Abstract

The development of contemporary Semarang batik as an expression of personal expression free from the boundaries of traditional rules is feared to threaten the existence of traditional batik. For this reason, we studied aesthetic hybridization as an approach to creating contemporary batik designs in Semarang. The research uses a qualitative approach with case study methods through observation techniques, interviews, and document studies to explore contemporary batik motifs by batik artisans in Semarang. The validity of the data was determined by triangulation of data sources and focus group discussions, which were analyzed in a descriptive-multidisciplinary manner with theories of culture, art, and creativity. The results of the study are as follows: (1) the creative exploration process of batik artisans in Semarang is carried out through the application of the concept of aesthetic hybridization that combines coastal and inland styles that produce the design of contemporary Semarang batik motifs; (2) the embodiment of Semarang batik works combines elements of traditional art identity and creative innovation based on personal expression that combines exclusive and egalitarian characteristics through aesthetic hybridization to form a new identity. This research contributes to artisans and entrepreneurs developing contemporary batik based on traditional batik aesthetic hybridization to form a new identity.

1 Introduction

The existence of Indonesian batik as an identity and cultural heritage needs to be preserved and developed. However, the author has identified two main problems in the field of batik, namely, the problem of safeguarding traditional batik and the development of contemporary batik. Several challenges hinder efforts to preserve batik, including limited public awareness of its meaning and philosophy (Fadly & Pramudita, 2024), the problem of the authenticity of traditional batik art with the emergence of printed batik technology that disrupts the market and affects consumer confidence (Putra et al., 2021), and the entry of foreign cultures raises tensions between efforts to preserve traditional batik making techniques and the adoption of modern technology to improve design quality and production efficiency (Lestari et al., 2018; Minarno et al., 2024; Sari et al., 2018; Supriyadi & Prameswari, 2022). Meanwhile, the problems faced in batik development efforts include adaptability and market changes, limited access to credit, financial literacy and digital marketing strategies that hinder production and distribution (Al-Shami et al., 2024; Bakri et al., 2018); environmental and water resource pollution management and green industry standard adoption capability (Amalia et al., 2020; Kusumawardani & Kurnani, 2021; Kusumawati et al., 2020); use and integration of advanced technologies such as IoT, AR, and CAD/CAM to improve the production and promotion of batik as a cultural heritage (Bakri et al., 2018; Rahmat et al., 2024; Syed Shaharuddin et al., 2021). Considering the complexity of problems in the preservation and development of batik, ranging from the lack of philosophy awareness, challenges to the authenticity of traditional techniques, penetration of foreign cultures, to the demands of technological adaptation and global markets, it is seen as necessary to have the right approach in the process of creating contemporary batik motif designs, namely, an aesthetic hybridization approach as an integrative strategy that can bridge traditional values with innovation in harmony and sustainability.

The hybridization strategy combines two different batik cultures to produce innovations without eliminating the typical traditional elements. The coastal and inland mix is a unique and distinctive dichotomy of batik culture. The growth of batik along the northern coast of Java is growing rapidly because it is helped by the area’s proximity to trading ports and port access (Rojak, 2023). Currently, batik is developing in several places along the coast of Central Java, such as Lasem, Pekalongan, and Semarang (Maulany & Masruroh, 2017; Rahayu & Alrianingrum, 2014; Salma, 2013; Syakir et al., 2022). Batik culture in Semarang City, as one of the batik-producing areas in the coastal style, is open to receiving significant foreign influences, with the implication that strict rules do not bind the development of batik. This condition differs from inland batik, which is subject to strict traditional rules and has high philosophical values (Dwiyanto & Nugrahani, 2002). The difference between coastal and inland batik lies in the location of the region and the ability to process the influence of outside culture; coastal batik occupies areas along the north coast of Java Island, which displays an independent and adaptive nature to foreign influences, while inland batik occupies areas close to the tradition of the palace. Hence, it is conservative and complex to accept changes from the outside (Yuliati, 2010). Based on the exploration of the resulting motives, coastal batik motifs have a variety of shapes, like Semarang batik, while inland batik motifs show more consistent repetitive shapes.

Recent studies on aesthetic hybridization practices have been widely conducted in arts, design, and crafts. In the discipline of fine arts, this practice is carried out by integrating traditional artistic methods with the adaptation of technology and other sciences (Gal, 2023; Trach et al., 2023). In the design discipline, the concept of aesthetic hybridization is found in architectural art and in the field of fashion design that integrates nature, technology, art, geography, aesthetics, and the environment in a single synthetic unit (Beneš, 2022; Huang & Jin, 2024); design art combines art and product design in creating aesthetic and functional works (Di Stefano, 2016). In the discipline of crafts, hybridization has been found in making traditional crafts, combining digital fabrication with modern tools and techniques to innovate and revitalize sustainable traditional crafts (Bernabei & Power, 2018; Liu et al., 2024; Zoran, 2013).

Applying aesthetic hybridization concepts and practices in contemporary batik motif design innovation is the ability to integrate various elements in the creation process. The aspects of integration in question, in between: the integration between the source of ideas and the technique of creation (Guntur et al., 2023), integration of Batik motifs of tradition and contemporary culture (Budi et al., 2024; Rismantojo et al., 2024), aesthetic and cultural integration (Luo et al., 2024; Reis, 2011; Sun, 2023), and traditional to modern adaptations (Parhusip et al., 2023). To have this ability, a batik designer or craftsman must be creative in processing and integrating several elements into contemporary batik works. For example, the combination of traditional and modern elements not only combines the values of a nation’s cultural traditions but can also combine traditional motifs between nations, such as Tiga Negeri batik motifs combined with modern digital printing technology and pleated techniques into contemporary designs (Rismantojo et al., 2024). In addition to being skilled at combining traditional elements, designing contemporary batik designs also requires integrating symbolic, ethical, and philosophical values into the design to reflect the ethical values and adaptation of contemporary design (Sachari et al., 2020).

When seen in its characteristics, the visualization of Semarang batik motifs as coastal batik reflects an open, free, and spontaneous society (Triyanto, 2018). At the beginning of its development, the Semarang Batik motif, influenced by the Dutch and Chinese, did not reflect its characteristics. However, after the recognition of UNESCO, the form of Semarang Batik motifs metamorphosed from traditional to contemporary motifs through innovation to produce batik motif designs in the form of city icons in the form of architectural buildings (Tugu Muda, Blenduk Church, Marabunta Building), leaf motifs (Blekok Srondol), Semarang culture (Wewe Gombel, Warak Ngendok), and culinary types (Lumpia, Tahu Gimbal), as well as tourist sites and tipogafi motifs (Hananto et al., 2018; Suliyati & Yuliati, 2019). The characteristics of Semarang Batik can be seen from the bright and striking colors and the motifs that are free or not bound by specific rules, influenced by Chinese culture, especially with its mythological elements (Yuliati & Susilowati, 2022). In addition to having similarities in the characteristics of Semarang Batik motifs with batik from other northern coastal areas of Java, there are also differences in the basic colors of Semarang Batik which are bright colors such as orange and red, light brown Demak batik, and Kudus Batik with blue base (Afreliyanti, 2015; Rens & Veldhuisen, 1996).

Various studies on aesthetic hybridization have been presented in the study of art, design, and craft. However, the study of art in the context of creating coastal and inland-style batik motif designs has not been widely studied. The batik industry in Java has transformed from a traditional craft to a modern economic venture, especially since the nineteenth century with innovations such as stamping methods and chemical dyes. Batik is a cultural artifact and a product that develops in the context of capitalism, globalization, and international market competition. It continues to evolve through a dialogue between local heritage and global influences (Sekimoto, 2016). This perspective is further substantiated by Wronska-Friend (2019) that batik as a technique of fabric decoration with canting and hot nights has reached the highest complexity in the Javanese tradition, serving as an intermediary between Indonesian culture and other countries influenced by local values, aesthetics, technology, and market dynamics and commercial profitability globally, as well as offering expressive flexibility that encourages innovation and cross-cultural personal expression. For this void, the author examines the aesthetic hybridization of coastal and inland batik motif styles by studying creative exploration in designing contemporary batik motifs in Semarang. This research aims to:

Analyze how the creative exploration of batik artisans in Semarang through aesthetic hybridization (coastal and inland styles) creates contemporary Semarang batik motifs.

Analyze the visualization and embodiment of Semarang batik motifs resulting from creative exploration through aesthetic hybridization (coastal and inland styles).

The novelty of this study is the theoretical findings of the contemporary cultural phenomenon of batik in Semarang through aesthetic hybridization efforts in strict inland batik motifs with the tradition of the palace and the egalitarian Batik culture of Semarang (coastal). The urgency of this research lies in its potential to revitalize the batik industry in Semarang, ensuring the sustainability of this cultural heritage while encouraging economic growth. The novelty of this research is its approach to combining different aesthetic traditions to create innovative batik designs that maintain artistic integrity while appealing to contemporary aesthetics.

2 Methods

2.1 Research Approach and Design

The qualitative descriptive approach has the advantage of explaining research phenomena (Leedy & Ormrod, 2016), so it is suitable for this research, which seeks to uncover the phenomenon of creative exploration of Semarang batik artisans in creating contemporary batik motifs through aesthetic hybridization of Inland and coastal batik styles. Exploring contemporary batik motifs in Semarang is seen as a case; thus, a case study was chosen as a research design (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2003).

