Abstract

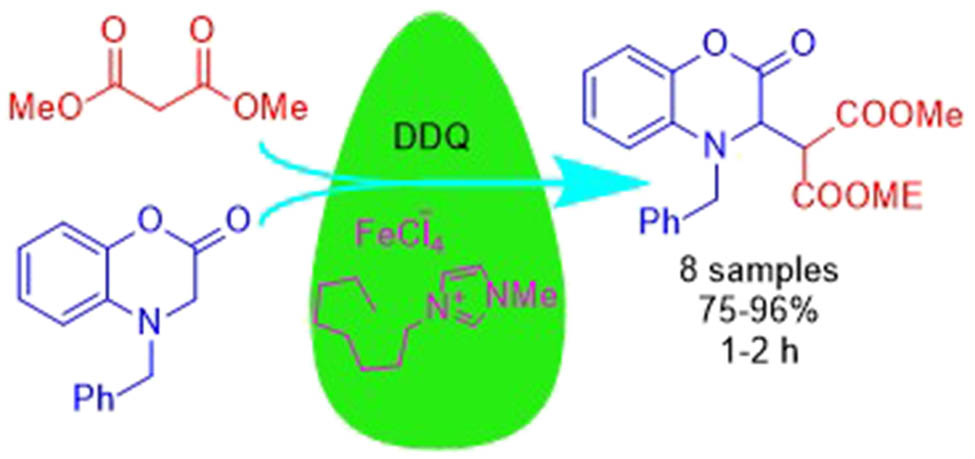

A convenient C(sp3)–C(sp3) oxidative dehydrogenative coupling reaction of 1,4-benzoxazin-2-ones with malonate esters was developed under mild conditions to obtain the respective ester malonates in high yields. Reactions take place in [omim]FeCl4, acting as both the solvent and the catalyst. Under [omim]Cl/FeCl3-DDQ conditions, derivatives of 1 coupled with malonate 2 to give the target molecules within 1–2 h time periods. The ionic liquid was recovered and reused in the next reactions without losing its efficiency.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Enforced by the increasing global demands to implement severe environmentally clean protocols [1], ionic liquids (ILs) have found a wide range of applications in recent decades, as benign surrogates for conventional solvents in research [2,3] and industry [4]. This is due to low vapor pressure, high thermal durability, good shelf storage, and an increased tendency to give homogenized mixtures with various reagents, catalysts, and reactants [5]. Particularly important from the synthetic viewpoint is the improved selectivity and reactivity [6] associated with many organic reactions conducted in ILs [7] through designing appropriate ILs with desired chemical and physical properties for certain transformations [8].

Carbon–carbon (C–C) bond construction is perhaps the most fundamental synthetic process in organic chemistry to access more complex molecules from simpler reactants [9]. The direct coupling of two C–H bonds, known as cross-dehydrogenative-coupling (CDC) reactions [10,11], is one of the most frequently practiced methods for the formation of new C–C moieties due to the wide availability of C–Hs in the structure of various organic reactants [12,13] and a high atom economy that the process inherits [14]. In this context, one-electron oxidative CDC reactions have become one of the fast-growing approaches in recent years [15].

