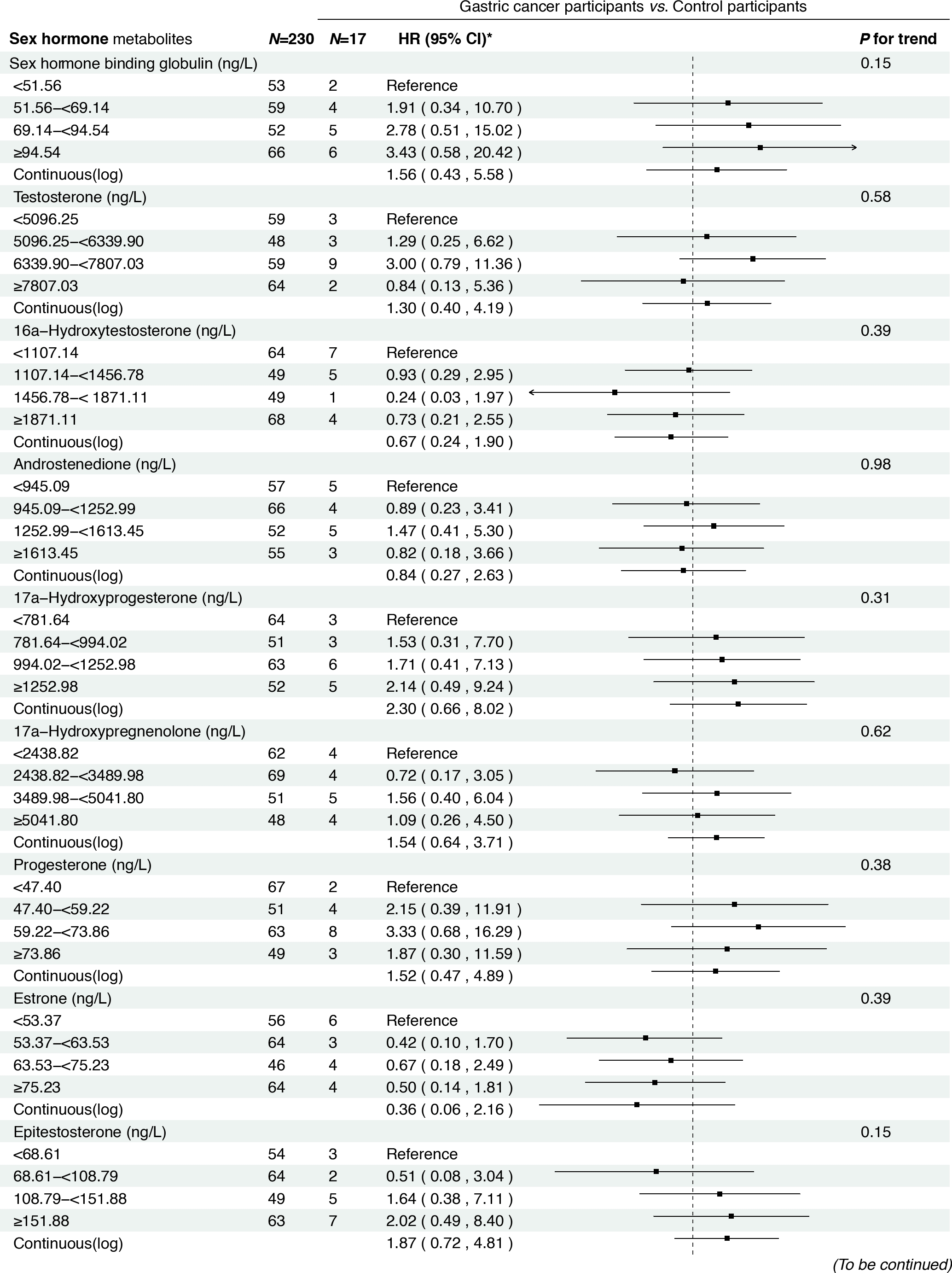

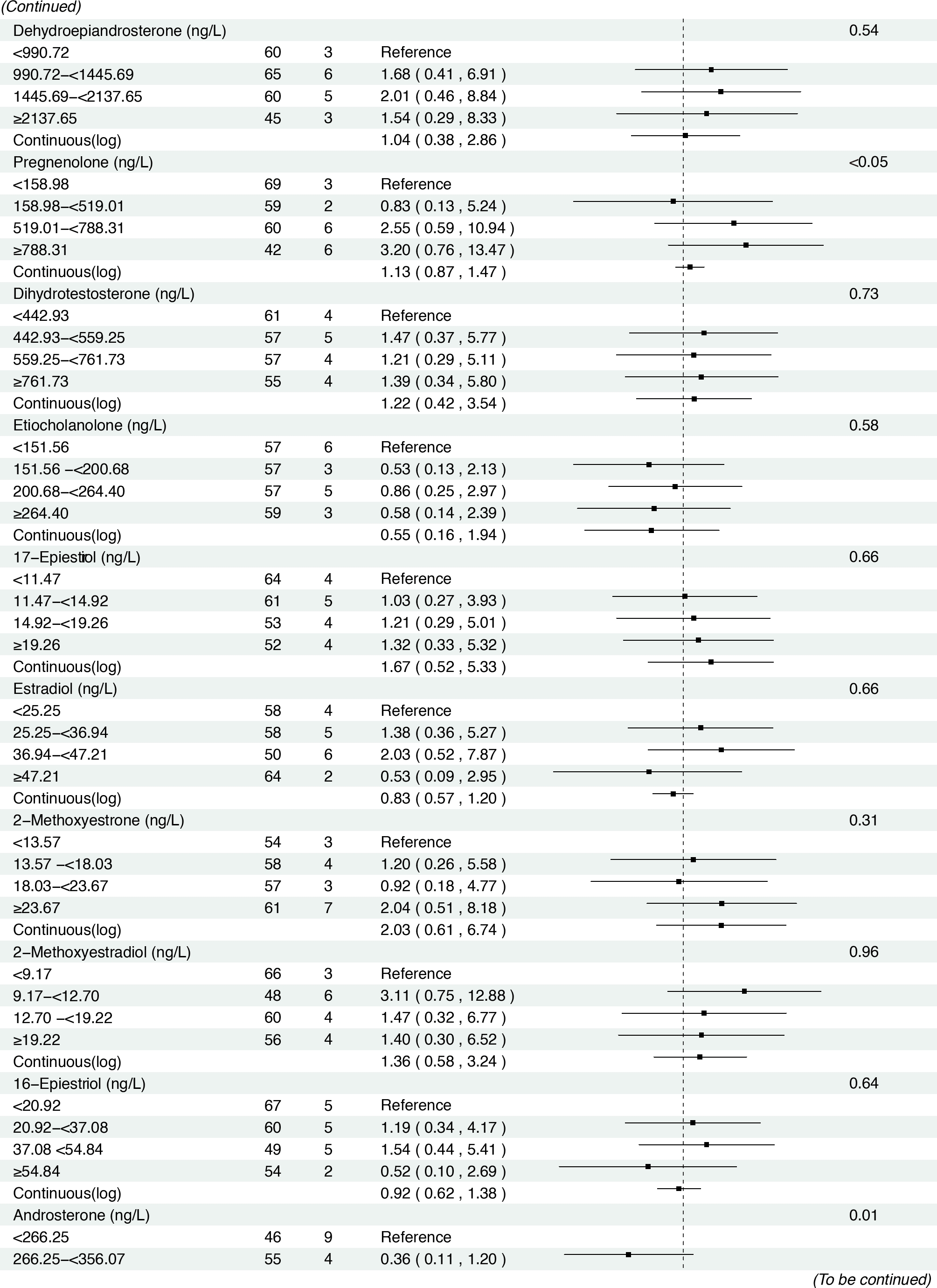

In the prospective cohort of 438 participants diagnosed with either normal or IM at baseline, we found positive associations between several serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and GC risk during a median follow-up of 11.8 years (IQR: 9.7–13.7 years). Specifically, statistically significant associations were observed between higher levels of SHBG (HRcontinuous = 2.57, 95% CI: 1.04–6.36), epitestosterone (HRcontinuous = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.07–4.15), and pregnenolone (HRcontinuous= 1.30, 95% CI: 1.03–1.63) and incident GC risk (Figure 3). The results remained consistent when analyzing the quartiles of SHBG (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 5.04, 95% CI: 1.23–20.63, Ptrend = 0.01), epitestosterone (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 3.82, 95% CI: 1.02–14.30, Ptrend = 0.04), and pregnenolone (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 4.70, 95% CI: 1.47–15.02, Ptrend < 0.01).

