Abstract

The right clause edge links the utterance to the larger discourse and supports interlocutors in navigating the communicative situation, making such linguistic alternatives prime candidates to be exploited for register distinction. We investigate whether right-peripheral subjects behave similar with respect to registers in the verb-final languages German and Persian, using the multi-lingual Lang*Reg corpus (Adli, Aria, Elisabeth Verhoeven, Nico Lehmann, Vahid Mortezapour & Jozina Vander Klok. 2023. Lang*Reg: A multi-lingual corpus of intra-speaker variation across situations. Version 0.1.0. Zenodo), which includes intra-speaker variation for six communicative situations differentiated by interactivity (monologue vs. dialog), social distance (close vs. distant), social hierarchy (equal vs. unequal) and mode (spoken vs. written). We identified four formal types of right-peripheral subjects: extraposition, right dislocation, afterthought + pronoun correlate and afterthought + NP correlate. Our analysis of the functions of these types across languages revealed that Persian extraposition and German right dislocation behave functionally similar whereas German extraposition is highly restricted and no Persian right dislocation could be found. The corpus analysis reveals that Persian and German speakers used the right periphery more often in interactive in contrast to monological communicative events.

1 Introduction

Language users employ different linguistic means depending on the situation-functional context in order to navigate not only the communicative space but also the socio-cultural space. This intra-individual variation in linguistic behaviour serves to address the communicative needs of the situation, resulting in socially recurring varieties or codes with particular co-occurrences of linguistic phenomena and situational-functional parameters, i.e. registers (Biber 2012; Biber and Conrad 2019; Biber et al. 2021; Lüdeling et al. 2022). Typologically, registers may turn out to exhibit distinct characteristics given that “[t]he situation may determine which code one selects, but the social structure determines which codes one controls” (Halliday 1978: 66), which means register variation may differ across languages due to socio-cultural as well as linguistic differences.

Several findings show that clause peripheries are perceptible to be exploited for register variation. Geluykens (1992: 34) presents corpus data in which the rate of left dislocation is highest in English conversational spoken contexts and decreases the more conceptually written a text is (for the conceptual spoken-written distinction, see in particular Koch and Wulf 1985; Maas 2006). Likewise, Tizón-Couto (2012: 366) notes a rise in the rate of left dislocation in English written texts when they are conceptually more spoken. With respect to the right periphery, Aijmer (1989: 137) observes that it is a phenomenon of “natural speech”. According to Rodman (1997: 47), in English “[r]ight dislocations occur almost entirely in casual, relaxed speech, where they are fairly common” (see also Aijmer 1989: 137). Erguvanli (1984: 67) makes a complementary observation for the verb-final language Turkish, where right-peripheral elements are “extremely” infrequent in conceptually written contexts, including legal documents, newspapers but also scripted oral news or radio and TV. Erguvanli (1984) argues that this is because the function of the right periphery in Turkish is to background information, which requires referents to be salient from the previous discourse, making it less suitable in the conceptually written mode with an informational focus, e.g. news articles (see on informational focus e.g. Biber 1995) where the focus tends to be on new information rather than continuing referents (Erguvanli 1984: 67). If this is the case, then the occurrence of elements in the right periphery in Turkish is not a pure stylistic choice, but based on a functional, pragmatic motivation in relation to the discourse requirements.

More specialized registers also seem to rely more strongly on the right periphery, as found by Levin and Marcus (2019: 257–258) for English, German and Swedish. In a corpus study comparing live football commentaries in all three languages, they observed that the right periphery was used ten times more often than in normal conversations while the use of the left periphery was not affected by the context. They assert that the right periphery receives its register-relation, i.e. its higher likelihood to appear in live football commentaries, for discourse functional reasons (2019: 253). After identifying three purposes for the use of right-peripheral elements, i.e. 1) resolving referential ambiguity, 2) emphasis and 3) adding information (2019: 259), they conclude from their counts that the right periphery is mostly used to disambiguate referents in live football commentaries “caused by mismatches between what is referred to in the verbal commentary and what is shown on the TV screen at the time of speaking” (2019: 265).

In view of these observations, it seems prudent to investigate the right periphery in a more varied set of communicative situations to better understand which situational-functional parameters motivate language users to make use of the right periphery in different situations. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no in-depth study comparing the use of the right periphery across multiple communicative situations across languages. Also, the data from previous studies relied either on introspection for more syntactic-theoretic works (e.g. Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020; Frey 2005; Ott and de Vries 2016) or productions of different speakers in the same situation (e.g. Aijmer 1989; Selting 1994; Vinckel 2006) or varying only by modality (e.g. Frommer 1981; Herring 1994). Data from the same speaker in different situations, on the other hand, would allow us to see directly how language users adapt to the communicative context.

The Lang*Reg corpus (Adli et al. 2023; Lehmann et al. 2025) offers the opportunity to investigate register variation across languages and cultural contexts as it represents language production of the same speakers in different communicative situations, containing spontaneous and natural conversations in several languages. In the present study we concentrate on two languages and cultural contexts, i.e. Persian (Indo-European: Indo-Iranian) as spoken in the city of Tehran and German (Indo-European: West Germanic) as spoken in the city of Berlin. Persian and German provide interesting typological, socio-cultural and ecological distinctions but also similarities that make them an interesting pair for comparative register research. For instance, both languages are used in environments with similar community sizes, a high degree of literacy as well as rich written traditions, which enables language users to experience a range of situational–functional constellations, making both languages pertinent for a high degree of register variation. German and Persian still appear to differ in their register range, for Persian has been described as having a sharper distinction between formal and informal registers, sometimes characterized as a diglossic situation (Ferguson 1959; Modaressi-Tehrani 1978).

Linguistically, both German and Persian are verb-final languages that mark the core clause boundary with a clause-final verbal complex, yet as in many verb-final languages, speakers do still regularly place phrases after the verbal complex (see overview in Pregla 2023: Chapter 5; and on OVX properties with respect to post-verbal obliques Hawkins 2008: 169).[1] Such phrases as, for instance, the subjects marked in bold in (1) appear in the right periphery, sometimes accompanied by a reduced coreferent element in a position preceding the verbal complex, i.e. a correlate, as in the German example in (1a) but not necessarily as shown for Persian in (1b). The clause peripheries serve a variety of purposes for language users but have generally been described as information-structuring devices that anchor the utterance in the larger discourse and support interlocutors in navigating the communicative situation (Beeching and Detges 2014; Frey 2005). This discourse-functional configuration of the peripheries further motivates its use for register distinction. This begs the question whether the right periphery is employed for register distinctions in Persian and German and if so in what way linguistic or socio-cultural differences lead to varying relations of the right periphery to registers in the two languages.

| Die | ist | auch | nie | wiedergekommen | die | Frau . |

| dem.3sg.fem | is | also | never | returned | the.nom | woman |

| ‘She also never came back the woman.’ | ||||||

| (Selting 1994: 308) | ||||||

| xeyli | rɒked-e | kɒr-e-ʃun |

| very | stagnant-be.3sg | work-ez-3pl |

| ‘Their work is very stagnant.’ | ||

| (Frommer 1981: 141) | ||

In this paper, we analyze subjects in the right periphery of Persian and German in an explorative comparative corpus study using the Lang*Reg corpus to examine different situations. To do so, we first define the phenomenon of right-peripheral subjects and the boundaries of the right periphery in Section 2, for which we initially adopted a naive look at the periphery so that we can examine all right-peripheral subjects following the verbal complex in both languages. Section 3.1 provides a more detailed look at the Lang*Reg corpus and the situational-functional characteristics of the situations involved. In Section 3.2, we present the methodology for extracting right-peripheral subjects and analysing each occurrence using the criteria explicated in Section 2. In Section 3.3, we present our findings for the periphery overall (see Section 3.3.1) and for subtypes of right-peripheral subjects (see Section 3.3.2), followed by a discussion of the behaviour of subjects in the right periphery in Persian and German in Section 4.

2 Features of the right periphery

We generously define the right periphery in German and Persian as the space to the right of the clause-final verbal complex (Imo 2014: 340; see similarly about syntactic closure before so-called increments Auer 2006: 285), thereby including any clause-related subjects[2] following this complex (henceforth rXP), and taking into account the relevant features reported in the literature for analysis. The verbal complex is presumably located at the end of the core clause in verb-final languages such as German and Persian and hosts verbal elements such as finite[3] and non-finite verbs, verb particles and predicatives (see discussion in Becker 2016: 235). We consider as right-peripheral subjects any non-sentential[4] subject that appears in the right periphery. The structure in (2) shows that, resulting from this definition, there are three possible target locations for rXPs. They may appear inside the core clause to the right of the verbal complex (VC) as in XP1, for example when a verb-final language has a dedicated clause-internal post-verbal position. They may appear outside of the core clause as with XP2 while still being integrated in the clause. Finally, the rXP may be located completely outside of the clause proper as seen for XP3.

| [[ … [V] vc rXP1] core rXP2] clause rXP3 |

The three potential rXP host locations presented in (2) are indeed attested for subjects, though not necessarily in every language (see e.g. for Spanish and German: Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020; Tamil: Herring 1994; English: Mittendorfer 2025; Japanese: Nakagawa et al. 2008): the core-internal rXP is labelled a case of extraposition as demonstrated with examples from the Lang*Reg corpus in (3), the core-clause-external but integrated rXP is an instance of right dislocation (RD) as shown in (4) and the clause-external subject rXP is referred to as afterthought (AT),[5] illustrated in (5).

| Extraposition (ExtrP) |

| German6 | |||||||||

| und | da | saß | mir | in | der | U-Bahn | gegenüber | Patrick | Swayze |

| and | there | sat | me | in | the | subway | across | Patrick | Swayze |

| ‘and there Patrick Swayze sat across from me in the subway’ | |||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | |||||||||

- 6

A pronoun is not possible in the middle field in this example without changing the intonation contour, which would effectively alter the clause and turn it into a right dislocation.

| Persian | |||||

| tu | rustɑje | fin | ast | xɑne | moallem-aʃ |

| in | village | Fin | is | house | teacher-poss.3sg |

| ‘Its Teacher’s Association is in village Fin.’ | |||||

| [Lang*Reg-Per] | |||||

| Right dislocation: German (RD)7 | ||||||

| die | interagiern | nich | so | richtig | die | Pflanzen |

| they | interact | not | so | properly | the | plants |

| ‘they don’t interact that properly the plants’ | ||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | ||||||

- 7

No example that fulfils the criteria for right dislocation was found in the Persian subcorpus of Lang*Reg.

| Afterthought (AT) |

| German | |||||

| das | ist | mir | wichtig | dieses | Verständnis |

| that | is | me | important | this | understanding |

| ‘It’s important to me, this understanding’ | |||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | |||||

| Persian | ||||||

| mɒ | jek | t͡ʃ ɒdor | dɒʃtim | mæn | væ | mɒmɒn-æm |

| we | one | tent | had.1pl | I | and | mom-poss.1sg |

| ‘We had a tent, me and my mom.’ | ||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Per] | ||||||

Extraposition is analysed as rightward movement, as shown by the structure given in (6a) where the rXP resides inside the core clause and leaves a trace preverbally (Drummond 2009: 43; Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019: 294; Ott and de Vries 2016: 665). RD and AT – involving elements external to the core clause – are assumed to form a biclausal structure as in (6b) and (6c), where the core clause of CP1 is complete even without the rXP since the correlate fills the argument slot of the predicate; CP2 is an elliptical root clause coordinated with CP1 having a clause structure parallel to CP1 except that the rXP is fronted while all parallel material is deleted (following the analysis presented by Ott and de Vries 2016: 645–646). RD and AT differ in their connection to CP1, i.e. RD is more tightly connected to CP1 as shown in (6b) where the clause boundary follows the dislocated XP while AT is completely independent and falls outside of the clause boundary as illustrated in (6c). In the following, the differentiating formal characteristics of rXP types will be reviewed, which informs the subsequent operationalization for the cross-linguistic investigation of right-peripheral subjects.

| [[ CP1 … t i …V rXP i ] core ] clause |

| [[ CP1 … correlate … V ] core [ CP2 rXP i [… t i …]] ] clause |

| [[ CP1 … correlate … V ] core ] clause [ CP2 rXP i [… t i …]] |

Extraposition sets itself apart from the other rXP types with respect to the availability of a correlate in the core clause. No correlate can accompany an extraposed phrase (Altmann 1981: 68; Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020: 2) whereas RD and AT require there to be a correlate in the core clause that is associated with the rXP (Altmann 1981: 54; Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019: 294; Selting 1994: 309; Westbury 2016: 23). The correlate that fills the core clause slot of the subject in (6b) and (6c) may be a free pronoun, a clitic or a covert pro when language-internal mechanisms allow for dropping proforms (Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020: 2; Lambrecht 2001: 1051; Ott and de Vries 2016: 642). In the case of dislocation, the form of overt correlates is limited to language-specific minimal unaccented pro-forms, for example a weak d-pronoun in German (Shaer and Frey 2004: 469; see also Altmann 1981: 55; Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020: 5; Frey 2005: 91; Ott and de Vries 2016: 643). ATs are not restricted as to the kind of correlate, allowing pronouns and full nominal phrases (Ott and de Vries 2016: 643). This contrasts with referential constraints on dislocated rXPs (see on German: Altmann 1981: 54; Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 231, 2008b: 412; see for similar restrictions on left dislocation across languages: Westbury 2016: 23) and in some languages also extraposed rXPs (see e.g. for Turkish: Erguvanli 1984: 45; see across languages: Pregla 2023: 182). They generally must be definite and specific or kind-referring if generic (Averintseva-Klisch and Sebastian 2019: 35) but not quantified XPs (Averintseva-Klisch 2008b: 412; Ott and de Vries 2016: 668). We can distinguish two subtypes of ATs based on the form of their correlate, i.e. ATs with a pronoun (5) versus a full nominal phrase (7) correlate,[8] as these also correspond to different basic functions: ATs with a pronoun correlate tend to clarify the referent due to some ambiguity or (perceived) lack of saliency whereas ATs with a nominal correlate in addition elaborate on further qualities of the referent (see about elaboration strategies Pfeiffer 2015: 42, 53).

| Afterthought: NP correlate (AT.NP) |

| German | ||||||||

| und | dann | war | halt | dieser | Strand | da | der | Atlantikstrand |

| and | there | was | just | this | beach | there | the | atlantik.beach |

| ‘and there was this beach, the atlantik beach’ | ||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | ||||||||

| Persian | ||||||

| bɒft-æʃ | jek | d͡Ʒurhɒi | mesle | tehrɒn | æst | bɒfte |

| structure-poss.3sg | a | kinds | like | Tehran | is | structure |

| ʃæhri-jæʃ | ||||||

| city-poss.3sg | ||||||

| ‘Its structure is somehow like Tehran, its urban structure’ | ||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Per] | ||||||

Dislocated rXPs must match morphologically with the correlate in gender, case and number (Altmann 1981: 55; Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 227, 2008b: 403; Ott and de Vries 2012: 126; Selting 1994: 307; Shaer and Frey 2004: 470). They allow islands (Shaer and Frey 2004: 471) and can be bound (see for the left periphery: Frey 2005: 92; Shaer and Frey 2004: 472; see for the right periphery Ott and de Vries 2012: 127). Moreover, just like extraposed rXPs, they strictly follow their host clause and don’t allow intervening material such as subordinate clauses or other finite boundaries (Altmann 1981: 54; Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 229; Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020: 5) or introductory discourse markers such as that is or I mean (Altmann 1981: 68; Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 228). ATs are more independent. Such external rXPs do not require morphological congruency with the correlate. They can be introduced by discourse markers (Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 228; Pfeiffer 2015: 161) and may include discourse particles and sentence adverbs (Ott and de Vries 2016: 647). The order of dislocated rXPs and ATs is also restricted: dislocated rXPs are closer to the host clause and ATs follow them in the right periphery (Ott and de Vries 2016: 676; Shaer and Frey 2004: 495). In addition, ATs in the right periphery may have different illocutionary force and constitute separate speech acts (Ott and de Vries 2016: 647–648; Truckenbrodt 2015: 332).

Dislocated rXPs and ATs are often not easily distinguishable by morphological and syntactic surface criteria (Selting 1994: 300) because ATs also often display morphological congruency and lack intervening phrases. Prosody is often considered the primary differentiating feature instead (Ott and de Vries 2012: 124; Selting 1994: 300).[9] RD forms a single intonation contour with the host clause (Auer 2006: 286; Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 227, 2008b: 401–402; Selting 1994: 300; Ziv 1994: 639) while AT shows several cues marking it as prosodically independent with a separate intonation contour (Westbury 2016: 23). ATs have an independent pitch accent and a rise in intensity as well as a (potential) preceding pause (Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 227, 2008b: 402; Ott and de Vries 2012: 124; Truckenbrodt 2015: 327). They can be independently stressed (Ott and de Vries 2016: 644; Ziv 1994: 639), though they tend to only receive a slight stress (Herring 1994: 126). With AT, the host clause generally behaves prosodically as if there was no peripheral element, with a pitch usually at the end of the core clause (Auer 1991: 146) and a rise in intensity (Nakagawa et al. 2008: 6).

Dislocated rXPs, in contrast, receive no stress. Instead, the tone movement of the core clause, where the main pitch accent and the focus is located, is continued, resulting in a low and level intonation for the dislocated rXP (Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 227, 2008b: 401–402; Erguvanli 1984: 44; Ott and de Vries 2012: 124; Selting 1994: 300; Truckenbrodt 2015: 329; Ziv 1994: 639). Extraposition displays a characteristic hat contour, meaning that the extraposed rXP attracts the main pitch (Altmann 1981: 68; Auer 1991: 146; Ott and de Vries 2016: 644). Extraposed rXPs neither have their own tone movement as ATs, nor follow the pitch accent in the core clause with a low intonation as dislocated rXPs, but instead shift the prosodic ending of the core clause intonation, carrying the nuclear focus (Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019: 296).

