Abstract

This article seeks to examine and categorize the varied uses of the term geographical imaginaries within the broader fields of the social sciences and humanities. Like related concepts such as spatial imaginaries, geographical imaginations, and imaginative geographies, the term gained traction in the early 2000s and has grown in prominence since. Following PRISMA guidelines, this literature review is based on an analysis of 116 articles containing the phrase geographical imaginaries, retrieved from the Scopus database. The corpus was carefully screened according to eligibility criteria. Through selected excerpts and interpretative commentary, the review aims to contextualize how geographical imaginaries are employed across different studies. The findings confirm earlier assumptions that the term is often used loosely. Approximately half of the analyzed articles relied on a generic, commonsense understanding of the term. Moreover, even when a more rigorous definition – rooted in established literature and supported by clear criteria – was employed, its application was not always consistent or methodologically robust. Finally, the review identifies the diverse research contexts in which geographical imaginaries are invoked and distinguishes between different types of imaginaries based on their scope and range.

1 Introduction

The aim of this article is to analyze and categorize the various contemporary uses of the term “geographical imaginaries” as it appears in the broader social science literature. While a key objective is to explore the varying definitions of the term, its core meaning can be succinctly summarized as “taken-for-granted spatial orderings of the world” (Gregory, 2009a, p. 282). Similar to related concepts like “spatial imaginaries,” “geographical imaginations” (Gregory, 1994, 2009b), and “imaginative geographies” (Gregory, 2009c, p. 284), the term gained popularity in the early 2020s and has continued to grow in prominence ever since (Watkins, 2015, p. 508). Geographical imaginaries appear in a wide range of humanities and social science literature addressing topics such as social phenomena, places, spaces, brands, landscapes, and complex health-related issues. For instance, scholars of migration and global mobility may view imaginaries as both drivers and deterrents of movement. Positive imaginaries – such as those surrounding Silicon Valley – can attract tech entrepreneurs, while negative or less appealing imaginaries may influence how American expatriates perceive postings in less conventional destinations, such as Kazakhstan or the Gulf States. As this article suggests, the use of geographical imaginaries varies significantly across the articles: in some, it serves as a central theoretical concept, in others, it functions as an analytical tool embedded within broader frameworks, playing either a primary or secondary role.

This literature review examines the concept of “geographical imaginaries” from its emergence until 2024, based on a Scopus-based literature query. Disentangling all the related notions that describe how people imagine social spaces and places is by no means an easy task, largely because their meanings often overlap. Additionally, as this review demonstrates, authors do not consistently use these terms but often employ them interchangeably (Wright, 2010). Nevertheless, this review focuses exclusively on “geographical imaginaries,” exploring how the term is employed in the literature. The main emphasis is on the various definitions used, the contexts in which the concept appears, and the scales to which it applies – macro, mezzo, or micro. This investigation provides insight into the meaning of this theoretical concept. The article identifies the most prevalent interpretations of “geographical imaginaries,” aiding in navigating its various, and sometimes contradictory, applications. The conceptual ambiguity arises from the term’s inconsistent usage across different studies. A deeper understanding of its contextual usage may be particularly revealing in cases where the explicit meaning remains vague or underdefined.

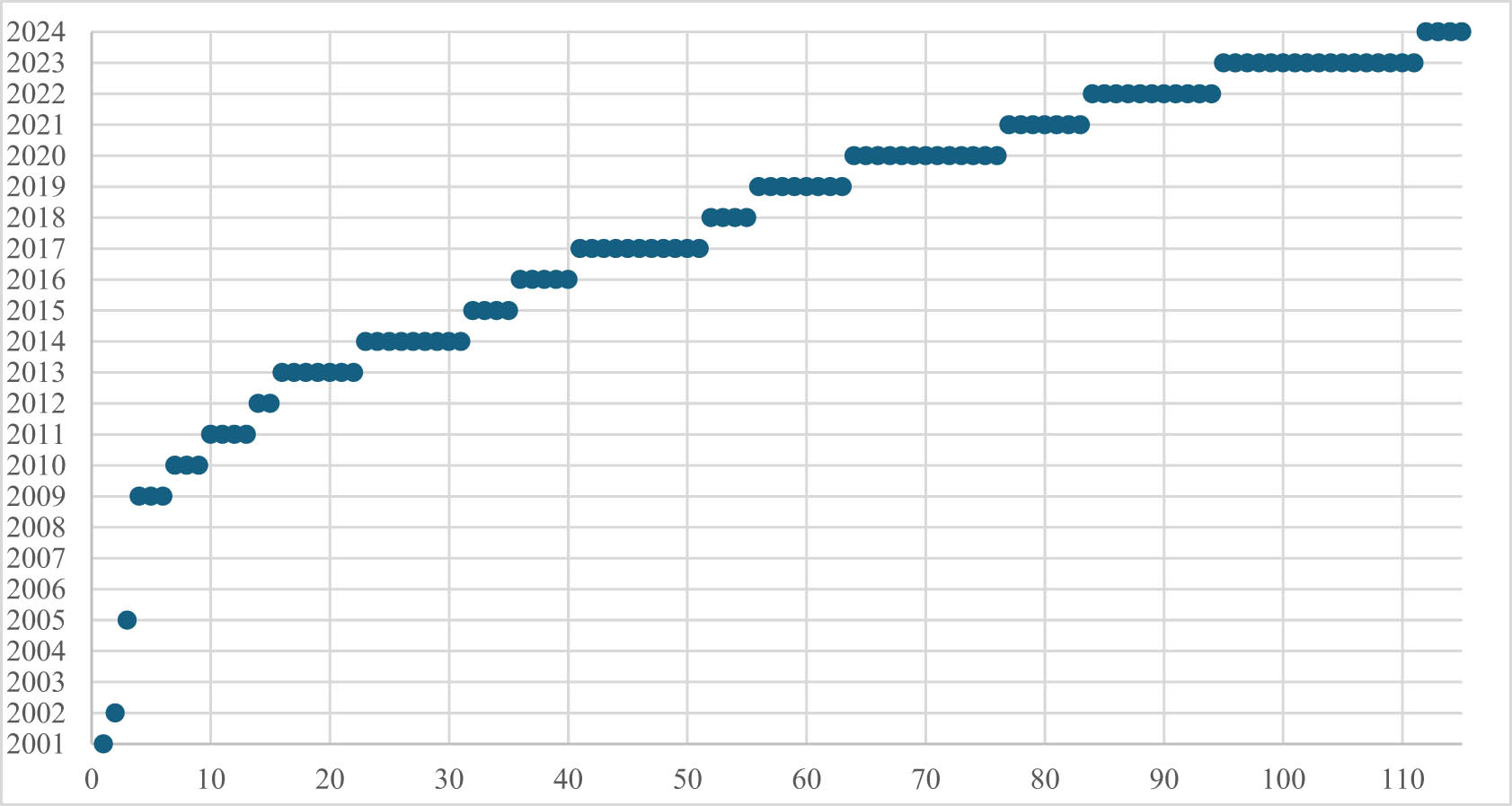

The working definition of an “geographical imaginaries” for the sake of this article is based on two key sources – the conceptual article on geographical imaginaries by Howie and Lewis (2014) and a chronologically earlier French-language influential article by Riaño and Baghdadi (2007), who discussed the geographical imaginaries (imaginaires géographiques) in the context of female migrants, directly pointing to the salience of the concept for the studies of migration and international mobility, and introduced this term in non-English language literature. Figure 1 presents the frequency of the phrase in the eligible sources (refer to Methodology section for details).

