Breastfeeding in HIV-positive mothers under optimized conditions: ‘real-life’ results from a well-resourced healthcare setting

-

Cornelia Feiterna-Sperling

, Katharina von Weizsäcker

Abstract

Objectives

Global guidelines increasingly support breastfeeding among women living with HIV (WLWH) under optimized conditions. However, outcome data from high-resource settings remain limited.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed WLWH who delivered at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin between 2017 and 2023. Eligibility for breastfeeding required VL<50 cop/mL.

Results

Of 409 WLWH, 365 (89.2 %) were eligible and 77 (18.8 %) initiated breastfeeding. No case of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) was observed. Sustained viral suppression and ART adherence were key. Exclusive breastfeeding was associated with longer duration (p=0.001), midwifery care promoted exclusivity (p=0.009), and vaginal delivery was linked to longer duration (p=0.005).

Conclusions

Breastfeeding with VL<50 cop/mL appears safe in high-resource settings. Findings support individualized counseling, close monitoring, and multidisciplinary care. The increasing breastfeeding trend reflects a shift in clinical practice.

Introduction

Mother to child transmission (MTCT) of HIV can occur during pregnancy, delivery, or through breastfeeding. Without preventive measures, the risk of such transmission ranges from 15 to 45 % [1]. Advancements in antiretroviral therapy (ART) have significantly reduced this risk to below 1 % [2]. In a recent study from our clinic, the MTCT rate between 2014 and 2020 was 0.2 % [3]. Breastfeeding among mothers living with HIV (MLWH) has long been a topic of intense debate in resource-rich settings, as it involves weighing the well-documented benefits of breastfeeding against the potential risk of MTCT of the virus. The benefits of breastfeeding are widely documented and universally acknowledged [4]. Breastfeeding not only fosters maternal-infant bonding but also provides essential nutrients and antibodies crucial for the infant’s health [4]. Additionally, it positively influences neurological and cognitive development while strengthening the immune system [4]. The general recommendation for the population without HIV is exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, followed by complementary feeding up to two years or longer, depending on the preferences of the mother and child. Before delivery, healthcare providers should counsel patients with HIV on the risk of transmission through breastfeeding. This risk is influenced by maternal viral load (VL), ART adherence, infant postnatal prophylaxis (PNP), and feeding practices [5]. One pivotal study, the PROMISE study in Sub-Saharan Africa and India, reported an MTCT risk of 0.3 % after six months of exclusive breastfeeding under ART, increasing to 0.7 % after 12 and 24 months [6]. Breastfeeding recommendations for MLWH vary globally, reflecting healthcare resource availability. In low-resource settings, where safe formula access is limited, exclusive breastfeeding remains essential. WHO recommends six months of exclusive breastfeeding with maternal ART and short-term infant PNP, followed by continued breastfeeding with complementary feeding up to 24 months if maternal ART adherence is maintained [7], 8]. In contrast, high-resource settings have seen a paradigm shift. Earlier guidelines discouraged breastfeeding due to MTCT risk, but recent studies indicate that under optimal conditions characterized by shared decision-making, close medical monitoring, regular infant HIV PCR testing, maternal ART adherence, and sustained undetectable VL – the risk approaches zero [5], 9], 10]. The German-Austrian guidelines permit breastfeeding under strict conditions, including a fully suppressed maternal VL (<50 copies/ml) throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding, consistent ART adherence, and monthly VL monitoring of both mother and infant [11]. Despite these advances, challenges remain. Comprehensive counseling is crucial to support ART adherence and informed feeding decisions. Complications such as mastitis, nipple injury, abrupt cessation, or mixed feeding may increase MTCT risk [12], [13], [14]. Postpartum ART adherence is another concern, with only 53 % of women consistently taking prescribed medications [15]. Additionally, ART drug concentrations in breast milk vary, and while typically low, potential toxicity in the infant cannot be entirely excluded [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. PNP remains standard in many resource-rich countries, initiated within 6–12 h after birth, even with undetectable maternal VL. In some cases, prophylaxis is omitted under optimal maternal and infant conditions [11], [22], [23], [24]. This study evaluates breastfeeding outcomes among MLWH in a resource-rich setting under optimal conditions, focusing on MTCT rates and the role of multidisciplinary care.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

This single-center study was conducted at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, a tertiary care hospital in Germany between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2023. The study follow-up continued until February 13, 2025. The study aimed to evaluate MTCT of HIV during breastfeeding, as well as breastfeeding practices (exclusive vs. mixed) among MLWH under optimized conditions in a resource-rich setting. The study included WLWH treated in our institution who delivered during the study period and chose to breastfeed.

Data collection

Data were retrospectively extracted from medical records and hospital databases. Collected parameters included demographic information, as well as the date of HIV diagnosis (prior to or during pregnancy), clinical data such as maternal VL, CD4 cell counts, antiretroviral treatment, mode of delivery, midwifery care, breastfeeding practices, and duration of breastfeeding. Additional data included date of delivery, infant gender, birthweight, APGAR scores and PNP.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee (EA4/139/21). All data were fully pseudonymized before analysis to ensure participant confidentiality.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to assess the distribution of variables. Continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) or means with standard deviations (SD), depending on their distribution. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Group comparisons, such as between exclusive and mixed breastfeeding mothers, were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. A two-tailed p-Value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 30 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 2024).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of MTCT of HIV during the breastfeeding period. Secondary outcomes included the duration of (exclusive) breastfeeding and factors influencing breastfeeding practices, as well as breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., exclusive vs. mixed feeding).