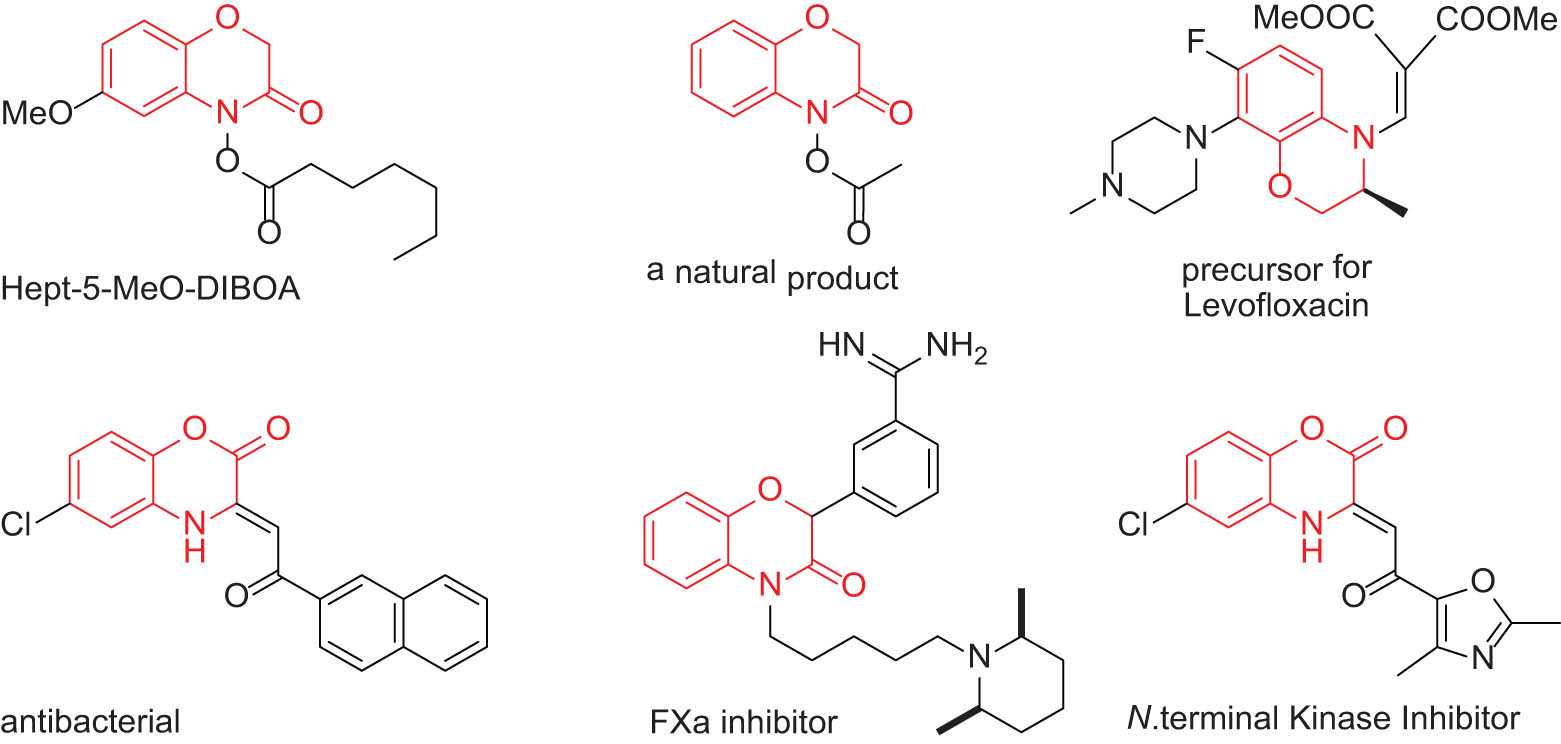

An important group of heterocyclic molecules is 1,4-benzoxazinones [16]. This type of structure can be frequently found in biologically active molecules [17]. Furthermore, there are complex molecules that have 1,4-benzoxazinone skeleton in their structure and possess pharmaceutical [18], optical [19], or biological properties [20,21]. Some related illustrative examples are presented in Figure 1 [22,23,24]. Thus, developing new methodologies for an efficient synthesis and derivatization of benzoxazinones is in high demand in current organic synthesis. In this regard, the C–C coupling approach has been used in recent years by a few groups of researchers via peroxidation of benzoxazinones with tert-butyl hydroperoxide [25], amination of benzoxazinones with dialkyl azodicarboxylates [26], photocatalyzed oxidative coupling of benzoxazinones with a variety of nucleophiles such as indole derivatives [15,27] and other aromatic moieties [16], and coupling reaction of benzoxazinones with malonic esters or ketones [17].

Examples of important 1,4-benzoxazinones structures.

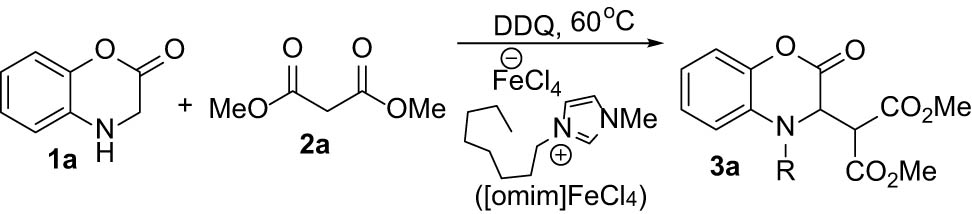

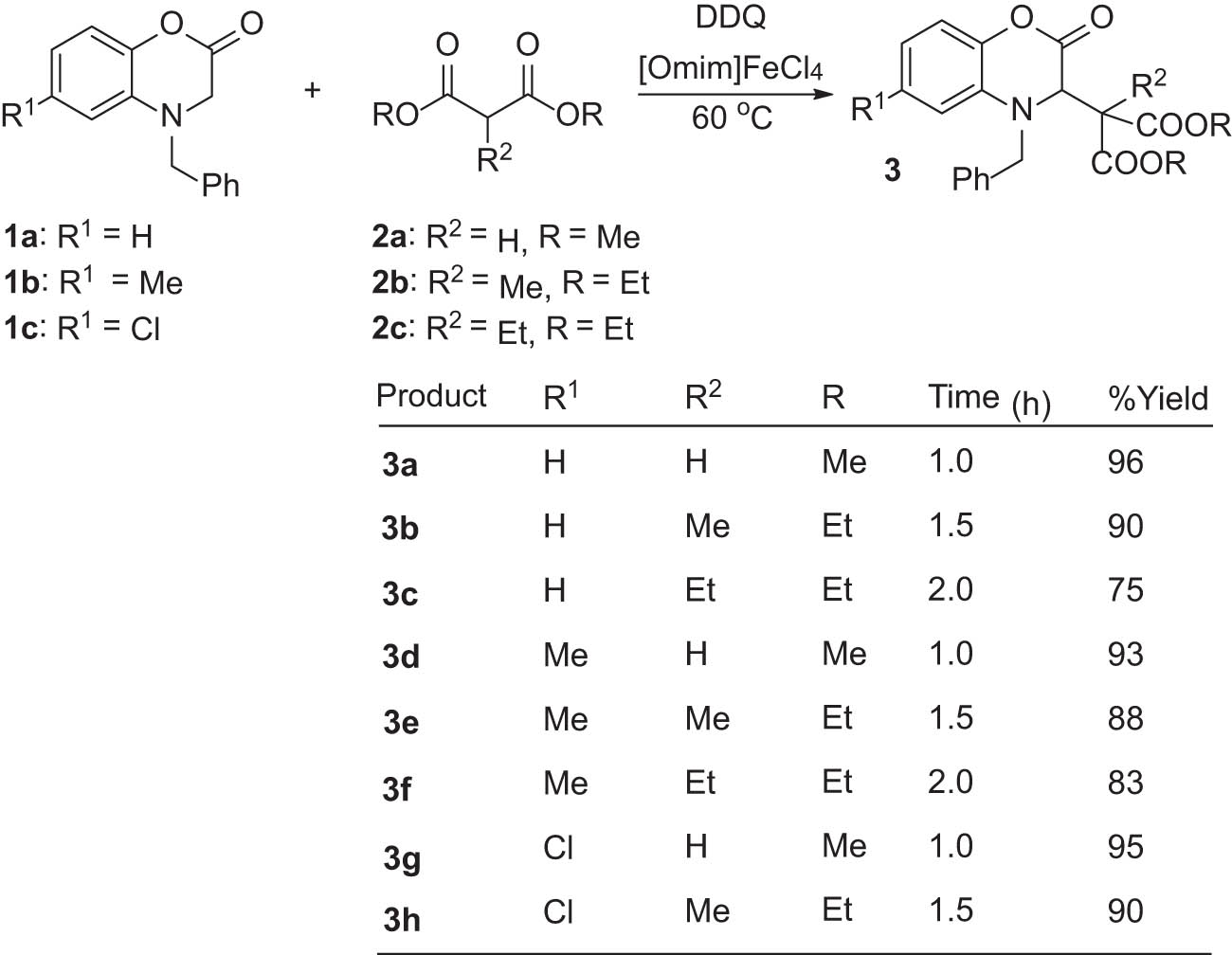

In the framework of our studies to design the IL-mediated procedures in heterocyclic chemistry [28,29], we recently reported a CDC of benzoxazinones with indoles under FeCl3 catalysis in [omim]Cl or by ball milling [30,31]. On this track, now we would like to report a convenient procedure for IL-mediated coupling of 1,4-benzoxazinones with malonate derivatives using [omim]Cl/FeCl3 as the solvent/catalyst of the process, as shown in Scheme 1 for the model reaction of 1a with 2a taking place in the presence of the oxidant DDQ.

CDC coupling of 1a with 2a for the synthesis of 3a.

2 Results and discussion

We first optimized the conditions for the synthesis of 3a as the model reaction (Table 1). The best conditions were obtained when we treated a mixture of 1a and 2a in the presence of [omim]FeCl4 and DDQ at 60°C (entry 1). Thus, 3a was obtained in a 96% yield after 1 h. In the absence of the IL (entry 2) or by the substitution of the IL with an equivalent non-IL catalyst/solvent (entry 3), the yield diminished slightly or partially. Similarly, the reactions at temperatures lower (entry 4) or higher (entry 5) than 60°C did not improve the outcome. The yield of 3a showed to be dependent of the type of the oxidant, with DDQ giving the best conversion (entries 6–13).

Optimization of the reaction conditionsa

| Entry | Catalyst | Oxidant | Temperature (°C) | Yield %b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [omim]FeCl4 | DDQ | 60 | 96 |

| 2 | — | DDQ | 60 | 0 |

| 3 | MeCN/FeCl3 | DDQ | 60 | 70 |

| 4 | [omim]FeCl4 | DDQ | 40 | 55 |

| 5 | [omim]FeCl4 | DDQ | 80 | 73 |

| 6 | [omim]FeCl4 | TBHP | 60 | 0 |

| 7 | [omim]FeCl4 | O2 | 60 | 0 |

| 8 | [omim]FeCl4 | (NH4)2S2O8 | 60 | 20 |

| 9 | [omim]FeCl4 | K2S2O8 | 60 | 27 |

| 10 | [omim]FeCl4 | H2O2 | 60 | 33 |

| 11 | [omim]FeCl4 | Tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone | 60 | 75 |

| 12 | [omim]FeCl4 | 1,4-Benzoquinone | 60 | 87 |

| 13 | [omim]FeCl4 | Benzoyl peroxide | 60 | 90 |

aDDQ (0.5 equiv), IL (1.0 equiv), 60°C, 1 h.

bIsolated yields.

TBHP: tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

Further experiments were conducted for more optimization of the conditions. To compare the performance of other ILs with [omim]FeCl4, the synthesis of 3a was examined in other methylimidazolium-FeCl4-based ILs. As shown in Figure 2a, by a growth in the size of the alkyl substitution of the imidazolium cation, the yield of 3a is increased, perhaps due to the increase in hydrophobicity of the IL and better dissolving the organic reactants (dashed line). On the other hand, FeCl4 served as the best counter ion for [omim] cation (solid line), while the replacement of DDQ with other oxidants (dotted line) did not lead to better results. Figure 2b also shows the results for altering the amount of the DDQ (dotted line) or [omim]FeCl4 (broken line).

![Figure 2

Dependency of the yield of 3a to (a) the change in the type of the oxidant (dotted line) or the anion (solid line) and the cation (dashed line) of the IL and (b) the change in the amount of DDQ (dashed line) or [omim]FeCl4 (solid line).](/document/doi/10.1515/hc-2022-0007/asset/graphic/j_hc-2022-0007_fig_002.jpg)

Dependency of the yield of 3a to (a) the change in the type of the oxidant (dotted line) or the anion (solid line) and the cation (dashed line) of the IL and (b) the change in the amount of DDQ (dashed line) or [omim]FeCl4 (solid line).

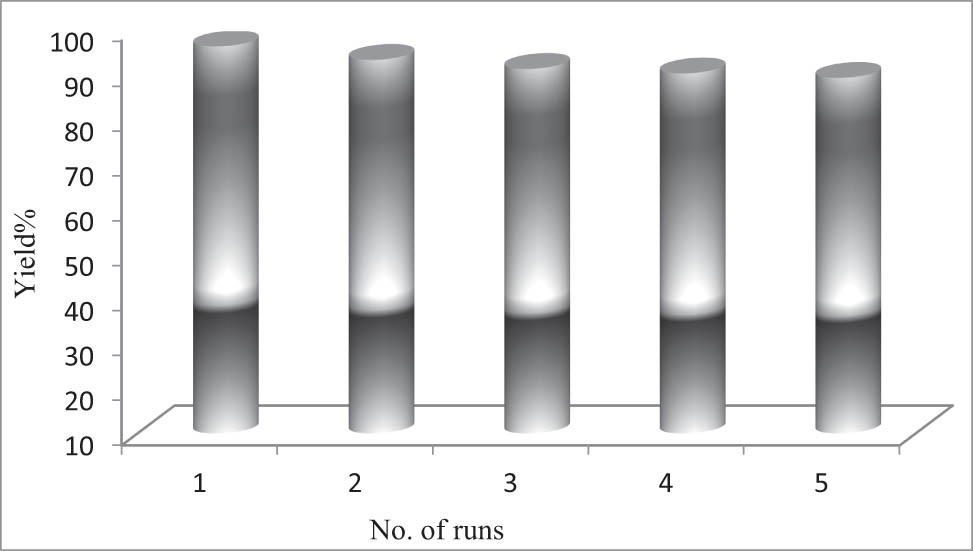

This is important from an environmental point of view to recover solvents, catalysts, or reagents after completion of the reactions and reuse them in subsequent runs. Therefore, after each workup, the product was extracted with ethyl acetate, the IL was recovered by removing the volatile portion under reduced pressure, the medium was remade to its required amounts, and it was recycled in the next reactions successfully. The concept is shown in Figure 3 for five consecutive reuses of the medium without significant loss of its performance.

Successful reuse of the medium.

To evaluate the generality of the method, we then repeated the reaction using other derivatives of 1 and 2 (Scheme 2). As a result, reactions of three standard N-benzyl-benzoxazin-2-one derivatives 1a–c (with different electronic natures) with 2a–c gave the respective products 3a–h in 75–96% isolated yields. The reactions were completed under the optimized conditions, with more sluggish reactants getting slightly longer times.

Synthesis of various derivatives of 3.

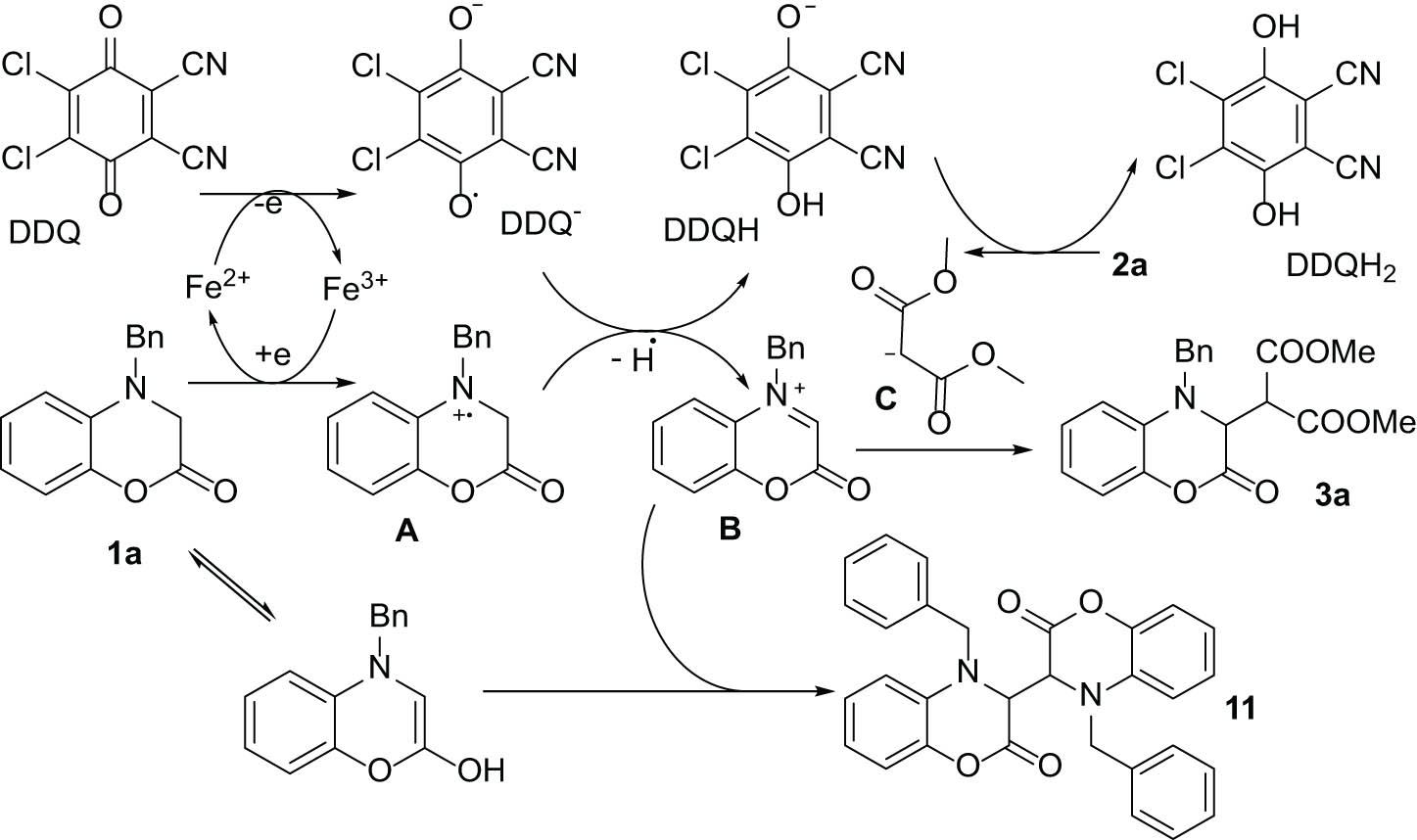

Based on these observations, a mechanism for the coupling can be suggested, as shown in Figure 4 for the reaction of 1a with 2a. The fact that the reaction is an oxidative process is well documented [32]. Thus, primarily 1a is oxidized to its respective radical cation A, while the resulting Fe2+ ion reduces DDQ to DDQ− to maintain the recovery cycle of iron. The loss of a hydrogen atom by A ends up with the formation of B and DDQH. Further reduction of DDQH to DDQH2 by malonate ester 2a provides anion C, which can couple with cation B to give the final product 3a. Isolation of a side product from the reaction mixture, which by 1H NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) analysis corresponds to the structure 11 (dimer of 1a), supports the proposed mechanism. The formation of this dimer suggests that a radical process is involved in this reaction.

A plausible mechanism of the reaction.

3 Conclusion

In summary, we could develop a new procedure for the IL-mediated C(sp3)–C(sp3) oxidative dehydrogenative coupling of 1,4-benzoxazin-2-ones with malonate ester derivatives. The reactions are performed under mild conditions, and the medium, which acts as both the catalyst and the solvent, is successfully recycled several times. The application of the procedure in coupling other reactants is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

4 Experimental

All reagents and solvents were commercially available and used as received. The progress of the reactions was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel-coated plates and ethyl acetate (EtOAc)/petroleum ether mixture as the eluent. Melting points are uncorrected and are obtained by Buchi Melting Point 530. The 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) spectra are obtained on an fourier transform-nuclear magnetic resonance (FT-NMR) Bruker Ultra ShieldTM instrument as CDCl3 solutions, and the chemical shifts are expressed as δ units with Me4Si as the internal standard. ILs were prepared using known procedures [33]. The identity of the known products was confirmed by comparing their melting points and their 1H NMR data with those of authentic compounds available in the literature [17]. New products were characterized based on their spectral data.

4.1 Typical [omim]FeCl4-catalyzed synthesis of 3

DDQ (110 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added to a mixture of dimethyl malonate (2a, 264 mg, 2.0 mmol), 3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-2-one (1a, 239 mg, 1.0 mmol) in [omim]FeCl4 (0.4 g, 1.0 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at 60°C for 1 h. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc (10 mL), and the extract was washed with H2O (15 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was fractionated by column chromatography on silica gel using acetone/hexanes (1:10) as the eluent to afford 3a (355 mg, 96%). The IL, which remains on the top of the column, is collected, diluted with EtOAc (5 mL), and filtered (to remove the silica gel particles). The volatile content is removed under reduced pressure, and the remaining IL is recycled into the next reaction.

5 Spectral data of new products

5.1 Diethyl 2-(4-benzyl-2-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-3-yl)-2-methylmalonate (3b)

White solid in 80% yield: Melting point (M.P.) 77–79°C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.23 (m, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (3, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.0 (s, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (m, 1H), 4.08–3.99 (m, 3H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.5, 169.2, 163.0, 143.4, 139.5, 132.0, 128.8, 127.9, 127.8, 125.1, 121.3, 118.5, 116.5, 63.9, 62.1, 62.0, 59.2, 58.3, 18.5, 13.8, 13.7; mass (MS) (70 eV) m/z (%) 411, 320, 239, 146, 90, 65; infrared (IR) (Potassium Bromide [KBr], cm−1) 3,447, 2,984, 1,732, 1,504, 1,248, 1,104, 746. Anal. Calcd for C23H25NO6: C, 67.14; H, 6.12; N, 3.40. Found: C, 67.25; H, 6.20; N, 3.55.

5.2 Diethyl 2-(4-benzyl-2-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-3-yl)-2-ethylmalonate (3c)

White solid in 75% yield: M.P. 93–95°C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 7.0 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.92 (s, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 4.09–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.99–3.91 (m, 1H), 3.86–3.79 (m, 1H), 3.77–3.70 (m, 1H), 2.18–2.09 (m, 1H), 1.99–1.90 (m, 1H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.16 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.0, 168.8, 162.6, 143.5, 136.6, 131.6, 128.7, 127.6, 127.5, 124.9, 121.4, 119.0, 116.4, 63.6, 62.3, 61.8, 61.6, 58.3, 26.9, 13.77, 13.74, 9.3; MS (70 eV) m/z (%) 425, 239, 209, 160, 119, 90, 65, 41; IR (KBr, cm−1) 2,982, 1,730, 1,504, 1,233, 1,026, 748. Anal. Calcd for C24H27NO6: C, 67.75; H, 6.40; N, 3.29. Found: C, 67.66; H, 6.53; N, 3.41.

5.3 Diethyl 2-(4-benzyl-6-methyl-2-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-3-yl)-2-methylmalonate (3e)

White solid in 88% yield: M.P. 58–60°C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.23 (m, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (s, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.96 (s, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 4.18–4.0 (m, 4H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 1.44 (s, 3H), 1.26–1.21 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.6, 169.2, 163.1, 141.5, 136.7, 134.8, 131.7, 128.7, 127.8, 127.5, 122.1, 119.0, 116.2, 63.6, 62.1, 62.0, 59.2, 58.4, 21.1, 18.4, 13.8, 13.7; MS (70 eV) m/z (%) 425, 356, 302, 300, 91; IR (KBr, cm−1) 2,979, 1,775, 1,726, 1,505, 1,446, 1,249, 1,107, 850, 736. Anal. Calcd for C24H27NO6: C, 67.75; H, 6.40; N, 3.29. Found: C, 67.34; H, 4.44; N, 3.39.

5.4 Diethyl 2-(4-benzyl-6-methyl-2-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-3-yl)-2-ethylmalonate (3f)

White solid in 83% yield: M.P. 71–73°C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32–7.23 (m, 3H), 7.14 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (s, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (s, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 4.09–4.04 (m, 1H), 3.97–3.91 (m, 1H), 3.89–3.84 (m, 1H), 3.78–3.73 (m, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 2.17–2.09 (m, 1H), 1.99–1.91 (m, 1H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.17 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.0, 168.9, 162.8, 141.5, 136.7, 134.6, 131.3, 128.7, 127.8, 127.6, 122.1, 119.5, 116.0, 63.4, 62.3, 61.7, 61.6, 58.4, 26.9, 21.1, 13.75, 13.72, 9.2; MS (70 eV) m/z (%) 439, 348, 252, 174, 132, 91, 65, 43; IR (KBr, cm−1) 2,983, 1,756, 1,721, 1,201, 1,028, 805, 731. Anal. Calcd for C25H29O6: C, 68.32; H, 6.65; N, 3.19. Found: C, 68.40; H, 6.70; N, 3.32.

5.5 Diethyl 2-(4-benzyl-6-chloro-2-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-3-yl)-2-methylmalonate (3h)

White solid in 90% yield: M.P. 113–114°C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.33–7.24 (m, 3H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.82 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 4.75 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 4.55 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 4.19–4.11 (m, 1H), 4.10–3.98 (m, 3H), (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.5 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.25–4.17 (m, 1H), 4.17–4.07 (m, 3H), 1.46 (s, 3H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.4, 169.1, 162.2, 141.8, 136.0, 133.2, 130.1, 128.9, 128.0, 127.3, 120.9, 117.9, 117.4, 63.4, 62.3, 62.2, 59.2, 57.8, 18.6, 13.8, 13.7; MS (70 eV) m/z (%) 445, 272, 149, 91; IR (KBr, cm−1) 2,981, 1,775, 1,724, 1,502, 1,161, 846, 801. Anal. Calcd for C23H24ClNO6: C, 61.95; H, 5.43; N, 3.14. Found: C, 62.11; H, 5.32; N, 3.02.

5.6 4,4′-Dibenzyl-3,3′,4,4′-tetrahydro-2H,2′H-[3,3′-bibenzo[b][1,4]oxazine]-2,2′-dione (11)[16]

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.44–7.29 (m, 5H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.49 (s, 1H), 4.82 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H).

Acknowledgment

The Research Council at CCERCI (Grant # 98-112) is acknowledged for financial support of this work.

-

Funding information: The study was supported by The Research Council at CCERCI (Grant # 98-112).

-

Author contributions: Ali Sharifi has designed the project and supervised the PhD thesis of Maryam Moazami, who has conducted all experiments and synthetic operations. Mohammad Saeed Abaee has served as cosupervisor to Maryam Moazami and written the manuscript. Mojtaba Mirzaei is the Lab supervisor and has conducted some of the spectroscopic analyses.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Shi DQ, Yao H. Facile and clean synthesis of furopyridine derivatives via three-component reaction in aqueous media without catalyst. Synth Commu. 2009;39(14):2481–91.10.1080/00397910802656034Search in Google Scholar

[2] Matsumoto M, Mochiduki K, Fukunishi K, Kondo K. Extraction of organic acids using imidazolium-based ionic liquids and their toxicity to lactobacillus thamnosus. Sep Purif Technol. 2004;40(1):97–101.10.1016/j.seppur.2004.01.009Search in Google Scholar

[3] Jin S-S, Ding M-H, Guo H-Y. Ionic liquid catalyzed one-pot synthesis of spiropyran derivatives via three-component reaction in water. Heterocycl Commun. 2013;19(2):139–43.10.1515/hc-2012-0159Search in Google Scholar

[4] Visser AE, Reichert WM, Swatloski RP, Willauer HD, Huddleston JG, Rogers RD. Characterization of hydrophilic and hydrophobic ionic liquids: alternatives to volatile organic compounds for liquid-liquid separations, in ionic liquids. ACS Symposium Ser. 2002;818(23):289–308.10.1021/bk-2002-0818.ch023Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chan B, Chang N, Grimmett M. The synthesis and thermolysis of imidazole quaternary salts. Aust J Chem. 1977;30(9):2005–13.10.1071/CH9772005Search in Google Scholar

[6] Smirnova SV, Torocheshnikova II, Formanovsky AA, Pletnev IV. Solvent extraction of amino acids into a room temperature ionic liquid with dicyclohexano-18-crown-6. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378(5):1369–75.10.1007/s00216-003-2398-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Prechtl MHG, Scholten JD, Dupont J. Carbon-carbon cross coupling reactions in ionic liquids catalysed by palladium metal nanoparticles. Molecules. 2010;15(5):3441–61.10.3390/molecules15053441Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Legeay J-C, Carrié D, Paquin L, Eynde JJV, Bazureau JP. Synthesis and application of ionic liquid phase-supported β-aminocrotonate for access to asymmetric 1,4-dihydropyridines. Heterocycl Commun. 2009;15(2):91–6.10.1515/HC.2009.15.2.91Search in Google Scholar

[9] Dzik WI, Lange PP, Gooßen LJ. Carboxylates as sources of carbon nucleophiles and electrophiles: comparison of decarboxylative and decarbonylative pathways. Chem Sci. 2012;3(9):2671–8.10.1039/c2sc20312jSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Molnár Á. Efficient, selective, and recyclable palladium catalysts in carbon−carbon coupling reactions. Chem Rev. 2011;111(3):2251–20.10.1021/cr100355bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Dong Z, Liu Y, Zhou CW, Huang JJ, Guo T, Wang Y. Direct cross-dehydrogenative coupling reactions of imidazopyridines and 1-naphthylamines with ethers under metal-free conditions. Synth Commun. 2020;50(13):1972–81.10.1080/00397911.2020.1761394Search in Google Scholar

[12] Yin L, Liebscher J. Carbon−carbon coupling reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous palladium catalysts. Chem Rev. 2007;107(1):133–73.10.1021/cr0505674Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Gensch T, Hopkinson MN, Glorius F, Wencel-Delord J. Mild metal-catalyzed C–H activation: examples and concepts. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45(10):2900–36.10.1039/C6CS00075DSearch in Google Scholar

[14] Colacot TJ, Shea HA. Cp2Fe(PR2)2PdCl2 (R = i-Pr, t-Bu) complexes as air-stable catalysts for challenging Suzuki coupling reactions. Org Lett. 2004;6(21):3731–4.10.1021/ol048598tSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Huo C, Dong J, Su Y, Tang J, Chen F. Iron-catalyzed oxidative sp3 carbon–hydrogen bond functionalization of 3,4-dihydro-1,4-benzoxazin-2-ones. Chem Commun. 2016;52(91):13341–4.10.1039/C6CC05885JSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Zhang G-Y, Yu K-X, Zhang C, Guan Z, He YH. Oxidative cross-dehydrogenative-coupling reaction of 3,4-dihydro-1,4-benzoxazin-2-ones through visible-light photoredox catalysis. Eur J Org Chem. 2018;2018(4):525–31.10.1002/ejoc.201701683Search in Google Scholar

[17] Dong J, Min W, Li H, Quan Z, Yang C, Huo C. Iron-catalyzed C(sp3)−C(sp3) bond formation in 3,4-dihydro-1,4-benzoxazin-2-ones. Adv Synth Catal. 2017;359(22):3940–4.10.1002/adsc.201700816Search in Google Scholar

[18] Sharma R, Yadav L, Lal J, Jaiswal PK, Mathur M, Swami AK, et al. Synthesis, antimicrobial activity, structure-activity relationship and cytotoxic studies of a new series of functionalized (Z)-3-(2-Oxo-2-substituted ethylidene)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-2-ones. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27(18):4393–8.10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.08.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Azuma K, Suzuki S, Uchiyama S, Kajiro T, Santa T, Imai K. A study of the relationship between the chemical structures and the fluorescence quantum yields of coumarins, quinoxalinones and benzoxazinones for the development of sensitive fluorescent derivatization reagents. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2003;2(4):443–9.10.1039/b300196bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Macías FA, Marín D, Oliveros-Bastidas A, Molinillo JMG. Rediscovering the bioactivity and ecological role of 1,4-benzoxazinones. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26(4):478–89.10.1039/b700682aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Macías FA, Marín D, Oliveros-Bastidas A, Chinchilla D, Simonet AM, Molinillo JMG. Isolation and synthesis of allelochemicals from gramineae: benzoxazinones and related compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(4):991–1000.10.1021/jf050896xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Macías FA, Marín D, Oliveros-Bastidas A, Molinillo JMG. Optimization of benzoxazinones as natural herbicide models by lipophilicity enhancement. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(25):9357–65.10.1021/jf062168vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Dudley DA, Bunker AM, Chi L, Cody WL, Holland DR, Ignasiak DP, et al. Rational design, synthesis, and biological activity of benzoxazinones as novel factor Xa inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2000;43(22):4063–70.10.1021/jm000074lSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Dou X, Huang H, Li Y, Jiang L, Wang Y, Jin H, et al. Multistage screening reveals 3-substituted indolin-2-one ferivatives as novel and isoform-selective c-jun N-terminal kinase 3 (JNK3) inhibitors: implications to drug discovery for potential treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. J Med Chem. 2019;62(14):6645–64.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00537Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Wang J, Bao X, Wang J, Huo C. Peroxidation of 3,4-dihydro-1,4-benzoxazin-2-ones. Chem Commun. 2020;56(27):3895–8.10.1039/C9CC09778CSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Rostoll-Berenguer J, Capella-Argente M, Blay G, Pedro JR, Vila C. Visible-light-accelerated amination of quinoxalin-2-ones and benzo[1,4]oxazin-2-ones with dialkyl azodicarboxylates under metal and photocatalystfree conditions. Org Biomol Chem. 2021;19(28):6250–5.10.1039/D1OB01157JSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Akula PS, Hong B-C, Lee G-H. Visible-light-induced C(sp3)–H activation for a C–C bond forming reaction of 3,4-dihydroquinoxalin-2(1H)-one with nucleophiles using oxygen with a photoredox catalyst or under catalyst-free conditions. RSC Adv. 2018;8(35):19580–4.10.1039/C8RA03259ASearch in Google Scholar

[28] Pirouz M, Abaee MS, Harris P, Mojtahedi MM. One-pot synthesis of benzofurans via heteroannulation of benzoquinones. Heterocycl Commun. 2021;27(1):24–31.10.1515/hc-2020-0120Search in Google Scholar

[29] Sharifi A, Hosseini F, Ghonouei N, Abaee MS, Mirzaei M, Mesbah AW, et al. Reactions of 2-aminothiphenols with chalcones in an ionic liquid medium: a chemoselective catalyst-free synthesis of 1,5-benzothiazepines. J Sulfur Chem. 2015;36(3):257–69.10.1080/17415993.2015.1014483Search in Google Scholar

[30] Sharifi A, Moazami M, Abaee MS, Mirzaei M. [Omim]Cl/FeCl3-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative-coupling of 1,4-benzoxazinones with various indoles. J Iran Chem Soc. 2020;17(10):2471–80.10.1007/s13738-020-01941-ySearch in Google Scholar

[31] Sharifi A, Babaalian Z, Abaee MS, Moazami M, Mirzaei M. Synergistic promoting effect of ball milling and Fe(II) catalysis for cross-dehydrogenative-coupling of 1,4-benzoxazinones with indoles. Heterocycl Commun. 2021;27(1):57–62.10.1515/hc-2020-0123Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hu YP, Tang RY. TBHP-mediated oxidative cross-coupling of disulfides with ethers through a C(sp3)-H thiolation process. Synth Commun. 2014;44(14):2045–50.10.1080/00397911.2014.888081Search in Google Scholar

[33] Jain R, Sharma K, Kumar D. Ionic liquid mediated 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethine ylides: a facile and green synthesis of novel dispiro heterocycles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53(15):1993–7.10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.02.029Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Ali Sharifi et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Sono and nano: A perfect synergy for eco-compatible Biginelli reaction

- Study of the reactivity of aminocyanopyrazoles and evaluation of the mitochondrial reductive function of some products

- “Click” assembly of novel dual inhibitors of AChE and MAO-B from pyridoxine derivatives for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Synthesis of 2,2-difluoro-2-arylethylamines as fluorinated analogs of octopamine and noradrenaline

- Cyclization of N-acetyl derivative: Novel synthesis – azoles and azines, antimicrobial activities, and computational studies

- Two independent and consecutive Michael addition of 1,3-dimethylbarbituric acid to (2,6-diarylidene)cyclohexanone: Flying-bird-shaped 2D-polymeric structure

- Ionic liquid-catalyzed synthesis of (1,4-benzoxazin-3-yl) malonate derivatives via cross-dehydrogenative-coupling reactions

- Synthesis of novel triiodide ionic liquid based on quaternary ammonium cation and its use as a solvent reagent under mild and solvent-free conditions

- Eelectrosynthesis of benzothiazole derivatives via C–H thiolation

- Synthesis of fluoro-rich pyrimidine-5-carbonitriles as antitubercular agents against H37Rv receptor

- Syntheses, crystal structure, thermal behavior, and anti-tumor activity of three ternary metal complexes with 2-chloro-5-nitrobenzoic acid and heterocyclic compounds

- Synthesis of enhanced lipid solubility of indomethacin derivatives for topical formulations

- Synthesis of newer substituted chalcone linked 1,2,3-triazole analogs and evaluation of their cytotoxic activities

- Novel benzodioxatriaza and dibenzodioxadiazacrown compounds carrying 1,2,4-oxadiazole moiety

- Synthesis of rhodium catalysts with amino acid or triazine as a ligand, as well as its polymerization property of phenylacetylene

- DABCO-based ionic liquid-promoted synthesis of indeno-benzofurans derivatives: Investigation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities

- Design, synthesis, and biological activity of novel pomalidomide linked with diphenylcarbamide derivatives

- Study on effective synthesis of 7-hydroxy-4-substituted coumarins

- Review Article

- Chemical constituents of plants from the genus Carpesium

- Communication

- Reactions of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazine with coupling reagents and electrophiles

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Sono and nano: A perfect synergy for eco-compatible Biginelli reaction

- Study of the reactivity of aminocyanopyrazoles and evaluation of the mitochondrial reductive function of some products

- “Click” assembly of novel dual inhibitors of AChE and MAO-B from pyridoxine derivatives for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Synthesis of 2,2-difluoro-2-arylethylamines as fluorinated analogs of octopamine and noradrenaline

- Cyclization of N-acetyl derivative: Novel synthesis – azoles and azines, antimicrobial activities, and computational studies

- Two independent and consecutive Michael addition of 1,3-dimethylbarbituric acid to (2,6-diarylidene)cyclohexanone: Flying-bird-shaped 2D-polymeric structure

- Ionic liquid-catalyzed synthesis of (1,4-benzoxazin-3-yl) malonate derivatives via cross-dehydrogenative-coupling reactions

- Synthesis of novel triiodide ionic liquid based on quaternary ammonium cation and its use as a solvent reagent under mild and solvent-free conditions

- Eelectrosynthesis of benzothiazole derivatives via C–H thiolation

- Synthesis of fluoro-rich pyrimidine-5-carbonitriles as antitubercular agents against H37Rv receptor

- Syntheses, crystal structure, thermal behavior, and anti-tumor activity of three ternary metal complexes with 2-chloro-5-nitrobenzoic acid and heterocyclic compounds

- Synthesis of enhanced lipid solubility of indomethacin derivatives for topical formulations

- Synthesis of newer substituted chalcone linked 1,2,3-triazole analogs and evaluation of their cytotoxic activities

- Novel benzodioxatriaza and dibenzodioxadiazacrown compounds carrying 1,2,4-oxadiazole moiety

- Synthesis of rhodium catalysts with amino acid or triazine as a ligand, as well as its polymerization property of phenylacetylene

- DABCO-based ionic liquid-promoted synthesis of indeno-benzofurans derivatives: Investigation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities

- Design, synthesis, and biological activity of novel pomalidomide linked with diphenylcarbamide derivatives

- Study on effective synthesis of 7-hydroxy-4-substituted coumarins

- Review Article

- Chemical constituents of plants from the genus Carpesium

- Communication

- Reactions of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazine with coupling reagents and electrophiles