Abstract

The article analyses the historical development and transnational exchange of “red world literature”. A special focus is placed on the proletarian-revolutionary literature (workers’ literature) of the 1920s and 1930s and then on the literature of China and Japan. First, the traditional concepts of world literature, which are often conceived in national, cultural or linguistic “containers”, are critically analysed. As an alternative, a network model is proposed that makes it possible to include literary works from the Global South (the examples are China and Japan) on an equal footing. Following Jürgen Habermas and Nancy Fraser, proletarian-revolutionary literature is understood as the literary movement of a subaltern counter-public that has developed in conscious opposition to the bourgeois literary movement. The article then looks in particular at the circumstances under which China joined the internationalist network of ‘red’ world literature and traces the role of the international proletarian revolutionary writers’ associations and literary conferences, which made a significant contribution to promoting the cross-border exchange of Chinese and Japanese literature. Finally, an explorative study will show how the literature of Chinese and Japanese authors became visible worldwide and what quantitative indicators this network possesses. This is done in a network analysis using GEPHI.

1 Methodological Questions

Research on world literature continuously reflects on itself in the sense of a “semper reformanda” and must constantly realign itself, particularly regarding methodological questions. Since the turn of the millennium at the latest, world literature has emerged as a modern and promising research paradigm, firmly establishing itself in the academic realm. However, to this day, it remains unsatisfactorily clarified what exactly world literature is meant to encompass. Even after 20 years of intensive work – and nothing has fundamentally changed to this day – , it is still unclear how a text can attain the status of world literature, which works are included, and for what reasons certain books are denied this status or not incorporated into a world literary canon. In the preface to the 2018 edition of the Cambridge Companion to World Literature, the editors enumerate five different conceptions of what is currently understood as world literature within the scholarly community: they mention “exotic literature”, “literature beyond the West”, “universal canon of masterpieces”, and point to “innumerable works that travel the world,” asserting that works of world literature “are caught up in an unequal world-system made up of highly developed centers and underdeveloped peripheries.” (Etherington and Zimbler 2018)

What these and many other conceptions have in common, what is to be understood by world literature, can be summarised in the following basic assumptions:

They maintain a binary opposition of center and periphery: “Exotic literature” is considered peripheral, not central. In contrast, Western literature occupies the center, and only translations can elevate peripheral literature to the center.

Another assumption is that often only the complete works of a poet are considered from the point of view of world literature. This also means that a clear distinction is not always made between an author or a work of world literary significance.

Hegemonic and subaltern perspectives are unknown to most conceptions of world literature.

In contrast, a notion of world literature will be advocated here that don’t use these “containers” (Thomsen 2009). “Containers” characterize a way of thinking in rigidly defined and closed categories such as nation, language, national culture, and so forth. However, world literature cannot be packaged in geographical, national, cultural or linguistic “containers” or clearly demarcated from other literatures. Furthermore, world literature cannot be “containerized” into complexes of works, since the notion that every juvenile, experimental, or simply unsuccessful individual work within an author’s complete works should possess world literary status is erroneous. The same applies to the canon: The mere fact that multiple canons exist at different times and even simultaneously underlines that there are very different, if not contradictory inclusion and exclusion criteria for canon formation and that the highly artificial construct of a canon from a sociological perspective is also influenced by the economic interests of publishers and media – canons are by no means independent of time and culture. Additionally, the binary opposition of center and periphery is problematic: the attempts to elevate African literature to the status of world literature, for example, are a long-term process, marked by decolonization, the founding of international publishing houses, the awarding of international literary prizes and a growing global attention to African authors. These attempts can also be understood as economically motivated efforts by Western markets to expand their portfolios, thereby indirectly reinforcing Eurocentric hierarchies.

2 World Literature as a Network

Instead of these numerous “containers” of language, nationality, culture, etc., the concept of the network is discussed below to analyse literary exchange in East Asia. This is because the literatures, their respective authors, publishers and translators are highly interconnected. This is evidenced by international book fairs, international literary prizes and national literary criticism journals that draw attention to literatures from other cultures. The idea of the network also makes it possible to focus on the worldwide interweaving of literary themes, subject matter and motifs. And this in a transnational, cross-cultural and cross-linguistic perspective. The advantages of viewing world literature and the global circulation of literature in terms of a network are as follows: For in terms of a network, instead of a binary opposition that thinks of exchange processes of literature in terms of center and periphery, a literature can be considered that includes the literature of the Global South on an equal footing. The concept of the network also focusses on internationally connected journals. These journals provide information on literature from neighbouring countries and publish translated excerpts from forthcoming book publications. Irrespective of the fact that the inclusion of this periodical literature greatly expands the international perspective, it would also help to overcome the privileging of individual works, including complete works and specific authors.

3 World Literature and the Global South

The term Global South does not refer to a singular actor, but to a collective one, and this Global South is not a fixed entity, but this geopolitical space is fundamentally open to other countries, trading partners, languages and cultural goods. It includes countries that were placed in disadvantaged positions by historical and economic factors and had a colonial past, but which today play an important role in the global system and have an increasing influence on the global economy and politics (Sturm-Trigonakis 2020). The Global South also includes the global economic processes of the worldwide literary market and is not limited to the domestic economy or the book market of a single country. The Global South cannot therefore be categorised in ‘containers’; it is geographically, culturally and linguistically difficult, if not impossible, to delimit or define it. This means that the literature of the Global South is also located in a geopolitical space that is not limited to one continent or one geographically defined country. Nevertheless, the focus here is on the greater East Asian region when talking about the Global South.

4 World Literature and Global History

In order to avoid thinking in terms of the basic assumptions or ‘containers’ of corpus, canon and binary, world literature should be viewed methodologically with the concept of global history. This is because the methodological perspective of global history also focuses on the interrelationships between the various (non-personal) actors, media and practices of the global literary field (Bourdieu 1999). World literature – however it is understood – cannot be considered without the interactions, without the business practices between journal editors, publishers, printers, translation agencies, state funding programs for the translation of literature, institutionalised literary prizes and readerships organised in book clubs. The media here include the numerous literary agencies, the international book fairs and the many literary criticism journals through which knowledge about authors and literatures is disseminated internationally. In addition, all practices of writing, printing, translation, distribution and literary criticism must be considered in the context of their respective socio-economic working conditions and political constraints.

To give just one brief example: Paper, which was necessary for the printing of books and magazines, was used by governments as a means of pressure, for example by restricting the supply of paper to printers in order to prevent socialist publications. Hyperinflation in Germany and Soviet Russia in the early 1920s also led to extreme price increases that made raw materials such as paper simply unaffordable. The role of the Communist International, which organised the financing and supply of paper and other printing materials across national borders in times of crisis, should not be underestimated here.

Global history, not classical literary studies, makes such an approach possible. Such an approach, which increasingly also understands texts and literature as material, can mitigate the strong textual orientation of literary studies, which typically views world literature exclusively as an intellectual entity organised in works and consecrated in canons, but overlooks the fact that these books are printed in paper form, then shipped via global trade routes and circulate internationally in libraries and bookshops as hardbacks or paperbacks. It is simply this dual character of the book, on the one hand being an ‘intellectual product’, but on the other hand not being able to do without its materiality, which is why the inclusion of global history in world literature studies can provide important insights (Mani 2016; see also Labisch 2023). A book or text does not only possess symbolic capital, which can be measured by its status in the process of canonisation or the awarding of prizes (Bourdieu 1999). Books are also enormously material objects that require consignment notes in goods logistics for their transport to international sales markets, in which their ‘value’ is specified in weight or in the number of pallets.

5 World Literature and the Category of Class

Lastly, the analytical category of class must be included in the investigation. This category rarely appears in world literature studies alongside the categories of nation, language, and race/ethnicity. While research on world literature has a critical view on hegemony, it does not center its attention on anti-hegemonic literature. Although it examines literatures far beyond Western language and cultural contexts within a post-colonial framework, it does not investigate subaltern positions within literature. Berthold Schoene asserted that “socioeconomic inequalities” are not a subject of world literature (Schoene 2013). Not much has changed in this regard to this day.

6 Internationalist Workers’ Literature

In addition to these methodological considerations on how to formulate a critically reflected concept of world literature, there must also be an object that can serve as an example of the fact that world literature does not actually have to be “containerized” geographically, nationally, culturally or linguistically, but can be reconstructed in the sense of a network. In the following, this object will be the internationalist workers’ literature of the 1920s and 1930s. This literature can be understood as a literary movement that was strongly influenced by the revolutionary ideas of the Russian October Revolution (1917) and the founding of the Communist International and focused on the interests, experiences and realities of life of the working class. Its aim was to organize the working class through literature, to mobilize it politically and to create an awareness of class struggle, solidarity and social justice. This workers’ literature or “red world literature” (auf der Horst 2023) is therefore a literature that addresses economic and social inequalities and is also a literature that allows literary studies to focus on the hegemonic and subaltern content literarized in it.

7 Literature of the Counter-Public

Thus, attention is brought to literature that is contrary to bourgeois literature in terms of its content because its authors, themes and forms are to be understood as a decidedly counter-design to the bourgeois literary system. For its authors are workers and peasants, its themes come from the world of factories and rural life and describe their respective social hardships, and the forms of this literature are not the high epic or the elegantly told novella, but the workers’ correspondence, the reports and the (so-called) popular proletarian literature.

Not only literature but also the literary exchange of these subaltern authors and texts cannot be encompassed within the categories of a bourgeois concept of literature. Proletarian worker literature does not circulate internationally in the well-known sense that a publisher, for economic reasons, commissions a promising book to be translated and then introduces it into the book market beyond its own national borders in order to increase sales. On the contrary, an appropriate understanding of the proletarian-revolutionary exchange of literature must dispense with the concept of internationality and conventional notions of nation-statehood, national cultural and linguistic spaces. Instead, the exchange of literature took place across all nations – less internationally and more transnationally, if you will. A complete description and explanation of this literature must recognise its deep roots in the socio-political processes that were the condition for its emergence and the reason for its particular form. It must be understood as the literature of a subaltern counter-public that is bound neither nationally, territorially, nor linguistically.

8 Counter-Public and Jürgen Habermas

The proposed focus on transnational and subaltern (not to be containerised) literature must methodologically refer to Habermas’ concept of the public sphere as it was presented – including all criticism and revisions – in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962; and most recently Habermas 2022; cf. also auf der Horst 2025). Habermas’ concept was known to have its weaknesses: it has been tacitly equated with restricted political communities (implicit ‘Westphalian presuppositions’), and, moreover, it overlooked counter-publics such as women and workers, and thus failed to recognise that the bourgeois public sphere is exclusive in nature and excludes women and workers. For only by completing the concept of the public sphere with its trans-territorial scope and, from a stratificatory perspective, with counter-publics such as the proletariat, the workers or the peasants, etc., can the bourgeois perspective be overcome and the exchange of proletarian-revolutionary literature be adequately understood (Fraser 2007).

So how can this subaltern counter-public be described? To a certain extent, its external characteristic, which also describes the condition of its emergence, is its affiliation with the labour and proletarian movement, which gained strength especially after the October Revolution. For this proletarian movement, the belief in a fundamental class difference between workers and citizens is constitutive, with the proletarian belonging to the subaltern class. Equally fundamental to this anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist labour movement is its awareness of being fundamentally detached from national structures. It was internationalist in that it emphasized the commonality of the international working class within a global antagonism of class struggle, irrespective of the principle of nationality.

This does not mean that this counter-public of the labour and proletarian movement can be thought of in essentialist terms. For it is a literary counter-public that performatively creates itself by addressing itself in its literature and creating within its literature the imaginative spaces within which it wants to be thought (Schaub 2019). This counter-public is also constituted literarily in the narrower sense in that this public is constituted via the actors and mechanisms that are typical of participation within a literary field. For example, this literary counter-public discusses its own criteria of literariness (which should lead to Socialist Realism), privileges selected genres, forms its own canons, becomes visible in its own journals, etc. (Schaub 2019).

9 Founding of International Organizations of Proletarian-Revolutionary Literature

Before delving deeper into the performative self-creation of the literary counter-public, it is necessary to say a few words about the genesis and structure of this literary, subaltern and transnational counter-public with regard to its worldwide literary exchange, which, in addition to the USSR and countries of the West, includes China and Japan as important nodes of this network. For this literary exchange is to be understood as a consequence of many international conferences at which the support of national movements in colonised states and the strengthening of the international labour movement were demanded in an explicitly anti-imperialist direction. Anti-imperialism at an international level and anti-hegemonic struggle at a national level went hand in hand. This is what the ‘Congress of the Peoples of the East’, which took place in 1920 in Baku, Azerbaijan with 1900 delegates, including 8 from China, stands for – as perhaps the earliest historical example. The ‘Congress against Imperialism and for National Independence’, which took place in Brussels in 1927 and was also attended by representatives from China and Japan, is also an example of this. The central impulse for integrating literature into this anti-imperialist and anti-hegemonic struggle came from the ‘Fifth World Congress of the Communist International’ in 1924 in Moscow, which called for the founding of a literary international, i.e. the initiation of an international literary movement to support workers’ literature. The ‘International Bureau for Revolutionary Literature’ (IBRL) was founded in 1926 to support this literary internationalisation. The most important result of the work of the IBRL was the ‘First International Conference of Proletarian and Revolutionary Writers’, which took place in Moscow in 1927 and was attended by thirty writers from eleven nations. The formal constitution and establishment of national writers’ organisations was initiated at this conference. At the ‘Second International Conference of Proletarian and Revolutionary Writers’, which took place in Kharkiv (today Ukraine) in 1930, the success of this international cooperation, which was controlled by Moscow, could already be discussed. This conference was attended by 100 delegates from 22 countries in Europe, Asia, Africa and America. For China, there was Xiao San (萧三Siao San; 埃弥-萧 or 爱梅; pen-name Emi Siao) and for Japan there were Fujimori Seikichi (藤森成吉) and Katsumoto Seiichirō (勝本清一郎).

The German Communist Party founded the ‘Bund Proletarisch Revolutionärer Schriftsteller’ (BPRS) in 1928 in response to the demand for national writers’ organisations raised in 1927, and the “All-Japanese Proletarian Art League” (Zennihon Musansha Geijutsu Renmei) was also founded in 1928. The ‘Russian Association of Proletarian Writers’ (RAPP) had already been founded in 1925. In 1930, the ‘Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers’ (Zhongguo zuoyi zuojia Lianmeng; 2 March 1930) and the ‘Bund Proletarisch Revolutionärer Schriftsteller Österreichs’ were founded, followed by the ‘Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires’ (AEAR) in France in 1932 and the ‘League of American Writers’ in 1935. Many of these proletarian-revolutionary writers’ organisations had their own magazines. For example, Die Linkskurve (1929–1932) in Germany, the Japanese Senki (战旗, ‘Battle Flag’; 1928–1931), the French Commune (1933–1939) and Monde (1928–1935), the American New Masses (from 1930) and The Partisan Review (from 1934), and the Chinese ‘Left Wing Writers League’ found its organs in the literary journals of the ‘Sun Society’ and the ‘Creation Society’.

Just as the national organisations published their own literary journals, the IBRL, renamed the ‘International Association of Revolutionary Writers’ (IVRS), published its own literary journal with an international focus from 1928 onwards in order to promote its work of internationalisation. This Messenger of Foreign Literature, published only in Russian from 1928 to 1930, was renamed Literature of the World Revolution in 1931 and appeared in parallel editions in German, English and French. In 1931, it was finally renamed Internationale Literatur, and, in addition to the German edition, a Russian, an English, a French, from June 1942 a Spanish and from January 1935 a Chinese edition were also published, each with different content, as the publication of Internationale Literatur had been placed in the hands of national editorial offices by the IVRS with the intention of providing a better overall view of the different developments of the individual writers’ associations for everyone.

Through the work of the literary counter-public was thus created a structure through which a worldwide exchange of literature could be productively organised: Within a few years from 1927 to 1932, over 15 national writers’ associations had been founded worldwide; in the Asian region, there was a Chinese and a Japanese writer’s association, with the German BPRS having 500 members, the French AEAR 200 and the ‘Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers’ 100 members. Furthermore, many of these writers’ associations were able to be active participants in this counter-public sphere either through their own communication media or through a common medium.

10 China’s Entry into the Network of Internationalist Workers’ Literature

However, this does not yet make transparent what this transnational exchange of internationalist literature looked like in concrete terms. In the following, it will be shown how Chinese authors and Chinese literature in general became an important node in this network of ‘red world literature’. At the above-mentioned ‘Second International Conference of Proletarian and Revolutionary Writers’ in Kharkiv a ‘resolution’ on the situation of Chinese literature was presented, in which the currentsituation of revolutionary literature in China was presented in detail. The literary scene in China was divided into bourgeois, petty-bourgeois and proletarian literature, and their respective main representatives, their literary associations, journalistic organs and works were named. An important main point of the resolution was to point out the tasks that the proletarian-revolutionary literary movement in China would have to tackle in the coming years in order to position itself internationally. The Chinese resolution therefore announced that the ‘League of Left-Wing Writers’, which had only been founded the previous year, would be incorporated into the IVR as a Chinese section in order to be able to participate in internationalization. Specifically, the ‘Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers’ expected support from the IVR in establishing contact with the Japanese and American sections of the IVR – which is what subsequently happened.

In fact, the internationalization of Chinese proletarian-revolutionary literature began with this conference – so that it can be described as the birth of Chinese ‘red world literature’. In January 1931 – just two months after the Kharkiv Conference – the American branch of the IVRS, the magazine New Masses, announced the ‘Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers’ program. In a large essay, the New Masses referred to the literary struggle of Chinese authors against imperial oppression and regretted that they were not better known internationally, which was due to the brutal oppression by the white terror of the Guomindang regime. And finally, the New Masses asked for comradely support for the Chinese writers. A full-page photograph of Lu Xun, who was a kind of ‘spiritual leader’ of the ‘League of Left-Wing Writers’ and who had turned 50, appeared.

In the same issue of the New Masses, Agnes Smedley’s short story A Chinese Red Army appeared. In this short story, she writes about the everyday social life and intellectual life of the persecuted communists, and she also talks about the prominent role of the ‘Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers’ and Lu Xun in it. In February 1931, a three-page report on the Kharkiv Conference appeared in the New Masses, in which the founding of the Chinese Left Wing Writers League is also mentioned. Agnes Smedley also contributes another article in which she traces the founding of the Left Wing Writers League from its many predecessor institutions, such as the “All China Social Scientist’s League”, the “League of Left Dramatic Societies”, or the “Federation of Left Cultural Associations of China”. In summary, Agnes Smedley gives a very detailed report on left-wing intellectual life in China, especially in Shanghai, with a focus on Lu Xun and the magazines he published.

Lu Xun then – prompted by Agnes Smedley – wrote an article for the May issue of New Masses. This text, ‘The present situation of the literary scene in dark China’, was obviously not published in New Masses (Xun 1980). In the following month, June 1931, New Masses published a detailed ‘Letter to the World’ in which the Left Wing Writers League reported on the execution of five Chinese authors by the Kuomintang, drew attention to the precarious situation of the Left Wing Writers League writers and called for comradely, international help.

The degree of networking of internationalist literature can be seen in the fact that this appeal was forwarded by the IVRS Secretariat to the German Die Links-kurve – one of the most important journals financed from Russia – and published there. And Die Linkskurve is itself actively involved in spreading news about the oppression and persecution of revolutionary writers in China. In 1931 alone, three articles appeared in Die Linkskurve calling on revolutionary writers to support the Chinese revolution, strongly criticizing the Kuomintang’s White Terror and the murder of writers, and defending China and Chinese writers against Japanese imperialism.

11 The Worldwide Circulation of Chinese and Japanese Literature in the Internationalist Network

Now it will be shown how Chinese and Japanese authors and their respective literature have spread worldwide in this international network. This aims to address the aforementioned point of demonstrating how the literary counter-public creates itself.

The literary exchange initially manifests as an expression of solidarity when the editors of these internationalist journals, such as Johannes R. Becher (Die Links-kurve), Michael Gold (New Masses), Henri Barbusse (Monde), and others, address the readerships of partner journals in ‘Letters to the Editor’. These ‘Letters to the Editor’ serve not only to draw attention to the precarious situation of the Chinese Writers’ Association and the difficult situation of proletarian-revolutionary writers as a whole but also to emphasize that, despite geographical distances, there exists a significant thematic closeness and agreement on essential beliefs. Detailed reports on the international conferences of writers’ associations further serve this purpose, ensuring that readers are well informed about the conditions of their writer colleagues in other countries. For this reason, new issue numbers with content summaries are frequently announced in each other’s literary journals.

Time and again, the journals in this network also systematically reported on the proletarian revolutionary literature of China and Japan, citing the poets canonised in it and discussing the difficult working conditions. For example, Matsuyama Kodo (松山幸太郎, 1865–1945), Fujimori Seikichi (藤森成吉, 1892–1977), Katsumoto Seiichiro (勝本清一郎, 1906–1983) und Hasegawa Hidetaro (長谷川秀男, 1900–1935) report on Japanese proletarian literature in the German, French and English-language literary journals, while Xiao San (萧三, 1896–1983), Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881–1936) und Hu Lanqi (胡兰畦, 1901–1994) report on the proletarian literary scene in China and analyse the state of proletarian revolutionary literature in their respective countries in a knowledgeable manner. Chinese and Japanese writers are also frequently portrayed in the magazines by translators such as Agnes Smedley, Klara Blum or Anna Louise Strong, who also publish their own written experiences of China or Japan.

The new proletarian-revolutionary literature is also publicised or reviewed in the form of full-page book recommendations. It is therefore not surprising that the journals of this multilingual network also contain partial and complete reprints: ‘The Red Hai-Feng’ by Peng Pai, for example, or ‘The Road Without Sun’ by Sunao Tokunaga, or Takiji Kobayashi’s ‘The 15th March 1928’ and other texts by Xiao San and Fujimori Seikichi. And, of course, in keeping with the later ‘Socialist Realism’ own understanding of literature, it also contains workers’ correspondence from Japanese and Chinese factories, the army and the shipping industry.

The many expressions of solidarity with the Chinese people during this period of struggle for national unity and social renewal in the 1920s and 1930s may have been due to external political circumstances, but internally they were an important instrument in this network for bringing this transnational counter-public sphere to internal coherence. The Japanese writer Seitiro Katsumoto can be cited here as an example of this close alliance that transcended national borders. In a three-page essay in Die Linkskurve of 1931, he urged the proletarian writers of Japan, China and Russia to show solidarity and close ranks against any external adversary.

However, the event that had the greatest resonance in this counter-public was the above-mentioned execution of the five members of the Left Writers’ Association by the anti-communist and nationalist Kuomintang on 7 February 1931 in Shanghai. Hardly any other event has generated such solidarity and had such a strong impact on this network of magazines, from printing photo portraits of those killed, to pages of commentary and references to their biographies, to calls for worldwide protest.

12 Technical Network Analysis of the ‘Red’ World Literature Network Using the Example of Chinese and Japanese Literature

The analysed network is a comparatively small network consisting of only 41 nodes and 67 edges. This is because the focus of this analysis is initially on authors of Chinese and Japanese origin who were recognised in the journals of internationalist ‘red’ literature and had achieved international significance. This is therefore only an exemplary section of a much more extensive network, which included many authors and many journals from many other countries in a wide variety of forms (translated partials of books, original works, reports on the political-social situation of selected working-class writers, introductions and reviews of selected literature, etc.).

Even though the central publication organs of the network, such as Internationale Literatur, or journals from Germany, France and the USA, were taken into account for this first exploratory survey, the network naturally includes journals from China and Japan. In addition to the Linkskurve and the Rote Fahne, other Münzenberg Group journals such as the Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung or Der Weg der Frau would also be relevant for the German-speaking world; in the USA, The Worker’s Monthly and in France Henri Barbusse’s Clarté should also be mentioned – to give just a few examples of the fact that the network was far larger in its dimensions than presented here.

The reporting period for the analysis is also limited to 10 years, namely July 1928 to August 1938. However, the internationalist network of red literature becomes visible from the early 1920s at the latest and then comes to an end with the rise of European fascism, at the latest with the outbreak of the Second World War, although it does not come to a complete standstill.

This network, reduced here to its core elements, was created as a bi-partite (author nodes and journal nodes) network with directed edges (authors appear in journals, not the other way round). It was then analysed not only as a directed but also as an undirected network so that the node connections could be examined with regard to their centrality measures. This approach is justified insofar as the relationships between the journal nodes are symmetrical – authors publish independently in several journals.

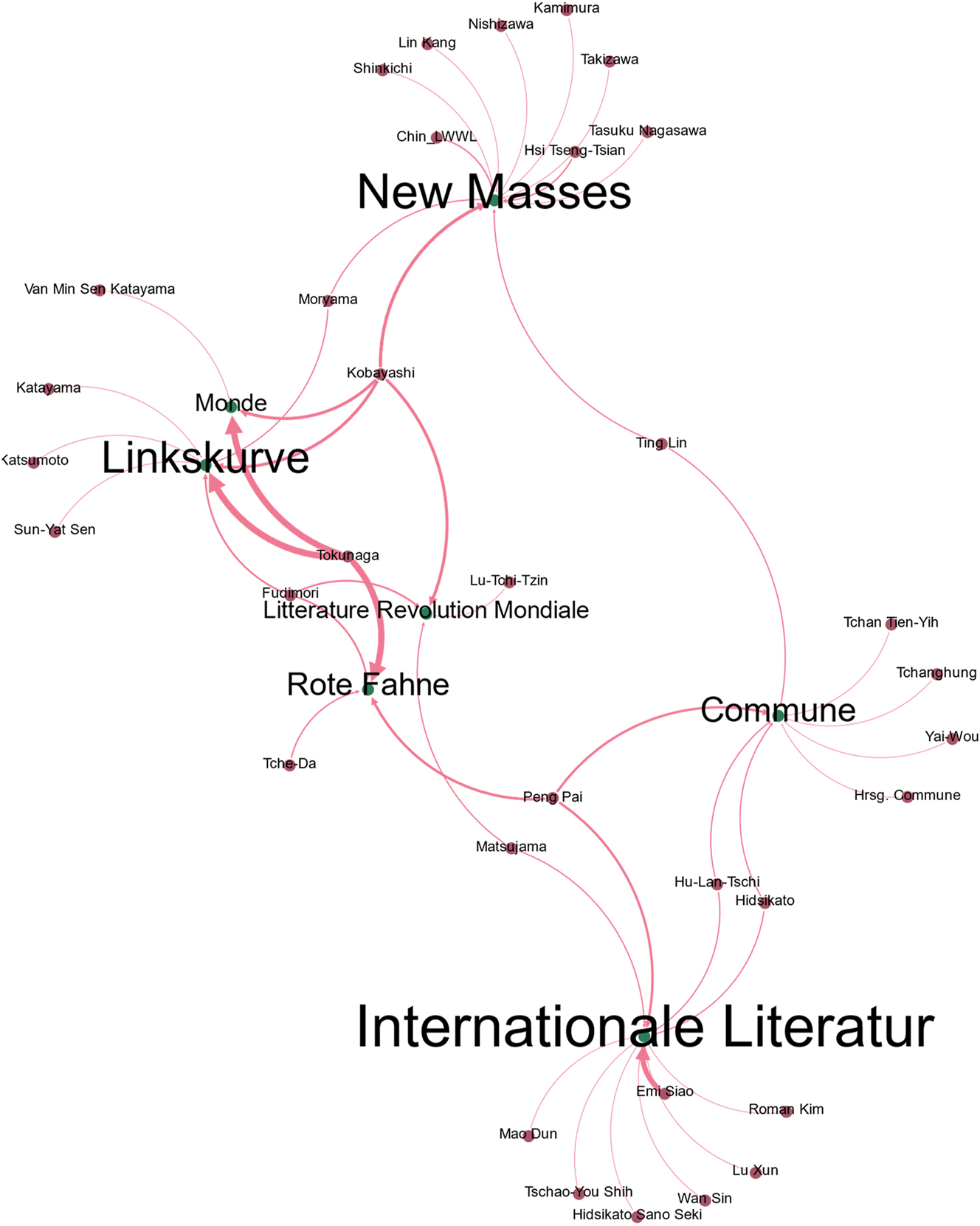

As the analysis and visualisation of the network with Gephi (Figure 1) shows, the journal Internationale Literatur has both the highest in-degree value (sum of all incoming connections) and the highest weighted-degree value (also taking into account the weights of the edges) at 18 and 80 respectively. In comparison, New Masses, as the second strongest journal, only achieves the corresponding values of 14 and 28 and thus lags behind the Linkskurve in the weighted degree value, which has a strength of 78 despite only 12 edge connections.

Visualisation of the network with highlighting of the journal nodes according to the direction and strength of their connections.

The evaluation of a network also requires the consideration of metrics such as harmonic closeness centrality, betweenness centrality and eigenvector centrality. These measures provide information on how easily a node can be reached, how often it acts as an intermediary on the shortest paths between other nodes, and how its importance is to be assessed relative to its neighbouring nodes.

The highest closeness value (0.5025) is achieved by New Masses, which indicates good accessibility in the overall network. Internationale Literatur (0.4795) and Commune (0.45625) score slightly lower here. Comparable results can be seen for betweenness centrality, which makes it clear that these three journals act as important mediators or bridges between other nodes. In the eigenvector centrality, however, Internationale Literatur, Linkskurve and Rote Fahne rank first, with New Masses in fifth place, even behind Monde. This suggests that, despite its accessibility, New Masses is less closely linked to other central nodes than its German-language sister magazines. Obviously, Internationale Literatur plays a key role in the network both directly and indirectly.

So far, only the centrality measures of the journal nodes have been analysed, but the network also consists of author nodes. It is characteristic of this network that selected authors either publish or are mentioned in several different journals; their connecting element is reciprocal references to authors and literature from other countries and journals, whether in editorials, book advertisements, book reviews or author recommendations. From the point of view of the magazines, these authors and their literature are considered to be of great importance for the internationalist cause, their literature is seen as exemplary and the circumstances described therein are seen as creating solidarity, even if this does not apply in the same way to each of the 34 authors and publishers who are mentioned or referred to in the magazines.

As Figure 2 shows, Tokunaga and Emi Siao have very high outdegree values, which indicates that these authors heavily reference other nodes/journals. Kobayashi, Peng Pai and Fudimori remain in third to fifth place. These values alone are not yet very meaningful, because on the other hand Emi Siao, for example, has a betweenness factor of 0, and Tokunaga is also in fourth place in the betweenness centrality of the five shortest edges between different journal nodes. The mediating role of Emi Siao is therefore very small, despite its great importance for Internationale Literatur; but in fact Emi Siao is only mentioned in Internationale Literatur, otherwise in no other journal. In contrast, Peng Pai has the highest betweenness centrality with a value of 0.2374, followed by Kobayashi (0.2055) and Ting Lin (0.1766). To measure this betweenness, not only the frequencies of the shortest paths between other nodes/journals are used, but also the strategically important positions these authors occupy for the overall network, because the importance of a node is influenced by the overall structure of the network. The example of Ting Lin shows that without this author, there would be no contact between the important New Masses of the USA and the Commune of France.

Visualisation of the network with highlighting of the author nodes and their respective importance for selected journals.

The network analysed here appears to be relatively compact and well connected from an overall perspective. There are no extremely large distances between nodes (Diameter = 6), and most nodes can be reached in a few steps (Average Path Length = 3.6). The radius of 4 indicates that there are some central nodes that strongly hold the network together. Even if this is not yet too meaningful for a network of this size, an attempt should nevertheless be made to divide this network into smaller clusters that belong together. This is because the clustering coefficients, which indicate whether and to what extent the neighbours of a node or a subgroup of the overall network are connected to each other, are all equal to 0. However, it can be said with caution that a first central cluster is grouped around Internationale Literatur and the author Emi Siao. A second group consists of the Rote Fahne and the Commune together with the authors Ting Lin, Peng Pai, Hidsikato and Fudimori. As a third subgroup, Gephi uses the Louvain algorithm to show the cluster around the journals Linkskurve and Monde and then, above all, around the author Tokunaga. The last group in the modularity analysis consists of New Masses and Littérature de la Révolution Mondiale and the authors Kobayashi, Motsujama and Maruyama.

Finally, if one were to cautiously attempt to identify the most important magazines and authors for the functionality of the overall network, remembering that the network was kept small for pragmatic reasons, then in terms of the greatest influence, the strongest cohesion and the most central position, the magazines Internationale Literatur, Rote Fahne and New Masses would be listed first, with Takiji Kobayashi and Peng Pai as authors. In second place would be Linkskurve, Commune and Littérature de la Révolution Mondiale, with Suano Tokunaga and Ting Lin as authors.

In terms of content, the texts that formed the network of the above-mentioned writers and led to the formation of the proletarian counter-public sphere should be mentioned here. Of great relevance here is the short story ‘March 15, 1928: A Japanese Workers’ Tale’ from 1929, in which Takiji Kobayashi describes the events surrounding a large-scale wave of arrests of revolutionary workers, farmers and intellectuals in Japan on 15 March 1928. Kobayashi portrays the solidarity and determination of the workers, who stood up for their rights and the revolution despite the repression. The book ‘The Red Hai-Feng’ from 1926 also belongs here, in which Peng Pai describes the activities of the Haifeng Peasants’ Association he founded, which then led to the founding of the Hailufeng Soviet in 1927, the first and short-lived Soviet government in China. Suano Tokunaga then wrote the important workers’ novel “The Road Without Sun”, which was published in 1929 and in which Tokunaga describes his own experiences as a worker and trade unionist, thus portraying the life of the Japanese working class. Finally, Ting Lin must be mentioned here, although it is not her 1927 novella ‘The Diary of Sophia’ that appears in the internationalist network, but a short story entitled ‘Sans Titre’ (《无题》), in which the everyday atrocities of the armed conflicts in the 1920s and 1930s are described from the perspective of the soldiers involved.

13 Conclusions

These four books, which mark central network positions, show impressively that this transnational network obviously gave Japanese and Chinese workers, farmers and soldiers a widely audible voice. And because these books and voices circulated worldwide, a transnational, subaltern and anti-hegemonic counter-public was able to form. However, the density of this network, whose contours could only be hinted at here, would diminish again over time. The stronger the repressive effect of Hitler’s fascism against communism in Europe became, the more difficult it became for the journals of this internationalist network to survive. Time and again, issues of the magazines were confiscated, the publication rhythm changed, the magazines were renamed, and so on. Die Linkskurve ceased its publication completely in Germany in 1932, Commune in 1939 and Internationale Literatur only in 1945. Many of the European proletarian-revolutionary writers went into exile. Something similar happened at the same time in China, where many writers fell victim to the White Terror. But by this time, the subaltern counterpublic sphere had already formed so sustainably and the structure of this worldwide, transnational network was already so strong that it could not be finally extinguished despite the Second World War in Europe, despite the Chinese struggle for national unity and despite the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a lecture at Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China in September 2023 and a lecture at the 16th Annual Meeting of the Society for Cultural Interaction in East Asia, Kansai University, Awara Onsen Seifuso, Japan, May 2024. I am also grateful for the support of the National Foreign Experts Program, China.

-

Ethical approval: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no competing interests.

-

Research funding: None declared.

References

auf der Horst, Christoph. 2023. “Heinrich Heine und die ‘rote Weltliteratur’.” The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory 98 (1): 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00168890.2022.2161339.Suche in Google Scholar

auf der Horst, Christoph. 2025. “Literaturkritik und Öffentlichkeit.” In Handbuch Literaturkritik. Geschichte – Systematik – Praxis, edited by Christoph auf der Horst, and Susanne Brenner-Wilczek. Stuttgart: Metzler.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1999. Die Regeln der Kunst: Genese und Struktur des literarischen Feldes. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Etherington, Ben, and Jarad Zimbler, eds. 2018. The Cambridge Companion to World Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108613354Suche in Google Scholar

Fraser, Nancy. 2007. “Die Transnationalisierung der Öffentlichkeit: Legitimität und Effektivität der öffentlichen Meinung in einer postwestfälischen Welt.” In Anarchie der kommunikativen Freiheit, edited by Berndt Herborth, and Peter Niesen, 224–53. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1962. Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit: Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft. Neuwied: Luchterhand.Suche in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 2022. Ein neuer Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit und die deliberative Politik. Berlin: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Labisch, Alfons. 2023. “The Emergence of a Global Knowledge Network: Beginnings and Foundations of the Global Dissemination of Knowledge in Europe and China from Antiquity to Early Modern Times. Some Historical, Theoretical, and Methodological Annotations.” Journal of Cultural Interaction in East Asia 14 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/jciea-2023-0005.Suche in Google Scholar

Mani, B. Venkat. 2016. Recoding World Literature: Libraries, Print Culture, and Germany’s Pact with Books. New York: Fordham University Press.10.26530/OAPEN_626400Suche in Google Scholar

Schaub, Christoph. 2019. Proletarische Welten: Internationalistische Weltliteratur in der Weimarer Republik. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110668087Suche in Google Scholar

Schoene, Bernd. 2013. “Weltliteratur und kosmopolitische Literatur.” In Handbuch Kanon und Wertung. Theorien, Instanzen, Geschichte, edited by Gabriele Rippl, and Simone Winko, 356–63. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.Suche in Google Scholar

Sturm-Trigonakis, Elisabeth. 2020. World Literature and the Postcolonial: Narratives of (Neo)Colonialization in a Globalized World. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.10.1007/978-3-662-61785-4Suche in Google Scholar

Thomsen, Mads Rosendahl. 2009. Mapping World Literature: International Canonization and Transnational Literatures. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Xun, Lu. 1980. In The present condition of art in darkest China. Selected Works, Vol. 3, Translated by Yang Xianyi, and Gladys Yang, 122–26. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Different Perceptions of “Interconnection” in Global History in the East and West – Possible Contributions from the East Asian Tradition to the Study of Global History

- A Study on the Social Integration of Chinese Immigrants in Cape Verde

- The Exchange of East Asian Literature in the Global Network of International Solidarity

- Production Background of the Baekje Gilt-Bronze Incense Burner in Light of Boshanlu’s Emergence and Transformation

- Book Review

- Prado-Fonts, Carles: Second-Hand China - Spain, the East, and the Politics of Translation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Different Perceptions of “Interconnection” in Global History in the East and West – Possible Contributions from the East Asian Tradition to the Study of Global History

- A Study on the Social Integration of Chinese Immigrants in Cape Verde

- The Exchange of East Asian Literature in the Global Network of International Solidarity

- Production Background of the Baekje Gilt-Bronze Incense Burner in Light of Boshanlu’s Emergence and Transformation

- Book Review

- Prado-Fonts, Carles: Second-Hand China - Spain, the East, and the Politics of Translation