Results

Participant characteristics

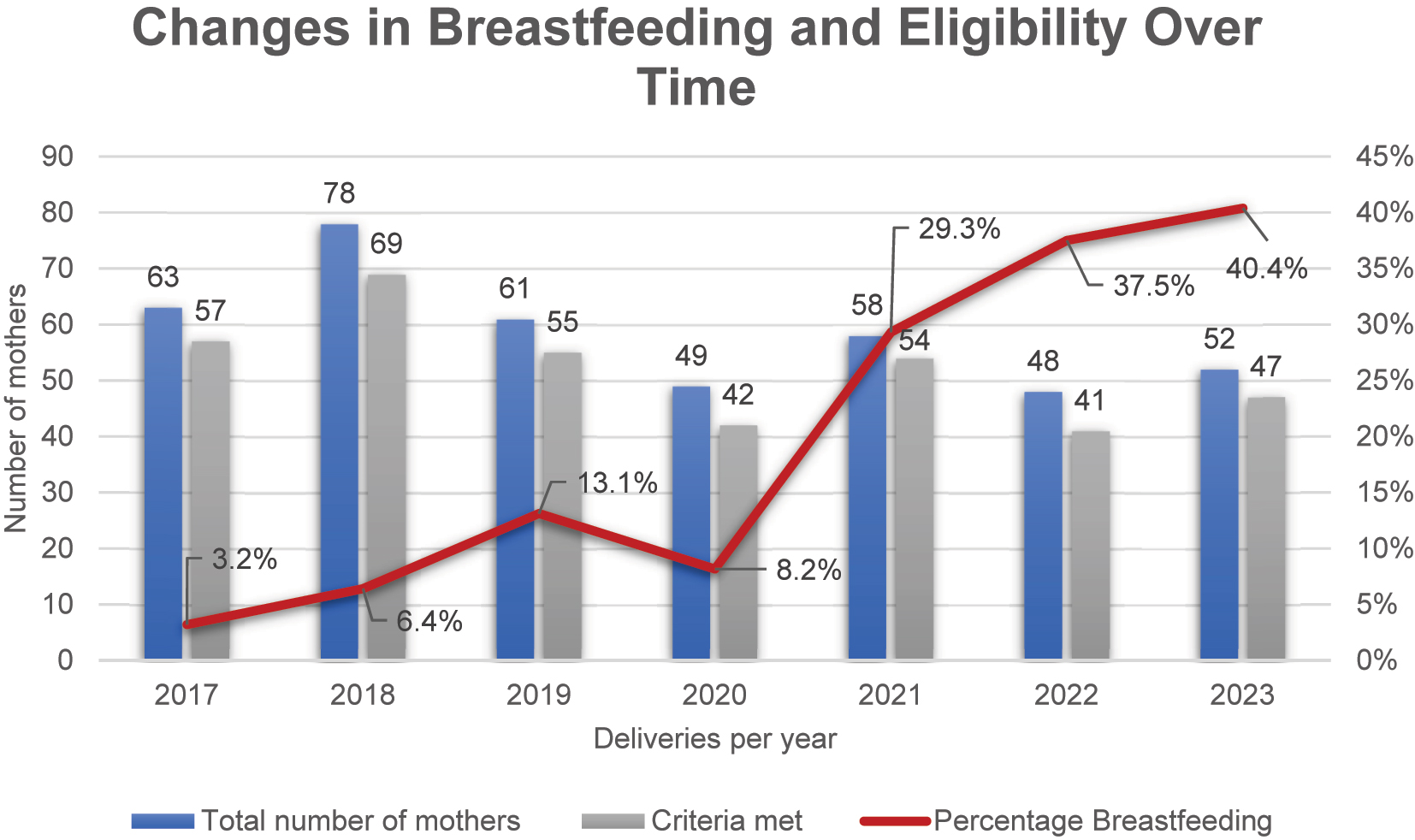

Between January 2017 and December 2023, a total of 409 WLWH were seen at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, who gave birth to 416 infants, including seven pairs of twins. Of these, 77 mothers (18.8 %) chose to breastfeed and were included in the analysis. A total of 365 women (89.2 %) met the eligibility criteria for breastfeeding, while 38 women (9.3 %) did not qualify due to a viral load exceeding 50 copies/mL. Data on VL were missing for six women (1.5 %). The proportion of WLWH meeting the eligibility criteria for breastfeeding remained consistently high across the years, ranging from 85.4 to 93.1 % in Figure 1. However, the percentage of women who actually breastfed showed a clear upward trend. In 2017, only 3.2 % of eligible women breastfed, increasing gradually to 13.1 % in 2019 and 29.3 % in 2021. This trend continued, reaching 37.5 % in 2022 and 40.4 % in 2023 in Figure 1. The median age of breastfeeding participants was 34.5 years (IQR 6.5). 69 (89.6 %) were diagnosed with HIV prior to pregnancy, with a median time since diagnosis of 8.2 years (IQR 6.01), while 8 (10.4 %) received their diagnosis during the present pregnancy. Most participants were from Sub-Saharan African (49/77, 63.6 %), followed by Western European origin (22/77, 28.6 %). Participants from Eastern Europe/Russia, Asia, and the Americas each accounted for 2.6 % (2/77).

The total number of mothers seen per year (blue bars), the number who met eligibility criteria for breastfeeding (grey bars), and the proportion of mothers who initiated breastfeeding (red line) are shown. While the proportion of women eligible for breastfeeding remained consistently high throughout the years (ranging from 85.4 to 93.1 %), the percentage of eligible women who chose to breastfeed increased steadily from 3.2 % in 2017 to 40.4 % in 2023.

At the time of delivery, all participants had undetectable HI-VL (<50 copies/mL) within the last two months, and the median CD4 cell count was 580.5/μL (IQR 240.0). The majority (62.9 %, 44/70) had CD4 cell counts>500/μL, with only one participant (1.4 %) below 200/μL. Data on CD4 cell counts were not available for seven participants. Mode of delivery was reported for 76 participants. Spontaneous vaginal delivery was the most common mode (40/75, 52.6 %), followed by cesarean section (31/75, 40.8 %) and vacuum extraction (5/75, 6.6 %). These data are summarized in Table 1.