2.2 Research Subjects and Objectives

The subject of this research is an exploration of contemporary Semarang batik motifs by batik artisans in Semarang. The research targets three batikan areas in Semarang: Meteseh Tembalang, Gunung Pati, and Bubakan Batik Village Semarang.

2.3 Data Collection Techniques

Data collection in this study was carried out through observation techniques, interviews, and document studies. The observation technique is directed to obtain related data: profiles of artisans, themes, media, processes, and elements of coastal and inland batik as ideas that are processed into contemporary Semarang batik motifs, product identities, and product patterns. Observation is assisted by recording aids in the form of cameras, audio-visual recordings, notebooks, and drawing paper. The interview technique was carried out to obtain data from several sources regarding the profile of the craftsman, ideas, media, process, artistic manifestation of the work, identity, and characteristics of the batik motifs created. The document study was carried out to obtain biodata or profiles of artisans, identity and characteristics, and pattern of batik motif products created. The following is presented in the form of a data collection guideline table.

2.4 Data Validity

For the validity of aesthetic hybridization research data (coastal and inland style), a study exploring contemporary Semarang batik motifs was carried out through the data source triangulation technique. This means that data obtained through observation, interview, and document study techniques are compared to find the level of trust in the data that has been collected. In addition, to strengthen data triangulation, it is also pursued through focus group discussions (Gundumogula & Gundumogula, 2020; Mishra, 2016) with colleagues and a number of experts.

2.5 Data Analysis

The data in the study is art data (contemporary Semarang batik motifs), categorized into two types: intra-aesthetic and extra-aesthetic (Adams, 1996; Rohidi, 2011, p. 75). Intra-aesthetics deals with the expression of art, media, techniques, and ideas, while extra-aesthetics encompasses social, environmental, individual, and cultural. Intra-aesthetic theory is used by the author in explaining and discussing the works of batik motifs textually, while extra- aesthetics are used in discussing artworks contextually, which underlies the creation of Semarang batik motif designs. A number of theories will reveal the phenomenon of art data such as the theory of creativity (Al-Ababneh, 2020). The theory of creativity used to discuss the results of the research uses the four stages of creative thinking proposed by Helmholtz and Graham Wallas, namely, the stages of preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification as a psychological framework and mental process in generating new ideas (Wallas, 2015). The theory of cultural hybridization as a new mixture resulting from local and global cultures through the process of hybridization (Canclini, 1995; Dwiyanto & Nugrahani, 2002). Hybridization is the process of mixing between different cultures that results in new forms, new meanings, new identities, and new cultural practices. Data collection involves some techniques with tools and cross-checking data involving some experts through the Focus Group Discussion method (FGD).

3 Research Findings and Discussion

3.1 The Creative Exploration of Batik Artisans in Semarang through an Aesthetic Hybridization

In this section, the results of research and discussion will be presented to answer the first research objective, namely, the creative exploration of batik artisans in Semarang through aesthetic hybridization. In the context of batik motif design, creative exploration entails seeking innovative ideas and visual forms while remaining rooted in local values and wisdom. This process involves an in-depth observation of cultural elements, the surrounding environment, and contemporary aesthetic developments, which are then processed into original and meaningful motifs. In this process, batik designers produce existing motifs and patterns and create new interpretations of visual dyeing techniques and dynamic compositions. The result is a batik motif that incorporates engineering and traditional textile art and presents a cultural identity that is dynamic and relevant to the development of the times.

The emergence of batik in Semarang was possible since the Dutch colonial era in Indonesia through a number of immigrant actors, only handled by people of Semarang in the twentieth century (Afreliyanti, 2015). Since its existence has been questioned, Semarang batik has begun to grow and has been committed to its existence as part of the culture in Semarang since 2005 (Asikin, 2008). Through the role of the government and the community, Semarang batik began to grow and develop, which can be grouped into three central areas for batik artisans: Bubakan, Meteseh, and Gunungpati (Syakir, 2017). As a culture with coastal characteristics, batik in the three regions processes the characteristics of Semarang’s motif culture, which is egalitarian and open to change. The motifs that became Semarang’s cultural identity continue to be maintained until now, namely, motifs developed from cultural identities in Semarang such as Asem, Lawang Sewu, and Tugu Muda. Through interaction with batik culture from outside Semarang, the existing batik motifs have changed by crossing the different characteristics of batik culture, namely, coastal and inland cultures.

Semarang’s contemporary batik motifs are composed of elements of Inland and Coastal batik motifs. Combining these two motif elements is an effort to hybridize two different batik cultural identities. Inland batik motifs developed in the Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Kraton) areas. The culture of making inland batik motifs has a strict rule structure. In the Inland batik culture, creating batik motifs must be subject to standard rules that have been determined or agreed upon, especially regarding the arrangement of motif patterns. Inland batik has measurable patterns, its shape is full of symbols, and it has not undergone changes. This shows the superiority of the palace culture. The coastal batik motif is developed outside the palace (Yogyakarta and Surakarta) or in coastal areas heavily influenced by foreign cultures. The batik motif shows a free expression and is open to outside cultural influences. Batik with coastal cultural characteristics reveals that the visualization of batik motifs tends to be free, not bound by rules, egalitarian, and open to changes.

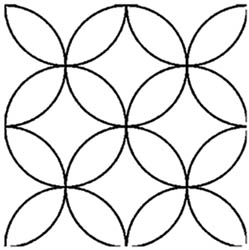

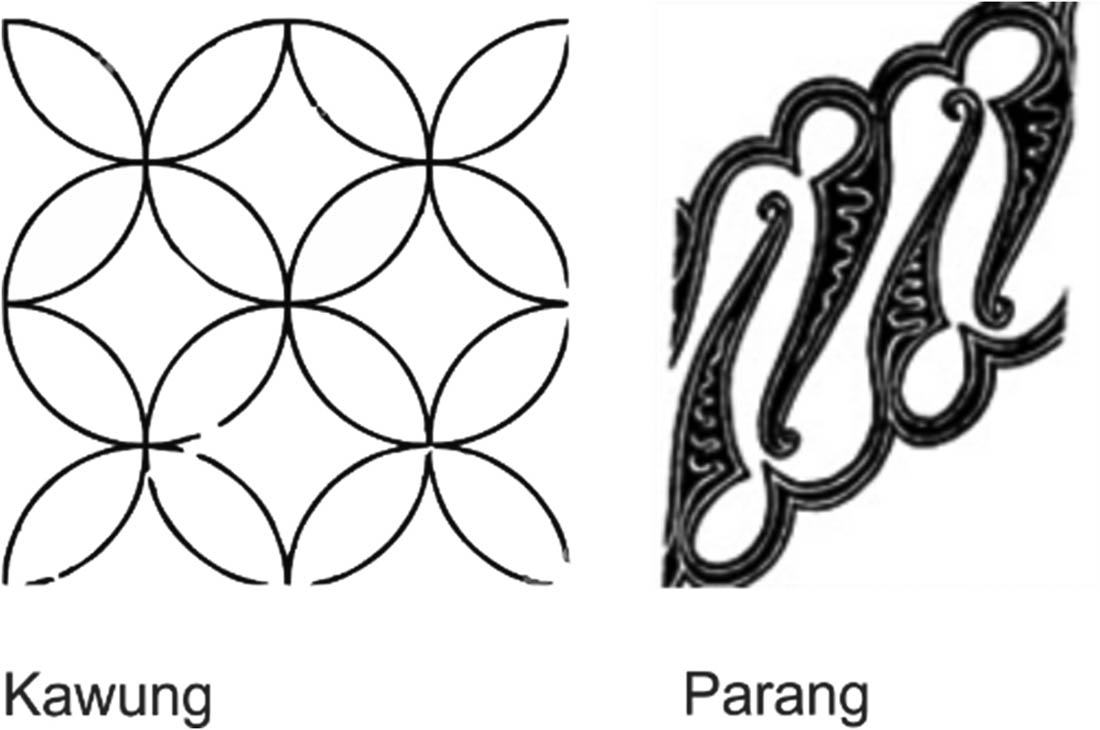

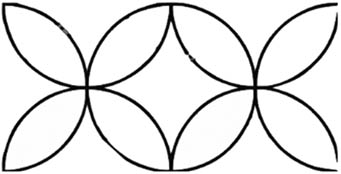

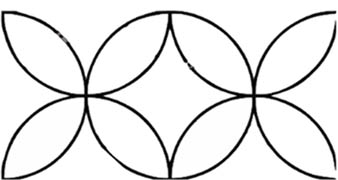

The visualization of batik motifs is composed of shapes and patterns. There are different shapes and patterns between Inland and coastal batik cultures. The shape of the inland batik motif developed in Semarang is generally geometrically symbolic, such as in the Parang and Kawung batik motifs.

