Abstract:

Fucoxanthin intake has been correlated with the functions of anti-obesity and anti-oxidation, but applications of it in functional food or dietary supplements are still challenging due to its poor water-solubility, chemical instability, and low bioavailability. In this work, to study physicochemical and biological properties of fucoxanthin nanoemulsions, we investigated the influence of emulsion particle diameter on the stability of fucoxanthin during storage time and bioaccessibility in-vitro digestion. The structured lipid that enriched pinolenic acid at sn-2 position was chosen as the oil phase and the fucoxanthin oil-in-water nanoemulsions with droplet diameters of 344, 173, and 98 nm were prepared through a high-pressure microfluidizer. Then fucoxanthin emulsions were stored for 28 days at 4, 37, and 55 °C. Results showed that the physical stabilities of droplets were decreased with increases in the initial size and storage temperature, while the change of fucoxanthin retention indicated that fucoxanthin chemical stability was improved with increasing emulsion particle size. The augmentation of lipolysis and the value of free fatty acids (FFA) released in vitro digestion proved that digestion stability of fucoxanthin emulsion reduced with decreasing initial particle diameter, which was probably attributed to the increased surface area interacting with pancreatic lipase with decreasing droplet size. In addition, the concentrations of fucoxanthin in micelle phase were appreciable increased as droplet size decreased. Therefore, the bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin was improved. These results may benefit the optimization of an emulsion-based delivery system for fucoxanthin in food applications.

1 Introduction

Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid, is characterized by its unique structure including an allenic bond, a conjugated carbonyl group, and 5, 6-monoepoxide [1, 2]. Fucoxanthin is abundant in macroalgae such as Eisenia bicyclis, Laminaria japonica, and Undaria pinnatifida as well as in microalgae such as Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Odontella aurita [2]. Many epidemiological studies reported that fucoxanthin exhibited anti-obesity effects by stimulating the expression of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 in white adipose tissue, and benefited consumers troubled by obesity and related disorders, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease [2–4]. Maeda et al. reported that fucoxanthin inhibited intercellular lipid accumulation during differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocyte cells [5]. Other activities including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and radical scavenging were also reported [5–14].

Although the many health benefit of fucoxanthin, its applications in functional food faces challenges due to its low water-solubility, high melting point, and poor chemical instability [15]. A number of studies revealed that the stability and bioaccessibility of such carotenoids can be improved when they are consumed with lipids [2, 15–18]. As the lipids were digested by gastric and pancreatic lipases, FFA released from lipids were incorporated along with bile acids and phospholipids into mixed micelles, which could solubilize and transport carotenoids to epithelium cells [19]. The bioaccessibility of carotenoids could therefore be improved by ingesting lipids with carotenoid-rich food [20].

Emulsion-based systems are particularly suited for encapsulating and delivering lipophilic components [21]. These systems are easily created by dissolving the lipophilic bioactive constituents within an oil phase and then mixing it with an aqueous phase containing a water-soluble emulsifier. Recently, great interests are given in the development of the emulsion-based systems, such as carotenoids emulsions [22–24]. Lee et al. [25] compared physicochemical stability, lipid oxidation, and lipase digestibility of protein-stabilized nanoemulsions with traditional emulsions. Acosta [26] suggested that the oral bioavailability of encapsulated lipophilic compounds was increased with the reduction of particle diameter in colloidal delivery systems to the nano-sized range. Other researchers investigated the influence of carrier oil on the stability and bioaccessibility of carotenoid-enriched emulsions [27, 28]. However, few reports on fucoxanthin emulsion focus on the influence of fucoxanthin stability and bioaccessibility.

Pine nut oil, the only commercial conifer nut oil, contains approximate 14 % of pinolenic acid (△5, 9, 12-C18:3) and has the beneficial effects of pinolenic acid in reducing body weight and lowering LDL-cholesterol [29–32]. Several studies also proved that a dietary combination of fucoxanthin with oil or fatty acids exhibited a synergistic effect on the prevention of obesity and diabetes in mice [33, 34]. However, in natural oils, pinolenic acid is mainly located at sn-1, 3 position (> 90 % of total pinolenic acid) of the triacylglycerol backbones, which may cause its relatively low bioavailability (by absorbing sn-2 positional fatty acids more efficiently than fatty acids located at sn-1 and sn-3 positions) [30].

Thus, an adequate understanding of the stability and bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin emulsions will contribute to their better use. In this study, the oil-in-water emulsions containing fucoxanthin with different particle size were prepared. The structured lipids containing pinolenic acid at sn-2 position from pine nut oil and linseed oil were used as the carrier oil phase. Subsequently, the mean particle diameter of droplet, fucoxanthin retention, and the value of FFA released, extent of lipolysis, the change of zeta potential, and the concentration of fucoxanthin in micelle phase in vitro digestion were investigated to determine the bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin emulsion in vitro digestion.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and reagents

Pine nut oil and linseed oil were purchased in a local market (Nanchang, China). Lipozyme TL IM from Thermomyces lanuginosus was obtained from Novozymes A/S (Bagsvaerd, Denmark). Fucoxanthin (with 99.3 % purity) was purchased from Beijing Sunky Biological Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Tween 80 was obtained from Aladdin Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Pepsin, bile extract and lipase (porcine pancreas) from porcine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All reagents and solvents were of analytical grade.

2.2 Enzymatic interesterification of structured lipids

Pine nut oil (60 g) and linseed oil (30 g) at a weight ratio of 2:1 were placed in a screw capped Erlenmeyer flask (500 mL). Immediately, the mixtures were reacted with Lipozyme TL IM (10 wt % of the total substrates) in a shaking water bath at 60 °C for 6 h. The mixing speed was set to 220 rpm. After the reaction, TL IM was removed from the mixtures by filtering, and FFA was titrated with 0.5 mol/L KOH solution in 95 % ethanol and washed out by water. The upper layer was passed through an anhydrous sodium sulfate column for removing moisture and solvent was fully evaporated under nitrogen to obtain the structured lipid.

2.3 Analysis of fatty acid composition

The structured lipid was methylated and analyzed the fatty acid composition by gas chromatography according to the procedures described by Zhu et al [35]. Briefly, structured lipid (20 mL) was saponified by 0.5 mol/L methanolic NaOH (1.5 mL) at 100 °C for 5 min and cooled, then methylated with 14 % of BF3 methanol solution (2 mL) at 100 °C for 3 min. The fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were extracted by 2 mL of isooctane. The extracts were analyzed by GC using an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector, an autoinjector, and a fused silica capillary column (CP-Sil 88, 100 m × 0.25 mm × 0.2 μm i.d.). The oven was heated to 45 °C and then held for 3 min, then increased to 175 °C at the rate of 13 °C/min and held for 27 min. This temperature was finally increased to 215 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min and then held for 35 min. The temperature of the injector and detector were set to 250 and 260 °C, respectively. Nitrogen was used as a carrier gas at a total flow rate of 52 mL/min in split mode (50:1). FAMEs were identified by comparison with the relative retention times of the corresponding standards. Analyses were performed in triplicate.

For determination of sn-2 positional distribution of fatty acids, partial hydrolysis with pancreatic lipase was adopted [36]. Ten milligrams of structured lipid was mixed with Tris-HCl buffer (1 mol/L, pH=7.6, 10 mL), 0.05 % of bile salt (2.5 mL), and 2.2 % of CaCl2 (1 mL), and 10 mg pancreatic lipase was subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 9 min and shaken at intervals. The hydrolytic product was extracted by diethyl ether and separated by TLC plate (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) where developing solvent was the mixture of diethyl ether/hexane/acetic acid (50:50:1 by volume). The band corresponding to the 2-monoacylglycerols (2-MAGs) was scrapped off, methylated, and analyzed by GC as described above. Analyses were performed in triplicate.

2.4 Fabrication of emulsions loaded with fucoxanthin

An oil phase was prepared by dissolving 0.02 % (w/w) of fucoxanthin in structured lipid with mild heating (<5 min at 50 °C), and then stirring at ambient temperature for about 1 h to ensure complete dissolution. An aqueous phase was prepared by dispersing 2 % (w/w) of Tween 80 in 10.0 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). A coarse oil-in-water emulsions (sample No. 1) were prepared by mixing oil phase (10 % w/w) and aqueous phase (90 % w/w) with a Ultra Turrax T 25 blender (IKA Labortechnik, Jahnke and Kunkel, Germany) at 7500 rpm for 4 min. Emulsion containing fine droplets were formed by passing the coarse emulsions through a high-pressure microfluidizer (Model 101, Microfluidics, Newton, MA) four times at different homogenization pressures: 30 MPa, 90 MPa and 150 MPa to produce samples with various droplet diameters, namely No. 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

2.5 Storage stability of fucoxanthin emulsions

The emulsion samples were transferred into screw-capped glass vials immediately after preparation. The three independent samples were stored in the dark for 4 weeks at 4, 37, and 55 °C, respectively. The aliquots were removed periodically for particle size and fucoxanthin content analysis. Fucoxanthin was extracted from emulsions and quantified by a UV-visible spectroscopy method. Extraction was performed by de-emulsifying 1 mL of sample in a 20 mL Pyrex glass tube with an extracting solvent of n-hexane: ethanol (1:1 by volume) and agitation on a vortex mixer for 30 s until aqueous phase and an organic phase were completely separated. The organic phase (yellow orange colored) containing fucoxanthin was removed, and the aqueous phase was then extracted twice until the color was disappeared. And then the mixed organic layer was measured at absorbance of 450 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Ultraspec 30ro, GE Health Sciences, USA), where structured lipid nanoemulsion without dispersing fucoxanthin was analyzed as a control and pure n-hexane and ethanol solution was used as a blank. The fucoxanthin content was determined using a standard curve created from solutions with varying amounts of known fucoxanthin. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

2.6 In vitro digestion

To simulate the bioaccessibility of ingested samples, the dynamic in vitro digestion model consisting of consecutive gastric and intestinal phases was used following a modified procedure of previous reports [37, 38]. The particle size and charge of the samples were measured after incubation in each stage.

Gastric phase: Simulated gastric fluid (SGF) was prepared by dissolving 2 g NaCl, 7 mL HCl, and 3.2 g pepsin (from porcine gastric mucosa) in a flask and then diluting with PBS (pH 7.0) to a volume of 1 L, and finally adjusting the pH to 1.2 using 1.0 mol/L of HCl. The 5 mL of sample was then mixed with SGF at a 1:3 mass ratio so that the final mixture contained 2.5 % (w/w) structured lipid. The mixture was then adjusted to pH 1.2 using 1.0 mol/L HCl and incubated with continuous stirring at 100 rpm in a temperature-controlled RCT basic magnetic stirrer (37 °C) with for up to 2 h.

Small intestine phase: After the gastric digestion step, the sample was immediately adjusted to pH 7.0 with 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution. The simulated small intestinal fluid (SSIF) contained 5 mL of pancreatic lipase (12 mg/mL), 4 mL of bile extract solution (48.5 mg/mL) and 1 mL of CaCl2 solution (750 mmol/L). The 4 mL of bile extract solution was first added to the 10 mL digesta with stirring and the resulting system was adjusted to pH 7.0. Then 1.0 mL of CaCl2 solution was added and the system was adjusted to pH 7.0. Finally, 5 mL of freshly prepared pancreatic suspension (pH 7.0, PBS) was added to the mixture. During 2 h of the intestinal digestion process, the pH of the solution was maintained at 7.0 by adding 0.2 mol/L of NaOH manually. The amount of NaOH added over time was recorded throughout the digestion. The temperature was kept at 37 °C with a thermostatic water bath and stirred at 100 rpm.

During the digestion process it was assumed that one molecule of structured lipid released two fatty acid molecules by consuming two molecules of NaOH. Therefore, the percentage of FFA released from the system and the extent lipolysis was calculated using eq. (1) [28]:

where VNaOH (t) is the volume of NaOH titrated into the reaction vessel to neutralize the FFAs released at the digestion time t (L). The amount of NaOH used for mock lipolysis (with no lipid added) was subtracted. CNaOH is the concentration of NaOH in the titration buret (mol/L). The mSL is the total mass of structured lipid present in the sample during digestion (g), MSL is the average molecular weight of the lipid (g/mol). The average molecular weights of the structured lipid were taken to be 880 g/mol. The FFA liberated from the samples were determined by subtracting the FFA concentration measured in the samples before digestion from that measured after digestion.