Descriptive analyses of the cohort.

| Characteristics of the breastfeeding mothers | Number of observations | % |

|---|---|---|

| n=77 | ||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 77, 34.5 (6.5) | |

| <20 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–27 | 5 | 6.5 |

| 28–35 | 42 | 54.5 |

| >35 | 30 | 39.0 |

| Initial diagnosis of HIV infection prior to pregnancy | 77 | |

| Yes | 69 | 89.6 |

| No | 8 | 10.4 |

| Region of origin | 77 | |

| Sub-saharan Africa | 49 | 63.6 |

| Western Europe | 22 | 28.6 |

| Eastern Europe/Russia | 2 | 2.6 |

| Asia | 2 | 2.6 |

| America (north-, middle- and south) | 2 | 2.6 |

| HIV viral load, cop/mL | ||

| <50 | 77 | 100 |

| CD4 cell, count/μL – median (IQR) | 70, 580.5 (240.0) | |

| <200 | 1 | 1.4 |

| ≥200–350 | 5 | 7.1 |

| ≥350–500 | 20 | 28.6 |

| >500 | 44 | 62.9 |

| ART regime | 77 | |

| 2 NRTI’s+PI | 13 | 16.9 |

| 2 NRTI’s+INI | 31 | 40.3 |

| 2 NRTI’s+NNRTI | 27 | 35.1 |

| Other | 6 | 7.8 |

| ART before pregnancy | 76 | |

| Yes | 69 | 90.8 |

| No | 7 | 9.2 |

| Mode of delivery | 76 | |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 40 | 52.6 |

| Cesarean section | 31 | 40.8 |

| Vaginal extraction | 5 | 6.6 |

| Midwifery care | 69 | |

| Yes | 40 | 58 |

| No | 29 | 42 |

| Brestfeeding experience | 72 | |

| Yes | 38 | 52.8 |

| No | 34 | 47.2 |

| Breastfeeding duration, months, median (IQR) | 72 | 7.3 (7.6) range: 0.1–33.9 monthsa |

-

IQR, interquartile range; MW, mean value; SD, standard deviation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; ART, antiretroviral therapy; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; INI, integrase inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery; CS, cesarean section; VE, vaginal extraction. aOf the two children still being breastfed at the end of the follow-up, one had been breastfeeding for 39 months and the other for 24 months. These durations reflect the length of breastfeeding up to the last follow-up visit.

Characteristics of infants

Among the 77 infants, 42 (54.5 %) were male, and 35 (45.5 %) were female. The median gestational age at birth was 39.0 weeks (IQR 2.0), with 96.1 % (73/76) born at term (≥37 weeks). One gestational age record was missing. The median birth weight was 3,490 g (IQR 675 g). APGAR scores at 10 min were available for 75 infants: 68 (90.7 %) scored 10, 4 (5.3 %) scored 9, and 3 (4.0 %) scored 8 (see Table 2).

Characteristics of breastfed infants.

| Characteristics of breastfed infants | Number of observations | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | 76 | Median (IQR)/Mean (SD) | 39.0 (2.0)/39.0 (1.3) |

| Gestational age≥37+0 weeks | 76 | 73 | 96.1 |

| Gestational age<37+0 weeks | 76 | 3 | 3.9 |

| Sex | 77 | ||

| Male | 42 | 54.5 | |

| Female | 35 | 45.5 | |

| Birth weight, g | 77 | Median (IQR)/Mean (SD) | 3,490.0 (675)/3,398.5 (507.8) |

| APGAR score at 10 min | 75 | ||

| 10 | 68 | 90.7 | |

| 9 | 4 | 5.3 | |

| 8 | 3 | 4.0 | |

| Zidovudine prophylaxis | 77 | 75 | 97.4 |

-

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; APGAR, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration.

Trends in breastfeeding over time

The number of MLWH who chose to breastfeed increased steadily throughout the study period from 2 out of 64 women (3.2 %) in 2017 to 21 out of 53 women (40.6 %) in 2023; see Figure 1. These changes likely reflect evolving counseling practices, greater patient awareness, and updated guidelines that support breastfeeding for MLWH under optimized conditions.

