Abstract

This contribution, based on the proposals by Bakker, Beetsma, and Buti (2024a. “The Case for a European Public-Goods Fund.” Project Syndicate, 4 March. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/public-goods-fund-could-finance-green-transition-and-ensure-fiscal-responsibility-by-age-bakker-et-al-2024-03, 2024b. “Two Birds with One Stone: Investing in European Public Goods while Maintaining Fiscal Discipline at Home.” Intereconomics 59 (2): 1–6), discusses an EU fund to finance investments with positive cross-border spill-overs, such as large infrastructures, that are too expensive for individual countries to finance, or of which the benefits are insufficiently internalised by individual investing countries. Each country receives a given part (“envelope”) of the fund. The envelope size and the contribution as well as the eventual debt repayment burden could be proportional to the size of the economy, thereby minimising cross-border redistribution. Access to the fund’s resources is conditional on adherence to the EU’s new fiscal rulebook. If a country fails to make full use of its envelope, the remaining resources are re-allocated over the other envelopes. Hence, the fund provides an incentive for countries to simultaneously undertake investments that benefit groups of countries or the EU at large, and to maintain fiscal discipline. We discuss the size of the fund, how it fits within the EU current instrument set, its governance, its financing and its potential political appeal.

1 Introduction

The European Union faces a multitude of challenges. Among these are the digital and energy transitions, the shrinkage of the workforce, and the ageing of population with the attendant rise in the cost of pension provision and healthcare. The various challenges need to be met by current public spending and large public and private investments, at a time when the volume of savings will come under pressure through increasing dissaving of the retired. At the same time, public debt needs to stay on a sustainable path. Can all these objectives be reconciled, and how is this achieved? In this contribution, based on the proposals by Bakker, Beetsma, and Buti (2024a, 2024b), we argue for establishing an EU fund aimed at financing projects with positive cross-border spill-overs to which countries have access (only) if they adhere to the EU fiscal rules. Concrete examples of such projects are in the pipeline or are being explored. One concerns the case of Denmark which is building large offshore windfarms to generate electricity for both domestic households and those of surrounding countries. The effective broadening of the electricity grid implies that unused surpluses are reduced and the electricity flows to those places where it is needed most (Het Financieele Dagblad 2024a). The main obstacle to the project is its high cost and the challenge to finance it. Another example is the “European Silk Road”, a proposal for a high-speed rail link from Lyon to Warsaw, which could lead to substantial net CO2 savings (WIIW 2023). A final interesting example is that of TenneT, the electricity transmission system operator for the Netherlands and a significant part of Germany, which is fully owned by the Dutch government. Because of huge investment demands in the coming years, the Dutch government has been in a lengthy and complicated negotiation process with the German government of divesting the German grid system, because it is not able to carry the necessary large investments on the German side in its books on top of the 25 billion euro needed for the Dutch side of the grid system. Financing would have been made much easier by the fund proposed here.

Some recent contributions have made proposals related to the proposal made here. For example, Garicano (2022) proposes a European Climate Investment Facility which provides grants and loans to countries for investments in climate improvement. Enforcement would involve an independent fiscal assessor. Access to the fund is conditional on adherence to the fiscal rules.[1] Closest to this contribution are Bakker and Beetsma (2023) and Bakker, Beetsma, and Buti (2024a, 2024b), where access to such a fund is restricted to investments with cross-border spill-overs. Buti, Coloccia, and Messori (2023) discuss the different areas in which European Public Goods (EPGs) can be provided,[2] and their potential contribution. Demertzis, Pinkus, and Ruer (2024) propose a dedicated and permanent fund for European Strategic Investments (ESIs) to replace the multitude of finite and sporadic, often overlapping, investment programs.

