Abstract

The paper examines the causality between the German current account and financial account. It contrasts with past research which assumes the current account and financial account to be jointly determined by a saving-investment imbalance. Our analysis decomposes the current account into exports and imports (real resource flows) and the financial account into domestic capital outflows and foreign capital inflows (gross capital flows). Evidence from the Toda-Yamamoto causality test shows that for Germany from Q1.1980 to Q2.2023, the causality runs from the financial account to the current account. It is not real resource flows but gross capital flows which exert significant impacts on the German real exchange rate. The finding implies that over the long run, strong German capital outflows and weak foreign capital inflows contributed to weak wage growth and stagnant investment in Germany, sustaining the persistent German current account surpluses. A reduction of the German current account surpluses requires a policy mix of fiscal expansion and monetary tightening which would expand the absorption of German and foreign capital in the German economy.

1 Introduction

After a decade of current account deficits following unification in 1990, Germany has been running current account surpluses for over two decades.[1] Even in the coronavirus crisis which exerted substantial negative impacts on international trade (Hayakawa and Mukunoki 2021), the German current account recorded a surplus of 4.2 % of GDP in 2022.

Past debates on the German current account surpluses focused on the real side of the economy. The German current account surplus was seen as the outcome of a high saving rate driven by demographic factors (Felbermayr, Fuest, and Wollmershäuser 2017; Obstfeld and Rogoff 2005), the low investment rate (Berger and Wolff 2017; Micossi, D’Onofrio, and Peirce 2018), the restrictive wage policy (Gros and Busse 2013; Manger and Sattler 2020; Zemanek, Belke, and Schnabl 2010) or “… the strong competitiveness of the German economy and the international demand for quality products from Germany” as argued by the German government (Wall Street Journal 2013).

What has been left unexplored is the focus on the financial side of the economy. From a balance of payments perspective, the German current account surplus is the mirror image of net capital outflows. Past research on developing countries revealed the causality running from foreign capital inflows to current account deficits (Faroque and Veloce 1990; Higgins and Klitgaard 1998; Mastroyiannis 2012; Yan 2005). Yet little or no research examined how German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows affect the German current account surplus.

Using the Toda-Yamamoto causality procedure, the paper shows that for Germany from Q1.1980 to Q2.2023, the causality runs from the financial account to the current account. Gross capital flows, i.e. German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows, granger-cause changes in real resource flows, i.e. exports and imports, and not vice versa. Evidence also shows that it is not changes in real resource flows but changes in gross capital flows which are linked to the real depreciation of the German exchange rate observed since the late 1990s.

Seen through the financial lens, the German current account surpluses persisted because strong German capital outflows and weak foreign capital inflows contributed to weak wage growth and stagnant investment in Germany. From a policy perspective, a correction of the German current account surpluses requires fiscal expansion and monetary tightening. The policy mix would discourage German capital outflows and encourage foreign capital inflows, which leads to the real appreciation of the German exchange rate.

2 The Relationship Between the Current Account and Financial Account

From an accounting perspective, most international financial transactions only appear in the financial account without any impact on the current account. Yet from an economic perspective, those (gross) international financial transactions affect the real economy and the current account through the cross-border transfer of purchasing power.

2.1 Recording of Balance-of-Payments Transactions

Every international transaction between residents and non-residents is entered twice with equal values in the balance of payments, once as a credit with plus sign and once as a debit with minus sign (International Monetary Fund 2009). The double bookkeeping accounting ensures that the current account always equals the financial account.[2]

First, the German net exports of goods in 2022 recorded a surplus of 111.9 billion euros, which enters the current account as a credit (plus sign). The resulting receipt of 111.9 billion euros reflects the increase of Germany’s financial claims on the rest of the world, which enters the financial account as a debit (minus sign) of 111.9 billion euros.

The German exports, for instance, could have been financed by German trade credits to foreign importers. It would give rise to a debit (minus sign) of 111.9 billion euros in the financial account as a trade credit represents Germany’s financial claims on the rest of the world. The corresponding credit (plus sign) of the trade credits also enters the financial account. The deposits created by the German trade credits increase Germany’s financial liabilities against the rest of the world. The debit and credit entries are thus netted out to zero in the financial account.

The German exports could also have been financed by the German purchases of foreign bonds issued by foreign importers. A debit entry (minus sign) in the portfolio investment of the financial account reflects an increase of Germany’s financial claims on the rest of the world. The corresponding credit (plus sign) in other investment of the financial account reflects an increase of Germany’s deposit liabilities (financial liabilities against the rest of the world). Both debit and credit entries are cancelled out in the financial account.

Second, a transaction between Germany and other euro-area member states is settled in Target2, the euro-area interbank payment system.[3] The German Bundesbank’s Target2 claims on the Eurosystem show that the interbank transfer of deposits from banks participating in Target2 via the Bundesbank to banks participating in Target2 via other national central banks is greater than the other way around (Deutsche Bundesbank 2007, 2011). The double-entry bookkeeping records an increase in the Target2 claims as a debit entry (minus sign) under the other investment balance of the financial account.

The corresponding credit entry (plus sign) may appear on the current account if the counterpart is a real transaction, e.g. exports of goods. If the counterpart is a financial transaction, e.g. the sales of foreign securities by residents in Germany or the foreign purchases of German securities, the corresponding credit entry appears on the financial account. In the case of financial transactions, both debit and credit entries are cancelled out in the financial account.

These examples show that the accounting identity between the current account and financial account ensured by double-entry bookkeeping per se does not reveal any causal relationship. From an accounting perspective, a German current account surplus would not develop unless exports exceed imports, regardless of how much German capital flows out of the economy, because the credit and debit entries of the financial transactions are both made and offset on the financial account. Yet from an economic perspective, an excess of German capital outflows over foreign capital inflows can be seen as transfer of purchasing power to abroad with impacts on the real economy. Given the growth of global financial markets since the 1970s (Bayoumi and Macdonald 1995; Borio 2014), international capital flows should therefore be viewed as a current account determinant.

2.2 Standard Approaches to the Current Account Determination

Using the national income identity, Andersen (1990) showed four current account approaches:

where EX stands for total receipts for exports in the current account, IM for total payments for imports in the current account, S for total gross saving, I for total gross investment, Y for total output, D for total domestic demand and F for net capital flows.

The first approach is the trade approach. The current account (EX − IM) is traditionally seen as the outcome of relative income and prices including the real exchange rate. A prominent work related to the trade approach is the elasticity approach by Marshall (1923), Lerner (1936), and Harberger (1950). The second approach is the saving-investment approach which views the current account as the outcome of changes in domestic saving and investment (S − I). The intertemporal approach developed by Obstfeld and Rogoff (1995) made substantial contributions to the saving-investment approach. Also, the saving-investment approach gained wide popularity through the savings glut hypothesis advanced by Bernanke (2005).

The third approach is Alexander’s (1952) absorption approach which views the current account as the outcome of differences in total output and total domestic demand (Y − D). The fourth approach is the capital flow approach. The current account is seen as the outcome of changes in net capital flows (F). Net capital flows refer to the difference between domestic capital outflows and foreign capital inflows. The capital flow approach is perhaps the most unexplored approach in current account literature in comparison to the trade, saving-investment and absorption approaches which sparked a large literature in international economics.

As illustrated in equation (1), the common modelling of international capital flows is net capital flows. Schularick (2016) argues that the current account and net capital flows are the parallel consequence of saving and investment. A similar reasoning is echoed in Krugman, Obstfeld, and Melitz (2015): “[i]f national saving falls short of domestic investment, the difference equals the current account deficit. […] the country is borrowing abroad” (p. 678). In a similar vein, the intertemporal approach treats net capital outflows as the outcome of intertemporal decisions of saving and investment across countries (Gourinchas and Rey 2014).[4] What is common in literature is the use of the national income identity which allows international capital flows to be presented as a byproduct of other macroeconomic variables. The issue on how international capital flows affect exports and imports, domestic savings and investment or domestic expenditure and income appears to be rarely addressed.

A strand of research holds a critical view of the prevailing approaches in which the analysis of international capital flows goes no further than the realm of the national income identity. Shin (2012: 156) argues that the standard current account analysis treats international capital flows as “the residual to the outcome from the real side of the economy” (See also Johnson 1977). By the same token, Kim and Kim (2011: 498) argue that “adherents to conventional macroeconomic theory dispense entirely with the causal approach and rely instead on the accounting identity approach. Because CA [current account] deficits are identical to KA (financial account) surpluses in this framework, it is impossible, apart from errors and omissions, to observe any causal relationship between the CA and the KA”.

