Abstract

A series of experiments on the heat and mass transfer of millet particles are conducted in order to demonstrate the effects on drying characteristics of particles in this work. Experimental results illustrate that thermal conductivity between particles is significantly influenced by temperature and moisture content of millet particles. The temperature of particles in axial and radial direction increases because of the increase of inner wall temperature and decreases with the increase of air flow velocity. Moreover, the moisture content of particles near the inner wall has experienced a significant drop with the increase of inner wall temperature. As a consequence, the increase of air flow velocity results from the decrease of particles moisture content and drying rate of particles increases due to the increase of air flow velocity. Furthermore, the accumulated height of particles has barely influenced on the drying characteristics of millet particles.

1 Introduction

In general, drying processes are commonly applied in the fields of chemical, cement, coal, pharmaceuticals, microbiological, energy, food and other industries [1–3]. The drying processes are extremely complicated and incorporated. Inter-component heat and mass transfer usually occurs between the gas phase and solid phase during drying processes [4]. Furthermore, the drying process is also of significance to granular particles which are loosely piled in gas or fluid phase. The particles can be moist removed, heated, and mixed in the drying equipment. Moreover, drying methods are widely used to store food by removing the moisture from materials through thermal treatment and keeping materials in an optimal temperature as well. It is well known that the internal self-heating starts to take place at a storage temperature from 30 oC to 50 oC [5–7].

The whole drying process constitutes a sequence of periods, for instance, preheating period, constant drying rate period, falling drying rate period and lag drying rate period [8]. During these drying periods, the energy obtained from outside can be transferred to the particles. As a consequence, free water flows from the lower moisture content region to the higher within a particle. Generally, the moisture near the surface region can be firstly removed. Hence, the moisture content at the region that farther from the surface is higher than other regions in a particle [9]. During the preheating period, wet material particles are heated and the surface moisture on the particles is evaporated at the beginning of a drying process. However, the moisture in the particles can be hardly transported to the surface due to temperature gradient between particles and the surrounding atmosphere. Hence, the moisture content of particles slightly decreases, and the temperature marginally increases. The duration of preheating period depends on the thickness of material particles and the temperature gradient gradually reduces in the constant drying rate period. Furthermore, the surface water vapor pressure of particle stays in a saturation state. The heat obtained from the outside totally meets the requirements of vaporization. The temperature even decreases in some operational conditions in this period. Free water (including capillary water and permeability water) in particles is more freely moved towards the surface and then evaporated. Generally, the temperature of particles in this period remains steady and the moisture content dramatically declines. The speed of drying rate slightly drops until the value of moisture content reaches to a lower point. The particles characteristics mentioned above mean that the falling drying rate period comes. A majority of water in particles is the multi-layer adsorption water in the falling drying rate period and few moisture is evaporated. The value of particle moisture content is equal to the critical moisture content. In addition, the drying process finishes until the value of particle drying rate gradually reaches to the minimum and keeps its stability in the lag drying period. Finally, the moisture content of material particle is the same as equilibrium moisture content, which is critically controlled by the temperature and humidity of the air in the surrounding atmosphere, and so on. Furthermore, material particles, like sand, glass beads, are reported to have longer duration of constant drying rate period and shorter linear falling drying rater period. However, fibrous materials and food grains have a shorter constant falling drying period and longer curvy linear falling drying rate period [10, 11].

Drying characteristics of some particles, for instant, gypsum, silica gel and millet, were measured by a thermogravimetric analyser [12]. The results were obtained by the approach mentioned above, which indicated that the equilibrium moisture content of solid particles decreased with the increasing of gas temperature. The critical moisture content and the effective dispersion coefficient increased. A series of equations was used to calculated the temperature distribution in a spherical particle in gaseous medium under different operating conditions during convective drying processes [13]. A second order partial differential equation was used to calculate the transient temperature distribution within a container [14]. Millet particles were traditionally processed with the germination and fermentation prior to consumption. Various experiments were conducted to determine their drying behaviors on the millet in a laboratory-scale fluidized bed dryer [15]. It usually can be described as a crucial and industrial preservation method. Moreover, the moisture content and activity of agricultural and biological products were reduced to the optimal deterioration in biochemical, chemical, and microbiological processes. The effects of solid feed rate, velocity and temperature of gas flow on the millet drying efficiency were researched in a rectangular multistage fluidized bed [16]. In general, fixed and fluidized beds were described as the most apparent devices for measuring single particle drying kinetics because of the same residence time, which all particles stay in the operating equipment [17, 18]. The drying processes are usually influenced by the structure characteristics of material particles, vaporization rate of surface and internal moisture diffusion rate. In addition, a number of typical drying equipment, such as fixed bed dryers, fluidized bed dryers, rotary dryers and microwave dryers have been used to deal with particles in many attempts. Moreover, several researchers found out the investigations on the heat and mass transfer between material particles and gas flow. Myklestad firstly predicted product moisture content of particles throughout a single pass dryer [19]. A series of parameters, for example, the temperature of drying gas flow, initial moisture content of particles and the feed rate of product, has been taken into account. Arrhenius equation was used to calculate the correlation between particles temperature and the efficient coefficient in mass transfer [20, 21]. Therefore, the moisture content and temperature of wood particles were studied based on the theories of heat and mass transfer [22].