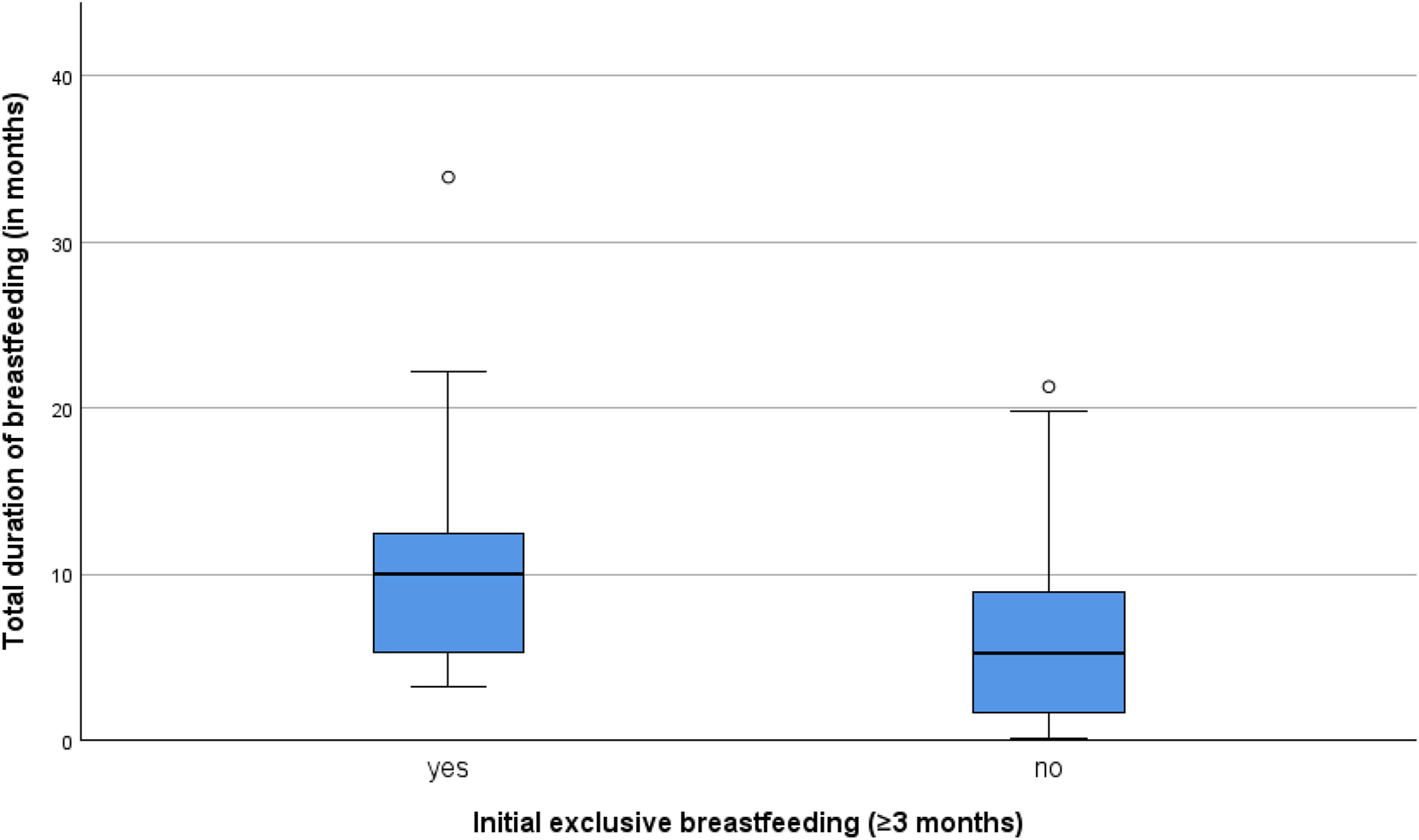

Breastfeeding practices

Of the 77 participants, 39 (50.6 %) practiced exclusive breastfeeding for at least three months, while 32 (41.6 %) engaged in mixed feeding. The median breastfeeding duration was 7.3 months (IQR 7.6), with a range of 0.1–33.9 months. Seven women (9.1 %) breastfed for less than one month. Of the two children still being breastfed at the end of the follow-up, one had been breastfeeding for 39 months and the other for 24 months. Exclusive breastfeeding in the first three months was associated with significantly longer overall breastfeeding durations (median 10.0 months; IQR 7.4) compared to mixed feeding (median 6.2 months; IQR 6.3; p=0.001) (see Figure 2). Maternal breastfeeding experience had no impact on the likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding (p=0.779).

Newborns who were exclusively breastfed for at least the first three months and did not receive any formula during that time were breastfed for significantly longer durations compared to those who were not exclusively breastfed (p=0.001). The median breastfeeding duration was higher among exclusively breastfed newborns. The boxplot highlights a broader variability in breastfeeding durations among newborns who were not exclusively breastfed, with notable outliers in both groups.

Impact of mode of delivery and midwifery care

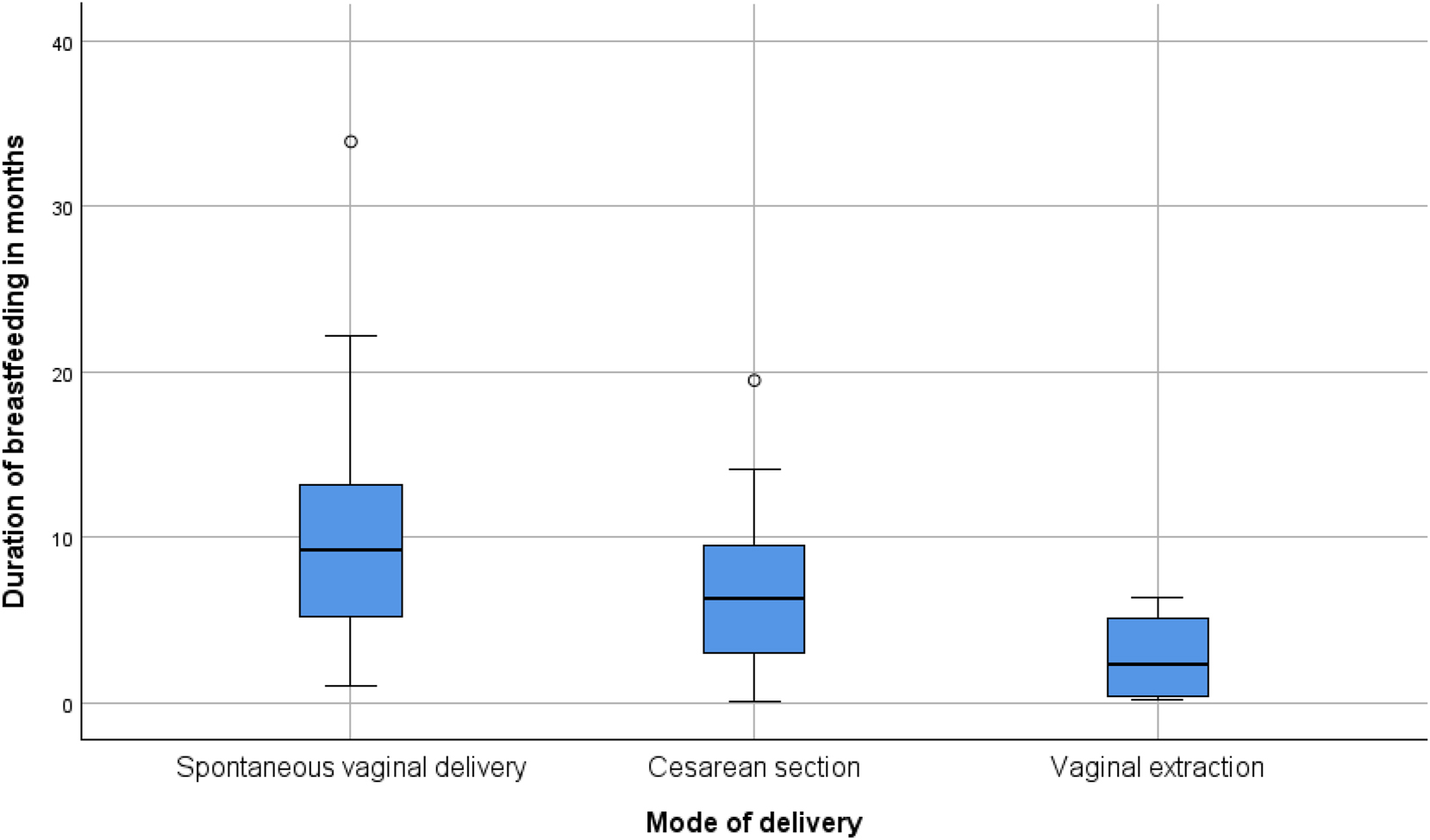

The duration of breastfeeding was significantly associated with the mode of delivery (p=0.005). Women who had a spontaneous vaginal delivery breastfed for a median duration of approximately 10 months, whereas those who underwent a cesarean section had a median duration of around 5 months. The shortest breastfeeding durations were observed in the vacuum extraction group, with a median of approximately 3–4 months. Variability within groups is displayed in Figure 3.