2.3 Gross Capital Flow Approach

Gross capital flows consist of domestic capital outflows and foreign capital inflows. Golub (1990), Turner (1991), and Johnson (2009) point out that it is not net capital flows but gross capital flows which offer a full picture of international capital flows. Similarly, Borio and Disyatat (2015) argue that the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle of international capital flows (1980) is a puzzle of net capital flows but not a puzzle of gross capital flows.[5] While research attention to gross capital flows has been growing in international finance literature, there is little research which examines the current account imbalances from a gross capital flow perspective.

To fill the gap the paper modifies Andersen’s (1990) capital flow approach. The current account consists of total receipts for exports and total payments for imports. Likewise, net capital flows consist of domestic capital outflows and foreign capital inflows. Based on equation (1), the gross capital flow approach can therefore be formulated as follows:

where KX denotes domestic capital outflows, KM denotes foreign capital inflows and all the other variables remain the same as in equation (1). The sum of EX, IM, KX and KM is always equal to zero since “[a]s with any other account, the total receipts of a country are bound be equal to the total payments of that country, if one includes all the receipts and all the payments of the country in the account” (Meade 1970: 3–4; see also Beretta and Cencini 2020).

The paper follows the common definition in finance literature. Domestic capital outflows are the net of domestic purchases and domestic sales of foreign assets. Foreign capital inflows are the net of foreign purchases and sales of domestic assets. Forbes and Warnock (2012) label the net of domestic purchases and sales of foreign assets as “gross outflows” and the net of foreign purchases and sales of domestic assets as “gross inflows”. Broner et al. (2013) call them “capital outflows by domestic agents” and “capital inflows by foreign agents”. Hwang et al. (2017) use “asset flows” for domestic capital outflows and “liability flows” for foreign capital inflows.

While there is no clear terminology, all the terms refer to the net of domestic purchases and sales of foreign assets and the net of foreign purchases and sales of domestic assets as gross capital flows.[6] The main reason for looking at gross capital flows is not only to highlight the different investment behaviors by residents and nonresidents (Hwang et al. 2017). It also reveals the different impacts of domestic and foreign capital flows on the real economy (Forbes and Warnock 2012). The analysis on gross capital flows contributes to the understanding about the role of international capital flows in the development of financial crises and current account imbalances (Avdjiev, McCauley, and Shin 2016; Borio and Disyatat 2015; Vercelli 2019; Wolf 2014).

3 Empirical Analysis

Using the Toda-Yamamoto procedure, evidence for Germany suggests that over the long run, the causality runs from the financial account to the current account via the real depreciation of the German currency.

3.1 Data Description and Estimation Procedure

The analysis on the long-term causality between the German current account and financial account contains five variables. EX (exports) and IM (imports) stand for the total receipts and total payments in the German current account.[7] KX (domestic capital outflows) and KM (foreign capital inflows) stand for the net of domestic purchases and sales of foreign assets as well as the net of foreign purchases and sales of domestic assets in the German financial account.[8] REER is the German real effective exchange rate index, adjusted by unit labor costs.

All the variables excluding the real exchange rate index are expressed in percent of GDP. The data sample starts from Q1.1980 to Q2.2023. The data for EX, IM, KX and KM is retrieved from the balance of payments statistics compiled by the Bundesbank in line with the International Monetary Fund’s (2009) Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual. The REER is retrieved from the OECD Main Economic Indicators.

The paper follows the Toda and Yamamoto (1995) procedure, one of the most applied procedures in causality analysis (Hacker and Hatemi-J 2006), to test for the long-term causality between the German current account and financial account in a multivariate framework. The advantage of the Toda-Yamamoto approach over the Granger approach is the use of a modified Wald (MWALD) test statistic. The Granger causality analysis may suffer from a spurious inference if variables under study are integrated with different orders or cointegrated (Granger and Newbold 1974; Phillips 1986). By contrast, the Toda-Yamamoto modified Wald test allows to examine the causality, regardless of whether or not variables are integrated with different orders or cointegrated (Adriana 2014; Yan 2005; Zapata and Rambaldi 1997). Moreeover, the Toda-Yamamoto procedure allows to use the levels of the data (Giles 2011). It implies that the distortions and loss of the long-run information contained in the levels of the data due to the differencing of the data (Lütkepohl 1982) do not arise.

The paper takes the following steps: (1) Determine the order of maximum integration of the data (dmax) using unit root tests. (2) Specify a multivariate vector autoregression (VAR) model in levels. (3) Determine the optimal lag length (k) of the VAR model using information criteria. (4) Increase the optimal lag length (k) until the autocorrelation in the residuals is removed using LM statistics to ensure that the VAR model is well-specified. (5) Examine a cointegrated relationship between the variables in the VAR model using the Johansen cointegration test to ensure the existence of a long-term relationship (Johansen and Juselius 1990). (6) Estimate an augmented (k + d max)th order VAR model in levels to ensure that the Wald statistic follows an asymptotic χ 2-distribution. (7) Apply a standard Wald statistic, which follows an asymptotic χ 2-distribution with the degrees of freedom (the number of eliminated lagged variables), to the first k VAR coefficient matrix to investigate the Granger causal relationship.

3.2 Model Description and Results of Unit Root and Cointegration Tests

In line with past research on a Granger causality analysis in a multivariate framework, the real exchange rate is incorporated as a key linking variable for the relationship between the German current account and financial account (see Calvo, Leiderman, and Reinhart 1993; Kim and Kim 2011; Yan 2005).[9] Our analysis is innovative in that the current account is differentiated between the total receipts (EX) and the total payments (IM), and the financial account is differentiated between domestic capital outflows (KX) and foreign capital inflows (KM). To identify the causality directions in a diagnostically well-specified and parsimonious way, the following four augmented (k + d max)th order VAR models are estimated:

Model 1:

Causality Between German Capital Outflows and Exports

The objective of model 1 is to identity the existence of the effect of German capital outflows on German exports, and the other way around, conditional on the real exchange rate.

Model 2:

Causality Between German Capital Outflows and Imports

The objective of model 2 is to identity the existence of the effect of German capital outflows on German imports, and the other way around, conditional on the real exchange rate.

Model 3:

Causality Between Foreign Capital Inflows in Germany and German Exports

The objective of model 3 is to identity the existence of the effect of foreign capital inflows on German exports, and the other way around, conditional on the real exchange rate.

Model 4:

Causality Between Foreign Capital Inflows in Germany and German Imports

The objective of model 4 is to identity the existence of the effect of foreign capital inflows on German imports, and the other way around, conditional on the real exchange rate.

To determine the order of maximum integration (d max) for the Toda-Yamamoto causality test, the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KSPP) unit root tests are conducted. Table 1 shows that all the variables are non-stationary in levels and stationary in first differences at the 5 % level. The results indicate that all the variables are integrated of order one, or I(1), implying the maximum order of integration of 1 (d max = 1).

Results of ADF and KSPP unit root tests.

| Variables | ADF | KPSS (Trend) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | First difference | Levels | First difference | |

| KX | −1.18 [8] | −7.63*** [8] | 0.18** [4] | 0.01 [4] |

| KM | −1.72 [8] | −8.07*** [7] | 0.31*** [4] | 0.01 [4] |

| EX | 1.98 [10] | −5.11*** [9] | 0.40*** [4] | 0.06 [4] |

| IM | 1.43 [10] | −6.11*** [6] | 0.28*** [4] | 0.03 [4] |

| REER | 0.25 [7] | −6.45*** [6] | 0.35*** [4] | 0.06 [4] |

-

Source: Own calculation. Notes: The number in the parenthesis for ADF test denotes the lag length based on the Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC). The number in the parenthesis for KPSS test denotes the truncation lag parameter. The null hypothesis of ADF test is that the time series is nonstationary, whereas the null hypothesis of KPSS test is that the time series is stationary. ***, **, and * represent the 1, 5, 10 % significance levels, respectively.

A cointegrated relationship implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the variables under study (Johansen and Juselius 1990). Rambaldi and Doran (1996) argue that if there is a cointegrated relationship in a system, the Toda-Yamamoto MWALD test is suited for a Granger causality analysis. Since the results of the unit root tests in Table 1 suggest that all the variables under study are integrated, the paper conducts the Johansen cointegration test for all four models. The results in Table 2 suggests that at 1 % significance level, there is one long-run relationship in all four models, which supports the use of the Toda-Yamamoto procedure.