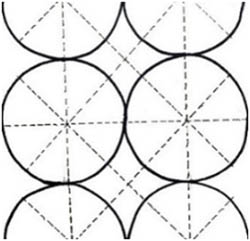

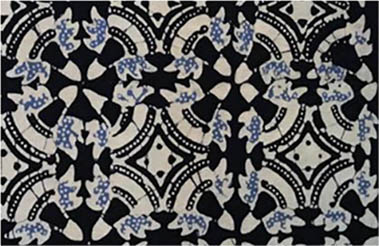

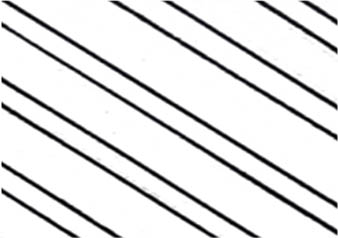

Table 1 illustrates the inland batik pattern that Semarang batik artisans widely use. The patterns of batik motifs include the following patterns: Kawung, Jlamprang, Lereng, and Sekar Jagad. Visually, the Kawung, Jlamprang, and Parang batik patterns tend to be classified as geometric batik motifs, while the Sekar Jagad batik pattern belongs to a non-geometric group. The form of geometric motif patterns is usually orderly with symmetrical balance, such as in Kawung motifs, which have a full repetition pattern.

Characteristics of inland batik patterns

| No. | Pattern name | Pattern | Pattern characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kawung |

|

|

| 2 | Jlamprang |

|

|

| 3 | Lereng |

|

|

| 4 | Sekar Jagad |

|

|

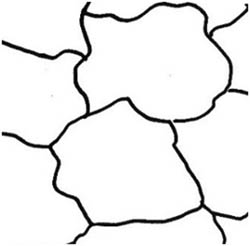

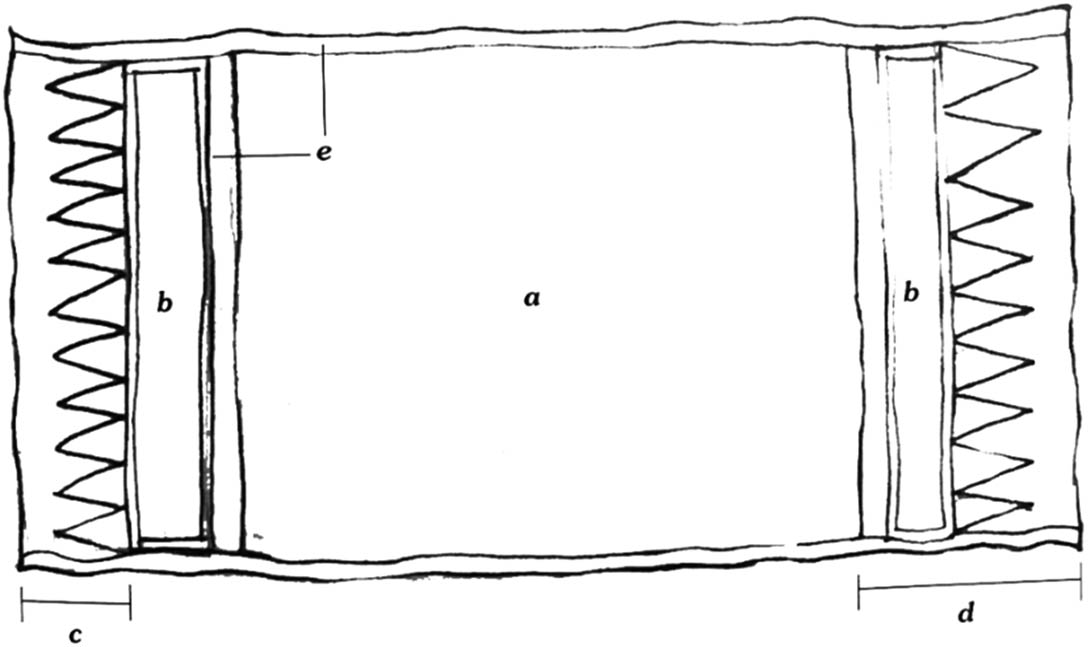

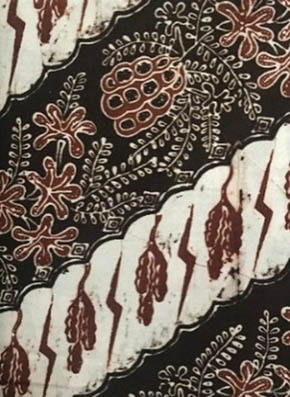

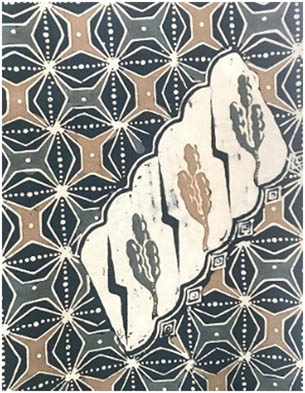

Figure 1 visualizes two patterns of inland motifs: the Kawung and Parang. The Parang batik pattern is composed of an orderly pattern of repetition of motifs with a full repeat composition with one step to the side or up to meet the batik fabric. Meanwhile, the machete pattern is obtained through specific repetitions to form an oblique plane to meet the cooled field of batik fabric. In contrast to the inland batik pattern, the coastal batik pattern, as shown in Figure 2, does not have a standard rule but has the characteristics of a tumpal and fringe pattern that is always presented in the batik visualization (Anas, 1997; Anshori & Kusrianto, 2011).

Inland batik motifs. Source: Author’s document, 2024.

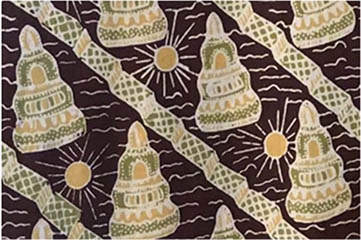

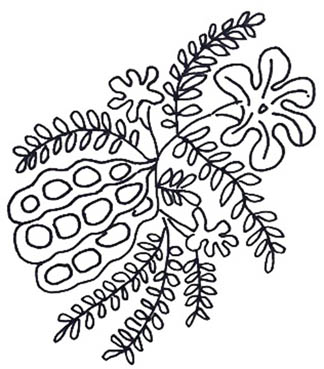

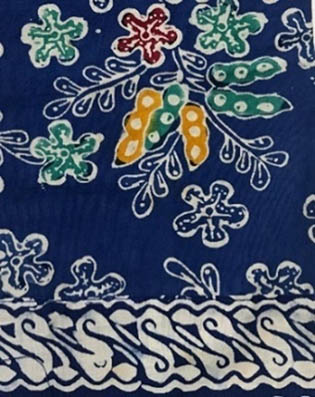

Characteristics of coastal batik patterns. Source: Author’s document, 2024.

The design of the coastal pattern batik motif in Figure 2 shows a typical structure consisting of a body (a) as the main element with ample space for the main motif, which usually contains flora, fauna, or abstract patterns typical of the coast. The plank element (b) on both sides serves as a barrier that provides a visual transition between the body and the head (d), which generally has more complex and striking motifs. The tumpal (c) on the edges features a repeating triangular pattern, symbolizing strength and protection. At the same time, the fringe (d) plays a role in clarifying the boundaries of the design to make it more structured. This coastal batik motif reflects foreign culture’s freedom of expression and influence due to the interaction of coastal communities with foreign traders, resulting in a more dynamic and varied design than inland batik. Overall, this design represents coastal batik’s characteristics, which are colorful and bold in motifs and still contain deep philosophical meaning.

