Abstract

Context

Gun violence negatively impacts not only victims but also their families and surrounding communities. Resources and counseling services may be available to support families affected by gun violence, but the families and their clinicians may not know about these resources or how to access them.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of a clinician-directed educational program on patient reports of their discussions with their physician regarding gun violence, prevention, and available resources for support and treatment.

Methods

This quasi-experimental, cross-sectional, survey-based, quality-improvement study included pre-, mid-, and posttraining surveys administered to patients and clinicians participating in an educational program at two urban healthcare centers in Philadelphia. The educational program included office enhancements (handouts and posters) and lunchtime presentations for clinicians regarding gun violence prevalence, prevention strategies, local support resources, and impacts on mental health for patients and their families. The anonymous patient survey was offered to all patients seen at two urban healthcare centers in Philadelphia during three nonconsecutive weeks over 3 months.

Results

Among 542 patients seen over the 3 weeks of survey collection, 428 completed the survey (response rate of 79 %). Sixty-four percent acknowledged being impacted by gun violence including the death of a loved one, witnessing a shooting, or being shot themselves. Over the course of the educational program, patients reported significant increases in (1) awareness of materials related to gun violence in the waiting areas, by 17.2 %, (2) discussions of gun violence with their clinician, by 12.1 %, and (3) discussions of methods to prevent gun injury, by 9.7 %. At the end of the study, 19.3 % of patients reported having discussions with their clinician about gun violence, and 14.3 % discussed strategies to prevent gun injury. Participating clinicians reported high levels of satisfaction and increased confidence when talking to patients about gun violence at the end of the program.

Conclusions

Providing clinician-directed education and printed materials increased the frequency with which clinicians discussed gun violence, prevention, and available resources with their patients. Increases were modest, with opportunities for improvement. A holistic and multifaceted approach is required to support families affected by gun violence, including education for clinicians and dissemination of information for families.

In 2023, approximately 43,000 people died in the United States due to gun injury [1]. The United States has the highest rates of gun violence among developed countries, including firearm accidental injury, homicides, deaths by suicide, and mass shootings [2]. Although firearm homicide rates remain highest among young Non-White males in urban areas [2], 3], the highest firearm suicide rates are found among older White males in rural communities [2]. Black and LatinX communities are disproportionately exposed to gun violence [4]. All states and communities are affected: rural, suburban, and urban [5].

Exposure to interpersonal gun violence is associated with increased reports of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depressive symptoms, substance use, disruptive behaviors, and the likelihood of gun carrying [6]. Community gun violence exposure is associated with poorer individual and neighborhood health [7]. Children, adolescents, and mothers exposed to gun violence, such as witnessing a shooting or hearing gunshots, are particularly vulnerable to negative behavioral and mental health outcomes [8], 9]. The burden of shootings therefore falls not only on the victims themselves but also on their families, friends, and communities, leading to feelings of grief, fear, hopelessness, and PTSD [2], 7].

The US Surgeon General declared gun violence a national public health crisis with calls to increase prevention, surveillance, support, and treatment for individuals, families, and communities affected by gun violence [10]. Many organizations, such as the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), have issued policy statements and guidelines to address gun violence [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Tragically, many communities have found themselves addressing the impacts of gun violence for years [4], [16], [17], [18]. Highly impacted communities have developed resources, initiatives, organizations, and support systems for those affected by gun violence, such as the Anti-Violence Partnership of Philadelphia [19]; however, patients, families, and healthcare professionals may be unaware of such helpful programs and resources [20].

Healthcare professionals are well-positioned to assist in patient care, education, advocacy, and research to reduce gun violence and impacts on communities [13], 21]. Counseling, in particular, invites dialog to help identify patients with mental health issues related to gun violence and prevent gun-related injuries [18], 22], 23]. Patients and families generally agree that their physicians should discuss gun safety, storage, and prevention [15], [16], [17], [18, 22], 24], 25]. Clinicians may benefit from utilizing specific communication strategies while discussing gun violence with patients and families, such as establishing trust, maintaining a nonjudgmental approach, tailoring discussion to the patient’s age, and reducing feelings of stigma as patients seek mental health support services [21], [26], [27], [28]. Avoiding controversial direct questions about gun ownership and providing universal recommendations may also help facilitate discussions in a nonjudgmental fashion [21], 26], 29]. Integrating these communication skills requires awareness, training, attention, and practice. Although clinicians are well-positioned to counsel patients, many do not [20], [21], [22], citing barriers such as limited knowledge, time, support, and payment [21]. Educational programs have the potential to motivate clinicians to ask patients about gun violence, promote gun injury prevention, evaluate mental health, and direct patients to appropriate resources and support services [8], 17], 21].

Philadelphia had 1,291 nonfatal and 375 fatal shooting victims in 2023, with a disproportionately high number of shootings in areas such as North and West Philadelphia, where Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (PCOM) urban healthcare centers are located [30]. In this quality-improvement study, we investigated an educational program designed to help clinicians talk to their patients about gun violence, prevention, and available resources to support and treat those impacted by gun violence.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study was deemed exempt by the PCOM Institutional Review Board (Protocol #H24-038X). Funding was provided by PCOM’s Division of Research and the Community-Engaged Faculty Research Fellowship. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all individuals by agreeing to participate in the study survey. A gift card ($10) was issued to patients as a thank you for completing the survey.

Study design

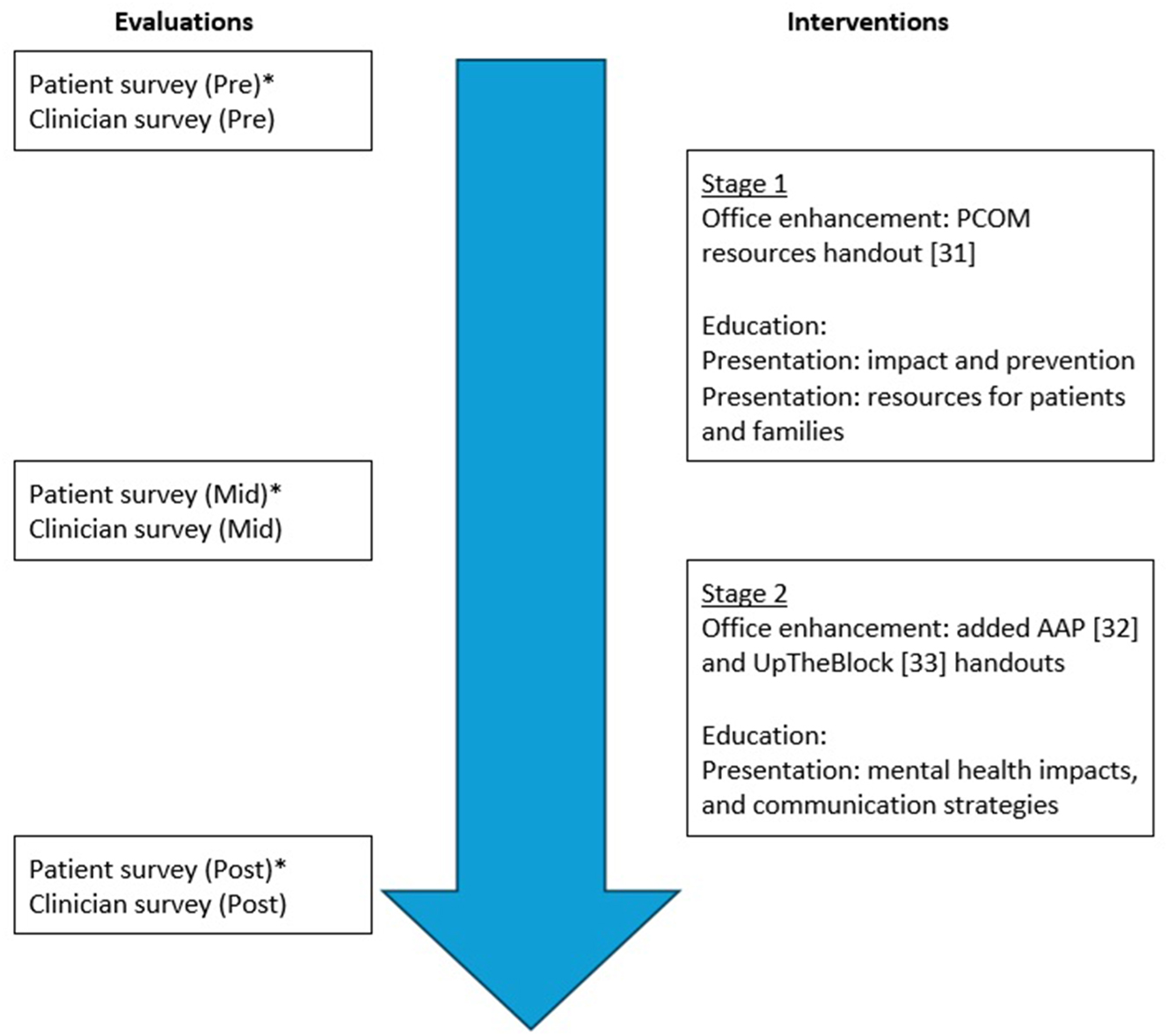

The study design (Figure 1) included a quasi-experimental, cross-sectional, survey-based, quality-improvement evaluation of a clinician-directed educational program, which included pre-, mid-, and posttraining surveys administered to patients and clinicians participating in an educational program.

Study methodology. This figure depicts the project timeline with patient surveys (three cycles), clinician surveys (three cycles) and educational interventions (two cycles including clinician-directed presentations and office enhancements). Patient surveys were administered to all patients after they finished their appointments over three separate one-week periods of time (February 5-9, March 4-8, and April 8-12, 2024).

Sample

Patients were recruited from PCOM Lancaster (West Philadelphia) and PCOM Cambria (North Philadelphia) Family Practice Urban Healthcare Centers (Supplementary Material). Both centers predominately serve patients who identify as Black/African American. Medicaid and Medicare represent the most common insurance plans. All patients seen during the 3 weeks of patient survey collection (February 5-9, March 4-8, and April 8-12, 2024) were invited to complete the anonymous surveys. Six clinician participants (three physicians and one physician assistant from Lancaster Avenue, and two physicians from Cambria) were included in the study.

Educational program description

The educational program included three lunchtime presentations: (1) the impact of gun violence on patients and populations, and preventive strategies; (2) UpTheBlock: a collection of local resources to assist families affected by gun violence; and (3) the impact of gun violence on mental health and strategies for communicating with families. These one-hour interactive sessions were presented remotely and projected live to each of the healthcare center sites. Topics related to gun violence included prevalence, prevention strategies, local support resources, and impacts on mental health for patients and their families.

The educational program also included office enhancements, placing posters in waiting areas, and displaying detailed patient handouts, including local support resources [31], AAP gun safety [32], and UpTheBlock [33].

Patient survey instrument

Development

The patient survey (Supplementary Material) was developed by the three investigators with input from two clinical psychologists, one clinical PsyD second-year student, two family physicians, one psychiatrist, and two nonclinical professionals who had been directly impacted by gun violence. The final survey (Supplementary Material) was tested with two clinical psychologists and two nonclinicians who recommended the survey be verbally administered to foster communication and ascertain the need for additional support if needed.

Administration and data collection

For the weeks of the study when patient surveys were administered (February 5-9, March 4-8, and April 8-12, 2024), all patients seen were offered the opportunity to complete the survey. Surveys were verbally administered to consenting patients by one surveyor (a physician or trained student volunteer from the PCOM). A gift card ($10) was issued as a thank you to those completing the survey. Survey responses were entered into Google Forms and organized in Microsoft Excel for analysis.

Clinician survey instruments

Development

The clinician survey (Supplementary Material) was developed by the three investigators with input from one pediatrician and two family physicians. Surveys addressed their knowledge of local resources to support families affected by gun violence, comfort in addressing gun violence with patients and families, and reflections of the patient survey data, and to identity strategies to improve communication regarding gun violence (Supplementary Material).

Administration and data collection

Anonymous clinician surveys were administered by Survey Monkey after each patient data collection period, repeated three times after the first, second, and third patient surveys. An anonymous postprogram evaluation (Supplementary Material) was also included with the final clinician survey.

Analysis

Data from unidentified patient surveys were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed with SPSS by the investigators. Survey data from anonymous clinician surveys were collected through SurveyMonkey without identifiers. Paired t tests or nonparametric equivalents were employed to compare pre- and postintervention responses for patients and clinicians. Clinician responses to open-ended survey questions were analyzed utilizing thematic analysis to identify key themes.

Results

Patient survey responses

Of the 542 patients seen over the 3 weeks of survey collection, 428 completed the survey (response rate of 79 %): 153 patients (February 5-9, 2024), 135 (March 4-8, 2024), and 140 (April 8-12, 2024). Approximately 67 % of patients were seen at the Lancaster location, and the remaining 33 % were seen at the Cambria location.

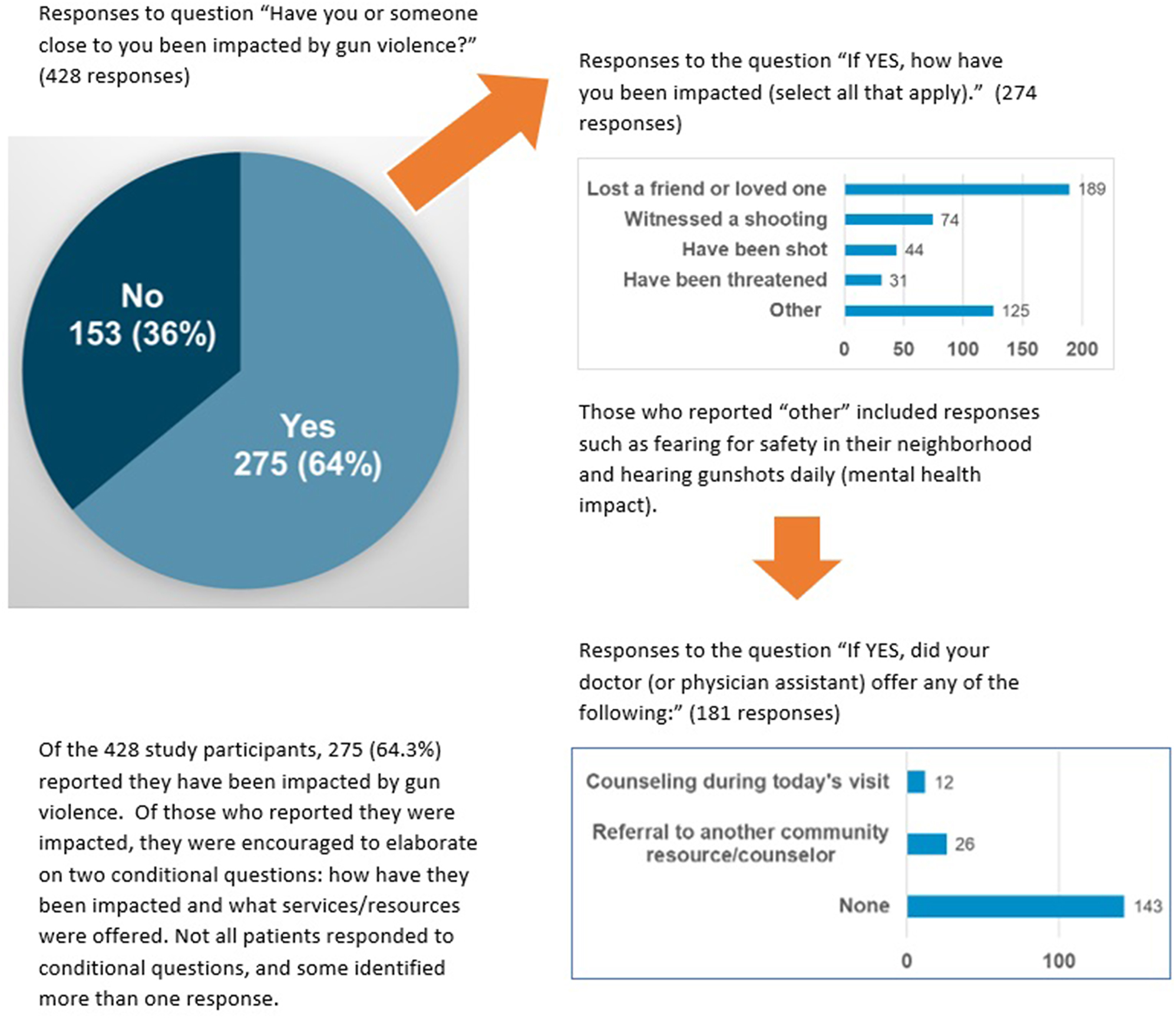

Of the 428 patients surveyed, 275 (64.3 %) acknowledged being impacted by gun violence (Figure 2), and 268 (63.0 %) indicated a desire for more information or resources concerning the impact of gun violence. When asked if their doctor or physician assistant seemed knowledgeable about gun safety or ways to support the family, 210 (49.1 %) strongly agreed or agreed, and 193 (45.1 %) responded that they did not know. Averaged across all three survey cycles, 76 (18.0 %) reported noticing materials related to gun violence in the waiting areas, 51 (12.0 %) indicated that the clinician discussed guns or gun violence, and 29 (6.8 %) said that they discussed ways to prevent gun injury during the visit. Positive trends were seen as the study progressed (Table 1).

Patient impact by gun violence. Among the 428 study participants, 275 (64.3 %) reported that they have been impacted by gun violence. Among those who reported that they were impacted, they were encouraged to elaborate on two conditional questions: How have they been impacted and what services/resources were offered. Not all patients responded to conditional questions, and some identified more than one response.

Patient survey responses.

| Survey question | Survey date | Yes | No | I Cannot remember/not sure/maybe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did you take or see any materials related to gun violence in our waiting room today? | Week 1 (Feb) | 13 (8.5 %) | 129 (84.3 %) | 11 (7.2 %) |

| Week 2 (Mar) | 27 (20.0 %) | 96 (71.1 %) | 12 (8.9 %) | |

| Week 3 (Apr) | 36 (25.7 %) | 97 (69.3 %) | 7 (5.0 %) | |

| Total | 76 (17.8 %) | 322 (75.2 %) | 30 (7.0 %) | |

| Did your doctor (or physician assistant) talk to you about guns or gun violence today? | Week 1 (Feb) | 11 (7.2 %) | 141(92.2 %) | 1 (0.6 %) |

| Week 2 (Mar) | 13 (9.6 %) | 121 (89.6 %) | 1 (0.7 %) | |

| Week 3 (Apr) | 27 (19.3 %) | 113 (80.7 %) | 0 (0 %) | |

| Total | 51 (11.9 %) | 375 (87.6 %) | 2 (0.5 %) | |

| Did your doctor (or physician assistant) talk to you today about ways to prevent gun injury? | Week 1 (Feb) | 7 (4.6 %) | 146 (95.4 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Week 2 (Mar) | 2 (1.5 %) | 131 (97 %) | 2 (1.5 %) | |

| Week 3 (Apr) | 20 (14.3 %) | 119 (85 %) | 1 (0.7 %) | |

| Total | 29 (6.8 %) | 396 (92.5 %) | 3 (0.7 %) | |

| Would you like more information or resources available to those impacted by gun violence? | Week 1 (Feb) | 85 (55.6 %) | 53 (34.6 %) | 15 (9.8 %) |

| Week 2 (Mar) | 80 (59.3 %) | 53 (39.3 %) | 2 (1.5 %) | |

| Week 3 (Apr) | 104 (74.3 %) | 34 (24.3 %) | 2 (1.4 %) | |

| Total | 269 (62.9 %) | 140 (32.7 %) | 19 (4.4 %) |

| Survey question | Survey date | Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | I don’t know |

|

|

||||||

| My doctor (or physician assistant) seemed knowledgeable about gun safety and ways to support my family. | Week 1 (Feb) | 28 (18.3 %) | 28 (18.3 %) | 13 (8.5 %) | 0 (0 %) | 84 (54.9 %) |

| Week 2 (Mar) | 47 (34.8 %) | 34 (25.2 %) | 3 (2.2 %) | 6 (4.4 %) | 45 (33.3 %) | |

| Week 3 (Apr) | 36 (25.7 %) | 37 (26.4 %) | 3 (2.1 %) | 0 (0 %) | 64 (40.7 %) | |

| Total | 111 (25.9 %) | 99 (23.1 %) | 19 (4.4 %) | 6 (1.4 %) | 193 (45.1 %) | |

-

Patient surveys were administered to all patients after they finished their appointments over three separate one-week periods over the course of the clinician-directed educational program (February 5-9, March 4-8, and April 8-12, 2024). Among the 542 patients seen during the three weeks of survey collection, 428 completed the survey, a response rate of 79 %. Of the 428 patients who responded, 153 responded in week 1 (February), 135 in week 2 (March), and 140 in week 3 (April).

A chi-square analysis was performed to investigate whether the gun violence educational program impacted patient awareness of gun violence resources displayed in waiting areas. A significant increase was detected in the number of patients noticing materials related to gun violence in the waiting room (χ2[4]=16.90, p=0.002). Specifically, from time one to time three, there was a 17.2 % increase in patients being aware of gun violence–related materials in the waiting room. Regarding patient accounts of discussing guns or gun violence with their clinician, there was a significant increase in prevalence from 7.2 % at time one to 19.3 % at time three (χ2[4]=12.01, p=0.017). There was a 9.7 % increase in the number of patients who indicated that the care provider discussed ways to prevent gun injury from time one to time three (χ2[4] = 21.87, p<0.001).

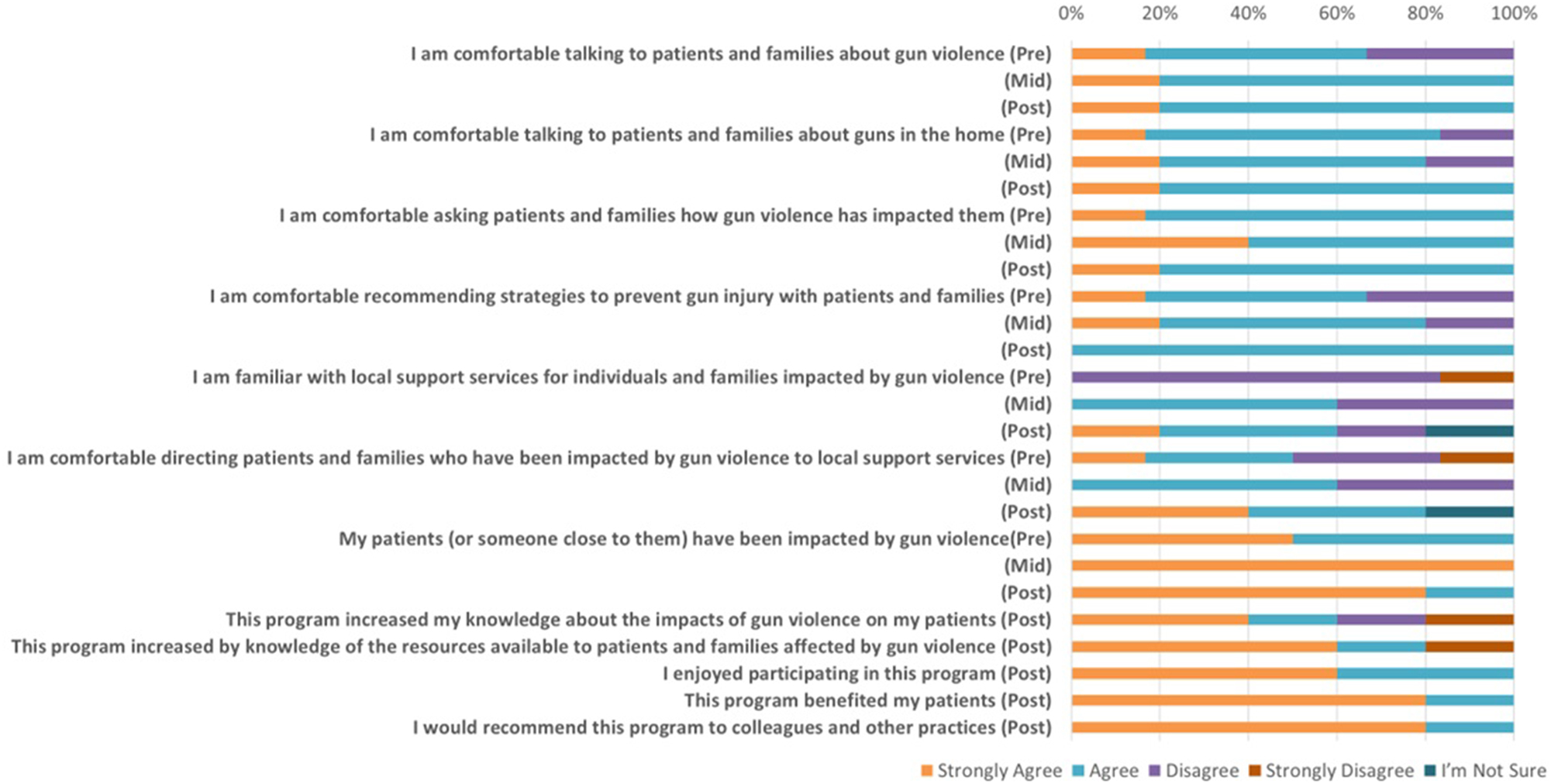

Clinician survey responses

Anonymous survey responses were collected from the six participating clinicians at three points of the study: pre-, mid-, and posttraining. One clinician was unable to participate for the entire program and responded to only the first survey. Because of the small sample size, a formal statistical analysis was not feasible. However, clinician responses to questions addressing their comfort levels with talking to patients about gun violence appear to have increased throughout the program (Figure 3).

Clinician survey responses. Participating clinicians responded to these first seven questions at three points of the study: Pre-, mid- and posttraining. Participating clinicians also responded to the last five likert-type questions at the end of the educational program. Six clinicians (five physicians and one physician assistant) began the program, with one physician leaving after the first month of the study.

In addition to responding to the seven standard questions across surveys (Figure 3), clinicians were invited to review a summary of patient data from the first two patient surveys and respond to three open-ended quality-improvement questions for the midpoint survey. Responses to the question “What additional strategies would you consider to improve our ability to communicate with Lancaster and Cambria patients regarding gun violence, prevention strategies, and available resources?” included being more intentional about asking patients about gun violence, handing out materials, engaging staff and medical students to help ask screening questions, and embedding screening questions in the electronic medical record. Responses to the question “Realistically, which strategies would you consider immediately (in the next 2 weeks) before this pilot study concludes?” included being more intentional about asking patients about gun violence, and providing pamphlets for families seeking mental health support services regarding gun violence. Responses to the question “What additional resources do you need to improve our ability to talk to patients and families about gun violence?” included being more intentional about talking to patients about gun violence, attending more training sessions, hosting group therapy sessions with patients and counselors, providing more handouts and resources for families, and hiring a social worker.

In addition to responding to the seven standard questions across surveys (pre-, mid-, and posttraining), clinicians were invited to answer five Likert-type questions regarding their experience with the educational program (Figure 3) and to respond to two open-ended questions for the final survey. Responses were generally positive. Reported strengths of the program included the importance of the topic, raising awareness, presentations, and patient engagement. As an example, one clinician reported “the patients being able to talk about their experiences” as a strength of the program. Reported areas for improvement included handouts for each patient, solution-based interventions, and face-to-face focus groups with clinicians, staff, patients, and families. As one clinician reported, “I would be interested in participating in a face-to-face focus group with physicians, staff, and patients. That would be helpful in determining the role of the physician, as it applies to gun violence. With such a ‘big' issue, what is the role of the physician in helping families address gun violence? Open community-based discussions may shed light on this.”

Discussion

Nearly 64 % of patients in this study reported being affected by gun violence, including the death of a loved one or friend, followed by witnessing a shooting, or being shot themselves. Disproportionately high rates of gun-related homicides occur in the areas surrounding the urban healthcare centers in West and North Philadelphia [30]. Study findings are consistent with reports from other urban, low-income, and black communities [2], 4], 8], 22]. For instance, in a study of patients from four urban cities (Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C.), 24 % reported exposure to a gun violence fatality, and nearly 25 % reported knowing someone who died from gun violence [4]. In a study of hospitalized children in the Bronx, New York, 60 % reported hearing gunshots and 41.8 % reported that a friend or relative had been shot [22]. Although not explicitly asked in our survey, only one patient volunteered having a relative who died due to gun-related suicide. Suicide accounts for more than one-half of deaths by firearm in the United States [34]. Therefore, gun-related suicide appears underrepresented in our study.

Throughout the three stages of the study, patients reported significant increases in conversations with their clinicians with regard to gun violence exposure and strategies to prevent gun injury. Clinicians participated in the educational program, which included three lunchtime educational presentations addressing prevalence, impacts on mental health, prevention, local support resources, and communication strategies when talking to patients about gun violence. Clinicians reported high levels of satisfaction and increasing confidence when talking to patients about gun violence at the end of the program. At the end of the study, however, only 19.3 % (increased from 7.2 %) of patients reported discussions about gun violence and 14.3 % (increased from 4.6 %) about strategies to prevent gun injury. Despite significant increases in discussions about gun violence and prevention, opportunities for improvement remain. The data suggest that although the educational program likely played a role in increasing clinician–patient communication, additional measures are needed to address the gun violence epidemic and its effects on the mental health of patients.

Surveyors reported that patients often seemed surprised that physicians and healthcare students were asking about gun violence and how gun violence impacts their daily lives. Gun violence directly and indirectly impacts the mental health of patients, families, and communities [2], [6], [7], [8], [9], and clinicians are well-positioned to ask patients about gun violence, promote gun injury prevention, evaluate mental health, and direct families to appropriate support and counseling services [8], [20], [21], [22, 35]. Patients may express a willingness to share information and discuss exposure to gun violence with their physicians [36], but others believe that clinicians should have a more limited role in discussing topics related to guns and gun ownership [25]. Among survivors of firearm injury in Indianapolis, most preferred to receive emotional support from family members rather than healthcare providers or mental health practitioners [27]. Participants also advocated for the use of credible messengers [27]: those who have shared lived experiences, endured a significant life change, considered part of the community, and are skilled in relationship building and communication [37], 38]. Establishing trust in a nonjudgmental and supportive manner is critical for fostering therapeutic relationships. Supporting patients, families, and communities affected by gun violence likely requires a holistic approach with support from both clinicians and nonclinician credible messengers.

We elected to administer the surveys verbally, largely to ensure that all patients could participate in the study regardless of visual acuity or reading level. There were a few unanticipated positive outcomes. First, patients shared freely and elaborated on their experiences with gun violence. The survey served as a method to encourage discourse, rather than simply soliciting responses to Likert-scale–type questions. Second, verbal survey administration allowed surveyors to build rapport and begin to foster a trusted relationship with the patients.

Patients noticed office enhancements (fliers and posters) placed in the waiting areas and examination rooms as the study progressed. By the end of the program, 25 % reported seeing materials related to gun violence in the waiting areas. Additionally, nearly 66 % of patients requested additional information about resources for those impacted by gun violence. Providing educational materials in waiting areas and showing short videoclips regarding various public health initiatives has been shown to be an effective strategy for reaching patients [39], [40], [41]. Therefore, providing durable materials, such as fliers and posters, may help to educate patients and families about gun violence, prevention, and resources to support those affected by gun violence.

Prevention remains the cornerstone of addressing community and public health crises [42]. Preventing gun violence would eliminate the need to treat sequalae, including tragic mental and emotional impacts. To effectively address gun violence as a public health crisis, a comprehensive strategy must consider not only medical interventions but also the complex interplay of social, cultural, economic, psychological, and environmental factors that contribute to well-being [43], [44], [45]. Osteopathic medicine, with its focus on treating the whole person and addressing root causes [46], is uniquely positioned to contribute to this effort. By integrating behavioral health, engaging with communities, and advocating for policies that address social determinants of health, osteopathic physicians can play a crucial role in preventing gun violence and promoting community well-being.

Although this study showed improvement in clinician–patient communication, there are some limitations to the current study design. First, the study was limited to two urban healthcare centers with only six clinicians; expanding the study to include additional locations and populations may improve generalizability. Second, in efforts to keep the survey brief, demographic information was not collected. Information about age, address, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status would provide additional insight. Third, patients were not asked explicitly about gun violence as it pertains to suicide, likely leading to underreporting. Because suicide is the leading cause of firearm-related mortality in the United States [34], adding an explicit question about suicide will be informative for future studies. Fourth, the survey was issued to all patients whether the appointment was for a general well-check or a focused complaint unrelated to gun violence (e.g., sore throat, back pain). Patients are likely to benefit the most when discussions occur during routine well-checks, preventative visits, and relevant focused appointments [21]. Directing communication efforts during the most appropriate visits will be important to consider for future programs. Fifth, although supervised by a standard group of six clinicians, medical students generally initiate patient visits. Medical students rotated every 4 weeks and were not present for the entire 3-month educational program. Overall, the study did not incorporate the important role that medical students play in communication with patients related to gun violence. Sixth, the patient survey was administered verbally, and therefore, body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice may have influenced patient responses. Incorporating other survey methods [47], validating questions, or administering surveys by credible messengers [27] may address survey bias in future studies. Addressing these limitations in future studies will provide additional insights for supporting patients and families affected by gun violence.

Conclusions

A large number of patients in two urban healthcare centers reported being impacted by gun violence, including the death of a loved one, witnessing a shooting, or being shot themselves. This well-received clinician-directed educational program helped improve the frequency with which clinicians discussed guns, gun violence, prevention, and available resources to assist affected families within an urban community. Approaching gun violence as a public health crisis requires a holistic and multifaceted intervention aimed at educating healthcare professionals, engaging health systems, and disseminating information about resources available to families who have been impacted by gun violence.

-

Research ethics: This study was deemed exempt by the PCOM Institutional Review Board (Protocol #H24-038X).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals by agreeing to participate in the study survey.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have contributed equally.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (PCOM) Division of Research and the PCOM Community-Engaged Faculty Research Fellowship. The funding entities did not partake in any research activities such as conceptualization, survey development, data gathering or analysis.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation (NIHCM). Gun violence: the impact on society. 2024 https://nihcm.org/publications/gun-violence-the-impact-on-society [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

2. Hemenway, D, Nelson, E. The scope of the problem: gun violence in the USA. Curr Trauma Rep 2020;6:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-020-00182-x.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Durkin, A, Schenck, C, Narayan, Y, Nyhan, K, Khoshnood, K, Vermund, SH. Prevention of firearm injury through policy and law: the social ecological model. J Law Med Ethics 2020;48:191–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110520979422.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Smith, ME, Sharpe, TL, Richardson, J, Pahwa, R, Smith, D, DeVylder, J. The impact of exposure to gun violence fatality on mental health outcomes in four urban U.S. settings. Soc Sci Med 2020;246:112587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112587.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Firearm mortality by state. 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/firearm_mortality/firearm.htm [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

6. Abba-Aji, M, Koya, SF, Abdalla, SM, Ettman, CK, Cohen, GH, Galea, S. The mental health consequences of interpersonal gun violence: a systematic review. SSM-Mental Health 2024:100302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2024.100302.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Semenza, DC, Stansfield, R, Silver, IA, Savage, B. Reciprocal neighborhood dynamics in gun violence exposure, community health, and concentrated disadvantage in one hundred US cities. J Urban Health 2023;100:1128–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00796-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Leibbrand, C, Rivara, F, Rowhani-Rahbar, A. Gun violence exposure and experiences of depression among mothers. Prev Sci 2021;22:523–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01202-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Holloway, K, Cahill, G, Tieu, T, Njoroge, W. Reviewing the literature on the impact of gun violence on early childhood development. Curr Psychiatr Rep 2023;25:273–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01428-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. Firearm violence: a public health crisis in America; 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/firearm-violence-advisory.pdf [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

11. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Gun violence, prevention of (position paper). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/gun-violence.html [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

12. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Prevention of gun violence (policy statement). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/gun-violence.html [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

13. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on injury, violence, and poison prevention. Role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics 2009;124:393–402. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0943.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Gun safety and injury prevention. 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/gun-safety-and-injury-prevention/ [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

15. Lee, LK, Fleegler, EW, Goyal, MK, Doh, KF, Laraque-Arena, D, Hoffman, BD, et al.. AAP council on injury, violence, and poison prevention. Firearm-related injuries and deaths in children and youth: injury prevention and harm reduction. J Pediatr 2022;150. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060071.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Haser, G, Yousuf, S, Turnock, B, Sheehan, K. Promoting safe firearm storage in an urban neighborhood: the views of parents concerning the role of health care providers. J Community Health 2020;45:338–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00748-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Boge, LA, Dos Santos, C, Burkholder, JD, Koschel, BR, Cubeddu, LX, Farcy, DA. Patients’ perceptions of the role of physicians in questioning and educating in firearms safety: post-FOPA repeal era. South Med J 2019;112:34–8. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000915.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Price, JH, Clause, M, Everett, SA. Patients’ attitudes about the role of physicians in counseling about firearms. Patient Educ Couns 1995;25:163–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-3991(95)00780-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Anti Violence Partnership of Philadelphia (AVPP). Counseling services. https://avpphila.org/counseling/ [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

20. Hoops, K, Fahimi, J, Khoeur, L, Studenmund, C, Barber, C, Barnhorst, A, et al.. Consensus-driven priorities for firearm injury education among medical professionals. Acad Med 2022;97:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004226.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Carter, PM, Cunningham, RM. Clinical approaches to the prevention of firearm-related injury. N Engl J Med 2024;391:926–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2306867.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Silver, AH, Curley, M, Azzarone, G, Dodson, N, O’Connor, K. A parent survey assessing association of exposure to gun violence, beliefs, and physician counseling. Hosp Pediatr 2022;12:e95–111. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2021-006050.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Oddo, ER, Maldonado, L, Hink, AB, Simpson, AN, Andrews, AL. Increase in mental health diagnoses among youth with nonfatal firearm injuries. Acad Pediatr 2021;21:1203–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2021.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. DeMello, AS, Rosenfeld, EH, Whitaker, B, Wesson, DE, Naik-Mathuria, BJ. Keeping children safe at home: parent perspectives to firearms safety education delivered by pediatric providers. South Med J 2020;113:219–23. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001096.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Betz, ME, Azrael, D, Barber, C, Miller, M. Public opinion regarding whether speaking with patients about firearms is appropriate: results of a national survey. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:543–50. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-0739.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Haasz, M, Boggs, JM, Beidas, RS, Betz, ME. Firearms, physicians, families, and kids: finding words that work. J Pediatr 2022;247:133–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.05.029.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Magee, LA, Ortiz, D, Adams, ZW, Marriott, BR, Beverly, AW, Beverly, B, et al.. Engagement with mental health services among survivors of firearm injury. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2340246. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.40246.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Richards, JE, Kuo, ES, Whiteside, U, Shulman, L, Betz, ME, Parrish, R, et al.. Patient and clinician perspectives of a standardized question about firearm access to support suicide prevention: a qualitative study. JAMA Health Forum 2022;3:e224252. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4252.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Garbutt, JM, Bobenhouse, N, Dodd, S, Sterkel, R, Strunk, RC. What are parents willing to discuss with their pediatrician about firearm safety? a parental survey. J Pediatr 2016;179:166–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.08.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Office of the Controller, City of Philadelphia. Mapping Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis; 2024. https://controller.phila.gov/philadelphia-audits/mapping-gun-violence/#/?year=2023&layers=Point%20locations [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

31. Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. Gun violence in Philadelphia: mental health resources; 2024. https://pcomhealth.org/documents/mental-health-resources-gun-violence-pcom.pdf [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

32. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Guns safety campaign toolkit; 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/newsroom/campaigns-and-toolkits/gun-safety/ [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

33. UpTheBlock. Philly gun violence resources. Organizations. https://www.uptheblock.org/en/organizations/ [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fast facts: firearm injury and death; 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/firearm-violence/data-research/facts-stats/index.html [Accessed Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

35. Tolat, ND, Naik-Mathuria, BJ, McGuire, AL. Physician involvement in promoting gun safety. Ann Fam Med 2020;18:262–4. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2516.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Hudak, L, Schwimmer, H, Warnock, W, Kilborn, S, Moran, T, Ackerman, J, et al.. Patient characteristics and perspectives of firearm safety discussions in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med 2021;22:478–87. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.49333.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Lesnick, J, Abrams, LS, Angel, K, Barnert, ES. Credible messenger mentoring to promote the health of youth involved in the juvenile legal system: a narrative review. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2023;53:101435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2023.101435.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Martinez, R, McGilton, M, Gulaid, A. New York city’s wounded healers: a cross-program, participatory action research study of credible messengers. Urban Institute; 2022. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/opportunity/pdf/evidence/wounded-healers-finalreport-2022.pdf [Accessed Oct 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

39. Llovera, I, Ward, MF, Ryan, JG, LaTouche, T, Sama, A. A survey of the emergency department population and their interest in preventive health education. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:155–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00034.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Kreuter, MW, Wray, RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav 2003;27:S227–32. https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Haasz, M, Sigel, E, Betz, ME, Leonard, J, Brooks-Russell, A, Ambroggio, L. Acceptability of long versus short firearm safety education videos in the emergency department: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2023;82:482–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.03.023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Rein, AS, Ogden, LL. Public health: a best buy for America. J Public Health Manag Pract 2012;18:299–302. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e31825d25dd.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Shahtahmasebi, S. The good life: a holistic approach to the health of the population. Sci World J 2006;14:2117–32. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2006.341.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Sommer, M, Parker, R, editors. Structural approaches in public health, 1st ed. Routledge; 2013.10.4324/9780203558294Suche in Google Scholar

45. Eduardo Velasco-Mondragon, H, Menini, T, West, C, Clearfield, M. Public health and interprofessional education as critical components in the evolution of osteopathic medical education. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2018;118:753–63. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2018.161.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Zegarra-Parodi, R, Baroni, F, Lunghi, C, Dupuis, D. Historical osteopathic principles and practices in contemporary care: an anthropological perspective to foster evidence-informed and culturally sensitive patient-centered care: a commentary. Health (Basel) 2022;11:10. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Bowling, A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health 2005;27:281–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi031.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2024-0245).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- General

- Original Article

- Determining the effects of social media engagement on surgery residents within the American College of Osteopathic Surgeons

- Medical Education

- Commentary

- Pioneering the future: incorporating lifestyle medicine tools in osteopathic medical education

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Urinary incontinence in elite female powerlifters aged 20–30: correlating musculoskeletal exam data with incontinence severity index and survey data

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Effects of a single osteopathic manipulative treatment on intraocular pressure reduction: a pilot study

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Impact of a clinician-directed educational program on communicating with patients regarding gun violence at two community urban healthcare centers

- Clinical Image

- Pityriasis lichenoides chronica presenting in skin of color

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- General

- Original Article

- Determining the effects of social media engagement on surgery residents within the American College of Osteopathic Surgeons

- Medical Education

- Commentary

- Pioneering the future: incorporating lifestyle medicine tools in osteopathic medical education

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Urinary incontinence in elite female powerlifters aged 20–30: correlating musculoskeletal exam data with incontinence severity index and survey data

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Effects of a single osteopathic manipulative treatment on intraocular pressure reduction: a pilot study

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Impact of a clinician-directed educational program on communicating with patients regarding gun violence at two community urban healthcare centers

- Clinical Image

- Pityriasis lichenoides chronica presenting in skin of color