The duration of breastfeeding was significantly associated with the mode of delivery (p=0.005). Women who had a spontaneous vaginal delivery breastfed for a median duration of approximately 10 months, whereas those who underwent a cesarean section had a median duration of around 5 months. The shortest breastfeeding durations were observed in the vaginal extraction group, with a median of approximately 3–4 months. The variability within groups is displayed in Figure 2, with an outlier identified in the spontaneous vaginal delivery group.

Midwifery care was provided to 40 participants (58 %), and exclusive breastfeeding was significantly associated with midwifery care (p=0.009). Women who received midwifery support were more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding compared to those without such care, as shown in Figure 4.

Distribution of exclusive vs. non-exclusive breastfeeding among mothers with and without midwifery care. Among those who received midwifery support (n=40), the majority practiced exclusive breastfeeding (n=26). In contrast, among mothers without midwifery care (n=29), exclusive breastfeeding was less common (n=11). The association between midwifery care and exclusive breastfeeding was statistically significant (p=0.009).

Infant outcomes

HIV infection was definitively excluded in 97.4 % (75/77) of HIV-exposed breastfed through HIV DNA PCR testing three months after weaning. The two infants who are still being breastfed have remained HIV DNA PCR negative to date, with final confirmation pending post-weaning testing. Zidovudine (ZDV) prophylaxis with a median duration of 14.0 days (range 0–36) was administered to 75 out of 77 infants (97.4 %), while two mothers opted against ZDV prophylaxis for their infants. Among the 76 (98.7 %) breastfed neonates, 56 (72.7 %) received ZDV for two weeks, 19 (24.7 %) for more than two weeks, and 2 (2.6 %) did not receive prophylaxis.

ART regimens and maternal monitoring

Among the mothers, 69/76 (90.8 %) had initiated ART prior to pregnancy. The most common ART regimen was 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) + integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) (40.3 %, 31/77), followed by 2 NRTIs + non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) (35.1 %, 27/77), and 2 NRTIs + protease inhibitor (PI) (16.9 %, 13/77). ART regimens did not significantly impact breastfeeding duration (p=0.798), nor was there a significant correlation between maternal CD4 cell counts and breastfeeding duration (Spearman ρ=0.15; p>0.05). Regarding maternal follow-up, 14 mothers (18.2 %) had monthly monitoring, 8 (10.4 %) were monitored bi-monthly, and 39 (50.6 %) had three-monthly follow-ups. In 16 cases (20.8 %), follow-up frequency was unknown, due to incomplete documentation or missing follow-up visits. Two women experienced an increase in VL during breastfeeding, leading to cessation. One had regular monthly monitoring, while the other had irregular follow-ups, with the VL rise detected during a sporadic visit. Another woman had a transient VL blip of 800 copies/mL, was monitored bi-monthly, continued breastfeeding, and later achieved an undetectable VL.

Discussion

The proportion of breastfeeding mothers in our cohort increased from 3.2 % in 2017 to 40.4 % in 2023, reflecting a significant shift in clinical practice. This trend underscores the importance of healthcare providers staying informed about evolving evidence to support informed decision-making for MLWH. Notably, there was a decline in breastfeeding rates in 2020 in Figure 1, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. This decrease may have been influenced by disruptions in healthcare services, changes in hospital policies, and increased uncertainty regarding breastfeeding safety during the pandemic [25]. However, following this period, breastfeeding rates rebounded, suggesting a recovery in clinical support and confidence in breastfeeding practices. This recovery underscores the critical role of sustained viral suppression and close medical monitoring in ensuring safe breastfeeding practices. It aligns with guidelines from high-resource settings that permit breastfeeding under specific conditions, emphasizing the need for continuous clinical support [26], [27], [28]. The decision to breastfeed in these settings requires shared decision-making between mothers and healthcare providers to ensure individualized care and optimal outcomes. The main challenge remains optimizing breastfeeding practices for MLWH to maximize benefits while minimizing the risk of MTCT. Achieving this goal necessitates strict ART adherence, tailored interventions, and multidisciplinary support. Breastfeeding remains a significant contributor to infant HIV infections in resource-limited settings, with maternal immunosuppression, low CD4 cell counts, and breast complications such as mastitis increasing transmission risk [1], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Maternal VL is the most critical determinant in preventing transmission [34], 35]. However, the concept of “undetectable equals untransmittable” (U=U) may not fully apply to breastfeeding [36]. A systematic review reported an HIV transmission rate of 2.93 % after 12 months of breastfeeding under ART [37]. Similarly, the PROMISE study observed two transmission cases in breastfeeding mothers with VLs below 40 copies/mL, suggesting that persistent HIV exposure, local breast inflammation, or other unknown factors may contribute to residual transmission risk [6].

The importance of feeding practices is further underscored by data from a large South African intervention cohort study, which demonstrated that exclusively breastfed infants had a significantly lower risk of HIV transmission compared to those receiving mixed feeding. [38]. However, it is important to note that the mothers in this study were not receiving ART, which limits the generalizability of these findings to current clinical contexts, where maternal ART is standard [38]. In such settings, the influence of feeding practices on transmission risk is likely reduced. Nevertheless, these earlier findings provide insight into potential biological mechanisms that may still be relevant. In our own setting, where all mothers were on ART, no HIV transmissions occurred, regardless of feeding type. This supports the notion that while exclusive breastfeeding may reduce transmission risk in the absence of ART, effective maternal ART is the key protective factor in contemporary settings. One possible explanation is that exclusive breastfeeding supports gut barrier integrity, while mixed feeding especially the introduction of solid foods may increase intestinal permeability to HIV and other pathogens. This mechanism is particularly relevant in low-resource settings with increased exposure to contaminated water and infections. In contrast, in high-resource settings with access to clean water, high hygiene standards, and formula alternatives, this protective effect may be less significant. Another key concern is the increased risk of maternal breast complications such as mastitis, which has been linked to higher HIV shedding in breast milk [30], 38]. While this risk exists across all settings, midwifery-led lactation support in high-resource healthcare systems can play a crucial role in prevention and early intervention. Access to trained midwives providing tailored counseling, monitoring for early signs of inflammation, and ensuring optimal infant positioning may help reduce mastitis and related complications. Notably, in our cohort, exclusive breastfeeding was significantly associated with midwifery care (p=0.009), emphasizing the need to integrate midwifery-led support into breastfeeding recommendations for MLWH.

European guidelines on breastfeeding among MLWH remain inconsistent. The INSURE survey found that while 52 % of national guidelines still discourage breastfeeding for MLWH, 48 % allow it under specific conditions. Nearly half of respondents reported an increasing trend in breastfeeding among MLWH, highlighting the need for harmonized, evidence-based guidance across Europe [39]. Our cohort largely followed the German–Austrian Guidelines for HIV Therapy in Pregnancy and HIV-Exposed Newborns [11], which initially opposed breastfeeding but, since 2020, have supported shared decision-making under strict conditions, including sustained viral suppression, ART adherence, and close monitoring. However, eight mothers in our study, initiated breastfeeding despite receiving a new HIV diagnosis during pregnancy, and one mother was treated with a dual-drug regimen instead of the recommended three-drug regimen.

A key aspect to consider is how our cohort compares to other studies regarding breastfeeding duration. In our study, the median breastfeeding duration was 7.3 months (IQR 7.6 months), with a wide range from 0.1 to 33.9 months. Two children were still breastfeeding at the end of follow-up, one for 39 months and the other for 24 months.

When comparing this to the Swiss study (2019–2021), where 25 out of 41 ART-treated mothers breastfed with a median duration of 6.3 months (range 0.7–25.7 months), our cohort had a slightly longer median duration and a broader range, particularly with some mothers breastfeeding beyond two years [10]. The UK study presents a notably different pattern. The median breastfeeding duration was only 56 days (IQR: 23–140 days), with a range from 1 day to 2.3 years. Strikingly, 93.3 % of breastfeeding mothers in the UK cohort breastfed for 6 months or less, and 18.7 % (28 of 150) stopped within the first 7 days. This suggests that, compared to both our cohort and the Swiss study, breastfeeding durations in the UK tend to be significantly shorter. The data indicate that only a small minority of mothers breastfed beyond 6 months, whereas in our cohort, a substantial proportion breastfed for extended periods, with some continuing beyond two or even three years [40]. This suggests a much shorter breastfeeding duration compared to our cohort and the Swiss study. The differences could be attributed to variations in national guidelines, cultural attitudes toward breastfeeding among MLWH, healthcare provider recommendations, or access to lactation support. The relatively short breastfeeding duration in the UK cohort may indicate that many mothers discontinued breastfeeding early, possibly due to lack of support, or personal concerns regarding MTCT risk. However, as there is no information on the availability or continuity of postnatal breastfeeding support in this context, such interpretations should be made with caution.

This raises important questions about the long-term safety of ART exposure in breastfed infants, potential health benefits, and the need for extended clinical monitoring of both mother and child.

PNP protocols for HIV-exposed infants (HEI) also vary widely across Europe. The Penta survey highlighted significant discrepancies in risk stratification, drug selection, and prophylaxis duration. For low-risk infants, some countries do not recommend PNP, while others administer up to four weeks of ZDV. High-risk infants often receive a three-drug regimen (ZDV, lamivudine, and nevirapine), but regimen duration and dosing protocols differ [24]. In our cohort, nearly all breastfed infants (98.7 %) received ZDV regimen, though two mothers opted out of PNP after counseling. 24.7 % of infants received ZDV for longer than the recommended 14 days, possibly reflecting maternal uncertainty or misunderstanding despite prior counseling.The ongoing debate over whether PNP is always necessary for breastfed infants highlights a critical gap in current guidelines.

Despite the overall positive outcomes in our cohort, guideline-recommended monthly maternal VL monitoring during breastfeeding was not consistently implemented due to logistical challenges. Pediatricians and obstetricians cannot bill for adult blood draws, requiring MLWH to schedule separate infectious disease appointments, often necessitating travel with an infant. This raises questions about the necessity of frequent VL monitoring in ART-adherent women with sustained suppression. Instead, our approach focused on fostering trust, ensuring ART adherence, and providing social work support via phone. These real-world insights reflect the practical strengths and challenges of managing MLWH in high-resource settings, where patient-centered care plays a critical role.

Exclusive breastfeeding and longer breastfeeding duration were significantly associated with vaginal delivery compared to cesarean section or vacuum extraction (p=0.005), suggesting that delivery mode may influence breastfeeding outcomes due to maternal recovery, early skin-to-skin contact, and neonatal feeding readiness. However, our cohort size (n=77) limits generalizability. Additionally, we did not analyze ART concentrations in breast milk, preventing conclusions on potential toxicities or long-term effects. A systematic review of 24 pharmacokinetic studies suggests that breastfed infants are exposed to considerable levels of NRTIs and NNRTIs, though methodological heterogeneity limits direct comparisons [41].

Our findings emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary care, particularly midwifery-led support, in preventing MTCT and promoting safe breastfeeding among MLWH. Future research should address long-term ART exposure in breastfed infants, refine risk-adapted care models, and validate these findings in larger cohorts to inform evidence-based guidelines.

-

Research ethics: This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Charité Berlin (EA4/139/21). All data were fully pseudonymized before analysis to ensure participant confidentiality.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable. Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study and full pseudonymization of data, as approved by the Ethics Committee.

-

Author contributions: Cornelia Feiterna-Sperling and Irena Rohr conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Renate Krüger, Hannah Bethke, Jan-Peter Siedentopf, and Katharina von Weizsäcker contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript review. M. Heinrich-Rohr collected and prepared the data and conducted statistical analyses All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are stored on an institutional server and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. John, GC, Kreiss, J. Mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Epidemiol Rev 1996;18:149–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017922.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Sibiude, J, Le Chenadec, J, Mandelbrot, L, Hoctin, A, Dollfus, C, Faye, A, et al.. Update of perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in France: zero transmission for 5482 mothers on continuous antiretroviral therapy from conception and with undetectable viral load at delivery. Clin Infect Dis 2023;76:e590–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac703.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Hofacker, M, Weichert, A, Feiterna-Sperling, C, von Weizsacker, K, Siedentopf, JP, Heinrich-Rohr, M, et al.. Prenatal ultrasound screening and pregnancy outcomes in HIV-positive women in Germany: results from a retrospective single-center study at the Charite-Universitatsmedizin Berlin. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2024;310:1385–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-07286-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Meek, JY, Noble, L. Section on B. Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2022;150. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057988.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Transmission PoToHDPaPoP. Recommendations for the use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2024. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal/whats-new-guidelines.Search in Google Scholar

6. Flynn, PM, Taha, TE, Cababasay, M, Fowler, MG, Mofenson, LM, Owor, M, et al.. Prevention of HIV-1 transmission through breastfeeding: efficacy and safety of maternal antiretroviral therapy versus infant nevirapine prophylaxis for duration of breastfeeding in HIV-1-Infected women with high CD4 cell count (IMPAACT PROMISE): a randomized, open-label, clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:383–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000001612.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. World Health Organization. Electronic address swi. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

8. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. WHO collaborative study team on the role of breastfeeding on the prevention of infant mortality. Lancet 2000;355:451–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10841125/.10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06260-1Search in Google Scholar

9. Kahlert, C, Aebi-Popp, K, Bernasconi, E, Martinez de Tejada, B, Nadal, D, Paioni, P, et al.. Is breastfeeding an equipoise option in effectively treated HIV-infected mothers in a high-income setting? Swiss Med Wkly 2018;148:w14648. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14648.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Crisinel, PA, Kusejko, K, Kahlert, CR, Wagner, N, Beyer, LS, De Tejada, BM, et al.. Successful implementation of new Swiss recommendations on breastfeeding of infants born to women living with HIV. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2023;283:86–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2023.02.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. S2k-Leitlinie zur HIV-Therapie in der Schwangerschaft und bei HIV-exponierten Neugeborenen: AWMF; 2020 Available from: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/055-002l_S2k_HIV-Therapie-Schwangerschaft-und-HIV-exponierten_Neugeborenen_2020-10-verlaengert.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

12. Kuhn, L, Kim, HY, Walter, J, Thea, DM, Sinkala, M, Mwiya, M, et al.. HIV-1 concentrations in human breast milk before and after weaning. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:181ra51. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3005113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Thea, DM, Aldrovandi, G, Kankasa, C, Kasonde, P, Decker, WD, Semrau, K, et al.. Post-weaning breast milk HIV-1 viral load, blood prolactin levels and breast milk volume. AIDS 2006;20:1539–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000237370.49241.dc.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Kuhn, L, Aldrovandi, GM, Sinkala, M, Kankasa, C, Semrau, K, Mwiya, M, et al.. Effects of early, abrupt weaning on HIV-free survival of children in Zambia. N Engl J Med 2008;359:130–41. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa073788.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Nachega, JB, Uthman, OA, Anderson, J, Peltzer, K, Wampold, S, Cotton, MF, et al.. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2012;26:2039–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0b013e328359590f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Hodel, EM, Marzolini, C, Waitt, C, Rakhmanina, N. Pharmacokinetics, placental and breast milk transfer of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant and lactating women living with HIV. Curr Pharm Des 2019;25:556–76. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612825666190320162507.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Shapiro, RL, Holland, DT, Capparelli, E, Lockman, S, Thior, I, Wester, C, et al.. Antiretroviral concentrations in breast-feeding infants of women in Botswana receiving antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis 2005;192:720–7. https://doi.org/10.1086/432483.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Benaboud, S, Pruvost, A, Coffie, PA, Ekouevi, DK, Urien, S, Arrive, E, et al.. Concentrations of tenofovir and emtricitabine in breast milk of HIV-1-infected women in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, in the ANRS 12109 TEmAA Study, Step 2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55:1315–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00514-10.Search in Google Scholar

19. Mugwanya, KK, Hendrix, CW, Mugo, NR, Marzinke, M, Katabira, ET, Ngure, K, et al.. Pre-exposure prophylaxis use by breastfeeding HIV-uninfected women: a prospective short-term study of antiretroviral excretion in breast milk and infant absorption. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002132.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Aebi-Popp, K, Kahlert, CR, Crisinel, PA, Decosterd, L, Saldanha, SA, Hoesli, I, et al.. Transfer of antiretroviral drugs into breastmilk: a prospective study from the Swiss Mother and Child HIV Cohort Study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022;77:3436–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkac337.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Feiterna-Sperling, C, Bukkems, VE, Teulen, MJA, Colbers, AP, network, P. Low raltegravir transfer into the breastmilk of a woman living with HIV. AIDS 2020;34:1863–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000002624.Search in Google Scholar

22. ASHM (Australasian Society for HIV VHaSHM. Antiretroviral therapy for newborns at risk of HIV infection: ASHM 2023. Available from: https://hiv.guidelines.org.au/arv-pediatric/newborns-hiv/.Search in Google Scholar

23. Dr Sarah Sparrow, NC, Nhs, GGC, Chair, NNNBBVDPS. Management of Infants exposed to HIV in pregnancy 2024. https://perinatalnetwork.scot/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Management-of-Infants-exposed-to-HIV-in-pregnancy-Guideline-2024.pdf [Accessed 17 Apr 2025].Search in Google Scholar

24. Fernandes, G, Chappell, E, Goetghebuer, T, Kahlert, CR, Ansone, S, Bernardi, S, et al.. HIV postnatal prophylaxis and infant feeding policies vary across Europe: results of a Penta survey. HIV Med 2025;26:207–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.13723.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Faria, APV, Silva, T, Abreu, MNS, Canastra, MA, Fernandes, AC, Martins, EF, et al.. Obstetric outcomes in breastfeeding women in the first hour of delivery before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025;25:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06975-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant individuals with HIV: prevention of perinatal HIV transmission. 2024. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/perinatal-hiv/guidelines-perinatal.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

27. Abuogi, L, Noble, L, Smith, C, Committee On, P, Adolescent, HIV, Section On, B, et al.. Infant feeding for persons living with and at risk for HIV in the United States: clinical report. Pediatrics 2024;153. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-066843.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. (EKSG) EKfsG. Empfehlungen der EKSG zur Mutter-Kind-Übertragung von HIV 2018. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/p-und-p/richtlinien-empfehlungen/eksg-mtct-hiv.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

29. UNAIDS. Start free stay free AIDS free - 2019 report 2019. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/20190722_UNAIDS_SFSFAF_2019.Search in Google Scholar

30. John, GC, Nduati, RW, Mbori-Ngacha, DA, Richardson, BA, Panteleeff, D, Mwatha, A, et al.. Correlates of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission: association with maternal plasma HIV-1 RNA load, genital HIV-1 DNA shedding, and breast infections. J Infect Dis 2001;183:206–12. https://doi.org/10.1086/317918.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Semba, RD, Kumwenda, N, Hoover, DR, Taha, TE, Quinn, TC, Mtimavalye, L, et al.. Human immunodeficiency virus load in breast milk, mastitis, and mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis 1999;180:93–8. https://doi.org/10.1086/314854.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Semba, RD, Kumwenda, N, Taha, TE, Hoover, DR, Quinn, TC, Lan, Y, et al.. Mastitis and immunological factors in breast milk of human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J Hum Lactation 1999;15:301–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/089033449901500407.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Willumsen, JF, Filteau, SM, Coutsoudis, A, Newell, ML, Rollins, NC, Coovadia, HM, et al.. Breastmilk RNA viral load in HIV-infected South African women: effects of subclinical mastitis and infant feeding. AIDS 2003;17:407–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200302140-00015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Shapiro, RL, Hughes, MD, Ogwu, A, Kitch, D, Lockman, S, Moffat, C, et al.. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2282–94. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa0907736.Search in Google Scholar

35. Behrens, GMN, Aebi-Popp, K, Babiker, A. Close to zero, but not zero: what is an acceptable HIV transmission risk through breastfeeding? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2022;89:e42. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000002887.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Waitt, C, Low, N, Van de Perre, P, Lyons, F, Loutfy, M, Aebi-Popp, K. Does U=U for breastfeeding mothers and infants? Breastfeeding by mothers on effective treatment for HIV infection in high-income settings. Lancet HIV 2018;5:e531–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(18)30098-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Bispo, S, Chikhungu, L, Rollins, N, Siegfried, N, Newell, ML. Postnatal HIV transmission in breastfed infants of HIV-infected women on ART: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21251. https://doi.org/10.7448/ias.20.1.21251.Search in Google Scholar

38. Coovadia, HM, Rollins, NC, Bland, RM, Little, K, Coutsoudis, A, Bennish, ML, et al.. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: an intervention cohort study. Lancet 2007;369:1107–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60283-9.Search in Google Scholar

39. Keane, A, Lyons, F, Aebi-Popp, K, Feiterna-Sperling, C, Lyall, H, Martinez Hoffart, A, et al.. Guidelines and practice of breastfeeding in women living with HIV-Results from the European INSURE survey. HIV Med 2024;25:391–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.13583.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. (UKHSA) UHSA. ISOSS HIV report 2022. London, UK: UK Government; 2022.Search in Google Scholar

41. Waitt, CJ, Garner, P, Bonnett, LJ, Khoo, SH, Else, LJ. Is infant exposure to antiretroviral drugs during breastfeeding quantitatively important? A systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacokinetic studies. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:1928–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv080.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Perinatal responsibility in a fragmented world: reflections from the 2024 international academy of perinatal medicine New York meeting

- Corner of Academy

- Global education – impressive results of Ian Donald School

- Cicero’s universal law: a timeless guide to reproductive justice

- Enhancing patient understanding in obstetrics: the role of generative AI in simplifying informed consent for labor induction with oxytocin

- Faculty retention in academic OB/GYN: comprehensive strategies and future directions

- Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn: pregnant person’s and fetal immune systems interaction

- Viability of extremely premature neonates: clinical approaches and outcomes

- Reviews

- Standardizing cord clamping: bridging physiology and recommendations from leading societies

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in pregnancy: a comprehensive review

- Mini Review

- Looking for a needle in a haystack: a case study of rare disease care in neonatology

- Opinion Paper

- Hemorrhagic placental lesions on ultrasound: a continuum of placental abruption

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Amnioreduction safety in singleton pregnancies; systematic review and meta-analysis

- Outpatient management of prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM) at term – a re-evaluation and contribution to the current debate

- Breastfeeding in HIV-positive mothers under optimized conditions: ‘real-life’ results from a well-resourced healthcare setting

- Intervention using the Robson classification as a tool to reduce cesarean section rates in six public hospitals in Brazil

- Short Communication

- Continuous positive airway pressure vs. high velocity nasal cannula for weaning respiratory support of preterm infants

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Perinatal responsibility in a fragmented world: reflections from the 2024 international academy of perinatal medicine New York meeting

- Corner of Academy

- Global education – impressive results of Ian Donald School

- Cicero’s universal law: a timeless guide to reproductive justice

- Enhancing patient understanding in obstetrics: the role of generative AI in simplifying informed consent for labor induction with oxytocin

- Faculty retention in academic OB/GYN: comprehensive strategies and future directions

- Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn: pregnant person’s and fetal immune systems interaction

- Viability of extremely premature neonates: clinical approaches and outcomes

- Reviews

- Standardizing cord clamping: bridging physiology and recommendations from leading societies

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in pregnancy: a comprehensive review

- Mini Review

- Looking for a needle in a haystack: a case study of rare disease care in neonatology

- Opinion Paper

- Hemorrhagic placental lesions on ultrasound: a continuum of placental abruption

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Amnioreduction safety in singleton pregnancies; systematic review and meta-analysis

- Outpatient management of prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM) at term – a re-evaluation and contribution to the current debate

- Breastfeeding in HIV-positive mothers under optimized conditions: ‘real-life’ results from a well-resourced healthcare setting

- Intervention using the Robson classification as a tool to reduce cesarean section rates in six public hospitals in Brazil

- Short Communication

- Continuous positive airway pressure vs. high velocity nasal cannula for weaning respiratory support of preterm infants