Results of Johansen cointegration tests (Trace).

| Model 1: KX, EX, REER [7] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null hypothesis | Trace statistic | 5 % critical value | 1 % critical value |

| r = 0* | 49.27 | 34.91 | 41.07 |

| r = 1 | 18.79 | 19.96 | 24.60 |

|

|

|||

| Model 2: KX, IM, REER [7] | |||

|

|

|||

| r = 0* | 49.83 | 34.91 | 41.07 |

| r = 1 | 18.39 | 19.96 | 24.60 |

|

|

|||

| Model 3: KM, EX, REER [7] | |||

|

|

|||

| r = 0* | 42.10 | 34.91 | 41.07 |

| r = 1 | 19.37 | 19.96 | 24.60 |

|

|

|||

| Model 4: KM, IM, REER [7] | |||

|

|

|||

| r = 0* | 42.01 | 34.91 | 41.07 |

| r = 1 | 17.29 | 19.96 | 24.60 |

-

Source: Own calculation. Notes: the number in the parenthesis shows lag length chosen based on the AIC criteria, which is seven for all models; r shows the number of cointegrating vectors; The null hypothesis (no cointegration) is rejected if trace statistic is greater than its 1 % critical value. * denotes the rejection of the null hypothesis at the 0.01 level.

3.3 Results of Toda-Yamamoto Test for Multivariate Granger Causality

Table 3 shows the estimation results for the four models. Evidence from the Tada-Yamamoto causality procedure suggests that conditional on the German real exchange rate (REER), the direction of causality runs from German capital outflows (KX) and foreign capital inflows (KM) in the financial account to the total receipts (EX) and the total payments (IM) in the current account, and not the other way around. This finding is consistent with Yan (2005) which shows the causality running from the financial account to the current account for Germany.

Results of Toda-Yamamoto causality test.

| Model 1: KX, EX, REER | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null hypothesis | Length of delay | MWALD test | Prob. |

| KX does not Granger-cause EX | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 27.44149 | 0.0006*** |

| KX does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 18.76122 | 0.0162** |

| EX does not Granger-cause KX | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 12.60536 | 0.1262 |

| EX does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 9.281924 | 0.3191 |

| REER does not Granger-cause KX | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 8.339086 | 0.4011 |

| REER does not Granger-cause EX | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 14.30690 | 0.0741* |

|

|

|||

| Model 2: KX, IM, REER | |||

|

|

|||

| KX does not Granger-cause IM | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 41.70559 | 0.0000*** |

| KX does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 19.95508 | 0.0297** |

| IM does not Granger-cause KX | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 15.42195 | 0.1174 |

| IM does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 12.12977 | 0.2765 |

| REER does not Granger-cause KX | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 8.392535 | 0.5906 |

| REER does not Granger-cause IM | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 19.82374 | 0.0310** |

|

|

|||

| Model 3: KM, EX, REER | |||

|

|

|||

| KM does not Granger-cause EX | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 22.74371 | 0.0037*** |

| KM does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 18.71061 | 0.0165** |

| EX does not Granger-cause KM | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 12.51571 | 0.1296 |

| EX does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 11.06077 | 0.1983 |

| REER does not Granger-cause KM | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 9.804834 | 0.2790 |

| REER does not Granger-cause EX | (k = 8) + (d max = 1) = 9 | 12.94748 | 0.1137 |

|

|

|||

| Model 4: KM, IM, REER | |||

|

|

|||

| KM does not Granger-cause IM | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 30.47315 | 0.0007*** |

| KM does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 18.51951 | 0.0468** |

| IM does not Granger-cause KM | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 13.89413 | 0.1779 |

| IM does not Granger-cause REER | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 12.16242 | 0.2743 |

| REER does not Granger-cause KM | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 8.072462 | 0.6218 |

| REER does not Granger-cause IM | (k = 10) + (d max = 1) = 11 | 17.23168 | 0.0694* |

-

Source: Own calculation. Notes: ***, **, and * represent the 1, 5, 10 % significance levels. The choice of optimal lag length k is based on the Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and the log-likelihood ratio (LR) test with diagnostic tests.

Another finding is that both KX and KM granger-cause REER at 5 % significance level, and not the other way around. By contrast, neither EX nor IM granger-causes REER, while REER granger-causes EX at 10 % significance level (see model 1) and IM at 5 or 10 % significance level (see model 2 and 4). These results imply that the effect of gross capital flows (KX and KM) in the financial account on real resource flows (EX and IM) in the current account might percolate through the real exchange rate.

Figure 1 shows that all the inverse roots of autoregressive polynomial lie inside the unit circle. The results of the residual analysis imply that all the four augmented VAR models satisfy the stability conditions and ensure the robustness of our results (Dinh 2020; Shahzad et al. 2017).

Inverse roots of AR characteristic polynomial. Source: Own calculation. Notes: No root lies outside the unit circle.

4 The German Current Account Surplus from a Gross Capital Flow Perspective

The evidence implies that given the real exchange rate, gross capital flows in the financial account convey information for predicting the variation of real resource flows in the current account (see Diebold 2004). This section examines the Granger causality running from the German financial account to the current account from a macroeconomic perspective.

4.1 Bonanzas of Foreign Capital Inflows and Current Account Deficits in the 1990s

There is scarce research on the German current account from a gross capital flow perspective. The German reparation debate in the late 1920s drew attention to the effect of gross capital flows on the German current account. Keynes (1929) called gross capital flows ‘liquids’ which cannot alter such a ‘solid mass’ as the current account.[10] By contrast, Ohlin (1929) argued that gross capital flows transfer the purchasing power from one country to another, leading to the emergence of current account imbalances.[11] The Keynes-Ohlin debate led Machlup (1964) and Kindleberger (1976) to examine gross capital flows as a driver of current account imbalances.[12]

In the following decades, research attention to gross capital flows as a determinant of the German current account has faded away. The German current account deficits in the 1990s (see Figure 2) are usually seen as the reflection of expanded domestic demand due to the unification in 1990. Sinn (2002), and Felbermayr, Fuest, and Wollmershäuser (2017) argued that the drastic increase of domestic investment to rebuild the new eastern territory of reunified Germany surpassed domestic saving, turning the German current account into deficits.[13] Similarly, Schnabl and Zemanek (2012) argue that the excess of domestic investment over saving led to the repatriation of net foreign assets cumulated by West Germany prior to unification.

The German current account and financial account (net capital flows). Source: Deutsche Bundesbank. Notes: Positive values mean current account surpluses and net capital inflows. Negative values mean current account deficits and net capital outflows.

According to the common view, Germany imported more real resources and capital as domestic investment exceeded saving. The current account and financial account are, in other words, implicitly assumed to be jointly determined by the saving-investment balance. By resorting to the national income identity, past research dispensed with the analysis of how domestic capital outflows and foreign capital inflows affected the German current account deficits in the 1990s.

Figure 3 shows the bonanzas of foreign bond investment in Germany after reunification.[14] Along with the emergence of the German current account deficits, the 1990s recorded the cumulated foreign bond investment in Germany of 622.7 billion euros, substantially surpassing the cumulated German bond investment abroad of 268.9 billion euros.[15] The foreign financing of the German government debt relieved the financing conditions for the rebuilding of the new eastern territory (Seitz 1999; Sinn 2002).

German and foreign portfolio bond flows. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank. Notes: Positive values mean foreign capital inflows and domestic capital outflows. Negative values mean foreign capital outflows and domestic capital inflows.

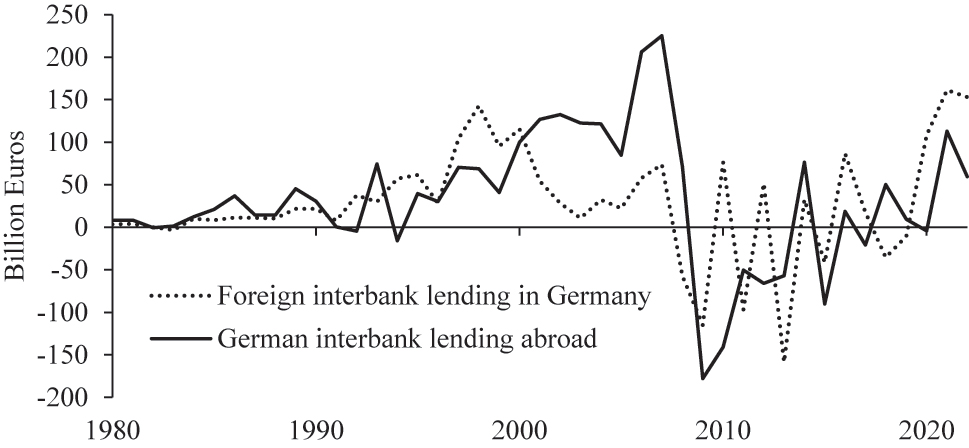

Figure 4 also shows that in the 1990s, German and foreign interbank flows followed a similar development as in bond flows. After unification, foreign interbank lending to banks in Germany increased from 21.7 billion euros in 1990 to 142.8 billion euros in 1998. By contrast, German interbank lending abroad fell from 30.8 billion euros in 1990 to −17.5 billion euros in 1994, which suggests that German banks brought back funds which had been lent to foreign banks. Overall, the 1990s saw the cumulated foreign interbank inflows of 586.6 billion euros, which were greater than the cumulated German interbank outflows of 335.7 billion euros.