Sharples have established a model to study and simulate the heat and mass transfer during drying processes in rotary dryers [23]. It could be assumed that gas flow among particles was stationary and the heat transfer between gas phase and solid phase was negligible when the heat conduction in granular materials was studied. The Thermal Particle Dynamics (TPD) model was put forward in that study [24]. The experimental results on the drying kinetics of millet particles were obtained in fluidized beds. It indicated that the drying rate significantly grew with the increase of temperature and marginally rose with flow rate of the heating medium. However, the decrease of drying rate resulted from the increase of solids holdup [25]. Various experiments were carried out on drying characteristics of coal particles at different kinds of particle bed height in fixed beds. The results illustrated that the material particles had a long falling drying rate period rather than a constant drying rate period [26]. The thin-layer method is employed for large particles and the moisture loss during drying process can be easily measured. However, for smaller particles, the approach mentioned above hardly meets the measuring requirement due to the disturbing and wobbling of particle by the effects of gas flow. The drying kinetics of particle are represented by the diffusion coefficient instead of characteristics drying curve. Meanwhile, the method fails to accurately investigate the drying characteristics in a broad range of particle sizes [27, 28]. Shapes of biomass particles were modeled and proposed to analyze the heat and mass transfer in a vertical cylindrical laboratory furnace [29]. An overview of emerging and innovative thermal drying technologies was taken, which was commercialized the potential for industrial exploitation [30]. Furthermore, a one-dimensional model for pneumatic drying of food was presented in order to study the effects of mass flow rate, velocity and temperature of gas flow, and shape of particle on the drying time and moisture content of material particles [31]. A theoretical model on a single wet particle was explored to calculate the unsteady characteristics of heat and mass transfer during the drying process [32]. These researches played an crucially significant role on the drying processes.

Although the considerable works on drying characteristics have been done, there is still lacking scientific and appropriate information on drying behaviors of granular particles. Furthermore, the heat and mass transfer commonly takes place between material particles and gas flow in the industrial drying processes. Therefore, in order to improve drying efficiency and provide more reasonable information, it is necessary to experimentally investigate and analyze the heat and mass transfer on particles. In this work, a series of experiments has been performed by varying the wall temperature, velocity of gas flow and particle pile height, to study the drying characteristics on granular particles.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Setup

The heat transfer and mass transfer on natural packing structure of granular particles within a fixed furnace were experimentally studied. In addition, the thermal conduction between particles and inner wall of the furnace, particles to particles, convection heat and mass transfer between particle to gas flow were taken into account. The experimental apparatus used in this study was derived, which was composed of four main systems, heating system, air supply system, data collection system and circulation water system, as can be seen in Figure 1. A schematic diagram of this experimental furnace is shown in Figure 2. Physical parameters of the fixed furnace are listed in Table 1. The inner wall of the furnace was heated by oil bath method, and the temperature was controlled by the heating system. Material particles were heated transferred from the inner wall at a certain temperature. The approach was applied to these experiments due to the good maneuverability and uniformity. The oil bath was surrounded by thermal insulation materials so that the heat loss could be reduced to the minimum. The value of heated height was 220 mm. In order to meet the requirements of a uniform experimental atmosphere on air flow, an air distribution plate was setup at the bottom of the furnace. It covered a large number of holes with the diameter of 1 mm. As a consequence, air flow was uniformly supplied to the heated region through the air distribution plate.

A schematic diagram of experimental setup.

A structural diagram of laboratory-scale furnace. 1. Thermal insulation materials; 2. Oil bath; 3. Air distribution plate; 4. Air duct; 5. Cover.