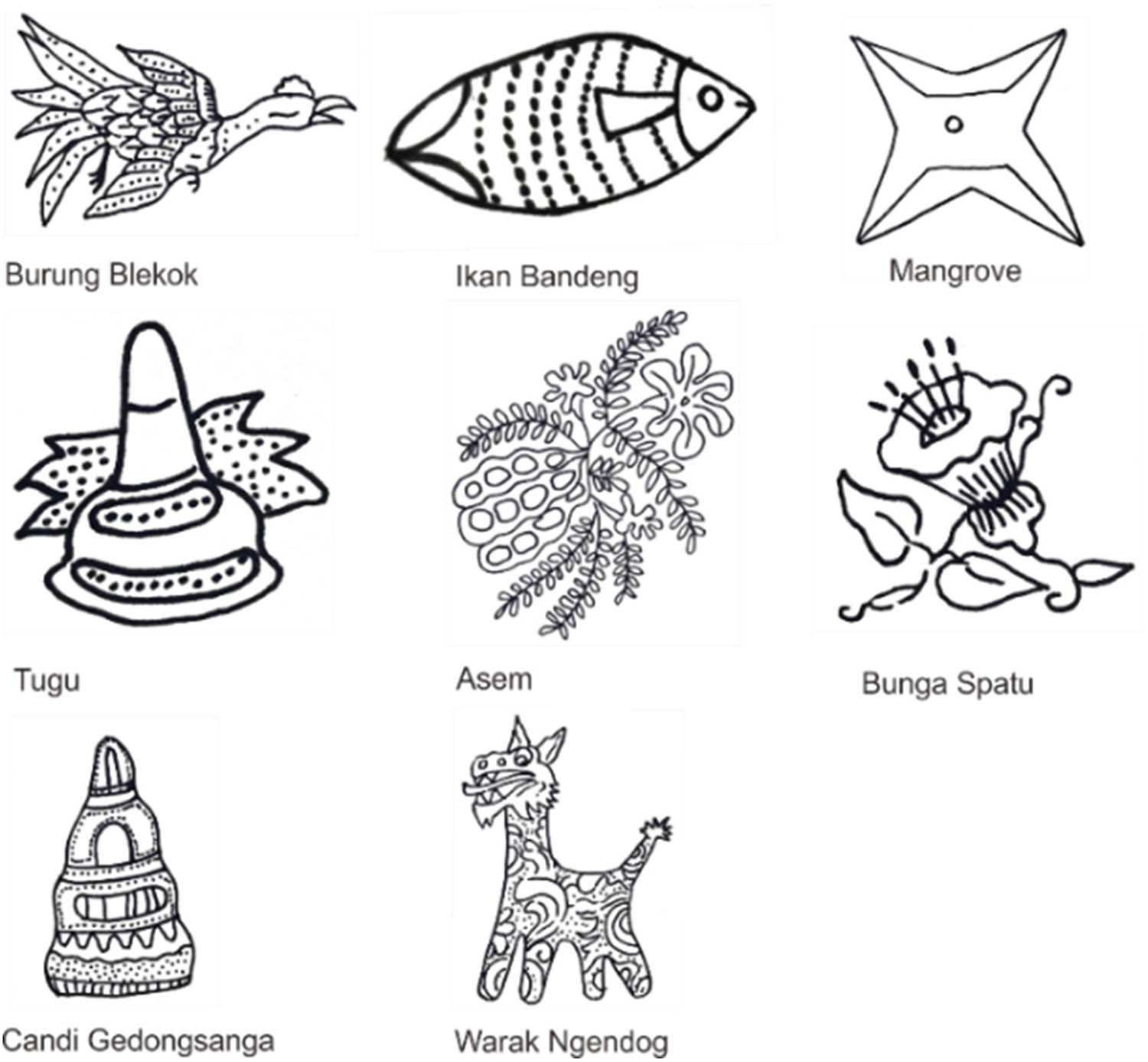

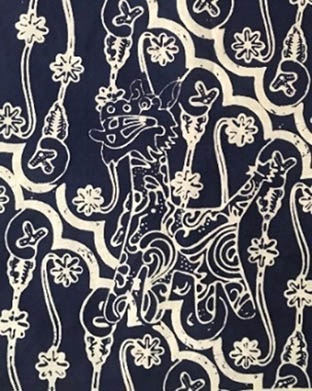

Figure 3 shows various distinctive elements representing Semarang’s cultural and environmental identity. The motifs of blekok (cranes), milkfish, and mangroves reflect the richness of coastal ecosystems closely related to the lives of local communities that depend on fisheries and environmental conservation, which have a denotative meaning. The visualization of the Gedongsongo Monument and Temple illustrates the historical value and cultural heritage that is the pride of the region. Hibiscus and sour leaf motifs represent local flora with aesthetic value and ecological benefits. Meanwhile, the Warak Ngendog motif represents a typical Semarang icon closely related to the Dugderan tradition, symbolizing the harmonious cultural acculturation between Javanese, Chinese, and Arab ethnicities. Overall, this image features a combination of natural, historical, and cultural elements that can be inspired by the design of typical coastal batik motifs with a strong local identity.

Coastal motifs. Source: Author’s document, 2024.

The difference in batik motifs in the three Semarang batik centers is influenced by nature, the social and cultural of the supporting community, and the creativity of designers/craftsmen in creating batik designs. In general, the process of creating batik motifs in three Semarang batik centers has been carried out by craftsmen/designers in stages, starting from preparation, contemplation, tightening, and assessment of design results. This condition aligns with the four psychological frameworks and mental processes to generate new ideas, such as those offered by Helmholtz and Graham Wallas, namely, the stages of preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification (Wallas, 2015). Based on this theory, the process of creating batik motif designs that craftsmen have carried out is presented in detail in Table 2.

Process of exploring the creativity of making contemporary batik motifs in Semarang

| Preparation stage | Incubation stage | Illumination stage | Actualization stage |

|---|---|---|---|

Initial data collection and exploration activities:

|

The process of unconscious reflection without explicit activity:

|

The emergence of original ideas or design inspirations:

|

Testing and refining ideas into concrete works:

|

Table 2 shows the creative process in creating Semarang batik motif designs. In the Preparation stage, the designer conducts data collection and initial exploration, several activities are carried out at this stage: visual and philosophical study of inland and coastal batik ornaments, documentation and object photography process, interviews with cultural experts/artisans, recording of initial ideas and inspiration. The Incubation stage, a process of unconscious reflection without explicit activities, includes taking a break from design activities, reflecting on aesthetic and philosophical values from cultural sources of inspiration, and internalizing traditional cultural values. The Illumination stage, at this stage, original ideas or design inspiration emerge through the process of conceptualizing visual ideas for batik motifs, realizing ideas through sketches, arranging objects to form batik motif patterns decoratively and intuitively, and refining the design and pattern of batik motifs. Actualization Stage, at this stage testing and refining ideas into concrete works, including revision and finalization of design sketches, adjustment of composition and harmonization of forms, visual evaluation and meaning of works, and testing of motifs and designs of batik patterns by experts/society/consumers.

At the beginning of the emergence of Semarang batik motifs, it was difficult to find its identity because Semarang batik was initially initiated by a number of foreign actors from China and the Netherlands (Suliyati & Yuliati, 2019). Now, the identity of Semarang batik can be recognized through a long struggle by Semarang batik artisans who can explore the source of ideas. The ability to examine the potential for Semarang’s local culture as an idea or idea in creating batik motifs makes Semarang batik motifs very exploratory (Suliyati & Yuliati, 2019; Syakir et al., 2022; Syakir, 2017). Batik motifs or batik ornamental motifs are the main thoughts and basic forms in the realization of ornaments or ornamental variety, which include all of God’s creations (animals, plants, humans, mountains, water, clouds, stones, and so on), imitations of objects and technology created by humans, and also the results of human creation or imagination (arrangement of lines and geometric shapes, as well as other imaginative creatures) (Syafii & Rohidi, 1987). Based on the description of the data above, it shows that the process of creative exploration carried out by craftsmen/designers is very important to create new motif designs that suit consumer preferences, without leaving the cultural value of the existing batik tradition. In overcoming economic problems and the textile industry, challenge is done by combining eco-friendly material innovations, local designs, digital marketing strategies, and community collaboration, allowing them to preserve cultural heritage while achieving sustainable growth (Octavia & Sriayudha, 2024). For these conditions, the artisans, through their creative ability, carry out an aesthetic hybridization process that combines the source of ideas and creation techniques (Guntur et al., 2023). The integration of traditional and contemporary batik motifs through the creation of new designs that resonate with modern aesthetics while preserving cultural heritage (Budi et al., 2024; Rismantojo et al., 2024) and the integration between aesthetics and culture shows the linkage between textile cultural heritage and digital, aesthetic, and ecological technologies for design innovation, preservation, and enhancement of its aesthetic and functional experience in the modern context (Luo et al., 2024; Reis, 2011; Sun, 2023). And the adaptation of traditional to contemporary in the creation of batik motifs can be seen from the use of modern geometric objects in batik motifs, combining mathematical precision with artistic creativity (Parhusip et al., 2023).

Based on the results of observations of contemporary batik designs in the research process, the author found that in the process of creative exploration through an aesthetic hybridization approach, in addition to the process of merging into new motifs, it is also possible to change the shape and meaning of the batik motif design that is created. This is strengthened by previous research on Semarang batik that the development of batik motifs is carried out by complicating the pattern of batik motifs, combining one shape with another into a new motif, changing the shape of the ornament, presenting new objects into the motif, and giving a special identity to the motif (Subekti et al., 2019). The findings are confirmed by the latest research in the case of Garuda batik motifs through syncretism from the Hindu period to the Islamic period, undergoing visual transformation and meaning (Banindro et al., 2024).

3.2 The Embodiment and Characteristics of Semarang Contemporary Batik Motifs through Aesthetic Hybridization

In this section, the results of research and discussion will be presented to answer the second research objective, namely, the embodiment and characteristics of contemporary Semarang batik motifs through aesthetic hybridization.

The embodiment and characteristics of Semarang Contemporary batik motif design as an artistic expression through an aesthetic hybridization approach is produced in practice combining various ideas, forms of motifs, media, and creation techniques carried out by designers and craftsmen. The transformation of the inland-style batik and coastal batik into contemporary batik. This effort is made to maintain traditional batik on the one hand and develop contemporary batik to meet consumer preferences on the other. The aesthetic hybridization approach aims to maintain traditional batik and develop it into contemporary batik so as to form a new identity. This practice can be found in the embodiment of batik motifs in three locations of Semarang batik centers located in Mateseh, Bubakan, and Gunungpati.

3.2.1 Visualization and Embodiment of Meteseh Batik Motifs

Table 3 visualizes exploring batik motifs through an aesthetic hybridization approach in Meteseh. The visualization of batik motifs in Mateseh combines inland and coastal motifs arranged in inland patterns. Intra-aesthetically, the idea of coastal motifs is sourced from Semarang’s natural and socio-cultural environment: milkfish, monuments, and temples. First, milkfish is a typical Semarang culinary dish expressed in motifs: composed with stylization, oval-shaped, full of dots, and dark red. Second, the monument is an iconic piece of Semarang architecture built during the Dutch colonial period. It is an expression in motifs: composed with stylization, filled in lines and dots, and a combination of dark blue and white colors. Third, the temple is a religious tourism building in Semarang, popularly known as Gedongsongo temple, an expression in the form of motifs: composed with stylization, complete with dots and lines, using green and yellow colors. The three motifs have white outline contours and isen-isen because the medium used is written batik with fabric, candles, and night.