German and foreign interbank flows. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank. Notes: Positive values mean foreign capital inflows and domestic capital outflows. Negative values mean foreign capital outflows and domestic capital inflows.

Macroeconomic theory suggests that the current account tends to improve in recession and deteriorate in boom (Baxter 1995; Glick and Rogoff 1995; Sachs 1981). While Germany was in a recession in the late 1990s the German current account deficits persisted (see Figure 2).[16] From a gross capital flow perspective, the German experience implies that a recession does not necessarily improve the current account when foreign capital inflows contribute to the financing of domestic consumption and investment. The foreign purchases of German government debt and the foreign bank lending freed up the domestic saving for the financing of domestic expenditures in Germany, which sustained the German current account deficits.[17]

4.2 Surges of German Capital Outflows, Stops of Foreign Capital Inflows and Current Account Surpluses in the Early 2000s

The phenomenon of the German persistent and large current account surpluses dates back to the 2000s (see Figure 3). Three macroeconomic factors substantially changed the behavior of Germany’s gross capital flows which drove the current account into surplus. First, the dotcom bubble created the so-called “Neuer Markt” in Germany, a German equivalent of the US Nasdaq, opened in 1997 and closed in 2003. The Neuer Markt allowed German technology firms with low creditworthiness to obtain access to the international capital market (Taylor 2006; Vitols 2001). Figure 5 shows that the bonanza of foreign capital inflows from the end of the 1990s to the turn of the millennium was followed by a sudden stop of foreign capital inflows.[18] The sharp decline of foreign investment inflows weakened aggregate investment in Germany (Koo 2013).

German and foreign direct investment flows. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank. Notes: Positive values mean foreign capital inflows and domestic capital outflows. Negative values mean foreign capital outflows and domestic capital inflows.

Second, the process of the euro-area interest rate convergence involved a decline of interest rate levels in the southern European countries relative to Germany (Figure 6). From the European Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis in September 1992 to the end of the euro-area interest rate convergence in December 1999, the Bundesbank cut its policy rate by 5.75 % points, whereas central banks in southern Europe cut their policy rates in average by 10.8 % points.[19] Immediately after the start of the common monetary policy in 1999, the ECB cut the policy rate from 3.75 % in October 2000 to 1.0 % by June 2003 in response to the bust of the dotcom bubble. The transition from a high to low interest rate level eased the financing constraints in southern Europe, resulting in region-specific Mises-Hayek-type overinvestment booms (Schnabl 2017). The high demand for the financing of consumption and investment expenditures in the southern European countries led to the surges of German capital outflows from the late 1990s, inter alia via German purchases of foreign bonds and German interbank lending (see Figures 3 and 4; see also Bonatti and Fracasso 2013).[20]

Policy rate convergence in Europe. Source: ECB.

Third, the economic reforms “Agenda 2010” under Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, started from the year 2003, increased aggregate saving in Germany. The structural reforms curtailed government expenditure and cut the future obligations of the social security system. It promoted household saving by giving subsidies to the retirement saving plans (Riester-Rente) and by raising consumption tax. It increased corporate saving as a result of the wage austerity triggered by the structural reforms (see Murai and Schnabl 2021). The harsh structural reforms in Germany not only curbed domestic consumption and investment, but also raised aggregate saving which equals the amount of income not consumed or invested. The low demand for the financing of domestic expenditures resulted in the decline of foreign interbank lending (see Figure 4). The resulting increase of German saving supported German capital outflows.[21]

Seen through the lens of gross capital flows, the mix of German fiscal tightening and the ECB’s monetary easing led to the surges of German capital outflows and the declines of foreign capital inflows from the late 1990s. The rise of German capital outflows and the fall of foreign capital inflows tightened the domestic financing constraints and eased the financing constraints abroad, in particular in other parts of the euro area. As Tinbergen’s (1962) gravity theory suggests that the volume of bilateral trade is closely linked to the economic size and the distance of two countries, the development of German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows was linked to the strong growth of German net exports, inter alia vis-à-vis other European countries (Murai and Schnabl 2021). The outcome is the sharp improvement of the German current account in the early 2000s and the deterioration of the current account in the southern European countries, giving rise to the emergence of the intra-euro area current account imbalances.

4.3 Gross Capital Flows and Persistent Current Account Surpluses from the Late 2000s

The US subprime crisis in 2008 triggered a sharp contraction of international capital flows (Borio and Disyatat 2015; Forbes and Warnock 2012) which led to the outbreak of the European financial and debt crisis (Litsios and Pilbeam 2017; Unger 2017). Nevertheless, Germany continued to record the huge current account surpluses which persisted even during the coronavirus crisis and the Russia-Ukraine war. There are three macroeconomic channels through which German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows have contributed to sustaining the persistent German current account surpluses since the late 2000s.

The first channel is the German public capital outflows via Target2, or the euro-area interbank payment system which allows commercial banks to settle cross-border transactions with central bank money. The Eurosystem’s national central banks are responsible for the creation of central bank money in their own jurisdiction in accordance with the ECB’s monetary policy. If, for instance, central bank money created in Italy is transferred to Germany, the Deutsche Bundesbank acquires Target2 claims and the Banca d’Italia acquires Target2 liabilities. From a balance of payments perspective, the Bundesbank’s Target2 claims can be seen as German public capital outflows as they de facto equal public credit from the Bundesbank to other central banks, which automatically occurs in the Target2 system.[22] The balance of payments statistics records Target2 claims as an increase of domestic assets abroad in the financial account.

A rising Target2 imbalance thus reflects a creation of central bank money for commercial banks in one part of the euro area, allowing for the transfer of central bank money to commercial banks in another part of the euro area. As the creation of central bank money is closely linked to the ECB’s monetary policy, the Target2 imbalances developed along with a series of the ECB’s monetary policy measures in the European financial and debt crisis (Reinhart 2017, 2018; Sinn 2020).[23] It included inter alia unlimited credit provision to banks at a fixed interest rate from 2008 (full allotment policy), the Securities Market Programme (SMP) from 2010, subsidies for bank lending to firms and households from 2014 (targeted longer-term refinancing operations, TLTROs) and the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) from 2015.[24] In 2020, the ECB started with the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) in response to the coronavirus crisis.[25] Figure 7 shows that the Bundesbank’s Target2 claims mainly reflects the Target2 liabilities of central banks in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

Target2 Balances of the Eurosystem. Source: ECB. Notes: Others include ECB, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, France, Croatia, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Slovenia, Slovakia, Out-NCBs.

The effects of German public capital outflows via Target2 on the German current account percolate through the financial system. When the financial crises dried up intra-euro area private capital flows, banks in southern Europe resorted to the borrowing from the Eurosystem (Merler and Pisani-Ferry 2012). Thus Target2 sustained the financing of the imports of German goods as well as the purchases of German financial assets by southern European countries, as reflected in the close correlation between the Target2 claims and the German current account surpluses until the early 2010s (Sinn and Wollmershäuser 2012).

The ECB’s asset purchases under the APP from 2015 and the PEPP from 2020 expanded the Target2 imbalances (see Figure 7). The ECB’s quantitative easing led to the transfer of the bulk of newly created euro deposits to Germany (Eisenschmidt et al. 2017) as commercial banks inside as well as outside the euro area often access Target2 via the Bundesbank (Hristov, Hülsewig, and Wollmershäuser 2019). If, for instance, a US commercial bank holds a current account at the Bundesbank, the Banca d’Italia’s purchases of the Italian government bonds from this US bank involve the transfer of euro deposits from Italy to Germany. Accordingly, the Bundesbank acquires the Target2 claims and the Banca d’Italia acquires the Target2 liabilities.

The ECB’s asset purchases may have blurred a close relationship between the intra-euro area Target2 imbalances and current account imbalances. German exports, for instance, can result in the transfer of deposits from foreign creditors’ bank accounts at the Bundesbank to the banks of German exporters which also have bank accounts at the Bundesbank. The transactions do not involve the Target2 system. Seen through this lens, it is not surprising that the close relationship between the Target2 imbalances and the intra-euro area current account imbalances pointed out by Sinn and Wollmershäuser (2012) weakened with the start of the ECB’s asset purchases. What remains unchanged from a gross capital flow perspective is that the Eurosystem’s asset purchases contributed to more favorable financing conditions in the euro area (Hristov, Hülsewig, and Wollmershäuser 2019) with a positive impact on the German current account balance.

The second channel is the fall of private foreign capital inflows and the rise of private German capital outflows. The German restrictive fiscal policy stance since the late 1990s (Deutsche Bundesbank 2005; Murai and Schnabl 2021; OECD 1998; Rodden 2003) has been a major impediment to foreign capital inflows in Germany. Prominently, the debt brake introduced in 2009 limited the supply of new German government bonds to roughly 0.35 % of annual GDP. Figure 8 shows the decrease of the German government debt from 2012 to 2020. Moreover, the Bundesbank’s government bond purchases via the ECB’s Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) from 2015 decreased the foreign investors’ holdings. From Q1.2015 to Q4.2018, the German government bond holdings by foreign investors decreased by 347 billion euros, which corresponds to the increase of 344 billion euros in the bond holdings by the Bundesbank.

Outstanding German government debt by holders. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank.

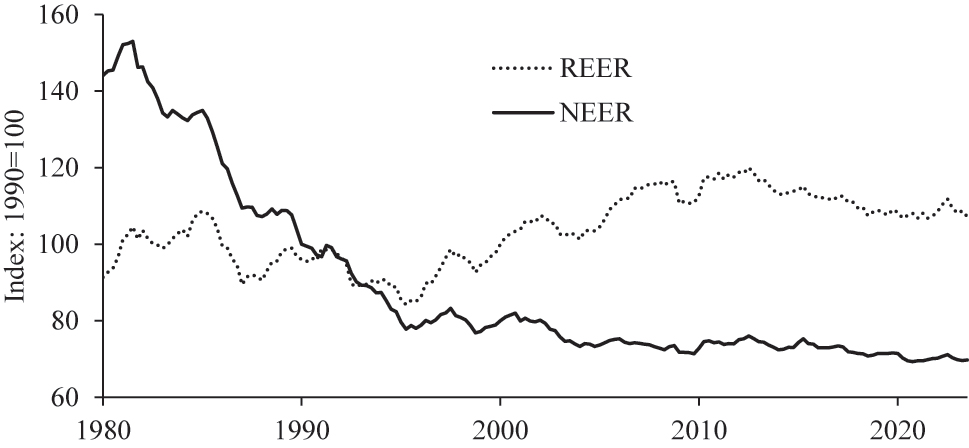

The debt brake has restricted foreign capital inflows from the late 2000s (see Figure 3) and curbed the wage growth in Germany which had been under pressure from the late 1990s.[26] Figure 9 shows that a devaluation of the real effective exchange rate (REER) occurred since the late 1990s relative to the nominal exchange rate. From 1995 to 2012, the REER depreciated by 34.4 %, while the nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) appreciated by 3.6 %.

Nominal and real effective exchange rates. Source: OECD. Notes: The NEER is calculated as the geometric weighted average of bilateral exchange rates with 27 countries; the REER is adjusted by unit labor costs in manufacturing. An increase of the index shows depreciation and a decrease of the index shows appreciation.

Moreover, the ECB’s monetary easing from 2008 led to the fall of interest rate levels in the euro area. The fall of returns on domestic saving products encouraged German capital outflows, inter alia to foreign stock markets.[27] Figure 10 shows that until the coronavirus crisis, the German foreign stock investment from the late 2000s was at historical highs.

German and foreign equity investment flows. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank. Notes: Positive values mean foreign capital inflows and domestic capital outflows. Negative values mean foreign capital outflows and domestic capital inflows.

From a gross capital flow perspective, the mix of fiscal tightening and monetary easing restrained foreign capital inflows and stimulated German capital outflows. It implies an impediment to the circulation of German and foreign capital into the German economy, putting the growth of domestic wage levels under pressure. The resulting real devaluation contributed to the international competitiveness of German export industries at the expense of domestic-market-oriented industries, sustaining the German current account surpluses.

The third channel is the substantial increase of Germany’s net foreign assets. Assuming no revaluation effects arising from changes in asset prices or exchange rate movements, net foreign assets display the accumulated net purchases of foreign assets.[28] Put differently, in the absence of revaluation effects, net foreign assets can be seen as the accumulation of an excess of domestic capital outflows over foreign capital inflows from the past to the present.

With the persistent excess of German capital outflows over foreign capital inflows from the 2000s, Germany’s net foreign assets have grown. Figure 11 shows that the growth of net foreign assets is closely related to the growth of the primary income balance which records the net investment income received and paid via-a-vis the rest of the world. From 2004 to 2022, the average growth rate for Germany’s net foreign assets and primary income balance was 24.6 and 19.7 %.

Primary income balance and net foreign assets. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank.

Since the primary income balance is part of the current account balance, Germany’s large net foreign assets have gradually developed as a key determinant of the persistent German current account surpluses. In fact, the year 2022 recorded the primary income surplus of 150 billion euros, surpassing the trade surplus of 111.9 billion euros. Seen through the lens of gross capital flows, the growing importance of primary income in the German current account surplus is not only a long-term outcome of strong German capital outflows and weak foreign capital inflows. It also points at the growing dominance of the financial account over the current account.

5 Outlook

Following a decade of current account deficits after unification in 1990, Germany has persistently run large current account surpluses. The common approaches, inter alia the saving-investment approach, pay scant attention to the causal relationship between the current account and financial account. By superimposing the national income identity on the causal relationship between the current account and financial account, the common explanation dispenses with the analysis on the role of domestic capital outflows and foreign capital inflows in international trade. Put differently, the behaviors of gross capital flows and real resource flows are assumed to be jointly determined by imbalances between domestic saving and investment.

Using the Toda-Yamamoto Granger procedure in a multivariate framework, the paper finds that from Q1.1980 to Q2.2023 for Germany, the causality runs from the financial account to the current account. Given the real exchange rate, both German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows granger-cause German exports and imports, but not the other way around. This implies that the effect of gross capital flows can be assumed to be translated into the German current account through the real exchange rate because both German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows granger-cause the real exchange rate, which in turn granger-causes German exports and imports. Overall, the real exchange rate is a key linking variable for the causal relationship running from the financial account to the current account in Germany.

The development of gross capital flows has shaped the development of the German current account. The surges of foreign capital inflows after 1990 unification turned the German current account into deficits as the foreign financing of domestic expenditures freed up domestic saving, which expanded the financing capacity for domestic expenditures. The fall of foreign capital inflows and the rise of German capital outflows from the early 2000s tightened the financing constraints, resulting in the excess of saving over investment. The transfer of purchasing power from Germany to the rest of the world was accompanied by the depressed wage growth, as reflected in the long-term depreciation of the German wage-based real exchange rate.

The real devaluation improved the international competitiveness of German export industries at the expense of domestic-market-oriented industries, supporting the current account surpluses from the early 2000s. The German current account surpluses have since then become persistent because the persistent excess of domestic capital outflows over foreign capital inflows led to the accumulation of net foreign assets. As a result, the primary income surplus has strongly grown and became the main driver of the German current account surplus in the year 2022.

As once argued by several prominent economists, such as Mises (1912), Böhm-Bawerk (1914), Ohlin (1929), Machlup (1964), and Kindleberger (1976), the paper showed that international capital flows recorded in the financial account interact with the real economic development and act as a central determinant of the current account balance. Given the fact that the persistent German current account surplus has been a frequent source of political conflicts in Europe and beyond (Belke and Schnabl 2013), the effect of macroeconomic policymaking on German capital outflows and foreign capital inflows should deserve more attention. In fact, the German fiscal expansions from 2020, e.g. the suspension of debt brake, led to the expansion of foreign capital inflows and domestic spending, which resulted in the decline of the German current account surplus in 2022.

The German current account surpluses might further be reduced if the ECB would create a higher interest rate environment. The impact of monetary tightening on gross capital flows between Germany and other parts of the euro area might not be significant as an increase of the interest rate level by the ECB affects all euro area countries. By contrast, the impact of monetary tightening on gross capital flows between Germany and other industrialized countries outside the euro area might be significant if the ECB would raise the interest rate level to a stronger extent than other central banks of major currencies, inter alia the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England or the Bank of Japan. In this scenario, less German capital would drain out of the German economy and more foreign capital would be invested in the German economy.

