Abstract

The Zaghawa language, one of the Saharan languages spoken in western Sudan, specifically the Darfur region, and east-central Chad, is the subject of this descriptive study with special focus on Arabic borrowings. The paper investigates Sudanese Standard Arabic and Baggara Arabic borrowings that have entered Zaghawa through contact with speakers of Arabic. This will be accomplished by showcasing and analyzing the phonological and morphological characteristics of the recipient language, as well as by demonstrating how the Arabic words that were borrowed have been adapted into Zaghawa. The semantic fields of the lexical borrowings are also discussed. Zaghawa exists in a community which is greatly influenced by Islam and the Arabic language. The major dialects of Zaghawa are Wegi, Kube, and Tuba and there are two minor dialects, Dirong and Guruf. Wegi is considered one of the major dialects of Zaghawa wholly spoken in Sudan. The data for this contribution has been collected from speakers of the Wegi dialect living in Khartoum.

Arabic abstract

دي دراسة تحليلية وصفية عن الألفاظ المستلفة من العربي في لغة الزغاوة. لغة الزغاوة واحده من اللغات التابعة لمجموعة اللغات الصحراوية وبتكلموها في غرب السودان وتحديداً في منطقة دارفور وشرق ووسط تشاد. الدراسة بتبحث عن الكلمات المستلفة من اللهجة العامية السودانية ولهجة البقارة الدخلت لغة الزغاوه عن طريق التواصل المباشر مع البتكلموها. وده بتم عن طريق عرض وتحليل الخصائص الصوتية والمورفولوجية للغة المتلقية. وبرضو من خلال إظهار كيفية تطويع الكلمات العربية المستلفة لقواعد وأصوات لغة الزغاوة. قبيلة الزغاوة بتعيش في مجتمع متأثر باللغة العربية يإعتبارها لغة الإسلام. لهجات لغة الزغاوة الرئيسية هي الوقيع، الكوبي، التوبا لكن لهجات الديرونق والقوروف بتكلموهم بس في تشاد. البيانات للدراسة دي إتجمعت من الناس البتكلموا لغة الزغاوة العايشين في الخرطوم.

1 Introduction

Zaghawa, also known as Beria (Jakobi and Crass 2004), is a Saharan language spoken in Western Sudan, specifically in Darfur, as well as the Wadai region of eastern Chad (see Map 1). Zaghawa belongs to the Northeastern branch of Saharan, a subgroup of the Nilo-Saharan phylum (Dimmendaal et al. [2019]).

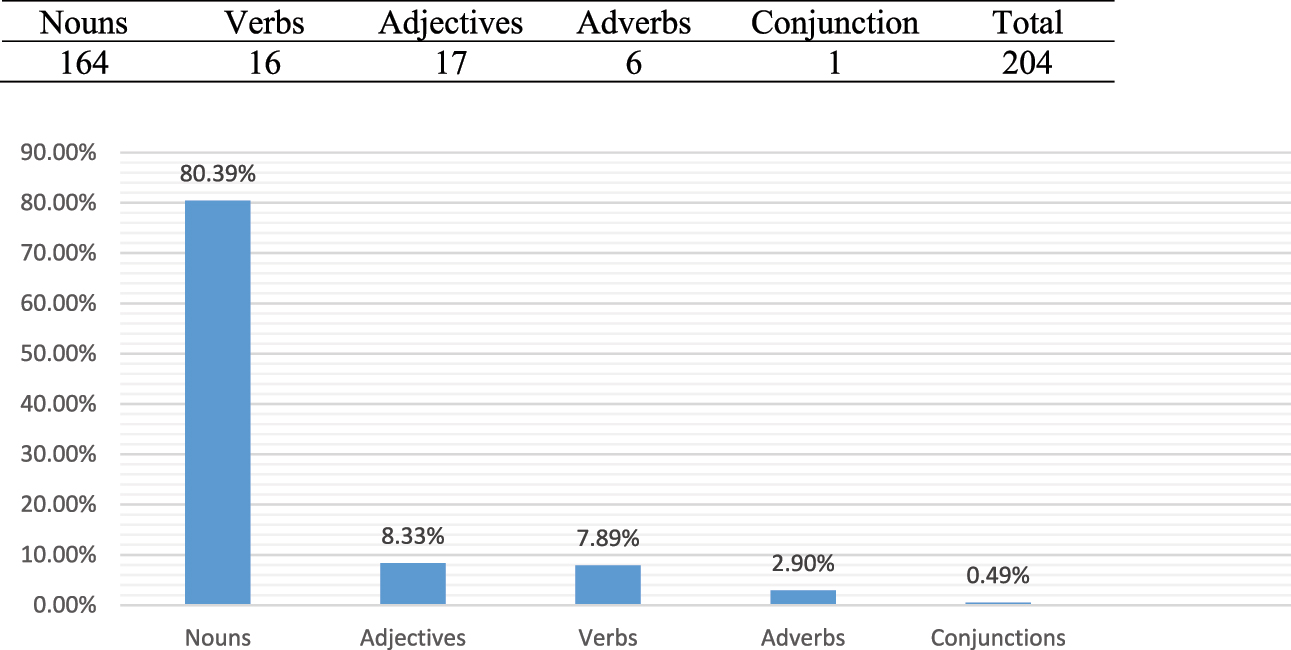

Number of borrowed items per grammatical category.

The Darfur region of Western Sudan’s inhabitants can be loosely classified into two ethno-linguistic stocks: Arabs (Baggara) and non-Arab (African) stock. People from various ethnic, linguistic, and cultural origins live in the region. Apart from Arabic, which is the language of communication between diverse ethnic and linguistic groups in Darfur, many Sudanese languages are spoken there, including Fur, Zaghawa, Masalit, Tama, Midob, and Daju, which all belong to the Nilo-Saharan phylum with its various sub-divisions. The region is known for its linguistic richness and multilingualism (Aldawi 2010: 1). The Zaghawa, for example, are generally bilingual in Zaghawa and Arabic. In truth, practically all Darfurians are bilingual in their own languages as well as Arabic.

Zaghawa is the third most populous non-Arab ethno-linguistic group in western Sudan (after Fur and Masalit, cf. Simons and Fennig 2018) and their language is considered one of the major languages in the area with respect to the number of speakers. According to Simons and Fennig (2018), the entire Zaghawa population in Sudan is around 180,000. The Zaghawa people divide their language into three primary dialects: Kube, near the border between Chad and Sudan; Tuba, sharing land with the adjacent Tama people in Sudan; Wegi, the largest of the three dialects remaining solely in Sudan. Dirong and Guruf, two minor dialects, are only found in Chad (Wolfe 1999: 11–12). It is worth noting that Zaghawa is also spoken in parts of Khartoum and Omdurman. Wolfe (1999: 13) noted that Zaghawa has borrowed substantially from Sudanese Arabic in his study on the phonology and morphology of Beria (i.e. Zaghawa). He wrote:

While it is impossible at this point in our understanding of Chadian and Sudanese languages to discern the extent of linguistic borrowing from neighboring peoples such as the Gorane, Tama, or Midob, it is certain that Zaghawa has taken a not insignificant section of its vocabulary from Arabic. Arabic, specifically the variety spoken in Eastern Chad and Western Darfur in Sudan, has now become the second language of nearly all Zaghawa men, and some Zaghawa women. This proves true more so in Sudan than in Chad.

According to Wolfe (1999: 13), the Wegi dialect spoken in Sudan shows in its lexicon the strongest Arabic influence of all the dialects. For example, he says, Wegi has lost the native words for ‘flower’, ‘dew’, and ‘heavy’ ([hudi] or [futi], [tier] or [tɛɉɪr], and [tei] respectively in the other dialects) in favor of Arabic [nawar], [nɛrɛ], and [tɛɡɪl].

The main objective of this paper is to provide a descriptive overview of the phonological and morphological structure of the Arabic borrowings adapted to Zaghawa. Lexical borrowing entails the integration of lexical items from the donor language to the recipient language. These items are generally referred to as “loanwords”. Grammatical borrowings, for their part, imply the integration of grammatical categories from the donor language to the recipient language. The type of borrowings that will be considered throughout this contribution are basically lexical, with reference to a few grammatical borrowings.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: the data and sources are briefly discussed in Section 2; Section 3 explains language contact and borrowing in the context of Arabic varieties; Sections 4 discusses phonological features and the integration of sounds in the recipient language; Section 5 focuses on the morphological integrations of loanwords, Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2 Data and sources

Although Darfur is the traditional region where many Zaghawa speakers can be found, Darfur was inaccessible at the time of data collection due to security concerns. As a result, the data for this study were gathered from two Zaghawa native speakers living in Khartoum between 2008 and 2009 and in 2016. The actual database compiled for this study was part of a larger fieldwork project during collecting data for my PhD thesis, which included recordings, elicitations, and narratives.

Zaghawa language regions in Sudan and Chad (source: Aldawi 2010: 2), modified for this study.

The fieldwork project involved two consultants: Esam Abdalla, a Zaghawa speaker and Sudanese linguist, helped in providing preliminary data at the beginning of this work; Elsadig Omda Elnur, a native speaker of the Wegi dialect of Zaghawa and a staff member at the department of Linguistics – University of Khartoum provided a great deal of the data informing this paper.

In preliminary quantitative terms, 204 entries of Arabic borrowings were isolated for the purpose of this study from wordlists, collected sentences and stories as listed in the Appendix. Figure 1 presents the number of borrowed items for each word category: the majority are nouns (80.39 %), followed by adjectives (8.33 %), and verbs (7.89 %). Adverbs are rare and are the least borrowed: most of the borrowed adverbs refer to time and place (2.9 %). Only one conjunction: laˈkin > làkɪ́n ‘but’ was noticed in our database (0.49 %).

3 Borrowing and contact with Arabic varieties

Linguistic borrowing takes place in an environment of language contact, and the degree and nature of the borrowing differ according to the nature of this contact. When linguists speak of language contact, they often refer to situations where speakers of these languages come into contact: “It is not languages which are in contact but the speakers” (Greenberg 1962:168). However, languages can come into contact independently of their speakers. As Greenberg (1962: 168) notes, the existence of literary traditions permits significant influence without contact between members of different speech communities and without bilingual speakers.[1] Accordingly, Abu-Manga (1999: 20–21) introduced two concepts of language contact: ‘close language contact’ and ‘peripheral language contact’; the former type relates to direct contact between the speakers of the languages whereas the latter refers to language influence through literary traditions without direct contact between the speakers. While the result of the ‘peripheral language contact’ is simple and limited (mainly lexical borrowing), the ‘close language contact’ yields several sociolinguistic phenomena on the part of the target language speakers: bilingualism, intensive borrowing, interference, loan-translation (calque), code-switching and language shift.

The Zaghawa and the Arabs have been in direct contact for centuries, and they have a long history of social and political interactions; the type of contact between their languages can thus be classified as ‘close contact’. Religious education (which Abu-Manga considers peripheral) also played a role in the history of contact. These types of contact lead to the sociolinguistic phenomena mentioned above, which cannot all be adequately treated in this study. For this reason, this study focuses on the phenomena of ‘borrowing’ and attempts to investigate the process of integration and adaptation of Arabic loanwords in the Zaghawa language. ‘Arabic’ here stands for Sudanese Standard Arabic, which is the main donor variety of Arabic. A few words have been borrowed from the Baggara Arabic dialect. This means that two varieties of Arabic are involved in this study.

Sudanese Standard Arabic[2] is spoken by city-dwellers and educated Darfurians who also know Darfur colloquial Arabic and (some) Classical Arabic (Ishaq 2002: 22). Sudanese Standard Arabic is also known as Sudanese Colloquial Arabic and acts as the central or prestige dialect. It is spoken over a vast area extending from northern Sudan (Nubia), along the Nile, through the Greater Khartoum area, and between the White and Blue Nile in Gezira and further down to the edges of the Southern Blue Nile regions (Qāsim 1975: 94–101). We follow Manfredi (2010) in naming this variety Sudanese Standard Arabic, abbreviated as SSA.

Baggara Arabic, henceforth referred to as BA, is a socio-geographic definition for the dialect spoken in Darfur and Kordofan State. According to Casciarri and Manfredi (2009) the term “Baggara (baggāra “cattlemen”) has neither ethnic nor genealogical pertinence, but it rather stresses the specifity of a production system”. The label “Baggara” has been adopted by Manfredi (2013: 143) as an attempt to include it into a dialect type characteristic of Arab semi-nomadic cattle herders living scattered through a vast area running from Lake Chad to the White Nile.

As stated by Roset (2018: 3) “the Arabs in Darfur are generally known to be nomadic camel breeders in the north, Abbala, or cow breeders in the south, Baggara. However, large groups within the Baggara consist of the (Arabicized) African ethnic group Fulbe from West-Africa. Other groups that identify themselves as Arabs, like Bideriya and Zayadiya became sedentary Darfurians in villages or towns years ago, sometimes decades or maybe centuries. The largest Arabs are called Rizeigat and Misiriya”.

The Arabic spoken in Darfur is divided into three groups (Doornbos 1989; Hoile 2008; Ishaq 2002; Roset 2018): Pastoral Arabic (Baggara Arabic), Sudanese Standard Arabic, Darfur Arabic.

Baggara Arabic is mostly spoken by monolingual Bedouin Arabs, whereas Sudanese Standard Arabic is spoken by city-dwellers and educated Darfurians. Darfur Arabic is spoken by illiterate and typically multilingual villagers; hence it is viewed as a minority variety compared to the other two. Arabic with its above-mentioned varieties is regarded as a language of trade and communication among speakers outside the same ethnic group.

The term ‘borrowing’ is used to refer to the incorporation of foreign elements into the speakers’ native language (Thomason and Kaufman 1988:21), i.e., as a synonym of adoption. For Haspelmath (2009: 36), “loanword (or lexical borrowing) is here defined as a word that at some point in the history of a language entered its lexicon as a result of borrowing (or transfer or copying)”. Haspelmath (2009: 46) recognizes two types of borrowing:

“Cultural borrowing: […]. This happens either by borrowing a lexeme from a donor language to refer to a certain concept or by using already existing words of the language to refer to new concepts which is similar to the process called semantic change or extension.

Core borrowing: loanwords that duplicate or replace existing native words. This can be related to the prestige factor of the donor language”.

The Zaghawa people engage in both types of borrowing. They borrow words from Arabic to refer to items for which there is no equivalent term in their language, i.e., “lexical fillers” in Manfredi’s (2014: 471) words. This definition relates to the cultural borrowings mentioned above by Haspelmath. Core borrowings (i.e., loanwords that duplicate or replace existing native words), however, do exist in Zaghawa as illustrated in Table 1:

Core borrowings in Zaghawa.

| SSA term | Zaghawa term | Borrowing | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ˈfarħan | káddóràì | fàrànî | happy/joyful person |

| ˈʕanɡareb | hītī | ə́nɡàrɛ̄p | traditional bed made of rope |

| ˈnuwar | húdì | náwàr | flower |

| ˈɟar | méʃî | ɟār | neighbor |

| ˈʕaʃara | tím | āʃārà | ten |

| ˈhini | kéì | hɪ̄nɪ̄ | here |

Core borrowings may serve to further distinguish a certain item, e.g., the Zaghawa have a native word for ‘bed’, hītī, but borrowed the Arabic word ˈʕanɡareb; the former relates to the traditional bed made of wood and rope, the latter to the modern, bigger sized bed made of refined wood and plastic. The noun nuwar in Sudanese Standard Arabic refers to ‘blossom’ but the Zaghawa use it to refer to ‘flower’.

The meanings of the borrowed Arabic lexicon fall within 16 semantic fields which can be broadly characterized as filling lexical gaps in the language. These can be seen in Table 2.

Semantic domains of Zaghawa borrowings from SSA and BA.

| Semantic domain | Arabic | Zaghawa | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religion | ˈɟaamiʕ | ɟámɛ̄ (n) | Mosque |

| ˈs ʕ alli | sɛ̀llɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | pray! | |

| ˈɁitwad ʕ d ʕ a | wɛ̀ddɪ̀-lɛ̄ (v) | perform ritual ablution! | |

| faˈɡiih | hɔ̀ɡɪ̄ (n) | ritual person | |

| ˈnabi | nèbī (n) | prophet | |

| ˈħaaɟ | hàɟī (n) | one who has made it to the pilgrimage | |

| Education | ˈxalwa | kálwà(n) | Qur’anic school |

| ˈt ʕ aalib | tāālɪ̀p (n) | student | |

| usˈtaaz | ústāās (n) | teacher | |

| kiˈtaab | kɪ̀tāp (n) | book | |

| ˈfas ʕ il | fɛ̀sɪ̀l (n) | classroom | |

| ˈɁaktib | kɛ̀tɪ̀bɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | write! | |

| ˈɁanɟaħ | nàɟàɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | succeed! | |

| ˈɁaɡra | ɡɛ̀rɪ̀-lɛ̄ (v) | read! | |

| ˈħis ʕ s ʕ a | hɪ́ssà (n) | lesson | |

| Trade | ˈsuɡ | sʊ̄k (n) | market |

| ˈɁitsawag | sàʊ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | shop! | |

| ˈɡiriʃ | ɡɪ̀rɪ̌ʃ (n) | money | |

| Social relations | ɡaˈbiila | ɡɛ́bɪ̄lɛ̀ (n) | clan/tribe |

| ˈsult ʕ an | sʊ̀ltǎn (n) | lordship | |

| Household items | kubˈbaaja | kʊ̀bbáɪ̀ (n) | glass |

| ˈkursi | kúrsì (n) | chair | |

| ˈʔood ʕ a | ɔ́dà (n) | room | |

| t ʕ araˈbeeza | tɛ́rbɛ̄sà (n) | table | |

| ˈʕuud | údú (n) | stick | |

| ˈɡalam | ɡɪ́làm (n) | pen | |

| ˈs ʕ aħan | sân (n) | plait | |

| Food & drinks | ˈfuul | húl (n) | beans |

| ˈʃaaj | ʃájɛ̀ (n) | tea | |

| ˈʃat ʕ t ʕ a | ʃɛ́ttɛ̀ (n) | hot pepper | |

| burtuˈkaan | bùrtùkān (n) | orange | |

| ˈbun | bʊ́nʊ̀ (n) | coffee | |

| ˈsukkar | sʊ́kkàr (n) | sugar | |

| ˈʕeeʃ | ēēʃ (n) | bread | |

| ˈbas ʕ al | bɔ́sɔ̀l (n) | onion | |

| ˈleemun | lómùn (n) | lemon | |

| Geography | xarˈt ʕ uum | hɔ̀rtʊ̄m (n) | Khartoum |

| maˈdiina | médīnè (n) | city | |

| Time and place expressions | ˈsana | sɛ́nɛ̄ (n) | year |

| ˈhassa | hāssāɡá a (adv) | now | |

| ˈsaʕa | sāà (adv) | hour | |

| ˈjoom | jòm | day | |

| ˈbarħa | bárīje | yesterday | |

| Time of prayers | ˈs ʕ ubuħ | sʊ̀bʊ̀ (n) | morning |

| ˈmaɣrib | màɡrèb (adv) | sunset | |

| ˈʕiʃa | ɪ̀ʃɪ̀ná (adv) | time after sunset until 9 o’clock | |

| Numerals | ˈʔalif | ɛ́lɪ̀f (n) | thousand |

| ˈmiyya | mɪ̂ (n) | hundred | |

| Transport | saˈfiina | séfīnè (n) | boat |

| ˈɡat ʕ ar | ɡàtàr (n) | train | |

| ʕaraˈbija | àràbéì (n) | car | |

| ˈt ʕ ajˈjaara | tàjjàr (n) | airplane | |

| Professions | ˈtaɟir | tʊ́ɟáràɪ̀ (n) | merchant |

| ˈtarzi | térsì (n) | tailor | |

| dikˈtoor | dáktʊ̄r (n) | doctor | |

| Property concepts | ˈʔas ʕ ffar | sāffār (adj) | yellow |

| ˈz ʕ ahri | zāhār (adj) | blue | |

| taˈɡiil(a) | tɛ́ɡɪ̄lɪ̀ (adj) | heavy | |

| ˈbajra | bɪ̀rā (adj) | maiden | |

| misˈkiin | mìskìn (adj) | poor | |

| kaˈfiif | kàfɔ̄ (adj) | blind | |

| Ethnic group | ˈʕarabi | àrbɪ̀ (n) | from an Arab group |

| Animals and insects | ˈħuut | hūt (n) | fish |

| ˈnaħal | nâl (n) | bees | |

| Various | ˈtob | tōb (n) | woman’s dress |

| ˈsuwwar | súwwâr (n) | rebels |

-

aZaghawa has deictic expressions for “here” and “there” but some speakers use the Arabic deictic ˈhini, thus we consider it to be a cultural borrowing. There is no Zaghawa equivalent for ‘now’, and the SSA ˈhassa has been borrowed.

4 Phonological adaptations of Arabic borrowings

This section does not intend to describe Zaghawa and Arabic phonology in its entirety; it will restrict itself to the phonological aspects that are relevant to the integration of borrowed items.

Within the domain of phonological adaptation, the following phenomena have been observed: consonant adaptation, vowel integration and vowel shortening, syllable adaptation, gemination; some general observation on the correlation between stress and tone in both languages will also be discussed.

Before presenting the phonological adaptations of the Zaghawa borrowings, a brief overview of the relevant phonological features of both languages is given.

4.1 Consonant adaptation

The phonemic charts below illustrate the consonants in Sudanese Colloquial Arabic and Zaghawa. Table 4 is adopted from Osman (2006: 351) and has been modified for our purpose.

The data for the Zaghawa language, Sudanese Standard Arabic, and Baggara Arabic are written in IPA symbols. There are areas where we deviate from IPA to present certain phonological features of the language: gemination and vowel length will be written with double letters instead of [:], and ATR vowel distinctions will be written with symbols for tense and lax vowels rather than diacritics. Stressed syllables of Arabic words are represented by a raised vertical line [ˈ ] at the beginning of the syllable.

Borrowings undergo phonological operations to adapt to the phonological system of the recipient language. With Arabic borrowings, the most consistent phonological feature in consonant adaptation is the systematic replacement of the pharyngealized (emphatic) consonants by their non-emphatic counterparts.

4.1.1 Consonant replacement

As can be seen in Tables 3 and 4 above, the consonant inventory of Arabic is larger than that of Zaghawa. Certain consonants that do not exist in Zaghawa, namely emphatics, pharyngeal fricatives, and velar fricatives, are systematically replaced in Zaghawa.

Standard Sudanese Arabic consonants.

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Alveolar | Emphatic | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive Voiceless |

t | tʕ | k | ʔ | ||||

| Plosive Voiced |

b | d | dʕ | ɟ | ɡ | |||

| Fricative voiceless | f | s | sʕ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | |

| Fricative voiced | z | zʕ | ɣ | ʕ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||

| Approximant | w | j |

Zaghawa consonants.

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive Voiceless |

t | k | ʔ | |||

| Plosive Voiced |

b | d | ɟ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | s | ʃ | h | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Lateral | l | |||||

| Flapped | ɾ | |||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Semivowel | w | j |

All emphatic (pharyngealized) consonants are replaced by their non-emphatic counterparts. This is illustrated by example (1) below:

| tʕ → t | ˈʃatʕtʕa > | ʃɛ́ttɛ̀ | chili |

| t ʕ aˈmaat ʕ im > | tɪ́màtɪ̀m | tomato |

| d ʕ → d | ˈd ʕ aruri > | dɔ́rʊ́rɪ̀ | important |

| d ʕ aˈħija > | dɛ́hɪ̄jɛ̀ | slaughter of animals for a religious ritual |

| s ʕ → s | ˈbas ʕ al > | bɔ́sɔ̀l | onion |

| ˈs ʕ abur > | sɔ́bʊ̀r | patience |

There is an exception to this emphatic replacement rule. The emphatic / zʕ/ is replaced by the voiced alveolar fricative [z]. /z/ is not a phoneme in Zaghawa, and this is the only instance of [z] in our database, suggesting it may be a result of phonological adaptation, see (2).

| ˈzʕahri > | zàhār | blue |

The voiceless velar fricative /x/ is integrated as the voiceless glottal fricative /h/. This type of change does not occur systematically in every borrowing, and some words are pronounced with [x] e.g., ‘Khartoum’ is pronounced by some speaker of Zaghawa as xɔ̀rtʊ̄m (cf. example 3 below). An explanation could be that due to the long-term contact with Arabic the sound [x] is becoming familiar and integrated in the phonological system of Zaghawa.

On the other hand, the voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ is integrated as voiced plosive /ɡ/ as illustrated in (3b).

| x → h | ˈxabar > | hābàr | news |

| xarˈt ʕ uum > | hɔ̀rtʊ̄m | Khartoum | |

| ˈxulal > | hʊ́làl | comb |

| ɣ → ɡ | ɣalˈbaana > | ɡálbānè | pregnant/ weak woman |

| ˈɣali > | ɡálì | expensive | |

| maɣˈrib > | màɡrèb | sunset |

The voiced alveolar fricative /z/ is replaced by the voiceless fricative /s/. /z/ can be realized as /d/ in BA borrowings as presented in (4b).

| z → s | ˈustaaz > | ústāās | teacher |

| ˈtarzi > | tèrsì | tailor | |

| t ʕ araˈbeeza > | tɛ́rbɛ̄sà | table | |

| ˈɟuzlan > | ɟɪ́slân | wallet |

| z → d | ˈzel > | dēl | penis |

4.1.2 Final and pre-final plosive devoicing

A categorial phonological rule in Zaghawa is final plosive devoicing. This feature has been observed in the Arabic borrowings as discussed below.

Bilabial /b/ → [p]. Although /p/ is not a phoneme in Zaghawa, [p] is claimed to be an allophone of /b/ specially word finally. Consider example (5):

| ˈtʕaalib > | tāālɪ̀p | student |

| kiˈtaab > | kɪ̀tāāp | book |

Alveolar /d/→[t]. The devoicing of these phonemes can be observed word finally in (6).

| ˈaɟaawiid > | óɟúwààt | elders of the village |

Velar /ɡ/ → [k]. Also observed in word final position as shown in (7).

| ˈibriiɡ > | íbrîk | plastic kettle |

| ˈs ʕ andooɡ > | sàndók | box |

| ˈsuɡ > | sʊ̄k | market |

| ˈs ʕ adaɡ > | sɪ̀dák | dowry |

The plosive devoicing rule is not systematically applied, and out of 19 words with a final voiced plosive, some exceptions have been found (see Appendix at the end):

b→p; over 12 words 9 have final [b], 2 have final [p] and 1 has [b] with final epenthesis.

d→t; attested in 3 words; 1 has final [d], 1 has final [t], and 1 has [d] with final epenthesis.

ɡ →k; attested in 4 words.

4.1.3 Consonant lenition

In some Arabic borrowings the initial and medial /f/ have become [h] according to a process of debuccalization. This is particularly visible in some words in the Wegi dialect. According to Wolfe (1999: 29) “the initial /f/ is an original feature of the Dirong dialect, which has become [h] in other dialects of Zaghawa”. However, not all /f/ have become [h] in Wegi. Lenition of the voiceless fricative /f/ which is realized as voiceless glottal [h] can be seen in (8) in Arabic borrowings.

| ˈfaɡiih > | hɔ̀ɡɪ̄ | ritual person |

| ˈfuul > | húl | beans |

| ˈkafan > | kéhèn | shroud |

Our database shows that the lenition /f/ → [h] is not systematic, and from the 12 examples of initial and medial /f/, there are examples where the lenition does not take place; Of 9 initial /f/, 6 words retain the [f]; 3 words show the lenition to [h], and of 3 medial /f/, only one changes to [h].

4.1.4 Consonant elision

The voiced pharyngeal /ʕ/ is elided in all positions in the Zaghawa borrowings, see example (9).

| ˈʕeeʃ > | ēēʃ | bread |

| ˈt ʕ aʕam > | tâm | taste |

| ˈmurabbaʕ > | márābbà | square |

The voiceless pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ is realized as the voiceless glottal fricative /h/ in some words.

| ˈbaħar > | báhàr | sea/lake |

| ˈħadiid > | hádìd | iron |

Wolfe (1991: 31) also noticed that “Word internal [h] is unstable in Zaghawa”. In several instances the /ħ/ and /h/ are elided in intervocalic position; when the pharyngeal fricative is realized as glottal fricative (/ħ/ → /h/), the medial [h] can be dropped in Zaghawa regardless of the origin of the word, i.e. the elision takes place in Arabic borrowings or in Zaghawa words. This suggests that the loss of the intervocalic fricative is a rule in the language. Consider example (11):

| ˈsʕaħan > | sân | plate |

| ˈnaħal > | nâl | bees |

| ˈmaħaɟum > | mààɟʊ̂m | one who has been cupped |

| ˈdahab > | dâb | gold |

However, the pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ is always elided in final position as illustrated in example (12a and 12b).

| ˈsʕubuħ > | sʊ̀bʊ̀ | morning |

| ˈtumsaaħ > | tɪ́msà | crocodile |

The word final voiced fricative /f/ is deleted in example (13). This is the only instance in our database.

| ˈkafif > | kàfɔ̄ | blind person |

4.2 Vowel integration and vowel shortening

As for the vowel system, Sudanese Arabic exhibits five vowels in its system: front /i /, /e / central /a/, and back /u/, /o/ beside the long vowels: [ii], [ee], [aa], [uu], [oo] (Table 5).

Sudanese Arabic vowels.

| i | u | |

| e | o | |

| a |

It should be noted that vowel length is not contrastive in Zaghawa while Arabic has a length differentiation. Long vowels in Zaghawa are only attested in lexical items composed of more than one morpheme (Wolfe 1999: 36), i.e., across morpheme boundaries, as in (14) below.

| bɛ̀r | ɔ̄ɡɡāɪ́-ɪ́ |

| they | nice-copː3pl |

| ‘They are beautiful’ | |

However, in the Zaghawa borrowings from Arabic, vowel length is occasionally kept regardless of its morpho-phonological context, e.g., ˈʕeeʃ > ēēʃ ‘bread’, and ˈustaaz > ústāās ‘teacher’.

For Zaghawa, Wolfe (1999), Jakobi and Crass (2004) and later Mathes (2015) proposed nine vowels; this analysis has been adopted also in the present study. Osman (2006: 354) a native speaker of the language, argued that like many Nilo-Saharan languages, Zaghawa has ten vowels, thus including the schwa /ə/ which he considered in his analysis the +ATR counterpart of /a/. Jakobi and Crass (2004) have excluded the schwa considering it as an allophonic variant of /a/ e.g., ə̀kkàɪ̀ ‘chewing’.

Zaghawa has vowel harmony based on the feature Advanced Tongue Root (ATR), which is used to label two sets of contrastive vowels. The [+ATR] vowels are articulated with more advanced tongue root position in the vocal tract compared to their [-ATR] counterparts (Mathes 2015: 180).

In Zaghawa, vowel harmony is observed between roots and affixes (Table 6). Zaghawa has root-controlled ATR harmony. In a simple word, vowels of the two ATR sets do not mix, apart from /a/, and the affixes harmonize with the ATR value of the root vowel. This is illustrated in Table 7 and in examples (15) to (18).

Zaghawa vowels.

| [+ATR] | [-ATR] | ||

| i | u | ɪ | ʊ |

| e | o | ɛ | ɔ |

| a | |||

Roots.

| [+ATR] | Gloss | [-ATR] | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| èbī | air | ɪ̀ɡā | chest |

| bòtū | rain | ɛ̄ɪ̄nɪ̄ | straw |

| úrú | bone | hàʊ̄ | donkey |

Examples (15) and (16) illustrate the [+ATR] and [-ATR] affixes, respectively:

| kū-ɡū-r-í |

| 3pfv-swallow-subj:3sg-pfv |

| ‘She swallowed’ |

| ʃɛ̄-ɡ-ɪ́ |

| eat-subj:1sg-pfv |

| ‘I ate’ |

Except for the 3rd plural perfective example in (17), the negative marker -u, and the imperative plural marker -u, all affixes agree in their ATR value with the vowels of the root they attach to.

| kɪ̀-là-l-ǔ |

| 3pfv-buy-subj:3sg-pfv:pl |

| ‘They bought it [no harmony]’ |

The /a/ in Zaghawa is considered a neutral vowel which can exist with [+ATR] (see example 17) or [–ATR] sets. When it is alone in the root, it triggers [-ATR] harmony on suffixes, as in (18).

| là-l-ɔ́ |

| buy-subj:2sg-neg |

| ‘Do not buy’ |

The Arabic borrowings adapt to the nine-vowel system of Zaghawa. There are no strict phonological rules that govern the integration of vowels in the Zaghawa borrowing, but the following observations can be made.

The [+ATR] and [-ATR] interpretations of Arabic vowels strongly depend on the consonants in the Arabic word. If the Arabic word has an emphatic consonant or /ɡ/, [-ATR] vowels are found in the Zaghawa borrowing, e.g. bɔ́sɔ̀l < ˈbas ʕ al ‘onion’, ʃɛ̄ttɛ̀ <ˈʃat ʕ t ʕ a ‘chili’, sʊ̄k<ˈsuɡ ‘market’. If the word does not contain the above-mentioned consonants, [+ATR] vowels tend to be used, e.g., tèrsì <ˈtarzi ‘tailor’.

For Arabic nouns in which vowel length is significant, the equivalent Zaghawa borrowing has [+ATR] vowel quality, e.g., húl <ˈfuul ‘beans’.

4.3 Syllable adaptation

SSA words may be either monosyllabic or multi-syllabic, and their basic syllable patterns are CVVC, CVC, CV, and CVV.

Zaghawa syllable structure follows four patterns: CV, VC, V, and CVC (Table 9).

Borrowings are incorporated by using the preferred syllable structure of the recipient language. Our data revealed several instances of syllable restructuring, whereby syllables are becoming short due to either vowel shortening, or consonant elision as shown in Table 10. The syllables illustrated in Table 8 may be kept in the Arabic borrowings or shortened to fit the syllable structure of the language. Compare the syllable structure of the Arabic words in Table 8 and their structure in the borrowed word in Table 10.

Syllables structure of SSA.

| SSA | Syllable structure | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| ˈʕeeb | CVVC | shame |

| ˈbun | CVC | coffee |

| ˈʕuud | CVVC | stick |

| ˈdahab | CV.CVC | gold |

| ˈmiyya | CV.CCV | hundred |

Syllable structure of Zaghawa.

| Zaghawa | Syllable structure | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| ʊ̀r | VC | belly |

| ɲà | CV | child |

| dɪ̀n | CVC | tail |

| ɔ̀ | V | person |

Syllable adaptation in Arabic borrowings.

| SSA/BA | Syllable structure | Zaghawa loan | Syllable structure | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ˈʕeeb | CVVC | ēb | VC | shame |

| ˈdahab | CV.CVC | dâb | CVC | gold |

| ˈt ʕ aʕam | CV.CVC | tâm | CVC | taste |

| ˈfuul | CVVC | húl | CVC | beans |

| ˈʕeeʃ | CVVC | ēēʃ | VVC | bread |

| ˈʔood ʕ a | CVV.CV | ɔ́dà | V.CV | room |

The syllable adaptation in ˈfuul > húl shows that the vowel is shortened to fit the Zaghawa CVC pattern. In ˈʕeeb > ēb the syllable has been reduced from CVVC → VC due to the loss of the onset consonant and vowel shortening. VVC syllable types are not attested in Zaghawa, thus the result is a VC monosyllabic word. Similarly, in ˈʕuud > údú, the onset consonant is lost, and final epenthesis occurs. Zaghawa occasionally does not allow voiced /d/ and /ɡ/ word finally, and they are either devoiced or epenthesis occurs. The VC with final [b] in ēb is acceptable and the devoicing rule does not apply, whereas VC with final [d] in ˈʕuud is not allowed. This proves that there are exceptions to the devoicing rule and that it is not systematically applied. In ˈʕeeʃ > ēēʃ the initial pharyngeal is elided resulting in CVVC → VVC. Vowel length is occasionally kept as in ēēʃ (see 5.2.).

In ˈdahab > dâb and ˈt ʕ aʕam > tâm the initial disyllabic word is reduced to a monosyllabic word: CV.CVC → CVC. The closed syllable is the result of the elision of the intervocalic pharyngeal and traces of the VV sequence can be seen in the resulting falling tone.

The di-syllabic structure of the word ˈʔood ʕ a > ɔ́dà CVV.CV → V.CV is shortened because of the loss of the onset consonant in addition to the shortening of the intervocalic vowel plus vowel harmony, i.e., -ATR triggered by the final /a/.

In addition to vowels, Wolfe (1999: 36) distinguished eight diphthongs, and Osman (2006: 354) identified six diphthongs in the phonological system of Zaghawa. According to our observations, the Zaghawa phonological system includes eleven diphthongs with a ±ATR contrast, as presented in the following examples compiled in Table 11. The gaps in the system have a clear pattern: /a/ is not part of a diphthong where the other vocalic element is +ATR. The integration of these diphthongs into SSA words is presented in Table 12.

Diphthongs in Zaghawa.

| Diphthong | Word | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| ɪa | ɪ̀ā | mother |

| ɛɪ |

dɛ̄ɪ́

tɛ̀ɪ̄ |

distinguishing issue/matter |

| ei |

dèī

bèí |

foot goats |

| aɪ | āɪ̄ | 1st person independent pronoun |

| dàɪ̄ | female camel | |

| aʊ |

āʊ̄-l-ɪ̄

sāʊ̄-r-ɛ́ hàʊ̄ |

I stopped (s)he learns donkey |

| ɔɪ | kɔ̀ɪ̀-lɛ̄l-lɛ̀ | you are afraid |

| sɔ̀ɪ̄ | smallpox | |

| oi |

kòī

òì |

cane of water/millet/sorghum shock of hair |

| ɔʊ |

kɔ̀ʊ̄

ɡɔ̀ʊ̄ |

pain calabash pot |

| ou | ōū-r-ɪ᷄ | (s)he entered |

| bòū-r-i | (s)he abandoned | |

| ʊɪ |

ʊ̄ɪ́

kʊ̄ɪ́ |

cry (noun) send him! (IMP.2SG) |

| ui |

tùī

būì |

evening pull! (IMP.2SG) |

SSA VCV, CV sequences replaced by diphthongs in the Zaghawa borrowings.

| VCV, CV sequence in SSA | Equivalent diphthong in Zaghawa | SSA/BA word | Zaghawa loan | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aya | aɪ | kub.ˈbaa.ya | kʊ̀bbáɪ̀ | glass |

| awa | aʊ | ˈta.saw.aɡ | sàʊ̀ɡ-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ | he shopped |

| iya | ei | ʕa.ra.ˈbiya | àràbéì | car |

| ħa | ie | ˈbar.ħa | báríē | yesterday |

| ˈfat.ħa | fátíē | the first chapter of the Quran/blessing/ prayer |

The following VCV, and CV sequences in SSA are replaced by a diphthong in the Zaghawa borrowing, as shown in Table 12.

4.4 Tone adaptation

Whereas Zaghawa is a tonal language, Arabic is a stress language. Stress patterns in SSA can be summarized as follows. The heavy syllable, i.e., any syllable with a long vowel and non-final CVC syllables, is stressed if there is only one heavy syllable in the word, e.g., usˈtaaza ‘teacher’ (feminine). If there is more than one heavy syllable, stress falls on the penultimate heavy syllable, e.g., t ʕ aˈmaat ʕ im ‘tomatos’. Otherwise, stress falls on the penultimate syllable of the word, e.g., ˈkatab ‘he wrote’.

Zaghawa is a tonal language which distinguishes between three tone levels: high (H), low (L) and mid (M). Zaghawa often allows two or more of these tones in succession on single syllables, creating contour tones (cf. Clements 2000: 152). The contour tones that exist in Zaghawa are rising (LH), falling (HL), mid-falling (ML), and mid-rising (MH). Contour tones may mark a single monophthong, or they may extend across a diphthong. They occur on a monosyllabic word or on the final syllable of a di-syllabic word. They are marked with the following diacritics: [ ̂ ] HL, [ ̌ ] LH, [ ᷆ ] ML, and [ ᷄ ] MH.

Osman (2006: 357) states that “the Zaghawa language uses tone grammatically to draw a distinction between singular and plural nouns and, lexically, to differentiate between varied meanings of the same phonological segments, i.e., lexical tone”. Tone is also used to mark aspect differentiations in verbs. Consider the examples in Table 13, Table 14 and in example (19 a and b).

Lexical tone (after Osman 2006: 359).

| Word | Gloss |

|---|---|

| têr | pus |

| tēr | white |

| tèr | sharpen |

| těr | outside |

Grammatical tone in nouns (after Aldawi 2010: 139–142).

| Singular | Plural | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| ɲà | ɲá | child/children |

| táɡɔ̄ | tāɡɔ́ | breast/breasts |

| kɛ̀bɛ̀ | kɛ̀bɛ́ | ear/ears |

| ɟàrɔ̄ | ɟàrɔ̂ | brother (in law) /brothers (in-law) |

The following examples show grammatical tone in perfective (19a) and imperfective (19b) verbs:

| kùrù-ɡī-l-í |

| crawl-pfv-aux-3subj-aff |

| ‘It crawled’ |

| kùrū-l-Ø-è |

| crawl-aux-3subj-ipfv |

| ‘It crawls’ |

Our data reveals that there are no correlations between Arabic stress and tone in Zaghawa borrowings. The existence of grammatical tone in the categories of nouns, adjectives and verbs in Zaghawa makes it difficult to find a correlation between stress and tone. Arabic borrowed words are adapted to the grammatical tone marking system of Zaghawa regardless of their stress pattern.

4.5 Gemination

Gemination is a common feature of Zaghawa phonology, and it can be lexical as in káddó ‘happy person’ or it can arise grammatically, in the formation of verbal nouns (see Section 5.4), in the formation of plural adjectives (by geminating the intervocalic consonant) and in the intensification of adjectives (like ‘new’ to express ‘very new’). It is always an intervocalic consonant which is geminated; consider the examples in Tables 15 and 16 below:

Geminated consonants in Zaghawa.

| Place & manner of articulation | Word | Gloss | Word | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial plosive | ɛ́bbɛ́ | make | ɛ́bbɛ́rɛ́ (v) | it makes me |

| bɪ̀rr | steal | ɛ̄bbɪ̀r (vn) | stealing | |

| ʊ́bʊ̀ɪ̀ (sg) | new | ʊ́bbʊ́ɪ́ (adj:pl) | new | |

| Nasal plosives | sínnā | nose | sínnā (n) | nose |

| tɪ̄m | cut | tɪ̄m-mɔ̀ (v:imp) | cut! | |

| kʊ́ɲàɪ̀ (sg) | few | kʊ́ɲɲáɪ́ (adj :pl ) | few | |

| Alveolar plosives | káddó | happy | káddóràì (n) | happy person |

| kádàɪ̀ (sg) | kind | káddáɪ́ (adj:pl) | kind | |

| tàmàɪ̀ | mature | àttàmàɪ̀ (vn) | maturing like in cooking | |

| tɔ̀ | taste | ɔ̀ttɔ́ (vn) | tasting | |

| ɛ́ttɛ̀ | fall | kɛ́ttɛ̀ɪ̀ (v) | (s)he fell | |

| Velar plosive | kàɪ̀ | chew | ə̀kkàɪ̀ (vn) | chewing |

| tákʊ́nɛ̀ | fragile | tákkʊ́nɛ́ (adj) | very fragile | |

| óɡàì (sg) | beautiful | óɡɡáí (adj:pl) | beautiful | |

| Palatal plosive | ɟā | hide | āɟɟā (vn) | hiding |

| Semi-vowel | náwɪ̀ | bad | náwwɪ́ (adj) | very bad |

| Lateral | kɪ́llà | sister | kɪ́llà (n) | older sister |

| ɡʊ̄llʊ̄ | eggs | ɡʊ̄llʊ̄ (n) | eggs | |

| Alveolar fricative | sɔ̀ɪ̀ | sew | àssɔ̀ɪ̀ (vn) | sewing |

| mɪ̄s | wipe | mɪ̄s-sɔ̀ (v:imp) | wipe with oil! | |

| Palatal fricative | kárʃʊ́nɛ̀ | thin | káʃʃʊ́nɛ́ (adj) | very thin |

Gemination in the Arabic borrowings.

| Place & Manner | SSA | Arabic borrowing | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velar plosive | ˈsukkar | sʊ́kkàr | sugar |

| Bilabial plosive | kubˈbaaja | kʊ̀bbáɪ̀ | glass |

| Alveolar plosive | ˈʃat ʕ t ʕ a | ʃɛ́ttɛ̀ | chili |

| Labio-dental fricative | ˈɁas ʕ ffar | sáffàr | yellow |

| Alveolar fricative | ˈhis ʕ s ʕ a | hɪ́ssà | lesson |

| Lateral | ˈs ʕ alla | sɛ̀llɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ | prayer |

| Semi vowel | t ʕ ajˈjaara | tàjjàr | airplane |

-

All consonants can occur geminated in Arabic nouns, thus the gemination is retained after they are borrowed to Zaghawa.

Gemination in Arabic is contrastive: it may express grammatical distinctions, as in ˈakal ‘he ate’, and ˈakkal ‘fed someone (CAUS)’; it may signal lexical distinctions, as in ˈɟamal (n) ‘camel’, and ɟaˈmmal (v) ‘make beautiful (CAUS)’.

Since both languages exhibit gemination, Arabic borrowings in Zaghawa retain their geminated consonants. Our data provided a considerable number of borrowed lexical items with geminated consonants:

5 Morphological integrations

This section is concerned with the morphological adaptations that have been observed in Zaghawa. It focuses on how SSA and BA nouns and adjectives modifying other nouns are adapted to the number marking system of Zaghawa. It further points out the gender marking and other phonological distinction between BA and SSA nouns. Finally, it illustrates the morphological adaptations of verb stems borrowed into Zaghawa.

5.1 Nominal number marking

Arabic has a complex system of plural formations. With very few exceptions (see Table 21), Zaghawa borrows the singular word which is integrated with the morphology and tonology of the language.

Number on Zaghawa nouns is marked by tone: Arabic nouns are borrowed in their singular form (with or without the Arabic feminine suffix -e/-a), and after various phonological integration processes have taken place, tonal morphology is applied to mark number. This process is illustrated in Table 17.

Tonal number marking of Arabic borrowings.

| SSA | Zaghawa borrowing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SG | PL | SG | PL |

| ˈħut | ˈħet-aan | hʊ̀t ‘fish’ | hʊ́t ‘fishes’ |

| ˈfaɡiih | ˈfʊɡaha | hɔ̀ɡɪ̄ ‘ritual person’ | hɔ̄ɡɪ́ ‘ritual people’ |

| ˈʔahal | ʔaˈhaal-i | áhàl ‘family’ | áhál ‘families’ |

| ˈɡat ʕ ar | ɡit ʕ aˈr-aat | ɡàtàr ‘train’ | ɡàtár ‘trains’ |

| ˈsafiina | ˈsʊfʊn | séfīnè ‘ship’ | sēfíné ‘ships’ |

| ˈɡabiila | ˈɡabaa(y)il | ɡɛ́bɪ̄lɛ̀ ‘clan’ | ɡɛ̄bɪ́lɛ́ ‘clans’ |

| ˈmadiina | ˈmʊdʊn | médīnè ‘town’ | mēdíné ‘towns’ |

| ʕaraˈbiya | ˈʕarab-aat | àràbéì ‘car’ | àràbéí ‘cars’ |

| ˈʕuud | ˈʕid-aan | údú ‘stick’ | údû ‘sticks’ |

| ˈbajra | ˈbajr-aat | bɪ̀rā ‘maiden’ | bɪ̀râ ‘maidens’ |

| ˈkafiif | kaˈfiif-iin | kàfɔ̄ ‘blind person’ | kàfɔ̂ ‘blind people’ |

Nominal number inflections in Zaghawa are marked by tonemes with no segmental alternations to the root. The singular may adopt several tonal patterns; this applies also to the plural. According to Jakobi and Crass (2004), there are ten tonal classes in Zaghawa that mark number and have been attested in our data (Aldawi 2010), as shown in Table 18.

Tonal classes marking nominal number in Zaghawa.

| Tonal class | SG | PL |

|---|---|---|

| Class 1: l/h | tà ‘head’ | tá ‘heads’ |

| Class 2: hm/hl | ɔ́mɔ̄ ‘ostrich’ | ɔ́mɔ̀ ‘ostriches’ |

| Class 3: hh/mh | kítí ‘skin’ | kītí ‘skins’ |

| Class 4: hh/hhl | súndó ‘date’ | súndô ‘dates’ |

| Class 5: ll/lh | kɛ̀bɛ̀ ‘ear’ | kɛ̀bɛ́ ‘ears’ |

| Class 6: lm/lhl | bɪ̀ɛ̄ ‘house’ | bɪ̀ɛ̂ ‘houses’ |

| Class 7: hm/hh | hítī ‘traditional bed’ | hítí ‘traditional beds’ |

| Class 8: hm/mh | hɪ́rtɛ̄ ‘horse’ | hɪ̄rtɛ́ ‘horses’ |

| Class 9: hl/hh | kɔ́sʊ̀ ‘brother’ | kɔ́sʊ́ ‘brothers’ |

| Class 10: lhl/lh | àbʊ̂ ‘grandmother’ | àbʊ́ ‘grandmothers’ |

Tonal classes attested in borrowings.

| Tonal class | Tone pattern | Zaghawa loan | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SG | PL | ||

| Class 1 | L/H | hʊ̀t ‘fish’ | hʊ́t ‘fishes’ |

| ɟàr ‘neighbor’ | ɟár ‘neighbors’ | ||

| Class 4 | HH/H.HL | údú ‘stick’ | údû ‘sticks’ |

| ɪ́lɪ́m ‘science’ | ɪ́lɪ̂m ‘sciences’ | ||

| Class 5 | LL/LH | tàrfʊ̀ ‘bird’ | tàrfʊ́ ‘birds’ |

| fɛ̀sɪ̀l ‘classroom’ | fɛ̀sɪ́l ‘classrooms’ | ||

| Class 6 | LM/L.HL | ʃìtān ‘devil’ | ʃìtân ‘devils’ |

| kàfɔ̄ ‘blind person’ | kàfɔ̂ ‘blind people’ | ||

| Class 8 | HM/MH | hɔ́ɡɪ̄ ‘ritual person’ | hɔ̄ɡɪ́ ‘ritual people’ |

| ɟámɛ̄ ‘mosque’ | ɟāmɛ́ ‘mosques’ | ||

| Class 9 | HL/HH | ɡɪ́làm ‘pen’ | ɡɪ́lám ‘pens’ |

| ɔ́dà ‘room’ | ɔ́dá ‘rooms’ | ||

| Cass 10 | L.HL/LH | kʊ̀bbáɪ̀ ‘glass’ | kʊ̀bbáɪ́ ‘glasses’ |

| màɟʊ̂m ‘person who has been cupped’ | màɟʊ́m ‘people who have been cupped’ | ||

Seven of the mentioned tone patterns have been observed marking singular and plural nouns in our loanword database (Table 19).

Some of the tonal patterns have been modified to fit the syllable structure of the Arabic borrowings, i.e., tonal class (9) has been modified to fit the syllable structure of the Arabic borrowing, sân (sg.) sán (pl.) ‘plate, plates’, and nâl (sg.), nál (p.l) ‘bee, bees’, resulting in a falling tone (HL) for the singular and a high tone for the plural; the underlying structures of these nouns are sáàn, and náàl but because of the consonant elision and reduction of vowel length, the result is a falling tone.

Adjectives in Zaghawa express an attribute of the noun they modify and tend to agree in number with their heads (Aldawi 2010: 157).

Syntactically, Zaghawa adjectives follow their heads; the adjectival word in (20) is marked by the definite clitic =dɔ:

| tɛ́lɛ̀ | óɡàɪ̀=dɔ̀ | lɛ᷆-kàlɪ̀-l-Ø-ɛ̄ |

| girl | beautiful-def | prog-laugh-aux-3subj-ipfv |

| ‘The beautiful girl is laughing’ | ||

Attributive adjectives in SSA are inflected by means of a suffix morpheme and they copy all the grammatical features of the noun they modify, agreeing in gender, number and definiteness as illustrated in example (21).

| Ɂal-ˈustaaz-a | Ɂal-ˈʃatʕr-a |

| def-teacher-sg:fem | def-clever-sg:fem |

| ‘The clever female teacher’ |

| Ɂal-ˈustaaz-at | Ɂal-ˈʃat ʕ r-at |

| def-teacher-pl:fem | def-clever-pl:fem |

| ‘The clever female teachers’ |

Zaghawa does not have nominal gender, and definiteness is not marked. Number in Zaghawa adjectives is expressed by the strategies illustrated below.

Plural number is signaled by a change in the tonal pattern on the noun and a plural suffix on the verb associated with high tone in example (22):

| bīrī | sɔ̀bɪ̀=dɔ́ | wāʊ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| dog:sg | fast:sg-def | bark-3pfv-aux-3subj-pf v:sg |

| ‘The fast dog barked’ | ||

| bīrí | sɔ̀bɪ́=dɔ́ | wāʊ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ʊ́ |

| dog:pl | fast:pl-def | bark-3pfv-aux-3subj-pf v:pl |

| ‘The fast dogs barked’ | ||

For some adjectives, in addition to the plural tonal pattern, the final vowels -i, -ɪ are replaced by -e, -ɛ as shown in (23):

| bɔ̀rʊ̂ | ɟúsì |

| man:sg | tall:sg |

| ‘Tall man’ | |

| bɔ̀rʊ́ | ɟúsé |

| man:pl | tall:pl |

| ‘Tall men’ |

Other adjectives undergo medial gemination of the intervocalic consonant in addition to the plural tonal pattern:

| èbè | ʊ́bʊ̀ɪ̀ |

| year:sg | new:sg |

| ‘New year’ | |

| èbé | ʊ́bbʊɪ́ |

| year:pl | new:pl |

| ‘New years’ | |

Number in the Zaghawa borrowed adjectives is also marked by tone as presented in the examples below:

| bɪ̀rā (sg)/bɪ̀râ (pl) – ‘maiden, maidens’ |

| mìskìn (sg)/mìskín (pl) – ‘humble person, humble people’ |

5.2 Gender marking and differences between SSA and BA borrowings

Given that gender is not a morphological category in the Zaghawa language, speakers have two options when referring to natural/biological gender in the borrowings. One option is to borrow the SSA singular form of both masculine and feminine nouns, and mark number according to the tonal class 8, which assigns HM (singular) and MH (plural) tonal patterns. Since singular feminine nouns ending in -a are tri-syllabic, a third tone is assigned to the feminine marker -a: HML (singular) and MHH (plural), see Table 20.

Morphologically integrated nouns.

| SSA | Borrowed form in Zaghawa | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |||

| SG | SG | SG | PL | SG | PL | |

| ˈustaaz-Ø | ˈustaaz-a | ústāās-Ø | ūstáás-Ø | ústāās-à | ūstáás-á | teacher, teachers |

| ˈdiktoor-Ø | ˈdiktoor-a | dáktʊ̄r-Ø | dāktʊ́r-Ø | dáktʊ̄r-à | dāktʊ́r-á | doctor, doctors |

The other option is to borrow both the singular and plural of SSA nouns with their gender and number markers, a feature which is referred to by Kossmann (2010) as parallel system borrowing. In such system “[…] morphological paradigms appear in loanwords without much (or any) influences on the native part of the lexicon” (Kossmann 2010: 460). According to Kossmann parallel system borrowing may affect nominal number marking, verbal inflection, and pronominal morphology. The nouns in Table 21 are SSA borrowings showing gender and number marking:

Parallel system borrowing.

| SSA | Zaghawa loan from SSA | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| ˈustaaz m.sg/ asaaˈtiza m.pl | ústāās m.sg/āsāātɪ́sá m.pl | teacher/s |

| ˈustaaza f.sg/ usˈtazaat f.pl | ústāāsà f.sg/ūstāsáát f.pl | teacher/s |

| ˈdiktoor m.sg/dakaaˈtira m.pl | dáktʊ̄r m.sg/dākātʊ́rá m.pl | doctor/s |

| ˈdiktoora f.sg/dikˈtooraat f.pl | dáktʊ̄rà f.sg /dāktʊ̄ráát f.pl | doctor/s |

Like Arabic borrowings in Laggori (Manfredi 2013), the Baggara Arabic feminine marker -e in borrowed nouns is the “morphophonological element that helps us to distinguish nouns borrowed from BA from those borrowed from Sudanese Standard Arabic, which typically present the feminine marker -a” (Manfredi ibid: 474). The feminine marker -e is one out of eight features that distinguish SSA from BA; the other features are listed below, and they are further exemplified in Table 22:

The /i/ in SSA is realized as [a] in BA initial syllables.

The /a/ is realized as a rather fronted [e] in BA, when it is preceded or followed by an alveolar or palatal consonant which is a productive process in BA.

Gahawa syndrome: a short vowel is inserted between two consonants at the end of one syllable and at the beginning of another (Jong et al. 2007). The inserted vowel is not necessarily /a/, and it may be subject to vowel harmony.

Bukara syndrome: “the /r/ in consonant clusters may be delayed by the insertion of an epenthetic vowel preceding the /r/” (Jong et al. 2006), as presented in BA.

Deletion: the short unstressed /a/ in open syllables is deleted in BA.

Metathesis: the process referred to as qalb in Arabic (Qāsim 2002: 15), in which two phonemes in a word are switched.

Word final Ɂimaala: Ɂimaala is a distinct feature of the variety of Arabic spoken in western Sudan which is the result of Bedouin influence (Ishaq 2002; Qāsim 2002). It refers to the process by which the final /a/ of a word is raised to /i/ or /e/ when it is preceded by a front vowel.

The feminine marker is -e in BA and -a in SSA

Features distinguishing Baggara Arabic from Sudanese Standard Arabic.

| Feature | SSA | BA | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vowel lowering i → a |

ˈniħas

ˈdiktoor ˈtifa |

ˈnahas

ˈdaktur ˈtafa |

sultan’s drums doctor head hair/skull |

| a → e |

ˈɁalif

ˈʃat ʕ t ʕ a ˈfas ʕ il |

ˈelif

ˈʃette ˈfesil |

thousand hot pepper classroom |

| Gahawa syndrome |

ˈmuswak

ˈmusmar ˈɁiblis |

ˈmusuwak

ˈmusumar ˈebilis |

damp wood used to brush teeth nail demon |

| Bukara syndrome |

ˈz

ʕ

ahri

ˈɡudra |

ˈzahar

ˈɡudara |

blue strength |

| Deletion |

ˈmasaka

taraˈbeeza ˈʕarabi ˈʕawaɟa ˈɟarada |

ˈmeske

ˈterbesa ˈarbi ˈawɟa ˈɟarda |

long net made to trap animals table from an Arab group bad news grasshopper |

| Metathesis | ˈrukab | ˈurkab | passengers |

| Word final Ɂimaala |

ˈnad

ʕ

iif(a)

ˈtaɡiil(a) ˈħalif(u) |

ˈnedifi

ˈteɡili ˈhalife |

clean (feminine) heavy (feminine) chief assistant (masculine) |

| Feminine |

ˈɡabiila

ˈmadiida ˈʕima ˈɁibra |

ˈɡebile

ˈmadide ˈime ˈibre |

clan/ tribe millet porridge turban needle |

Baggara Arabic nouns with the feminine marker -e are integrated into Zaghawa as they are, i.e., the gender morpheme is reinterpreted as part of the root. Number is marked by tone as shown in Table 23. The following group of nouns adapt the tonal patterns HML for singular and MHH for plural which is a modified version of tonal class 8 where a third tone is assigned to the feminine marker /e/.

BA borrowings ending in feminine -e.

| SSA | BA | Zaghawa loans from BA | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | SG | SG | PL | |

| ˈsafiina | ˈsefine | séfīnè | sēfíné | ship |

| ˈɡabiila | ˈɡebile | ɡɛ́bɪ̄lɛ̀ | ɡɛ̄bɪ́lɛ́ | tribe |

| ˈmadiina | ˈmedine | médīnè | mēdíné | town |

5.3 Verbs

The verbal morphology of Arabic presents many inflected forms. Verbs in Arabic are generally inflected for person, number and tense; further inflections may occur. At this point it is difficult to assess which stem of the Arabic verbal system is borrowed. The Arabic verb stem, regardless of which stem is borrowed, is completely integrated into the morphological and tonal system of Zaghawa.

The Zaghawa verb is inflected for person, number, and TAM. According to Aldawi (2017: 41–49), four verb classes (labeled A, B, C, D) have been distinguished in Zaghawa based on the model of their conjugation. The most productive verb classes in all Saharan languages are class C[3] and class D.[4] There are two major differences between verbs of these two groups that are important to outline; Class C verbs are transitive verbs whereas class D verbs are intransitive. Both verb classes consist of a root providing the lexical meaning and an auxiliary -l-, functioning as a light verb. Compare the class C verb in example (26) and the class D verb in (27):

| [bɛ̀ɡɛ̀ɪ̀ɡɪ̄lɪ́] |

| bɛ̀ɡɛ̀ɪ̀-kɪ̄-l-ɪ́ |

| travel-3pfv-aux:pfv-sg.aff |

| ‘S(he) has traveled’ |

The auxiliary -l- has a suppletive form [ɛ] or [e] that appears with the 1st and 2nd person singular and plural of class C verbs. The morpheme -kɪ- marking 3rd person in the perfective aspect for class B verbs is realized as [-ɡɪ] in class C verbs, cf. example (26). The 3rd person subject morphemes -r, -Ø are null morphemes in the perfective and imperfective aspects, for more information see Aldawi (2017: 41–49).

Class D verbs are characterized by the presence of an object morpheme preceding the auxiliary, and a subject morpheme. Accordingly, the order of the morphemes in a class D verb is the following: the lexical morpheme, an obligatory object morpheme, the auxiliary -l-, and a dummy third person subject morpheme. The auxiliary takes a different form in the perfective and imperfective, cf. examples (26) and (28):

| mɪ̄ɛ̄-tɛ̄-ʃɪ̄-r-ɛ́ |

| black-1obj:pl-aux.ipfv-3subj-ipfvː1pl.incl |

| ‘We will become black’ |

The lexical information in the verbs of classes C and D may be provided by an Arabic borrowing. The Arabic stem is fully integrated into Zaghawa morphology and tonology. This accommodation strategy is called by Muysken (2000) and by Wohlgemuth (2009: 21) “nominalization”, and it consists of a borrowed lexeme treated like a noun in a construction like “do x”. Arabic verbs are borrowed and conjugated according to the model of class C and D.

Tables 24 and 25 show the integration of Arabic verbs in the Zaghawa verbal morphology and tonology. There is a systematic pattern of vowel harmony and vowel insertion in ɡɛ̀rɪ̀-l-ɛ́, kɛ̀tɪ̀bɪ̀-l-ɛ́, fɛ̀ttɪ̀ʃɪ́-l-ɛ̀, wɛ̀ddɪ̀-l-ɛ̄, sɛ̀kkɪ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-ɪ́, sɛ̀llɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-ɪ́, fèkkìr-ɡī-l-í, and hèmì-ɡī-l-í where the first inserted vowel is always e, ɛ ±atr and the following vowels are i, ɪ ±atr.

SSA verb stems conjugated in the imperfective aspect according to class C.

| SSA stem | SSA morphology IPFV | Borrowed form | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | lm-aux-3subj-ipfv | ||

| ˈɡara | ˈtaɡara | ˈjaɡara | ɡɛ̀rɪ̀-l-Ø-ɛ́ | (s)he reads |

| ˈkatab | ˈtaktib | ˈjaktib | kɛ̀tɪ̀bɪ̀-l-Ø-ɛ́ | (s)he writes |

| ˈʕaaliɟ | ˈtaʕaaliɟ | ˈjiʕaaliɟ | ààlɪ̀ɟɪ̀-l-Ø-ɛ́ | (s)he/it treats |

| ˈfattiʃ | ˈtafattiʃ | ˈjifattiʃ | fɛ̀ttɪ̀ʃɪ́-l-Ø-ɛ̄ | (s)he/it searches for something |

| ˈwad ʕ dˤu | ˈtitwadˤdˤa | ˈjatwadˤdˤa | wɛ̀ddɪ̀-l-Ø-ɛ̄ | (s)he/it performs ritual ablution |

| ˈʃukur | ˈtaʃkur | ˈjaʃkur | ʃʊ̀kʊ̀r-l-Ø-ɛ̄ | (s)he/it is thankful |

The exceptions to the previous pattern are the verbs ʃʊ̀kʊ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-ɪ́ in which the dominant vowel in both syllables is /ʊ/; this vowel appears in both syllables of the stem ˈʃukur. Similarly, sàʊ̀ɡɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-ɪ́ is the result of the replacement of the VCV combination [awu] in ˈtasawuɡ by the diphthong [aʊ] in Zaghawa (cf. Table 12). A further exception is the stem ˈʕaaliɟ which is borrowed as ààlɪ̀ɟɪ̀-l-ɛ́ and ˈwas ʕ s ʕ a borrowed as wàssà-ɡɪ̄-l-ɪ́ where no changes are made to the stems.

The borrowed verbs in Table 24 are in the imperfective aspect, but when conjugated in the perfective, the borrowings follow the same morphological rules which apply to Zaghawa verbs: the borrowed verb stem is marked with a low tone and the auxiliary with TAM [-ɡɪlɪ] is suffixed with a M/H tonal pattern, which is the same tone marking of non-borrowed Zaghawa verbs. Consider the examples in Table 25:

SSA verb stems conjugated in the perfective aspect according to class C.

| SSA stem | SSA morphology PFV | Borrowed fotm | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | lm -obj-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv | ||

| ˈkatab | ˈkatab-at | ˈkatab | kɛ̀tɪ̀bɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ | (s)he wrote |

| ˈsikkir | ˈsikkir-at | ˈsikkir | sɛ̀kkɪ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ | (s)he got drunk |

| ˈtasawuɡ | ˈitsawaɡ-at | ˈitsawaɡ | sàʊ̀ɡɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ | (s)he shopped |

| ˈs ʕ alla | ˈs ʕ alla-t | ˈs ʕ alla | sɛ̀llɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ | (s)he prayed |

| ˈfikkir | ˈfakkar-at | ˈfakkar | fèkkìr-ɡī-l-Ø-í | (s)he thought |

| ˈʃukur | ˈʃakar-at | ˈʃakar | ʃʊ̀kʊ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ | (s)he was thankful |

| ˈwas ʕ s ʕ a | ˈwas ʕ s ʕ -at | ˈwas ʕ s ʕ a | wàssà-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ | (s)he asked people for a favor |

| ˈfihim | ˈfihm-at | ˈfihim | hèmì-ɡī-l-Ø-í | (s)he understood |

Consider the SSA morphology for the verb ˈnaɟaħ ‘succeeded’ and compare it to the Zaghawa morphology of class D verbs in the perfective and imperfective; the final /ħ/ is elided following the consonant elision rule of the voiceless pharyngeal fricative, the remaining verb stem is borrowed and conjugated according to the model of class D verbs:

| naɟaħ-ˈt-a |

| succeed-past-1sg |

| ‘I succeeded’ |

| nàɟàɪ̄-ɛ́-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| succeed-obj-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv |

| ‘I succeeded’ |

| naɟaħ-ˈt-u |

| succeed-past-2pl:m |

| ‘You succeeded’ |

| nàɟàɪ̄-lɛ́-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ǔ |

| succeed -obj-aux-3subj-ipfv |

| ‘You succeeded’ |

Borrowed verbs, regardless of which stem is borrowed, are integrated in the Zaghawa system with phonological and morphological modifications. Borrowed verbs follow the conjugation of class C or D.

5.4 Verbal nouns

Nouns can be derived from verbs in the Zaghawa language by a derivative affix acting as a nominalizer. The form of this affix depends on the verbal class. Class A verbs are derived by the suffix -la as illustrated below:

| ʃɪ̄-ɡɛ̄-r-ɛ̀ |

| caus-sleep-3subj-ipfv |

| ‘S/he sleeps’ |

| ɛ̄ɡɛ̄-là |

| sleep- nmlz |

| ‘Sleeping’ |

The verbs of class B have three different affixes used to derive verbal nouns: (V)C, (V)kk(V), and the infix -k-, consider examples (31), (32) and (33):

| kʊ̄-tɔ̄-l-ɪ́ |

| 3pfv-taste -3subj-3pfv |

| ‘She tasted it’ |

| ɔ́t-tɔ̀ |

| nmlz-taste |

| ‘Tasting’ |

| kɪ̄-jā-r-ɪ́ |

| 3pfv-drink-3subj-pfv |

| ‘He drank it’ |

| ākkā-yà |

| nmlz-drink |

| ‘Drinking’ |

| k-ʊ̀fɛ̀-l-ɪ̌ |

| 3pfv-beg-3subj-3pfv |

| ‘She begs’ |

| ʊ̀f-k-ɛ̄ |

| beg-nmlz-root vowel |

| ‘Begging’ |

Verbal nouns derived from class C verbs take the nominalizer suffix -di. In the derivation of verbal nouns of class C, the auxiliary typical of class C verbs is replaced by the suffix -di; this suffix is either preceded by a vowel, or a sonorant consonant. Consider the examples (34) and (35) below:

| ɡɪ̀lmɛ̀ɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| dream-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv |

| ‘He dreamed’ |

| ɡɪ̀lmɛ̀ɪ̀-dɪ́ |

| dream-nmlz |

| ‘Dreaming’ |

| kʊ̄rā-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| wash-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv |

| ‘She washed’ |

| kʊ̄rā-dɪ́ |

| wash-nmlz |

| ‘Washing’ |

Nominalization is productive in Arabic and in SSA. Zaghawa does not take over Arabic verbal nouns, but instead, applies Zaghawa nominalization rules to the Arabic borrowed stems. Consider the Arabic verb stems (ʔal)ɡiˈraaja ‘reading’ in example (36), (ʔal)ˈs ʕ alla ‘praying’ (37) and (ʔal)ʃuˈkur ‘thankfulness’ in (38) that have been conjugated according to the model of class C verbs: the formation of the verbal nouns is based on replacing -ɡɪ̄lɪ́ by the nominalizer -di with a high tone.

| ɡɛ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| read-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv |

| ‘He read’ |

| ɡɛ̀rɪ̀-dɪ́ |

| read-nmlz |

| ‘Reading’ |

| sɛ̀llɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| pray-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv |

| ‘She prayed’ |

| sɛ̀llɪ̀-dɪ́ |

| pray-nmlz |

| ‘Praying’ |

| ʃʊ̀kʊ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄-l-Ø-ɪ́ |

| thank-3pfv-aux-3subj-pfv |

| ‘He was thankful’ |

| ʃʊ̀kʊ̀rɪ̀-dɪ́ |

| thank-nmlz |

| ‘Thankfulness’ |

6 Conclusions

The types of borrowings found in Zaghawa are both cultural borrowings (Haspelmath 2009: 46), and core borrowings that duplicate, or replace, existing words. The Zaghawa language has borrowed from SSA, e.g., kɪ̀tāp < kiˈtaab ‘book’, as well as from BA, e.g., mèdìnē < ˈmadina ‘city’.

Judging from our analysis of Arabic borrowings (see Appendix), these words are integrated in Zaghawa nominal and verbal morphology, and they are phonologically and prosodically integrated too.

This study has presented and analyzed the phonological and morphological processes by which Arabic words are integrated into Zaghawa. Phonological integrations involve consonant adaptation, vowel integration, vowel shortening, syllable adaptation, gemination. The study reached the conclusion that there is no correlation between stressed syllables in SSA and BA and high tone in Zaghawa.

Morphological integration involves various processes; nouns are integrated into the nominal morphology of Zaghawa by tonal morphemes indicating number: tonal class 8 has been modified to accommodate the syllable structure of the borrowed feminine nouns. Nouns borrowed from BA are integrated with the feminine marker -e as part of the root; the plural is then distinguished for number by tone.

When referring to biological gender in the Zaghawa borrowings, there are two possibilities: borrowing only the singular form of both masculine and feminine nouns with the gender and number suffixes treated as part of the root; in this case the tone is used to mark number; the other possibility is to borrow both the singular and the plural forms of both the masculine and feminine with the gender and number suffixes being part of the root.

Adjectives are also mentioned. Arabic gender and definiteness agreement are not applied to the Zaghawa borrowings; instead, borrowed adjectives are marked for number by a tonal morpheme. The indefinite article -lɪ is suffixed to borrowed adjectives.

As far as verbal morphology is concerned, the decision on which Arabic verbal stem is borrowed has not been made and further investigation is needed. Borrowed verbal stems regardless are conjugated according to the modal of verbal classes C and D. Borrowed verb stems can be nominalized by means of the suffix -di of class C verbs.

Abbreviations

- 1

-

first person

- 2

-

second person

- 3

-

third person

- <

-

greater-then

- adj

-

adjective

- adv

-

adverb

- AFF

-

affirmative mood

- APPL

-

applicative

- ATR

-

advanced tongue root

- AUX

-

auxiliary

- C

-

consonant

- COP

-

copula

- DEF

-

definite article

- DEM

-

demonstrative

- excl

-

exclusive

- H

-

high tone

- IMP

-

imperative

- INCL

-

inclusive

- IPFV

-

imperfective aspect

- L

-

low tone

- LM

-

lexical morpheme

- M

-

mid tone

- n

-

noun

- NEG

-

negative

- NMLZ

-

nominalizer

- OBJ

-

object

- PART

-

particle

- PFV

-

perfective aspect

- PL

-

plural

- POST

-

postposition

- PP

-

personal pronoun

- PROG

-

progressive

- SG

-

singular

- SUBJ

-

subject

- V

-

vowel

- v

-

verb

- vn

-

verbal noun

Acknowledgments:

I would like to thank Elsadig Omda for his generous collaboration and support during the fieldwork for this study. My sincere thanks are due to Gertrude Schneider Blum for reviewing this work several times. I also dearly appreciate the support of Prof. Alamin Abu-Manga in reviewing this work and all his insightful comments. I thank the two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their constructive remarks that contributed to improving it. I dedicate this work to all the Zaghawa speakers of the Sudan.

-

Research ethics: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

-

Informed consent: A verbal informed consent was obtained from the consultants for the data to be published in this article.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Appendix: List of Arabic loans in Zaghawa

| Zaghawa loan | Arabic | English translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ɟámɛ̄ (n) | ˈɟaamiʕ | Mosque |

| 2. | sɛ̀llɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | ˈsʕalli | pray! |

| 3. | wɛ̀ddɪ̀-lɛ̄ (v) | Ɂitˈwadʕdʕa | perform ritual ablution! |

| 4. | hɔ̀ɡɪ̄ (n) | faˈɡiih | ritual person |

| 5. | dʊ́wà (n) | ˈduʕa | prayer |

| 6. | sēbbē (n) | ˈsibħa | Beads |

| 7. | nèbī (n) | ˈnabi | prophet |

| 8. | hàɟī (n) | ˈħaaɟ | one who has made it to the pilgrimage |

| 9. | àlfítrí (n) | Ɂalˈfitʕr | end of Ramadan feast |

| 10. | sʊ̄k (n) | ˈsuɡ | market |

| 11. | sàʊ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | Ɂitˈsawag | shop! |

| 12. | ɡɪ̀rɪ̌ʃ (n) | ɡuˈruuʃ | money |

| 13. | dēn (n) | ˈdeen | Debt |

| 14. | ɡɛ́bɪ̄lɛ̀ (n) | ɡaˈbiila | clan/tribe |

| 15. | sʊ̀ltǎn (n) | sulˈtʕan | lordship |

| 16. | ābà (n) | ˈɁab | Father |

| 17. | kálwà(n) | ˈxalwa | Qur’anic school |

| 18. | tāālɪ̀p (n) | ˈtʕaalib | student |

| 19. | ústāās (n) | usˈtaaz | teacher |

| 20. | hɪ̀sāb (n) | ˈħisab | counting |

| 21. | kɪ̀tāp (n) | kiˈtab | Book |

| 22. | kɛ̀tɪ̀bɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | Ɂakˈtib | write! |

| 23. | nàɟàɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | Ɂanˈɟaħ | succeed! |

| 24. | ɡɛ̀rɪ̀-lɛ̄ (v) | Ɂaˈɡra | read! |

| 25. | hèmì-ɡɪ̄lí (v) | Ɂafˈham | understand! |

| 26. | hɪ́ssà (n) | ˈħisʕsʕa | Lesson |

| 27. | ɟʊ́wàb (n) | ˈɟawab | Letter |

| 28. | kʊ̀bbáɪ̀ (n) | kubˈbaaya | Glass |

| 29. | kúrsì (n) | ˈkursi | Chair |

| 30. | ɔ́dà (n) | ˈʔoodʕa | Room |

| 31. | tɛ́rbɛ̄sà (n) | tʕaraˈbeeza | Table |

| 32. | mòrwâ (n) | ˈmarwaħa | Fan |

| 33. | údú (n) | ˈʕuud | Stick |

| 34. | ɡɪ́làm (n) | ˈɡalam | Pen |

| 35. | mʊ̀sʊ̀mâr (n) | ˈmusmar | Nail |

| 36. | kʊ́ràs (n) | ˈkuras | notebook |

| 37. | sân (n) | ˈsʕaħan | plait |

| 38. | íbrè (n) | ˈɁibra | needle |

| 39. | mʊ̀sʊ̀wâk (n) | ˈmuswak | dampy wood used to brush teeth |

| 40. | húl (n) | ˈfuul | beans |

| 41. | tūm (n) | ˈtuum | garlic |

| 42. | ʃájɛ̀ (n) | ˈʃaaj | Tea |

| 43. | ʃɛ́ttɛ̀ (n) | ˈʃatʕtʕa | hot pepper |

| 44. | bùrtùkān (n) | ˈburtukan | orange |

| 45. | bʊ́nʊ̀ (n) | ˈbun | coffee |

| 46. | sʊ́kkàr (n) | ˈsukkar | sugar |

| 47. | ásāllījà (n) | ʕasalˈliija | millet drink |

| 48. | mádīdè (n) | ˈmadida | millet porridge |

| 49. | ēēʃ (n) | ˈʕeeʃ | bread |

| 50. | bɔ́sɔ̀l (n) | ˈbasʕal | onion |

| 51. | lómùn (n) | ˈleemun | lemon |

| 52. | màràrà (n) | ˈmaɽaɽa | food consisting of liver and intestines |

| 53. | káwàl (n) | ˈkawal | wild grain |

| 54. | átrʊ̂n (n) | ˈʕatʕrun | mineral salt |

| 55. | àràɡɪ̄ (n) | ˈʕaraɡi | alcohol |

| 56. | sɛ́nɛ̄ (n) | ˈsana | year |

| 57. | hāssāɡá (adv) | ˈhassa | now |

| 58. | sāà (adv) | ˈsaʕa | hour |

| 59. | hɪ̄nɪ̄ (adv) | ˈhini | here |

| 60. | árbáhà (n) | ˈɁarbiʕa | Wednesday |

| 61. | sábɪ̄t (n) | ˈsabit | Saturday |

| 62. | tálátà (n) | ˈtalata | Tuesday |

| 63. | bárɪ̄yè (adv) | ˈbarħa | yesterday |

| 64. | hɔ̀rtʊ̄m (n) | ˈxartʕum | Khartoum |

| 65. | médīnè (n) | ˈmadiina | city |

| 66. | sʊ̀bʊ̀ (n) | ˈsʕubuħ | morning |

| 67. | màgrèb (adv) | ˈmaɣrib | sunset |

| 68. | ɪ́ʃɪ̄nà (adv) | ˈʕiʃa | time after sunset until 9 o’clock |

| 69. | āʃārà (n) | ˈʕaʃara | ten |

| 70. | ɛ́lɪ̀f (n) | ˈʔalif | thousand |

| 71. | árbátáʃàr (n) | ˈɁarbaʕtʕaʃar | fourteen |

| 72. | mɪ̂ (n) | ˈmijja | hundred |

| 73. | tʊ́ɟáràɪ̀ (n) | ˈtuɟar | merchants |

| 74. | térsì (n) | ˈtarzi | tailor |

| 75. | dáktʊ̄r (n) | dikˈtoor | doctor |

| 76. | séfīnè (n) | saˈfiina | boat |

| 77. | ɡɑ̀tɑ̀r (n) | ˈɡatʕar | train |

| 78. | ɑ̀ràbéì (n) | ʕarabˈbija | Car |

| 79. | tɑ̀jjɑ̀r (n) | ˈtʕajˈjaara | airplane |

| 80. | sāffār (adj) | ˈɁasʕffar | yellow |

| 81. | zāhār (adj) | ˈzʕahri | blue |

| 82. | tɛ́ɡɪ̄lɪ̀ (adj) | taˈɡiil(a) | heavy |

| 83. | sɪ́ràn (adj) | ˈsaʕran | mentally ill |

| 84. | mìskìn (adj) | ˈmiskiin | poor |

| 85. | kàfɔ̄ (adj) | kaˈfiif | blind person |

| 86. | àrbɪ̀ (n) | ˈʕarabi | from an Arab group |

| 87. | hūt (n) | ˈħuut | fish |

| 88. | nâl (n) | ˈnaħal | bees |

| 89. | tōb (n) | ˈtob | woman’s traditional dress |

| 90. | ímè (n) | ˈʕima | turban |

| 91. | ɡāʃ (n) | ˈɡaaʃ | belt |

| 92. | súwwâr (n) | ˈsuwwar | rebels |

| 93. | hʊ̀rɪ̀jē (n) | ˈħurija | liberty |

| 94. | fɛ̀sɪ̀l (n) | ˈfasʕil | classroom |

| 95. | hābàr(n) | ˈxabar | news |

| 96. | báhàr (n) | ˈbaħar | lake |

| 97. | tɪ́màtɪ̀m (n) | tʕaˈmaatʕim | tomato |

| 98. | dɔ́rʊ́rɪ̀ (adj) | ˈdʕaruri | important |

| 99. | áwɟà (n) | ˈʕawaɟa | bad news |

| 100. | hádìd (n) | ˈħadiid | iron |

| 101. | dɛ́hɪ̄jɛ̀ (n) | dʕaˈħija | slaughter of animals for a religious ritual |

| 102. | sɔ́bʊ̀r (n) | ˈsʕabur | patience |

| 103. | ɡálbānè (adj) | ɣalˈbaana | pregnant woman |

| 104. | ɡálì (adj) | ˈɣali | expensive |

| 105. | tɪ́msà (n) | ˈtumsaaħ | crocodile |

| 106. | mèské (n) | masˈsaka | long net made to trap animals |

| 107. | māáɟʊ̂m (adj) | ˈmaħaɟum | one who has been cupped |

| 108. | dâb (n) | ˈdahab | gold |

| 109. | kàfɔ̄ (adj) | ˈkafif | blind |

| 110. | tâm (n) | ˈtʕaʕam | taste |

| 111. | márābbà (adj) | ˈmurabbaʕ | square |

| 112. | ēb (n) | ˈʕeeb | shame |

| 113. | móɡōf (n) | ˈmogaf | station |

| 114. | tàjjàr (n) | tʕ ajˈjaara | plane |

| 115. | ékràm (adj) | ˈɁakram | very generous/ respectful |

| 116. | jàmjàm (n) | ˈtajammum | ablution with rock or sand |

| 117. | úrkàb (n) | ˈrukab | passengers |

| 118. | bɪ̀rā (adj) | ˈbajra | maiden |

| 119. | āhàl (n) | ˈɁahal | family |

| 120. | ɟār (n) | ˈɟar | neighbor |

| 121. | ɪ́lɪ́m (n) | ˈʕilim | knowledge |

| 122. | háyà (n) | ˈħaya | life |

| 123. | ámàn (n) | ˈɁaman | peace |

| 124. | sʊ̀ltǎn (n) | ˈsʕultan | lordship |

| 125. | wákìl (n) | waˈkiil | one in charge |

| 126. | ààlɪ̀ɟɪ̀-lɛ́ (v) | ʕiˈlaaɟ | treatment |

| 127. | fɛ̀ttɪ̀ʃɪ̀-lɛ́ (v) | ˈfattiʃ | search! |

| 128. | sɛ̀kkɪ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | ˈɁaskkar | be drunk! |

| 129. | fèkkɪ̀r-ɡīlí (v) | ˈfikkir | thinking! |

| 130. | ʃʊ̀kʊ̀rɪ̀-ɡɪ̄lɪ̄ (v) | ˈɁaʃkur | be thankful! |

| 131. | tʊ̀f-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | ˈtuf | spit! |

| 132. | wàssà-ɡɪ̄lɪ́ (v) | ˈwasʕsiʕ | ask people for a favor! |

| 133. | yōm (n) | ˈyoom | day |

| 134. | làkɪ́n (conj) | laˈkin | but |

| 135. | fàrànɪ̂ (adj) | ˈfarħan | happy |

| 136. | ə́nɡàrɛ̄p (n) | ˈʕənɡareeb | traditional bed |

| 137. | náwàr (n) | ˈnuwar | flowers |

| 138. | bʊ́ɡɪ̄jà (n) | ˈbuhja | paint |

| 139. | tábāānè (adj) | taʕˈbaana | distressed |

| 140. | díjà (n) | ˈdiija | price paid to preserve the life of a murderer |

| 141. | sʊ́wà (n) | ˈsuwa | mess |

| 142. | lʊ́bàn (n) | ˈluban | gum |

| 143. | ɡʊ̄tʊ̄n (n) | ˈɡutʕun | cotton |

| 144. | símì (n) | ˈsim | poison |

| 145. | ámīnà (n) | ˈɁamina | female camel |

| 146. | áwnà (adj) | ˈʕawna | stand up straight |

| 147. | násārà (n) | naˈsʕara | foreigners with different religion and skin color |

| 148. | wárāɡà (n) | ˈwaraɡa | amulet |

| 149. | dēl (n) | ˈzel | penis |

| 150. | ásìda (n) | ʕaˈsʕida | porridge |

| 151. | bárāndà (n) | ˈbaranda | an open space in the house |

| 152. | dáwlà (n) | ˈdawla | country |

| 153. | tʊ́rbà (n) | ˈturba | grave/soil |

| 154. | ɟɪ̀rʊ́f (n) | ˈɟuruf | entrance to a wadi |

| 155. | fōtōr (n) | ˈfatʕur | first meal of the day |

| 156. | ɡōbōr (n) | ˈɡabur | grave |

| 157. | hádīyè (n) | haˈdiiya | gift |

| 158. | ɪ́brɪ̂k (n) | ˈɁibriɡ | plastic kettle |

| 159. | sēf (n) | ˈseef | sword |

| 160. | màrkúb (n) | marˈkoob | leather shoe |

| 161. | ɟɪ́slân (n) | ˈɟuzlan | wallet |

| 162. | sʊ́rwàl (n) | ˈsirwal | pants |

| 163. | kárkābà (n) | raˈkuba | temporal house |

| 164. | máhàr (n) | ˈmahar | dowry |

| 165. | náhàs (n) | ˈniħas | drums |

| 166. | kórā (n) | ˈkorah | bowl |

| 167. | hámɪ̀s(n) | xaˈmiis | Thursday |

| 168. | ɟōb (n) | ˈɟeb | |

| 169. | kórēk (n) | ˈkorek | shovel |

| 170. | hʊ́làl (n) | ˈxulal | comb |

| 171. | márkābà (n) | ˈmurkab | boat |

| 172. | nédífì (adj) | naˈdʕiif(a) | clean |

| 173. | ámbātà (n) | hamˈbata | bandits |

| 174. | hàràmɪ́ (n) | ˈħarami | theif |

| 175. | óɟúwààt (n) | Ɂaɟaˈwiid | elders of the village called to settle disputes |

| 176. | sáɡʊ̄r (n) | ˈsʕaɡur | hawk |

| 177. | táfà (n) | ˈtɪfa | head hair/ skull |

| 178. | rámádàn (n) | ramaˈdaan | Islamic month of fasting |

| 179. | tàbírí (n) | taʕˈbiir | expression |

| 180. | wáfā (n) | waˈfaa | funeral |

| 181. | àtɪ̀já (n) | ʕaˈtʕija | gift |

| 182. | bárkà (n) | ˈbaraka | good fortune |

| 183. | dār (n) | ˈdaar | homeland |

| 184. | dáwà (n) | ˈdawa | medicine |

| 185. | ebīlīs (n) | Ɂibˈliis | demon |

| 187. | fátíyē (n) | ˈfatħa | the first chapter of the Quran/blessing/ prayer |

| 188. | ɡʊ́dārà (n) | ˈɡudra | strength |

| 189. | hàdím (n) | huˈduum | clothes |

| 190. | hálīfè (n) | ˈħalif(u) | chief assistant |

| 191. | íʃé (n) | ˈʕaʃa | dinner/meal |

| 192. | ɟínè (n) | ˈɟineh | Sudanese money |

| 193. | kárò (n) | ˈkaru | horse cart |

| 194. | kéhèn (n) | ˈkafan | shroud |

| 195. | sʊ́stà (n) | ˈsusta | zipper |

| 196. | ɟàrdā (n) | ˈɟarada | grasshopper |

| 197. | mándòb (n) | manˈdoob | delegate |

| 198. | néfér (n) | ˈnafar | person |

| 199. | ówìr (n) | ˈʕawir | plant with purple flower |

| 200. | sàndók (n) | sʕanˈdooɡ | box |

| 201. | nàɟín (n) | naˈɟiin | refugees |

| 202. | sɪ̀dák (n) | sʕaˈdaɡ | portion/ dowry |

| 203. | tɪ́kà (n) | ˈdika | belt |

| 204. | tɪ́ʃà! (v) | ˈhiʃu! | drive animals away |

References

Abu-Manga, Al-Amin. 1999. Hausa in the Sudan: Process of adaptation to Arabic. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.Suche in Google Scholar

Aldawi, Maha A. 2010. The morpho-syntactic structure of the Zaghawa language. University of Khartoum, PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Aldawi, Maha A. 2017. Morpho-syntactic structure of the Zaghawa verbs. Revue Scientifique du Tchad, Centre National De Recherche Pour Le Développement- Chad. Série A. 39–63.Suche in Google Scholar

Casciarri, Barbara & Stefano Manfredi. 2009. Dynamics of adaptation to conflict and to political and economical changes among the Hawazma Pastoralists of Southern Kordofan (Sudan): An insight through process of education. Paper presented at the 15th Congress of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, Kunming; China 27–31 July.Suche in Google Scholar

Clements, George N. 2000. Phonology. In Bernd Heine & Derek Nurse (eds.), African languages: An introduction, 123–159. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Dimmendaal, Gerrit J., Colleen Ahland, Angelika Jakobi & Constance Kutsch Lojenga. 2019. Linguistic features and typologies in languages commonly referred to as ‘Nilo-Saharan. In H. Ekkehart Wolff (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of African linguistics, 326–381. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108283991.011Suche in Google Scholar

Doornbos, Paul. 1989. Language use in western Sudan. In Marvin Lionel Bender (ed.), Topics in Nilo-Saharan linguistics, 425. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Greenberg, Joseph. 1962. The study of language contact in Africa. Colloque sur le Multilinguisme. Brazzaville, 168.Suche in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 2009. Lexical borrowing: Concepts and issues. In Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor (eds.), Loanwords in the World’s languages: A comparative handbook. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110218442Suche in Google Scholar

Hoile, David. 2008. Darfur: The road to peace, 3rd edn., 13. London: The European-Sudanese Public Affairs Council.Suche in Google Scholar