Abstract

Reviewing is an act of power and not a mere act of applying shared academic standards of rigor. As such, it is inevitably implicated in the cultural politics of “naming”. In this paper we animate this taken-for-granted statement in the context of naming the sociopolitical struggles against dictatorial regimes in the Arab world. Since the end of 2010, the Arab world has witnessed a relatively organized series of protests and the peoples have named them “revolutions”. Western cultural political discourse has renamed these (trans)locally constituted struggles the “Arab Spring”. If we take sociolinguistics seriously as the “study of language in use”, we should consider the peoples in the Arab world as “subjects” of their own definitions, rather than as “objects” of Western constructions. We contend that reviewers, as gatekeepers, are implicated in the politics of voice when they uncritically accept the use of Western inventions as the “only” appropriate way of naming the world, and in so doing they effectively subvert the revolutionary interests in the Arab world.

Abstract

التحكيم العلميّ هو فعل سلطة، وليس مجرّد فعل لتطبيق معايير أكاديميّة مشتركة صارمة، وعليه فإنّه يدخل في السياسة الثقافية لتسمية وتصنيف العالم. تناقش هذه الورقة هذا المعطى، في سياق تسمية النضالات الاجتماعية والسياسية ضد الأنظمة الديكتاتورية في العالم العربي. فقد شهد العالم العربي منذ نهاية عام 2010 سلسلة من الاحتجاجات المُنظّمة نسبيًّا، والتي أطلقت عليها الشعوب اسم "ثورات". وقد سمّى الخطاب السياسيّ الثقافيّ الغربيّ هذه النضالات بـ"الربيع العربيّ". وإذا أخذنا اللسانيّات الاجتماعية على محمل الجدّ باعتبارها "دراسة الاستخدام الفعلي للغة"؛ يجب أن ننظر إلى الشعوب في العالم العربي على أنها "واضعة" (او فاعلة) لتعريفاتها الخاصّة بها، بدلًا من اعتبارها "موضوعًا" للتعريفات الغربيّة. وفي هذه الدراسة ندّعي أنّ المحكّمين العلميّين، بوصفهم حرّاسًا لبوّابة الحقل المعرفيّ؛ يسهمون في تشكيل "الصوت الاجتماعيّ" عندما يقبلون بصورة غير نقديّة المصطلحات الأوربّيّة؛ باعتبارها الطريقة المناسبة "الوحيدة" لتسمية العالم، وبذلك يقوّضون بشكل فادحٍ المصالح الثوريّة في العالم العربيّ.

Reviewing is an act of power and not a mere act of applying shared academic standards of rigor. As such, it has social and political ramifications, since it is implicated in the cultural politics of “naming”. In this paper we will animate this taken-for-granted formulation in the sociopolitical context of naming the struggles against dictatorial regimes in the Arab world. Since the end of 2010, the Arab world has witnessed a relatively organized series of struggles, including various forms of resistance, strikes, protests, street-sustained demonstrations, and sit-ins, with the goal of achieving social justice, equality, and freedom. The masses in these dynamic conditions of the Arab world have named their struggles “revolutions”. Western cultural political discourse lumps together these (trans)locally constituted struggles under the generalizing label of the “Arab Spring”. Thus, the peoples in the Arab world are effectively denied the agency to “name” their struggle simply because, among other things, their struggles do not fit the Western template for understanding socio-political revolutions. Their agentic definitions are “erased” through the cultural political process of (re)translation in Western discourse.

We contend that reviewers, as ideological gatekeepers, are implicated in the cultural politics of voice when they uncritically accept the use of Eurocentric discursive inventions as the “only” appropriate way of naming the world, and in so doing they effectively subvert the revolutionary interests in the Arab world.

We understand the politics of naming as a political discursive construction about the Other, strongly embedded in colonial and colonizing practices. Such a politics works as a form of norming (Berg and Kearns 1996), understood as a discursive apparatus (Foucault 1981) that provides a sense of normality and legitimacy to the naming practices of those who dominate the cultural politics of representation. The focus here is on the conflict over meanings and voice (subjectivity) in specific historical circumstances (Jordan and Weedon 1995). We argue that reviewing integrates such academic politics of representation that helps to normalize certain naming practices in detriment to others. One of the goals of revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces is to get access to social institutions and to impose their patterns of speaking, thinking, and acting on the world, i.e., to name the world. This observation obtains not only in the case of everyday linguistic usage but also in specialized fields such as sociolinguistics. Thus, our engagement itself should be seen as an exercise in cultural politics in the sense that it is objectively grounded in discursive analysis. But this form of “objectivity” does not mean “neutrality” in the representationalist conception of the term. It means we need to ground our arguments in descriptions of concrete semiotic structures of texts. This is what we will do in the remaining part of this paper. We will ground our inspection of the cultural politics of naming the struggles in the Arab world in “real-life” data. For limitations of space, we will focus on the context of Sudan, Egypt, and Tunisia.

