Abstract

After the Cultural Revolution, a period marked by a global retreat from radical politics and increased compromises, filmmakers in the Hong Kong leftist film industry faced financial challenges stemming from the studio’s struggles during the Cultural Revolution. Despite these difficulties, they ingeniously incorporated generic elements to captivate audiences, using popular genres as conduits for social commentary. The Stranger by Feng Huang Motion Picture company stands out, as director Bao Fang adeptly appropriated science fiction elements to adapt a real story of espionage in Hong Kong. The film signifies Bao’s transition from opera film and historical pictures to negotiating realist and science-fictional elements to convey social innuendo. Drawing inspiration from recent works by Mingwei Song and Seo-young Chu, my argument extends to explore how sci-fi serves as a mode of expression for geopolitical commentary. The film not only expresses concern over Soviet espionage but also reflects the fear over the collapse of grand narratives such as Enlightenment and Revolution.

In the late 1970s, a global retreat from radical politics witnessed a wave of compromises and negotiations. Within the context of Hong Kong’s film studios, leftist filmmakers grappled with the financial difficulties borne out of the studios’ struggles during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). In response to this predicament, they strategically incorporated generic elements with the aim of captivating audiences. Despite these challenges, the leftist filmmakers did not capitulate; instead, they ingeniously found interstices in popular genres as conduits for social commentary. The film The Stranger (怪客, 1979), produced by Feng Huang Motion Picture Company (鳳凰影業公司) and directed by Bao Fang 鮑方 (1922–2006),[1] presents an intriguing case. In Hong Kong, leftist film studios produced film such as period costume dramas, opera films, and martial arts pictures. Their films oppose authoritarianism, arranged marriage, imperialism, and superstition, while advocating feminism, collective justice, and working-class solidarity.

Bao, previously an actor and disciple under Zhu Shilian 朱石麟 (1899–1967), assumed the role of director in the early 1960s, primarily concentrating on period costume and historical pictures such as The Adventures of “I have Come” (我來也, 1966), The Painted Skin (畫皮, 1966), and Chu Yuan (屈原, 1973). The Stranger stands out as a rare case, where Bao adeptly appropriated popular science fiction (sf) elements to situate the narrative in contemporary Hong Kong. The storyline revolves around the harassment of a scientist and his family by a team of espionage agents, who resort to murder to obtain the scientist’s latest discovery for sale to the Soviet Union, intending to launch bacterial warfare.

The Stranger performed poorly at the box office, grossing less than 150,000 Hong Kong dollars.[2] The film looks like a spinoff from a series of thriller, spy-fi, and sf productions shown in Hong Kong during that period, such as Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounter of the Third Kind (1977), Lewis Gilbert’s Moonraker (1979), and Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). The latter two were screened simultaneously with The Stranger. While the film does not feature robots, flying cars, or extraterrestrial life, it incorporates striking cinematic techniques, including car races, sudden zoom-ins, suspenseful atmospheres, exotic Thai locales, and a female spy who wears a human mask. Despite its disappointing box office reception, Bao includes the full screenplay in his memoir alongside his famous work The Painted Skin. He says,

The motivation behind making this film stems from the infiltration of spies by a global superpower, particularly the espionage activities in Southeast Asia. I intended to voice my protest and convey my discontent. Due to constraints surrounding international distribution, the film was not allowed to overtly criticize these matters. It can only be expressed indirectly and covertly by making innuendos. Ultimately, it became an engaging and suspenseful film. Throughout my film career, a film imbued with such a distinct filmic style stands as a singular exemplar. Including its reprint in this publication serves as a commemoration. (Bao 1999, 268; my emphases)

During the Cultural Revolution, Bao produced revolutionary operas and radical films such as The Battle of Sha Chia Bund (沙家浜殲敵記, 1968) and The Collegiate (大學生, 1970). The former is an adaptation of one of the eight “model plays” in mainland China, while the latter explores the transformation of college students through rural education. However, his reputation faced jeopardy upon the release of Chu Yuan. The selection of Qu Yuan’s story was seen as entwined with the struggle between Confucianism and Legalism in the mainland and making sly innuendos against the Gang of Four. The film was halted in 1973, but it was re-released and was well received in 1977, the same year Bao started writing the script for The Stranger.

Released after the Cultural Revolution, The Stranger manifested significant changes in Bao’s directorial style and thematic orientation. The film transcends the confines of period costume and historical portrayals, adopting a transnational perspective to explore espionage in both contemporary Hong Kong and Thailand. In the film, Bao extols the virtue of enlightenment, emphasizes the importance of truth, and highlights the ethical obligations of a scientist safeguarding the invaluable virus X-II, which could be exploited in bacteriological warfare. However, he also underscores skepticism toward enlightenment. This skepticism is highlighted by his failure to unfold the mystery surrounding his daughter’s murder and his inability to protect his family. The scientist emerges as a symbol of enlightenment and humanism, exemplified by his reluctance to commercialize his discovery. However, his humanistic stance proves insufficient in comprehending the estranging realities of the Cold War. More importantly, Bao’s transition from a director specializing in period costume and historical genres to one negotiating both realist and sf elements to convey innuendos reflects how Bao and his leftist contemporaries in Hong Kong viewed the agency of human being and realist aesthetics during the post-Cultural Revolution.

In this paper, I argue that The Stranger is science-fictional, and that Bao turns to sf as a mode of expression to convey his geopolitical commentary within the post-Cultural Revolution political and artistic landscapes. He not only criticizes Soviet espionage in Hong Kong but also registers hesitations toward the enlightenment project. The innuendo may not only point at the Soviet espionage only but also the Cultural Revolution or the grand narrative of truth-claiming. This argument draws inspiration from recent works by Mingwei Song and Seo-Young Chu. According to Song, sf functions as a form of truth-claiming storytelling, particularly evident in recent Chinese sf writers’ engagement with unfolding “truths and shedding light on the invisible depth of contemporary Chinese reality” (Song 2023, 7). This genre, Song argues, signals a departure from China’s conventional mimetic realism. He contends that Chinese sf represents “both the visible appearance and invisible depths of reality, both phenomena and noumena” (21). In other words, science fiction deviates from the traditional path of mimetic realism, disrupting perceptions of reality and challenging the conventions of mimetic realism (16).

Apparently, The Stranger fits into Song’s characterization of sf, as it reflects on enlightenment ideals. However, it does not challenge the separation from realism. The narrative of The Stranger is situated in contemporary Hong Kong and is based on a real espionage event. Chu, however, presents a challenge to this separation. She provides a radical definition of science fiction that the dialectic between the real and the estrangement lies “not in the formal apparatus but in the object or phenomenon that the SF text seeks accurately to represent” (Chu 2010, 5). This implies that realist works and sf are not mutually exclusive but rather correspond to different levels of mimesis intensity necessary for rendering their referents available for representation (9). While realism designates low-intensity mimesis, science fiction designates high-intensity mimesis.

I agree with Chu’s definition of sf, but there are different modes of expressing the intensity of mimesis. Therefore, it is necessary to elaborate further into the local context, examining the intersection of the categories of Hong Kong, leftist, and sf to elucidate the nuances of representational intensity. The positioning of these three elements – Hong Kong, sf, and leftist – is notably marginal. Situated between China and Taiwan, Hong Kong may be small in size and population, but it plays a key role in geopolitical strategy. Comparatively, Hong Kong’s cinematic landscape featured a preponderance of commercial genres encompassing romance, fantasy, period costume dramas, martial arts films, and melodramas.

Despite this cinematic diversity, the film genre of sf did not achieve significant popularity in Hong Kong. Scholars such as Tom Cunliffe argue that the lack of sf films in Hong Kong can be attributed to the resistance of the local tradition to the realm of science (Cunliffe 2021). However, various sf elements, including flying saucers, robots, and aliens, were found in opera films, folklore, and fantasy martial arts film productions. The representational intensity in this context aimed to capture objects of wonder and maximize their spectacular effects, a representational level I call the mode of spectacle. The intensity of mimesis in this mode of spectacle is for making cinematic effect or visualizing estrangement. However, there is a mode of expression that filmmakers discover the estrangement within everyday life, transforming it into a site of innuendo. Viewed from this perspective, the leftist intervention of sf emerges as a distinct mode of expression, using the high-intensity mimesis of sf to connect real espionage to the potential threat of bacterial warfare. This intervention is characterized by its capacity to convey social commentary through the lens of sf, thereby distinguishing it from making it as mere cinematic spectacle. In short, the intersection of Hong Kong, leftist, and sf occupies a marginal position; nevertheless, leftist directors such as Bao adeptly leverage this marginality as a platform for expression.

To understand how Bao uses this mode of expression, whose attributes – horror, mystery, estrangement, and geopolitical phenomenon – can be registered as commentary, I elaborate on the modes of spectacle and expression in the following section. This include a brief introduction to Hong Kong sf. Followed by that, I focus on Bao’s adept navigation of cinematic styles, drawing inspiration from a real espionage case in Hong Kong for film adaptation. The analysis will also illustrate how Bao develops the concept of strangeness to comment on the geopolitical situation and reflects on the failure of the virtue of enlightenment as portrayed in The Stranger.

1 Brief History of Hong Kong Science Fiction Films

Examining the presence of sf culture within Hong Kong’s cultural landscape reveals a foundation richer than commonly perceived. While sf films did not claim the forefront of cinematic genres in Hong Kong, it is notable that screenings of Hollywood, Japanese, and the Soviet Union’s sf productions were prevalent. Films such as Ishiro Honda’s 本多 猪四郎 The Mysterians (地球防衛軍, 1957), Godzilla Strikes Again (恐龍之子, 1955), and The H-Man (氫彈怪物, 1958), and Koji Shima’s 島 耕二 Warning from Space (宇宙人, 1956), among others, were dubbed in Cantonese and screened in Hong Kong.[3] Additionally, in the late 1950s, the leftist distribution company Southern Film Company distributed Soviet sf productions in Hong Kong such as Pavel Klushantsev’s Road to the Stars (星際旅行, 1958), Mikhail Karyukov’s Battle Beyond the Sun (飛入太空, 1959), and Aleksandr Ptushko’s Sampo (跨海伏魔, 1959). Some of the Japanese sf films aroused concerns among film critics. For example, Ye Qin, after watching The H-man, emphasized the responsible utilization of scientific works and technology to avoid potential human annihilation and nuclear warfare (Ye 1959).

Moreover, during the 1950s translated sf picture books were sold by Zenith Publishing, featuring titles such as Adventure in the Moon (月宮探險), New World after a Thousand Years (一千年之後的世界), and Manmade Sun (人造太陽). Writers such as Zhao Zifan 趙滋蕃 (1924–1986) and Yang Zijiang 楊子江 produced sf stories in Hong Kong like Flying Saucers Conquering the Space (飛碟征空, 1956), Adventure in the Space (太空歷險記, 1956), and Number 001 The Mystery of Sirius A (天狼A-001號之謎, 1960), respectively.[4] In the 1960s, Ni Kuang (倪匡, 1935–2022) wrote the famous long-running Wisely series, comprising over 150 sf adventures that explored themes ranging from mysterious aliens to humanity’s vulnerable destiny in the face of extraterrestrial civilizations. He also wrote the script for the Shaw Brothers studio sf film The Super Inframan (中國超人, 1975), cashing in on the popularity of the Kamen Rider Series in 1970s Hong Kong. Despite his prolific output, only a few of his sf works found film adaptation by the mid-1980s.

Numerous sf elements can be discerned in early Hong Kong film genres such as martial arts, opera, and folklore.[5] Illustrative examples include the depiction of a flying saucer in Ng Wui’s 吳回 folkloric work The Giant Gourd (大冬瓜, 1958), a rocket ride in Fung Chi-Kong’s 馮志剛 opera film Magic Head of the Princess’ Battle with the Flying Dragon (飛頭公主雷電鬥飛龍, 1960), and a robot monster in Ling Yun’s 凌雲martial arts fantasy Buddha’s Palm Part II (如來神掌, 1964). Questions that arise include whether these works are sf, wherein lies the boundary between sf and other genres, and how can we interpret these sci-elements? While I agree with Chu’s argument that “the differences among various types of SF correspond to the various types of cognitively estranging referents that require high intensity representation” (Chu, 9), it is essential to acknowledge that within the various types of cognitively estranging referents, there are different methods for rendering referents available for representation.

The terms mode of spectacle and mode of expression introduced here are not mutually exclusive, but they render estrangement differently and serve different functions within Hong Kong film industry. First, the mode of spectacle shows technological marvels, such as flying saucers, palm rays, and teleportation. These technological advances are not available in ordinary life; therefore, they do not have direct correlations in real-life. Rather, these elements derive meaning solely within the context of the narrative. For instance, the inclusion of a pair of futuristic robots in Buddha Palm Part II or a colossal leg in The Furious Buddha’s Palm (如來神掌怒碎萬劍門, 1965) makes sense only within the martial arts film narrative, addressing audiences’ imagination, rooted in specific literary, cinematic, and social culture.

Second, most sf elements employed in this mode of spectacle focus on destructive technology and power. Many of these genres are set in ancient eras or abstract time and place, allowing for a pronounced emphasis on imagination (幻想) over science (科學). The imaginative elements represent advanced scientific technology or powerful destruction rather than scientific principles and rational thinking. The mode of spectacle articulates sf elements to visualize the imagination originating from martial arts or folklore narratives. For example, the translation of foreign sf film titles often featured characters like long 龍 (dragon), mo 魔 (devil), and xia 俠 (knight-errant), which are typical figures of rhetoric in martial arts fantasy films.[6] In local productions, using sf as mode of spectacle can be discerned in martial arts films. In Chien Lung’s 劍龍 The Female Chivalry (女飛俠, 1966) and The Female King Kong (女金剛, 1966),[7] subjects include UFOs, James Bond’s gadgets, laser guns, space stations, scientists, and spies. The hero identifies himself as Moonlight Man (月光俠), and after 6-year spaceship training, he becomes an intangible solid object in space (無形固體物), driven by personal vengeance against the gangsters who broke his family for their treasure. Third, the mode of spectacle may not necessarily align with Tom Gunning’s concept of the cinema of attraction. The giant leg or laser gun is part of the diegetic rendition of the magical and fantasy of sf element. Rather than breaking the fourth wall or addressing the audiences directly, the mode of spectacle aims at visualizing the existing generic imagination concerning destructive technological advances and physical power.

In the mode of expression, film auteurs use film text to ask questions such as “what if the world…,” deriving the meaning of sf elements from real-life referents. Therefore, the temporal and spatial dimensions in the mode of expression establish connections between the diegetic narrative and the real world. If sf intensity is confined only to the mode of spectacle, they are often critiqued for being “repetitive,” “childish,” and “nonsense” (Liu Wen-he 1964, 1965). Second, the mode of expression operates as a mode of address directed from the authors to the audiences, conveying messages explicitly rather than speaking to the audiences’ imagination. In contrast to the mode of spectacle where the message is often secondary, the grammar of the mode of expression resembles a conditional sentence in a present tense. By posing the question “What if the world…,” film auteurs provide their own answers. The “world” in this conditional sentence is tied to the technological, biomedical, or geopolitical crises, developments, or problems. Therefore, the innuendo Bao uses in his memoir uses sf elements to make an indirect commentary on geopolitical strangeness. Despite its indirect nature, viewers can connect the diegetic narrative to real-life espionage and the Cold War atmosphere. The grammatical structure of the mode of spectacle, on the other hand, resembles the literalization of hyperbole, showcasing an exaggerated narrative of destructive power beyond physical limitation.

The use of innuendo is a recurring practice among left-leaning directors, who delivered progressive lessons and emphasized the significance of science through imaginative elements such as horror, fantasy, and folklore.[8] Directors like Chun Kim秦劍 (1926–1969) used horror and fantasy as a site for educational discourse on science. His film The Nightly Cry of the Ghost (鬼夜哭, 1957) revolves around the practice of embracing scientific understanding or the supernatural (Tsang 2018:28). The film strategically inserts a nondiegetic sequence featuring a voiceover explaining poultry farming, accompanied by montages illustrating infrastructures. This sequence elucidates various aspects of chicken husbandry, dietary proportions, temperature regulation, and the timeline involved in hatching. The mode of expression is particularly evident in a rarely found sf film Life and Death (生死博鬥, 1977), directed by the leftist actor and director Fu Chi 傅奇(1929-) of the Great Wall Film Company (長城電影製片有限公司). Adapted from the American sf writer James Gunn’s novel The Immortal, the film revolves around a working-class young man in Hong Kong who selflessly donates blood to an old wealthy man. The young man’s blood possesses the ability to extend the old man’s life, bestowing perpetual youthfulness and eternal life. Fu employs the sf narrative as an allegory of capitalist society, representing how the capitalist class in Hong Kong exploits the labor of the working class in the late 1970s, a period when Hong Kong emerged as one of the four Asian tigers.

In short, the mode of expression articulates the sf narratives to engage with the contemporary world. The “what if the world…” question serves a site for director to make innuendo. Within this mode of expression, sf works as a vehicle for representing cognitively estranging moments intended for social commentary. Directors can elicit attention from audience members capable of connecting denotation and connotation, as well as narratives and real-life events. Therefore, the politics of address concern how film directors strategically deploy and navigate a variety of cinematic techniques and referents that add up to speak to a particular group of audiences. In this mode of expression, The Stranger poses the question, What if Soviet spies are everywhere in Hong Kong, and what if they are planning to sell a Hong Kong scientist’s discovery to the Soviet Union to launch bacterial warfare? To understand how Bao adapts real-life espionage, I now focus on the actual espionage event that happened in 1972. Additionally, I also illustrate how Bao uses filmic forms to portray the mysterious atmosphere in the adaptation (Figures 1–4).

The cover of a sf picture book New World after a Thousand Years (一千年之後的世界) published by Zenith Publishing in Hong Kong.

A list of sf picture books published by Zenith Publishing in Hong Kong.

Advertisement of Koji Shima’s Warning from Space (宇宙人, 1956) in Hong Kong.

Advertisement of Pavel Klushantsev’s Road to the Stars (星際旅行, 1959) in Hong Kong.

2 The He Hong’en Case and Film Adaptation

In the 1970s, Hong Kong witnessed numerous incidents involving Soviet espionage, such as the case of Amos Dawe and Ronald Hill.[9] The latter half of the 1970s also saw an expansion of Soviet influences in Southeast Asia, characterized by the deployment of merchant ships and fleets to Singapore, Malaysia, and Bangkok. More than 80 such vessels were recorded in Bangkok during the first 5 months of the year 1976.[10] Bao was furious about the Soviet’s intrusion in Southeast Asia, and a 1972 espionage case provided inspiration for The Stranger.

In August 1972, the Hong Kong Special Branch apprehended two Soviet crew members, Andrei Ivanovich Polikarov and Stepan Tsuanaev, along with He Hong’en 何鴻恩, a stateless Chinese individual. The Special Branch leveled spying charges against them, asserting that He, a 50-year-old export–import merchant, had been apprehended with intricate plans aimed at expanding a Soviet spy network across Southeast Asia. Subsequently, the two Soviet crewmen were repatriated on Soviet vessels shortly after their detention, while He was placed aboard the Kavalerovo, a Soviet ship en route to Vladivostok. He was deported in November 1972 after undergoing a 4-month negotiation and detention. This episode ignited a complex diplomatic and political imbroglio involving the PRC, the UK, Hong Kong, and the Soviet Union.

The mystery surrounding He’s background permeated news reports. In the news, he had defected to the Soviet Union in 1969 before he bought a big apartment in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong and hired a maid servant. Leading an ordinary life as a businessman, he frequented Happy Valley to see horse racing.[11] The narrative not only captured public attention but also provided a rich source of inspiration for literary and cinematic works. In The Stranger, Bao names the businessman-spy character Zhang Hong’en 張弘恩 after the historical figure by that name. Ruan Lang 阮朗 (1919–1981), a Hong Kong leftist writer, similarly took inspiration from this incident, incorporating it into the short story “Snake Teeth” (蛇牙).[12] First published in The Ocean Literary (海洋文藝) in June 1974, the story portrays a merchant-spy as a metaphorical snake tooth. The story’s protagonist talks directly about Soviet spies:

As my teacher told me, many countries have undertaken the task of “extracting” snake teeth – the Soviet spies. They exercise caution against the emergence of new “snake teeth,” much like the British did. For instance, in the previous year, a Soviet spy was apprehended in Hong Kong, resulting in the deportation of an individual named “He.” (Ruan 1980, 247)

The dubious identity and the mysterious background of spies captivated Bao. However, when considering a film adaptation, Bao recognized the studio’s financial constraints. These limitations precluded the production of a conventional spy film featuring extravagant spycraft, James Bond-style cars, and Bond’s iconic female characters. Instead, he strategically articulated sf elements to offer a critique of Soviet espionage. Unlike Western spy-fi genre, The Stranger eschews the inclusion of mad scientists, futuristic weaponry, and a spy protagonist. Rather, the central character in The Stranger is a hardworking scientist alongside his family. To serve the mode of expression, Bao’s choice of sf helps reduce fancy spycraft and action sequences while focusing greater elements of mystery and enigma – a successful technique previously employed by Bao in The Painted Skin. Below, I discuss the formal styles in the film as they are inseparable from his mode of expression.

Bao demonstrates a deliberate awareness of his filmic style and its attendant meanings. Following the positive reception of The Painted Skin in the mainland, Bao met Chen Yi, the Foreign Minister in Beijing during the mid-1960s. Chen commended the film for its artistic and educational merits, and despite Bao’s consideration of incorporating additional horror elements, Chen advised against it, cautioning him against creating “horror-ism” (恐怖主義) (Bao 1999, 184). The underlying meaning of these words is that spectacular effects should be grounded in realism and avoid serving “art for art’s sake.” Bao heeded these words and retained them in his creative approach. In The Stranger, Bao embraced a film style distinct from his previous works. The script of The Stranger comprised a greater number of scenes. While The Painted Skin has 47 scenes with long dialogue, The Stranger expands to 58 scenes, characterized by sporadic action and atmospheric description. Different from his previous works, which used continuity editing styles, Bao extensively employed elliptical editing to connect all these scenes. For example, during a scene when the wife celebrates her daughter’s birthday, the camera quickly zooms in on the daughter and her friends blowing out candles. During the zoom-in, a sudden cut shifts to a tracking medium-long shot, showing the wife’s cousin and his girlfriend, Jenny, walking outside the house. In the script, these two scenes are connected by the wife bidding farewell to her cousin and Jenny. The implementation of elliptical editing offers a disorienting and mysterious effect between the scenes. The dissonance between these scenes is accentuated by the presence of two contrasting moods. One scene portrays a happy birthday party within the confines of a mansion, while another unfolds in the backyard where Jenny refuses to talk much with the cousin. Later, it is revealed that Jenny becomes a mistress of Zhang, who exerts control over her every move.

The use of elliptical editing is supported by a strategic complementation of constructive editing. Few master shots are shown between scenes that contribute to the narrative disorientation and mystery. For instance, in a scene when the scientist and the wife grapple with sorrow following their daughter’s death, the sequence employs close-up shots and reverse shots, capturing the intensity of their argument and depression. The wife accuses the scientist of prioritizing his research over paternal responsibilities and says, “You only care about your research. You are not a good father!” Subsequently, a close-up shot shows her leaving the frame on the left. The shot is followed by an abrupt cut that transitions to a close-up shot of Zhang turning toward the camera and says, “There is nothing suspicious. The accident may be like this: she lost her rabbit and she went downstairs. She chased after the rabbit that went to your laboratory.” Then, a long shot shows Zhang offering an explanation to the grief-stricken scientist in his office. The application of abrupt cut and the constructive editing develops the scene through closer shots, deliberately minimizing the description of the environment. Characters in the film appear trapped within the frame without any open horizons, creating distinct sensory effect. This contrasts with Bao’s historical picture Chu Yuan, where many sequences are captured in static long shots, highlighting the symmetry of the court, the order of the palace, and the solemn sacrifice of the servant.

The use of long shot in The Stranger is more prevalent in the Thai location, particularly when the wife encounters David Wang, who is later revealed to be a spy dispatched by Zhang but operating under the guise of an Interpol agent. Both characters are depicted in long shots traveling to various Thai tourist spots. However, these long shots primarily serve the purpose of attracting an exotic gaze. Within the narrative framework, discontinuity editing assumes a dominant role, structurally introducing cliffhangers to heighten narrative suspense. In the preceding example, it is revealed that Zhang possesses knowledge of the truth surrounding the daughter’s murder. He orchestrates the theft of the scientist’s research report and jewelry through a female spy, who inadvertently causes the daughter’s death.

Bao did remember Chen Yi’s advice, and in The Stranger he minimized the horror effect and infused the narrative with a realist tone. In one scene where the wife searches for the key to the safe, the lights are abruptly turned off. A series of constructive editing unfolds, featuring a close-up shot of a pair of shoes behind a curtain, followed by a medium-long shot capturing the silhouette of an approaching figure. In a state of panic, the wife holds a gun and points it toward the perceived threat. Upon firing, she sees that her target appears to be Jenny, the cousin’s girlfriend. David Wang arrives to handle the situation and carries Jenny away. At the window, the wife sees that the supposed Jenny is actually a counterfeit and is engaging in conversation with David Wang. The imposter Jenny is revealed to be a spy wearing a human mask resembling Jenny.

In The Painted Skin, the climax occurs when the scholar sees a creepy monster painting a human skin, accompanied by Yue Lun’s 于粦 (1925–2017) suspenseful percussion music. The whole sequence depicts how the scholar is scared to pass out, and the monster wears its human skin and chase after him. In The Stranger, when the female spy tears off her human mask, the shot is so brief that it quickly zooms in on the fearful face of the wife. Instead, the climax shifts from the human mask to Wang’s dubious identity. Through more than half of the film, Wang appears to be a professional Interpol agent, exposing the eavesdropping devices in the scientist’s safe, uncovering a counterfeit telegram, and giving his guns to the wife. However, in the last 15 minutes, Wang reveals his true motive: collaborating with the female spy and Zhang to steal the scientific research report and conspire with the Soviet Union to launch a bacterial war. With low-key lighting, he holds a syringe and threatens the wife, “The bullets are fake, the plastic bomb is fake, and this knife is also a counterfeit. If I did not pretend to die, how would you open the safe yourself? This is the most valuable item, a bacterial weapon. You don’t know that, do you?”

The horror effects in this sf film do not revolve around spectacle but rather emphasize the dubious identities prevalent in espionage. As Mingwei Song observes, “SF opens our eyes to the fearful invisible” (Song 35). The film unsettles the comforting definition of reality and good people. It exposes the absurdities, fears, and pervasive distrust in everyday life during the Cold War. In the following section, I discuss Bao’s concept of “strangeness” (怪) in his works (Figures 5–9).

Real Jenny and her large portrait, hinting at the dual identity of the female spy.

The female spy tears off the face of Jenny in her car.

The female spy tears off the face of Jenny in her car.

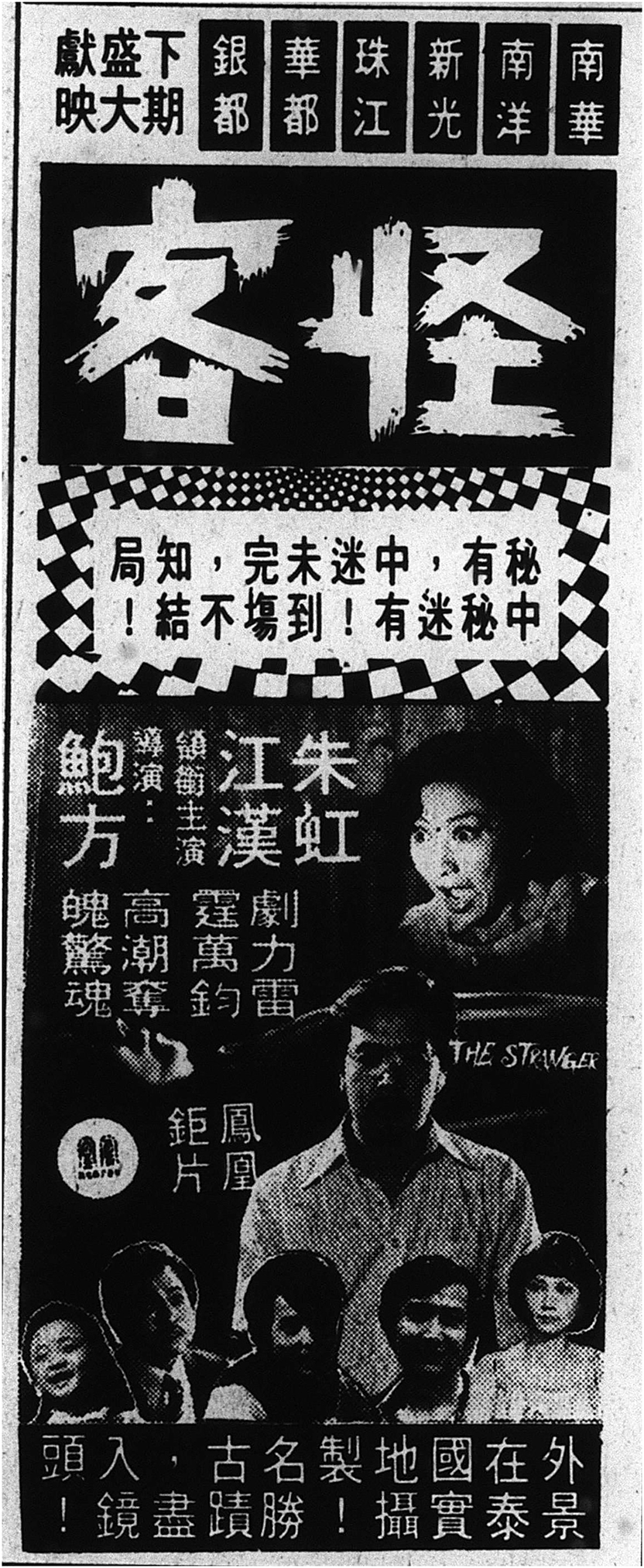

Advertisement of The Stranger in Ming Pao, dated September 10, 1979. The captions read: “Mystery within a mystery; another mystery within another mystery. Not until the ending, do you know the truth.”

Another advertisement for The Stranger in Ming Pao, dated September 13, 1979. The captions below read: “Location shoot at Thailand. Tourist sites all captured in our camera! Riding on elephants, playing with crocodiles, and swordplay!”

3 The World of Strangers

From a leftist perspective, a prevailing atmosphere of distrust and betrayal characterized the Cold War era. Historical events, such as the Sino-Soviet split in the mid-1950s, the Sino-Soviet border conflict on Zhenbao island in 1969, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the presence of Soviet naval units in the Indian Ocean in 1968, indicated that the Soviet Union had transformed into an imperialist power while maintaining a socialist façade. In the local context, the failure of the 1967 leftist riot in Hong Kong led many Hong Kong leftists to realize that their version of the Cultural Revolution lacked approval from mainland officials. Hong Kong leftists found themselves compelled to adhere to directives from the Red Guards in Guangdong. After the end of Cultural Revolution, a heightened sense of disillusionment and distrust toward the party and the revolutionary cause grew much stronger. Leftist filmmakers like Bao, who was genuinely patriotic, found themselves perturbed by the strange geopolitical changes, particularly the Soviet intervention in Hong Kong.

The concept of “strangeness” (guai 怪) in The Stranger assumes a pivotal role in understanding Bao’s mode of expression and critiques. The thematic underpinning of strangeness, while prominent in this work, is not new within his oeuvre. His concept of strangeness underscores an upside-down society, providing a site for articulating collective grievances. This motif finds earlier expression in his martial arts film The Adventures of “I-have-come” (1966). Bao introduces this concept in the film’s opening scene to critique the disorderly state of the world. The hero sings,

It is so strange. People light lanterns in the glow of daylight. In this world, oddities unfurl, as strange as they can be. A rooster lays eggs, fruits blossom from stones; sailing upon lands, streams ascending mountains. Cows dine on rice, humans chew on grass. Heaven and earth inverted. Miserable lives endured by people far and wide.

It is so strange. Once humans whipped a dog; now, dogs inflict the pain. The wolf now wears the crown; a tiger on a throne of gold. The common people (baixing 百姓) suffer; lackeys wear their grins. All crows under the sun are black. No outlet for their bitterness.

This concept of strangeness does not seek to provide abstract commentary, but instead carries a deeper significance. It serves as a lens through which the strangeness in the world impacts common people, particularly the baixing, a term often employed by leftist filmmakers in Hong Kong to allude to the proletariat and workers. Given the colonial censorship of films, what made the mode of address leftist was not their adherence to revolutionary realism or socialist realism, the recitation of Maoist slogans, or the display of Mao’s portraits. Instead, it was their forms and thematic concerns targeting to the baixing. The mode of expression adopted by leftists in Hong Kong was accessible and pedagogical.

For example, in The Painted Skin, Bao adapts Pu Songling’s strange story into a family melodrama, while at the same time highlighting the antisuperstition theme. Different from the original narrative, the female ghost does not actively seduce the young scholar. Instead, motivated by his desire to exploit the female ghost’s claim that her rich family can assist him in the civil examination, the young scholar approaches her. His downfall is not merely due his sexual desire but also his superstitious belief in God, luck, and appearance. At the end of the film, actor Jiang Ming 姜明 (1910–1990), playing the author Pu Songling, concludes, “Well, we have never seen a ghost. But there are people around us who behave like ‘ghosts.’ They fool people with their good looks. Careless ones will be devoured by them. Keep alert to keep away from them.” Bao’s concept of strangeness is part of the Chinese enlightenment project, aiming to shed light on the invisible depth of society and human nature. Themes like antisuperstition seek to get rid of strange appearances and probe into the essence of society.

In The Stranger, strange appearances gain an additional layer, manifesting as a geopolitical strangeness. This manifestation refers not only to the Soviet espionage but also to the socio-political atmosphere cultivated within society. This strange atmosphere builds a network of distrust among the characters. The film features seven main characters, where the scientist, the scientist’s wife, the cousin, and his girlfriend Jenny are presented as protagonists, while Zhang, the female spy, and David Wang are antagonists. For instance, Zhang forces Jenny’s father into bankruptcy, compelling Jenny to become his mistress. Because of that, Jenny loses contact with the cousin and becomes mysterious when they have a reunion. In an attempt to sell the scientist’s latest virus research to the Soviets, Zhang dispatches a female spy to steal the report. After an initial failure, he instructs the female spy to wear a human mask resembling Jenny to accomplish the theft. Additionally, he sends thugs to blind the cousin. Simultaneously, the female spy tries to disrupt the scientist’s marriage by capturing incriminating photos of the drunk scientist. Meanwhile, Zhang dispatches David Wang to meet with the scientist’s wife in Thailand and sends a telegram to the scientist to tarnish the wife’s reputation. Because of the telegram, the scientist begins to distrust his wife.

What is interesting is that all the villains adopt a façade of virtue. Zhang, an old classmate of the scientist, seeks to gain the scientist’s trust by claiming he obtained the compromising photos before their publication. Disguised as an Interpol agent, David Wang not only assists the scientist’s wife in killing a snake and accompanies her on the Thai tour but also helps expose the telegram and the eavesdropping device planted by the female spy. After the device is exposed, everyone begins to distrust Jenny and believe in David Wang. Even when the real Jenny arrives, the cousin and the wife struggle to believe her. Zhang goes so far as to make a fake call to the scientist’s wife, imitating the scientist’s voice. In this call, he warns the wife to be cautious of the cousin as he is part of the espionage. This fabricated warning induces panic and anxiety in the wife, convincing her that the cousin – who is knocking on her door to acquire a gun with which to rescue the real Jenny – intends to harm her. Within this network of distrust, no individual is immune from suspicion.

The identity of the Russian characters remains shrouded in secrecy throughout the film. The representations of Russians in the film elude a definitive geographical categorization. In Bao’s original script, the Russian characters converse in their native language, accented with Northeastern Chinese dialect. However, in the film, they speak multiple languages. For instance, a Russian issues David Wang commands in English while in Thailand. However, when a Russian sniper terminates Wang on a cargo ship, they use Russian. This linguistic multiplicity serves to reinforce the elusive nature of their origin and intentions, thereby contributing to the strange atmosphere of intrigue and enigma that pervades society.

The condition of the world of strangers extends beyond the consequences of modernity. Rather than constituting an existential crisis or alienation in modern society, the world of strangers in The Strangers particularly situates the problem within a geopolitical Cold War framework. The work is the only leftist film in Hong Kong that openly criticizes, albeit indirectly, the Soviet Union. Comparing this film to Lung Kong’s sf film Laugh In (哈哈笑, 1976) will help us understand Bao’s intervention.

Laugh In was produced by the rightist film company Eng Wah and Co. HK. In this film, the angel-like alien promotes abstract love and peace while critically assessing social issues in Hong Kong, such as media industry exploitation, police ineffectiveness, and pervasive corruption within society. Lung Kong was influenced by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, and he makes the alien’s journey similar to that of the Little Prince. The alien, played by Chen Chen 甄珍(1948-), understands the secular world with a childlike perspective. The alien embodies an external perspective, serving as a critique of the moral decay in Hong Kong. Her message of selflessness to children is like a Christian moral tale, offering a critique of modern ways of life. The angel-like perspective provides an abstract notion of peace and love, directed solely at the human nature and spiritual transformation. On the contrary, in The Stranger, everyone is caught up in a web of distrust with geopolitical implications. The only ones who occupy the external position are the Russians. In spatial terms, they are on the cargo ship, overseeing the pursuits and escapes of David and others in the street below. They pose an external threat to Hong Kong. However, if the scientist, who represents truth-claiming, is also engulfed in this network of distrust and confusion, the question arises: where can we find enlightenment (Figure 10)?

Russians on a cargo ship, surveilling David Wang in the street below with binoculars.

4 Failure of Enlightenment

Compared to Bao’s previous works, The Stranger features an unusual conclusion. Typically, Bao’s films end with a happy ending; young heroes celebrate the virtues of righteousness, antifeudalism, and antisuperstition. This follows the May Fourth convention that youth symbolize novelty, hope, and the nation’s future. However, in this film, the scientist’s daughter meets a tragic demise. Following the death of David Wang and the repatriation of Zhang, the scientist and his family find solace in saving the scientist’s research from the Russians. However, the film ends with a voiceover, by Bao himself, revealing the scientist’s ignorance regarding his daughter’s murder: “Our protagonists are now laughing happily. However, never do they know the secret that their beloved Lan Lan met a brutal end.” The final montage, featuring a family photograph and flashbacks of Lan Lan playing in a playground, leaves an ambivalent closure to the film. The death of Lan Lan and the revelatory voiceover highlight the failure of the scientist, an intellectual who cannot protect his family from mysterious geopolitical forces. I argue that the suspicion of the Enlightenment ideals and their grand narratives is intricately related to Bao’s experiences during the Cultural Revolution. Bao used the sf intensity of mimesis to convey his commentary on the Soviet espionage, as well as grand narratives such as Enlightenment, Humanity, and Revolution in the post-Cultural Revolution era.

Two factors significantly contributed to Bao’s hesitation toward the Cultural Revolution. First, the death of his mentor Zhu Shilin left an indelible impact. Zhu, deemed unpatriotic in the 1950s due to his film Sorrows of the Forbidden City (清宮秘史, 1948), faced criticism again during the start of the Cultural Revolution. Yao Wenyuan 姚文元(1931–2005), a member of the Gang of Four, denounced the film in the newspaper, quoting Mao to further label both the film and Zhu as unpatriotic, ultimately leading to Zhu’s demise from a hemorrhagic stroke. Another pivotal event contributing to Bao’s apprehension was the making of his historical picture Chu Yuan. Reflecting on this film, he observed, “Shooting Chu Yuan was the most painful period of my life” (Ho 2001, 101). The difficulty stemmed from the lessons learned from banned historical films like Sorrows of the Forbidden City and Sun Yu’s The Life of Wu Xun (武訓傳, 1950), making it challenging for leftist filmmakers to venture into historical portrayal.

Inspired by Mao’s gesture of gifting Songs of Chu (楚辭), written by Qu Yuan during the Warring State period (441BC – 221BC), to Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka as a symbol of normalizing Sino-Japanese relations, Bao aimed to seize the opportunity to celebrate patriotism of Qu Yuan. After extensive research on the works of Guo Moruo 郭沫若 (1892–1978) and related historical documents, Bao completed the first draft of the filmscript. However, reviewers criticized it for conflicting with the current mainland campaign. The draft depicted the Chu state resisting the Qin state, while in the mainland, the Qin state was portrayed as a progressive force that established the first unified China. After six revisions, Bao finalized the draft, recruited cast members, made costumes and props, and directed the film. Upon the film’s release in 1973, it faced an abrupt halt. Later, Bao discovered that the writer James Wong 黃霑 (1941–2004) had written an article suggesting that the characters in the film were allegorical references to the Gang of Four, causing concerns within the film company.

Upon reflection, Bao concluded that the stringent directives imposed by the Red Guards from the mainland on Hong Kong resulted in films that were estranged from ordinary people,

Zhu Feng made a film about women workers standing up to exploitation. We made it with passion. One day in a bus, some women workers recognized me. I asked them what they thought about the film. At first, they didn’t want to speak, then one said: “The goal of your film is difficult to realize. If we strike because of 20 cents, how could we make a living?” Well said. We were fighting for the people but we had lost touch of the people. She also said: “We know you mean well, but you’re not practical.” It made me cry. The Cultural Revolution went too far left. (Ho 2001, 115–16)

The scientist’s self-blame in the film mirrors Bao’s contemplation about his career and film productions. The Stranger poses the question of the role of intellectuals in a changing world and explores the space for their navigation in the current political and artistic landscapes. In the film, the representation of scientists has shifted from being perceived as infallible to fallible. There is an element that exceeds the scientist’s sphere of control, leading to failure in his judgment. On two occasions, the scientist erroneously thinks a murder’s disturbance is caused by a cat’s movement. He makes mistakes and faces situations beyond his control, showing the limitation of his influence. However, what he can control is his scientific research and the development of the serum.

During the Cultural Revolution, Bao directed The Collegiate, offering a different perspective on intellectuals. The film critiques the enslaving nature of colonial education and its impact on youth fixated solely on material wealth. A law student is disappointed by the corrupted legal system and American imperialism, so she undergoes a process of transformation (gaizao 改造) by joining peasants in rural education. In The Stranger, the scientist remains immobile, distancing himself not only from the outside world but also from the working-class masses, thus unable to transform himself. His political stance leans toward humanism than the proletariat’s class. Rejecting Zhang’s invitation to exploit the virus for commercial purposes, the scientist raises a query:

I’ve discovered this virus that can be used as an aggressive bacterial weapon. The serum I’ve invented can favor those who would use it freely. Please, answer me this: as a scientist, who stands with humanity, can’t I consider this invitation carefully? (My emphasis)

For Bao, the essence of humanity is elucidated in his earlier work Chu Yuan. He assumes the role of Qu Yuan and articulates through Qu Yuan’s poem “Ode to an Orange” (橘頌), and replies,

Yes, human beings can make it. It all depends on the person (事在人為). In this age of great turbulences, it is not easy to be a noble man. We must learn the spirit of the orange trees. Upheld righteousness, disassociate from dirty currents. Live an honorable life and die an honorable death.

Qu Yuan in the film opposes the slavery system, advocates for political reform, and questions the ruling class. Human agency is based on independent will, transcending obstacles, and advancing toward enlightenment. However, in The Stranger, the idea of humanism proves inadequate to save the scientist’s daughter. Incapable of securing his family, he shoulders self-blame, aggravated by his wife’s reproach regarding his paternal role. He is responsible for his daughter’s murder. The daughter is often portrayed playing with rabbits, which are used in the scientist’s experiment, metaphorically aligning her fate with that of experimental subjects. Unlike other characters who traverse various locations, the scientist remains confined to his home that has been transformed into a workplace. This spatial and visual immobility detaches him from the working-masses, who are noticeably excluded from the film, except for a servant in the scientist’s house.

Most importantly, the scientist fails to safeguard his research report. By chance, the cousin replaces the real report with a counterfeit one before David Wang attempted to steal it. The scientist’s impotence signifies the failure to transform the petty-bourgeoisie and unveil the concealed truth. Grand narratives of Humanity, Enlightenment, or Revolution became feeble against geopolitical currents. The collapse of the grand narratives, I argue, is the second layer of the fear and anxiety inherent in this sf film. The concluding voice over by Bao reveals his innermost thoughts and fears that persist after the Cultural Revolution.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, I follow Mingwei Song’s and Seo-young Chu’s works to take science fiction as a mode for rendering estranging phenomenon and narrative cognitively. Instead of seeing sf as separate from realism, I argue that after the Cultural Revolution, Bao used sf elements as a mode of expression in his film The Stranger to comment on Soviet espionage on one hand, and the failure of enlightenment on the other. Despite its poor box office result, it stands as the only feature film produced by the leftist film company in Hong Kong that criticizes the Soviet Union.

During the late Cold War, the political orientation of leftist film companies and their production underwent significant changes. Due to a severe financial deficit, Feng Huang merged with two other major leftist studios, Great Wall and Sun Luen, and became Sil Metropole in 1982. In light of these circumstances, after completing his final film Love with the Ghost in Lushan (嶗山鬼戀, 1984), Bao acknowledged the changing geopolitics and opted for retirement. He even abandoned the idea of making a film about Puyi, the last Chinese emperor.[13] With respect to the filming of The Last Emperor, Bao observes that “the Mainland leadership was against it because China had just established relationships with Japan. We couldn’t make a Puyi film without talking about the Japanese, and we’d come across as ungracious. Then we have no ways to shoot it. At the end, the same subject was undertaken by someone else (Bernardo Bertolucci)” (Ho 2001, 102). Bao’s disagreement with the studio’s leadership on various policies also led to his retirement in 1983.

Meanwhile, during the rise of the Hong Kong New Wave, sf films gained recognition in Hong Kong. Films like Tsui Hark’s 徐克 Zu The Warriors from the Magic Mountain (蜀山傳, 1983) and Alex Cheung’s 章國明 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star (星際鈍胎, 1983) showcased Hong Kong’s engagement with the genre in a new way. The former employed production teams associated with Star Wars (1977), contributing to their visual effects and scenes, while the latter parodied themes of alien abduction and UFOs. In mainland China, a wave of sf writers emerged such as Ye Ronglei 葉永烈 (1940–2020), Zheng Wenguang 鄭文光 (1929–2003), Xiao Jianheng 肖建亨 (1930-), and Tong Enzheng 童恩正 (1935–1997). They ignited a heated debate about the role of science and science education in sf genre (Jiang 2022, 130). During this period, several sf films were produced in China, including Zhang Hongmei’s 張鴻眉 Death-Ray on the Coral Island (珊瑚島上的死光, 1980), Huang Jianxin’s 黃建新 Dislocation (錯位, 1986), and Song Chong’s 宋崇 Wonder Boy (霹靂貝貝, 1988). Meanwhile, The Stranger faded from the Hong Kong scene and was brought to China, eventually airing on TV channels without gaining significant recognition in film history.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Wentao Ma for inviting me to give a talk on the early draft of this topic at UCSD. I also appreciate the insightful comments from Carlos Rojas and the two anonymous reviewers. Their feedback helped me restructure and clarify the main points of this paper.

References

Bao, Fang 鮑方. 1999. Hulu li mai shenme yao 葫蘆裡賣甚麼藥? [What is the medicine in the gourd?]. Beijing: Xiandai chubanshe.Suche in Google Scholar

Chu, Seo-young. 2010. Do Metaphors Dream of Literal Sleep? A Science-Fictional Theory of Representation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674059221Suche in Google Scholar

CUHK, Department of Extramural Studies at, and TV Department at RTHK 香港中文大學校外進修部, 香港電台電視部. 1985. Diangguang huanying – Dianying yanjiu wenji 電光幻影 – 電影研究文集 [Electric light and illusional shadow – An anthology of cinema studies]. Hong Kong: “Department of Extramural Studies at CUHK” and “TV Department at RTHK.”Suche in Google Scholar

Cunliffe, Tom. 2021. “Tracing the Science Fiction Genre in Hong Kong Cinema.” In Sino-Enchantment: The Fantastic in Contemporary Chinese Cinemas, edited by Kenneth Chan, and Andrew Stuckey, 128–48. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.3366/edinburgh/9781474460842.003.0007Suche in Google Scholar

Ho, Wai-Leng. 2001. “Bao Fang.” In An Age of Idealism Great Wall and Feng Huang Days, 106–19. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, Zhenyu 姜振宇. 2022. “Fensui sirenbang zhihou ji xin shiqi kehuan fazhan” 粉碎四人幫之後及新時期科幻發展 [The development of science fiction after the fall of the Gang of Four and the New Era]. In Ershi shiji Zhongguo kehuan xiaoshuoshi 20 世紀中國科幻小說史 [History of Chinese science fiction in the twentieth century], 115–89. Beijing: Peking University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Yizhuang 李以莊, and Zhou, Chengren 周承人. 2021. Xianggang yinmu zuo fang 香港銀幕左方 [Hong Kong movie screen from the left]. Hong Kong: Diatomic Creative and Production House.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Wenhe 柳聞鶴. 1964. “Rulai shen zhang da jiejue wu cuo” 如來神掌大結局唔錯 [Buddha’s palm finale is not bad]. Ming Pao 明報.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Wenhe 柳聞鶴. 1965. “Shenghuo ling chuxian xi lu zi pai zhang” 聖火令出現細路仔拍掌 [Sacred fire decree appears as kids clapping happily].” Ming Pao 明報.Suche in Google Scholar

Ruan, Lang 阮朗. 1980. “Sheya” 蛇牙 [Snake teeth]. In Xianggang xiaoshuo xuan 香港小說選 [Selected Hong Kong fiction], 242–70. Fujian: Renmin chubanshe.Suche in Google Scholar

Song, Mingwei. 2023. Fear of Seeing: A Poetics of Chinese Science Fiction. New York: Columbia University Press.10.7312/song20442Suche in Google Scholar

Ta, Kung Pao. 1972. “Sulian ren qi ming bei dijie chujing.” 蘇聯人七名被遞解出境 [Seven Soviets deported].Suche in Google Scholar

Ta, Kung Pao. 1977. “Su jiaqiang haiyun kuozhang Dongnanya geguo fandui” 蘇加強海運擴張 東南亞各國反對 [Soviet Union expands maritime transportation presence Southeast Asian countries express protest].Suche in Google Scholar

Tsang, Raymond. 2018. What Can a Neoi Gwei Teach Us? Adaptation as Reincarnation in Hong Kong Horror of the 1950s, 1, edited by Gary Bettinson, and Daniel Martin. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.3366/edinburgh/9781474424592.003.0002Suche in Google Scholar

Ye, Qin 葉沁. 1959. “Zhen you zhezhong lüse yeti ma?” 真有這種綠色液體嗎? [Is there really such a thing as a ‘Green Monster H Man’?]. Ming Pao 明報.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction

- Research Articles

- Between Shenguai and Science: The Visual Imagination of Technical Objects in Republican China

- The Broken Human–Object Continuum: The Technological Future and Socialist Contradictions in Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir (1958)

- Myth and Cyber: A Study of the Narrative and Visual Language of Chinese Cyberpunk Anime Films

- Navigating the World of The Stranger (1979) After the Cultural Revolution: Unveiling Hong Kong Leftist Science Fiction Film by Bao Fang

- Imagining an Alternative Future: Children’s Bodies in Wonder Boy (1988), Magic Watch (1990), and Mad Rabbit (1997)

- A Palimpsest of Hong Kong Futures Across Three Fictions (1962–2046)

- Cinematic Science Fiction, Indigenous Mythology, and Multispecies Entanglement: An Ecological Reading of The Mermaid (2016)

- Dreaming Fish, Becoming Fish: Animating Modern Mythology and Zhuangzian Philosophy in the Fantasy Film Big Fish & Begonia

- The Poetics of Journey to the West (2021): Disclosing a Way to Dwell in the World

- From Home to Homeland: Re-Imagining Chinese Diaspora in Recent Science Fiction Films

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction

- Research Articles

- Between Shenguai and Science: The Visual Imagination of Technical Objects in Republican China

- The Broken Human–Object Continuum: The Technological Future and Socialist Contradictions in Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir (1958)

- Myth and Cyber: A Study of the Narrative and Visual Language of Chinese Cyberpunk Anime Films

- Navigating the World of The Stranger (1979) After the Cultural Revolution: Unveiling Hong Kong Leftist Science Fiction Film by Bao Fang

- Imagining an Alternative Future: Children’s Bodies in Wonder Boy (1988), Magic Watch (1990), and Mad Rabbit (1997)

- A Palimpsest of Hong Kong Futures Across Three Fictions (1962–2046)

- Cinematic Science Fiction, Indigenous Mythology, and Multispecies Entanglement: An Ecological Reading of The Mermaid (2016)

- Dreaming Fish, Becoming Fish: Animating Modern Mythology and Zhuangzian Philosophy in the Fantasy Film Big Fish & Begonia

- The Poetics of Journey to the West (2021): Disclosing a Way to Dwell in the World

- From Home to Homeland: Re-Imagining Chinese Diaspora in Recent Science Fiction Films