References

Adriana, Davidescu. 2014. “Revisiting the Relationship Between Unemployment Rates and Shadow Economy. A Toda-Yamamoto Approach for the Case of Romania.” Procedia Economics and Finance 10: 227–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2212-5671(14)00297-4.Search in Google Scholar

Alexander, Sidney. 1952. “Effects of a Devaluation on a Trade Balance.” IMF Staff Papers 2 (2): 263–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/3866218.Search in Google Scholar

Andersen, PalleS. 1990. “Developments in External and Internal Balances.” BIS Economic Papers No. 29.Search in Google Scholar

Avdjiev, Stefan, Robert McCauley, and Hyun Song Shin. 2016. “Breaking Free of the Triple Coincidence in International Finance.” Economic Policy 31 (87): 409–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiw009.Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, Adam B., Lionel Barnett, and Anil K. Seth. 2010. “Multivariate Granger Causality and Generalized Variance.” Physical Review E 81 (4): 0410907, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.81.041907.Search in Google Scholar

Baxter, Marianne. 1995. “International Trade and Business Cycles.” In Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 3, edited by Gene Grossman, and Kenneth Rogoff, 1801–64. Amsterdam: North-Holland.10.1016/S1573-4404(05)80015-2Search in Google Scholar

Bayoumi, Tamim, and Ronald MacDonald. 1995. “Consumption, Income, and International Capital Market Integration.” IMF Staff Papers 42 (3): 552–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867532.Search in Google Scholar

Belke, Ansgar, and Gunther Schnabl. 2013. “Four Generations of Global Imbalances.” Review of International Economics 21 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12015.Search in Google Scholar

Beretta, Edoardo, and Alvaro Cencini. 2020. “Double-Entry Bookkeeping and the Balance of Payments: The Need for a Substantial, Conceptual Reform. IFC Conference on External Statistics ‘Bridging Measurement Challenges and Analytical Needs of External Statistics: Evolution or Revolution?’ (IFC Bulletins chapters).” In Bridging Measurement Challenges and Analytical Needs of External Statistics: Evolution or Revolution?, edited by Bank for International Settlements, Vol. 52. Basel: Bank for International Settlement.Search in Google Scholar

Berger, Bennet, and Guntram Wolff. 2017. “The Global Decline in the Labour Income Share: Is Capital the Answer to Germany’s Current Account Surplus?” Bruegel Policy Contribution No. 12.Search in Google Scholar

Bernanke, Ben. 2005. “The Global Saving Glut and the US Current Account Deficit.” In Speech at the Sandridge Lecture. Richmond: Virginia Association of Economics.Search in Google Scholar

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Von. 1914. “Gesammelte Schriften von Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk.” In Unsere passive Handelsbilanz, edited by Franz Weiss. Vienna and Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky A.G.Search in Google Scholar

Bonatti, Luigi, and Andrea Fracasso. 2013. “The German Model and the European Crisis.” Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (6): 1023–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12067.Search in Google Scholar

Bonfim, Diana, and André Capela. 2020. “The Effect of Corporate Bond Purchases by the ECB on Firms’ Borrowing Costs.” Banco de Portugal Economic Studies 2: 1–25.Search in Google Scholar

Borio, Claudio. 2014. Monetary Policy and Financial Stability: What Role in Prevention and Recovery. BIS Working Papers No. 440.10.24149/gwp203Search in Google Scholar

Borio, Claudio, and Piti Disyatat. 2011. Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Link or No Link? BIS Working Papers No. 346.10.2139/ssrn.1859410Search in Google Scholar

Borio, Claudio, and Piti Disyatat. 2015. Capital Flows and the Current Account: Taking Financing (More) Seriously. BIS Working Papers No 525.Search in Google Scholar

Börsch-Supan, Axel, and Angelik Eymann. 2002. “Household Portfolios in Germany.” In Household Portfolios, edited by Luigi Guiso, Michael Haliassos, and Tullio Jappelli, 291–340. Cambridge: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/3568.003.0013Search in Google Scholar

Boss, Alfred, and Astrid Rosenschon. 1996. “Öffentliche Transferleistungen zur Finanzierung der deutschen Einheit: Eine Bestandsaufnahme.” In Kieler Diskussionsbeiträge No. 269. Kiellinie: Institut für Weltwirtschaft.Search in Google Scholar

Broner, Fernando, Tatiana Didier, Aitor Erce, and Sergio Schmukler. 2013. “Gross Capital Flows: Dynamics and Crises.” Journal of Monetary Economics 60 (1): 113–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2012.12.004.Search in Google Scholar

Calvo, Guillermo A., Leonardo Leiderman, and Carmen M. Reinhart. 1993. “Capital Inflows and Real Exchange Rate Appreciation in Latin America: The Role of External Factors.” IMF Staff Papers 40: 108–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867379.Search in Google Scholar

Coughlin, Cletus, and Kees Koedijk. 1990. “What Do We Know About the Long-Run Real Exchange Rate?” St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank Review 72 (1): 36–48. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.72.35-48.Search in Google Scholar

Cowan, Kevin, José De Gregorio, Alejandro Micco, and Christopher Neilson. 2008. “Financial Diversification, Sudden Stops and Sudden Starts.” In Series on Central Banking, Analysis, and Economic Policies No. 12. Santiago: Central Bank of Chile.Search in Google Scholar

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2005. “Deficit-Limiting Budgetary Rules and a National Stability Pact in Germany.” Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report 54 (7): 23–37.Search in Google Scholar

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2007. “TARGET2 – The New Payment System for Europe.” Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report October 59 (10): 69–82.Search in Google Scholar

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2011. “The Dynamics of the Bundesbank’s TARGET2 Balance.” Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report 63 (3): 34–5.Search in Google Scholar

Diebold, Francis X. 2004. Elements of Forecasting. Ohio: Thompson Learning.Search in Google Scholar

Dinh, Doan Van. 2020. “Impulse Response of Inflation to Economic Growth Dynamics: VAR Model Analysis.” The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 7 (9): 219–28. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no9.219.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenschmidt, Jens, Danielle Kedan, Martin Schmitz, Ramón Adalid, and Patrick Papsdorf. 2017. “The Eurosystem’s Asset Purchase Programme and TARGET Balances.” ECB Occasional Paper 196.10.2139/ssrn.3039951Search in Google Scholar

Eleftheriou, Maria, and Nikolas Müller-Plantenberg. 2018. “The Purchasing Power Parity Fallacy: Time to Reconsider the PPP Hypothesis.” Open Economies Review 29 (3): 481–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9473-9.Search in Google Scholar

Engel, Charles. 1999. “Accounting for US Real Exchange Rate Changes.” Journal of Political Economy 107 (3): 507–38. https://doi.org/10.1086/250070.Search in Google Scholar

Faroque, Akhter, and William Veloce. 1990. “Causality and the Structure of Canada’s Balance of Payments: Evidence from Time Series.” Empirical Economics 15: 267–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02426969.Search in Google Scholar

Felbermayr, Gabriel, Clemens Fuest, and Timo Wollmershäuser. 2017. “The German Current Account Surplus: Where Does It Come from, is It Harmful and Should Germany Do Something About It?” EconPol Policy Report 1 (2): 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

Feldstein, Martin, and Charles Horioka. 1980. “Domestic Saving and International Capital Flows.” The Economic Journal 90 (358): 314–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2231790.Search in Google Scholar

Fieleke, Norman S. 1996. What is the Balance of Payments? 1–12. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.Search in Google Scholar

Forbes, Kristin, and Francis Warnock. 2012. “Capital Flow Waves: Surges, Stops, Flight, and Retrenchment.” Journal of International Economics 88 (2): 235–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2012.03.006.Search in Google Scholar

Fraga, Arminio. 1986. “German Reparations and Brazilian Debt: A Comparative Study.” Essays in International Finance 163.Search in Google Scholar

Giles, Dave. 2011. Testing for Granger Causality. http://davidgiles.blogspot.co.uk/2011/04/testing_for_granger_causality.html (accessed September 20, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Glick, Reuven, and Kenneth Rogoff. 1995. “Global versus Country-Specific Productivity Shocks and the Current Account.” Journal of Monetary Economics 35 (1): 159–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(94)01181-9.Search in Google Scholar

Golub, Stephen. 1990. “International Capital Mobility: Net versus Gross Stocks and Flows.” Journal of International Money and Finance 9 (4): 424–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5606(90)90020-z.Search in Google Scholar

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Hélène Rey. 2014. “External Adjustment, Global Imbalances, Valuation Effects.” In Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 4, edited by Gita Gopinath, Elhanan Helpman, and Kenneth Rogoff, 585–645. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-444-54314-1.00010-0Search in Google Scholar

Granger, Clive W. J., and Paul Newbold. 1974. “Spurious Regressions in Econometrics.” Journal of Econometrics 2 (2): 111–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(74)90034-7.Search in Google Scholar