Distribution of studies over time.

According to Howie and Lewis (2014, p. 136), what distinguishes “geographical imaginaries” from “geographical imaginations” is the performative aspect – “geographical imaginaries are not just socially produced but also socially productive”; i.e. they frame understandings of the world. For these reasons, if we perceive them as a force in symbolic struggle, they are never stable but situated in social and cultural context – “constructed within life course experiences, emotion, personal background and memory, as well as in social framings of education systems, class, gender, ethnicity, and overt political and textual constructions” (Howie & Lewis, 2014, p. 136). “Geographical imaginaries,” understood as “conceptual armory,” is a valuable concept that is not only for scholars but also for school journalists, politicians, and teachers (Howie & Lewis, 2014, p. 132).

This understanding builds upon the earlier notions of geographical imaginations and imagined geographies. The interest in studying human imaginaries within a social context dates back to the philosophical writings of Jean-Paul Sartre, Cornelius Castoriadis, and Charles Taylor. The uses of “imaginaries” are so varied that it is not possible to analyze all the threads, or even map this vast literature. Instead, I focus on a narrower notion, yet not the one which focuses on spatiality at the cost of the social dimension of an imagination – “spatial imaginaries” (Watkins, 2015, p. 519). Although “geographical imaginaries”, just as spatial imaginaries, are inherently related to spatiality, they are also social imaginaries, in the sense that the spatial dimension is one of many dimensions, not necessarily the most important one.

The structure of this article is as follows. First, I detail the methodological assumptions of the scoping literature review. Although this is not a systematic literature review, I applied the PRISMA guidelines to select the cases, as this framework provides clear, actionable instructions for filtering studies – even when the sample represents only a portion of the existing literature.

Subsequently, this scoping review examines the literature on geographical imaginaries using six criteria: definitions, theoretical foundations, research contexts, range of imaginaries, and their overall scope. The findings section is structured around the research questions outlined below. I examine how geographical imaginaries are defined, their theoretical underpinnings, and the research contexts in which they appear. Additionally, I investigate the range of these imaginaries, exploring whether they pertain to smaller, individual perceptions or broader, all-encompassing narratives. Finally, I identify various categories of phenomena – such as the environment, global health, and society (“scope”) – that are analyzed through the lens of geographical imaginaries.

This review can lead to a more informed use of theoretical categories in future social analyses and, most importantly, maps the field, enabling researchers to navigate the diverse analyses that employ the notion of geographical imaginaries. Thus, the objective of this article is not only to demonstrate the inconsistency in how the concept of geographical imaginaries is defined, but also to show that its definition is often shaped by the specific research context.

2 Methodology

This study analyzes 116 sources that contain the phrase “geographical imaginaries,” retrieved from the Scopus database (Finfgeld-Connett, 2018). These sources explore geographical imaginaries in relation to various social phenomena (e.g., ethnic stereotypes), places and spaces, geopolitical concepts, health issues, and public security concerns (e.g., terrorism; Table 2).

Materials were selected based on the criteria specified below. The extensive pool of articles discussing “geographical imaginaries” was evaluated against these eligibility criteria. This review is predominantly qualitative, focusing on presenting the variety of definitions and types of “geographical imaginaries.” By providing excerpts from the articles along with their interpretations, the study contextualizes the analyzed imaginaries. Although a few attempts at quantification are made to assess the frequency of certain types, the polysemic nature of the material limits these quantifications as fully objective measurements. The numbers serve more as approximate indicators of the popularity of certain perspectives on imaginaries rather than precise measurements.

3 Procedure

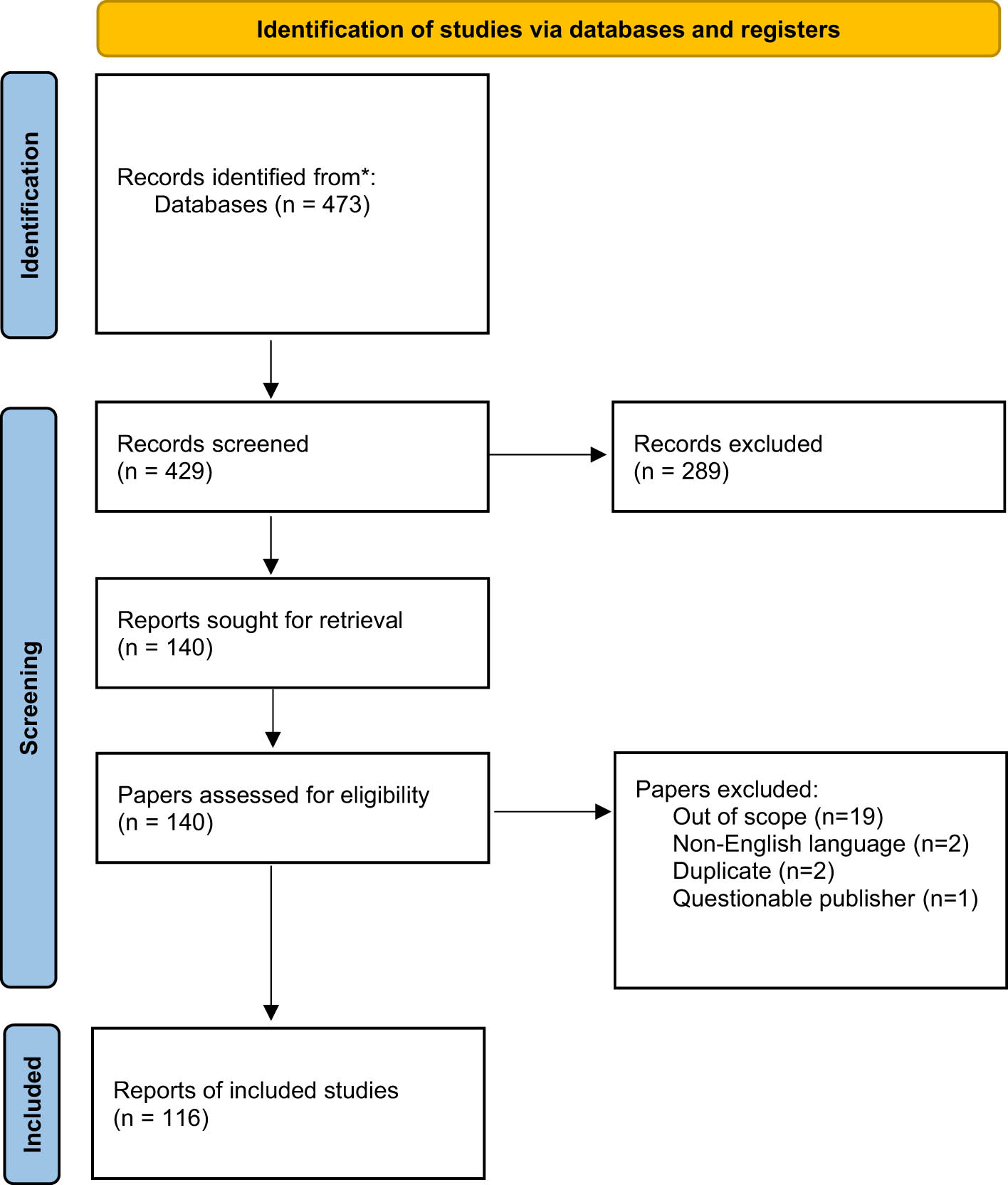

The literature review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines, which were designed to help authors provide a transparent description of the research procedures (Mak & Thomas, 2022; Page et al., 2021). The flow of information through the different phases of this review was depicted using the PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram[1] (Figure 2).

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

In brief, as shown in the figure above, PRISMA involves the following steps:

Search Records & Removal of Duplicates. The initial step involved identifying studies through database searches and removing duplicates.

Abstract-level Screening. An initial screening of abstracts was carried out to exclude irrelevant studies based on the inclusion criteria.

Full-text Screening. The full texts of potentially relevant studies were reviewed to confirm their adherence to the inclusion criteria.

Final Included Papers. The studies that remained after screening were meticulously analyzed and coded according to the established criteria.

In the preliminary search for studies on geographical imaginaries, I used the Scopus database, as it is broad enough to include many high-quality and other reliable academic articles while being selective enough to exclude publications from outlets with questionable reputations or limited impact on global academic debates. The initial search was conducted on June 11, 2024, using the following criteria:

Keyword: “geographical imaginaries”;

Search within: all fields;

Sources: all (journals, books, chapters, etc.).

This query, based on broad search criteria, produced 504 records, including journals, books, and chapters. Subsequently, I limited the query to “Social Sciences and Arts and Humanities,” resulting in 473 records. When further restricted to English-language entries, the total was 429 records, consisting of papers, books, and chapters published between 1999 and 2024. It is worth noting that the analysis included papers that used one of the synonymous terms discussed (e.g., spatial imaginaries, security imaginaries) or those that indicated a discussion of the topic under alternative naming, as long as the term “geographical imaginaries” appeared in the main text.

This number was further narrowed during the abstract-level screening process. If the phrase “geographical imaginaries” did not appear in the abstract, I screened the entire article for eligibility. Manual verification allowed me to exclude many articles that referenced geographical imaginaries in a largely superficial manner – for instance, when authors loosely referred to “imaginaries of island laboratories” in the Dutch and French Caribbean (Borie & Fraser, 2023). In some cases, the term “geographical imaginaries” appeared only in the references (Jeleff et al., 2023) but not in the abstract or main text. At this stage, if the context was unclear, I determined whether the article warranted an in-depth analysis.

In the abstract-level screening, supported by full-text review if necessary, I excluded certain studies that focused on narrow phenomena, particularly from history or art history, even when “imaginaries” were mentioned, albeit briefly. For example, I excluded an article examining the testimonial spaces of Nazi camps because “imaginaries” was only referenced in passing. Similarly, a study analyzing “reactions to the performance of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps” was not included, as it aimed to illustrate how rhythm is culturally and politically encoded through discursive and conceptual links to geographical imaginaries of place. The rationale for these exclusions is that the articles either mentioned geographical imaginaries only in passing or defined them strictly within the narrow context of their case studies, without linking them to contemporary societies or cultures. As a result, the definitions of imaginaries offered were not applicable to broader contexts or useful for explaining present-day social issues, as exemplified by the approach of by Howie and Lewis (2014) and Riaño and Baghdadi (2007).

During the full-text screening phase, I analyzed the complete texts of potentially relevant studies (n = 140) to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. At this stage, 24 articles were excluded for the reasons outlined in Figure 2. This phase enabled me to eliminate articles outside the scope of this research, such as those focused exclusively on historical phenomena (e.g., not addressing contemporary imaginaries) or those in which “geographical imaginaries” appeared only in the references, with no implicit reference in the content, even if they had passed the initial screening (as they appeared to address geographical imaginaries in the manner defined above). Ultimately, the research material was limited to 116 sources published between 2001 and 2024, primarily consisting of journal articles and chapters, with only a few entire books.[2]

4 Research Questions

The study addresses the following questions based on a scoping literature review:

How are “geographical imaginaries” defined in the literature of the social sciences and humanities?

What theories are employed in their conceptualization?

In what contexts does the analysis of imaginaries predominantly occur?

What types of imaginaries can we distinguish based on their “range,” understood as the level of analysis from micro to macro?

What types of phenomena are explored through the use of imaginaries?

5 Findings

The findings section is organized around the research question, as outlined above. Whenever possible, I refer to the total count of the articles that collectively constitute the analyzed pattern, using this to measure its prevalence. Most importantly, I discuss and provide examples of specific approaches based on the analyzed articles.

5.1 Defining Imaginaries

As expected, “geographical imaginaries” were defined in many different ways. What might seem less likely, however, is the extent of this diversity, with imaginaries being understood both as part of a clearly defined theoretical framework and as commonsensical concepts. The umbrella term “geographical imaginaries” can be separated into three of the most commonly used types of definitions.

5.1.1 Strict Definitions

The two most common are what I refer to as “strict” and “generic” definitions. Strict definitions are usually based on the literature and provide a clear operationalization of the term, typically as an image certain group of people or organization holds of something, which results in their beliefs or behaviors. The model's strict definition refers to clear criteria of the imaginaries, as discussed in the introduction. For instance, Hong (2020, p. 3) purports that the concept of “geographical imaginary” denotes “a” taken‐for‐granted spatial ordering of the world “through various value‐laden configurations”. This definition simultaneously stresses the naturalized character of mental representation, as well as a normative dimension, which can impact the performativity. Another strict definition was provided by Blecha and Leitner (2014, p. 87), who argued that imaginaries, understood not merely as representations of the world but as forces shaping “regimes of truth,” motivate the practice of backyard chicken-keeping. They examined how this practice is implicated in the construction of imaginaries. Such phrasing stresses the salience of imaginaries in the decision-making process as well as the interplay between practice and imaginaries. In the analyzed articles, similar efforts to clearly define the imaginaries were traced in 41 articles.

The theoretical underpinnings, which were extensively utilized in the articles based on strict definitions, varied significantly. Most of the authors, in various depths, referred to theories proposed by contemporary social scientists, Derek Gregory, Bob Jessop, David Harvey, Gearóid Ó Tuathail, John Agnew, Joanne Yao, Stephen Daniels, or Bernard Debarbieux. Very often the authors referenced Bill Howie and Nick Lewis as well Yvonne Riaño, and Nadia Baghdadi, the authors of, inter alia, two influential articles to which the acceleration of the debate on geographical imaginaries can be attributed (Howie & Lewis, 2014; Riaño & Baghdadi, 2007). Theoretical inspirations included also classics, such as philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Hannah Arendt, Cornelius Castoriadis, and Charles Taylor, and, most of all, Edward Said. Other theoretical inspirations were dispersed; names such as Albert O. Hirschman or David Lowenthal occurred sporadically. It is interesting, however, that nearly half of the analyzed articles (54 out of 116) did not quote any article theorizing geographical imaginaries. This does not mean that they avoided theoretical debates within their subject matter; however, the topic of “geographical imaginaries” was not discussed in relation to the academic literature.

5.1.2 Generic Understanding of An Imaginary

These articles typically used the second type of definition, which refers – explicitly or implicitly – to a mental image related to a group of people, place, or social phenomenon. I refer to these definitions, found in 44 of the analyzed articles, as the generic understanding of an imaginary. Therefore, it appears that the most common use of the term “geographical imaginaries” is marked by an absence of a clear definition, compelling the reader to interpret it in a generic, dictionary-based manner. For example, when Wright (2010) argues that feminist and queer theory may “expand geographic imaginaries of progressive politics,” it is not entirely clear how these notions relate to geography or spatiality. Aschenbrenner (2023, p. 62), on the other hand, employed the generic meaning of “imaginary” in her chapter on the political ecology of a diverse urban ethics of marine stewardship in New Zealand, referring to general images of the Hauraki Gulf Tīkapa Moana. Koch (2016, p. 3), when discussing nationalist attachment to a country among non-nationals, restricted herself to this clear yet simple conceptualization of an imaginary, which appears to function as a synonym for political narrative. Schech (2017), in turn, uses “geographical imaginaries” and “spatial imaginaries” interchangeably.

