Abstract

This paper traces the formal and functional development of evidential extra-clausal fragments of the form (the) last I/we + VERB in American English. Using data from the Corpus of Historical American English and the Corpus of Contemporary American English, the study shows that these fragments are first attested in the late 19th century as a truncation of specificational structures (e.g. The last thing I remember is…). In the course of the 20th century, however, they exhibit a shift in allegiance by becoming increasingly associated with a temporal adjuncts template (e.g. The last time I checked…). Functionally, these evidential fragments are used as downtoners with additional functions being added in the course of the 20th century, viz. booster function and ironic use. The processes identified for their development are cooptation and subsequent grammaticalization, together with semantic specialization and constructional contamination. More generally, the fragmentary form (the) last I/we + VERB is shown to specialize in evidential use, with non-evidential verbs becoming increasingly rare in this string, while the full form remains firmly non-evidential. Fragmentary form thus has become an important marker for evidential (and, by extension, epistemic) function.

1 Introduction

The last decades have seen the rise of evidential fragments of the type last I checked, which are illustrated in (1) to (3).

| She is, last I heard , a fugitive from justice. |

| (COHA:2010:FIC:Bk:OneMind) |

| The last I knew , he was working for Channel 7 in Albuquerque. |

| (COCA:2008:FIC:TheProdigalNun) |

| And freedom does not preclude economic hardship, last I checked . |

| (COCA:2012:BLOG:reason.com) |

The use of these fragments in Present-day American English has been described in some detail in Mustafa and Kaltenböck (2024). The focus of the present paper is on the origin and development of these evidential last I fragments (or ELI fragments for short), drawing on data from the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). The study traces the development of ELI fragments in American English, from their first attestation in the 1860s, in terms of both form and function, and highlights the mechanism of change involved.[1] As recently emerging disjuncts with pragmatic function, their development is interesting also from the perspective of pragmatic markers more generally (e.g. Boye and Harder 2021; Brinton 2008, 2017; Heine et al. 2021; López-Couso and Méndez-Naya 2014, 2021; Traugott 2022).

It is shown that, originally a truncation of specificational structures (e.g. The last thing I remember is…), ELI fragments exhibit a shift in allegiance by becoming increasingly associated with temporal adjuncts (e.g. The last time I checked…) in the course of the 20th century. The processes identified as being involved in the rise of ELI fragments are those of cooptation (e.g. Heine et al. 2021) and subsequent grammaticalization, together with semantic specialization (Hopper 1991) and constructional contamination (Pijpops and Van de Velde 2016).

The chapter is structured as follows. Section 2 defines the fragment in question and Section 3 presents the database and overall frequencies. Section 4 is dedicated to the investigation of formal changes, focusing on the fragment itself (4.1), comparing evidential and non-evidential fragments (4.2), comparing evidential fragments and full forms (4.3), and providing an interim conclusion (4.4). Section 5 homes in on functional changes, both interpersonal (5.1) and textual (5.2). Section 6, finally, discusses the different mechanisms of change that can account for the emergence of ELI fragments. Section 7 offers a brief conclusion.

2 Defining evidential last I fragments

As illustrated by the examples above, ELI fragments are characterized by a specific form. It involves a sequence of elements outlined in (4): An optional definite article (the), followed by last, a first-person pronoun (typically singular I), and a verb, which is usually in past tense but may also be in present tense (e.g. remember, recall). There may also be a final optional adjunct (e.g. the last I saw from the satellite forecast).

| (the) last I/we VERB (Adjunct) |

Semantically, the verb expresses either (i) sensory perception (e.g. see, hear), as in example (1), (ii) cognition (e.g. remember, know), as in (2), or (iii) activities of information gathering (e.g. check, count), as in (3).[2] What all three have in common is that they convey a form of knowledge update and indicate the speaker’s source of information for the proposition of the host clause, thus giving the fragment its evidential function (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004: 3).

Syntactically, ELI fragments are best analysed as disjuncts (or extra-clausal constituents). As such, they are syntactically independent from their host clause, with which they are only pragmatically linked (e.g. Dik 1997: 379–409; Kaltenböck et al. 2016: 1–26; Peterson 1999). Consequently, they are invisible to a number of syntactic operations: They cannot be the focus of a corresponding it-cleft and are outside the scope of negation, as illustrated by (5a) and (5b) respectively. They also cannot be questioned, as illustrated by (5c) (e.g. Brinton 2008: 7–9; Espinal 1991: 729–735; Haegeman 1991; Mustafa and Kaltenböck 2024; Quirk et al. 1985: 612–613).[3]

| Last I checked , you don’t have a crystal ball. |

| (COHA:2005:FIC:Mov:FantasticFour) |

| *It is/was last I checked that you don’t have a crystal ball. |

| No, that’s not true. (= You have a crystal ball; ≠ I didn’t check) |

| When don’t you have a crystal ball? – *Last I checked. |

As a sign of their syntactic independence, ELI fragments are positionally mobile, allowing for clause-initial position, as in (2), as well as medial, as in (1), and final position, as in (3), and can also occur as a free-standing response signal to a polar question, as in (6).

| A: Does my wife still live above the place? |

| B: Last I heard . |

| (COHA:1966:TV/MOV:TheChase) |

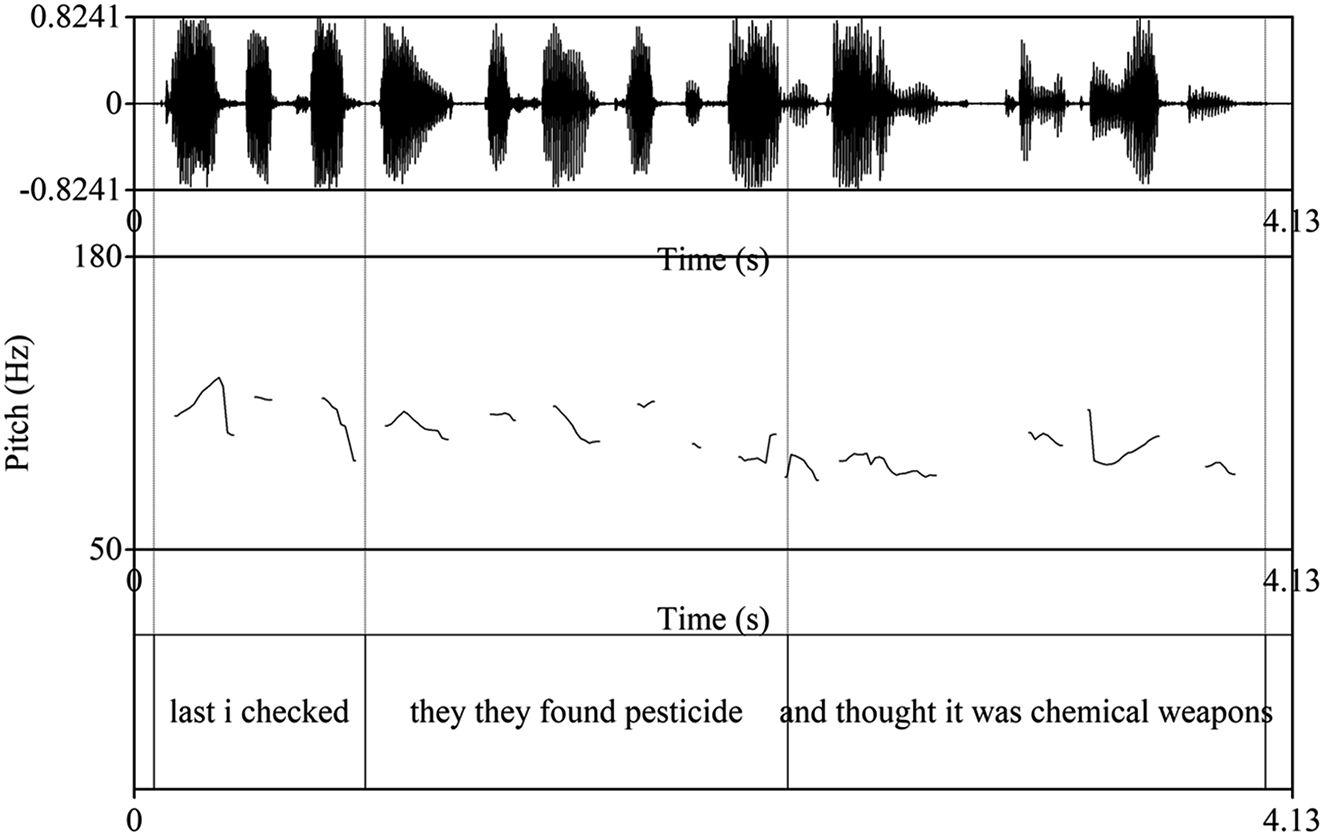

Their lack of syntactic integration is also reflected prosodically: They exhibit their own intonation contour with an intonational boundary separating them from the host clause, as illustrated in (7) with an example from the Fisher Corpus (Cieri et al. 2004–2005) analysed with PRAAT (Boersma and Weenink 2024). In writing, this prosodic independence is typically indicated orthographically with the help of commas.

| last i checked they they found pesticide and thought it was chemical weapons |

| (fe_03_01632) |

|

As fragmentary forms, ELI fragments can be linked to different ‘structurally complete’ forms, which qualify as potential historical sources (see Section 4). Depending on the semantics of the verb involved, these are either specificational sentences, as in (8b), or temporal adjuncts, as in (9b) and (9c). Some ELI verbs (viz. hear, read, saw) allow for both types of reconstruction, as illustrated in (10).

