Abstract

While various aspects of language teachers’ emotional experiences have been gaining attention, including emotion labor and emotional capital, less attention has been placed on the emotional experiences of teacher educators supporting language teachers in emotionally challenging situations. Following calls to examine language teachers’ emotional experiences ecologically and as socially and institutionally shaped, we engaged in collaborative autoethnography to explore how language teacher and teacher educator emotion labor reflects answerability to multiple commitments in the face of external feeling rules. Our findings highlight how language teacher–teacher educator collaboration can mitigate as well as reproduce emotion labor. This study contributes to research on language teacher emotion labor by focusing on the role of the teacher educator in supporting language teacher emotional capital and highlighting the complexity underlying emotion labor and emotional capital as multi-directional. Furthermore, the study illustrates how collaborative autoethnography can generate reflexivity and emotional capital for language teacher educators.

1 Introduction

The affective turn in second language acquisition (Pavlenko 2013) and language teacher education (De Costa et al. 2019) has led to increased investigations of the role of emotions in language teaching and learning. In addition to studies investigating various aspects of language teachers’ emotional experiences, such as emotion labor (Benesch 2017) and emotional capital (Gkonou and Miller 2021), autoethnographic studies by language teachers themselves have generated greater emotional reflexivity among teachers that can ultimately inform their pedagogical practices. However, fewer studies have explored the emotional experiences of teacher educators as they support and advocate for language teachers in emotionally challenging situations. Following calls to examine language teacher emotions ecologically (Mercer 2021) and as socially and institutionally shaped (Benesch and Prior 2023), we engaged in collaborative autoethnography to examine how our own experiences of collaboration between language teachers and teacher educators can mitigate emotion labor as well as reproduce it.

Autoethnography (Mirhosseini 2018) has been increasingly adopted as an approach to developing teacher (educator) reflective practice and emotional reflexivity in applied linguistics and language education (Liu et al. 2021; Song 2022; Yazan 2023). In particular, collaborative forms of autoethnography (De Costa et al. 2022; Montgomery and Kudritskaya 2024; Pentón Herrera et al. 2022) and self-study (Deroo et al. 2022) can be helpful tools for studying emotions and emotion labor as teachers reflect on and recontextualize prior experiences and their associated emotions through others’ perspectives. Drawing on these approaches, we engaged in collaborative autoethnography involving multiple phases of narrative reflection about our experiences as teacher educators.

The three of us are language teacher educators, currently working on doctoral degrees in Second Language Studies, each with substantial experience teaching languages. In this paper, we explore our experiences of emotions resulting from tension between multiple commitments in the face of external feeling rules (i.e., institutional expectations about how emotions should be controlled, hidden, displayed, and/or performed, Hochschild 1983). Our attention to the complex, overlapping roles characteristic of language teacher-teacher educator relationships contributes to research on language teacher emotion labor and extends this body of scholarship in three ways. First, it focuses on the role of the teacher educator in supporting language teacher emotional capital. Second, it highlights the complexity underlying emotion labor and emotional capital by showing how efforts to generate emotional capital can mitigate as well as reproduce emotion labor. Finally, this study illustrates how collaborative autoethnography can generate reflexivity and emotional capital for language teacher educators.

2 Literature review

2.1 Language teacher emotion labor, answerability, and multiple commitments

Benesch (2017) describes emotion labor as the work language teachers perform to manage their individual feelings in relation to external or institutional policies and expectations toward how they experience and display emotion. Noting that the term emotion labor has been adopted recently in a broad sense to describe teachers’ abilities to regulate any emotions or withstand any difficult experience, Benesch and Prior (2023) have called for a return to the term’s critical and poststructuralist origins (see Hochschild 1983) that recognize emotions as socially constructed vis-à-vis institutional feeling rules and that critically interrogate institutional working conditions that often do not validate teachers’ emotional experiences. We take up Benesch and Prior’s call in examining emotion labor not just as a result of any tension between individual practices and institutional expectations, but rather as a result of how institutional feeling rules in particular mitigate teachers’ emotions resulting from such experiences of tension.

To explore these experiences of tension, we adopt Bernstein’s (2019) use of the Bakhtinian notion of answerability to interpret the negotiation of multiple commitments. Answerability, considered a precursor to Bakhtin’s (1990) concept of dialogism, frames all communication and behavior as answering to others (reflecting a commitment or obligation to others) as well as to oneself (reflecting a commitment or obligation to one’s own values). Bernstein (2019) employed the notion of answerability to critically reflect on her positionality as a researcher interacting with multiple stakeholders, noting that “when a researcher aims to act answerably in a study involving multiple participants in multiple interacting roles, tensions can arise. The question ‘to whom am I answerable right now?’ may not always have a definite response” (p. 131). This view of answerability highlights how tensions can arise from aiming to be answerable to multiple commitments as we collaborate with teachers and other parties in our respective practices as teacher educators. In particular, we examine the emotion-laden nature of these moments of tension as well as the emotional effects they have on us.