Furthermore, in rare cases, the generic definitions of imaginaries were mixed within the same article, leading to confusion regarding the conceptual content of the notion under study. For instance, Harris (2011) discusses various imaginaries that appear to represent different social orders. They are difficult to theorize under one definition or conceptualization. Thus, in Harris’s article, “the imaginary” was understood as a general concept of an image, without a clear indication of how or by whom this image is constructed, or the consequences of such narrative schemata.

Specifically, I argue that narratives of environmental change in evidence cannot be understood without an appreciation of broader geographical imaginaries that hold importance for this region – whether they be imaginaries related to the Kurdish southeast that has been forgotten as part of Turkish modernization efforts, or imaginaries related to the need for Turkey to “catch up” to the West that have been present since before the establishment of the Turkish republic in 1923 and remain salient today as frequent refrains in ongoing debates related to possibilities for Turkish accession to the European Union (Harris, 2011, p. 195, emphasis added).

5.1.3 Imaginary About

A similar kind of definition, found in 18 cases across the sample, can be named an “imaginary about”, as it appears in Maraud and Guyot’s 2016 paper comparing the uses of imaginaries about two places – Swedish Lapland and the Cree of James Bay in Quebec. Simone Arnaldi (2014, p. 7) discussed, in turn, “representations of Italy and other countries that are involved in nanotechnology development as they appear in elite newspapers and newswires.” While in the case of “about” imaginaries, it is possible to deduce the implied meaning (with imaginary often being equated with an image), they, like “generic” imaginaries, differ from strict definitions that provide a clear understanding of the concept.

5.1.4 Implicit Definitions

Moreover, as Table 1 indicates, some papers included in this review utilized only an implicit definition of geographical imaginaries, with the term appearing solely in the references as part of someone else’s work. In these cases, the term itself was not explicitly mentioned, but the content referred to phenomena that could be encompassed by it. For example, Wyndham’s (2014) chapter on Afghan identity and nation-building frequently refers to the “Western imagination,” which could be interpreted as aligning with the concept of geographical imaginaries.

Ways of defining geographical imaginaries

| Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Generic usage | 44 |

| Strict definition | 41 |

| “Imaginary about” | 18 |

| Implicit definition | 10 |

| Imaginaries as fictional inventions | 1 |

| Unclear/mixed understandings | 2 |

| Total | 116 |

Context of geographical imaginaries

| Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Geographical imaginaries of social phenomena | 40 |

| Geographical imaginaries pertaining to different places/spaces (e.g., countries, cities) | 39 |

| Geographical imaginaries in geopolitics | 15 |

| Geographical imaginaries in relation to health | 6 |

| Geographical imaginaries of security and insecurity | 7 |

| Other contexts | 9 |

| Total | 116 |

5.1.5 Other Definitions

Furthermore, one author proposed that imaginaries are something invented or untrue, which appears to contradict Said’s (1978) assertion that products of imagination should not be mistaken for fantasy. Nash (2023, p. 12), in her article on German politics, states that “the argument of the AfD [Alternative für Deutschland – a far-right populist political party] is as follows: anthropogenic climate change is imaginary,” implying that “imaginary” could be synonymous with “unreal” or “fanciful.” All other authors seemed to disagree with this definition, with some explicitly rejecting it (e.g., Trandafoiu, 2022, p. 8).

This section suggests that the term “geographical imaginaries was used quite freely across the sample. Articles based on generic or unclear definitions, as well as those equating imaginaries with images, were prevalent in the sample. Additionally, many articles referred to geographical imaginaries using different frameworks, often implicitly referencing what might be considered geographical imaginaries. This finding aligns with Grubbauer’s (2013, p. 338) observation that the “notion of economic imaginaries” she examined was “often used quite freely,” typically referenced without elaborating on its content or discussing how to validate the performativity of imaginaries. It is worth noting, however, that even when the notion of “geographical imaginary” is underdefined and appears only “in passing,” it often plays a pivotal role in the argument (Howie & Lewis, 2014, p. 137).

5.2 Research Context

The analyzed articles were also examined to determine the context in which the investigation of imaginaries occurs. These contexts are defined as the broader settings in which the discussion takes place. Understanding the research context provides greater insight into the article’s content than simply knowing its disciplinary affiliation. However, the latter can still be significant, as the discipline largely defines the research context. Of the 116 articles analyzed, 60 are primarily from geography – though this categorization is not always straightforward – 16 from sociology and social anthropology, 12 from political science and international relations, 8 from cultural studies, and the remaining from various other disciplines, including education, European studies, media studies, management, and tourism and urban studies. Assessing disciplinary affiliation is often complex. Therefore, factors such as the scope of the article (defined by the issues being analyzed), the author’s disciplinary background, and the profile of the journal or book series were considered when creating this approximate estimation.

5.2.1 Imaginaries of Social Phenomena

Among the analyzed articles, five distinct usage contexts can be identified. The majority of the articles address social phenomena (n = 40), including housing tenure, “new” state capitalism, and the spatial politics of the “more-than-economic” European crisis. A clear example is Manet’s book, which explores the transnational salsa circuit. From the perspective of this scoping review, the most significant feature of this book is its analysis of “the circulation of people and a specific imaginary of salsa” (Menet, 2020, p. 39). Menet (2020, p. 124) demonstrates that imaginaries can be produced in various ways, highlighting how certain countries, like Nicaragua, are rarely placed on the “imaginary salsa map.” Notably, a substantial portion of the literature related to social issues focuses on international migration, such as migration governance along the Balkan Route (Bergesio & Bialasiewicz, 2023) or international students navigating the ambiguous terrain between political constraints and aspirations for a better life (Ginnerskov-Dahlberg, 2021).

5.2.2 Imaginaries of Places

Geographical imaginaries related to different places (n = 39) are typically the domain of human geographers, encompassing processes from various backgrounds. These imaginaries are usually discussed in detail, with scholars often drawing on theoretical inspirations from diverse traditions. The analyzed places and spaces range from the Malay world, Scotland (as seen from the perspective of Polish immigrants), and the Carpathian Basin, to Chicago’s city hall, and even “outer space” (Hunter & Nelson, 2021).

5.2.3 Imaginaries of Geopolitics

Furthermore, in many studies, geographical imaginaries pertain to geopolitics (n = 15). For instance, Oksamytna (2023) discusses imperialism and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, making an interesting point when she claims that “Russians on Internet forums imagined that Ukrainians in Europe would do nothing but prostitution and cleaning toilets, activities befitting their inferior status in Russian eyes” (Oksamytna, 2023, p. 505). Other studies explored topics such as geographical imaginaries in Central Europe (Balogh et al., 2022), the “EUropean Politics of State Recognition” (Wydra, 2020), and cartoons depicting the Arab Spring (Moore & Purcell, 2021).

5.2.4 Geographical Imaginaries in Other Contexts

Two clearly distinguishable, yet smaller groups consist of imaginaries related to health studies and peace and war studies. An example from the former is a article examining the “realities that shaped the identities and bodies” of women exposed to the Zika virus (Rivera-Amarillo & Camargo, 2019). Other authors explored geographical imaginaries in the context of tobacco addiction and Latin America’s position on the map of global health. In contrast, scholars exploring imaginaries of security and insecurity addressed a range of topics, including the externalisation of EU borders (Ould Moctar, 2022), imaginaries of terrorism (Mustafa & McCarthy, 2020), and piracy in the Gulf of Aden (McNeill, 2023).

The nine cases categorized as “other” encompassed a diverse range of topics, including imaginaries in U.S. stamps, intersectional sensibilities, and various theoretical issues such as cosmopolitanism, transnationalism, and the concept of geographical imaginaries itself.

5.3 Types of Imaginaries – Range

This literature review allowed me to categorize the analyzed imaginaries also by dividing them into three groups based on the scope of the concept: “macro imaginaries, “ “mezzo imaginaries,” and “micro imaginaries.” A similar distinction had been introduced by Robins (2022, p. 22), who contrasted small-scale imagined social objects, such as “family,” with larger, more abstract concepts like “country,” “nation,” and “people.” Phelps et al., (2011, p. 419) also differentiated levels of imaginary analysis but did so from a slightly different perspective. They proposed that at the “mesolevel,” researchers should analyze “the content of imaginaries, their transmission via a diversity of agents and mechanisms; their constitution and appeal to audiences at multiple geographical scales,” and examine “how mobile imaginaries intersect with those associated with the relative fixity of state territoriality.” However, it remained unclear what constituted the micro and macro levels. Similarly, when Zhang and Thill (2019) referred to “diverse imaginaries of the mesoscale structures of the world” articulated by geographers, concepts such as “core-periphery hierarchy,” “a flat world,” “a spiky world,” and “fuzzy world regionalization” actually pertained more to the macroscale.

In this article, I propose an alternative categorization based on a clear epistemological criterion: the level of production of imaginaries, which can also be referred to as “range (Table 3).” The micro level consists of analyses based on individual accounts, such as those examined through in-depth interviews. In contrast, the mezzo and macro levels rely on different types of sources – media discourses, vast communication networks, and official documents. I suggest designating a source as a macro source when it applies to a global or continental scale. If the scale is local, national, or, at best, supranational, it is categorized as mezzo. According to this categorization, Robins’s (2022) article would be classified as a micro analysis, as the author references residents of São Paulo whose friends or family previously emigrated, rather than a macro level, merely because he discusses “country,” “nation,” and “people.”

Range of geographical imaginaries

| Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Macro | 44 |

| Mezzo | 31 |

| Micro | 25 |

| Other/Unknown | 16 |

| Total | 116 |

5.3.1 Macro Imaginaries

The first category (“macro imaginaries,” n = 44) encompasses articles that analyze the broadest imaginaries associated with global perceptions of places, phenomena, international networks, or global organizations. A good example is a article discussing how “northern dreams, imaginaries, and fantasies” have facilitated mass tourism in Lapland, alongside the challenges these imaginaries face, such as climate change, which leads to less snow – crucial for creating these mental images (Herva et al., 2020). This article was focused on the global image of the Arctic and Lapland and deliberately refrained from addressing the imaginaries of any particular group or those prevalent in a specific country or location.

5.3.2 Mezzo Imaginaries

Mezzo imaginaries (n = 31), while general in nature as they extend beyond the imaginaries of specific individuals, are tied to identifiable and named places. For example, Planey’s (2020) study of the Chicago metropolitan region examines the proliferation of post-recession regional economic development initiatives and the shift towards manufacturing-centric programs led by regional planning bodies and public–private institutions (Planey, 2020, p. 258). These imaginaries function above the level of individual practices but are situated within a more specific context than macro imaginaries. They are shaped and processed by stakeholders such as local governments, think tanks, and politicians. Although they pertain to individual citizens, they are also influenced by federal administrative politics and media discourses.

Another example is Ibrahim and Howarth’s (2016) analysis of the Eastern European Horsemeat Scandal in the UK, triggered by the detection of horse DNA in beef burgers sold in Irish and British supermarkets. This level is broader than individual perspectives but less general than global or continental imaginaries, involving relationships between the UK and a few other countries – Poland and Romania (accused of supplying the tainted meat) as well as Spain (allegedly acting as an intermediary).

5.3.3 Micro Imaginaries

The micro level, in turn, focuses on the (1) production of imaginaries and (2) their consequences in the context of individual biographies. These two subtypes, while both based on individual experiences, are quite distinct. In the first case, the process of imaginary production can be traced in the experiences of Nepali migrants moving to Malta (Neubauer, 2024) or in the memories of people living near the Lonquimay volcano in Chile (Walshe et al., 2023). In the second type of analysis, Lulle (2020, p. 1) explores “the nuanced modalities of ethnicity and ‘Eastern Europeanness’ and how these inform everyday encounters with people from different ethnicities and races, particularly when meeting co-ethnics” in London.

5.4 Types of Imaginaries – Scope

The final way to organize geographical imaginaries is by focusing on the topics discussed in the analyzed articles, as opposed to the broader research context addressed earlier. In his review article on spatial imaginaries, Watkins (2015) distinguished three types: “imaginaries of places, idealized spaces, and spatial transformations”. When I attempted to open-code the topics covered by the articles, it became evident that the emerging themes could be grouped into slightly different categories based on the main subjects addressed in the articles.

5.4.1 Geographical Imaginaries in Research on Selected Social, Political, and Economic Issues

According to this categorization (Table 4), the papers most frequently (n = 38) addressed social issues, including postindustrial narratives of primary commodity production (Bridge, 2001), the rollout of education for sustainability (Le Heron et al., 2012), and multinational migration (Thompson, 2020). A significant number of articles also focused on political and economic imaginaries (n = 26), discussing policies and political actions such as Italy’s closed-port policy (Aru, 2023), the proposal to introduce a “climate passport” in Germany (Nash, 2023), and the Mediterranean neighborhood and the European Union’s engagement with civil society following the “Arab Spring” (Bürkner & Scott, 2019).

Scope of geographical imaginaries

| Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Society | 38 |

| Politics/Economics | 26 |

| Image | 20 |

| Theory | 13 |

| Environment | 10 |

| Global health | 6 |

| Other (e.g., terrorism, methodology) | 3 |

| Total | 116 |

5.4.2 Reflections on Imaginaries

The next group of articles engaged in a discussion of imaginaries for their own sake (n = 20), exemplified by Watson’s (2024) analysis of the imaginaries in the production of From Our Own Correspondent on BBC Radio 4. This also aligns with the previously cited work of Herva et al. (2020), which examines the construction of Arctic motifs and imaginaries by the Christmas tourism industry. Additionally, several articles interpret imaginaries as concepts synonymous with images, focusing on the effects of marketing campaigns and branding (Hall, 2017; Lewis, 2011; Saunders, 2014). These articles often built upon the “imaginaries about” discussed in the first analytical section.

5.4.3 Theoretical Orientations and Other Specialized Foci

Over one in ten analyzed articles (n = 13) dealt with strictly theoretical issues, such as the relationships between “geography and imagination(s)” (Kearns et al., 2015) or pre-national transnationalism and translocalism (Featherstone, 2022). A significant number of papers addressed environmental issues, such as climate change imaginaries associated with sea level rise in North Wales (Arnall & Hilson, 2023) or the challenges and opportunities related to a rapid Arctic thaw (Bruun and Medby, 2014). The remaining articles discussed topics such as global health, terrorism, and various methodological issues.