| Last I recall , illegal is illegal |

| (COCA:2012:BLOG:extremetech.com) |

| The last thing (that) I recall is (that) illegal is illegal. |

| Last I looked , you were very adamant about this. |

| (COCA:1991:TV:Law&Order) |

| The last time (that) I looked , you were very adamant about this. |

| When last I looked, you were very adamant about this. |

| Last I read, Nixon was running without an agency. |

| (COHA:2007:TV/MOV:MadMen) |

| The last thing I read was that Nixon was running without agency. |

| The last time I read (about it) , Nixon was running without an agency. |

| When last I read (about it) , Nixon was running without an agency. |

Prior to delving into a detailed examination of the ELI fragment and its complete cognates, it is important to offer a brief clarification of what we mean by specificational sentences. A specificational utterance is a copula construction in which one element (termed the variable) is defined by (or equated in certain respects with) another element (referred to as the value). Consider the more general example in (11), where the subject the two primary writers represents the variable and the subject complement assigns a value, viz. Y.E. Harburg and Noel Langley, to that variable (see e.g. Keizer 1992: 53–82; Van Praet 2022: 69–104).

| The two primary writers are Y.E. Harburg and Noel Langley |

| (COCA:2016:NEWS:cleveland.com) |

The example above under (8) shows that some of our ELI fragments are modelled after the specificational construction as seen in (11). More precisely, the structurally complete form in (8b) is specificational in terms of expressing a value (i.e., illegal is illegal) for a variable (i.e., the last thing I recall). Crucially, it is the broader specificational construction, characterized by a variable-to-value relationship, that we identify as the historical source of our ELI fragments, rather than specific instances with evidential predicates as in (8b) (see Section 4.3).

3 Database and overall frequencies

The present study makes use of the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA; Davies 2010) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies 2008-), which provide large-scale databases of Modern American English and together span the last 200 years to the present day. COHA (last updated in 2021) comprises more than 475 million words and includes texts from the 1820s to the 2010s. The main genres are fiction, non-fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and TV/movie subtitles. COCA (last updated in 2020) contains more than one billion words of text from different genres (e.g. spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, academic texts) from 1990 to 2019.

Retrieval of the ELI fragments was carried out with the search string [last I|we VERB] and subsequently filtered manually to exclude non-evidential predicates as in (12), i.e. other than expressing cognition, sensory perception, or activities of information gathering. Sensory perception verbs were further restricted to those without a direct object or complement, but adjuncts were allowed for (see Section 2).

| BA had a nice lounge in T5 too last I flew them . |

| (COCA:2012:BLOG:urbanophile.com) |

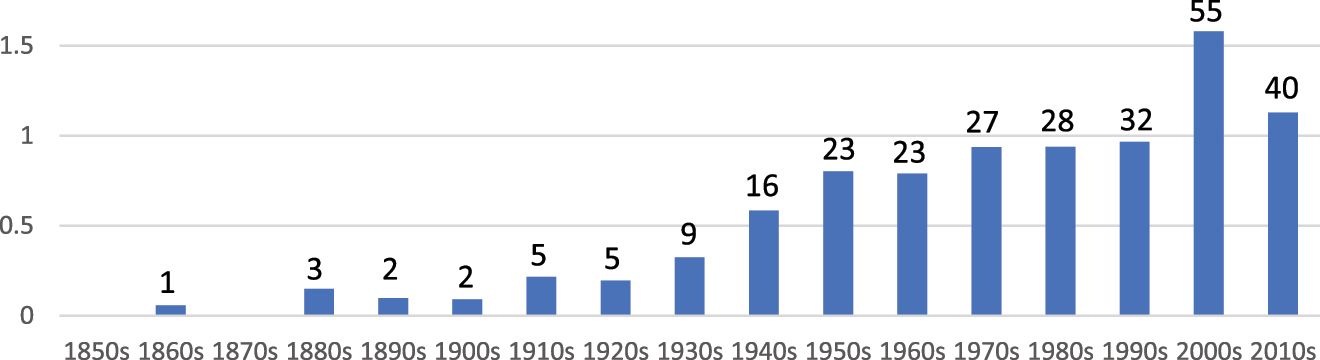

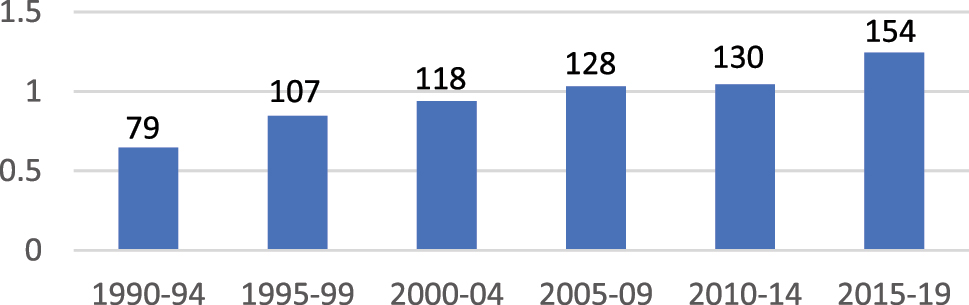

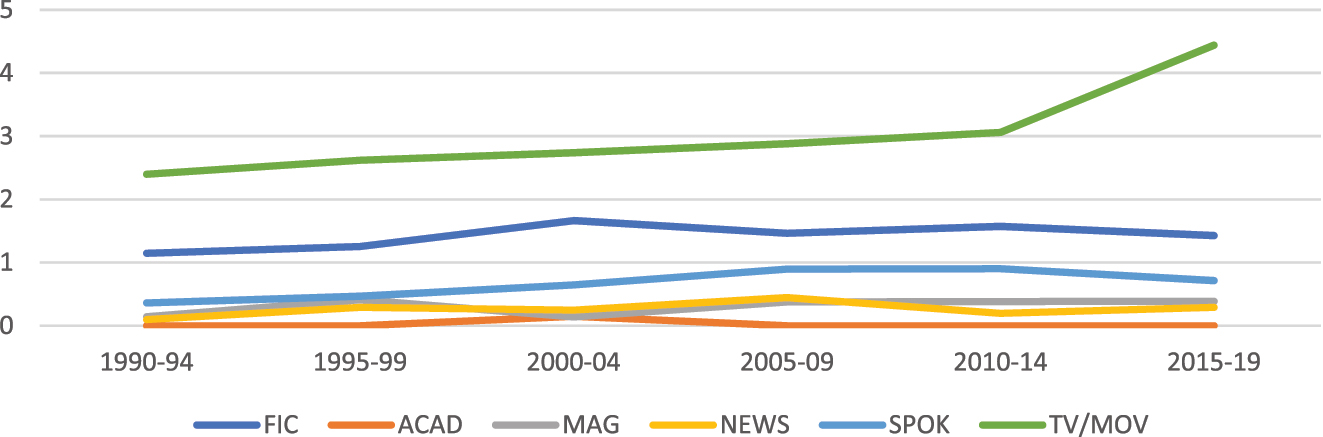

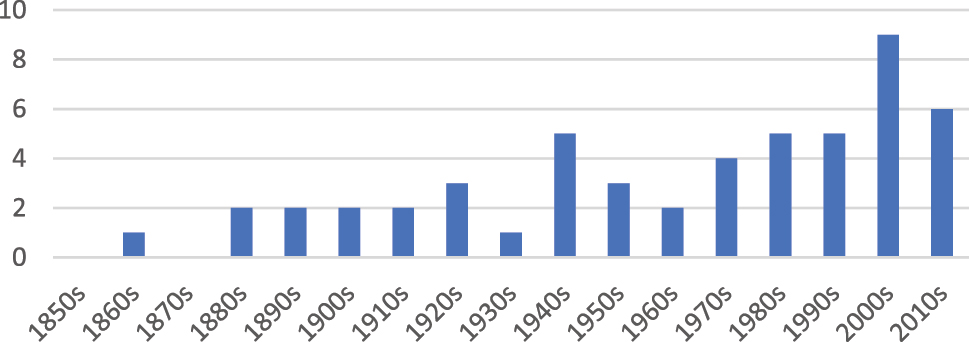

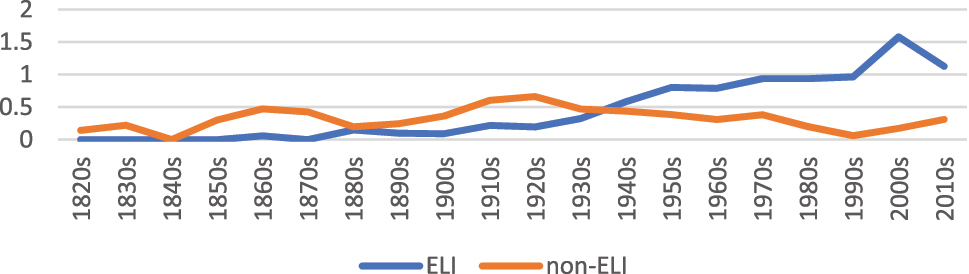

The frequencies of ELI fragments in the two corpora exhibit a clear increase over time. As indicated by Figure 1, ELI fragments are first attested in COHA from the 1860s, with very modest frequencies at first and a slow but steady rise in the course of the 20th century. This trend is continued in the 21st century, as the results for COCA in Figure 2 show. Note that we have excluded the web (1.42 per million words) and blog (2.53 per million words) subsections in Figure 2 since they only feature in the corpus for the year 2012.

Development of ELI fragments in COHA: normalized per 1 million words and raw frequencies.

Development of ELI fragments in COCA (excluding web and blog): normalized per 1 million words and raw frequencies.

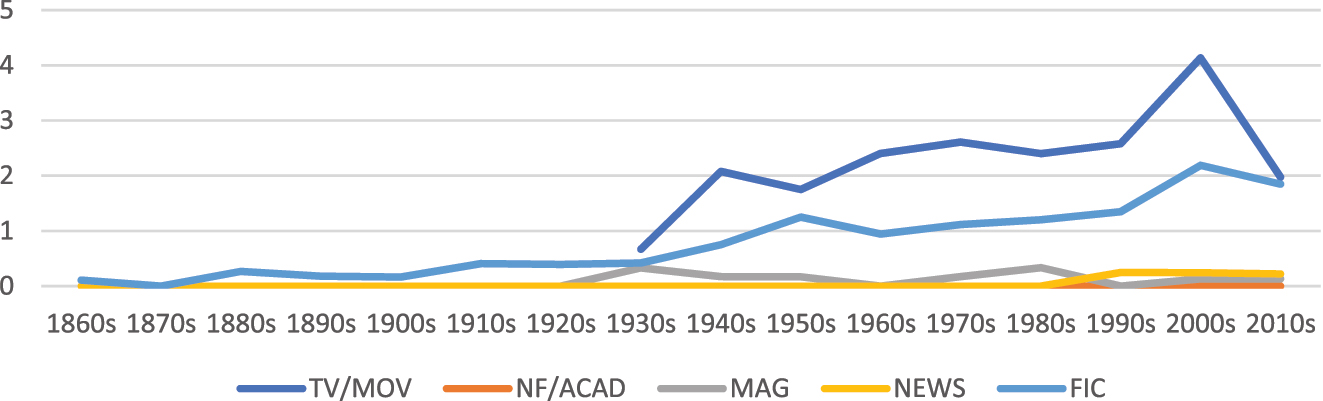

Separating the different genres in COHA reveals that the overall increase in frequency is mainly driven by two text types: fiction and TV/movie (see Figure 3). Similarly high frequencies for fiction and TV/movie can be found in COCA (see Figure 4).

Development of ELI fragments in COHA text types: normalized per 1 million words.

Development of ELI fragments in COCA text types (excluding web and blog): normalized per 1 million words.

Let us compare these frequencies with those of the structurally complete, i.e. non-fragmentary, structures that ELI fragments can be reconstructed as, and as such represent potential historical source constructions:[4] viz. the general specificational construction (expressing a value for a variable) and adjuncts with time and when including non-evidential uses. Both the specificational construction (between 1,434.41 and 6,180.04 per million words) and the temporal adjunct constructions (a total of between 6.85 and 10.12 per million words) substantially outnumber the (evidential and non-evidential) fragmentary form (1.38 per million words), underscoring their qualification as templates for ELI (see also Section 4.3).[5]

As for the predicates used in ELI fragments, both corpora display a very similar range and preference. As shown in Table 1, the most frequent predicate, by far, is heard, followed by checked. The number of different predicates attested is small, with 12 in COHA and 13 in COCA.

Predicates attested for ELI fragments in COHA and COCA.

| COHA | COCA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicate | Frequency | % | Predicate | Frequency | % |

| heard | 191 | 70.5 % | heard | 553 | 45.4 % |

| checked | 31 | 11.4 % | checked | 444 | 36.5 % |

| see(n)/saw | 16 | 5.9 % | looked | 73 | 6.0 % |

| knew/know | 13 | 4.8 % | saw | 51 | 4.2 % |

| looked | 7 | 2.6 % | knew | 44 | 3.6 % |

| remember | 6 | 2.2 % | remember | 18 | 1.5 % |

| counted | 2 | 0.7 % | read | 14 | 1.1 % |

| read | 2 | 0.7 % | recall | 10 | 0.8 % |

| behold | 1 | 0.4 % | counted | 6 | 0.5 % |

| recall | 1 | 0.4 % | noticed | 2 | 0.2 % |

| recollect | 1 | 0.4 % | was measured | 1 | 0.1 % |

| was measured | 1 | 0.4 % | tested | 1 | 0.1 % |

| did the math | 1 | 0.1 % | |||

| TOTALa | 271 | 100 % | TOTAL | 1,218 | 100 % |

-

aOne example was last I saw or heard, which was included for both predicates, but only counted as one instance in the total.

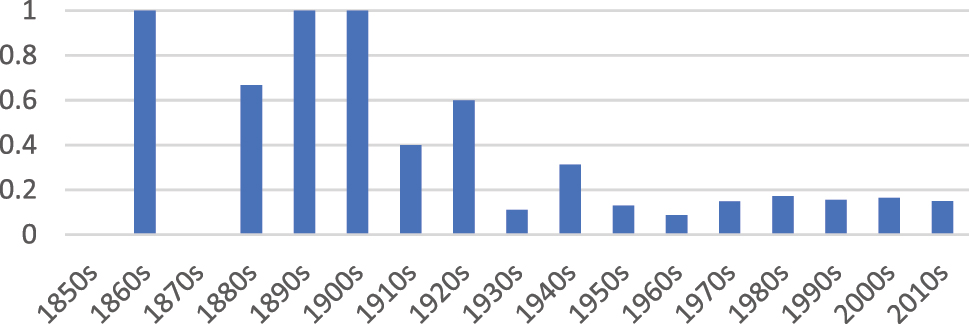

If we look at the development in the use of predicates over time, we note that the number of predicate types gradually increases, which attests to a statistically significant (p < 0.05, r = 0.87) increase in productivity (see Figure 5). At the same time, however, the type-token ratio decreases significantly (p < 0.05, r = −0.83), as a result of increased preference for only some evidential predicates, notably heard and checked, thus attesting to a semantic specialization (see Figure 6).

ELI predicates in COHA: Type frequency.

ELI predicates in COHA: Type-token ratio.

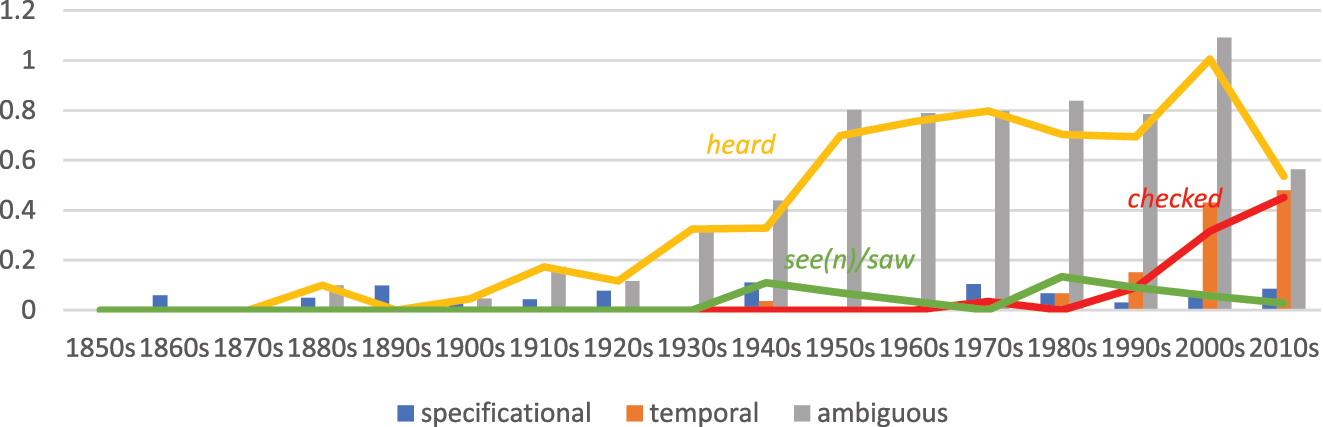

A more detailed look at the development of the individual predicates in COHA provides the following picture of first attestations, as illustrated in Figure 7:

The first attested ELI fragment occurs in the 1860s with remember and is immediately followed by heard (1880s), know (1880s), and behold (1890s). All of these early predicates allow for the reconstruction of specificational sentences (see Section 2), with heard allowing equally for reconstruction of a temporal adjunct (i.e., last thing I heard is… and last time I heard/when last I heard).

Further predicates are added in the 1940s, viz. recollect and see, followed by read in the 1950s, where the former allows for specificational reconstruction and the latter two for both specificational and temporal. This is also the time when we can observe a remarkable increase in frequency for heard.

The 1970s see the introduction of the predicate checked, which is noteworthy for several reasons: it is the first predicate allowing for reconstruction as a temporal adjunct only, it is the first predicate expressing an activity of information gathering, and it exhibits a sharp increase (at the expense of heard). Further late predicates appearing around this time are recall (1980s), looked (1980s), counted (2000s) and was measured (2000s), with recall reconstructing to a specificational sentence and all the others permitting expansion to a temporal adjunct only.[6]

Frequencies (per 1 million words) of the three most frequent ELI predicates (heard, see(n)/saw, checked) and reconstruction types in COHA.

The sequence of predicates outlined above suggests the following stages in the development of ELI fragments. As original source construction we can assume a specificational sentence with a verb of cognition or sensory perception. In the course of the 20th century ELI fragments become, however, increasingly associated with temporal adjuncts (with time and when). This shift in allegiance is brought about or facilitated by a number of factors: (i) the ambiguity of the most frequent predicate, heard, allowing for both types of reconstruction and thus offering a gateway to another template,[7] (ii) the similarity in syntactic status between optional disjuncts (ELI) and typically optional adjuncts (e.g. last time I flew them) as opposed to obligatory specificational subjects (e.g. the last thing I remember is that…), and (iii) the (late) availability of full forms with time/when plus evidential verb as potential templates (see Section 4.3). While not attested before 1900, the full forms with when/time become more frequent than specificational sentences with evidential verbs in the course of the 20th century (see Section 4.3) and thus more readily available as an associative model. The change in allegiance is further cemented by the popularity of checked as an ELI predicate around the beginning of the 21st century.

There are three predicates that stand out in propelling the ELI fragment forward in terms of frequency. These are heard, checked, and, less frequently, saw. The first attestation of each of these predicates point to potential correspondences with language-external events. Heard is first attested in the 1880s followed by a steady and significant rise, which coincides with the beginning of entertainment radio broadcasting in America (around 1910, with the period between the late 1920s and the early 1950s being considered the Golden Age of Radio).[8] Saw, although much less frequent, appeared in the 1940s and coincides with the advances of commercial television in the US.[9] Checked, finally, takes over from heard as the driving agent at the very end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, that is, at a time when the World Wide Web became available to a wider public and allowed for easy checking of facts.[10] We acknowledge, however, that the observed parallels between the first documented instances of the predicates and the corresponding external events remain speculative and require further evidence.

4 Changes in form

Having established the source constructions (Section 2) and general pathway of ELI fragments (Section 3), this section focuses on formal changes over time, as evidenced by the data. First, we examine formal changes of the ELI fragment itself (Section 4.1), then by comparison with non-evidential fragments (Section 4.2.), and finally by comparing ELI fragments with their structurally non-reduced (i.e. full) counterparts.

4.1 ELI fragments

The formal parameters investigated for ELI fragments are (i) the occurrence of determiner omission, (ii) the position of the ELI fragment in relation to its host clause, and (iii) tense agreement or disagreement with the host. We will look at each of these in turn.

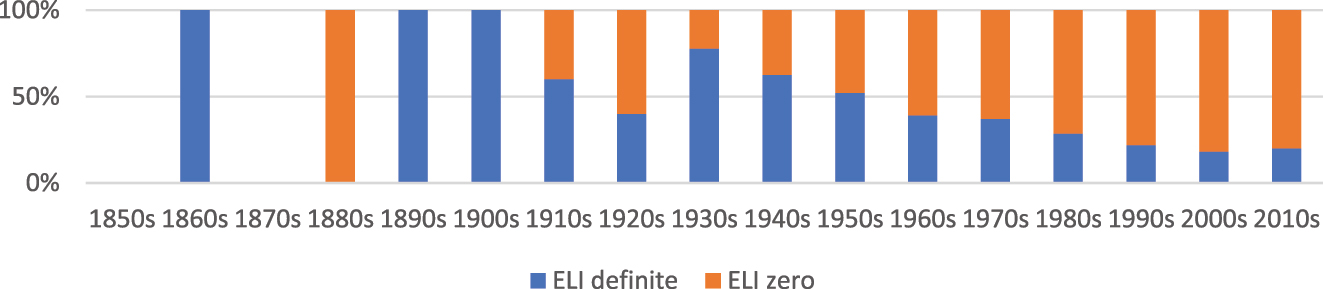

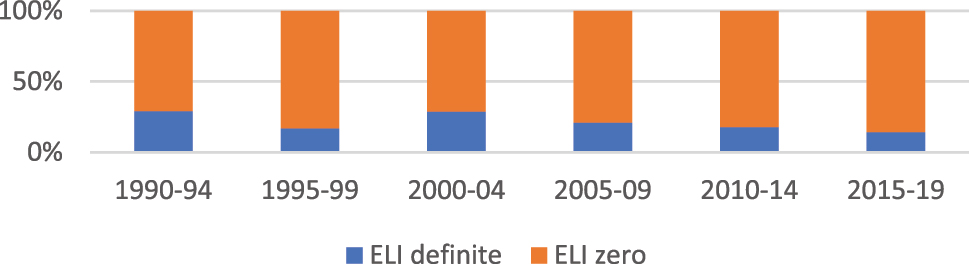

As noted in Section 2, the use of the definite determiner is optional for ELI fragments. The COHA data, given in Figure 8, show that the relative frequency of the determiner reduces significantly (p < 0.05, r = −0.61) in the course of the 20th century. A similar significant reduction (p < 0.05; r = −0.46) is evinced by the COCA data for the 21st century, as indicated in Figure 9. This development can be related to a process of grammaticalization (see Section 6).

Relative frequency of determiner versus zero determiner in ELI fragments in COHA.

Relative frequency of determiner versus zero determiner in ELI fragments in COCA.

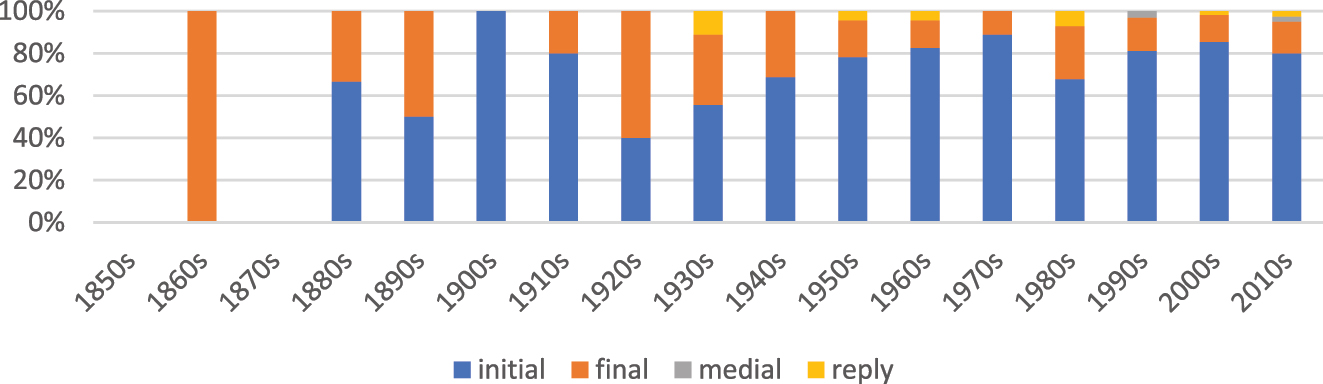

In terms of position, the ELI fragment can occur clause-initially, -medially, and -finally and may also be a free-standing reply, as illustrated in Section 2.[11] The predominant position is clearly the clause-initial one, accounting for a total of 78.2 per cent in COHA and 86.7 per cent in COCA. Diachronically, both initial and final position are attested throughout the COHA data, with the first instance of an ELI fragment occurring in final position (see Figure 10 and example 13). Medial position and free-standing replies, on the other hand, are very rare and occur only later in COHA: free-standing replies from the 1930s (7 instances in total) and only two medial uses in the 1990s and 2010s. The figures for free-standing and medial uses in COCA are similarly low: viz. 21 (1.7 %) and 35 (2.9 %) respectively, as opposed to 1,056 (86.7 %) for initial and 106 (8.7 %) for final position.

Relative frequency of position of ELI fragments with regard to host clause in COHA: initial, medial, final, and free-standing reply.

| “Yes, I know. But where is Morris? He was here the last I can remember .” |

| (COHA:1867:FIC:CameronPridePurified) |

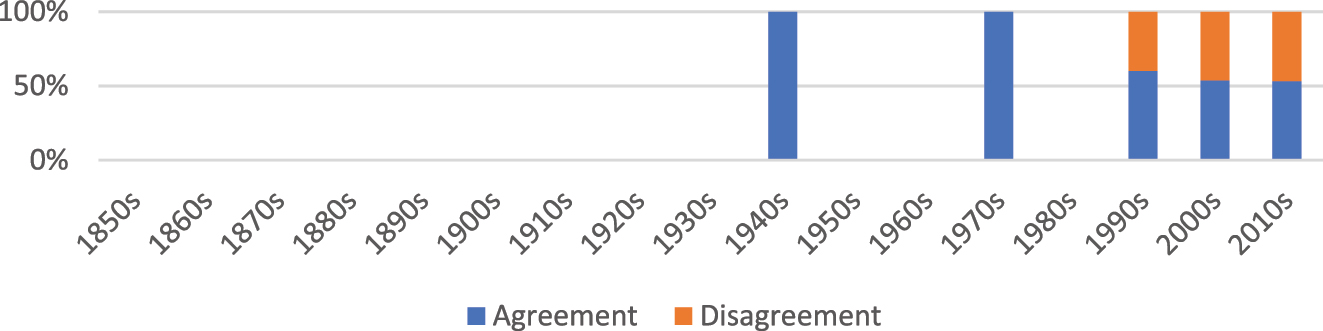

The final formal parameter to be examined is that of tense agreement of the ELI fragment with its host clause. While temporal adjuncts must agree with the tense of their main clause (e.g. Last time I saw John, he was in London), this is not the case with ELI fragments.[12] As illustrated by example (14), they may exhibit disagreement in tense (i.e. no matching tense with the host clause). The COHA data for these ELI fragments show a substantial proportion of disagreement (roughly 50 %), as indicated by Figure 11, suggesting formal dissociation from the host clause and thus underscoring their disjunct status (see cooptation in Section 6).

Tense Agreement of ELI fragments with temporal reconstruction (viz. checked, looked, counted, was measured) in COHA (verbless host clauses or free-standing uses are excluded).

| We live in Ohio. Last I checked , that is the Midwest. |

| (COHA:1993:FIC:PlanetAdventure) |

4.2 Comparing fragments: evidential versus non-evidential

As noted in Section 2, fragmentary form is a defining feature of ELI fragments (hence the term). However, fragmentary form is not limited to evidential predicates only. As the example in (15) illustrates, non-evidential predicates may also occur with reduced (i.e. fragmentary) form.[13]

| Last we spoke , you said Edward coughs up blood. |

| (COHA:2011:FIC:Bk:ThreeMaidsCrown) |

When examining the development of ELI fragments, it is therefore informative to do so against the background of fragmentary forms more generally, i.e. not limited to those with evidential predicates. The present section takes such a semasiological perspective, investigating the different meanings of this fragmentary form.

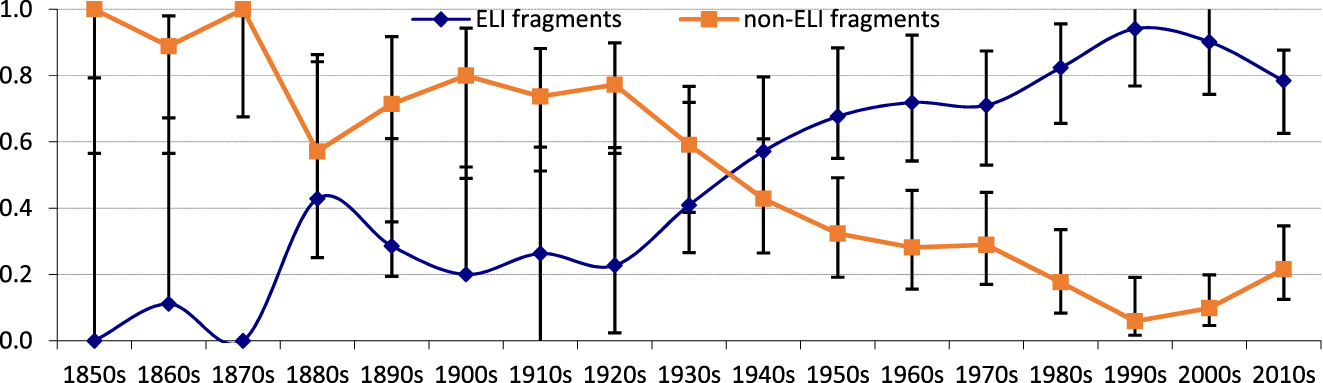

We can compare the development of evidential and non-evidential fragments in COHA against two baselines: their normalized frequencies (i.e. per million words), as illustrated in Figure 12, and their relative frequencies within the set of fragments, as illustrated in Figure 13 (see Wallis 2021). The results show that the development of ELI fragments differs substantially from that of non-ELI fragments in the 20th century. More specifically, the rise of ELI fragments noted in Section 3 takes place against the backdrop of a decline in non-ELI fragments. We can thus identify a semantic shift within the fragments in question to a predominantly evidential use. The inflection point for this semantic specialization is roughly in the 1940s, which marks the beginning of an increase of ELI fragments at the expense of non-ELI fragments.

Frequency of ELI fragments and non-ELI fragments in COHA (pmw).

Relative frequencies of ELI fragments versus non-ELI fragments in COHA (Wilson confidence intervals for p < 0.05; Wallis 2021).

4.3 Comparing evidentials: fragment versus full form

To complement the semasiological view taken in the previous section, we can also adopt an onomasiological perspective, which highlights a speaker’s potential choice between two forms, fragmentary or full, for expressing evidential meaning. As noted in Section 2, the full forms that ELI fragments are associated with are of two types: (i) specificational sentences, such as The thing (that) I remember is (that)…. and (ii) temporal adjuncts taking the form of The last time I checked,… or When last I checked,….

To compare ELI fragments with the full forms, the relevant three structures were retrieved from COHA using the following search strings: (i) last thing (that) I/we VERB, (ii) last time (that/when) I/we VERB, and (iii) when last I/we VERB. These results were then analysed manually to filter out false positives and identify evidential predicates. The category of specificational sentences was defined loosely to also include cases of copula-omission (e.g. The last thing I remember, I was crossing a street in Los Angeles. COHA:1966) and anaphoric pronominal subjects (e.g. And then he hit me, and that’s the last thing I remember. COHA:1963). The category of temporal adjuncts, on the other hand, allowed for omission of the determiner in time headed NPs (e.g. Last time I was here, I hid a stash. COHA:2003).

The first striking observation is the low frequency of evidential full forms in COHA, which account for a total of only 145 instances (of which 42 are specificational, 94 temporal with a time NP, and 9 temporal with a when-clause). Compared to the total of 271 instances of ELI fragments in COHA (see Section 3), the structurally complete alternatives are thus almost half as frequent. In other words, ELI fragments are the preferred option and clearly outnumbers the combined total of all three fully-fledged alternative constructions with evidential predicates. Note, however, that while ELI fragments are more frequent than the evidential full forms, the general specificational and temporal patterns in their full forms substantially outnumber the fragmentary form (i.e., evidential and non-evidential) and as such qualify as templates for ELI (see Section 3).

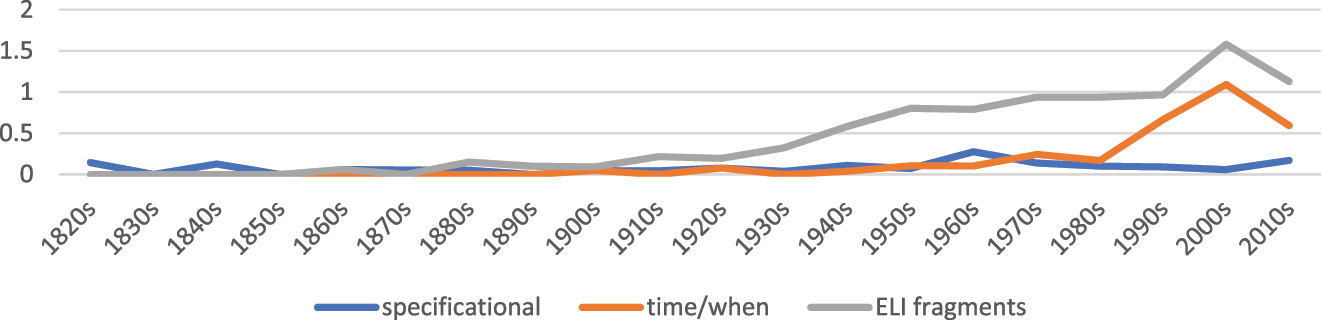

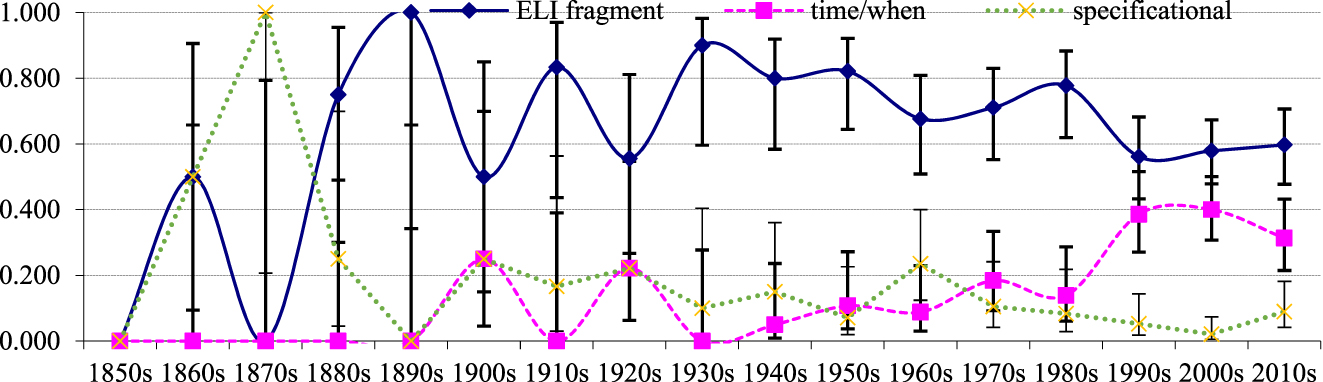

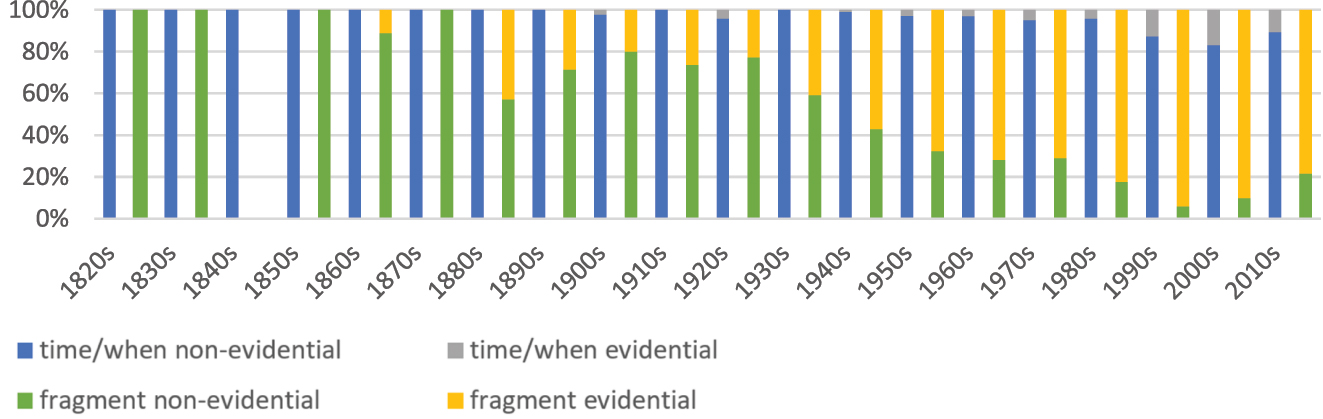

From a diachronic perspective the following picture presents itself. As shown in Figure 14, the normalized frequencies of ELI fragments outnumber the non-fragmentary alternatives with evidential predicate (both specificational and temporal) from the first attestation of ELI in the 1860s. Note that full forms with time or when plus evidential verb are only available as a potential alternative from the 1900s (see Section 3). However, we can observe a rise at the end of the 20th century, running parallel to the increase of ELI fragments. This rapprochement of ELI fragments and corresponding full forms is brought out more clearly by the relative frequencies given in Figure 15 and can be interpreted as a shift in allegiance: Although originally modelled on specificational sentences, ELI fragments later become associated with temporal adjuncts.[14]

Normalized frequencies (pmw) of ELI fragments and two evidential full forms in COHA: specificational sentences (including instances with and without copula and instances with anaphoric pronominal subjects) and time/when structures.

Relative frequencies of ELI fragments versus two evidential full forms in COHA: specificational sentences (including instances with and without copula and instances with anaphoric pronominal subjects) and time/when structures (Wilson confidence intervals for p < 0.05; Wallis 2021).

Despite the closer association of ELI fragments with full temporal adjuncts from the end of the 20th century, it is only the former that exhibit a clear semantic specialization towards evidential uses (see Section 4.2). This is shown in Figure 16, which provides the relative frequencies of evidential uses (i.e., with evidential predicates) as opposed to non-evidential uses for both, fragments ((the) last I/we VERB) and the full forms (the) last time I/we VERB, when last I/we VERB.[15] Fragments dramatically increase their share of evidential predicates in the course of the 20th century to close to 100 per cent. Full (i.e. non-fragmentary), forms with time or when, on the other hand, remain firmly non-evidential, with only a slight increase of evidential uses, but staying well below the 20 per cent mark.

Relative frequencies of evidential (vs. non-evidential) uses of fragments and time/when structures.

4.4 Interim conclusion

Analysis of the corpus data allows us to make the following observations about the development of ELI fragments.

The emergence of ELI fragments is specificationally-driven, being modelled on the structure The last thing I/we VERB is that…. In their later development, however, they adopt temporal adjuncts as a second template, facilitated particularly by the rise in frequency of heard and its ambiguous reconstruction potential (see Section 6 for further discussion).

The rise of ELI fragments also represents a semantic specialization of this fragmentary form (viz. (the) last I/we VERB) towards evidential use. In the course of the 20th century it comes to be predominantly used with evidential predicates.

The potential choice between fragmentary form and full form for evidential predicates is only just that: potential. In terms of actual usage, the alternative full forms (specificational sentences or time/when structures) are less frequent than ELI fragments and as such do not constitute a viable alternative to ELI fragments. Moreover, it is only the fragmentary form that shows a semantic specialization towards evidential use. Full forms with time or when remain firmly non-evidential.

5 Changes in function

Having investigated the formal changes in some detail, this section now turns to the discourse functions of ELI fragments. It is possible to identify both interpersonal and textual functions, which will be discussed in Sections 5.1 and 5.2 respectively.

5.1 Interpersonal functions

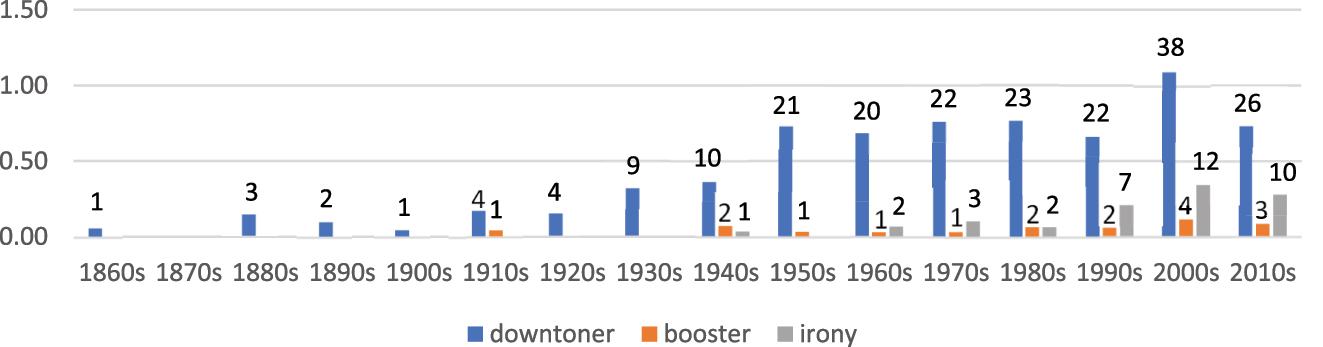

As the name suggests, ELI fragments have evidential meaning, indicating a source of information for the claim made in the associated host clause (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004: 3). By way of epistemic extension, this basic evidential meaning gives rise to different interpersonal uses, expressing speaker attitude (e.g. Aikhenvald 2004: 5; Chafe 1986; Dendale and Tasmowski 2001: 341–343). For Present-day American English three different functions have been identified, viz. downtoner, booster, and ironic use (see Mustafa and Kaltenböck 2024). In the following we briefly explain and illustrate each of them, before turning to their occurrence in COHA.

Downtoner uses (Holmes 1984) hedge the speaker’s commitment with regard to the truth of the proposition in the host clause. This reduction in speaker commitment stems from limited available evidence. In other words, the basic evidential meaning of the ELI fragment (indicating the source of information) is given a reading that highlights the unreliable nature of the information. Such a reading can be attributed to the temporal lag in information update expressed by last (which implies potential change) as well as a potential insecurity associated with the source of information itself, e.g. hearing, seeing, or remembering. In this use, the ELI fragment can be replaced by hedges such as, as far as I know or apparently. An example is given in (16).

| I ain’t seen him for more’n twelve years. He was to the war in France – last we heard . |

| (COHA:1921:FIC:Play:Hero) |

Booster uses (Holmes 1984), on the other hand, convey emphasis. They put the evidential meaning of ELI fragments to exactly the opposite use by foregrounding the reliability of the source of information and thus the validity of the proposition in the host clause. In this use, the ELI fragment can be substituted by assertive expressions of the type let me emphasize. What may trigger this specific reading is a context where the speaker expresses a confrontational or emotionally charged stance. The host clause may also express some form of exaggeration or a generally known state of affairs that does not require any evidence. An examples of this function is given in (17).

| I’ll throw the honky out. Taylor, come on. Now, if you just give me a chance – Percell, it ain’t funny! What are you doing coming in a place like that? What are you doing in a place like that? The last I looked , I was saving your butt. |

| (COHA:1990:TV/MOV:Tour_of_Duty) |

Ironic use, finally, exploits a pragmatic incompatibility of the ELI fragment with the host clause. An ironic reading may thus arise in cases where the meaning of variability implied by last in the ELI fragment (e.g. last I checked), which suggests that a state of affairs may have changed since the information was obtained, clashes with a host clause that expresses a state of affairs that is not variable, i.e. an immutable fact or a permanent state. This function is illustrated in (18).

| His oncologist suggested marijuana to increase his appetite. That’s all it was. And so your smoking pot with him helped him how, exactly? I mean, last I checked , you don’t share a stomach. |

| (COHA:2006:TV/MOV:Everwood) |

The boundaries between the three functions are of course not always clear-cut and, as is to be expected with pragmatic markers, we have to allow for multifunctionality (esp. the simultaneous expression of boosting and irony). What also affects the analysis of the discourse functions is the lack of unscripted spoken texts in COHA, as it is spoken interaction that makes most frequent use of pragmatic markers to regulate the exchange between interlocutors (see Aijmer 2013).

The above caveats notwithstanding, the COHA data were classified with regard to the most prominent discourse function of each ELI fragment. The results, given in Figure 17, show that the downtoner function is most frequent and the earliest use.[16] The booster function is much less frequent (presumably because of the absence of spoken interaction in COHA) and attested for the first time in the 1910s with example (19) and then in the 1940s with example (20).

Discourse functions of ELI fragments in COHA; per million words and raw frequencies.

| HOWE: I’ve got – Feeling something unusual. Sorry to butt in, but I can still get that job on The Evening World. If this paper is going to stop, I’ve got to know it. |

| WILLS: Stop! This paper can’t stop! |

| HOWE: Can’t stop! Last I heard , it couldn’t do anything else. |

| (COHA:1917:FIC:Play:People) |

| CORPORAL HERMANN GEIST: Casablanca is in German hands. You are already cut off here in the Mediterranean. You were fools to venture into the Mediterranean, you Americans, for now we have the west coast and you will never get out. I shall be recaptured. |

| SERGEANT PETER MOLDAU: The last I heard Casablanca was the main port of entry for American supplies. |

| (COHA:1944:FIC:Play:StormOperation) |

Ironic use is also relatively infrequent and first attested in the 1940s with example (21) and further examples in the 1960s, for instance (22).

| # Sir: # … . TIME Aug. 22 calls St. James Philosophers Barbee a ”prize bull.” Last I heard , she was still a cow. Quoting your article, ”she’s a lady and should be treated as such”… # |

| (COHA:1949:MAG:Time) |

| What would I use for money? The last I heard they were still selling booze not giving it away. |

| (COHA:1962:TV/MOV:LongDay’sJourney) |

We can thus identify the following order of first attestation of the three discourse functions: Downtoner > booster > ironic use. While the downtoner function is attested already for the earliest uses of ELI fragments in the late 19th century, the booster function and ironic use are later developments, attested in COHA from the 1910s and the 1940s respectively.

5.2 Textual functions

In addition to the interpersonal functions discussed in the preceding section, ELI fragments may also adopt text-organisational functions, depending on their position with respect to the host clause. These functions typically come into effect in conversational interaction, where they help the speaker to structure the spoken discourse.

The preferred position for ELI fragments is that of left-periphery, that is, preceding their host clause (see Section 4.1). This position may be used for indicating a topic shift, which is effected in the host clause. The ELI fragment thus announces that the speaker tries to steer the conversation into a new direction, towards a new topic or a sub-topic, as illustrated in (23). This may also coincide with a new speaker turn, as in (24).

| We’re joined by Robert Costa, national political reporter for The Washington Post. Robert, thank you very much. The last we heard , Devin Nunes wasn’t going to recuse himself. You talked to him today. What changed? |

| (COCA:2017:SPOK:PBS_Newshour) |

| COLMES: Ann, welcome back. |

| COULTER: Thank you. |

| COLMES: Last I checked , we have a representative form of government. People seem to want us – all the polls show, they want us out of there… |

| (COCA:2007:SPOK:Fox_HC) |

Less frequently, ELI fragments occur in right-periphery, that is, following the host clause. This position lends itself to indicating the end of a topic, as in (25), and may also coincide with the end of a speaker’s turn, as in (26).

| They had to drive the chopper three-quarters of a mile with her dangling that way with the kid rescued. Now the 16-year-old, Jason Gelroth, remains in critical condition last – last we heard . My next guest – take a look at him. There he is; take a look. |

| (COCA:1996:SPOK:Ind_Geraldo) |

| Immigration-Attorney: It’s a military internment camp. And we don’t run those in the United States of America last I heard . |

| MANUEL-BOJORQUEZ: Caliburn, the private company paid by DHS to run Homestead issued a statement that the candidate visits are attempts to “mislead the public and score political points.” |

| (COCA:2019:SPOK:CBS_Morning) |

Although rare, medial position is also attested in more recent decades. Such uses typically have an information structuring function, separating topic and comment, postponing focal information and thereby highlighting it (e.g. Taglicht 1984), as in (27).

| Cocaine users, last I heard , are prone to distorting the truth. |

| (COCA:2000:TV:Law&Order:Special…) |

Although no historical conversational data are available to investigate the development of these functions, we can assume that these text-organisational functions are later developments, which have emerged as an additional functional layer.

6 Mechanisms of change

Having outlined the diachronic changes of ELI fragments in some detail in Sections 3 to 5, this section now tries to account for them in terms of general processes of change. The following can be identified as playing a central role.

Grammaticalization triggered by cooptation: Grammaticalization is a well-established diachronic process, which is frequently evoked also in connection with the development of pragmatic markers (e.g. Boye and Harder 2021; Brinton 2008, 2017; Heine et al. 2021; López-Couso and Méndez-Naya 2021; Thompson and Mulac 1991; Traugott 1997 [1995]). What points to grammaticalization as a process for the development of ELI fragments is the overall increase in token frequency, increasing omission of the determiner (as a result of internal decategorialization or univerbation), semantic specialization (see below), and the development of different pragmatic functions ranging from interpersonal to textual (cf. e.g. Brinton 2017: 165; Brinton and Traugott 2005: 110; Heine and Kuteva 2007: 33–46; Lehmann 2015 [1982]: 129–188).

In addition, ELI fragments also show syntactic independence from the host clause with concomitant positional mobility. Syntactic independence, however, is difficult to reconcile with (a narrow view of) grammaticalization and has therefore been argued to result from cooptation (see Heine 2013; Heine et al. 2021; Kaltenböck et al. 2011). Cooptation is “a cognitive–communicative operation whereby a text segment such as a clause, a phrase, or a word is transferred from the domain or level of sentence grammar and deployed for use on the level of discourse organization” (Heine et al. 2021: 26). Once coopted, such a text segment no longer relates to the propositional content of the sentence but instead its meaning is shaped by the situation of discourse. Syntactically, cooptation creates an extra-clausal element, which means it is no longer a syntactic constituent of its host sentence, and as such is positionally mobile, typically set off prosodically, and has wider semantic–pragmatic scope. Coopted elements may be elliptical (see Heine et al. 2017), as is the case with ELI fragments. What supports a cooptation hypothesis for ELI fragments is that their first attestation (with specificational reconstruction) is in clause-final position (see Section 4.1).[17] They are thus attested from their very beginning as clear disjunct units, which can best be accounted for by instantaneous cooptation rather than a gradual weakening of syntactic bonds.[18]

On this hypothesis, then, the rise and development of ELI fragments is the joint product of two distinct mechanisms: Cooptation, which sets them apart as independent and positionally mobile units for metatextual purposes, and subsequent grammaticalization, which accounts for their internal structure and the different functions they express (Heine 2013: 1238–1239; Heine et al. 2021: 26–27).

Semantic specialization: As noted in Section 3, the rise in overall frequency of ELI fragments goes hand in hand with an increasing preference for some evidential predicates, notably heard and checked. This development has been identified as a case of semantic “specialization”, that is, a “narrowing of choices that characterizes an emergent grammatical construction” (Hopper 1991: 21). Interestingly, this specialization may reflect extra-linguistic developments, namely the availability of new information technologies in the 20th century, specifically the radio (last I heard), TV (last I saw), and the internet (last I checked). From the perspective of fragments more generally, the reduced form (the) last I/we VERB becomes increasingly associated with evidential predicates (with a notable shift taking place in the middle of the 20th century), thus representing another layer of semantic specialization.

Multiple source constructions with a shift in allegiance: The original source construction for the coopted ELI fragments has been identified as specificational sentences, viz. The thing I remember/heard is that … (see Section 3). Towards the end of the 20th century, however, ELI fragments become increasingly associated with another unreduced structure: temporal adjuncts of the type The last time I checked,… ELI fragments can thus be said to be modelled on two templates or “multiple source constructions” (see Van de Velde et al. 2013) with a shift over time from one to the other.

This process of a “shift in allegiance” closely resembles what has been called “constructional contamination” (see Pijpops and Van de Velde 2016; Pijpops et al. 2018), which is the effect whereby “a subset of instances of a target construction deviate in their realization, due to a superficial resemblance they share with instances of a contaminating construction” (Pijpops and Van de Velde 2016: 543). The reason for referring to this process as “shift in allegiance” (cf. Bolinger 1972: 37, who uses the term in a different context) instead is that “constructional contamination” operates on constructions (in the Construction Grammar sense, e.g. Goldberg 2006), whereas ELI fragments are best described as “constructionalizing” rather than full-blown constructions (see Mustafa and Kaltenböck 2024).

The reasons for the associative shift from specificational sentences to temporal adjuncts are multiple and of different kinds. First, there is a perceived similarity in syntactic status between disjuncts (such as ELI fragments) and (temporal) adjuncts, both of which are external to the core structure of a sentence (albeit to varying degrees) and allow for positional mobility. The difference between adjuncts and disjuncts notwithstanding (see Quirk et al. 1985: 1070–1072), what matters here is only the “superficial links” (Pijpops and Van de Velde 2016: 548), that is, strings similar at the surface level, irrespective of actual syntactic differences (see also Fischer [2007, 2015] on analogy as the main principle in grammar formation). Second, temporal adjuncts with the form last time I/we + evidential verb, which are not attested in COHA before 1900, become more frequent than specificational sentences with evidential verbs in the course of the 20th century (see Section 4.3) and thus are more readily available as an associative model (see Fischer [2015] on the role of frequency in analogy). Third, the shift in allegiance is facilitated, if not initiated, by the ambiguity of the most frequent ELI predicate, heard, which allows for reconstruction of both specificational sentences and temporal adjuncts (see Sections 2 and 3). The use of heard can thus be seen as acting as a bridge or gateway between the two source constructions.

7 Conclusions

Fragmentary forms, such as the one investigated, typically allow reconstruction of a non-fragmentary complete structure. This is interesting from a diachronic perspective as the non-reduced full form may qualify as a source construction. In the case of ELI fragments the original source construction was identified as the subject of a specificational construction, e.g. The last thing I remember is that… Although originally modelled on this construction from their first attestations in the 19th century, ELI fragments have over time come to be more closely associated with another non-reduced structure, viz. temporal adjuncts such as The last time I checked,… This re-orientation of ELI fragments in the course of their emergence (leading them potentially to fully-fledged constructional status) towards a second template structure has been referred to as a “shift in allegiance”, which bears close resemblance to the concept of “contamination”, as postulated for firmly established constructions (e.g. Pijpops and Van de Velde 2016).

Other processes identified in the emergence and development of ELI fragments are cooptation (Heine et al. 2021), which can account for the instantaneous re-deployment of a specificational subject as an extra-clausal unit for meta-textual purposes, and subsequent grammaticalization, which takes care of fragment-internal changes such as the increasing omission of the determiner, semantic specialization towards certain predicates, and expanding pragmatic functions, both interpersonal (downtoner, booster, ironic use) and textual (indicating topic shift or end of topic).

The fragmentary form (the) last I/we VERB, more generally, has been shown to specialize in evidential use, with non-evidential verbs becoming increasingly rare in this string. This means that the reduced form has become an important marker for evidential (and epistemic) function. The potential choice between full and fragmentary form is thus not an open one, but semantically constrained. Unlike fragments, the full form remains firmly non-evidential and also comparatively infrequent.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and the editors of the special issue, Matthias Klumm and Augustin Speyer, for their support in the editorial process. Special thanks also go to the participants of the linguistic colloquium 2024 at the University of Graz, where a previous version of the paper was presented.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Aijmer, Karin. 2013. Understanding pragmatic markers: A variational pragmatic approach. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748635511Search in Google Scholar

Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199263882.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Boersma, Paul & David Weenink. 2024. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer program]. Version 6.1.42. Available at: www.praat.org.Search in Google Scholar

Bolinger, Dwight. 1972. That’s that. The Hague & Paris: De Gruyter Mouton.Search in Google Scholar

Boye, Kasper & Peter Harder. 2021. Complement-taking predicates, parentheticals and grammaticalization. Language Sciences 88. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2021.101416.Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel J. 2008. The comment clause in English: Syntactic origins and pragmatic development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511551789Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel J. 2017. The evolution of pragmatic markers in English: Pathways of change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316416013Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel J. & Elizabeth Closs Traugott. 2005. Lexicalization and language change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511615962Search in Google Scholar

Chafe, Wallace L. 1986. Evidentiality in English conversation and academic writing. In Wallace L. Chafe & Johanna Nichols (eds.), Evidentiality: The linguistic encoding of epistemology, 261–272. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Search in Google Scholar

Cieri, Christopher, David Graff, Owen Kimball, Dave Miller & Kevin Walker. 2004–2005. Fisher English training speech part 1–2, speech & transcripts. Web download. Philadelphia: Linguistic Data Consortium.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2008–. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA): One billion words, 1990–2019. Available at: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2010. The corpus of historical American English (COHA). Available at: https://www.english-corpora.org/coha/.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2016–. Corpus of News on the Web (NOW). Available at: https://www.english-corpora.org/now/.Search in Google Scholar

Dendale, Patrick & Liliane Tasmowski. 2001. Introduction: Evidentiality and related notions. Journal of Pragmatics 33. 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(00)00005-9.Search in Google Scholar

Dik, Simon C. 1997. The theory of functional grammar, part 2: Complex and derived constructions. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110218374Search in Google Scholar

Espinal, Teresa M. 1991. The representation of disjunct constituents. Language 67(4). 726–762. https://doi.org/10.2307/415075.Search in Google Scholar

Fischer, Olga. 2007. Morphosyntactic change: Functional and formal perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199267040.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Fischer, Olga. 2015. An inquiry into unidirectionality as a foundational element of grammaticalization. On the role played by analogy and the synchronic grammar system in processes of language change. In Hendrik De Smet, Lobke Ghesquière & Freek Van de Velde (eds.), On multiple source constructions in language change, 43–61. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/bct.79.03fisSearch in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane. 1991. Parenthetical adverbials: The radical orphanage approach. In Shukin Chiba, Akira Ogawa, Norio Yamada, Yasuaki Fuiwara, Osama Koma & Takao Yagi (eds.), Aspects of modern English linguistics. Papers presented to Masamoto Ukaji on his 60th birthday, 232–254. Tokyo: Kaitakushi.Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd. 2013. On discourse markers: Grammaticalization, pragmaticalization, or something else? Linguistics 51(6). 1205–1247. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2013-0048.Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd & Tania Kuteva. 2007. The genesis of grammar: A reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199227761.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd, Gunther Kaltenböck, Tania Kuteva & Haiping Long. 2017. Cooptation as a discourse strategy. Linguistics 55(4). 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2017-0012.Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd, Gunther Kaltenböck, Tania Kuteva & Haiping Long. 2021. The rise of discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108982856Search in Google Scholar

Holmes, Janet. 1984. Modifying illocutionary force. Journal of Pragmatics 8. 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(84)90028-6.Search in Google Scholar

Hopper, Paul J. 1991. On some principles of grammaticization. In Elizabeth Closs Traugott & Bernd Heine (eds.), Approaches to grammaticalization, vol. 1, 17–35. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Kaltenböck, Gunther, Bernd Heine & Tania Kuteva. 2011. On thetical grammar. Studies in Language 35(4). 848–893. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.35.4.03kal.Search in Google Scholar

Kaltenböck, Gunther, Evelien Keizer & Arne Lohmann. 2016. Extra-clausal constituents: An overview. In Gunther Kaltenböck, Evelien Keizer & Arne Lohmann (eds.), Outside the clause, 1–26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.178.01kalSearch in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien. 1992. Reference, predication, and (in)definiteness in Functional Grammar: A functional approach to English copular sentences. Amsterdam, Vrije: Universiteit Amsterdam Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Lehmann, Christian. 2015 [1982]. Thoughts on grammaticalization, 3rd edn. (Classics in Linguistics, 1). Berlin: Language Science Press.10.26530/OAPEN_603353Search in Google Scholar

López-Couso, María José & Belén Méndez-Naya. 2014. From clause to pragmatic marker: A study of the development of like parentheticals in American English. Journal of Historical Pragmatics 15(1). 66–91. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhp.15.1.03lop.Search in Google Scholar

López-Couso, María José & Belén Méndez-Naya. 2021. From complementizing to modifying status: On the grammaticalization of the complement-taking-predicate-clauses chances are and odds are. Language Sciences 88. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2021.101422.Search in Google Scholar

Mustafa, Ozan & Gunther Kaltenböck. 2024. Last I heard: On the use of evidential last I fragments. English Language and Linguistics 28(3). 589–612. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1360674324000297.Search in Google Scholar

Peterson, Peter. 1999. On the boundaries of syntax: Non-syntagmatic relations. In Peter Collins & David Lee (eds.), The clause in English: In honour of Rodney Huddleston [Studies in Language Companion Series, 45], 229–250. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.45.16petSearch in Google Scholar

Pijpops, Dirk & Freek Van de Velde. 2016. Constructional contamination: How does it work and how do we measure it? Folia Linguistica 50(2). 543–581. https://doi.org/10.1515/flin-2016-0020.Search in Google Scholar

Pijpops, Dirk, Isabeau De Smet & Freek Van de Velde. 2018. Constructional contamination in morphology and syntax: Four case studies. Constructions and Frames 10(2). 269–305. https://doi.org/10.1075/cf.00021.pij.Search in Google Scholar

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech & Jan Svartvik. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Taglicht, Josef. 1984. Message and emphasis: On focus and scope in English. London & New York: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, Sandra A. & Anthony Mulac. 1991. A quantitative perspective on the grammaticalization of epistemic parentheticals in English. In Elizabeth Closs Traugott & Bernd Heine (eds.), Approaches to grammaticalization, vol. 2, 313–329. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 1997 [1995]. The role of the development of discourse markers in a theory of grammaticalization. Paper presented at ICHL XII, Manchester, 1995. Available at: https://web.stanford.edu/∼traugott/papers/discourse.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2022. Discourse structuring markers in English. A historical constructionalist perspective on pragmatics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cal.33Search in Google Scholar

Van de Velde, Freek, Hendrik de Smet & Lobke Ghesquière. 2013. On multiple source constructions in language change. Studies in Language 37(3). 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.37.3.01int.Search in Google Scholar

Van Praet, Wout. 2022. Specificational and precative clauses: A functional-cognitive account. (Topics in English Linguistics, 112). Berlin & Boston: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110771992Search in Google Scholar

Wallis, Sean. 2021. Statistics in corpus linguistics research. A new approach. New York & London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429491696Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Left and right peripheries in discourse: an introduction

- Articles

- Between core and periphery: the development in English of a modal adverb, an evaluative adverb and a discourse connector

- The emergence of last I checked fragments: a story of shifting allegiance

- Left-peripheral bottom line sequences

- Peripheral versus non-peripheral optative particles

- Adverbials in Extra-left position in spoken Danish

- Right-peripheral subjects in German and Persian across registers

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Left and right peripheries in discourse: an introduction

- Articles

- Between core and periphery: the development in English of a modal adverb, an evaluative adverb and a discourse connector

- The emergence of last I checked fragments: a story of shifting allegiance

- Left-peripheral bottom line sequences

- Peripheral versus non-peripheral optative particles

- Adverbials in Extra-left position in spoken Danish

- Right-peripheral subjects in German and Persian across registers