Physical parameters used in this study.

| Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter of fixed furnace, mm | 260 |

| Diameter of heated inner wall, mm | 72 |

| Height of heated region, mm | 220 |

| Thickness of oil bath, mm | 75 |

| Diameter of the air distribution, mm | 71 |

| Diameter of millet particle, mm | 1.2 |

| Diameter of air supply cross-section, mm | 8 |

2.2 Materials

A series of experiments were performed by using 1.2 mm millet particles, which were strictly selected by a vibrator. The air flow was compressed from outside and the inlet temperature of air flow was the same as the temperature of atmosphere in the room. The moisture content of cereals and cereal products can be determined by the routine reference method [33]. Therefore, the moisture content of millet particles were accurately measured by the oven method. Experimental millet particles can not be broken up into powders because the diameter of particles was selected and the value of below 1.7 mm. All experimental millet particles were stored and balanced in a room with the constant temperature (22±1 oC) and humidity (60 %±2 %) for 48 h before being used. Approximately 5 g sample of millet particles were scooped out of a tight store box. In addition, sample particles were stored in air tight container that were weighed before drying in a convective air oven for 2 h at 130 oC±3 oC. Adding a certain quality of water or experimental particles into boxes with the purpose of satisfying with experimental requirements.

2.3 Methods and procedures

Radiation heat transfer is negligible in dense granular particles below 600 oC [34]. The thermal conduction differential equations [35] are performed under the experimental conditions without gas flow in this paper, which are given by

where

Equation (2) can be also simplified as follow

The thermal conduction differential equation can be described by cylindrical coordinates, is given by

where, physical parameters λ, ρ and Cp represent the thermal conductivity, density and heat capacity of a particle, which are determined by the complex nature of the particle. Hence, Φ is the source term, a is introduced and represents the thermal diffusivity of particle, t and ∇2t are the temperature and Laplacian operator of temperature, respectively.

The air flow was supplied from the bottom of the furnace by an air compressor and the velocity of air flow was completely controlled by a D08-1F rotameter. The experimental atmosphere reached to a stable state for 30 min, then millet particles were naturally and rapidly accumulated to a certain height, which could be controlled by a scalable stent. The thermocouples were distributed in the accumulation body of millet particles in a short time, and the thermocouples distribution are presented in Figure 3. Millet particles were heated for 45 min in the fixed furnace and the temperature data of each point was collected and reported by a data acquisition computer. Furthermore, the experimental steps above were repeated for three times and the mean temperatures obtained were considered to the temperatures of millet particles at each point. However, it is extremely difficult to measure the moisture content of millet particle on time in an experimental condition due to the change of particles accumulated height, which results in large errors of the moisture content. Therefore, the moisture content of millet particles was measured every 5 min. Moreover, the accumulation body of millet particles was divided into five layers and the particles at each layer were separately measured. The measuring points of moisture content distribution were shown at Figure 4. Approximately 5 g sample of millet particles were scooped out of each measuring point within the packing millet particles. In addition, sample particles were stored in a responding air tight container, and then they were weighed after drying in a convective air oven for 2 h at 130 oC±3 oC.

The distribution of thermocouples measuring points in axial and radial direction. (a) Axial direction, (b) Radial direction.

The distribution of moisture content measuring points in axial and radial direction. (a) Axial direction, (b) Radial direction.

In a practical drying process, the heat and mass transfer characteristics were apparently presented by the temperature and moisture content. As a consequence, a series of experimental conditions, including inner wall temperature, velocity of air flow and accumulated height of particles, was taken into account in order to completely analyze the drying characteristics of millet granular particles. Table 2 reports the experimental conditions that are used in this paper.

Experimental conditions that were used in this paper.

| Conditions | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter of particle, mm | 1.2 |

| Environment temperature, oC | 20 |

| Initial temperature of particle, oC | 20 |

| Initial moisture content of particle, % | 0.21 |

| Drying time, min | 45 |

| Inner wall temperature, oC | 90,100,110,120,130 |

| Velocity of air flow, m/s | 1,2,3 |

| accumulated height of particles, mm | 160,180,200 |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effects of inner wall temperature

The heat and mass transfer on natural packing millet particles in a static state have been studied. The results indicate that particles near the inner wall of furnace are firstly and directly heated. In addition, a part of the heat obtained from the inner wall is transported to the particles next to them through thermal contact conductance. Then, the heat is gradually transported to the particles at the center. In order to investigate the significant effect on the heat conduction of millet particles, a series of operating conditions on inner wall temperatures, 90, 100, 110, 120 and 130 oC, is performed. Furthermore, no air flow is compressed into the furnace under these experimental conditions. Temperature measuring points are marked as Tc-L1, Tc-L2, Tc-L3, Tc-L4, Tc-L5, respectively, in the axial direction. Temperature measuring points are marked as Tc-R1, Tc-R2, Tc-R3, Tc-R4, Tc-R5, respectively, in the radial direction.