6 Discussion

The article confirmed existing assumptions (Howie & Lewis, 2014; Watkins, 2015) that the term “geographical imaginaries” is used quite loosely across studies. Half of the articles examined relied on a generic definition or “imaginaries about,” based on a commonsense understanding of the term. Only one in three articles was written with an explicit conceptualization of geographical imaginaries. Furthermore, even when a article adopted a strict definition – rooted in clear criteria and grounded in the literature – it is notable that this did not always translate into a consistent or rigorous application of the term in the results section.

Moreover, the analyzed sources suggest that clearly delineating the boundaries between “imaginaries” (synonymous with the less commonly used term “geographical imageries”) and related concepts is a challenging task. Few authors make such distinctions, as exemplified by Cangià and Zittoun (2020), who differentiate between “imaginaries” – defined as a stable, shared, and transmitted toolkit resulting from imagination – and dynamic “imagination,” characterized as “an ever-changing embodied and creative activity both embedded in and shaping the social and cultural world around” (Cangià & Zittoun, 2020, p. 643). More often, however, there is a terminological confusion.

In the analyzed pool of articles, various adjectives were associated with the core term “imaginaries” (Jiang et al., 2022), significantly altering its meaning. The two most common conceptual solutions are “spatial imaginaries” – a concept that has been explored in-depth (Watkins, 2015) – yet a comprehensive literature review is still lacking, and “geographical imaginations.” The challenge with the latter term is its distinctly different meaning, however, some authors analyze “geographical imaginations” and various “imaginaries” simultaneously, making it difficult to disentangle the two.

To some extent, it is possible to differentiate between “geographical imaginaries” and synonymous terms that emphasize connections to other disciplines, such as “social imaginaries”, “political imaginaries” (sometimes referred to as “high-politics imaginaries”), and “economic imaginaries.” While geographical imaginaries – indistinguishable in this regard from spatial imaginaries (Watkins, 2015) – are always related to spatiality, social, political, and economic imaginaries do not necessarily incorporate this aspect. Among these, the concept of “economic imaginaries” is drawn from cultural political economy and is precisely defined, often based on Bob Jessop’s conceptualizations, which describe them as “simplified, necessarily selective mental maps of a supercomplex reality,” rather than as purely representational accounts of an external reality (Lewis, 2018, p. 5; Grubbauer, 2014).

What further complicates the analysis is the presence of hybrids in the reviewed literature, such as “socio-spatial imaginary” and “social and spatial imaginaries,” which appeared in the same article (Bürkner & Scott, 2019). Additionally, the authors referenced “ethno-spatial imaginaries” (Maraud & Guyot, 2016), also known as “ethno-spatial representations.” These hybrids hinder the ability to ascertain a clear and consistent meaning as intended by the authors, not to mention the ontological and epistemological assumptions that underlie these terms.

Furthermore, articles on geographical imaginaries employ a broad array of concepts that narrow the boundaries of what constitutes “geographical imaginaries.” In alphabetical order, these concepts included “Anthropocene imaginaries,” “anti-colonial imaginaries,” “common tourist imaginary,” “diasporic imaginations,” “geopolitical imaginaries,” “imaginary-as-brand” (or “commercial imaginaries of national branding”), “medical imaginaries,” “military imaginations of outer space,” “national imaginaries,” “nationalist imaginaries,” “neighborhood imaginaries,” “neoliberal imaginary,” “racist imaginaries,” “religious imaginations/geographical imaginaries,” “urban imaginaries,” and “aesthetic imaginaries.” Many of these terms are intuitive in nature and often lack analytical clarity, as they are used metaphorically rather than as part of a “conceptual armory” (Howie & Lewis, 2014, p. 136). While my aim is not to critique the authors – whose agendas may differ from the conceptualization of “geographical imaginaries” – this dispersion of similar, undertheorized notions complicates academic discourse. Ultimately, it leaves it to future authors to determine which concepts are sufficiently similar to be used interchangeably. For instance, the concept of “sustainable imaginary” is clearly defined as “a society’s understanding and vision of how resources are being used and should be used to ensure socio-environmental reproduction” (Cidell, 2017, p. 171). Another source that employs this term, suggests, however, that environmental imaginaries can have two meanings: first, “stories that are told about environmental issues, allowing analysis of how changes are attributed as positive or negative”, and second, “the ways in which environmental conditions are often discussed in relation to other issues, highlighting the embeddedness of environmental concerns within broader power relations, histories, and contexts” (Harris, 2011, p. 193).

The lack of a precise definition can be both a drawback and an opportunity for theoretical exploration. For instance, Nick Lewis, co-author of an influential theoretical article on geographical imaginaries (Howie & Lewis, 2014), uses the terms “spatial” and “geographical” imaginaries interchangeably in his earlier article focused on national branding (Lewis, 2011). He distinguishes between “cultural,” “environmental,” and “economic” imaginaries, providing examples such as reputations for reliability, quality, consistency, prompt payment, and trustworthiness (Lewis, 2011, p. 270). In Lewis’s article, “geographical imaginaries” is conceptualized as a broad term with several subtypes related to various domains, including culture, environment, economy, and others. While these subtypes highlight specific social domains, the overarching reference remains the core concept of geographical imaginaries. This understanding, although only implicitly presented in Lewis’s work, helps mitigate the excessive fragmentation of the concept. A notable advantage is that it allows for the exploration of the different shades and meanings of “geographical imaginaries.”

The focus on the range of imaginaries enabled me to distinguish between “macro” imaginaries, which are evident in public discourse, and “micro” imaginaries, which can be traced in individual narratives. This criterion is crucial, as the epistemological stance from which knowledge is produced can significantly influence the content of these imaginaries. The primary implication of this finding is methodological. Since geographical imaginaries are produced at various social levels, it is crucial to study them using a range of materials – from individual reflections to media images, public policies, and even meta-narratives embedded in literature, film, and drama. These levels can either complement or contradict one another. What is particularly significant is the intersection between micro-level imaginaries and the mezzo and macro levels, which also warrant careful examination.

The three levels of imaginaries correspond to the disciplinary affiliations of the students of geographical imaginaries and the scope of the articles. Micro-level imaginaries are most frequently discussed by sociologists and social geographers. Within this category, as in the overall pool of articles, geography remained the most common disciplinary affiliation, accounting for 40% of the articles, while sociology constituted a significant 28%. In contrast, on the macro scale, geographers authored 57% of articles, while sociologists contributed only 11%. Furthermore, mezzo- and macro-level analyses are more typical of political scientists, who almost never contribute to the understanding of micro-level imaginaries.

Similarly, society is the main topic in sources focused on the micro-scale (80% of articles, 20 out of 25), but its significance declines at the mezzo level (9 out of 31 articles, or 29%) and even further at the macro level (5 out of 44 articles, or 11%). In contrast, topics such as politics and the concept of the image itself become more prominent at higher levels of analysis. At the macro level, analyses are more likely to focus on images themselves or branding, such as the marketing value of Lapland’s imaginary (Herva et al., 2020).

While discussing these results, it is important to consider two limitations of the study. First, the analysis did not account for various conceptual alternatives mentioned above (such as “spatial imaginaries”) in order to focus on the details of a single notion – its history, evolving definitions, and disciplinary impact. Second, certain articles were deliberately excluded from the analysis, particularly historical studies (e.g., those focused on colonialism in the context of the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference) and media studies that primarily analyze media texts themselves (e.g., the depiction of Paris in Hollywood-inspired Maghrebi-French narratives). Although this decision limited the scope of the analysis, it allowed me to examine articles that were methodologically aligned with interview material, policy analysis, or analyses of media that discussed social realities, such as cartoons analyzed in the context of the Arab Spring.