Visualization and embodiment of Mateseh batik motifs through aesthetic hybridization approach

| Visualization and motif form | Aesthetic hybridization | |

|---|---|---|

| Inland motifs | Coastal motif | The embodiment of contemporary batik |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extra-aesthetically, the process of creating batik is related to individual, social, environmental, and cultural creativity. This is found in the patterns used to compose Mateseh motifs, namely, kawung and lereng, as an influence of inland batik culture. The kawung pattern is an overlapping circle shape arrangement, while the slope pattern is an oblique/diagonal parallel pattern (Sunaryo, 2009). Batik artisans in Meteseh are fond of inland arrangement patterns. The shape of the coastal batik motif, which is freely arranged in a strict interior pattern, eliminates the impression of coastal batik motifs. This is in line with the statement of Rini (Meteseh batik) that: “batik pedalaman telah kuat dalam ingatan masyarakat dengan ciri khas pola yang teratur, … pola batik pesisiran Semarang yang bebas dalam menyusun motifnya membuat masyarakat kurang bisa menerima … muncul ide untuk memadukan motif-motif batik Semarang yang khas dengan cara menyusun gaya pedalaman, sehingga ada kesan klasik pedalaman meskipun motifnya Semarangan.” (Inland batik has been strong in the community’s memory with the characteristic of organized patterns. The Semarang coastal batik pattern that is free in arranging its motifs makes the community less able to accept. The idea emerged to combine typical Semarang batik motifs by placing the interior style, so that there is a classic impression of the Inland, even though the motifs are Semarangan.)

3.2.2 Visualization and Embodiment of Bubakan Batik Motifs

Table 4 visualizes exploring batik motifs through an aesthetic hybridization approach in Bubakan. Intra-aesthetically, the visualization of batik motifs in Bubakan combines inland and coastal motifs arranged in coastal patterns. The idea of coastal motifs is sourced from Semarang’s natural and socio-cultural environment, namely, asem and warak ngendog. Asem is a plant that originates from the name of the city of Semarang, an expression in the form of motifs: composed with stylization, in the form of long sour fruits with flowers and leaves, full of dot filling, and using a choice of bright colors. In addition, Warak ngendog is a cultural icon of the city of Semarang. Warak ngendog is made to welcome the arrival of the month of Ramadan. The expression is in motifs: composed with stylization, filling in lines and dots, and appearing in blue. Both motifs have outlines and white isen-isen, which is characteristic of written batik media with fabric, candles, and night. The inland motif used is the parang barong motif shaped like a twisted keris (Sunaryo, 2009).

Visualization and embodiment of Bubakan batik motifs through aesthetic hybridization approach

| Visualization and motif form | Aesthetic hybridization | |

|---|---|---|

| Inland motifs | Coastal motif | The embodiment of contemporary batik |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extra-aesthetically, creating batik at this center is closely related to individual, social, environmental, and cultural creativity. This is found in the inner freestyle used to compose these motifs. Batik artisans in Bubakan freely combine inland and coastal batik patterns and motifs. Although there are inland batik motifs (machete motifs), the free way of arranging the motifs makes the design of batik motifs in Bubakan dominant with a coastal style. Artisans develop batik motifs that tend to be influenced by strong inland batik in preparation, excavation, illumination, and verification. This is in accordance with the following statement of Afifah (Bubakan batik craftsman): “… dalam menciptakan motif batik, kami para perajin sering menambahkan unsur-unsur batik pedalaman di bagian-bagian tertentu, … barang kali konsumen jenuh dengan batik-batik yang penuh dengan gaya pesisiran Semarang … sehingga para perajin terpikir untuk menambahakan unsur-unsur batik Surakarta atau Yogyakarta ke dalam batik Semarang yang kami buat.” (… in creating batik motifs, we craftsmen often add elements of inland batik in certain parts,. Consumers may be saturated with batik that is full of Semarang coastal style. so that the artisans thought of adding elements of Surakarta or Yogyakarta batik to the Semarang batik that we made).

3.2.3 Visualization and Embodiment of Gunungpati Batik Motifs

Table 5 visualizes exploring batik motifs through an aesthetic hybridization approach in Gunungpati. Intra-aesthetically, the visualization of batik motifs in Gunungpati combines inland and coastal motifs arranged in inland patterns. The idea of coastal motifs is sourced from Semarang’s natural and socio-cultural environment, namely, asem, warak ngendog, and mangroves. Asem and warak ngendok are similar in shape to the way in Bubakan. Next are mangroves, which are trees that grow around the coastline. The coast of Semarang is planted with many mangrove plants to overcome environmental damage. The expression of the ketinga motif is composed of style and lines and is full of isen-isen. The inland motif used is the same as in Meteseh, namely, the parang barong motif, including the written batik media used.

Visualization and embodiment of Gunungpati batik motifs through aesthetic hybridization approach

| Visualization and motif form | Aesthetic hybridization | |

|---|---|---|

| Inland motifs | Coastal motif | The embodiment of contemporary batik |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extra-aesthetically, creating batik at this center is also closely related to individual, social, environmental, and cultural creativity. This is found in the Inland and coastal patterns used in Gunungpati. The motifs that originate from the idea of the natural and socio-cultural environment of Semarang are arranged in a slope or incline (the influence of the parang slope motif as an inland motif that develops in Yogyakarta and Solo). Both Inland and coastal motifs are arranged in an inland slope pattern. All motifs are placed in an oblique or diagonal row. If in Meteseh the motifs used are only the coast, in Gunungpati, there are also inland motifs. The combination of this method makes Semarang batik similar to classic batik. This was conveyed by Heno (a Gunungpati batik craftsman) that: “… persiapan kami sudah sejak lama dengan cara mengamati identitas batik pedalaman atau klasik. Kami membuat batik Semarang memiliki kesan batik klasik. Harapannya, batik Semarang dapat lebih disuka (… Our preparation has been for a long time, observing the identity of the inland or classical batik. We make Semarang batik have a classic batik impression. The hope is that Semarang batik can be preferred).”

Based on the description of the data in Tables 3–5, it is known that the visualization of contemporary batik in the three Semarang batik centers is formed through an aesthetic hybridization process between coastal and interior-style batik motif forms. The presence of inland motifs such as traditional batik motifs of Kawung and Lereng is found in the Mateseh batik center (Table 3), while the Parang motif as a traditional batik motif is found in the Bubakan batik center (Table 4) and the Gunungpati batik center (Table 5). The same thing was also found in the existence of coastal batik motifs, at the Mateseh batik center, there were milkfish motifs, monuments, and Gedongsongo Temple (Table 3), Javanese tamarind batik motifs and Warak Ngendog (Tables 4 and 5) and mangrove motifs (Table 5). The findings indicate that there is a process of combining coastal and inland-style batik motifs as a unique phenomenon of the development of contemporary Batik in Semarang. The emergence of new motifs that develop from designer creativity and consumer preferences depart from pre-existing traditional motifs. The results of interviews with batik artisans at three batik centers show that the development of contemporary Batik in Semarang is carried out to meet consumer needs. These findings are reinforced by the latest research that by combining traditional elements with contemporary design aesthetics, Semarang batik can attract modern consumers while maintaining its cultural meaning. This balance between tradition and modernity is essential for the relevance and appeal of batik in today’s fashion and design market (Rismantojo et al., 2024).

Semarang batik artisans strive to maintain their identity. The forms of Semarang batik motifs with coastal style are more than the forms of interior motifs. If there is a form of interior batik motif, its function is to complement it. Interior motifs do not appear as the main motif in contemporary Semarang batik. This method is done on the machete motif created from the shape of the asem fruit and the kawung motif from the circular arrangement of milkfish (Table 3). These methods make the barrier of coastal and inland batik culture disappear into a new egalitarian identity. The findings of the data are in line with the results of the study, which states that contemporary batik is seen as a medium that can beautify the appearance of its wearer, with ornamental patterns that strengthen characteristics such as authoritative, openness, responsibility, dynamic, and simplicity (Rokhani, 2020). The development of Semarang batik also requires a special creative technique-based strategy to improve cost efficiency, quality, and uniqueness and accelerate production to be more competitive in the batik industry (Tjahjaningsih et al., 2015).

The egalitarian expression of contemporary Batik Semarang can be seen in the embodiment of batik patterns and motifs. In terms of motif patterns, contemporary Semarang batik uses a lot of inland patterns. Meteseh’s inland batik patterns are Kawung, Jlamprang, and slopes. In Bubakan, only the slope pattern is used, while in Gunungpati, the batik pattern is used in slope and Sekar Jagad. A free inland pattern is not found in the composition of contemporary Semarang batik motifs. When observed from the aspect of the motif’s form, coastal culture elements seem dominant. The inland motifs used are only the shape of machetes and Kawung, while there are many Semarang motifs. Semarang motifs include asem, blekok, Warak Ngendog, Semarang culinary, Semarang legends, mangroves, and the local wisdom of Gunungpati. This contrasts inland batik, which expresses symbols, rules, and norms that apply in the palace (for example, Yogyakarta and Surakarta batik motifs). However, in contemporary dance culture, those boundaries have disappeared. The batik industry in Semarang is now starting to develop batik motifs as a result of personal expressions that are free from the limits of traditional rules (Sugiarto et al., 2023; Syakir et al., 2019). Maintaining cultural heritage and ensuring its transmission to future generations sustainably are crucial to strengthening the nation’s creative economy and cultural identity (Yuliati & Susilowati, 2022).

