Intracellular spatially-targeted chemical chaperones increase native state stability of mutant SOD1 barrel

-

Sara S. Ribeiro

, David Gnutt

, Felix Lindner

and Simon Ebbinghaus

Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurological disorder with currently no cure. Central to the cellular dysfunction associated with this fatal proteinopathy is the accumulation of unfolded/misfolded superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in various subcellular locations. The molecular mechanism driving the formation of SOD1 aggregates is not fully understood but numerous studies suggest that aberrant aggregation escalates with folding instability of mutant apoSOD1. Recent advances on combining organelle-targeting therapies with the anti-aggregation capacity of chemical chaperones have successfully reduce the subcellular load of misfolded/aggregated SOD1 as well as their downstream anomalous cellular processes at low concentrations (micromolar range). Nevertheless, if such local aggregate reduction directly correlates with increased folding stability remains to be explored. To fill this gap, we synthesized and tested here the effect of 9 ER-, mitochondria- and lysosome-targeted chemical chaperones on the folding stability of truncated monomeric SOD1 (SOD1bar) mutants directed to those organelles. We found that compound ER-15 specifically increased the native state stability of ER-SOD1bar-A4V, while scaffold compound FDA-approved 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA) decreased it. Furthermore, our results suggested that ER15 mechanism of action is distinct from that of PBA, opening new therapeutic perspectives of this novel chemical chaperone on ALS treatment.

1 Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease affecting the physiology of motor neurons in the cerebral cortex as well as cervical and lumbar spinal cord (Tandan and Bradley 1985). This disorder can either appear sporadically (sALS) (∼90 % of the cases) or be inherited (fALS) (5–10 % of the cases) (Belleroche et al. 1995). Thirty years ago, R.H. Brown Jr and co-workers identified multiple missense mutations on the superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1 gene associated with fALS (Rosen et al. 1993) and since then, a total of 166 SOD1 mutations have been linked with ALS (Andersen and Al-Chalabi 2011). Currently, no cure is available for ALS disease. The FDA-approved pharmacological treatment via riluzole can increase the median survival time up to 19 months (Hinchcliffe and Smith 2017).

A hallmark of SOD1 ALS-related pathology is the formation of SOD1 inclusions/aggregates in neurons of both fALS (Kato et al. 2000; Ohi et al. 2004) and sALS (Forsberg et al. 2010) patients. These inclusions tested positive for unfolded/misfolded SOD1 with antibodies that recognize specific buried epitopes or misfolded species (Bosco et al. 2010; Forsberg et al. 2010; Paré et al. 2018). SOD1 mutations and consequent structural changes are qualified into two groups (Trist et al. 2021): 1) metal binding region (MBR) mutants, which are unable to bind the Zn2+ and Cu2+, presenting reduced enzymatic activity and significant lack of holo-SOD1 stability (Culik et al. 2018; Das et al. 2023) or 2) the wild-type-like (WTL) mutants, which are still able to bind to metal ions but present a significant destabilization of the apoSOD1 (Lindberg et al. 2005; Vassall et al. 2011). In fact, loss of apoSOD1 monomer stability induced by ALS-related uncharged mutations was found to correlate linearly with survival time in vitro (Lindberg et al. 2005). Moreover, in vitro (Furukawa and O’Halloran 2005; Vassall et al. 2011) and in-cell (Samanta et al. 2021) studies report on a link between increased aggregation propensity and lower apoSOD1 folding stability. Also, increased aggregation kinetics and disease progression in transgenic mice was shown to linearly correlate with increased tissue concentration of unfolded SOD1 (Lang et al. 2015).

Albeit initially thought to be related with a loss of dismutase function (Saccon et al. 2013), ALS-SOD1 neuronal toxicity has been strongly linked with a “gain-of-function” mechanism, whereby the soluble unfolded/misfolded/oligomeric mutant protein is responsible for dysregulation of various cellular processes including induction of ER stress, mitochondria dysfunction and impairment of lysosome homeostasis (Bicchi et al. 2021; Deng et al. 2006; Magrané et al. 2009; Nishitoh et al. 2008; Sangwan et al. 2017). ER-stress is triggered by age-dependent accumulation of misfolded or oligomeric mutant SOD1 inside the ER-lumen, with consequent binding of those species to binding immunoglobin protein (BiP) and so activating ER unfolded protein response (UPR) (Kikuchi et al. 2006). Mitochondrial damage was found to be associated with oligomerization of mutant SOD1 inside mitochondria (Cozzolino et al. 2009). Lysosome enzyme dysfunction was recently related with internal storage of mutant SOD1 (Bicchi et al. 2021) and previous studies reported partial colocalization of these compartments with SOD1 inclusions containing non-native protein (Forsberg et al. 2010). Misfolded mutant SOD1 was also shown to convert the wt form into misfolded species via direct protein-protein interactions (Grad et al. 2011), thus allowing the propagation of SOD1 dysfunction intercellularly in a prion-like fashion (Ekhtiari Bidhendi et al. 2018; Grad et al. 2014).

Different therapeutic strategies have been developed to reduce cellular toxicity associated with SOD1 aggregation, including upregulation of molecular chaperones (Brotherton et al. 2013; Bruening et al. 1999; Novoselov et al. 2013) and drug treatment based on artificial chemical chaperones (Getter et al. 2015), small molecules (Malik et al. 2019; Pokrishevsky et al. 2018; Samanta et al. 2022) or specific chemical inhibitors of SOD1 self-assembly (Woo et al. 2021). Chemical chaperones are small molecules that act non-specifically to correct trafficking of mislocalized proteins, to prevent detrimental interactions with cellular-resident proteins and to promote increased native state stability and reduced protein aggregation (Perlmutter 2002). These molecules include natural occurring osmolytes, such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) or hydrophobic compounds, such as 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA) (Cortez and Sim 2014). For osmolytes, the established mechanism of action suggests a stabilization of the folded conformation by a preferential hydration mechanism, where these molecules are excluded from the protein surface via unfavorable interactions with the residues composing that surface (Bhat and Timasheff 1992; Guinn et al. 2011; Senske et al. 2014; Street et al. 2006). For hydrophobic compounds, potential toxic intermolecular contacts are hindered by favorable interactions between the chemical chaperone and the hydrophobic exposed residues in unfolded/misfolded species (Cortez and Sim 2014; Kitakaze et al. 2019).

The main drawback associated with chemical chaperone-based therapies is the very high dosage required for the desired therapeutic effects: for example, active concentrations of TMAO in cells ranges from 1 to 100 mM (Bai et al. 1998; Getter et al. 2015) while PBA shows chaperone-like effects at 2.5 mM (Zhou et al. 2021). In our previous studies, we found that by targeting derivatives of TMAO (compound 14 (C14)) (Getter et al. 2015) and PBA (compounds 4 and 9 (C4 and C9)) (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021) to lysosome and ER, the active concentration was reduced to tens of µM in cell cultures and flies. Our working hypothesis is based on tagging chemical chaperones to intracellular compartments where the extra load of unfolded/misfolded SOD1 was shown to cause dysfunction. By doing it so, we expect to revert at a significant extend the damage cause by SOD1 mislocalization/aggregation. Indeed, C14 reduced mutant SOD1 aggregated species under ER-stressed conditions as well as decreased the levels of ER-stress markers BiP and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and misfolded SOD1 (Getter et al. 2015). C4, albeit having no effect on disease progression and survival of SOD1-ALS mice (Alfahel et al. 2022), was shown to revert eye degeneration in ALS Drosophila model expressing C9orf72 4G2C-haxanucleotide repeat expansion (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021).

Here, we synthesized 12 chemical chaperones derivatives of PBA and osmolyte sarcosine and first tested the effect of five chemical chaperones targeted to the ER and mitochondria on SOD1 folding stability inside cells and in vitro. We also tested the effect of four previously synthetized chemical chaperones tagged to the lysosome (C4) and ER (C8, C9 and C11) (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). We used a truncated version of SOD1 (SOD1bar), where loops IV and VII were replaced by Gly–Ala–Gly linkers, leaving the protein unable to dimerize and thermodynamically more stable than apoSOD1 (Danielsson et al. 2011). Mutations A4V and G41D were chosen to evaluate the chemical chaperones’ action given their high ratio of unfolded to folded protein inside cells at 37 °C (310 K) as well as a their reversible two-state unfolding, with low aggregation propensity (Gnutt et al. 2019b). The two mutants were targeted to the ER, mitochondria and lysosome in order to test the chaperone effect of the respective tagged-compounds on local folding stability. Moreover, we examined if the tags affected the mode of action of the lead chemical chaperones in vitro by applying an established thermodynamic model successfully used to dissect the molecular mechanism of any cosolute (e.g. osmolytes) on protein folding stability (Senske et al. 2016, 2014). We further inspected if the recognized modes of actions were preserved inside cells for the active targeted-chemical chaperones.

2 Results

2.1 Synthesis of 4-PBA and sarcosine derivatives-targeted for ER, mitochondria and lysosome

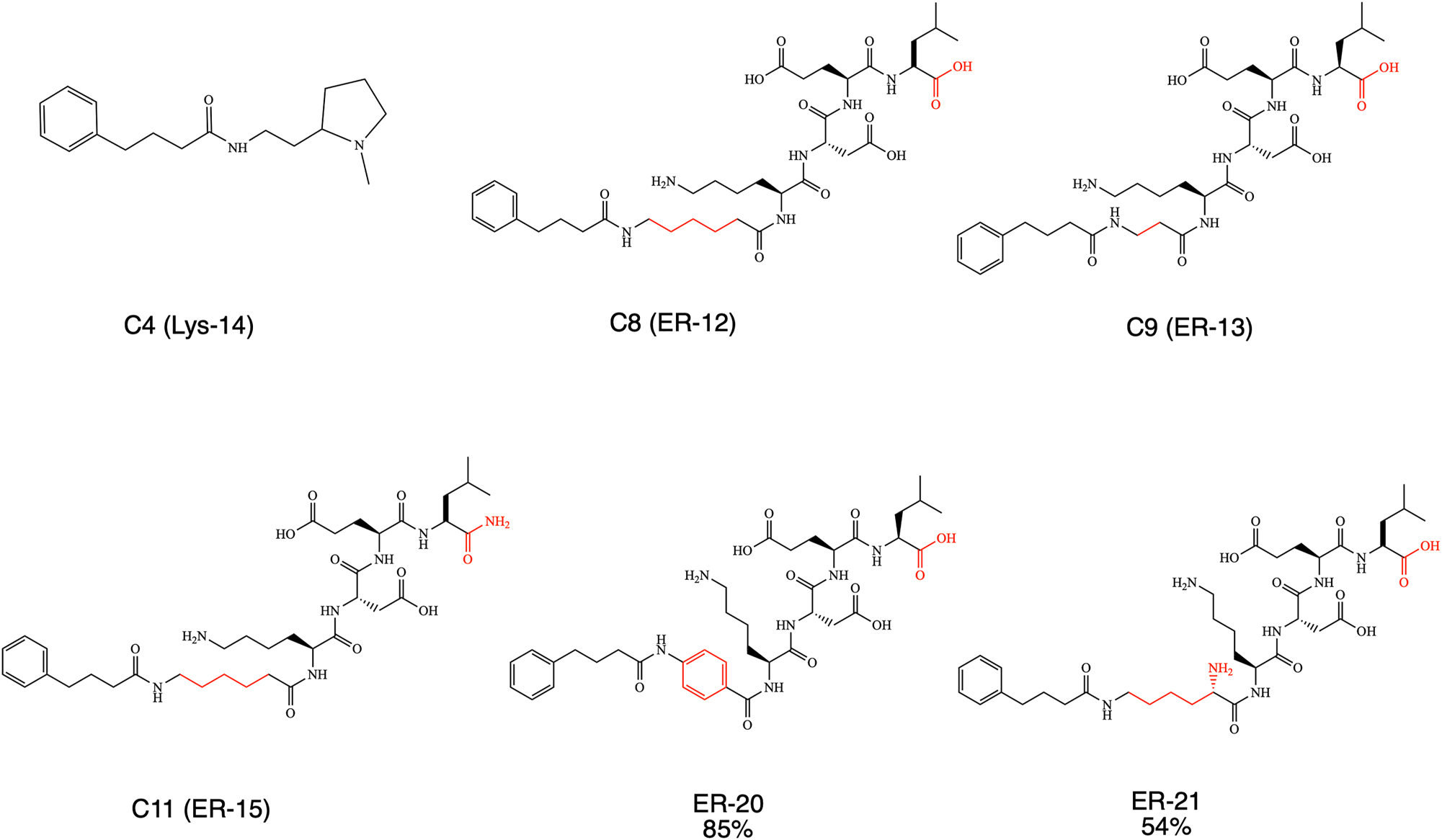

Compounds with the ability to target three different cellular compartments (lysosome -or ER -or mitochondria) were tested in this work. Each synthesized molecule contains chaperones (PBA or Sarcosine), the targeting moiety: to lysosome -or ER -or mitochondria and a linker. The C4 compound (Lys-14), which is examined in this work, contains PBA chaperone targeted to the lysosome, and its synthesis was already described previously (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). Also, the structures and synthesis of three ER-targeted compounds, C8, C9, and C11 (ER-12, ER-13 and ER-15 respectively), were already disclosed in the same manuscript (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). The structures of these four compounds are shown in Scheme 1.

PBA derivatives with lysosome and ER-targeted domains.

Two more novel ER-targeted compounds were designed and synthesized based on Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu (KDEL) peptide (Cela et al. 2022). Compounds ER-20 and ER-21 were prepared by using solid phase peptide syntheses (SPPS) strategy. A 4-hydroxymethylbenzoic acid aminomethyl polystyrene (HMBA-AM) was used as a solid state support resin (Scheme 1). In this case, the carboxylic acid moiety in the C-terminal part of the peptide remains intact. The difference between the synthesized ER-compounds was only the type of linker used in each case. In compound ER-20, the linker was a rigid one – an aromatic ring, that was introduced to the molecule by using the commercially available 4-aminobenzoic acid. For the linker in compound ER-21, a commercially available lysine was used. Linkers in ER-12, ER-13 and ER-15, were alkyls with different amounts of methylene moieties.