The temperature of each measuring point in axial direction (L1, L3 and L5) is plotted in Figure 5. It shows that the temperature of particles in axial direction increases with the increase of inner wall temperature. From Figure 5, it can be found that the temperature profiles under the condition of 110 oC is different from the other conditions. At the L1 measuring point, the particles obtain a large number of heat to improve the temperature. The moisture from the particles at the bottom of the fixed bed is diffused to the top by the air flow when the wall temperature is less than 110 oC. Therefore, amount of moisture is accumulated at the top, which leads to the temperature of particles fast increasing. The temperature distribution of particles is inhomogeneous in the fixed bed, especially for the particles at the top. Particles within 100 mm of accumulation body, the temperature of particles fluctuates frequently during the preheating drying period. Specifically, at 120 oC and 130 oC, the temperature of particles tends to the consistent. The millet particles at the L1 measuring point stay in the constant drying rate period for nearly 300 s. However, at the L2 and L3 measuring point, particles stays for 600 s and 720 s, respectively. The natural convection occurs between particles at the surface of millet accumulation body and the air under the top cover. Therefore, the temperature of particles at the top is marginally lower than the particles at the bottom of accumulation body. Compared with the temperatures of particles at measuring point L1 and L2, the rising speed of particles temperature at L3 is the highest, as shown in Figure 5(a) and Figure 5(b). The results for L3 and L4 measure point illustrate that the heat conduction between particles and inner wall plays a vital role on the particles, especially for the particles at lower half of millet accumulation body. With a higher inner wall temperature, more heat is transferred from the particles near inner wall to the center. As a result, the period of constant drying rate for those millet particles is shorter and the value of constant drying rate period is 120 s. Moreover, the mass transfer within the particle is hardly influenced by the intrinsic characteristics of the particles.

Temperature of millet particles in axial direction. (a) Tc-L1, (b) Tc-L3, (c) Tc-L5.

Temperature variations of millet particles in radial direction (R1, R3 and R5) are shown in Figure 6. The figures address the effect of inner wall temperature on particles. It obviously illustrates that the temperature of particles increase with the increase of inner wall temperature in radial direction. In addition, the shorter distance between particles and the inner wall leads to the increase of rising speed of temperature, as shown in Figure 6(a) and Figure 6(b). The heat obtained from inner wall is used to improve the temperature of particles at the upper half of millet accumulation body. Meanwhile, the heat obtained from the outdoor is not only used to rise the temperature, but also to transport the moisture among particles at the lower half of millet accumulation body. As a consequence, the temperature of particles at measuring point R5 is slightly lower than the temperature of particles at R4 based on the experimental results.

Temperature of millet particles in radial direction (a) Tc-R1 (b) Tc-R3 (c) Tc-R5.

Moisture content is another crucial index that is used to demonstrate the effects of operational conditions on drying characteristics of the particles. Hence, the moisture content of millet particles at each layer is plotted under five different inner wall temperatures: 90 oC, 100 oC, 110 oC, 120 oC and 130 oC, as shown in Figure 7. The moisture content curves illustrate that the moisture content of particles significantly falls during the drying process. For those particles at the center of the accumulation body, the moisture content of particles reduces by 4 %. Moreover, the moisture content of the first layer particles near the inner wall is reduced to 14.06 % under inner wall temperature condition of 90 oC, as shown in Figure 7(a). The particles near the inner wall obtain more heat and the moisture of particles is transported along the radial and axial direction. Therefore, less heat and more moisture is obtained by the particles near the center. As a result, the moisture content of particles rises during the drying process. It shows that the moisture content of particles at the bottom of the accumulation body marginally grows at the beginning of the drying process, as shown in the layer 5 at Figure 7(a). When the inner wall temperature reaches to 100 oC, the Figure 7(b) addresses that the moisture content of particles firstly increases and then drops. As a consequence, the millet accumulation body can be hardly uniformly dried. The moisture content of particles near the inner wall declines from 21 % to 14 % after the particles being dried for 45 min. The moisture content of particles at the center slightly reduces to nearly 19 %. However, the heat conduction has a vital impact on the particles under the experimental conditions of 110 oC and 120 oC inner wall temperature. Therefore, the moisture content of particles at the center decreases at first and then increases due to the change of moisture, which is gradually obtained from the surrounding particles, as shown in Figure 7(c) and Figure 7(d). With the increase of inner wall temperature, the moisture content of particles at the surface of the accumulation body marginally rises because the speed of mass transfer from the bottom to the top of accumulation body increases, as it can be seen in Figure 7(e). From Figure 7, it indicates that the moisture content of millet particles at the upper layer is always higher than that of at the lower layer. Meanwhile, the moisture content of millet particles at the center is higher than that of near the fixed bed wall. The water from the surface of particles diffused from the lower to the upper, which results in the inhomogeneous distribution of moisture content inside the fixed bed. Moreover, the heat obtained from the wall conduces to removing the water of particles, which near the wall. However, for these particles that near the wall, a part of water flows from the upper to the lower due to the gravity. For these particles at the center, the water can be diffused to the surrounding environment by the air flow.

