Bacteriuria in pregnancy varies with the ambiance: a retrospective observational study at a tertiary hospital in Doha, Qatar

-

Fathima Minisha

, Mahmoud Mohamed

Abstract

Objectives

To explore the influence of ambient temperature and humidity on significant bacteriuria (SB) and urinary bacterial isolates in pregnant women.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted in the sole tertiary-care hospital in Doha, Qatar. A sample of 1588 pregnant women delivering between June 2012 and March 2013 was randomly selected. Meteorological variables including ambient average daily temperature and humidity were sourced from online meteorological data, and patient information such as demographic data, urine culture results and bacterial isolates were collected from patient files. The receptor operative curve (ROC) analysis was used to determine the cutoff for temperature and humidity. Statistical analyses of associations between SB and bacterial isolates with respect to the ambient temperature and humidity were performed using Pearson’s correlation, the chi-square (χ2) test and the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results

Of the 21.24% positive cultures, 11.25% had SB. SB showed a significant strong positive (r = +0.677, n = 17, P = 0.003) and moderate negative (r = −0.587, n = 17, P = 0.013) correlation with average monthly temperature and humidity, respectively, with doubling of rates noted with temperatures ≥35°C (11.3% vs. 3.6%; P < 0.0001) and humidity ≤50% (10.6% vs. 3.2%; P < 0.0001). Escherichia coli and Group B Streptococcus (GBS) were the most common isolates.

Conclusion

This is the first study in this region that demonstrates maternal risk with SB, with ambient temperatures of ≥35°C and humidity ≤50%. The effect of these variables on the growth of various urinary bacteria has also been shown.

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common infection in young healthy pregnant women, and it is associated with significant maternal morbidity [1]. Approximately, a third of untreated bacteriuria can progress to pyelonephritis. This is promoted by immunosuppression, anatomical and physiological changes of pregnancy, and other factors such as maternal age, socioeconomic status, sexual activity, urinary tract anomalies and systemic disease [2].

The influence of environmental factors on human health is recognized as a significant contribution to a range of clinical morbidities. The incidence of infectious diseases is known to vary with the seasons, mainly due to changes in the virulence of organisms in relation to temperature and humidity, human behavior and physiology [3]. However, the impact of climatic patterns on UTI, specifically in pregnant women, has not been adequately studied. A retrospective analysis of 3221 house calls in Greece showed an increase due to urinary tract infective symptoms during higher temperatures and decreased humidity in men and women [4]. A longitudinal analysis conducted in the UK showed autumnal seasonality for UTI consultation in primary care demonstrated over 7 years [5]. However, a retrospective study done in 1132 pregnant women in Iran showed more than 50% of infections occurring in winter [6]. The inconsistencies reported are more likely due to methodological flaws.

The most common organism causing UTI in females worldwide is Escherichia coli, followed by coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Klebsiella pneumoniae with Group B hemolytic Streptococci (GBS) having clinical importance [2]. A seasonal variation in E. coli-associated blood stream infection has been studied with peaks demonstrated in summers [7], [8].

In Qatar, a Middle Eastern country where extremes of ambient temperature and humidity occur, the impact of climate on community-acquired infections is not established. We believe this is the first study to report the relationship between weather conditions and bacteriuria in pregnancy in this region, which may inform a public health policy and local medical management of bacteriuria.

Materials and methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted in the Women’s Wellness and Research Centre (WWRC), Doha, Qatar, the sole tertiary-care setting in the country, delivering an average of 16,788 women annually. A random selection of 1588 pregnant women, from a total of 14,955, who delivered between June 2012 and March 2013, was made. The sample size was calculated based on the prevalence of bacteriuria of 10% previously reported in 2009 [9]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Research Strategy and Assurance committee. As data used for analysis were anonymized, exemption from formal ethical approval was granted by the Medical Research Centre, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar (IRB number 14277, July 2014) and was conducted in compliance with the Supreme Council of Health and ICH good clinical practice guidelines.

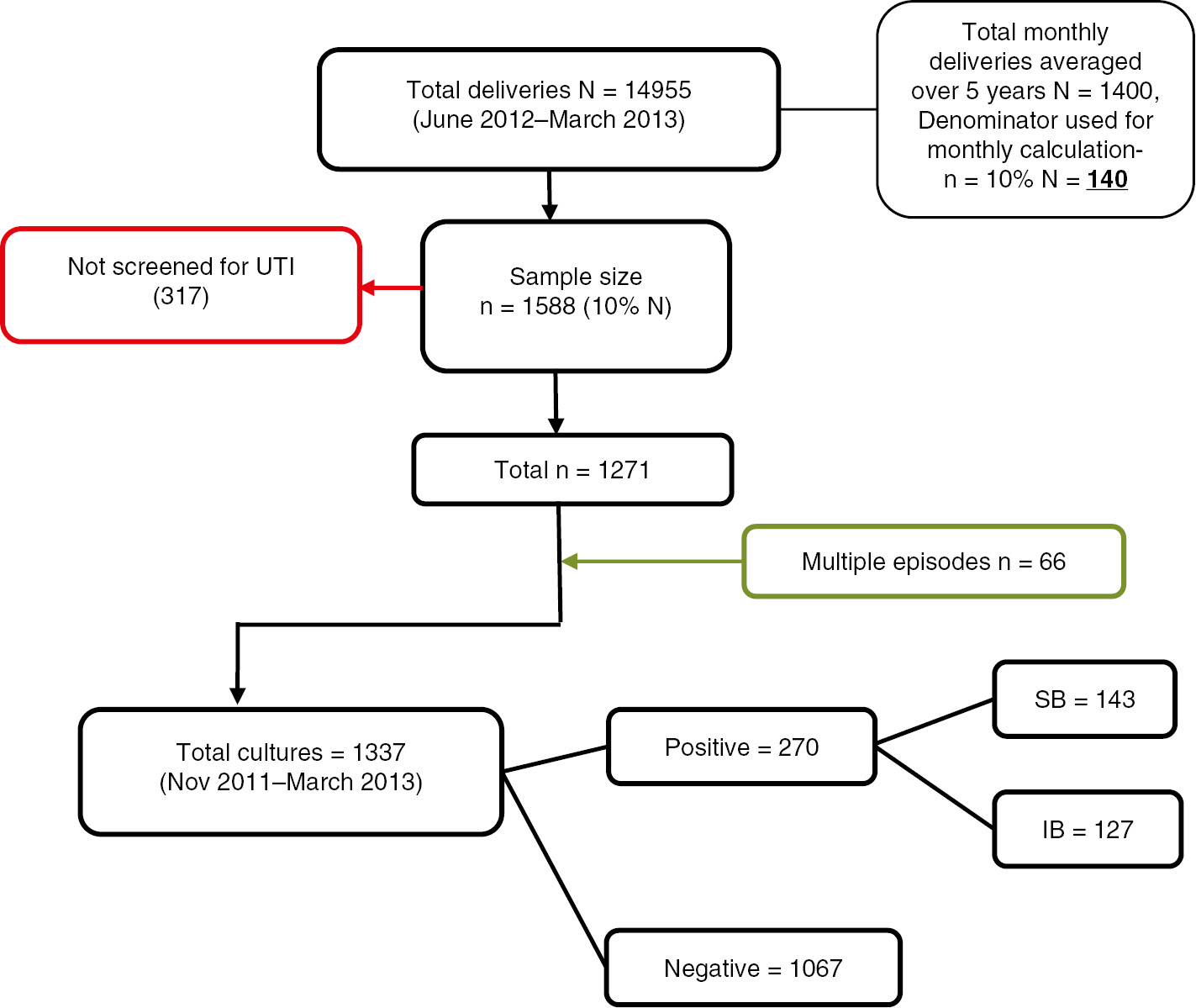

Patients not screened (n=317) during pregnancy and who had pregnancies lasting less than 20 weeks’ gestation [period of viability as per the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)] were excluded from the study. Urine cultures performed before the index pregnancy or reported more than 7 days after the date of delivery were excluded. More than one culture-positive result for the same patient was recorded as an additional episode of bacteriuria (Figure 1).

Flowsheet applied for sample selection.

The basic patient demographics of age, nationality and gestational age at delivery were recorded. Urinary culture results, date of sample collection, the trimester of pregnancy in which the culture was positive and organism isolates were obtained from electronic patient charts and the hospital medical records. The women usually book their pregnancies in primary health care centers (PHCCs), where a routine urine culture is done in the first trimester. The samples collected from these PHCCs are sent to the same laboratory in our tertiary hospital for analysis. Due to linked electronic files, these results can be accessed as well. Apart from the routine screening upon booking, cultures are also done in case they present with symptoms of infection, or if they present directly to the tertiary hospital in any of the trimesters.

The samples were collected in bottles with boric acid preservative ensuring bacteriostasis for up to 48 h of sample collection, maintaining specimen quality and prevention of overgrowth of organisms [10]. The hospital microbiology laboratory defines positive urine cultures as midstream clean catch urine culture results that quantified any one organism in colony-forming units/mL (cfu/mL). In this study, isolates of one or two organisms in quantities of ≥105 cfu/mL were labelled as significant bacteriuria (SB). Cultures reporting one or two isolates in quantities <105 cfu/mL were classified as insignificant bacteriuria (IB). Samples are labelled by the laboratory as mixed growth due to contamination if they isolate more than two organisms in any quantity, with the advice to repeat the urine culture under aseptic precautions.

The mean monthly temperature and humidity were sourced from timeanddate.com, one of the top most sites for weather services in the world, which provides weather data from weather stations at airports and stations run by the World Meteorological Association. The site calculates the mean daily highest and lowest temperature and humidity for each month. The average of this is calculated as the mean monthly temperature and humidity [11]. The information sourced from this site was crosschecked with the local meteorological department (Qatar meteorological department), which records the weather conditions as felt at the Doha International Airport.

The period prevalence of positive cultures and SB were calculated by dividing the total number of episodes by the total sample population. The average monthly delivery rate over 5 years was sourced from the medical records, and 10% of this was used as the denominator to calculate the percentage of SB per month according to sample size calculation (Figure 1). The monthly ambient temperature and humidity were correlated with the percentage of SB per month using Pearson’s correlation. The cutoffs where there was significant difference in the percentage of SB were determined by the receptor operative curve (ROC) analysis for temperature (≥35°C) and humidity (≤50%). The association between temperatures, humidity with total percentages of SB, E. coli and GBS was analyzed using the chi-square (χ2) test. The comparison of the median monthly temperatures at which each bacteria were isolated was done using the Kruskal-Wallis test and presented as a box plot. A P value of <0.05 denoted statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA) after data cleaning and regrouping as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

Out of the 1588 cases selected, 1271 were screened for bacteriuria. There were 270 positive urine cultures (including 66 repeat episodes) of which 143 had SB, which gives a prevalence of 21.24% and 11.25%, respectively. The average monthly delivery rate over 5 years in the hospital was 1400, so the denominator used for calculation of the percentage of SB per month was 140 (Figure 1).

The women belonged to 56 different nationalities, of which Qatari nationals represented the greatest proportion (29.18%). In women with SB, the proportions of Tunisians (18.18%), Egyptians (17.95%) and Qataris (14.29%) were the highest, with 58.74% between 26 and 35 years of age. The majority of these cultures were detected in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy (83.20%) with most delivering at term (91.60%). Escherichia coli and GBS were equally prevalent at 37.06% and 37.76%, respectively, in these samples (Table 1).

Demographics and bacterial isolates.

| Variable | Total sample N=1271 | SB N=143 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %(n/N) | n | %(n/N) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| ≤25 | 353 | 27.78 | 43 | 30.00 |

| 26–35 | 733 | 57.76 | 84 | 58.74 |

| >35 | 185 | 14.55 | 16 | 11.18 |

| Gestational age at delivery | ||||

| Up to 36 completed weeks | 87 | 6.84 | 12 | 8.39 |

| Term | 1184 | 93.15 | 131 | 91.60 |

| Total positive N=270 | SB N=143 | |||

| N | %(n/N) | n | %(n/N) | |

| Trimester | ||||

| First | 41 | 15.18 | 24 | 16.78 |

| Second | 80 | 29.62 | 47 | 32.86 |

| Third | 149 | 55.19 | 72 | 50.34 |

| Bacterial isolate | ||||

| E. coli | 65 | 24.07 | 53 | 37.06 |

| GBS | 131 | 48.51 | 54 | 37.76 |

| Klebsiella | 24 | 8.88 | 22 | 15.4 |

| CoN Staphylococcus | 8 | 2.96 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Lactobacillus | 9 | 3.33 | 3 | 2.09 |

| Enterococcus | 9 | 3.33 | 5 | 3.49 |

| Pseudomonas | 5 | 1.85 | 1 | 0.69 |

CoN, coagulase-negative; GBS, Group B Streptococcus; n, number of observations; SB, significant bacteriuria.

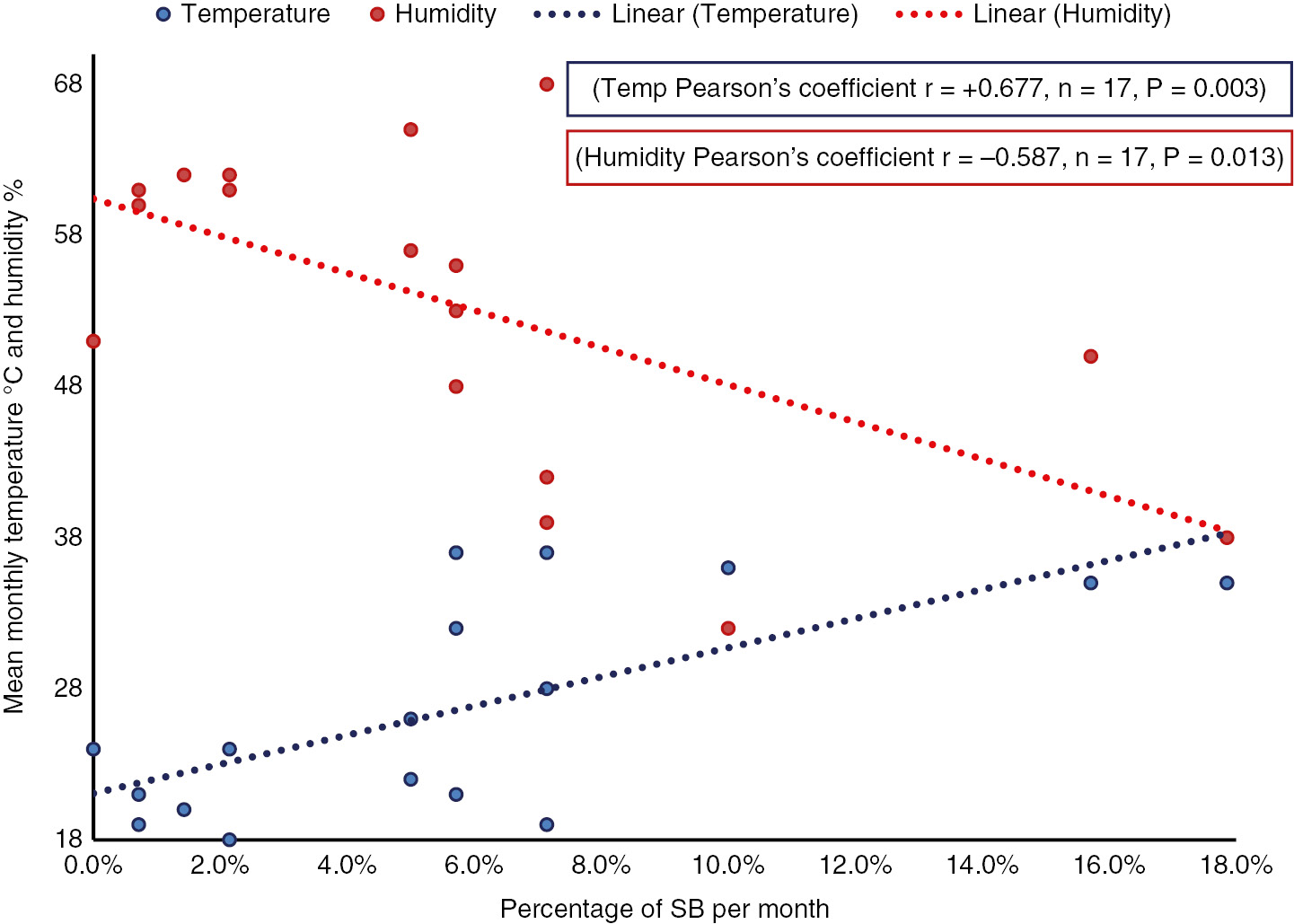

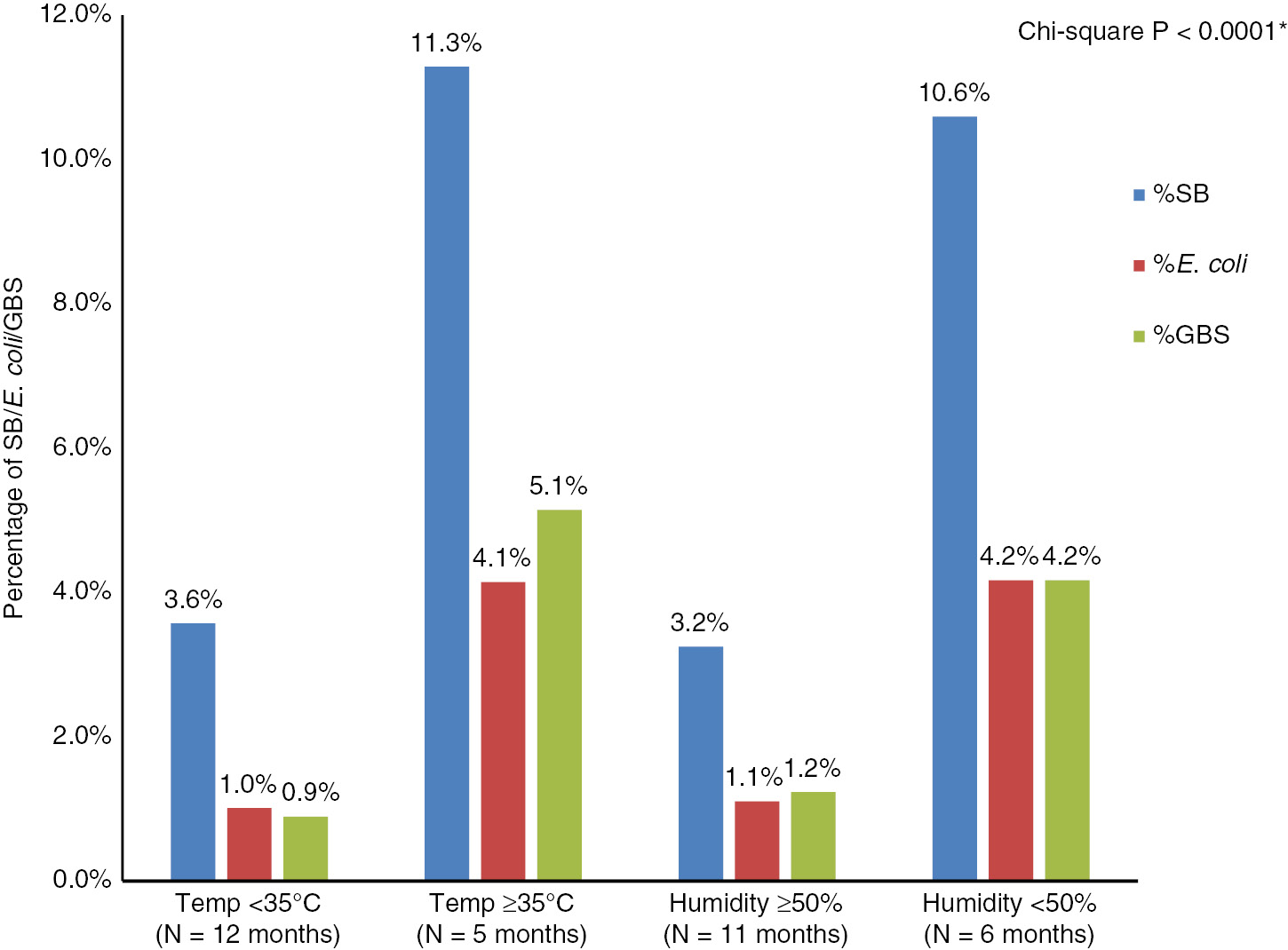

Significant correlations were detected between the percentage of SB per month, the average monthly temperature (r=+0.677, n=17, P=0.003) and humidity (r=−0.587, n=17, P=0.013) (Figure 2). The positive cultures were distributed over 12 months with temperatures <35°C and 5 months with temperatures ≥35°C, 11 months with humidity >50% and 6 months with humidity ≤50% as per the cutoffs determined by the ROC analysis. The percentage of SB was double in the months with temperatures ≥35°C (11.3% vs. 3.6%, respectively; P<0.0001) and humidity ≤50% (10.6% vs. 3.2%; P<0.0001). This when applied to SB with E. coli and GBS showed similar results (Figure 3).

Correlation between percentage of SB per month with mean monthly temperature °C and humidity %.

Significant P value <0.05. Percentage SB per month=number of SB per month/mean deliveries per month.

Distribution of SB, E. coli and GBS according to temperature and humidity.

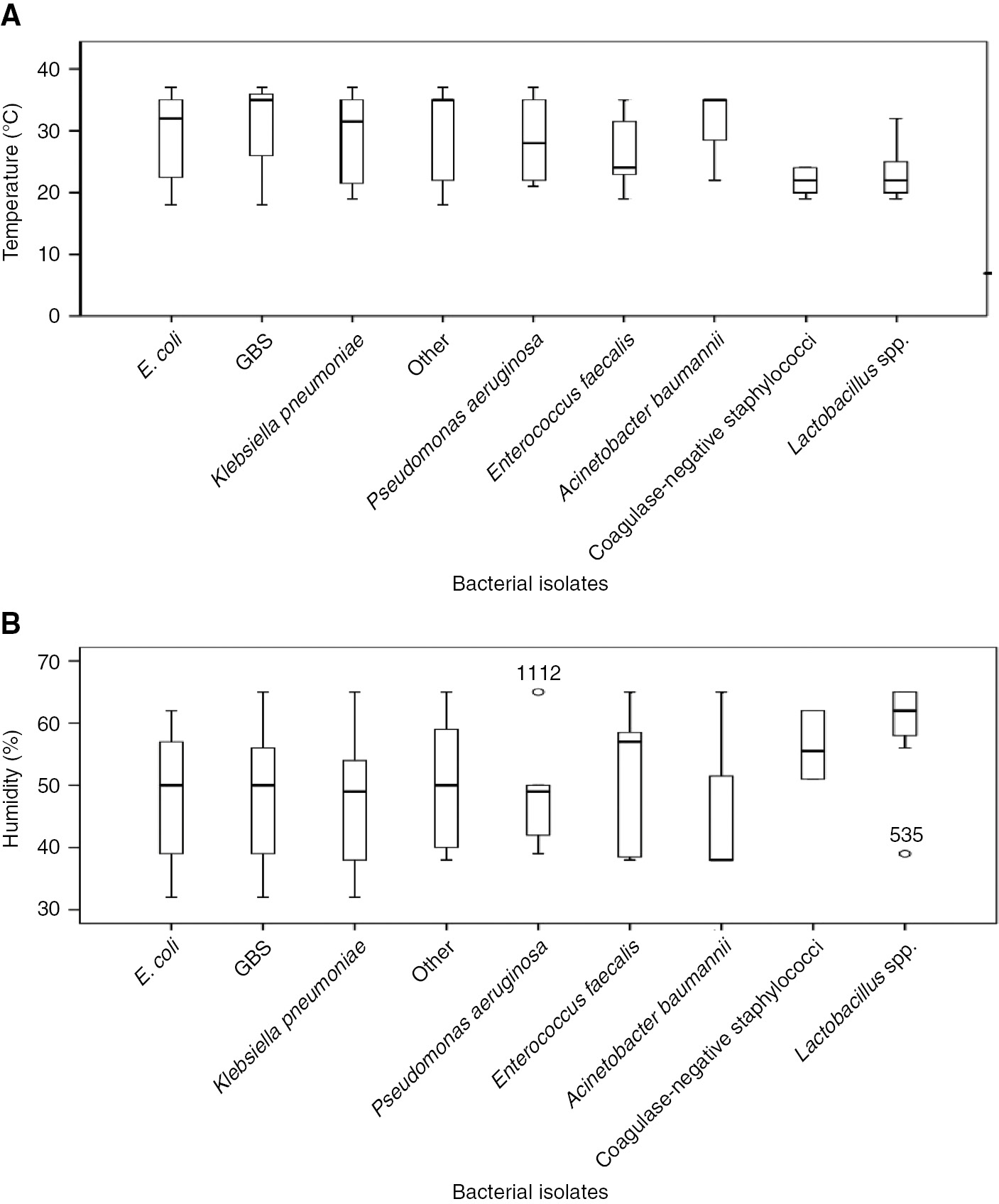

The box plot analysis indicates that in this group of pregnant women, infections caused by E. coli, GBS and Klebsiella were more likely to be diagnosed in the months of higher temperature and lower humidity. The inverse was noted for coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Lactobacillus (Figure 4).

Box plot representing the comparison between different bacterial isolates; (A) temperature, (B) humidity.

Discussion

The worldwide prevalence of asymptomatic SB in pregnancy is 2–8% [2]. However, the local prevalence ranges from 1.7 to 12.7% in neighboring Sharjah and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) [12], [13], [14], and 9.9% as previously reported from Qatar [9]. Here, we report a period prevalence of 11.25% similar to local figures but markedly higher than the worldwide prevalence. This suggests that environmental factors and variation in culture patterns are similar throughout the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and our findings can be generalized to the region.

Qatar is home to a predominantly expatriate population belonging to more than 50 nations, with only 15% nationals [15]. The association between ethnicity and urinary infections has been studied before in men and newborns showing Caucasians more at risk of infections compared to Asians or Hispanics [16], [17]. We have recorded the nationality of our patients and are hence able to report the variations as per the geographical region of origin, with a focus on Middle East and Asia. The largest variation was noted between Egyptians and Sudanese, despite being geographical neighbors. In Egypt and Sudan, the prevalence of bacteriuria is about 3–5 times higher than the Egyptian and Sudanese population in Qatar, which could be explained by socioeconomic and environmental factors [18], [19]. The variations reported need to be subjected to further analysis accounting for all possible confounding factors.

The studies reporting the effects of meteorological variables on UTI have equivocal results. A community-based study in Greece was able to demonstrate that the frequency of house calls due to urinary symptoms in the general population showed a positive correlation with temperature and a negative correlation with humidity similar to our study [4]. However the temperature or humidity cutoffs were not defined. A cross-sectional retrospective analysis in pregnant women of Iran showed more than 7 times increased frequency of urinary infection in the winter months [6]. A longitudinal analysis conducted in the UK showed autumnal seasonality for UTI consultation in primary care demonstrated over 7 years in people <70 years of age, after which the seasonality diminished [5]. The inconsistencies reported are more likely due to methodological flaws as most of these were retrospective analyses.

This study shows that the frequency of SB in pregnancy increases during hot and dry ambiance, which is the climate that exists during majority of the months in the Middle East. We demonstrated a clustering of the cases where the temperature rose above 35°C and the humidity fell below 50%. This can be attributed to the increased perspiration, perineal moisture, dehydration, decreased fluid intake and urine output noted during these months. The artificial control of surroundings using air conditioners is intensified during the summer months and this aggravates the problems of dehydration and decreased fluid intake. There are studies that have shown a significant increase in the sexual activity of humans during hotter months [20]. Most of our patients with SB belonged to the younger age group who are more physically and sexually active, thus exposing them to infection more during the hotter months.

Another important contributing factor is the virulence of infection-causing organisms. In this study, the temperatures that favor the growth of various organisms have been charted. This has been studied extensively worldwide [21]. The organisms most commonly identified in our study were E. coli, GBS and Klebsiella, and these bacteria favor higher temperatures and lower humidity. Hence, suggesting an increased virulence of these organisms during the hotter months could explain the increased incidence of SB [21].

In the primary-care setting of Qatar [9], the study of SB in pregnancy showed that E. coli and GBS were equally prevalent (31% and 30%, respectively). In our study, a similar pattern was demonstrated. However, with cultures below <105 cfu/mL, GBS was the most common organism. GBS is a commensal gastrointestinal microorganism, which may result in subsequent vaginal colonization and bacteriuria. The correlation between GBS bacteriuria and heavy vaginal colonization has been established previously. Hence, our results may indicate a higher prevalence of GBS colonization in pregnant women in Qatar, an observation that requires future study and re-evaluation of local screening practices, given the potential morbidity from GBS infection [22], [23].

There are some potential limitations in our study that include the intrinsic limitations of the methodologies of retrospective studies. The sample size was calculated over a 10-month period, due to the change of medical records into an electronic format that resulted in the availability of the medical records data only until March 2013. The denominator used for our analysis was an estimate derived from the average monthly delivery rate in the hospital over 5 years. This does invite further in-depth and possibly prospective analysis using absolute figures.

On the upside, this study was conducted in the foremost tertiary-care hospital caring for the needs of women in Qatar, handling 85% of the total nationwide deliveries. Our study sample is representative of the population in Qatar, and adequately powered to detect statistically significant differences between variables. The meteorological variables were sourced from international data reducing the chance of error. Our laboratory follows strict protocols that helps identify samples contaminated with vaginal flora. This, along with the method and means of sample collection in boric acid containers, consistent with worldwide practice, reduces the chances of false-positives and improves the validity of our results. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first epidemiological study to assess the effects of meteorological variables on the prevalence of bacteriuria in pregnancy. It is generalizable to the Middle East region, having a diverse and multicultural population and a similar seasonal pattern, and may guide local health care policies and practices such as increased alertness of medical staff toward detection of urinary infections, advice to avoid dehydration and encourage better hygiene practices especially during the warmer and drier months.

In conclusion, Qatar has an 11.25% prevalence of SB, widely distributed among various nationalities. There is significantly more bacteriuria detected during the warmer and drier months, with double the percentage of bacteriuria when the average temperature is ≥35°C and humidity ≤50%. GBS and E. coli were the most common organisms isolated, both of which showed a similar pattern of prevalence. Although further in-depth analysis and prospective studies are required, these findings could dictate changes in public health awareness strategies.

The publication of this article was funded by the Qatar National Library.

Author contributions: MM, MA and SA co-designed the study and applied for ethical exemption. MM, MA, FM, DA, SE, MZ and GF collected the data. MM, FM, DA, SE, MZ and GF assisted with the data analysis, data interpretation and preparation of the manuscript, which was reviewed by MA, SA and GF. All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Hooton T, Gupta K. Urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc. http://www.uptodate.com [cited 2019 May]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urinary-tract-infections-and-asymptomatic-bacteriuria-inpregnancy#H249334770.Search in Google Scholar

2. McCormick T, Ashe RG, Kearney PM. Urinary tract infection in pregnancy. TOG 2018;10:156–62.10.1576/toag.10.3.156.27418Search in Google Scholar

3. Fares A. Factors influencing the seasonal patterns of infectious diseases. Int J Prev Med 2013;4:128–32.Search in Google Scholar

4. Falagas ME, Peppas G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Karalis N, Theocharis G. Effect of meteorological variables on the incidence of lower urinary tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2009;28:709.10.1007/s10096-008-0679-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Rosello A, Pouwels KB, Domenech De Cellès M, Van Kleef E, Hayward AC, Hopkins S, et al. Seasonality of urinary tract infections in the United Kingdom in different age groups: longitudinal analysis of The Health Improvement Network (THIN). Epidemiol Infect 2018;146:37–45.10.1017/S095026881700259XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Amiri M, Lavasani Z, Norouzirad R, Najibpour R, Mohamadpour M, Nikpoor AR, et al. Prevalence of urinary tract infection among pregnant women and its complications in their newborns during the birth in the hospitals of Dezful City, Iran, 2012–2013. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2015;17:e26946.10.5812/ircmj.26946Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Al-Hasan MN, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Seasonal variation in Escherichia coli bloodstream infection: a population-based study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:947–50.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02877.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Deeny SR, van Kleef E, Bou-Antoun S, Hope RJ, Robotham JV. Seasonal changes in the incidence of Escherichia coli bloodstream infection: variation with region and place of onset. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:924–9.10.1016/j.cmi.2015.06.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Aseel M, Al-Meer F, Al-Kuwari M, Ismail M. Prevalence and predictors of asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant women attending primary health care in Qatar. Middle East J Fam Med 2009;7:10–3.Search in Google Scholar

10. Urine specimens – an overview of collection methods, collection devices, specimen handling and transportation. [Internet] Specimencare.com. 2018. http://www.specimencare.com/main.aspx?cat=711&id=6235#ref3.Search in Google Scholar

11. Past weather in Doha, Qatar – Yesterday or Further Back [Internet]. https://www.timeanddate.com/weather/qatar/doha/historic.Search in Google Scholar

12. Abdullah AA, Al-Moslih MI. Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J 2005;11:1045–52.Search in Google Scholar

13. Al Sibiani SA. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in Jeddah, western Region of Saudi Arabia: call for assessment. JKAU Med Sci 2010;17:29–42.10.4197/med.17-1.4Search in Google Scholar

14. Lele U, Al Essa A, Shahane V. The prevalence of urinary tract infection among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at a tertiary care centre in Al Rass, Al Qassim. Int J Sci Res 2016;5:23–7.10.21275/v5i5.NOV163182Search in Google Scholar

15. The general Secretariat of the planning council. Population and Social Statistics, Qatar 2013 [cited 2017 Mar 6]. Available from: http://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/StatisticalReleases/Population/Population/2013/Pop_Population_Chapter_AnAb_AE_2013.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

16. Van Den Eeden SK, Shan J, Jacobsen SJ, Aaronsen D, HaqueR, Quinn VP, et al. Evaluating race/ethnic disparities in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men. J Urol 2012;187:185–9.10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Chen L, Baker MD. Racial and ethnic differences in the rates of urinary tract infections in febrile infants in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2006;22:485–7.10.1097/01.pec.0000226872.31501.d0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Hamdan HZ, Ziad AHM, Ali SK, Adam I. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections and antibiotics sensitivity among pregnant women at Khartoum North Hospital. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2011;10:2.10.1186/1476-0711-10-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Shaheen HM, Farahat TM, Hammad NA. Prevalence of urinary tract infection among pregnant women and possible risk factors. Menoufia Med J 2016;29:1055–9.Search in Google Scholar

20. Demir A, Uslu M, Arslan OE. The effect of seasonal variation on sexual behaviors in males and its correlation with hormone levels: a prospective clinical trial. Cent European J Urol 2016;69:285–9.Search in Google Scholar

21. Shapiro RS, Cowen LE. Thermal control of microbial development and virulence: molecular mechanisms of microbial temperature sensing. MBio 2012;3. pii: e00238-12.10.1128/mBio.00238-12Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Muller AE, Oostvogel PM, Steegers EAP, Dorr PJ. Morbidity related to maternal group B streptococcal infections. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2006;85:1027–37.10.1080/00016340600780508Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Keong C, Carey AJ, Ipe D, Ulett GC. Current understanding of streptococcal urinary tract infection. In: Nikibakhsh A, editor. Clinical management of complicated urinary tract infection. InTechOpen, 2011. DOI: 10.5772/22012.Search in Google Scholar

©2020 Fathima Minisha et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- 10.1515/jpm-2020-frontmatter1

- Review

- Delivery room handling of the newborn

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Examining the validity of a predictive model for vaginal birth after cesarean

- Correlation between endometrial thickness and perinatal outcome for pregnancies achieved through assisted reproduction technology

- Significance of the routine first-trimester antenatal screening program for aneuploidy in the assessment of the risk of placenta accreta spectrum disorders

- A decade’s experience in primipara, term, singleton, vertex parturients with a sustained low rate of CD

- Survey of alongside midwifery-led care in North Rhine-Westfalia, Germany

- Correlation between aneuploidy pregnancy and the concentration of various hormones and vascular endothelial factor in follicular fluid as well as the number of acquired oocytes

- Bacteriuria in pregnancy varies with the ambiance: a retrospective observational study at a tertiary hospital in Doha, Qatar

- Microarray findings in pregnancies with oligohydramnios – a retrospective cohort study and literature review

- Lifestyle characteristics of parental electronic cigarette and marijuana users: healthy or not?

- Influence of maternal HIV infection on fetal thymus size

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Clinical outcome of prenatally suspected cardiac rhabdomyomas of the fetus

- Original Articles – Newborns

- Prolonged ventilation and postnatal growth of preterm infants

- Letter to the Editor

- Neonatal sepsis associated with Lactobacillus supplementation

Articles in the same Issue

- 10.1515/jpm-2020-frontmatter1

- Review

- Delivery room handling of the newborn

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Examining the validity of a predictive model for vaginal birth after cesarean

- Correlation between endometrial thickness and perinatal outcome for pregnancies achieved through assisted reproduction technology

- Significance of the routine first-trimester antenatal screening program for aneuploidy in the assessment of the risk of placenta accreta spectrum disorders

- A decade’s experience in primipara, term, singleton, vertex parturients with a sustained low rate of CD

- Survey of alongside midwifery-led care in North Rhine-Westfalia, Germany

- Correlation between aneuploidy pregnancy and the concentration of various hormones and vascular endothelial factor in follicular fluid as well as the number of acquired oocytes

- Bacteriuria in pregnancy varies with the ambiance: a retrospective observational study at a tertiary hospital in Doha, Qatar

- Microarray findings in pregnancies with oligohydramnios – a retrospective cohort study and literature review

- Lifestyle characteristics of parental electronic cigarette and marijuana users: healthy or not?

- Influence of maternal HIV infection on fetal thymus size

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Clinical outcome of prenatally suspected cardiac rhabdomyomas of the fetus

- Original Articles – Newborns

- Prolonged ventilation and postnatal growth of preterm infants

- Letter to the Editor

- Neonatal sepsis associated with Lactobacillus supplementation