Abstract

This paper discusses the different syntactic status of the prenominal marker a in three languages spoken in Burkina Faso and neighbouring countries (Dagara, Mooré and Koromfe) and its respective relation to the determiner system. We argue that the marker is a head-initial determiner in Dagara, a proprial article in Mooré and a nominal expletive in Koromfe and tentatively suggest a possible common pronominal origin. The paper also addresses further points of variation in the higher nominal structure of the three languages concerning DP directionality and the co-occurrence of determiners, demonstratives and possessors, providing a basis for future wider investigations across the Mabia/Gur family.

Dagara abstract

A sεbε ƞan na wiili na a lε a ƴεr-bir pu-tuuro ‘lan bà nà bʊɔllε ka “prenominal marker a” a ãglε kɔkɔr nan ƞmεn a Burkina kɔkɔε minε pʊɔ. Tὶ bέlɩ na a “prenominal marker a” ƞaarʊ a Dagara kɔkɔr pʊɔ, a Mɔɔsi kɔkɔr pʊɔ, ni a Korõfe kɔkɔr pʊɔ. Tὶ yεrε wiili na a lε ʊlε ni a ƴεr-bir ‘lan bà nà bʊɔllε ka “noun” nan nyɔw taa. Tὶ yèlla ka “a”, a Dagara kɔkɔr pʊɔ, ɩ-n ƴεr-bir pu-tuuro nan mɩ be puori (“head-initial determiner”). A Mɔɔsi kɔkɔr pʊɔ, ʊ ɩ nir-yuo pu- tuuro (“a proprial article”). ‘Lan wa be a ƴεr-bir puori nan, a wùla ka a ƴεr-bir ‘lan ɩ-n nir-yuo. A Korõfe kɔkɔr pʊɔ, tὶ yèlla ka a ƴεr-bir pu-tuuro ‘lan (a “a”) ba tεr par ε; ʊ ɩ-n na zi-guuro na. ʊ mɩ be na a be a “noun” nan ti sεw k’ʊ be na ti ba tεr “meaning” ε. A sεbε ƞan pʊɔ, tὶ mán na a lε a “noun” ƴεr-bir ni a ʊ pu-tuuro ƃã-taa nan ƞa-taa bii ba ƞa-taa-ɩ a Dagara kɔkɔr pʊɔ, a Mɔɔsi kɔkɔr pʊɔ, ni a Korõfe kɔkɔr pʊɔ. A sεbε ƞan nan sõw na a ni-bε bala ‘ha nan tʊnɔ ni a Afriki kɔkɔε ala bà nà bʊɔllε ka “Mabia/Gur language family.”

1 Introduction

This paper investigates crosslinguistic variation in nominal structure within the Mabia/Gur[1] language family (Niger-Congo phylum) in West Africa with an empirical focus on three languages spoken in Burkina Faso (and neighbouring countries): Dagara Wulé[2] (Glottolog code nort2780/wule1238, Hammarström et al. 2021), Mossi/Mooré (moss1236) and Koromfe (koro1298). Our primary aim is to compare the different syntactic distributions of the prenominal morpheme a found in all three languages, see (1). Additionally, we discuss properties of the determiner system in these languages highlighting common patterns and points of variation, particularly concerning the interaction with demonstratives and possessors.

| A | pʋalé | zɔ̀-rɔ̀ | na. | Dagara |

| det | boy | run-ipfv | aff | |

| The boy is running.’ | ||||

| A | Madou | yíídàme. | Mooré |

| art | Madou | sing.ipfv | |

| ‘Madou is singing.’ | |||

| A | vaga | koŋ | bɛ. | Koromfe |

| art | dog.sg | det.nhum.sg | come | |

| ‘The dog came/comes (back).’ | after Rennison 1997: 12, (6) |

We argue that prenominal a in Dagara is a determiner heading a head-initial DP, contrasting in head-directionality with the postnominal determiners attested in Mooré and Koromfe (and many other Mabia/Gur languages). The Mooré cognate of prenominal a is distinct from the postnominal determiners in that language and is best analysed as a proprial article due to its restriction to proper names. In Koromfe, prenominal a functions as a nominal expletive that fills the prenominal possessor position for formal (syntactic or phonological) reasons. With respect to nominal structure we further observe that Dagara and Mooré have distinct syntactic positions for determiners and demonstratives, while these word classes compete for the same position in Koromfe. In all three languages determiners and possessors can co-occur within the same extended nominal projection. Our main empirical findings are summarised in Table 1, for a more detailed comparison see Section 6.

Summary of observed variation in nominal structure.

| Dagara | Mooré | Koromfe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prenominal a | Determiner | Proprial article | Nominal expletive |

| DP head-directionality | Left | Right | Right |

| Distinct det and dem | Yes | Yes | No |

| Co-occurrence of DET and possessors | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Our syntactic analyses are framed in terms of the Minimalist Program (Chomsky 1995; 2001) within the Principles & Parameters framework, but most empirical contributions of the paper do not depend on the specifics of that theoretical model and should be accessible to researchers working in different frameworks. Most of the data from Mooré and Dagara presented here are new, while the Koromfe data are largely based on Rennison (1997; 2022).

The article is structured as follows. The next section provides a brief linguistic overview of Dagara, Mooré and Koromfe and the sources of the data reported here. In Sections 3–5, we present the syntactic behaviour of prenominal a for each language in turn, discussing their interaction with demonstratives, possessors and – where distinct from prenominal a – determiners in support of the conclusions stated above. We summarise and compare the observations and our proposed analyses of nominal syntax across the three languages in Section 6 along with some deliberations concerning a common historical source for prenominal a. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2 Language and data overview

This section provides an overview of the languages under discussion and the sources of the language data used in the paper.

2.1 Language context

Figure 1 indicates approximate geographic locations for the three languages under discussion, although particularly Mooré and Dagara are spoken in wider areas. The coordinates for Dagara and Koromfe are based on Glottolog (Hammarström et al. 2021) and those for Mooré on WALS (Dryer & Haspelmath 2013). Our empirical data is based on speakers of these languages from Burkina Faso.

Map of Burkina Faso and the languages under investigation.

Mooré, also referred to as Mossi or Moshi, is spoken by more than 8 million people in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Cote d’ Ivoire, Mali and Togo (see Kropp Dakubu 2015; Zongo 2004; Pitroipa 2008; Compaoré 2017; Eberhard et al. 2019). It is one of the dominant languages in Burkina Faso, reportedly natively spoken by around 50 % of the population (Eberhard et al. 2019) and also used by a good number of Burkinabe as a second/third language. This includes many native speakers of the other two languages discussed here, cf. Rennison (1997: 203) for Koromfe. Given its widespread use throughout Burkina Faso, its location on the map is of limited significance.

Dagara is a developing language (i.e. neither endangered nor moribund) with an estimated 1.5 million speakers (Beyogle 2015; Dansieh 2008; Kuba and Lentz 2001; Mwinlaaru 2017). It is spoken in the south-west of Burkina Faso, the north of Ghana and the north-east of Cote D’Ivoire. At least southern, central and northern varieties are distinguished (Beyogle 2015; Bodomo 1997; Eberhard et al. 2019; Kropp Dakubu 2015; Some 2013). As mentioned in the introduction, we focus on Dagara Wulé, a northern variety widely spoken in the south-west of Burkina Faso.

Koromfe has been described in Ethnologue (Eberhard et al. 2019) as a developing language with 202,000 speakers (196,000 in Burkina Faso). However, John Rennison (pers. comm.) suggests that this is an overestimation based on ethnic affiliation rather than actual speakers and considers an estimate of around 20,000 speakers more realistic. In the same vein, Rennison (1997: 1–2) already describes Koromfe as “a language that is dying – not only from linguistic pressure […] but from ecological pressure.” The language used to be spoken around the town of Djibo in the north of Burkina Faso, but following large-scale internal displacement of people because of the deteriorating security situation in the wider area (UNOCHA 2021), John Rennison characterises it as “a language without a language area”[3] as of 2022.

A partial representation of the genealogical relationship between these languages is provided in Figure 2, drawing on Hammarström et al. (2021). Bodomo (1993: 111–118) proposed the alternative term Mabia for the Oti-Volta Occidental branch (containing Dagara and Mooré, but not Koromfé). More recently though, Bodomo (2020) extends that term to the whole Gur family, hence our use of the term Mabia/Gur in this article.

Genealogical overview including some further Mabia/Gur languages.

2.2 Salient grammatical properties

This subsection outlines some general grammatical properties of the three languages under discussion. Like most Mabia/Gur languages, Dagara and Mooré are tone languages, both distinguishing high and low tone (Bodomo 1997; Rialland and Some 2000; Some 2003 for Dagara).[4] Some minimal pairs are illustrated in Table 2. Koromfe stands out from other Mabia/Gur languages in lacking tone (Delplanque 2009; Rennison 1997).