We start with the cultural politics of “naming” the complex of forms of peaceful resistance to the regime of al-Bashir in Sudan, which started on December 19, 2018. Let us briefly inspect the most official piece of legal written discourse, which is the Constitutional Charter signed on August 4, 2019, to explore how it lexico-grammatically indexes the wider cultural and political world. The following quote is from the preamble:

Drawing inspiration from the Sudanese people’s struggles over the course of history and the years of the former dictatorial regime from the time that it undermined the constitutional regime on 30 June 1989; Believing in the principles of the glorious December 2018 Revolution; In fulfillment of the lives of the martyrs and affirming the rights of the victims of the policies of the former regime; Affirming the role of women and their active participation in carrying out the revolution; Recognizing the role of young people in leading the revolutionary movement; […] And based on the legitimacy of the revolution; We, the Transitional Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change, have agreed to issue the following Constitutional Charter. (Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period: 1; emphasis is ours)[1]

The first remark here is that the signatories of the Charter have represented the dynamics as “the December 2018 Revolution” or “the Revolution”. Secondly, the text refers to two forms of political organization of social life: “the former dictatorial regime” (i.e., al-Bashir’s regime) and “the constitutional regime” (i.e., the democratic system 1986–1989). As also indicated in the text, the relationship between these two sociopolitical structures is one of power and domination: the dictatorial regime of al-Bashir “undermined” the constitutional democratic system when it overturned the democratically elected government on June 30, 1989. Most importantly, the December Revolution is not imagined as a free-standing “event” with no grounds in history but rather as part of a long historical struggle including the struggle against al-Bashir’s regime. In other words, the struggle is defined as a historical process, and thus the December Revolution should be conceptualized as a moment or a wave in this long trajectory. More significantly, this constitutionalized usage of the term “revolution” “entextualizes” (Silverstein and Urban 1996) the way it is already used in grassroots and other non-official discourses of resistance to al-Bashir’s regime (see Figure 1).

This sign shows graffiti with the word “Revolution” as a description of the protests against dictatorship in Sudan.

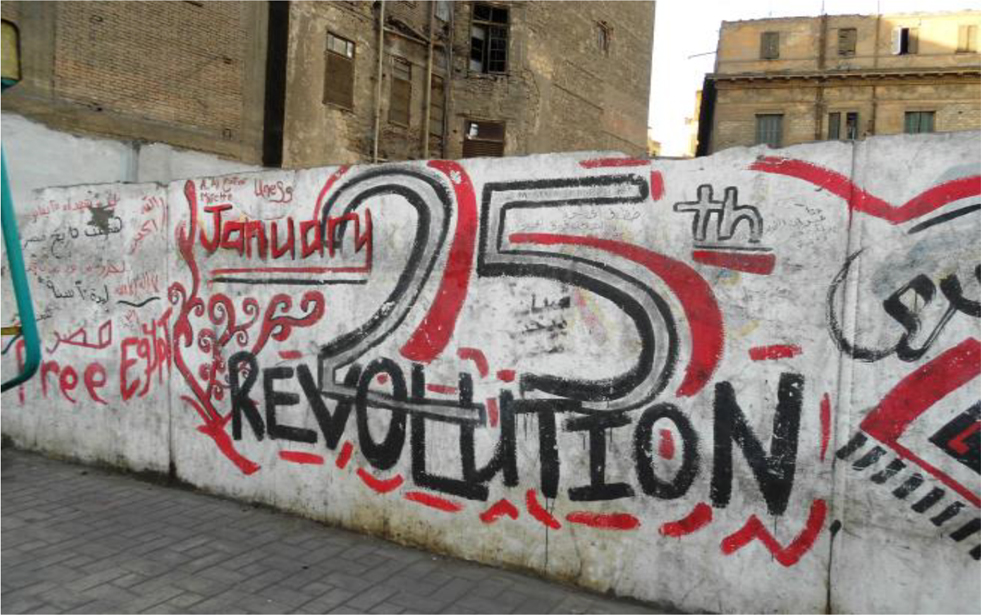

We mentioned previously that since the end of 2010 the Arab world has seen a number of protests and in some cases (e.g., Syria) armed resistance. We should note here that the forms of struggle in almost all the cases carried the name “revolution”. For example, the protests in Tunisia and Egypt are called the “Tunisian Revolution/Jasmine Revolution” (started in December 2010) and the “Egyptian Revolution of 2011/25 January Revolution” respectively (see Figures 2 –5).

A wall sign displaying the image of Mohamed Bouazizi with an Arabic text. Bouazizi was a Tunisian street vendor who set himself on fire on December 17, 2010. This act became a catalyst for revolts not just against the Tunisian autocratic regime but also against most of the dictatorships in the Arab world. Translation of the Arabic texts: “The Revolution of 17 December is the symbol of national unity”.

A Tunisian man reading graffiti. Translation of the Arabic text: “The Revolution of 17 December will never die”.

This graffiti in Egypt states in Arabic, among other things, that “the 25 January is a real Egyptian revolution”.

This graffiti articulates the name of the Egyptian protests against former President Mubarak as the “25 January Revolution”.

So, the national context and discursive construction of the struggle in Sudan is intertextual with the popular struggles in the region against dictatorships. They are all predominantly protests for social justice (the term “justice” features in all protesting discourses). However, the mainstream Western political discourse regularly lumps together the (trans)locally constructed forms of struggle with the term “Arab Spring” and retranslated the later anti-government protests in the region (December 2018–2020) including Sudan as “Arab Spring 2.0” (or New Arab Spring).[2] The term “Arab Spring” is not common in the cultural vocabulary of protests in these countries. Primarily on an ethnographic-sociolinguistic ground, we entirely agree with Khouri (2011) in rejecting this Western conceptualization of the struggles in those countries:

The most important reason for this is that this term is not used by those brave men and women who have been on the streets demonstrating and dying for the past seven months. Every time I run into a Tunisian, Egyptian, Libyan, Syrian, Bahraini or Yemeni, I ask them how they refer to their own political actions. Their answer is almost universal: “revolution” (thawra, in Arabic). And when they refer to the collective activities of Arabs across the region, they often use the plural, “revolutions” (thawrat) (Khouri 2011; emphasis in original)

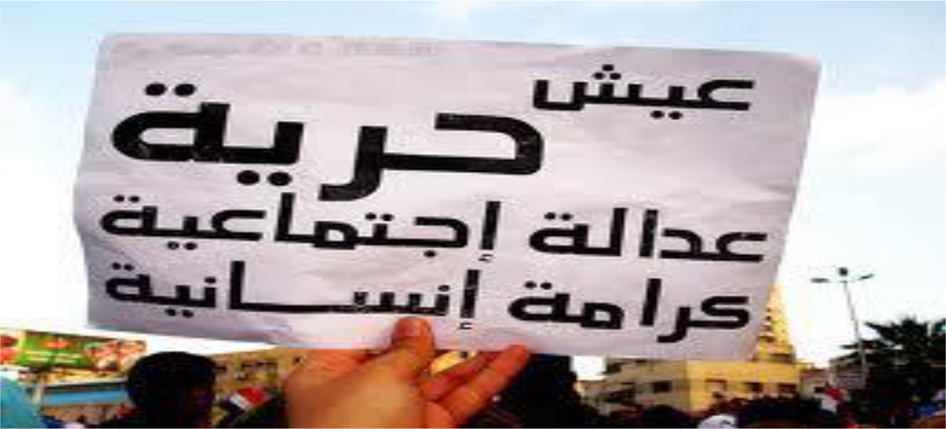

The term “Arab Spring” implies, among other things, that the protesting movements marked a sudden awakening from a long winter slumber, and that they would soon run out of steam and finish (Alhassen 2012). Thus, the Western (mediated) naming practice stripped the struggles in the Arab world of their history. The peoples’ symbolically constructed points of view of the struggle, which is something a sociolinguist should be aiming to capture, is systematically suppressed (on this methodological issue see Geertz 1974). They are all viewed as revolutions of Karama ‘dignity’ (ثورات الكرامة). And the word Karama is part of the repertoire of the slogans of these revolutions (see Figures 6 and 7). These values (dignity, freedom, justice) and the discourses in which they are formulated are a constituent part of the cultural politics of “voice”. This should not imply that the issue of economic distribution is not among the demands. It is among the demands, but the revolutions cannot be reduced to the “bread” only (cf. the Egyptian revolutionary slogan: “bread, freedom, social justice/human dignity”, see Figure 6). And this is precisely what the Western construction of the “Arab Spring” failed to recognize. Alhassen (2012) cogently argued:

The irony of the Western invention of the “Arab Spring” is that regardless of citizenry remonstrations for “self-determination”, we still continue to see the Arab region in our eyes and not through theirs. What is going on in the MENA [Middle East and North Africa] is something deeper than a democratic transformation, it is what democracy is predicated on – a demand for recognizing the right to human dignity. What is revolutionary about the revolutions sweeping the Middle East and North Africa is not the call to overthrow dictators, or even the inspiration that [the] Arab world has played in the global staging of governmental greed grievances from European anti-austerity measures protests to the Occupy movement that started in the States. What has been revolutionary is the call to establish a new way of envisioning human treatment, through a demand for dignity.

A mobile sign in Arabic displaying the slogan of the Egyptian Revolution. English translation: “Bread, Freedom, Social Justice, Human Dignity”.

This mobile sign documents a street protest in the context of the Marches of Bread and Dignity, which took place on April 4, 2019, in Sudan.

The undifferentiating conception of “Arab Spring” erases the historical specificity of these revolutions. For instance, al-Bashir’s regime is basically a military dictatorial system of Sudanese Muslim Brothers, while in other contexts the Muslim Brothers, as a political party or organization, was a force in the struggles for democracy. Unlike the other revolutions in the region, peace was a fundamental demand in the Sudanese revolution, since the former regime was implicated in genocidal wars in Darfur.

In conclusion, we contend that if we take the definition of sociolinguistics seriously as the “study of language in use”, then we should reframe the subordinated in the Global South as “subjects” of their own definitions formulated from within their own cultural political discourses, rather than as “objects” of Western definitions (Pennycook and Makoni 2020; Piller 2016; Santos and Meneses 2009; Suleiman 2013). Most of the non-Western naming practices are performed in languages other than English, although local publicity is quite often conducted bilingually in English or French to internationalize the cause, but from within their own politics of representation (e.g., Figures 1, 3, and 5). Their “voice”, however, is unheard. It gets “devoiced” as an effect of being retranslated in a different cultural discourse. The majority of languages (e.g., Arabic) have rarely been validated as media of knowledge production on these issues. The International Journal of the Sociology of Language (IJSL) has widened the net of the recognized languages of academic publication in the journal; it is open to considering additional languages. This should be critically welcomed as the linguistic net remains predominantly European (English, French, Spanish, or German). However, the IJSL has tried to mitigate the effect of the hegemony of Eurocentric naming practice by reconfiguring the editorial board to incorporate more reviewers from the Global South. The effect of English monolingualism, which has largely shaped the dominant reviewing practice, is that other non-Western epistemologies as ways of naming the world are systematically rendered invisible.

An Arabic version of this article can be found in the Appendix.

Acknowledgments

Open Access funding is provided by the Qatar National Library. We would like to thank the General Editor (Alexandre Duchêne) and the associate editors who read the earlier draft of this paper for their very useful comments. We also want to thank the publisher for the permission to publish an Arabic version of this article. We are also grateful to colleagues who have engaged with the Arabic version of the English text (see Appendix), and we particularly want to thank Albashir Mohamed, Mekki Elbadri, Ahmed Berair, and Mohammaed Ismail. The publication of this article was funded by the Qatar National Library.

التحكيم العلميّ "وصوت الشعب": الشعوب في العالم العربيّ تُسمّي نضالاتها "ثورات" وليس "الربيع العربي"

يعدّ التحكيم العلمي فعل سلطة وليس مجرّد فعل لتطبيق معايير أكاديميّة مشتركة صارمة. وبهذا المفهوم فإنّ للتحكيم العلميّ تداعيات اجتماعيّة وسياسيّة، إذ إنّه يدخل في السياسة الثقافيّة لتسمية ووصف العالم. تهدف هذه الورقة إلى الاشتباك مع هذه الحجّة المسلّم بها في السياق الاجتماعيّ والسياسيّ للعالم العربيّ؛ لتسمية النضالات ضد الأنظمة الديكتاتوريّة. منذ نهاية عام 2010 شهد العالم العربيّ سلسلة من النضالات المنظّمة نسبيًّا؛ وقد اتّخذت تلك النضالات أشكالًا مختلفة من أشكال المقاومة؛ كالإضرابات والاحتجاجات والتظاهرات المستمرة في الشوارع والاعتصامات، نشدانًا لتحقيق العدالة الاجتماعيّة والمساواة والحرّيّة. وفي ظلّ هذه الأجواء والظروف الديناميكيّة؛ أطلقت جماهير العالم العربيّ على نضالاتها اسم "ثورات". بينما أطلق الخطاب السياسيّ الثقافيّ الغربيّ على كلّ تلك النضالات -المشتركة نسبيًّا ولكنها تشكّلت محلّيًّا- اسم "الربيع العربيّ". وبهذا تكون الشعوب في العالم العربي قد حُرمت فعليًّا من حقّها في "تسمية" نضالاتها؛ ببساطة لأنّ تلك النضالات -بالإضافة إلى أسباب أخرى- لا تتناسب مع النموذج الغربيّ لفهم الثورات الاجتماعيّة والسياسيّة. فجرى "محو" التعريفات العربيّة للثورة وإعادة إنتاجها، من خلال الترجمة الثقافيّة الأوربيّة للخطاب العربيّ.

نحن نزعم أنّ المحكّم العلميّ؛ بوصفه حارسًا أيديولجيّا لبوّابة المعرفة العلميّة، يساهم في تشكيل الصوت الثقافيّ والسياسيّ للشعوب، وعندما يقبل بشكل غير نقديّ استخدام المفاهيم الخطابيّة الأوروبّيّة؛ باعتبارها الطريقة المناسبة "الوحيدة’’ لتسمية العالم، فإنّه بذلك يعمل من حيث يدري أو لا يدري على وأد المصالح الثوريّة في العالم العربيّ.

ولنا أن نفهم سياسة التسمية على أنّها بناء خطابيّ سياسيّ يتمّ إسقاطه على الآخر، وهو بذلك خطاب متجذّر في الأساليب الاستعماريّة والمُستعمِرة. تعمل مثل هذه السياسة كنظام معياريّ (Berg and Kearns 1996) ، أو جهاز خطابيّ (Foucault 1981) يجعل العالم يبدو "طبيعيًّا" من منظور الذين يسيطرون على موارد تسمية وتمثيل العالم. وينصبّ التركيز هنا على التسمية كساحة صراع حول المعاني والصوت الهوياتيّ في ظروف تاريخيّة محدّدة (Jordan and Weedon 1995). والحجّة هنا هي أنه من خلال استخدام منظومة تصوّرات محدّدة حول العالم؛ يعمل التحكيم العلميّ على تطبيع أو معيرة أساليب وطُرق تسمية معيّنة دون غيرها. لذلك فإنّ بعض أهداف القوى الثورية والقوى المضادّة للثورة تتمثّل في تشكيل المؤسّسات الاجتماعيّة؛ من خلال فرض أنماطها الخطابيّة والفكريّة عليها (أي تسمية الأشياء في العالم). وتنسحب هذه الملاحظة ليس فقط على مجالات اللغة العاديّة اليوميّة، بل أيضًا على المجالات المتخصّصة مثل اللسانيّات الاجتماعيّة. وبالتالي، يجب أن يُنظر إلى اشتباكنا مع الموضوع في حدّ ذاته على أنّه مران في السياسة الثقافيّة؛ بمعنى أنّه يركّز بشكل موضوعيّ على تحليل الخطاب من أرضيّة معرفيّة محدّدة. لكنّ "الموضوعيّة" لا تعني "الحياد" بالمفهوم الذي يجعل الواقع مستقلًّا عن اللغة، بل تعني أنّنا يجب أن نؤسّس حججنا على وصف البناء السيميائيّ للنصّ، وهذا ما سنقوم به في الجزء المتبقّي من هذه الورقة. سنبني محاولة استقصائنا للخطاب السياسيّ-الثقافيّ لتسمية الكفاح في العالم العربيّ على معطيات "الحياة الواقعيّة". ولمحدوديّة مساحة الورقة؛ سنركّز على سياق السودان ومصر وتونس.

نبدأ مع السياسة الثقافيّة لـ"تسمية" أشكال المقاومة السلميّة ضدّ نظام البشير في السودان، والتي بدأت في 19 ديسمبر 2018. ونقترب لنأخذ نظرة موجزة في الوثيقة الدستوريّة - باعتبارها النصّ القانونيّ الأكثر رسميّة - التي تمّ التوقيع عليها في 4 أغسطس 2019؛ لنستقصي الكيفيّة التي وُصف بها السياق الثقافيّ والسياسيّ العريض في تلك الوثيقة. الاقتباس التالي مأخوذ من المقدّمة:

استلهامًا لنضالات الشعب السوداني الممتدة عبر تاريخه، عبر سنوات النظام الديكتاتوري البائد منذ تقويضه للنظام الدستوري في الثلاثين من يونيو 1989م، وإيمانًا بمباديء ثورة ديسمبر 2018م المجيدة، ووفاءً لأرواح الشهداء وإقرارًا بحقوق كافة المتضررين من سياسات النظام السابق، وإقرارًا بدور المرأة ومشاركتها الفاعلة في إنجاز الثورة، اعترافًا بدور الشباب في قيادة الحراك الثوري … واستنادًا إلى شرعية الثورة، فقد توافقنا نحن المجلس العسكري الانتقالي وقوى إعلان الحرية والتغيير على أن تصدر الوثيقة الدستورية التالي نصها" (الوثيقة الدستورية 2019: 1)[3]

الملاحظة الأولى هنا هي أنّ المُوقعّين على الوثيقة الدستوريّة صوّروا السياق على أنّه "ثورة ديسمبر 2018" أو "الثورة". ثانيًا، يُشير نصّ الوثيقة الدستوريّة إلى شكلين من أشكال التنظيم السياسيّ للحياة الاجتماعيّة: "النظام الديكتاتوري السابق" (أي نظام البشير) و"النظام الدستوريّ" (أي النظام الديمقراطيّ 1986–1989). وكما هو مُبيّن في النصّ، فإنّ العلاقة بين هذين الهيكلين السوسيوسياسيّين هي علاقة سلطة وهيمنة: فالنظام الديكتاتوري للبشير "قوَّض" النظام الديمقراطيّ الدستوريّ عندما انقلب على الحكومة المنتخبة ديمقراطيًّا في 30 يونيو 1989. والأهمّ من ذلك، أنّ الوثيقة الدستوريّة لا تنظر إلى ثورة ديسمبر على أنّها "حدث" قائم بذاته لا أساس له في التاريخ، بل يُنظر إليها كجزء من مسار تاريخيّ طويل من النضال والكفاح ضدّ نظام البشير. بعبارة أخرى، يُعرّف النضال بأنه عمليّة تاريخيّة، وبالتالي يجب أن يُنظر إلى ثورة ديسمبر على أنها لحظة تاريخيّة أو موجة في هذا المسار الطويل. فضلًا على أنّ هذا الاستخدام المؤسّسيّ لمصطلح "ثورة" يعكس بصورة "تناصّيّة" (Silverstein and Urban 1996) الطريقة المستخدمة بالفعل في الخطابات الشعبيّة والخطابات غير الرسميّة الأخرى؛ المقاومة لنظام البشير (انظر الشكل 1).

1. أنظر الشكل

ذكرنا سابقا أنّه منذ نهاية عام 2010 شهد العالم العربيّ عددًا من الاحتجاجات السلميّة، والتي انزاح بعضها عن مسار السلميّة إلى مسار المقاومة المسلّحة (مثلما حدث في سوريا). وتجدر الإشارة هنا إلى أنّ أشكال النضال في جميع الحالات تقريبًا حملت اسم "الثورة". من ذلك أنّ الاحتجاجات في تونس حملت اسم "الثورة التونسية/ ثورة الياسمين" (بدأت في ديسمبر 2010) والاحتجاجات المصريّة حملت اسم "الثورة المصريّة/ ثورة 25 يناير" (أنظر الأشكال 2 و3 و4 و5).

2. أنظر الشكل

3. أنظر الشكل

4. أنظر الشكل

5. أنظر الشكل

نخلص من ذلك إلى أنّ السياق الوطنيّ والبناء الخطابيّ للنضال في السودان، يتقاطع او يتناصّ مع النضالات الشعبيّة في المنطقة ضد الديكتاتوريّات، حيث كانت كلّها احتجاجات من أجل العدالة الاجتماعيّة (يبْرُز مصطلح "العدالة" في جميع شعارات وخطابات الاحتجاجات). وعلى الرغم من ذلك، فإنّ الخطاب السياسيّ الغربيّ السائد؛ اختار أن يسمّي الموجة الأولى من الأشكال المحلّيّة (العابرة للحدود) من النضال في المنطقة بمصطلح "الربيع العربيّ"، وسمّى الاحتجاجات اللاحقة (من الفترة ديسمبر 2018–2020) المناهضة للحكومات مثل احتاجات السودان والجزائر بـ"الربيع العربيّ 2.0" (أو الربيع العربيّ الجديد).

إنّ مصطلح "الربيع العربيّ" ليس شائعًا في الخطاب الثقافيّ الشعبيّ للاحتجاجات في هذه البلدان. ومن منطلق سوسيو-لسانيّ إثنوغرافيّ نتّفق تمامًا مع خوري (2011) في رفض الوصف الغربيّ للنضالات في تلك البلدان:

السبب الأهم في ذلك هو أن هذا المصطلح لا يستخدمه الرجال والنساء الشجعان الذين كانوا يتظاهرون ويموتون في الشوارع خلال الأشهر السبعة الماضية. في كل مرة أقابل فيها تونسيا أو مصريا أو ليبيا أو سوريا أو بحرينيا أو يمنيا، أسألهم كيف يصفون أفعالهم السياسية. وتكون إجابتهم واحدة وعليها شبه إجماع: "ثورة". وعندما ينظرون إلى الأنشطة الجماعية للعرب في جميع أنحاء المنطقة العربية، فإنهم غالبًا ما يستخدمون صيغة الجمع "الثورات" (خوري 2011 ، التأكيد في الأصل)

يشير مصطلح "الربيع العربيّ" من بين أمور أخرى، إلى أنّ حركات الاحتجاج كانت بمثابة هبّة ويقظة مفاجئة من سبات شتويّ طويل، وأنّها سوف تتلاشى سريعًا وينطفي بريقها وتزول (الحسن 2012). وهكذا نجد أنّ نهج التسمية الغربيّ قد جرّد النضال في العالم العربيّ من تاريخه. وبالتالي تمّ قمع رؤية ووصف هذه الشعوب لكفاحها؛ قمعًا مُمنهجًا، وهذا أمر ينبغي أن ينتبه إليه السوسيولسانيّ (حول هذه المسألة المنهجية، انظر Geertz 1974). يُنظر إلى كل الاحتجاجات على أنّها ثورات كرامة (ثورات الكرامة)، وكلمة الكرامة جزء من المخزون اللغويّ لشعارات هذه الثورات (انظر الشكلين 6 و 7). وتُعتبر هذه القيم (الكرامة، والحرّيّة، والعدالة) وأنواع الخطابات التي تُصاغ فيها، جزءًا أصيلًا من السياسة الثقافيّة لـ"الصوت" الاجتماعيّ لهذه الشعوب. وهذا لا ينبغي أن يعني أنّ قضيّة التوزيع العادل للموارد الاقتصاديّة ليست ضمن المطالب؛ بل هي ضمن المطالب، لكنّ الثورات لا يمكن اختزالها في "الخبز" فقط (راجع الشعار الثوري المصري: الخبز، والحرّيّة، والعدالة الاجتماعيّة/الكرامة الإنسانيّة، أنظر الشكل 6). وهذا بالضبط هو الأمر الذي فشل في تصويره وإدراكه المفهوم الغربيّ لمصطلح "الربيع العربي". وقد أشار الحسن (2012) الى هذه النقطة على نحو مقنع بقوله:

إن المفارقة في الاختراع الغربي لمصطلح "الربيع العربي" هي أنه بغض النظر عن المظاهرات الجماهيرية من أجل "تقرير المصير"، ما زلنا نرى المنطقة العربية بأعيننا وليس من خلال عيونهم. إن ما يحدث في منطقة الشرق الأوسط، وشمال إفريقيا هو شيء أعمق من تحول ديمقراطي، وهو ما تقوم عليه الديمقراطية - مطلب الاعتراف بالحق في الكرامة الإنسانية. إن الشيء الثوري في هذه الثورات التي تجتاح الشرق الأوسط، وشمال إفريقيا ليس الدعوة إلى الإطاحة بالديكتاتوريين، أو حتى الاحتجاجات في الأقليم ضد المظالم الناتجة عن الجشع العالمي للحكومات او تلك التي اندلعت ضد التقشف الأوربي أو مساهمة العالم العربي في حركة احتل التي بدأت في الولايات المتحدة. ما يعتبر ثوريًا هو الدعوة إلى بناء تصوّر جديد للمعاملة الإنسانية من خلال المطالبة بالكرامة.

6. أنظر الشكل

7. أنظر الشكل

إنّ المفهوم المجرّد غير المميّز لمصطلح "الربيع العربيّ" يمحو الخصوصيّة التاريخيّة لهذه الثورات، فعلى سبيل المثال؛ كان نظام البشير في الأساس نظامًا ديكتاتوريًّا عسكريًّا قاده الإخوان المسلمون في السودان، بينما في سياقات أخرى كان الإخوان المسلمون كحزب أو كحركة سياسيّة؛ قوّة في النضال من أجل الديمقراطيّة. وعلى عكس الثورات الأخرى في المنطقة، كان السلام مطلبًا أساسيًّا في الثورة السودانيّة، حيث تورّط النظام السابق في حروب الإبادة الجماعيّة في دارفور.

في الختام، نؤكّد أنّه إذا أخذنا تعريف اللسانيّات الاجتماعيّة على محمل الجدّ؛ على أنّه هو دراسة الاستخدام الفعليّ للّغة؛ يلزمنا إذن إعادة تأطير المهمشّين في الجنوب العالميّ كـ"واضعين" (أو منتجين) لتعريفاتهم الخاصة بهم، والتي تمّت صياغتها من داخل خطاباتهم السياسيّة الثقافيّة، بدلًا من اعتبارهم "موضوع" التعريفات الغربيّة (Pennycook and Makoni 2020; Piller 2016; Santos and Meneses 2009; Suleiman 2013). تصاغ معظم التسميات غير الغربيّة بلغات أخرى غير الإنجليزيّة، على الرغم من أنّ الترويج والإعلام المحليّ غالبًا ما يكون بلغتين، وإحداهما إمّا اللغة الإنجليزيّة أو الفرنسيّة؛ لتدويل القضيّة، ولكن من داخل خطاب التصورات المحلّيّة نفسه (على سبيل المثال، الأشكال 1 و 3 و 5). وعلى الرغم من ذلك يظلّ صوت تلك الشعوب غير مسموع؛ لأنّه يتمّ كبته من خلال إعادة كتابته بخطاب أوربّيّ مغاير، ونادرًا ما يتمّ اعتماد غالبيّة اللغات (مثل العربيّة) كوسيلة لإنتاج المعرفة حول هذه القضايا. قامت المجلّة الدوليّة لسوسيولوجيّة اللغة بتوسيع شبكة اللغات المُعترف بها للنشر الأكاديميّ، وهي بصدد إضافة لغات أخرى، ويجب أن نرحّب بهذا الأمر بشكل نقديّ؛ حيث تظلّ اللغات المختارة للنشر في الغالب أوروبّيّة (الإنجليزيّة أو الفرنسيّة أو الإسبانيّة أو الألمانيّة) ومع ذلك، فقد حاولت المجلّة التخفيف من تأثير هيمنة الخطاب الأوربّيّ في وصف وتسمية العالم، من خلال إعادة تشكيل هيئة التحرير؛ بإضافة عدد من المحكّمين الذي ينتمون إلى الجنوب العالميّ. أخيرًا نشير إلى أنّ الأحاديّة الإنجليزيّة التي شكّلت إلى حدّ كبير طبيعة التحكيم العلميّ في الغرب؛ باتت تؤثّر على المعارف غير الغربيّة، وبالتحديد معارف العالم العربيّ، من بين ذلك المعارف المستخدمة في وصف وتسمية العالم، بل وإنّها صارت تحجبها إلى أن أمست غير مرئيّة بشكل منهجيّ.

References

Alhassen, Maytha. 2012. Please reconsider the term ‘Arab Spring’. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/please-reconsider-arab-sp_b_1268971 (accessed 25 August 2010).Search in Google Scholar

Berg, Lawrence & Robin Kearns. 1996. Naming as norming: ‘race’, gender, and the identity politics of naming places in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14. 99–122.10.1068/d140099Search in Google Scholar

Foucault, Michel. 1981. The order of discourse. In Robert, Young (ed.), Untying the text: A post–structuralist reader, 48–78. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.10.5749/j.ctvn96fd9.9Search in Google Scholar

Geertz, Clifford. 1974. From the native’s point of view: On the nature of anthropological understanding. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 28(1). 26–45.10.2307/3822971Search in Google Scholar

Jordan, Glenn & Chris Weedon. 1995. Cultural politics: Class, gender, race and the postmodern world. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Khouri, Rami. 2011. Arab Spring or revolution. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/arab-spring-or-revolution/article626345/ (accessed 26 August 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair & Sinfree Makoni. 2020. Innovations and challenges to applied linguistics from the global south. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429489396Search in Google Scholar

Piller, Ingrid. 2016. Monolingual ways of seeing multilingualism. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 11(1). 25–33.10.1080/17447143.2015.1102921Search in Google Scholar

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa & Maria Paula Meneses (eds.). 2009. Epistemologias do Sul. Coimbra: Livraria Almedina.Search in Google Scholar

Silverstein, Michael & Greg Urban (eds.). 1996. Natural histories of discourse. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Suleiman, Yasir. 2013. Arabic folk linguistics: Between mother tongue and native language. In Jonathan Owens (ed.), The Oxford handbook of Arabic linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199764136.013.0011Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Ashraf Abdelhay et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Dedication: Ofelia García

- Welcome on board! Prefiguring knowledge production in the sociology of language

- Reviewing and the politics of voice: peoples in the Arab world “name” their struggles “revolutions” and not the “Arab Spring”

- Managing authorship in (socio)linguistic collaborations

- A gendered academy – women’s experiences from higher education in Cameroon

- Education, multilingualism and bilingualism in Botswana

- Digital conferencing in times of crisis

- Discourse analysis for social change: voice, agency and hope

- On the future of IJSL: trans-collaboration and how to overcome the structural constraints on knowledge production, distribution and dissemination

- Gaps in sociolinguistic research in sub-Saharan Africa

- Publishing policy: toward counterbalancing the inequalities in academia

- Language and globalization revisited: Life from the periphery in COVID-19

- Raciolinguistic genealogy as method in the sociology of language

- Genres in new economies of language

- Moments of crisis

- Redrawing the boundary of “speech community”: how and why the historicity and materiality of language and the space/place distinction matter to its reconceptualization

- The past is a future priority

- Discursive practices control in Spanish language

- Whose hearing matters? Context and regimes of perception in sociolinguistics

- Academic knowledge production and prefigurative politics

- Hegemonies and inequalities in academia

- Decolonising sociolinguistics research: methodological turn-around next?

- Desires for “committed” research

- For an international journal in transnational times

- Epistemicide, deficit language ideology, and (de)coloniality in language education policy

- Powered by assemblage: language for multiplicity

- Unequal discursivities and the symbolic capital of Malaysian Indian scholarship

- The politics of language scholarship: there are no truly global concerns

- Southernizing and decolonizing the Sociology of Language: African scholarship matters

- When language policy is not enough

- Rethinking agency in language and society

- Procesos y materialidad en el estudio del lenguaje en sociedad

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Dedication: Ofelia García

- Welcome on board! Prefiguring knowledge production in the sociology of language

- Reviewing and the politics of voice: peoples in the Arab world “name” their struggles “revolutions” and not the “Arab Spring”

- Managing authorship in (socio)linguistic collaborations

- A gendered academy – women’s experiences from higher education in Cameroon

- Education, multilingualism and bilingualism in Botswana

- Digital conferencing in times of crisis

- Discourse analysis for social change: voice, agency and hope

- On the future of IJSL: trans-collaboration and how to overcome the structural constraints on knowledge production, distribution and dissemination

- Gaps in sociolinguistic research in sub-Saharan Africa

- Publishing policy: toward counterbalancing the inequalities in academia

- Language and globalization revisited: Life from the periphery in COVID-19

- Raciolinguistic genealogy as method in the sociology of language

- Genres in new economies of language

- Moments of crisis

- Redrawing the boundary of “speech community”: how and why the historicity and materiality of language and the space/place distinction matter to its reconceptualization

- The past is a future priority

- Discursive practices control in Spanish language

- Whose hearing matters? Context and regimes of perception in sociolinguistics

- Academic knowledge production and prefigurative politics

- Hegemonies and inequalities in academia

- Decolonising sociolinguistics research: methodological turn-around next?

- Desires for “committed” research

- For an international journal in transnational times

- Epistemicide, deficit language ideology, and (de)coloniality in language education policy

- Powered by assemblage: language for multiplicity

- Unequal discursivities and the symbolic capital of Malaysian Indian scholarship

- The politics of language scholarship: there are no truly global concerns

- Southernizing and decolonizing the Sociology of Language: African scholarship matters

- When language policy is not enough

- Rethinking agency in language and society

- Procesos y materialidad en el estudio del lenguaje en sociedad