2.7 Particle size and ζ-Potential measurement

The average particle size and polydispersity index of diluted emulsions were measured by a dynamic light scattering Zetasizer (Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Worcester, UK) equipped with a He–Ne laser operating at a wavelength of 633 nm [39]. Samples were diluted (1:100) with the PBS (10 mM, pH 7.0) prior to analysis in order to avoid multiple scattering phenomena due to droplets interaction. Measurements of the average size of droplets were performed at 25 °C with an angle detection of 90° in polystyrene cuvettes (DTS0012; Malvern Instruments). The electrical charge (ζ- potential) was measured with laser Doppler electrophoretic mobility (Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Worcester, UK). Samples were diluted (1:100) with buffer solution and then placed in a capillary test tube (DTS1060, Malvern Instruments) that was loaded into the instrument. Samples were equilibrated for 1min at 25 °C inside the instrument before data were collected over at least 10 sequential readings and processed using the Smoluchowski model. All tests were done in triplicate.

2.8 Optical microscopy measurement

The microstructures of selected emulsions were observed using an optical microscope (Olympus CX31, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). A drop of emulsion was placed onto a microscope slide, and covered by a coverslip. An image of the sample was captured using digital image processing software and then stored.

2.9 Fucoxanthin bioaccessibility determination

The fucoxanthin bioaccessiblity was determined by the protocol described by Liang et al [28] with a slight modification. After in vitro digestion, 5 mL of the digesta was ultra-centrifuged at 4000 rpm at 25 °C for 40 min. The middle aqueous phase was collected with a syringe filter (0.45 μm, Millipore, Bedford, MA) and vortexed with 5 mL chloroform. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm at 25 °C for 10 min. The bottom chloroform phase was collected in which the fucoxanthin was solubilized. While the top layer was mixed with additional 5 mL of chloroform and then centrifuged as was mentioned above. The bottom phase was mixed with the previous one and transferred to a cuvette and analyzed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer at 450 nm. A cuvette containing pure chloroform was used as a reference cell. A standard curve of absorbance versus fucoxanthin was created by dispersing different fucoxanthin in chloroform and absorbance. Bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin was counted according to the following (2):

where CMicelle and Cfucoxanthinin emulsion are the concentration of fucoxanthin in the micelle phase and preliminary emulsion, respectively.

2.10 Statistical analysis

All experiments were assayed in triplicate, and results were expressed as the mean and the standard deviation. A statistical analysis software program (JMP 8, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform the analysis of variance. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Duncan’s multiple range test was performed to determine significance of difference at p < 0.05.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Fatty acid composition analysis

The total sn-2 positional fatty acid compositions (area %) of pine nut oil, linseed oil, and the structured lipid are presented in Table 1. Pine nut oil contained a high level of unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs, 91.07 %), in which major fatty acids were linoleic (45.31 %) or oleic acids (23.55 %). In addition, 15.97 % of pinolenic acid (△5, 9, 12-18:3) was detected in pine nut oil, but only 1.85 % was observed at sn-2 position. Thus, most pinolenic acid in pine nut oil is distributed at sn-1,3 positions of TAG molecule, which is fully consistent with previous study [29]. Interestingly, the content of pinolenic acid at sn-2 position increased significantly to 7.84 % after interesterification using lipase as a biocatalyst. Meanwhile, △5-UPIFAs content was increased from 2.85 % in pine nut oil to 9.8 % in structured lipid. The increase of functional pinolenic acid at sn-2 position is ideal and may enhance bioavailability since sn-2 positional fatty acid is absorbed more readily in the body. The alteration of the sn-2 positional fatty acid can be explained by the principle of acyl migration, which occurred during the lipase-catalyzed interesterification. Although acyl migration is considered a side reaction, it is valuable for our purposes as it deliberately enhances the proportion of pinolenic acid at sn-2 position.

the total and positional fatty acid compositions (area %) of pine nut oil, linseed oil, and structured lipid.

| Fatty acid | Pine nut oil | Linseed oil | Structured lipid | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAG | Sn-2 | TAG | Sn-2 | TAG | Sn-2 | |

| 14:0 | ND | ND | 0.10±0.01b | 0.05±0.02a | 0.04±0.00a | ND |

| 16:0 | 4.75±0.16c | 1.41±0.02a | 5.84±0.08d | 1.63±0.11a | 5.73±0.04d | 2.82±0.13b |

| 18:0 | 3.23±0.09d | 0.29±0.01a | 3.78±0.19e | 0.90±0.00b | 3.50±0.17d,e | 2.06±0.05c |

| △9-18:1 | 23.55±0.31b,c | 29.84±1.08e | 18.20±0.01a | 25.91±1.44d | 21.52±0.84b | 24.64±0.05c,d |

| △11-18:1 | 0.63±0.00b,c | 0.39±0.11a | 0.74±0.00c | 0.50±0.05a,b | 0.59±0.00b | 0.43±0.01a |

| △5,9-18:2 | 2.19±0.06d | 0.76±0.07a | ND | ND | 1.59±0.04c | 1.77±0.00b |

| △9,12-18:2 | 45.31±1.60d | 64.78±0.91e | 16.93±0.08a | 25.21±0.97b | 35.44±0.90c | 43.20±0.01d |

| 20:0 | 0.95±0.02d | ND | 0.10±0.00a | ND | 0.59±0.01c | 0.32±0.01b |

| △5,9,12-18:3 | 15.97±0.09d | 1.85±0.07a | ND | ND | 11.64±0.12c | 7.84±0.30b |

| △9,12,15-18:3 | ND | ND | 54.31±0.02c | 45.80±1.05b | 17.54±0.01a | 15.86±0.03a |

| △11-20:1 | 1.77±0.06c | 0.25±0.00a | ND | ND | 0.81±0.02b | 0.75±0.04b |

| △11,14-20:2 | 0.52±0.03d | 0.19±0.01b | ND | ND | 0.37±0.00c | 0.12±0.00a |

| △5,11,14-20:3 | 1.13±0.05c | 0.24±0.03a | ND | ND | 0.64±0.02b | 0.19±0.04a |

| ∑△5-UPIFAs | 19.27±0.2d | 2.85±0.09a | ND | ND | 13.87±0.07c | 9.80±0.24b |

| ∑USFAs | 91.07±0.27b | 98.30±0.03e | 90.18±0.13a | 97.42±0.10d | 90.14±0.11a | 94.80±0.19c |

| ∑SFAs | 8.93±0.20d | 1.70±0.07a | 9.82±0.13e | 2.58±0.10b | 9.86±0.11e | 5.20±0.19c |

All data are mean values ± standard deviations.

