Structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine antileishmanial pharmacophore: Design, synthesis, and antileishmanial activity of novel 2,4-disubstituted 5-nitroimidazoles

-

Romain Paoli-Lombardo

Abstract

As part of our ongoing antileishmanial structure–activity relationship study, a structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine ring to a 5-nitroimidazole moiety was conducted. A series of novel 2,4-disubsituted 5-nitroimidazole derivatives, including the 5-nitroimidazole analog of Hit A and the 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl analog of fexinidazole, were obtained by using the vicarious nucleophilic substitution of hydrogen (VNS) reaction, to substitute position 4, and by using the tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene methodology to modulate position 2. The molecular structures of eight novel 5-nitroimidazoles were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, LC/MS, and HRMS. The in vitro antileishmanial activity of these compounds was evaluated against the promastigote form of Leishmania infantum and their influence on cell viability was assessed on the human hepatocyte HepG2 cell line. The 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl analog of fexinidazole showed the best selectivity index of the series, displaying good activity against both the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 0.8 µM, SI > 78.1) and the promastigote form of Leishmania donovani (EC50 = 4.6 µM, SI > 13.6), and exhibiting low cytotoxicity on the HepG2 cell line (CC50 > 62.5 µM).

1 Introduction

Leishmaniases are vector-borne parasitic diseases transmitted to mammalian hosts, including humans, by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sandflies. They are caused by almost 20 species of flagellated protozoa belonging to the Leishmania genus [1]. These diseases are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), a heterogeneous group of infections mainly found in tropical and subtropical developing countries and of little interest to pharmaceutical companies [2]. Present in 98 countries, leishmaniases remain a major public health problem worldwide, potentially infecting over a billion of the world’s poorest people and causing nearly a million new cases every year. These diseases are strongly associated with impoverished environments, malnutrition, lack of sanitation, and immunodeficiency (leishmania-HIV co-infection) [3]. Leishmaniases are divided into three main clinical forms: (1) cutaneous leishmaniasis, the most common manifestation of the disease with 600,000 to 1 million new cases annually; (2) mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, predominantly found in South America, affecting the nasal and oral mucosa; and (3) life-threatening visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar, with an estimated 50,000–90,000 new cases of VL reported annually and more than 90% of cases distributed in seven countries: Brazil, India, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan [4,5]. If left untreated, VL is lethal in over 95% of cases and is responsible for more than 30,000 deaths annually. In humans, VL is caused by two species of Leishmania: Leishmania infantum in Latin America and the Mediterranean Basin and Leishmania donovani in Africa and Asia [6]. In the absence of an effective vaccine in humans [7], treatment of VL relies on the use of a small number of drugs. Unfortunately, most of them suffer from drawbacks that limit their application [8]: severe side effects, increasing resistance and constraining administration for pentavalent antimonials [9], high cost, parenteral administration, and cold chain compliance for the liposomal form of amphotericin B [10,11], and teratogenic properties for miltefosine, the only drug available orally for the treatment of VL [12]. Moreover, the number of new antileishmanial chemical entities in clinical trials is limited with only six compounds in the DNDi portfolio, including five at early stage (phase I) [13]. Thus, the development of new effective, safe, and affordable oral drugs is urgently needed to strengthen and diversify the antileishmanial drug arsenal.

Since the discovery of their anti-infective properties in the 1940s, nitroheterocyclic compounds have been widely used to treat bacterial and parasitic infections [14,15]. In particular, 5-nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have traditionally been used as antibacterial and anti-parasitic agents [16,17] and have been studied for decades by our team [18]. Recently, fexinidazole, a new non-genotoxic 5-nitroimidazole derivative (Figure 2), was approved as the first all-oral treatment for sleeping sickness [19], renewing interest in the development of new 5-nitroimidazoles active against other kinetoplastid infections, such as leishmaniases. Fexinidazole and other antikinetoplastid nitroaromatic compounds act as prodrugs bioactivated by the parasitic type 1 nitroreductases (NTRs) [16,17]. This enzyme, essential for Leishmania and Trypanosoma and absent in mammalian cells, can catalyze the reduction of the nitro group in the parasite cell, producing nitroso and hydroxylamine intermediates and reactive oxygen species able to form covalent adducts with DNA and leading to the death of the parasite [20]. Unfortunately, the lack of crystal structure for parasitic NTRs and their low degree of homology with bacterial NTRs rule out the molecular docking approach to design new nitroaromatic compound substrates of parasitic NTRs.

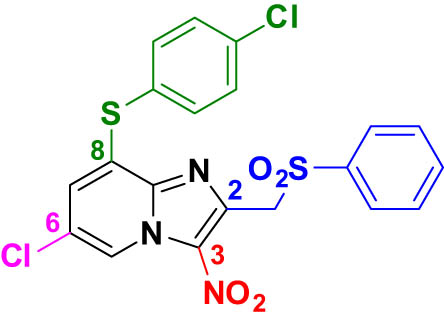

To develop novel nitroheterocyclic compounds substrate of parasitic NTRs exerting antileishmanial activity, our team has previously described a new hit compound (Hit A) in the 3-nitroimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine series, through pharmacomodulation work focused on positions 2 and 8 of the moiety [21]. This antileishmanial hit, substituted by a phenylsulfonylmethyl group at position 2, a chlorine atom at position 6, and a 4-chlorophenylthioether group at position 8, showed good in vitro activity against the promastigote form of L. infantum and L. donovani and low cytotoxicity on the human hepatocyte (HepG2) cell line, but exhibited poor in vitro mouse liver microsomal stability and aqueous solubility (Table 1).

Structure and in vitro biological profile of Hit A

|

|

|---|---|

| Hit A | |

| EC50 L. donovani promastigotes (µM) | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| EC50 L. infantum promastigotes (µM) | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| CC50 HepG2 (µM) | >100 |

| Microsomal stability: half-life (min)* | 3 |

| Thermodynamic solubility at pH 7.4 (µM) | 1.4 |

*Microsomal stability was assessed on female mouse microsomes.