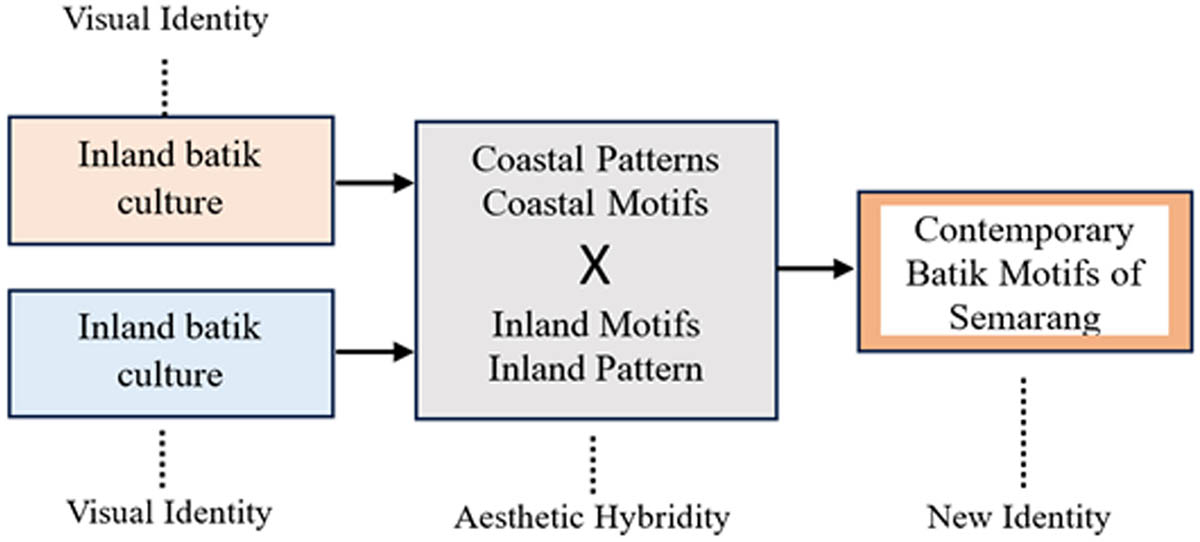

Based on the flow chart in Figure 4, it can be seen that the process of forming contemporary batik motifs is formed as a new identity: the existence of Inland and coastal batik culture as a visual identity and treasure of Semarang batik. Each of these cultural maceongs gives birth to two groups, namely, coastal motifs and patterns and inland motifs and patterns. Contemporary Semarang batik motifs were born from these two groups. The use of inland batik patterns is more dominant, as well as the form of inland motifs. The coastal batik pattern and the shape of the inland motif are recessive in their use. This shows that the nature of the free Semarang (coastal) batik pattern can flexibly follow the rules of strict inland patterns. Meanwhile, the standard inland pattern makes it difficult to follow the rules of the free coastal batik pattern.

Aesthetic hybridization of contemporary Semarang batik motifs.

The visualization of Semarang batik has different motifs and colors from other coastal batik. The motifs in coastal batik are often naturalistic, with bright colors, depicting elements from the local environment, such as tamarind, butterflies, marine vegetation, coconuts, and flowers (Hadi et al., 2018; Surya et al., 2019; Syakir et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the characteristics of inland batik motifs are more symbolic and often carry a deeper cultural and spiritual meaning, incorporating Sufism motifs made while performing dhikr, which reflects their spiritual meaning (Fadlia & Katiri, 2021). Bright colors characterize coastal batik and vary with contrasting colors such as red and yellow (Hadi et al., 2018). Inland batik usually uses softer and simpler colors such as brown, white, black, and blue (Fadlia & Katiri, 2021). The existence of Semarang batik is very significant in the context of cultures and history as a process of adaptation and evolution. Semarang Batik has evolved from its traditional roots to incorporate modern design elements, making it relevant in contemporary fashion while preserving its cultural essence. This evolution is seen in adapting traditional motifs to fit modern aesthetics and fashion trends (Budi et al., 2021, 2024). The development of contemporary Batik in Semarang was also created to respond to consumer preferences and satisfaction with batik influenced by harmonious shapes, color quality, cultural values, design innovation, affordable prices, active promotion, and sustainability (Li et al., 2024; Pratiwi et al., 2020). Furthermore, training efforts are needed to strengthen the practice of hybridization in the context of developing contemporary batik in Semarang. Long-term training for artisans balances traditional and modern techniques so that this cultural heritage survives and can be enjoyed by future generations (Corsini, 2021). This view is reinforced by the opinion that preserving batik as an intangible cultural heritage involves promoting its unique regional motifs and integrating modern design elements (Sugiarto et al., 2020).

Based on the findings of research and discussion, the practice of aesthetic hybridization is, in principle, an effort to combine various elements of ideas, styles, and techniques for creating and producing innovative, creative works of art by balancing aspects of preservation, application, and transformation of cultural forms. This statement reinforces the results of research that affirm that hybridization plays a key role in the innovation of traditional craft practices mobilized through three design strategies, namely, preservation, applicability, and transformation have a key role in the innovation and regeneration of contemporary craft practices (Kouhia & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, 2017). The application of aesthetic hybridization in the field of batik will increase aesthetic and visual diversity through ornamental patterns and colors in batik motifs. In decorative patterns, the visualization of contemporary Semarang batik features a variety of decorative patterns that are visually appealing and culturally meaningful that are not only abstract representations but designed to enhance the appearance of the wearer, reflecting qualities such as authority, openness, responsibility, dynamism, and simplicity (Budi et al., 2024). Meanwhile, the display of color intensity and texture of batik also helps to distinguish different patterns; the high color intensity and large size of the ornaments make the motif easy to recognize, while the low-intensity colors and small ornaments create a delicate and intricate design (Kasim et al., 2016).

Finally, aesthetic hybridization as a solution to problems and approaches that can be used in developing batik motifs has benefits in preserving and creating sustainable culture both on a local, national, and global scale. The benefits of cultural preservation and the emphasis on traditional crafts are not lost but are adapted to the contemporary context; innovation practices encourage creative collaboration and the development of new techniques and products, and sustainability practices are beneficial to promote the incorporation of traditional methods with modern efficiency. The benefits of global connectivity will facilitate building relationships between local artisans and global markets to increase the visibility and appreciation of traditional crafts.

4 Conclusion

The development of Semarang batik motifs originates from personal expressions that transcend traditional constraints. Batik artisans in Semarang face problems in realizing Semarang’s contemporary batik motifs, namely, the orientation of preserving tradition and development efforts through batik innovation. To overcome these problems, aesthetic hybridization can be a strategy for creating contemporary batik designs that can creatively adapt elements of tradition and innovation. The process of creative exploration of batik artisans in Semarang is an effort to face the conflict between tradition and innovation as well as consumer demands and the development of batik technology and culture through the process of aesthetic hybridization (coastal and inland styles) in creating contemporary Semarang batik motif designs. In Meteseh, the design of batik motifs has an Inland feel; in Bubakan, the design of batik motifs is more dominant with coastal characteristics, and in Gunungpati, the batik motifs seem to be harmonious with these two elements. In the aspect of patterns, contemporary Semarang batik designs generally show the dominant inland way and the recessive coastal way, while in the motif aspect, it is the opposite. The embodiment of Semarang batik seeks to combine elements of artistic identity, tradition, and innovation with its creativity by incorporating orderly Inland and egalitarian coastal batik styles through aesthetic hybridization to form a new identity. Batik artisans in Semarang can eliminate the strict barriers of inland batik culture with open coastlines in a new egalitarian way.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his deepest gratitude to the Rector of Universitas Negeri Semarang and the Chairman of the Institute for Research and Community Service of Universitas Negeri Semarang for funding the writing and publication of this article. The author also expressed his gratitude to the batik artisans in Meteseh Tembalang, Gunung Pati, and Bubakan Batik Village, Semarang, for their assistance and cooperation in the research.

-

Funding information: The publication of this article is supported by the Implementation of Basic Research at Universitas Negeri Semarang through the DPA LPPM UNNES Fund in 2024, with agreement number: 78.26.2/UN37/PPK.10/2024.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and agreed to its submission. Syakir, Gunadi, and Bangkit Sanjaya – conducting research, developing methodologies, and utilizing research resources. Riza Istanto, Untung, and Moh Fathurrahman – analysis of research data curation and preparation of article drafts. Bandi Sobandi-review and editing of the final article.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts concerning this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing does not apply to this article as no data was generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Adams, L. S. (1996). The methodologies of art: An introduction. Westview Press. doi: 10.1111/1540_6245.jaac56.3.0304.Search in Google Scholar

Afreliyanti, S. (2015). Mengungkap Sejarah dan Motif Batik Semarang serta Pengaruh Terhadap Masyarakat Kampung Batik Tahun 1970–1998. Journal of Indonesian History, 3(2), 53–59.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Ababneh, M. M. (2020). The concept of creativity: Definitions and theory. International Journal of Tourism & Hotel Business Management, 2(1), 245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.1971.tb00449.x.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Shami, S. A., Damayanti, R., Adil, H., & Farhi, F. (2024). Financial and digital financial literacy through social media use towards financial inclusion among batik small enterprises in Indonesia. Heliyon, 10(15), 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34902.Search in Google Scholar