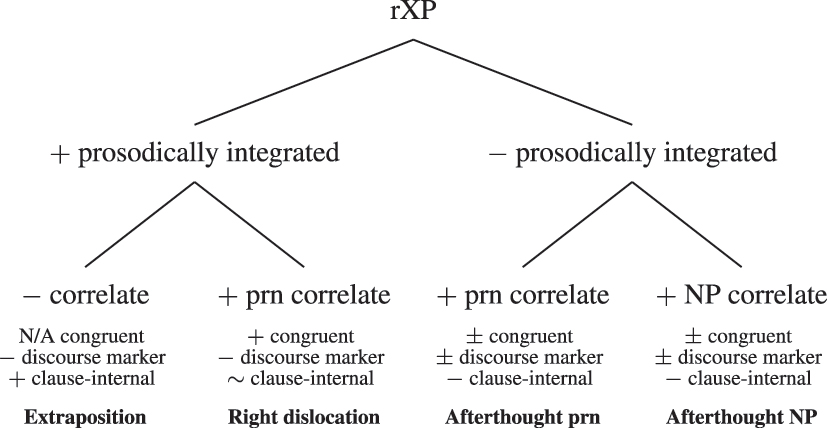

Following from these observations, we operationalized the formal aspects of rXPs in order to analyse corpus occurrences by a minimal set of criteria with which we can identify different types of right-peripheral subjects. The taxonomy in Figure 1 illustrates the operationalization of the four formal types of rXPs identified, which are distinguished using three primary criteria and a set of secondary criteria. Prosodic integration differentiates clause-internal rXPs, i.e. extraposed and dislocated rXPs, from clause-external AT.prn and AT.NP.[10] The form of the correlate then sets the four rXP types apart: extraposition does not allow a correlate while RD requires it (compare (6a) and (6b)); external rXPs differ in that AT.prn has a pronoun correlate and AT.NP has a nominal correlate.

Taxonomy illustrating the deconstruction and operationalization of formal aspects of rXPs.

German and Persian fundamentally differ in these properties for right-peripheral subjects. German has been reported to place subjects in all three syntactic locations seen in (2) (Altmann 1981; Truckenbrodt 2016). No examples have been attested in the literature for Persian RD, however, in which an overt correlate is possible. Clause-internal rXPs rather show properties of extraposition, for instance not allowing a correlate as illustrated in (8a) compared to German RD in (8b), which requires a (potentially covert) correlate.

| Persian: clause-internal subject with infelicity of co-referential pronoun | |||||

| (*u) | tænhɒ | zendeɡi | mi-kærde | mæɣtul | tu-je |

| 3sg | alone | life | prog-do.pst.3sg | murdered | in-gen |

| xunæ-ʃ? | |||||

| house-poss.1sg | |||||

| ‘Did the murdered live alone in his house?’ | |||||

| [SGS] | |||||

| German: clause-external subject with co-referential pronoun | ||||||||

| die | hann | alles | in | die | garage | geta | die | männer |

| they | have | all | in | the | garage | put | the | men |

| ‘They put everything in the garage the men.’ | ||||||||

| [FOLK151] | ||||||||

Moreover, Persian integrated rXPs can carry informational focus as in (9b), in which the subject æli ‘Ali’ in the right periphery specifies the referent asked about in the preceding question (9a). Without the rXP, the core clause would be incomplete, which points towards a movement analysis of the rXP. A dislocated rXP is only felicitous when the core clause is complete by itself, i.e. an RD analysis would require there to be a covert subject pronoun correlate in (9b), which, however, is not acceptable when the subject referent is the new information.

| ketɒb-o | æz | koʝɒ | ɒvord-i? |

| book-om | from | where | brought-2sg |

| ‘Where did you get the book from?’ | |||

| be-hem | ɣærz-eʃ | dæd | æli |

| to-me | lend-it | gave-3sg | Ali |

| ‘Ali lent it to me.’ | |||

In German, extraposed arguments have been reported, for instance with respect to focused postverbal objects (Coniglio and Schlachter 2015: 148). However, Féry (2015: 28) argues that extraposed nominal arguments, i.e. core clause internal without a (covert) correlate as in (10), are infelicitous, yet we do find examples in corpora as with the focused subject extraposition in (11) and German native speakers also have different intuitions about cases as in (10) depending on the context of use. These cases are, however, highly marked (Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019: 304).

| # Anna | hat | ihrer | Mutter | erzählt | die | Geschichte . |

| Anna | has | her | mother | told | the | story |

| ‘Anna has told her mother the story.’ | ||||||

| (Féry 2015: 28) | ||||||

| weil | sich | halt | so | selbstständig | gemacht | hat | der | ganze | Kram |

| because | self | just | so | independent | made | has | the | whole | stuff |

| ‘because all the stuff has taken on a life of its own’ | |||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | |||||||||

German thus appears to be restricted when it comes to extraposition in that nominal arguments, both subjects and objects, are syntactically “blocked” while this is not the case for sentential arguments or obliques (Féry 2015: 35). Hartmann (2017: 99) postulates that extraposed PPs in German are high rightward moved (see similarly Truckenbrodt 2016: 20) and adjoined above vP/IP and Drummond (2009: 47) proposes that extraposed DPs are generally rightward moved to a position lower than vP. Rightward movement to a position lower than vP then appears to be highly restricted in German and if it occurs, it must be triggered by strong information-structural features such as focus (see e.g. Pregla 2023: 168). In Persian, extraposed nominal arguments are more readily accepted (Rasekh-Mahand and Ghiyasvand 2014) and do not carry focus, though they are still information-structurally marked (see Rasekh-Mahand and Mousavi 2007; Rezaei and Tayeb 2005). This points towards movement of nominal arguments in Persian to the postverbal position (Pregla 2023: 168), yet to date no analysis has been presented on the Persian syntax of extraposition. It seems, however, that Persian either does not have the same restriction on low rightward movement as German or allows high rightward movement of DPs in contrast to German.

3 Comparative analysis of the right periphery

With the definition of right-peripheral subjects and their categorization into four formal types (see Section 2), we now have the prerequisites to study register variation in the right periphery for the languages German and Persian. To investigate the effect that the situational-functional context has on the use of the right periphery, we conducted a corpus study of right-peripheral subjects using the Lang*Reg corpus, which contains intra-individual data with respect to several situational-functional contexts in both Persian and German (see description in Section 3.1).

The right periphery is said to help navigate the interpersonal space in particular for dialogic discourse via signals such as confirmation and providing an orientation for the following discourse, i.e. inviting a response or anticipating what comes next (Beeching and Detges 2014: 11; Degand and Crible 2021: 25; Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019: 297). In addition, the right periphery may serve to pick up and highlight overarching discourse concerns such as a (preceding) discourse topic[11] (Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019: 297). As register is the clustering of linguistic phenomena in particular situational–functional contexts due to their communicative functions, we expect the right periphery to be sensitive to register differences because of the functions that right-peripheral elements play in discourse. Apart from a general function of the right periphery, types of rXPs also have more specific functions such as (discourse) topic marking, including topic shift and promotion or demotion of referents, but also emotive (affective) functions and signaling speech turns, e.g. turn keeping or ending, as well as adding, emphasizing, disambiguating or correcting information (see e.g. Ashby 1988; Averintseva-Klisch 2008b; Detges and Waltereit 2014; Erguvanli 1984; Herring 1994; Mayol 2007; Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin 2019; Pfeiffer 2015; Rodman 1997; Selting 1994). Hence, the types of rXPs might display variation in certain situational contexts due to their diverging central discourse functions. We thus analysed the types of rXPs for their functional characteristics in discourse in German and Persian (see Section 3.2) to determine whether functional associations may also motivate register distinctions between types of rXPs.

3.1 Corpus

The data of the Lang*Reg corpus was collected in Tehran, Iran (a total of 20 speakers) for Persian and Berlin, Germany (a total of 12 speakers) for German.[12] The participants were between 18 and 50 years old. The corpus makes it possible to directly observe how speakers adapt their language output in different situational-functional contexts and compare such behaviours across languages. Participants produced language in 6 situations comprised of two tasks: a) telling a story to a friend, b) talking freely with various kinds of interlocutors (friend, stranger, taxi driver or professor). The task of storytelling was conducted in two modes so that we are able to compare how the same language user behaves in written versus spoken contexts.

The differences between the situational contexts included in the Lang*Reg corpus can be described with the following main parameters (similar to features found in the “context of situation” framework used in Systemic-Functional Linguistics, see e.g. Halliday and Ruqalya 1989; Neumann 2014): (i) social hierarchy versus equality, (ii) social distance versus closeness (implemented as acquaintance vs. non-acquaintance), and also (iii) mode, i.e. spoken versus written, and (iv) interactivity realised as non-interactive monologue versus interactive dialogue. Each recording situation is a deliberate combination of these parameters. For an overview of the specific characteristics of the situations in the corpus, see Table 1. A detailed description of the corpus design, its parameters and the procedure is provided in Lehmann et al. (2025).

Characteristics of the Lang*Reg corpus design as presented in Lehmann et al. (2025), detailing the six recording situations with their varying communication events (different interlocutors and monologue or dialogue type of interaction) and situation features (mode, length and space). Two main social relation criteria are varied: social distance between interlocutors (related to level of acquaintance) and social hierarchy between interlocutors, i.e. whether the participant (P) or their interlocutor (I) exerts more power in the scope of the activity.

| No | Communication event | Situation features | Social relation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interlocutor | Interactivity | Mode | Length | Space | Distance | Hierarchy | |

| 1 | Friend | Monologue | Written | – | Private | Close | P = I |

| 2 | Friend | Monologue | Spoken | 2min | Private | Close | P = I |

| 3 | Friend | Dialogue | Spoken | 15min | Private | Close | P = I |

| 4 | Stranger | Dialogue | Spoken | 15min | Private | Distant | P = I |

| 5 | Taxi driver | Dialogue | Spoken | 15min | Non-private | Distant | P > I |

| 6 | Professor | Dialogue | Spoken | 15min | Non-private | Distant | P < I |

As the peripheries are often described as instruments particularly relevant for interactional discourse (see among others Aijmer 1989: 147; Auer 1991: 152; Duranti and Ochs 1979: 403; Geluykens 1992: Section 1.3; Imo 2015: Section 4.2; Selting 1994: 311; Tizón-Couto 2012: 279), the corpus is particularly suitable to examine how right-peripheral subjects are exploited for register purposes since it includes situational contexts that vary in the degree of interactivity, including the friend spoken monologue and the friend written monologue as non-interactional contexts and the spoken conversations between friends, strangers, with a taxi driver and with a professor as interactional contexts. This allows us to cluster the situations by their degree of interactivity in order to examine whether the right periphery is indeed used more for managing the interpersonal, dialogic space. Moreover, we can put the results of interactivity in context with the mode distinctions in the non-interactional situations. Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin (2019: 304) postulate that written texts use the right periphery for focused elements in the absence of explicit cues from prosody. The corpus design allows us to test whether mode has such a bearing on the exploitation of the right periphery.

3.2 Methods

Using the morphosyntactic annotations in Lang*Reg, we extracted all nominal subjects occurring in the right periphery of the German and Persian datasets, i.e. whenever an NP that can take on the function of the core syntactic subject follows the clause-final verbal complex indicated by finite or non-finite verbs, verb particles, and predicatives.[13] We also extracted all instances of finite verbs as well as subjects that do not occur in the right periphery in order to calculate the rate with which the right periphery is used to specify subjects.[14] The extracted instances contain morphosyntactic information such as phrase type as well as metadata about the situational context, including information about the speaker and the recording situation.

The extracted right-peripheral subjects were checked for their validity. Valid cases are identified by their coreference relation between a core-internal correlate or the possibility of an alternative core-internal placement of the peripheral phrase. While one might argue that in particular afterthoughts as clause-external independent phrases could also occur with non-coreferential relations, we restrict the analysis to coreferential phrases in order to guarantee comparability across peripheral elements. We thus excluded the following cases:

parts or coordinations of subjects that appear postverbally

(12)die Rucksäcke waren durchnässt, ebenso die Zelte und Schlafsäcke the backpacks were soaked also the tents and sleeping.bags und Klamotten . and clothes ‘The backpacks were soaked as well as the tents and sleeping bags and clothes’ [Lang*Reg-Ger] (13)jek koh æst væ jek kɒrvɒnsærɒ one mountain is and one caravanserai ‘There is a mountain and a caravanserai.’ [Lang*Reg-Per] negated alternatives to subjects that appear postverbally

(14)die arbeiten nämlich im Team mittlerweile also nicht nur eine they work namely in.the team by.now so not only one Möwenart seagull.kind ‘They actually work in a team by now, that is not only one kind of seagull.’ [Lang*Reg-Ger] inferentially linked alternative subjects (“bridging”) that occur postverbally[15]

(15)des würde wahrscheinlich da in so=n Rechner total reinhauen that would probably there in so=a calculator totally into.hit von den Werten zum Beispiel vegane Ernährung of the values to.the example vegan diet ‘that would probably have a big impact in such a calculator in terms of values for example vegan diets.’ [Lang*Reg-Ger] (16)dærjɒ ke hæmiʃe miɡujænd bɒese ɒrɒmeʃ æst væ moxsusæn sedɒʃ sea that always say.3pl cause peace is and specially sound ‘It is said that the sea always brings peace, especially its sound.’ [Lang*Reg-Per]

Each valid occurrence was then analysed for its formal characteristics as delineated in Section 2 and classified according to the formal type of rXP using the operationalization presented in Figure 1.[16] We then used the number of non-right-peripheral subjects to measure the proportion of rXP occurrences. As Persian is a pro-drop language, we used the number of finite verbs to estimate the potential non-peripheral subject slots. For German, the overt occurrences of subjects was used, which has the advantage that we can distinguish between nominal and pronominal non-peripheral subjects forms, thus providing more precise rates of occurrence as RD and AT.prn vary only with pronominal subjects while AT.NP varies only with nominal subjects.[17]

We further conducted a functional analysis of the four formal rXP types for subjects in German and Persian by looking at the following aspects: a) narrow focus of the rXP, including contrastive focus, i.e. whether the previous linguistic context opens up explicit alternatives, b) the relation of the rXP to what the previous and following discourse is about, c) the saliency of the rXP, i.e. whether it is situationally, textually, implicitly (inferred) or not evoked, d) the distance to the last mention of the referent, e) status of ambiguity, f) status of elaboration, i.e. whether the rXP adds more information than just the identity of the referent, and g) speaker turn, i.e. whether the producer of the rXP started, ended or continued their turn.

3.3 Results and discussion

3.3.1 Overview

Our findings with Lang*Reg confirm previous reports that the deployment of the right periphery is generally a low frequency phenomenon. For instance, Selting (1994: 313) found a total of 19 right-peripheral elements, including arguments as well as non-arguments, for German in four informal conversations between three participants, each of about 2 h in length. This pattern is also prevalent in other languages: in English, Aijmer (1989: 138–139) found 49 right-peripheral arguments[18] in a spoken corpus of about 170,000 tokens; in Tamil, Herring (1994: 122) found 285 right-peripheral elements, including arguments and non-arguments, in a corpus with oral narratives (8.1 % rXPs in a dataset of 1787 finite clauses) and written published short stories (7.1 % rXPs in a dataset of 1986 finite clauses); for Japanese, Nakagawa et al. (2008: 8) report 34 right dislocations and 13 afterthoughts in a spoken corpus of 12.2 h of recordings with task-based talks, interviews and free conversations between unacquainted speakers.

In our study, the rate of all subject rXPs is similarly low compared to the rate of all non-right-peripheral subjects, with numbers potentially being even lower than in earlier works due to the restriction on nominal subjects and the referential identity requirement, i.e. rXPs must specify the predicate’s subject argument and dislocated rXPs and ATs must be coreferential with the correlate. The German portion of the Lang*Reg corpus contains 84,346 tokens and subject rXP occurrences are under 1 % of all subjects. The Persian subcorpus has 152,102 tokens and subject rXP occurrences cluster around 1 % in different communicative contexts. As a result, the outcome of the study is not conclusive in all respects. Nevertheless, the results show striking similarities and differences between Persian and German. The rates of subject rXPs are given Table 2 for both languages, differentiated by the six recording situations using the following labels: professor oral conversation = Prf.Orl.Cnv, taxi driver oral conversation = Tx.Orl.Cnv, stranger oral conversation = Strngr.Orl.Cnv, friend oral conversation = Frnd.Orl.Cnv, friend oral storytelling = Frnd.Orl.Stry, friend written storytelling = Frnd.Wrttn.Stry. The situations are further grouped by the degree of interactivity, i.e. interactive versus non-interactive.

Rate of subject rXP in German (84,346 tokens) & Persian (152,102 tokens) across situations.

| Language | Interactivity | Situation | n subject | n rXP | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | Interactive | Prf.Orl.Cnv | 2,238 | 8 | 0.36 |

| Tx.Orl.Cnv | 1,895 | 12 | 0.63 | ||

| Strngr.Orl.Cnv | 1,847 | 14 | 0.76 | ||

| Frnd.Orl.Cnv | 1,757 | 11 | 0.63 | ||

| Total | 7,737 | 45 | 0.58 | ||

| Non-interactive | Frnd.Orl.Stry | 491 | 2 | 0.41 | |

| Frnd.Wrttn.Stry | 373 | 1 | 0.27 | ||

| Total | 864 | 3 | 0.35 | ||

| Total | – | 8,601 | 48 | 0.56 | |

|

|

|||||

| Persian | Interactive | Prf.Orl.Cnv | 4,917 | 52 | 1.06 |

| Tx.Orl.Cnv | 5,247 | 58 | 1.11 | ||

| Strngr.Orl.Cnv | 4,551 | 47 | 1.03 | ||

| Frnd.Orl.Cnv | 3,930 | 33 | 0.84 | ||

| Total | 18,645 | 190 | 1.02 | ||

| Non-interactive | Frnd.Orl.Stry | 1,124 | 5 | 0.44 | |

| Frnd.Wrttn.Stry | 923 | 4 | 0.43 | ||

| Total | 2,047 | 9 | 0.44 | ||

| Total | – | 20,692 | 199 | 0.96 | |

The right periphery is generally used more frequently in Persian as around 1 % of all subjects occur in the right periphery compared to German where the rate of subject rXPs ranges from 0.27 % to 0.76 % (on average 0.56 % across all contexts). Both languages use more right-peripheral subjects in interactive contexts than in non-interactive ones in line with the expectation that the use of the right periphery in general is a strategy for interactional discourse (see Section 3.1). The two non-interactive contexts here display a lower rate of subject rXPs irrespective of mode in both languages. Notably, among the interactive situations, the professor oral conversations pattern differently in both languages compared to the other conversations: in Persian, the professor conversations have a higher rXP frequency than the friend conversations whereas this is reversed in German.

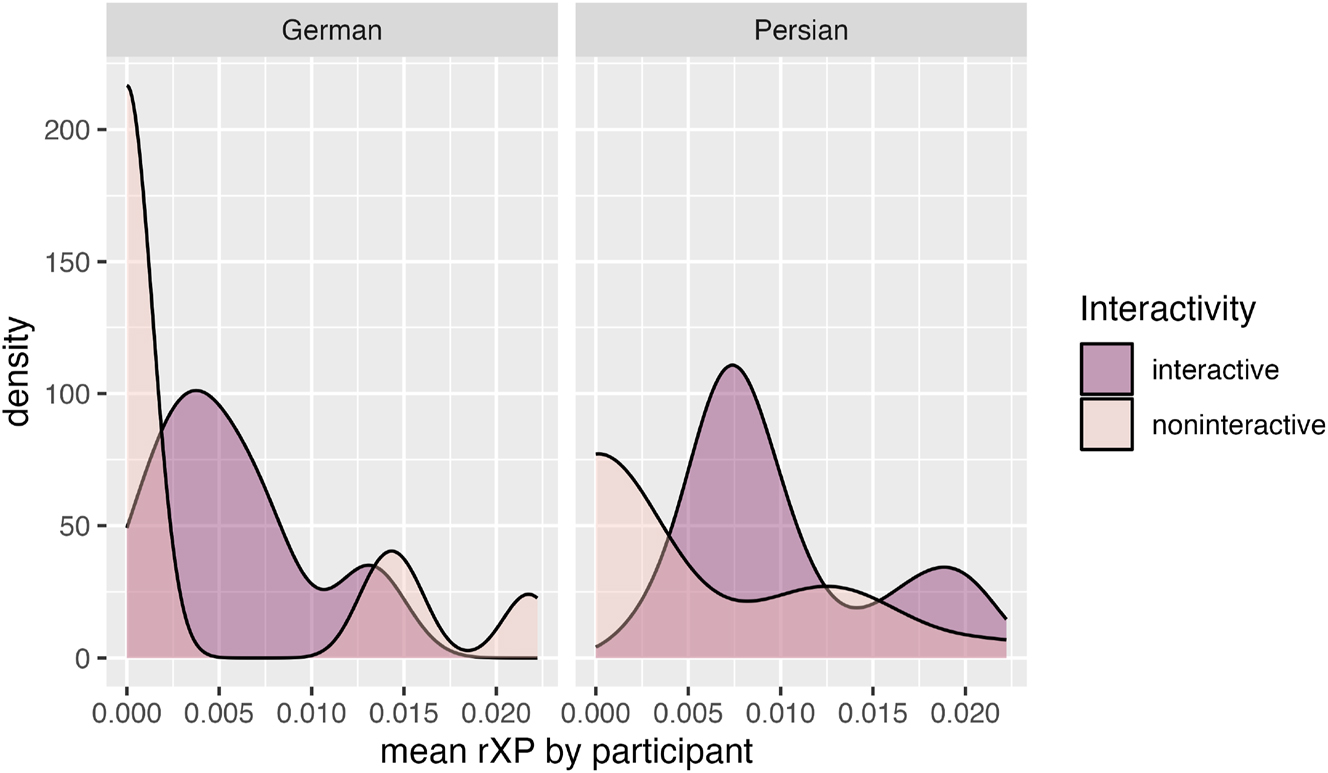

Figure 2 displays the density of the mean employment of subject rXPs by participant. The Persian interactive contexts have a higher density of participants with a higher subject rXP mean than the non-interactive contexts: the interactive contexts have the highest density at a mean of around 0.075 whereas the non-interactive contexts have the highest density of participants with a mean of 0. This is similar in German, where the non-interactive contexts also have the highest density around the mean of 0. Note, however, that the number of instances of subject rXP per participant is very low in German so that the density plot line drops to zero before increasing again with means of subject rXP higher than zero for isolated participants. In contrast to the non-interactive contexts, the German interactive contexts have the highest density around the mean 0.004. In both languages, the interactive contexts show a second, slightly less pronounced peak in density with a higher mean (at 0.013 in German and 0.019 in Persian), which shows that a select group of participants has a higher mean use of subject rXP than the majority.

Density of mean rXP per participant by interactivity in German and Persian.

Fitting the results with a generalized linear mixed-effects model using Interactivity as the independent variable and rXP occurrence (right-peripheral subjects vs. non-right-peripheral subject) as the dependent variable with the random intercepts Participant shows a significant impact of interactivity for Persian (p < 0.05) but not for German (p > 0.05). The model estimates for both languages are provided in Table 3.

Model estimates for rXP rate by interactivity.

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr (> z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | (Intercept) | −5.74612 | 0.59038 | −9.73293 | 0.00000 |

| Interactivity: interactive | 0.47857 | 0.58902 | 0.81249 | 0.41651 | |

| Persian | (Intercept) | −5.52656 | 0.34738 | −15.90913 | 0.00000 |

| Interactivity: interactive | 0.86779 | 0.34185 | 2.53850 | 0.01113 |

3.3.2 Type of rXP

The distribution of all subjects in form of the four formal rXP types mapped out in Section 2 are presented in Table 4 for German and Persian. Subject extraposition is very rare in German (<0.01 % out of all subject occurrences). In contrast, extraposition is the most frequent type of subject rXP in Persian (0.3–0.8 %). Subject right dislocation does not occur in Persian whereas German participants did use right dislocation, though not very frequently (0.2–0.3 %).[19] Afterthoughts with a pronoun correlate (AT.prn) are the most frequent subject rXP in the German data (0.2–0.4 %) and second most frequent in the Persian data (0.2–0.4 %). Afterthoughts with a nominal correlate (AT.NP) are rare among all subject rXP in both languages (0–0.2 %). Both types of afterthoughts therefore seem to pattern similarly in both languages. The main difference between languages lies in the use of extraposition and right dislocation.

Rate of types of subject rXP in German and Persian across situations.

| Language | Interactivity | Context | AT.NP | AT.prn | ExtrP | RD | All subjects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| German | Interactive | Prf.Orl.Cnv | – | – | 7 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.04 | – | – | 2,238 | 100 |

| Tx.Orl. Cnv | 2 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.26 | 1,895 | 100 | ||

| Strngr.Orl.Cnv | 3 | 0.16 | 7 | 0.38 | 1 | 0.05 | 3 | 0.16 | 1,847 | 100 | ||

| Frnd.Orl.Cnv | 2 | 0.11 | 6 | 0.34 | – | – | 3 | 0.17 | 1,757 | 100 | ||

| Non-interactive | Frnd.Orl.Stry | 1 | 0.2 | – | – | 1 | 0.2 | – | – | 491 | 100 | |

| Frnd.Wrttn.Stry | – | – | 1 | 0.27 | – | – | – | – | 373 | 100 | ||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Persian | Interactive | Prf.Orl.Cnv | 6 | 0.12 | 20 | 0.41 | 26 | 0.53 | – | – | 4,917 | 100 |

| Tx.Orl.Cnv | 4 | 0.08 | 13 | 0.25 | 41 | 0.78 | – | – | 5,247 | 100 | ||

| Strngr.Orl.Cnv | 1 | 0.02 | 14 | 0.31 | 32 | 0.7 | – | – | 4,551 | 100 | ||

| Frnd.Orl.Cnv | – | – | 8 | 0.2 | 25 | 0.64 | – | – | 3,930 | 100 | ||

| Non-interactive | Frnd.Orl.Stry | – | – | 2 | 0.18 | 3 | 0.27 | – | – | 1,124 | 100 | |

| Frnd.Wrttn.Stry | – | – | – | – | 4 | 0.43 | – | – | 923 | 100 | ||

The functional analysis[20] of rXP types revealed that each type is associated with a dominant function, even though right-peripheral elements are a multi-functional phenomenon (see in particular Geluykens 1992: 95; Tizón-Couto 2012: Part III). Via the functional annotations as described in Section 3.2 we assigned the following functions to each rXP: i) clarification when the rXP is ambiguous or not very salient, e.g. distant last mention or implicitly/not evoked, ii) elaboration when the rXP adds information to the referent, iii) topic management when the rXP referent is salient, i.e. situationally, textually or implicitly evoked, and continues as the discourse topic or becomes the discourse topic, iv) emphasis when the rXP receives narrow focus. The annotation values of speaker turn showed only a minor function of directing the discourse, which might rather be a consequence of topic management.

The main function of AT.NP is to add further qualities for the referent in both languages, seeing as they are typically marked as elaborative, irrespective of other characteristics. Apart from identifying the referent, subject rXPs with an elaborative function provide additional information about the referent, for instance to “activate a particular attribute” of the referent (Westbury 2016: 37), as for instance in (17a) where the nominal correlate is not ambiguous but the subject rXP adds attributes via the compound component Liefer- ‘delivery’ or for Persian in (17b) where the exact nominal is repeated with the added adjective dæruni ‘inner’. AT.NP therefore associate more information with the referent that has not been mentioned in the previous discourse, information that will then be added to the common ground (Truckenbrodt 2015: 332).

| weil | auf | dem | Fahrradweg | ein | Auto | stand | ein | Lieferauto |

| because | on | the | bicycle.lane | a | car | stand | a | delivery.car |

| ‘because there was a car on the bicycle lane, a delivery car’ | ||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | ||||||||

| vɒɣeæn | ɒrɒmeʃ | bud | ɒrɒmeʃ=e | dæruni |

| really | calmness | be.pst[3sg] | calmness=DEF | inner |

| ‘it was really a calmness inner calmness’ | ||||

| [Lang*Reg-Per] | ||||

Cases of AT.prn tend to fulfil the purpose across languages to clarify the referent due to some ambiguity or (perceived) lack of saliency (see also Coniglio and Schlachter 2015: 145), though they may occasionally also have elaborative qualities.[21] The referent is usually a) new and underspecified as in (18a), where the pronoun es ‘it’ is not sufficiently clear about what is the cause for the discomfort when wearing a mask, leaving open various potential inconveniences until the AT.prn clarifies that it is the heat which annoys the speaker the most, or b) ambiguous as in (18b) in which two city names were mentioned before, i.e. Bastam and Shahroud, and even though bæstɒm is the topic, speaker A deems it necessary to clarify that the characterization of the city is meant for Bastam and not Shahroud, which is apparent from the two separate intonation contours.

| und | dann | dass | es | ebend | unangenehm | ist | wie | mit | der | Maske | also | die |

| and | then | that | it | just | uncomfortable | is | like | with | the | mask | so | the |

| Wärme | ||||||||||||

| warmth | ||||||||||||

| ‘and then that it’s just uncomfortable, like with the mask, I mean the heat’ | ||||||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | ||||||||||||

| A: | Bastam I may be able to say that it is five kilometres from Shahroud. | |||||||||

| B: | Shahroud | |||||||||

| A: | jek | ʃæhr=e | xejli | kut͡ʃæk | væ | d͡Ʒæmvæ | d͡Ʒur=i | æst | bæstɒm | |

| one | city | very | small | and | well.set | kind=def | be[3sg] | Bastam | ||

| ‘It is a small and well set city, Bastam.’ | ||||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Per] | ||||||||||

In most cases of right dislocation, which only occur in German, the following discourse broadly revolves around the rXP, which means they tend to occur when the floor will be kept.[22] This indicates that floor keeping has some relevance for right dislocation. The referent specified by the right-dislocated phrase is generally salient in the discourse, often evoked situationally or textually, but also via inference. The previous discourse topic can either be the same or different, which highlights that right dislocation is mainly a forward facing construction (see similarly e.g. for German: Averintseva-Klisch 2008a: 242; Selting 1994: 312; for Catalan: Mayol 2007: 210; for Japanese: Nakagawa et al. 2008: 2). The example in (19) shows that the dislocated subject die Arten ‘the kinds’ is not truly believed to be ambiguous by the speaker as it directly refers to the seagulls the speaker was talking about; instead, the right-dislocated phrase introduces the theme for the following discourse, where the speaker dives deeper into the area of “kinds of seagulls” and explains the type of sea gulls and their characteristics.

| ich | glaube | es | war | eine | große | und | eine | kleinere | zusammen. | ich | habe |

| I | believe | it | was | one | big | and | one | small | together | I | have |

| letztens | als | wir | da | waren | habe | ich | nochmal | nachgeguckt | wie | die | |

| recently | when | we | there | were | have | I | again | looked | how | they |

| heißen | die | Arten . | und | die | größten | die | heißen | Mantelmöwen. | und | ||

| named | the | kinds | and | the | biggest | they | named | great.black.backed.gull | and |

| die | sind | ja | echt | Klopper | |||||||

| they | are | indeed | real | big.lumps | |||||||

| ‘I think it was a big and a small one together. Last time, when we were there, I looked again what they are called, these kinds (of seagulls). And the biggest ones, they are called great black-backed gull. And they are real hunks.’ | |||||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | |||||||||||

In Persian, extraposed subjects are usually concerned with what the following discourse is about (see similarly e.g. Erguvanli 1984: 57 on Turkish; Herring 1994: 127 on Tamil). In (20), the extraposition rustɒ ‘village’ marks the continuation of the general theme from the previous discourse, i.e. talking about the place visited on a trip to a particular region. Importantly, the following discourse expands on the properties of the village, e.g. its wide streets, which indicate the lower population compared to other regions for the speaker.

| væ | d͡Ʒæmijjæt=i | hæm | næ-dɒr-æd | rustɒ |

| and | population=indf | also | neg-have-sbj.3sg | village |

| ‘and the village is not populated either’ | ||||

| [Lang*Reg-Per] | ||||

German extraposed subjects tend to be focused, thus performing an emphasis function,[23] as in (21), but they do not stand in a specific relation to the previous or following discourse topic, usually also not being the sentence topic and not patterning with any discourse topic. In German, extraposed subjects also do not have to be salient.

| und | in | diesem | Wasser | sind | teilweise | überflutet | auch | Monumente |

| and | in | this | water | are | partly | submerged | also | monuments |

| ‘and monuments are also partly submerged in that water’ | ||||||||

| [Lang*Reg-Ger] | ||||||||

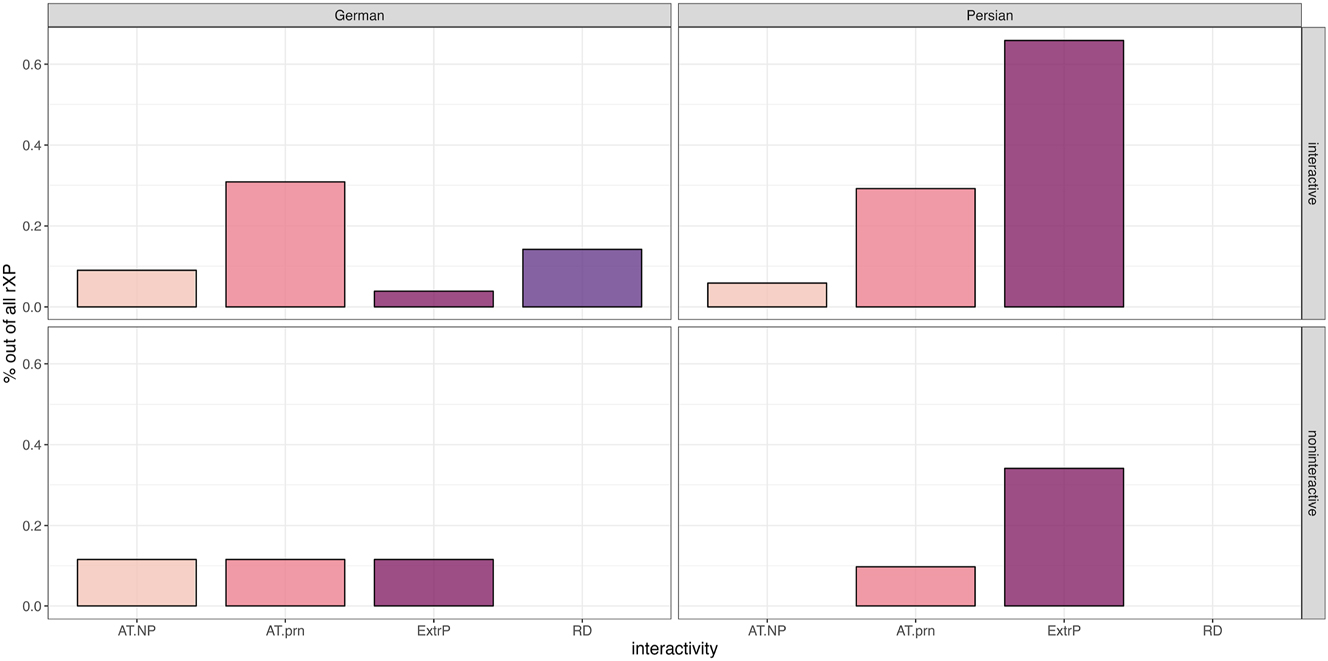

The function of a linguistic phenomenon motivates its occurrence in certain situational contexts and the similarity in function for RD in German and extraposition in Persian warrants the comparison of these two rXP types across the two languages for register variation. Due to the very low number of instances for each type of rXP, however, we can only tentatively interpret the data qualitatively. As illustrated in Figure 3, German participants used RD more frequently in interactive contexts the same way that Persian participants used extraposition more often in interactive contexts. We further observe that extraposition is used more often in Persian than RD in German despite their similarity in function.

Proportion of types of rXP by interactivity in German and Persian.

AT has a different function from RD and extraposition, namely that of clarification (AT.prn) and elaboration (AT.NP), which appears to be a language-independent functional attribute of AT. We therefore compare AT.prn and AT.NP across languages and their relation to the situational contexts. AT.prn occur more often in interactive context in both languages in the Lang*Reg corpus. For AT.NP, no difference between interactivity can be reliably discerned in either language due to the low frequency.

4 Conclusions

Our explorative analysis of subjects in the right periphery in Persian and German as presented in Section 3.3 indicates that structural differences between the two languages lead to distinctive uses of the right periphery. Persian, which readily accepts movement of nominal arguments into the right periphery, i.e. extraposition, makes use of this strategy for interactive signalling, e.g. indicating what the following discourse is about. In German, extraposition is highly restricted to specially focused nominal arguments; instead, German language users employ right dislocation for signals about the proceeding discourse, though right dislocation is used much more sparingly in German than extraposition in Persian. The fact that Persian has the core-internal strategy available for topic and interaction management could explain why it is used generally more frequently than its functional equivalent right dislocation in German, as right dislocation with its biclausal structure appears to be a more marked construction.

It was shown that interactivity affects the employment of the right periphery in Persian, but this effect could not be shown for German, possibly due to the very low frequency of rXP overall. Looking at different types of rXP, it appears that extraposed rXP in Persian and dislocated rXP in German also pattern similarly across interactive and non-interactive situations, yet it will require a much larger corpus to verify such observations. Lastly, the analysis of the right periphery revealed that afterthoughts behave very similarly across the two languages.

Further observations point towards a lack of mode as an influencing factor for the use of the right periphery. If this turns out to be borne out, then the observations by Molnár and Vinckel-Roisin (2019) about the use of focused rXPs in written texts may be specific to the particular communicative purpose of newspaper texts used in the study. Social hierarchy seems to pattern in opposite directions in both languages; hence, it is a promising avenue of research to examine languages that allow dislocation to the right and extraposition in languages that behave like Persian using much larger data sets in order to compare the behaviour between different situational contexts, including distinctions in mode as well as between situations affected by varying social role relations.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)

Award Identifier / Grant number: 416591334

-

Author contributions: Concepts and phenomenon selection: N. L., M. S., E. V., A. A.; Data analysis – German: N. L. & Persian: V. M., M. S., N. L.; Writing: N. L.; Editing: N. L., E. V.; Statistics: N. L.; Supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: A. A., E. V.

-

Research funding: The research was undertaken within the CRC 1412 “Register: Language Users’ Knowledge of Situational-Functional Variation” at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and the Universität zu Köln. The research is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – CRC 1412, 416591334.

References

Adli, Aria (ed.). 2016. Sgs corpus. Köln: Sociolinguistic Lab at the University of Cologne. Available at: http://sgscorpus.com.Suche in Google Scholar

Adli, Aria, Elisabeth Verhoeven, Nico Lehmann, Vahid Mortezapour & Jozina Vander Klok. 2023. Lang*Reg: A multi-lingual corpus of intra-speaker variation across situations. Version 0.1.0. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7646320.Suche in Google Scholar

Aijmer, Karin. 1989. Themes and tails: The discourse functions of dislocated elements. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 12(2). 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1017/s033258650000202x.Suche in Google Scholar

Altmann, Hans. 1981. Formen der “Herausstellung” im Deutschen: Rechtsversetzung, Linksversetzung, Freies Thema und verwandte Konstruktionen, vol. 106 (Linguistische Arbeiten). Tübingen: Niemeyer Verlag.10.1515/9783111635286Suche in Google Scholar

Ashby, William J. 1988. The syntax, pragmatics, and sociolinguistics of left- and right-dislocations in French. Lingua 75(2–3). 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(88)90032-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter. 1991. Vom Ende deutscher Sätze. Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 19(2). 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfgl.1991.19.2.141.Suche in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter. 2006. Increments and more. Anmerkungen zur augenblicklichen Diskussion über die Erweiterbarkeit von Turnkonstruktionseinheiten. In Arnulf Deppermann, Reinhard Fiehler & Thomas Spranz-Fogasy (eds.), Grammatik und Interaktion, 279–294. Radolfzell: Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.Suche in Google Scholar

Averintseva-Klisch, Maria. 2008a. German right dislocation and afterthought in discourse. In Anton Benz & Peter Kühnlein (eds.), Constraints in discourse (Pragmatics and Beyond New Series 172), 213–235. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.172.11aveSuche in Google Scholar

Averintseva-Klisch, Maria. 2008b. Reparatur oder Hervorhebung? Semantik und Pragmatik der Rechtsversetzung im Deutschen. In Inge Pohl (ed.), Semantik und Pragmatik – Schnittstellen, 399–416. Frankfurt/M.: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Averintseva-Klisch, Maria. 2009. Rechte Satzperipherie im Diskurs: Die NP-Rechtsversetzung im Deutschen. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.Suche in Google Scholar

Averintseva-Klisch, Maria. 2019. The ‘Separate Performative’ account of the German right dislocation. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 10(1). 15–28. https://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2006.v10i1.671.Suche in Google Scholar

Averintseva-Klisch, Maria & Buecking Sebastian. 2019. Dislocating NPs to the right: Anything goes? Semantic and pragmatic constraints. In Proceedings of SuB12, 32–46. Oslo: ILOS 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Becker, Thomas. 2016. Gibt es im Deutschen eine ‘Satzklammer. In Andreas Bittner & Constanze Spieß (eds.), Formen und Funktionen: Morphosemantik und grammatische Konstruktion, 233–250. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110478976-014Suche in Google Scholar

Beeching, Kate & Ulrich Detges. 2014. Introduction. In Kate Beeching & Ulrich Detges (eds.), Discourse functions at the left and right periphery, 1–23. Leiden, Boston: Brill.10.1163/9789004274822_002Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 1995. Dimensions of register variation: A cross-linguistic study. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511519871Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 2012. Register as a predictor of linguistic variation. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 8(1). 9–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt-2012-0002.Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Susan Conrad. 2019. Register, genre, and style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108686136Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Jesse Egbert, Daniel Keller & Stacey Wizner. 2021. Towards a taxonomy of conversational discourse types: An empirical corpus-based analysis. Journal of Pragmatics 171. 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.018.Suche in Google Scholar

Clark, Herbert H. 1975. Bridging. In Bonnie L. Nash-WebberRoger Schank (eds.), Theoretical issues in natural language processing (ACL Anthology), 169–174. https://aclanthology.org/T75-2/.10.3115/980190.980237Suche in Google Scholar

Coniglio, Marco & Eva Schlachter. 2015. Das Nachfeld im Deutschen zwischen Syntax, Informations- und Diskursstruktur. In Hélène Vinckel-Roisin (ed.), Das Nachfeld im Deutschen, 141–164. Berlin, München, Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110419948-008Suche in Google Scholar

Degand, Liesbeth & Ludivine Crible. 2021. Chapter 1. Discourse markers at the peripheries of syntax, intonation and turns: Towards a cognitive-functional unit of segmentation. In Daniël Van Olmen & Jolanta Šinkūnienė (eds.), Pragmatic Markers and peripheries, 19–48. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Available at: https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027259080-pbns.325.01deg.10.1075/pbns.325.01degSuche in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf, Martin Hartung, Thomas Schmidt & Silke Reineke. 2020. Forschungs- und Lehrkorpus Gesprochenes Deutsch. Mannheim: IDS Mannheim. Available at: https://dgd.ids-mannheim.de/.Suche in Google Scholar

Detges, Ulrich & Richard Waltereit. 2014. Moi je ne sais pas vs. Je ne sais pas moi: French disjoint pronouns in the left vs. right periphery. In Kate Beeching & Ulrich Detges (eds.), Discourse functions at the left and right periphery, 24–46. Leiden, Boston: Brill.10.1163/9789004274822_003Suche in Google Scholar

Drummond, Alex. 2009. The unity of extraposition and the A/A’ distinction. In The proceedings of the forty-fifth annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society: Locality in language, 43–56. Chicago, IL: Chicago Linguistic Society.Suche in Google Scholar

Duranti, Alessandro & Elinor Ochs. 1979. Left-dislocation in Italian conversation. In Talmy Givon (ed.), Discourse and syntax, vol.12 (Syntax and semantics), 377–416. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004368897_017Suche in Google Scholar

Erguvanli, Eser Emine. 1984. The function of word order in Turkish grammar. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ferguson, Charles A. 1959. Diglossia. Word 15. 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1959.11659702.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández-Sánchez, Javier & Dennis Ott. 2020. Dislocations. Language and Linguistics Compass 14(9). https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12391.Suche in Google Scholar

Féry, Caroline. 2015. Extraposition and prosodic monsters in German. In Lyn Frazier & Edward Gibson (eds.), Explicit and implicit prosody in sentence processing, vol. 46 (Studies in theoretical psycholinguistics), 11–37. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-12961-7_2Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2005. Pragmatic properties of certain German and English left peripheral constructions. Linguistics 43(1). 89–129. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2005.43.1.89.Suche in Google Scholar

Frommer, Paul Robert. 1981. Post-verbal phenomena in colloquial Persian syntax. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California.Suche in Google Scholar

Geluykens, Ronald. 1992. From discourse process to grammatical construction: On left-dislocation in English (Studies in Discourse and Grammar). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/sidag.1Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1978. Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Hasan Ruqaiya. 1989. Language, context, and text: Aspects of Language in a social-semiotic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hartmann, Katharina. 2017. PP-extraposition and nominal pitch in German. In Clemens Mayr & Edwin Williams (eds.), Festschrift für Martin Prinzhorn, vol. 82, 99–107. Universität Wien: Wiener Linguistische Gazette (WLG).Suche in Google Scholar

Hawkins, John A. 2008. An asymmetry between VO and OV languages: The ordering of obliques. In Greville G. Corbett & Michael Noonan (eds.), Case and grammatical relations: Studies in honor of Bernard Comrie (Typological Studies in Language), 167–190. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.81.08anaSuche in Google Scholar

Herring, Susan C. 1994. Afterthoughts, antitopics, and emphasis: The syntacticization of post-verbal position in Tamil. In Miriam Butt, Tracy Holloway King & Gillian Ramchand (eds.), Theoretical perspectives on word order in Asian languages, 119–152. Stanford: CSLI.Suche in Google Scholar

Imo, Wolfgang. 2014. Appositions in monologue, increments in dialogue? On appositions and apposition-like patterns in spoken German and their status as constructions. In Ronny Boogaart, Timothy Colleman & Gijsbert Rutten (eds.), Extending the scope of construction grammar, 321–352. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110366273.321Suche in Google Scholar

Imo, Wolfgang. 2015. Zwischen Construction Grammar und Interaktionaler Linguistik: Appositionen und appositionsähnliche Konstruktionen in der gesprochenen Sprache. In Alexander Lasch & Alexander Ziem (eds.), Konstruktionsgrammatik IV, 91–114. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.Suche in Google Scholar

Koch, Peter & Oesterreicher Wulf. 1985. Sprache der Nähe – Sprache der Distanz. Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte. Romanistisches Jahrbuch 36. 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110244922.15.Suche in Google Scholar

Lambrecht, Knud. 2001. Dislocation. In Martin Haspelmath, Ekkehard Konig, Wulf Oesterreicher & Wolfgang Raible (eds.), Language typology and language universals, vol. 20, 1050–1078. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.2Suche in Google Scholar

Lehmann, Nico, Vahid Mortezapour, Jozina Vander Klok, Zahra Farokhnejad, David Müller, Elisabeth Verhoeven & Aria Adli. 2025. Lang*Reg corpus: Documenting multi-modal intra-speaker variation across languages. Language Documentation & Conservation 19. 40–66.Suche in Google Scholar

Levin, Magnus & Callies Marcus. 2019. A comparative multimodal corpus study of dislocation structures in live football commentary. In Magnus Levin (ed.), Corpus approaches to the language of sports: Texts, media, modalities, 267–283. London: Bloomsbury Academic.10.5040/9781350088238.ch-011Suche in Google Scholar

Lüdeling, Anke, Artemis Alexiadou, Aria Adli, Karin Donhauser, Malte Dreyer, Markus Egg, Anna Helene Feulner, Natalia Gagarina, Wolfgang Hock, Stefanie Jannedy, Frank Kammerzell, Pia Knoeferle, Thomas Krause, Manfred Krifka, Silvia Kutscher, Beate Lütke, Thomas McFadden, Roland Meyer, Christine Mooshammer, Stefan Müller, Katja Maquate, Muriel Norde, Uli Sauerland, Stephanie Solt, Luka Szucsich, Elisabeth Verhoeven, Richard Waltereit, Anne Wolfsgruber & Lars Erik Zeige. 2022. Register: Language users’ knowledge of situational-functional variation: Frame text of the first phase proposal for the CRC 1412. Register Aspects of Language in Situation 1(1). 1–59. https://doi.org/10.18452/24901.Suche in Google Scholar

Maas, Utz. 2006. Der Übergang von Oralität zu Skribalität in soziolinguistischer Perspektive. In Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus, J. & Peter Trudgill (eds.), Soziolinguistik: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Wissenschaft von Sprache und Gesellschaft, vol. 2 (Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft), 2147–2170. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Mayol, Laia. 2007. Right-dislocation in Catalan: Its discourse function and counterparts in English. Languages in Contrast 7(2). 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1075/lic.7.2.07may.Suche in Google Scholar

Mittendorfer, Matthias. 2025. Discourse functions, placement and prosody: An FDG analysis of left and right dislocation in British English. In Elnora ten Wolde, Riccardo Giomi & Kees Hengeveld (eds.), Linearization in functional discourse grammar. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783111517629-006Suche in Google Scholar

Modaressi-Tehrani, Yahya. 1978. A sociolinguistic analysis of modern Persian. University of Kansas dissertation. Available at: https://books.google.de/books?id=JWqtnQEACAAJ.Suche in Google Scholar

Molnár, Valéria & Hélène Vinckel-Roisin. 2019. Discourse topic vs. sentence topic. Exploiting the peripheries of German verb-second sentences. In Valéria Molnár, Verner Egerland & Susanne Winkler (eds.), Architecture of topic, 293–333. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501504488-011Suche in Google Scholar

Nakagawa, Natsuko, Yoshihiko Asao & Naonori Nagaya. 2008. Information structure and intonation of right-dislocation sentences in Japanese. Kyoto University Linguistic Research 27. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.14989/73228.Suche in Google Scholar

Neumann, Stella. 2014. Contrastive register variation: A quantitative Approach to the comparison of English and German. Berlin: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110238594Suche in Google Scholar

Ott, Dennis & Mark de Vries. 2012. Thinking in the right direction: An ellipsis analysis of right-dislocation. Linguistics in the Netherlands 29. 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1075/avt.29.10ott.Suche in Google Scholar

Ott, Dennis & Mark de Vries. 2016. Right-dislocation as deletion. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 34(2). 641–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9307-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Pfeiffer, Martin. 2015. Selbstreparaturen im Deutschen. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110445961Suche in Google Scholar

Pregla, Andreas. 2023. Word order variability in OV languages: A study on scrambling, verb movement, and postverbal elements with a focus on Uralic languages. Universität Potsdam dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Rasekh-Mahand, Mohammad & Mehdi Ghiyasvand. 2014. A corpus-based analysis of the factors affecting short scrambling in Persian [Barresiye peikare bonyAde tasire avAmele naqSi dar galbe nahvi kutAh dar zabAne FArsi]. Syntax: Special Issue of Farhangestan Letter. 163–196.Suche in Google Scholar

Rasekh-Mahand, Mohammad & N. Mousavi. 2007. Postposing in Persian [pasAyandsAzi dar zabAne fArsi]. In Proceeding of Allame Tabatabaei University [majmue maqAlate dAneSgAhe Allame Tabatabaei], vol. 219, 49–66.Suche in Google Scholar

Rezaei, Vali & Seyyed Mohammad Taghi Tayeb. 2005. Information structure and word order (sAxt-e etelA’ va tartib-e sAze-hAye jomle). Dastur Special Issue of Farhangestan 2. 3–19.Suche in Google Scholar

Rodman, Robert. 1997. On left dislocation. In Elena Anagnostopoulou, Henk van Riemsdijk & Frans Zwarts (eds.), Materials on left dislocation (Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today), 31–54. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.14.05rodSuche in Google Scholar

Selting, Margret. 1994. Konstruktionen am Satzrand als interaktive Ressource in natürlichen Gesprächen. In Brigitta Haftka (ed.), Was determiniert Wortstellungsvariation? Studien zu einem Interaktionsfeld von Grammatik, Pragmatik und Sprachtypologie, 299–318. Springer.10.1007/978-3-322-90875-9_18Suche in Google Scholar

Shaer, Benjamin & Werner Frey. 2004. ‘Integrated’ and ‘non-integrated’ left-peripheral elements in German and English. In Proceedings of the dislocated elements workshop, 465–502. Berlin: ZAS Berlin.10.21248/zaspil.35.2004.238Suche in Google Scholar

Tizón-Couto, David. 2012. Left dislocation in English (Linguistic Insights 143). Lausanne, Schweiz: Peter Lang Verlag. Available at: https://www.peterlang.com/document/1109234.Suche in Google Scholar

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2015. Intonation phrases and speech acts. In Marlies Kluck, Dennis Ott & Mark de Vries (eds.), Parenthesis and ellipsis: Cross-linguistic and theoretical perspectives, 301–350. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614514831.301Suche in Google Scholar

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2016. Some distinctions in the German Nachfeld. In Werner Frey, André Meinunger & Kerstin Schwabe (eds.), Inner-sentential propositional pro-forms: Syntactic properties and interpretative effects, 105–146. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.232.05truSuche in Google Scholar

Vinckel, Hélène. 2006. Die diskursstrategische Bedeutung des Nachfelds im Deutschen, Eine Untersuchung anhand politischer Reden der Gegenwartssprache. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitätsverlag Wiesbaden.Suche in Google Scholar

Westbury, Josh. 2016. Left dislocation: A typological overview. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 50. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5842/50-0-715.Suche in Google Scholar

Ziv, Yael. 1994. Left and right dislocations: Discourse functions and anaphora. Journal of Pragmatics 22(6). 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)90033-7.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Left and right peripheries in discourse: an introduction

- Articles

- Between core and periphery: the development in English of a modal adverb, an evaluative adverb and a discourse connector

- The emergence of last I checked fragments: a story of shifting allegiance

- Left-peripheral bottom line sequences

- Peripheral versus non-peripheral optative particles

- Adverbials in Extra-left position in spoken Danish

- Right-peripheral subjects in German and Persian across registers

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Left and right peripheries in discourse: an introduction

- Articles

- Between core and periphery: the development in English of a modal adverb, an evaluative adverb and a discourse connector

- The emergence of last I checked fragments: a story of shifting allegiance

- Left-peripheral bottom line sequences

- Peripheral versus non-peripheral optative particles

- Adverbials in Extra-left position in spoken Danish

- Right-peripheral subjects in German and Persian across registers