Structured lipid was produced by Lipozyme TL IM (lipozyme: substrate mixture, w/w, 1:10) with pine nut oil and linseed oil at a weight ratio of 2:1 at 60 °C for 6 h.

a-e Values with a different letter in the same row are significantly different (p < 0.05).

ND: not detected under this analysis condition; ∑△5-UPIFAs: total△5-unsaturated polymethylene interrupted fatty acids; ∑USFAs: total unsaturated fatty acids; ∑SFAs: total saturated fatty acids.

3.2 Physical stability of fucoxanthin nanoemulsions during storage

Fucoxanthin was successfully encapsulated in a 10 % structured lipid-based emulsion or nanoemulsion at a concentration of 0.02 % by weight, and homogenized at different pressures by the microfluidizer. We obtained a range of emulsions, labeled sample No. 1–4, with diameters of 3751, 344, 173, and 98 nm, respectively. The physical stabilities of the fucoxanthin-encapsulated emulsions were evaluated in terms of the evolution of their average particle sizes at different storage temperatures (4, 37, and 55 °C) for 4 weeks (Figure 1). Given the much larger particle diameter, emulsion No. 1 was observed to cream and layer separately after several hours of storage at room temperature. Hence, No. 1 was not considered in the evolution of particle change over time.

Evolution of the mean particle diameter of fucoxanthin encapsulated emulsions stored at 4 °C (a), 37 °C (b), and 55 °C(c) for 4 weeks. The particle diameters of samples No. 2–4 are 342, 175, and 98 nm.

In general, when storage temperature was 4 °C, the emulsions were relatively stable, with little change in mean particle diameters (Figure 1(a)). This result indicates that they were fairly resistant to droplet growth and gravitational separation. As storage temperature gave rise to 37 °C, slight increases of mean particle diameters (85, 42, and 27 nm) were observed for preparation No. 2, 3, and 4, respectively, after 4 weeks of storage (Figure 1(b)). However, a significant change was observed that diameters were increased by 183, 169, and 94 nm at 55 °C after 4 weeks (Figure 1(c)). These findings suggested that the physical stabilities of droplet sizes were decreased with increasing initial size during storage at different temperatures, which was consistent with the report of Liang et al. [24]. These results also show that emulsions may become unstable for long-term storage at higher temperatures. This effect may be attributed to the chemical degradation of Tween 80. For example, hydrolysis occurred when stored at increased temperature for a prolonged period, and surface activity was lost [40]. Interestingly, no appreciable phase separation or creaming was observed for the three samples during the storage time under any condition.

3.3 Chemical stability of fucoxanthin during storage

Fucoxanthin is sensitive to environmental conditions and tends to fade when undergoing chemical degradation. Fucoxanthin was thus monitored over a 4-week storage period under three different conditions to investigate the effect of temperature on the chemical stabilities of fucoxanthin emulsions. The concentrations were slightly different owing to the loss induced by homogenization. The initial fucoxanthin retained in the emulsions was 95 %, 92 %, 91 %, and 90 % for sample No. 1–4, respectively. The chemical degradation of fucoxanthin was represented by the amount of fucoxanthin retained compared with the original concentration.

As shown in Figure 2, the retention of fucoxanthin in samples at all temperatures decreased during storage. The retention of sample No. 1 (initial particle diameter of 3751 nm) fell from an initial value of 95 % to 90 %, 57 %, and 20 % after 1 week when stored at 4, 37, and 55 °C, respectively. When stored at 55 °C, emulsion No. 1 was completely lost by day 9 (Figure 2(c)). The higher loss observed in sample No. 1 may be attributed to creaming of the emulsion during storage.

Retention of fucoxanthin emulsions of different particle diameters during 30 days of storage with different storage temperature: 4 °C (a), 37 °C (b), and 55 °C (c).

For sample No. 2–4, fucoxanthin residue remained at 46 %, 32 %, and 23 %, respectively, at 37 °C, after 28 days, suggesting that chemical degradation increased with decreasing original mean particle size, as shown in Figure 2(b). Similar trends were observed for the emulsions at both 4 and 55 °C (Figure 2(a), Figure 2(c)). These results agreed with previous research by Lethuaut et al [41], who similarly observed that the oxidation degradation of sunflower oil emulsions increased as particle size decreased. These can be attributed to a large interfacial surface of a small average diameter, which would increase degradation [42]. Therefore, the increase of mean diameters for emulsions may favor the chemical stability of fucoxanthin.

3.4 The digestion of fucoxanthin emulsions

The FFA released and extent of lipolysis during in vitro digestion were presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The FFA released-versus-digestion time profiles showed similar trends for four emulsions containing different droplet sizes. A rapid increase in FFA was found in the first 20 min, followed by a more gradual increase with prolonged digestion time, until a relatively constant final value was reached and the final percentages of released FFA after 2 h of incubation were 53.4 %, 72.7 %, 82.1 %, and 85.9 %, respectively. Meanwhile, obvious differences between FFA released and extent of lipolysis depending on droplet diameters were observed, and the conventional emulsion (sample No. 1) was much lower than those of nanoemulsions. Thus, the rate of digestion of structured lipids was more rapid as the initial particle decreases. Other researchers have also reported that FFA release increased as droplet diameter decreased [25, 43]. This finding is attributed to changes in the surface area of oil exposed to pancreatic enzymes. For nanoemulsions, the particle size was relatively small, and oils had a large surface area, which benefited the interaction with lipase and then induced the rapid release of FFA [44]. By contrast, common emulsions with large droplets have insufficient surface area for interaction between the enzyme and structured lipid, thus delaying the reaction and decrease of FFA release from the latter.

Free fatty acids released profiles from fucoxanthin emulsions of different particle diameters during small intestine digestion by pancreatin as a function of time. The FFA was determined by the amount of NaOH added over time.

Effect of droplet diameter on the extent of lipolysis of 10 % structured lipid fucoxanthin emulsions after digestion 2 h in simulated small intestine. Different letters mean significant differences (p < 0.05) on the digestibility of fucoxanthin emulsions with different droplet diameters.

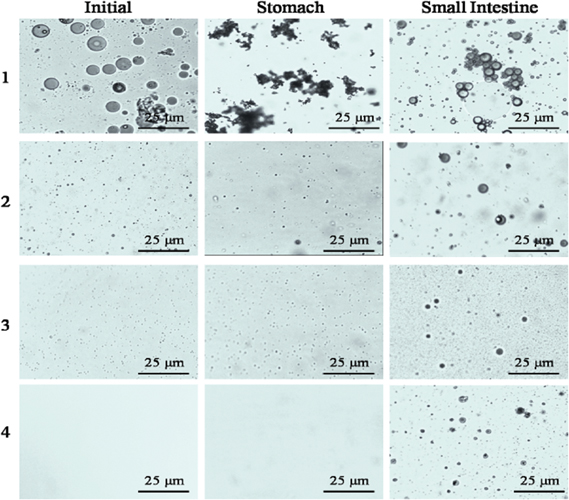

3.5 Behavior of droplet size, microstructure and electrical characteristics during digestion

The digestion stability of enriched emulsions was evaluated by analyzing the mean droplet diameters and electrical characteristics (ζ-potential) following the digestion process (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The microscopic images (Figure 7) provided a more intuitional insight for the particle diameter change using optical microscope. The images show that the emulsions of No. 2–4 contained much smaller droplets than No. 1.

Influence of different particle diameter (No. 1–4) on the fucoxanthin emulsions digestion at simulated gastrointestinal conditions. The a’ and b’ mean significant differences (p < 0.05) on the droplet diameter of an emulsion between different digestion phase. a-c values mean significant differences (p < 0.05) of an droplet diameter between emulsions with different size (No. 1–4) within the same digestion phase.

Influence of different particle diameter (No. 1–4) on charge (ζ-potential) of fucoxanthin emulsions at simulated gastrointestinal conditions. a’-d’ values mean significant differences (p < 0.05) on the droplet charge of an emulsion between different digestion phase. a-c values mean significant differences (p < 0.05) of an droplet charge between emulsions with different size (No. 1–4) within the same digestion phase.

Influence of droplet size on the microstructure of emulsions measured by optical microscopy at various stages in an in vitro gastrointestinal tract model. The initial particle diameters of preparations No. 1–4 are 3751, 344,173 and 98 nm, respectively.

The diameter of sample No. 1 showed an appreciable increase in mean particle size after incubation in the stomach, followed by a large decrease upon passing through the small intestine fluid for 2 h. The optical microscope images further show that the droplets size decreased subsequently after incubation in small intestine due to that lipids were digested into smaller droplets in the presence of bile salts, lipases, and prolonged mechanical agitation. The mean particle diameters of sample No. 2–4 showed no significant differences in simulated stomach fluids, revealing the superior stabilities of fucoxanthin emulsions in gastric fluids. This finding is possibly due to the emulsions having been prepared with Tween 80, a non-ionic surfactant, which is a highly surface-active molecule with a large hydrophilic head group. Therefore, the relatively strong steric repulsion was provided by polyoxyethylene head groups [45]. Nik et al. [46] also proved that lipid droplets encapsulated by non-ionic surfactants are relatively stable in gastric fluids. However, the appreciable increase in average particle size of the fucoxanthin emulsions (sample nos. 2-4) after incubation in simulated small intestinal fluid suggested that the droplets were highly susceptible to coalescence under the simulated intestinal digestion conditions. The growth of the particle was also observed in the microstructure, as shown in Figure 8. Several physicochemical characteristics may contribute to the presence of large particles. Firstly, as the pancreatic lipases adsorbed to the interface, structure lipids were converted to FFA and monoacylglycerols, which may also vary the composition and structure of the droplets and decrease their stability. Furthermore, digestion products may assemble into other colloidal structures, such as vesicles and fatty acid soaps, which interface with droplets. Secondly, published data has shown that long chain fatty acids released from lipolysis tend to remain at the droplet surface in the absence of bile salt or calcium, whereas short and medium chain fatty acids tend to move into aqueous phase [37, 44]. The lipolytic product of structured lipid mainly contained oleic, linoleic, linoleic, and pinolenic acids, which remained at the droplet surface. These are combined with other surface active substances (i. e., phospholipids and bile salts), which are adsorbed to the droplet, even replacing Tween 80, which alters the composition, structure, and properties of the interfacial layer and increases particle size.

Bioaccessibility (%) of fucoxanthin measured after centrifugation of emulsions with different particle diameters passed through an in vitro digestion model. Different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

However, the electrical change of the droplets exhibited fairly similar trends after passing through the gastric and small intestine regions. Interestingly, no appreciable difference was observed in the electrical charge of droplets in initial emulsions with varying particle sizes (No. 1–4) or of samples that had passed through gastric fluids. The initial emulsions all had slightly negative charges, ranging between –7 and –14 mV, even though neutral lipid droplets were coated with a non-ionic emulsifier (Tween 80). Therefore, anionic groups may be present in the surfactant or lipid phase capable of adsorbing to the interface and contributing a negative charge to the droplets, including FFA and phospholipids. The existence of hydrophilic head groups capable of creating H bonds with the OH− cannot be neglected in explaining the more negative charge under neutral conditions [47]. Similar negative potential in polysorbate-stabilized emulsions has been observed in other studies [48, 49]. As the emulsion environment became more acidic, the charge considerably decreased due to the decrease of the hydroxyl ion groups in the entire sample, thereby decreasing the amount of negatively charged group adsorbed to the oil–water interface. After incubation in simulated small intestine fluids, the magnitude of the negative charge of the particles increased appreciably. A vast increase of surface active anionic species was observed. The high negative charge may be attributed to the presence of numerous anionic species from the simulated gastrointestinal model, including bile salts and phospholipids, which may displace the original surfactant molecules and alter their surface charge. FFA and monoglyceride, which are hydrolytic products of structured lipid by pancreatic lipase, might also contribute to the increase of electrical potential [23]. In addition, the negative charge exhibited tremendous variance among different samples (No. 1–4), from –32 mV for sample No. 1 to –45 mV for sample No. 4, and the negative charge remaining on the particle surface increased as initial particle diameters decreased in the small intestinal stage. This finding may be attributed to the less complete release of FFA generated by the triglyceride with increasing droplet size for the added equal amount of lipase and bile salts. Consequently, more anionic groups may remain in the particle surface of the emulsion containing small particles than in the emulsion containing large particles.

Particle diameter and electrical characteristics are often used to reflect the structural property most related to the physicochemical stability of a colloidal system. We also found that this changes also coincided with the release of FFA and extent of lipid digestion. The extent of change (or digestion rate) of the four samples were in the order of No. 4 > No. 3 > No. 2 > No. 1, which was the reverse order of the initial diameter. These phenomena gave two clues: lipolysis was faster and more complete with a reducing initial droplet; lipid digestion in the body was an interfacial behavior; and more dramatic changes of interfacial properties indicated a higher lipid hydrolysis rate.

3.6 Bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin during in vitro digestion

The bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin was calculated as the fraction of fucoxanthin in the micelle phase compared with the initial concentration. The conventional emulsion was only 16.7 %, while the nanoemulsion with small particles No. 2–4 increased to approximate 33.9 %, 44.3 %, and 46.7 %, respectively (Figure 8). This remarkable increase of bioaccessibility is attributed to the decreased surface access of lipase due to the lower surface area of the emulsion containing large particles. Carotenoids in oil droplets were dissolved in mixed micelles after digestion. They were formed into micelles with bile salts, lipolysis products, and calcium [50]. These results revealed the critical role of mixed micelles and extent of lipolysis in improving fucoxanthin solubility and absorption, as observed in other studies [46, 51, 52]. Wang et al. also observed that nanoemulsion may disperse in the micelle phase after centrifugation, and noted that various factors affect the overall bioaccessiblity of carotenoids [53, 54]. Therefore, the decrease of fucoxanthin bioaccessibility with increasing initial droplet size may be explained by the increased number of undigested structured lipids, which can retain the most fucoxanthin. Another possibility is that the less-mixed micelles present relatively larger droplet size to solubilize fucoxanthin. A linear relationship exists between fucoxanthin bioaccessibility and the percentage of FFA released from the emulsions (Figure 9), indicating that fucoxanthin bioaccessibility might increase due to the increase of the amount of FFA. This suggested that the release of FFA could improve fucoxanthin bioaccessibility.

Relationship between the bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin and the amount of free fatty acids released after the in vitro digestion of emulsions with different droplet diameters.

4 Conclusions

In the present study, we showed that fucoxanthin, a bioactive carotenoid, could be successfully incorporated into food-grade nanoemulsions with the structured lipid enriched pinolenic acid at sn-2 position as the carrier oil phase. Our study focused on the assessment of the physicochemical stability and in vitro bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin-enriched emulsion or nanoemulsions. The fucoxanthin nanoemulsions were stable, and not coalesce within 4 weeks in storage at different temperatures. However, retention of fucoxanthin was lower for nanoemulsions with smaller droplet diameters.

In the simulated digestion model, little change of the average size and negative charge of droplets were found after passing through the gastric fluid. While the obvious enlargement of the size was observed after 2 h of incubation in simulated small intestine fluids, which is probably attributed to the presence of anionic bile salts, phospholipids, and FFA. Conversely, the emulsions containing large droplets were unstable to flocculate in the stomach stage, following a decrease in particles after passing the intestine. However, the rate and extent of structured lipid digestion strongly depended on initial droplet size, which increased as particle diameter decreased. This effect was attributed to the fact that the lipid digestion was an interfacial phenomenon, and a larger surface area for nanoemulsions would benefit lipase interacts with the structured lipid, increasing the rate of lipolysis and FFA. The bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin was positively correlated with the extent of lipolysis, and increased with the decrease of the initial droplet size due to the increase of released FFA from the emulsions. Meanwhile, more mixed micelles formed with FFA after digestion would increase the bioaccessibility of fucoxanthin due to the high dissolving capability of fucoxanthin in the gastrointestinal tract.

Funding statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31660470, 31460427, 31571870),Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (20142BAB205087) and the Research Program of Sate Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology in Nanchang University (Project SKLF-ZZB-201510) .

References

1. Gerhard E. 1D and 2D NMR Study of Some Allenic Carotenoids of the Fucoxanthin Series. Magn Reson Chem 1990;28:519–528.10.1002/mrc.1260280610Search in Google Scholar

2. Peng J, Yuan JP, Wu CF, Wang JH. Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid present in brown seaweeds and diatoms: Metabolism and bioactivities relevant to human health. Marine drugs 2011;9:1806–1828.10.3390/md9101806Search in Google Scholar

3. Maeda H, Hosokawa M, Sashima T, Miyashita K. Dietary combination of fucoxanthin and fish oil attenuates the weight gain of white adipose tissue and decreases blood glucose in obese/diabetic KK-Ay mice. J Agric Food Chem 2007;55:7701–7706.10.1021/jf071569nSearch in Google Scholar

4. Miyashita K, Nishikawa S, Beppu F, Tsukui T, Abea M, Hosokawa M. The allenic carotenoid fucoxanthin, a novel marine nutraceutical from brown seaweeds. J Sci Food Agric 2011;91:1166–1174.10.1002/jsfa.4353Search in Google Scholar

5. Maeda H, Hosokawa M, Sashima T, Takahashi N, Kawada T, Miyashita K. Fucoxanthin and its metabolite, fucoxanthinol, suppress adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. Int J Mol Med 2006;18:147–152.10.3892/ijmm.18.1.147Search in Google Scholar

6. Satomi Y, Tokuda H, Fujiki H, Shimizu N, Tanaka Y, Nishino H. Anti-tumor-promoting activity of fucoxanthin, anatural carotenoi. J Kyoto Pref Univ Med 1996;105:739–743.Search in Google Scholar

7. Kim JM, Araki S, Kim DJ, Park CB, Takasuka N, BabaToriyama H, et al. et al. Chemopreventive effects of carotenoids and curcumins on mouse colon carcinogenesis after 1,2-dimethylhydrazine initiation. Carcinogenesis 1998;19:81–85.10.1093/carcin/19.1.81Search in Google Scholar

8. Okuzumi J, Nishino H, Murakoshi M, Iwashima A, Tanaka Y, Yamane T, et al. et al. Inhibitory effects of fucoxanthin, a natural carotenoid, on N-myc expression and cell cycle progression in human malignant tumor cells. Cancer Lett 1990;55:75–81.10.1016/0304-3835(90)90068-9Search in Google Scholar

9. Hosokawa M, Wanezaki S, Miyauchi K, Kurihara H, Kohno H, Kawabata J, et al. et al. Apoptosis-inducing effect of fucoxanthin on human leukemia cell HL-60. Food Sci Technol Res 1999;5:243–246.10.3136/fstr.5.243Search in Google Scholar

10. Kotake-Nara E, Kushiro M, Zhang H, Sugawara T, Miyashita K, Nagao A. Carotenoids affect proliferation of human prostate cancer cells. J Nutr 2001;131:3303–3306.10.1093/jn/131.12.3303Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Hosokawa M, Kudo M, Maeda H, Kohno H, Tanaka T, Miyashita K. Fucoxanthin induces apoptosis and enhances the antiproliferative effect of the PPARgamma ligand, troglitazone, on colon cancer cells. Biochim Biophy Acta 2004;1675:113–119.10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.08.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Shiratori K, Ohgami K, Ilieva I, Jin XH, Koyama Y, Miyashita K, et al. et al. Effects of fucoxanthin on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Exp Eye Res 2005;81:422–428.10.1016/j.exer.2005.03.002Search in Google Scholar

13. Nomura T, Kikuchi M, Kubodera A, Kawakami Y. Protondonative antioxidant activity of fucoxanthin with 1,1-diphenyl- 2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). Biochem Mol Biol Int 1997;42:361–370.10.1080/15216549700202761Search in Google Scholar

14. Abdul QA, Choi RJ, Jungc HA, Choia JS. Health benefit of fucosterol from marine algae: A review. J Sci Food Agric 2016;96:1856–1866.10.1002/jsfa.7489Search in Google Scholar

15. Salvia-Trujillo L, Sun Q, Um BH, Park Y, McClements DJ. In vitro and in vivo study of fucoxanthin bioavailability from nanoemulsion-based delivery systems: Impact of lipid carrier type. J Funct Foods 2015;17:293–304.10.1016/j.jff.2015.05.035Search in Google Scholar

16. Borel P. Factors affecting intestinal absorption of highly lipophilic food microconstituents (fat-soluble vitamins, carotenoids and phytosterols). Clin Chem Lab Med 2003;41:979–994.10.1515/CCLM.2003.151Search in Google Scholar

17. Thakkar SK, Maziya-Dixon B, Dixon AGO, Failla ML. β-Carotene micellarization during in vitro digestion and uptake by Caco-2 cells is directly proportional to β-carotene content in different genotypes of cassava. J Nutr 2007;137:2229–2233.10.1093/jn/137.10.2229Search in Google Scholar

18. Van Het Hof KH, West CE, Weststrate JA, Hautvast JGAJ. Dietary factors that affect the bioavailability of carotenoids. J Nutr 2000;130:503–506.10.1093/jn/130.3.503Search in Google Scholar

19. Tyssandier V, Lyan B, Borel P. Main factors governing the transfer of carotenoids from emulsion lipid droplets to micelles. BBA-Mol Cell Biol L 2001;1533:285–292.10.1016/S1388-1981(01)00163-9Search in Google Scholar

20. Huo T, Ferruzzi MG, Schwartz SJ, Failla ML. Impact of fatty acyl composition and quantity of triglycerides on bioaccessibility of dietary carotenoids. J Agric Food Chem 2007;55:8950–8957.10.1021/jf071687aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Kaur K. Nanoemulsions as an effective medium for encapsulation and stabilization of cholesterol/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex. J Sci Food Agric 2015;95:2718–2728.10.1002/jsfa.7012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. McClements DJ, Decker EA, Park Y, Weiss J. Structural design principles for delivery of bioactive components in nutraceuticals and functional foods. Crit Rev Food Sci 2009;49:577–606.10.1080/10408390902841529Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Singh H, Ye A, Horne D. Structuring food emulsions in the gastrointestinal tract to modify lipid digestion. Prog Lipid Res 2009;48:92–100.10.1016/j.plipres.2008.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Liang R, Shoemaker CF, Yang X, Zhong F, Huang Q. Stability and bioaccessibility of β-carotene in nanoemulsions stabilized by modified starches. J Agric Food Chem 2013;61:1249–1257.10.1021/jf303967fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Lee SJ, Choi SJ, Li Y, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Protein-stabilized nanoemulsions and emulsions: Comparison of physicochemical stability, lipid oxidation, and lipase digestibility. J Agric Food Chem 2011;59:415–427.10.1021/jf103511vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Acosta E. Bioavailability of nanoparticles in nutrient and nutraceutical delivery. Curr Opin Colloid In 2009;14:3–15.10.1016/j.cocis.2008.01.002Search in Google Scholar

27. Wooster TJ, Golding M, Sanguansri P. Impact of oil type on nanoemulsion formation and Ostwald ripening stability. Langmuir 2008;24:12758–12765.10.1021/la801685vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Rao J, Decker EA, Xiao H, McClements DJ. Nutraceutical nanoemulsions: Influence of carrier oil composition (digestible versus indigestible oil) on β‐carotene bioavailability. J Sci Food Agric 2013;93:3175–3183.10.1002/jsfa.6215Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Destaillats F, Angers P, Wolff RL, Arul J. Regiospecific analysis of conifer seed triacylglycerols by gas-liquid chromatography with particular emphasis on Δ5-olefinic acids. Lipids 2001;36:1247–1254.10.1007/s11745-001-0839-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Zhu XM, Hu JN, Shin JA, Li D, Jin J, Adhikari P, et al. et al. Enrichment of pinolenic acid at the sn-2 position of triacylglycerol molecules through lipase-catalyzed reaction. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2010;61:138–148.10.3109/09637480903348106Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Ferramosca A, Savy V, Einerhand AWC, Zara V. Pinus koraiensis seed oil (PinnoThinTM) supplementation reduces body weight gain and lipid concentration in liver and plasma of mice. J Anim Feed Sci 2008;487:47.10.22358/jafs/66690/2008Search in Google Scholar

32. Lee JW, Lee KW, Lee SW, Kim IH, Rhee C. Selective increase in pinolenic acid (all-cis-5, 9, 12–18: 3) in Korean pine nut oil by crystallization and its effect on LDL-receptor activity. Lipids 2004;39:383–387.10.1007/s11745-004-1242-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Maeda H, Hosokawa M, Sashima T, Funayama K, Miyashita K. Effect of medium-chain triacylglycerols on anti-obesity effect of fucoxanthin. J Oleo Sci 2007;56:615–621.10.5650/jos.56.615Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Hu X, Li Y, Li C, Fu Y, Cai F, Chen Q, et al. et al. Combination of fucoxanthin and conjugated linoleic acid attenuates body weight gain and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Arch Biochem Biophys 2012;519:59–65.10.1016/j.abb.2012.01.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Zhu XM, Hu JN, Xue CL, Lee JH, Shin ST, Hong ST, et al. et al. Physiochemical and oxidative stability of interesterified structured lipid for soft margarine fat containing Δ5-UPIFAs. Food Chem 2012;131:533–540.10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.018Search in Google Scholar

36. Choi JH, Kim BH, Hong SI, Kim CT, Kim CJ, Kim Y, et al. et al. Lipase-catalysed production of triacylglycerols enriched in pinolenic acid at the sn-2 position from pine nut oil. J Sci Food Agric 2012;92:870–876.10.1002/jsfa.4662Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Qian C, Decker EA, Xiao H, McClements DJ. Nanoemulsion delivery systems: Influence of carrier oil on β-carotene bioaccessibility. Food Chem 2012;135:1440–1447.10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Yu H, Huang Q. Improving the oral bioavailability of curcumin using novel organogel-based nanoemulsions. J Agric Food Chem 2012;60:5373–5379.10.1021/jf300609pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Sarkar A, Horne DS, Singh H. Interactions of milk protein-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions with bile salts in a simulated upper intestinal model. Food Hydrocoll 2010;24:142–151.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.08.012Search in Google Scholar

40. Kishore RSK, Pappenberger A, Dauphin IB, Ross A, Buergi B, Staempfli A, et al. et al. Degradation of polysorbates 20 and 80: Studies on thermal autoxidation and hydrolysis. J Pharm Sci-US 2011;100:721–731.10.1002/jps.22290Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Lethuaut L, Métro F, Genot C. Effect of droplet size on lipid oxidation rates of oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by protein. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2002;79:425–430.10.1007/s11746-002-0500-zSearch in Google Scholar

42. Tan CP, Nakajima M. β-Carotene nanodispersions: Preparation, characterization and stability evaluation. Food Chem 2005;92:661–671.10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.08.044Search in Google Scholar

43. Golding M, Wooster T,J. The influence of emulsion structure and stability on lipid digestion. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 2010;15:90–101.10.1016/j.cocis.2009.11.006Search in Google Scholar

44. McClements DJ, Li Y. Review of in vitro digestion models for rapid screening of emulsion-based systems. Food Funct 2010;1:32–59.10.1039/c0fo00111bSearch in Google Scholar

45. Golding M, Wooster TJ, Day L, Xu M, Lundin L, Keogh J, et al. et al. Impact of gastric structuring on the lipolysis of emulsified lipids. Soft Matter 2011;7:3513–3523.10.1039/c0sm01227kSearch in Google Scholar

46. Nik AM, Langmaid S, Wright AJ. Digestibility and β-carotene release from lipid nanodispersions depend on dispersed phase crystallinity and interfacial properties. Food Funct 2012;3:234–245.10.1039/C1FO10201JSearch in Google Scholar

47. Hsu JP, Nacu A. Behavior of soybean oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by nonionic surfactant. J Colloid Interface Sci 2003;259:374–381.10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00207-2Search in Google Scholar

48. Beysseriat M, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Preliminary study of the influence of dietary fiber on the properties of oil-in-water emulsions passing through an in vitro human digestion model. Food Hydrocoll 2006;20:800–809.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2005.08.001Search in Google Scholar

49. Dimitrova TD, Leal-Calderon F. Forces between emulsion droplets stabilized with Tween 20 and proteins. Langmuir 1999;15:8813–8821.10.1021/la9904758Search in Google Scholar

50. Yonekura L, Nagao A. Intestinal absorption of dietary carotenoids. Mole Nutr Food Res 2007;51:107–115.10.1002/mnfr.200600145Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Nik AM, Wright AJ, Corredig M. Micellization of beta-carotene from soy-protein stabilized oil-in-water emulsions under in vitro conditions of lipolysis. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2011;88:1397–1407.10.1007/s11746-011-1806-zSearch in Google Scholar

52. Yu H, Shi K, Liu D. Development of a food-grade organogel with high bioaccessibility and loading of curcuminoids. Food Chem 2012;131:48–54.10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.027Search in Google Scholar

53. Wang P, Liu HJ, Mei XY, Nakajima M, Yin LJ. Preliminary study into the factors modulating β-carotene micelle formation in dispersions using an in vitro digestion model. Food Hydrocoll 2012;26:427–433.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.11.018Search in Google Scholar

54. Yi J, Li Y, Zhong F, Yokoyama W. The physicochemical stability and in vitro bioaccessibility of beta-carotene in oil-in-water sodium caseinate emulsions. Food Hydrocoll 2014;35:19–27.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.07.025Search in Google Scholar

©2017 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Evolutionary Algorithm-Based Multi-objective Control Scheme for Food Drying Process

- Stability and Bioaccessibility of Fucoxanthin in Nanoemulsions Prepared from Pinolenic Acid-contained Structured Lipid

- Functional and Rheological Properties of Piñuela (Bromelia karatas) in Two Ripening Stages.

- Experimental Study on Heat and Mass Transfer of Millet in a Fixed Furnace

- Effects of Processing Treatments on the Antioxidant Properties of Polysaccharide from Cordyceps militaris

- Production and Preliminary Characterization of Antioxidant Polysaccharide by Submerged Culture of Culinary and Medicinal Fungi Cordyceps militaris CICC14013

- Effect of Heat Processing and Ultrasonication Treatment on Custard Apple Peroxidase Activity and Vitamin C

- Response Surface Methodology Approach for Optimization of Extrusion Process of Production of Poly (Hydroxyl Butyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) /Tapioca Starch Blends

- Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Walnut Extract as Influenced by the Extraction Method and Solvent

- Optimization of the Spray-Drying Process for Developing Stingless Bee Honey Powder

Articles in the same Issue

- Evolutionary Algorithm-Based Multi-objective Control Scheme for Food Drying Process

- Stability and Bioaccessibility of Fucoxanthin in Nanoemulsions Prepared from Pinolenic Acid-contained Structured Lipid

- Functional and Rheological Properties of Piñuela (Bromelia karatas) in Two Ripening Stages.

- Experimental Study on Heat and Mass Transfer of Millet in a Fixed Furnace

- Effects of Processing Treatments on the Antioxidant Properties of Polysaccharide from Cordyceps militaris

- Production and Preliminary Characterization of Antioxidant Polysaccharide by Submerged Culture of Culinary and Medicinal Fungi Cordyceps militaris CICC14013

- Effect of Heat Processing and Ultrasonication Treatment on Custard Apple Peroxidase Activity and Vitamin C

- Response Surface Methodology Approach for Optimization of Extrusion Process of Production of Poly (Hydroxyl Butyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) /Tapioca Starch Blends

- Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Walnut Extract as Influenced by the Extraction Method and Solvent

- Optimization of the Spray-Drying Process for Developing Stingless Bee Honey Powder