Moisture content of millet particles under different inner wall temperature. (a) 90 oC, (b) 100 oC, (c) 110 oC, (d) 120 oC, (e) 130 oC.

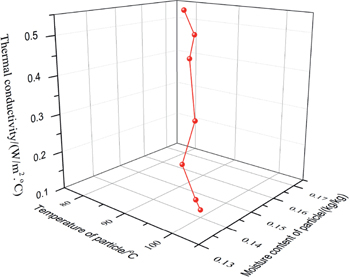

Figure 8 reports the effects of temperature and moisture content on the thermal conductivity of millet particles. The value range of thermal conductivity λ is 0.146~0.535 W/(m2·oC) under the temperature T range of 80 oC to 102 oC and the moisture content M of 13.58 % to 16.76 %. A new formula is used to describe the relation among the thermal conductivity, temperature and moisture content of millet particles as follows,

The effects of temperature and moisture content on the thermal conductivity of millet particles.

It demonstrates that the thermal conductivity of particles is significantly influenced by the temperature and moisture content. Furthermore, the increase of moisture content leads to raising the thermal conductivity of particles and a higher temperature of particle results in a lower thermal conductivity. The diameter of particles slightly inclines due to the loss of moisture during the heating process. As a consequence, the thermal heat transfer between particles is marginally weakened in the furnace.

3.2 Effects of air flow velocity

Convection heat and mass transfer are of significance to the drying behaviors on natural accumulated millet particles in a static state. In order to find out the effects of air flow on the convection heat and mass transfer between millet particles and air flow, the velocity of air flow is taken into account in this study. The values of air flow are 1 m/s, 2 m/s and 3 m/s, respectively. Two indexes, temperature and moisture content, are represented to describe the drying characteristics of millet particles under those experimental conditions. The values of initial temperature and moisture content of particles, inner wall temperature and accumulated height are 20 oC, 21 %, 110 oC and 200 mm, respectively. Temperature and moisture content of millet particles along the axial and radial direction in the fixed furnace are accurately measured. The results are plotted in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Temperature of particles under different air flow velocity in axial direction. (a) Tc-L1, (b) Tc-L3, (c) Tc-L5.

Temperature of particles under different air flow velocity in radial direction. (a) Tc-R1, (b) Tc-R3, (c) Tc-R5.

Millet particles are naturally accumulated in the fixed furnace and there is a little space among the particles. After being compressed by a compressor, the air flows from the bottom of the furnace to the top through these space. Furthermore, the air flow is gradually heated and humidified during the drying process. Therefore, the convection heat and mass transfer between the air flow and particles at the lower of the accumulation body are stronger than the particles at the upper of the accumulation body. The particles, which at the top of accumulation body, are still significantly influenced by the heat conduction from the inner wall, and slightly affected by the convection heat transfer, as shown in Figure 9(a). The particles at the lower of accumulation body are heated at the preheating period. The convection heat transfer rate is less than the heat obtained from the inner wall, which contributes to the increase of particles temperature. In addition, the increase of contact area between particles and the air flow leads to the enhancement of the convection heat and mass transfer between the particles and the air flow. It demonstrates that the temperature of particles reduces due to the increase of the air flow velocity. The maximum of particles temperature is 35 oC under the condition of 1 m/s air flow velocity, as shown in Figure 9(b) and Figure 9(c).

The temperature of particles in radial direction as a result of the inner wall temperature. It indicates that the shorter distance between particle and inner wall, the higher temperature of particle is. However, the convection heat and mass transfer between particles and the air flow are enhanced. The temperature of particles drops because of the increase of air flow velocity at the same drying time. Moisture in particles is evaporated through convection heat and mass transfer, especially for those particles near the inner wall. Therefore, more heat is obtained and used to increase the temperature of the particles. The maximum value of temperature is 53 oC, as shown in Figure 10.

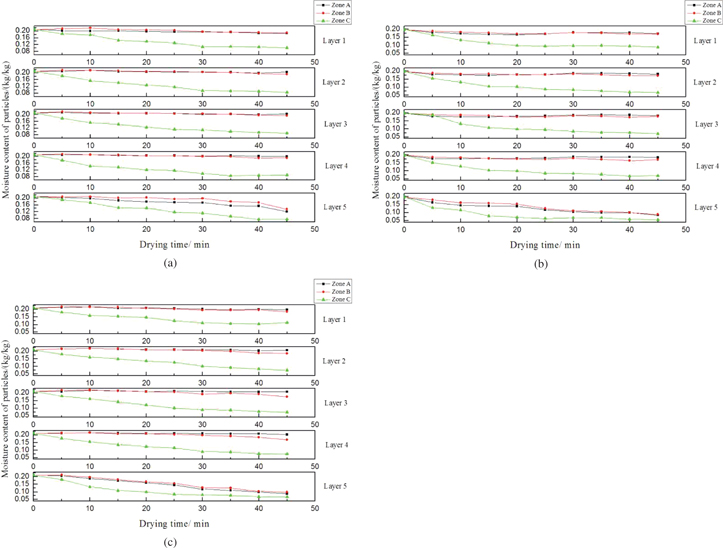

The moisture content of particles at each layer under different air flow velocity is represented in the Figure 11. It clearly shows that the moisture content of particles above the layer 5 at the zone A and zone B slightly changes. The range of moisture content is nearly from 21 % to 18 %. However, the moisture content of particles near the inner wall obviously declines due to the effect of heat conduction and convection. Moreover, the air flow results in the rising speed of drying rate, especially for the particles at the lower of the accumulation body. As the value of air flow velocity is 1 m/s, the moisture content of particles at the center falls to 12.04 % and the particles near the inner wall declines to 7.5 %. With the increase of air flow velocity, the particles are sharply heated and dried. Furthermore, the final moisture content of particles ranges from 5.59 % to 8.43 % at the air flow velocity of 2 m/s, as shown in Figure 11(b). When the value of air flow velocity reaches to 3 m/s, it can be clearly found that the particles are more uniformly dried. The difference of moisture content between particles at the center and the boundary decreases.

Moisture content of particles under different air flow velocity. (a) 1 m/s, (b) 2 m/s, (c) 3 m/s.

3.3 Effects of particles accumulated height

The heat and moisture are transported along the axial and radial direction, three accumulated heights, including 160 mm, 180 mm and 200 mm, have been explored in this study. The drying behaviors on temperature in axial and radial direction are given in Figure 12 and Figure 13, respectively. The values of atmosphere, inner wall and initial particles temperature are 20 oC, 110 oC and 20 oC, respectively. The value of air flow velocity is 2 m/s. From Figure 12 and Figure 13, they demonstrate that the temperature of particles at the center slightly changes in axial direction, which increases at first during the preheating period and then drops to a constant temperature. However, the temperature difference between the bottom and the top of accumulation body is less than 5 oC. When the value of accumulated height is 180 mm, the temperature of particles in the half height of the accumulation body is the highest in radial direction compared with the experimental conditions of 160 mm and 200 mm in height.

Temperature of particles in axial direction under different accumulated height. (a) Tc-L1, (b) Tc-L3, (c) Tc-L5.

Temperature of particles in radial direction under different accumulated height. (a) Tc-R1, (b) Tc-R3, (c) Tc-R5.

As can be seen from Figure 14, the effects of particles accumulated height on drying behavior of particles. It obviously presents that the moisture content of particles at the top of accumulation body marginally decreases at the accumulated height of 160 mm. However, the particles at the bottom of the accumulation body are barely influenced by the accumulated height. The moisture of particles obtained from the particles next to them is nearly equal to the loss by convection mass transfer for the particles at the center so that the moisture content of particles nearly remains steady. Therefore, the accumulated height of particles has little impact on the heat and mass transfer of particles under those experimental conditions.

Moisture content of particles under different accumulated height. (a) 160 mm, (b) 180 mm, (c) 200 mm.

4 Conclusion

A series of experiments are conducted in this study in order to demonstrate the significance of heat and mass transfer on millet particles. In addition, the temperature and moisture content are two crucial indexes that are generally used to describe the drying characteristics of millet particles. Therefore, the inner wall temperature, air flow velocity and accumulated height of millet particles are taken into account and experimentally studied. The main results are presented as follows:

The temperature of particles in axial and radial direction increases due to the increase of inner wall temperature. The moisture content of particles near the inner wall has experienced a significant drop with the rise of inner wall temperature. However, the moisture content of particles at the center marginally increases under these experimental conditions. The thermal conductivity between particles is significantly influenced by the temperature and moisture content of particles.

The temperature of particles declines in axial and radial direction with the increases of air flow velocity due to the space in the accumulation body. The heat and mass transfer among the particles are enhanced by air flow. The increase of air flow velocity leads to the decrease of particles moisture content. Moreover, the drying rate drops with the decrease of air flow velocity.

The accumulated height of particles has barely influenced on the drying characteristics of millet particles under those experimental conditions in this study.

In summary, results on the heat and mass transfer suggest that it should apply in drying and storing processes on food products. Hence, in order to find out more optimal operating conditions, further research will focus on the heat and mass transfer of moist granular particles by adopting simulation methods in different structures, such as flexible filamentous particles.

Nomenclature

- r

Radius of a fixed bed, (m)

- τ

Time, (s)

- λ

Thermal conductivity of a particle, (W/(m·K))

- ρ

Density of a particle, (kg/m3)

- Cp

Heat capacity of a particle, (kJ/(kg·K))

- t

Temperature, (K)

- Φ

Source term, (W)

- a

Thermal diffusivity of a particle, (m2/s)

Acknowledgements

Financial supports from the Key Laboratory of Tobacco Processing Technology of Zhengzhou Tobacco Research Institute of China National Tobacco Corporation are sincerely acknowledged.

References

1. Barr P, Brimacombe J, Watkinson A. A heat-transfer model for the rotary kiln: Part I. Pilot Kiln trials. Metall Mater Trans B 1989;20:391–402.10.1007/BF02696991Search in Google Scholar

2. Zahed AH, Zhu JX, Grace JR. Modelling and simulation of batch and continuous fluidized bed dryers. Drying Technol 1995;13:1–28.10.1080/07373939508916940Search in Google Scholar

3. Gao YJ, Glalsser JB, Ierapetritou GM. Measurement of residence time distribution in a rotary dryer calciner. AIChE J 2013;59:4068–4076.10.1002/aic.14175Search in Google Scholar

4. Palancz B. A mathematical model for continuous fluidized bed drying. Chem Eng Sci 1983;38:1045–1059.10.1016/0009-2509(83)80026-8Search in Google Scholar

5. Hosseinabadi HZ, Layeghi M, Berthold D. Mathematical modeling the drying of poplar wood particles in a closed-loop triple pass rotary dryer. Drying Technol 2013;32:55–67.10.1080/07373937.2013.811250Search in Google Scholar

6. Herrmann H. Grains of understanding. Phys World 1997;10:31–34.10.1088/2058-7058/10/11/29Search in Google Scholar

7. Bridgewater J. Particle technology. Chem Eng Sci 1995;50:4081–4089.10.1016/0009-2509(95)00225-1Search in Google Scholar

8. Zhu WX. Principle and technology of food drying. Beijing: Science Press, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

9. Morteza G, Mehdi RH, Seyed JH. Optimization of drying-tempering periods in a paddy rice dryer. Drying Technol 2011;30:106–113.10.1080/07373937.2011.618281Search in Google Scholar

10. Strumillo C, Kudra T. Drying: principles, applications and design. New York: Gorden and Breach, 1986.Search in Google Scholar

11. Srinivasakannan C, Subbarao S, Varma YB. A kinetic model for drying of solids in batch fluidized beds. Ind Eng Chem Res 1994;33:363–370.10.1021/ie00026a029Search in Google Scholar

12. Park YS, Shin HN, Lee DH. Drying characteristics of particles using thermogravimetric analyzer. Korean J Chem Eng 2003;20:1170–1175.10.1007/BF02706957Search in Google Scholar

13. Fedosov SV, Lebedev VY, Barulin EP. Temperature field in a spherical particle during quasisteady high-intensity drying. J Eng Phys 1981;42:864–867.10.1007/BF00836551Search in Google Scholar

14. Guo WD, Lim J, Bi XT. Determination of effective thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity. Fuel 2013;103:347–355.10.1016/j.fuel.2012.08.037Search in Google Scholar

15. Shingare SP, Thorat BN. Effect of drying temperature and pretreatment on protein content and color changes during fluidized bed drying of finger millets (Ragi, Eleusine coracana) sprouts. Drying Technol 2013;31:507–518.10.1080/07373937.2012.744033Search in Google Scholar

16. Choi KB, Park S, Park YS. Drying characteristics of millet in a continuous multistage fluidized bed. Korean J Chem Eng 2002;19:1106–1111.10.1007/BF02707240Search in Google Scholar

17. Tsotsas E. Measurement and modelling of intraparticle drying kinetics. 1992 Process 8th Int Drying Symp,.Search in Google Scholar

18. Burgschweiger J, Tsotsas E. Experimental investigation and modelling of continuous fluidized bed drying under steady-state and dynamic conditions. Chem Eng Sci 2002;57:5021–5038.10.1016/S0009-2509(02)00424-4Search in Google Scholar

19. Myklestad O. Heat and mass transfer in rotary dryers. Chem Eng Process Symp Ser 1963;59:129–137.Search in Google Scholar

20. Henderson SM. Progress in developing the thin layer drying equation. Trans ASAE 1974;17:1167–1172.10.13031/2013.37052Search in Google Scholar

21. Sawhney RL, Pangavhane DR, Sarsavadia PN. Drying kinetics of single layer Thompson seedless grapes under heated ambient air conditions. Drying Technol 1999;17:215–236.10.1080/07373939908917526Search in Google Scholar

22. Kamke FA, Wilson JB. Computer simulation of a rotary dryer. Part II: heat and mass transfer. Am Inst Chem Engineers J 1986;32:269–275.10.1002/aic.690320214Search in Google Scholar

23. Sharples K, Glikin PG, Warne R. Computer simulation of rotary driers. Trans Inst Chem Eng 1964;42:275–284.Search in Google Scholar

24. Vargas WL, McCarthy JJ. Heat conduction in granular materials. AIChE J 2001;47:1052–1059.10.1002/aic.690470511Search in Google Scholar

25. Srinivasakannan C, Balasubramanian N. An investigation on drying of millet in fluidized beds. Adv Powder Technol 2009;20:298–302.10.1016/j.apt.2008.10.010Search in Google Scholar

26. Pusat S, Akkoyunlu MT. Effects of bed height and particle size on drying of a Turkish lignite. Int J Coal Prep Utilization 2015;35:196–205.10.1080/19392699.2015.1009051Search in Google Scholar

27. Adanez J, Gayan P, Garcia-Labiano F. Comparison of mechanistic models for the sulfation reaction in a broad range of particle sizes of sorbents. Ind Eng Chem Res 1996;35:2190–2197.10.1021/ie950389cSearch in Google Scholar

28. Fyhr C, Kemp IC. Evaluation of the thin-layer method used for measuring single particle drying kinetics. Inst Chem Eng 1998;76:815–822.10.1205/026387698525568Search in Google Scholar

29. Igor B, Bernard F, Anes K. Cylindrical particle modelling in pulverized coal and biomass co-firing process. Appl Thermal Eng 2015;78:74–81.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.12.047Search in Google Scholar

30. Jangam SV. An overview of recent developments and some research and development challenges related to drying of foods. Drying Technol 2011;29:1343–1357.10.1080/07373937.2011.594378Search in Google Scholar

31. Pelegrina AH, Crapiste GH. Modelling the pneumatic drying of food particles. J Food Eng 2001;48:301–310.10.1016/S0260-8774(00)00170-9Search in Google Scholar

32. Mezhericher M, Levy A, Borde I. Heat and mass transfer of single droplet/wet particle drying. Chem Eng Sci 2008;63:12–23.10.1016/j.ces.2007.08.052Search in Google Scholar

33. GB/T21305—2007. Cereals and cereal products–determination of moisture content–Routine reference method. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

34. Mansoori Z, Saffar AM, Basirat TH. Inter particle heat transfer in a riser of gas solid turbulent flows. Powder Technol 2005;159:35–45.10.1016/j.powtec.2005.05.061Search in Google Scholar

35. Yang SM, Tao WQ. Heat transfer. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

©2017 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Evolutionary Algorithm-Based Multi-objective Control Scheme for Food Drying Process

- Stability and Bioaccessibility of Fucoxanthin in Nanoemulsions Prepared from Pinolenic Acid-contained Structured Lipid

- Functional and Rheological Properties of Piñuela (Bromelia karatas) in Two Ripening Stages.

- Experimental Study on Heat and Mass Transfer of Millet in a Fixed Furnace

- Effects of Processing Treatments on the Antioxidant Properties of Polysaccharide from Cordyceps militaris

- Production and Preliminary Characterization of Antioxidant Polysaccharide by Submerged Culture of Culinary and Medicinal Fungi Cordyceps militaris CICC14013

- Effect of Heat Processing and Ultrasonication Treatment on Custard Apple Peroxidase Activity and Vitamin C

- Response Surface Methodology Approach for Optimization of Extrusion Process of Production of Poly (Hydroxyl Butyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) /Tapioca Starch Blends

- Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Walnut Extract as Influenced by the Extraction Method and Solvent

- Optimization of the Spray-Drying Process for Developing Stingless Bee Honey Powder

Articles in the same Issue

- Evolutionary Algorithm-Based Multi-objective Control Scheme for Food Drying Process

- Stability and Bioaccessibility of Fucoxanthin in Nanoemulsions Prepared from Pinolenic Acid-contained Structured Lipid

- Functional and Rheological Properties of Piñuela (Bromelia karatas) in Two Ripening Stages.

- Experimental Study on Heat and Mass Transfer of Millet in a Fixed Furnace

- Effects of Processing Treatments on the Antioxidant Properties of Polysaccharide from Cordyceps militaris

- Production and Preliminary Characterization of Antioxidant Polysaccharide by Submerged Culture of Culinary and Medicinal Fungi Cordyceps militaris CICC14013

- Effect of Heat Processing and Ultrasonication Treatment on Custard Apple Peroxidase Activity and Vitamin C

- Response Surface Methodology Approach for Optimization of Extrusion Process of Production of Poly (Hydroxyl Butyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) /Tapioca Starch Blends

- Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Walnut Extract as Influenced by the Extraction Method and Solvent

- Optimization of the Spray-Drying Process for Developing Stingless Bee Honey Powder