Abstract

A common problem of interest within a randomized clinical trial is the evaluation of an inexpensive response endpoint as a valid surrogate endpoint for a clinical endpoint, where a chief purpose of a valid surrogate is to provide a way to make correct inferences on clinical treatment effects in future studies without needing to collect the clinical endpoint data. Within the principal stratification framework for addressing this problem based on data from a single randomized clinical efficacy trial, a variety of definitions and criteria for a good surrogate endpoint have been proposed, all based on or closely related to the “principal effects” or “causal effect predictiveness (CEP)” surface. We discuss CEP-based criteria for a useful surrogate endpoint, including (1) the meaning and relative importance of proposed criteria including average causal necessity (ACN), average causal sufficiency (ACS), and large clinical effect modification; (2) the relationship between these criteria and the Prentice definition of a valid surrogate endpoint; and (3) the relationship between these criteria and the consistency criterion (i.e. assurance against the “surrogate paradox”). This includes the result that ACN plus a strong version of ACS generally do not imply the Prentice definition nor the consistency criterion, but they do have these implications in special cases. Moreover, the converse does not hold except in a special case with a binary candidate surrogate. The results highlight that assumptions about the treatment effect on the clinical endpoint before the candidate surrogate is measured are influential for the ability to draw conclusions about the Prentice definition or consistency. In addition, we emphasize that in some scenarios that occur commonly in practice, the principal strata subpopulations for inference are identifiable from the observable data, in which cases the principal stratification framework has relatively high utility for the purpose of effect modification analysis and is closely connected to the treatment marker selection problem. The results are illustrated with application to a vaccine efficacy trial, where ACN and ACS for an antibody marker are found to be consistent with the data and hence support the Prentice definition and consistency.

1 Introduction

An important goal of many biomedical research fields is identification of surrogate endpoints based on randomized clinical efficacy trials. With precise notation defined in Section 1.1, we have one randomized treatment (Z) for which two endpoints S and Y are both measured in each of the groups

The term “surrogate” has been used for many objectives of biomarker research in clinical trials, and in our view it may be most clearly used for the “replacement endpoint” concept, thereby distinguishing surrogate/replacement endpoint assessment research from other biomarker assessment research. For example, as discussed below, studying biomarker-based subgroup effect modifiers of clinical treatment efficacy is useful for targeting treatments/interventions to subgroups where they will work and for selecting biomarker study endpoints for evaluating treatments in new Phase 1–2 trials. Biomarker response endpoints are also useful for exploring biological mechanisms of clinical treatment efficacy and for studying mediators of clinical treatment efficacy, which are distinct research activities with different objectives than surrogate/replacement endpoint evaluation.

Ideally, validation of a surrogate endpoint would be based on a synthesis of information from a large number of previous randomized trials of the same or similar treatments versus control where the surrogate and clinical endpoints were both measured (e.g. Gail et al. [1] considers this approach). However, it often occurs that data on the surrogate and clinical endpoint are available from only a single randomized trial, such that it is of interest to study definitions and criteria for useful surrogate and biomarker endpoints that are applicable for the identical setting as this single trial. While these definitions and criteria will be insufficient for validating surrogates or biomarkers for the ultimate goal of inferring clinical treatment effects of new treatments in the same or new setting, they are useful as a first step toward this objective and they aid clinical research in other ways that we discuss. We focus on the Prentice [2] definition of a valid surrogate endpoint and on the principal stratification framework. This article is primarily about relating statements about the full-data distribution, although identifiability by the observed data distribution is also discussed and addressed in the application.

We state some of our conclusions up front. First, the literature discussing the utility of the Prentice [2] surrogate framework has been inadequately clear in discriminating the Prentice definition (on obtaining a valid test of the null hypothesis of no clinical treatment effect from the surrogate alone) from criteria (e.g. conditions on the observed data distributions

Secondly, the principal stratification/principal surrogate framework does not in general provide a way to check the Prentice definition. We show that, depending on the problem context, principal stratification-based criteria can provide no discriminating information, partial discriminating information, or complete discriminating information about the Prentice definition. Therefore, the principal stratification framework has main utility for assessing whether and how treatment efficacy varies by subgroups defined by levels of biomarker response, thus being closely aligned with the utility of the treatment marker selection problem. In special cases, however, principal stratification criteria can establish the Prentice definition or one of its components specificity or sensitivity, and can also guarantee avoidance of the surrogate paradox (as illustrated in the application). In addition, the principal surrogate framework does fit the valid replacement endpoint concept, but in a different way than the Prentice definition. In particular, by providing a point and confidence interval estimate about clinical treatment efficacy for individuals based on their biomarker response values, it provides information about the clinical treatment effect for future subjects (from the same population) based on the biomarker endpoint alone without measurement of the clinical endpoint.

1.1 Setup of randomized trial for assessing clinical efficacy

We consider a single clinical trial that randomizes n participants to active intervention (e.g. treatment or vaccine) versus a control intervention such as placebo, with Z the indicator of assignment to active intervention. Participants are followed for a fixed follow-up period for occurrence of the primary endpoint Y by time

1.2 Background: published definitions and criteria for a principal surrogate endpoint

Joffe and Greene [4] reviewed four frameworks for evaluating surrogate endpoints. The current article focuses on the principal stratification framework in comparison to the Prentice definition of a valid surrogate endpoint [2] (but not to the Prentice criteria). Prentice stated his definition as “a response variable for which a test of the null hypothesis of no relationship to the treatment groups under comparison is also a valid test of the corresponding null hypothesis based on the true endpoint.” As stated in the first paragraph of the Introduction, S is a valid surrogate endpoint if measurement of

This article focuses on evaluating a candidate surrogate from a single randomized clinical trial, for evaluating its quality for the same setting as that trial. As such, within the frequency framework of statistics, satisfaction of the Prentice definition means that if the surrogate endpoint is used in an identical trial, then inference of the treatment effect on the surrogate is guaranteed to provide correct inference (in the dichotomous sense of correctly accepting or rejecting the null hypothesis) about the treatment effect on the clinical endpoint. While not directly relevant for answering the important question of whether the surrogate will be valid for a new treatment in the same or new setting, such a result is still useful because it provides indirect evidence that the surrogate would approximately satisfy the Prentice definition for a new treatment if the treatment is similar to the original treatment (e.g. in the same drug class). If two candidate surrogates are assessed in a single efficacy trial and one satisfies the Prentice definition and one does not, then it may be rational to prioritize the Prentice surrogate as a study endpoint in subsequent Phase 1/2 trials of new and similar treatments that will constitute the basis for selecting the most promising new treatment to advance to the next efficacy trial.

Several papers have considered definitions and criteria for a useful principal surrogate endpoint. Within the potential outcomes framework of causal inference, Frangakis and Rubin [3] defined S to be a principal surrogate if every individual with a causal treatment effect on the clinical endpoint Y also has a causal treatment effect on the surrogate S (i.e. “causal necessity”). This definition states that a valid surrogate satisfies

With

and ACN is expressed as CEP

Moreover, both Frangakis and Rubin [3] and Gilbert and Hudgens [5] expressed the concept that studying the whole CEP surface is important for evaluating the utility of a candidate principal surrogate; the former authors expressed this by stating that a more useful biomarker will have relatively more associative than dissociative effects, whereas the latter authors expressed this by stating that a more useful biomarker will have wide variability in the CEP surface over subgroups defined by

The marginal CEP curve causal parameter, closely related to the CEP surface, is also useful for evaluating a principal surrogate, which contrasts the risks averaged over the distribution of

While ACN and ACS are not in general defined for this causal parameter, the “wide variability/strong effect modifier” principal surrogate criterion is operable, and identifiability is achieved under weaker assumptions [6]. Below we consider both the CEP and mCEP full-data causal parameters as useful quantities for evaluating and understanding principal surrogate quality.

Our results below use an additive difference contrast

which is the proportion of the study population with a beneficial clinical effect that also has a positive surrogate effect. (This definition assumes no clinical events before

Additional work clarified the value or limitations of the above criteria for a biomarker’s utility as a principal surrogate and suggested new criteria. VanderWeele [10] showed that ACN can hold yet the treatment has a causal effect on Y not mediated through S. For example, this situation may occur if there are two independent biological mechanisms of clinical protection, one that operates directly through S and one that does not. On the positive side for ACN, VanderWeele [10] also showed that failure of ACN does imply that the treatment has a causal effect on Y not mediated through S; thus, ACN is a valid criterion to “disprove” full mediation but cannot affirm it. (Thus Frangakis and Rubin’s [3] principal surrogate definition is about a one-way implication, different from the if and only if implications of the Prentice definition.) In addition, Gilbert et al. [11] emphasized that, for the purpose of iteratively developing increasingly efficacious treatments, ACN and ACS may be less important for a useful principal surrogate than the strong effect modifier criterion that CEP

Another criterion for a good surrogate endpoint is the original Prentice [2] definition of a valid replacement endpoint for the clinical endpoint, and below we provide results on the implications of ACN + one-sided strong ACS on the Prentice definition and vice versa. The results show how the implications depend on assumptions about causal treatment effects on the clinical endpoint before and after the biomarker is measured. These implications yield alternative criteria to the original Prentice criteria for checking the Prentice definition of a valid surrogate endpoint.

Many authors including Chen et al. [13], Ju and Geng [14], and VanderWeele [15] rightly assert that a reasonable surrogate endpoint should be assured to avoid the “surrogate paradox” pitfall, defined as the scenario where the effect of the treatment on the surrogate is positive, the surrogate and clinical outcomes are positively correlated, yet the overall clinical treatment effect CE indicates harm by the active treatment. Below we note scenarios, which commonly occur in practice, for which ACN plus one-sided strong ACS guarantee a “consistent surrogate” (defined as the surrogate paradox cannot happen).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 clarifies that principal surrogate analysis is essentially subgroup effect modification analysis. Section 3 provides results on ACN and one-sided ACS as criteria for checking the Prentice surrogate definition. Section 4 provides results on these criteria for checking a consistent surrogate. Section 5 illustrates the relationships with a Zoster vaccine (ZV) efficacy trial, Section 6 provides discussion, and the appendix contains proofs of results.

2 Principal surrogate assessment: subgroup effect modification analysis

2.1 Connection to the treatment marker selection problem

Principal surrogate analysis is subgroup analysis (hence suggesting a name such as principal stratification effect modification analysis), with an objective to characterize how clinical treatment efficacy varies over subgroups, where these subgroups are defined by post-randomization principal strata (which by construction may be treated as baseline covariates) and possibly also by actual baseline covariates. The analysis essentially repeats the overall intention-to-treat analysis for each of a range of these subgroups, assessing the effect of treatment assignment on disease risk within each subgroup, and, like the overall analysis, provides little or no direct information about mechanisms or mediators of protection. As such, the principal surrogate problem has a close connection with the “treatment marker selection problem,” which has a goal to determine if and how clinical treatment efficacy varies over subgroups defined by biomarkers measured at baseline (e.g. Huang et al. [16]). While the statistical approaches for these two problems are highly related, the applications are partly overlapping and partly distinct; for instance, both fields seek to rank biomarker endpoints by their strength of effect modification and hence utility for treatment development, but, unlike the treatment marker selection field that often focuses on individual decision making for tailored allocation of therapy, the principal surrogate field has focused on different applications including the prediction of overall treatment efficacy from the biomarker distribution in a similar or new setting [17, 18]. In addition, the treatment marker selection field does not endeavor to identify “perfect” or “valid” treatment selection markers; rather it focuses on characterizing efficacy over subgroups and the ranking of biomarkers by the strength of effect modification. Similarly, principal surrogate evaluation is primarily about comparing candidate surrogates and ranking them by the degree of their utility as effect modifiers, and the field should not be dominated by the objective to identify perfect/valid surrogates. Nevertheless, the joint criterion of ACN together with strong ACS has particular value in checking the Prentice definition or the individual components of the Prentice definition as described below.

The analogy with the treatment marker selection literature also suggests that if very strong baseline effect modifiers exist, then it may be unimportant to develop a biomarker response effect modifier – one can simply predict clinical treatment effects based on actual baseline variables, avoiding the identifiability challenges of the principal stratification framework (Ross Prentice has voiced this point). While true, in practice a response to treatment may be a stronger effect modifier, motivating principal surrogacy assessment, and many such examples exist. The analogy also raises the question as to when the principal strata subgroups are identifiable from the observable data, as an affirmative answer to this question places the principal stratification problem much closer to the treatment marker selection problem where subgroups are obviously directly observable.

2.2 Is the principal stratum for inference observable?

A key issue for the utility of principal stratification research in general is whether the principal stratum for inference is observable versus latent and never observable. Many principal strata of interest in a variety of applications are not observable, rendering the approach unhelpful for decision making for individual patients or for health policy (e.g., Joffe [19]). However, for present application there is a special case where the principal stratum for inference is identifiable from the observable data, the “Constant Biomarker” scenario (i.e. the conditional distribution

While Case CB has been motivated by vaccine efficacy trials, it also may occur in general active treatment versus control randomized trials with S defined as the difference in a biomarker readout between time

In sum, if the principal strata subgroups are identifiable from observable random variables, then principal stratification effect modification assessment has utility similar to baseline covariate subgroup analysis of effect modification, whereas otherwise, the utility is reduced, but still present for the purposes of ranking candidate biomarkers and for providing inputs into bridging formulas for predicting overall treatment efficacy.

3 Connection of ACN and one-sided ACS with the Prentice definition of a valid surrogate endpoint

3.1 Prentice definition

A criterion for a good principal surrogate endpoint is satisfaction of Prentice’s [2] definition as a valid replacement endpoint for the clinical endpoint. This definition may be expressed as perfect population-level specificity and sensitivity of the surrogate. Henceforth we use

We define two-sided and one-sided versions of Specificity and Sensitivity as follows:

We use the contrapositive forms of two-sided Specificity and one-sided Specificity to distinguish them:

Specificity means that rejecting the null hypothesis of no treatment effect on the surrogate implies a treatment effect on the clinical endpoint (CE

3.2 Overall clinical efficacy averaged over the CEP surface

Criteria for checking Specificity and Sensitivity may be derived solely based on observable random variables, without the need for potential outcomes, following Prentice [2] and subsequent work. However, in this work we study the relationship of Specificity and Sensitivity to ACN and one-sided ACS, which requires potential outcomes notation. In Section 5 we provide an example where principal stratification effect modification analysis supports ACN + one-sided strong ACS for a biomarker endpoint, generating the question of what does this imply about whether Specificity and/or Sensitivity hold? As a preliminary step, we partition CE as a weighted average of the CEP surface across subgroups. The results are developed for the additive difference contrast function

Define

for

Throughout we assume

3.2.1 CE Decomposition

The above decomposition is useful for judging the utility of ACN, ACS, and wide variability in CEP

The overall efficacy CE is a weighted average of the CE

3.3 Results on the relationship of ACN and one-sided ACS to Specificity and Sensitivity

We consider a menu of assumptions that will be selected from to infer results.

Equal Early Clinical Risk (EECR):

Early No-Harm Monotonicity (ENHM):

Population Early Monotonicity (PEM): CE

No Negative Marker Effects (NNMEs):

Monotonicity: CEP

Case CB:

The following results attain, with proofs in the appendix. For these results we re-define ACN and one-sided ACS slightly as follows. ACN is CEP

Result 1 (Under EECR): EECR + ACN + Case CB imply Sensitivity. Conversely, EECR + Sensitivity + Case CB imply ACN. Apart from Case CB, EECR + ACN do not imply Sensitivity and EECR + Sensitivity do not imply ACN, even under all four of the extra assumptions PEM + NNMEs + Monotonicity + Case CB.

EECR + ACN + one-sided strong ACS imply Specificity under any of NNMEs, Monotonicity, or Case CB. Conversely, EECR + Specificity + Sensitivity do not imply one-sided ACS for any

Result 2 (Under ENHM): ENHM + ACN do not imply Sensitivity even under all four of the extra assumptions. Conversely, ENHM + Sensitivity + Monotonicity + Case CB imply ACN.

Similar to Result 1, ENHM + ACN + one-sided strong ACS imply Specificity under any of NNMEs, Monotonicity, or Case CB, whereas ENHM + Specificity + Sensitivity do not imply one-sided ACS for any

Result 3 (General): ACN does not imply Sensitivity even under all four of the extra assumptions. Conversely, Sensitivity + PEM + Monotonicity + Case CB imply ACN.

ACN + one-sided strong ACS + PEM imply Specificity under any of NNMEs, Monotonicity, or Case CB. As for Results 1 and 2, Specificity + Sensitivity do not imply one-sided ACS for any

Results 1 and 2 show that the principal surrogate conditions can be used to check the two parts of the Prentice definition. They show that EECR + Case CB are needed for inferring the full Prentice definition from ACN and one-sided strong ACS, where relaxing either one loses the implication. Results 1 and 2 also show the importance of EECR for the principal surrogate criteria to have implications on the Prentice definition (required for inferring Sensitivity), even under all four extra assumptions PEM, NNMEs, Monotonicity, and Case CB. Results 1 and 2 also show that the Prentice definition does not imply ACS even under many possible assumptions; the basic reason is that there are many ways for CE

A useful application of Result 3 is that in general applications where PEM and NNMEs or Monotonicity hold (which is often plausible), if the estimated vaccine efficacy curve takes the classic shape of being near zero at

Next we state Result 1 for the special case that S is binary. The results on implications of ACN and ACS for Sensitivity and Specificity are unchanged, whereas the reverse implications are strengthened. In contrast, Results 2 and 3 are unchanged for S binary compared to S categorical with more than two categories.

Result 1-Binary (Binary S Under EECR): In the special case of S binary and EECR + Case CB, ACN implies Sensitivity and Sensitivity implies ACN. In addition ACN plus one-sided strong ACS imply Specificity and Sensitivity + Specificity imply one-sided strong ACS.

Result 1-Binary shows that EECR + Case CB + S binary constitutes a scenario where both principal surrogate conditions hold if and only if the Prentice definition holds. For a binary S the Prentice definition does not have implications on ACS if EECR is relaxed, however, further highlighting the importance of EECR.

3.4 Results under minor violations of Case CB and EECR

In the example described in Section 5, there may be minor violations of the Case CB and EECR assumptions, raising the question of whether the results are approximately correct under such violations. We state a variant version of Result 1 to address this question with proof in the appendix, and note that the other results have similar properties under minor violations. We use the following extension of the notation.

Define Case CB-

Result 4 (Result 1 Under Minor Violations of Case CB and EECR): EECR + ACN-

Result 4 implies that the principal stratification criteria do correctly check the Prentice definition under minor violations converging to zero in that Sensitivity-

Result 2 extends to a result where ENHM-

3.5 Interpretation and testability of the assumptions

The first two assumptions EECR and ENHM are about the effect of treatment on Y before the biomarker is measured. The stronger assumption EECR assumes no effect for any individual, and has been used for all but one paper on evaluating a principal surrogate, given the great help it provides toward identifying the CEP surface and the marginal CEP curve. Wolfson and Gilbert [6] considered sensitivity analysis methods that relax EECR to ENHM or to no assumption about early treatment effects. EECR and ENHM are not fully testable but have testable implications, e.g. they can be rejected by finding early clinical treatment effects overall or in subgroups.

PEM is only relevant if EECR fails, as under EECR

4 Connection of ACN and one-sided ACS with verifying a consistent surrogate

As argued by several authors including Fleming and DeMets [24], Chen et al. [13], Ju and Geng [14], and VanderWeele [15], a good surrogate endpoint should be assured to avoid the “surrogate paradox” pitfall, defined as the scenario where the treatment effect on the surrogate is positive (i.e.

5 Application to the ZEST

We apply the above results to the Phase 3 Zostavax Efficacy and Safety Trial (ZEST), which randomized 22,439 North American and European subjects aged 50–59 years in a 1:1 allocation to receive attenuated ZV or Zostavax (Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ) or placebo, with primary objective to assess the vaccine efficacy to prevent herpes zoster (HZ). Schmader et al. [25] reported an estimated overall vaccine efficacy of 69.8%, using a 1 – relative risk (vaccine/placebo) estimand × 100%. Here we focus on the additive difference estimand CE

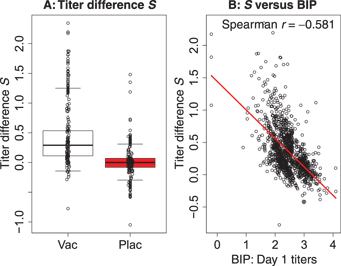

For vaccine and placebo recipients in the immunological substudy of ZEST (chosen as a 10% simple random sample, n = 1,218 vaccine and n = 1,273 placebo), the (A) boxplots depict the distribution of

We conduct the analysis assuming Case CB such that

EECR is plausible and ENHM highly plausible, with 5 of 11,184 vaccine recipients and 8 of 11,212 placebo recipients experiencing the primary endpoint by

We applied the Weibull-model estimated-likelihood method of Gabriel and Gilbert [20] to estimate CEP

We maximized the estimated likelihood using a parametric normal model for

![Figure 2 Point and 95% confidence interval estimates of the CEP curve, CEP(s1)≡CEP(s1,0)=risk1(s1,0)−risk0(s1,0)$$({s_1}) \equiv {\rm{CEP}}({s_1},0) = {\rm{ris}}{{\rm{k}}_1}({s_1},0) - {\rm{ris}}{{\rm{k}}_0}({s_1},0)$$, for the ZEST data with candidate surrogate S the log10$$_{10}$$ fold-rise of gpELISA antibody titers from baseline to week 6. The Weibull-estimated maximum likelihood method of Gabriel and Gilbert [6] was used, assuming a parametric normal model for S(1)$$S(1)$$ conditional on the BIP X and using the clinical endpoint Y=I[T≤t]$$Y = I[T \le t]$$ for t=$$t = $$2 years](/document/doi/10.1515/jci-2014-0007/asset/graphic/jci-2014-0007_figure2.gif)

Point and 95% confidence interval estimates of the CEP curve, CEP

We note that, as described in Huang and Gilbert [21] and Huang, Gilbert, and Wolfson [18], the employed statistical methods account for the case–cohort sampling design nested within a randomized trial in order to obtain unbiased estimators of

Figure 2 also highlights the interpretability of the CEP curve analysis, for example allowing researchers to infer that a fold rise in gpELISA antibody titers from baseline of 10-fold (titer difference = 1.0) corresponds to an estimated clinical efficacy of –0.033; under the no-harm monotonicity assumption, this can be interpreted as 3.3 of 100 vaccine recipients with

Several articles have discussed the limitation of the BIP-based methods for estimating the CEP surface that the modeling assumptions for

6 Discussion

We studied implications of the principal surrogate criteria ACN and one-sided strong ACS for the Prentice definition of a valid surrogate endpoint (i.e. Specificity and Sensitivity), and vice versa. We found that in general (for a general S, not in Case CB, and not assuming EECR or EHHM), these two types of criteria do not imply one other. We also found that Case CB together with EECR or ENHM do allow several implications, in particular EECR + Case CB + ACN imply Sensitivity and conversely EECR + Sensitivity imply ACN. Relaxing EECR to ENHM, however, loses the first implication, while the second implication still holds if Monotonicity is added. Apart from Case CB, the only implication that can be derived is that EECR + ACN imply Specificity if NNMEs or Monotonicity hold, and ENHM + ACN imply Specificity if NNMEs or Monotonicity hold. In the ZEST example EECR, Case CB, ACN, and 1-sided strong ACS are consistent with the observed data, illustrating how principal surrogate criteria can be used to help validate the Prentice definition. In addition, we found that Case CB for a binary candidate surrogate S allows more implications. In fact, in the special case EECR + Case CB, ACN + one-sided strong ACS hold if and only if the Prentice definition holds.

The following question arises – if the principal surrogate criteria are only useful for checking the Prentice definition in Case CB, of what value are the results? Previous authors (e.g. [6] and [29]) have noted that the Prentice [2] criteria cannot be checked in Case CB, because there is no variability of the biomarker in the placebo group. However, this article ignores the Prentice [2] criteria and goes straight to checking the Prentice definition, showing that in Case CB the principal surrogate criteria can be used to check part or all of the Prentice definition. This is useful in practice given that the Prentice definition of the treatment effect on the surrogate being concordant with the treatment effect on the clinical endpoint is a relevant property of a useful surrogate, allowing reliable predictions of clinical efficacy in the same setting of the trial based on the surrogate and guaranteeing a consistent surrogate. Additional research is needed for evaluating the reliability of biomarker endpoints for making inferences about clinical efficacy of new treatments in the same or similar setting (the bridging or transportability surrogate problem), in particular for studying whether and how the principal surrogate/strong effect modifier and/or Prentice surrogate frameworks are useful for this problem.

Funding statement: Funding: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services-National Institutes of Health R37AI054165.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R37AI054165. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix: proofs of results

We prove the results using one-sided Specificity and one-sided Sensitivity; the proofs are similar using two-sided Specificity and two-sided Sensitivity.

Proof of result 1

Examining eqs (1)–(4), it follows immediately that ACN implies line (1) equals zero, and EECR implies lines (3) and (4) are zero. Therefore under EECR + ACN

In general,

In addition, Case CB implies

Conversely, in Case CB

Now, Sensitivity means that

Next, we consider the conditions under which ACN + one-sided strong ACS imply Specificity. By one-sided strong ACS, CEP

is bounded above by zero. Therefore, under any of (i), (ii), or (iii), CE

Now, under Case CB

Proof of result 2

Under ENHM, line (3) is zero, and under ACN, line (1) is zero. Therefore, under ENHM + ACN

The condition

Conversely, assume Sensitivity, Monotonicity, and Case CB. In Case CB

Now, Sensitivity means that

Next, we determine the conditions under which ACN + one-sided strong ACS imply Specificity. As in the proof of Result 1, adding any of NNMEs, Monotonicity, or Case CB to ENHM + ACN, we obtain

By 1-sided strong ACS, CEP

Conversely, Sensitivity + Specificity together with NNMEs, Monotonicity, and Case CB do not imply one-sided ACS for any

Proof of result 3

Result 2 shows that under ENHM, ACN does not imply Sensitivity even under the four extra assumptions. Thus with ENHM relaxed, ACN also does not imply Sensitivity. Conversely, assume Sensitivity, Monotonicity, and Case CB. In Case CB

Now, as in the Proof of Result 2, by Sensitivity 0=CE=CEP

Next, we consider conditions under which ACN + 1-sided strong ACS imply Specificity. Adding any of NNMEs, Monotonicity, or Case CB to ENHM + ACN, we obtain

By one-sided strong ACS, CEP

Proof of result 1-Binary

Under EECR and Case CB,

The condition

Next, we also assume Specificity. Specificity (accounting for the fact that ACN holds) states that

Proof of result 4

With

Under Case-CB-

Next we show that EECR + ACN-

Next we note that EECR + ACN-

Lastly, the same results attain with EECR replaced with EECR-

References

1. GailM, PfeifferR, Van HouwelingenH, CarrollR. On meta-analytic assessment of surrogate outcomes. Biostatistics2000;1:231–46.10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.231Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. PrenticeR. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: definition and operational criteria. Stat Med1989;8:431–40.10.1002/sim.4780080407Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. FrangakisC, RubinD. Principal stratification in causal inference. Biometrics2002;58:21–9.10.1111/j.0006-341X.2002.00021.xSearch in Google Scholar

4. JoffeM, GreeneT. Related causal frameworks for surrogate outcomes. Biometrics2009;65:530–8.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01106.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

5. GilbertP, HudgensM. Evaluating candidate principal surrogate endpoints. Biometrics2008;64:1146–54.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01014.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. WolfsonJ, GilbertP. Statistical identifiability and the surrogate endpoint problem, with application to vaccine trials. Biometrics2010;66:1153–61. pMCID: PMC3597127.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01380.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. ZiglerC, BelinT. A Bayesian approach to improved estimation of causal effect predictiveness for a principal surrogate endpoint. Biometrics2012;68:922–32.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01736.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. TaylorJ, WangY, ThibautR. Counterfactual links to the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Biometrics2005;61:1102–11.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00380.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

9. LiY, TaylorJ, ElliottM. A Bayesian approach to surrogacy assessment using principal stratification in clinical trials. Biometrics2010;66:523–31.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01303.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. VanderWeeleT. Principal stratification – uses and limitations. Int J Biostat2011;7:Article 28. pMCID: PMC3154088.10.2202/1557-4679.1329Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. GilbertP, HudgensM, WolfsonJ. Commentary on “principal stratification – a goal or a tool?” by Judea Pearl. Int J Biostat2011b;7:Article 1.10.2202/1557-4679.1341Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. PearlJ, BareinboimE. Transportability of causal and statistical relations: a formal approach. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Menlo Park, CA, 247–254, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

13. ChenH, GengZ, JiaJ. Criteria for surrogate end points. J R Stat Soc Ser B2007;69:919–32.10.1111/j.1467-9868.2007.00617.xSearch in Google Scholar

14. JuC, GengZ. Criteria for surrogate end points based on causal distributions. J R Stat Soc Ser B2010;72:129–42.10.1111/j.1467-9868.2009.00729.xSearch in Google Scholar

15. VanderWeeleT. Surrogate measures and consistent surrogates. Biometrics2013;69:561–8.10.1111/biom.12071Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. HuangY, GilbertP, JanesH. Assessing treatment-selection markers using a potential outcomes framework. Biometrics2012;68:687–96. pMCID: PMC3417090.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01722.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. FollmannD. Augmented designs to assess immune response in vaccine trials. Biometrics2006;62:1161–9.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00569.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. HuangY, GilbertP, WolfsonJ. Design and estimation for evaluating principal surrogate markers in vaccine trials. Biometrics2013;69:301–9. pMCID: PMC3713795.10.1111/biom.12014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. JoffeM. Principal stratification and attribution prohibition: good ideas taken too far. Int J Biostat2011;8:Article 12. pMCID: PMC3204670.Search in Google Scholar

20. GabrielE, GilbertP. Evaluating principle surrogate endpoints with time-to-event data accounting for time-varying treatment efficacy. Biostatistics2014;15:251–65.10.1093/biostatistics/kxt055Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. HuangY, GilbertP. Comparing biomarkers as principal surrogate endpoints. Biometrics2011;67:1442–51.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01603.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. LongD, HudgensM. Sharpening bounds on principal effects with covariates. Biometrics2013;69:812–19.10.1111/biom.12103Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. QinL, GilbertPB, FollmannD, LiD. Assessing surrogate endpoints in vaccine trials with case-cohort sampling and the Cox model. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2008;2(1):386–407. PMCID: 2601643.10.1214/07-AOAS132Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. FlemingT, DeMetsD. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: are we being misled?Ann Intern Med1996;125:605–13.10.7326/0003-4819-125-7-199610010-00011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. SchmaderKE, LevinMJ, GnannJW, McNeilSA, VesikariT, BettsRF, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of herpes zoster vaccine in persons aged 50–59 years. Clin Infect Dis2012;54:922–8.10.1016/j.ymed.2012.08.012Search in Google Scholar

26. MiaoC, LiX, GilbertP, ChanI. A multiple imputation approach for surrogate marker evaluation in the principal stratification causal inference framework. In: risk assessment and evaluation of predictions. New York: Springer, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

27. PrenticeR. A case-cohort design for epidemiologic cohort studies and disease prevention trials. Biometrika1986;73:1–11.10.1093/biomet/73.1.1Search in Google Scholar

28. GilbertP, GroveD, GabrielE, HuangY, GrayG, HammerS, et al. A sequential phase 2b trial design for evaluating vaccine efficacy and immune correlates for multiple HIV vaccine regimens. Stat Commun Infect Dis2011a;3:Article 4. pMCID: PMC3502884.10.2202/1948-4690.1037Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. ChanI, ShuL, MatthewsH, ChanC, VesseyR, SadoffJ, et al. Use of statistical models for evaluating antibody response as a correlate of protection against varicella. Stat Med2002;21:3411–30.10.1002/sim.1268Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Balancing Score Adjusted Targeted Minimum Loss-based Estimation

- Surrogate Endpoint Evaluation: Principal Stratification Criteria and the Prentice Definition

- A Causal Perspective on OSIM2 Data Generation, with Implications for Simulation Study Design and Interpretation

- Parameter Identifiability of Discrete Bayesian Networks with Hidden Variables

- The Bayesian Causal Effect Estimation Algorithm

- Propensity Score Analysis with Survey Weighted Data

- Comment

- Reply to Professor Pearl’s Comment

- M-bias, Butterfly Bias, and Butterfly Bias with Correlated Causes – A Comment on Ding and Miratrix (2015)

- Causal, Casual and Curious

- Generalizing Experimental Findings

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Targeted Learning of the Mean Outcome under an Optimal Dynamic Treatment Rule [J Causal Inference DOI: 10.1515/jci-2013-0022]

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Balancing Score Adjusted Targeted Minimum Loss-based Estimation

- Surrogate Endpoint Evaluation: Principal Stratification Criteria and the Prentice Definition

- A Causal Perspective on OSIM2 Data Generation, with Implications for Simulation Study Design and Interpretation

- Parameter Identifiability of Discrete Bayesian Networks with Hidden Variables

- The Bayesian Causal Effect Estimation Algorithm

- Propensity Score Analysis with Survey Weighted Data

- Comment

- Reply to Professor Pearl’s Comment

- M-bias, Butterfly Bias, and Butterfly Bias with Correlated Causes – A Comment on Ding and Miratrix (2015)

- Causal, Casual and Curious

- Generalizing Experimental Findings

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Targeted Learning of the Mean Outcome under an Optimal Dynamic Treatment Rule [J Causal Inference DOI: 10.1515/jci-2013-0022]