2 The Revised EU Fiscal Framework

The recently agreed revision of the Stability and Growth aims at ensuring debt sustainability, while at the same time promoting reform and investment.[3] Indeed, the revised framework foresees “fiscal-structural” plans with an adjustment period of four years to put debt on a sustainable downward path and deficits comfortably below 3 % of GDP, when these are too high. This adjustment period can be extended up to a maximum of seven years, based on structural reform and investment plans that fulfil certain conditions. The plans need to promote potential growth, which makes it easier to keep the debt sustainable. This way, the revised framework provides an incentive to engage in the type of reform and investments that the EU so dearly needs. The incentive is important, because it is politically more expedient to expand social spending than to spend on causes that raise potential output. Also, when budgetary pressures rise, public investment tends to be the easiest victim.

Centre-stage in the new framework is the net primary expenditure path, defined as public expenditures, excluding discretionary tax revenues, interest payments on the public debt, the cyclical component of unemployment benefits, national co-financing of EU funds, and one-offs. Deviations of the actual net primary expenditure path from the planned one are recorded in a compensation account. Such deviations may trigger a “debt-based” Excessive Deficit Procedure.

3 The Need for Green and Digital Investments

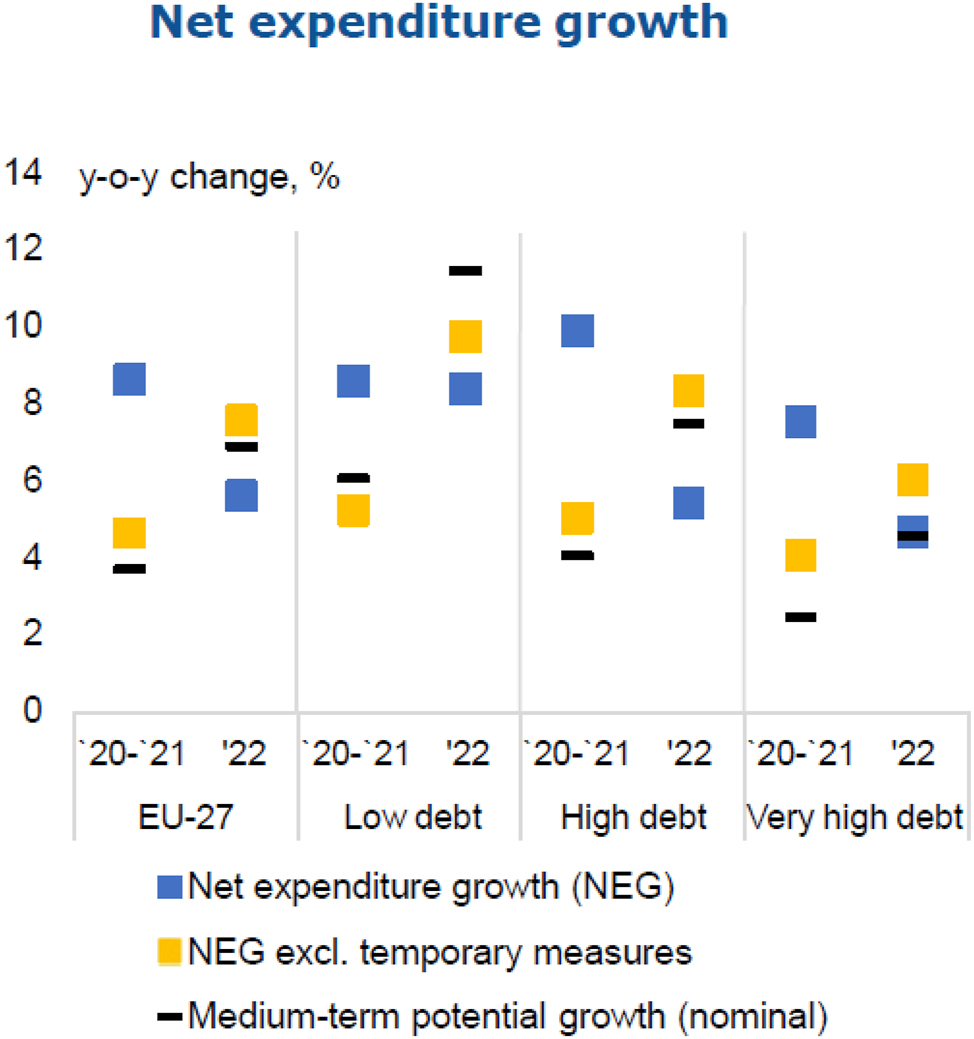

Estimates by the European Commission (2020) suggest that for the EU to achieve its 2030 climate target, requires annual investments of about 2 % of EU GDP, of which 0.5–1 % of GDP needs to come from public investment (Pisani-Ferry, Tagliapietra, and Zachmann 2023). Obviously, the overall magnitude of the required investment outlay is surrounded by substantial uncertainty, and the net cost to public budgets depends to an important extent on the chosen instruments to bring about the green transition, such as the choice between subsidies and taxes on polluting activities (e.g. Blanchard 2023). Meanwhile, there is a need for urgency, not only because the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continues to rise, but also because the savings-investment balance is likely to worsen. The demographic transition causes a rising fraction of retirees in the population. In order to maintain its consumption we would expect this group to dissave. On top of this, net borrowing by governments for current expenditures has increased during and following the Covid-19 pandemic. This has resulted in even higher public debt levels than before the pandemic, especially of countries that were already highly indebted. Public debt levels have come down to some extent on the back of high inflation, but the underlying current expenditure dynamics of the high and very high debt countries are expansionary when temporary measures related to Covid and energy prices are excluded (see Figure 1, amended from Figure 2.9 in European Fiscal Board 2023). Hence, public debt levels are set to rise again in the medium run (see Graph 2.1 in European Commission 2023).

Underlying expenditure dynamics.

4 A Fund for Investments with Beneficial Cross-Border Spill-Overs

Some have argued that the net primary expenditure path should also exclude investments in the green transition (a form of a green golden rule). While this may well stimulate such investments, there is a danger that other types of spending will be “disguised” as green investments. Moreover, the sustainability of the public debt is determined by the “overall” public finances. Excluding certain expenditures will obscure the assessment of debt sustainability (e.g. Blanchard 2023). Finally, introducing a green golden rule would further complicate the revised SGP.

However, there are better ways to stimulate green public investments, with stronger incentives, while moreover those investments better fit the needs of the EU. These investments typically have a “public good character”, in the sense that their ensuing benefits not only accrue to the country that makes the investment, but also to other countries. Hence, these investments have positive cross-border spill-overs, which also implies that in a cost-benefit analysis of these investments, the investing country will insufficiently internalise the benefits. Examples are investments in solar or wind turbines which reduce carbon emissions for the entire EU. The benefits of some investments rise disproportionately faster when additional countries are involved. This would be the case, for example, for high-speed railways, defence spending, hydrogen infrastructure and the upgrading of electricity networks.

In Bakker and Beetsma (2023) and Bakker, Beetsma, and Buti (2024a, 2024b) we propose an EU-level fund (“the Fund”) intended for the financing of public investments with positive cross-border spill-overs. The Fund could serve as a follow-up to the recovery and resilience facility (RRF) of NextGenEU, or it could co-exist with the latter. Politically, it will be easier to establish the Fund as a follow-up to NextGenEU, as that would avoid increasing current financial commitments in the very near future. Each country has its own envelope within the Fund, and can make use of the Fund for public investments, if these investments fulfil certain conditions. In particular, the investments should address EU priorities and are required to have positive cross-border spill-overs. In this sense they differ from the investments in the RRF, which are primarily focused at the national economy. RRF investments may happen to have cross-border spill-overs, but this is not a requirement for their funding through the RRF.

Countries are eligible for funding from the Fund if they are not currently subject to an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) or if they adhere to the correction path when under an EDP. Hence, a country is incentivised both to exert sufficient fiscal discipline and to propose investments that benefit not only itself, but also other countries. Funding requests can also be made by combinations of countries, provided that all countries involved in the request fulfil the above condition. One might consider further incentivising joint projects by giving a top-up to countries investing jointly. To stimulate the quality and efficiency of the investments, a certain degree of co-funding by the Member State(s) would generally be desirable. The partial funding from the EU may thus be seen as an instrument to induce the investing country to internalise the positive externalities of its investment.

In many instances, co-funding by private parties is envisaged. In those cases, governments have an essential role to coordinate the project. An example is the construction of hydrogen infrastructure, where the “common core” would be publicly provided, while individual firms would connect to the core through making their own investments and by paying user fees to cover the costs of the common core. In such cases, the public investment can be earned back.

Any funds in a country’s envelope that are unused, either because there are insufficient suitable investment projects or because the country does not adhere to the requirements of the SGP, will be redistributed over the other envelopes. Hence, each individual country has an incentive to propose suitable projects, otherwise the (remaining) content of its envelope will be distributed over the other envelopes. Deadlines should therefore be set for a country to come up with suitable projects.

The Fund can be related explicitly to the revised SGP. In the latter countries can obtain an extension of their fiscal-structural trajectory from 4 to 7 years, provided they implement public investments and reforms that fulfil certain conditions, among them those that advance EU priorities. Hence, including investments with demonstrable positive cross-border spill-overs should raise the acceptance likelihood of a proposal to extend the fiscal-structural trajectory.

5 Which Instruments do Already Exist?

Demertzis, Pinkus, and Ruer (2024) provide a very comprehensive overview of EU investment initiatives. There exist a large number of them covering different areas, different periods during which they are active, different funding sources and different instruments. In most cases, funding comes from the EU budget or NextGenEU, sometimes through direct outlays and sometimes through issuance of bonds. In some instances a mere EU budget guarantee suffices. Much of the investment falling under these initiatives is strategic, i.e. consistent with the EU’s long-term objectives and priorities, such as investment in energy and connectivity infrastructure.

Among the initiatives in the overview by Demertzis, Pinkus, and Ruer (2024) there is no fund explicitly aimed at investments with positive cross-border spill-overs. However, the EU does already have an instrument to stimulate investments of the type envisaged here. Member States are allowed to support Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) – European Commission (2024). Under certain conditions, state aid rules “enable Member States and the industry to jointly invest in breakthrough innovation and infrastructure. They do so when the market alone does not deliver, because the risks are too big for a single Member State or company to take. And it has to benefit the EU economy at large” (Vestager in European Commission 2021a). Important conditions are that a project contributes in an important way to the EU objectives; demonstrably overcomes important market failures; involves at least four Member States; yields concrete positive spill-over effects to the EU at large, beyond the participating Member States and companies; and involves co-financing by companies that receive state aid. However, key differences with the proposed Fund are that the IPCEIs do not receive funding from central resources and that there is no eligibility condition based on adherence to the SGP rules.[4]

6 How Large Should the Fund be?

The size of the Fund needs to be linked to what is needed in terms of investments with positive cross-border spill-overs and what is politically feasible. NextGenEU may give an indication regarding the latter.[5] On the one hand, NextGenEU was conceived during the corona crisis, which may have made it politically relatively more acceptable than the proposed Fund. On the other hand, while, through the grants it provides and because these grants are partially linked to how severely a country was affected by the pandemic and how prosperous it was relative to other EU countries, NextGenEU redistributes resources in a systematic way across countries, this does not need to be the case for our Fund, which should in turn make it easier to obtain support from the traditionally sceptical countries. The idea is that each country gets its own envelope in the total available resources in the Fund – the size of the envelope is linked to the size of the economy and financing of the Fund (through contributions or through the repayment of debt issuance) can be in the same proportion related to the size of the economy. Taking the climate-related public investment estimates by Pisani-Ferry, Tagliapietra, and Zachmann (2023) of 0.5–1 % of annual GDP and projected EU GDP of 19,350 billion euros in 2024 (IMF 2024) yields an annual climate-related investment need of 100–200 billion. Because a reduction in greenhouse gases is a non-rival public good, a large fraction of this amount should be eligible for the Fund. Of course, there are other non-climate-related investments, such as those in the digital transition, that fall under the scope of the Fund. Overall, for political feasibility, on an annual basis the size of the Fund would be on the order of magnitude of NextGenEU. However, the latter runs for a more limited amount of time. If there is an only limited political support for the Fund, it could also be started on a smaller scale and be expanded after demonstrated success. One could also envisage starting with a coalition of willing countries only.

7 How is the Fund to be Governed and Financed?

The Fund would explicitly not be part of the EU budget, but rather be standalone. Incorporating the Fund into the EU budget would imply an increase in the EU budget, assuming that other EU expenditures are not one-for-one reduced. Such an increase in the EU budget could easily be seen as a new “status-quo” point, implying that it is perceived to be difficult to reduce the budget again, once the envisaged investments with cross-border spill-overs are no longer needed, because the digital and green transitions have been completed. By contrast, a standalone fund would cease to exist once it has been depleted or a set expiration date has passed.

The eligibility of a proposed project could be assessed by the European Investment Bank (EIB) or some other independent assessor at the EU-level. The institution doing the independent assessment should in any case have specific expertise with the (financial) assessment of large investment projects. It makes a cost-benefit analysis from the perspective of the EU as a whole. Projects are eligible for funding only if their aggregate financial benefit at EU level exceeds its total cost. In addition, if a country submits a plan on its own, the assessor assesses the size of the cross-border benefits in relation to the investment outlay. When two or more countries submit a plan, it assesses to what extent the overall benefit exceeds the sum of the benefits of all countries involved, if each country would merely do its part of the investment on its own. Based on its assessment, the assessor formulates an advice as to whether the project should be funded. If the advice is positive, the European Commission formulates a funding proposal for the Ecofin. For incentive-compatibility reasons it would be desirable for the assessor to have skin in the game by taking a stake in the project. This would make the EIB the preferred assessor.

The conditions for the investment proposal can be similar to those for that qualify for the IPCEI. Importantly, any proposal should be concrete and focussed on the economic benefits it generates for the investing countries and more broadly the EU. This is not to say that other benefits may not be important. The reason for this requirement is to avoid that the criteria become fuzzy and projects get accepted that do not generate sufficient economic benefits.

An investment project can be financed in different ways. The most plausible arrangement would follow that of NextGenEU, i.e. by issuing EU public debt. Since the benefits of the investments materialise in the future and accrue mostly to the younger cohorts, it seems reasonable that they would be liable for repaying at least part of the debt. Repayment could take place through earmarked contributions by the Member States or through own resources of the EU, for example, as proposed by the European Commission (2021b), revenues from the EU emissions trading system, the EU carbon border adjustment mechanism and sharing in the tax revenues from the largest multinationals. As a beneficial by-product, the Fund can be an instrument for deepening the market for EU debt. This is important as debt issuance volumes are relatively small.[6]

The EU debt-financing in the context the Fund should not be used as a way to escape the EU requirement to bring debt on a downward path if it exceeds the SGP’s 60 % of GDP reference value. That is, domestically-oriented public investment spending should not be shifted to the Fund. Monitoring could be done by the European Commission, possibly with input from the European Fiscal Board.

8 Why Would the Fund be Politically Attractive?

Currently, the political appetite for a new EU fund is likely quite low, at least among the countries that are traditionally sceptical about any centralisation of fiscal powers in the EU. Some countries agreed to NextGenEU assuming that this would be a once-and-for-all fund. The biggest obstacle to any follow-up fund would be the perceived redistribution among countries, with some countries fearing that they would become net payers. However, within the Fund each country has its own envelope, hence redistribution can be avoided. Moreover, the Fund incentivises investments with cross-border spill-overs.

How can such an arrangement not be politically attractive, and how can its attractiveness be improved? There exist some possible reasons why the Fund may not be politically attractive. First, countries may not be able to adhere to the EU fiscal rules or lack proper investment proposals and, hence, would not be able to make use of the Fund, even though they would eventually contribute to its financing. Second, countries may have governments for which the short-run costs of the investments outweigh their perceived benefits, because they believe the benefits are too uncertain or because the benefits materialise too far in the future relative to their own horizon. A possibility to deal with this objection is to finance the outlays of the Fund with the issuance of debt with a sufficiently-long maturity or to even postpone the debt-servicing costs for a sufficient number of years, so that current governments will not be confronted with these costs during their tenures. Third, countries may fear that the conditions attached to receiving funding will not be applied as strictly as proclaimed and, hence, they have limited confidence in its proper operation. Here, there exists an important role for the European Commission in critically assessing the proposed projects against the milestones that have been set in advance. For this, the Commission can draw on its experience with the RRF. However, as pointed out by Darvas, Welslau, and Zettelmeyer (2023) and Demertzis, Pinkus, and Ruer (2024), the “milestones and targets” envisaged by the RRF are measures of progress towards results rather than of achievement of the results themselves. More focus on the eventual results would be needed. On the other side of the political balance is the opportunity for the Fund to strengthen European strategic autonomy, a feature that resonates with right-wing populist parties, which tend to be sceptical about European projects.

9 Concluding Remarks

In the coming decade, the EU needs to invest heavily in the digital and green transitions. These investments may be large, in particular when it comes to infrastructure investments, and they generally have cross-border beneficial spill-overs, leading individual investing countries to insufficiently internalise the benefits of those investments. So, how to get these investments off the ground? In this article, following earlier proposals by Bakker, Beetsma, and Buti (2024a, 2024b), we propose an EU-wide fund in which each country gets an envelope for public investments with cross-border spill-overs. Countries can make use of their envelope if they come up with proper investment plans and adhere to the EU fiscal rules, while (the remainder of) their envelope is distributed across the other envelopes if they do not fulfil these conditions. Eligible investment plans, addressing common EU priorities, should also be a relevant factor in the decision to decide about an extension of fiscal-structural plans from four to seven years, if so requested. The Fund should be able to overcome political scepticism and provide proper incentives both for the type of proposed investment and fiscal discipline. However, to make it work there is a crucial role for the European Commission and Council to ensure proper implementation.

It may be important to point out that realising investments with an EPG character is not only about making available sufficient financial resources. It is also a matter of adequate coordination of national investment activities. An example is the lack of capacity of national electricity grids, already existent in some EU countries and looming in other countries. Several employer organisations urge the Commission to take on a larger role in the coordination of the expansion investments in the national grids (Het Financieele Dagblad 2024b).

References

Bakker, A., and R. Beetsma. 2023. “EU-Wide Investment Conditional on Adherence to Fiscal-Structural Plans.” 3 November 2023. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/eu-wide-investment-conditional-adherence-fiscal-structural-plans.Search in Google Scholar

Bakker, A., R. Beetsma, and M. Buti. 2024a. “The Case for a European Public-Goods Fund.” Project Syndicate, 4 March. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/public-goods-fund-could-finance-green-transition-and-ensure-fiscal-responsibility-by-age-bakker-et-al-2024-03.Search in Google Scholar

Bakker, A., R. Beetsma, and M. Buti. 2024b. “Two Birds with One Stone: Investing in European Public Goods While Maintaining Fiscal Discipline at Home.” Intereconomics 59 (2): 1–6.10.2478/ie-2024-0021Search in Google Scholar

Blanchard, O. J. 2023. “Reconciling the Tension Between Green Spending and Debt Sustainability.” Blog, December 19. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/reconciling-tension-between-green-spending-and-debt-sustainability.Search in Google Scholar

Buti, M., A. Coloccia, and M. Messori. 2023. “European Public Goods.” VoxEU, 9 June.10.11647/obp.0386.11Search in Google Scholar

Darvas, Z., L. Welslau, and J. Zettelmeyer. 2023. “The EU Recovery and Resilience Facility Falls Short against Performance-Based Funding Standards.” Analysis, 6 April. https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/eu-recovery-and-resilience-facility-falls-short-against-performance-based-funding.Search in Google Scholar

Demertzis, M., D. Pinkus, and N. Ruer. 2024. “Accelerating Strategic Investment in the European Union Beyond 2026.” Bruegel Report, Issue no. 01/24, January.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2020. “Stepping up Europe’s 2030 Climate Ambition – Investing in a Climate Neutral Future for the Benefit of Our People.” Commission Staff Working Document (2020) 176 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:749e04bb-f8c5-11ea-991b-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2021a. “State Aid: Commission Adopts Revised State Aid Rules on Important Projects of Common European Interest.” Press Release, November 25. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_6245.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2021b. “The Next Generation of Own Resources for the EU Budget.” COM(2021) 566 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0566.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2024. “Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI).” https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/state-aid/ipcei_en.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2023. “Debt Sustainability Monitor 2022.” Institutional Paper 199, April.Search in Google Scholar