Illustration of lexical tone in Dagara and Mooré.

| Language | Low tone | High tone |

|---|---|---|

| Dagara | dà ‘buy’ | dá ‘push several times’ |

| dὺrʋ ‘urine’ | dύrʋ ‘right hand’ | |

| zὺmon ‘intuition’ | zύmon ‘insults’ | |

| Mooré | sḕ ‘to roast’ | sḗ ‘to sew’ |

| mὺk ‘to beat’ | mύk ‘to become deaf’ | |

| kàmse ‘to pick up’ | kámse ‘an arm’ |

Further typical characteristics of Mabia/Gur languages are rigid SVO constituent order, see (2), a binary aspect system with perfective/imperfective verb forms as reflected in the glossing of (2), serial verb constructions and the lack of an overt passive construction (Delplanque 2009; Kropp Dakubu 2015).

| Ayuo | dà | na | nέn. | Dagara |

| Ayuo | buy.pfv | aff | meat | |

| ‘Ayuo has bought meat.’ | ||||

| Mam | yã́ | wáafà. | Mooré |

| I | see.pfv | snake | |

| ‘I saw a snake.’ | |||

| n | zɔmma | a | mũĩ. | Koromfe | |

| you.sg | want.prog | art | rice | ||

| ‘You want some rice.’ | Rennison 1997: 13, (7) | ||||

In the nominal domain, adjectival modifiers, numerals, demonstratives and determiners typically occur post-nominally (Delplanque 2009; Issah 2013; Migeod 1971; Naden 1988; Sulemana 2012), which we interpret as reflexes of largely head-final nominal structures. The Mabia/Gur languages also display a rich noun class system (see Miehe et al. 2007; 2012; Delplanque 2009; Grimm 2010 among others). Miehe et al. (2012) propose a total of 25 noun classes across the family (partly related to the noun classes observed in Benue Congo and particularly Bantu languages), although no individual language makes use of all 25 classes. In contrast to the Bantu prenominal class markers, Mabia/Gur noun class markers are typically postnominal in line with the general head-final tendency in the nominal domain.

The noun class markers interact with number in that nouns marked by a certain noun class marker in the singular are typically marked by a specific different noun class marker to indicate plural. Examples from several Mabia/Gur languages are provided below. Miehe et al. (2012) refer to such pairings of noun classes indicating singular and plural as “genders.” The pairings are, however, neither deterministic, e.g., nouns with the same “singular” noun class may use different noun classes for plural marking within the same language, nor are they homogenous across the family. The specific noun class indications follow the in-depth discussion of the noun class systems in Dagara (Miehe 2012), Mooré (Winkelmann 2012) and Koromfe (Beyer 2012). Elsewhere, we only annotate noun class markers when they are relevant to the immediate point under discussion.

| Dagara |

| pɔ́-ʋ | / | pɔ́-bɔ́ |

| woman-ncl1 | woman-ncl2 | |

| ‘woman/women’ | ||

| bù-ɔ | / | bù-ri |

| goat-ncl12 | goat-ncl21 | |

| ‘goat/goats’ | ||

| Mooré |

| níd-a | / | níd-ba |

| human-ncl1 | human-ncl2 | |

| ‘human/humans’ | ||

| láas-a | / | láas-e |

| plate-ncl12 | plate-ncl12 | |

| ‘plate/plates’ | ||

| Koromfe (Rennison 1997: 338) |

| gab-rɛ | / | gab-a |

| knife-ncl5 | knife-ncl6 | |

| ‘knife/knives’ | ||

| dʋm-dɛ | / | dʋm-a |

| lion-ncl5 | lion-ncl6 | |

| ‘lion/lions’ | ||

| Dogose (Delplanque 2009: 8) |

| gbul-o | / | gbul-be |

| fish-ncl | fish-ncl | |

| ‘fish (sg/pl)’ | ||

| sɔb-ga | / | sɔb-se |

| snake-ncl | snake-ncl | |

| ‘snake/snakes’ | ||

| Curama (Delplanque 2009: 8) |

| to-o | / to-ba |

| father-ncl | father-ncl |

| ‘father/fathers’ | |

| yu-gu | / | yu-nya |

| head-ncl | head-ncl | |

| ‘head/heads’ | ||

| Senar (Delplanque 2009: 8) |

| wɛ-ge | / | wɛ-y |

| leaf-ncl | leaf-ncl | |

| ‘leaf/leaves’ | ||

| gba-ni | / | gba-ke |

| forehead-ncl | forehead-ncl | |

| ‘forehead/foreheads’ | ||

Adjectival modification – at least in Dagara and Mooré – raises some analytical questions as illustrated in (9)–(10), where the modifier seems to intervene between the nominal root bí(í) ‘child’ and the noun class marker (leaving ‘child’ without noun class marker). Double noun class marking is ruled out (9/10b), as is noun class marking of the noun only (9/10c).

| Dagara |

| bí | vl-a |

| child | good-ncl1 |

| ‘a good child’ | |

| * bí-é | vl-a |

| child-ncl1 | good-ncl1 |

| * bí-é | vl |

| child-ncl1 | good |

| Mooré |

| bíí | peel-ga |

| child | white-ncl12 |

| ‘(a) white child’ | |

| * bíí-ga | peel-ga |

| child-ncl12 | white-ncl12 |

| * bíí-ga | peel |

| child-ncl12 | white |

This suggests that the noun class marker (potentially fused with a number projection) is syntactically higher than the noun-adjective complex, but lower than most other elements of nominal structure (numerals, demonstratives, determiners), which generally follow the noun-class-marked constituent. See Hien (2022) for a specific syntactic analysis. Mwinlaaru (2021: 289–291) alternatively suggests that the apparent adjective is actually an ‘adjectival’ noun forming a compound with the preceding entity-denoting nominal root, with the noun class marker occurring on the right edge of the complex noun just like it would with a simplex noun.

A common insight on either approach is that noun class markers are separable from nominal roots under certain circumstances, but nonetheless structurally rather low. Since we are concerned with parts of the nominal domain that are structurally higher than the noun class markers in any case, their nature and exact locus in Mabia/Gur is beyond the scope of this article and we will not explicitly include it in our structures below.

2.3 Data sources

Unless indicated otherwise, the data reported in the following sections are new and were elicited by one author (ANH) from native-speaking consultants. The Dagara data are based on native intuitions of that author and were further verified with six other native speakers. Relevant target sentences for Mòoré were constructed and discussed with the assistance of three native-speaking consultants and further verified with grammaticality judgements from eight other Mooré native speakers. Of the eleven native-speaking consultants of Mooré, two were living in Japan and the remaining nine in Burkina Faso at the time of elicitation. The six native-speaking consultants of Dagara were also based in Burkina Faso. As mentioned at the outset, the Koromfe data are based partly on Rennison (1997), following the notation there, supplemented by data kindly provided by John Rennison.

The orthography used for the Dagara data is based on Joël et al. (2002), the Dagara lexicon published by the national sub-committee for Dagara established by the government of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) in 1975. The Mooré orthography follows Niggli (2016).

We now present the distribution of prenominal a in Dagara (Section 3), Mooré (Section 4) and Koromfe (Section 5).

3 The distribution of a in Dagara

Prenominal a in Dagara marks discourse-related properties similar to definite articles in other languages. While we cannot offer a detailed semantic analysis of Mabia/Gur determiners here, it should be noted that uniqueness (or maximality) is not a sufficient condition for the use of the determiner at least in Dagara, where e.g. the noun ŋmina ‘sun’ does not occur with a determiner on first mention (11) in spite of the intended reference to the unique star around which the earth revolves.[5]

| Ŋmina | tὺl=a | ziãna | tizuo. |

| sun | be.hot.ipfv=aff | today | too.much |

| ‘The sun is very hot.’ | |||

The semantics of the determiner in Dagara – and possibly more widely across other Mabia/Gur languages – may be more adequately described as marking previous mention or familiarity rather than (English-style) definiteness, see also Mwinlaaru (2021) on Dagara Lobr.[6] Examples are provided in (12) and (13). For simplicity, however, we translate determiners in the languages under discussion with plain English definite articles in the remainder of the article.

| A | pʋalé | zɔ-rɔ | na. |

| det | boy | run-ipfv | aff |

| ‘The (aforementioned) boy is running.’ | |||

| Pʋalé | zɔ-rɔ | na. |

| boy | run-ipfv | aff |

| ‘A boy is running.’ | ||

| A | tìsàra | ηmàr | ra. |

| det | plate | break.pfv | aff |

| ‘The (aforementioned) plate broke.’ | |||

| Tìsàra | ηmàr | ra. |

| plate | break.pfv | aff |

| ‘A plate broke.’ | ||

The marker a can be used in noun phrases that contain a (postnominal) demonstrative modifier or a (prenominal) possessor (14). It is not restricted to common nouns in Dagara, but can also occur with proper names (15).

| A | pɔbilé | ηan | yíé-lé | na. |

| det | girl | dem | sing-ipfv | aff |

| ‘This girl is singing.’ | ||||

| A | n | ma | yíé-lé | na. |

| det | my | mother | sing-ipfv | aff |

| ‘My mother is singing.’ | ||||

| A | kὺɔra | náàb=u | ka | u | zù. |

| det | farmer | cow=foc | that | he | steal.pfv |

| ‘It is the farmer’s cow that he stole.’ | |||||

| (A) | Bayuo | yíé-lé | na. |

| det | Bayuo | sing-ipfv | aff |

| ‘Bayou is singing.’ | |||

Whenever present, the determiner is the initial constituent of the noun phrase. It can neither follow the noun (16), nor intervene between a possessor and the head noun (17), not even if there is also an a marker preceding the possessor (17c).

| * | Pʋalé | a | zɔ-rɔ | na. |

| boy | det | run-ipfv | aff |

| * | Tìsàra | a | ηmàr=a. |

| plate | det | break.pfv=aff |

| * | Bayuo | a | yíé-lé | na. |

| Bayuo | det | sing-ipfv | aff |

| * | N | a | ma | yíé-lé | na. |

| my | det | mother | sing-ipfv | aff |

| * | Kὺɔra | a | náàb=u | ka | u | zù. |

| farmer | det | cow=foc | that | he | steal.pfv | |

| intended: ‘It is the cow of a farmer that he stole.’ | ||||||

| * | A | kὺɔra | a | náàb=u | ka | u | zù. |

| det | farmer | det | cow=foc | that | he | steal.pfv | |

| intended: ‘It is the cow of a farmer that he stole.’ | |||||||

In the remainder of this section we discuss the interaction of the Dagara determiner with proper names (Section 3.1), demonstratives (Section 3.2) and with possessive constructions (Section 3.3) in more detail.

3.1 Proper names

While the determiner a can occur with proper names in Dagara, its use is not obligatory and triggers an interpretive effect, thus contrasting with the obligatory and expletive use of definite determiners with proper names in languages like Greek (Lekakou and Szendrői 2012). The tentative characterisation of the determiner as marking familiarity or previous mention appears to be supported in these contexts, too. The exchange in (18) illustrates the use of a with proper names.

| A: | (*A) | Nancy | cén-ne | na | (*a) | Gãnã. |

| det | Nancy | go-ipfv | aff | det | Ghana | |

| ‘Nancy is going to Ghana.’ | ||||||

| B: | Fʋ | wa | bõw | a | u | cénu | bìbír, | fʋ | yel | ku | mã. | M |

| you | when | know | det | her | go | day | you | tell | give | me | I | |

| bɔɔrɔ | na | ka | m | tῦ | ʋ. | |||||||

| want.ipfv | aff | that | I | send | her | |||||||

| ‘When you know her day of departure, tell me. I want to send her (i.e. to do something for me).’ | ||||||||||||

| A: | *(A) | Nancy | cén-ne | na | *(a) | Gãnã | bíό. |

| det | Nancy | go.ipfv | aff | det | Ghana | tomorrow | |

| ‘Nancy is going to Ghana tomorrow.’ | |||||||

At first mention, the use of a is infelicitous with the proper name Nancy and the place (country) name Gãnã ‘Ghana’ (18a). When, possibly after a break in the conversation, A is in possession of the relevant information and informs B of Nancy’s plans, both proper names need to be accompanied by the determiner, presumably because they have been mentioned previously (18c). Mwinlaaru (2021: 297–303) draws similar conclusions concerning the felicity conditions for the determiner occurring with proper names in Dagara Lobr. He also offers an interesting observation on register variation in his data, suggesting that in written discourse the determiner consistently occurs after the first usage, while in spoken discourse subsequent occurrences (after the second mention) may be missing the determiner.

For current purposes we conclude that the Dagara determiner is not sensitive to the distinction between proper and common nouns in interpretation or syntax, occupying the same syntactic position in either context.

3.2 Demonstratives

Noun phrases with a demonstrative modifier are generally introduced by the determiner a (19a), although the determiner may also be absent (19b). We have not been able to identify any specific syntactic or semantic contexts that determine the presence or absence of the determiner.

| A | pɔbilé | ηan | yíé-lé | na. |

| det | girl | dem.prox | sing-ipfv | aff |

| ‘This girl is singing.’ | ||||

| Pɔbilé | ηan | yíé-lé | na. |

| girl | dem.prox | sing-ipfv | aff |

| ‘This girl is singing.’ | |||

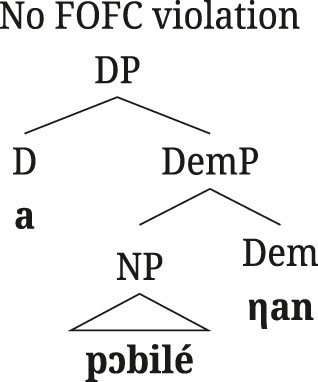

We assume here that the final demonstrative marker realises a head position (Sybesma and Sio 2008) in the extended nominal projection. Since the determiner and the demonstrative are strictly found in pre- or postnominal position respectively, we have no theory-independent evidence concerning which of the two is structurally higher. However, if the determiner and the demonstrative are indeed heads of the same extended projection, the Final-Over-Final Condition (FOFC; Biberauer et al. 2014) can provide relevant insights. It captures a strong crosslinguistic tendency for head-final projections to only take head-final projections as their complements. This means that if a head H takes its complement to its left (so HP is head-final), H can only take a head-final projection WP as its complement as in (20), while a head-initial complement (21) would violate FOFC.

|

|

|

|

If the demonstrative was a final head taking a head-initial DP as its complement as in (22), FOFC would be violated. No such problem arises if the head-final demonstrative projection is a complement of the head-initial DP as in (23).

|

|

We tentatively conclude that demonstratives occupy a structurally lower position than D in Dagara. Section 4.3 will show more straightforward empirical data in favour of such hierarchical relations in Mooré.

3.3 Possessive constructions

Like other Mabia/Gur languages, Dagara places possessors in the position immediately preceding the possessed noun, see (24). Pronominal possessors do not have any morphological genitive marking, but consist of a plain personal pronoun in the same prenominal possessor position as non-pronominal possessors (24b).

| kὺɔra | tumõ |

| farmer | work |

| ‘a farmer’s work’ | |

| m | nab |

| 1sg | cow |

| ‘my cow’ | |

As illustrated in (14bc) above, the determiner a can precede the possessor in possessive nominal phrases. This surface pattern can plausibly arise from two different structural configurations:

| The determiner and the possessor are distinct constituents within the overall possessed noun phrase or |

| the determiner is a subconstituent of the possessor phrase. |

We provide evidence that both configurations are indeed possible. The clearest indication for the first configuration (25a) comes from pronominal possessors. A pronominal possessor may be preceded by the determiner as in (14b), repeated in (26). Since weak personal pronouns in Dagara cannot be accompanied by the determiner when occurring independently (27), the determiner presumably does not form a constituent with the pronominal possessor, but attaches to the overall possessive noun phrase.

| (A) | m | náàb | bè | na | a | pύό | pʋɔ. |

| det | 1sg | cow | be.loc | aff | det | farm | in |

| ‘My cow is on the farm.’ | |||||||

| Náàb | nέb=a | (a) | m | gbέr. |

| cow | step.pfv=aff | det | 1sg | foot |

| ‘A cow stepped on my foot.’ | ||||

| (*A) | m | kàn | na | a | sεbε. |

| det | 1sg | read.pfv | aff | det | book |

| ‘I read the book.’ | |||||

This suggests a structure along the lines of (28). We leave open whether the possessor phrase occupies the specifier position of a dedicated functional head Poss (a) or is simply left-adjoined to the nominal projection (b), but we use the adjunction variant in (28b) throughout this section for exposition. In either case, the possessor phrase is structurally lower than the determiner.

This analysis also captures the earlier observation that the determiner a cannot intervene between a possessor and the possessee noun, illustrated again in (29).

| Kwame | kύ | na | (a) | daba | (*a) | náàb. |

| Kwame | kill.pfv | aff | det | man | det | cow |

| ‘Kwame killed the cow of the man.’ | ||||||

At least for Dagara Wulé, we therefore reject a proposal originally advanced for (Central) Dagaare (Bodomo and van Oostendorp 1994: 13; Bodomo 2004: 7; Bodomo et al. 2018: 10) that possessors are located in SpecDP as in (30b). Such a structure either falsely predicts that a could intervene between the possessor phrase and the possessed noun, contrary to (29) and (17), or requires some ad-hoc mechanism blocking the overt realisation of D in the presence of a possessor. Moreover, this analysis could only account for prenominal a in possessive constructions if the determiner is a subconstituent of the possessor DP. We have just seen that this does not work for pronominal possessors, cf. (26).[7]

| báyúó | gán | bı̀l- | zı̀- | wóg- | bààl- | sòn-né | áyi |

| Bayuo | book | small | red | long | slender | good-pl | two |

| ‘Bayuo’s two small, red, long, slender, good books’ | |||||||

| Bodomo 2004: 6, (10b) | |||||||

|

abbreviated structure after Bodomo 2004: 7, (11b) |

Two observations from the literature suggest that our argument against locating possessors in SpecDP may extend to other varieties of Dagara/Dagaare as well. Example (31) is from Dagara Lobr, which is also spoken in Burkina Faso and belongs to the northern part of the dialect continuum. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it parallels our data in (26). Assuming that the determiner cannot form a constituent with the weak (possessive) pronoun, this again suggests that the possessor position occupied by the pronoun is structurally lower than the determiner.

| a | fʋ | ɩb | wul | kɛ | tɩ | cere. | Dagara Lobr |

| det | 2sg | behaviour | show.pfv | that | 1pl | go.ipfv | |

| ‘Your behaviour means that we (should) go.’ | |||||||

| after Mwinlaaru 2017: 310, (77) | |||||||

The phrase in (32) from the Ghanaian (Central) Dagaare variety gives rise to a structural ambiguity concerning the constituency of pronominal a. Importantly, either structural analysis supports our argument that the determiner is structurally higher than possessors in the language.

| a | n | bie | nga | sukuuli | gan | bil | zi | wog | son-ne |

| det | 1sg | child | dem.prox | school | book | small | red | long | good-pl |

| Dagaare | |||||||||

| ata | ama | zaa | paa | poɔ | |||||

| three | dem.prox.pl | all | intens | among | |||||

| ‘among all these three small red long good school books of this my child’ | |||||||||

| after Bodomo 1997: 48, (9) | |||||||||

On one analysis, sketched in (33a), the initial determiner a belongs to the initial possessor phrase a n bie nga ‘this my child’, yielding the same configuration discussed above for the other Dagara/Dagaare varieties inside the possessor phrase, labelled DP-poss1 in (33a). Since the determiner cannot form a constituent with the weak 1SG pronoun n in the embedded possessor position (DP-poss2), it must realise the head of the structurally higher DP-poss1. The possessive pronoun n can, in turn, not be located in the specifier of DP-poss1, in line with our proposal. On the alternative analysis in (33b), the initial determiner is outside DP-poss1 and directly associated with the matrix DP instead. It is equally straightforward that the possessor phrase n bie nga ‘this my child’ cannot occupy the specifier of the matrix DP, since it should then precede the determiner a, contrary to fact.

| [DP[…P[NP[DP-poss 1 a [ DP- poss 2 n][DemP bie nga]]DP-poss 1 sukuuli gan]NP…]…P]DP |

| [DP a […P[NP[ DP-poss 1 [DP- poss 2 n][DemP bie nga]] DP-poss 1 sukuuli gan]NP…]…P]DP |

While we have not investigated dialectal variation in the Dagara/Dagaare continuum in further detail, these observations support our proposal that Dagara possessors are structurally lower than the determiner even beyond the Wulé variety.

We now turn to the second predicted structural configuration mentioned in (25b) above. Since a possessor can be phrasal, presumably a DP, it should be able to contain a determiner. Considering the open questions regarding the precise semantic contribution of the determiner in Dagara, we restrict ourselves to a distributional argument to support this claim. First, note that the determiner a is not compatible with indefinite expressions marked by the quantifier mine ‘some’ and the postnominal indefinite marker kɔ̃w, as shown in (34b).

| bìbíír | mìnè | kɔ̃w |

| children | some | indf |

| ‘some children’ | ||

| * | a | bìbíír | mìnè | kɔ̃w |

| det | children | some | indf |

Against this background, the initial determiner of the subject phrase in (35) needs to be associated with the possessor pɔw sʋɔbɔ ‘witch’ rather than the possessee bìbíír mìnè kɔ̃w ‘some children’ as sketched in (36a). For concreteness, we analyse mìnè ‘some’ as a quantifier head and kɔ̃w as heading an indefiniteness phrase. The particulars of these assumptions are tangential to our main concern. The important point is that if prenominal a was directly associated with the matrix DP as sketched in (36b), the incompatibility of the determiner a with indefinite kɔ̃w observed in (34b) should result in degraded acceptability in this case as well. The fact that the phrase is well-formed suggests that an alternative analysis along the lines of (36a) is indeed available and that the determiner a can be a constituent of the possessor phrase.

| A | pɔw | sʋɔbɔ | bìbíír | mine | kɔ̃w | máál=a | cúú | zãá. |

| det | woman | witch | children | some | indf | do.pfv=aff | feast | yesterday |

| ‘Some children of the witch celebrated yesterday.’ | ||||||||

A final note is in order concerning a prediction of this proposal. Since we suggest that both the possessor phrase and the possessed phrase are able to host their own independent determiner, they should be able to co-occur as in (37), contrary to fact. Instead, only one instance of the determiner can occur at the beginning of the noun phrase as in (38).

| a. | *a | a | daba | nab |

| det | det | man | cow |

| a | daba | náàb |

| det | man | cow |

| ‘the cow of the man’ | ||

We have already suggested that this phrase is structurally ambiguous between a reading where the determiner associates with the possessor and one where the determiner associates with the overall possessed phrase. It turns out, however, that (39) is also the only way of realising the structure in (37b). We take this to be an instance of haplology (Menn and MacWhinney 1984; see also Kramer 2010: 231–232), a crosslinguistically widely attested phenomenon of reducing adjacent occurrences of identical morphemes. While the structure in (37b) is indeed generated by the syntax, only one of the D heads can be realised, either due to a morphological restriction against two adjacent determiners or a more general phonological process of reducing two adjacent /a/ segments between distinct morphemes.

Independently of whether it is ultimately morphological or phonological in nature, we suggest that a haplology effect accounts for the absence of doubled determiners in (37a) and that there is no syntactic problem with structures like (37b).

3.4 Intermediate summary

We summarise our conclusions concerning the syntactic position of the Dagara determiner relative to demonstratives and possessors in (39) and (40). This extends the suggestion by Bodomo (1997: 50) for the related (Central) Dagaare variety that “except for DP, all projections in the Dagaare nominal phrase are head final” to Dagara. For present purposes, it is insubstantial whether possessors are introduced as specifier of some intermediate functional head (39) or adjoined to NP (40).

We also set aside questions about the relative structural position of possessors and demonstratives, since our focus is on the a morpheme and the data provide no clear cues. We have, however, provided evidence that Dagara possessors occupy a phrasal position lower than the D head of a possessed DP, so crucially not SpecDP (pace Bodomo and van Oostendorp 1994: 13 and subsequent work), since pronominal possessors can be preceded by a determiner as discussed in Section 3.3.

4 The distribution of a in Mooré

Mooré makes use of two different a markers, one prenominal and one postnominal. We address prenominal a in the next subsection before turning to the postnominal determiner in Section 4.2.

4.1 Preproprial article

In Mooré, prenominal a obligatorily precedes proper names like Madou in (41a), but it is excluded with common nouns like bὺmãda ‘baker’ in (41b).[8]

| [*(A) | Madou] | nòng-a | pὺgsáda. |

| ART | Madou | love.ipfv-decl | girl.det |

| ‘Madou loves the girl.’ | |||

| [(*A) | bὺr-manda] | nòng-a | pὺgsáda. |

| art | baker.det love | ipfv-decl | girl.det |

| ‘The baker loves the girl.’ | |||

While place names can be accompanied by the determiner a in Dagara (Section 3.2), in Mooré prenominal a does not occur with place names at all, see (42).

| A | Nancy | rébda | (*a) | Gãnã. |

| art | Nancy | go.ipfv | art | Ghana |

| ‘Nancy is going to Ghana.’ | ||||

Demonstratives can appear with proper names as in (43) for instance to distinguish between multiple people bearing the same name. The demonstratives occur in their usual postnominal position and, judging by consultants’ comments, prenominal a appears to be optional in such contexts. We have so far not been able to identify whether there are additional factors influencing the presence or absence of prenominal a in such cases.[9]

| (A) | Madou | kã̀gà | rebda | waga. |

| art | Madou | dem | go.ipfv | Ouagadougou |

| ‘This Madou is going to Ouagadougou.’ | ||||

Rennison (1997: 146, fn. 31) suggests that prenominal a is a plain prefix in Mooré, which “is not (and perhaps never was) an article like that of Koromfe.”[10] While we agree that the behaviour of the marker in Mooré clearly differs from its cognates in Dagara or Koromfe, it is nonetheless sensitive to its syntactic environment in Mooré.

Mooré prenominal a does not occur “in vocative usage” (Rennison 1997: 80) and is also absent following honorifics like m ma ‘my mother’, m ba ‘my father’ (for referring to people older than one’s parents) and m kε (used to refer to grown up men younger than one’s father), see (44).[11]

| M | kε | Tasre | na | n | waa | beoogo. |

| my | Mr | Tasre | fut | inf? | come | tomorrow |

| ‘Tasseré will come tomorrow.’ | Zongo 2004: 10512 | |||||

- 12

We indicate tone on quoted examples only if the source contains tone marking.

This also applies to titles like nàába ‘chief, king’ (here extended to mean ‘president’). Prenominal a is required with the proper name in (45a), but the title noun in (45b) precludes the use of prenominal a, either directly before the proper name or in front of the title + name complex.

| *(A) | Thomas | Sankara | yɩɩnín-kãsenga | Burkina. |

| art | Thomas | Sankara | was person-important | Burkina |

| ‘Thomas Sankara was an important person in Burkina Faso.’ | ||||

| (*A) | nàáb-a | (*a) | Sankara | yɩɩ | nín-kãsenga | Burkina. |

| art | president-det | art | Sankara | was | person-important | Burkina |

| ‘President Sankara was an important person in Burkina Faso.’ | ||||||

Moreover, prenominal a is also absent when a proper name is accompanied by a possessor as in (46). One consultant commented that they would understand such an utterance with prenominal a preceding the possessor, but would not use it themselves. Speculatively, that consultant’s comment might be related to the usage of non-native speakers of Mooré, since this pattern would be well formed in, e.g., Dagara (cf. Section 3). We consider prenominal a to be incompatible with possessed proper nouns in native Mooré usage in either position marked in (46).

| (*a) | m | (*a) | Madou |

| art | poss.1sg | art | Madou |

| ‘my Madou’ | |||

Overall, prenominal a in Mooré does not behave as a “prefix” in the sense of an integral, “lexical” part of proper names, but rather as a constituent in (systematically) syntactically complex proper names. An anonymous reviewer suggests that Mooré prenominal a be analysed as noun class marker. Beyond the very general notion that it indeed characteristically occurs with a particular class of nouns (human proper names), we do not see any syntactic similarities to the noun class markers described by Miehe et al. (2012). The latter are consistently postnominal in all three languages we address here and, to our knowledge, show none of the above syntactic properties (complementary distribution with vocatives, honorifics and possessors). A further strong argument against an identification of Mooré prenominal a with the noun class markers is the fact that they can co-occur. This is shown in personalised nouns like a Noaaga in (47), which contains the noun noaaga ‘chicken’.

| a | Noaa-ga |

| art | chicken-ncl12 |

| proper name | |

Kusaal, another Mabia/Gur language spoken in northern Ghana, Togo and a small area of southern Burkina Faso, displays a prenominal à marker with a very similar distribution as in Mooré (Musah 2018: 82f. Eddyshaw 2021: 96–97, 99–100). Eddyshaw (2021: 96) characterises the Kusaal marker as personaliser and Musah (2018: 83, fn. 14) describes it as “a ‘reverential’ marker, i.e. revering or giving reference to an otherwise commonplace object, thereby changing its category to a proper or personal name.” The insights underlying both characterisations seem applicable to Mooré as well considering the restriction of prenominal a to person names, recall (42), and the complementary distribution of prenominal a with other types of “reverentiality” markers as in (44).

From a crosslinguistic perspective, Mooré prenominal a resembles proprial/personal articles observed, e.g., in Catalan or in several Oceanic or Scandinavian languages (Ghomeshi and Massam 2009; Johannessen and Garbacz 2014), but also the “personaliser” markers in languages of the Gorokan family in Papua New-Guinea (see Höhn 2017: 57–62 for an overview and further references). How exactly the Mooré type of proprial article fits into the crosslinguistic typology remains a question for future research, but we can already note one peculiarity. In Ghomeshi & Massam’s (2009) data the proprial article occupies the same position as “regular” articles in the respective languages. We will see below, however, that the Mooré DP is right-headed for common nouns, so the determiner follows the noun in contrast to the prenominal position of the proprial article, suggesting that the latter does not occupy the regular determiner position.

Also note that prenominal a is homonymous with the weak third person singular pronoun a in Mooré, illustrated in (48).

| A | wàtame. | |

| 3SG | arrive.IPFV | |

| ‘He arrives.’ | Zongo 2004: 71 | |

This raises the possibility that prenominal a in Mooré forms a type of adnominal pronoun construction (cf. English we linguists; see Choi 2014; Höhn 2017) with proper names. The adnominal occurrence of a third person pronoun may seem unexpected from an Indo-European perspective considering the ungrammaticality of English *they linguists, but is actually crosslinguistically widely attested (Höhn 2020; Louagie and Verstraete 2015). This approach fits the characterisation by Eddyshaw (2021: 96) of prenominal à in related Kusaal as a “personaliser pronoun.”[13] The fact that prenominal a disappears in the vocative is also consistent with this approach if vocatives involve second person reference and are therefore incompatible with a type of third person marker (see Bernstein 2008 for this argument).

We see two potential approaches to a syntactic analysis of prenominal a in Mooré. As will become clear in the next section, prenominal a behaves very differently from regular, postnominal D heads in the language and is therefore unlikely to realise a D head. If Mooré nominal structure is consistently head-final, the prenominal a might actually be a phrase occupying the specifier position of D (49a) endowing the DP with the formal features characteristic for proper names (Ghomeshi and Massam 2009). Assuming that the structure is an adnominal pronoun construction, this would set it apart from adnominal pronouns in languages like English, which are widely assumed to realise the D head (Abney 1987; Höhn 2020; Postal 1969; Roehrs 2005; but cf. Choi 2014 for a similar structure even for English).

|

|

Alternatively, the proprial “article” may represent a distinct syntactic head, e.g. a Pers head marking nominal personhood (Höhn 2016, 2017; Richards 2008). The projection of this head could, in contrast to D, be head-initial as in (50). This analysis does not depend on the presence of a null determiner and is compatible with a lack of DP, depending on the theoretical assumptions for proper names.

|

|

Either analysis is compatible with the presence of a demonstrative projection, see Section 4.3, acounting for the possibility of demonstratives (43). The complementary distribution of prenominal a with possessors and honorifics, which can themselves be internally complex (44), may indicate that they compete for the same syntactic position, possibly favouring a phrasal analysis like (49).

A final verdict has to remain open here, but it seems clear that the proprial article nature of prenominal a in Mooré is distinctly different from the function of its Dagara counterpart as common noun determiner. We now turn to the structure of common noun phrases and the determiner in Mooré.

4.2 Postnominal article

The regular determiner in Mooré is postnominal and occurs in two forms, -a and wa/wã (Peterson 1971; Teo 2016). In contrast to previous work (Nikiema 1989; Peterson 1971; Zongo 2004), which describe both determiner forms as nasalised -ã and wã, Teo (2016) observes the non-nasal form -a. He suggests that the determiner without nasalisation marks identifiability, while nasalisation may represent a distinct morpheme additionally marking contrastive focus.[14] Indeed, our consultants generally did not seem to employ nasalisation in the -a or wa variants of the determiner, which is why we retain the non-nasalised notation when referring to the determiners here. While our focus is not on the interpretation of the determiners, the lack of nasalisation in our data is consistent with Teo’s (2016) hypothesis that nasality expresses contrast, as we did not elicit contrastive contexts.[15] Use of the determiner -a is exemplified in (51a), while its counterpart in (51b) lacks a determiner.

| Mam | yã́ | wíì-s-á | zàamé. |

| I | see.pfv | snake-ncl13-det | yesterday |

| ‘I saw the snakes yesterday.’ | |||

| Mam | yã́ | wíì-s | zàamé. |

| I | see.pfv | snake-ncl13 | yesterday |

| ‘I saw snakes yesterday.’ | |||

Note that the citation form of the noun ‘snakes’ is wíìsi, shown in (52b). Descriptively, the determiner replaces the final vowel in (51/52a), cf. also Zongo (2004: 62). Determiner-less nouns drop the final vowel if they are not utterance-final (51b), but retain it in utterance-final position (52b). The phonological process of final vowel elision (FVE) responsible for the missing final vowel in (51b) is addressed in Section 4.2.1 below.

| Mam | yã́ | wíì-s-á. |

| I | see.pfv | snake-ncl13-det |

| ‘I saw the snakes.’ | ||

| Mam | yã́ | wíì-si. |

| I | see.pfv | snake-ncl13 |

| ‘I saw snakes.’ | ||

The form wa of the Mooré determiner illustrated in (53) is in complementary distribution with -a, cf. (53b), and there is no semantic difference between them.[16]

| Tẽré-∅ | wa | lὺɩ-ame. |

| train-ncl1a | det | fall.down.pfv-decl |

| ‘The train fell down.’ | ||

| * | Tẽr(é)-∅ | wa | lὺɩ-ame. |

| train-ncl1a | det | fall.down.pfv-decl |

The most prominent approach in the literature on Mooré is that the determiner form -a is derived by elision of the glide of the basic form wa. Canu (1976: 150) mentions fast speech and relaxed pronunciation as environments in which the determiner merges with the final vowel of the noun, thereby losing the glide.[17] Other authors provide more specific phonological conditions: Peterson (1971: 77) suggests that the glide is elided if the determiner is located after “an elided vowel (i.e. through application of V elision [see (55) below]) or a nasal consonant.” Nikiema (1989: 96, fn. 4) similarly proposes that the determiner is reduced to -a after a consonant-final nominal base (potentially after application of FVE).

In contrast, Zongo (2004: 61–62) rejects the idea that the distribution of wa und -a is phonologically determined. He suggests instead that -a replaces the final vowel in definite singular forms (Table 3a) and that most plural forms also mark definiteness the same way (Table 3b), with wa being used only in (not further specified) “rare exceptions” (Zongo 2004: 62) for plural nouns like in Table 3c.

Examples based on Zongo (2004: 62) with added indication of their noun class following the classification of Winkelmann (2012: 288).

| Base | Determined | Ncl | Translation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | roo-go | roog-ã | 15 | ‘(the) house’ |

| liuu-la | liuul-ã | 20? | ‘(the) bird’ | |

| koo-m | koom-ã | 22, 23 | ‘(the) water’ | |

| bʋʋ-m | bʋʋm-ã | 22, 23 | ‘(the) reason’ | |

| tong-re | tongr-ã | 5 | ‘(the) extension’ | |

| zoo-do | zood-ã | 21 | ‘(the) friendship’ | |

| b. | roo-do | rood-ã | 21 | ‘(the) houses’ |

| nu-si | nus-ã | 13 | ‘(the) hands’ | |

| pagd-ba | pagdb-ã | 2 | ‘(the) women’ | |

| sɩd-ba | sɩdb-ã | 2 | ‘(the) husbands’ | |

| taam-se | taams-ã | 13 | ‘(the) shea trees’ | |

| c. | kat-a | kata wã | 6 | ‘(the) the hyenas’ |

| liuu-li | liuuli wã | ? [4a?] | ‘(the) birds’ | |

| wagd-a | wagda wã | 6 | ‘(the) thieves’ | |

| mãng-i | mãngi wã | 4 [?] | ‘(the) mangoes’ |

We take the generalisation of Peterson (1971) and Nikiema (1989) that -a and wa are allomorphs occurring after consonants and vowels respectively to be on the right track. Zongo’s association of wa with the plural is at odds with its occurrence in (53) with the singular noun tẽré ‘train’. Moreover, on closer inspection Zongo’s data do not contradict the generalisation if the determiner allomorph is not determined by the noun’s citation form, but only after application of FVE to the nominal base.

The important role of FVE is illustrated by examples like (54), where the final vowel in a word like kata ‘hyenas’ is not only retained in the presence of the determiner (54a), but also in determinerless contexts (54b). This contrasts with the pattern shown in (51) above, where the final vowel of the non-determined noun wíìsi ‘snakes’ is elided in a context similar to (54b).

| A | rígda | kàt-a | wa | zàamé. |

| 3sg | hunt.ipfv | hyena-ncl6 | det | yesterday |

| ‘S/he chased away the hyenas yesterday.’ | ||||

| A | rígda | kàt-a | zàamé. |

| 3sg | hunt.ipfv | hyena-ncl6 | yesterday |

| ‘S/he chased away hyenas yesterday.’ | |||

The non-deleted final vowel in nouns like kàta ‘hyenas’ provides the appropriate context for the use of wa rather than -a in these instances, but the lack of FVE is independent of the determiner. The central observation behind Zongo’s data is then that FVE does not apply to the nouns using the determiner form wa in Table 3c.

4.2.1 Final vowel elision (FVE) in Mooré

This section sketches some properties of FVE in light of its role in allomorph selection for the definite article. Peterson (1971: 58) observes that “[i]n Mooré, any non-nasal suffix vowel which is not in utterance final position is elided”, suggesting the formalisation in (55). The phenomenon is also recognised by other authors (Alexandre 1953: 29; Nikiema 1989: 96; Teo 2016: 46; see also Eddyshaw 2021: 20–24 for a similar phenomenon in related Agolle Kusaal).

| Suffix vowel elision a.k.a FVE following Peterson (1971: 59, (35)) [+SEG] → [−SEG] /-(C)

|

Recall Teo’s (2016) aforementioned observation that the determiners -a and wa can be non-nasal, also borne out in our data. Peterson (1971: 58) proposes that (55) applies “at all levels within words and phrases”, including noun forms marked by the determiner (“definitizer”), and that the final vowel of the determiner is retained due to its nasality. If, however, the vowel of the determiner is not necessarily nasal, applying the rule “at all levels” wrongly predicts that the (non-nasal) determiner -a should be deleted (and the allomorph wa occur as /w/) outside of utterance-final positions. We conclude that whatever the specifics of FVE in Mooré, it does not apply to the determiner, but presumably only lower parts of the nominal domain.

Zongo’s (2004) data in Table 3 as well as our example (54b) suggest that specific noun-class markers escape FVE.[18] The nouns kat-re/kat-a ‘hyena(s)’ and wagd-re/wagd-a ‘thief/thieves’ belong to what Winkelmann (2012: 292–293) identifies as the -RE/-a gender with noun class 5 (-re/-ri/-de/-le) used in the singular and class 6 (-a/-ya) used in the plural. Matters are somewhat more complex for mãng-re/mãng-i ‘mango(oes)’ and liuula/liuuli ‘bird(s)’, but as discussed by Winkelmann (2012: 297–300) the plural class marker -(l)-i of liuuli might either be related to noun class 4 or represent a distinct noun class. Nikiema (1989: 101–102) proposes to distinguish nouns like liuuli ‘birds’ from other nouns classically assigned to noun class 4[19] precisely because the latter undergo FVE. He observes that the definite form of the class 4 noun sib-i ‘reasons’ is sib-ã, suggesting elision of the final vowel and consequently the use of the short form of the determiner. This clearly differs from the form liuul-i wã ‘the birds’ in Table 3c or pugl-i wã ‘the caps’, which he concludes represent a different noun class. Based on this rationale, the plural form mãng-i wa ‘the mangoes’ should belong to the same noun class.[20]

The noun tẽre ‘train’ in (56), repeated from (53), also occurs with wa, suggesting a lack of FVE, but for a simpler reason. It belongs to the ∅/-damba subgender (Winkelmann 2012: 291), with the null marker taken to represent class 1a. Since FVE targets suffixes, the final vowel of the nominal base tẽre ‘train’ remains intact, providing the appropriate phonological environment for the determiner allomorph wa.

| Tẽré-θ | wa | lὺɩ-ame. |

| train-ncl1a | det | fall.down.pfv-decl |

| ‘The train fell down.’ | ||

Further, FVE does not apply to monosyllabic nouns (Alexandre 1953: 29), accounting for the use of the determiner wa with nouns like kí ‘millet’, see (57).[21]

| K-í | wa | sílga | zĩ́i-g | fã́a. |

| millet-ncl4 | det | pour.pfv | place-ncl12 | every |

| ‘The millet poured everywhere.’ | ||||

Monosyllabic nouns ending in a consonant occur with -a as expected since FVE does not apply here, cf. (58). This further supports the claim that the wa/-a alternation is phonologically determined.

| Káa-m | {-a/ | *wa} ka | sṍma | ye. |

| butter-ncl22,23 | –det | det | neg | good neg |

| ‘The butter is not good.’ | ||||

Nikiema (1989: 96) notes that FVE does not take place before “une pause importante”.[22] We tentatively suggest that FVE is suspended not simply at the right edge of an utterance (Peterson 1971: 58), but of an intonation phrase, as suggested by data like (59). The full form wíìsi ‘snakes’ is used because even though the adjunct clause continues the utterance, it presumably starts a new intonation phrase.

| [A | Marie | rígda | wíì-si] IP | [bala | eb | ka | sṍma | ye] IP . |

| Art | Marie | hunt.IPFV | snakes-NCL13 | because | 3pl | neg | good | neg |

| ‘Marie is hunting snakes because they are not good (dangerous).’ | ||||||||

The central observations concerning the distribution of FVE in Mooré nouns are in (60). We do not attempt to further unify or formalise these properties here, since our focus is on the determiners.

| FVE in Mooré |

| applies to the final vowel of noun class markers |

| does not apply in monosyllabic words |

| does not apply to certain noun classes (e.g. classes 1a, 6 and the variety of class 4 containing liuuli ‘birds’ and pugli ‘caps’); potential alternative: does not apply to final vowels with high tone |

| does not apply at the right edge of an intonation phrase (this includes “citation forms”, which represent isolated intonational units) |

4.2.2 FVE and determiners

Importantly, a nominal expression marked by a determiner is not located on the right edge of an intonation phrase in the sense of (60d), licensing FVE if there is no other blocking factor. This is why the determiner -a effectively replaces the final vowel of the noun in examples like (52a) above, repeated in (61) with the deleted vowel in brackets, the noun including class marker enclosed in square brackets and an indication of the relevant intonation phrase boundary. This parallels the occurrence of FVE when other material separates the noun from the right IP-boundary, see (62), a modified representation of (51b).

| Mam | yã́ | [wíì-s(i)] | -á] IP |

| I | see.pfv | snake-ncl13 | –det |

| ‘I saw the snakes.’ | |||

| Mam | yã́ | [wíì-s(i)] | zàamé] IP |

| I | see.pfv | snake-ncl13 | yesterday |

| ‘I saw snakes yesterday.’ | |||

The different structures of (61) and (62) sketched in (63) illustrate that FVE is not triggered by particular syntactic structures, but a phonologically sensitive phenomenon. For simplicity, we assume that non-determined noun phrases lack DP.[23]

|

|

|

|

If the noun class marker ends in /a/ itself, FVE leads to superficial segmental identity between the determined and non-determined version of the object in sentences like (64), even though the underlying structure differs as indicated below.[24]

| A Zakaria gùunda pὺgsáda. |

| A | Zakaria | gùunda | [pὺgsád-(a)] | -a] IP |

| art | Zakaria | wait.ipfv | girl-ncl1 | –det |

| ‘Zakaria is waiting for the girl. | ||||

| A | Zakaria | gùunda | [pὺgsád-a] | ] IP |

| art | Zakaria | wait.ipfv | girl-ncl1 | |

| ‘Zakaria is waiting for a girl. | ||||

As mentioned earlier, the form of the determiner is sensitive to the final segment of the preceding noun after FVE (if applicable). Peterson (1971) and Nikiema (1989) suggest that the form -a results from elision of the initial /w/ of the determiner wa when placed after a consonant. While this is desriptively adequate, /w/ can follow consonants within words like pusginwaagma (denoting a kind of beetle, listed in Niggli 2016 under the entry pusg-n-waag-ma) and across word boundaries as in (65), so elision of /w/ when intervening between a consonant and a vowel does not seem to be a general phonological process in Mooré.

| M | wáta | rṹndã. | |

| 1sg | come.ipfv | today | |

| ‘I am coming today.’ | from entry wa 1 in Niggli 2016 | ||

We therefore consider the -a/wa alternation to be a case of phonologically conditioned allomorphy with -a occurring after consonants and wa elsewhere. For concreteness, we suggest the exponence rules in (66) in the realisational framework of Distributed Morphology (Embick 2010; Halle and Marantz 1993).

| [D] | ↔ | -a | / C__ |

| [D] | ↔ | wa |

4.3 Determiner with proper names and demonstratives

We have seen in Section 4.1 that prenominal a is a type of proprial article in Mooré. However, the actual postnominal -a/wa determiner cannot occur with proper names, in contrast to the prenominal a determiner in Dagara.

Turning to the structure of common nouns, the determiner cannot intervene between the noun and a demonstrative, see (67),[25] but it can follow the demonstrative as in (68). In (68b) the plural demonstrative kẽsé ‘these’ has undergone FVE (see Section 4.2.1) and the determiner is subsequently realised without the initial glide.[26]

| Pὺgsád(*-a) | kã̀gà | yíídame. |

| girl-det | dem | sing.ipfv |

| ‘This girl is singing.’ | ||

| Bi-kãngã | wã | yẽ | yii | yɛ? |

| child-dem | det | he.emph | come:from.ipfv | where |

| ‘This child here, where does he come from?’ | ||||

| from entry kãngã in Niggli 2016 | ||||

| fu | kẽs-ã | |

| dress | dem-det | |

| ‘those dresses’ | after Alexandre 1953: 79 | |

The possible co-occurrence of demonstratives and determiners suggests that they occupy distinct syntactic positions, with determiners structurally higher than demonstratives as sketched in (69). This matches the hierarchical relation between demonstratives and determiners discussed for Dagara in Section 3.2, albeit with opposite directionality of the determiner.

|

|

4.4 Possessive constructions

As in other Mabia/Gur languages, the Mooré possessor precedes the possessee. Both can be freely marked – or not marked – by the determiner, see (70).

| A | Kwame | kὺ | [[pág] | nagagnãg] | zàamé. |

| art | Kwame | kill.pfv | woman | cow | yesterday |

| ‘Kwame killed a cow of a woman yesterday.’ | |||||

| A | Kwame | kὺ | [[pág] | nagagnãg-a] | zàamé. |

| art | Kwame | kill.pfv | woman | cow-det | yesterday |

| ‘Kwame killed a woman’s cow yesterday.’ | |||||

| A | Kwame | kὺ | [[pág-a] | nagagnãg] | zàamé. |

| art | Kwame | kill.pfv | woman-det | cow | yesterday |

| ‘Kwame killed a cow of the woman yesterday.’ | |||||

| A | Kwame | kὺ | [[pág-a] | nagagnãg-a] | zàamé. |

| art | Kwame | kill.pfv | woman-det | cow-det | yesterday |

| ‘Kwame killed the woman’s cow yesterday.’ | |||||

This is expected if the possessor consists of a full head-final nominal expression embedded within another head-final nominal projection. Simultaneously, it contrasts with the Dagara possessive constructions discussed in Section 3.3, where adjacent determiner clusters resulting from head-initial DP structures were argued to be reduced by a haplology effect, allowing only one overt determiner and giving rise to structural ambiguities. The head-finality of Mooré determiners circumvents the issue of adjacent determiners and hence the need for haplology in (70).

At the same time, the initial determiner in Dagara provides a clear diagnostic suggesting that the possessor phrase is structurally lower than the determiner in that language. For Mooré, the lack of prenominal material apart from possessors themselves makes it difficult to assess their attachment height. The availability of a prenominal possessor position independently of the presence or absence of a determiner on the possessee is compatible with a structure where the possessor is introduced lower than D like we proposed for Dagara, either directly adjoined to NP (71a) or possibly in the specifier of some lower functional projection, e.g., a dedicated Poss(essor)P (71b).

In principle, even an analysis where the possessor is located in the specifier of the matrix DP would be feasible for Mooré, in contrast to Dagara. That approach would crucially depend on the assumption of a silent D head in examples like (70a) where there is no overt determiner in the possessed matrix phrase. While we do not exclude the latter possibility, we deem an analysis with a lower possessor position along the lines of the two options in (71) to be a more promising working hypothesis from a comparative perspective, since we have already discussed evidence in Section 3.3 that Dagara possessors are lower than DP and we will see indications for the same conclusion for Koromfe in Section 5.

4.5 Intermediate summary

In Mooré, prenominal a only marks proper person names and acts as a type of proprial article. However, while proprial articles in other languages typically occupy a comparable position to determiners used with common nouns, the proprial article and the regular determiner are located on opposite sides of the noun in Mooré. We conclude that they occupy distinct syntactic positions and tentatively suggest that prenominal a is a special type of adnominal pronoun (cf. English we linguists) marking personhood (see also Section 6.2). Structurally, it might be phrasal in nature (72a) or represent a distinct head in the nominal projection (72b).

Mooré projects a head-final DP for common nouns. The determiner has two allomorphs -a and wa whose distribution is conditioned by whether the preceding word ends in a vowel or consonant (after application of final vowel elision (FVE)). We propose that determiners are hierarchically higher than demonstratives as in (73), but remain uncommitted concerning the attachment site of prenominal possessors.

In Mooré possessive constructions, possessor and possessee may each independently display a determiner. This contrasts with the restriction to one determiner in Dagara possessive constructions, which we proposed in Section 3 to be a result of that language’s head-initial DP structure and a haplology effect preventing the occurrence of two adjacent determiners by deleting one of them. Due to the proposed head-finality of the Mooré DP, configurations involving two adjacent determiners do not normally arise and there is no need for haplology.[27]

5 The distribution of a in Koromfe

In Koromfe, the prenominal a marker “occurs obligatorily before all common nouns” (Rennison 1997: 80) except in specific syntactic contexts which we turn to in Section 5.1. We follow Rennison’s (1997) usage in glossing a as an article, but stress that this is merely a descriptive convention. The marker does not appear to have discourse-related semantics (or indeed any other discernible semantic contribution). Notably, noun phrases require prenominal a independently of the presence or absence of postnominal determiners, cf. (74) versus (75). The marker is used with both count (74a) and mass nouns (75b).

| a | bɔrɔ | hoŋ |

| art | man.sg | det.hum.sg |

| ‘the man’ | ||

| a | bɔrɔ | hoŋo | |

| art | man.sg | long.det.hum.sg | |

| ‘this/that man’ | Rennison 1997: 81 | ||

As illustrated in (74), determiners occur on the right edge of the noun phrase (Rennison 1997: 234). They inflect for number, humanness and diminutive and come in short and long forms as shown in Table 4. Rennison compares the short form to the English definite article and the long form to demonstratives, albeit “with less deictic force than the deictics” (Rennison 1997: 81).

Koromfe determiners after Rennison (1997: 234, (559)).

| +HUMAN | –HUMAN | DIM SG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | PL | SG | PL | SG | |

| Short | hoŋ | bεŋ | koŋ | hε̃ŋ | kεŋ |

| Long | hoŋgo | bεŋgε | koŋgo | hε̃ŋgε | (Not used) |

Two deictic markers are in complementary distribution with the determiners, occupying the same noun-phrase-final position. Nandɪ is discourse anaphoric, agrees with the head noun for number and humanness (Table 5) and also requires the presence of prenominal a (Rennison 1997: 83), cf. (76). The other deictic, naŋsa, blocks the occurrence of prenominal a and is addressed in Section 5.1.

Forms of nandɪ after Rennison (1997: 235, (560)).

| SG | PL | |

|---|---|---|

| +HUMAN | nandɪ | namba |

| –HUMAN | naŋgʊ | nahε̃ |

| a | bɔrɔ | nandɪ | |

| art | man.sg | deict.hum.sg | |

| ‘that man (that we’ve just been talking about)’ | Rennison 1997: 81–82 | ||

Generic noun phrases cannot contain a postnominal determiner (Rennison 1997: 236), but still require prenominal a, see (77).

| a | hem | jagalɪ | la | a | kamɔ̃ | |

| art | water | fresh | cop | art | old.person | |

| ‘Fresh water is the most important thing.’ | Rennison 1997: 237, (563) | |||||

Both prenominal a and a short determiner are used in vocatives, see (78).

| a | kɛ̃ɔ̃ | hoŋ! | |

| art | woman | det.hum.sg | |

| ‘Woman!’ (polite form of address) | Rennison 1997: 82 | ||

Finally, prenominal a also occurs in expressions with the quantifiers dʊrʊ ‘all, every’ (79) and maŋəna ‘some’ (80).

| a | kɛ̃ɔ̃ | dʊrʊ |

| art | woman.sg all | ‘every woman’ |

| a | kɛ̃na | dʊrʊ | |

| art | women.pl | all | |

| ‘all women’ | Rennison 1997: 83 | ||

| də | niilʌʌ | a | fʊba | maŋəna | |

| 3sg.hum | see.prog | art | person.pl | some | |

| ‘He sees some people.’ | Rennison 1997: 165, (429) | ||||

5.1 Contexts disallowing the a marker

In contrast to Mooré and Dagara, proper names generally do not occur with prenominal a in Koromfe (Rennison 1997: 80). Rennison (1997: 235) mentions language names as an exception, although for the example a frãsɛfɛ ‘French’ one might speculate about interference from the obligatory definite article in French.

While the previous section showed that prenominal a shows up in most common noun phrases, certain nominal modifiers block its occurrence (Rennison 1997: 80). Beginning with postnominal modifiers, cardinal numerals, the deictic naŋsa ‘that X over there’ and the quantifier kãã/kãmã ‘every’ suppress pronominal a. For cardinals, this is shown in the second and third occurrence of the noun zenʌ ‘years’ in (81). Ordinals, on the other hand, do not interfere with the article (82).

| gʊ | tɪ | a | zenʌ | zenʌ | tãã | gʊ | jakʊ | |

| 3sg.nhum | put/do | [art | year.pl] | [year.pl | three] | 3sg.nhum | walk.dur | |

| zenʌ | nãã. | |||||||

| [year.pl | four] | |||||||

| ‘It takes years, three years—four years pass.’ | Rennison 1997: 305, (695) | |||||||

| a | dɔɔ | pote | koŋ | la | bĩnĩŋ | |

| art | animal.sg | first.sg | det.nhum.sg | cop | black.sg | |

| ‘The first animal is black.’ | Rennison 1997: 306, (705) | |||||

The “strongly deictic” marker naŋsa ‘that X over there’ also blocks prenominal a (Rennison 1997: 83), see (83). It contrasts with the determiners and the other demonstrative nandɪ not only in this respect, but also by not showing agreement for features like animacy or number. Importantly, naŋsa does not only suppress prenominal a, but also any other nominal modifiers (Rennison 1997: 86).

| bɔrɔ | naŋsa | |

| man | deict | |

| ‘that man over there’ | Rennison 1997: 83 | |

Noun phrases containing the quantifier kãã/kãmã ‘every’ also generally lack prenominal a, although the marker appears to be acceptable (at least for some speakers) when the noun phrase is utterance initial (John Rennison, pers. comm.).[28] We have no account for this, but follow the more general tendency and treat kãã/kãmã as suppressing prenominal a.

| (a) | wete | kãmã | |

| art | day.sg | every | |

| ‘every day’ | John Rennison (pers. comm.) | ||

The only other class of prenominal elements in Koromfe that also block prenominal a, is possessors. In (85a), only the possessor phrase contains the a marker and there is no additional marker associated with the head noun dãŋ ‘nest.’ In spite of the superficial similarity, Rennison notes the structural difference from plain N+N compounds, which are characterised by the lack of a class marker on the first noun and where the a marker is associated with the whole compound as in (85b).

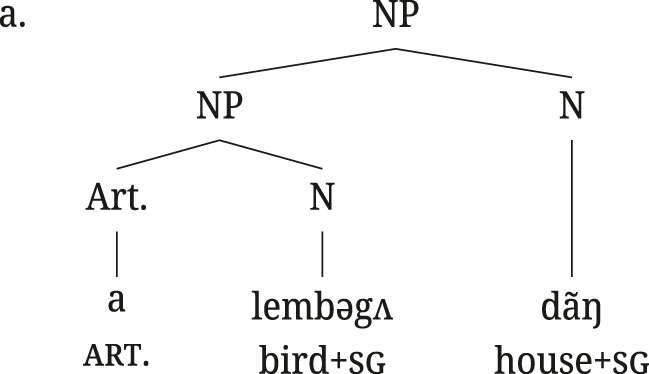

|

= ‘a bird’s nest’ |

| Rennison 1997: 349, (760) |

|

= ‘nest’ (for one or more birds) |

| Rennison 1997: 344, (751) |

Let us briefly address a possible objection. Recall that we claimed in Section 3.3 that the restriction to one prenominal a in Dagara possessive constructions is a haplology effect. In parallel, one might suggest that in Koromfe the possessor phrase and the matrix noun phrase also both contain a phrase-initial a, with the possessor structurally lower than the prenominal a of the possessee phrase. Both markers would end up adjacent to each other and haplology could reduce them to one instance again. Such an analysis can be ruled out for Koromfe for two reasons. First, pronominal possessors also exclude the occurrence of prenominal a, see (86).

| mə | sundu | |

| 1sg | horse.sg | |

| ‘my horse’ | Rennison 1997: 18, 37 | |

Similar to Dagara and Mooré, Koromfe pronouns cannot be marked by a. If prenominal a in examples like (85a) could be connected to the possessee rather than the pronominal possessor as discussed for Dagara around (28) above, it should also be able to show up in (86). Since it cannot, possessors preclude prenominal a in the nominal projection they modify.

A similar argument can be derived from other contexts where the possessor phrase contains an element blocking initial a, like the numeral in (87). If prenominal a was able to associate with the possessee, it should still be able to occur in such contexts, contrary to the reported facts.

| [[jɩbrɛ | dom] possessor | sa] | |

| eye.sg | one | owner.sg | |

| ‘a person with one eye’ (lit. ‘a one-eye owner’) | |||

| after Rennison 1997: 352, (767) | |||

We conclude with Rennison (1997) that prenominal a is in complementary distribution with possessors. Table 6 provides an overview of the contexts where prenominal a is used in Koromfe.

Distribution of prenominal a in Koromfe. Prenominal a occurs in all noun phrases that involve one of the feature combinations marked by ✓.

| Postnominal elements | Prenominal possessor | |

| no | Yes | |

|

|

||

| None | ✓ | ✗ |

| Quantifier dʊrʊ ‘all’ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Quantifier maŋəna ‘some’ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Determiners | ✓ | ✗ |

| Deictic nandɪ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Deictic naŋsa | ✗ | ✗ |

| Numerals | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quantifier kãã/kãmã ‘every’ | (✗) | ✗ |

5.2 Koromfe a as an expletive

In this section we argue that the complementary distribution of possessors and prenominal a is due to a (mostly) obligatory syntactic position in Koromfe that can be occupied either by possessors or prenominal a.[29] The latter functions as an expletive with the purely syntactic function of filling this position in the absence of a possessor phrase. This roughly parallels the way expletive pronouns like English it in It seems that… fill the obligatory subject position when there is no thematic subject (cf. the Extended Projection Principle/EPP of Chomsky 1981: 26–28, 40–41; Chomsky 1982: 10). The observation that prenominal a does not contribute to the meaning of nominal expressions is expected on this approach, since a lack of semantic content is characteristic for expletives.

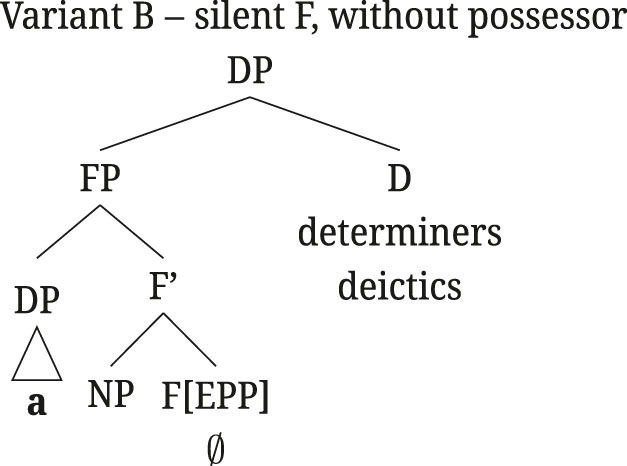

If this is on the right track, the relevant position is unlikely to be a – typically optional – adjunct and should instead be structurally selected. In analogy to the classical analysis of the English subject position as specifier of the T head we therefore assume that possessors and prenominal a occupy a specifier position in the extended nominal projection of Koromfe. Considering the consistently postnominal position of determiners and demonstratives, we take DP in Koromfe to be head-final, like in Mooré. However, the lack of prenominal material aside from a and possessors makes it similarly difficult as in Mooré to clearly identify the attachment site of possessors. The relevant position may either be the specifier of DP or of some other functional head F as in (88). We eventually argue that the latter represents the most promising analysis, but begin by sketching the first option.

|

|

We have seen above that the quantifiers dʊrʊ ‘all, every’ and maŋəna ‘some’ are compatible with prenominal a (79–80), while the quantifer kãã/kãmã ‘every’ typically blocks it (84). Another difference between kãã/kãmã and the other quantifiers is the former’s complementary distribution with determiners, see (89) versus (90).

| la | (a) | vεŋa | koŋ | dʊrʊ | |

| with | art | rain.sg | det.nhum.sg | all | |

| ‘with all the rain’30 | after Rennison 1997: 167, (439) | ||||

- 30

Prenominal a is phonologically elided after vowels in normal speech, see Rennison (1997: 298).

| a | kε̃na | hε̃ŋ | maŋəna |

| art | woman.pl | det.hum.pl | some |

| ‘some (of the) women’ | |||

| kε̃ɔ̃ | (*hoŋ) | kãã |

| woman.sg | det.hum.sg | every |

| ‘every woman’ | ||

This indicates a structural difference between the two types of quantifiers. Sticking to the idea that Koromfe nominal structure is generally head-final, dʊrʊ and maŋəna seem to occupy a position higher than D. Kãã/kãmã, on the other hand, either realises the D head itself or occupies a lower head position.

The claim that kãã/kãmã is structurally lower than the other quantifiers is supported by (91). While a combination of the two universal quantifiers is uncommon, John Rennison (pers. comm.) reports a clear preference for the construction with kãã/kãmã closer to the noun (91a), while the opposite order is completely out.[31]

| a | wete | kãmã | dʊrʊ |

| art | day | every | all |

| ‘every day’ | |||

| * a | wete | dʊrʊ | kãmã |

| art | day | all | every |

Let us first consider the possibility that kãã/kãmã is located in D as illustrated schematically in (92). The quantifiers dʊrʊ ‘all’ and maŋəna ‘some’ have no influence on whether or not the possessor/prenominal a position is available, since they are higher up in the tree. Most D heads have a syntactic property requiring the projection of a specifier position (e.g., an EPP feature in minimalist parlance), which has to be filled by a possessor or, if there is none, by expletive a. Some variants of D, however, lack this feature, so a specifier is not mandatory and expletive a is never needed as a last resort. If this applies to kãã/kãmã and the strongly deictic marker naŋsa, we have a unified account for why both are used without prenominal a.

|

However, this approach has nothing to say about the complementary distribution of prenominal a with numerals.[32] As shown in (93), numerals precede determiners and should therefore occupy a position distinct from and lower than D, so it is unclear how they would block prenominal a from occurring in Spec,DP.

| dɔɔfɪ | j̃ɔ̃ɔ̃nε | bĩnĩʌ̃ | tãã | hɛ̃ŋgɛ | |

| animal.pl | small.pl | black.pl | three | long.det.nhum.pl | |

| ‘those three small black animals’ | Rennison 1997: 85, (233) | ||||

Importantly, numerals are also in complementary distribution with the quantifier kãã/kãmã, see (94). This represents yet another difference between kãã/kãmã and the other two quantifiers, which combine with numerals just fine, see (95).

| * bɔ̃nε | hʊrʊ | kãã |

| goat.pl | six | every |

| bɔ̃nε | tãã | dʊrʊ |

| goat.pl | three | all |

| ‘all three goats’ | ||

| bɔ̃nε | hʊrʊ | maŋəna |

| goat.pl | six | some |

| ‘some of (the) six goats’ | ||

Against this background, we propose that kãã/kãmã and numerals realise the head of a functional projection FP located lower than DP, possibly a type of cardinality phrase (Lyons 1999) or a low quantifier phrase. Prenominal a and possessors are then located not in Spec, DP, but in a lower Spec, FP position as in (96).

|

Crucially, there is also a null/silent F head. Only this head requires Spec,FP to be realised by prenominal a iff there is no possessor occupying that position. As proposed at the outset of this section, in this way prenominal a behaves just like expletive pronouns (it, there) occupying the obligatory subject position in languages like English when there is no thematic subject to fill the position.

The introduction of possessors in the specifier of a projection headed by numerals may seem curious. While largely based on European languages, a line of thought by Radford (2000) further adapted by Alexiadou et al. (2007: 560–563) may provide an insightful perspective on the Koromfe data as well. They suggest that possessors are first introduced in a low structural position (e.g., the specifier of a PossP or a light nP) before moving into a higher position.

This, of course, parallels the movement of subjects into Spec,TP related to the Extended Projection Principle. It also fits in neatly with our proposal that prenominal a is an expletive element. A syntactic account along these lines is to assume that the silent variant of F is endowed with an EPP feature requiring a filled specifier position. This requirement can be satisfied by raising a possessor to SpecFP (97) or, if there is no possessor, by directly merging expletive a in SpecFP as in (98).

|

|

An alternative conceptualisation of the EPP-effect without the postulation of a syntactic EPP feature may be to assume a requirement for phrases to be visible as tentatively formulated in (99). This represents a weaker version of the Edge(X) requirement by Collins (2007), which allows only either the head or specifier of a phrase to be overt, but not both.[33]