Abstract

The paper focuses on the pace of grammaticalization in (a number of varieties of) Piedmontese, a northwestern Italo-Romance language (which includes a regional koiné and several dialectal varieties), and compares it to the geographically closest languages conventionally discussed in the literature on the Romance grammaticalization cline (RGC): French and Italian. I examine the speed of grammaticalization in Piedmontese with respect to four grammatical domains previously analyzed for national languages in the literature on RGC, namely perfective auxiliaries, indefinite articles, demonstratives, and negation. The data show that Piedmontese varieties are on a par with, or even slightly ahead of, French along the Romance grammaticalization cline. While helping to explain why some languages appear to be more grammaticalized than others within the same genealogical family, these findings contribute to advancing our understanding of the role of language-external factors in the grammaticalization process: contact with other languages and the strength of social ties among speakers appear to be more important in favoring grammaticalization than early urbanization or the size of the speaker community.

1 Introduction

The proposal of a Romance grammaticalization cline (RGC, also referred to as the pace, rhythm or gradualness of grammaticalization in the Romance languages) has given rise to a vast body of research since the publication of pioneering work by Lamiroy (1999). The findings of these studies have recently been summarized in Lamiroy and De Mulder (2011), Carlier et al. (2012a), and De Mulder and Lamiroy (2012).

The RGC hypothesis suggests that languages belonging to the same linguistic family, such as the Romance languages, grammaticalize at different speeds. For the majority of grammaticalization phenomena, such as word order, the encoding of motion events, adversative connectives, the use of the subjunctive, the evolution of the prepositional system, etc. (see Carlier et al. 2012b; Fagard and Mardale 2012; Giacalone Ramat and Mauri 2012; Iacobini 2012; Lahousse and Lamiroy 2012), Romance languages can be situated along a scale, where French is ahead of Italian and Italian is ahead of Spanish. These findings are visualized in (1) (adapted from Lamiroy and De Mulder 2011; Carlier et al. 2012a: passim; De Mulder and Lamiroy 2012: 200):

| more grammaticalized | less grammaticalized | ||

| |||

| French | Italian | Spanish | (Latin) |

To date, however, less attention has been paid to non-national Romance languages, although they are numerous and, in some cases, extremely vital across the Romance territory. In the continental European tradition of sociolinguistics, independent languages that are “spoken in a given place or region in concomitance with a more prestigious superimposed […] standard language” (Berruto 2010: 230), such as Piedmontese, Sicilian or Venetan (vis-à-vis Italian), are usually referred to as dialects (dialectes, Dialekte, dialetti). For English-speaking and non-European linguists, on the other hand, the term dialects does not refer to separate languages, but rather to (sub)varieties of a single language (see, e. g., Trudgill 2002: 165). For the sake of clarity, I will use the label (regional or minority) languages throughout this paper to refer to those linguistic systems that are different from the official language(s) of a given nation state, and that are traditionally used by a group of nationals smaller than the rest of that nation state’s population. [1] Varieties of the same language will be referred to as dialects. Dialects may be geographical or social (see Trudgill 1994: 2) or situational (also called styles, see Trudgill 1994: 10). By way of example, American English is a geographical dialect of English, Black English is a social dialect of English, and colloquial French is a situational dialect of French. Varieties of dialects will be indicated with the term sub-dialects.

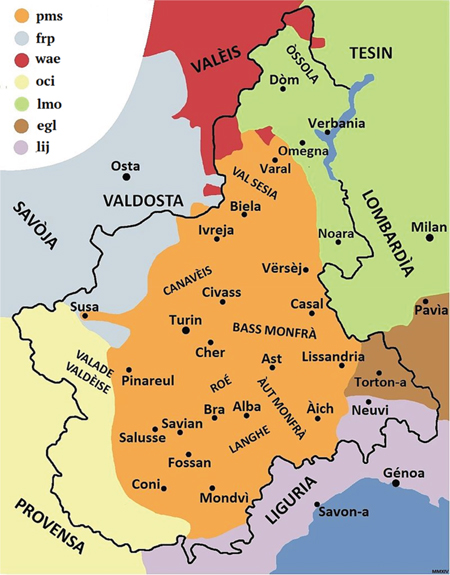

This article will focus on the pace of grammaticalization in (a number of dialects of) the Piedmontese language. Piedmontese (or Piemontese, or, as its speakers call it, Piemontèis) is a regional language spoken in the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy (for an overview of Piedmontese, see Telmon 1988; Parry 1997; Clivio 2002). [2] The region’s chief town is Turin, which was also the capital of the entire Kingdom of Italy from the Unification of Italy in 1861 until 1865. Until the second half of the 20th century, Piedmontese was the mother tongue of nearly all Piedmontese people (except for those living in the Provençal, Walser and Franco-Provençal valleys and in the environs of Novara), who often also had some command of French, Italian, and other local non-Piedmontese varieties (see, e. g., Telmon 2001: 37–38, Marazzini 2012). Nowadays, Piedmontese is probably spoken by 700,000 people in Piedmont and along the borders of that region (Regis 2012a: 93). However, in everyday life, virtually all Piedmontese speakers also, or predominantly, use Italian now, which was previously, at least until the 1950s, limited to cultural, literary, and scientific domains. Despite the fact that Piedmontese has a standard script, used, for example, in the regional edition of Wikipedia, a rich literature, and a grammatical tradition that dates back to the mid/late-18th century, it has never been an official language of any nation state, nor has it ever been taught in schools as part of compulsory education. Recent efforts to revitalize the language have had little success. It therefore still lacks a proper standard variety. Nonetheless, during the 18th century, Piedmontese developed a koiné, mainly corresponding to the Turinese variety (Clivio 2002: 151–152; Regis 2012b: 10–15). Moreover, its geographical dialects, such as High and Low Piedmontese, and their sub-dialects, such as Asti Piedmontese, Biella Piedmontese, Monferrato Piedmontese, etc. (see Telmon 1988, http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/piem1238, http://www.ethnologue.com/language/pms), are also identifiable and of interest: some of them will be taken into account in the course of this paper. The map in Figure 1 (courtesy of Francesco Rubat Borel) shows the geographical extension of Piedmont, the regional and/or minority languages spoken there and in the neighboring areas, along with the Piedmontese names of towns and some sub-dialect areas. The latter are in small caps. The names of the regions bordering on Piedmont are in capital letters. [3]

Map of the regional or minority languages spoken in Piedmont and neighboring areas.

In the following sections, I compare Piedmontese to the geographically closest languages conventionally discussed in the literature on the RGC: French and Italian. Specifically, I examine the speed of grammaticalization in Piedmontese in four morphosyntactic domains which have already been investigated for national languages in the literature on the RGC, namely demonstrative adjectives (see Section 2), negation (Section 3), perfective auxiliaries (Section 4), and plural indefinite articles (Section 5). The analysis relies on data from my own fieldwork and from previous studies on Piedmontese, as well as from a selected corpus of Piedmontese texts ranging from 1321 to the present day.

The data shows that the Piedmontese koiné or other Piedmontese varieties are frequently to be situated at the same stage as, or are even slightly ahead of, French on the RGC. These findings complement De Mulder and Lamiroy’s (2012: 219–221) view about the role of language-external factors in grammaticalization processes: the view proposed here (Section 6) is that contact with other languages and social ties among speakers are more important in favoring grammaticalization than early urbanization and the size of the speaker community. Finally, I also discuss the relationship between literacy in (official) languages and grammaticalization.

2 Demonstrative adjectives

Demonstratives are deictic or anaphoric elements used “to orient the hearer outside of discourse in the surrounding situation [and] to organize the information flow in the ongoing discourse” (Diessel 1999: 2). Classical Latin had a four-term system for demonstrative pronouns and adjectives, made up of proximal hic, medial iste and distal ille, as well as anaphoric is. In this section, I focus on the evolution of the Piedmontese adjectival system and then examine how it compares to developments in the French and Italian systems. My own fieldwork, which partially confirms Lombardi Vallauri’s work (1986), suggests that present-day Piedmontese features a system with three demonstrative adjectives, which emerged via a number of steps that I now summarize. The first attestations of demonstrative adjectives in full-fledged Piedmontese are found in the 14th-century Statuti della Compagnia di San Giorgio a Chieri (Salvioni 1886: 347–350). In the Statuti, the Latin system had already been reduced to two terms: proximal cost and distal col. These derive from the Latin iste and ille, respectively, prefixed by the exclamative eccum < ecce: (ec)cuist(e); (ec)cuill(e). [4]

Old Piedmontese (14th century)

A third form appeared in 17th-century Canzoni (Clivio 1974; see (3a)), namely st, a phonetic reduction of cost and/or of its allophonic variant cas(t). St carried the same meaning as cost, being a proximal demonstrative, while col, with its variant cal, remained the distal adjective: [6]

Piedmontese koiné (17th century)

| I | vöi | fé | savei | sta | vòta | a | tutta | la |

| sbj.cl.1sg | want.prs.1sg | make.inf | know.inf | this | time to | all | the |

| gioventù | | ch-a | s’ | è | fait | na | bella | nòta. |

| youth | that=sbj.cl.3sg | refl | be.prs.3sg | make.pp | a | nice | memo |

‘This time I want to let all the young people know that a nice piece of writing has been produced.’