Gros, Daniel, and Matthias Busse. 2013. “The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure and Germany: When is a Current Account Surplus an ‘Imbalance’?” CEPS Policy Briefs (301).Search in Google Scholar

Hacker, R. Scott, and Abdulnasser Hatemi-J. 2006. “Tests for Causality between Integrated Variables Using Asymptotic Bootstrap Distributions: Theory and Applications.” Applied Economics 38 (13): 1489–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840500405763.Search in Google Scholar

Harberger, Arnold. 1950. “Currency Depreciation, Income, and the Balance of Trade.” Journal of Political Economy 58 (1): 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/256897.Search in Google Scholar

Hayakawa, Kazunobu, and Hiroshi Mukunoki. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on International Trade: Evidence from the First Shock.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 60 (C 101135).10.1016/j.jjie.2021.101135Search in Google Scholar

Heid, Frank, Thorsten Nestmann, Beatrice Weder, and Natalja von Westernhagen. 2004. “German Bank Lending During Emerging Market Crises: A Bank Level Analysis.” In Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper Series 2, Banking and Financial Supervision, Vol. 4. Frankfurt: Deutsche Bundesbank.10.2139/ssrn.605562Search in Google Scholar

Hein, Eckhard, and Achim Truger. 2005. “What Ever Happened to Germany? Is the Decline of the Former European Key Currency Country Caused by Structural Sclerosis or by Macroeconomic Mismanagement?” International Review of Applied Economics 19 (1): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269217042000312588.Search in Google Scholar

Higgins, Matthew, and Thomas Klitgaard. 1998. “Viewing the Current Account Deficit as a Capital Inflow.” Current Issues in Economics and Finance 4 (13): 1–6.10.2139/ssrn.997029Search in Google Scholar

Holtfrerich, Carl-Ludwig. 1986. “U.S. Capital Exports to Germany 1919–1923 Compared to 1924–1929.” Explorations in Economic History 23 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4983(86)90017-3.Search in Google Scholar

Homburg, Stefan. 2012. “Notes on the Target2 Dispute.” CESifo Forum 13 (Special Issue) 50–54.Search in Google Scholar

Homburg, Stefan. 2018. “Speculative Eurozone Attacks and Departure Strategies.” CESifo Working Paper Series 7343.10.2139/ssrn.3338670Search in Google Scholar

Hristov, Nikolay, Oliver Hülsewig, and Timo Wollmershäuser. 2019. “TARGET2: Understanding the Glue that Keeps the Euro Together.” In Highs and Lows of European Integration: Sixty Years After the Treaty of Rome, edited by Luisa Antoniolli, Luigi Bonatti, and Carlo Ruzza, 201–11. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-93626-0_11Search in Google Scholar

Hwang, Inbin, Jeong Deokjong, Park Hyungsoon, and Park Sunyoung. 2017. “Which Net Capital Flows Matter?” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53 (2): 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496x.2016.1212705.Search in Google Scholar

International Monetary Fund’s. 2009. The Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, 6th ed. Washington: International Monetary Fund.Search in Google Scholar

Johansen, Soren, and Katarina Juselius. 1990. “Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Inference on Cointegration – With Applications to the Demand for Money.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 52 (2): 169–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1990.mp52002003.x.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Harry. 1977. “The Monetary Approach to Balance of Payments Theory and Policy: Explanation and Policy Implications.” Economica 44 (175): 217–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2553647.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Karen. 2009. “Gross or Net International Financial Flows: Understanding the Financial Crisis.” In Council on Foreign Relations Working Paper. New York: Council on Foreign Relations.Search in Google Scholar

Keynes, John Maynard. 1929. “The German Transfer Problem.” Economic Journal 39 (153): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/2224211.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Chul-Hwan, and Donggeun Kim. 2011. “Do Capital Inflows Cause Current Account Deficits?” Applied Economics Letters 18 (5): 497–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851003724267.Search in Google Scholar

Kindleberger, Charles. 1976. “Germany’s Persistent Balance of Payments Disequilibrium Revisited.” Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review 29: 118–50.Search in Google Scholar

Klappholz, Kurt, and Ezra Mishan. 1962. “Identities in Economic Models: “Nothing Will Come of Nothing”- King Lear.” Economica 29 (114): 117–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2551548.Search in Google Scholar

Koo, Richard. 2013. Central Banks in Balance Sheet Recessions: A Search for Correct Response. Technical Report. Chiyoda-ku: Nomura Research Institute.Search in Google Scholar

Krugman, Paul, Maurice Obstfeld, and Marc Melitz. 2015. International Economics: Theory and Policy, 10th ed. Boston: Pearson.Search in Google Scholar

Legroux, Vincent, Imène Rahmouni-Rousseau, Urszula Szczerbowicz, and Natacha Valla. 2022. “Stabilising Virtues of Central Banks: (Re)Matching Bank Liquidity.” Journal of Banking & Finance 134: 106–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2021.106323.Search in Google Scholar

Lerner, Abba. 1936. “The Symmetry Between Import and Export Taxes.” Economica 3 (11): 306–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/2549223.Search in Google Scholar

Litsios, Ioannis, and Keith Pilbeam. 2017. “An Empirical Analysis of the Nexus between Investment, Fiscal Balances and Current Account Balances in Greece, Portugal and Spain.” Economic Modelling 63: 143–52.10.1016/j.econmod.2017.02.003Search in Google Scholar

Lütkepohl, Helmut. 1982. “Differencing Multiple Time Series: Another Look at Canadian Money and Income Data.” Journal of Time Series Analysis 3 (4): 235–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.1982.tb00346.x.Search in Google Scholar

Machlup, Fritz. 1964. “The Transfer Problem: Theme and Four Variations.” In International Payments, Debts and Gold, 374–95. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.Search in Google Scholar

Manger, Mark, and Thomas Sattler. 2020. “The Origins of Persistent Current Account Imbalances in the Post-Bretton Woods Era.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (3–4): 631–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019859031.Search in Google Scholar

Marshall, Alfred. 1923. Money, Credit, and Commerce. New York: Macmillan and Company.Search in Google Scholar

Mastroyiannis, Anastasios. 2012. “Causality Relationships in the Structure of Portugal’s Balance of International Payments.” International Journal of Business and Social Science 3 (15): 54–61.Search in Google Scholar

McCauley, Robert. 1999. “The Euro and the Liquidity of European Fixed Income Markets (CGFS Papers chapter).” In Market Liquidity: Research Findings and Selected Policy Implications, edited by Bank for International Settlements, Vol. 11, 1–26. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.Search in Google Scholar

Meade, JamesE. 1970. The Balance of Payments. London, New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Merler, Silvia, and Jean Pisani-Ferry. 2012. “Sudden Stops in the Euro Area.” Bruegel Policy Contribution No. 6.10.5202/rei.v3i3.97Search in Google Scholar

Micossi, Stefano, Alexandra D’Onofrio, and Fabrizia Peirce. 2018. “On German External Imbalances.” In CEPS Policy Insight, Vol. 13. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.10.2139/ssrn.3471151Search in Google Scholar

Mises, Ludwig von. 1912 [1953]. The Theory of Money and Credit. New Haven: Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Murai, Taiki, and Gunther Schnabl. 2021. “Macroeconomic Policy Making and Current Account Imbalances in the Euro Area.” Credit and Capital Markets 54 (3): 347–73. https://doi.org/10.3790/ccm.54.3.347.Search in Google Scholar

Nyborg, Kjell G. 2017. “Central Bank Collateral Frameworks.” Journal of Banking & Finance 76: 198–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.12.010.Search in Google Scholar

Obstfeld, Maurice. 2012. “Does the Current Account Still Matter?” American Economic Review 102 (3): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17877.Search in Google Scholar

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff. 1995. “The Intertemporal Approach to the Current Account.” Handbook of International Economics 3: 1731–99.10.1016/S1573-4404(05)80014-0Search in Google Scholar

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2005. “Global Current Account Imbalances and Exchange Rate Adjustments.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 67–146. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2005.0020.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. 1998. OECD Economic Surveys, 1997–1998: Germany. Paris: OECD.Search in Google Scholar

Ohlin, Bertil. 1929. “The German Transfer Problem: A Discussion, I. Transfer Difficulties, Real and Imagined.” Economic Journal 39 (154): 172–8.10.2307/2224537Search in Google Scholar

Packer, Frank, Ryan Stever, and Christian Upper. 2007. “The Covered Bond Market.” BIS Quarterly Review September.Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, Peter C. B. 1986. “Understanding the Spurious Regression in Econometrics.” Journal of Econometrics 33 (3): 311–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(86)90001-1.Search in Google Scholar

Prasad, Eswar, Raghuram Rajan, and Arvind Subramanian. 2006. “Patterns of International Capital Flows and Their Implications for Economic Development.” In Presented at the Symposium “The New Economic Geography: Effects and Policy Implications”. Kansas City, MO: The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.Search in Google Scholar

Rambaldi, Alicia, and Howard Doran. 1996. “Testing for Granger Non-Causality in Cointegrated Systems Made Easy.” In Working Paper in Econometrics and Applied Statistics No. 88. Armidale: Department of Econometrics, University of New England.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Carmen. 2017. Overview Panel. https://web.archive.org/web/20180221000010/https://www.kansascityfed.org/∼/media/files/publicat/sympos/2017/reinhart-remarks.pdf?la=en.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Carmen. 2018. Italy’s Long Hot Summer, Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/Italy-sovereign-debt-restructuring-by-carmen-reinhart-2018-05?barrier=accesspaylog.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Carmen, and Vincent Reinhart. 2009. “Capital Flow Bonanzas: An Encompassing View of the Past and Present.” In NBER International Seminar in Macroeconomics 2008, edited by Jeffrey Frankel, and Francesco Giavazzi. Chicago: Chicago University Press.10.3386/w14321Search in Google Scholar

Rodden, J. 2003. “Soft Budget Constraints and German Federalism.” In Fiscal Decentralization and the Challenge of Hard Budget Constraints, edited by Jonathan Rodden, Gunnar Eskeland, and Jennie Litvack, 161–86. Cambridge: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/3021.003.0009Search in Google Scholar

Rueff, Jacques. 1929. “Mr. Keynes’ Views on the Transfer Problem.” Economic Journal 39 (155): 388–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/2224179.Search in Google Scholar

Sachs, Jeffrey. 1981. “The Current Account and Macroeconomic Adjustment in the 1970s.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 201–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534399.Search in Google Scholar

Schindele, Alexandra, and Andrea Szczesny. 2016. “The Impact of Basel II on the Debt Costs of German SMEs.” Journal of Business Economics 86 (3): 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-015-0775-3.Search in Google Scholar

Schnabl, Gunther. 2017. “Monetary Policy and Overinvestment in East Asia and Europe.” Asia Europe Journal 15 (4): 445–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0490-5.Search in Google Scholar

Schnabl, Gunther, and Holger Zemanek. 2012. “German Unification and Intra-European Imbalances.” In European Integration in a Global Economy, edited by Ewald Nowotny, Peter Mooslechner, and Doris Ritzberger-Grünwald, 53–68. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Schularick, Moritz. 2016. “International Capital Flows.” In Oxford Handbook of Banking and Financial History, edited by Youssef Cassis, Catherine Schenk, and Richard Grossman, 262–92. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199658626.013.14Search in Google Scholar

Seitz, Helmut. 1999. “Where Have All the Flowers Gone? Die öffentlichen Finanzen in den neuen Ländern.” Ifo Schnelldienst 32 (3): 26–34.Search in Google Scholar

Shahzad, Syed Jawad Hussain, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar, Muhammad Zakaria, and Maryam Hur. 2017. “Carbon Emission, Energy Consumption, Trade Openness and Financial Development in Pakistan: A Revisit.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 70: 185–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.042.Search in Google Scholar

Shin, Hyun Song. 2012. “Global Banking Glut and Loan Risk Premium.” IMF Economic Review 60 (2): 155–92. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2012.6.Search in Google Scholar

Sinn, Hans-Werner. 2002. “Germany’s Economic Unification: An Assessment After Ten Years.” Review of International Economics 10 (1): 113–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9396.00321.Search in Google Scholar

Sinn, Hans-Werner. 2020. The Economics of Target Balances. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-50170-9Search in Google Scholar

Sinn, Hans-Werner, and Timo Wollmershäuser. 2012. “Target Loans, Current Account Balances and Capital Flows: The ECB’s Rescue Facility.” International Tax and Public Finance 19 (4): 468–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9236-x.Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, Bernard. 2006. “Corporate Governance: The Crisis, Investors’ Losses and the Decline in Public Trust.” Corporate Governance 11 (3): 155–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8683.00314.Search in Google Scholar

Tinbergen, Jan. 1962. Shaping the World Economy: Suggestions for an International Economic Policy. New York: Twentieth Century Fund.Search in Google Scholar

Toda, Hiro Y., and Taku Yamamoto. 1995. “Statistical Inference in Vector Autoregressions with Possibly Integrated Processes.” Journal of Econometrics 66 (1–2): 225–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01616-8.Search in Google Scholar

Turner, Philip. 1991. “Capital Flows in the 1980s: A Survey of Major Trends.” BIS Economic Paper (30).Search in Google Scholar

Unger, Robert. 2017. “Asymmetric Credit Growth and Current Account Imbalances in the Euro Area.” Journal of International Money and Finance 73: 435–51.10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.02.017Search in Google Scholar

Vercelli, Alessandro. 2019. Finance and Democracy: Towards a Sustainable Financial System. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-27912-7Search in Google Scholar

Vitols, Sigurt. 2001. “Frankfurt’s Neuer Markt and the IPO Explosion: Is Germany on the Road to Silicon Valley?” Economy and Society 30 (4): 553–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140120089090.Search in Google Scholar

Wall Street Journal. 2013. Berlin Dismisses U.S. Criticism of Economy. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304073204579169454159735052.Search in Google Scholar

Wallich, Henry, and John Wilson. 1979. “Thirty Years (Almost) of German Surpluses.” Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft/Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 135 (3): 480–92.Search in Google Scholar

Whelan, Karl. 2014. “TARGET2 and Central Bank Balance Sheets.” Economic Policy 29 (77): 79–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0327.12025.Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, Martin. 2014. The Shifts and the Shocks: What We’ve Learned – And Still Have to Learn – From the Financial Crisis. New York: Penguin.Search in Google Scholar

Yan, Ho-Don. 2005. “Causal Relationship Between the Current Account and Financial Account.” International Advances in Economic Research 11: 149–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-005-3012-y.Search in Google Scholar

Young, Brigitte. 2020. “From Sick Man of Europe to the German Economic Power House. Two Narratives: Ordoliberalism versus Euro-Currency Regime.” German Politics 29 (3): 464–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2018.1559832.Search in Google Scholar

Zapata, Hector O., and Alicia N. Rambaldi. 1997. “Monte Carlo Evidence on Cointegration and Causation.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 59 (2): 285–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.00065.Search in Google Scholar

Zemanek, Holger, Ansgar Belke, and Gunther Schnabl. 2010. “Current Account Balances and Structural Adjustment in the Euro Area.” International Economics and Economic Policy 7 (1): 83–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-010-0156-x.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Economic Policy Making Under Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- A Latticework of Inflation Models

- A Comparative Evaluation of Fiscal Stabilization Strategies during the Covid-19 Pandemic with Germany as a Reference Point

- The Relationship Between the German Current Account and Financial Account: Evidence from the Toda-Yamamoto Causality Approach

- The Tax Attractiveness of EU Locations for Corporate Investments: A Stocktaking of Past Developments and Recent Reforms

- Aid in Conflict: Determinants of International Aid Allocation to Ukraine During the 2022 Russian Invasion

- Policy Forum: Economic Policy in an Era of Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Public Debt Ratios Will Increase For Some Time. We Must Make Sure That They Do Not Explode

- An EU Fund to Incentivise Public Investments with Positive Externalities

- The Case for Putting a Public Investment Clause into the German Debt Brake

- EU Debt Instruments and Fiscal Transparency: The Case of the EU Recovery Fund

- Explaining the Divergence in German and French Public Finances

- Fiscal Prospects for Italy

- The Swiss Debt Brake Is Democratic, Strict, Transparent, and Binding. A Model to Follow?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Economic Policy Making Under Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- A Latticework of Inflation Models

- A Comparative Evaluation of Fiscal Stabilization Strategies during the Covid-19 Pandemic with Germany as a Reference Point

- The Relationship Between the German Current Account and Financial Account: Evidence from the Toda-Yamamoto Causality Approach

- The Tax Attractiveness of EU Locations for Corporate Investments: A Stocktaking of Past Developments and Recent Reforms

- Aid in Conflict: Determinants of International Aid Allocation to Ukraine During the 2022 Russian Invasion

- Policy Forum: Economic Policy in an Era of Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Public Debt Ratios Will Increase For Some Time. We Must Make Sure That They Do Not Explode

- An EU Fund to Incentivise Public Investments with Positive Externalities

- The Case for Putting a Public Investment Clause into the German Debt Brake

- EU Debt Instruments and Fiscal Transparency: The Case of the EU Recovery Fund

- Explaining the Divergence in German and French Public Finances