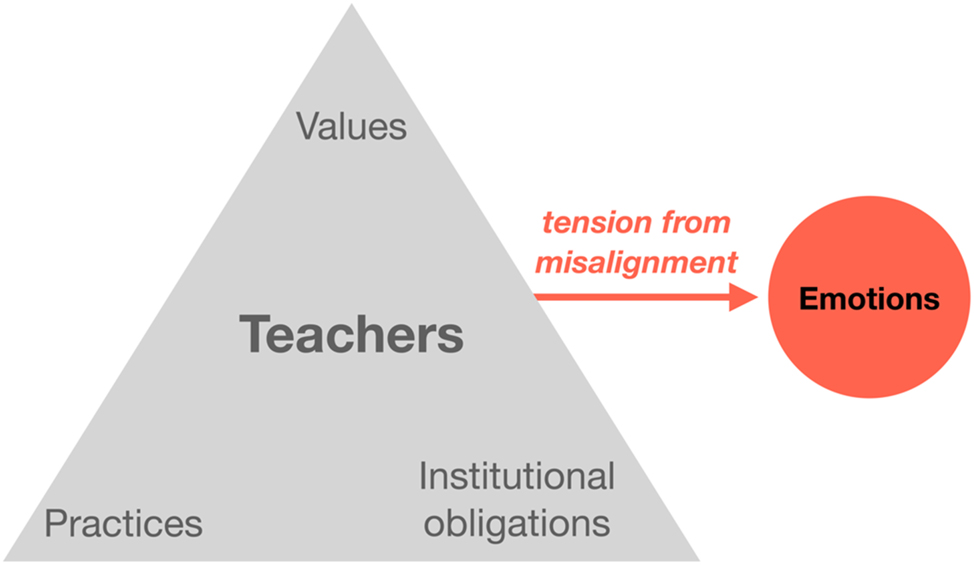

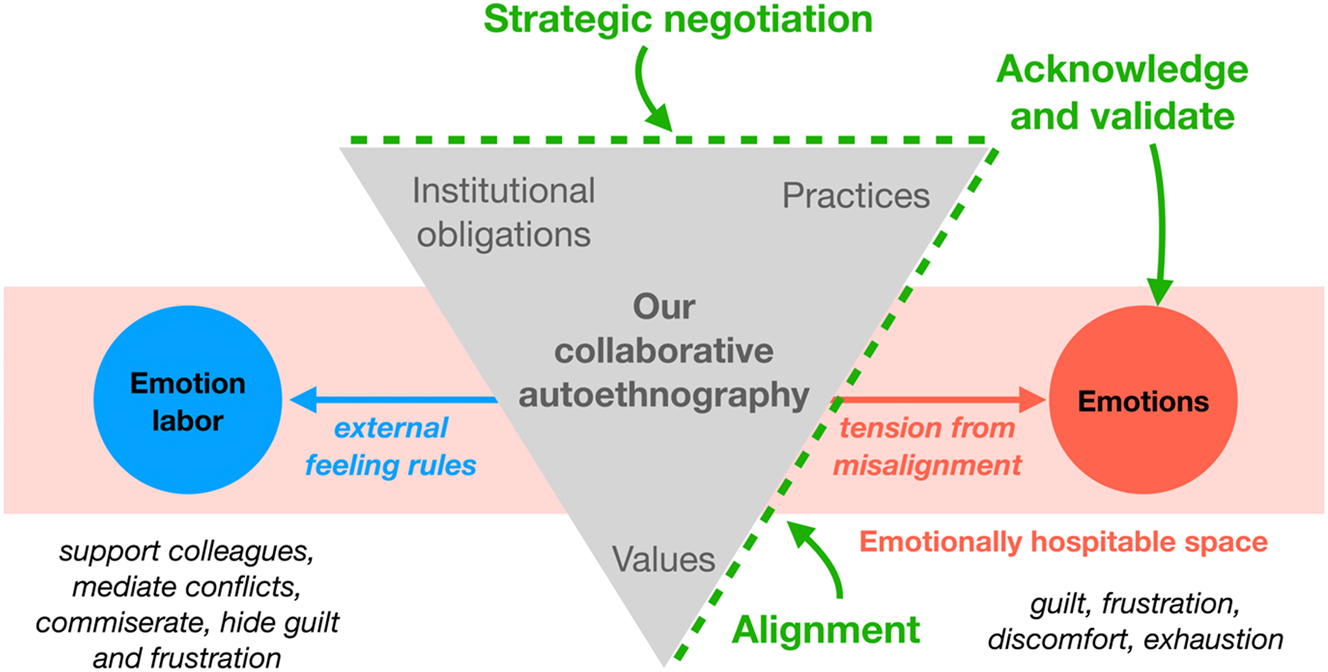

Since teachers (and teacher educators) work within institutions, they will always encounter some degree of tension and conflict between institutional policies, colleagues’ expectations, and their own (pedagogical) practices and values. (Mis)alignment between any of these elements is significant in that it can result in validation or contestation of teacher identity (De Costa and Norton 2017), teacher agency (Pappa et al. 2019), and teacher wellbeing (Mercer 2021). For example, Montgomery et al. (2024) examined how identity tensions and feelings of guilt and frustration resulted from misalignments between teachers’ practices and institutional expectations across micro, meso, and macro levels of their individual teaching contexts. Focusing on agency and wellbeing, Cinaglia et al. (2023) investigated whether ecological affordances and constraints enabled teachers to enact a pedagogy in line with their values. The authors considered how wellbeing, in the form of meaningful engagement (or lack thereof) with students, peers, and overall institutional context, was reflected by teachers’ feelings of support and inclusion or guilt, discomfort, and exclusion. Both studies illustrate how answerability to multiple commitments can result in emotion-laden tensions that jeopardize teacher identity, agency, and wellbeing. This emotion-laden tension resulting from misalignment between a teacher’s own practices, values, and institutional expectations is illustrated in Figure 1.

Emotional responses to tension from misalignment.

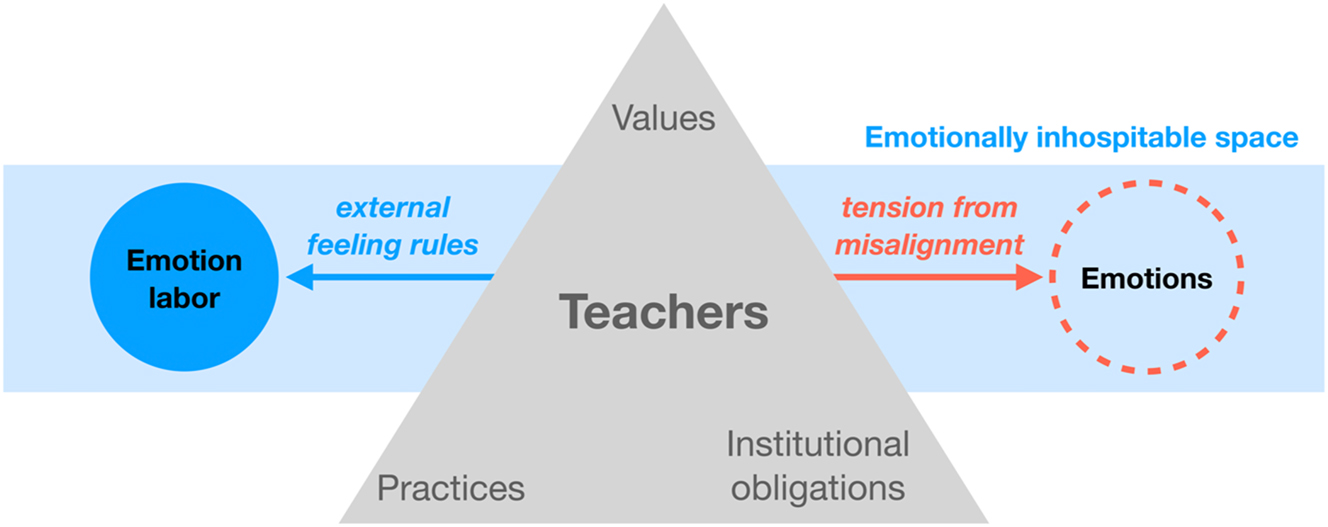

While tension in and of itself is certainly worth examining, the significance of investigating tension resulting from emotion labor is that it reveals the multiple layers of answerability and commitment teachers negotiate on an ongoing basis. Whereas general tension from misalignment can shape teachers’ pedagogical decisions and result in specific emotions, tension from feeling rules in particular shapes how teachers experience and manage these emotions. This additional layer of complexity is illustrated in Figure 2. The dotted line around the “Emotions” circle indicates the effect of emotion labor in creating an “emotionally inhospitable space” (Benesch and Prior 2023: 7), represented by the blue background, that may not allow for emotions to be authentically experienced. Gkonou and Miller (2019) documented how emotion labor can arise when teachers attempt to follow implicit feeling rules to display care. In their study, emotion labor occurred as teachers suppressed their actual emotions in response to pressure and anxiety about curricular expectations. Focusing on explicit feeling rules as articulated through institutional policies, Pereira (2018) investigated how mandated caring teaching practices inadvertently harmed teacher wellbeing. When teachers’ values of caring to promote student wellbeing clashed with institutional rationale to enact caring practices to improve test scores, this misalignment led to emotion labor as teachers felt pressure to continue performing care in the face of guilt, overwork, and burnout. In each of these studies, answerability to feeling rules and the resulting emotion labor that ensues compounds and complicates the existing tension teachers experience. After all, teachers are regularly expected to be answerable to multiple parties, including students, colleagues, institutional policies, and societal demands, among others.

Emotion labor from feeling rules mitigating emotional responses to tension.

2.2 Language teacher emotion labor and emotional capital

The teachers in Gkonou and Miller’s (2019) and Pereira’s (2018) studies experienced emotion labor due to what Benesch and Prior (2023) describe as “emotionally inhospitable” institutional contexts (p. 7), that is, working conditions that did not validate their emotional experiences. While Benesch (2017) draws attention to the importance of problematizing and interrogating institutional feeling rules that result in emotion labor, she also notes that emotion labor itself can be useful in pushing teachers to resist and negotiate external expectations in their favor. In line with this suggestion, Song (2021) examined the emotional experiences of a student teacher in a new teaching context. The author observed that the teacher’s perceived expectation to perform enthusiasm despite her disappointment about the dominant attitudes toward students in her school led to emotion labor. However, the author also noted that the teacher’s efforts to manage her emotions in relation to external expectations led to her own reflexivity, resilience, and resistance to dominant discourses. Gkonou and Miller (2021) similarly observed that collaborative reflection among language teachers generated emotional capital, that is, the ability to meet and often resist institutional expectations for how they perform emotions. Specifically, the authors found that reflection benefitted teachers by allowing them to compare their experiences and develop knowledge of institutional expectations as well as resources enabling them to work within these expectations. In both studies, the practice of reflection about experiences of emotion labor led to teachers developing a greater capacity to meet and at times disrupt institutional expectations.

2.3 Autoethnographic approaches to studying language teacher emotion

While studies focusing on language teachers have revealed multiple aspects of their emotion-laden experiences, autoethnographic investigations by language teachers themselves have highlighted how studying one’s own experience can generate greater reflexivity toward emotions, institutional feeling rules, and factors supporting or constraining wellbeing. Methodologically, autoethnography is an especially appropriate tool for investigating emotion as it holds vulnerability and emotional connectivity as central concerns (Mirhosseini 2018). Autoethnography offers the unique ability to forgo a “disembodied authorial academic voice” in favor of a “feeling and vulnerable” stance of reflexivity (Ellis and Bochner 2006: 441). Recent research (synthesized below) has demonstrated that it also offers teachers the potential to develop greater emotional reflexivity as they explore emotional experiences that can inform their pedagogy.

Focusing on pre-service language teachers, Yazan (2023) incorporated a critical autoethnographic narrative assignment into a teacher education course and observed how teacher candidates developed reflexivity by reinterpreting past emotional experiences and emotion labor in light of their developing teacher identities. Montgomery and Kudritskaya (2024) investigated their experiences as language educators navigating institutional anti-plagiarism policies by conducting a duoethnography involving collaborative written reflection and videoconference calls. The authors found that reflecting together about experiences of frustration, stress, and anxiety stemming from top-down anti-plagiarism policies led to feelings of confidence, professional solidarity, and a renewed sense of purpose as agentive, bottom-up policy negotiators. Liu et al. (2021) reported on an autoethnographic self-study of a language teacher who had shifted to online instruction during the Covid-19 pandemic. The authors found that self-study developed the teacher’s emotional reflexivity and ability to counter institutional feeling rules by engaging in reciprocal, bi-directional caring practices with students and validating colleagues’ emotions. Examining her own experience as a language teacher educator, Song’s (2022) self-study involved analyzing autoethnographic vignettes of challenges faced teaching in online modalities, demonstrating that critical reflection about vulnerable experiences can lead to a greater awareness of both students’ emotions and teacher educators’ own emotion labor.

In addition to highlighting the role of emotions at different career stages, autoethnography has explored the emotional experiences of language teachers navigating multiple and simultaneous roles. Cinaglia's (2023b) narrative approach to autoethnography, for example, involved short story analysis of written journal reflections made during his first year of doctoral study while transitioning from language teacher and teacher educator to novice researcher. He found that reflecting on identity tensions and challenges to his wellbeing resulted in a greater awareness of institutional discourses shaping his academic socialization. Cho (2023) similarly engaged in a collaborative autoethnography during her doctoral studies involving written narratives and routine meetings with two peers. The author found that emotional dissonance related to balancing and entering new teaching and research roles served as a springboard for professional development as she was able to change her behaviors in response to her emotional experiences. Pentón Herrera et al. (2022) also conducted a collaborative autoethnography to explore strategies for supporting their own wellbeing in response to stress from identity tensions related to responsibilities as graduate students, language teachers, and teacher educators. In all three studies, autoethnography serves as a powerful tool for developing greater reflexivity, awareness of one’s emotions, and agency in challenging emotionally inhospitable institutional discourses.

2.4 Examining language teacher emotion labor to promote wellbeing

Benesch and Prior’s (2023) call to return to the critical and poststructural origins of emotion labor research is in response to the construct often being equated broadly with the experience of negative emotions in general. Importantly, the authors emphasize that emotion labor is the management of emotions in response to external feeling rules. As such, we understand the goal of investigating and understanding teacher emotion labor as not just to reduce teachers’ experiences of negative emotion, but rather to uncover and interrogate institutional working conditions that may not validate teachers’ emotional experiences and that instead lead to teachers needing to control, hide, or perform their emotions in certain ways. Our commitment to this goal is informed by Mercer’s (2021) ecological view of language teacher wellbeing, which she describes as “the dynamic sense of meaning and life satisfaction emerging from a person’s subjective personal relationships with the affordances within their social ecologies” (p. 16). We interpret this definition of wellbeing to include more than simply experiencing positive emotions and to entail meaningful engagement and alignment with different contextual factors in individuals’ teaching ecologies. Our interpretation is informed by Benesch and Prior’s (2023) warning that designating emotions as positive or negative a priori can establish and reinforce feeling rules, which can ultimately constrain wellbeing by limiting meaningful engagement with teachers’ broader ecologies. We align with Mercer’s (2021) and Benesch and Prior’s (2023) shared goal of interrogating teachers’ working conditions in order to support teacher development and wellbeing.

2.5 The present study

The studies reviewed above illustrate how tension stemming from answerability to multiple commitments can result in both a range of emotions as well as emotion labor as teachers hide, perform, and regulate their emotions in relation to external feeling rules. These studies raise important questions for investigating teachers’ emotional experiences. Which emotions are deemed permissible, required, or prohibited? How does this create emotion labor for teachers caught in the middle of multiple commitments and obligations? While a growing body of research has begun to explore teachers’ experiences of emotion labor, less research has examined the emotional experiences of teacher educators as they support teachers in experiences of emotion labor. We situate our study in response to Song’s (2021) suggestion to engage in critical reflection about emotion labor to develop greater reflexivity and Gkonou and Miller’s (2021) call to explore emotional capital across contexts and levels of experience. In particular, we engage in critical reflection through collaborative autoethnography about emotion labor based on our experiences as language teachers and teacher educators having worked in a variety of institutional contexts. Our study is guided by the following questions: (1) How does emotion labor reflect answerability to multiple commitments in the face of feeling rules? (2) How does collaborative reflection about emotion labor generate emotional capital?

3 Methodology

Our collaborative autoethnography emerged from our experiences as language teachers, teacher educators, and teacher-researchers. While our prior experiences span a range of contexts and roles, one common thread is our shared interest in investigating the emotional experiences of language learners and teachers from an ecological perspective (Cinaglia et al. 2023; Montgomery et al. 2024). As doctoral researchers interested in the methodological approaches of autoethnography (Montgomery and Kudritskaya 2024) and narrative inquiry (Cinaglia 2023b), we engaged in systematic narrative reflection and dialogue to investigate how our experiences as language teachers and teacher educators speak to each other and shed light on tension, answerability, emotion labor, and emotional capital. Initially, our purpose was to understand how teacher educators might be able to support language teachers experiencing emotion labor; however, our focus shifted to include how we as teacher educators ourselves experience emotion labor. Thus, we compare our experiences as teacher educators with one another as well as with the experiences of our collaborating teachers, with the overall goal of understanding how collaboration might mitigate as well as reproduce emotion labor.

3.1 Introducing ourselves

Carlo has taught English as a second language (ESL) classes for immigrant and refugee students and academic ESL classes for international undergraduate students in the U.S. He has also taught Spanish as an additional language for U.S. university students. As a teacher educator, Carlo has taught undergraduate Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) and linguistics courses for U.S. university students preparing to be language teachers, and he currently mentors graduate student teachers pursuing TESOL master’s degrees and completing a teaching practicum. These collaborations have familiarized him with the experiences of pre-service teachers who negotiate the simultaneous demands of studying and teaching.

Philip’s teaching experience includes teaching English in Kazakhstan and Spanish in the U.S. In Kazakhstan, he taught English as an additional language to middle and high school students, and later English for academic purposes (EAP) to graduate students. In the U.S., he taught Spanish as an additional language in two affluent private high schools. His teacher educator roles include mentoring writing consultants as assistant director at the university’s writing center and teaching graduate TESOL courses for U.S. university students currently teaching in K-12 settings. These roles have required Philip to foster professional flexibility and to adapt his teaching practices to each institution’s curriculum and culture.

Matt has developed and taught courses and programs for both Spanish and Mandarin to learners from age three to age 80, ranging in proficiency from A1 to C2 in primary, secondary, university, professional (medical school), and private language center contexts. He has also worked as a teacher educator, primarily via workshops, invited presentations, and intensive teacher training programs for additional language teachers all over the U.S. and the world. These ongoing experiences teaching, collaborating, and training across two different language systems, and working with diverse language educators have pushed Matt to de-center his experiences and learn collaboratively with trainees and colleagues.

Our collaborative autoethnography is rooted in our prior experiences as language teachers and our current relationship as graduate students who regularly draw on each other for both academic and personal support. We do not frame our approach to collaborative autoethnography or our practices as teacher educators as ideals that others should follow; rather, our aim has been to reflect on our attempts at generating emotional capital for our collaborating teachers as well as for ourselves.

3.2 Procedures

Our approach to data generation and analysis is informed by Mirhosseini’s (2018) call to engage in autoethnography in TESOL research. We understand autoethnography to involve the practice of systematically studying (-graphy) our own experiences (auto-) in order to better understand the larger systems and institutions in which we function (-ethno-). By engaging in collaborative autoethnography, we aim to draw on our multiple perspectives and voices in a process of dialogic sense-making. Our approach is also informed by scholarship in narrative inquiry for language learning and teaching research (Barkhuizen et al. 2014). Autoethnography is a type of autobiographical narrative analysis that can involve using narrative as a sense-making tool (Benson 2018). For example, in the practice of restorying (Clandinin and Connelly 2000), data in story form are reconfigured using storytelling as a lens for both analysis and (re)presentation. Similarly, narrative knowledging (Barkhuizen 2013) can involve using narratives as data itself, an analytic lens, and a reporting tool. We engage in the processes of restorying and narrative knowledging by producing narrative recollections of our experiences, weaving these narrated episodes together to explore similarities and differences, and continuing to narrate our evolving understanding of our experiences.

We draw on three examples of collaborative autoethnography to guide our data generation and analysis processes. Similar to De Costa et al. (2022), who utilized reflective journal entries and collaborative interviews to examine their researcher-practitioner collaborations, we compared our reflections about working with collaborative teachers using both asynchronous written reflection and synchronous in-person discussion. In addition, we drew on Pentón Herrera et al.’s (2022) approach to examining their own experiences of wellbeing through multiple phases of collaborative reflection, including initial group discussion, individual written reflection, and ongoing group interpretation and analysis (summarized in Table 1). Finally, we adopted a similar focus as Deroo et al. (2022) and took a Small Moments Reflexive Inquiry approach to generating, analyzing, and presenting our data. For our purposes, this involved first producing shorter narrative snapshots of specific experiences, elaborating on these snapshots to produce longer, more detailed episodes, and then distilling these reflections into more condensed vignettes to weave together and (re)story our experiences.

Data generation and analysis procedures.

| Phase in process | Procedures |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Initial discussion of topics | Synchronous meeting to discuss themes and generate reflection protocol (see Appendix) |

| Phase 2: Individual narrative reflection | Responses to reflection protocol with brief narrative snapshots (250 words or less) in three separate shared online documents |

| Phase 3: Commentary | Brief responses to each other’s written reflections, including initial comments, questions, and reactions |

| Phase 4: Individual narrative reflection | Elaboration on our own written reflections to produce longer narrative episodes (750–1,000 words) in response to each other’s comments |

| Phase 5: Commentary | Responses to each other’s written reflections (no word limit), including follow-up comments, questions, and reactions, resulting in final corpus of 17,638 words |

| Phase 6: Initial analysis | Thematic analysis of all three written reflections for recurring topics and emergent themes |

| Phase 7: Collaborative analysis and reflection | Synchronous meeting to respond to each other’s reflections in-person, discuss emergent themes, and outline structure of paper |

| Phase 8: Drafting of paper | Condensing narrative reflections into shorter vignettes and reconfiguring to produce overall autoethnographic narrative |

All of our data generation and analysis procedures were conducted asynchronously, except for Phases 1 and 7, where we met in-person first to discuss initial themes and generate our reflection protocol and later on to regroup and discuss emergent themes after having produced our narrative reflections. Our in-person collaborative discussions afforded opportunities for reflection which shaped our analysis and writing. Given our interest in emotion labor resulting from answerability to multiple commitments in the face of institutional feeling rules (research question 1), we explored moments of tension in two ways: through reflecting on prompts focusing on wellbeing as well as on emotion labor. Although wellbeing was not our primary analytical focus, our intention in reflecting on (challenges to) wellbeing was to elicit examples of tension stemming from answerability to multiple commitments that resulted in different emotions. The examples generated provided useful context for our reflections on emotion labor, which were intended to elicit examples of feeling rules constraining emotions experienced in response to these moments of tension. Stemming from our interest in collaborative reflection as a source of emotional capital (research question 2), we sought to elicit examples of tension on three levels: our experiences as language teachers, our experiences working with language teachers, and our experiences as teacher educators. Key themes that emerged from our writing and discussion included (a) moments of tension, (b) (mis)alignment between practices, expectations, and values, and (c) negotiating answerability to ourselves, students, colleagues, and institutions. Below, we present our findings across three (synthesized) themes: (1) Our experiences as language teachers; (2) Our experiences supporting our collaborating teachers; (3) Our experiences supporting each other. Some examples presented are sequential threads of individual reflections (Phase 4) and commentary (Phase 5), and other examples presented are separate individual reflections that are reconfigured (Phase 8) to illustrate a common theme.

4 Findings

4.1 Our emotion labor as language teachers

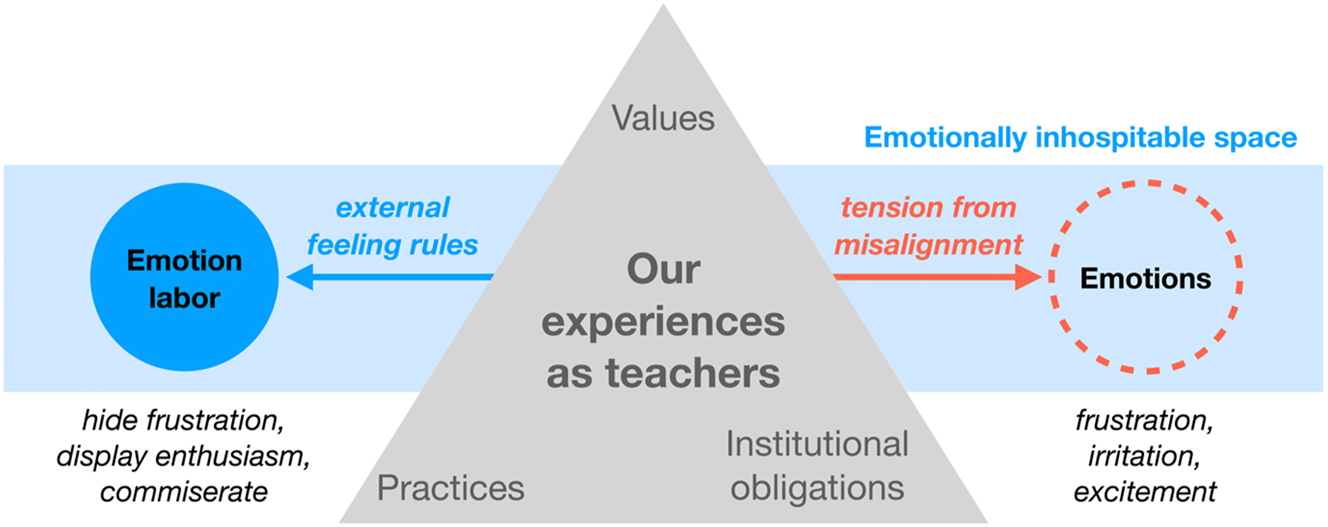

Our narrative reflection first focused on our own experiences of emotion labor as language teachers. An emerging theme was managing frustration stemming from tension between our individual pedagogies and the institutional expectations we faced, illustrated in Figure 3.

Carlo: I often had to teach 8am classes, and 18-year-old students usually didn’t like that. They were tired or just didn’t seem to care to be there. I was frustrated that they seemed apathetic. I tried to not reveal this frustration, so I hid my negative emotion and tried to be positive and energetic around them. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Philip: My [secondary school] students decided to give me the silent treatment in class one day. I struggled to get them to engage, but no one would talk. I found myself confused and monologuing in front of them. I finally caught on to the fact that I was the butt of the joke and had no idea how to respond in the moment. I stewed over it all night and decided to write them a letter, which I read out loud in class the next day, explaining how much I care about communicating with them, and how the whole thing falls apart and I lose my purpose as a teacher if they refuse to engage. They apologized sincerely, having no idea how much their little prank affected me […] I felt like the letter would allow me to resolve the issue internally for myself, and externally for them to know me a bit better as a person, not just as a teacher. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Our emotion labor mitigating emotional responses to tension.

In both of these examples, Carlo and Philip experienced frustration resulting from a misalignment between classroom interaction and their pedagogical goals. However, whereas Carlo’s emotion labor in hiding his frustration reflects his answerability to the expectation that teachers remain enthusiastic and positive, Philip’s decision to disclose his emotions reflects an attempt to align his practices with his values and enact meaningful engagement with his students. While the examples above illustrate the power of feeling rules in constraining how we revealed our emotion, the examples below point to ways we tried to intentionally push back against feeling rules in moments of tension.

Carlo: I didn’t like aspects of the textbook or curriculum, so I openly showed my disdain for these parts of the class, hoping to win favor with the students. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Matt: I did that too, but it was something I felt conflicted about. I wasn’t sure if sowing dissent was ultimately going to make life easier or better for the students, or whether they would respect me for challenging what I thought was wrong, or just think I didn’t know what I was doing. I often did end up sharing my frustrations because I couldn’t contain it, or because students directly asked me and I decided I didn’t want to lie, but the inner conflict was real. (Commentary, Phase 5)

Philip: I complained openly [to students] about the textbook in my Spanish HS gig. I also thought it might “win favor” and in a way, it did. Sometimes we did the grammar “because we had to”, and I could gripe about it along with the students. (Commentary, Phase 5)

In all three examples, our emotions of disdain, frustration, and complaint reflect a misalignment between our own pedagogical values and the curriculum we were each expected to enact. In Carlo’s example, his decision to violate an institutional feeling rule of displaying enthusiasm was an intentional choice to be transparent and win favor with students, perhaps following their local feeling rule of not showing too much excitement about Spanish class. Interestingly, while Philip’s decision to disclose his frustration seems to have a similar rationale as Carlo’s, his being able to “gripe” and Matt’s inability to “contain” his emotions also point to the need to have one’s emotions validated. In light of Benesch and Prior’s (2023) view of institutions as emotionally inhospitable spaces, it is worth considering the consequences of teachers not having their emotions validated. Matt’s reflection below begins to capture this experience as he discusses emotion labor faced when dealing with unsupportive colleagues:

Matt: My first year teaching at [university name], I remember being both so excited and at the same time so frustrated. I was ready to share with and learn from my colleagues, but every time I offered different suggestions or new ideas, they were unreceptive. I remember this intense frustration with having to teach in a way I knew wasn’t good for learning. Because I was “temporary” and contingent, I felt like I couldn’t even have an honest conversation with anyone to express the frustration. The worst was when students asked [about my opinions of the effectiveness of the language program’s pedagogical approach, since I was/am a second language user myself] and I had to decide whether to be true to my beliefs, knowledge, and experience, or to “support the party line”. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

As the examples above show, we each experienced a range of emotions stemming from misalignment between our pedagogical values and our classroom experiences and institutional obligations. In different ways, feeling rules led to us either hiding or revealing our emotions to others.

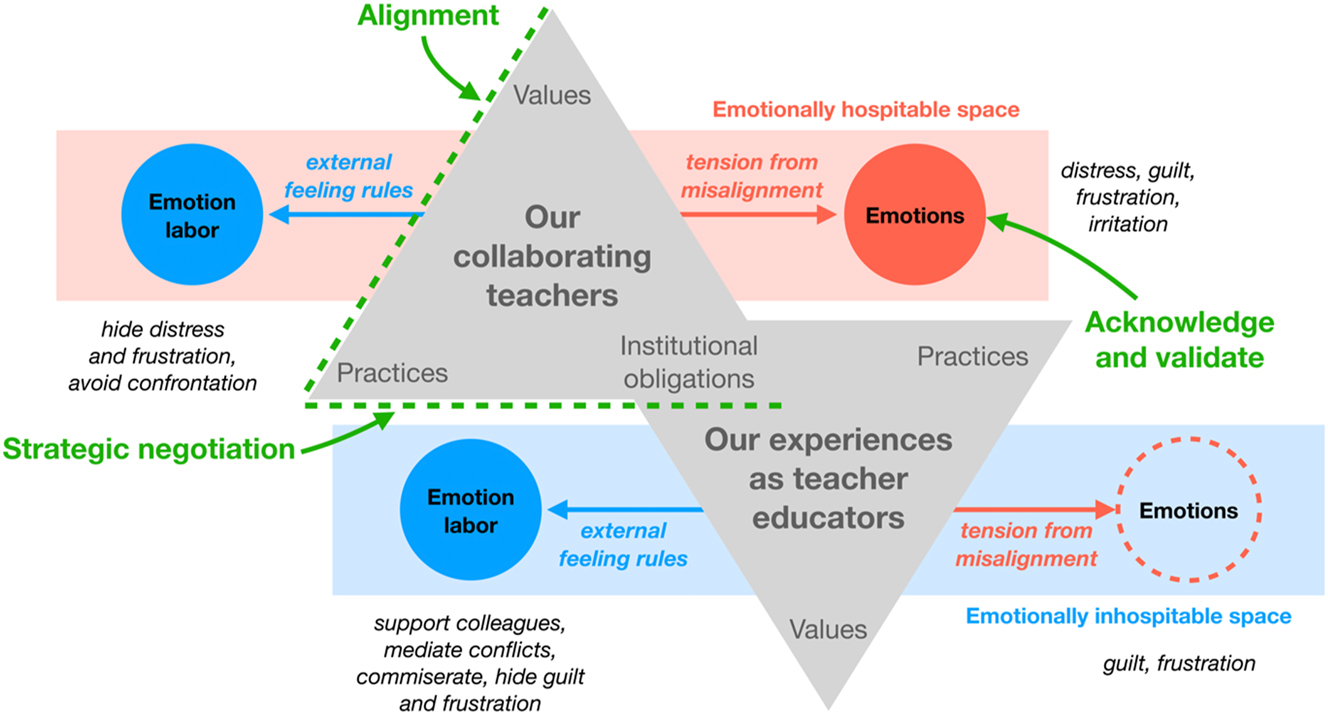

4.2 Supporting our collaborating teachers: their emotional capital, our emotion labor

The second focus of our narrative reflection was how we have supported our collaborating teachers when they experienced emotion labor. One emerging theme was our acknowledgment and validation of our collaborating teachers’ feelings of distress and frustration stemming from tensions they experienced, as illustrated in Figure 4. The red background in the top half of the image represents our attempts to create what we describe as an emotionally hospitable space for our collaborating teachers where their emotions are validated and able to be authentically experienced, represented by the solid red “Emotions” circle. The green text, dotted lines, and arrows represent how we tried to develop our collaborating teachers’ emotional capital. This led to emotion labor for us, represented by the blue background in the bottom half of the image with the dotted line around the “Emotions” circle.

Our attempts to support our collaborating teachers.

Carlo and Matt’s examples below illustrate our attempts to support our collaborating teachers.

Carlo: Two recent TESOL mentee teachers I worked with were freaking out after teaching a class because they went overtime and their lesson was interrupted by an alarm in their building. They felt guilt and discouragement for not “exercising good time management”, and then they felt guilty for becoming visibly distressed in front of their students. I told them that feeling was part of the process of teaching and not something to ignore. I feel like their program encourages them to pay attention to their thoughts as reflective practice, but not their feelings. I’ve found myself encouraging my mentees to pay attention to their emotions as a way to understand external factors that may lead to them feeling a certain way. My goal in highlighting institutional obligations and external forces was to blame the system in a way (and let them off the hook) but also to encourage them to develop an ecological lens and think about how they are able to work within this system to do things that feel right to them. (Commentary, Phase 5)

Matt: Once, a teacher I worked with in China was tutoring a student who was completely demotivated by his school experience. She (the teacher) struggled to help him. On the one hand, she was confident that a communicative approach to tutoring would help him see learning English as not boring and develop his language skills. But since the only evaluation criteria for the student (and therefore, the teacher) was the student’s test scores, the teacher never “dared” to try anything except the test-prep approach she hated “because she had a responsibility to the kid and his family who paid her” […] I asked her to think, “given the constraints of this real situation, what is the closest you can get to not feeling awful but not conflicting with your value of the parents’ and students’ needs and wishes?” This thought exercise seemed to help the teacher feel like she was still doing better than nothing and was still closer to her own principles than if she was just completely following the status quo […] I wanted to help the teacher see that her frustration was actually a manifestation of her strong desire for the student to succeed […] and give her permission to do what the students’ parents wanted to the best of her ability. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Philip: I love the idea of explicitly talking about feelings as indicators of what is working or not, and to pinpoint the sources of each emotion. Emotion is then a resource rather than an obstacle. (Commentary, Phase 5)

In both examples, our collaborating teachers experienced negative emotions they felt the need to hide. In both cases, we attempted to create emotionally hospitable spaces by validating our collaborating teachers’ emotions as a point of reflection about the wider contexts in which they were teaching. Our aims were to let them off the hook and ‘give them permission’ to fully experience their emotions and to continue making the decisions they were making. Philip’s response encapsulates our goal of developing our collaborating teachers’ emotional capital (Gkonou and Miller 2021) by utilizing emotions as resources instead of as problems.

While our goal was to help our collaborating teachers develop emotional capital in response to emotion labor, our attempts to support them at times have resulted in our own emotion labor:

Philip: An in-service teacher in my asynchronous online research methods class was upset because of the interactions she had with her group about equal contribution to a group assignment. Over email and a Zoom call, I found myself playing different roles, all of which are harder to do in an asynchronous format: the cheerleader (I want her to succeed with her group …), the conflict mediator (… even though accusations of not pulling one’s weight have been said and feelings have been hurt), the fair judge (I will not dock this student points in the future), and the boundary enforcer (no, she can’t just drop out of the group assignment). Despite the tears that were shed, I think we resolved the issue, and I feel like I was able to guide her through a tough interaction, fully acknowledging that my course structure and assessment practices contributed to the conflict. What a roller coaster. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Carlo: Two TESOL student teachers and peer mentors recently complained to me about their mentees (peers in their program), highlighting their mentees’ lack of knowledge and experience and their being non-receptive to their assigned roles/responsibilities. My sense was they were not comfortable directly confronting their mentees about this, so they used the private space of reflective conversation with me to bring this up and vent about it. Not only did I listen with open ears, but I even engaged in complaining about the mentees with them. My goal in the moment was to align with their irritation. I’ve been in their situation in the past and I have worked with uncooperative peers/colleagues. Part of me felt guilty though because I don’t want to enable their overly critical attitudes. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

In both examples, our collaborating teachers hid feelings of frustration stemming from uncooperative peers in order to preserve group harmony. Our approaches to create safe spaces for them to share their feelings conflicted with our own responsibilities to the larger institutions where we work. In Philip’s case, he had to navigate multiple roles and emotions by balancing providing support and enforcing the rules. In Carlo’s case, the irritation he performed to align with his collaborating teachers conflicted with the guilt he felt (and hid) for not discouraging overly critical peer mentoring practices. Just as the emotion labor experienced by our collaborating teachers reflects tension in the face of feeling rules, our own emotion labor in supporting their tension reflects our answerability to multiple commitments in light of additional feeling rules, causing us to withhold or perform emotions in different ways.

4.3 Supporting each other as teacher educators: reframing emotion labor as emotional capital

Whereas our attempts to support our collaborating teachers involved creating emotionally hospitable spaces for them, we found that our narrative reflection served as a space for us to share and have our own emotions validated by each other, as illustrated in Figure 5. In this figure, the green text, dotted lines, and arrows represent how we reframed our own emotion labor as emotional capital, and the red background and solid red “Emotions” circle represent the emotionally hospitable space that was created through our collaborative autoethnography.

Creating an emotionally hospitable space for ourselves through collaborative autoethnography.

As the below examples illustrate, reflecting on our emotion labor as teacher educators allowed us to generate emotional capital by highlighting (a) alignment with our pedagogical values and (b) strategic negotiation of the institutional contexts in which we work.

Matt: An area where I continue to struggle is dealing with the repercussions of achieving buy-in with teachers to make a change in their practice […] The struggle is, you convince teachers that this change has positive potential consequences, and they believe you. But then they have to go deal with implementation in a potentially highly unreceptive context, a context in which I am an outsider and have little potential to affect change, and they also have limited power […] It may not be worth it to fight if it means losing their jobs … (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Carlo: Two mentee teachers I worked with recently got frustrated at my suggestion to focus on particular content or use a particular framework for their lesson plans, insisting instead that they make these decisions based on what their students wanted from their class. They seemed to experience tension between obligation to their students and obligation to their mentors/supervisors (i.e., my feedback and their ultimate course grades). I experienced tension between my obligation to them and my obligation to my employer (i.e., their department and its pedagogical goals). I felt guilty and frustrated, but I was unsure about whether to disclose these feelings to them. Their frustration came out when they felt the need to show me this alignment. I hid my frustration and decided their alignment should be recognized in this moment instead of mine. (Commentary, Phase 5)

Philip: Caught in between competing commitments. Emotion labor as the work to bring them into alignment, or to find a resolution to live with them being misaligned. (Commentary, Phase 5)

Together, Matt and Carlo’s examples reflect tension between impatience or frustration on the one hand (our collaborating teachers are not taking up our suggestions) and guilt on the other hand (trying to make pedagogical suggestions in contexts where we are not teaching). Philip acknowledges the emotion labor resulting from aligning with or choosing between competing obligations. Carlo’s decision reflects being answerable to his mentees’ alignment and rationale instead of to his own, and Matt’s stance reflects prioritizing his collaborating teachers’ judgment about when to implement pedagogical change. Although our decisions may not align with our pedagogical rationales at first, the positions we adopt do ultimately align with our shared values of developing teacher education practices that center our collaborating teachers.

In addition to drawing attention to alignment in our teacher education practices, our collaborative reflection generated emotional capital highlighting how we engaged in strategic negotiation of our respective institutional contexts.

Carlo: I have to evaluate my mentees’ performance using a “glows and grows” form to categorize their practices as essentially good/bad and improved/unimproved, which determines part of their course grade. What I don’t like about this form is that it doesn’t always acknowledge the ways their pedagogy has developed based on their ongoing reflection about emergent topics and practices, so according to the form as the program has designed it, it might look like the teachers aren’t “improving” in certain areas. I know the emotional stress they have toward their grades, so I’ve kind of repurposed the form in a way that makes sense to me. I don’t want to show my frustration to my mentees for fear of speaking poorly about their program, and I’ve never complained to the faculty because I don’t want to lose my mentoring job. This past semester though was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I got uncomfortable enough to say something to the program coordinator about it. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Matt: I think the reframe here may be that you are now just a savvy player in the game that the institution has created. Maybe it’s the system in place that isn’t putting the teachers and their needs first, and by navigating the system in this insider-informed way, you are doing something the system has not yet or maybe cannot yet do. No guilt in it as far as I see. As long as you see the teachers learning and growing in some direction (rubric or not), the goal of the program (people growing along their own path, not some standardized one-size-fits-all path) is being met. Glows all around. (Commentary, Phase 5)

Carlo’s example reflects emotion labor stemming from tension between being answerable to his mentee teachers and to their program’s curricular expectations while also feeling the need to withhold feelings of frustration when interacting with both parties. Matt’s response validates Carlo’s emotions of guilt while offering additional perspective: Carlo’s emotion labor in not raising the issue at first can be seen as strategic negotiation of institutional policy that provides relevant feedback for his mentees while not jeopardizing his own position as an employee of the university. In another example, Philip writes about tension stemming from his dual roles as graduate student and Writing Center administrator:

Philip: I feel tension as a grad student and assistant director of the Writing Center. I am supposed to be prioritizing my academic work [as a student], but my role [as a graduate assistant] is taken over by the many needs (both logistical and emotional) of the consultants in the center. I want to be there for everyone all the time, so I have a really hard time doing my own writing or coursework – to the point that I don’t plan to do a graduate assistantship in the Writing Center next year. Something is out of balance, but I’m not sure exactly how to pinpoint it … Sometimes I feel used up from my [graduate assistant] job and have less energy to tackle my own research. What is really challenging is that I love the emotional engagement with consultants. I feel good about supporting them and being someone who they can talk to about tough sessions. But because I can’t disengage so well to create space for my own research work, I decided that an intentional reprioritization in my final year was necessary. My hope is that this will demand less emotion labor from me, which I predict will save mental and emotional space for my dissertation work. (Individual reflection, Phase 4)

Carlo: In a way, you are enacting agency in prioritizing your wellbeing and managing how you engage with different people and aspects of the different programs you inhabit. You want to engage meaningfully in spaces and with work that are important to you, but you’re doing it on your terms. (Commentary, Phase 5)

Whereas Carlo’s example above reflects answerability to multiple commitments as a source of emotion labor, Philip’s example here reflects emotion labor as one of multiple commitments he must balance and a source of tension that challenges his wellbeing. Carlo’s response attempts to acknowledge Philip’s emotion and draw attention to his agentive prioritization of his responsibilities and commitments within his university. Although Philip leaving the Writing Center administrator job might mean providing less direct emotional support for Writing Center consultants, his ability to focus on his own doctoral research examining how the Writing Center policy is enacted via consultants’ experiences can still allow Philip to engage in meaningful work that aligns with his values and priorities.

5 Discussion

The present study contributes to research on language teacher emotion labor by examining teachers’ emotions resulting from tension between answerability (Bernstein 2019) to multiple commitments in the face of external feeling rules (Benesch 2017). Our own experiences and those of our collaborating teachers involved tension between commitments to students, colleagues, institutional and curricular obligations, and individual pedagogical values, which led to feelings of frustration and irritation. In some situations, similar to Gkonou and Miller’s (2019) and Pereira’s (2018) findings, our emotions were suppressed to perform enthusiasm, professionalism, and deference to colleagues. In other situations, our emotions were overtly disclosed to win favor with students and explicitly address tension. This decision or desire to disclose such emotions reflects a need for teachers’ emotions to be acknowledged and validated by others. While Philip’s example of addressing tension with his class reflects agency in enacting meaningful engagement with students, Matt’s example of not being able to voice his frustrations to colleagues raises questions about whether such relationships serve as institutional cultures of care (Cinaglia et al. 2023) that support teacher agency and wellbeing or as emotionally inhospitable spaces (Benesch and Prior 2023) that prohibit authentic emotional experiences.

In addition, this study extends research on language teacher emotion labor by focusing on the role of the teacher educator in developing teachers’ emotional capital. Gkonou and Miller (2021) observed language teachers generating emotional capital by comparing emotional experiences and developing resources to negotiate institutional expectations for how they performed emotions. In our roles as teacher educators, we attempted to create what we describe as emotionally hospitable spaces by explicitly validating our collaborating teachers’ emotional experiences. In line with Song’s (2021) observation that critical reflection about emotion labor can generate emotional reflexivity, we encouraged our collaborating teachers to view their emotions as reflective of their pedagogical values and negotiation of institutional expectations.

The present study also adds complexity to our understanding of language teacher emotion labor and emotional capital. Whereas scholars have suggested that emotion labor can serve as a catalyst for emotional capital (Benesch 2017; Gkonou and Miller 2021; Song 2021), our findings show how efforts to generate emotional capital can not only mitigate emotion labor, but also reproduce it. Our efforts as teacher educators to support our collaborating teachers at times led to emotion labor for ourselves. Such emotion labor stemmed from having to occupy multiple different roles in relation to our collaborating teachers, including providing emotional support and adhering to curricular or institutional policies. This finding reflects the socially situated nature of emotion labor as well as the role language teachers and teacher educators can play as social actors within each other’s wider social ecologies.

Finally, this study contributes to research examining language teacher educator emotion labor by illustrating how (collaborative) autoethnography can generate reflexivity and emotional capital. Previous studies have illustrated reflexivity as a major affordance of autoethnography for language teachers. For example, Yazan (2023) observed teacher candidates’ use of autoethnography to reinterpret past emotional experiences in light of their developing identities as generating reflexivity in the form of new understandings of their pedagogical practices. Our collaborative autoethnography similarly involved reinterpreting and reframing each other’s emotion labor in light of our own perspectives and experiences to develop a greater understanding of our institutional contexts and pedagogical practices as teacher educators. Furthermore, in response to the emotion labor we experienced working with our collaborating teachers, our collaborative autoethnography functioned as an emotionally hospitable space where we could explicitly validate each other’s emotional experiences. Together, we were able to generate emotional capital by recognizing each other’s alignment with our pedagogical values as well as strategic negotiation of our respective institutional contexts.

6 Implications

In their study of language teachers’ emotional capital, Gkonou and Miller (2021) encouraged language teachers and teacher educators to “critique, contextualize, and practice reflexivity” in relation to emotion labor and emotional capital (p. 151). We have attempted to support our collaborating teachers and each other by validating emotions and using them as points of reflection to develop greater reflexivity about our institutional contexts. Language teachers and teacher educators alike would benefit from emotionally-focused reflection, whether done individually, in groups, or with a trusted colleague or mentor. However, such collaborative reflection may not always be a viable, sustainable, or practical solution for language teachers and teacher educators in all contexts.

As noted previously, Benesch and Prior (2023) emphasize that one goal of emotion labor research is to interrogate institutional working conditions that create emotionally inhospitable spaces for language teachers. Returning to our earlier examples of tension and emotion labor as language teachers, it is worth considering how the working conditions we experienced might be reimagined in order to reduce tension and validate emotion. We each worked as contingent, part-time instructors in high school or university language programs – positions that involved less decision-making power than our relative colleagues. Since our experiences of misalignment related to our enactment of a curriculum that did not always align with our values, language teachers in such contexts ought to have a say in textbook adoption, curriculum development, and pedagogical approaches they enact in their classrooms. Similarly, since our emotion labor resulted in having to withhold feelings of frustration in classroom spaces, it is worth considering the extent to which language teachers in such programs have the space to voice emotions related to curricular and instructional processes, either during planning meetings or in more informal teacher reflection settings. Given teachers’ busy schedules, this might not happen without dedicated time and space. For example, in one of the university language programs where Carlo used to teach, routine peer coaching and professional development sessions were offered; however, these opportunities were usually only attended by full-time faculty since part-time faculty were often busy teaching multiple classes at different universities – a necessity given the low wages part-time instructors received.

Examining our collaborating teachers’ experiences of emotion labor sheds additional light on the precarity of emotional support many language teachers likely face. In Carlo’s example of pre-service language teachers in a teacher education program, emotion labor stemmed from a perceived expectation that teachers display certain emotions while hiding others in order to present a professional disposition to students. Teachers in such programs are typically required to complete routine reflection assignments analyzing their teaching beliefs and practices in order to become ‘thinking teachers’, but to what extent do such reflective practices prioritize developing ‘feeling teachers’ (Cinaglia) by incorporating emotion as an element of reflection? In contrast to the structure of teacher education programs, Matt’s example of a private tutor reflects how the precarity of language teaching work often involves vulnerability to emotion labor in situations where teachers have less power. When tutors must comply with customers’ wishes or demands and often work without a formalized institutional support network, where are they able to turn for emotional validation?

Finally, our unique roles as teacher educators raise several questions for how institutions might support the emotional experiences of teacher educators in similar situations. In Philip’s case, he is a part-time instructor teaching a remote, online, asynchronous course in a teacher education program at one institution. In addition to this, he works as a graduate student himself at a different institution, where he also works as an administrator in his university’s Writing Center. Does his part-time teaching institution create spaces for instructors like Philip to share their emotional experiences and have their feelings validated? If these spaces exist, are they realistically accessible for instructors who balance several different roles at the same time? In Carlo’s case, he works as a mentor to pre-service language teachers in a graduate TESOL program at a different institution than his own graduate program, similar to Philip. Most of the mentors who support pre-service teachers in this TESOL program work outside of this institution and hold one or more additional teaching positions as their primary job. Does the TESOL program create spaces for mentors like Carlo to share their emotion labor experiences working with mentee teachers? If so, are these spaces similarly accessible to mentor teachers who have busy schedules of their own? The three of us were able to engage in collaborative reflection to create an emotionally hospitable space for ourselves on our own schedule, but this space emerged out of our intersecting roles and shared interests as graduate students in the same program. Collaborative reflection as peers is one source of bottom-up emotional capital, but it may not be realistic to expect all teachers and teacher educators to be able to do this. Centering emotion and emotion labor in structured reflection activities for teachers at all stages of their career will work toward creating emotionally hospitable spaces that allow for authentic emotional experiences and meaningful engagement with others, which is the core of language teacher wellbeing (Mercer 2021).

7 Future research

Our goal and purpose in engaging in collaborative autoethnography was to develop our own reflexivity about our practices as teacher educators. As such, our recommendations for future research do not necessarily imply limitations to our methodological constraints or choices, but rather are intended to extend and contribute to the body of scholarship in which we situate this study (Montgomery 2023). The present study examined how language teacher educators attempted to create emotionally hospitable spaces for collaborating teachers in response to moments of emotion labor. Future studies can expand upon these findings by considering language teachers’ perspectives toward emotion labor in relation to their collaboration with teacher educators. Such approaches might exhibit complexity around how such collaborations function as emotionally hospitable or inhospitable spaces. Additionally, future research could examine the experiences of teacher educators working within the same institutional context. While our experiences as teacher educators in different contexts may have served as an additional point of comparison, focusing on teacher educators’ experiences within one institution might work well to generate emotional capital and reflexivity within that specific context, especially in contexts where teacher educators’ roles and responsibilities are more isolated or less structured.

In terms of methodological design, future collaborative autoethnographic studies may wish to go beyond using asynchronous written reflection and synchronous group discussion as data generation procedures. Additional approaches, such as analyzing recordings of interactions between language teachers and teacher educators (see Cinaglia 2023a) or documents and artifacts generated from their collaboration, could offer complementary perspective to the retrospective reflective practices employed in the present study. Finally, future research would do well to examine language teacher educators’ experiences of emotion labor over longer periods of time. While the present study involved a collaborative reflection procedure occurring over a span of several weeks, more sustained engagement with such practices (see Cho 2023; Song 2022) would likely reveal further complexity of the evolution of teachers’ and teacher educators’ emotional experiences. Language teachers and teacher educators are social actors working within each other’s wider ecologies. Further investigation of their emotional experiences as ecologically situated (Mercer 2021) and socially and institutionally shaped (Benesch and Prior 2023) is necessary in order to interrogate and advocate for institutional working conditions that can serve as emotionally hospitable spaces.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The author(s) state(s) no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

Appendix: Narrative reflection protocol

Our experiences as language teachers

In what context(s) have you worked as a language teacher?

Describe a time when your wellbeing as a language teacher was supported.

Describe a time when your wellbeing as a language teacher was challenged.

Describe a time when you experienced emotion labor as a language teacher.

Our experiences working with language teachers

In what context(s) have you worked as a language teacher educator?

How did you arrive to this work and these contexts? What do you understand your purpose to be as a teacher educator? What are 1–2 guiding values that shape your practice as a teacher educator?

How is this similar to or different from the context(s) you worked in as a language teacher?

Describe a time when the wellbeing of the language teachers you worked with seemed supported. What did this look like?

Describe a time when the wellbeing of the language teachers you worked with seemed challenged. What did this look like? As a teacher educator, what was your reaction/response to this situation?

Describe a time when the language teachers you worked with experienced emotion labor. What did this look like? As a teacher educator, what was your reaction/response to this situation?

Based on these experiences, what would an alternative experience for language teachers look like where their wellbeing is supported? In this scenario, what role might you play as a language teacher educator?

Our experiences as language teacher educators

Describe a time when your wellbeing as a language teacher educator was supported.

Describe a time when your wellbeing as a language teacher educator was challenged.

Describe a time when you experienced emotion labor as a language teacher educator.

Describe one way you have noticed your practices as a language teacher educator changing over time.

References

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1990. Art and answerability: Early philosophical essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barkhuizen, Gary. 2013. Narrative research in applied linguistics. Cambridge: University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barkhuizen, Gary, Phil Benson & Alice Chik. 2014. Narrative inquiry in language teaching and learning research. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203124994Search in Google Scholar

Benesch, Sarah. 2017. Emotions and English language teaching: Exploring teachers’ emotion labor. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315736181Search in Google Scholar

Benesch, Sarah & Matthew T. Prior. 2023. Rescuing “emotion labor” from (and for) language teacher emotion research. System 113. 102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.102995.Search in Google Scholar

Benson, Phil. 2018. Narrative analysis. In Aek Phakiti, Peter De Costa, Luke Plonsky & Sue Starfield (eds.). The Palgrave handbook of applied linguistics research methodology, 595–613. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-137-59900-1_26Search in Google Scholar

Bernstein, Katie A. 2019. Ethics in practice and answerability in complex, multi-participant studies. In Doris S. Warriner & Martha Bigelow (eds.). Critical reflections on research methods: Power and equity in complex multilingual contexts, 127–142. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788922562-011Search in Google Scholar

Cho, Eunhae. 2023. Rethinking the role of emotional dissonance in catalyzing professional development. In Bedrettin Yazan, Ethan Trinh & Luis Javier Pentón Herrera (eds.), Doctoral students’ identities and emotional wellbeing in applied linguistics: Autoethnographic accounts, 133–147. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003305934-12Search in Google Scholar

Cinaglia, Carlo. 2023a. Collaborative complaints, alignment, and identity positioning during teacher-mentor post-observation meetings. Journal of Language, Identity and Education. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2023.2282694.Search in Google Scholar

Cinaglia, Carlo. 2023b. Navigating the first year of doctoral study: Developing a researcher identity and other lessons learned outside of the program handbook. In Bedrettin Yazan, Ethan Trinh & Luis Javier Pentón Herrera (eds.). Doctoral students’ identities and emotional wellbeing in applied linguistics: Autoethnographic accounts, 148–171. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003305934-13Search in Google Scholar

Cinaglia, Carlo. Under review. Balancing technical, emotional, and reflective mentoring support to develop thinking and feeling teachers.Search in Google Scholar

Cinaglia, Carlo, D. Philip Montgomery & Peter I. De Costa. 2023. Teaching-as-caring and caring institutions: An ecological view of TESOL teacher well-being. The European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL 12(1). 191–211. https://doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/kf4et.Search in Google Scholar

Clandinin, D. Jean & F. Michael Connelly. 2000. Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

De Costa, Peter I., Gajasinghe Kasun, Laxmi P. Ojha & Amr Rabie-Ahmed. 2022. Bridging the researcher–practitioner divide through community-engaged action research: A collaborative autoethnographic exploration. The Modern Language Journal 106(3). 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12796.Search in Google Scholar

De Costa, Peter I., Wendy Li & Hima Rawal. 2019. Teacher emotions. In Michael A. Peters (ed.), Springer encyclopedia of teacher education. Singapore: Springer.Search in Google Scholar

De Costa, Peter I. & Bonny Norton. 2017. Identity, transdisciplinarity, and the good language teacher. The Modern Language Journal 101-S. 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12368.Search in Google Scholar

Deroo, Matthew R., Ryan W. Pontier & Tian Zhongfeng. 2022. Engaging opportunities: A small moments reflexive inquiry of translanguaging in a graduate TESOL course. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 21(3). 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2022.2058511.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Carolyn S. & Arthur P. Bochner. 2006. Analyzing analytic autoethnography: An autopsy. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4). 429–449.10.1177/0891241606286979Search in Google Scholar

Gkonou, Christina & Elizabeth R. Miller. 2019. Caring and emotional labour: Language teachers’ engagement with anxious learners in private language school classrooms. Language Teaching Research 23(3). 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817728739.Search in Google Scholar

Gkonou, Christina & Elizabeth R. Miller. 2021. An exploration of language teacher reflection, emotion labor, and emotional capital. Tesol Quarterly 55(1). 134–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.580.Search in Google Scholar

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Oakland: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Shuwen, Rui Yuan & Chuang Wang. 2021. ‘Let emotion ring’: An autoethnographic self-study of an EFL instructor in Wuhan during COVID-19. Language Teaching Research 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211053498.Search in Google Scholar

Mercer, Sarah. 2021. An agenda for well-being in ELT: An ecological perspective. ELT Journal 75(1). 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa062.Search in Google Scholar

Mirhosseini, Seyyed-Abdolhamid. 2018. An invitation to the less-treaded path of autoethnography in TESOL research. TESOL Journal 9(1). 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.305.Search in Google Scholar

Montgomery, D. Philip. 2023. “This study is not without its limitations”: Acknowledging limitations and recommending future research in applied linguistics research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 65. 101291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101291.Search in Google Scholar

Montgomery, D. Philip, Carlo Cinaglia & Peter I. De Costa. 2024. Enacting well-being: Identity and agency tensions for two TESOL educators. In Zia Tajeddin & Bedrettin Yazan (eds.), Language teacher identity tensions: Nexus of agency, emotion, and investment, 212–230. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003402411-17Search in Google Scholar

Montgomery, D. Philip & Marina Kudritskaya. 2024. Navigating anti-plagiarism software in Kazakhstan: A duoethnographic reflection. In Estela Ene, Betsy Gilliland, Sarah Henderson Lee, Tanita Saenkhum & Lisya Seloni (eds.), EFL writing teacher education and professional development: Voices from under-represented contexts, 45–53. Bristol:Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781800415140-008Search in Google Scholar

Pappa, Sotiria, Josephine Moate, Maria Ruohotie-Lyhty & Anneli Eteläpelto. 2019. Teacher agency within the Finnish CLIL context: Tensions and resources. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(5). 593–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1286292.Search in Google Scholar

Pavlenko, Aneta. 2013. The affective turn in SLA: From ‘affective factors’ to ‘language desire’ and ‘commodification of affect’. In Danuta Gabryś-Barker & Joanna Bielska (eds.). The affective dimension in second language acquisition, 3–28. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.Search in Google Scholar

Pentón Herrera, Luis Javier, Ethan T. Trinh & Manuel De Jesús Gómez Portillo. 2022. Cultivating calm and stillness at the doctoral level: A collaborative autoethnography. Educational Studies 58(2). 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2021.1947817.Search in Google Scholar

Pereira, Andrew J. 2018. Caring to teach: Exploring the affective economies of English teachers in Singapore. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics 41(4). 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2018-0035.Search in Google Scholar

Song, Juyoung. 2021. Emotional labour and professional development in ELT. ELT Journal 75(4). 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab036.Search in Google Scholar

Song, Juyoung. 2022. The emotional landscape of online teaching: An autoethnographic exploration of vulnerability and emotional reflexivity. System 106. 102774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102774.Search in Google Scholar

Yazan, Bedrettin. 2023. Incorporating teacher emotions and identity in teacher education practices: Affordances of critical autoethnographic narrative. Language Learning Journal 51(5). 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2023.2239843.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Emotion as pedagogy: why the emotion labor of L2 educators matters

- Research Articles

- “I’ve just lived inside a tumble dryer”: a narrative of emotion labour, (de)motivation, and agency in the life of a language teacher

- Emotion labor in teacher collaboration: towards developing emotional reflexivity

- Teacher emotions and the emotional labour of modern language (ML) teachers working in UK secondary schools

- Emotional labor of a Brazilian public school teacher: domination and resistance in a neoliberal context

- Translanguaging and emotionality of English as a second language (ESL) teachers

- Emotion labor in response to supervisor feedback: is feedback a burden or a blessing?

- She is “just an intern”: transnational Chinese language teachers’ emotion labor with mentors in a teacher residency program

- Emotionally (in)hospitable spaces: reflecting on language teacher–teacher educator collaboration as a source of emotion labor and emotional capital

- Teaching English in an engineering international branch campus: a collaborative autoethnography of our emotion labor

- Commentary: exploring “the pinch” of emotion labor in language teacher research

- Advancing language teacher emotion research: a nuanced, dialectical, and empowering stance

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Emotion as pedagogy: why the emotion labor of L2 educators matters

- Research Articles

- “I’ve just lived inside a tumble dryer”: a narrative of emotion labour, (de)motivation, and agency in the life of a language teacher

- Emotion labor in teacher collaboration: towards developing emotional reflexivity

- Teacher emotions and the emotional labour of modern language (ML) teachers working in UK secondary schools

- Emotional labor of a Brazilian public school teacher: domination and resistance in a neoliberal context

- Translanguaging and emotionality of English as a second language (ESL) teachers

- Emotion labor in response to supervisor feedback: is feedback a burden or a blessing?

- She is “just an intern”: transnational Chinese language teachers’ emotion labor with mentors in a teacher residency program

- Emotionally (in)hospitable spaces: reflecting on language teacher–teacher educator collaboration as a source of emotion labor and emotional capital

- Teaching English in an engineering international branch campus: a collaborative autoethnography of our emotion labor

- Commentary: exploring “the pinch” of emotion labor in language teacher research

- Advancing language teacher emotion research: a nuanced, dialectical, and empowering stance