(Clivio 1974: 34)

| Chi-n | vuol | fé | com | le | polaie |[…] | | lassa |

| who-neg | want.prs.3sg | make.inf | like | the | chickens | let.prs.3sg |

| sté | chste | canaie. |

| stay.inf | these | scoundrels |

‘Whoever does not want to be a sitting duck, should let these scoundrels go.’ (Clivio 1974: 35)

| Stan | un | pòc | e | pöi | gl’ | agreva | | d’ | isté |

| stay.prs.3pl | a | little | and | then | to.them | weigh.prs.3sg | of | stay.inf |

| lì | a | fé | calmsté |

| there | to | make.inf | that job |

‘they remain for a while and, then, it weighs on them to keep on doing that job’(Clivio 1974: 41)

Throughout the 18th century, st became more widespread in the Piedmontese koiné, at the expense of cost. As an adjective, cost was rare in 18th- and 19th-century texts, mainly featuring in plays that mimicked the sermo popularis (4a–b). During the 20th century, another demonstrative form entered Piedmontese grammar: (ë)s (feminine sa, 4c). (Ë)s, derived from the Latin ipse, is quite clearly a first-person demonstrative, although it is used inclusively to indicate all the possible referents in a given context (Lombardi Vallauri 1986: 57). The co-existence of three forms with almost the same proximal meaning probably explains why cost specialized, reinforced by the adverb sì ‘here’, as a demonstrative pronoun. Today, Piedmontese speakers rarely use cost as an adjective (Bonato 2003–2004: 190–217). Col is still the only distal adjective.

Piedmontese koiné

| e | c’ | a | preuvo | mai | pì | a | buté | ‘l | nas |

| and | that | sbj.cl.3pl | try.sbjv.3pl | never | more | to | put.inf | the | nose |

| ant | sta | cà |

| in | this.F | house |

‘and may they never dare to nose in this house again’

(Bersezio 1863, act I, scene 14)

| C’ | a | scusa, | ma | côl | om | a |

| that | sbj.cl.3sg | excuse.sbjv.3sg | but | that | man | sbj.cl.3sg |

| l’ha | fame | monté | la | sënëvra. |

| have.prs.3sg | let.pp.to.me | come.up.inf | the | mustard |

‘Sorry, but that guy really got a rise out of me.’

(Bersezio 1863, act I, scene XIII)

| Lë | studios | che | pr’asar a- | j | rivèissa | ||||||||

| the | scholar | rel | casually | sbj.cl.3sg to.him | happen.ipfv.sbj.3sg | ||||||||

| travers | sa | cernia | ’d | fé | conossensa | con d’ |

| through | this.F | selection | of | make.inf | acquaintance | with indf |

| autor | ch’ | a | lo | antrigèisso | a |

| authors | that | sbj.cl.3sg | him | intrigue.ipfv.sbjv.3sg | sbj.cl.3sg |

| dovrà – | as | capiss – | s’ | a | veul |

| shall.3sg | sbj.cl.imper | understand.3sg | if | sbj.cl.3sg | wants |

| andé | pì | ancreus, | arfesse | a | j’ | originaj. | Faita |

| go.inf | more | deeply | refer.inf.refl | to | the | originals | make.pp.f |

| sa | precisassion […] |

| this.F | clarification |

(Clivio 1972: I)

‘The scholar who, in this selection, happens to come across authors that interest him must, if he wants to go into greater depth, consult the original works. With this clarification in mind […]’

Table 1 sums up the system of demonstrative adjectives in use in contemporary Piedmontese. It is a three-term and two-distance system:

Demonstrative adjectives in contemporary Piedmontese.

| proximal | distal | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| adjective | st | (ë)s | col |

Note: Proximal adjectives may also be reinforced by sì ‘here’ and lì ‘there’; distals may be reinforced by lì and là ‘over there’

According to Lombardi Vallauri (1986), (ë)s may have entered the koiné grammar from peripheral, dialectal varieties. Indeed, (ë)s is attested, in the form is, in non-koiné (i. e., non-Turinese/non-peri-Turinese) texts from the 16th century (e. g., in Alione 1521). In peripheral varieties, the demonstrative adjectival system has since been heavily reduced: several dialects of Piedmontese today feature only one demonstrative adjective, e. g., (ë)s/s(ë) in Cairo (Parry 1991; 2005: 150–156), Biella (Vv.Aa 2000), and Asti (Musso 2003: 68–69), ca in Pinerolo and Avigliana (Calosso 1973: 142–149), with the postposition of deictic adverbs to represent different degrees of (psychological or spatial) distance from the speaker.

Furthermore, from a diachronic point of view, the grammatical changes in this domain seem to have first taken place in the peripheral varieties, and only subsequently in the koiné. While 17th-century Turinese songs contain very few instances of st, the Historia della guerra del Monferrato (1613), written in a Monferrato dialect, already featured the two competing proximal forms cost and st/s, as in (5). In addition, while De’ Conti’s (1798)Gerusalemme Liberata in Monferrino featured a strictly two-distance, two-term system (st vs col), similar to that of the contemporary Turinese variety, the third term cost is still attested in the 19th-century koiné.

Monferrato Piedmontese (17th century)

| E | po | miser | Plinio | studiand | sto | cas, | | Al |

| and | then | mister | Plinius | studying | this | case | sbj.cl-3sg |

| scris | costa | sentenza | in | si | carton | | De |

| write.pfv.3sg | this | sentence | in | on.the | pages | of |

| col | libraz | ch’ | al | fè | in | so | vecchiezza. |

| that | book.pej | that | sbj.cl.3sg | make.pfv.3sg | in | his | old.age |

‘And then Plinius, studying this case, wrote this sentence on the pages of that book that he produced in his old age.’

(Historia: vv. 161–163)

Table 2 summarizes the evolution of the demonstrative adjective system in the Piedmontese koiné with respect to the peripheral varieties: [7]

Demonstrative adjective systems in Piedmontese.

| century | koiné | peripheral |

|---|---|---|

| 14th | cost / col | |

| 16th | (cost) | ist / is / col | |

| 17th | cas | (st) / cal | cost | st / col |

| 18th | (cost) | st / col | st / col |

| 19th | (cost) | st / col | |

| 20th | st | ës / col | ës |

My data are mainly drawn from written texts, which are less accurate in the representation of phonetics and more conservative by nature. It is thus possible that (ë)s became undistinguishable from st via phonetic reduction, and that these two forms have ultimately merged into one demonstrative, in the koiné as well as in the peripheral varieties. If this is indeed what happened, then the contemporary koiné system would also be a two-term system, with one proximal adjective st (and its phonotactic variants) and one distal adjective, col. French has developed a demonstrative adjective system that is very similar to those of the peripheral Piedmontese varieties: it “has reduced the paradigm of the demonstrative determiners maximally, so that it no longer marks differences related to distance” (De Mulder and Lamiroy 2012: 217; Guillot and Carlier 2015). Contemporary French has distinct adjectives and pronouns (ce vs celui/ceux/celle(s)). Note that the only adjectival term in the current French system is ce [sə], now a deictically neutral demonstrative, phonetically identical to the forms attested in Cairo, Biella, and Asti. Just as in Cairo Piedmontese, Biella Piedmontese, and Asti Piedmontese, French ce is reinforced by adverbial suffixes (-ci and -là placed after the noun following the demonstrative), but these “are no longer used systematically” (De Mulder and Lamiroy 2012: 217), so that, for example, -là does not imply that the referent is far away (6a).

Contemporary standard Italian, on the other hand, has a two-term demonstrative system (with both terms used as adjectives and as pronouns), expressing person-related features in the following way: questo, occasionally shortened to (’)sto in informal speech and in allegro forms, i. e., phonetically reduced forms used in rapid speech (see Matthews 2007: s.v.), means ‘close to the speaker’; quello means ‘away from the speaker’ (6b–c). Codesto, a second-person oriented demonstrative that means ‘away from the speaker but close to the hearer’ may still be alive in Tuscan Regional Italian, but has disappeared from everyday communication in standard Italian (Sabatini 1985: 158; Berruto 1987: 78).

Contemporary spoken French

| J’ | aime | ce | vin- | là. |

| I | love.prs.1sg | dem | wine | there |

‘I like this wine.’