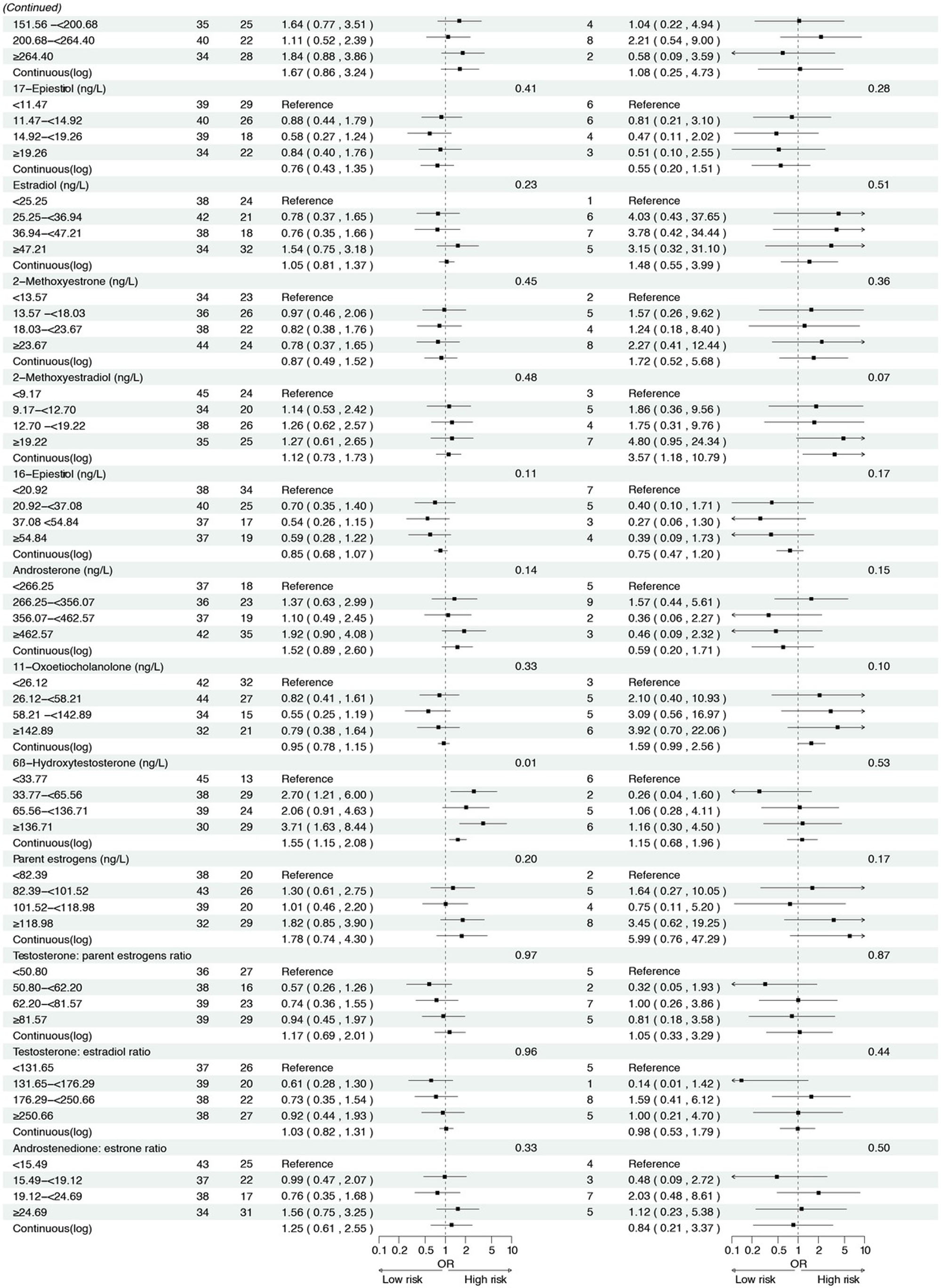

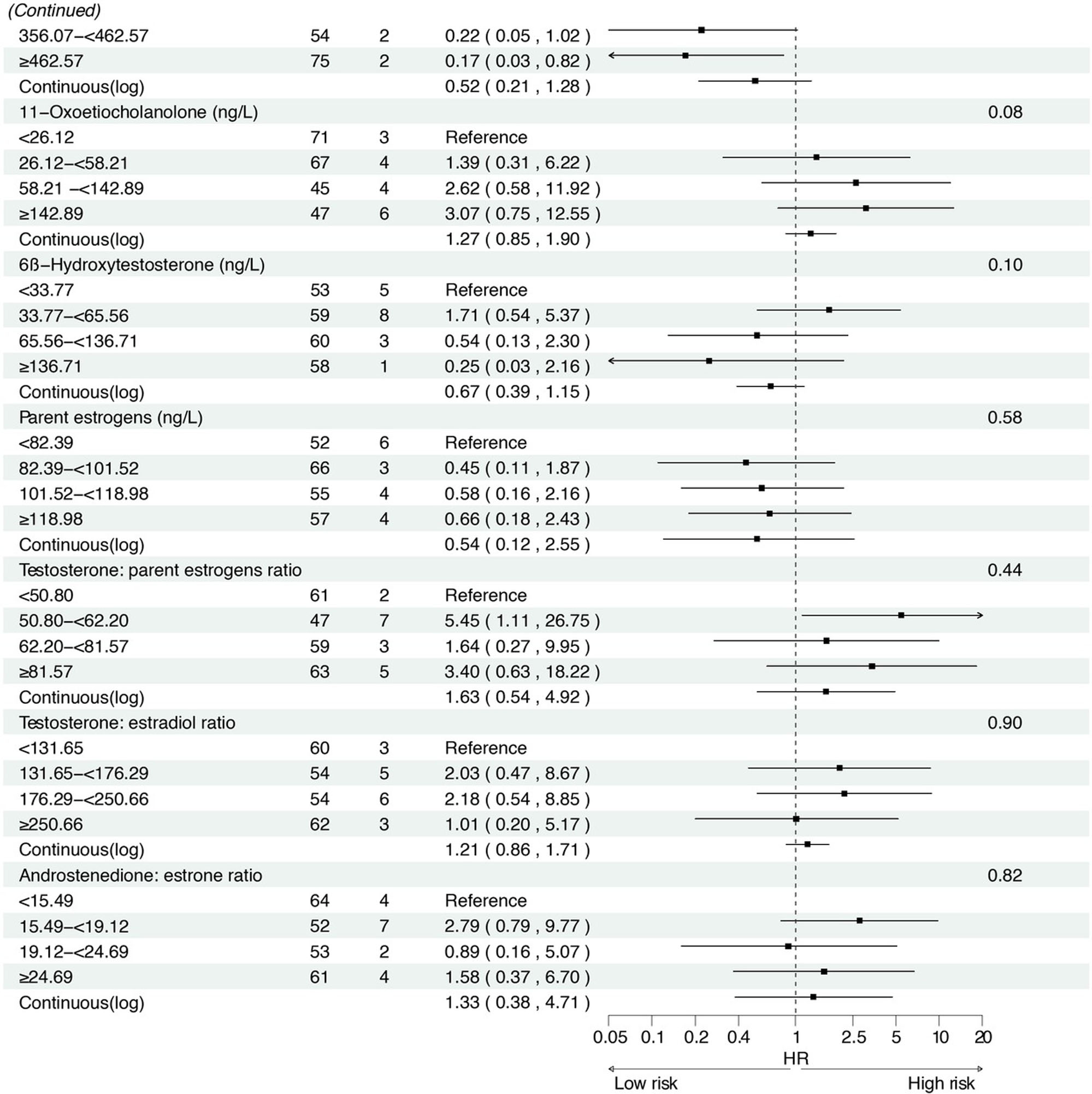

Sensitivity analysis

To further explore the potential modifying effect of H. pylori infection, we stratified the analysis by H. pylori CagA serostatus. Consistent associations between sex steroid hormone metabolites and the risk of GC or its precursors were observed in both the overall dataset and the stratified subgroups. Among H. pylori CagA-positive participants, higher levels of estrone were significantly associated with high-grade lesions or GC risk (Figure 4–5). Meanwhile, in H. pylori CagA-negative participants, increased levels of androstenedione, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, and progesterone were associated with the risk of high-grade lesions or GC, and both SHBG and pregnenolone exhibited positive associations with GC risk (Supplementary Figure S1–2). However, no statistically significant associations were observed between epitestosterone levels and the risk of GC and precancerous lesions in subgroup analyses, possibly reflecting limited statistical power due to small sample sizes within each stratum.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of Chinese men, elevated serum concentrations of androstenedione, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, progesterone and estrone were significantly associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC. During a median follow-up of 11.8 years, positive associations with incident GC risk were also observed for SHBG, epitestosterone and pregnenolone.

Associations between sex hormone metabolites and intestinal metaplasia and high-grade lesions or gastric cancer risk. *: Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, drinking, history of upper gastrointestinal disease, family history of cancer, H.pylori CagA. IM, intestinal metaplasia; GC, gastric cancer.

Associations between baseline sex hormone metabolites and incident gastric cancer risk from 2007 to 2021. *: Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, drinking, history of upper gastrointestinal disease, family history of cancer, H.pylori CagA.

Notably, with the exception of epitestosterone, these associations remained robust across analyses stratified by H. pylori serostatus. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential contributory role for sex hormone metabolites in the gastric carcinogenesis.

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to explore associations between circulating sex hormones and the risk of GC and its precancerous lesions, including high-grade lesions and IM. In cross-sectional analyses, elevated androstenedione levels were associated with an increased risk of IM, with even stronger associations observed for high-grade lesions or GC (OR = 2.45). Although evidence linking androstenedione to IM is limited, with only one animal study implicating testosterone,[31] the metabolic interconversion between testosterone and androstenedione,[32] together with the observed progression risk, supports androstenedione as a promising biomarker in early gastric carcinogenesis. Notably, this association was markedly stronger in H. pylori CagA-negative individuals (OR = 4.84), suggesting a potentially distinct carcinogenic pathway independent of H. pylori infection.

Associations between sex hormone metabolites and gastric cancer and its precursors among H. pylori CagA-positive participants. *: Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, drinking, history of upper gastrointestinal disease, family history of cancer. IM, intestinal metaplasia; GC, gastric cancer.

Associations between baseline sex hormone metabolites and incident gastric cancer risk among H. pylori CagA-positive participants. *: Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, drinking, history of upper gastrointestinal disease, family history of cancer.

Previous mechanistic studies have reported that androgens, including androstenedione, exert their biological effects through the androgen receptor (AR), which has been linked to increased GC risk, H. pylori-negative status, and immune evasion, such as CD 8+ T cell exhaustion.[33,34] These findings support the hypothesis that the androgen-AR axis plays a key role in GC development, although further mechanistic validation is needed. In addition, higher levels of estrone, a precursor metabolized to estradiol, were also significantly associated with an increased risk of high-grade gastric lesions or GC (OR continuous = 5.36). Mechanistically, estradiol has been shown to promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition in GC cells, an effect further potentiated by coinfection with CagA-positive H. pylori,[35] which aligns with our subgroup analyses demonstrating stronger associations between estrone and high-grade lesions or GC in CagA-positive individuals (OR continuous = 7.34). These findings suggest a synergistic interplay between sex hormones and H. pylori infection in gastric carcinogenesis.

Progesterone exerts its effects through the progesterone receptor (PR), and biological studies have reported that the PR expression is increased in GC,[36] with elevated PR expression being associated with poorer prognosis in GC.[37] These findings are consistent with our results, where higher progesterone concentrations were associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC. Moreover, this evidence further supports the positive association between pregnenolone levels and incident GC risk observed during the 11.8-year prospective follow-up. As illustrated in the sex steroid hormone metabolism pathway,[32] pregnenolone can be metabolized into progesterone, thereby influencing the development of GC. In addition, higher levels of 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, which acts as a metabolite of pregnenolone, were also associated with an increased risk of high-grade lesions or GC. Interestingly, the associations of these sex hormone metabolites with GC and precancerous lesions remained consistent across subgroup analyses stratified by H. pylori status. Therefore, further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the complex effects of sex hormone metabolites on GC and precancerous lesions, as well as the potential interactive effects of H. pylori infection on these associations.

In the prospective analysis, we observed an increased risk of incident GC in participants with higher epitestosterone levels. To our knowledge, the biosynthetic and metabolic pathways of epitestosterone in humans are not fully elucidated, and studies exploring the association between epitestosterone and GC are limited. However, two Mendelian randomization analyses have reported that testosterone is associated with a lower risk of GC in men.[21,38] Epitestosterone, a natural steroid metabolite and the 17 alpha-hydroxy epimer of testosterone produced by the immature testis, may be involved in regulating androgen-dependent events such as prostate growth.[39] It may also function as a 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor and an antiandrogen by competitively binding to the AR, thereby inhibiting testosterone biosynthesis.[40] These findings imply that epitestosterone may contribute to the development of GC by affecting the metabolism pathway of testosterone. However, we did not observe a significant association between epitestosterone and GC risk in subgroup analyses, which suggests that H. pylori infection may interact with epitestosterone levels, potentially modifying its association with GC risk.

In addition, we observed a positive association between higher levels of SHBG and incident GC in men. This finding is consistent with the results of two prospective studies based on the UK Biobank, which reported that elevated SHBG levels were associated with an increased risk of GC.[23,41] Another meta-analysis also showed that higher levels of SHBG increased the risk of GC in men.[42] Our study provides novel epidemiological evidence supporting the hypothesis that sex hormone dysregulation may play a role in gastric carcinogenesis.

This study has several strengths. We collected extensive information on potential confounders of GC, including common risk factors such as age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, etc., as well as the established serologic biomarkers such as H. pylori serostatus in the current screening guideline of Chinese populations. By adjusting for key risk factors and stratifying by H. pylori infection, we investigated the associations of up to 20 sex steroid hormone metabolites with GC and its precursors, thereby providing additional biomarkers for identifying high-risk populations for GC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously investigate the associations between sex hormones and GC and precancerous lesions (high-grade lesions and IM) in Chinese men, offering insight into the potential role of sex hormones in the development of GC. However, this study also had several limitations. The modest sample size may have limited our ability to identify significant associations between certain sex steroid hormone metabolites and GC and its precursors; meanwhile, the limited number of GC cases constrained the performance of subsite analysis of cardia and non-cardia GC.

In conclusion, we found that several sex steroid hormone metabolites were associated with GC and precancerous lesions in a prospective cohort of Chinese men. These findings suggest a role for sex hormones in the carcinogenesis of GC. With further validation, these findings may contribute to the understanding of the etiology of GC, and help provide novel biomarkers for the precision identification of high-risk populations and risk prediction of GC.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary materials are only available at the official site of the journal (www.intern-med.com).

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research [2024-2G-40213], the Beijing Nova Program [Z201100006820069], the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences [2019-I2M-2-004, 2021-I2M-1-023], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [82272435, 82273704, 81502864], and Talent Incentive Program of Cancer Hospital, CAMS [Hope Star].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to all the local residents who participated in this study and made it possible, and to all the health workers who contributed greatly to the screening and follow-up.

-

Author Contributions

J. Li and W. Cui designed the study, carried out statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; F. He, Z. Fan, J. Gu, and X. Li contributed to data acquisition and reviewed the manuscript; L. Xue, W. Rao, Z. Wang, Z. Wu were involved in experimental studies, data analysis and reviewed the manuscript; W. Wei designed the study and reviewed the manuscript; S. Wang conceptualized, edited and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Formal ethical approval (No. 20/386-2582) for this study was issued on November 18, 2020 by the Institutional Review Board of the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

-

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and participants’ privacy rights were always be respected.

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools

During the revision of this manuscript, the authors used DeepSeek (https://chat.deepseek.com) to assist in proofreading and refining the structure of this manuscript. The prompts used included: “Please check the grammar and suggest improvements for clarity.”

-

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at Shaoming Wang, wangshaoming@cicams.ac.cn.

1 Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med 2009;6:e50.10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2 Jorgenson E, Thai KK, Hoffmann TJ, Sakoda LC, Kvale MN, Banda Y, et al. Genetic contributors to variation in alcohol consumption vary by race/ethnicity in a large multi-ethnic genome-wide association study. Mol Psychiatry 2017;22:1359–1367.10.1038/mp.2017.101Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3 Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global cancer observatory: cancer today (version 1.1). Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today. Accessed 18 Sep 2024.Search in Google Scholar

4 Li M, Sun Y, Yang J, de Martel C, Charvat H, Clifford GM, et al. Time trends and other sources of variation in Helicobacter pylori infection in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter 2020;25:e12729.10.1111/hel.12729Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5 Rustgi SD, Zylberberg HM, Hur C, Shah SC. Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;21:2178–2182.10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Song H, Ekheden IG, Zheng Z, Ericsson J, Nyrén O, Ye W. Incidence of gastric cancer among patients with gastric precancerous lesions: observational cohort study in a low risk Western population. BMJ 2015;351:h3867.10.1136/bmj.h3867Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7 Liu S, Wen H, Li F, Xue X, Sun X, Li F, et al. Revealing the pathogenesis of gastric intestinal metaplasia based on the mucosoid air-liquid interface. J Transl Med 2024;22:468.10.1186/s12967-024-05276-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8 Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent 2024;4:47–53.10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9 Jackson SS, Marks MA, Katki HA, Cook MB, Hyun N, Freedman ND, et al. Sex disparities in the incidence of 21 cancer types: Quantification of the contribution of risk factors. Cancer 2022;128:3531–3540.10.1002/cncr.34390Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10 Ibrahim A, Morais S, Ferro A, Lunet N, Peleteiro B. Sex-differences in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatric and adult populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 244 studies. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:742–749.10.1016/j.dld.2017.03.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11 Freedman ND, Derakhshan MH, Abnet CC, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, McColl KE. Male predominance of upper gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma cannot be explained by differences in tobacco smoking in men versus women. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2473–2478.10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12 Lindblad M, Rodríguez LA, Lagergren J. Body mass, tobacco and alcohol and risk of esophageal, gastric cardia, and gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma among men and women in a nested case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 2005;16:285–294.10.1007/s10552-004-3485-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13 Frise S, Kreiger N, Gallinger S, Tomlinson G, Cotterchio M. Menstrual and reproductive risk factors and risk for gastric adenocarcinoma in women: findings from the canadian national enhanced cancer surveillance system. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:908–916.10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Freedman ND, Chow WH, Gao YT, Shu XO, Ji BT, Yang G, et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors and gastric cancer risk in a large prospective study of women. Gut 2007;56:1671–1677.10.1136/gut.2007.129411Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15 Green J, Czanner G, Reeves G, Watson J, Wise L, Roddam A, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of gastrointestinal cancer: nested case-control study within a prospective cohort, and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2012;130:2387–2396.10.1002/ijc.26236Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16 Chandanos E, Lindblad M, Jia C, Rubio CA, Ye W, Lagergren J. Tamoxifen exposure and risk of oesophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma: a population-based cohort study of breast cancer patients in Sweden. Br J Cancer 2006;95:118–122.10.1038/sj.bjc.6603214Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Shore R, Yu J, Ye W, Lagergren J, Rutegård M, Akre O, et al. Risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Sci Rep 2021;11:13486.10.1038/s41598-021-92347-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18 Maggio M, Basaria S, Ceda GP, Ble A, Ling SM, Bandinelli S, et al. The relationship between testosterone and molecular markers of inflammation in older men. J Endocrinol Invest 2005;28:116–119.Search in Google Scholar

19 Chun-Hou Liao, Hung-Yuan Li, Hong-Jeng Yu, Han-Sun Chiang, Mao-Shin Lin, Cyue-Huei Hua, et al. Low serum sex hormone-binding globulin: marker of inflammation? Clin Chim Acta 2012;413:803–807.10.1016/j.cca.2012.01.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20 Liu B, Zhou M, Li X, Zhang X, Wang Q, Liu L, et al. Interrogation of gender disparity uncovers androgen receptor as the transcriptional activator for oncogenic miR-125b in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis 2021;12:441.10.1038/s41419-021-03727-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21 Chang J, Wu Y, Zhou S, Tian Y, Wang Y, Tian J, et al. Genetically predicted testosterone and cancers risk in men: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Transl Med 2022;20:573.10.1186/s12967-022-03783-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22 Leal YA, Song M, Zabaleta J, Medina-Escobedo G, Caron P, Lopez-Colombo A, et al. Circulating Levels of Sex Steroid Hormones and Gastric Cancer. Arch Med Res 2021;52:660–664.10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23 McMenamin ÚC, Liu P, Kunzmann AT, Cook MB, Coleman HG, Johnston BT, et al. Circulating Sex Hormones Are Associated With Gastric and Colorectal Cancers but Not Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in the UK Biobank. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:522–529.10.14309/ajg.0000000000001045Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24 Zhu Z, Chen Y, Ren J, Dawsey SM, Yin J, Freedman ND, et al. Serum Levels of Androgens, Estrogens, and Sex Hormone Binding Globulin and Risk of Primary Gastric Cancer in Chinese Men: A Nested Case-Control Study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2021;14:659–666.10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-20-0497Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25 Li M, Park JY, Sheikh M, Kayamba V, Rumgay H, Jenab M, et al. Population-based investigation of common and deviating patterns of gastric cancer and oesophageal cancer incidence across populations and time. Gut 2023;72:846–854.10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328233Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26 The National Cancer Control Office of the Ministry of Health, Nanjing Institute of Geography, Academia Sinica, et al., editors. Atlas of cancer mortality in the People’s Republic of China. Shanghai, China: China Map Press; 1979:31–38.Search in Google Scholar

27 Wei WQ, Hao CQ, Guan CT, Song GH, Wang M, Zhao DL, et al. Esophageal Histological Precursor Lesions and Subsequent 8.5-Year Cancer Risk in a Population-Based Prospective Study in China. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1036–1044.10.14309/ajg.0000000000000640Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28 Wang GQ, Wei WQ. Technology scheme for upper gastrointestinal cancer early detection and treatment. Beijing, China: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2020:103–116.Search in Google Scholar

29 Fritz AG. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed., first revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

30 World Health Organization. ICD- 10 Version:2019. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/. Accessed 18 Sep 2024.Search in Google Scholar

31 Watanabe H, Okamoto T, Matsuda M, Takahashi T, Ogundigie PO, Ito A. Effects of sex hormones on induction of intestinal metaplasia by X-irradiation in rats. Acta Pathol Jpn 1993;43:456–463.10.1111/j.1440-1827.1993.tb01158.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Li J, He F, Fan Z, Xue L, Rao W, Wang Z, et al. [Associations Between Pre-Diagnostic Serum Sex Steroid Hormone Metabolites and Esophageal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions in Men: A Prospective Cohort Study]. China Cancer 2024;33:731–746.Search in Google Scholar

33 Yang C, Jin J, Yang Y, Sun H, Wu L, Shen M, et al. Androgen receptor-mediated CD8+ T cell stemness programs drive sex differences in antitumor immunity. Immunity 2022;55:1747.10.1016/j.immuni.2022.07.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34 Choi Y, Kim N, Park JH, Song CH, Oh HJ. Expression Rates of Sex Hormone Receptors with Their Clinical Correlates in Gastric Cancer Patients and Normal Controls. World J Mens Health 2025 Jan 16. Epub ahead of print.10.5534/wjmh.240272Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35 Kang S, Park M, Cho JY, Ahn SJ, Yoon C, Kim SG, et al. Tumorigenic mechanisms of estrogen and Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene A in estrogen receptor α-positive diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastric Cancer 2022;25:678–696.10.1007/s10120-022-01290-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36 Tan X, Wu X, Ren S, Wang H, Li Z, Alshenawy W, et al. A Point Mutation in DNA Polymerase β (POLB) Gene Is Associated with Increased Progesterone Receptor (PR) Expression and Intraperitoneal Metastasis in Gastric Cancer. J Cancer 2016;7:1472–1480.10.7150/jca.14844Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37 Li M, Zhou C. Progesterone receptor gene serves as a prognostic biomarker associated with immune infiltration in gastric cancer: a bioinformatics analysis. Transl Cancer Res 2021;10:2663–2677.10.21037/tcr-21-218Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38 Liu X, Lin L, Cai Q, Li C, Xu H, Zeng R, et al. Do testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin affect cancer risk? A Mendelian randomization and bioinformatics study. Aging Male 2023;26:2261524.10.1080/13685538.2023.2261524Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39 Stárka L. Epitestosterone. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2003;87:27–34.10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00383-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40 Cavalari FC, da Rosa LA, Escott GM, Dourado T, de Castro AL, Kohek MBDF, et al. Epitestosterone- and testosterone-replacement in immature castrated rats changes main testicular developmental characteristics. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2018;461:112–121.10.1016/j.mce.2017.08.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41 Sanikini H, Biessy C, Rinaldi S, Navionis AS, Gicquiau A, Keski-Rahkonen P, et al. Circulating hormones and risk of gastric cancer by subsite in three cohort studies. Gastric Cancer 2023;26:969–987.10.1007/s10120-023-01414-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42 Liu Z, Zhang Y, Lagergren J, Li S, Li J, Zhou Z, et al. Circulating Sex Hormone Levels and Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2023;32:936–946.10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-23-0039Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 Jiayue Li, Wei Cui, Feifan He, Zhiyuan Fan, Liyan Xue, Wei Rao, Zongdan Wang, Zeming Wu, Jianhua Gu, Xinqing Li, Wenqiang Wei, Shaoming Wang, published by De Gruyter on behalf of Scholar Media Publishing

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Prehospital neuroprotective intervention: A critical imperative evidenced by the FRONTIER trial outcomes

- Artificial intelligence in rheumatology: A transformative perspective

- Dialysis adequacy revisited: Kt/V's blind spot for phosphorus and iodine

- Review Article

- The plakin family: Potential therapeutic targets for digestive system tumors

- Original Article

- Lnc5q21.2, a novel long intergenic RNA, sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to ATR inhibitor by activating Wnt pathway

- Effect of bone marrow mononuclear cells therapy on long-term survival of patients with liver cirrhosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using propensity score matching

- Associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and gastric cancer and precancerous lesions in men: A 11.8-year prospective study

- Comprehensive investigation of cuproptosis-related genes in clinical features, biological characteristics, and immune microenvironment in B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Protocol

- A multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial of intravenous thrombolysis with tenecteplase for acute non-large vessel occlusion in extended time window (OPTION): Rationale and design

- Rapid Communication

- Association between anemia and 1-year recurrence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- Prehospital neuroprotective intervention: A critical imperative evidenced by the FRONTIER trial outcomes

- Artificial intelligence in rheumatology: A transformative perspective

- Dialysis adequacy revisited: Kt/V's blind spot for phosphorus and iodine

- Review Article

- The plakin family: Potential therapeutic targets for digestive system tumors

- Original Article

- Lnc5q21.2, a novel long intergenic RNA, sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to ATR inhibitor by activating Wnt pathway

- Effect of bone marrow mononuclear cells therapy on long-term survival of patients with liver cirrhosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using propensity score matching

- Associations between serum sex steroid hormone metabolites and gastric cancer and precancerous lesions in men: A 11.8-year prospective study

- Comprehensive investigation of cuproptosis-related genes in clinical features, biological characteristics, and immune microenvironment in B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Protocol

- A multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial of intravenous thrombolysis with tenecteplase for acute non-large vessel occlusion in extended time window (OPTION): Rationale and design

- Rapid Communication

- Association between anemia and 1-year recurrence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation