Abstract

Objectives

Cannabis use disorder (CUD) among pregnant women is increasing, yet limited information exists on admissions for treatment in this population. This study examined trends in CUD admissions among pregnant women in publicly funded U.S. treatment facilities from 2000 to 2021.

Methods

Using the Treatment Episode Data Set-Admissions, we analyzed 33,729 admissions of pregnant women with CUD. Descriptive statistics were used to assess patterns by race/ethnicity, age, and co-substance use.

Results

CUD admissions increased 2.7-fold, from 2.3 % in 2000 to 6.2 % in 2009, followed by a decrease to 4.3 % in 2014, a peak of 6.7 % in 2018, and a decline to 3.0 % in 2021. In 2021, racial/ethnic disparities were noted, with higher proportions of admissions among White (48.8 %) and Black (32.5 %) non-Hispanic women compared to Hispanic women (9.6 %). Admissions decreased for women aged ≤20 years old (y/o), but increased for women aged ≥30 y/o from 2010 to 2021, with the highest prevalence in those aged 21–29 y/o. Co-substance use, particularly narcotics, stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens, was prevalent from 2017 to 2021.

Conclusions

CUD admissions among pregnant women have fluctuated over two decades, with variations by race/ethnicity and age. These findings highlight the need for tailored interventions and ongoing adaptation of treatment services for pregnant women with CUD.

Cannabis use disorder (CUD), defined as “a problematic pattern of cannabis use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress” [1], has increased over time among pregnant women. Estimates indicate a 5.06-fold rise in CUD from 1993 to 2014 in this population [2]. Infants born to mothers with CUD during pregnancy have higher odds of preterm birth, low birth weight, and mortality [3]. Despite these adverse outcomes and the rising rates of CUD, prevention and intervention programs for pregnant women remain limited [3].

Only 30 % of pregnant women admitted to treatment for CUD complete treatment [4], and co-substance use is common. About 40.8 % of pregnant women admitted to treatment for the first time reported cannabis as their primary drug of choice [5]. However, data on CUD treatment admission trends in pregnant women remain limited. This study analyzed admissions for CUD among pregnant women in publicly funded treatment facilities in the U.S. from 2000 to 2021.

Data were analyzed from the 2000–2021 Treatment Episode Data Set-Admissions (TEDS-A) of 33,729 admissions of pregnant women with CUD. TEDS-A provides data from federally funded state-licensed treatment facilities including detoxification (hospital inpatient and free-standing residential), rehabilitation/residential (hospital-based), ambulatory services (intensive outpatient), and State psychiatric hospitals, among others. The sample was restricted to admissions of pregnant women diagnosed with CUD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases [6]. Maternal age was divided into ≤20, 21–29, and ≥30 years old. Descriptive statistics examined the distribution of CUD admissions by age, race/ethnicity, co-substance use, and over time. Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study, as it was deemed not human subjects research.

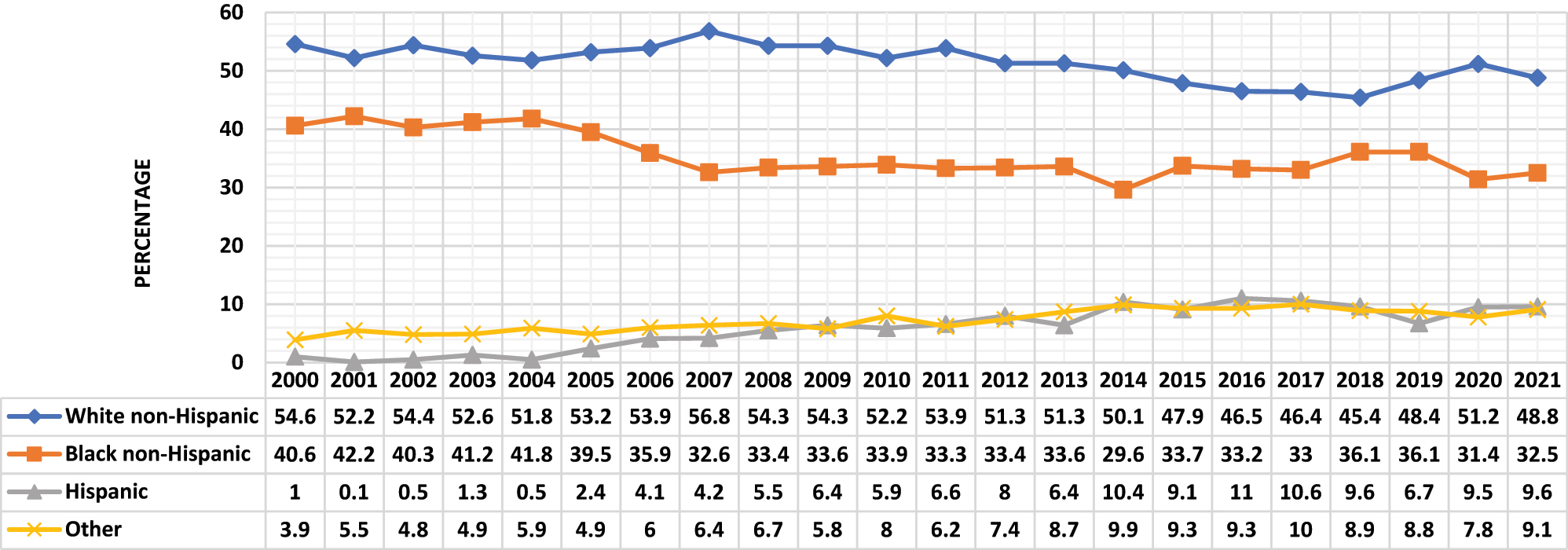

Results showed a 2.7-fold increase in CUD admissions, from 2.3 % in 2000 to 6.2 % in 2009, followed by a decrease to 4.3 % in 2014, a peak of 6.7 % in 2018, and a decline to 3.0 % in 2021. Racial/ethnic disparities were evident, with fewer admissions in 2021 among non-Hispanic White (48.8 %) and Black (32.5 %) women compared to Hispanic (9.6 %) and Other (9.1 %) women. While admissions among White women decreased from 52.2 % in 2010 to 45.4 % in 2018, they peaked again at 51.2 % in 2020. CUD-related admissions among Black women increased from 29.6 % in 2014 to 36.1 % in 2018/2019. Hispanic admissions rose 1.4-fold between 2019 (6.7 %) and 2021 (9.6 %).

Admissions for pregnant women aged ≤20 years declined since 2011 but briefly spiked in 2020 (19.2 %) before falling to 14.7 % in 2021. Admissions in women aged≥30 increased 2.3-fold from 12.2 % in 2010 to 28.1 % in 2021, while admissions among women aged 21–29 years decreased from 62.1 % in 2018 to 57.2 % in 2021 (Figure 1).

Co-substance use was prevalent, peaking in 2018 and declining since 2019, except for inhalants, which spiked in 2020. Narcotics, stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens were the most common co-substances used between 2017 and 2021. Narcotics use increased steadily until 2017 but has since declined, while the use of hallucinogens, inhalants, and stimulants varied annually in CUD-related admissions (Figure 2).

The increase in CUD treatment admissions among pregnant women aged 21+ and 30+ may reflect broader societal trends, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic when cannabis sales surged in states with legal cannabis [8], 9]. Women in these age groups may have experienced added stressors – such as economic challenges, caregiving responsibilities, or heightened anxiety – that contributed to cannabis use as a coping mechanism. Pregnant women aged 30+ may contributing to higher rates of CUD and treatment admissions.

Broader trends suggest that pregnant women may follow or diverge from general treatment trends. Cannabis use increased during the pandemic, likely leading to more admissions across all age groups. However, pregnant women may be more vulnerable due to pregnancy-related conditions such as nausea and anxiety, which some use cannabis to manage. Stigma around cannabis use during pregnancy may also delay treatment-seeking.

Cannabis use disorder admissions to treatment among pregnant women by race/ethnicity, TEDS-A 2000–2021. Maternal race/ethnicity was classified as non-Hispanic White, Black, Hispanic, or Other.

![Figure 2:

Co-substance use among cannabis use disorder admissions in pregnant women by race/ethnicity, TEDS-A 2000–2021. Co-substance use was classified into narcotics, stimulants, depressants, hallucinogens, inhalants, and other drugs based on Drug Enforcement Administration categories [7].](/document/doi/10.1515/jpm-2024-0487/asset/graphic/j_jpm-2024-0487_fig_002.jpg)

Co-substance use among cannabis use disorder admissions in pregnant women by race/ethnicity, TEDS-A 2000–2021. Co-substance use was classified into narcotics, stimulants, depressants, hallucinogens, inhalants, and other drugs based on Drug Enforcement Administration categories [7].

Perceptions of cannabis as a harmless alternative for managing pregnancy-related symptoms, such as nausea and anxiety, have increased in recent years [10]. Cannabis retailers and budtenders are often viewed as trusted sources of information, particularly in states where cannabis is legal [8], 9]. However, these perceptions may not account for the potential risks of CUD. Cannabis potency has also risen over the last decade, with higher THC concentrations in legal markets [11]. This could contribute to higher rates of addiction, especially in pregnant women who may not be aware of the risks, further driving treatment admissions.

The decline in CUD treatment admissions since 2021 may reflect several factors. First, fewer treatment slots may have been available during the pandemic, with facilities prioritizing severe substance use disorders, like opioid use disorder. Societal normalization of cannabis use and perceptions of its harmlessness may also reduce the likelihood of pregnant women recognizing cannabis use as problematic enough to seek treatment.

Polysubstance use was common among pregnant women with CUD, with co-occurring narcotics, stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens present in many admissions, particularly from 2017 to 2021. This raises the question of whether CUD alone is driving treatment-seeking behavior or if the co-use of other substances plays a larger role. Many women admitted for CUD may also have significant co-substance use, which could be the primary reason for seeking treatment. Social desirability bias may also impact CUD treatment admissions. Pregnant women may underreport cannabis use or avoid seeking treatment due to fears of legal repercussions or stigma. Studies show that pregnant women are often less likely to disclose drug use, especially in states where there are legal consequences for substance use during pregnancy [10]. This underreporting may skew the true rates of CUD among pregnant women seeking treatment.

The study identified significant temporal variations from 2000 to 2021 in CUD admissions, as well as differences by age and racial/ethnic groups. The initial increase from 2000 to 2009 could be linked to early medical cannabis legalization in several states, which may have set the stage for wider acceptance and use. The subsequent decrease from 2009 to 2014 could be tied to heightened public health campaigns raising awareness about cannabis use risks during pregnancy, resulting in lower usage or underreporting [8], 9].

The peak in 2018 aligns with the enactment of recreational cannabis laws across several states, which likely contributed to the rise in CUD admissions [11]. Research by Lee et al. [9] found higher cannabis use rates following legalization among pregnant women undergoing universal drug screening. The subsequent decline in CUD admissions could indicate shifting attitudes toward cannabis, with some viewing it as less harmful [10], 12]. Inconsistent screening and counseling for cannabis use by healthcare providers may also play a role [13]. The decline in CUD admissions from 2018 to 2021 may reflect changing cannabis use patterns, perceptions of harm, policy shifts, or external factors influencing treatment-seeking and availability.

The rise in CUD admissions among women aged 30+ may indicate delayed treatment-seeking among older women. The Affordable Care Act’s implementation in 2010, which expanded healthcare coverage, could have increased treatment-seeking behavior, affecting admission rates [14]. Younger women’s attitudes toward cannabis as a harmless drug may affect their treatment-seeking behavior [12]. The disparities in CUD admissions among racial/ethnic groups call for culturally tailored interventions. The higher prevalence of CUD admissions among non-Hispanic White and Black women, compared to Hispanic and Other groups, suggests potential differences in access to treatment, stigma, or social determinants of health. Further research should explore these disparities to inform targeted prevention and treatment strategies.

Polysubstance use remains a significant concern, highlighting the need for integrated treatment approaches that address multiple substance use disorders. Although co-substance use in CUD-related admissions has declined since 2019, the significant co-substance use underscores the complexity of substance use disorders in pregnant women. The increased use of inhalants in 2020 may reflect pandemic-related changes in access [15]. Interventions should address both cannabis and polysubstance use to mitigate impacts on maternal and fetal health. Comprehensive care models integrating obstetric, addiction, and mental health services could improve outcomes for this vulnerable population.

This study has limitations. First, the data are descriptive and useful for hypothesis generation but not for testing. The data are also limited to publicly funded facilities, which may restrict generalizability to all pregnant women with CUD in the U.S. Additionally, the data are limited to women who sought treatment, and prospective data are lacking to assess long-term trends and outcomes. Finally, limited information on socioeconomic factors and access to care could influence both CUD occurrence and treatment-seeking.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into CUD treatment trends among pregnant women from 2001 to 2021. Continuous monitoring of CUD treatment admissions, as societal attitudes and cannabis legalization evolve, is crucial. Clinicians and policymakers should remain informed to adapt treatment services effectively. Emphasizing the risks of cannabis use during pregnancy and promoting treatment resources are key to addressing CUD in this population.

In conclusion, this study highlights significant temporal trends and demographic variations in CUD admissions among pregnant women in publicly funded facilities. While overall admissions have declined since 2018, racial/ethnic disparities and high rates of polysubstance use remain significant public health challenges. Future research should investigate factors influencing treatment-seeking and develop targeted interventions to support pregnant women with CUD, improving maternal and child health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary work was presented at the American College of Preventive Medicine Annual Meeting, Washington DC, April 2024.

-

Research ethics: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. PK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation. MM: Conceptualization, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. LS, AF, CH: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Professor Hennekens also declares that he serves as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC; to the United States Food and Drug Administration, and UpToDate; receives royalties for authorship or editorship of 3 textbooks; has an investment management relationship with the West-Bacon Group within Truist Investment Services, which has discretionary investment authority; does not own any common or preferred stock in any pharmaceutical or medical device company.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2022. 5th ed., text rev.10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787Search in Google Scholar

2. Shi, Y, Zhong, S. Trends in cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in the U.S., 1993–2014. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:245–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4201-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Shi, Y, Zhu, B, Liang, D. The associations between prenatal cannabis use disorder and neonatal outcomes. Addiction 2021;116:3069–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15467 [Epub 2021 Apr 22].Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Kitsantas, P, Gimm, G, Aljoudi, SM. Treatment outcomes among pregnant women with cannabis use disorder. Addict Behav 2023;144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107723 [Epub 2023 Apr 17].Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Washio, Y, Mark, K, Terplan, M. Characteristics of pregnant women reporting cannabis use disorder at substance use treatment entry. J Addict Med 2018;12:395–400. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000424.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 national survey on drug use and health (HHS publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH series H55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/.Search in Google Scholar

7. U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Drugs of abuse, A DEA resource guide; 2022. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/2022_DOA_eBook_File_Final.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

8. Volkow, ND, Han, B, Compton, WM, McCance-Katz, EF. Self-reported medical and nonmedical cannabis use among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA 2019;322:167–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.7982.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Lee, E, Pluym, ID, Wong, D, Kwan, L, Varma, V, Rao, R. The impact of state legalization on rates of marijuana use in pregnancy in a universal drug screening population. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:1660–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1765157.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Satti, MA, Reed, EG, Wenker, ES, Mitchell, SL, Schulkin, J, Power, M, et al.. Factors that shape pregnant women’s perceptions regarding the safety of cannabis use during pregnancy. J Cannabis Res 2022;4:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-022-00128-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Farrelly, KN, Wardell, JD, Marsden, E, Scarfe, ML, Najdzionek, P, Turna, J, et al.. The impact of recreational cannabis legalization on cannabis use and associated outcomes: a systematic review. Subst Abuse 2023;17. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218231172054.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Kitsantas, P, Aljoudi, SM, Sacca, L. Perception of risk of harm from cannabis use among women of reproductive age with disabilities. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2024;9:e1615-22. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2023.0199. Published online March 5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Kitsantas, P, Pursell, SR. Are health care providers caring for pregnant and postpartum women ready to confront the perinatal cannabis use challenge? Am J Perinatol 2024;41:e3249–54. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1777669.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Andrews, CM, Pollack, HA, Abraham, AJ, Grogan, CM, Bersamira, CS, D’Aunno, T, et al.. Medicaid coverage in substance use disorder treatment after the affordable care act. J Subst Abuse Treat 2019;102:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.04.002 [Epub 2019 Apr 9].Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Hoots, BE, Li, J, Hertz, MF, Esser, M, Rico, A, Zavala, E, et al.. Alcohol and other substance use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among high school students – youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Suppl 2023;72:84–92. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7201a10.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?