(De Mulder and Lamiroy 2012: 217)

Standard Italian

| Mi | piace | questo | vino. |

| to.me | like.prs.3sg | this | wine |

‘I like this wine.’ (near the speaker)

(native competence of the author)

Standard Italian

| Mi | piace | quel | vino. |

| to.me | like.prs.3sg | that | wine |

‘I like that wine.’ (far from the speaker)

(native competence of the author)

In sum, with regard to demonstrative adjectives: Italian has a two-term person-related system (questo/quello). The Piedmontese koiné has a two/three-term person-related system with two distances: (ë)s/st vs. col. As suggested earlier, the first two of these forms might possibly be regarded as allomorphs of a single term. Piedmontese dialects have one neutral demonstrative adjective ((ë)s (+N-sì/lì/là)). [8] French has one neutral adjective (ce (+N-ci/là)). French and Piedmontese dialects thus appear to be more grammaticalized than the Piedmontese koiné and Italian, because they have reduced the paradigm to the maximum extent, which is typical of grammaticalization processes (Lehmann 2002: 118). The Piedmontese koiné appears to be on a par with Italian, although it should be borne in mind that the former is a grammaticalization cycle ahead of the latter. This assessment does not take into account the Italian (’)sto (reduced form of questo, corresponding to the Piedmontese st, reduction of cost), although it is frequently used in everyday communication. In practice, the development of a single dedicated proximal adjective form, i. e., (’)sto, which is different from the pronoun form, i. e., questo, is still in progress in Italian, while it is virtually complete for the Piedmontese koiné (s(t) vs. cost(-sì)). Thus, Italian seems closer to Latin than the Piedmontese koiné, because although both daughter languages have reduced the system to two terms, Italian still does not distinguish between adjectives and pronouns. The RGC with respect to the morphological microsystem of demonstrative adjectives is represented in (7):

| more grammaticalized | less grammaticalized | ||

| |||

| French Piedmontese dialects | Piedmontese koiné | Italian | (Latin) |

3 Negation

In this section, I examine how negative forms have evolved in Piedmontese, and their pace of development in relation to negation in French and Italian (Mosegaard Hansen and Visconti 2012). My analysis is confined to standard negation. [9] In a number of languages and especially in the Romance area, standard negation follows a cyclical pattern known as Jespersen’s cycle:

The original negative adverb is first weakened, then found insufficient and therefore strengthened, generally through some additional word, and this in its turn may be felt as the negative proper and may then in course of time be subject to the same development as the original word. (Jespersen 1917: 4)

The development of the cycle has been studied in detail by Van Der Auwera (2010), and, with a special focus on Piedmontese, by Parry (1996, 2013), who proposed a five-stage model (Parry 2013) that was complemented by a sixth stage argued for in Mosegaard Hansen and Visconti (2012: 455) (see Table 3):

The development of negation.

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Stage 5 | Stage 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| neg1 V | neg1 V neg1 V neg2 | neg1 V neg1 V neg2 V neg3 | neg1 V neg2 V neg3 | V neg3 | neg3 V V neg3 |

The choice of perfective auxiliaries in some Romance varieties.

| Language /Verb class | Definite change of location/state | Indefinite change of location | Continuation of a pre-existing state | Existence of a state | Uncontrolled process | Controlled process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piedmontese koiné | E | E | E | E | E/H | H |

| Italian | E | E | E | E | E/H | H |

| French | E | E/H | H | H | H | H |

| Piedmontese dialects (NE /S Piedmont) | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Coggiola /Niella Piedmontese dialects (NE /S Piedmont) | E | E | E | E | E | E |

In early Piedmontese texts, the descendant of the Latin preverbal non (=[neg1 V]) is the most frequent negator, exhibiting conditioned allophony (non vs no). Nonetheless, some instances of discontinuous negation (=[neg1 V neg2]) already appeared in the Sermons Subalpins, while, alongside [neg1 V] and [neg1 V neg 2] sentences, a single occurrence of post-verbal negation (=[V neg3]) is attested in a song from Carmagnola as early as the 14th century (8b).

Old Piedmontese (12th/13th century)

| Lo | premer, | qui | est | ric, | no | li | vol |

| The | first | who | be.prs.3sg | rich | neg | him | want.prs.3sg |

| nient | aier. | ||||||

| neg | help.inf |

‘The first, who is rich, does not want to help him (in any way).’

(Sermons subalpins, VII, 51–52; Parry’s 2013 translation)

Old Piedmontese (14th century)

| queli | chi | son | nen | vegnù | | no | poeno |

| those | rel=sbj.cl.3pl | be.prs.3pl | neg | come.pp | neg | can.prs.3pl |

| pa | dir | ansì |

| counterexp.neg say.inf | so |

‘those who did not come cannot say the same thing’

(Clivio 1970: 55, Laudi di Carmagnola III, 2)

Stages 2 and 3 in the development of negation (Table 3) were reached in the 16th century, as attested in the work of Alione (9a), while 17th-century Turinese songs and plays already exhibited Stage 4, with n … nent/pa (9b) as the most usual form of negation and the postverbal nen (9c) rising to more than 25 % of all negations in Tana’s ‘L Cont Piolet (a play written during the 17th century but not published until 1784). [10] Analysis of Bersezio’s (1863)Le miserie ’d Monssù Travet (see 9d) shows that Stage 5, [V neg3], had been reached in the Piedmontese koiné before the 19th century.

Asti Piedmontese (16th century)

| Basta, | che | te | n’ | an | sarai | nent! |

| enough | that | you | neg | of.us | be.fut.2sg | neg |

‘Enough, you will not be one of us!’

(Alione 1521: 430)

Piedmontese koiné (17th century)

| a-n | sà | pa | scasi | ont | viresse |

| sbj.cl.3sg-neg | know.prs.3sg | neg | almost | where | turn.inf.refl |

‘one almost does not know where to turn’

(Clivio 1974: 50)

Piedmontese koiné (17th century)

| E | già | ch’ | voi | ‘m | volì | nen | sposè |

| and | since | that | you.pl.hon | me.acc | want.prs.2pl | neg | marry.inf |

‘and since you do not want to marry me’

(Tana 1690: 78)

Piedmontese koiné

| Se | soa | fomna | a | ‘ndeissa | nen | tant |

| if | your.hon | wife | sbj.cl.3sg | go.ipfv.sbjv.3sg | neg | so.much |

| a la mòda, | a | l’aveissa | nen | tanta | ambission, |

| à la mode | sbj.cl.3sg | have.ipfv.sbjv.3sg | neg | so.much | ambition |

| a | spendeissa | nen | tant |

| sbj.cl.3sg | spend.ipfv.sbjv.3sg | neg | so.much |

‘if only your wife did not dress in such a fashionable way, did not have so much ambition, did not spend so much money’

(Bersezio 1863, act I scene II)

Bordering varieties, such as Cairese (i. e., Cairo Piedmontese, 10a–b) and Roccavignale Piedmontese (10c), still display some degree of variation today in that they can exhibit, along with [V neg3], preverbal n’ and discontinuous n’ … nen (see Parry 2014: 221–222; Duberti and Regis 2014: 104–105). Other conservative varieties spoken along the political regional borders, however, consistently use the [V neg3] form (see 10d for an example of so-called Kje spoken in Roccaforte Mondovì). The data suggest that the dialects linguistically oriented towards Ligurian have tended to maintain a [neg1 V] or [neg 1 V neg2] strategy, because of the contact with Ligurian, a [neg1 V] language, much more so than the dialects linguistically oriented towards the koiné.

Cairo Piedmontese

| a | n’ | heu | nèn | visc-tle |

| sbj.cl.1sg | neg | have.prs.1sg | neg | seen.him |

‘I did not see him’

(Parry 2005: 256)

Roccavignale Piedmontese

| sa | valvula | li ‘n zima, | nurmal, | gn’ | ha | gnènt |

| this | valve | on.top | normal | neg | has | neg |

‘the valve on top, the normal one, it’s not there’

(Miola 2013: 216, adapted to conform to standard orthography)

Kje/Conservative Roccaforte Piedmontese

| si | t’ | has | gnent | o biet, it |

| if | sbj.cl.2sg | have.prs.2sg | neg | the ticket sbj.cl.2sg |

| pass | gnent | |||||

| pass.prs.2sg | neg |

‘if you do not have the ticket, you cannot pass’

(Miola 2013: 216, adapted to conform to standard orthography)

The diachronic development of French negation has been investigated, among others, by Ashby (1981), Mosegaard Hansen (2009), and Mosegaard Hansen and Visconti (2012): “Colloquial spoken French is currently very firmly Stage 4” (Mosegaard Hansen and Visconti 2012: 455). The [neg1 V neg2] construction ne … pas had grammaticalized as the standard negation by the end of the 17th century (Mosegaard Hansen 2009: 229), but French is now moving towards Stage 5, given that pas is in the course of grammaticalizing as the only negator. [11]

Standard French

| Jean | ne | mange | pas | de | poisson. |

| J. | neg | eat.prs.3sg | neg | part | fish |

‘Jean does not eat fish.’

(Bernini and Ramat 1996: 17)

Colloquial French

| C’ | est | dommage | qu’on | soit | pas | plusieurs. |

| dem | is | pity | that sbj.cl.imper | be.sbjv.3sg | neg | several.pl |

‘Too bad there aren’t many of us.’

(Van Compernolle 2009: 47)

Standard Italian, on the other hand, is still at Stage 1 in Table 3, as the Latin preverbal non is still the standard negation in non-emphatic sentences (12a). Northwestern Italian dialects (i. e., socio-geographical and situational varieties of Italian) are developing [neg1 V neg2] and [V neg3] strategies (12b–c), possibly under the influence of regional languages spoken in that part of Italy, such as Lombard or Emilian:

Standard Italian

| Non | riesco | a | trovare | un | buon | esempio. |

| neg | succeed.prs.1sg | to | find.inf | a | good | example |

‘I can’t find a good example.’

(native competence of the author)

Colloquial (Northern) Italian

| Non | dico | mica… |

| neg | say.prs.1sg | neg |

‘I do not say [mica]…’

Colloquial (youth) Italian

| Ho | capito | un | cazzo. |

| have.prs.1sg | understand.pp | a | prick (=neg) |

‘I didn’t understand.’

(native competence of the author)

In light of the data discussed in this section, the position of the three languages with respect to standard negation may be summarized as follows [12]:

| more grammaticalized | less grammaticalized |

| |

| Piedmontese koiné | (colloquial) French (Northern-)Italian |

| Piedmontese dialects | (Latin) |

Piedmontese is ahead of all other languages in that it has been consistently at Stage 5 since the 19th century, while French is currently still at Stage 4. Standard French, in turn, is ahead of Italian, whose standard variety has not left the Latin stage yet. Nevertheless, northwestern spoken Italian appears to be moving towards Stage 2 or 3. [13]

While it is impossible to predict whether Piedmontese will display Stage 6 constructions with finite verbs in the future, contemporary varieties of Piedmontese already negate infinitives by means of a preverbal nen (14a). The same holds for French infinitives (15a). In relation to gerundives, the Piedmontese edition of Wikipedia shows that both pre-verbal and post-verbal negation may be used, although the latter strategy is strongly preferred (14b–c). French is still a [neg1 V neg2] language as far as the negation of the gerundives is concerned (15b).

Piedmontese koiné

| Për | la | meison | costa-sì | a | l’é | stàita | la |

| For | the | car.company | this.here | sbj.cl.3sg | be.prs.3sg | been | the |

| prima | vitura | ëd | Segment | B | con | carosserìa | zincà | per |

| first | car | of | Segment | B | with | bodywork | zinc-coated | for |

| nen | fela | dësvërnisè. |

| neg | make.inf.it | lose.the.paint |

‘For the car company this was the first B-Segment car with a zinc-coated body to prevent loss of paint.’

| Pensand | nen | a | la | possibilità | ’d | na | cariera | an | costa |

| thinking | neg | to | the | possibility | of | a | career | in | this |

| dissiplin-a, | ant | ël | 1910 | as | anscriv | a | la |

| discipline | in | the | 1910 | sbj.cl.3sg.refl | enrol.prs.3sg | to | the |

| facoltà | d’ | angegnerìa. |

| faculty | of | engineering |

‘Without thinking about the possibility of an academic career, in 1910 he enrolled at the Faculty of Engineering.’

| Nen | avend | d’ | arzultà, | a | scriv | na | litra | an |

| neg | having | indf | outcomes | sbj.cl.3sg | write.prs.3sg | a | letter | in |

| sij | prinsipi | dla | mecànica. | |||||||||

| on.the | principles | of | mechanics |

‘Having failed to obtain any results, he wrote a letter on the principles of mechanics.’

Standard French

| Goyard | a | feint | de | ne | pas | le | voir. |

| Goyard | have.pres.3sg | pretend.pp | of | neg | neg | him | see.inf |

‘Goyard pretended not to see him.’

(Simenon 1931: 94, quoted from Martineau 1994: 56)

| en | n’ | ayant | pas | la | possibilité |

| in | neg | have.ger | neg | the | possibility |

These data show that Piedmontese is also ahead of French as far as the negation of non-finite verb forms is concerned.

4 Perfective auxiliaries

Perfective auxiliaries, i. e., the light verbs with which present perfect and other compound tenses are formed, go back in Romance to the Latin verbs esse ‘to be’ and habere ‘to have’, which gradually lost their referential meaning. As is well known, Romance languages usually display split intransitivity: while active-voice transitive verbs consistently use have as a perfective auxiliary, intransitives are divided into two subclasses: unergatives, which preferably use have, and unaccusatives, which preferably use be. [14] Nonetheless, recent developments in the study of this topic suggest that the selection of have or be is in fact a gradual phenomenon, with core unaccusatives and core unergatives displaying less variation than other verbs of the same class (Sorace 2000). Furthermore, the choice of have or be for an individual verb may change over time. “This is particularly evident in the Romance languages, which have been undergoing a diachronic change leading to the progressive replacement of be by have” (Sorace 2000: 860). Sorace (2000), Cennamo (2001), Cennamo and Sorace (2007), and Cennamo (2008) showed that cross-linguistically the spread of one perfective auxiliary at the expense of the other follows a lexical-semantic path. Accordingly, verbs can be divided into subclasses (e. g., verbs indicating a change of state/location, verbs indicating a state, verbs indicating motional/non-motional processes, etc.), and have has been shown to spread over time from the “core-unergative” verb class (i. e., controlled non-motional processes) to “less core-unergative”, or “peripheral”, verb classes (i. e., motional processes, change of state/location, etc.). “Change proceeds from the center towards the periphery in the case of changes involving the constitution of a category with a radial structure [like split intransitivity, EM], but follows a reverse path (from the periphery towards the center) in the case of the (partial) cancellation of a category with a radial structure” (Cennamo 2008: 137; see also; Lazzeroni 2005: 18).

The contemporary Piedmontese koiné is a split-intransitivity language, its perfective auxiliaries being avej ‘to have’ and esse ‘to be’ (see Burzio 1986; Villata 1997: 168–170):

Piedmontese koiné

| Ti | it | ses | andà | a | Turin. |

| you | sbj.cl.2sg | be.prs.2sg | go.pp | to | Turin |

‘You went/have gone to Turin.’

(author’s fieldwork)

| Ti | it | l’has | travajà | tant. |

| you | sbj.cl.2sg | have.prs.2sg | work.pp | a.lot |

‘You (have) worked a lot.’

(author’s fieldwork)

| Ti | it | l’has | mangià | la | pasta |

| you | sbj.cl.2sg | have.prs.2sg | eaten | the | pasta |

‘You ate/have eaten pasta.’

(author’s fieldwork)

| Ier | a | l’é/l’ha | piuvù. |

| yesterday | sbj.cl.3sg | be/have.prs.3sg | rain.pp |

‘Yesterday it rained.’

(author’s fieldwork)

Nonetheless, in varieties such as Biella Piedmontese (the dialect spoken in the city of Biella, in north-eastern Piedmont), as well as in Southern Piedmontese dialects, the aforementioned replacement of esse by avej is ongoing, and indeed, in the areas around Biella and Cuneo, change has already proceeded to the extent that split intransitivity has disappeared. In Vallanzenghese and Cigliese, for instance, avej is the only remaining auxiliary for all verbs (Cerrone and Miola 2011: 196–198).

In contemporary French, only about a dozen verbs use être ‘to be’ as a perfective auxiliary (Rowlett 2007: 40). These verbs belong to two verbal subclasses indicating a definite/indefinite change of location (e. g., arriver ‘to arrive’) or a definite/indefinite change of state (devenir ‘to become’; Sorace 2000: 863–867). All other French verbs use avoir ‘to have’.

Standard Italian, on the other hand, uses avere ‘to have’ with transitive and intransitive verbs indicating uncontrolled (squillare ‘to ring’) and controlled processes (lavorare ‘to work’), although in the case of uncontrolled processes essere ‘to be’ may be used instead of avere without any variation in meaning (17a–b).

Standard Italian

| Il | telefono ha/è | squillato. |

| the | telephone have/be.prs.3sg | ring.pp |

‘The telephone rang.’

(Sorace 2000: 877)

| Abbiamo/**siamo | lavorato/**i | finora. |

| have/**be.prs.1pl | work.pp | until.now |

‘We have worked until now.’

(native competence of the author)

Interestingly enough, in the small Piedmontese towns of Coggiola (see 18) and Niella Tanaro (Nicola Duberti, p.c.), only be is used to form the perfective compound tenses (even with transitive verbs, see 18):

Coggiola Piedmontese

| L’ | é | biughe | dui | binei. |

| sbj.cl.3sg | be.prs.3sg | have.pp | two | twins |

‘(She) gave birth to twins.’

(ALI’s questionnaire)

| I | son | cantà | na | cansoni. |

| sbj.cl.1sg | be.prs.1sg | sing.pp | a | song |

‘I have sung a song.’

(Cerrone and Miola 2011: 199)

The choice of perfective auxiliaries in the languages and varieties discussed so far is schematized in Table 4. [15]

The development of auxiliary selection is in fact a counterexample to the RGC hypothesis (Lindschouw 2010: 186), because “Spanish reduced its auxiliary alternation, thus showing more paradigmaticity (Lehmann 2002), and hence a higher degree of grammaticalization […] than French and Italian” (De Mulder and Lamiroy 2012: 201), whereas in other domains, French and Italian are consistently more grammaticalized than Spanish. It is still not clear why Spanish and other Ibero-Romance languages have grammaticalized faster in this domain (but see Rosemeyer 2014), but they are beyond the scope of the current paper. However, the same degree of grammaticalization as in Spanish is displayed by the peripheral Piedmontese dialects Vallenzenghese and Cigliese, which are thus ahead of French, the Piedmontese koiné, and Italian. With regards to the Coggiola and Niella Piedmontese dialects, the pace of grammaticalization of the perfective auxiliaries may even have been faster than that of the other Piedmontese dialects. Following Cennamo (2008), we might speculate that all verb classes first adopted have (as in the Biella Piedmontese dialects), with be subsequently once more superseding have. In other words, the Coggiola and Niella varieties may have completed a double auxiliary cycle in the same timespan that it has taken the other varieties to complete only one.

The diagram in (19) represents the degree of grammaticalization of perfective auxiliaries in French, Italian, and Piedmontese:

| more grammaticalized | less grammaticalized | |

| ||

| Piedmontese dialects | French | Italian |

Piedmontese koiné

5 Plural indefinite articles

Indefinite and partitive articles are a key topic that has been widely discussed in recent linguistic research on the Romance languages. My discussion is informed by previous work by Herslund (2012), Carlier and Lamiroy (2013), Luraghi (forthcoming), and, with a special focus on Piedmontese, Bonato (2004). The indefinite “article”, which in Latin did not exist as such, developed from the Latin preposition de ‘of, from’ plus the definite “article” ille, -a, -um. In all three languages at issue here, this development began during the 12th/13th centuries. Originally, de(+ille) had a strictly partitive meaning, as in (20).

Old Piedmontese (12th/13th century)

| So compaignun | no | bevrà | d’ | aiva clara. |

| his comrade | neg | drink.fut.3sg | of (=part) | water clear |

‘His comrade will not drink clear water.’

(Sermons subalpins: VIII, 156; see Bonato 2004: 180)

Old French (12th century)

| Del | vin | volentiers | bevaient. |

| of (=part).the | wine | gladly | drink.ipfv.3pl |

‘They gladly drank (some) of the wine.’

(Chrétien de Troyes, Erec, 3178; quoted from Carlier and Lamiroy 2013)

Old Italian (13th century)

| Che | del | ben | non | vi | sia. |

| that | of (=part).the | good | neg | there | be.sbjv.3sg |

‘That there is not some good.’

(Ubertino del Bianco d’Arezzo; quoted from Luraghi forthcoming)

Whereas there is no evidence for the use of de as an indefinite article in the Sermons Subalpins (12th/13th century), it appears in the poems of Alione (1521) with both partitive and indeterminate meanings, although the latter function could also be fulfilled by Ø. At that time, however, articulated forms were more frequent than unarticulated ones, that is, forms derived from the Latin de+ille were used more than the bare de.

In the course of the following centuries, the use of indefinite articles and partitives became more frequent, although they continued to alternate with Ø. With regard to article function, both articulated and unarticulated forms were used. The latter, however, came to be increasingly preferred, so that by the mid-18th/early-19th century the unarticulated form had been almost fully grammaticalized and had become obligatory for both the indefinite article and the partitive functions (see Bonato 2004, whose examples are quoted in 21).

Asti Piedmontese (16th century)

| E | c’ | avran | el | man? | |Ø | Begli | guant | de està, |

| and | what | have.fut.3pl | the | hands | nice | gloves | in summer |

| e | d’invern | del | mittaine, | o Ø | moffole. |

| and | in winter | indf | muffs | or | mittens |

‘And what will the hands wear? Nice gloves during summer and in winter muffs or mittens.’

(Alione 1521: 40)

Piedmontese koiné (18th century)

| Purtröp | a | s’ | treuvo | di | caluniator, | e |

| Unfortunately | sbj.cl.3sg | imper | find.prs.3pl | indf | slanderers | and |

| dj’ | invidios, | i quai | per | fè | perde | l’ | afession | d’ |

| indf | enviouses | rel | for | make.inf | lose.inf | the | love | of |

| un | Pare | vers | un | fieul | a | s’ | invento |

| a | father | towards | a | son | sbj.cl.3sg | imper | make.up.prs.3pl |

| d’ | còse | tute | fause. |

| indf | things | all | false |

‘Unfortunately one can find slanderers and envious people who, in order to make a father lose his love for his son, make up all sorts of false stories.’

(Pipino 1783: 100)

Piedmontese koiné (19th century)

| Sté | tant | ch’ | podré | lontan | da | ‘d | lite |

| Stay.imp.2pl | much | that | can.fut.2pl | far | from | indf | fights |

| e | ‘d | gare. | |||||||||

| and | indf | challenges |

‘Stay away from fights and challenges as much as you can.’

(Casalis, Fàule Esopian-e, in Brero 1981: II, 52)

Whereas in spoken Turinese and peri-Turinese varieties (i. e., the varieties upon which the koiné is modeled) the unarticulated form dë/ëd is nowadays obligatory (see 22a, and all the spontaneous interactions registered by Bonato 2004: 185), in contemporary (peripheral) Piedmontese dialects, both articulated and unarticulated forms are still in use (and also alternated with Ø), as shown in examples (22b–c):

Piedmontese koiné

| Gioan | a | les | ëd/**Ø | poesie | ant | soa | stansia. |

| G. | sbj.cl.3sg | read.prs.3sg | indf | poems | in | his | room |

‘Gioan reads poems in his room.’

(author’s fieldwork)

Cairo Piedmontese

| im | portavo | Ø | grissini | faj | in |

| sbj.cl.3pl=to.me | bring.ipfv.3pl | breadsticks | make.pp | in | |

| campagna. | |||||

| countryside |

‘They used to bring me breadsticks made in the countryside.’

(Parry 2005: 142)

Cairo Piedmontese

| J’ | ero | za | dij | bej | sòdi. |

| sbj.cl.3pl | be.ipfv.3pl | already | indf.the | beautiful.pl | money-pl |

‘There was already a nice bit of money.’

(Parry 2005: 143)

This shows that some Piedmontese syntactic structures “contemporaneamente riflettono stadi più arcaici del dialetto stesso, all’italiano più affini di quelle odierne. È quindi possibile cogliere non solo l’impulso all’italianizzazione, ma anche la tensione tra koiné e varietà periferiche” [simultaneously reflect more archaic stages of the regional language that were more similar to Italian than the contemporary stage. It is thus possible to capture not only the drift towards Italianization, but also the variation between the koiné and peripheral varieties] (Bonato 2004: 190; my translation).

French has followed a pattern very similar to Piedmontese’s. After 13th-century “exploratory expressions” (Harris and Campbell 1995), de+ille gradually developed into a full-fledged article, mainly with direct objects at first (15th and 16th century), but becoming increasingly obligatory from 1700 onward in all syntactic positions, including subjects (Carlier and Lamiroy 2013; see 23a).

As for Italian, the de+ille+NP construction (initially used with mass nouns and direct objects) has always appeared in alternation with Ø (see 23b). Today, its use is still not obligatory, but is sensitive to diatopy, with Northern Italian varieties displaying it more frequently than Central and Southern ones (Tekavčić 1980: 118; Luraghi forthcoming). In other words, the regional languages of Italy and (Regional) Italians (in this case Northern Italians) appear to mutually influence one another with respect to the use of partitive/indefinite articles. The fact that Northern speakers of Italian seem more prone to use the partitive than Southern speakers (Carlier and Lamiroy 2013) might result from their different regional linguistic adstrata (i. e., regional and minority languages spoken throughout Italy, as well as French, German, and/or other neighboring languages).

French

| Jean | lit | des/**Ø | poèmes | dans | sa | chambre. |

| J. | read-prs-3sg | indf | poems | in | his | room |

‘Jean reads poems in his room.’

(based on Herslund 2012: 345)

Standard Italian

| Gianni | legge | delle/Ø | poesie | nella | sua | stanza. |

| G. | read-prs-3sg | indf/Øindf | poems | in.the | his | room |

‘Gianni reads poems in his room.’

(native competence of the author)

With respect to the development of the plural indefinite article, the different degrees of grammaticalization displayed by the languages under investigation are schematically represented in (24):

| more grammaticalized | less grammaticalied | |

| ||

| Piedmontese koiné | French | (North-)Italian |

| Piedmontese dialects | ||

A remark is in order here to explain why I have positioned the Piedmontese koiné ahead of French. While French and Italian developed their indefinite article from the articulated Latin preposition de, the competition between the articulated and unarticulated forms in Piedmontese came to an end in favor of the latter during the 19th century. Given that phonetic reduction is a key feature of grammaticalization (Lehmann 2002), Piedmontese is arguably more grammaticalized than the other languages examined here.

6 Conclusion: How do language changes spread throughout a linguistic community?

For the majority of the morphosyntactic domains discussed above, Piedmontese, in its dialect varieties or in its koiné or in both, is on a par with, or even slightly ahead of, French on the RGC, while French is consistently ahead of Italian. It is beyond the scope of this paper to address the question as to why some grammatical domains seem to constitute counterexamples to the usual grammaticalization cline for Romance languages. Take, for example, perfective auxiliation, where Spanish and Portuguese are ahead of French on the RGC, but are constantly behind it in other domains. Similarly, the Piedmontese koiné is at the same stage as Italian with respect to perfective auxiliaries, but is consistently ahead in all other domains. A possible explanation might be that perfective auxiliation is not regarded by (naïve) speakers as a morpho-syntactic feature, but rather as a lexical feature. For bilingual speakers, lexical features are more salient, which is why the difference between the two languages is easily identified, and leveled out or completely eliminated, possibly on account of the prestige of the more standardized language, or of the so-called “roof language”, in the terms of Kloss (1967). This may have happened with Piedmontese, given that it was, and is, spoken alongside Italian, which is generally perceived as more prestigious by Piedmontese speakers. [16] In any case, the higher degree of grammaticalization of Piedmontese in the Romance area seems to represent, at least with respect to French and Italian, a strong pattern. [17] These findings may help explain why some languages appear to be more grammaticalized than others within the same genealogical family. First, they complement De Mulder and Lamiroy’s (2012: 219–221) view about the role of language-external factors in the grammaticalization processes. As argued by De Mulder and Lamiroy, early urbanization and the size of the speaker community may play a role in favoring grammaticalization. However, neither of these factors can account for the fact that regional languages, such as Piedmontese (and even its local dialects), which by definition are spoken by a smaller population than national languages, are grammaticalizing at least as fast as the most grammaticalized language investigated by De Mulder and Lamiroy, namely French, and consistently faster than Italian. What exactly is it, then, that speeds up grammaticalization in Romance languages?

I suggest a tentative answer to this question on the basis of three parameters. Further studies, taking into account other regional languages of Europe, are needed to confirm, refine or change my speculative conclusions. Given the sometimes extremely different sociolinguistic and socio-historical status of each minor or regional language present in Italy, it is beyond the scope of this paper to investigate the position of other regional languages on the RGC. However, at least as far as the regional languages of Northern Italy are concerned, the data available appears to display a very similar pattern to the Piedmontese data presented here, for example, in relation to demonstrative adjectives, negation (Vai 1996), and other grammar domains (Cerruti 2008; Fedriani and Miola 2014; Loporcaro et al. 2014).

The three factors that I propose may be responsible for speeding up grammaticalization are (i) the strength of social ties among speakers, (ii) the amount of contact with other languages, and (iii) the absence of a fixed linguistic norm (enforced by schools).

6.1 The pace of grammaticalization and small communities

Although in larger communities, made up of individuals who are related to each other by weak ties rather than strong ones, languages may change at a fast pace, in small communities “the speed of language change may be increased when speakers of these communities enter into contact with individuals with whom they have weak ties” (De Mulder and Lamiroy 2012: 220; see also Sinnemäki 2009). In addition, very small language communities may display more rapid language change if the gap between innovators and early adopters, i. e., groups of speakers that further disseminate innovations into the speech community by virtue of their central social role in it (Milroy and Milroy 1985), is narrowed by the fact that innovators are also early adopters. It is also arguable that small, peripheral communities are more prone to having contact – for economic or geographical reasons – with the surrounding speech communities. This leads us to consider the role of contact.

6.2 Language contact

By most accounts, language contact speeds up the pace of language change (Milroy and Milroy 1985). This is also what I argue here. All the Piedmontese-speaking communities that I have described as peripheral are located on the borders of the region and are therefore in contact with at least one other language besides Italian. Thus, prior to the 20th century, natives of Cairo and Biella, who were diglossic and spoke their local variety of Piedmontese alongside the Piedmontese koiné, and possibly also alongside Italian when it came to “high” domains, were in contact with Ligurian and Lombard, respectively. Even the inhabitants of Turin, whose linguistic repertoire did not include a local Piedmontese variety different from the koiné, were exposed to French, which was one of the languages, together with Italian, spoken by the upper classes and the court up to at least the mid-19th century.

This is a typical example of “situation[s] where contact between people leads to the establishment of many weak ties” which might be responsible for the acceleration of language change (Milroy and Milroy 1985: 380). Thus, the presence of diglossia or multilingualism due to contact with other languages speeds up grammaticalization and language change in general. Sicilian and English, for example, have undergone more changes than Sardinian and Icelandic respectively (Milroy and Milroy 1985) because they have been much more subject to language contact. As I have shown in this paper, this is also the case for peripheral Piedmontese varieties, as compared with the koiné.

6.3 The role of literacy and standardization

One might wonder, then, why Italian did not evolve as fast as the regional languages spoken on Italian territory, and why French has been faster to grammaticalize, even though it was spoken diglossically alongside regional languages until the last century (Lodge 1993: 193–194), a situation somewhat similar to Italian.

A key point here is that Italian was spoken as a native language by almost no one until the mid-20th century (De Mauro 1991: 43). It had been the written language of the entire Italian peninsula since 1500 (Testa 2014), but, although used by intellectuals and writers, Italian was never consistently taught to (and above all, never learnt by) large portions of the population until the end of the 19th century. In some Italian regions, the rate of illiteracy was still over 25 % in the mid-20th century (De Mauro 1991: 95). Until the last century, Italian was only used in “high” domains by cultured people, while the majority of Italians learned it as an L2 and scarcely, if ever, spoke it. Thus, Italian has remained extremely conservative with respect to Latin because of this peculiar sociolinguistic situation: “standard” norms were enforced and were rarely transgressed, simply because nobody actually spoke Italian, apart from highly cultured adult individuals, who mainly used it in written/formal contexts, and whose language is – as is well known – highly conservative in any case. Only when other strata of the population, such as youngsters, started to learn Italian and it was, so to speak, vernacularized, could the pace of grammaticalization begin to speed up. Furthermore, the standardization and scripturalization of a language usually has the effect of slowing down its rhythm of grammaticalization (“language reformation often aim[s] at halting, regulating or redirecting […] grammaticalization”, Laitinen 2004: 247). Italian was codified in the mid-16th century by Pietro Bembo, based on the prose of three 14th-century writers (Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, and Giovanni Boccaccio). For this reason “in Italia […] il processo di formazione della lingua nazionale coincise con la formazione di una lingua letteraria, basata sul prestigio del modello fiorentino, per secoli utilizzata prevalentemente come lingua scritta e come strumento di comunicazione tendenzialmente alta” [in Italy the process of forming a national language coincided with the formation of a literary language, based on the prestige of the Florentine model, which, for centuries, had mainly been used as a written language and as a means of cultured communication] (Banfi 2014: 26; my translation). Indeed, few changes were made in prescriptive grammars until the mid-20th century.

France, on the other hand, evolved towards a new sociolinguistic situation during the 16th century, when, “for a sizeable proportion of the population, Parisian French functioned as a colloquial L[ow] language in addition to its H[igh] role” (Lodge 1993: 150). When it comes to standardization, then, French is positioned at least some two hundred years after Italian: while the first Italian codification may be said to be based on written texts from 1300–1375 (when Boccaccio, the last of the Tre Corone, died), for French, the elaboration of function began during the 16th century and was not fully codified until the 18th century (Lodge 1993: 149). Moreover, French was standardized based on a spoken dialect, that of Paris, rather than on the language used in literary works, as Italian was. For French, these conditions resulted in less restrained grammaticalization processes.

As regards Piedmontese, it remained a spoken-only Romance variety until recent years: the absence of conservative factors, such as a codified and enforced set of norms (see Parry 1996: 233) may have played a major role in increasing its grammaticalization pace, yielding the following summarizing outline of the RGC for the three languages studied here.

| more grammaticalized | less | grammaticalized | |

| |||

| Piedmontese | French | Italian | (Latin) |

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments on an earlier version of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies. All websites cited in the work were last accessed 24 January 2017.

Abbreviations

- 1/2/3

first/second/third

- acc

accusative

- counterexp

counterexpectative

- dem

demonstrative

- f

feminine

- fut

future

- ger

gerundive

- hon

honorific

- imp

imperative

- imper

impersonal

- indf

indefinite article

- inf

infinitive

- ipfv

imperfective

- neg

negative morpheme

- part

partitive

- pej

pejorative

- pfv

perfective

- pl

plural

- pp

past participle

- prs

present

- refl

reflexive pronoun

- rel

relative pronoun

- sbj.cl

subject clitic

- sbjv

subjunctive

References

ALI = Atlante Linguistico Italiano. 1995. Data stored at the University of Turin.Suche in Google Scholar

Alione, Giovan Giorgio. 1521. L’opera piacevole. Bologna: Libreria antiquaria Palmaverde (reprint 1953).Suche in Google Scholar

Ashby, William J. 1981. The loss of the negative particle ne in French: A syntactic change in progress. Language 57(3). 674–687.10.2307/414345Suche in Google Scholar

Banfi, Emanuele. 2014. Lingue d’Italia fuori d’Italia. Bologna: il Mulino.Suche in Google Scholar

Bernini, Giuliano & Paolo Ramat. 1996. Negative sentences in the languages of Europe: A typological approach. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Berruto, Gaetano. 1987. Sociolinguistica dell’italiano contemporaneo. Firenze: La Nuova Italia.Suche in Google Scholar

Berruto, Gaetano. 1990. Note tipologiche di un non tipologo sul dialetto piemontese. In Gaetano Berruto & Alberto A. Sobrero (eds.), Studi di sociolinguistica e dialettologia offerti a Corrado Grassi, 3–24. Galatina: Congedo.Suche in Google Scholar

Berruto, Gaetano. 1991. Fremdarbeiteritalienisch: Fenomeni di pidginizzazione nella Svizzera tedesca. Rivista di Linguistica 3. 333–367.Suche in Google Scholar

Berruto, Gaetano. 2010. Identifying dimentions of linguistic variation in a language space. In Peter Auer & Jürgen Erich Schmidt (eds.), Language and space: An international handbook of linguistic variation: Theories and methods, 226–240. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Bersezio, Vittorio. 1863. Le miserie ’d Monssù Travet. Available online at www.liberliber.it (accessed 26 April 2016).Suche in Google Scholar

Bonato, Massimo. 2003–2004. Tratti variabili nella sintassi del piamontese parlato contemporaneo. Turin: University of Turin MA thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Bonato, Massimo. 2004. Partitivo e articolo indeterminativo plurale nel piemontese parlato contemporaneo. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia 28. 175–196.Suche in Google Scholar