European Fiscal Board. 2023. Annual Report 2023. Brussels: European Commission.Search in Google Scholar

Fuest, C., and J. Pisani-Ferry. 2019. “A Primer on Developing European Public Goods.” ZBW ECONSTOR, EconPol Policy Report, No. 16. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/219519/1/econpol-pol-report-16.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Garicano, L. 2022. “Combining Environmental and Fiscal Sustainability: A New Climate Facility, an Expenditure Rule, and an Independent Fiscal Agency.” VoxEU, 14 January 2022.Search in Google Scholar

Heinemann, F. 2018. “Going for the Wallet? Rule-of-Law Conditionality in the Next EU Multiannual Financial Framework.” Intereconomics 53 (6): 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-018-0771-2.Search in Google Scholar

Het Financieele Dagblad. 2024a. Kampioen groene stroom Denemarken zet extra vaart achter energietransitie, March 16.Search in Google Scholar

Het Financieele Dagblad. 2024b. In heel Europa lopen bedrijven tegen volle stroomnetten aan, March 18.Search in Google Scholar

IMF. 2024. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/EU.Search in Google Scholar

Pisani-Ferry, J., S. Tagliapietra, and G. Zachmann. 2023. “A New Governance Framework to Safeguard the European Green Deal.” Bruegel Policy Brief, Issue no 8/23.Search in Google Scholar

WIIW. 2023. Rail Instead of Lorries: The Climate Effect of a ‘European Silk Road’, September 20. https://wiiw.ac.at/rail-instead-of-lorries-the-climate-effect-of-a-european-silk-road-n-606.html.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Economic Policy Making Under Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- A Latticework of Inflation Models

- A Comparative Evaluation of Fiscal Stabilization Strategies during the Covid-19 Pandemic with Germany as a Reference Point

- The Relationship Between the German Current Account and Financial Account: Evidence from the Toda-Yamamoto Causality Approach

- The Tax Attractiveness of EU Locations for Corporate Investments: A Stocktaking of Past Developments and Recent Reforms

- Aid in Conflict: Determinants of International Aid Allocation to Ukraine During the 2022 Russian Invasion

- Policy Forum: Economic Policy in an Era of Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Public Debt Ratios Will Increase For Some Time. We Must Make Sure That They Do Not Explode

- An EU Fund to Incentivise Public Investments with Positive Externalities

- The Case for Putting a Public Investment Clause into the German Debt Brake

- EU Debt Instruments and Fiscal Transparency: The Case of the EU Recovery Fund

- Explaining the Divergence in German and French Public Finances

- Fiscal Prospects for Italy

- The Swiss Debt Brake Is Democratic, Strict, Transparent, and Binding. A Model to Follow?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Economic Policy Making Under Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- A Latticework of Inflation Models

- A Comparative Evaluation of Fiscal Stabilization Strategies during the Covid-19 Pandemic with Germany as a Reference Point

- The Relationship Between the German Current Account and Financial Account: Evidence from the Toda-Yamamoto Causality Approach

- The Tax Attractiveness of EU Locations for Corporate Investments: A Stocktaking of Past Developments and Recent Reforms

- Aid in Conflict: Determinants of International Aid Allocation to Ukraine During the 2022 Russian Invasion

- Policy Forum: Economic Policy in an Era of Hardening Fiscal Constraints

- Public Debt Ratios Will Increase For Some Time. We Must Make Sure That They Do Not Explode

- An EU Fund to Incentivise Public Investments with Positive Externalities

- The Case for Putting a Public Investment Clause into the German Debt Brake

- EU Debt Instruments and Fiscal Transparency: The Case of the EU Recovery Fund

- Explaining the Divergence in German and French Public Finances

- Fiscal Prospects for Italy

- The Swiss Debt Brake Is Democratic, Strict, Transparent, and Binding. A Model to Follow?