In addition, 10 compounds were designed and synthesized using a triphenylphosphonium moiety (TPP) that targets mitochondria (Zielonka et al. 2017). PBA was used as a chemical chaperone moiety for the synthesis of six compounds, and sarcosine was used as a chemical chaperone for the synthesis of the other four compounds. The compounds were divided into three groups; a) PBA chaperone with an alkyl linker (three, five, and six methylenes) b) PBA chaperone with an aromatic linker; and c) sarcosine chaperone with an alkyl linkers assembly similarly to the first group. All 10 compounds were synthesized with a bond between the chaperone and the TPP that is degradable under physiological conditions.

The general synthetic route contains three steps: 1) coupling between activated carboxylic acid and amine or alcohol using TBTU. These intermediate compounds contain another alcohol moiety in the end; 2) the alcohol group was replaced by a better leaving group such as mesylate group; 3) TPP was coupled to the molecule via SN2 substitution.

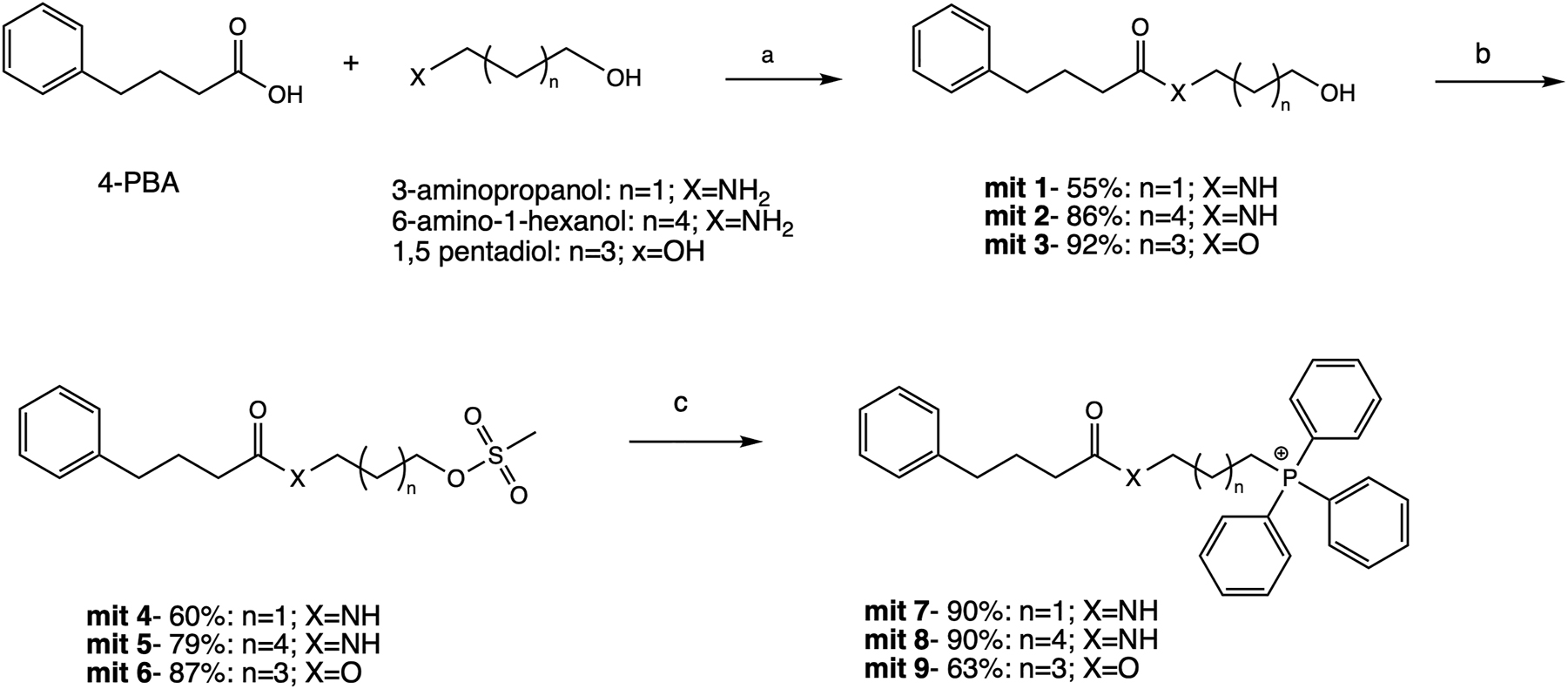

First, the mit-7, mit-8 and mit-9 containing three, six and five methylenes (respectively) as a linker and belonging to the first mitochondria-targeted compounds group were synthesized (Figure 1). The compound mit-1 was obtained in 55 % yield by coupling PBA with the commercially available 3-aminopropanol using TBTU as coupling reagent. The commercially available starting molecules 6-amino-1-hexanol and 1,5-pentadiol were used to obtain mit-2 at 86 % yield and mit-3 at 92 % yield, respectively. During the next step, mit-1-3 were treated with methanesulfonyl chloride (MsCl) in the presence of TEA to obtain the mesylate-based derivatives mit-4, mit-5 and mit-6 at 60, 79, and 87 % yield respectively. The nucleophilic attack of TPP on the corresponding methanesulfonate was initiated by performing the procedure previously reported (Jameson et al. 2015). Mit-4-6 were reacted with TPP at reflux for 24 h resulting in compounds mit-7, mit-8 and mit-9 with 90, 90 and 63 % yield respectively (Figure 1). During mit-9 synthesis reaction, sodium iodide was added (NaI) as a potentiator of the SN2 substitution. Thus, the counter ion in the final TPP-based chaperone, mit-9, was supposed to be iodide, but this was not confirmed.

Synthesis pathway of mit-7, 8 and 9. Reagents and conditions: (a) TBTU, TEA, EtOAc, rt, 12 h; (b) MsCl, TEA, dry DCM, rt, 1 h; (c) TPP, NaI (for mit-9 formation), acetonitrile, reflux, 24 h.

The second group of PBA mitochondria-targeted compounds contained an aromatic linker. The synthesis of mit-16, mit-17, and mit-18 started from 3-aminobenzyl alcohol, 4-aminobenzyl alcohol, and 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol respectively, following the identical synthetic pathway that was used for the synthesis of mit-7, mit-8, and mit 9 (Figure 2). Mit-10 and mit-11 were amide derivatives, while mit-12 had an ester bond. In the next step of synthesis (mit-13, mit-10), the mesylation was conducted in a good yield (90 %). In addition, mit-14 was obtained from mit-11 by introducing a chloride atom as a leaving group (the source was a chlorine atom from the solvent, dichloromethane), instead of a mesylate. We were forced to conduct such change because mesylation was not fully successful in this case. Mit-15 was obtained starting from mit-12 as a mixture of a mesylate and a chloride containing molecules. Both compounds reacted with TPP at reflux, and resulted final mit-16, mit-17, and mit-18 compounds as corresponded phosphonium salts at good yields (86, 82, and 70 % respectively).

Synthetic pathway for the preparation of mit-16, 17, and 18. Reagents and conditions: (a) TBTU, TEA, EtOAc, rt, 12 h; (b) MsCl, TEA, dry DCM, rt, 1 h; (c) TPP, NaI, acetonitrile, reflux, 24 h.

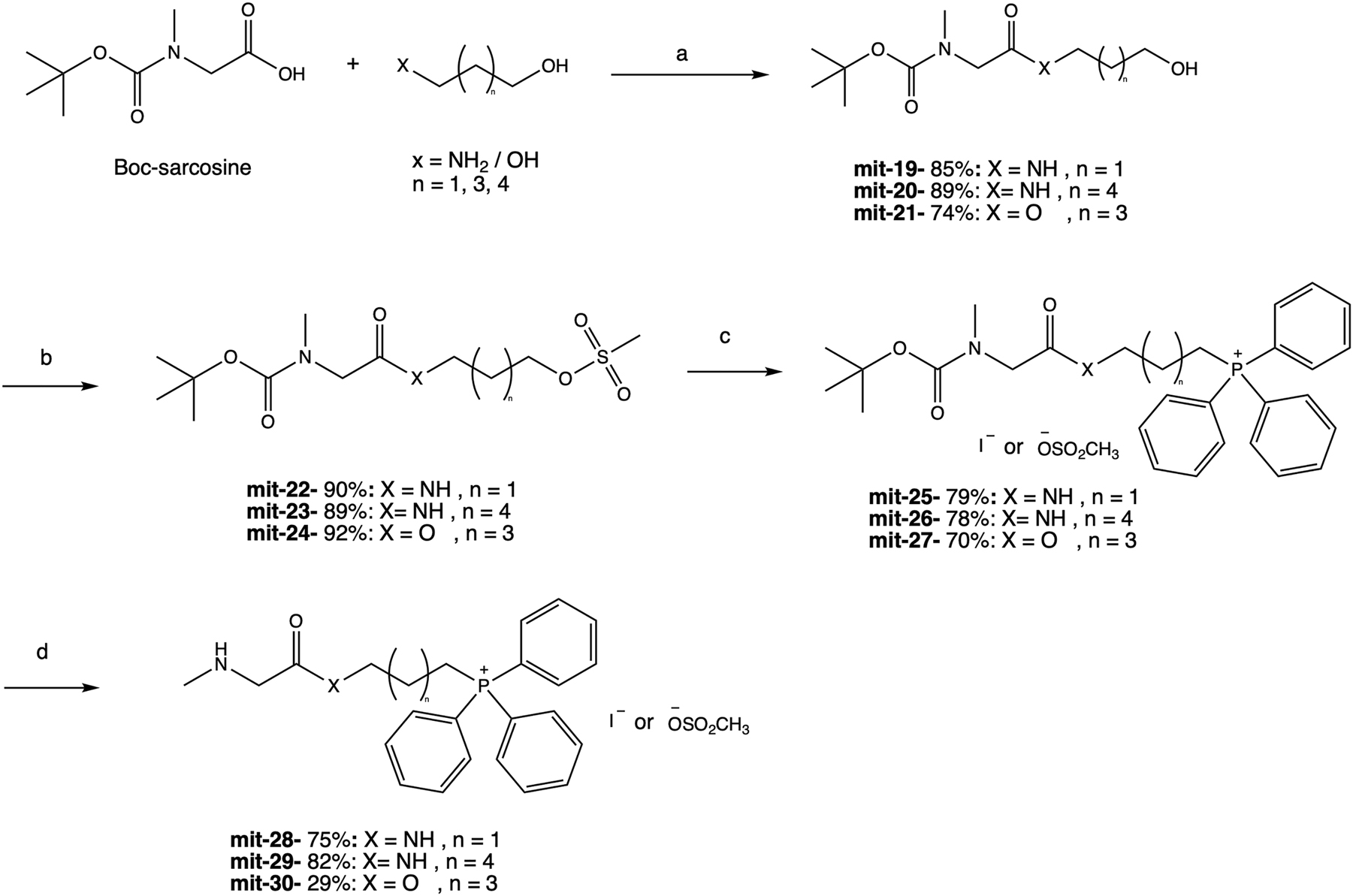

In the third group (mit-28, mit-29, and mit-30), sarcosine was used as chemical chaperone, and the alkyl linkers connected it to TPP. To prepare these mitochondria-targeted derivatives, a commercially available Boc-sarcosine known also as Boc-N-methylglycine was used. Therefore, a fourth step was introduced to the synthetic pathway, in which the amine moiety’s deprotection in the final product was conducted (Figure 3). All final compounds were obtained at good yield using 3-amino-1-propanol, 6-amino-1-propanol, and 1,5-pentadiol as linkers respectively. Mit-19 and mit-20 contained an amine bond, and mit-21 had an ester bond. The corresponding alcohols were mesylated using MsCl with TEA to obtain mit-22, mit-23, and mit-24 in high yields.

Synthetic pathway for the preparation of mit-28, 29, and 30. Reagents and conditions: (a) TBTU, TEA, EtOAc, rt, 12 h; (b) MsCl, TEA, dry DCM, rt, 1 h; (c) TPP, NaI, acetonitrile, reflux, 24 h; (d) TFA, rt, 1 h.

The Boc group’s deprotection was conducted using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to allow the final compounds: mit-28, mit-29, and mit-30. The synthetic yield of mit-30 was relatively low (29 %) because of unwanted ester bond hydrolysis under acidic conditions. Supplementary Figure 1 shows 13C NMR spectra in comparing the isolated compound mit-30 (red line) and the mixture of mit-30 with the impurity (blue line). Peaks at 61.5, 31.2, and 27.0 (d, J = 17 Hz), 22.2 (d, J = 4 Hz), and 22.14 (d, J = 50 Hz) in the blue spectrum belong to the major impurity: 5-(hydroxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium. Although we tried to improve the conditions for the synthesis of this specific compound, the yield was not improved.

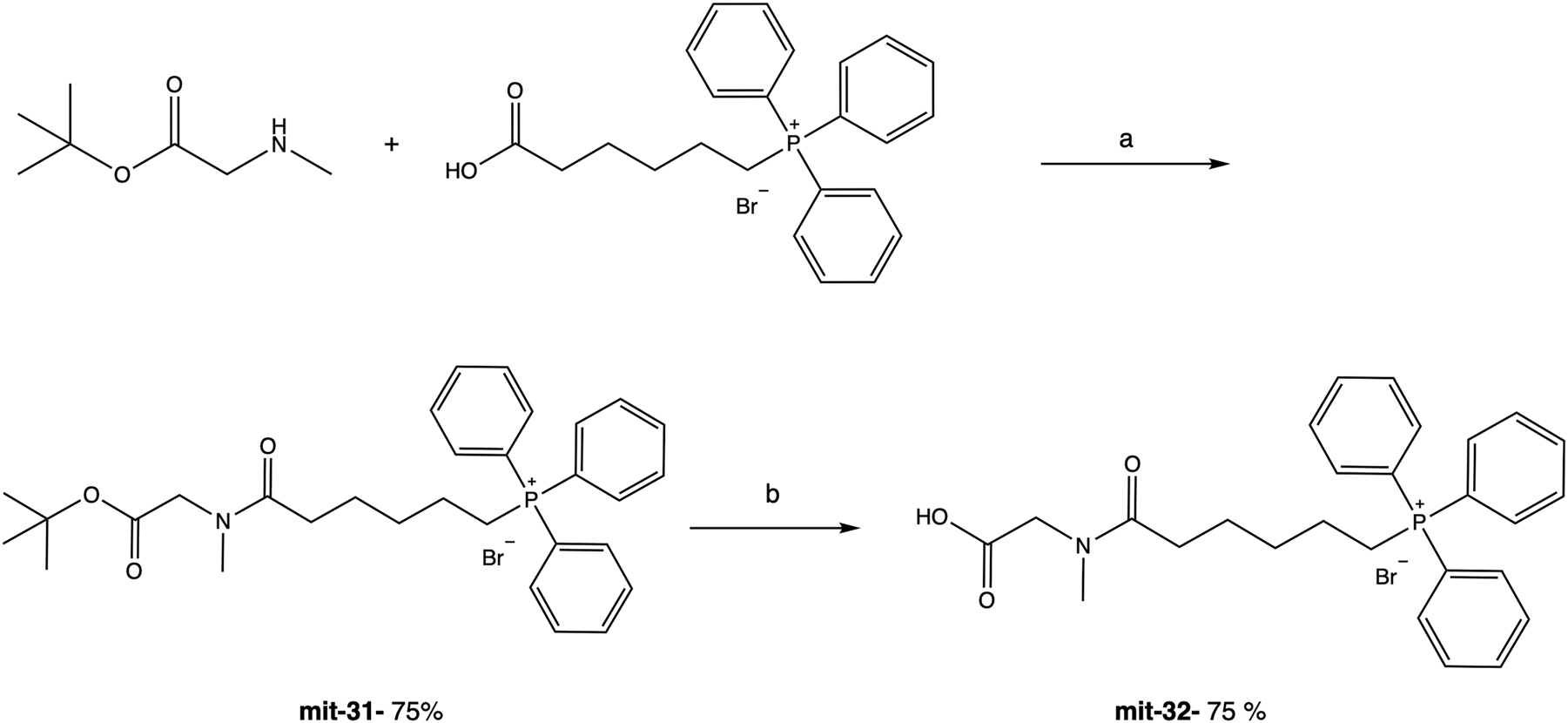

In the preparation of the last compound, sarcosine was connected to the TPP through the amine and not the carboxylic acid moiety (Figure 4). For that reason, commercial available sarcosine tert-butyl ester was used as a starting material, which was reacted with 5-carboxypentyltriphenylphosphonium bromide. A benzotriazol-1-yl-oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP) was used as a coupling reagent (Kolevzon et al. 2011). Under these conditions, mit-31 was obtained in 75 % yield. The next step was to remove the tert-butyl group from the carboxyl, using TFA. At the end of the reaction, final compound mit-32 was obtained in 75 % yield.

Synthesis pathway of mit-32. Reagents and conditions: (a) PyBOP, DIEA, DCM, rt, 4 h; (b) TFA, rt, 1 h.

2.2 In-cell folding stability of SOD1bar-targeted for ER and mitochondria

To design local probes for the chaperone effects, we fused SOD1bar-A4V and -G41D mutations (Figure 5A) to three different tags: 1) KDEL + calreticulin (ER-resident protein) sequences, 2) mitochondrial targeting sequence from subunit 8 of human cytochrome c oxidase (Olenych et al. 2007) and 3) human myeloperoxidase (lysosomal protein) (see material and methods for details). Our previous study showed that non-tagged SOD1bar is mostly expressed in the cytosol (Gnutt et al. 2019b). To verify the proper location of the different SOD1bar variants in the respective intracellular compartments, we imaged simultaneously cells expressing ER-SOD1bar-A4V or mitochondria/lysosome-SOD1bar-G41D and the respective organelle dyes (Supplementary Figure 2). Colocalization was confirmed for ER and mitochondria-SOD1bar mutants (Pearson r of 0.65 and 0.72, respectively). Albeit lysosome-SOD1bar-G41D partially overlapped with lyso-Tracker, expression was spread over additional intracellular locations and so no further analyses were conducted with this variant. No significant variations on SOD1bar folding stability are expected due to the presence of different tags as previously observed for ER- and nuclear-tagged PGK and VslE (Dhar et al. 2011; Tai et al. 2016).

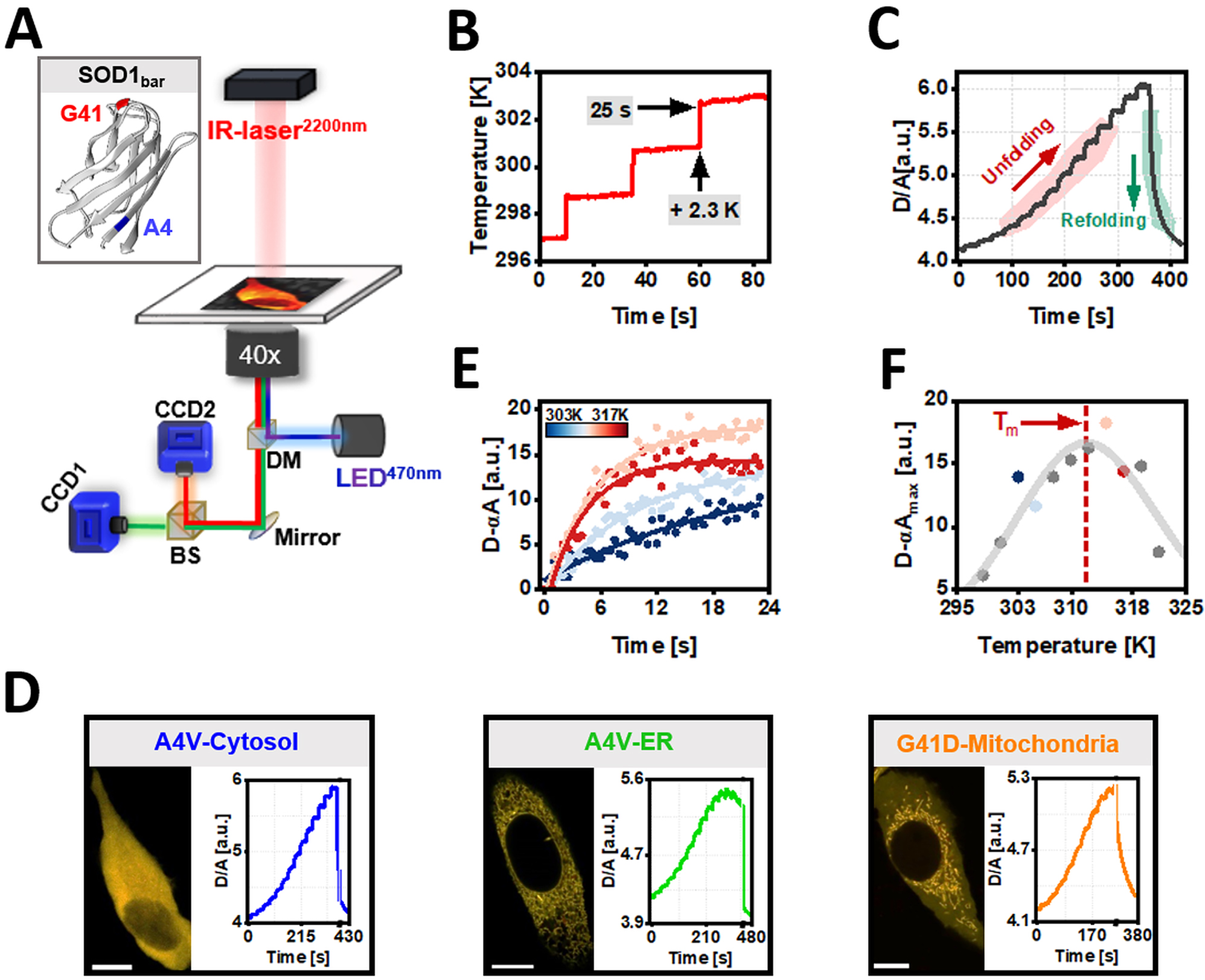

Quantification of in vitro and in-cell organelle-folding stability of SOD1bar-A4V/G41D using FReI. (a) Fast relaxation imaging (FReI) technique customized in an inverted widefield microscope (adapted from (Samanta et al. 2021)). Inset shows the 3D structure of SOD1bar as well as the sequence location of the two mutations studied in this work (PDB: 4BCZ). (b) Temperature profile used in our FReI measurements. (c) Thermal unfolding curves monitored by FRET ratio (D/A) changes with time for SOD1bar-A4V expressed in the cytosol. (d) Representative confocal images of HeLa cells expressing cytosolic or ER-targeted SOD1bar-A4V as well as SOD1bar-G41D tagged to the mitochondria (scale bar = 20 μm). Also, exemplary FReI thermal unfolding curves measured in the widefield setup presented in (a) for each construct. (e) Exemplary kinetic unfolding amplitudes (D-αA) for a set of four different temperatures, selected from plot (c). Solid lines present fits to a single exponential model (equation (2)). (f) Steady-state unfolding amplitudes plotted as a function of temperature. The solid line was computed by fitting the data to a two-state folding model (equation (3)).

We quantified the in-cell folding stability of A4V and G41D tagged-constructs using Fast Relaxation Imaging (FReI) technique (Figure 5A). FReI allows to measure the thermal unfolding of FRET-labelled biomolecules via fast-temperature (T) jumps (millisecond (ms) range), induced by a mid-infrared (IR) laser (2200 nm) attached into a widefield microscope (Ebbinghaus et al. 2010). SOD1bar-A4V/G41D were labelled with AcGFP1 in N-terminus and mCherry in the C-terminus. HeLa cells transiently expressing SOD1bar mutants or the corresponding in vitro purified constructs were subjected to 14–16 consecutive T jumps of ∼2.3 K and 25 s each (Figure 5B), followed by a 60 s period where no laser pulse was applied. This latter step promoted refolding of SOD1bar at RT (Figure 5C). Donor (D, AcGFP1) and acceptor (A, mCherry) fluorescence emissions were recorded into two separated channels by associated CCD cameras (Figure 5A). FRET ratio (D/A) curves as a function of time were recorded, with cooperative unfolding transitions featuring serial increased D/A values (Figure 5C). Exemplary D/A thermal unfolding curves with time for the mutants targeted to various subcellular compartments are shown in Figure 5D. The FRET signal of each T jump was further scaled as D − αA (α = D

0/A

0 at t = 0 s) and fitted to a single exponential model (D(t) − αA(t) = A

0+(A

2 − A

0)·(1 − exp−k·t

)) to determine the steady-state unfolding amplitudes (A

2 or D − αA

max) at different temperatures (Figure 5E). These D − αA

max values were then plotted as a function of temperature and fitted with a two-state folding model (Girdhar et al. 2011) in order to compute melting points (T

m

) and cooperative parameters (g

(1)) (Figure 5F). Modified standard-state free energies of folding (ΔG

0′

f

) at 310 K (37 °C) were determined via

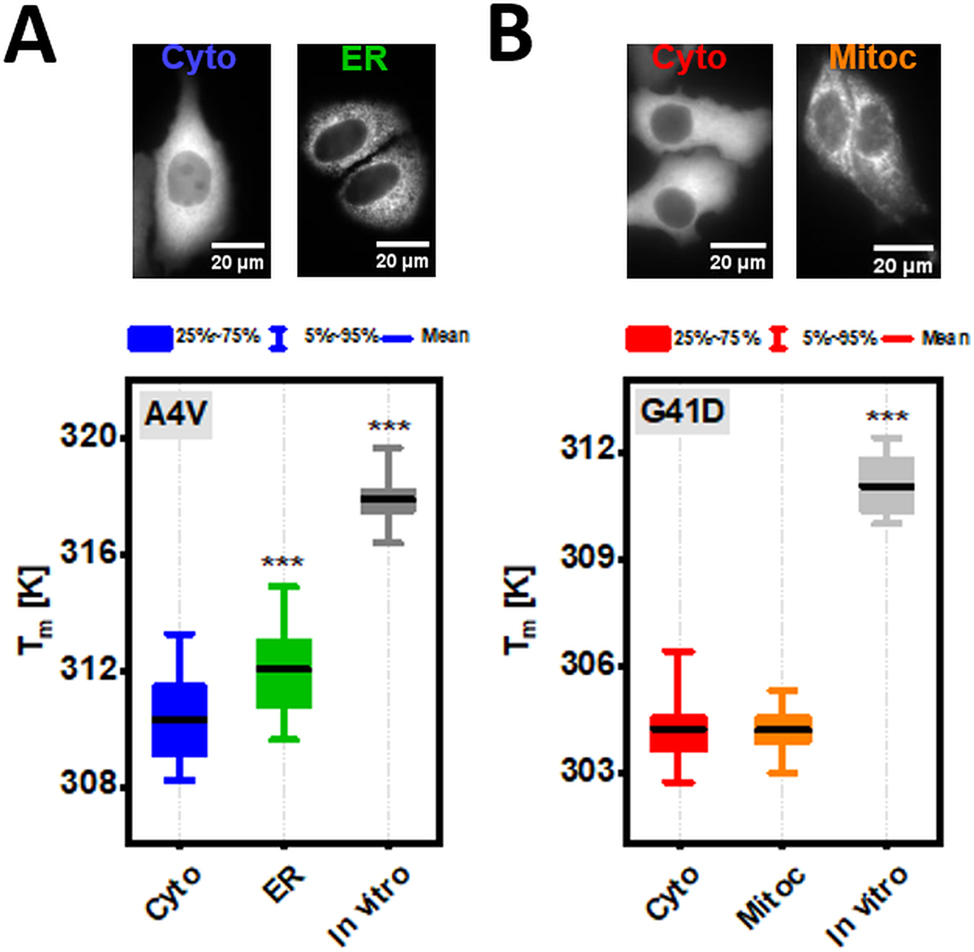

In-cell and in vitro folding stabilities for cyto and ER-SOD1bar-A4V or cyto and mitoc-SOD1bar-G41D are shown in Figure 6A and B (T m ) as well as in Supplementary Figure 3 (ΔG 0′ f (310 K)). SOD1bar-A4V was significantly more stable in the ER (T m is ∼1.8 K higher) when compared to the cytosol (Figure 6A), in accordance with the previous reports showing increased stability of PGK (T m is ∼1.3 K higher) (Dhar et al. 2011) and VlsE (T m is ∼3 K higher) (Tai et al. 2016) when tagged to the ER versus cytosol. One possible contribution for the observed increased PGK/VlsE stability banked on electrostatic interactions among the negatively charged surface of both proteins and the high concentration of ER-Ca2+ (Tai et al. 2016). To test this hypothesis, we measured the in vitro folding stability of SOD1bar-A4V in the presence of 800 μM of Ca2+, values near to the upper limit known for [Ca2+] inside the ER (Carreras-Sureda et al. 2018). We observed a small increase in the folding stability (T m is ∼0.9 K higher) of the mutant when supplemented with Ca2+, albeit not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure 4). This result suggests that the existent high [Ca2+] in the ER does not fully recapitulates the stabilization observed for SOD1bar-A4V therein. Interestingly, previous all-atom simulation studies have shown that crowded protein solutions are prone to cluster in the presence of membranes due to protein-exclusion from the membrane surface (Nawrocki et al. 2019). Parallel to this increased propensity for aggregation was the small increase in the native state compaction as a result of larger excluded volume effects in the bulk (Nawrocki et al. 2019). Given that the ER lumen is engulfed by membranes, it is likely that additional stabilizing contributions to SOD1bar-A4V folding may arise from protein-depletion at the membrane surface. In order words, the resulting larger excluded volume inside the ER lumen may promote additional stabilization of the protein (Gnutt and Ebbinghaus 2016). SOD1bar-G41D tagged to the mitochondria showed no stability change (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure 3B).

Folding stability of SOD1bar-A4V/G41D in diluted solution as well as inside the different subcellular compartments. (a) Representative widefield images of HeLa cells transiently expressing cytosol (Cyto) and ER-tagged SOD1bar-A4V. Bar plot presents the different melting points (T m ) for the corresponding variants as well as for the purified construct in diluted buffer solution (in vitro). (b) Typical widefield images of HeLa cells transiently expressing Cyto and mitochondria (Mitoc)-tagged SOD1bar-G41D. Bar plot presents the different melting points (T m ) for the matching variants as well as for the purified protein in vitro. Statistical significances were computed by GraphPad Prism V. 8.0 using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett-test with a confidence interval of 95 % (***p ≤ 0.001). Statistical comparisons were made in respect to each cytosolic variant.

The folding stability of the two mutants in vitro was significantly higher than any of the investigated subcellular locations (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 3), previously attributed to destabilizing attractive chemical interactions with different cellular constituents (Gnutt et al. 2019b).

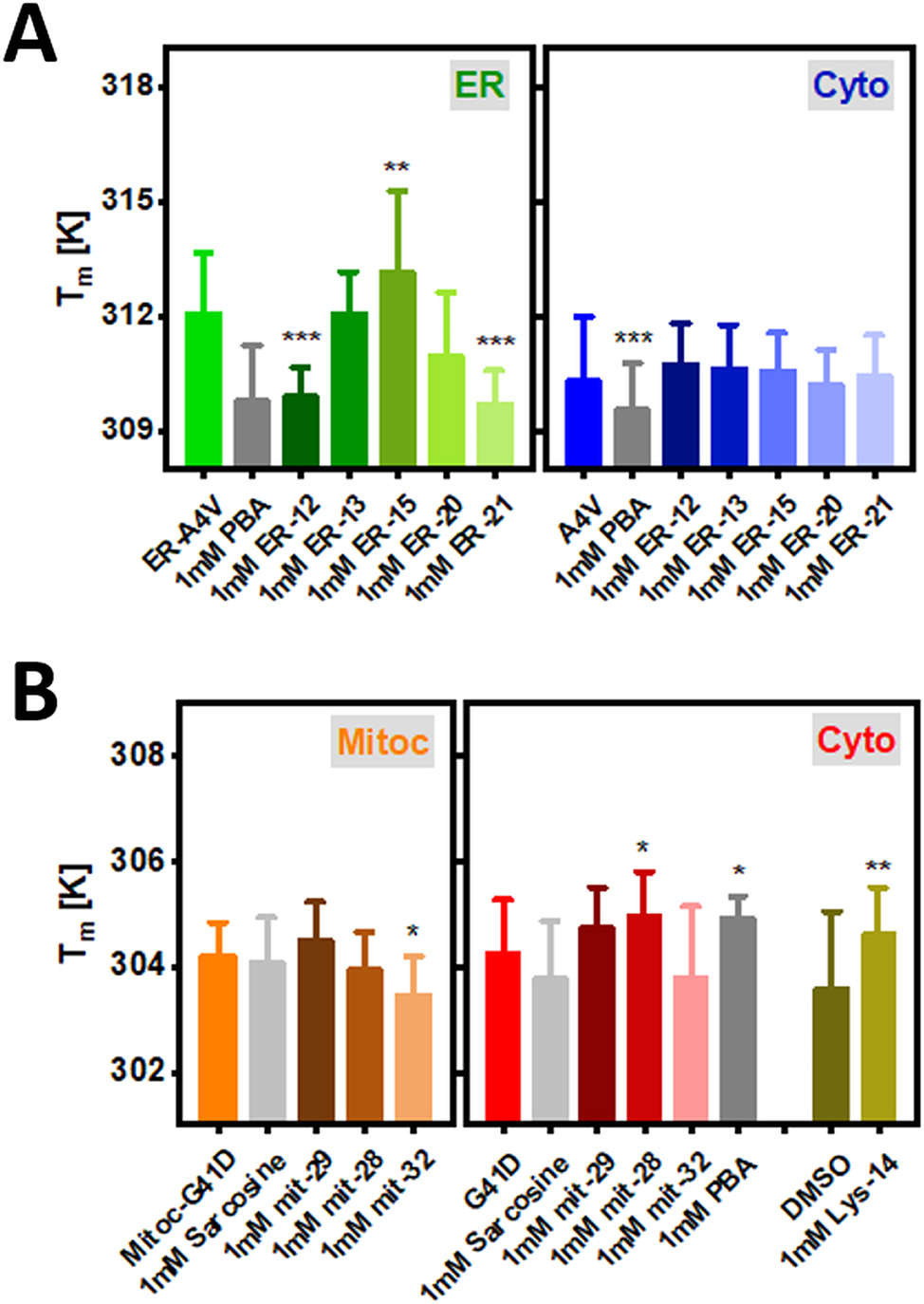

2.3 Novel ER, mitochondria and lysosome-localized chemical chaperones increase in-cell folding stability of SOD1bar mutations

In order to analyze how the various derivatives of PBA and sarcosine subcellular-targeted affect the folding stability of the respective tagged-SOD1bar-A4V/G41D, HeLa cells transiently expressing the proteins (∼18 h) were supplied with 1 mM of each drug ∼24 h prior to the measurements. Controls with cytosolic SOD1bar-A4V and -G41D supplemented with the same compounds for ∼24 h were also conducted. The results are summarized in Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 5. PBA derivatives ER-12 and ER-21 significantly destabilized ER-SOD1bar-A4V (↓ T m ) (Figure 7A) (↑ ΔG f 0′ (310 K)) (Supplementary Figure 5A), a trend followed by the lead compound PBA. On the opposite side, ER-15 significantly increased T m by ∼1.1 K (Figure 7A) and decreased ΔG f 0′ (310 K) by 0.24 kJ mol−1 (Supplementary Figure 5A). None of the ER-targeted drugs changed the folding stability of cytosolic A4V while PBA destabilized it significantly (↓ T m ) (Figure 7A) (↑ ΔG f 0′ (310 K)) (Supplementary Figure 5A). Sarcosine and its-derivate compounds tagged to mitochondria showed no effect on mitoc-SOD1bar-G41D albeit drug mit-32, whose action resulted in a less stable protein (Figure 7B and Supplementary Figure 5B). On G41D cytosolic counterpart, the chemical chaperones also exhibited no significant effect on folding stability. The only exception was mit-28 which increased T m by ∼0.7 K (Figure 7B) and lowered ΔG f 0′ (310 K) by ∼1 kJ mol−1 (Supplementary Figure 5B). PBA-derivative Lys-14-targeted to the lysosome increased folding stability of cytosolic-SOD1bar-G41D (T m ↑ ∼1.0 K, Figure 7B) (ΔG f 0′ (310 K) ↓ 0.96 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Figure 5B). PBA itself also promoted a significant increase of cyto-SOD1bar-G41D stability, albeit the magnitude of such effect was approximately half of that one from Lys-14 (T m ↑ ∼0.7 K, Figure 7B) (ΔG f 0′ (310 K) ↓ 0.5 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Figure 5B).

Bar plots showing T m for the subcellular tagged ER-SOD1bar-A4V (a) and Mitoc-SOD1bar-G41D (b) as well as their cytosolic counterparts in control conditions (physiological or DMSO) or supplied with 1 mM of ER-, mitoc- and lyso-targeted PBA or sarcosine derivatives for 24 h. Statistical significances were computed by GraphPad Prism V. 8.0 using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett-test with a confidence interval of 95 % (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001). Statistical comparisons refer to each drug condition and the respective control.

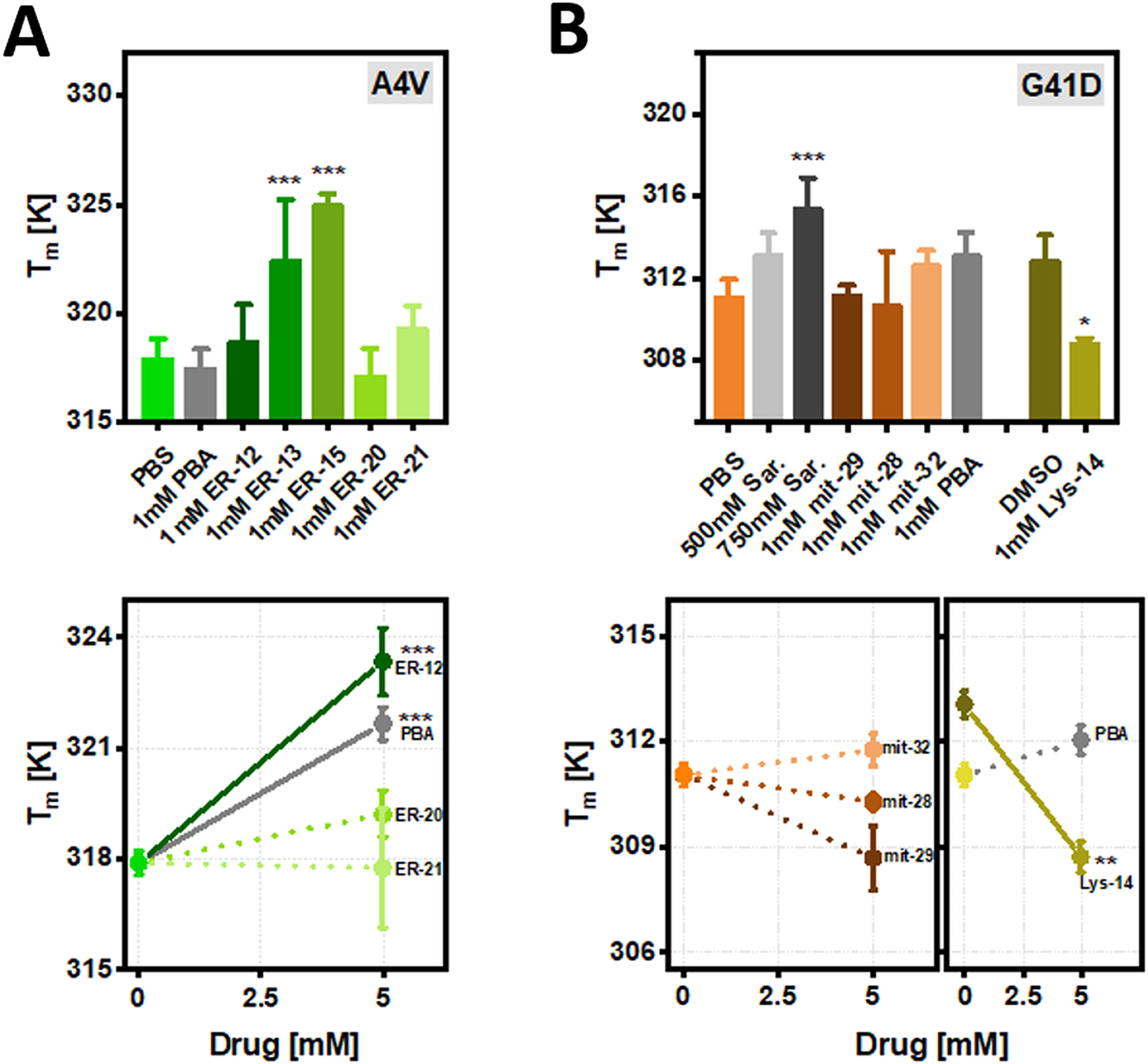

We next investigated the effect of the various artificial chemical chaperones on SOD1bar mutant folding stability in a cell-free environment, in order to scan for the presence of direct drug-protein interactions. Ten micromolar of purified untagged SOD1bar-A4V and -G41D dissolved in phosphate buffer (PBS, pH 7.4) were incubated with 1 and 5 mM of the various drugs for 30 min at RT, prior to the FReI measurements. ER-13 and ER-15 significantly stabilized SOD1bar-A4V folding at 1 mM, increasing the T m by ∼4.5 and 7.1 K (Figure 8A) and decreasing ΔG f 0′ (310 K) by ∼0.4 and 0.9 kJ mol−1, respectively (Supplementary Figure 6A). PBA and ER-12 required a 5-fold excess to produce similar enhancements on folding stability while no significant effect was observed for 5 mM ER-20 and ER-21 (Figure 8A). None of the mit-28, 29 or 32 compounds led to significant changes on SOD1bar-G41D stability at both 1 and 5 mM concentrations (Figure 8B). In fact, the active concentration of lead compound sarcosine on stabilizing SOD1bar-G41D was significantly higher (750 mM) (Figure 8B and Supplementary Figure 6B) than those reported for other natural osmolytes such as glycine betaine, which required only 1 mM for rescuing folding stability of 7 kDa N-terminal SH3 domain inside osmotic-stressed bacteria cells (Stadmiller et al. 2017). Such levels are well-beyond any therapeutic dosage, indicating that sarcosine-derivatives might not be ideal candidates for treatment of ALS-linked SOD1-mutant instability and aggregation. Lastly, Lys-14 significantly destabilized SOD1bar-G41D at both 1 and 5 mM, while lead compound PBA had no significant effect on G41D folding stability at those same concentrations (Figure 8B and Supplementary Figure 6C).

T m for in vitro purified SOD1bar-A4V (a) and -G41D (b) in control conditions (PBS and DMSO) or supplied with 1 and 5 mM of ER-, mitoc- and lyso-targeted PBA or sarcosine derivatives for 30 min at RT. Statistical significances were computed by GraphPad Prism V. 8.0 using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett-test with a confidence interval of 95 % (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001). Statistical comparisons refer to each drug condition and the respective control.

2.4 Molecular mechanisms for the active intracellular targeted-chemical chaperones

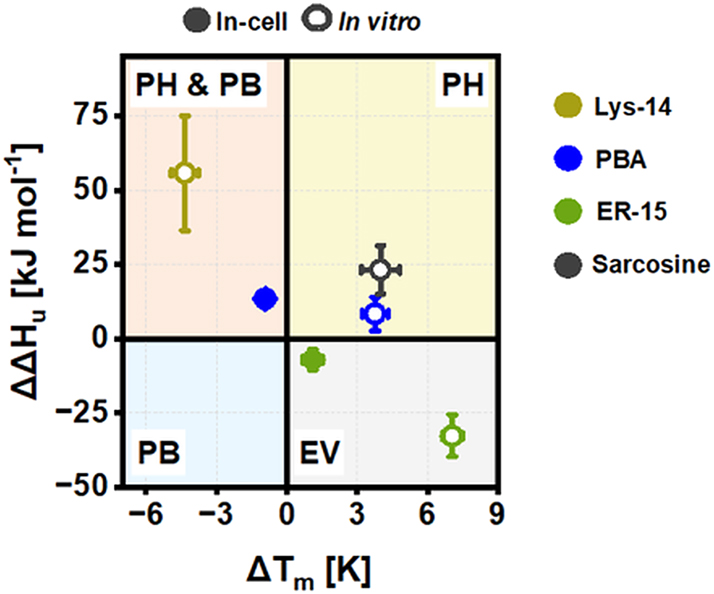

We next examined if the attached ER or lysosome tags alter the molecular mechanism by which PBA modulated the native stability of SOD1bar mutants. First, we inspected PBA and sarcosine osmolyte effect on SOD1bar-A4V/G41D folding stability in vitro, whose mechanisms of action have been previously established (Cortez and Sim 2014; Street et al. 2006). To dissect the molecular action of any cosolute, including chemical chaperones, on protein folding stability, we must consider how the cosolute changes not only the T m but also the enthalpic (ΔH u 0′) and entropic (ΔS u 0′) contributions comprising unfolding free energies, ΔG u 0′ (T) = ΔH u 0′ (T m ) − T · ΔS u 0′ (T m ) (recall ΔG u 0′ = −ΔG f 0′) (Senske et al. 2016, 2014). We started by computing the excess in unfolding enthalpies (ΔΔH u 0′ = ΔH u 0′ drug − ΔH u 0′ control) and melting points (ΔT m = T m drug − T m control) of SOD1bar-A4V and -G41D caused by the presence of PBA and sarcosine (respectively) in vitro (Figure 9). Both chemical chaperones stabilized the proteins (ΔT m > 0) as well as induced a positive excess on ΔH u 0′ (ΔΔH u 0′ > 0), albeit not significant for PBA (Supplementary Figure 7A and B). Positive excess in ΔH u 0′ is suggested to be the hallmark of preferential hydration (PH) mechanism (Politi and Harries 2010; Senske et al. 2014). Based on these results, sarcosine and PBA stabilize SOD1bar mutants due to exclusion of these molecules from the protein surface, consequently allowing water to solvate that surface. Indeed, such mechanism equals the one described for sarcosine and other protective osmolytes (Street et al. 2006). On the other hand, PBA mechanism of action rather relies on favorable hydrophobic interactions with unfolded proteins (Cortez and Sim 2014). The thermodynamic hallmarks of this behavior are either indicated by a destabilizing effect (ΔT m < 0) or a negative excess in ΔH u 0′ (ΔΔH u 0′ < 0) (Senske et al. 2014), both of which are not observed for PBA in our in vitro analyzes (Figure 9). This apparent conflict is, however, solved when we compute ΔΔH u 0′ and ΔT m for cyto-SOD1bar-A4V in the presence of PBA inside cells (Figure 9). We observed a destabilizing effect (ΔT m < 0), suggesting that, indeed, PBA can preferentially bind (PB) to unfolded SOD1bar-A4V. Surprisingly, we also observed a significant positive excess on ΔH u 0′ (ΔΔH u 0′ > 0) (Supplementary Figure 7A), reinforcing the earlier in vitro indication that this chemical chaperone can, likewise, induce preferential hydration of the protein surface. Such mode of action remains unreported for PBA.

Classification of tested chemical chaperones based on excess unfolding enthalpies (ΔΔH u 0′) and melting points (ΔT m ) for the drugs that induced an active (de)stabilizing effect on SOD1bar-A4V/G41D folding inside cells as well as in vitro. PH stands for preferential hydration, PB for preferential binding and EV for excluded volume. Concentrations shown are as follow: ER15in-cell/in vitro = 1 mM; Lys14 in vitro = 5 mM, Sarcosine in vitro = 750 mM, PBAin-cell = 1 mM and PBA in vitro = 5 mM.

Having dissected the mechanism of action for lead compound PBA, we next examined how lysosome and ER tags alter the action of this chemical chaperone. We started by computing ΔΔH u 0′ and ΔT m for SOD1bar-G41D in the presence of Lys-14 in vitro (Figure 9). We observed a significant destabilization (ΔT m < 0) of the protein as well as a positive excess on ΔH u 0′ (ΔΔH u 0′ > 0) (Supplementary Figure 7B), hallmarks of favorable drug-unfolded SOD1bar-G41D interactions and drug-induced preferential hydration of the protein, respectively. Given that PBA had no significant effect on SOD1bar-G41D stability in vitro (Figure 8B), such results suggest that the lysosome moiety attached on Lys-14 reduces the effective concentrations of PBA by magnifying its ability to act as an intermediate between destabilizing preferential binding and stabilizing preferential hydrating osmolyte (PB & PH, Figure 9).

Lastly, we computed ΔΔH u 0′ and ΔT m for SOD1bar-A4V in the presence of ER15 in vitro (Figure 9). This chemical chaperone induced a significant stabilization of the protein (ΔT m > 0), together with a significant negative excess on ΔH u 0′ (ΔΔH u 0′ < 0) (Supplementary Figure 7A). The latter is reported as another hallmark of preferential interactions between the drug and unfolded SOD1bar-A4V. At the same concentration (1 mM), lead compound PBA had no significant effect on SOD1bar-A4V stability in vitro (Figure 8A), suggesting that the ER-KDEL tag attached on ER-15, as for Lys-14, reduces the concentrations of PBA required for a drug effect. Nevertheless, interpretations on the molecular details by which this tag might change PBA mode of action are complex. The observed changes induced by ER15 on the thermodynamic parameters (ΔΔH u 0′ < 0 and ΔT m > 0) are generally interpreted as being fingerprints of a protein stabilization driven by excluded volume effects (Senske et al. 2014). Such mechanism of action was indeed reported previously for natural osmolytes (Baptista et al. 2008; Linhananta et al. 2011; Ratnaparkhi and Varadarajan 2001). Briefly, in addition to their ability of inducing preferential hydration on proteins, protective osmolytes can stabilize the native state indirectly by compacting the unfolded form hence reducing its conformational entropy (Baptista et al. 2008; Linhananta et al. 2011; Ratnaparkhi and Varadarajan 2001). Indeed, we observed a decrease in the unfolding entropy of SOD1bar-A4V in the presence of ER-15 (Supplementary Figure 7C), suggesting that such entropic mechanism can play a significant role in the mode of action of this chemical chaperone. We have also confirmed that ER-15 preserved this mechanism when stabilizing SOD1bar-A4V in the ER (Figure 9 and Supplementary Figure 7A–C). Together, these results suggest that KDEL tag modulates the mechanism of action of PBA in a way that the PBA-driven preferential interactions with the unfolded state are kept albeit with an entropic cost on the structure of this last.

3 Discussion

We synthetized 16 different chemical chaperones derivatives from lead compounds PBA and sarcosine tagged for the ER, mitochondria and lysosome. Our aim was to find candidates that increase compartment-specific folding stability and accordingly, reduce associated toxic aggregation of A4V and G41D mutants of SOD1 (Lang et al. 2012, 2015; Lindberg et al. 2005). So far, we tested only nine out of 16 chemical chaperones in our experimental model. Overall, only ER-15 promoted increased native state stability of SOD1bar-A4V in the corresponding organelle, supporting a potential therapeutic effect of this drug. ER-15 (C11) was shown previously to have no effect on neurodegeneration of C9orf72 drosophila ALS model, eventually associated with a possible failure on recognition of the KDEL peptide by the KDEL receptor (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). This because the ER15-KDEL tag C-terminal contains an amine group instead of a carboxyl group. Our results rather support that a significant amount of this drug must accumulate in the ER, given that ER-15 increased the stability of ER-SOD1bar-A4V but not cytosolic one. Moreover, ER-12, which is analogous to ER-15 but tagged with a KDEL having the carboxyl group in the C-terminal, showed a strong destabilizing effect on ER-SOD1bar-A4V, while no effect was observed in the cytosolic counterpart (Figure 7A). ER-12 induced-destabilization was similar to that one observed for lead compound PBA in cyto-SOD1bar-A4V (Figure 7A). Remarkably, all the three chemical chaperones increased the stability of SOD1bar-A4V in vitro (Figure 8A), suggesting that both ER and cytosolic environments impact the action of the drugs on mutant SOD1bar folding stability.

An intricate result was the increased folding stability of cyto-SOD1bar-G41D when supplemented with drugs mit-28 and Lys-14, while no effect was observed in the respective compartment-tagged protein (Figure 7B). Moreover, mit-28 showed no effect on SOD1bar-G41D stability in vitro (Figure 8B), while Lys-14 destabilized it (Figure 8B). Combined, these results suggest that the observed increased native state stability of the cytosolic G41D mutant must be prompted by a mechanism other than direct drug-SOD1bar interactions. One possibility could involve an inefficient targeting of the drugs to the respective subcellular compartments. Nevertheless, this idea is unlikely to be the main source of the stability shift as we previously identified accumulation of Lys-14 (C4) in the lysosome (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). Another hypothesis could be related with the potential cytotoxic effect of 1 mM Lys-14, as earlier quantified for PC12 cells (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). Previous studies have shown that cytosolic SOD1bar-G41D presents significantly lower folding stability while incubated with 10 μM of proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 24 h (Gnutt et al. 2019a), a condition also reported to induce cell death (Han et al. 2009). Interpreting our results in this context indicates that the reported increased folding stability of cyto-SOD1bar-G41D when incubated with the two chemical chaperones should also not derivate from a potential cytotoxic effect of the drugs. Lysosome and mitochondria dysfunction is a common ALS-phenotype observed in mutant SOD1 transgenic mouse and ALS-patients cells (Bicchi et al. 2021; Bordoni et al. 2022; Deng et al. 2006). In this regarding, examining which specific pathways might be activated/inhibited by these two chemical chaperones and how the increased SOD1bar folding stability impacts the overall homeostasis of these organelles may prove itself critical to the development of new therapeutics on ALS-linked mutant SOD1.

Lys-14 (C4) was previously shown to revert eye degeneration of ALS-Drophophila C9orf72 model while lead compound PBA had no effect in reverting this ALS-phenotype (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). In accordance, our results indicate that Lys-14 reduces the effective concentration required for a drug effect given that it modifies significantly SOD1bar-G41D folding stability in vitro whereas PBA bares no effect at the same concentration range (Figure 8). Detailed analysis of the potential mechanism of action of these two chemical chaperones (Figure 9) suggests that lysosome tag boosts the established ability of PBA to preferentially interact with exposed hydrophobic residues on unfolded proteins or peptides (Cortez and Sim 2014), therefore promoting the anti-aggregation effect at lower dosages. Lysosome tag in Lys-14 is chemically composed by a cyclic tertiary amine moiety, which structurally resembles the cyclic secondary amine side-chain of proline, a well-known protective osmolyte (Ignatova and Gierasch 2006). Albeit excluded from the protein backbone, proline was shown to form preferential interactions with exposed side-chains upon unfolding (Auton and Bolen 2005). Such observations support an eventual role of this cyclic amine moiety on increasing binding propensity to unfolded/misfolded conformations.

As a whole, our study provides a novel drug candidate for in vivo testing against disease progression in SOD1-ALS organisms’ models. ER-15 exhibited a specific subcellular localized activity as well as a mechanism of action distinct from that of lead compound PBA or Lys-14 (Figure 9). Such features open new perspectives on the potential therapeutic effects of this ER-targeted chemical chaperone against ALS and other protein misfolding diseases. On this direction, further studies must be conducted in order to evaluate the ability of ER-15 to act on the multiple dysregulated processes linked with SOD1 misfolding, including ER-UPR associated stress (Zhou et al. 2021) or ER-SOD1 aggregated load (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2020; Getter et al. 2015). Additional molecular details concerning ER-15 mechanism of action on SOD1 folding stability and aggregation can be achieved by robust thermodynamic models originated from experimental data (Auton and Bolen 2005; Guinn et al. 2011; Street et al. 2006) and theoretical coarse-grained models explicitly accounting for interactions among the chemical chaperone, protein and solvent (Sapir and Harries 2015). SOD1bar is over 40 residues shorter than SOD1 (full-length), leading to significant changes in the chemical composition of the protein surface (Danielsson et al. 2011). Since osmolyte effects could depend on the properties of the protein surface (Auton and Bolen 2005; Guinn et al. 2011), further studies are required to investigate the efficacy of the chemical chaperones on the full-length variant.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Cell culture

HeLa cells were cultured in low glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich), at 37 °C with 10 % CO2. Maintenance involved every second/third day splitting at confluences greater than 90 % to either T-25 flasks (CytoOne) for regular culturing or 6-well plates (CytoOne) for transfection. Fourty eight hours before the measurements, the transfected cells were seeded in glass bottom fluorodishes (WPI).

4.2 Plasmid construction, preparation and transfection

mpDream2.1 plasmids codifying cytosolic SOD1bar-A4V/G41D FRET sensor (with AcGFP1 in the N-terminal and mCherry in the C-terminal) were established previously (Gnutt et al. 2019b). To build ER-targeted SOD1, AcGFP1-SOD1bar-A4V-mCherry DNA sequence was first fused with KDEL sequence in the C-terminal and further inserted into mEmerald-Calreticuln-N-16 vector (Addgene plasmid #54023), replacing the original mEmerald sequence (In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (Takara)). For mitochondria-targeting, AcGFP1-SOD1bar-G41D-mCherry DNA sequence was inserted into mCherry-Mito-7 vector (Addgene plasmid #55102) (Olenych et al. 2007), swapping with mCherry sequence (In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (Takara)). Lastly, lysosome-targeted sensor was built by switching mEmerald sequence in mEmerald-MPO-N-18 vector (Addgene plasmid #54187) by AcGFP1-SOD1bar-G41D-mCherry (In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (Takara)). mEmerald-Calreticuln-N-16, mCherry-Mito-7 and mEmerald-MPO-N-18 vectors were a kind gift from Michael Davidson. Validation of successfully cloned constructs was done by in-house DNA sequencing service (Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Department of Biochemistry 1).

Plasmids containing the various SOD1bar sequences were transformed into stellar (HST08, Clontech) or NEB5α (New England BioLabs) Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells, according to the supplier’s instructions. Zippy miniprep (Zymo) or Zymo Pure Midiprep (Zymo) kits were used for DNA purification. Concentrations and purity levels were determined via UV/VIS absorption at 260/280 nm (NanoDrop 2000 or NanoDrop ONE, Thermo Fischer Scientific). Plasmid transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine® 3000 transfection Reagent kit (Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher) following the manufacture´s protocol. Quantities of the main reagents used were: 2 µg of plasmid DNA with 4 µL of Lipofectamine and 4 µL P3000 reagent. Transfections were conducted at confluences >80 %.

4.3 Protein expression and purification

Untagged SOD1bar-A4V/G41D-FRET vectors were transformed into NiCo21 (DE3) competent cells (New England BioLabs) and cultured in 1 L of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Sigma-Aldrich) until an O.D. of ∼0.6 (37 °C, 180 rpm). Protein expression was induced via addition of 500 µM of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 18 h at 18 °C. Cells were further harvested by centrifugation (5000 rcf for 15 min) and lysed with Clontech Xtractor buffer. The lysates were further loaded into a preequilibrated gravity flow His60 column (Clontech) and purified by following the manufacture’s protocol. Purified samples were buffer exchanged to 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 5.4 mM KCl and 274 mM NaCl (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich) via Amicon Ultra 30 kDa (Merck) and flash-freezed in liquid nitrogen for long storage (−80 °C).

4.4 Sample preparation

In vitro- Purified FRET-SOD1bar-A4V/G41D were thawn out from −80 °C and left at RT for 30 min. Incubation periods with each chemical chaperone at 1 and 5 mM took another 30 min at RT prior to FReI measurements. In vitro assays were all conducted in PBS buffer (pH 7.4).

In-cellulo- HeLa cells transfected with plasmids codifying for organelle-tagged or cytosolic SOD1bar-A4V/G41D were supplemented with 1 mM of each chemical chaperone 24 h prior to the measurements, at 37 °C and 10 % CO2. Before measurements, the cells were washed twice with 1 mL of Dulbecco´s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and immersed in a solution of Leibowitz supplemented with 30 % (v/v) FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mM of the respective chemical chaperone.

Seeded transfected cells or in vitro purified samples were concealed with a sterile coverslip (VWR) attached to the bottom of the WPI dish by a 120 µm spacer (Secure seal, Sigma-Aldrich) prior to each FReI measurement.

4.5 Fast relaxation imaging (FReI) technique

Fast relaxation imaging (FReI) technique was used to track the time evolution of the FRET-pair signal, along with a stepwise heating induced by fast infrared (IR) diode laser-temperature jumps (T-jumps) (2200 ± 20 nm, m2k laser, GmbH, Germany) of 25 s each (on average 14–16 T-jumps were applied) (Ebbinghaus et al. 2010). Images of AcGFP1 (Donor (D)) (497–527 nm) and mCherry (Acceptor (A)) (581–679 nm) emissions were acquired by two CCD cameras attached into a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 widefield fluorescence microscope every two frames per second (2 fps). AcGFP1 was excited by a 470 nm LED light with adjustable exposure times. Temperature-sensitive rhodamine B (Rho-B, Carl Roth) fluorescent dye (100 μM) was used to calibrate the laser heating jumps following a previously established protocol (Büning et al. 2017). Briefly, Rho-B temperature-dependent fluorescence signal was first normalized and further converted into temperature using the equation I Rho-B (T) = 1.652 − 0.03238 T + 0.0002082 T 2 (equation (1)). Temperature values on the last 3 s of the first 10 jumps were then averaged resulting in ∼2.3 ± 0.3 K per each (Figure 5B).

4.6 FReI data analysis

Recorded images with SOD1bar-A4V/G41D FRET signal (given by the ratio of donor to acceptor (D/A)) as a function of time were evaluated using ImageJ (US NIH) and Matlab software’s. A Region of Interest (ROI) of the same pixel size was draw on each image of AcGFP1 and mCherry channels either covering the cytosolic region of the cells or covering the bulk imaged area in vitro.

Both SOD1bar-A4V and -G41D transit reversibly between native (N) and unfolded (U) states during thermal unfolding in vitro and inside cells (Gnutt et al. 2019b). In order to compute melting temperature (T

m

) and modified standard-state free energies of folding (ΔG

f

0′) at 310 K (37 °C), we adopted the “thermodynamics from kinetics approach” developed by Gruebele and co-workers (Girdhar et al. 2011). Briefly, individual unfolding kinetics traces shown as the donor to acceptor difference, D(t) − αA(t) (

where A 0 and m A define the baseline of A (m A was fixed to 0), ΔT refers to the size of the temperature jump (here fixed to 2.3 K) and g (1) is the cooperativity parameter. The model assumes that the change in the heat capacity of (un)folding (ΔC p ) is 0 (Girdhar et al. 2011).

SOD1bar-A4V/G41D conformational stability is described by ΔG

f

0′ at 310 K, computed via:

Mean and standard deviation values corresponding to the different thermodynamic parameters computed for all conditions tested in this work are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The respective samples sizes are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

4.7 Confocal laser scanning microscopy (cLSM)

HeLa cells transiently expressing cytosol and ER-SOD1bar-A4V or cytosol, lysosome- and mitochondria-SOD1bar-G41D were imaged with an Olympus (FV3000) confocal laser scanning microscope (cLSM), using a 60× silicone-oil immersion-objective (UPLSAPO60XS2, 1.3NA). AcGFP1 was excited at 488 nm while the different organelle-markers were excited at 561 or 640 nm. The corresponding fluorescence emission signals were acquired by two sensitive gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) photomultipliers tubes (PMT). Cells were supplemented with 2 mL of Leibowitz +30 % of FBS and maintained at 37 °C (with a fixed humidity) throughout the measurement time via an incubator chamber (Okolab, Boldline T-unit) assembled into the microscope stage.

4.8 Chemical chaperone synthesis and targeting

4.8.1 Materials

Commercially available reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich-Merck, Holand-Moran, Acros Organic, Alfa Aesar, Bio-Lab Ltd., GL Biochem Ltd., and Chem-Impex International, and used without any additional purification. Sensitive reactions were carried out under dry nitrogen with magnetic stirring.

Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on aluminum sheets pre-coated with silica gel 60 F254 (Merck) using UV absorption and potassium permanganate (KMnO4) physical absorption for visualization.

Flash chromatography (FC) column was performed on SiliaFlash (SiO2) P60 (230−400 mesh) from Silicycle (Quebec, Canada).

Preparative Reverse Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) was performed on LUNA C18(2) (10 µm, 250 × 21.2 mm) column from Phenomenex, Inc. (Torrance, CA, USA), using Young Lin Instruments (Anyang, Korea). Compounds purified by RP-HPLC were eluted using an increase gradient of acetonitrile in H2O.

Analytical RP-HPLC was also performed on Young Lin Instruments using Chromolith Performance RP-18 endcapped (100 × 4.6 mm) analytic HPLC column from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). The purity of the final synthesized compounds was confirmed by using different gradients of acetonitrile and H2O with 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (v/v) at a constant flow of 1 ml/min in 10 min and the UV-detection was performed at 220 nm.

The 1H, 13C, 31P NMR, and 2D spectra were recorded at room temperature on a Bruker Advance NMR spectrometer (Vernon Hills, IL, USA) operating at 300, 400, 600, and 700 MHz, and were in accordance with the assigned structures. Also, four different 2D correlation experiments were ran to match the signal assignment to the 1D spectra: COSY, HMQC, HMBC and HMBC-N as we performed in the previous work (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). The spectra are reported in ppm units (δ) and coupling constants (J) in hertz. The chemical shifts are set relative to the internal standard TMS at 0 ppm. The samples were prepared by dissolving the synthesized compounds in CDCl3 (δ H = 7.26 ppm), D2O (δ H = 4.79 ppm), CD3CN (δ H = 1.94 ppm) and CD3OD (δ H = 3.31 ppm) (Gottlieb et al. 1997). The splitting pattern abbreviations are as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; quint, quintet; m, unresolved multiplet; dd, doublet of doublet; td, triplet of doublet; br, broad.

The structures were also confirmed by High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) which were obtained on a QTOF instrument (Agilent), using electrospray ionization (ESI).

Finally, for solid compounds, melting points were measured with a Fisher-Johns melting point apparatus (Waltham, MA, USA).

4.8.2 Chemistry

4.8.2.1 Lys/ER-targeted compounds

Lys-14, ER-12, ER-13 and ER-15 were synthesized and published previously (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021). The same general procedure was used to synthesize ER-targeted compounds; ER-20 and ER-21 via HBMA-AM resin and Fmoc strategy (Azoulay-Ginsburg et al. 2021).

(3S,6S,9S,12S)-3-(4-aminobutyl)-9-(2-carboxyethyl)-6-(carboxymethyl)-12-isobutyl-1,4,7,10-tetraoxo-1-(4-(4-phenylbutanamido)phenyl)-2,5,8,11-tetraazatridecan-13-oic acid, (SG-ER-20): After purification by preparative HPLC, the pure compound was obtained as a floppy white solid (109 mg, 85 %). mp = 190 °C; HPLC R T = 4.637 min. 1H NMR (700 MHz, D2O) δ H (ppm): 7.77 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, CONC=(C H(3)) 2 ), 7.50 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, (C H(2)) 2 CCO), 7.34 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, m-H Ar), 7.30 (2H, d, J = 7.3 Hz, o-H Ar), 7.23 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, p-H Ar), 4.67–4.65 (1H, m, Cα H(Asp) ), 4.45 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 7.8 Hz, Cα H(Lys) ), 4.38 (dd, J = 9.5, 4.8 Hz, Cα H(Glu) ), 4.25–4.23 (1H, m, Cα H(Leu) ), 3.03 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, Cε H 2 (Lys) NH2), 2.84 (1H, dd, J = 16.5, 5.4 Hz, Cβ H a,b (Asp) COOH), 2.75 (1H, dd, J = 16.6, 8 Hz, Cβ H a,b (Asp) COOH), 2.71 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.44 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.34 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, Cγ H 2 (Glu) COOH), 2.15–2.10 (1H, m, Cβ H a,b (Glu) ), 2.03 (2H, quint, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar), 1.94–1.88 (3H, m, Cβ H a,b (Glu) and Cβ H 2 (Lys) ), 1.72 (2H, quint, J = 7.2 Hz, Cδ H 2 (Lys) ), 1.64–1.60 (3H, m, Cβ H 2 (Leu) and Cγ H(Leu) (CH3)2), 1.54–1.49 (2H, m, Cγ H 2 (Lys) ), 0.9 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, (C H 3 (Leu) a,b), 0.86 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, (C H 3 (Leu) a,b ). 13C NMR (176 MHz, D2O) δ (ppm): 178.04 ( C(Leu) OOH), 177.39 ( C(Glu) OOH), 175.50 ( C(Asp) OOH), 175.15 ( C(4-PBA) ONH), 173.58 ( C(Lys) ONH), 172.08 ( C(Asp) NH), 172.00 ( C(Glu) NH), 169.85 (C(1) C ONH), 141.32 ( C Ar), 140.26 ( C(1) CONH), 128.39 (CONH C(4) ), 128.20 ( o-C Ar), 128.12 ( m-C Ar), 127.96 (CONC=( C(3) H) 2 ), 125.67 ( p-C Ar), 120.44 (( C(2) H) 2 CCO), 54.17 ( C α (Lys) , 52.68 ( C α (Leu) ), 52.51 ( C α (Glu) ), 50.57 ( C α (Asp) ), 39.62 ( C β (Leu) ), 38.69 ( C ε H2 (Lys) NH2), 36.20 ( C β (Asp) ), 35.44 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 33.83 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 30.18 ( C γ (Glu) ), 29.70 ( C β (Lys) ), 26.02 ( C δ (Lys) ), 25.92 ( C β (Glu) ), 25.82 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar), 24.00 ( C γ (Leu) ), 21.87 ( C H3 (Leu) ) a,b), 21.63 ( C γ (Lys) ), 20.17 ( C H3 (Leu) )a,b ). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C38H52N6O11 [M + H+], 769.3771; found, 769.3767.

(2S,5S,8S,11S,14S)-14-amino-11-(4-aminobutyl)-5-(2-carboxyethyl)-8-(carboxymethyl)-2-isobutyl-4,7,10,13,20-pentaoxo-23-phenyl-3,6,9,12,19-pentaazatricosanoic acid, (SG-ER-21): After purification by preparative HPLC, the pure compound was obtained as a floppy white solid (70 mg, 54 %). mp = 140 °C; HPLC R T = 3.699 min. 1H NMR (700 MHz, D2O) δ H (ppm): 7.39 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, m-H Ar), 7.30–7.28 (3H, m, o,p-H Ar), 4.62 (1H, dd, J = 7.6, 5.4 Hz, Cα H(Asp) ), 4.42 (1H, dd, J = 9, 5.4 Hz Cα H(Glu) ), 4.35 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, Cα H(Lys) ), 4.27 (1H, dd, J = 9.7, 4.3 Hz, Cα H(Leu) ), 4.04 (1H, t, J = 6.5 Hz, Cα H(Lys linker) ), 3.18 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, Cε H 2 (Lys linker) NH2), 3.02 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, Cε H 2 (Lys) NH2), 2.83 (1H, dd, J = 16.8, 5.4 Hz, Cβ H a,b (Asp) COOH), 2.74 (1H, dd, J = 16.3, 8 Hz, Cβ H a,b (Asp) COOH), 2.66 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.46–2.41 (2H, m, Cγ H 2 (Glu) COOH), 2.27 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.18–2.13 (1H, m, Cβ H a,b (Glu) ), 1.99–1.84 (6H, m, Cβ H a,b (Glu) , CH2C H 2 CH2Ar, Cβ H a,b (Lys) , Cβ H 2 ( Lys linker) ), 1.82–1.77 (1H, m, Cβ H a,b (Lys) ), 1.72 (2H, quint, J = 7.5 Hz, Cδ H 2 (Lys) ), 1.68–1.62 (3H, m, Cβ H 2 (Leu) and Cγ H(Leu) (CH3)2), 1.56 (2H, quint, J = 7.1 Hz, Cδ H 2 (Lys linker) ), 1.48–1.37 (4H, m, Cγ H 2 (Lys) and Cγ H 2 (Lys linker) ), 0.94 (3H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, (C H 3 (Leu) a,b), 0.90 (3H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, (C H 3 (Leu) )a,b ). 13C NMR (150 MHz, D2O) δ (ppm): 179.03 ( C(Leu) OOH), 178.81 ( C(Glu) OOH), 177.13 C(4-PBA) ONH), 176.17 ( C(Asp) OOH), 173.43 ( C(Lys) ONH), 172.95 ( C(Glu) NH), 172.86 ( C(Asp) NH), 170.35 ((C(Lys linker) ONH), 142.51 ( C Ar), 129.21 ( m-C Ar and o-C Ar), 126.74 ( p-C Ar), 54.43 ( C α (Lys) ), 53.77 ( C α (Leu) ), 53.51 ( C α (Glu) and C α (Lys linker) ), 51.61 ( C α (Asp) ), 40.64 ( C β (Leu) ), 39.72 ( C H2NH2), 39.36 ( C ε (Lys linker) ), 37.39 ( C β (Asp) ), 35.82 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 34.93 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 31.36 ( C γ (Glu) ), 31.12 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar), 30.90 ( C β (Lys) ), 28.51 ( C δ (Lys linker) ), 27.51 ( C β (Lys linker) ), 27.35 ( C β (Glu) ), 26.94 ( C δ (Lys) ), 25.13 ( C γ (Leu) ), 22.93 ( C H3 (Leu) a,b), 22.53 ( C γ (Lys linker) ), 22.00 ( C γ (Lys) ), 21.32 ( C H3 (Leu) a,b ). 15N NMR (71 MHz, D2O) δ H (ppm): −348.3 ( N H2 (Lys) ), −259.6 ( N H (Glu) ), −258.9 ( N H (Asp) ), −256.9 ( N H2 (Lys linker) ), −256.3 ( N H (Lys) ), −253.7 (( N H (Lys linker) ), −253.4 ( N H (Leu) ). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C37H59N7O11 [M + H+], 778.4345; found, 784.4347.

4.8.2.2 Mitochondria-targeted compounds

4.8.2.2.1 General procedure for the synthesis of amide or ester of mit-1–3, 10–12, and 19–21

The appropriate acid (1 mmol, 1 eq, 164.2 mg) was dissolved in ethyl acetate (EtOAc) (30 ml) and TBTU (1 mmol, 1 eq, 321 mg), and trimethylamine (TEA) (2 mmol, 2 eq, 0.27 ml) was added. The mixture was stirred till a clear solution was obtained, and the appropriate amine or alcohol (2 mmol, 2 eq) was then added. After being stirred for 12 h at room temperature, the mixture was washed with H2O (3 × 50 mL); and the organic phase was separated, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated at reduced pressure to obtain a crude product. Appropriate purification of the crude mixture yielded corresponding compounds, which were also characterized by HRMS and NMR.

N-(3-hydroxypropyl)-4-phenylbutanamide, (mit-1): The compound was obtained by using 4-PBA (10 mmol, 1 eq, 1642 mg) and 3-amino-1-propanol (20 mmol, 2 eq, 1.52 ml) as an amine. The crude product was obtained as a colorless oil and used without any purification. (1216 mg, 55 %). R f = 0.66 (9.5:0.5 DCM: MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.28–7.25 (2H, m, m-H Ar), 7.19–7.15 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 6.61 (1H, br, CON H ) 4.06 (1H, br, O H ), 3.59 (2H, t, J = 5.5 Hz, C H 2 OH), 3.34 (2H, q, J = 6.2 Hz, NHC H 2 ), 2.63 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.18 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 1.95 (2H, quint, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar), 1.65 (2H, quint, J = 6.1 Hz, NHCH2C H 2 CH2OH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 174.23 (N= C O), 141.42 ( C Ar), 128.42 ( o-C Ar), 128.38 ( m-C Ar), 125.97 ( p-C Ar), 59.28 ( C H2OH), 36.33 (NH C H2), 35.79 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.21 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 32.06 (NHCH2 C H2CH2OH), 27.28 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C13H19NO2 [M + H+], 222.149; found, 222.149.

N-(6-hydroxyhexyl)-4-phenylbutanamide, (mit-2): The compound was obtained by using 4-PBA (10 mmol, 1 eq, 1642 mg) and 6-amino-1-hexanol (20 mmol, 2 eq, 2344 mg) as an amine. The crude product was obtained as a white solid and used without any purification. (2263 mg, 86 %). mp = 54–56 °C; R f = 0.67 (9.5:0.5 DCM:MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.29–7.25 (2H, m, m-H Ar), 7.20–7.18 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 5.68 (1H, br, CON H ), 3.61 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 3.23 (2H, q, J = 6.2 Hz, NHC(6) H 2 ), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.17 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 1.96 (2H, quint, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar), 1.59–1.46 (4H, m, C(2) H 2 and C(5) H 2 ), 1.42–1.32 (4H, m, C(3) H 2 and C(4) H 2 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.89 (N= C O), 141.51 ( C Ar), 128.49 ( o-C Ar), 128.39 ( m-C Ar), 125.97 ( p-C Ar), 62.59 ( C(1) H2OH), 39.34 (NH C(6) H2), 35.90 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.21 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 32.51 ( C(2) H2), 29.60 ( C(5) H2), 27.19 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar), 26.50 ( C(4) H2), 25.28 ( C(3) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C16H25NO2 [M + Na+], 286.178; found, 286.177.

5-hydroxypentyl 4-phenylbutanoate, (mit-3): The compound was obtained by using 4-PBA (10 mmol, 1 eq, 1642 mg) and 1,5-pentanediol (50 mmol, 5 eq, 5.3 ml) as an alcohol. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH) to obtain the pure compound as colorless oil (2301 mg, 92 %). R f = 0.5 (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.30–7.25 (2H, m, m-H Ar), 7.20–7.16 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 4.07 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, COOC(5) H 2 ), 3.62 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.32 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 1.95 (2H, quint, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar), 1.70–1.54 (4H, m, C(2) H 2 and C(4) H 2 ), 1.47–1.36 (2H, m, C(3) H 2 ). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.97 (O= C O), 141.69 ( C Ar), 128.77 ( o-C Ar), 128.68 ( m-C Ar), 126.27 ( p-C Ar), 64.61 (COO C(5) H2), 62.85 ( C(1) H2OH), 35.42 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 33.94 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 32.55 ( C(2) H2), 28.74 ( C(4) H2), 26.82 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar), 22.53 ( C(3) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C15H22O3 [M + H+], 251.164; found, 251.164.

N-(3-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-4-phenylbutanamide, (mit-10): The compound was obtained by using 4-PBA (10 mmol, 1 eq, 1642 mg) and 3-aminobenzyl alcohol (20 mmol, 2 eq, 2460 mg) as an amine. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (1:1 EtOAc:hexane) to obtain the pure compound as brown solid (1560 mg, 58 %). mp = 50 °C; R f = 0.4 (1.1 EtOAc:hexane).1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.52 (1H, br, CON H ), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, NHCArC H Ar CAr), 7.32–7.26 (4H, m, NHCArC H Ar C H Ar and m-H Ar), 7.22–7.18 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 7.08 (1H, d, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2CArC H Ar ), 4.64 (2H, s, C H 2 OH), 2.70 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.33 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.05 (2H, quint, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.49 ( C O), 142.16 (CH2 C Ar), 141.75 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 138.47 (NH C Ar ), 129. 20 (NHCArCHAr C H Ar ), 128.77 (( m-C Ar)2), 128.73 (( o-C Ar)2), 126.31 ( p-C Ar), 123.02 (CH2CAr C H Ar ), 119.67 (NHCAr C H Ar CHAr), 119.12 (NHCAr C H Ar CAr), 64.74 ( C H2OH), 36.84 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.43 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 27.29 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C17H19NO2 [M + H+], 270.149; found, 270.148.

N-(4-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-4-phenylbutanamide (mit-11): The compound was obtained by using 4-PBA (10 mmol, 1 eq, 1642 mg) and 4-aminobenzyl alcohol (20 mmol, 2 eq, 2460 mg) as an amine. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (1:1 EtOAc:hexane) to obtain the pure compound as a brown solid (1800 mg, 67 %). mp = 75 °C; R f = 0.4 (1.1 EtOAc:hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.54 (1H, br, CON H ), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, NHC(C H Ar) 2 ), 7.29–7.15 (7H, m, CH2C(C H Ar) 2 and o,m,p-CH Ar), 4.57 (2H, s, C H 2 OH), 2.66 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.30 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.02 (2H, m, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 171.36 ( C O), 141.34 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 137.23 (NH C Ar), 136.82 (CH2 C Ar), 128.50 (( m-C Ar)2), 128.44 (( o-C Ar)2), 127.73 (CH2C( C HAr) 2 ), 126.04 ( p-C Ar), 120.11 (NHC(C H Ar) 2 ), 64.75 ( C H2OH), 36.64 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.05 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 26.84 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C17H19NO2 [M + H+], 270.149; found, 270.148.

4-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl 4-phenylbutanoate, (mit-12): The compound was obtained by using 4-PBA (10 mmol, 1 eq, 1642 mg) and 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (20 mmol, 2 eq, 2481 mg) as an alcohol. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (1:3 EtOAc:hexane) to obtain the pure compound as colorless oil (1782 mg, 66 %). R f = 0.7 (1:1 EtOAc:hexane). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.29–7.22 (4H, m, CH2C(C H Ar) 2 and m- C H Ar), 7.19–7.15 (3H, m, o,p-CH Ar), 6.96 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, OC(C H Ar) 2 ), 4.47 (2H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, C H 2 OH), 3.29 (1H, t, J = 5.3 Hz, O H ), 2.68 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.51 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.02 (2H, quint, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.69 ( C O), 150.20 (O C Ar), 141.57 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 139.08 (CH2 C Ar), 128.93 (( m-C Ar)2), 128.89 (( o-C Ar)2), 128.39 (CH2C( C HAr) 2 ), 126.51 ( p-C Ar), 121.87 (OC(C H Ar) 2 ), 64.54 ( C H2OH), 35.41 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 33.97 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 26.82 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C17H18O3 [M + Na+], 293.115; found, 293.114.

Tert-butyl (2-((3-hydroxypropyl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)(methyl)carbamate (mit-19): The compound was obtained by using boc-sarcosine (25 mmol, 1 eq, 4730 mg) and 3-amino-1-propanol (50 mmol, 2 eq, 3.9 ml) as an amine. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH) to obtain the pure compound as a white solid (5230 mg, 85 %). mp = 55 °C; R f = 0.25 (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 6.62 (1H, br, CON H ), 3.86 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.65 (2H, t, J = 5.4 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 3.43 (2H, q, J = 6 Hz, NHC(3) H 2 ), 3.25 (1H, br, O H ), 2.94 (3H, s, NC H 3 ), 1.70 (2H, quint, J = 6 Hz, C(2) H 2 ), 1.46 (9H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 170.43 (N= C O), 155.78 (O C ON), 80.85 ( C (CH3)3), 59.60 ( C(1) H2OH), 53.15 (N C H2CO), 36.46 (NH C(3) H2), 35.88 (N C H3), 32.08 ( C(2) H2), 28.33 (C( C H3) 3 ). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H22N2O4 [M + Na+], 269.1472; found, 264.1467.

Tert-butyl (2-((6-hydroxyhexyl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)(methyl)carbamate (mit-20): The compound was obtained by using boc-sarcosine (25 mmol, 1 eq, 4730 mg) and 6-amino-1-hexanol (50 mmol, 2 eq, 5850 mg) as an amine. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH) to obtain the pure compound as a white semi-solid (5080 mg, 89 %). mp = 37 °C; R f = 0.3 (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 6.66 (1H, br, CON H ), 3.83 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.59 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 3.45 (1H, br, O H ), 3.25 (2H, q, J = 6.2 Hz, NHC(6) H 2 ), 2.93 (3H, s, NC H 3 ), 1.56–1.50 (4H, m, C(2) H 2 and C(5) H 2 ), 1.46 (9H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 ), 1.40–1.34 (4H, m, C(3) H 2 and C(4) H 2 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 169.42 (N= C O), 156.13 (O C ON), 80.57 ( C (CH3)3), 62.19 ( C(1) H2OH), 52.87 (N C H2CO), 39.21 (NH C(6) H2), 35.78 (N C H3), 32.48 ( C(2) H2), 29.48 ( C(5) H2), 28.31 (C( C H3) 3 ), 26.52 ( C(4) H2), 25.38 ( C(3) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C14H28N2O4 [M + Na+], 311.1941; found, 311.1938.

5-hydroxypentyl N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-N-methylglycinate, (mit-21): The compound was obtained by using boc-sarcosine (25 mmol, 1 eq, 4730 mg) and 1,5-pentanediol (125 mmol, 5 eq, 13 ml) as an alcohol. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH) to obtain the pure compound as yellow oil (5100 mg, 74 %). R f = 0.15 (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH). Two rotamers were obtained in ratio of 1:1. Rotamer A: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 4.15 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, COOC(5) H 2 ), 3.96 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.61 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 2.92 (3H, s, NC H 3 ), 1.70–1.66 (2H, m, C(4) H 2 ), 1.60–1.57 (2H, m, C(2) H 2 ), 1.43 (11H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 and C(3) H 2 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 170.01 ( C OO), 156.17 (O C ON), 80.19 ( C (CH3)3), 65.00 (COO C(5) H2), 62.23 ( C(1) H2OH), 50.36 (N C H2CO), 35.58 (N C H3), 32.19 ( C(2) H2), 28.33 ( C(4) H2), 28.27 (C( C H3) 3 ), 22.19 ( C(3) H2). Rotamer B: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 4.15 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, COOC(5) H 2 ), 3.90 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.61 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 2.93 (3H, s, NC H 3 ), 1.70–1.66 (2H, m, C(4) H 2 ), 1.60–1.57 (2H, m, C(2) H 2 ), 1.47 (11H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 and C(3) H 2 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 170.01 ( C OO), 155.58 (O C ON), 80.19 ( C (CH3)3), 65.03 (COO C(5) H2), 62.23 ( C(1) H2OH), 51.11 (N C H2CO), 35.62 (N C H3), 32.19 ( C(2) H2), 28.44 ( C(4) H2), 28.33 (C( C H3) 3 ), 22.23 ( C(3) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C13H25NO5 [M + Na+], 298.1625; found, 298.1621.

4.8.2.2.2 General procedure for the synthesis of methanesulfonate mit-4–6, 13–15, and 22–24

The compounds were synthesized following the described protocol (Jameson et al. 2015). A solution of appropriate alcohol (1 eq, 1 mmol) and TEA (2.4 mmol, 2.4 eq) was stirred in DCM (15 mL) at room temperature for 5 min. Methane sulfonyl chloride (MsCl) (1.5 mmol, 1.5 eq) was added, and the reaction was stirred for a further 1 h. The reaction mixture was washed with H2O (5 × 50 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to yield a crude product. Appropriate purification of the crude mixture yielded corresponding compounds, which were also characterized by HRMS and NMR.

3-(4-phenylbutanamido)propyl methanesulfonate, (mit-4): The compound was obtained by using mit-1 (4 mmol, 1 eq, 885 mg). The crude product was obtained as a yellow oil and used without any purification (718 mg, 60 %). R f = 0.70 (9.8:0.2 DCM:MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.31–7.25 (2H, m, m-H Ar), 7.21–7.16 (3H, m, o,p-H Ar), 6.00 (1H, br, CON H ), 4.26 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, C H 2 O), 3.36 (2H, q, J = 6.3 Hz, NC H 2 ), 3.01 (3H, s, C H 3 ), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.19 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.00–1.90 (4H, m, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar and NCH2C H 2 CH2O). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.17 ( C O), 141.46 ( C Ar), 128.47( o-C Ar), 128.39 ( m-C Ar), 125.97 ( p-C Ar), 67.75 ( C H2O), 37.37 ( C H3), 35.82 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.62 (HN C H2), 35.21 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 29.19 (HNCH2 C H2CH2O), 27.08 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C14H21NO4S [M − H+], 298.112; found, 298.111.

6-(4-phenylbutanamido)hexyl methanesulfonate, (mit-5): The compound was obtained by using mit-2 (4 mmol, 1 eq, 1053 mg). The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (9:1 DCM:Et2O) to obtain the pure compound as a white solid (1079 mg, 79 %). mp = 45 °C; R f = 0.65 (9:1 DCM:Et2O). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.29–7.25 (2H, m, m-H Ar), 7.20–7.16 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 5.67 (1H, br, CON H ), 4.21 (2H, t, J = 6.5 Hz, C(1) H 2 OH), 3.22 (2H, q, J = 6.8 Hz, NHC(6) H 2 ), 2.98 (3H, s, C H 3 ), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.16 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.00–1.92 (2H, m, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar), 1.77–1.70 (2H, m, C(2) H 2 ), 1.53–1.31 (6H, m, C(3) H 2 , C(4) H 2 and C(5) H 2 ). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.82 (N= C O), 141.58 ( C Ar), 128.44 ( m-C Ar), 128.34 ( o-C Ar), 125.90 ( p-C Ar), 70.08 ( C(1) H2OS), 39.14 (NH C(6) H2), 37.25 ( C H3), 35.88 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.22 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 29.39 ( C(5) H2), 28.94 ( C(2) H2), 27.23 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar), 26.17 ( C(4) H2), 25.02 ( C(3) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C17H27NO4S [M + H+], 342.173; found, 342.173.

5-((methylsulfonyl)oxy)pentyl 4-phenylbutanoate, (mit-6): The compound was obtained by using mit-3 (4 mmol, 1 eq, 1000 mg) as starting material. The crude product was obtained as a yellow oil and used without any purification (1142 mg, 87 %). R f = 0.52 (100 % DCM). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.30–7.26 (2H, m, m-H Ar), 7.20–7.16 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 4.22 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, C(1) H 2 OS), 4.07 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, COOC(5) H 2 ), 3.00 (3H, s, C H 3 ), 2.65 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.32 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 1.95 (2H, quint, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar), 1.77 (2H, m, C(4) H 2 ), 1.67 (2H, m, C(2) H 2 ), 1.52–1.44 (2H, m, C(3) H 2 ). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.48 (O= C O), 141.37 ( C Ar), 128.47 ( o-C Ar), 128.38 ( m-C Ar), 125.98 ( p-C Ar), 69.69 ( C(1) H2OS), 63.86 (COO C(5) H2), 37.30 ( C H3), 35.11 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 33.59 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 28.74 ( C(4) H2), 28.04 ( C(2) H2), 26.50 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar), 22.04 ( C(3) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C16H24O5S [M + Na+], 351.1237; found, 351.1232.

3-(4-phenylbutanamido)benzyl methanesulfonate, (mit-13): The compound was obtained by using mit-10 (4 mmol, 1 eq, 1075 mg) as starting material. The crude product was obtained as an orange solid and used without any purification (1250 mg, 90 %). mp = 72 °C; R f = 0.51 (1:1 EtOAc:hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 8.19 (1H, br, CON H ), 7.61 (1H, s, NHCArC H Ar CAr), 7.52 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, NHCArC H Ar CHAr), 7.28–7.22 (3H, m, NHCArCHArC H Ar and m- (C H Ar) 2 ), 7.17–7.12 (3H, m, o, p-H Ar), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2CArC H Ar ), 5.09 (2H, s, C H 2 OS), 2.86 (3H, s, SC H 3 ), 2.63 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.33 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 1.99 (2H, quint, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 1712.48 ( C O), 140.93 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 138.30 (NH C Ar ), 133.70 (CH2 C Ar), 128.99 (NHCArCHAr C H Ar ), 128.00 (( m-C Ar)2), 127.97 (( o-C Ar)2), 125.56 ( p-C Ar), 123.66 (CH2CAr C H Ar ), 120.32 (NHCAr C H Ar CAr), 119.61 (NHCAr C H Ar CHAr), 71.10 ( C H2OS), 37.65 (S C H3), 36.15 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 34.64 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 26.44 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C18H21NO4S [M + H+], 348.126; found, 348.126.

N-(4-(chloromethyl)phenyl)-4-phenylbutanamide (mit-14): The compound was obtained by using mit-11 (4 mmol, 1 eq, 1056 mg) as starting material. The crude product was obtained as an orange solid and used without any purification. (716 mg, 63 %). mp = 50 °C; R f = 0.46 (1:3 EtOAc:hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 814 (1H, br, CON H ), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, NHC(C H Ar) 2 ), 7.26–7.22 (4H, m, m-CH Ar and CH2C(C H Ar) 2 ), 7.17–7.11 (3H, m, o,p-CH Ar), 4.50 (2H, s, C H 2 Cl), 2.62 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.32 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 1.99 (2H, m, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 171.83 ( C O), 141.30 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 138.13 (NH C Ar), 133.19 (CH2 C Ar), 129.29 (CH2C( C HAr) 2 ), 128.43 (( o-C Ar) 2 ), 128.41 (( m-C Ar) 2 ), 126.01 ( p-C Ar), 120.23 (NHC(C H Ar) 2 ), 46.00 ( C H2Cl), 36.61 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 35.06 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 26.92 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C17H18ClNO [M − H+], 286.1004; found, 286.1008.

Mit-15 was obtained as a mixture of compounds in ratio of 2:1: A mixture of compounds was obtained by using mit-12 (4 mmol, 1 eq, 1080 mg) as starting material. The crude product was obtained as a yellow oil and used without any purification. (615 mg, 50 %). R f = 0.7 (1:1 EtOAc:hexane).

4-(chloromethyl)phenyl 4-phenylbutanoate: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.37 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, CH2C(C H Ar) 2 ), 7.32–7.27 (2H, m, m- (C H Ar)2), 7.22–7.19 (3H, m, o,p-CH Ar), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, OC(C H Ar) 2 ), 4.54 (2H, s, C H 2 Cl), 2.73 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.56 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.07 (2H, quint, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.15 ( C O), 150.93 (O C Ar), 141.47 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 135.31 (CH2 C Ar), 130.08 (CH2C( C HAr) 2 ), 128.86 (( m-C Ar)2), 128.83 (( o-C Ar)2), 126.46 ( p-C Ar), 122.21 (OC(C H Ar) 2 ), 45.89 ( C H2Cl), 35.36 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 33.92 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 26.75 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar).

4-(((methylsulfonyl)oxy)methyl)phenyl 4-phenylbutanoate: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, CH2C(C H Ar) 2 ), 7.32–7.27 (2H, m, m- (C H Ar)2), 7.22–7.19 (3H, m, o,p-CH Ar), 7.09 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, OC(C H Ar) 2 ), 5.19 (2H, s, C H 2 OS), 2.88 (3H, s, SC H 3 ) 2.73 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2C H 2 Ar), 2.57 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, C H 2 CH2CH2Ar), 2.07 (2H, quint, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2C H 2 CH2Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.06 ( C O), 151.74 (O C Ar), 141.42 ( C Ar (4-PBA) ), 131.26 (CH2 C Ar), 130.46 (CH2C( C HAr) 2 ), 128.86 (( m-C Ar)2), 128.83 (( o-C Ar)2), 126.46 ( p-C Ar), 122.48 (OC(C H Ar) 2 ), 71.03 ( C H2OS), 38.64 (S C H3) 35.36 ( C H2CH2CH2Ar), 33.92 (CH2CH2 C H2Ar), 26.71 (CH2 C H2CH2Ar). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C18H20O5S [M + Na+], 371.093; found, 371.093.

Mit-22 was also obtained as a mixture of compounds: The mixture of compounds was obtained by using SG-mit-19 (10 mmol, 1 eq, 2460 mg) as starting material. The crude product was purified by SiO2 FC (9.5:0.5 DCM:MeOH) and the product was obtained as a colorless oil (2340 mg, 90 %). R f = 0.15 (1:1 EtOAc:hexane).

3-(2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)(methyl)amino)acetamido)propyl methanesulfonate, (minor product: 40 %): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 6.57 (1H, br, CON H ), 4.30–4.24 (2H, m, C(1) H 2 OS), 3.85 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.42 (2H, q, J = 6.2 Hz, NHC(3) H 2 ), 3.05 (3H, s, SC H 3 ), 2.94 (3H, s, NC H 3 ), 1.97 (2H, quint, J = 6.2 Hz, C(2) H 2 ), 1.46 (9H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 169.80 (N= C O), 156.20 (O C ON), 80.75 ( C (CH3)3), 67.44 ( C(1) H2OS), 53.18 (N C H2CO), 37.44 (S C H3), 35.93 (N C H3), 35.55 (NH C(3) H2), 29.23 ( C(2) H2), 28.33 (C( C H3) 3 ).

Tert-butyl ((5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-oxazin-2-yl)methyl)(methyl)carbamate, (major product, major rotamer: 40 %): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 4.30–4.24 (2H, m, C(1) H 2 O), 3.99 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.10 (2H, s, C=NC(3) H 3 ), 2.92 (2H, s, NC H 3 ), 2.75 (3H, s, C H 3 SO3H), 2.10 (2H, m, C(2) H 2 ), 1.47 (9H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 170.00 (N= C O), 155.48 (O C ON), 80.30 ( C (CH3)3), 61.86 ( C(1) H2O), 50.26 (N C H2CO), 39.36 ( C H3SO3H), 37.14 (C=N C(3) H3), 35.71 (N C H3), 28.33 (C( C H3) 3 ), 26.55 ( C(2) H2). (major product, minor rotamer: 20 %) 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ H (ppm): 4.30–4.24 (2H, m, C(1) H 2 O), 3.94 (2H, s, NC H 2 CO), 3.10 (2H, s, C=NC(3) H 3 ), 2.92 (2H, s, NC H 3 ), 2.75 (3H, s, C H 3 SO3H), 2.10 (2H, m, C(2) H 2 ), 1.42 (9H, s, C(C H 3 ) 3 ). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 170.00 (N= C O), 155.48 (O C ON), 80.30 ( C (CH3)3), 61.86 ( C(1) H2O), 50.89 (N C H2CO), 39.36 ( C H3SO3H), 37.06 (C=N C(3) H3), 35.71 (N C H3), 28.33 (C( C H3) 3 ), 26.55 ( C(2) H2). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H20N2O3 [M + H+], 229.1547; found, 229.1543.