Thus, as part of our ongoing structure–activity relationship (SAR) study (Figure 1) to improve the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of Hit A and to obtain an ideal candidate for further in vivo studies [22,23], a structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine core to a 5-nitroimidazole moiety was conducted (Figure 2). In particular, the aim of this work was to synthesize the 5-nitroimidazole analog of Hit A and the 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl analog of fexinidazole to compare their biological profile. These two compounds and other 2-substituted 5-nitromidazole derivatives were obtained, using several reactions developed by our team, such as the vicarious nucleophilic substitution of hydrogen (VNS) reaction, to substitute position 4 [24,25], and the tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE) methodology, to modulate position 2 [26,27].

![Figure 1

Antileishmanial structure–activity relationship study in 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine series.](/document/doi/10.1515/hc-2022-0176/asset/graphic/j_hc-2022-0176_fig_001.jpg)

Antileishmanial structure–activity relationship study in 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine series.

![Figure 2

Structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine pharmacophore into a 2,4-disubsituted 5-nitroimidazole moiety and structure of fexinidazole.](/document/doi/10.1515/hc-2022-0176/asset/graphic/j_hc-2022-0176_fig_002.jpg)

Structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine pharmacophore into a 2,4-disubsituted 5-nitroimidazole moiety and structure of fexinidazole.

2 Results and discussion

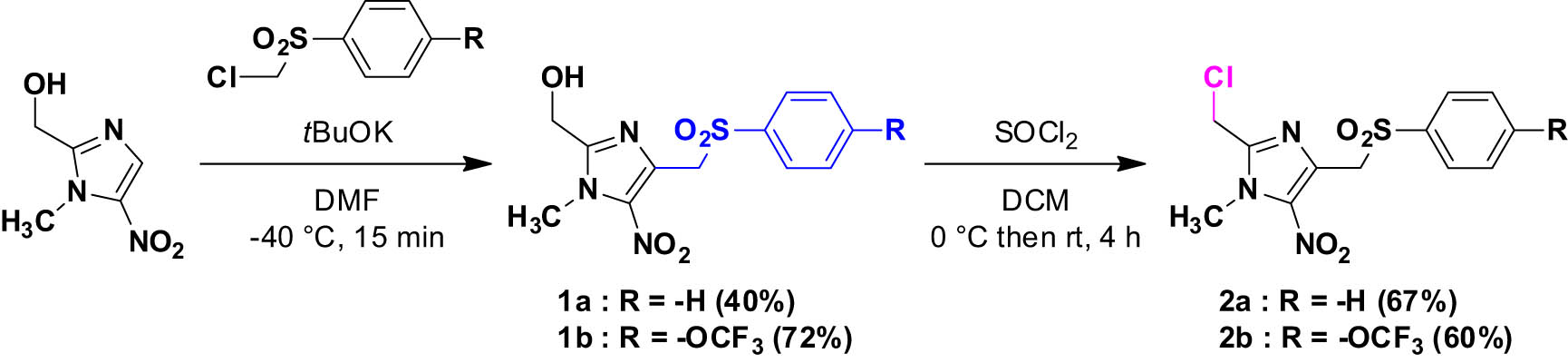

2.1 Synthesis

The 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl-5-nitroimidazole compounds 1a and 1b were prepared by vicarious nucleophilic substitution of hydrogen at position 4 of commercially available (1-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methanol (Scheme 1), followed by a chlorination reaction at position 2 with thionyl chloride, to give the 2-chloromethyl intermediates 2a and 2b [28,29].

Synthesis of compounds 1a–1b and 2a–2b.

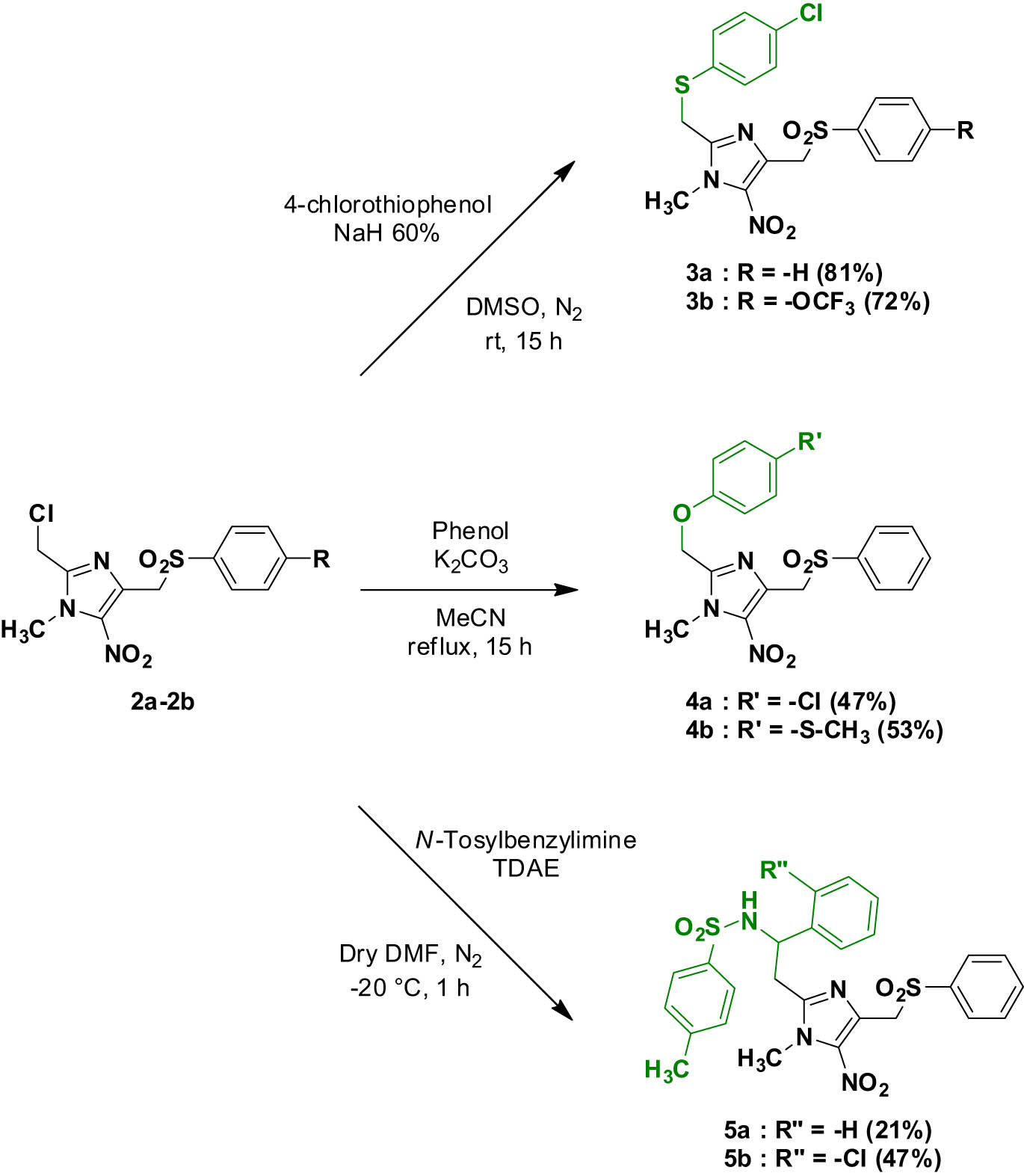

Using conditions similar to those previously reported [21], a 4-chlorophenylthioether moiety was introduced at position 2 of intermediates 2a and 2b, to obtain the 5-nitroimidazole analogs of Hit A 3a and 3b in good yields (Scheme 2).

Synthesis of compounds 3a–3b, 4a–4b, and 5a–5b.

O-alkylation reactions were performed at position 2 of intermediate 2a in the presence of the desired phenol, to afford the 4-chlorophenol derivative 4a and the 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl analog of fexinidazole 4b (Scheme 2).

Finally, we used a TDAE methodology previously described by our team to generate first a stable 2-methyl carbanion [27], which was reacted with N-tosylbenzylimines to give compounds 5a and 5b in moderate yields (Scheme 2) [30].

2.2 Biological results

The in vitro antileishmanial activity of intermediates 1b and 2b and compounds 3a to 5b was evaluated against the promastigote form of L. infantum and compared to Hit A and to reference drugs (amphotericin B, miltefosine, and fexinidazole) (Table 2). Their influence on cell viability was assessed on the human hepatocyte HepG2, using doxorubicin as a positive control. The in vitro antileishmanial activity of the best compounds was also evaluated against the promastigote form of L. donovani.

In vitro evaluation of molecules 1b, 2b, and 3a–5b on L. infantum promastigotes and on the human hepatocyte HepG2 line. In vitro evaluation of molecules 3a and 4b on L. donovani promastigotes

| CC50 HepG2 (µM) | EC50 L. inf. pro. (µM) | Selectivity Index (SI) L. inf. pro. | EC50 L. dono. pro. (µM) | Selectivity Index (SI) L. dono. pro. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | >125a | >50 | <2.5 | — | — |

| 2b | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.5 | — | — |

| 3a | >50a | 1.2 ± 0.2 | >41.7 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | >12.2 |

| 3b | 11.9 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 4.6 | — | — |

| 4a | 29.5 ± 5.4 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 14.8 | — | — |

| 4b | >62.5 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 | >78.1 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | >13.6 |

| 5a | >25a | 9.3 ± 2.6 | >2.7 | — | — |

| 5b | 32.4 ± 10.6 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 5.2 | — | — |

| Hit A | >100 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | >166.7 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | >100 |

| Doxorubicinb | 0.20 ± 0.02 | — | — | — | — |

| Amphotericin Bc | 8.8 ± 0.3 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 220 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 125.7 |

| Miltefosinec | 85.0 ± 8.8 | 18.2 ± 0.5 | 4.7 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 27.4 |

| Fexinidazolec | >100 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | >100 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | >83.3 |

aThe product could not be tested at higher concentrations due to a lack of solubility in the culture medium.

bDoxorubicin was used as a cytotoxic reference drug.

cAmphotericin B, miltefosine, and fexinidazole were used as antileishmanial reference drugs.

Bold was used to highlight the best compound of the series.

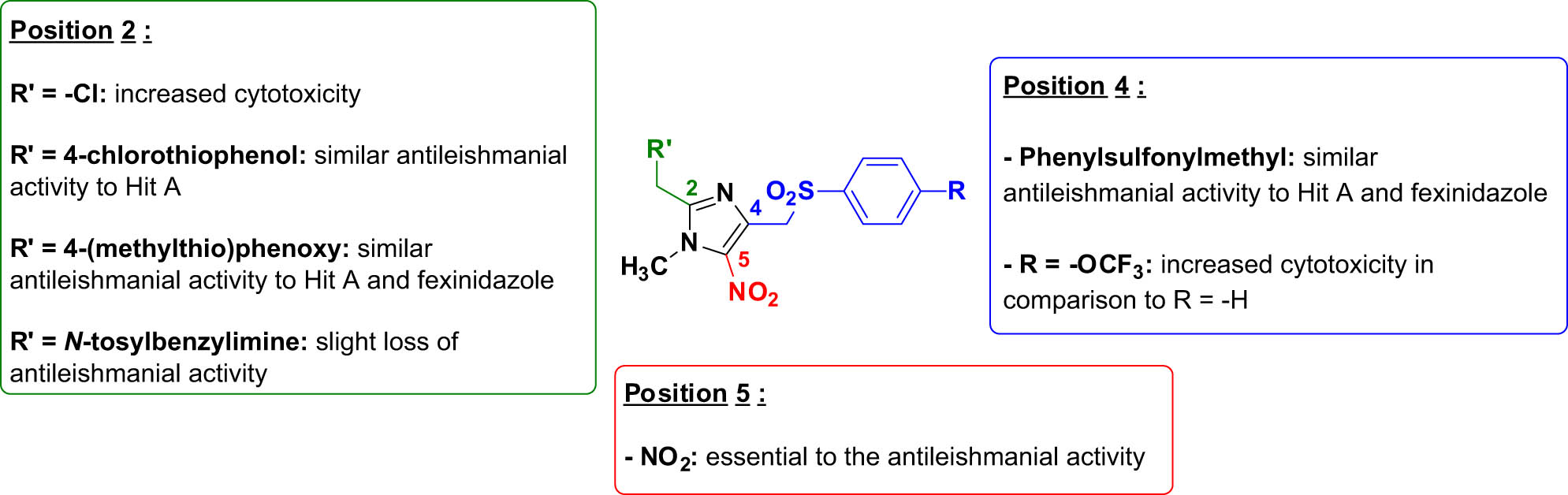

The 2-hydroxymethyl intermediate 1b was not active in vitro against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 > 50 µM) while the 2-chloromethyl intermediate 2b showed a good antileishmanial activity (EC50 = 1.1 µM) but was cytotoxic on the HepG2 cell line (CC50 = 2.7 µM). The substitution of the chlorine atom at position 2 of intermediate 2b by a 4-chlorophenylthioether moiety (compound 3b) resulted in reduced cytotoxicity on the HepG2 cell line (CC50 = 11.9 µM) and similar activity against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 2.6 µM). The 5-nitroimidazole analog of Hit A 3a showed a good selectivity index (SI > 41.7) with an EC50 value close to the one of fexinidazole against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 1.2 µM), no cytotoxicity on the HepG2 cell line at the tested concentrations and good solubility in the HepG2 culture medium (CC50 > 50 µM). Compound 3a also showed a good activity against the promastigote form of L. donovani (EC50 = 4.1 µM) but was inferior to Hit A, fexinidazole, and miltefosine. The replacement of the sulfur atom of the 4-chlorophenylthioether moiety of compound 3a by an oxygen atom (compound 4a) resulted in a lower selectivity index (SI = 14.8) while remaining active against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 2.0 µM). The 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl analog of fexinidazole 4b was the best compound of the series (SI > 78.1), displaying similar activity to fexinidazole and Hit A against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 0.8 µM), no cytotoxicity on the HepG2 cell line at the tested concentrations and good solubility in the HepG2 culture medium (CC50 > 62.5 µM). Its activity against the promastigote form of L. donovani (EC50 = 4.6 µM) was lower than that of Hit A, fexinidazole, and miltefosine and quite similar to compound 3a. Finally, the introduction of the two N-tosylbenzylimine moieties (compounds 5a and 5b) at position 2 of the 5-nitroimidazole scaffold resulted in a slight loss of activity against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 9.3 µM and EC50 = 6.2 µM, respectively). The antileishmanial SAR study of the novel 5-nitroimidazole derivatives was summarized in Figure 3.

Antileishmanial structure–activity relationship study of novel 5-nitroimidazole derivatives.

3 Conclusion

This antileishmanial SAR study focused on the structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine ring to a 5-nitroimidazole moiety. Thus, 8 new 2,4-disubsituted 5-nitroimidazole derivatives were obtained, including the 5-nitroimidazole analog of Hit A (compound 3a) and the 4-phenylsulfonylmethyl analog of fexinidazole (compound 4b), using the VNS reaction and TDAE methodology. Compound 4b was the best derivative of the series, showing the best selectivity index due to its good activity against the promastigote form of L. infantum (EC50 = 0.8 µM, SI > 78.1) and the promastigote form of L. donovani (EC50 = 4.6 µM, SI > 13.6), its lack of cytotoxicity on the HepG2 cell line and its good solubility in the HepG2 culture medium (CC50 > 62.5 µM). These encouraging results paved the way for exploring new promising fexinidazole analogs substituted at position 4 of the imidazole ring.

4 Experimental

4.1 Experimental details

Melting points were determined on a Köfler melting point apparatus (Wagner & Munz GmbH, München, Germany) and were uncorrected. HRMS spectrum (ESI) was recorded on an SYNAPT G2 HDMS (Waters) at the Faculté des Sciences de Saint-Jérôme (Marseille). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 250 MHz or a Bruker Avance NEO 400 MHz NanoBay spectrometer at the Faculté de Pharmacie of Marseille. (1H NMR: reference CDCl3 δ = 7.26 ppm, reference DMSO-d 6 δ = 2.50 ppm and 13C NMR: reference CDCl3 δ = 76.9 ppm, reference DMSO-d 6 δ = 39.52 ppm). The following adsorbent was used for column chromatography: silica gel 60 (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, particle size 0.063–0.200 mm, 70–230 mesh ASTM). TLC was performed on 5 cm × 10 cm aluminum plates coated with silica gel 60F-254 (Merck) in an appropriate eluent. Visualization was performed with ultraviolet light (234 nm). The purity determination of synthesized compounds was checked by LC/MS analyses, which were realized at the Faculté de Pharmacie of Marseille with a Thermo Scientific Accela High-Speed LC System® (Waltham, MA, USA) coupled using a single quadrupole mass spectrometer Thermo MSQ Plus®. The purity of all the synthesized compounds was >99%, except for the compound 5b for which the purity was >90%. The RP-HPLC column is a Thermo Hypersil Gold® 50 mm × 2.1 mm (C18 bounded), with particles of a diameter of 1.9 mm. The volume of the sample injected into the column was 1 µL. Chromatographic analysis, total duration of 8 min, was on the gradient of the following solvents: t = 0 min, methanol/water 50:50; 0 < t < 4 min, linear increase in the proportion of methanol to a methanol/water ratio of 95:5; 4 < t < 6 min, methanol/water 95:5; 6 < t < 7 min, linear decrease in the proportion of methanol to return to a methanol/water ratio of 50:50; and 6 < t < 7 min, methanol/water 50:50. The water used was buffered with ammonium acetate 5 mM. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.3 mL/min. The retention times (t R) of the molecules analyzed were indicated in min. Reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fluorochem and used without further purification. Copies of 1H NMR and 13C NMR are available in the Supplementary Materials.

4.2 Synthesis of {1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}methanol (1a)

To a solution of tBuOK (1.95 g, 17.4 mmol, 4 equiv) in dry DMF (15 mL) at −40°C was added a solution of chloromethylsulfonylbenzene (1.66 g, 8.7 mmol, 2 equiv) in dry DMF (15 mL). Then, a solution of (1-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methanol (0.683 g, 4.35 mmol, 1 equiv) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at −40°C for 15 min. A 2 M solution of HCl was added until pH 1 and the aqueous layer was extracted three times with ethyl acetate. Then, the organic layer was washed four times with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 1a was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: cyclohexane-dichloromethane 2:8) as a yellow solid in 40% yield (0.541 g). mp 153°C. 1H NMR (250 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.75–7.72 (m, 3H), 7.64–7.58 (m, 2H), 5.74 (brs, 1H), 4.91 (s, 2H), 4.53 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (63 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 150.4, 138.9, 137.4, 134.2, 131.6, 129.4 (2C), 127.9 (2C), 55.9, 55.3, 34.1. LC/MS ESI+ t R 3.17, (m/z) [M + H]+ 312.07. HRMS (+ESI): 312.0646 [M + H]+. Calcd for C12H14N3O5S: 312.0649 [25].

4.3 Synthesis of {1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(4-trifluoromethoxyphenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}methanol (1b)

To a solution of tBuOK (1.95 g, 17.4 mmol, 4 equiv) in dry DMF (15 mL) at −40°C was added a solution of 1-(chloromethyl)sulfonyl-4-(trifluoromethoxy)benzene (2.39 g, 8.7 mmol, 2 equiv) in dry DMF (15 mL). Then, a solution of (1-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methanol (0.683 g, 4.35 mmol, 1 equiv) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at −40°C for 15 min. A 2 M solution of HCl was added until pH 1 and the aqueous layer was extracted three times with ethyl acetate. Then, the organic layer was washed four times with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 1b was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane-ethyl acetate 6:4) as a white solid in 72% yield (1.24 g). mp 116°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.97–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 5.71 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.97 (s, 2H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 152.1, 150.5, 137.6, 137.4, 131.3, 130.9 (2C), 121.4 (2C), 119.8 (q, J = 258.3 Hz), 55.9, 55.3, 34.0. LC/MS ESI+ t R 4.80, (m/z) [M + H]+ 395.97. HRMS (+ESI): 396.0472 [M + H]+. Calcd for C13H13F3N3O6S: 396.0472. HPLC purity >99%.

4.4 Synthesis of 2-(chloromethyl)-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (2a)

To a solution of {1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}methanol (1a) (0.5 g, 1.61 mmol, 1 equiv) in dichloromethane (15 mL) at 0°C was added thionyl chloride (234 µL, 3.22 mmol, 2 equiv) and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. A 1 M K2CO3 solution was added to neutralize and the aqueous layer was extracted three times with dichloromethane. Then, the organic layer was washed four times with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 2a was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: petroleum ether-ethyl acetate 5:5) as a brown solid in 67% yield (0.354 g). mp 154°C. 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.87–7.75 (m, 2H), 7.70–7.59 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.49 (m, 2H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 3.97 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (63 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 145.9, 138.8, 137.9, 134.3, 132.4, 129.3 (2C), 128.4 (2C), 55.9, 40.0, 34.7. LC/MS ESI+ t R 4.28, (m/z) [M + H]+ 330.05/332.04. HRMS (+ESI): 330.0311 [M + H]+. Calcd for C12H13ClN3O4S: 330.0310 [25].

4.5 Synthesis of 2-{chloromethyl)-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(4-trifluoromethoxyphenylsulfonyl]methyl}-1H-imidazole (2b)

To a solution of {1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(4-trifluoromethoxyphenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}methanol (1b) (0.5 g, 1.26 mmol, 1 equiv) in dichloromethane (15 mL) at 0°C was added thionyl chloride (183 µL, 2.52 mmol, 2 equiv) and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. A 1 M K2CO3 solution was added to neutralize and the aqueous layer was extracted three times with dichloromethane. Then, the organic layer was washed four times with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 2b was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane) as a white solid in 60% yield (0.314 g). mp 84°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.91–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.90 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 152.1, 146.1, 137.6, 137.3, 131.5, 130.9 (2C), 121.4 (2C), 119.8 (q, J = 258.8 Hz), 55.1, 36.0, 34.3. LC/MS ESI+ t R 6.31, (m/z) [M + H]+ 412.21/414.18. HRMS (+ESI): 414.0132 [M + H]+. Calcd for C13H12ClF3N3O5S: 414.0133. HPLC purity >99%.

4.6 Synthesis of 2-{[(4-chlorophenyl)thio]methyl}-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (3a)

To a sealed 20 mL flask containing sodium hydride (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (0.049 g, 1.21 mmol, 2 equiv) in dimethylsulfoxide (3 mL), 4-chlorothiophenol (0.175 g, 1.21 mmol, 2 equiv) was added under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. Then, a solution of 2-(chloromethyl)-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (2a) (0.2 g, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) in dimethylsulfoxide (6 mL) was injected. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 h at room temperature. The mixture was slowly poured into an ice–water mixture and precipitated. The solid was collected by filtration and dried under reduced pressure. Compound 3a was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane) as a white solid in 81% yield (0.214 g). mp 105°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.71 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.88 (s, 2H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 3.81 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 147.5, 138.7, 137.4, 134.0, 133.1, 131.9, 131.6, 131.3 (2C), 129.2 (2C), 129.0 (2C), 127.8 (2C), 55.2, 34.2, 29.1. LC/MS ESI+ t R 5.67, (m/z) [M + H]+ 437.92/439.98. HRMS (+ESI): 438.0342 [M + H]+. Calcd for C18H17ClN3O4S2: 438.0344. HPLC purity >99%.

4.7 Synthesis of 2-{[(4-chlorophenyl)thio]methyl}-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(4-trifluoromethoxyphenylsulfonyl]methyl)-1H-imidazole (3b)

To a sealed 20 mL flask containing sodium hydride (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (0.038 g, 0.96 mmol, 2 equiv) in dimethylsulfoxide (3 mL), 4-chlorothiophenol (0.139 g, 0.96 mmol, 2 equiv) was added under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. Then, a solution of 2-{chloromethyl)-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(4-trifluoromethoxyphenylsulfonyl]methyl}-1H-imidazole (2b) (0.2 g, 0.48 mmol, 1 equiv) in dimethylsulfoxide (6 mL) was injected. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 h at room temperature. The mixture was slowly poured into an ice–water mixture, extracted three times with ethyl acetate. Then, the organic layer was washed four times with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 3b was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane) as a white solid in 72% yield (0.18 g). mp 93°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.81–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.58–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.33 (m, 4H), 4.95 (s, 2H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 152.0, 147.6, 137.5, 137.4, 133.2, 131.7, 131.6, 131.3 (2C), 130.8 (2C), 129.0 (2C), 121.3 (2C), 119.8 (d, J = 258.5 Hz), 55.1, 34.2, 29.1. LC/MS ESI+ t R 6.32, (m/z) [M + H]+ 521.87/523.80. HRMS (+ESI): 522.0166 [M + H]+. Calcd for C19H16ClF3N3O5S2: 522.0167. HPLC purity >99%.

4.8 Synthesis of 2-[(4-chlorophenoxy)methyl]-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (4a)

To a solution of 2-chloromethyl-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (2a) (0.2 g, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) in acetonitrile (10 mL), 4-chlorophenol (124 µL, 1.22 mmol, 2 equiv) and potassium carbonate (0.211 g, 1.53 mmol, 2.5 equiv) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred and heated under reflux for 15 h. Then, the mixture was slowly poured into an ice–water mixture, extracted three times with dichloromethane, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 4a was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane) as a white solid in 47% yield (0.12 g). mp 122°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.78–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.26 (s, 2H), 4.94 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 156.3, 145.8, 138.8, 137.8, 134.1, 131.6, 129.3 (2C), 129.3 (2C), 127.8 (2C), 125.4, 116.9 (2C), 62.2, 55.1, 34.3. LC/MS ESI+ t R 5.57, (m/z) [M + H]+ 421.87/423.92. HRMS (+ESI): 422.0573 [M + H]+. Calcd for C18H17ClN3O5S: 422.0572. HPLC purity >99%.

4.9 Synthesis of 1-methyl-2-{[4-(methylthio)phenoxy]methyl}-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (4b)

To a solution of 2-chloromethyl-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (2a) (0.2 g, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) in acetonitrile (10 mL), 4-methylsulfonylphenol (0.171 g, 1.22 mmol, 2 equiv) and potassium carbonate (0.211 g, 1.53 mmol, 2.5 equiv) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred and heated under reflux for 15 h. Then, the mixture was slowly poured into an ice–water mixture, extracted three times with dichloromethane, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 4b was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane) as a yellow solid in 53% yield (0.14 g). mp 122°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 7.75–7.69 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.26 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 4.94 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 155.6, 146.1, 138.8, 137.8, 134.1, 131.6, 129.9, 129.3 (2 C), 128.7 (2C), 127.8 (2C), 115.9 (2C), 62.1, 55.1, 34.3, 16.3. LC/MS ESI+ t R 5.53, (m/z) [M + H]+ 433.91. HRMS (+ESI): 434.0840 [M + H]+. Calcd for C19H20N3O5S2: 434.0839. HPLC purity >99%.

4.10 Synthesis of 4-methyl-N-(2-{1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}-1-phenylethyl)benzenesulfonamide (5a)

To a solution of 2-chloromethyl-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (2a) (0.2 g, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) in dry DMF (7 mL) at −20°C was added (E)-N-benzylidene-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide (0.239 g, 0.92 mmol, 1.5 equiv). Then, tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (142 µL, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) was added under N2 atmosphere and the reaction mixture was stirred at −20°C for 1 h. The mixture was slowly poured into an ice–water mixture and precipitated. The solid was collected by filtration and dried under reduced pressure. Compound 5a was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane-ethyl acetate 9:1) as a white solid in 21% yield (0.07 g). mp 113°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 8.47 (s, 1H), 7.79–7.67 (m, 3H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.31–7.19 (m, 5H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 4.59 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (s, 3H), 3.08 (dd, J = 15.0, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (dd, J = 15.0, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 148.5, 142.2, 141.1, 138.7, 138.5, 136.3, 134.1, 132.7, 129.2 (2C), 129.1 (2C), 128.3 (2C), 128.0 (2C), 127.4, 126.4 (2C), 126.0 (2C), 56.3, 55.2, 34.7, 33.8, 20.8. LC/MS ESI+ t R 6.37, (m/z) [M + H]+ 555.15. HRMS (+ESI): 555.1368 [M + H]+. Calcd for C26H27N4O6S2: 555.1367. HPLC purity > 99%.

4.11 N-[1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-{1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}ethyl]-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide (5b)

To a solution of 2-chloromethyl-1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole (2a) (0.2 g, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) in dry DMF (7 mL) at −20°C was added (E)-N-(2-chlorobenzylidene)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide (0.27 g, 0.92 mmol, 1.5 equiv). Then, tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (142 µL, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv) was added under N2 atmosphere and the reaction mixture was stirred at −20°C for 1 h. The mixture was slowly poured into an ice–water mixture, extracted three times with ethyl acetate. Then, the organic layer was washed four times with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. Compound 5b was obtained after purification by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: dichloromethane) as a beige solid in 47% yield (0.17 g). mp 136°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 8.67 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.66–7.55 (m, 3H), 7.39–7.33 (m, 3H), 7.33–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 5.03 (ddd, J = 9.9, 9.4, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (s, 2H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 2.99 (dd, J = 15.1, 9.9 Hz, 1H), 2.93 (dd, J = 15.1, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6) δ: 147.9, 142.3, 138.8, 138.0, 136.5, 134.0, 132.7, 130.9, 129.2 (3C), 129.1 (2C), 129.0 (2C), 128.2, 128.0 (2C), 127.6, 126.0 (2C), 55.3, 52.7, 34.0, 33.9, 20.8. LC/MS ESI+ t R 5.77, (m/z) [M + H]+ 588.82/590.85. HRMS (+ESI): 589.0978 [M + H]+. Calcd for C26H26ClN4O6S2: 589.0977. HPLC purity = 91%.

4.12 Antileishmanial activity against L. infantum promastigotes

L. infantum promastigotes (expressing luciferase activity, kindly provided by Professor Thierry Lang of the Institut Pasteur) were used in the following tests [31]. L. infantum promastigotes were routinely grown at 27°C in Schneider’s Drosophila Medium (Dominique DUTSCHER SAS, France) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2% human urine, sodium pyruvate 0.04 mM, hemin 0.1 µg/mL, HEPES 5 mM, streptomycin 100 µg/mL, penicillin 100 U/mL, l-glutamine 2 mM (culture medium). The effects of the tested compounds on the growth of L. infantum promastigotes were assessed according to the Mosmann protocol [32]. Briefly, promastigotes in log-phase were incubated at an average density of 106 parasites/mL (100 µL/well) in sterile 96-well plates with various concentrations of compounds dissolved in DMSO (final concentration less than 0.5%, v/v), in duplicate. Appropriate controls (100 µL/well) treated by DMSO and reference drugs (purchased for the majority from Sigma Aldrich) were added to each set of experiments. After a 72 h incubation period at 27°C, each plate well was then microscope-examined to detect possible precipitate formation. 20 µL of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Louis, Missouri, USA) solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) were added to each well and incubated at 27°C for 4 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 µL of 50% isopropanol – 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Plates were shaken at 400 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm with a TECAN Infinite F-200 spectrophotometer (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). Efficient concentration 50% (EC50) was defined as the concentration of drug required to inhibit by 50% the metabolic activity of L. infantum promastigotes compared to the control. EC50 values were calculated by non-linear regression analysis processed on dose–response curves, using TableCurve 2D V5 software.

4.13 Cytotoxicity evaluation on HepG2 cell line

HepG2 cell line (hepatocarcinoma cell line purchased from ATCC, ref HB-8065) was maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 with 90% humidity in MEM supplemented with 10% fœtal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine (200 mM) and penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 mg/mL) (complete MEM medium). The tested molecules’ cytotoxicity was assessed according to the method of Mosmann with slight modifications [32]. Briefly, 5 × 103 cells in 100 µL of complete medium were inoculated into each well of 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2. After 24 h incubation, 100 µL of medium with various product concentrations dissolved in DMSO (final concentration less than 0.5% v/v) were added and the plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C. Triplicate assays were performed for each sample. Each plate well was microscope-examined to detect possible precipitate formation before the medium was aspirated from the wells. 100 µL of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) solution (0.5 mg/mL in medium without FCS) were then added to each well. Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, following which the MTT solution was removed and DMSO (100 µL) was added to dissolve the resulting blue formazan crystals. Plates were shaken vigorously (700 rpm) for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm with 630 nm as reference wavelength using a TECAN INFINITE F200 Microplate Reader. DMSO was used as blank and doxorubicin (purchased from Sigma Aldrich) as positive control. Cell viability was calculated as the percentage of control (cells incubated without compound). The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was determined from the dose–response curve using the TableCurve 2D v5.0 software (Jandel Scientific). CC50 values represent the mean value calculated from three separate experiments.

Acknowledgment

We want to thank Dr Vincent Remusat (Institut de Chimie Radicalaire, Marseille) for his help with NMR analysis and Dr Valérie Monnier and Ms Gaëlle Hisler (Spectropole, Marseille) for performing HRMS analysis.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by “Aix-Marseille Université (AMU)”, by “Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS)” and by “Assistance publique - Hôpitaux de Marseille (AP-HM)”.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. NP, PV, NA, PR and PV designed the experiments and RPL, SH and IJ carried them out. RPL and CC-D prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. All co-authors reviewed the manuscript. PR and PV (Patrice Vanelle) led the project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Leishmaniasis [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 19]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Molyneux DH, Savioli L, Engels D. Neglected tropical diseases: progress towards addressing the chronic pandemic. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):312–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30171-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Okwor I, Uzonna J. Social and economic burden of human leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(3):489–93. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0408.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35671. Kirk M, editor. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):951–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31204-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Torres-Guerrero E, Quintanilla-Cedillo MR, Ruiz-Esmenjaud J, Arenas R. Leishmaniasis: A review. F1000Res. 2017;6:750. 10.12688/f1000research.11120.1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Malvolti S, Malhame M, Mantel CF, Le Rutte EA, Kaye PM. Human leishmaniasis vaccines: Use cases, target population and potential global demand. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(9):e0009742. Laouini D, editor. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009742.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Moore E, Lockwood D. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2(2):151. 10.4103/0974-777X.62883.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Winship KA. Toxicity of antimony and its compounds. Adverse Drug React Acute Poisoning Rev. 1987;6(2):67–90.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Frézard F, Aguiar MMG, Ferreira LAM, Ramos GS, Santos TT, Borges GSM, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of leishmaniasis: From the identification of critical physicochemical attributes to the design of effective topical and oral formulations. Pharmaceutics. 2022;15(1):99. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15010099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Maintz EM, Hassan M, Huda MM, Ghosh D, Hossain MdS, Alim A, et al. Introducing single dose liposomal amphotericin B for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in rural Bangladesh: Feasibility and acceptance to patients and health staff. J Trop Med. 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/676817.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Dorlo TPC, Balasegaram M, Beijnen JH, De Vries PJ. Miltefosine: A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2576–97. 10.1093/jac/dks275.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Portfolio | DNDi [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 19]. https://dndi.org/research-development/portfolio/.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Rice AM, Long Y, King SB. Nitroaromatic antibiotics as nitrogen oxide sources. Biomolecules. 2021;11(2):267. 10.3390/biom11020267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Nepali K, Lee HY, Liou JP. Nitro-group-containing drugs. J Med Chem. 2019;62(6):2851–93. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00147.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Löfmark S, Edlund C, Nord CE. Metronidazole is still the drug of choice for treatment of anaerobic infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(s1):S16–23. 10.1086/647939.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Cohen J. Metronidazole to clear intestinal parasites. Lancet. 1996;348(9022):273. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65588-2.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Vanelle P, Crozet M, Maldonado J, Barreau M. Synthèse par réactions SRN1 de nouveaux 5-nitroimidazoles antiparasitaires et antibactériens. Eur J Med Chem. 1991;26(2):167–78. 10.1016/0223-5234(91)90026-J.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Deeks ED. Fexinidazole: First global approval. Drugs. 2019;79(2):215–20. 10.1007/s40265-019-1051-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Patterson S, Wyllie S. Nitro drugs for the treatment of trypanosomatid diseases: past, present, and future prospects. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(6):289–98. 10.1016/j.pt.2014.04.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Fersing C, Basmaciyan L, Boudot C, Pedron J, Hutter S, Cohen A, et al. Nongenotoxic 3-nitroimidazo[1,2-a]pyridines are NTR1 substrates that display potent in Vitro antileishmanial activity. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2019;10(1):34–9. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00347.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Paoli-Lombardo R, Primas N, Bourgeade-Delmas S, Hutter S, Sournia-Saquet A, Boudot C, et al. Improving aqueous solubility and In Vitro pharmacokinetic properties of the 3-nitroimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine antileishmanial pharmacophore. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(8):998. 10.3390/ph15080998.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Paoli-Lombardo R, Primas N, Bourgeade-Delmas S, Sournia-Saquet A, Castera-Ducros C, Jacquet I, et al. Synthesis of new 5- or 7-substituted 3-nitroimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine derivatives using SNAr and palladium-catalyzed reactions to explore antiparasitic structure–activity relationships. Synthesis. 2024;56(8):1297–308. 10.1055/a-2232-8113.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Crozet MD, Botta C, Gasquet M, Curti C, Rémusat V, Hutter S, et al. Lowering of 5-nitroimidazole’s mutagenicity: Towards optimal antiparasitic pharmacophore. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44(2):653–9. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.05.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Spitz C, Mathias F, Péchiné S, Doan THD, Innocent J, Pellissier S, et al. 2,4‐disubstituted 5‐nitroimidazoles potent against Clostridium difficile. ChemMedChem. 2019;14(5):561–9. 10.1002/cmdc.201800784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Giuglio-Tonolo G, Terme T, Médebielle M, Vanelle P. Original reaction of p-nitrobenzyl chloride with aldehydes using tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE). Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44(34):6433–5. 10.1016/S0040-4039(03)01594-6.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Paoli-Lombardo R, Primas N, Castera-Ducros C, Jacquet I, Rathelot P, Vanelle P. N-[1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-{1-methyl-5-nitro-4-[(phenylsulfonyl)methyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl}ethyl]-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide. Molbank. 2023;2023(2):M1633. 10.3390/M1633.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Makosza M, Winiarski J. Vicarious nucleophilic substitution of hydrogen. Acc Chem Res. 1987;20(8):282–9. 10.1021/ar00140a003.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ma̧kosza M, Wojciechowski K. Nucleophilic substitution of hydrogen in heterocyclic chemistry. Chem Rev. 2004;104(5):2631–66. 10.1021/cr020086+.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Sharghi H, Hosseini-Sarvari M, Ebrahimpourmoghaddam S. A novel method for the synthesis of N-sulfonyl aldimines using AlCl3 under solvent-free conditions (SFC). Arkivoc. 2007;2007(15):255–64. 10.3998/ark.5550190.0008.f25.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Michel G, Ferrua B, Lang T, Maddugoda MP, Munro P, Pomares C, et al. Luciferase-expressing leishmania infantum allows the monitoring of amastigote population size, in vivo, ex vivo and in vitro. Milon G, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(9):e1323. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001323.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983;65(1–2):55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine antileishmanial pharmacophore: Design, synthesis, and antileishmanial activity of novel 2,4-disubstituted 5-nitroimidazoles

- Synthesis of a novel water-soluble pyridine dicarboxylate and its application in fluorescence cell imaging

- Synthesis of novel meta-diamide compounds containing pyrazole moiety and their insecticidal evaluation

- Review Articles

- Inorganic nanoparticles promoted synthesis of oxygen-containing heterocycles

- Gold-catalyzed synthesis of small-sized carbo- and heterocyclic compounds: A review

- Synthesis of imidazole derivatives in the last 5 years: An update

- Current progress in the synthesis of imidazoles and their derivatives via the use of green tools

- Synthetic and therapeutic review of triazoles and hybrids

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Structural simplification of the 3‐nitroimidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine antileishmanial pharmacophore: Design, synthesis, and antileishmanial activity of novel 2,4-disubstituted 5-nitroimidazoles

- Synthesis of a novel water-soluble pyridine dicarboxylate and its application in fluorescence cell imaging

- Synthesis of novel meta-diamide compounds containing pyrazole moiety and their insecticidal evaluation

- Review Articles

- Inorganic nanoparticles promoted synthesis of oxygen-containing heterocycles

- Gold-catalyzed synthesis of small-sized carbo- and heterocyclic compounds: A review

- Synthesis of imidazole derivatives in the last 5 years: An update

- Current progress in the synthesis of imidazoles and their derivatives via the use of green tools

- Synthetic and therapeutic review of triazoles and hybrids