Abstract

This article examines the language shift and the accompanying changing status of French and German in the Erlangen Huguenot community (southern Germany) during the approximately 150 years following the first French immigrants settling in Erlangen in 1686. Our quantitative analysis is based on a diachronically-balanced corpus of 314 archival sources transmitted from this community and provides an overview of the language shift from French to German over time. The linguistic choices are influenced by the social group of the writers and addressees, the direction of communication and the domain of the texts. Our qualitative analysis focuses on multilingual texts and linguistic practices throughout the time period examined and traces the changing status of the two languages in the community, from French as the dominant language in the earlier years, to the use of German in conceptually oral texts with retention of French in school contexts and by the consistory, to French as a social symbol of the intellectuals in the early 19th century. Our paper provides empirical accounts for an under-researched context of language shift and contributes to historical sociolinguistic research on historical language contact, multilingualism, and linguistic identity.

1 Introduction[1]

The Huguenot migration in the sixteenth and seventeenth century played an important role in the spread of French in Europe and contributed to the phenomenon of the European francophonie, i.e., the use of French in European language communities outside France (Argent et al. 2014: 1). The Huguenots also carried the language into the middle and lower social classes that had not been in contact with French before (von Polenz 2020: 114). Among the Huguenots, the French language had a group-constituting function and was, together with their religion, their most important sign of identity (Glück 2002: 166). At the same time, being a cultural and linguistic minority led to acculturation processes and subsequent language shift, particularly in the smaller and rural Huguenot communities (Böhm 2010). This article concentrates on the southern German Huguenot community in Erlangen, founded in 1686, when an increasing number of Huguenot refugees were attracted to settle in this town. By focussing on a considerable number and variety of texts written both inside the community and correspondence to and from the Huguenots, this paper examines the language shift and the accompanying changing status of French and German in this community during their acculturation.

Section 2 gives an overview of the socio-historical background of the Erlangen Huguenot community and the research context. Section 3 presents our corpus with both its possibilities and limitations. Our analysis of 314 archival sources in Section 4 allows for a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. Section 5 presents the results of our study. Quantitative analyses (Section 5.1) provide insights into the language shift process in general and language-external factors influencing this process: the social group of the writers and addressees, the direction of communication, and the domain of the text. The qualitative analyses (Section 5.2) trace the changing status of French from the dominant language in the earlier years, to a religious and an increasingly social symbol of intellectuals during the times of acculturation and language loss in the broader community in the later 18th and early 19th century. Section 6 discusses the findings and concludes the article.

2 Background

2.1 Socio-historical background

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes under Louis XIV in 1685 formally ended a time of religious tolerance in France, which resulted in around 150,000–200,000 so-called Huguenot refugees, a religious group that shared the Reformed or Calvinist faith, who fled France and settled in surrounding European countries (Petersilka 2019: 214). As the devastating economic and demographic consequences of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) had not been overcome by this time, skilled labourers were attracted by privileges that were granted for their religious practices and commercial activities at numerous places. Following that strategy, Christian Ernst, margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth attracted approximately 1,000–1,500 Huguenot refugees to his territory. From 1686, most of them settled in the southern German town of Erlangen, where a new, independent district, Christian-Erlang, was founded. The refugees were granted several privileges, in particular the same rights as the native population, places for settlement, freedom of religion, and financial support (Jakob 2016: 184). The Huguenots brought with them not only their expertise in novel crafts, particularly stocking and glove fabrication, but also their religious and French linguistic identity.

The Huguenots came into regular contact with speakers of German, not only in trade but also in their private lives, as an increasing number of Germans settled in their town district. While in 1698 there were three times more Huguenots (1,000) than Germans (317), by 1723 the number of Huguenots remained roughly the same. Twice as many Germans (2,154) as Huguenots (1,028) had settled there in the intervening period (Bischoff 1982: 68). Several of the Germans were also migrants with a reformed confession who enjoyed the same privileges in Erlangen (Bischoff 1982: 87). The Germans often participated in the craft of the stocking makers. While there were no German stocking makers in the 17th century (but 23 French ones by 1699), by 1723 there were 63 German and 96 French registered faiseurs de bas (Bischoff 1981: 125). During the 18th century, the numbers of Huguenot master craftsmen decreased sharply (Yardeni 1986: 157). Glove fabrication, in contrast, remained a purely Huguenot profession until 1814 (Petersilka 2019: 218), so that its technical vocabulary was French, remaining in partial use until the 20th century (Barth 1945: 86; Firnstein 1981: 4; Göhring 1925).

While in most areas of fabrication and commerce we can observe close contacts between the Huguenots and the Germans, there was a clear separation of the communities in school and church contexts, where the Huguenots sought to retain their French culture and identity. Already in the year of their arrival, in 1686, they had founded a French reformed school (école française) (Bischoff 1982: 82). Also in 1686, the foundation stone was laid for the Huguenot Church in their new town district, inaugurated in 1693 (Bischoff 1986: 206). It was administrated by the French reformed community, led by a consistory with the two pastors and ten Anciens, i.e., the oldest members of the community (Bischoff 1982: 86).

In the early 18th century, the French language flourished in Erlangen, and the possibility of learning French was one of the arguments for moving the new university from Bayreuth to Erlangen in 1743 (Petersilka 2019: 219). Its first chancellor Daniel de Superville was a Huguenot (Yardeni 1986: 154). The size of the French community continually declined, while intermarriages between Huguenot descendants and Germans were increasing (Yardeni 1986: 158). For example, between 1790 and 1819, around 80% of the men with French names married wives with a German name (38 out of 47) (Bischoff 1982: 69), which was a further driver of integration into the German-speaking community and towards language shift. In his travel diary, Pastor Füssel (1788: 313) characterized Erlangen’s French reformed community as a “schmelzende Kolonie” ‘melting colony’ (Petersilka 2019: 219). With 213 members, the French reformed community formed only 2.5% of Erlangen’s population in 1810 (Bischoff 1982: 68). The privileges existed until 1810, when Erlangen was placed under Bavarian sovereignty (Yardeni 1986: 159). In 1812, Christian-Erlang lost its independence, and the two parts of the town were united (Bischoff 1982: 114). The Napoleonic era led to a decline of Erlangen’s textile industry and a lack of interest in the French language and culture in the early 19th century (Petersilka 2019: 221). The French reformed school was closed in 1817 (Bischoff 1982: 82) and the reduced competence in French among the majority of the community eventually led to a shift to German in church services in 1822 (Ebrard 1885: 137).[2]

2.2 Research context

This paper contributes to research on historical multilingualism, language shift and linguistic identity. In her sociolinguistic studies, Böhm examines how socio-cultural factors led to an acculturation and language shift in Huguenot communities in German-speaking areas: Brandenburg-Prussia (Böhm 2010) and Hesse (Böhm 2016). She finds that smaller rural communities facilitated the acculturation of the Huguenots. Their everyday contacts with the German population led to multilingualism, diglossia, and a quick language shift to German. Thus, in the rural community of Strasburg/Uckermarck, this shift appeared within three generations, while in the large Huguenot community in Berlin with approximately 7,000 immigrants, the cultural elite maintained their French language as a symbol of identity for almost five generations (Böhm 2010: 520).[3] Böhm’s work refutes the general assumption, still found in language contact research (e.g., Romaine 2013: 324), of language shift, i.e., the “change from the habitual use of one language to that of another” (Weinreich 1953: 68), always being completed within three generations.[4]

Language shift is thus a complex phenomenon, as it is linked to different practices of multilingualism and individual linguistic choices. Research has shown that language shift cannot be grasped with a “purely generational analysis”, as this would leave “sufficient unexplained variance” (Fishman 1966: 31). Language shift is neither linear nor gradual, but encompasses discontinuities, as we may observe speakers with different linguistic competences at any point in time (Myers-Scotton 1992: 52). Rather, it should be considered a “longue durée phenomenon” (Böhm 2016: 321).

In Huguenot communities, language shift has shown to be influenced by “various domains, language situations, sociocultural and local conditions, and form (spoken/written)” (Böhm 2016: 321). There is a general lack of informal and private texts of conceptual orality (Koch and Oesterreicher 1985) from Huguenots, as they have only rarely been stored in the official archives (Böhm 2010: 202; Eschmann 1989: 21). This makes it difficult to trace the language shift in the spoken medium. Metalinguistic remarks on the use of the two languages may provide further insights. The socio-cultural and local conditions of the Erlangen community were described in the previous section, being different to the ones analysed in Böhm’s studies, as the socio-cultural contexts were neither urban as in Berlin nor rural as in Strasburg/Uckermark. Rather, manufacturing and commerce characterized the new town district Christian-Erlang, before the residency of the Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth was established in the newly built castle (1700–1703) and Erlangen became an intellectual centre with the foundation of the university in 1743 (Petersilka 2019: 218). The influencing factors of domains and language situations (i.e., the social group of the writers/addressees and the direction of communication) will be discussed in Section 4 on methodology.

Linguistic identity is a further important aspect that is inseparably linked to the Huguenots’ language use. Particularly in contexts of migration, a common language acquires group-constituting status as a means of both identification and demarcation (Ehlich 1996: 189). For the Huguenots, French was also their language of religion. Being religious migrants, religious practice was inseparably associated with the Huguenots’ identity (Böhm 2010: 72, 2016: 316). This explains the long retention of French in religious contexts. Preserving a group identity also had a practical aspect for the Huguenots, as it was a prerequisite for defending their privileges (Böhm 2010: 72; Yardeni 1986: 158).

2.3 Linguistic research on Huguenot communities in Germany

While the historical contexts of the Huguenot migration have been investigated extensively,[5] Böhm (2016: 299) notes that, apart from her own studies, “it is astonishing how little research has been done on the language situation of Huguenot communities”. Most linguistic research follows a Romance perspective and is interested in dialect levelling and the so-called Style Réfugié (e.g., Hartweg 2005). Earlier research saw the German influences in the Huguenot texts as language decay, neglecting their potential for contact linguistics (Glück 2002: 193).

Despite the importance of the Huguenot migration for Erlangen’s history and its prominence in the city’s public consciousness, linguistic research is scarce and has focused only on selected sources: Barth’s (1945) dissertation is the first comprehensive study on the linguistic and cultural integration of Huguenots in Erlangen, with a focus on the latter. While she relies on several archival sources that provide insights into language use in diverse contexts, her general linguistic results are vague and blurred by the linguistic ideology of language decay (cf. similarly, Yardeni 1986: 158). Bischoff’s several publications on the Erlangen Huguenots have a socio-historical perspective and only rarely discuss linguistic aspects (but see Bischoff 1981). Local historians have occasionally commented on language-related topics (e.g., Deuerlein 1926; Göhring 1925; Maas 1991). Eschmann (1989: 21) briefly reports from his examination of protocols by Erlangen Huguenot notaries (1686–1721), where he encountered the use of standard French. Petersilka (2018a, 2018b, 2019 examines the history, language use and publications of the Meynier family (cf. Section 5.2.4). Schöntag (2022) provides a general historical overview of French influences on German with a focus on Bavaria. In general, the focus of linguistic research merely on selected sources has led to a fragmented view of language shift in the Erlangen Huguenot community that we intend to broaden by our corpus-based approach.

3 Corpus

Historical sources from the Erlangen Huguenot community are predominantly stored in three archives: the city archive of Erlangen (Stadtarchiv Erlangen; in the following cited as Erl), the protestant church archive in Nuremberg (Landeskirchliches Archiv der Evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirche in Bayern; cited as Nbg), and the State Archive Bamberg (Staatsarchiv Bamberg; cited as Bam).[6] For the quantitative analyses of this article, a sample of 314 sources from the first two archives was examined, covering the period from 1685 to the 1840s.[7] As the archive in Bamberg comprises only material up until the 1720s, the documents were not included in the quantitative study to avoid a temporal bias. Nevertheless, a sample from the 16 extensive volumes of documents was reviewed and deemed useful for our qualitative analyses.[8] As the archive in Erlangen holds mainly secular texts and the material from Nuremberg is predominantly religious, the two archives complement each other, providing a large variety of documents.

The appendix lists the signatures of the archival files selected as the basis for this paper. In the city archive of Erlangen, documents from the Huguenot community are not grouped together in a separate archival record, which required consultations of several potentially relevant sources, such as collections from professions practised by the Huguenots (e.g., stocking, glove and hat makers, tanners, merchants, notaries, priests, language teachers), documents from prominent families in Erlangen and records of autographs. Exhibition catalogues also led to some sources. In contrast, the archive in Nuremberg provides one archival record for the former Huguenot parish (Findbuch 50/840 für das Archiv der Evangelisch-Reformierten Gemeinde Erlangen). Due to the large amount of material, it was not possible to consult every file listed in this record. To achieve a temporal balance, a random sample of files was consulted, containing documents covering the whole time period investigated. Some of the files seem incomplete but were nevertheless examined as they included material from relevant contexts like the school.[9]

In comparison to the data for Böhm’s (2010) study on other Huguenot communities (cf. Section 2), the texts from Erlangen have a stronger secular focus with a high number of business-related texts, a central aspect for the Huguenots’ life in Erlangen. The transmission of religious texts seems to be similar in quantity and in text types, which allows for comparisons with Böhm’s results. Private texts or texts of conceptual orality are also very rarely transmitted from the Erlangen community but may provide some glimpses into the shift to German in different domains (cf. Section 5.2.2). In contrast to Böhm’s corpus, texts related to the school context are scarce in the sources consulted from Erlangen with only a small number of documents, which, however, do provide some interesting evidence for prevailing multilingualism in the early 19th century (cf. Section 5.2.3). As we were not able to review the material completely, there may be more informal texts and data from the school context outside of our archival sample. In the qualitative analyses, we also refer to additional published sources and findings in secondary literature.

4 Methodology

For a general overview, we are firstly interested in the proportion of French, German and multilingual texts throughout the approximately 150-year time period. Consequently, language is the dependent variable of our quantitative analyses in Section 5.1. The main independent variable is time. As our corpus shows a rather good diachronic balance, we are able to compare smaller time segments. Thus, each text is annotated with the decade of writing. To conduct more detailed analyses, the influence of further factors is examined, which are derived from language-external characteristics: (a) the social group of the writers and addressees, (b) the direction of communication, and (c) the domain of the text. These three factors are not independent but rather influence each other, particularly domain and addressee. Due to the uneven distribution of data, we cannot apply statistical methods to analyse the different variables together but analyse the results for each variable separately and provide qualitative detail. The three factors are developed in the following.

Social group: Around two thirds of the texts examined were written by Huguenots. As it also seems relevant to analyse the development of the language in which the Huguenots were addressed, we additionally considered documents from outside the Huguenot community, such as declarations by the margrave or letters from the German reformed church community. Despite being highly diverse groups with members from different professions, for our quantitative analysis it seems reasonable to differentiate the two groups, i.e., the (descendants of) Huguenots and the Germans. Similarly, the addressees of the texts were also annotated and stem from both groups. There are some texts without a direct addressee, but which concern the Huguenots’ life such as the guild laws. They were not written by the Huguenots themselves but play an important part in their lives in Erlangen, which makes them worth examining (cf. Section 5.2).

Direction of communication: With regard to the direction of communication, we differentiate between internal, outgoing and incoming communication. Internal communication comprises texts written inside the Huguenot community between different members of the community and/or the pastor, or texts without an addressee but a function within the community, such as protocols, lists and commentaries on incoming texts. Outgoing communication consists predominantly of letters directed to members outside the Erlangen Huguenot community, but also documents without a direct addressee but intended for external recipients, such as a master craftsman’s diploma. Incoming documents are texts received from outside the Erlangen Huguenot community. They were in some cases directed only to the Huguenot community, but sometimes had a more general audience, such as members of both the French and German reformed church.

Domain: A domain can be defined as a “socio-cultural construct abstracted from topics of communication, relationships between communicators, and locales of communication” (Fishman 1965: 75). Domains are “a combination of factors which are believed to influence choice of code (language, dialect or style) by speakers” (Trudgill 2003: 41). Indeed, the concept “has helped organize and clarify the previously unstructured awareness that language maintenance and language shift proceed quite unevenly across the several sources” (Fishman 1965: 82). For historical data, Böhm (2010: 22) has proven the concept of domain to be a useful heuristic to approach multilingualism in Huguenot communities. Nevertheless, we should be aware that historical domains are classifications by present-day researchers without a full understanding of the socio-cultural embedding of a particular text. This makes it necessary to explain the abstractions derived from the data in detail. As mentioned above, our corpus does not allow for an examination of the language shift in the school domain or in private texts. Thus, for this paper we differentiate between the following four domains: (i) religion, (ii) administration, (iii) law, (iv) commerce.

The high relevance of religion for the Huguenots is reflected by the large number of texts (186) that can be assigned to the religious domain. Firstly, they belong to the official fields of church administration, such as parish registers, consistory proceedings, certificates, finance registers, statements, and ecclesiastical annual reports. In addition, documents of internal communication such as circulars between the pastor and the Anciens and comments on incoming religious documents are part of this domain. There is also evidence for correspondence with other French and German reformed churches and superior ecclesiastical departments. Finally, some parish members’ petition letters to the church for financial aid are also considered as part of the religious domain, as the ‘locales of communication’ are religious.

The administrative domain is the second largest in our corpus with 135 documents. It comprises texts from the government and subordinate departments, such as the privileges and laws of the community’s formation, governmental orders or regulations, and documents from municipal institutions, for example records from the council of justice, account books, an electoral register, and a first-aid guidebook (cf. Section 5.2). Official correspondence is also assigned to this domain, such as communication with municipal authorities (the colony’s directorate, town council or municipal court) and the government, or with officials outside the community. As long as the internal communication concerns solely administrative topics, we have classified it as administrative. For example, confirmations of the receipt of money written by community members are not assigned to the religious domain, although these texts are addressed to the consistory. Some of the collections of copied texts (Kopialbücher) are located both in the religious and administrative domain as the individual texts vary significantly with regard to their addressee and content.

With 40 documents and none after 1748, the legal domain is rather small and diachronically unbalanced in our corpus. Nevertheless, we identified legal texts as separable from other administrative texts that are usually connected to governmental authorities or administrative practices. As a consequence, the legal domain comprises texts written by legal practitioners or people in contact with these professionals. The archives hold extensive protocol books by the notaries Joseph Meynier (1686–1696), Isaac de Caries (5 volumes: 1690–1718), and Jacques Petit (1725–1740) (Petersilka 2019: 228). In addition, there are protocols and documents from court and contracts. Letters written by community members to notaries and their drafts of testaments, stored in the legal files, have also been assigned to this domain.

A domain with the small number of only 30 documents but spanning the entire time period has been labelled commercial domain. It comprises texts written in the context of business or manufacturing and includes guild laws of the stocking makers and their requests to the king, an apprenticeship letter, a master craftsman’s diploma, regulations such as price lists for different kinds of stockings, receipts, letters of complaint and accounting books from several manufacturers and one merchant.

5 Results

5.1 Language shift in the Erlangen Huguenot community

This section presents the results of the quantitative analyses of language shift in the Erlangen Huguenot community. After a general overview (Section 5.1.1), we discuss how the direction of communication (Section 5.1.2), social group of the writers and addressees (Section 5.1.3), and domain (Section 5.1.4) influence the linguistic choices over time.

5.1.1 General overview

For our general overview of the language use in our corpus, we differentiate between French, German, and multilingual texts. We were able to classify 28 texts as multilingual, most of them being official texts from the first half of the 18th century that exist in two versions or with a translation (cf. the examples in Section 5.2.1). Evidence for codeswitching within texts is rare and has only been documented in the so-called Protocollbuch N 5 (cf. Section 5.2.2) and in an official letter in German with forms of address in French (around 1767–86; Nbg 50/840-275). Similarly, there are only a few documents with addressee- and topic-related multilingualism (cf. Section 5.1.4). Loan words or single-word switches have not been counted as multilingualism, as they are also common phenomena in monolingual texts.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of French, German, and multilingual texts in our corpus during the approximately 150 years under examination. The diagram is divided into eight 20-year periods, the first being slightly shorter. Due to the small number of texts from the 1840s/50s (only four, written completely in German), the figure includes only texts until the 1830s. Some documents, such as the consistory proceedings or protocol books, span several years and cross the defined time sections. In such cases, the documents were assigned to more than one time period.[10] As a consequence, the number of 406 texts is higher than the actual 314 archival documents in our corpus.

Proportion of French, German, and multilingual texts over time.

The shift from French to German in our corpus extends over 130 years. This shows that the general notion of a language shift process being completed within three generations does not apply to the Erlangen Huguenot community (cf. Section 2). French texts dominate in the first six periods and gradually decrease by the end of the 18th century, while the use of German prevails from the early 19th century. Each of the time periods examined contains French, German, and multilingual texts. The two languages do not simply replace each other, but Figure 1 indicates the existence of a multilingual period that recedes as texts in German become dominant.

The following analyses focus on the dynamics of the language shift process and different factors influencing it. In the rest of Section 5.1, the comparably small number of multilingual texts will be integrated into one category of ‘documents in/with German’. This facilitates the visualization of the general trends.

5.1.2 Direction of communication

Figure 2 shows the influence of differing directions of communication on language use. The shapes of the graphs for incoming communication (134 texts) and internal communication (169 texts) are similar, with the use of German continually increasing over time. Compared to these developments, the graph for outgoing communication (103 texts) behaves unexpectedly, with a quick rise of German in the first half of the 18th century, a drastic decline in the second half and a rise again in the early 1800s. Here, we need to take into account the additional factors of the social group of the individual writers and addressees as well as individual practices, which will be addressed in Section 5.1.3.

Proportion of texts in/with German in differing directions of communication over time.

While the earliest documents in our corpus, decrees and letters by the government directed to the Huguenots, are in French, incoming communication with a wider audience either has a translation into French (two documents from around 1697 and 1699 [Nbg 50/840-198] directed to both French and German reformed immigrants to Erlangen, classified as multilingual in Figure 1) or are completely in German. The first German text directed to the Huguenots is a letter from February 1700 by the margrave to the Huguenot pastors allowing them to use his estate for church services (Nbg 50/840-198).[11] The fact that only a few years after the Huguenot’s arrival in Erlangen incoming documents are exclusively written in German suggests at least a passive German competence among the Huguenots. The proportion of texts in/with German then increases steadily. Incoming texts by French writers, however, remain in French until the end of the 18th century.

Internal communication of the Huguenot community shows a rather low proportion of German with a late and rapid replacement of French in the 1820s. Throughout the community, French language competence decreases during the 18th century (cf. Section 2.1). Particularly in the second half of this century, individual differences between the writers become obvious, which is assessed by comparing texts with a similar function. For example, in 1774 the Huguenot descendant Jean Thomas asks the consistory for money in German (Nbg 50/840-346). More than 30 years later, in 1806, the clockmaker S. D. Espagne also pleads for financial support but uses French (Nbg 50/840-276).[12] Such a late use of French by a manufacturer is impressive and gives proof of the high status of French for some individuals in the community. The replies of the consistory are in French, which assumes a passive competence of French inside the community. Switches to German among the church members are also connected to individuals. While Carl de la Rue’s request for retirement from a post among the Anciens is in German (1808), Jean Joseph Caldesaigues uses French for such a request (1810) (Nbg 50/840-220, 276).

The earliest internal document of the consistory in German is the direct consequence of Pastor Hollard’s weakening eyes. As he was no longer able to write, he employed a German scribe who conducted Hollard’s correspondence in German. A German receipt for goods received from a monastery (1796) with a remark on Hollard’s condition gives proof of this (Nbg 50/840-276). Similarly, the change to German in the consistory’s protocols is connected with the inauguration in 1827 of Pastor Isaac Rust (Nbg KB 9.5.0001-234), the community’s first German pastor. These individual language shifts led to a continual increase of German in internal communication. Huguenot texts addressed to other German or mixed addressees, however, show a more complex development and are discussed in the following.

5.1.3 Social group of the writers and addressees

Figure 3 considers the social group of the writers and addressees. In particular, we compare two developments: incoming communication from Germans (109 texts) and communication by Huguenots to Germans or mixed addressees (81 texts). In comparison to Figure 2, the latter category is no longer restricted to outgoing communication, but also includes some internal communication texts. In addition, it seemed reasonable to combine Huguenot texts to Germans (54 texts) and mixed addressees (25 texts) into one category, as we are interested in the question of whether the Huguenots use German when German addressees are involved, and the amount of data for each category would not be enough for a separate consideration. A third graph is added as means of comparison: communication by the Huguenots to Huguenot addressees, including internal communication directed to Huguenot addressees (91 texts). It shows a consistent use of French with a late shift to German in the early 19th century.

Proportion of texts in/with German in different constellations of authors, recipients and directions of communication over time.

As we observed in the previous section, incoming communication from Germans shows a high proportion of documents in German already by the late 17th and early 18th centuries, while incoming texts from Huguenot writers shift to German only in the early 19th century. Figure 3 visualizes the diachronic development for incoming communication only from Germans.

The linguistic developments of the Huguenots’ texts to German or mixed addressees are rather complex. In general, the proportion of documents in/with German is higher in any time period than in texts to Huguenot addressees, which results from addressee-related language choices. The graph for texts to German or mixed addressees is similar to the graph for outgoing communication in Figure 2, as a considerable amount of data is shared by both graphs. The zigzag shape of the graph itself, however, can only be explained in a qualitative examination of the documents and writers behind them.

From the first two time periods, we have only two Huguenot texts to German or mixed addressees, which leads to 0% of German in 1685–99 (French letter from reformed Church to government 1697; Nbg 50/840-204) and 100% in 1700–19 (German protocol of contract negotiation by notary Jean Rauzet 1718; Nbg 50/840-276). The numbers for the other periods are based on 77 texts and therefore more reliable. The high proportion of German documents (69%) in the third period (1720–39) is predominantly connected to six legal texts, written by the notaries Jean Rauzet and Jacques Petit, who chose the language depending on the addressee: French to Huguenot addressees and German to Germans. Strikingly, Jean Rauzet preferred German when he addressed both Huguenot and German addressees, for example in a contract (1723) between Andreas Peters and Claude Germain (Nbg 50/840-276). In addition, multilingual texts from the manufacturing domain led to a high proportion of German in this period. The decline to less than 10% of German in texts to German or mixed addressees between 1760 and 1799 results from a phenomenon that can be labelled receptive multilingualism, i.e., a “language constellation in which interlocutors use their respective mother tongue while speaking to each other” (Zeevaert and ten Thije 2007: 1).[13] Here, the consistory received texts in German but answered them in French (cf. Section 5.2.3). This practice is replaced by addressee-related language use in the early 19th century, before the general shift to German is completed in the 1820s.

5.1.4 Domain

The final factor to be analysed that influences language use is domain. As a diverse number of documents has been assigned to each domain, ranging from 30 texts in the commercial and 40 in the legal domains, and up to 135 in the administrative and 186 in the religious domains, our previous 20-year periods would lead to distorted graphs in the domains with fewer texts. Thus, in the following we differentiate only four time periods comprising approximately 40 years each. Figure 4 shows a clear separation of the four domains at each of the time periods with an increasing use of German in each domain.

Proportion of texts in/with German per domain over time.

The highest proportion of documents in or with German is found in the domain of commerce. Already by the first half of the 18th century, more than half of the documents contain German. Several of these texts are multilingual, such as three guild laws of the stocking makers (1709, 1714, 1725), a master craftsman’s diploma (1727) and an apprenticeship letter (1733; cf. Section 5.2.1). The contacts between French and German speakers in trade and manufacturing collaboration in particular led to multilingualism. For example, this apprenticeship letter for stocking makers was issued by the French master Frederic François for his German apprentice Georg Winckler (Erl 35 Nr.III.5). In contrast, personal documents by Huguenot merchants such as Abraham Marchant’s accounting book (1718–1762; Erl 33.1.M.1) also remain in French in the later time periods (Yardeni 1986: 157).

The domain of administration shows a comparably high number of 30–40% documents in or with German in the first three periods. This mainly results from incoming official communication in German and multilingual texts directed at a diverse audience, such as decrees by the margrave.

From the domain of law, only texts until 1748 are transmitted in our corpus. Some of the legal documents provide proof of the close contacts between the German and French population in Erlangen (Yardeni 1986: 156). Notaries switched between French and German depending on the clients they addressed (cf. Section 5.1.3).

The domain of religion shows the lowest proportion and the latest shift to German. This can be explained with the importance of religion for the Huguenots’ identity which was connected to the use of French (cf. Section 5.2.3). Besides few incoming texts in German, we can already observe German elements in texts of a conceptually oral character in the 1730s. These are a bilingual list of costs owed to the French reformed Church from the 1730s (Nbg 50/840-203)[14] and the bilingual Protocollbuch N 5 from 1731–44 (cf. Section 3). The slight decrease of German in the third period (1760–1799) results from the practice of receptive multilingualism with an increase of texts in French. The shift to German occurs in the first three decades of the 19th century. In the 1800s, outgoing communication begins to appear in German (Nbg 50/840-199) and members of the French reformed Church start addressing the consistory in German. The pastors themselves begin using the two languages in an addressee-related manner. For example, Pastor Poiret writes to a community member in French (1808; Nbg 50/840-220) and to city officials in German (1811; Nbg 50/840-417). His multilingualism appears even within individual texts. In a French letter to the Anciens (1806), Poiret announces a journey to Bamberg and a possible delayed return for the church service the day after. In a margin next to the letter’s seal, he adds a short German comment about his horse (Nbg 50/840-276). The choice of the two languages here is topic-related with religious matters in French and mundane issues in German. Official religious texts in German start appearing in 1820, when Pastor Ebrard writes some of his circulars to the members of the French reformed Church in German (Nbg 50/840-205). The loss of passive competence in French, particularly among the younger members of the community, led to considerations inside the consistory to switch to German church services, as their French would no longer suffice for what was stated in 1820 as a “nützliche Besuchung” (‘useful attendance’; Nbg 50/840-205, fol. 20r). This was realised in 1822 (cf. Section 2). The latest documents to shift to German are church and protocol books in 1827 (Nbg KB 9.5.0001-234).[15]

5.2 The changing status of French and German in the community

5.2.1 French as the dominant language in the early community

French was the dominant language in the early Erlangen Huguenot community. As a result, official documents were required to be published both in French and German to be understood in the whole town, which led to a high number of bilingual texts in the 17th and first half of the 18th century (cf. Figure 1), before the Huguenots had become bilingual. In the following, we present examples of such texts from the early community and discuss the changing status of the two languages.

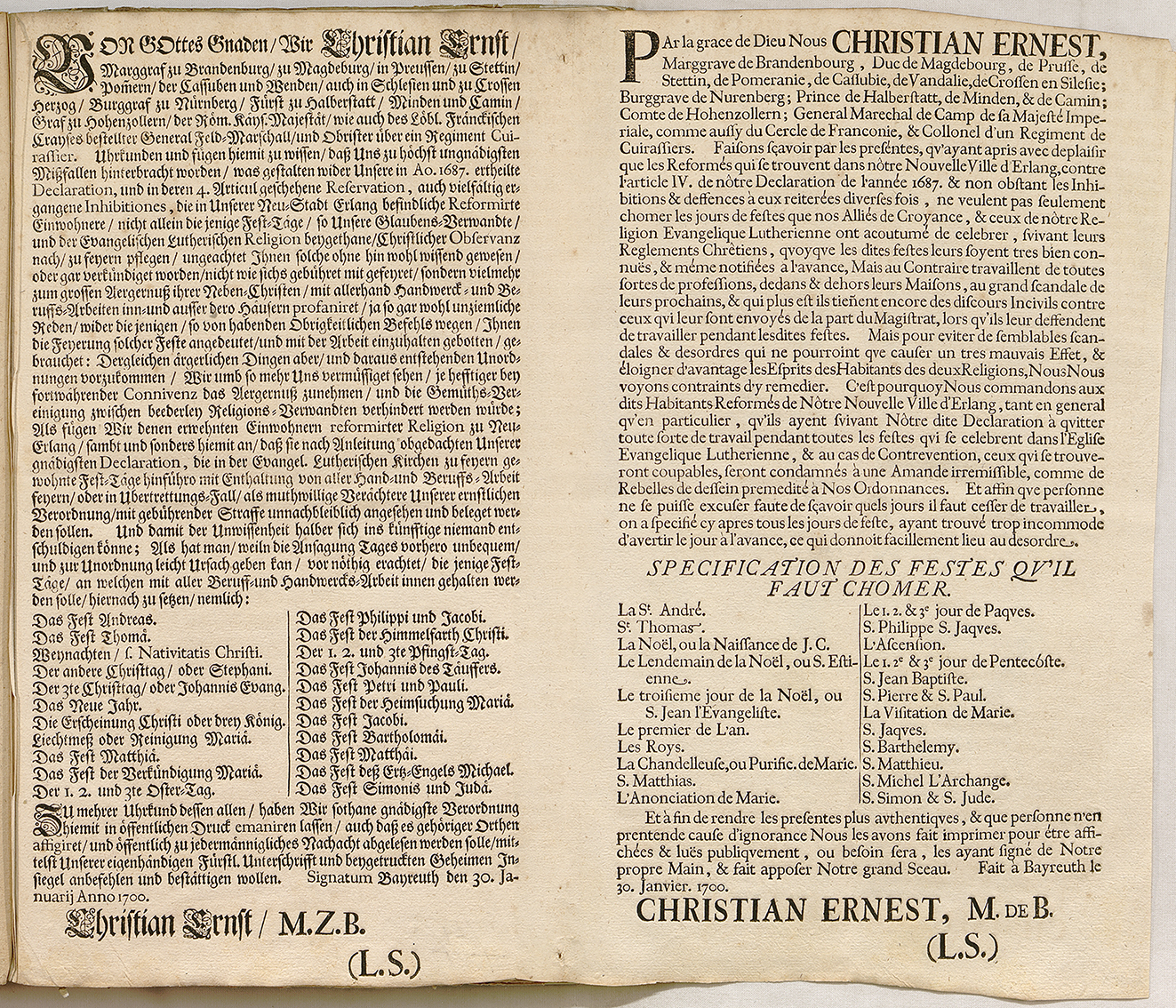

Bilingual documents addressed to both the French and German reformed communities are often published in two columns with one language on each side. This, for example, applies to a police order (Policey-Ordnung/Reglements de Police; Bam vol. 14, fol. 115–120) from 1705 with German in the left column and French in the right, or a regulation on public holidays from 1700 (cf. Figure 5; Bam vol. 14, fol. 112r).[16] The latter originates from disputes between the Huguenots and the Germans (Ebrard 1885: 25), in particular, from complaints about Huguenots working on German holidays and using indecent words against the Germans who had reminded them of the rules. The text of the regulation, issued by margrave Christian Ernst, is in landscape format and like the police order has two columns: German on the left, French on the right. It first refers the margrave’s decree from 1687 and mentions the recent incidences (“ärgerlichen Dingen […] und daraus entstehenden Unordnungen”/“scandales & desordres”). It then provides a list of the annual holidays in two subcolumns and closes with the instruction to display the text in public places. Apart from the conventional use of different scripts for the two languages – blackletter for German, Latin script for French and borrowed words from Latin (Schiegg and Sowada 2019) – the two versions of the document show a further difference in their layout. Above the list of the holidays, the French version has a prominent headline that appears centred and in enlarged uppercase letters: “SPECIFICATION DES FESTES QV’IL FAUT CHOMER” (‘specification of holidays on which work pauses’). In the German version, this information is integrated into the text block before the list. While the contents of this passage are identical, its layout shows variation. As the Huguenots are the addressees of the French text, the layout of this version directs them to the lower part of the text that is particularly relevant for them: the list of days on which their work should pause.

Regulation on public holidays in Erlangen (30 January 1700) (Bam vol. 14, fol. 112r).

In some cases, bilingual texts are transmitted in different versions that allow for diachronic comparisons and connections with changes in the community. Bischoff (1981) mentions three bilingual guild laws of the stocking makers (1709, 1714, 1725) and two apprenticeship letters from that guild (1732,[17] 1733). Three more apprenticeship letters (1734, 1768, 1773) were discovered recently.[18] In our examinations of these texts, we observed differences between the individual textual versions both in their layout and wording that are indicative of changes within this trade.

The earliest of the guild laws (all in Erl 2.A.225, R.C.1.b.1/1) is from 1709. It provides a French version of the text on the first 13 folios and then switches to a German version. In contrast, the two texts from 1714 to 1725 have the two versions on opposite pages, with German on the left and French on the right. These changes in layout indicate two developments: with the German version on the left side, French loses its status as the primary language. This reflects the developments within the community. While the profession of the stocking makers was completely controlled by the Huguenots in the 17th century, by 1714 an increasing number of Germans had gained the civil rights to be stocking makers (Bischoff 1981: 125). The new layout with alternating languages from page to page indicates a context of multilingualism prevailing within the guild. This observation is supported by a change in the wording of the guild laws. While according to the version from 1709 an apprenticeship letter was issued either in German or in French (Bischoff 1981: 126), in the version from 1714 “oder” (‘or’) is crossed out and corrected to “und” (‘and’) by another writer: “worauff Ihme ein Lehrbrieff in gehöriger Form in teutsch oder und frantzößl. Sprach ertheilet” (‘whereupon an apprenticeship letter in an orderly form, in the German or and French language is issued’; cf. Figure 6; Schanz 1884, vol. 2: 239). This change remains in the version from 1725. The French version of the text from 1709 is identical to the German one (“en alemand ou en françois”; fol. 12r). Similarly, the French versions from 1714 to 1725 adopt the change to and, and in addition shift French to the first position (both: “en françois et allemand”; fol. 61r and 118r). This reflects the equal status of the two languages in a multilingual setting, whereby German is mentioned first in the German version and French in the French one. Further micro-analyses of these texts would be promising but cannot be undertaken here.

Excerpt from the guild law of the stocking makers (10 January 1714, Article 25) (Erl 2.A.225, fol. 60v).

The apprenticeship letters for the stocking makers themselves are printed formulae with empty spaces for names, dates, and the assessment of the apprentice. A handful of exemplars have survived in the archives. Apart from minor changes in the wording, the layout of the letter also changed between 1732 and 1733. While the left column of the earlier text is in French and the right in German, the arrangement switches in the later version.[19] Envelopes are transmitted together with the texts from 1733 to 1734, each carrying some information about the text type, the apprentice, and the date. These handwritten paratexts appear only in German. The increased relevance of German is connected to the growing number of the Germans in the guild of the stocking makers (Bischoff 1981: 126) and in the town district Christian-Erlang in general. At the same time, it is striking that bilingual versions of the apprenticeship letters remained in use even in the 1770s.

Diachronic changes in the layout of different textual versions also appear in the margrave’s declarations with the privileges for the French and German reformed communities that were confirmed and updated every few years. Although we were able to examine only a few versions for this article, the general diachronic trends in their layout seem comparable to the other text types. In the earlier years, the different language versions were published on separate sheets of paper or booklets. Such is the case for the decrees from 1686, 1698, and 1702 (Bam vol. 14, fol. 68ff.). Similar to the guild laws that also appeared first in two separated versions, the decrees shift to the two-column layout later, for which we have evidence from 1711,[20] 1727, and 1740 (Nbg 50/840-198), all of which have the German version in the left column.

One of the later texts that were found in such a two-column layout is a decree from 1753 on the establishment of a city depot and the taxation of goods (“Niederlags- und Waag-Ordnung”; Nbg 50/840-198). Again, the German version is in the left column. The primacy of German is also indicated by a short printed paratext on page 2, with the addressee of the text appearing only in German: “An die Amtshauptmannschafft Erlang.” ‘To the district of Erlangen’.

5.2.2 The use of German in conceptually oral texts

The small number of conceptually oral texts from the Huguenot community makes it nearly impossible to trace the language shift in spoken language. The rare transmission of private and informal documents allows only few insights from this perspective.

One private document is a recipe book from 1773 by Susanne Roucouly (Erl 26.Hs.106), daughter of Jean Puy, who had migrated to Erlangen at around 1700.[21] The handwritten book is completely in German, with some regional variants, and has the title: Dießes Koch Buch gehöret Mein Susanne Roucouly in Erlang den 1ten January 1773 ‘This cookbook is mine. Susanne Roucouly in Erlangen, 1st January 1773’. Similar to other historical cookbooks (Pickl 2009: 22), Roucouly’s book is a compilation of copied recipes.[22] It is disordered, shows repetitions and some loose sheets. Nevertheless, it is proof of the German competence of a second-generation immigrant and their use of German in private contexts. Another private document is a book with excerpts by Julie Meynier (1800–1859; cf. Section 5.2.4), starting in 1816 (Erl 25.B.2132). Apart from a single quote by Voltaire in French (p. 16), the book is completely in German and consists of poetry, quotations and copied letters by several members of her family. Further letters from the Meynier family, for example by her mother Wilhelmine to Julie from 1835 (Erl 25.B.2147), are also in German.

Other sources to approach historical orality are drafts and protocols (Macha 2010: 137). Some notes and drafts for contracts with addressee-related language choices, written by notaries between 1715 and 1740, were identified in the archival material. A rather complex case is a collection of protocols from the meetings of the consistorial between 1731 and 1744, collated in the so-called Protocollbuch N 5 (Nbg 50/840-205). It contains evidence for multilingualism, for example in the form of code switching into German in reported speech, which hints at the fact that even ecclesiastical negotiations were held in German by the 1730s. However, the text itself is an 11-page excerpt from the early 19th century, which is proven by palaeographic characteristics and its integration into a file from 1828/30. The copyist had, on the one hand, clear influence on the text with his extensive cuts, but, on the other hand, has kept the draft character of the original with several corrections and abbreviations resulting from the time pressures of the original protocolling situation (Topalović 2003: 130). What is striking about this document is its provenance from a religious context, where texts in French dominated throughout the 18th century. Thus, the Protocollbuch may hint at the fact that in spoken language, German had already been in use in the religious domain much earlier.

5.2.3 Retention of French in schoolbooks and by the consistory

While French disappears from texts in the commercial domain in the second half of the 18th century, it remains present in other contexts. The school domain provides some evidence for this, despite the few sources from this context in our corpus (cf. Section 3).

Lists and reports from the French school’s later years (1810, 1813/14), when the number of pupils was decreasing before the school’s closure in 1817, provide evidence for the prevailing multilingualism: some of the schoolbooks used were in German, but others, particularly for religious education but also some elementary books, were still in French (Nbg 50/840-415, 488; Barth 1945: 38). The school reports by the Pastors Poiret (1810) and François Elie Ebrard (1813/14), however, are completely in German. Four texts connected to school contexts from 1752 were still in French: school regulations, all written by Pastor Hollard (Nbg 50/840-415).

Apart from the French school, the consistory can be considered a stronghold for French writing in the later years of the community. Its members fostered the use of French as an essential part of the Huguenots’ group identity, which was a prerequisite for defending their privileges. It is rather astonishing that this was successful until 1810, when the French reformed community had become a small minority in Erlangen’s population (cf. Section 2.1). In the following, we present two examples of the retention of French: the practice of receptive multilingualism by the Huguenot pastors, and a list of signatures from the community members.

In Erlangen, the consistory applied the practice of receptive multilingualism both in communication with members of the Huguenot community and external addressees. Evidence for the first case has been presented in Section 5.1.2. For instance, the syndicus Carl de la Rue used German to write his request for retirement from a post among the Anciens (24 March 1808) and received a reply (“Décharge”; ‘discharge’) by Pastor Poiret in French (16 May 1808) (Nbg 50/840-220). An early example for receptive multilingualism with an external addressee is Pastor Le Maître’s letter from 17 December 1746 to the margravine of Brandenburg-Kulmbach asking for continuing the payment of the pension for the deceased Pastor Malvieu, as the community had financial problems (Nbg 50/840-199). This was accepted in a German letter three weeks later (Nbg 50/840-198).

Several texts in our corpus are by Pastor Aimé Louis Hollard, who held his office for nearly five decades until his death in 1800 (Bischoff 1982: 86). Apart from his latest delegated letter in German from 1796 (cf. Section 5.1.2), all of his texts are in French, with a large amount of receptive multilingualism. For example, in 1763 and 1769, he asked the margrave to confirm the privileges in French and received the approvals in German (Nbg 50/840-199). Figure 7 illustrates such an exchange between Hollard and the margrave (Nbg 50/840-199). In a French letter from June 1779, he requests the government to fill a vacancy in the law council with a French councillor. More than two years later, in October 1781, he receives the German reply that the procedure is still being discussed. In January 1782 a second reply follows: the consistory should make three or four suggestions, including the son of the French court secretary Assimont. Some weeks later, Assimont’s son is accepted in a French letter written by Hollard and signed by the consistory (Barth 1945: 55).

Example of receptive multilingualism between Pastor Hollard and the margrave.

Excerpt from the list of signatures by the French reformed community attesting the reading and forwarding of first aid behaviour guidelines (October 1798) (Nbg 50/840-187).

As a whole, receptive multilingualism was a practice that allowed the French reformed community to express their group identity, which was at the same time a prerequisite for defending their privileges (Böhm 2010: 72). The pastors after Hollard, however, were less consistent in using receptive multilingualism and replaced this practice by addressee-related language choices and a final shift to German.

An impressive example of the prevailing maintenance of French by the end of the 18th century is a decree by the Prussian government (1798) containing first aid behaviour guidelines (Nbg 50/840-187).[23] It is written in German but embedded in a booklet with a handwritten French instruction by the Huguenot Pastor Robin. He emphasizes the importance of the decree and instructs the members of the community to read it and pass it on afterwards. A list of 49 entries in the form of short French phrases or sentences follows, each with the date and name of the person to whom it had been handed over between 5 October to 5 November 1798. For example, Mr Mengin had given it to Madame Seidel on 24 October at 9 in the morning (cf. Figure 8, line 1: “à Madame Seidel le 24 8bre a neuf heure du matin”). She then handed it over to Madame Schreiber at 2 in the afternoon. The handwriting and spelling show different degrees of routined writing, and often the writers copied parts of the phrases from above their own but added an individual date. The more routined writers with a higher proficiency in French included some variation. For example, Mr Roquette added his own name at the beginning of his entry (line 5), which made Mr Fraisse (line 6) forget to add his addressee’s name, who in return added his name “Randon” at the end of his entry (line 7). Mr Boniot, who had a small and routined handwriting (line 9), finally broke with this confusing structure, added a clarifying “Remis à” (‘Handed over to’) at the beginning of his line and his own name at the end, separated from the rest with a full stop. As a whole, this document is a late testimony for multilingualism in the Erlangen Huguenot community. Pastor Robin had expected everybody to understand both the German guidelines and his French instructions, which means that he presupposed a passive competence in both languages. The signatures provide proof of a certain active competence in French, at least among some of the community members. This document underlines the retention of French by the end of the 18th century, when the overall use and competence of French in the community had declined significantly. With this list, the Huguenots confirmed their connection with the consistory and their group identity.

5.2.4 French as a social symbol

Despite the decline of French in the Erlangen Huguenot community by the end of the 18th century, the language was preserved among a small intellectual elite. As French had disappeared from the religious domain, French lost its connection to the Huguenots’ religious identity, gained the status as a prestige language in the context of the European Francophonie in the 19th century, and was used for social distinction (Petersilka 2019: 224). At the same time, it was still connected to their identity as Huguenot descendants.

The Meynier family provides insights into the linguistic developments among intellectuals in the Erlangen Huguenot community. Jean-Jacques Meynier (1710–1783), whose grandparents had emigrated from France around 1700, was born in Offenbach and arrived in Erlangen around 1735. He still considered himself a Frenchman, which he explicitly states in the preface of his book on contrastive linguistics (Meynier 1763; Petersilka 2019: 230). He was cantor of the French reformed community in Erlangen and university lecturer of French. In his publications, we find further metalinguistic remarks on the use of French. In his French grammar, he repeats his French identity in the preface (“je suis Français” – ‘I am French’; Meynier 1767; Petersilka 2018a: 152) and complains about the decay of French among “unsere Teutsch-Franzosen” ‘our German-French [people]’, i.e., the Huguenot descendants living in Germany (e.g., Meynier 1767: 310; Petersilka 2018a: 158). In contrast, his son Jean Henri Meynier (1764–1825), also an author, teacher, and university lecturer of French, is characterized as a model for the cultural life and the Germanization of the French community in Erlangen (Bischoff 1982: 78). In an educational treatise, published under a German pseudonym, he explains basics in grammar and uses the following example sentence for verbal inflection: “ich bin ein Deutscher, du bist ein Deutscher, er ist ein Deutscher” ‘I am a German, you are a German, he is a German’ (Petersilka 2019: 243). He germanized his name to Johann Heinrich, and his patriotic attitude was fostered by the anti-French views in the context of the Napoleonic Wars (Petersilka 2019: 242). Nevertheless, Johann Heinrich at the same time recognized the relevance of French as the lingua franca in Europe and rejected the “kindischen Haß” ‘childish hatred’ (Petersilka 2019: 243) against it. In 1797, he even criticized the orthographic errors in the French of the Anciens in an impolite manner, who in return excused their lack of opportunities to write in this foreign language (Nbg 50/840-199).

The Meynier family continued the bilingual education of their children in the 19th century so that even fifth- and sixth-generation immigrants still spoke French. Johann Heinrich’s sons, Charles and Louis (fifth generation), migrated to Geneva and Paris, which is an indirect sign of their competence in French (Petersilka 2019: 250). Johann Heinrich’s daughters, Charlotte and Julie, stayed in Germany. Julie’s private book of excerpts and her family’s letters (cf. Section 5.2.2) are in German, which is proof that the members of Erlangen’s highest social class had also shifted to German in their written everyday language use in the early 19th century. But she considered French as important enough to employ a governess, her aunt Luise, to teach her daughter, Florestine, French (1825–1905; sixth generation; Petersilka 2019: 246). In her diary from 1834, Julie mentions a pause in Florestine’s French tuition so that she herself supervised her daughter’s translations between French and German (Eschmann 1989: 23). This documents Julie’s own competence and interest in French.

A final example of late use of French by an intellectual are the texts by August Ebrard (1818–1888), son of the last pastor using French during church services, François Ebrard. In 1834, just as he began studying the history of his Huguenot ancestors, he switched to French in his diary and in letters to his mother, despite her being of German origin (Ebrard 1888: 70, 220). In contrast, his diary from a trip to Frankfurt/Main in 1835 is in German (Erl, 25.B.3017). His use of French thus had stylistic motivations and was probably connected to nostalgia (Ebrard 1885: VII).

6 Conclusion

This corpus-based study has traced the language shift and changing status of French and German in the Erlangen Huguenot community from its beginning in 1686 until the 19th century. The language shift described can be characterized as a comparably long, multi-dimensional and dynamic process. The different factors do not influence language choices as absolute categories but rather as probabilities. For example, our observations of the different domains show that domain-based usage does not follow a static diglossic situation with a complementary distribution of the two languages in individual domains, as has been suggested by some research (Rindler Schjerve 1996: 796). Rather, there is a high degree of variation within the domains and changing frequencies of language use over time. The duration of the language shift exceeds the schematic conceptions of a three-generational change in earlier research (cf. Section 2). After a flourishing of French in Erlangen in the early 18th century, the use of French saw a sharp decline, particularly during Napoleonic times. Thus, the time period before German dominates in the texts of our corpus comprises over a century with its final shift in the religious domain after around 140 years of the first Huguenots arriving in Erlangen.

Reasons for the long maintenance of French are its close connections with the Huguenots’ French reformed religion and their identity. As the Huguenots’ privileges were connected to their group identity, the language was defended by the pastors of the consistory practising receptive multilingualism and supporting the use of French in the community. As a consequence, a number of Huguenot descendants, such as the clockmaker Espagne, continued writing in French even in the early 19th century. His use of French in a plea for financial support, despite obvious difficulties, can be interpreted as a strategic linguistic choice to increase his chances. The transmitted material from writers like him is a treasure trove for further research on language loss and acquisition in general and the Style Réfugié in particular. Besides religious and practical aspects, French was also a social symbol for the Huguenots, which, however, went beyond a mere prestige symbol connected to French as a lingua franca (cf. Böhm 2010: 518). Some Huguenot descendants considered French as still part of their identity because it provided them with a link to their families’ past. This particularly applies to intellectuals such as the Meynier and Ebrard families, while the major part of the community had given up their ancestors’ language and had been acculturated into German society.

Funding source: Université de Genève

Appendix: Archival sources

Nbg = Nürnberg, Landeskirchliches Archiv der Evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirchen in Bayern: LAELKB, Pfarrarchiv Erlangen-Reformierte Gemeinde Findbuch 50/840-187 bis 192, 198, 199, 203 bis 205, 220, 222, 225 bis 235, 262, 275, 276, 289, 346, 347, 415 bis 417; KB 9.5.0001-234-1 bis 8.

Erl = Erlangen, Stadtarchiv: StadtAE 2.A.225/R.C.1.b.1/1, 2.R.84, 6.B.120, 25.B.--, 25.B.--(U1776X24), 25.B.--(U1782X30), 25.B.2019, 25.B.2086, 25.B.2131, 25.B.2132, 25.B.2133, 25.B.2136–2145, 25.B.2146, 25.B.2147, 25.B.2148–2154, 33.1.M.1(1), 33.1.M.1(2), 33.1.M.1+2, 33.1.P.1+2, 35. Nr.III.5., III.6, III.18, III.48, III.49, I.3.H.1, III.7.M.1, III.6.P.1, III.136.R.1, R.67.F.4/1, R.67.F.4/4, R.67.F.4/5(I.H.7).

Bam = Bamberg, Staatsarchiv, Markgraftum Brandenburg-Bayreuth, Geheimes Archiv Bayreuth, Nr. 5568–5590, Fasciculi Erlanger Actorum, Bände 1–15.

References

Argent, Gesine, Vladislav Rjéoutski & Derek Offord. 2014. European Francophonie and a framework for its study. In Vladislav Rjéoutski, Gesine Argent & Derek Offord (eds.), European Francophonie. The social, political and cultural history of an international prestige language, 1–31. Oxford: Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Barth, Lydia. 1945. Die Eindeutschung der Erlanger Hugenotten. Erlangen: Unpublished PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Bischoff, Johannes E. 1981. Der Textwechsel im Lehrbrief der Erlanger Strumpfwirker 1732/1733. Ein Beitrag zur Frage der Eindeutschung der Hugenotten. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Heimatforschung 28. 125–128.Suche in Google Scholar

Bischoff, Johannes E. 1982. Erlangen 1790 bis 1818. Studien zu einer Zeit steten Wandels und zum Ende der ‘Französischen Kolonie’. In Jürgen Sandweg (ed.), Erlangen. Von der Strumpfer- zur Siemens-Stadt: Beiträge zur Geschichte Erlangens vom 18. zum 20. Jahrhundert, 59–126. Erlangen: Palm.Suche in Google Scholar

Bischoff, Johannes E. 1986. Die Aufnahme der Hugenotten in Franken und die Entwicklung ihrer französisch-reformierten Kirchengemeinden. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Heimatforschung 34. 195–223.Suche in Google Scholar

Böhm, Manuela. 2010. Sprachenwechsel. Akkulturation und Mehrsprachigkeit der Brandenburger Hugenotten vom 17. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110219968Suche in Google Scholar

Böhm, Manuela. 2016. Sociolinguistics of the Huguenot communities in German-speaking territories. In Raymond A. Mentzer & Bertrand Van Ruymbeke (eds.), A companion to the Huguenots, 291–322. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004310377_013Suche in Google Scholar

Deuerlein, Ernst G. 1926. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Erlanger Hugenottenfamilie (du) Puy und des Hauses Goethestr. 32 (früher Spitalstr. 27, Hs.-Nr. 140). Erlanger Heimatblätter 37–42. 150–171.Suche in Google Scholar

Ebrard, August. 1885. Christian Ernst von Brandenburg-Baireuth. Die Aufnahme reformirter Flüchtlingsgemeinden in ein lutherisches Land 1686–1712. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.Suche in Google Scholar

Ebrard, August. 1888. Lebensführungen. In jungen Jahren. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.Suche in Google Scholar

Ehlich, Konrad. 1996. Migration. In Hans Goebl, Peter H. Nelde, Zdeněk Starý & Wolfgang Wölck (eds.), Kontaktlinguistik – Contact linguistics – Linguistique de contact. Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung – An international handbook of contemporary research – Manuel international des recherches contemporaines, vol. 1, 180–193. Berlin: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Eschmann, Jürgen. 1989. Die Sprache der Hugenotten. In Jürgen Eschmann (ed.), Hugenottenkultur in Deutschland, 9–35. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.Suche in Google Scholar

Firnstein, Angelika. 1981. Gallizismen in der Stadtmundart von Erlangen. Erlangen: Unpublished State Examination thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Fishman, Joshua A. 1965. Who speaks what language to whom and when? La Linguistique 1(2). 67–88.Suche in Google Scholar

Fishman, Joshua A. 1966. Language maintenance and language shift: The American immigrant case within a general theoretical perspective. Sociologus 16(1). 19–39.Suche in Google Scholar

Friederich, Christoph (ed.). 1986. 300 Jahre Hugenottenstadt Erlangen. Vom Nutzen der Toleranz. Ausstellung im Stadtmuseum Erlangen 1. Juni bis 23. November 1986. Nürnberg: Tümmel.Suche in Google Scholar

Füssel, Johann M. 1788. Unser Tagebuch oder Erfahrungen und Bemerkungen eines Hofmeisters und seiner Zöglinge auf einer Reise durch einen grossen Theil des Fränkischen Kreises, nach Carlsbad und durch Bayern und Passau. Zweyter Theil. Erlangen: Palm.Suche in Google Scholar

Glück, Helmut. 2002. Deutsch als Fremdsprache in Europa vom Mittelalter bis zur Barockzeit. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110881158Suche in Google Scholar

Göhring, Ludwig. 1925. Von der Erlanger Handschuhmacherei. Ein Stück hängengebliebenes Französisch. In Ernst Deuerlein, Eduard Rühl & H. Junge (eds.), Erlanger Heimatbuch, vol. 3, 84–93. Erlangen: Junge & Sohn.Suche in Google Scholar

Grießhammer, Birke. 1986. Handschuhmacher und Weißgerber – eine französische Enklave. In Christoph Friederich (ed.), 300 Jahre Hugenottenstadt Erlangen. Vom Nutzen der Toleranz. Ausstellung im Stadtmuseum Erlangen 1. Juni bis 23. November 1986, 168–191. Nürnberg: Tümmel.Suche in Google Scholar

Hartweg, Frédéric. 2005. Der Sprachwechsel im Berliner Refuge. In Sabine Beneke & Hans Ottomeyer (eds.), Zuwanderungsland Deutschland. Die Hugenotten, 121–126. Wolfratshausen: Minerva.Suche in Google Scholar

Hintermeier, Karl. 1986. Selbstverwaltungsaufgaben und Rechtsstellung der Franzosen im Rahmen der Erlanger Hugenotten-Kolonisation von 1686 bis 1708. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Heimatforschung 34. 37–162.Suche in Google Scholar

Jakob, Andreas. 2016. Hugenotten in Franken. Mehr als eine Initialzündung? In Bezirk Mittelfranken, Andrea M. Kluxen, Julia Krieger & Andrea May (eds.), Fremde in Franken. Migration und Kulturtransfer, 157–212. Würzburg: Ergon.Suche in Google Scholar

Koch, Peter. 1990. Von Frater Semeno zum Bojaren Neacşu. Listen als Domäne früh verschrifteter Volkssprache in der Romania. In Wolfgang Raible (ed.), Erscheinungsformen kultureller Prozesse. Jahrbuch 1988 des Sonderforschungsbereichs ‘Übergänge und Spannungsfelder zwischen Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit’, 121–165. Tübingen: Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

Koch, Peter & Wulf Oesterreicher. 1985. Sprache der Nähe – Sprache der Distanz. Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte. Romanistisches Jahrbuch 36. 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110244922.15.Suche in Google Scholar

Krogull, Andreas. 2021. Rethinking historical multilingualism and language contact ‘from below’. Evidence from the Dutch-German borderlands in the long nineteenth century. Dutch Crossing 45(2). 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2021.1943620.Suche in Google Scholar

Lausberg, Michael. 2007. Hugenotten in Deutschland. Die Einwanderung von französischen Glaubensflüchtlingen. Marburg: Tectum.Suche in Google Scholar

Maas, Herbert. 1991. Warum die Kartoffel im Raum von Nürnberg und Erlangen Potacke heißt. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Heimatforschung 39. 227–247.Suche in Google Scholar

Macha, Jürgen. 2010. Grade und Formen der Distanzsprachlichkeit in Hexereiverhörprotokollen des frühen 17. Jahrhunderts. In Vilmos Ágel & Mathilde Hennig (eds.), Nähe und Distanz im Kontext variationslinguistischer Forschung, 135–153. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110220872.135Suche in Google Scholar

Meynier, Jean J. 1763. Allgemeine Sprachkunst, das ist Einleitung in alle Sprachen. Erlangen: Müller.Suche in Google Scholar

Meynier, Jean J. 1767. La grammaire française, reduite à ses vrais principes, ouvrage raisonné. Erlangen, Nürnberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Myers-Scotton, Carol. 1992. Codeswitching as a mechanism of deep borrowing, language shift, and language death. In Matthias Brenzinger (ed.), Language death. Factual and theoretical explorations with special reference to East Africa, 31–58. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110870602.31Suche in Google Scholar

Petersilka, Corina. 2018a. Die Grammaire Française von Jean Jacques Meynier aus Erlangen. Eine hugenottische Französischgrammatik des 18. Jahrhunderts. In Barbara Schäfer-Prieß & Roger Schöntag (eds.), Seitenblicke auf die Französische Sprachgeschichte. Akten der Tagung Französische Sprachgeschichte an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (13–16. Oktober 2016), 143–165. Tübingen: Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

Petersilka, Corina. 2018b. Eine hugenottische Ode aus Erlangen auf Friedrich II., König von Preußen. In Roger Schöntag & Patricia Czezior (eds.), Varia selecta. Ausgewählte Beiträge zur Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft unter dem Motto ‘Sperrigkeit und Interdisziplinarität’, 289–317. München: Ibykos.Suche in Google Scholar

Petersilka, Corina. 2019. Die Familie Meynier als Fallbeispiel hugenottischer Integration in Erlangen. In Roger Schöntag & Stephanie Massicot (eds.), Diachrone Migrationslinguistik: Mehrsprachigkeit in historischen Sprachkontaktsituationen. Akten des XXXV. Romanistentages in Zürich (08. bis 12. Oktober 2017), 213–266. Berlin: Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Pfäffle, Anna. 2020. Sprachkontakt und Sprachenwechsel bei den Erlanger Hugenotten 1686–1830. Erlangen: Unpublished Master thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Pickl, Simon. 2009. Das Kochbuch für Maria Annastasia Veitin. Kommentierte Edition einer Kochbuchhandschrift aus dem Jahr 1748. München: Institut für Volkskunde.Suche in Google Scholar

Polenz, Peter von. 2020 [2009]. Geschichte der deutschen Sprache, 11th edn. Revised by Norbert R. Wolf. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110485660Suche in Google Scholar

Rebmann, Andreas G. F. 1792. Briefe über Erlangen. Frankfurt & Leipzig.Suche in Google Scholar

Rindler Schjerve, Rosita. 1996. Domänenuntersuchungen. In Hans Goebl, Peter H. Nelde, Zdeněk Starý & Wolfgang Wölck (eds.), Kontaktlinguistik – Contact Linguistics – Linguistique de contact. Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung – An international handbook of contemporary research – Manuel international des recherches contemporaines, vol. 1, 796–804. Berlin: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Romaine, Suzanne. 2013. Contact and language death. In Raymond Hickey (ed.), The handbook of language contact, 320–339. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781444318159.ch16Suche in Google Scholar

Schanz, Georg. 1884. Zur Geschichte der Colonisation und Industrie in Franken, vol. 2. Erlangen: Deichert.10.1515/phil-1884-1210Suche in Google Scholar

Schiegg, Markus & Lena Sowada. 2019. Script switching in nineteenth-century lower-class German handwriting. Paedagogica Historica 55(6). 772–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2019.1622574.Suche in Google Scholar

Schöntag, Roger. 2022. Geschichte des französischen Einflusses auf das Deutsche unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Bairischen. Ein Überblick mit zeitgenössischen Quellen. In Roger Schöntag & Barbara Schäfer-Prieß (eds.), Romanische Sprachgeschichte und Sprachkontakt. Münchner Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 337–418. Berlin: Lang.10.3726/b19423Suche in Google Scholar

Thadden, Rudolf von & Michelle Magdelaine (eds.). 1986 [1985]. Die Hugenotten 1685–1985, 2nd edn. München: Beck.Suche in Google Scholar

Topalović, Elvira. 2003. Sprachwahl – Textsorte – Dialogstruktur. Zu Verhörprotokollen aus Hexenprozessen des 17. Jahrhunderts. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Trudgill, Peter. 2003. A glossary of sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Weinreich, Uriel. 1953. Languages in contact. Findings and problems. New York: Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Wilkerson, Miranda E. & Joseph Salmons. 2012. Linguistic marginalities: Becoming American without learning English. Journal of Transnational American Studies 4(2). 1–28. https://doi.org/10.5070/T842007115.Suche in Google Scholar

Wüst, Wolfgang. 2003. Die ‘gute’ Policey im Fränkischen Reichskreis, vol. 2. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.10.1524/9783050047485Suche in Google Scholar

Yardeni, Myriam. 1986. Refuge und Integration. Der Fall Erlangen. In Rudolf von Thadden & Michelle Magdelaine (eds.), Die Hugenotten 1685–1985, 2nd edn., 146–159. München: Beck.Suche in Google Scholar

Zeevaert, Ludger & Jan D. ten Thije. 2007. Introduction. In Jan D. ten Thije & Ludger Zeevaert (eds.), Receptive multilingualism, 1–21. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/hsm.6.02zeeSuche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Language shift in the Erlangen Huguenot community

- Between Nottin’ Ill Gite and Bleckfriars – the enregisterment of Cockney in the 19th century

- Analysing bilingualism and biscriptality in medieval Scandinavian epigraphic sources: a sociolinguistic approach

- Same people, different outcomes: the sociolinguistic profile of three language changes in the history of Spanish. A corpus-based approach

- Personal names in medieval libri vitæ as a sociolinguistic resource

- Book Reviews

- Simon Franklin: The Russian graphosphere

- Raf van Rooy: Language or Dialect? The History of a Conceptual Pair

- Wendy Ayres-Bennett and John Bellamy: The Cambridge Handbook of Language Standardization

- Elvira Glaser, Michael Prinz & Stefaniya Ptashnyk: Historisches Codeswitching mit Deutsch: Multilinguale Praktiken in der Sprachgeschichte

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Language shift in the Erlangen Huguenot community

- Between Nottin’ Ill Gite and Bleckfriars – the enregisterment of Cockney in the 19th century

- Analysing bilingualism and biscriptality in medieval Scandinavian epigraphic sources: a sociolinguistic approach

- Same people, different outcomes: the sociolinguistic profile of three language changes in the history of Spanish. A corpus-based approach

- Personal names in medieval libri vitæ as a sociolinguistic resource

- Book Reviews

- Simon Franklin: The Russian graphosphere

- Raf van Rooy: Language or Dialect? The History of a Conceptual Pair

- Wendy Ayres-Bennett and John Bellamy: The Cambridge Handbook of Language Standardization

- Elvira Glaser, Michael Prinz & Stefaniya Ptashnyk: Historisches Codeswitching mit Deutsch: Multilinguale Praktiken in der Sprachgeschichte