Brero, Camillo. 1981. Storia della letteratura piemontese, 2 Vols. Torino: Piemonte in Bancarella.Suche in Google Scholar

Burzio, Luigi. 1986. Italian syntax. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.10.1007/978-94-009-4522-7Suche in Google Scholar

Calosso, Silvia. 1973. Osservazioni sui microsistemi morfologici di alcune parlate galloitaliche occidentali. Archivio Glottologico Italiano 58(2). 142–154.Suche in Google Scholar

Carlier, Anne, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.). 2012a. The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2).10.1515/flin.2012.010Suche in Google Scholar

Carlier, Anne, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy. 2012b. Introduction: The pace of grammaticalization in a typological perspective. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 287–301.Suche in Google Scholar

Carlier, Anne & Béatrice Lamiroy. 2013. The grammaticalization of the prepositional partitive in Romance. In Silvia Luraghi & Tuomas Huumo (eds.), Partitive cases and related categories, 477–522. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110346060.477Suche in Google Scholar

Cennamo, Michela. 2001. L’Inaccusatività in alcune varietà campane: Teorie e dati a confronto. In Federico Albano Leoni, Rosanna Sornicola, Eleonora Stenta Krosbakken & Carolina Stromboli (eds.), Dati empirici e teorie linguistiche: Atti del XXXIII Congresso Internazionale della Società di Linguistica Italiana, Napoli, 28–30 ottobre 1999, 427–453. Rome: Bulzoni.Suche in Google Scholar

Cennamo, Michela. 2008. The rise and development of analytic perfects in Italo-Romance. In Thortallur Eythorsson (ed.), Grammatical change and linguistic theory: The Rosendal Papers, 115–142. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.113.05cenSuche in Google Scholar

Cennamo, Michela & Antonella Sorace. 2007. Auxiliary selection and split intransitivity in Paduan. In Raul Aranovich (ed.), Split auxiliary systems: A cross-linguistic perspective, 65–99. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.69.05cenSuche in Google Scholar

Cerrone, Pietro C. & Emanuele Miola. 2011. La selezione degli ausiliari in un’area del Piemonte nordorientale. Atti del Sodalizio Glottologico Milanese 6 n.s. 196–207.Suche in Google Scholar

Cerruti, Massimo. 2008. Condizioni e indizi di coniugazione oggettiva: I dialetti italiani settentrionali tra le lingue romanze. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia 32. 13–38.Suche in Google Scholar

Clivio, Gianrenzo P. 1970. Brevi prose in volgare piemontese del Quattrocento: I testi carmagnolesi. In Raymond J. Cormier & Urban T. Holmes Jr. (eds.), Essays in honor of Louis Francis Solano, 54–64. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Clivio, Gianrenzo P. 1972. Achit. In Censin Pich (ed.), Sernia ’d pròse piemontèise dla fin dl’Eutsent, i. Torino: Centro Studi Piemontesi.Suche in Google Scholar

Clivio, Gianrenzo P. 1974. Il dialetto di Torino nel Seicento. L’Italia dialettale 37. 18–128.Suche in Google Scholar

Clivio, Gianrenzo P. 2002. Il Piemonte. In Manlio Cortelazzo, Carla Marcato, Nicola De Blasi & Gianrenzo P. Clivio (eds.), I dialetti italiani: Storia struttura uso, 151–195. Torino: Utet.Suche in Google Scholar

Coluzzi, Paolo. 2008. Language planning for Italian regional languages (“dialects”). Language Problems & Language Planning 32(3). 215–236.10.1075/lplp.32.3.02colSuche in Google Scholar

Coluzzi, Paolo. 2009. Endangered minority and regional languages (‘dialects’) in Italy. Modern Italy 14(1). 39–54.10.1080/13532940802278546Suche in Google Scholar

Cravens, Thomas D. 2014. Italia linguistica and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Forum Italicum 48(2). 202–218.10.1177/0014585814529221Suche in Google Scholar

Danesi, Marcel. 1976. La lingua dei Sermoni Subalpini. Torino: Centro Studi Piemontesi.Suche in Google Scholar

De Mauro, Tullio. 1991. Storia linguistica dell’Italia unita, 4th edn. Bari-Roma: Laterza.Suche in Google Scholar

De Mulder, Walter & Béatrice Lamiroy. 2012. Gradualness of grammaticalization in Romance: The position of French, Spanish and Italian. In Kristin Davidse, Tine Breban, Lieselotte Brems & Tanja Mortelmans (eds.), Grammaticalization and language change, 199–226. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.130.08mulSuche in Google Scholar

De’ Conti, Giuseppe. 1798. La Gerusalemme liberata in monferrino, Cant I. Almanacco Piemontese 1972. 128–146.Suche in Google Scholar

Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.42Suche in Google Scholar

Duberti, Nicola & Riccardo Regis. 2014. Tra Alta Langa e Alpi monregalesi: Percorsi, limiti e prospettive di varietà marginali. In Giannino Balbis & Fiorenzo Toso (eds.), L’alta Val Bormida linguistica, 85–116. Genova: Claudio Zaccagnino Editore.Suche in Google Scholar

Fagard, Benjamin & Alexandru Mardale. 2012. The pace of grammaticalization and the evolution of prepositional systems: Data from Romance. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 303–340.10.1515/flin.2012.011Suche in Google Scholar

Fedriani, Chiara & Emanuele Miola. 2014. Percorsi di soggettificazione di manu ad manu(m) in alcuni dialetti del nord Italia. L’Italia Dialettale 75. 103–120.Suche in Google Scholar

Gasca Queirazza, Giuliano. 1996. Un’ipotesi sulla localizzazione dei Sermoni subalpini. Studi piemontesi 25. 105–110.Suche in Google Scholar

Giacalone Ramat, Anna & Caterina Mauri. 2012. Gradualness and pace in grammaticalization: The case of adversative connectives. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 483–512.Suche in Google Scholar

Giacalone Ramat, Anna & Andrea Sansò. 2014. Venire (‘come’) as a passive auxiliary in Italian. In Maud Devos & Jenneke Van Der Wal (eds.), ‘COME’ and ‘GO’ off the beaten Grammaticalization path, 21–44. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110335989.21Suche in Google Scholar

Giolitto, Marco. 2010. La communauté piémonitaise d’Argentine. München: Martin Meidenbauer Verlagsbuchhandlung.Suche in Google Scholar

Guillot, Céline & Anne Carlier. 2015. Evolution des démonstratifs du latin au français: Passage d’un système ternaire à un système binaire. In Anne Carlier, Michèle Goyens & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), Le français en diachronie: Nouveaux objets et methods, 337–371. Bern: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Harris, Alice C. & Lyle Campbell. 1995. Historical syntax in cross-linguistic perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511620553Suche in Google Scholar

Herslund, Michael. 2012. Grammaticalisation and the internal logic of indefinite article. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 341–358.Suche in Google Scholar

Historia = Anon. C. 1613. Historia della guerra del Monferrato. In Camillo Brero, Renzo Gandolfo & Giuseppe Pacotto (eds.) 1967. La letteratura in piemontese dalle origini al Risorgimento, 202–208. Torino: Casanova.Suche in Google Scholar

Iacobini, Claudio. 2012. Grammaticalization and innovation in the encoding of motion event. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 359–386.Suche in Google Scholar

Jespersen, Otto. 1917. Negation in English and other languages. Copenhagen: Høst & Søn.Suche in Google Scholar

Kloss, Heinz. 1967. ‘Abstand languages’ and ‘Ausbau languages’. Anthropological Linguistics 9. 29–71.Suche in Google Scholar

Lahousse, Karen & Beatrice Lamiroy. 2012. Word order in French, Spanish and Italian: A grammaticalization account. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 387–416.Suche in Google Scholar

Laitinen, Lea. 2004. Grammaticalization and standardization. In Olga Fischer, Muriel Norde & Harry Perridon (eds.), Up and down the cline: The nature of grammaticalization, 247–262. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.59.13laiSuche in Google Scholar

Lamiroy, Béatrice. 1999. Auxiliares, langues romanes et grammaticalisation. Langages 135. 63–75.Suche in Google Scholar

Lamiroy, Béatrice & Water De Mulder. 2011. Degrees of grammaticalization across languages. In Bernd Heine & Heiko Narrog (eds.), Handbook of grammaticalization, 302–318. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199586783.013.0024Suche in Google Scholar

Lazzeroni, Romano. 2005. Mutamento e apprendimento. In Lidia Costamagna & Stefania Giannini (eds.), Acquisizione e mutamento di categorie linguistiche. Atti del XXVIII Convegno della Società Italiana di Glottologia, Perugia, 23–25 ottobre 2003, 13–24. Roma: Il Calamo.Suche in Google Scholar

Lehmann, Christian. 2002. Thoughts on grammaticalization. 2nd rev. edn. Available online at http://www.db-thueringen.de/servlets/DerivateServlet/Derivate-2058/ASSidUE09.pdf (accessed 26 April 2016).Suche in Google Scholar

Lindschouw, Jan. 2010. Grammaticalization and language comparison in the Romance mood system. In Eva-Maria Remberger & Margin G. Becker (eds.), Modality and mood in Romance: Modal interpretation, mood selection, and mood alternation, 181–207. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Lodge, R. Anthony. 1993. French: From dialect to standard. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203319994Suche in Google Scholar

Lombardi Vallauri, Edoardo. 1986. Uno studio sistematico sui termini dimostrativi piemontesi. Florence: University of Florence MA thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Loporcaro, Michele. 2007. On triple auxiliation in Romance. Linguistics 45(1). 173–222.10.1515/LING.2007.005Suche in Google Scholar

Loporcaro, Michele, Vincenzo Faraoni & Francesco Gardani. 2014. The third gender of Old Italian. Diachronica 31(1). 1–22.10.1075/dia.31.1.01garSuche in Google Scholar

Luraghi, Silvia. Forthcoming. Partitives and differential marking of core arguments: A cross-linguistic survey.Suche in Google Scholar

Marazzini, Claudio. 2012. Storia linguistica di Torino. Roma: Carocci.Suche in Google Scholar

Martineau, France. 1994. Movement of negative adverbs in French infinitival clauses. Journal of French Language Studies 4. 55–73.10.1017/S0959269500001976Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, Peter H. 2007. The concise Oxford dictionary of linguistics, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Milroy, James & Leslie Milroy. 1985. Linguistic change, social network and speaker innovation. Journal of Linguistics 21. 339–384.10.1017/S0022226700010306Suche in Google Scholar

Miola, Emanuele. 2013. Innovazione e conservazione in un dialetto di crocevia. Milano: Franco Angeli.Suche in Google Scholar

Mosegaard Hansen, Maj-Britt. 2009. The grammaticalization of negative reinforcers in Old and Middle French: A discourse-functional approach. In Maj-Britt Mosegaard Hansen & Jacqueline Visconti (eds.), Current trends in diachronic semantics and pragmatics, 227–252. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.10.1163/9789004253216_013Suche in Google Scholar

Mosegaard Hansen, Maj-Britt & Jacqueline Visconti. 2012. The evolution of negation in French and Italian: Similarities and differences. In Anne Carlier, Walter De Mulder & Béatrice Lamiroy (eds.), The pace of grammaticalization in Romance. [Special issue]. Folia Linguistica 46(2). 453–482.Suche in Google Scholar

Musso, Giancarlo. 2003. Gramática astesan-a. Asti: Gioventura Piemontèisa.Suche in Google Scholar

Pacotto, Giuseppe. 1930. La grafia piemontese: Norme per la pronuncia e altri scritti esplicativi. In Giuseppe Pacotto & Anrea Viglongo (eds.), Tutte le poesie piemontesi di Edoardo I. Calvo, 11–15. Torino: Selp.Suche in Google Scholar

Parry, Mair. 1991. Le système démonstratif du cairese. In Dieter Kremer (ed.), Actes du XVIIIe Congrès International de Linguistique et de Philologie Romanes, Université de Treves (Trier), 1986, 626–631. Tubingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Parry, Mair. 1996. La negazione italo-romanza: Variazione tipologica e variazione strutturale. In Paola Benincà, Guglielmo Cinque, Tullio De Mauro & Nigel Vincent (eds.), Italiano e dialetti nel tempo, saggi di grammatica per Giulio C. Lepschy, 225–257. Roma: Bulzoni.Suche in Google Scholar

Parry, Mair. 1997. Piedmont. In Martin Maiden & Mair Parry (eds.), The dialects of Italy, 237–244. London: Routedge.Suche in Google Scholar

Parry, Mair. 2005. Parluma ’d Còiri: Sociolinguistica e grammatica del dialetto di Cairo Montenotte. Savona: Società Savonese di Storia Patria.Suche in Google Scholar

Parry, Mair. 2013. Negation in the history of Italo-Romance. In David Willis, Christopher Lucas & Anne Breitbarth (eds.), The history of negation in the languages of Europe and the Mediterranean, Vol. II: Case Studies, 77–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199602537.003.0003Suche in Google Scholar

Parry, Mair. 2014. Language tutorial: The dialect of Cairo Montenotte. L’Italia Dialettale 75. 201–228.Suche in Google Scholar

Pipino, Maurizio. 1783. Gramatica Piemontese. Torino: Reale stamparia.Suche in Google Scholar

Regis, Riccardo. 2012a. Su pianificazione, standardizzazione, polinomia: Due esempi. Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie 128(1). 88–133.10.1515/zrp-2012-0005Suche in Google Scholar

Regis, Riccardo. 2012b. Koinè dialettale, dialetto di koinè, processi di koinizzazione. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia 35. 7–36.Suche in Google Scholar

Rosemeyer, Malte. 2014. Auxiliary selection in Spanish: Gradience, gradualness and conservatism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.155Suche in Google Scholar

Rowlett, Paul. 2007. The syntax of French. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511618642Suche in Google Scholar

Sabatini, Francesco. 1985. ‘L’italiano dell’uso medio’: Una realtà tra le varietà linguistiche italiane. In Günter Holtus & Edgar Radtke (eds.), Gesprochenes Italienisch in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 154–184. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Salvioni, Carlo. 1886. Antichi testi dialettali cheresi. In Vv.Aa., In memoria di Napoleone Caix e Ugo Angelo Canello: Miscellanea di Filologia e Linguistica, 345–355. Firenze: Le Monnier.Suche in Google Scholar

Sankoff, Gillian & Diane Vincent. 1977. L’emploi productif du ne dans le français parlé à Montréal. Le Français Moderne 45. 243–256.Suche in Google Scholar

Sermons Subalpins = Clivio, Gianrenzo P. & Marcel Danesi (eds.). 1974. Concordanza linguistica dei ‘Sermoni Subalpini’, xiii–xxxvi. Torino: Centro studi piemontesi.Suche in Google Scholar

Simenon, Georges. 1931. Le chien jaune. Paris: Presses Pocket.Suche in Google Scholar

Sinnemäki, Kaius. 2009. Complexity in core argument marking and population size. In Goeffrey Sampson, David Gil & Peter Trudgill (eds.), Language complexity as an evolving variable, 126–140. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorace, Antonella. 2000. Gradients in auxiliary selection with intransitive verbs. Language 76. 859–890.10.2307/417202Suche in Google Scholar

Tana, Carlo Giambattista. 1690. ’L Cont Piolet. Torino: Einaudi (reprint 1966).Suche in Google Scholar

Tekavčić, Pavao. 1980. Grammatica storica dell’italiano. Bologna: il Mulino.Suche in Google Scholar

Telmon, Tullio. 1988. Aree linguistiche II: Piemonte. In Günter Holtus, Michael Metzeltin & Christian Schmitt (eds.), Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik, Vol. IV, 469–485. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.10.1515/9783110966107.469Suche in Google Scholar

Telmon, Tullio. 2001. Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta. Roma-Bari: Laterza.Suche in Google Scholar

Testa, Enrico. 2014. L’italiano nascosto: Una storia linguistica e culturale. Torino: Einaudi.Suche in Google Scholar

Tressel, Yvonne. 2004. Sermoni subalpini: Studi lessicali con un’introduzione alle particolarità grafiche, fonetiche, morfologiche e geolinguistiche. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.Suche in Google Scholar

Trudgill, Peter. 1994. Dialects. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203305935Suche in Google Scholar

Trudgill, Peter. 2002. Sociolinguistic variation and change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Vai, Massimo. 1996. Per una storia della negazione in milanese in comparazione con altre varietà altoitaliane. Acme 49(1). 57–98.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Compernolle, Rémi A. 2009. Emphatic ne in informal spoken French and implications for foreign language pedagogy. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 19(1). 47–65.10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00213.xSuche in Google Scholar

Van Der Auwera, Johan. 2010. On the diachrony of negation. In Laurence R. Horn (ed.), The expression of negation, 73–101. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110219302.73Suche in Google Scholar

Villata, Bruno. 1996. I Sermoni subalpini e la lingua d’oe. Montréal: Lòsna & Tron.Suche in Google Scholar

Villata, Bruno. 1997. La lingua piemontese: Fonologia Morfologia Sintassi Formazione delle parole. Montréal: Lòsna & Tron.Suche in Google Scholar

Vv.Aa. 2000. Piemontèis ëd Biela. Abecedare, gramàtica e sintassi, literatura bielèisa, glossare. Biella: Ieri e oggi.Suche in Google Scholar

Wright, Sue. 2006. Regional or minority languages on the WWW. Journal of Language and Politics 5(2). 189–216.10.1075/jlp.5.2.04wriSuche in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Predicative possession in the languages of the Circum-Baltic area

- Against a unitary clause-final focus: Evidence from Russian and Polish

- Evaluative stancetaking in courtroom opening statements

- The position of Piedmontese on the Romance grammaticalization cline

- Variation and phonological change: The case of yeísmo in Spanish

- Alternating argument constructions of Dutch psychological verbs: A theory-driven corpus investigation

- Global features of online communication in local Flemish: Social and medium-related determinants

- Book Reviews

- Dixon, R.M.W.: Are some languages better than others?

- Duanmu, San.: A theory of phonological features.

- Jaszczolt, Kasia M.: Meaning in linguistic interaction: Semantics, metasemantics, philosophy of language.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Predicative possession in the languages of the Circum-Baltic area

- Against a unitary clause-final focus: Evidence from Russian and Polish