Amalia, N. V, Sutopo, W., & Hisjam, M. (2020). A comparative analysis for batik wastewater treatment equipment technology development in Indonesia: Technopreneurship & innovation system. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. doi: 10.1145/3429789.3429863.Search in Google Scholar

Anas, B. (1997). Batik: Buku Seri 8 Indonesia Indah. Yayasan Harapan Kita, BP3 Taman Mini Indonesia Indah.Search in Google Scholar

Anshori, Y., & Kusrianto, A. (2011). Keeksotisan Batik Jawa Timur: Memahami Motif dan Keunikannya. PT. Elex Media Kompotindo.Search in Google Scholar

Asikin, S. (2008). Ungkapan batik di Semarang: Motif batik Semarang 16. Citra Prima Nusantara Semarang.Search in Google Scholar

Bakri, A., Achmad, S. H., Kamalrudin, M. B., Yusop, N., Rahayu, S. T., Sidek, S. B., & Sri, M. (2018). Challenges and potential development of Laweyan batik industry. Opcion, 34(85), 1331–1340. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85062809267&partnerID=40&md5=c1923fe84d136ee5fc6f001dacb8c05d.Search in Google Scholar

Banindro, B. S., Sobandi, B., Pandanwangi, A., Mutmainah, B., & Hartono, B. (2024). The transition of hindu era Garuda visual element into islamic era batik patterns in Java. New Design Ideas, 8(2), 467–489. doi: 10.62476/ndi82467.Search in Google Scholar

Beneš, M. (2022). Hybridity in landscape/architecture. Journal of Digital Landscape Architecture, 2022(7), 2–11. doi: 10.14627/537724001.Search in Google Scholar

Bernabei, R., & Power, J. (2018). Hybrid design: Combining craft and digital practice. Craft Research, 9(1), 119–134. doi: 10.1386/crre.9.1.119_1.Search in Google Scholar

Budi, S., Affanti, T. B., & Mataram, S. (2024). Ornamental patterns of contemporary Indonesian batik: Clothing for strengthening the articulation of appearance characteristics. Wacana Seni, 23, 16–28. doi: 10.21315/ws2024.23.2.Search in Google Scholar

Budi, S., Widiastuti, T., Ardianto, D. T., & Mataram, S. (2021). Flower and plant variants as abstraction in Javanese batik motifs from classical to contemporary era. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 905(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/905/1/012145.Search in Google Scholar

Canclini, N. G. (1995). Hybrid cultures: Strategies for entering and leaving modernity. University of Minnesota Press. doi: 10.2307/1315432.Search in Google Scholar

Corsini, D. E. Ö. (2021). Aesthetic and cultural approach to the change in the making techniques of Karagöz Figures. Art-Sanat Dergisi, 16(16), 437–463. doi: 10.26650/artsanat.2021.16.0015.Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (Third Edit). SAGE Publications Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Di Stefano, E. (2016). DesignArt. Creative hybridizations between art and everyday objects. Rivista Di Estetica, 61, 65–76. doi: 10.4000/estetica.1057.Search in Google Scholar

Dwiyanto, D., & Nugrahani, D. (2002). Perubahan Konsep Gender dalam Seni Batik Tradisional Pedalaman dan Pesisiran. Humaniora, 14(2), 151–164. https://journal.ugm.ac.id/jurnal-humaniora/article/view/753/598.Search in Google Scholar

Fadlia, A., & Katiri, Z. A. (2021). Sufism movement in rifa’iyah batik art in pekalongan-batang during 1960–1980. In Philosophy and the everyday lives (pp. 209–233). Nova Science Publishers, Inc. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85109243944&partnerID=40&md5=b4e9152a10796f627661d20a46dc97ab.Search in Google Scholar

Fadly, H. D., & Pramudita, D. A. (2024). Development of a virtual reality Museum batik Danar Hadi to present a diverse variety of original solo Batik motifs. In I. N. & S. Y. (Eds.), AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2926, Issue 1). American Institute of Physics Inc. doi: 10.1063/5.0185159.Search in Google Scholar

Gal, M. (2023). Visual hybrids and nonconceptual aesthetic perception. Poetics Today, 44(4), 545–570. doi: 10.1215/03335372-10824170.Search in Google Scholar

Gundumogula, M., & Gundumogula, M. (2020). Importance of focus groups in qualitative research. International Journal of Humanities & Social Science, 8(11), 299–302. https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-03126126/document.10.24940/theijhss/2020/v8/i11/HS2011-082Search in Google Scholar

Guntur, G., Ponimin, P., & Purnomo, M. A. J. (2023). Innovation and creativity in batik motif design: A study of students’ art theses. Creativity Studies, 16(2), 668–681. doi: 10.3846/cs.2023.14838.Search in Google Scholar

Hadi, S., Qiram, I., & Rubiono, G. (2018). Exotic Heritage from Coastal East Java of Batik Bayuwangi. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 156(1), 012018. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/156/1/012018.Search in Google Scholar

Hananto, B. A., Syarief, A., & Ujianto, A. N. (2018). Pengembangan Motif Batik Semarangan Menggunakan Tipografi sebagai Gagasan Visual. Jurnal Seni Dan Reka Rancang: Jurnal Ilmiah Magister Desain, 1(1), 1–18. doi: 10.25105/jsrr.v1i1.3874.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, T.-C., & Jin, M. (2024). Innovating sustainable fashion design: An exploration of the sustainability of a hybrid method through the C2CAD framework. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/17543266.2024.2436093.Search in Google Scholar

Kasim, A. A., Wardoyo, R., & Harjoko, A. (2016). Feature extraction methods for batik pattern recognition: A review. In M. Mahardika, R. Roto, A. Kusumaadmaja, Sholihun, T. R. Nuringtyas, A. Widyaparaga, & N. Hadi (Eds.), AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 1755). American Institute of Physics Inc. doi: 10.1063/1.4958503.Search in Google Scholar

Kouhia, A., & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2017). Towards design hybridity: Negotiating traditions through contemporary craft making in Finland. Craft Research, 8(2), 169–192. doi: 10.1386/crre.8.2.169_1.Search in Google Scholar

Kusumawardani, S. D. A., & Kurnani, T. B. A. (2021). Assessment tool to understand the readiness of Batik SMEs for Green Industry. In S. Withaningsih, D. Supyandi, G. L. Utama, & A. D. Malik (Eds.), E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 249, pp. 1–4). EDP Sciences. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202124902008.Search in Google Scholar

Kusumawati, N., Rahmadyanti, E., & Sianita, M. M. (2020). Batik became two sides of blade for the sustainable development in Indonesia. In Green chemistry and water remediation: Research and applications (pp. 59–97). Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-817742-6.00003-7.Search in Google Scholar

Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2016). Design, practical research: Planing and design (Elevent Ed). Pearson Education Limited.Search in Google Scholar

Lestari, M., Irawan, A., Rahayu, W., & Parwati, N. W. (2018). Ethnomathematics elements in Batik Bali using backpropagation method. In M. Ramli, N. Y. Indriyanti, G. Pramesti, & P. Karyanto (Eds.), Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1022, Issue 1). Institute of Physics Publishing. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1022/1/012012.Search in Google Scholar

Li, X., Sun, Z., Liao, S., & Romainoor, N. H. (2024). Consumer-driven analysis of design requirements for Gejia batik products. Journal of Silk, 61(7), 91–101. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-7003.2024.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, G., Shi, Q., Yao, Y., Feng, Y., Yu, T., Liu, B., Ma, Z., Huang, L., & Diao, Y. (2024). Learning from hybrid craft: Investigating and reflecting on innovating and enlivening traditional craft through literature review. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings. doi: 10.1145/3613904.3642205.Search in Google Scholar

Luo, S., Zhang, L., Tian, X., & Lü, J. (2024). Hot spots and development trends of digital intelligent design technology research on batik products. Journal of Silk, 61(7), 1–13. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-7003.2024.07.001.Search in Google Scholar

Maulany, N. N., & Masruroh, N. N. (2017). Kebangkitan industri batik Lasem di awal abad XXI. Patrawidya, 18(1), 1–12. http://redayabatik.com/.Search in Google Scholar

Minarno, A. E., Soesanti, I., & Nugroho, H. A. (2024). Optimization of BatikGAN with Gradient Loss for Enhanced Batik Motif Generation. 2024 6th IEEE Symposium on Computers and Informatics, ISCI 2024 (pp. 305–310). doi: 10.1109/ISCI62787.2024.10668317.Search in Google Scholar

Mishra, L. (2016). Focus group discussion in qualitative research. TechnoLearn: An International Journal of Educational Technology, 6(1), 1–5. doi: 10.5958/2249-5223.2016.00001.2.Search in Google Scholar

Octavia, A., & Sriayudha, Y. (2024). A Study of Jambi batik artisans in innovation and strategic decision-making to influence the development and resilience of the Jambi batik industry. Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Terapan Universitas Jambi, 8(2), 760–772. doi: 10.22437/jiituj.v8i2.38037.Search in Google Scholar

Parhusip, H. A., Purnomo, H. D., Nugroho, D. B., & Kawuryan, I. S. S. (2023). Integration of STEAM in teaching modern geometry through batik motifs creation with algebraic surfaces. International Journal for Technology in Mathematics Education, 30(1), 37–44. doi: 10.1564/tme_v30.1.3.Search in Google Scholar

Pratiwi, A., Riani, A. L., Harisudin, M., & Sarah Rum, H. P. (2020). The development of market oriented batik products based on customer buying intention (industrial center of batik sragen Indonesia). International Journal of Management, 11(3), 373–389. doi: 10.34218/IJM.11.3.2020.040.Search in Google Scholar

Putra, F. A., Jamil, D. A. C., Prabandanu, B. A., Faruq, S., Pradana, F. A., Alya, R. F., Santoso, H. A., Al Zami, F., & Saputra, F. O. (2021). Classification of batik authenticity using convolutional neural network algorithm with transfer learning method. 2021 6th International Conference on Informatics and Computing, ICIC 2021. doi: 10.1109/ICIC54025.2021.9632937.Search in Google Scholar

Rahayu, M. D., & Alrianingrum, S. (2014). Perkembangan Motif Batik Lasem Cina Peranakan Tahun 1900–1960. Journal Pendidikan Sejarah, 2(2), 36–49. https://ejournal.unesa.ac.id/index.php/avatara/article/view/7779.Search in Google Scholar

Rahmat, D. A., Rumanti, A. A., Pulungan, M. A., Rizaldi, A. S., & Amelia, M. (2024). Evaluating the role of open innovation and circular economy in enhancing organizational performance: Insights from batik small and medium enterprises in Banyuwangi, Indonesia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 16(24), 1–20. doi: 10.3390/su162411194.Search in Google Scholar

Reis, A. C. (2011). The esthetic experience from a phenomenological point of view. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 63(1), 75–86. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-79960112576&partnerID=40&md5=a015467b6415b6d3bf45b933dd158f53.Search in Google Scholar

Rens, H., & Veldhuisen, H. C. (1996). Batik from The North Coast of Java. Los Angeles County Museum of Arts.Search in Google Scholar

Rismantojo, S., Sirivesmas, V., Joneurairatana, E., & Natalia, W. A. (2024). Transforming the Batik Tiga Negeri (Three-Countries Batik) in Pleats to Represent Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand’s Batik Heritage by Applying the ATUMICS Method. Archives of Design Research, 37(4), 65–96. doi: 10.15187/adr.2024.08.37.4.65.Search in Google Scholar

Rohidi, T. R. (2011). Metodologi Penelitian Seni. Cipta Prima Nusantara Semarang.Search in Google Scholar

Rojak, M. F. A. (2023). Jaringan Perdagangan Batik di Pesisir Jawa Tengah 1840–1920. Historia Madania: Jurnal Ilmu Sejarah, 7(1), 1–16. doi: 10.15575/hm.v7i1.22869.Search in Google Scholar

Rokhani, U. (2020). The Musical Design of Gending Sekar Jagad Based on Batik Motif of Yogyakarta Style. Resital, 21(3), 163–172. doi: 10.24821/resital.v21i3.4110.Search in Google Scholar

Sachari, A., Puspita, A. A., & Nurcahyanti, D. (2020). Girilayu batik motifs and their forms of symbolic contemplation. Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology, 17(2), 207–216. doi: 10.3726/cul022020.0016.Search in Google Scholar

Salma, I. R. (2013). Corak etnik dan dinamika batik Pekalongan. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 30(7), 85–97. http://ejournal.kemenperin.go.id/files010483/journals/4/articles/1113/submission/original/1113-2802-1-SM.pdf.10.22322/dkb.v30i2.1113Search in Google Scholar

Sari, Y., Alkaff, M., & Pramunendar, R. A. (2018). Classification of coastal and Inland Batik using GLCM and Canberra Distance. In N. Hidayati, T. Widayatno, H. Prasetyo, & E. Setiawan (Eds.), AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 1977). American Institute of Physics Inc. doi: 10.1063/1.5042901.Search in Google Scholar

Sekimoto, T. (2016). Innovation, change and tradition in the batik industry. In M. Hitchcock & W. Nuryanti (Eds.), Building on Batik: The globalization of a craft community. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Subekti, D. W., Syakir, S., & Mujiyono, M. (2019). Pengembangan Desain Motif Batik Semarang pada Unit Usaha Batik Figa Semarang. Eduarts: Journal of Arts Education, 8(3), 27–34.Search in Google Scholar

Sugiarto, E., Othman, A. B., Triyanto, & Febriani, M. (2020). Regional icon motifs: Recent trends in Indonesia’s batik fabric development. Vlakna a Textil, 27(1), 93–98.Search in Google Scholar

Sugiarto, E., Syarif, M. I., Nashiroh, P. K., & Maulana, A. L. (2023). Feminine and masculine style as a spirit of contemporary ‘Batik’ textile making in Semarang. Research Journal in Advanced Humanities, 4(3), 69–81. doi: 10.58256/rjah.v4i3.1259.Search in Google Scholar

Suliyati, T., & Yuliati, D. (2019). Pengembangan motif batik semarang untuk penguatan identitas budaya Semarang. Jurnal Sejarah Citra Lekha, 4(1), 61–73. doi: 10.14710/jscl.v4i1.20830.Search in Google Scholar

Sun, S. (2023). Study on the ecological aesthetic characteristics of patterns on Nanjing Yunjin brocade. Journal of Silk, 60(5), 127–134. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-7003.2023.05.017.Search in Google Scholar

Sunaryo, A. (2009). Ornamen Nusantara: Kajian Khusus tentang Ornamen Indonesia. Semarang: Dahara Prize.Search in Google Scholar

Supriyadi, S., & Prameswari, N. S. (2022). The process of making batik and the development of Indonesian Bakaran motifs. Vlakna a Textil, 29(1), 63–72. doi: 10.15240/tul/008/2022-1-008.Search in Google Scholar

Surya, R. A., Fadlil, A., & Yudhana, A. (2019). Identification of Pekalongan Batik images using Backpropagation method. In D. Y. Kusuma, A. A. Shah, A. Kumar, D. Bahrun, H. Humaida, Q. Hidayah, N. Irsalinda, I. T. R. Yanto, & J. Purwadi (Eds.), Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1373, Issue 1). Institute of Physics Publishing. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1373/1/012049.Search in Google Scholar

Syafii, & Rohidi, T. R. (1987). Ornamen ukir. IKIP Semarang Press.Search in Google Scholar

Syakir, S. (2017). Konstruksi Identitas dalam Arena Produksi Kultural Seni Perbatikan Semarang. Universitas Negeri Semarang.Search in Google Scholar

Syakir, S., Harto, D. B., & Basyakiya, C. R. (2019). Ilustrasi Legenda dalam Pengembangan Desain Motif Kontemporer Batik Semarang sebagai Wujud Penegasan Identitas dan Konservasi Budaya. Seminar Nasional Seni Dan Desain: Reinvensi Budaya Visual Nusantara, Jurusan Seni Rupa Dan Jurusan Desain Universitas Negeri Surabaya, September (pp. 437–449). https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/289435-ilustrasi-legenda-dalam-pengembangan-des-7282abd2.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Syakir, S, Sobandi, B., Fathurrahman, M., Isa, B., Anggraheni, D., & Sri, V. R. (2022). Tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.): Source of ideas behind the Semarang batik motifs to strengthen local cultural identity. Harmonia: Journal of Arts Research and Education, 22(1), 78–90. doi: 10.15294/harmonia.v22i1.36579.Search in Google Scholar

Syed Shaharuddin, S. I., Shamsuddin, M. S., Drahman, M. H., Hasan, Z., Mohd Asri, N. A., Nordin, A. A., & Shaffiar, N. M. (2021). A review on the Malaysian and Indonesian batik production, challenges, and innovations in the 21st century. SAGE Open, 11(3), 1–19. doi: 10.1177/21582440211040128.Search in Google Scholar

Tjahjaningsih, E., Rozak, H. A., & Utomo, A. P. (2015). Grand design strategy of accelerating the development of batik Semarangan craftsmenbased on advantage of specific creative technique. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 13(9), 6745–6761. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84963622905&partnerID=40&md5=660414a2615ce3578374d82bfe6a919f.Search in Google Scholar

Trach, Y., Tolmach, M., Chaikovska, O., Khrushch, S., Kotsiubivska, K., & Kushnarov, V. (2023). Hybrid art as a result of synthesis of art and technologies. In A. K. Nagar, D. Singh Jat, D. K. Mishra, A. Joshi (Eds.), Lecture notes in networks and systems (Vol. 579, pp. 657–665). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-7663-6_62.Search in Google Scholar

Triyanto. (2018). Belajar dari Kearifan Lokal Seni Pesisiran. Cipta Prima Nusantars.Search in Google Scholar

Wallas, G. (2015). The art of thought. Harcourt Brace.Search in Google Scholar

Wronska-Friend, M. (2019). Batik of Java: Global inspiration. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. doi: 10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0007.Search in Google Scholar

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and method (3rd ed.). Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Yuliati, D. (2010). Mengungkap Sejarah dan Motif Batik Semarangan. Paramita, 20(1), 1–20.Search in Google Scholar

Yuliati, D., & Susilowati, E. (2022). Developing the Motifs and the Strategies to Survive of Semarang Batik Creative Industries, in Semarang Central Java Province, Indonesia. E3S Web of Conferences, 359, 1–14. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202235902031.Search in Google Scholar

Zoran, A. (2013). Hybrid Basketry: Interweaving digital practice within contemporary craft. ACM SIGGRAPH 2013 Art Gallery, SIGGRAPH 2013 (pp. 324–331). doi: 10.1145/2503649.2503651.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction