Effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment on children with plagiocephaly in the context of current pediatric practice: a retrospective chart review study

Abstract

Context

Deformational plagiocephaly (DP) is on the rise in pediatric patients. The current standard of care recommended for management is repositioning with possible addition of cranial orthoses. However, strong data are lacking to support these recommendations. Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is another treatment option for DP that is also lacking evidential support

Objectives

This retrospective chart review study investigated the effects of OMT at restoring a more symmetrical cranial bone configuration in children with DP.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed on medical records of patients with a diagnosis of DP from three private practices over a 4-year period from September 2017 to December 2021. Inclusion criteria were diagnoses of DP by a referring physician and aged 10 months or less at the time of initial evaluation and treatment. Patients were excluded if they had confounding diagnoses such as genetic syndromes or severe torticollis. A total of 26 patients met these criteria, and their records were reviewed. The main outcome reviewed was anthropometric assessment of the cranium, mainly the cranial vault asymmetry index (CVAI).

Results

Participants demonstrated a mean CVAI – a measure that determines the severity of DP – of 6.809 (±3.335) (Grade 3 severity) at baseline, in contrast to 3.834 (±2.842) (Grade 2 severity) after a series of OMT treatments. CVAI assessment after OMT reveals statistically significant (p≤0.001) decreases in measurements of skull asymmetry and occipital flattening. No adverse events were reported throughout the study period.

Conclusions

The application of OMT has shown potential benefit for reducing cranial deformity in patients with DP.

Nonsynostotic plagiocephaly, also commonly referred to as positional plagiocephaly or deformational plagiocephaly (DP), is described as an asymmetrical flattening of the cranium due to sustained external pressure. This cranial deformation can arise prenatally subsequent to uterine compression or intrauterine constraint, at birth from a difficult labor, or from delivery in which forceps or vacuum were utilized as well as acquired postnatally due to position [1, 2]. In pediatric practice, cranial dysmorphology includes the similar conditions of brachycephaly (flattening of the back of the head) and dolichocephaly (an abnormally long head). The newborn infant has a delicate cranial structure with patent sutures, designed to transit the birth canal with incompletely formed cranial bones. These bones are in part still formed of cartilage, which eventually ossify and join together forming a typical skull.

The prevalence of DP is reported to range between 20 and 30 % of live births [3, 4], and the highest reported peak is reached at age 4 months at a rate of 30–35 % [5], [6], [7], [8]. Since 1992 and the “Back to Sleep” program recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics [9], in response to the Sudden Unexplained Infant Deaths (SUIDs) crisis at that time, the incidence of nonsynostotic plagiocephaly has risen significantly [10], and discussion of what to do about it has followed [1]. Examples of typical pediatric normocephalic and plagiocephalic head configurations are shown in Figure 1.

Superior views of pediatric heads. (A) A 4-month-old with a normocephalic head. (B) An 11-month-old patient with asymmetrical deformational plagiocephaly (DP) and occipital flattening.

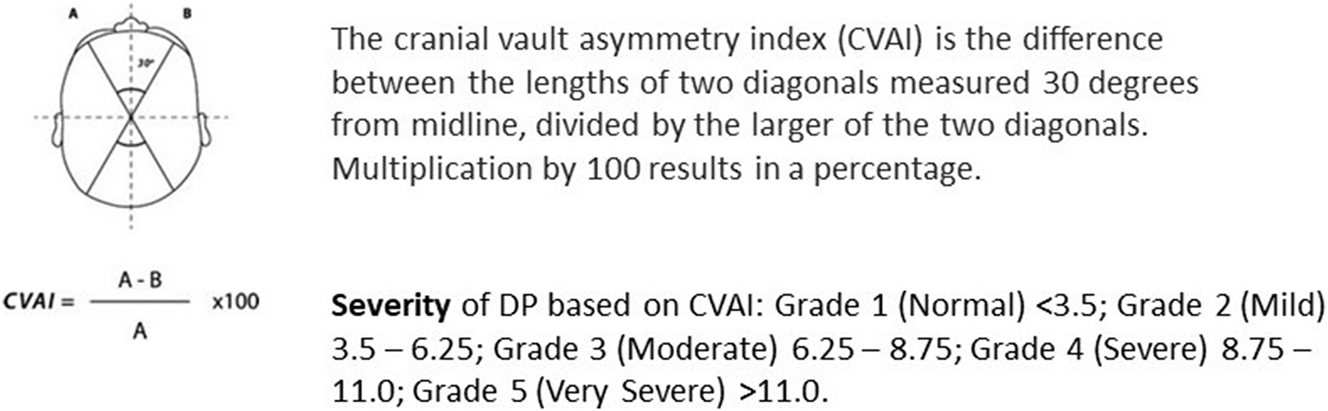

The current standard of practice for DP is repositioning so that the infant does not exacerbate the cranial dysmorphology by prolonged pressure of laying on the flattened part of the cranium. If the DP is of increased cranial vault asymmetry index (CVAI), it is common for referral to physical therapy, especially if the frequent concomitant condition of torticollis is present. Also, for the larger degrees of deformity, the infants may be referred for fitting of cranial orthoses, also referred to as a helmet or DOC Bands. The formula for calculating CVAI and definitions of severity are shown in Figure 2.

Diagram of head dimensions utilized in calculating the cranial vault asymmetry index (CVAI).

From the osteopathic medical perspective, there is reason to have concern for the effect of DP on infant physical development. H.I. Magoun, DO [11], discussed cranial dysfunctions in infants, “… adaptive deformities are all too soon a part of the permanent conformation. Many of these happening are sub-anatomical or are not considered important. The child will outgrow it, which is a cliché all too often leads to a life-long disability” [11]. In other words, families/patients are often advised that treatment is not needed, especially when the dysfunctions are not grossly apparent, which can have potential life-long consequences for the patient. Based on her research and clinical experience Viola M. Frymann, DO [12, 13], raised concerns about physical deformity and cognitive dysfunction arising from untreated DP. Dr. Frymann [12, 13] advocated early intervention, published the first data describing the cranial dysmorphology related to DP, and suggested that 75–85 % of newborns have identifiable cranial bone asymmetries [12]. This percentage range of possibly clinically significant dysmorphology was also reported in more recent research in 2008 at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine Dysmorphology Clinic, with 73 % reported with cranial asymmetry [14].

Physical and cognitive deficits reported in the literature for infants born with or who developed DP after birth include muscular conditions [15], hip dysplasia and club feet [16], postural abnormalities [17, 18], visual and auditory dysfunctions [19], [20], [21], mandibular asymmetry [22], and neurodevelopmental and cognitive deficits [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. Moderate to severe DP could lead to facial asymmetry (anterior shift of the ipsilateral forehead, ear, and cheek) with an asymmetric opening of the palpebral fissures and misalignment of the eyes and/or ears [6, 28]. These asymmetries could interfere with auditory processing and visual development [29]. The most common finding associated with plagiocephaly is congenital muscular torticollis [30].

An increasing number of studies show that DP is a risk factor for developmental delay in some motor, sensorial, and cognitive areas of development [29, 31], [32], [33]. Studies on school-age patients highlighted a relationship between DP and the need for interventions during the primary school years and special education services including speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy [34], [35], [36].

In an effort to mitigate the effects of DP, a consensus review by the Congress of Neurological Surgeons was published [37]. Treatment guidelines currently recommend physical therapy over “repositioning education alone for reducing prevalence of infantile positional plagiocephaly in infants 7 weeks of age … Furthermore, physical therapy is as effective for the treatment of positional plagiocephaly and recommended over the use of a positioning pillow in order to ensure a safe sleeping environment and comply with American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations.” [38]. Yet “repositioning is an effective treatment for DP … However … repositioning is inferior to physical therapy and the use of a helmet, respectively.” [39]. Despite findings discouraging the use of helmet therapy in infants with moderate to severe skull deformation, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons’ guidelines state, “Helmet therapy is recommended for infants with persistent moderate to severe plagiocephaly after a course of conservative treatment (repositioning and/or physical therapy). Helmet therapy is recommended for infants with moderate to severe plagiocephaly presenting at an advanced age.” [40].

Since the Congress of Neurological Surgeons treatment guidelines were published, the research literature on the effects of helmet orthosis does show cranial bone symmetry improvement [41, 42] in cases of PD. When treatments are compared, helmet orthosis may be more effective than postural repositioning [43]. When helmet orthosis and physical therapy were compared, there was no significant different between the two groups [44].

There is a small but increasing body of research on the application of osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT), especially osteopathic cranial manipulative medicine (OCMM) in pediatric patients with DP because of its relatively safe and noninvasive procedures. OMT is defined as “the therapeutic application of manually guided forces by an osteopathic physician to improve physiologic and/or support homeostasis that has been altered by somatic dysfunction.” [45, p. 1575].

The first empirical study was a case series of 12 infants aged 2–6 months diagnosed with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly in 2011 by Lessard et al. [46] They found significant improvement in anthropometric measurement of cranial shape as a result of osteopathic treatment with an emphasis on OCMM. In 2021, Gasperini et al. [47] reported a case series study of 37 infants diagnosed with DP who started the study at age 6 months or less and had a 1-year follow-up assessment. Anthropometric measures were taken at admission to the study and at 12 months, with an average of four to nine OMT sessions. Cranial symmetry was significantly improved. The only randomized clinical trial focused on plagiocephaly to date was conducted in 2022 by Bagagiolo et al. [48] They randomized 96 patients diagnosed with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly, 48 to the OMT group and 48 to sham light touch therapy (LTT). Each patient received six sessions of either OMT or LTT, and the OMT significantly reduced cranial asymmetries at both the 3-month and 1-year follow-up assessments, compared with LTT.

Based on the assessment of DP utilized in most studies, we have utilized the CVAI as the primary outcome measure. The CVAI calculates a ratio that correlates to a specific grade of deformation (grades 1–5). Grade 1 is <3.5, Grade 2 is 3.50–6.25 cranial vault asymmetry (CVA), Grade 3 is 6.25–8.75 CVA, Grade 4 is 8.76–11.0 CVA, and Grade 5 is >11.

The hypothesis for this study was that OMT would show benefit in the treatment of pediatric patients diagnosed with DP and would provide the basis for a subsequent prospective study.

Methods

Retrospective review

This is a retrospective chart review that was granted exempt status by UCSD IRB. The study had no external funding. Verbal consent was provided by the parents of the subjects prior to inclusion in this chart review, and no compensation was provided to these families. The three physicians (HHK, JM, MAMH) provided OMT, particularly OCMM, and reviewed the medical records and charts of the pediatric patients who presented with the diagnosis of DP made by the referring physician as the primary problem. The search criteria below were established prior to the chart review process.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were a previous diagnosis of DP by a referring physician, and age 10 months or less at the time of initial evaluation and treatment, which was the oldest patient any of the clinicians had with DP in their files.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were: previous OMT; any surgery since birth; any genetic condition, such as Down syndrome, at the time of referral; and the presence of severe torticollis as the primary reason for referral to OMT service.

Data extraction

From each chart, the following data were extracted: pre- and post-CVAI; five subjects were assessed by Cranial Technologies camera (CTC)-based system, while all others were assessed with standard caliper measure protocols; patient’s age at diagnosis/first treatment and final OMT session; number of OMT sessions; duration of treatment with OMT; OMT modalities utilized; and assigned sex of patient.

Treatment

Upon chart review, it was noted that each OMT session lasted between 25 and 40 min. The OMT techniques performed emphasized OCMM, but also included balanced membrane tension (BMT, which is “any OCMM method in which the goal of treatment is to achieve a state in which the affected craniosacral structures are equalized in all appropriate planes.” [45]), soft tissue, and myofascial release based on individual assessment of somatic dysfunction. Each patient was treated according to the structural needs of the child. OCMM was typically focused on head and neck structures. BMT, soft tissue, and myofascial release were typically applied on spinal structures including the sacrum and ribs as well as respiratory and pelvic diaphragms.

Data acquisition

As the opportunity for carrying out a retrospective chart review was agreed upon by the three osteopathic physicians, all the parents of the patients were contacted and provided verbal consent to utilize the patients’ de-identified data. For patients who were referred to our practices after we started the chart review, the parents gave verbal consent as soon as it was determined that the patient met the inclusion criteria. For the data analysis, all patient identifiers were removed before submission to the study biostatistician for analysis.

Deformational plagiocephaly assessment

Five of the patients were assessed by the CTC-based system, and 18 were assessed according to the standard protocol for the use of calipers based on availability of these devices in each of the three practices. The standard caliper research protocol was three measurements of the anterior–posterior and lateral dimensions of the head and the value for the assessment was the average of the three measurements. Subjects who were measured by the standard caliper protocol received the measurements at the initial OMT session and at the last OMT session. The subjects with the CTC measurements were seen for their first (OMT) visit within 2 weeks of the initial measurements, and the posttreatment CTC measures were within 2 weeks of the last OMT session. All eight subjects assessed by CTC imagery were from practices (HHK and MAH) who had participants referred for services who had already had initial CTC assessment or were able to obtain the assessments readily. In one practice (JM), only the caliper assessment was available.

Statistical analyses

Demographic data were analyzed via descriptive statistics and presented as ratios, frequencies, means, standard deviations, percent change, and range. Summary statistics were calculated for all recorded data and were presented as frequencies and percentages. Means and standard deviations are presented for continuous variables. Point estimates of the changes were calculated for primary outcomes. The normality of the data distribution was assessed utilizing a Shapiro–Wilk test. A paired t test for normally distributed differences was utilized to compare quantitative outcomes before and after the OMT intervention. All p values were based on two-sided tests and compared at a significance level of 5 %. All statistical tests were performed a 5 % significance level utilizing STATA 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) statistical software. All raw and calculated data were secured in a password-protected Microsoft Excel electronic database.

Results

From the practices of the OMT physicians, the charts of 26 pediatric patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified. Table 1 describes the demographics of the patients and nature of the treatment provided. This included 19 males and seven females, who began their first OMT session between the ages of 2 and 10 months (mean 4.4 months) and completed their final OMT session between the ages of 3 and 13.5 months (mean 7 months). The number of OMT sessions received ranged from 4 to 10 sessions and occurred at weekly or biweekly intervals as determined individually by the three osteopathic practitioners. The average number of OMT sessions for the group was 7.35. The percentage of males to females in this study (73 %) is consistent with occurrence data reported in other studies [3].

The demographics of the patients and nature of the treatment provided.

| Characteristic | N=26 |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD), [range] | |

| Males | 19 (73 %) |

| Age during first treatment, months | 4.4 (2.2), [2–10] |

| Age during last treatment, months | 7.0 (3.2), [2.3–13.5] |

| Treatment duration, months | 2.8 (2.6), [0.5–10] |

-

SD, standard deviation.

A comparison of outcome measures before and after the OMT sessions demonstrated that OMT significantly reduced skull asymmetry as measured by CVAI (p<0.001). Also, occipital flattening was reduced, and head circumference was increased (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Results.

| Variable | Pre-OMM | Post-OMM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), [range in mm] | Mean (SD), [range in mm] | ||

| Diagonal A, mm | 133.3 (±10.4), [114–156] | 139.6 (±10.6), [120–158] | <0.001 |

| Diagonal B, mm | 137.7 (±8.6), [125–153] | 142.2 (±10.4), [124–159] | <0.001 |

| Circumference, mm | 417.0 (±25.7), [365–460] | 435.0 (±25.7), [380–470] | <0.001 |

| Cephalic index | 0.968 (±0.07), [0.89–1.16] | 0.983 (±0.04), [0.93–1.13] | 0.088 |

| CVAI | 6.809 (±3.335), [1.53–15.6] | 3.834 (±2.842), [0.65–12.9] | <0.001 |

| Severity grade | 3 [1–5] | 2 [1–5] |

-

CVAI, cranial vault asymmetry index; OMM, osteopathic manipulative medicine; SD, standard deviation.

The 26 participants demonstrated a mean CVAI of 6.809 (±3.335) (Grade 3 severity) at baseline, in contrast to 3.834 (±2.842) (Grade 2 severity) after the series of OMT treatments. No adverse events or side effects of OMT were reported throughout the study period.

Discussion

The results of the retrospective chart review provided data showing the improvement in cranial symmetry and reduction in severity level of plagiocephaly measured before and after a series of OMT sessions. This supports findings of previous studies that showed improved cranial symmetry as a result of OMT [46], [47], [48]. While there was a statistically significant decrease in CVAI severity from a Grade 3 to Grade 2, it should be noted that the final average grade of severity for the participants in this study of 3.824 is very close to grade 1 severity – normal of CVAI <3.5. The degree of improvement shown by the significant reduction in the grade of severity (3 to 2) is not reported in the course of untreated DP or use of orthoses [5, 8]. Whether or not such reductions in CVAI would mitigate against the emergence of developmental or cognitive dysfunction [12, 13, 15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29, 31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36] is not possible to evaluate in this study. While reports of parental satisfaction with cranial dysmorphology suggested by reduction of CVAI from Grade 3 severity to Grade 2 (and almost to Grade 1) were not recorded systematically in the patient’s charts, this was mentioned by a number of parents to the treating clinicians anecdotally. It is worth noting that the changes reported were brought about by the application of OMT as contrasted with any other intervention.

The statistically improved cranial circumference appeared to reflect normalization of the patient’s cranial bone alignment [49]. The increase in head circumference may have also represented normalization of cranial bone configuration possibly due to reduced asymmetry and less sutural restriction, and it did not put the children into a macrocephalic category or on a concerning trajectory.

Limitations of the study include the design itself, a retrospective chart review that has limited value given a lack of a control group, potential recall and selection bias, and lack of a formal study design. The data collected in a retrospective study are dependent on a provider recording the given variables. This allows for potentially inconsistent data measurement and misattribution of diagnoses between providers in addition to variable patient follow-up. The number of patients is a moderate-sized cohort but typical of studies of this nature. There were two different cranial anthropometric assessment types utilized, the caliper measurement protocol and the camera-based technology. Although it is reported that that there is no statistical difference in anthropometric measures of the head by calipers or electronic devices [50], there could be differences affecting the final dataset.

There is still disagreement in the pediatric literature over the use of helmet orthoses, which are still widely utilized in clinical practice. Concerns remain over possible physical and cognitive deficiencies due to DP and the use of helmet orthoses, as previously mentioned. If further research continues to find these deficiencies, alternatives may need to be developed. We suggest that including the application of OMT in the treatment of DP may be a viable solution. Further prospective study design research is indicated and planned by this research group.

Conclusions

OMT is a safe treatment to consider in the management of DP. This retrospective chart review shows promising data in improving the CVAI in infants with DP with gentle OMT such as OCMM and BMT. Additional research is needed to determine how OMT compares to the current recommended treatments of repositioning and cranial orthoses. The use of objective measurements in a population not susceptible to a placebo effect also stands to benefit the field of osteopathic research as a whole.

-

Research ethics: This retrospective chart review received exempt status from the UCSD IRB (#807596).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: HHK, JM, MAMH, and MS provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of data. MS provided statistical analysis and contributed to the formulation of the results section and figures. HHK and KW drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. HHK and KW gave final approval for the version of the article to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None declared.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Laughlin, J, Luerssen, TG, Dias, MS. Prevention and management of positional skull deformities in infants. Pediatrics 2011;128:1236–41. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2220.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Ellwood, J, Draper-Rodi, J, Carnes, D. The effectiveness and safety of conservative interventions for positional plagiocephaly and congenital muscular torticollis: a synthesis of systematic reviews and guidance. Chiropr Man Ther 2020;38:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-020-00321-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Mackel, CE, Bonnar, M, Keeny, H, Lipa, BM, Hwang, SW. The role of age and initial deformation on final cranial asymmetry in infants with plagiocephaly treated with helmet therapy. Pediatr Neurosurg 2017;52:318–22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479326.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. van Wiik, RM, van Vlimmerman, LA, Groothuis-Oudshoorn, CG, Van Der Ploeg, CP, Izerman, MJ, Boere-Boonekamp, MM. Helmet therapy in infants with positional skull deformation: randomized controlled trial. Br Med J 2014;348:2741. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2741.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. van Vlimmerman, LA, van der Graaf, Y, Boere-Boonekamp, MM, L’Hoir, MP, Engelbert, RH. Risk factors for deformational plagiocephaly at birth and at 7 weeks of age: a prospective cohort study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e408–18. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Peitsch, WK, Keefer, CH, LaBrie, RA, Mulliken, JB. Incidence of cranial asymmetry in healthy newborns. Pediatrics 2002;110:e72. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.110.6.e72.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Rogers, GF. Deformational plagiocephaly, brachycephaly, and scaphocephaly. Part I: terminology, diagnosis, and etiopathogenesis. J Craniofac Surg 2011;22:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f6c313.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. DiRocco, F, Ble, V, Beuriat, PA, Szathmari, A, Lohkamp, LN, Mottolese, C. Prevalence and severity of positional plagiocephaly in children and adults. Acta Neurochir 2019;161:1095–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-019-03924-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. AAP. American Academy of pediatrics AAP task force on infant positioning and SIDS. Pediatrics 1992;89:1120–6.10.1542/peds.89.6.1120Suche in Google Scholar

10. Habal, MB, Castelano, C, Hemkes, N, Scheuerle, J, Guilford, AM. In search of causative factors of deformational plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg 2004;15:835–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001665-200409000-00025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Magoun, HI. Osteopathy in the cranial field, 3rd ed. Meridian, Idaho: The Cranial Academy; 1976.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Frymann, VM. Relation of disturbances of the craniosacral mechanism to symptomatology of the newborn: study of 1250 infants. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1966;65:1059–75.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Frymann, VM. Learning difficulties of children viewed in the light of the osteopathic concept. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1976;76:712–20.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Stellwagen, L, Hubbard, E, Chambers, C, Jones, KL. Torticollis, facial asymmetry and plagiocephaly in normal newborns. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:827–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.124123.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Biggs, WS. Diagnosis and management of positional head deformity. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1953–6.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Watson, G. Relation between side of plagiocephaly, dislocation of hip, scoliosis, bat ears, and sternomastoid tumours. Arch Dis Child 1971;46:203. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.46.246.203.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Moss, SD. Nonsurgical, nonorthotic treatment of occipital plagiocephaly: what is the natural history of the misshapen neonatal head? J Neurosurg 1997;87:667–70. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1997.87.5.0667.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Hylton, N. Infants with torticollis: the relationship between asymmetric head and neck positioning and postural development. Phy Occup Ther Pediatr 1997;17:91–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/J006v17n02_06.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Siatkowski, RM, Fortney, AC, Nazir, SA, Cannon, SL, Panchal, J, Francel, P, et al.. Visual field defects in deformational posterior plagiocephaly. J AAPOS 2005;9:274–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.01.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Gupta, PC, Foster, J, Crowe, S, Papay, FA, Luciano, M, Traboulsi, EI. Ophthalmologic findings in patients with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg 2003;14:529–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001665-200307000-00026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Balan, P, Kushnerenko, E, Sahlin, P, Huotilainen, M, Näätänen, R, Hukki, J, et al.. Auditory ERPs reveal brain dysfunction in infants with plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg 2002;4:521–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001665-200207000-00008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. John, DS, Mulliken, JB, Kaban, LB, Padwa, BL. Anthropometric analysis of mandibular asymmetry in infants with deformational posterior plagiocephaly. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;60:873–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/joms.2002.33855.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Kordestani, RK, Patel, S, Bard, DE, Gurwitch, R, Panchal, J. Neurodevelopmental delays in children with deformational plagiocephaly. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:207–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000185604.15606.e5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Knight, SJ, Anderson, VA, Meara, JG, Da Costa, AC. Early neurodevelopment in infants with deformational plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg 2013;24:1225–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e318299777e.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Collett, BR, Starr, JR, Kartin, D, Heike, CL, Berg, J, Cunningham, ML, et al.. Development in toddlers with and without deformational plagiocephaly. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:653–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.92.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Martiniuk, ALC, Vujovich-Dunn, C, Park, M, Yu, W, Lucas, BR. Plagiocephaly and developmental delay: a systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2017;38:67–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000376.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Cabrera-Martos, I, Valenza, A, Benítez-Feliponi, C, Robles-Vizcaíno, A, Ruiz-Extremera, G, Valenza, D. Clinical profile and evolution of infants with deformational plagiocephaly included in a conservative treatment program. Childs Nerv Syst 2013;29:1893–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-013-2120-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Cavalier, A, Picot, MC, Artiaga, C, Mazurier, E, Amilhau, MD, Frove, E, et al.. Prevention of deformational plagiocephaly in neonates. Early Hum Dev 2011;87:537–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.04.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Hutchison, BL, Stewart, AW, Mitchell, E. Deformational plagiocephaly: a follow-up of head shape, parental concern and neurodevelopment at ages 3 and 4 years. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:85–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2010.190934. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2010.190934.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Nilesh, K, Mukherji, S. Congenital muscular torticollis. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2013;3:198–200. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0746.119222.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Fontana, SC, Daniels, FD, Greaves, T, Nazir, N, Searl, J, Andrews, BT. Assessment of deformational plagiocephaly severity and neonatal developmental delay. J Craniofac Surg 2016;27:1934–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000003014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Hussein, MA, Woo, T, Yun, IS, Park, H, Kim, YO. Analysis of the correlation between deformational plagiocephaly and neurodevelopmental delay. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2018;71:112e117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2017.08.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Collett, BR, Gray, KE, Starr, JR, Heike, CL, Cunningham, ML, Speltz, ML. Development at age 36 months in children with deformational plagiocephaly. Pediatrics 2013;131:e109–15. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1779.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Collett, BR, Breiger, D, King, D, Cunningham, M, Speltz, M. Neurodevelopmental implications of “deformational” plagiocephaly. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2005;26:379–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200510000-00008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Andrews, BT, Fontana, SC. Correlative vs causative relationship between neonatal cranial head shape anomalies and early developmental delay. Front Neurosci 2017;11:708. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00708.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Collett, BR, Gray, KE, Starr, JR, Heike, CL, Cunningham, ML, Speltz, ML. Development at age 36 months in children with deformational plagiocephaly. Pediatrics 2013;131:e109–15. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1779.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Flannery, AM, Tamber, MS, Mazzola, C, Klimo, PJr, Baird, LC, Tyagi, R, et al.. Congress of Neurological Surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guideline for the diagnosis of patients with positional plagiocephaly: executive summary. Neurosurgery 2016;76:623–4. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000001426.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Baird, LC, Klimo, P, Flannery, AM, Bauer, DF, Beier, A, Durham, S, et al.. Congress of neurological surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guideline for the diagnosis of patients with positional plagiocephaly: the role of physical therapy. Neurosurgery 2016;76:E630–1. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000001429.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Klimo, P, Lingo, PR, Baird, LC, Bauer, DF, Beier, A, Durham, S, et al.. Congress of neurological surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guideline for the diagnosis of patients with positional plagiocephaly: the role of repositioning. Neurosurgery 2016;76:E627–9. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000001428.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Tamber, MS, Nikas, D, Beier, A, Baird, LC, Bauer, DF, Durham, S, et al.. Congress of Neurological Surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guideline on the role of cranial molding orthosis (helmet) therapy for patients with positional plagiocephaly. Neurosurgery 2016;76:E632–3. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000001430.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Lam, S, Pan, I-W, Strickland, BA, Hadley, C, Daniels, B, Brookshier, J, et al.. Factors influencing outcomes of the treatment of positional plagiocephaly in infants: a 7-year experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2017;19:273–81. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.9.PEDS16275.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Takamatsu, A, Hikosaka, M, Kaneko, T, Mikami, M, Kaneko, A. Evaluation of the molding helmet therapy for Japanese infants with deformational plagiocephaly. JMA J 2021;4:50–60. https://doi.org/10.31662/jmaj.2020-0006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Wen, J, Qian, J, Zhang, L, Ji, C, Guo, X, Chi, X, et al.. Effect of helmet therapy in the treatment of positional head deformity. J Paediatric Child Health 2020;56:735–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14717.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Gonzalez-Santos, J, Gonzalez-Bernal, J, Anuncibay, RD, Soto-Cámara, R, Cubo, E, Aguilar-Parra, JM, et al.. Infant cranial deformity: cranial helmet therapy or physiotherapy? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072612.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Seffinger, MA, editor. Foundations of osteopathic medicine, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Lessard, S, Gagnon, I, Trottier, N. Exploring the impact of osteopathic treatment on cranial asymmetries associated with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly in infants. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2011;17:193–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2011.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Gasperini, M, Vanacore, N, Massimi, L, Consolo, S, Haass, C, Scarillati, ME, et al.. Effects of osteopathic approach in infants with deformational plagiocephaly: an outcome research study. Minerva Pediatr 2021. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-5276.21.06588-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Bagagiolo, D, Priolo, CG, Favre, EM, Pangallo, A, Didio, A, Sbarbaro, M, et al.. A randomized controlled trial of osteopathic manipulative therapy to reduce cranial asymmetries in young infants with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly. Am J Perinatol 2022;39:S52–62. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-175872.Suche in Google Scholar

49. Wolf, K. Reshaping plagiocephaly in pediatrics…literally! In: Abstract and Poster presented at American College of Osteopathic Pediatricians/American Academy of Pediatrics (Section on Osteopathic Pediatricians) meeting. Columbus, Ohio: American College of Osteopathic Pediatricians; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Wu, GT, Audlin, JR, Grewal, JS, Tatum, SA. Comparing caliper versus computed tomography measurements of cranial dimensions in children. Laryngoscope 2021;131:773–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29086.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- The impact of emergency medicine residents on clinical productivity

- Clinical Practice

- A superficial dissection approach to the sphenopalatine (pterygopalatine) ganglion to emphasize osteopathic clinical relevance

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Effect of osteopathic manipulative treatment and Bio-Electro-Magnetic Energy Regulation (BEMER) therapy on generalized musculoskeletal neck pain in adults

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Brief Report

- Augmentation of immune response to vaccinations through osteopathic manipulative treatment: a study of procedure

- Pediatrics

- Original Article

- Effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment on children with plagiocephaly in the context of current pediatric practice: a retrospective chart review study

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Commentary

- Telehealth in opioid use disorder treatment: policy considerations for expanding access to care

- Clinical Image

- Traumatic tattooing: case description and a comprehensive review of the therapeutic management

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- The impact of emergency medicine residents on clinical productivity

- Clinical Practice

- A superficial dissection approach to the sphenopalatine (pterygopalatine) ganglion to emphasize osteopathic clinical relevance

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Effect of osteopathic manipulative treatment and Bio-Electro-Magnetic Energy Regulation (BEMER) therapy on generalized musculoskeletal neck pain in adults

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Brief Report

- Augmentation of immune response to vaccinations through osteopathic manipulative treatment: a study of procedure

- Pediatrics

- Original Article

- Effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment on children with plagiocephaly in the context of current pediatric practice: a retrospective chart review study

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Commentary

- Telehealth in opioid use disorder treatment: policy considerations for expanding access to care

- Clinical Image

- Traumatic tattooing: case description and a comprehensive review of the therapeutic management