7 Conclusion

The meta-analysis suggests that the term geographical imaginaries is not used consistently across the analyzed article. The issue lies not only in the relative rarity of clear definitions but also in the lack of consensus on whether geographical imaginaries should be treated as a well-defined concept rather than a commonsensical notion. While it is not always necessary to define the term explicitly – especially when it is not central to the study, as was often the case – the problem arises when imaginaries are used more as a catchphrase than as an analytical concept.

The answer to the second research question – concerning the theoretical frameworks employed in the conceptualization of geographical imaginaries – is closely linked to the first. The diverse theoretical underpinnings of geographical imaginaries reflect variations in research contexts, analytical scales, and the specific phenomena under investigation, as previously discussed. The analysis indicates that scholars investigate geographical imaginaries across a broad spectrum – from micro-level imaginaries rooted in individual experience to macro-level imaginaries embedded in global public discourse. The topics addressed range from social phenomena, places, and spaces to brands, landscapes, health, and public security.

Given the lack of a shared conceptual foundation, such as the one proposed by Howie and Lewis (2014), a wide array of often incompatible theoretical perspectives appears across the literature. Ideally, if geographical imaginaries were understood in the generalized sense proposed by Howie and Lewis – as mental representations that both shape and are shaped by human action, or alternatively, as structures of meaning that both inform and are informed by human action – the concept could be meaningfully applied across a range of disciplines. This concept serves as a general framework – flexible, yet not contradictory – and does not require an explicit definition in every instance. While a universal definition of geographical imaginaries may not be necessary, the general understanding proposed by Howie and Lewis (2014) offers a promising conceptual starting point. Treating geographical imaginaries as an analytical rather than a commonsensical term could lead to more rigorous theoretical reflection and, consequently, deeper insights into the phenomena it seeks to explain.

Despite the terminological ambiguity, the notion remains valuable for deepening our understanding of diverse cultural phenomena, as demonstrated by contributions from multiple fields. The wide applicability of the concept suggests its utility for scholars in human geography, sociology, migration studies, political science, and beyond. Moreover, there is still room to apply this framework to emerging areas of inquiry. For instance, the history of ideas could benefit from considering the imaginaries within which certain ideas are generated or transferred across borders (Abriszewski, 2016), while migration studies might further explore the imaginary dimension of practices such as medical tourism (Horsfall, 2019).

-

Funding information: This research was funded in whole by the National Science Centre, Poland [grant number: UMO-2023/50/E/HS6/00189].

-

Author contribution: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Abriszewski, K. (2016). Nauka w walizce. Zagadnienia Naukoznawstwa, 52(1), 87–112.Search in Google Scholar

Arnaldi, S. (2014). Exploring imaginative geographies of nanotechnologies in news media images of Italian nanoscientists. Technology in Society, 37, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2013.10.003.Search in Google Scholar

Arnall, A., & Hilson, C. (2023). Climate change imaginaries. Political Geography, 102, Article 102839. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102839.Search in Google Scholar

Aru, S. (2023). ‘Battleship at the port of Europe’: Italy’s closed-port policy and its legitimizing narratives. Political Geography, 104, 102902. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102902.Search in Google Scholar

Aschenbrenner, M. (2023). The political ecology of a diverse urban ethics of marine stewardship in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. In R. Acosta, E. Dürr, M. Ege, U. Prutsch, C. van Loyen, & G. Winder (Eds.), Urban ethics as research agenda (pp. 56–78). Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003346777-4.Search in Google Scholar

Balogh, P., Gál, Z., Hajdú, S., Rácz, Sz., & Scott, J. W. (2022). On the (geo)political salience of geographical imaginations: A Central European perspective. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 63(6), 691–703. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2022.2142146.Search in Google Scholar

Bergesio, N., & Bialasiewicz, L. (2023). The entangled geographies of responsibility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 41(1), 33–55. doi: 10.1177/02637758221137345.Search in Google Scholar

Blecha, J., & Leitner, H. (2014). Reimagining the food system, the economy, and urban life: New urban chicken-keepers in US cities. Urban Geography, 35(1), 86–108. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2013.845999.Search in Google Scholar

Borie, M., & Fraser, A. (2023). The politics of expertise in building back better: Contrasting the co-production of reconstruction post-Irma in the Dutch and French Caribbean. Geoforum, 145, Article 103813. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103813.Search in Google Scholar

Bridge, G. (2001). Resource triumphalism: Postindustrial narratives of primary commodity production. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 33(12), 2149–2173. doi: 10.1068/a33190.Search in Google Scholar

Bruun, J. M., & Medby, I. A. (2014). Theorising the thaw. Geography Compass, 8, 915–929. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12189.Search in Google Scholar

Bürkner, H.-J., & Scott, J. W. (2019). Spatial imaginaries and selective in/visibility. European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(1), 22–36. doi: 10.1177/0969776418771435.Search in Google Scholar

Cangià, F., & Zittoun, T. (2020). Exploring the interplay between (im)mobility and imagination. Culture & Psychology, 26(4), 641–653. doi: 10.1177/1354067X19899063.Search in Google Scholar

Cidell, J. (2017). Sustainable imaginaries and the green roof on Chicago’s City Hall. Geoforum, 86, 169–176.10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.09.016Search in Google Scholar

Featherstone, D. (2022). Pre-national transnationalism and translocalism. In B. S. A. Yeoh & F. L. Collins (Eds.), Handbook on transnationalism (pp. 30–44). Edward Elgar Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2018). A guide to qualitative meta-synthesis. Routledge.10.4324/9781351212793Search in Google Scholar

Ginnerskov-Dahlberg, M. (2021). In search of a ‘normal place’. The geographical imaginaries of Eastern European students in Denmark. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2021.1954495.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, D. (1994). Geographical imaginations. Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, D. (2009a). Geographical imaginary. In D. Gregory, R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, & S. Whatmore (Eds.), The dictionary of human geography (5th ed., p. 282). Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, D. (2009b). Geographical imagination. In D. Gregory, R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, & S. Whatmore (Eds.), The dictionary of human geography (5th ed., pp. 282–285). Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, D. (2009c). Imaginative geographies. In D. Gregory, R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, & S. Whatmore (Eds.), The dictionary of human geography (5th ed., pp. 369–371). Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Grubbauer, M. (2014). The office tower as socially classifying device in Vienna. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38, 336–359. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12110.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, C. (2017). 100% pure neoliberalism: Brand New Zealand, new thinking, new stories, inc. In L. White (Ed.), Commercial nationalism and tourism: Selling the national story (pp. 105–125). Channel View Publications.10.2307/jj.22730676.12Search in Google Scholar

Harris, L. (2011). Salts, soils and (un)sustainabilities? Analyzing narratives of environmental change in Southeastern Turkey. In D. Davis & E. Burke III (Eds.), Environmental imaginaries of the middle east (pp. 192–217). University of Ohio Press.Search in Google Scholar

Herva, V. P., Varnajot, A., & Pashkevich, A. (2020). Bad Santa: Cultural heritage, mystification of the Arctic, and tourism as an extractive industry. The Polar Journal, 10(2), 375–396. doi: 10.1080/2154896X.2020.1783775.Search in Google Scholar

Hong, G. (2020). Islands of enclavisation: Eco-cultural island tourism and the relational geographies of near-shore islands. Area, 52, 47–55.10.1111/area.12521Search in Google Scholar

Horsfall, D. (2019). Medical tourism from the UK to Poland: How the market masks migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(20), 4211–4229. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1597470.Search in Google Scholar

Howie, B., & Lewis, N. (2014). Geographical imaginaries. New Zealand Geographer, 70(2), 131–139. doi: 10.1111/nzg.12051.Search in Google Scholar

Hunter, H., & Nelson, E. (2021). Out of place in outer space?: Exploring orbital debris through geographical imaginations. Environment and Society, 12, 227–245. doi: 10.3167/ares.2021.120113.Search in Google Scholar

Ibrahim, Y., & Howarth, A. (2016). Constructing the Eastern European other: The horsemeat scandal and the migrant other. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 24(3), 397–413. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2015.1135108.Search in Google Scholar

Jeleff, M., Haddad, C., & Kutalek, R. (2023). Between superimposition and local initiatives: Making sense of ‘implementation gaps’ as a governance problem of antimicrobial resistance. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 4, Article 100332. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100332.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, X., Calas, M., & English, A. (2022). Constructing the “self”? Constructing the “place”? A critical exploration of self-initiated expatriation in China. Journal of Global Mobility, 10(4), 416–439.10.1108/JGM-06-2021-0064Search in Google Scholar

Kearns, R., O'Brien, G., Foley, R., & Regan, N. (2015). Geography and imagination(s). New Zealand Geographer, 71, 159–176. doi: 10.1111/nzg.12100.Search in Google Scholar

Koch, N. (2016). Is nationalism just for nationals? Political Geography, 54, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.09.006.Search in Google Scholar

Le Heron, R., Lewis, N., & Harris, A. (2012). Contradictory practices and geographical imaginaries in the rolling out of education for sustainability in Auckland, New Zealand secondary schools. In M. Robertson (Ed.), Schooling for sustainable development (pp. 63–82). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2882-0_5.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, N. (2011). Packaging political projects in geographical imaginaries. In A. Pike (Ed.), Brands and branding geographies (pp. 264–288). Edward Elgar.10.4337/9780857930842.00026Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, K. (2018). The ‘Buen Vivir’ and ‘twenty-first century socialism’. Journalism Studies, 19(8), 1160–1179. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1264273.Search in Google Scholar

Lulle, A. (2020). Cosmopolitan encounters. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 41(5), 638–650. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2020.1806800.Search in Google Scholar

Mak, S., & Thomas, A. (2022). Steps for conducting a scoping review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(5), 565–567. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1.Search in Google Scholar

Maraud, S., & Guyot, S. (2016). Mobilization of imaginaries to build Nordic Indigenous natures. Polar Geography, 39(3), 196–216. doi: 10.1080/1088937X.2016.1184721.Search in Google Scholar

McNeill, C. (2023). Deterritorialized threats and the ‘territorial trap’. Alternatives, 48(2), 170–188. doi: 10.1177/03043754231163219.Search in Google Scholar

Menet, J. (2020). Entangled mobilities in the transnational salsa circuit: The Esperanto of the body, gender and ethnicity. Routledge.10.4324/9781003002697Search in Google Scholar

Moore, C., & Purcell, D. (2021). The imaginative geographies of Emad Hajjaj’s Arab Spring cartoons. The Arab World Geographer, 24(3), 182–204. doi: 10.5555/1480-6800.24.3.182.Search in Google Scholar

Mustafa, D., & McCarthy, J. (2020). Terrorism. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography (2nd ed.) (pp. 233–238). Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10493-7Search in Google Scholar

Nash, S. L. (2023). The perfect (shit)storm. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 42(6), 941–957. doi: 10.1177/23996544231216015.Search in Google Scholar

Neubauer, J. (2024). Envisioning futures at new destinations. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 50(12), 3049–3068. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2024.2305281.Search in Google Scholar

Oksamytna, K. (2023). Imperialism, supremacy, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Contemporary Security Policy, 44(4), 497–512. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2023.2259661.Search in Google Scholar

Ould Moctar, H. (2022). The constitutive outside: EU border externalisation, regional histories, and social dynamics in the Senegal River Valley. Geoforum, 155, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.09.009.Search in Google Scholar

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, Article n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.Search in Google Scholar

Phelps, N. A., Bunnell, T., & Miller, M. A. (2011). Post-disaster economic development in Aceh. Geoforum, 42(4), 418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

Planey, D. (2020). Policy cohesion and post-recession economic imaginaries: manufacturing discourse in the Chicago metropolitan region. Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(2), 258–275. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2019.1703798.Search in Google Scholar

Riano, Y., & Baghdadi, N. (2007). Je pensais que je pourrais avoir une relation plus égalitaire avec un Européen: Le rôle du genre et des imaginaires géographiques dans la migration des femmes. Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 26(1), 38–53. doi: 10.3917/nqf.261.0038.Search in Google Scholar

Rivera-Amarillo, C., & Camargo, A. (2019). Zika assemblages: Women, populationism, and the geographies of epidemiological surveillance. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(3), 412–428. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1555518.Search in Google Scholar

Robins, D. (2022). Immobility as loyalty: ‘Voluntariness’ and narratives of a duty to stay in the context of (non)migration decision making. Geoforum, 134, 22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.05.017.Search in Google Scholar

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.Search in Google Scholar

Saunders, R. (2014). Mediating New Europe-Asia: Branding the post-socialist world via the Internet. In J. Morris, N. Rulyova, & V. Strukov (Eds.), New media in New Europe-Asia (pp. 143–166). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Schech, S. (2017). International volunteering in a changing aidland. Geography Compass, 11(3), Article e12351. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12351.Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, M. (2020). Mental mapping and multinational migrations: A geographical imaginations approach. Geographical Research, 58(4), 388–402. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12435.Search in Google Scholar

Trandafoiu, R. (2022). The politics of migration and diaspora in Eastern Europe: Media, public discourse and policy (1st ed.). Routledge.10.4324/9781003055242-1Search in Google Scholar

Walshe, R., Morin, J., Donovan, A., Vergara-Pinto, F., & Smith, C. (2023). Contrasting memories and imaginaries of Lonquimay volcano, Chile. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 97, Article 104003. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.104003.Search in Google Scholar

Watkins, J. (2015). Spatial imaginaries research in geography: Synergies, tensions, and new directions. Geography Compass, 9(10), 508–522. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12228.Search in Google Scholar

Watson, A. (2024). The production of ‘From Our Own Correspondent’ on BBC Radio 4: A popular geopolitical analysis. Area, 56(1), Article e12918. doi: 10.1111/area.12918.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, M. W. (2010). Gender and geography II: Bridging the gap — feminist, queer, and the geographical imaginary. Progress in Human Geography, 34(1), 56–66. doi: 10.1177/0309132509105008.Search in Google Scholar

Wydra, D. (2020). Between normative visions and pragmatic possibilities: The European politics of state recognition. Geopolitics, 25(2), 315–345. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2018.1556643.Search in Google Scholar

Wyndham, C. (2014). Reconstructing Afghan identity: Nation-building, international relations and the safeguarding of Afghanistan’s Buddhist heritage. In P. Basu & W. Modest (Eds.), Museums, heritage and international development. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, W., & Thill, J. C. (2019). Mesoscale structures in world city networks. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(3), 887–908. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1484684.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction