Abstract

The aim of this article is to elaborate on the problem of traditional metaphors used to describe the beauty of Indonesian women. The traditional metaphors used to describe the beauty of Indonesian women originate from nature and show specific aspects of beauty, both physically and non-physically. Also, under the modern Western-dominated global beauty discourse and concepts, traditional forms and concepts of beauty are re-elevated and given new value to enrich global knowledge and culture. Through the ethno-semiotic method, the study shows that the traditional forms and concepts of beauty regarding Indonesian women cannot be separated from natural occurrences. Description based on natural objects and phenomena is not just a matter of metaphorical language as a rhetorical means to describe beauty but forms a significant relationship with the natural and cultural characteristics of body beauty. The union of the body and nature creates a powerful energy that positions women as subjects of nature, culture, and social life. This finding allowed for the development of a new discipline – the ecology of beauty.

1 Introduction

Beauty is a discourse. As a discourse, beauty becomes both a subject and a never-ending field of discussion. For this reason, the idea of beauty cannot be “fixed.” No single definition of beauty can serve as a universal standard. Something is deemed beautiful only when it serves to provide a pleasing quality, which is inherently subjective (Heller, 2012, p. 61). Within this context, the meaning of beauty is constantly debated. It remains in a perpetual cycle of power dynamics and contestations over identity, reflecting the nature of discourse itself (Foucault, 1997, pp. 27–28).

In this ongoing debate, two opposing views often stand out: the social constructionist view on one side, and the evolutionary perspective on the other. Social constructionists see beauty as a myth, something politically created or shaped. One prominent voice within this perspective is Naomi Wolf, a feminist author. In her book The Beauty Myth: How Images of Female Beauty are Used Against Women, she argues that

Beauty is a currency system like the gold standard. Like any economy, it is determined by politics, and in the modern age in the West it is the last, best belief system that keeps male dominance intact. In assigning value to women in a vertical hierarchy according to a culturally imposed physical standard, it is an expression of power relations in which women must unnaturally compete for resources that men have appropriated for themselves. (Wolf, 2002, p. 12)

Meanwhile, the evolutionary perspective offers a view that contrasts with the previous one. According to Gottschall (2008), evolutionary thinkers believe that beauty has developed over a long period and can be found in almost every culture worldwide. In this context, beauty is also closely linked to biological factors. Gottschall, who studied the relationship between female beauty and male attractiveness in 90 samples of folk tales from around the world, support the evolutionary view. They concluded that

These results strongly support the evolutionary prediction that greater emphasis on female physical attractiveness will be the rule across human culture areas; it undercuts the constructivist prediction…indicates that the main elements of the beauty myth are not myths: there are large areas of overlap in the attractiveness judgments of diverse populations, and cross-cultural emphasis on physical attractiveness appears to fall primarily, and reliably, upon women. (Gottschall, 2008)

According to evolutionary thinkers, the concept of female beauty varies across cultures and changes over time (Eco, 2004, pp. 8–15; Liem, 2022, pp. 8–21). Beyond that, beauty can also transcend cultural boundaries and take on a transnational nature as it evolves (Saraswati, 2022, p. 2). However, from the perspective of discourse studies, those who control the narrative ultimately dominate, and in this case, it is the West. As a result, in general reality, beauty has been categorized as being associated with fair skin. This hegemony has heavily influenced beauty that women often feel they must be fair-skinned to be considered beautiful (Prabasmoro, 2003, pp. 91–92; Yulianto, 2007, pp. 13–37). Furthermore, this notion of beauty is centered solely on physical appearance. In other words, beauty has become about the visible, surface-level attractiveness of the body (Saraswati, 2022, p. 7). This kind of beauty is what many desire (Sartwell, 2004). From a semiotic perspective, beauty can be seen as an artificial sign (Piliang, 2003, p. 56). As an artificial sign, beauty is a constructed entity – a created image.

Ultimately, the view of beauty based on the social construction perspective also holds its own truth.

White skin, as the foundation of hegemonic beauty standards, has become the “raw material” for capitalist production. In this context, the “ideology of whiteness” operates like an unstoppable force, and it is continuously driving the system forward (Hokheimer, 1972, p. 77). Referring to Althusser (1984, pp. 50–51), this hegemonic beauty standard constantly pressures and influences women around the world. The desire to achieve fair skin is pursued in various ways. Whitening creams and serums are produced and consumed to excessive levels. Ultimately, women’s bodies – seen as the bearers of beauty – become the victims. Here beauty becomes a pain. This pain is not only ideological, caused by hegemonic power or identity politics, but also physical. The use of whitening products often leads to complex side effects (Agustina & Suryaningsih, 2016; Radzi & Noordin, 2022; Sommerlad, 2022; Wahil et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2022).

This situation has created a disconnect between women’s beauty and nature. Yet, one of the narratives about women is their close connection to the natural environment (Ponda, 2021, p. 18; Shamban, 2019). History shows that during the hunting era, while men went into the forest to hunt, women stayed near their homes, farming around caves, tree houses, or water sources. This suggests that men tended to “take what already existed in nature,” while women nurtured and cultivated the land, making it productive. Through farming, women formed an “emotional bond” with nature. It is not surprising, then, that women are often symbolized as “Mother Earth” (Toynbee, 1976, p. 775). Along the same lines, it makes sense that the phrase “natural beauty” has become a metaphor for the attractiveness of women’s appearance.

Natural beauty is also synonymous with beauty as it relates to local cultural values (Tilaar, 2017). This is because nature is a space where the development of culture grows. Different worlds give birth to different cultures, which makes natural beauty become beauty in cultural diversity. Therefore, as mentioned at the beginning of this article, the forms and definitions of beauty also differ in direct relation to this cultural diversity. In the Hebrew language and culture, for example, the equivalent word for beauty is yafa, which means “to shine”; in Greek, ke kalon, meaning “idea”; in Sanskrit sundara, which means “chastity”; Japanese wabi-wabi, which translates to “humility” or “imperfection”; and in Navazo, hozo, means “health” or “harmony” (Sartwell, 2004). This shows that beauty is not just about physical appearance but also involves deeper, non-physical qualities. Beauty is a collection of meanings, encompassing both the tangible and the intangible.

Returning to the idea of hegemonic beauty, its peak impact is not just separating women’s beauty from nature but also destroying or erasing nature itself. From Peirce’s semiotics perspective (Short, 2007, p. 222), this can be seen as an indexical sign of environmental destruction. In other words, the destruction of natural beauty goes hand in hand with the destruction of nature. Unfortunately, the exploitation of nature has been increasing, with ecological damage becoming a major issue over the past century.

As Lintott (2010) explains, this situation should be a significant focus of ecofeminism. Ecofeminism, in this context, should not just center on theoretical discussions, ideas, or activism regarding women’s exclusion from policies on natural resource management and ecological crises (Hunga, 2013, pp. xiii–xiv). It should also address how women’s bodies have been commodified and disconnected from their natural roots. This topic needs to be explored further in cultural discussions. In cultural terms, the commodification of hegemonic beauty has caused women’s bodies to become overloaded with “signs” or meanings (Piliang, 2003, p. 58). This “overload” turns the body into something beyond its social and cultural essence (Synnott, 1993, pp. 1–2), making it overcultural – a condition linked to cultural damage. In relation to nature, cultural damage aligns directly with environmental destruction.

Based on those conditions, it is very important to elaborate more broadly and deeply on the themes of natural and cultural beauty with different perspectives. Nature’s relationship with women is not necessarily understood as a weakening (feminization) of nature and women at the same time (Gaard, 1993). Instead, we must more carefully identify that the relationship between the two is mutualistic in nature and that creates positive energy for both. A path in this direction is possible upon close reading. This is related to how the author examines the traditional beauty of Indonesian women, specifically three major ethnicities: Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau. We focus on the study of the relationship between beauty and nature-based language constructions as a reference.

In Indonesia, especially as relates to the three ethnicities studied in this article (Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau ethnic groups), it is common for the physical form of a woman’s beauty to be described in relation to nature (flora and fauna). One might simply assume that this commonality occurs because Indonesia is an archipelagic country with very rich biodiversity (Vlekke, 2008; Wallace, 2009). However, the problem does not stop there. The relationship between language and nature brings this study into broader and more complex historical and cultural constructions. It will be proven that the traditional beauty of Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women is not purely physical appearance, but also an eternal cultural or even spiritual essence. Because of this, the discussion of this topic becomes more interesting and important. It has a significant urgency value for the development of knowledge about the essence of beauty in relation to the value of cultural diversity. In this context, this study can simultaneously contribute to addressing issues of beauty in particular and women in general caused by hegemony-capitalism on the one hand and ecological crisis on the other.

2 Methods

2.1 Ethnosemiotics of Beauty

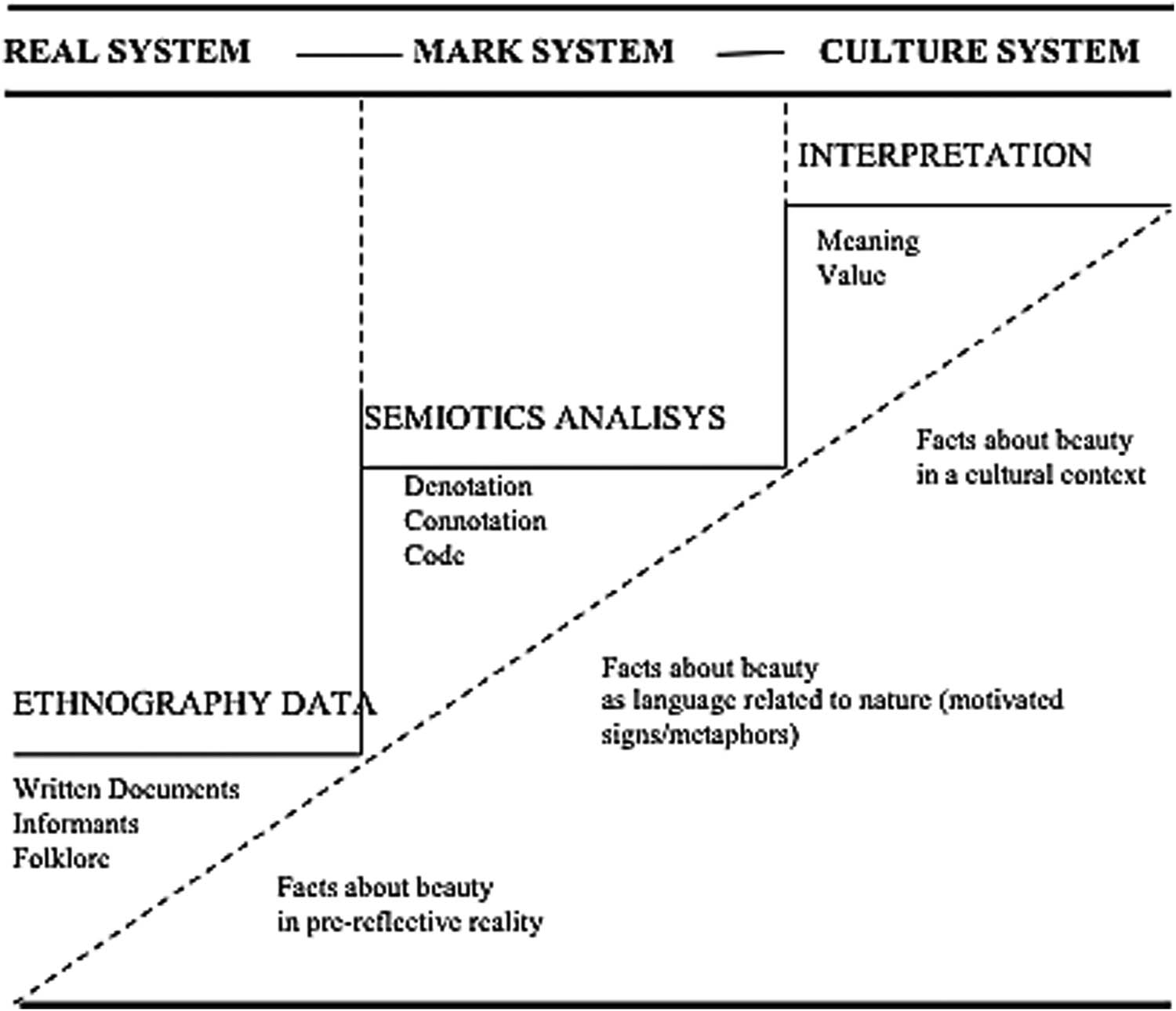

This study integrates two methods, namely, ethnography and semiotics, and is called ethnosemiotics (Herzfeld, 1983; MacCannell, 1979). Ethnosemiotics is a convergent method that was originally based on anthropology; however, in its development, ethnosemiotics is also used in various fields (Acuña, 2019; Faudree, 2012; Fiske, 1990; Herman & Moss, 2007; Kozin, 2014).

As a convergent method, ethnography and semiotics are theoretically one unit. However, at the technical level in this article, ethnography is more focused on the collection of empirical data from sources in the field. The ethnographic data referred to are not entirely derived from oral sources but also from various written documents. In other words, data on the traditional beauty of women among the Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau ethnic groups were extracted from written documentation, oral folklore, community behavior, informal dialogue with informants, and others (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007; Spradley, 1979).

Furthermore, ethnographic work synergizes with semiotic interpretation. The ethnographic data are treated as a set of semiotic signs, and in interpreting that data, we use Barthes’ semiotics (1985). According to Barthes (1985), the data regarding the description of beauty are understood as a way reality is transferred into two levels of language, i.e.,

At the first level, there is a transfer of “real” reality into language reality which is called “denotation” (Barthes, 1985). At this level, the meaning that emerges is literal (denotation). The “real” reality that is denoted in the construction of traditional Indonesian women’s beauty is generally the reality of nature. Thus, the sign that appears is a sign that is motivated by or refers to nature (Barthes, 1985).

At the second level, the sign of motivation rises to the level of connotation (Barthes, 1985), namely, a sign whose reference meaning is intertwined with culture. At this level, motivated signs lead to the formation of the community codes that belong to them – in this case, the context from which our informants come.

Regarding codes, Barthes (2002) formulates five generally accepted codes, namely, hermeneutic (codes that generate tension or curiosity), proairetic (narrative codes that are causal), semantic (codes with connotative messages), symbolic (codes with contradictory, antithetical, or discontinuous messages), and referential (cultural codes or collective views, often in the form of proverbs). At the practical level, these codes are not always verbal (textual) codes, but can also be visual, audio, behavioral, etc. These codes are also not always fully present in the object being analyzed. The important thing to emphasize is that the analysis of the language codes of beauty is a series that are interconnected and integrated in the ethnosemiotic method. We illustrate these methodological relationships in a chart depicted in Figure 1.

Relationship chart and ethnosemiotic study strategy for traditional beauty of Indonesian women (Source: Authors).

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Results

As already mentioned, this study of the traditional beauty of Indonesian women is focused on the Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau ethnicities. Aside from the fact that the three are major ethnic groups in Indonesia, they also have a unique relationship with each other in the history of Indonesian culture. The first two ethnic groups, namely, Sundanese and Javanese, live on the same island, namely, Java. The contact between the two ethnicities can be seen in the following ways:

First, in several areas such as Cirebon, Indramayu, Banten, and Pangandaran, the contact appears explicit in the mixing of the languages of the two ethnicities, giving rise to separate dialects which can be called neither Javanese nor Sundanese (Indira et al., 2019; Robbiah, 2022; Zein et al., 2022).

Third, they both make reference to the same mythological goddess, namely, Dewi Sri (Javanese) and Nyai Pohaci (Sundanese) (Aminoedin, 1986).

Meanwhile, Minangkabau is an ethnic group that has the character of wandering (Naim, 1973), and the island of Java is their main overseas destination. Migration to Java was common before Indonesia’s independence, and during the independence movement, many of the important figures on the island of Java were from the Minangkabau ethnic group. Naim (1980) refers to this historical fact as the domination of M (Minangkabau) culture which later, during the reign of Soeharto, was displaced by J (Javanese) culture. This strongly supports the occurrence of cultural encounters between the Minangkabau and both the Javanese and Sundanese people. Literary works written by authors from the Minangkabau region such as Hamka (1984) and Rusli (2013) show the intensity of their encounters with the people of Java (both the Javanese and Sundanese). The Javanese author, Umar Kayam, wrote the sociological romance novel “Para Priyai” (volume 1 and volume 2), which tells of how the meeting of these two cultures took place in a very intimate way through the marriage of their characters (Kayam, 1991, 1999). Marriages between Minangkabau people and the Javanese or Sundanese continue to be common to this day, resulting in both acculturation and cultural assimilation (Muchtar, 2015; Muluk & Murniati, 2007; Yulita et al., 2021).

These cultural historical facts lead to the assumption that the traditional concept of women’s beauty in the Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau ethnic groups has something in common. The way they describe beauty based on nature supports this assumption. Table 1 contains related written document data.

As shown in Table 1, the physical form of traditional women’s beauty in the three ethnicities studied is described using objects found in nature (flora, fauna, and celestial bodies) as a means of comparison (using simile and metaphor). Every written document does not describe all parts of the body as a whole. However, all documents have ties to each other. The Panji Semirang Hikayat, for example, is a story that originally appeared and developed on Java, but later became part of the Malay Hikayat. Thus, these stories support one other, with natural metaphors as a common thread. Therefore, when the whole is combined, it forms a “metaphoric anatomy” of the body as a whole.

Description of traditional Indonesian beauty regarding Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women

| No. | Description | Source | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Sri Pramodyawarddhani, daughter of King Samaratungga, had extraordinary beauty. Her beauty was like the full moon (candramaso), her voice was melodious like the kalawinka / kalavinka bird, her steps were like a swan (gatih cahansat), she walked like a hungry tiger (macan luwe).” | Karangtengah Inscription (746 Shaka) (Tilaar, 2017) | Java |

| 2 | “Well, may your hair be long and soft as moss! May the hairs on your forehead and temples be like stamens. Your neck, may it be like the trunk of a Gading Coconut tree (Cocos nucifera var. eburnea). May your jaw be like a broken axe handle and your eyebrows like neem leaves. Your eyesight is beyond the sweetness of honey and sugar water. Your lips are like the cracked skin of a mangosteen and your teeth are white like Sridanta leaves. | Sri Tanjung Script, Pupuh V no. 174177. quoted from Aminoedin, (1986), with some editorial changes from researchers. | Java |

| May your eyelashes be like the stamens, your face the part of a durian. May your arms be like the nodding arms of the scales and your fingers smooth. May your breasts exceed the beauty of the gading coconut. Your waist is like the open blade of a machete. Your thighs are like planked roots, your feet are like those of a gazelle. | |||

| May your pelvis be a vessel in a beautiful shape, my granddaughter, your calf be like a fragrant pudak flower (Pandanaceae). May the soles of your feet, my granddaughter, be like the soles of ivory. Your body is padmanagara. If you walk, your steps are beautiful as if accompanied by a gamelan. | |||

| May your nails be like pearls, the gentleness of your body, my granddaughter, like the jewels of ivory. It is stunning to look at you. Your elegance is like all kind of flowers. Your beauty, my granddaughter, is the best in this world.” | |||

| 3 | “Pramodyawarddhani, the queen consort of Rakai Pikatan, the sixth king of the Medang Kingdom (Ancient Mataram), her way of walking was like a swan, her voice was like a turtledove, her eyes were like a deer’s eyes.” | Kayumwungan inscription (824 M) | Java |

| 4 | “The eldest named Tuan Putri Galuh Candra Kirana; was the daughter of the empress; her appearance was absolutely glorious, it was beyond words, her nose was like a single dasun , her eyes were like the eastern star, her eyelashes were curled, her fingers were like porcupine hairs. Her calves were like the bellies of rice paddy, her heels were like bird’s eggs, her cheeks were like puffs, her eyebrows were like spurs, her lips were like limes. It was difficult to tell more because there was nothing to find fault with.” | Muzizah & Ikram (2020) Hikayat Panji Semirang (Balai Poestaka, 1953) | Java-Minangkabau. The original story in this book comes from East Java, but was later translated into Malay with stories that were also adapted to the Malay culture. This was what later led to this story being collected in the Hikayat Panji Melayu |

| 5 | Rambut hideung meles, galing muntang, ombak banyu (shiny black hair, curly and wavy); pameunteunna ngadaun sereuh (the shape of his face is like a betel leaf), taar teja mentrangan (shining bright forehead), halis ngajeler paeh (eyebrows like dead jeler fish), soca cureuleuk, bulu soca carentik (sparkling eyes, curled eyelashes), damis ngagula sapasi sapertos katumbiri (cheeks like half of brown sugar, like a rainbow), pangambung uwung-uwungan, gado ngendog sapotong/sapasi, (chin like half an egg), lambey jeruk sapasi, (orange lips), waos gula gumantung (teeth that were like prolonged sugar but clean and bright). | Desiana & Dienaputra, 2019 | Sunda |

| 6 | “Her appearance was reddish yellow like sugarcane in Lalang, like grilled prawns, quite irresistible. Curly hair in three rolls, her ears were held back, eyelashes of ants waving (curled up), her nose was like a single dasun (garlic), her chin was like hanging cloud. Her cheeks were puffy, her lips were like limes, her eyebrows were shaped like spikes, her tongue was like a ripe paste; her calves were like the belly of rice paddy, her heels were like bird’s eggs, the feet were bent like thongs. Her shape was weak and slender, her sight was like lights dimming, the fingers were smooth with henna nails, the beauty was carried away as if painted and described.” | Kaba Sabai Nan Aluih (Sati, 1978, p. 17) | Padang, West Sumatra (Western part of Indonesia) |

| 7 | “How beautiful is this virgin child, when standing like that! It’s like a vulnerable merchant, who loves something, which is not easy to get. Her cheeks were puffy like hanging pauh (mango), the reddish colour from the shadow of her clothes and umbrella, getting redder from the heat of the sun. | Novel Siti Nurbaya by Marah Rusli (Rusli, 1974, p. 4) | Padang, West Sumatra |

| When she laughs, her cheeks are hollow, adding sweetness to her appearance; special because there is a black mole on her left cheek. The look in her eyes is calm and gentle, like a widow just waking up. Her nose is pointed, like a flower. Her lips are smooth, like a split ruby, and between those two lips her teeth are visible, closely lined up, like two rows of white ivory. Her chin is like bees hanging down, and on both sides of her ear lobes appear silver earrings, which are studded with large diamonds, which emit the light of dew. On her long neck, hanging on a fine gold chain, a symbol of caution, with a ruby-eyed gem. If she drinks, it is as if she imagines the water she drinks in her throat. Her voice is soft, like a longing reed, giving pain to those who hear it. Her chest is flat, her waist is slim. Her arm is encircled by snake bracelets, studded with a few diamonds that blaze with light. On the ring finger of her delicate left hand, there is a pearl ring, with big eyes.” | |||

| 8 | Tupak di diri Siti Jamilah, Lorong kapado dang rauik romannyo, sariklah pulo ka tandiangannyo, muko panuah bak bujua talua, hiduang mancuang bak dasun tungga, pipin nan bak pauah dilayang, bulu mato bak samuik baririang, daguaknya nan bak labah hinggok, langannyo bak lilin dituang, tumiknya bak talua buruang, batihnyo bak paruik padi, randah tidak tinggi pun tidak, sadang elok bapatutan. | Kaba Tuanku Lareh Simawang, Rajo Endah (1989, p. 15) | |

| (Look at Jamilah. Her features are incomparable. Her face is full like an egg, her nose is sharp like a single garlic, her cheeks are puffy like hanging pauh fruit (mango), eyelashes are like ants in a row, her chin is like bees hanging down, her arms are like burning candles, her heels are like bird’s eggs, her calves are like rice belly, neither low nor high, medium and beautiful to look at.) |

Furthermore, through searching for data in the field, empirical data have been found that generally confirm the data above. We summarize the data from several of these informants in the following descriptions and excerpts of conversations. (In accordance with our agreement with the informants, their identities are not included here.)

Informant 1, a 76-year-old woman and resident of Sleman, Bantul Regency, Yogyakarta (Javanese ethnicity)

Even at the advanced age of the informant, she still shows traces of her beauty in youth. She was slightly bent over, but she still looked tall for an Indonesian woman. “I used to be 172, you know, I don’t know now, hehehe,” she said in an informal conversation with us. She was very passionate about talking about women’s beauty. In the name of people’s evaluation of her, she tells her beauty.

“Lambeku iki, Ndo, jare wong mbiyen kaya pelem sing wis mateng, guluku kaya godhong gadung. Aku ora ngerti yen iku bener po ora. Tapi yo, seneng-seneng wae, hahaha.” (My lips, dear, were once said to be like ripe mangoes, and my neck like gadung leaves. I don’t know if that’s true or not. But, well, I’m happy anyway, hahaha.).

She also added, “Alisku njlarit rembulan nuju tanggal siji, tapi itu dulu, sekarang, yo, udah peot, hehehe” (My eyebrows are curved like the first/beginning of the month, but that was then, now they are wrinkled, hehehe). In addition, she said that beautiful women had slim calves like a locust, her nose was small but sharp, and her fingers were slender.

Informant 2, an 80-year-old woman living in Leuwi Liang, a village in the interior of West Java (Sundanese ethnicity)

When we met this informant, she was almost always in a state of indignation. Retirement means the chewing of betel nut (Areca catechu), lime, and gambier fruit (Rubiaceae) wrapped in betel leaves. This is a long-standing tradition and custom passed down from generation to generation. This custom specifically takes place on the island of Java (Raffles, 2019). Nyepah or also called nginang is done almost all day long. Chewing that is done continuously produces a blood-red liquid so that the lips become red. About this particular habit, this informant said:

“Nyeupah tos jadi kabiasaan emak ti bubudak, meureun ku sabab eta emak jadi panjang umur, nyeupah tos jadi ibadah keur emak mah, lain keur kasehatan jeung kageulisan wungkul” (“Nyepah” has been a habit of my mother since childhood. Perhaps because of that, my mother has a long life. For my mother, “nyepah” has become a kind of worship, not just for health and beauty.)

She admits to giving up the habit in an effort to maintain health and fitness. For her, giving up is also related to women’s beauty. She describes the beauty of women with the expression:

“Mojang geulismah pamenteuna ngadaun seureuh, rambutna galing muntang kawas ranggeuyan buah jambe, bitisna kawas tangkal pare anu rek buahan” (The beautiful girl has a face like a betel leaf, curly hair hanging like a string of “buah mayang” (a type of fruit), and her calves are like a rice plant that is about to bear fruit.)

On another occasion she added:

“Awewe dulang tinande kudu tuhu ka alam. Awewe nu kitu geulis lain jijigaan. Awakna jangkung lenjang. Halisna ngajeler paeh, gadona endog sapotong, bujurna siga papanting, biwirna kuwung-kuwungan, pipina duren sapasi, leungeun letik ngagondewa, waosna kawas gula gumantung” (The woman must submit to nature. A truly beautiful woman (not just superficially beautiful) is tall and slender. Her eyebrows are like dead jeler fish (Nemacheilus chrysolaimos), her chin is like half an egg, her waist is like a wasp’s, her lips are red like a rainbow, her cheeks are like a slice of durian, her arms are like a bow, and her teeth are shiny and neat like half-cooked brown sugar.)

Informant 3, a 45-year-old female who lives in Bukit Tinggi, West Sumatra (Minangkabau ethnicity)

This informant is a teacher at a junior high school. As a teacher, of course, she must always look beautiful but still be polite to her students and treat them with dignity. Generally, women of her age care for their beauty by using modern beauty products. However, she does not like that. She prefers traditional ingredients from nature, including the consumption of herbs. Bunda Kanduang and Sabai Nan Aluih are two female figures in Minangkabau mythology who have become her idols. “Women must be beautiful but not weak,” she said in conversation. Furthermore, she describes the beauty of women as follows.

“Perempuan cantik itu, wajahnya bersinar bak bulan purnama empat belas, matanyapun bersinar, bulu matanya semut beriring, dagunya bak labah hinggok, bibirnya asam seulas, pinggang ramping, langannyu bak lilin dituang, betisnya bak paruik padi, tumitnya bak telur burung. Jika ia berjalan bagai itik pulang patang, lebih surut dari maju.”

(The beautiful woman’s face shines like a full moon on the fourteenth day. Her eyes sparkle, and her eyelashes are neatly arranged like a line of ants. Her chin is like a resting swan, her lips are sour, her waist is slim, her legs are like wax poured into a mold, her calves are like rice paddies, and her heels are like bird eggs. She moves back more than forward when she walks, like a duck returning home.)

“Perfect, yo. But, there are no women like that now, hehehe”, she concluded.

As with data from written documents, oral data from these informants are also only partial. The interesting thing is that the information from the informants confirms that of the written-documents, yet none of the informants who provided information had ever read any of those documents. This fact seems to confirm that the construction of traditional beauty related to nature has become shared knowledge in Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau societies.

In Table 2, we identify in more detail and brief a combination of two types of data on the description of the traditional beauty of Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women, based on these natural objects or varieties.

Nature-based construction of traditional beauty in Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau ethnicities

| Parts of body | Natural varieties for comparison |

|---|---|

| Skin/skin color |

|

| Hair |

|

| Eyebrows |

|

| Eyelashes |

|

| Face |

|

| Cheeks |

|

| Lips |

|

| Teeth |

|

| Breasts |

|

| Mouth |

|

| Tongue |

|

| Chin |

|

| Eyes |

|

| Nose |

|

| Neck |

|

| Arms |

|

| Fingers |

|

| Finger nails |

|

| Hips |

|

| Waist |

|

| Thighs |

|

| Calves |

|

| Heel |

|

| Legs |

|

| Sole |

|

| Voice |

|

| Gait |

|

4 Discussion

4.1 Nature as a Source of Metaphors used to Describe Beauty

Nature has become a source for the construction of language that describes the physical form of beauty. Referring to Barthes (2002), the concept of female body beauty is denoted by nature. We call this process a metaphor, namely, a process that relates (compares) the female body as one sign with nature as another sign (Guattari, 2000; Levesque, 2016). Because nature has a position as the reality being referred to, it can be stated that nature is the source of the metaphors used to describe the traditional beauty of Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women.

The nature-based metaphors for describing the traditional beauty of the female body can be divided into two categories, namely, categories based on similarity in form and those based on similarity in nature or character. Tables 3 and 4 present these two categories along with their object forms or natural varieties.

Categories of metaphorization based on similarity in shape

| Parts of body | Metaphor source | |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Forms of natural varieties | |

| Hair | Unraveled Mayang (young palm fruit) (Arenga pinnata) |

|

| Eyebrows | Mimba leaf (Azadirachta indica) |

|

| Jeler fish (Nemacheilus chrysolaimos) |

|

|

| Crescent moon |

|

|

| Spurs |

|

|

| Eyelashes | The ants walk in a row |

|

| Nose | Jasmine |

|

| Garlic |

|

|

| Face | Betel leaf (Piperaceae) |

|

| Bodhi leaf (Ficus religiosa) |

|

|

| Chin | Hanging bees (Apidae-Hymenoptera) |

|

| Half an egg |

|

|

| Lips | Rainbow |

|

| Ears | Giyanti flower |

|

| Breasts | Twin gading coconut (the newly grown coconut fruit which is yellowish white) |

|

| Waist | Wasp (Vespidae) |

|

| Calves | Budding rice stalks (rice buds beginning to grow in them) |

|

| Fragrant Pudak leaf (Pandanus tectorius) |

|

|

Categories of metaphorization based on similarities in nature or character

| Parts of body | Metaphor source | |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Forms of natural varieties | |

| Hair | Moss |

|

| Cricket feathers |

|

|

| Eyebrows | Stamens |

|

| Skin | Half cooked prawns |

|

| Sugarcane |

|

|

| Cheeks | Durian fruit (Durio) |

|

| Lips | Ripe mango (Mangifera indica) |

|

| Rainbow |

|

|

| Tamarind |

|

|

| Cracked pomegranate |

|

|

| Eyes | The eyes of a baby deer |

|

| Tongue | Ripe mempalam fruit |

|

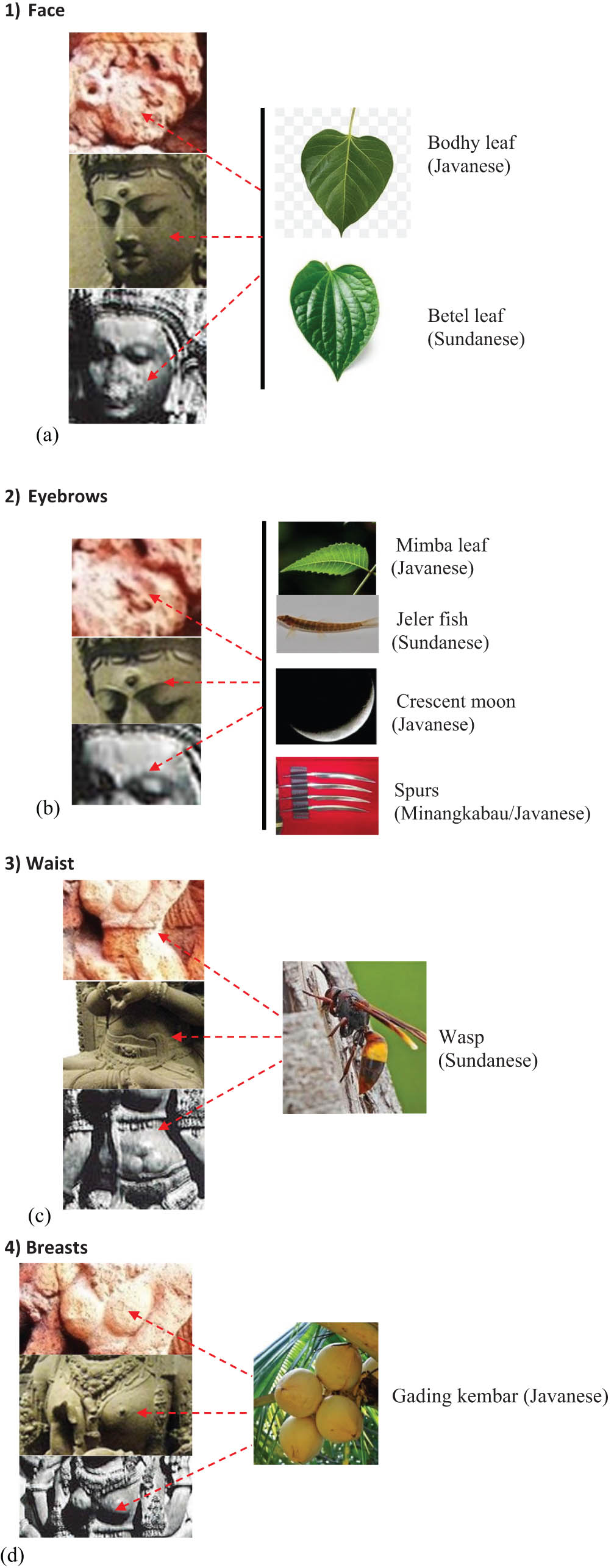

The two categories of metaphors above appear to complement each other. If the metaphor based on the similarity of form constructs the outer layer (shape) directly, the metaphor based on the similarity of nature or character constructs the shape indirectly through the creation of images according to the object mentioned. In the metaphor of form, we are immediately guided to connect the part of the body that is being metaphorized with the object or variety of nature that is referred to as the source. In character-based metaphors, we must first imagine the nature or character of the object being referred to so that an image of a certain form appears. This character metaphor also creates emotive images. From this point of view, a metaphor based on nature or character constructs the sensuality aspect of the beauty of the body as a whole.

The substitution in this metaphor is partial. The description of the figure of Sri Tanjung (Table 1) is more complete than the others. However, it remains incomplete and comprehensive. This means that the type of metaphor it constructs can be categorized as metonymy, in this case, synecdoche pars pro toto (a part represents the whole). Only certain parts of the body are described when referring to someone as beautiful. These parts, as seen in all the data found, are the parts that arouse sexual attraction (hair, eyebrows, eyes, lips, breasts, calves, etc.).

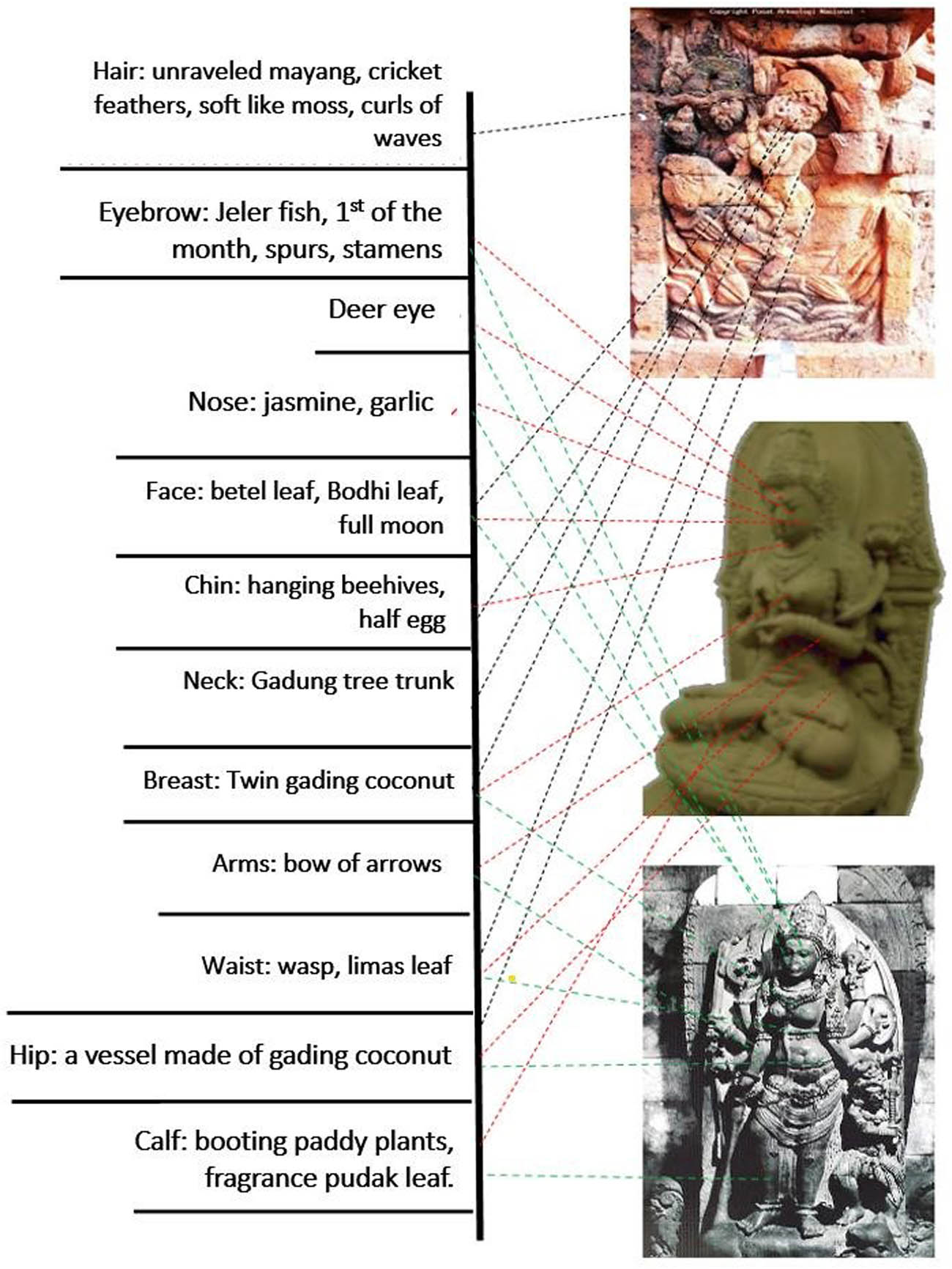

Therefore, at the real level, it is difficult to find one complete metaphorical description of this nature in all three ethnicities studied. It is interesting to note, however – and this is specifically for the Javanese ethnicity – that there are three representative figures in history, namely, the relief of the figure of Sri Tanjung on the wall of the pavilion of Surowono Temple, located in Kediri, East Java; the statue of Ken Dedes, found in Situbondo forest, East Java; and the statue of Loro Jonggrang, located at Prambanan Temple in Yogyakarta. The relief of Sri Tanjung is a visualization of a character in the Sri Tanjung manuscript, which explicitly states that Sri Tanjung is very beautiful (Aminoedin, 1986), while Ken Dedes and Loro Jonggrang are often referred to as the ideal female figures of their time (Winaya & Munandar, 2021)

The following is an analysis to show metaphorical relationships even though they are solely based on the similarity of forms and the parts of the body that appear explicitly.

In Figure 2, it can be seen that nearly all parts of the body are metaphorized. Parts of the body are compared to natural forms. The interesting thing is, even though the representative figure has Javanese ethnicity, the metaphors that apply in Sundanese and Minangkabau can also be applied. In Figure 3a–d, we clarify the metaphorical relationships and similarities between the three by cutting and enlarging certain parts that are most obvious (Figure 3).

Sketches of the metaphorical relation of beauty to the representative figures of Sri Tanjung, Ken Dedes, and Loro Jonggrang with natural varieties as their references. Source: Author.

Detailed beauty metaphors of (a) face, (b) eyebrows, (c) waist, and (d) breast by Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau.

4.2 Codes Behind Nature as Sources of Beauty Metaphors

In accordance with the anatomy of the body as a whole, the natural metaphors that cover it are automatically interconnected to form a unity or system of body metaphoric signs. Here the anatomy of the body becomes synonymous with a system of metaphorical signs originating in nature. In a semiotic perspective, the interconnectedness of signs is directly proportional to the formation of codes. In other words, the code is the relationship between signs that make up the system (Barthes, 2002). Based on this understanding, four codes can be found behind nature as the source of metaphors used to describe traditional beauty. The four codes in question are semantic, proairetic or narrative, symbolic, and referential or cultural.

4.3 Semantic Code

The process of denoting natural reality into language reality (denotation) at the next level creates connotation (Barthes, 1985). The denotative description of nature also forms the connotation of nature. Thus, the beauty of the female body which is described denotatively by natural varieties sends a connotative message that a beautiful woman is a woman who looks natural. In fact, this message has been agreed upon or accepted in Indonesian culture (Tilaar, 2017). Conversely, an artificial body (Hansen, 2006) or a body that is overly coated with “artificial attributes” is generally understood as a false body or a colonized body (Goldberg, 2004).

4.4 Proairetic or Narrative Code

Referring to written sources (Table 1), the metaphorical descriptions of traditional Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women, which are still alive and developing today, have been formed over a very long period of time and have passed through very long historical intervals. Based on these historical facts, the beliefs and characteristics of natural beauty have become a proairetic code or narrative code. The narrative is actually much older and can be traced to the myth of the presence of beautiful women on earth. It has become the essence of knowledge (Lyotard, 1989) that in Indonesian cultural narratives, the figure of ideal beauty for women always refers to creatures from heaven, namely, angels. Related to this, in some folklore that can be found throughout Indonesia, several angels who have descended to earth and transformed into humans use a process that involves nature (Wiyatmi et al., 2021).

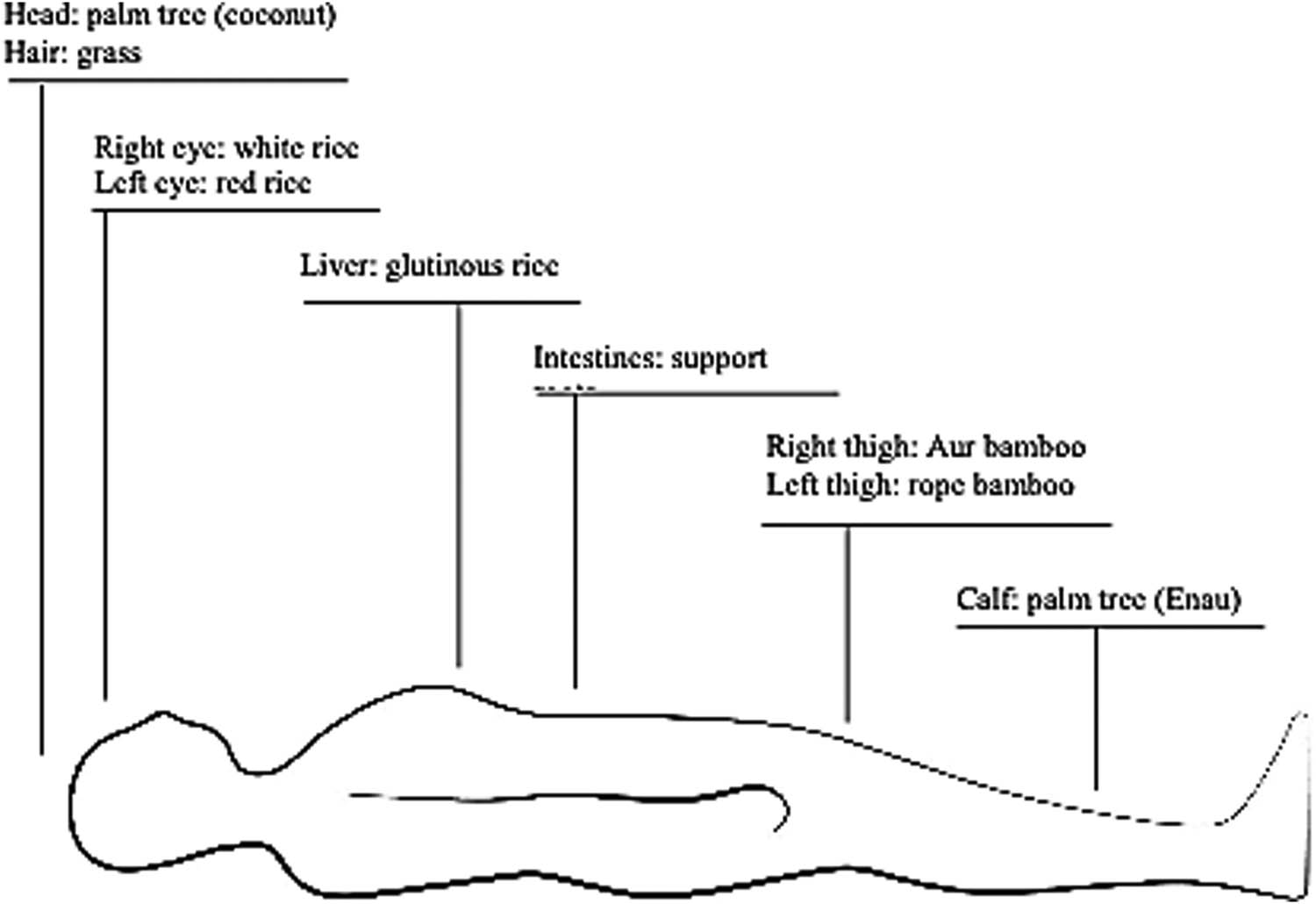

Among the mythological narratives of the beauty of an angel as it relates to nature, the mythology of Dewi Sri (Javanese) or Nyai Pohaci (Sundanese) is the most closely related, as both are central to this theme. The story, both in Java and in Sunda, has spread in different versions (Sumardjo, 2015; Wiyatmi et al., 2021). Nyai Pohaci is a figure who was born (or hatched) from an egg that was formed from the tears of the snake god, Antaboga. Nyai Pohaci grew into a woman of extraordinary beauty. This beauty, was considered very dangerous in the heavenly world, so she was killed by Batara Kala, who gave her a khuldi fruit. Nyai Pohaci’s body was then buried in the earth, and from the body parts that were buried, different plants grew. From the head grew a coconut palm, from her scalp grew grass, from her right eye grew white rice, from her left eye grew red rice, from her liver grew glutinous rice, from her intestines grew stilt roots, from her right thigh grew aur bamboo, from her left thigh grew rope bamboo, and on her calves grew palm trees (Holil, 2018; Kulsum & Rochaeti, 2005).Visually, the anatomy of Nyai Pohaci’s body is depicted and described in Figure 4.

In Figure 4, it can be seen that the beauty of Nyai Pohaci’s body is not analogous to objects in nature. Instead, it was from Nyai Pohaci’s body that nature was born (grown). However, the various trees that grew from parts of Nyai Pohaci’s body are representations of nature in general. Because of this, Nyai Pohaci is known as the Goddess of Fertility, an angel who makes nature fertile. As a result, if the concept of beauty for women on earth is nature and Nyai Pohaci is an angel who gave birth to nature, Nyai Pohaci can be said to be the source of beauty and thus, the source of traditional beauty metaphors. This means that the character that forms the basis of traditional beauty is the character of Nyai Pohaci, a character who exists as a subject of nature. Referring to Ponda (2021), Nyai Pohaci can be said to be the Indonesian version of Mother Earth (Toynbee, 1976) and as such is the source of the metaphor of Mother Earth, a term widely used for Indonesia’s homeland.

Sketch of the mythological body of Nyai Pohaci (Sundanese) or Dewi Sri (Javanese). Sketch made by the author (Source: Author).

4.5 Symbolic Code

The interesting thing about the proairetic code is the mythological event of Nyai Pohaci which narratively is a source for the formation of the character of the traditional beauty of Indonesian women. The growth of various types of plants from Nyai Pohaci’s body is an antithetical narrative, something that is illogical. This antithetical narrative is formed as the most subtle resistance of the woman’s body, a body which incidentally has died. There, the body resists by choosing nature, becoming nature’s biological mother. On this basis, the beauty attached to a woman’s body that causes her to be upheld and cast by men (the gods), eventually becomes power energy. Not just power before men, but also before nature. Women are the center of the universe, the center of life. In Indonesia, this mythological fact is still believed and experienced. Common sayings state that “behind the husband’s success there is a strong wife” and “the husband is afraid of his wife,” which are popular and believed in Indonesia to this day.

4.6 Referential Code (Culture)

The mechanism of substituting the similarity in shape and character of natural objects with the beautiful female body anatomy is a denotation of the “natural” to the “cultural.” In the beginning, the body is born as a natural biological entity. However, in its growth, the body becomes cultural (Synnott, 1993) because it is formed by aspects outside the body. In the context of traditional beauty of Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women, this is of interest because the body becomes cultural after it is subjected to natural traits and characteristics. Therefore, the body beauty of Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women is specific and unique: it is cultural when it is categorized as natural. This is the first referential code.

Next the relational fact of the beauty of the body and nature is in line with a saying of the Minangkabau ethnic group from West Sumatra, popular in Indonesia, namely, alam takambang jadi guru, or “nature can be a teacher.” This idealistic expression sends a message that nature is not an entity that must only be cared for, but more than that, must be learned from. One of the characteristics of nature – before being damaged by humans – is the balance of the forming elements and the mechanism or process of their continuity. Consequently, the natural beauty of a woman’s body is a balanced beauty (Tilaar, 2017). Physically, like nature, a woman’s body is formed by proportional and harmoniously related anatomical parts. The beautiful woman was not too thin and not too fat, not too tall and not too short, etc. “Fair yellow skin like half cooked prawns” also shows the character of the skin which is not white but also not black. In Indonesian culture, the balance point is in the middle, the middle siger (Sumardjo, 2015).

4.7 Beauty, Nature, and Women’s Power

Based on these data, it can be seen that nature is merely a source of beauty metaphors. There are no natural objects used to describe women who look unattractive (not beautiful). This fact sends at least two semiotic messages. First, the nature metaphors for beauty show an attitude of respect for traditional society toward the position of women’s beauty on the one hand, and nature on the other. Beauty is positioned at a higher level than ugliness such that “the beautiful” can be described using metaphors based on nature. This is identical to Synnott (1993), who put forward research data that beautiful women always represent good things, including good luck. On the other hand, nature is so highly regarded that it could only be used for metaphors describing beauty, and not for ugliness. Second, the fact remains that beauty is something exclusive, as with an attractive appearance or a beautiful body. This confirms what we have found, namely, that beauty is something that tends to refer to physical appearance.

It is interesting to note that the exclusivity of beauty in Indonesian culture has its roots in mythology. According to the myth, the beauty of Indonesian women is associated with the world of gods. This narrative has continued on earth, where beauty is intertwined with circles of power and growth in high social class (Brahmins). Dewi Nawang Wulan, who was “reincarnated,” became the Queen of the South Seas, and even married the Javanese ruler, Panembahan Senopati (Olthof, 2022). Other names such as Roro Jonggrang, Ratu Kaliyamat, Nyai Undang, Asung Luwang, Dewi Rengganis, Dewi Kencana Wungu, and Bundo Kanduang are beautiful female figures who were also rulers (Soediman, 1989; Wiyatmi et al., 2021). Many beautiful female figures in Indonesian mythology were also rulers or came from circles of power. In a wayang story, all the beautiful women who married Arjuna also came from circles of power or the upper social class. It is evident that beauty is held in high regard and is closely related to power in Indonesian culture.

There is an interesting side to the relationship between beauty and power, and that is that the lineage of beauty has become synonymous with the lineage of power. Contrary to the dominant discourse in feminism, in the tradition and history of Indonesian culture, the position of women is not subordinate to men, but rather ordinate. In the cases of Bundo Kanduang (Minangkabau) and Sunan Ambu (Sunda), women’s power is in full view, covering not only the social sphere but also the practical political realm. In the case of the Queen of the South Seas (Javanese and Sundanese), the power of beauty and socio-political power are explicitly integrated, subordinating not only life on land, but also at sea with a number of power labels (Pranoto, 2007, p. 54). In the case of Ken Dedes, Ken Arok struggled to seize Ken Dedes from Tunggul Ametung as a means to gain power (Mangkudimedja, 1979). In the case of Roro Jonggrang, the queen’s resistance to Bandung Bondowoso shows how the power of beauty subdues men on the one hand and how this power is firmly maintained on the other (Soediman, 1989). The context of power is in accordance with Indonesian culture which is in many ways different from the West (De Stuers, 2017; Handayani & Novianto, 2004; Nastiti, 2016).

In many cases, women’s beauty has become a kind of “inner force” that can undermine men’s existence. The beauty of women often drags men into emotional actions that can degrade them. The beauty of a woman’s body holds a powerful energy that attacks and paralyzes the roots of male power. Anderson (2000), who analyzed the “history of power” in Java from Ken Arok to President Soeharto, came to the conclusion that the power of kings in Java was largely determined by the energy possessed by women as companions. In Anderson’s notes, this power energy was spiritual-mystical in nature. However, in a broader (collective) scope, the emergence of matrilineal ideology in the Minangkabau shows that women’s power is present naturally as well as culturally. Mastery of land cultivation techniques (cultivation) by women affected the order of kinship, and both social and political relations so that women were at the center of power at that time (Soekarno, 1963).

For traditional Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women, therefore, being beautiful cannot be immediately understood as an unconscious mechanism of wanting to be at the “center of the gaze” of men. Instead, being beautiful can be seen as an effort to achieve a certain level in culture and social life. To be beautiful is to be strong; it is a mechanism to gain power, and in this case it means to exist and be noble in life, not just to exist and have power in front of men (Permanadeli, 2015).

However, the way to acquire beauty is not by exploiting the body. Beauty is still understood to be natural, a natural heritage that must also be nurtured by nature. Regarding treatment, the efforts made also rely on nature. Being beautiful and healthy is largely determined by to what extent nature is involved in or functions as the treatment (Beratha et al., 2020; Sibarani et al., 2021; Silaban & Sibarani, 2021). Natural objects are sources of beauty metaphors and, in fact, many can be used for beauty treatments. Mayang fruit (areca nut) and betel leaf, for example, are commonly used for chewing and spitting. Consumed separately (not for seasoning), betel leaves can eliminate mouth odors due to bad breath, mouthwash, and venereal diseases (syphilis). Referring to the information from Informant 1, water from boiled betel leaves can also be used to treat the vaginal lining and make female genitalia smell good. Meanwhile, betel nut can strengthen teeth and gums (BP3I, 2019). As a result, nature is not just a linguistic tool (a source of metaphor) to describe beauty, but also a grower and caregiver. Pasiak (2020) states that 25% of the medicines in modern medicine come from nature and 70% of the cancer drugs are natural or synthetic products whose inspiration comes from nature. It can be said, then, that caring for the body is synonymous with caring for (providing for) nature, and caring for nature is the same as caring for the body. In the study of neuroscience, the body and nature cannot be separated. Nature’s health undoubtedly leads to health of the body, and damage to nature can cause damage to the body.

At this point, it is clear that the traditional beauty of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women’s bodies originates entirely from nature. The beauty of the body becomes the beauty of nature itself. This is the ontological as well as epistemological basis of traditional women’s beauty in the three ethnicities. Beauty is not about the body being exploited, but rather being understood as the result of an intimate relationship with nature. With this understanding, beauty is not a myth that ultimately makes women suffer due to the fear of not being beautiful as Wolf (2002) points out. Culturally, in natural beauty, there is the energy of power.

5 Conclusion

Nature is the main source for constructing the metaphoric language that describes the traditional beauty of Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women. In other words, the traditional beauty of women in the three ethnicities is described through the choice of words that represent objects in nature, especially flora and fauna. However, it turns out that this description is not just language but also has a historical cultural aspect. At the same time, it also shows the strength of the character of the women’s beauty. Historically (originating from mythological narratives), the genealogy of beauty is one with the genealogy of nature. The beauty of a woman’s body even becomes the biological mother for the growth of nature. Culturally, the body is beautiful and has eternal beauty because of the respect and involvement of nature in its creation. Beauty is a blend of both culture and nature that ultimately shapes the character of beauty in Javanese, Sundanese, and Minangkabau women and makes it specific, namely, a character that has strength and the energy of power hidden behind softness in an entity that is perceived in modern society as a weakness. This character is constructed and reconstructed through semiotic codes in past mythological narratives and today’s society’s expressions and behaviors.

Based on these facts, we recommend considering a perspective on the relationship between the beauty of the female body and the universe, which we would like to call “the ecology of beauty.” This perspective can enrich the discourse on ecofeminism that has been developed and discussed by various groups, even by those who are not actively involved in it. However, the ecology of beauty is not a movement against the socio-political power of men alone, but rather against the capitalist power that increasingly destroys the beauty of women’s bodies on the one hand and destroys nature on the other. The ecology of beauty is an idea and movement that can be directed toward respect for both beauty and nature in a proportional manner. Beauty must be saved from the beauty industry, just as nature must be saved from the greed of the capitalistic industry, which causes deforestation all over the world. The idea and movement of the ecology of beauty allow for beauty in its tenderness and nature in its beauty to emerge as subjects for the organization of human civilization today and in the future.

The idea and movement of beauty ecology should be seen as important and urgent. However, we realize that strengthening this concept requires further, more in-depth, and extensive research. This article is based on limited research focusing on traditional beauty concepts among Indonesian women and does not include comparative studies with similar cases from other cultures worldwide. Exploring similar studies in other natural and cultural contexts would undoubtedly be interesting and could provide valuable insights to either strengthen or challenge the ideas of beauty ecology we have presented. In this context, this article can serve as a useful reference for future studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Institute of Research and Community Service (LPPM) of Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) for the support. We also extend our gratitude to all of the reviewers who have contributed to the peer review process.

-

Author contributions: Acep Iwan Saidi: the head of the research team, contributed as the initiator of the research idea, conducted literature studies, guided data collection and strategies in the field, analyzed data, and interpreted the findings. Dyah Gayatri Puspitasari: research team member, contributed to the literature study, field data collection, and provided input on analysis and writing structure. Christabel Annora Paramita Parung: research team member, contributed to data analysis, editorial work, and served as the corresponding author. Laura Christina Luzar: research team member, contributed to field data collection and provided input on analysis and writing structure.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Acuña, V. C. (2019). Semiotic distribution of responsibility: An ethnography of overburden in Colombia’s emerald economy. The Extractive Industries and Society, 6(4), 1040–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2019.03.018.Search in Google Scholar

Agustina, N., & Suryaningsih, B. (2016). Pengaruh Penggunaan Krim Pemutih Kulit Terhadap Terjadinya Teleangiektasis pada Mahasiswa Fakultas Kedokteran UII. JKKI: Jurnal Kedokteran dan Kesehatan Indonesia, 7(5), 40–46. https://journal.uii.ac.id/JKKI/article/view/6718.10.20885/JKKI.Vol7.Iss2.art1Search in Google Scholar

Althusser, L. (1984). Essays on ideology. Verso.Search in Google Scholar

Aminoedin, A. (1986). Penelitian bahasa dan sastra dalam naskah cerita Sri Tanjung di Banyuwangi. Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, B. R. G. (2000). Kuasa Kata: Jelajah Budaya-budaya Politik di Indonesia (R. B. Santosa, Trans.). Mata Bangsa.Search in Google Scholar

Balai Poestaka. (1953). Hikajat Pandji Semirang. Balai Poestaka.Search in Google Scholar

Barthes, R. (1985). The element of semiology (A. L. a. C. Smith, Trans.). Hill and Wang.Search in Google Scholar

Barthes, R. (2002). S/Z. Blackwell Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Beratha, N. L. S., Wayan Sukarini, N., & Made Rajeg, I. (2020). Fungsi Ekoleksikon Kecantikan dalam Lontar Bali Indrani Sastra. Journal of Bali Studies, 10(1), 163.10.24843/JKB.2020.v10.i01.p08Search in Google Scholar

BP3I. (2019). Buku Saku Tanaman Obat: Warisan Tradisi Nusantara untuk Kesejahteraan Rakyat. Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Perkebunan.Search in Google Scholar

De Stuers, C. V. (2017). Sejarah Perempuan Indonesia, Sejarah dan Pencapaian (d. Elvira Rosa, Trans.). Komunitas Bambu.Search in Google Scholar

Desiana, F. I., & Dienaputra, R. D. (2019). Akulturasi Budaya Sunda Dan Jepang melalui penggunaan igari look dalam tata rias sunda siger. Patanjala : Jurnal Penelitian Sejarah Dan Budaya, 11(1), 149. doi: 10.30959/patanjala.v11i1.399.Search in Google Scholar

Eco, U. E. (2004). On beauty, A history of a western idea (T. I. b. A. McEwen, Trans.). Secker and Warburg.Search in Google Scholar

Faudree, P. (2012). Music, language, and texts: Sound and semiotic ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41, 519–36.10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145851Search in Google Scholar

Fiske, J. (1990). Ethnosemiotics: Some personal and theoretical reflections. Cultural Studies, 4(1), 85–99. doi: 10.1080/09502389000490061.Search in Google Scholar

Foucault, M. (1997). Discipline and punish, The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Billing and Sons.Search in Google Scholar

Gaard, G. E. (1993). Ecofeminism: Women, animal, nature. Temple University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, P. (2004). Fabricated bodies: A model for the somatic false self. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85(4), 823–840. doi: 10.1516/KFG7-97TU-EP99-1HR1.Search in Google Scholar

Gottschall, J. (2008). The ‘Beauty Myth’ is no myth: Emphasis on male-female attractiveness in world folktales. Human Nature, 19(2), 174–188.10.1007/s12110-008-9035-3Search in Google Scholar

Guattari, F. (2000). The three ecologies (I. Pindar & P. Sutton, Trans.). The Athlone Press. (Original work published 1989.).Search in Google Scholar

Hamka. (1984). Tenggelamnya Kapal Van Der Wijk. PT Bulan Bintang.Search in Google Scholar

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice. (3rd ed.). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Handayani, C. S., & Novianto, A. (2004). Kuasa Wanita Jawa. LKiS.Search in Google Scholar

Hansen, M. B. N. (2006). Bodies in code: Interfaces with Digital Media. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Heller, A. (2012). The concept of the beautiful, edited with an essay by Marcia Morgan. Lexington Books.Search in Google Scholar

Herman, D., & Moss, S. (2007). Plant names and folk taxonomies: Framework for ethnosemiotic inquiry. Semiotica, 167(1/4), 1–11. doi: 10.1515/SEM.2007.069.Search in Google Scholar

Herzfeld, M. (1983). Signs in the field: Prospects and issues for semiotic ethnography. Semiotica, 46(2/4), 99–106.10.1515/semi.1983.46.2-4.99Search in Google Scholar

Hokheimer, M. (1972). Critical theory, selected essays (M. J. O’Cornell and others, Trans.). Continum.Search in Google Scholar

Holil, M. (2018). Wawacan Sulanjana. Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia.Search in Google Scholar

Hunga, A. I. R. (2013). “Ekofeminisme, Krisis Ekologis, dan Pembangunan Berkelanjutan” dalam Candraningrum. Jalasutra.Search in Google Scholar

Indira, D., Mulyadi, R. M., & Nasrullah, R. (2019). Komunitas Jawa Di Desa Wonoharjo Sebagai Jejak Migrasi Etnis Jawa Ke Kabupaten Pangandaran Sosiohumaniora. Jurnal Ilmu-ilmu Sosial dan Humaniora, 21(1), 34–39. doi: 10.24198/sosiohumaniora.v21i1.19024.Search in Google Scholar

Kayam, U. (1991). Para Priyayi. Pustaka Utama Grafiti.Search in Google Scholar

Kayam, U. (1999). Jalan Menikung (Para Priyai 2). Pustaka Utama Grafiti.Search in Google Scholar

Kozin, A. V. (2014). On the cultural meaning of the New Yorker ‘Lawyer Cartoon:’ An experiment in ethnography of communication. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 28(4), 801–823. doi: 10.1007/s11196-014-9399-0.Search in Google Scholar

Kulsum, & Rochaeti, E. (2005). Sastra Ritual, Wawacan Batara Kala, Wawacan Sulanjana. Dunia Pustaka Jaya.Search in Google Scholar

Levesque, S. (2016). Two versions of ecosophy: Arne Naess, Félix Guattari, and their connection with semiotics. Σημειωτκή. Sign Systems Studies, 44(4), 511–541. doi: 10.12697/SSS.2016.44.4.03.Search in Google Scholar

Liem, S. (2022). Artikulasi Rasa, Mencintai Kecantikan Diri Sepenuhnya. Kompas Gramedia.Search in Google Scholar

Lintott, S. (2010). Feminist aesthetics and the neglect of natural beauty. Environmental Value, 19(3), 315–333. doi: 10.3197/096327110X519853.Search in Google Scholar

Lyotard, J. F. (1989). The postmodern condition. (Theory and history of literature; v. 10). Translation from the French by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota Press.Search in Google Scholar

MacCannell, D. (1979). Ethnosemiotics. Semiotica, 27(1–3). doi: 10.1515/semi.1979.27.1-3.149.Search in Google Scholar

Mangkudimedja, R. M. (1979). Serat Pararaton Ken Arok (buku 2). Depdikbud.Search in Google Scholar

Muchtar, R. (2015). Praktek Komunikasi Antar Budaya Para Perantau Minangkabau Di Jakarta. Jurnal Penelitian Pers dan Komunikasi Pembangunan, 18. doi: 10.46426/jp2kp.v18i3.22.Search in Google Scholar

Mu’jizah, M., & Ikram, A. (2020). Transformation of Candra Kirana as a beautiful princess into Panji semirang; an invincible hero. Wacana, 21(2), 191. doi: 10.17510/wacana.v21i2.772.Search in Google Scholar

Muluk, H., & Murniati, J. (2007). Konsep Mental Menurut Masyarakat Etnik Jawa dan Minangkabau. Jurnal JPS, 13(2), 167–181.Search in Google Scholar

Naim, M. (1973). Merantau, Pola Migrasi Suku Minangkabau. Gadjahmada University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Naim, M. (1980). Minangkabau dalam Dialektika Kebudayaan Nusantara. Makalah Seminar, tidak diterbitkan.Search in Google Scholar

Nastiti, T. S. (2016). Perempuan Jawa, Kedudukan dan Perannya dalam Masyarakat Abad VIII–XV. Pustaka Jaya.Search in Google Scholar

Olthof, W. L. (2022). Babad Tanah Jawi, translate by HR Sumarsono, cetakan ke-9. Narasi.Search in Google Scholar

Pasiak, T. (2020). Otak dan Kota: Kecerdasan Biofilia—Tuhan, Alam, dan Manusia. Yayasan Semesta Otak Indonesia.Search in Google Scholar

Permanadeli, R. (2015). Dadi Wong Wadon, Representasi Sosial Perempuan Jawa di Era Modern. Pustaka Ifada.Search in Google Scholar

Piliang, Y. A. (2003). Hipersemiotika, Tafsir Cultural Studies atas Matinya Makna. Jalasutra.Search in Google Scholar

Ponda, A. (2021). Asal-Usul Eko Feminisme, Budaya Patriarki dan Sejarah Feminisasi Alam. Cantrik Pustaka.Search in Google Scholar

Prabasmoro, A. P. (2003). Becoming White: Representasi Ras, Kelas, Feminitas, dan Globalisasi dalam Iklan Sabun. Jalasutra.Search in Google Scholar

Pranoto, T. H. T. (2007). Membuka Tiraai Ghaib Kraton Ratu Kidul dan Gunung Srandil. Kuntul Press.Search in Google Scholar

Radzi, W. M., & Noordin, F. (2022). Status of cosmetic safety in Malaysia market: Mercury contamination in selected skin whitening products. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 21(12), 6875–6882. Blackwell Science; PMID: 36181345, Database: MEDLINE PubMed.10.1111/jocd.15429Search in Google Scholar

Raffles, T. S. (2019). The history of Java. Narasi.Search in Google Scholar

Rajo Endah, S. S. (1989). Tuanku Lareh Simawang: Kaba Klasik Minangkabau. Pustaka Indonesia.Search in Google Scholar

Robbiah, S. (2022). Inovasi Fonologi Bahasa Jawa Dialek Banten Di Perbatasan Kabupaten Serang Provinsi Banten. Journal: Prosiding Konferensi Linguistik Tahunan Atma Jaya (KOLITA), 20, 357–363. doi: 10.25170/kolita.20.3816.Search in Google Scholar

Rusli, M. (1974). Siti Nurbaya. Pustaka Melayu Baru.Search in Google Scholar

Rusli, M. (2013). Memang Jodoh. Bandung Qanita.Search in Google Scholar

Saraswati, L. A. (2022). Putih: Warna Kulit, Ras, dan Kecantikan di Indonesia Transnasional. Translated by Andarnuswari from Seeiing Beauty, Snsing Race in Transnational Indonesian. University Hawai’i Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sartwell, C. (2004). Six names of beauty. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Sati, T. S. (1978). Sabai Nan Aluih: Cerita Minangkabau Lama. Depdikbud.Search in Google Scholar

Shamban, A. (2019). The signature featureTM: A new concept in beauty. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 18(3), 692–699. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12944.Search in Google Scholar

Short, T. L. (2007). Peirce’s of signs. Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sibarani, R., Simanjuntak, P., & Sibarani, E. J. (2021). The role of women in preserving local wisdom Poda Na Lima ‘Five Advices of Cleanliness’ for the community health in Toba Batak at Lake Toba area. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35(2), S533–S536. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2021.10.086.Search in Google Scholar

Silaban, I., & Sibarani, R. (2021). The tradition of Mambosuri Toba Batak traditional ceremony for a pregnant woman with seven months gestational age for women’s physical and mental health. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35, 558–560. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2021.07.033.Search in Google Scholar

Soediman. (1989). Candi Larajonggrang, Selayang Pandang. Booklet Candi Prambanan, tanpa nama penerbit.Search in Google Scholar

Soekarno. (1963). Sarinah. Kewajiban Wanita Dalam Perdjoangan Indonesia. Panitya Penerbit Buku-Buku Karangan Presiden Sukarno.Search in Google Scholar

Sommerlad, M. (2022). Skin lightening: Causes and complications. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 47(2), 264–270. Blackwell Scientific Publications; PMID: 34637158, Database: MEDLINE. doi: 10.1111/ced.14972.Search in Google Scholar

Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Fort Worth Philadelphia San Diego. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Sumardjo, J. (2015). Sunda, Pola Rasionalitas Budaya. Kelir.Search in Google Scholar

Synnott, A. (1993). The body social: Symbolism, self, and society. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Tilaar, M. (2017). Kecantikan Perempuan Timur. Gramedia.Search in Google Scholar

Toynbee, A. (1976). Mankind and mother earth: A narrative history of the world. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Vlekke, B. H. M. (2008). Nusantara Sejarah Indonesia, translate by Samsudin Berlian From original title Nusantara: A History of Indonesia, 1961. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia.Search in Google Scholar

Wahil, M. S. A. I., Ishak, M. F. M, & Daud, F. (2019). Awareness of health effects from skinwhitening product usage: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Health & Clinical Sciences (IJPHCS), 6(6), 20–32. 13 p. doi: 10.32827/ijphcs.6.6.20. Acces Number: 141202940.Search in Google Scholar

Wallace, A. R. (2009). Kepulauan Nusantara, Sebuah Kisah Perjalanan, Kajian Manusia dan Alam. Translated by Komunitas Bambu from The Malay Archipelago. The Land of the Orang Utan and the Bird Paradise. A Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature (1869). Komunitas Bambu.10.5962/bhl.title.131886Search in Google Scholar

Winaya, A., & Munandar, A. A. (2021). Ancient Javanese Women during the Majapahit period (14th – 15th centuries CE): An Iconographic Study based on the Temple Reliefs | Perempuan Jawa Kuno periode Majapahit (Abad ke-14 – 15 Masehi): Suatu tinjauan Ikonografi terhadap Relief Candi. SPAFA Journal, 5, 1–24. doi: 10.26721/spafajournal.2021.v5.658.Search in Google Scholar

Wiyatmi, Sari, E. S., & Liliani, E. (2021). Para Raja dan Pahlawan Perempuan, Serta Bidadari dalam Folklor Indonesia. (Cetakan ke-2). Cantrik Pustaka.Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, N. (2002). The beauty myth: How images of female beauty are used against women. William Morrow, (originally published in 1991).Search in Google Scholar

Yulianto, V. (2007). Pesona Barat, Analisis Krisis-Historis Tentang Kesadaran Warna Kulit di Indonesia. Jalasutra.Search in Google Scholar

Yulita, O., Anwar, K., Putra, D., Isa, M., & Yusup, M. (2021). Akulturasi Budaya Pernikahan Minangkabau dengan Transmigrasi Jawa di Kabupaten Solok Selatan Sumatera Barat. Journal: Ideas: Jurnal Pendidikan, Sosial, dan Budaya, 7, 1–12. doi: 10.32884/ideas.v7i2.333.Search in Google Scholar

Zein, D., Wagiati, & Darmayanti, D. (2022). Pola komunikasi pasangan antaretnis Sunda-Jawa di Kabupaten Ciamis. Jurnal Manajemen Komunikasi, 6, 246–262. doi: 10.24198/jmk.v6i2.33318.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, W., Yang, A., Wang, J., Huang, D., Deng, Y., Zhang, X., Qu, Q., Ma, W., Xiong, R., Zhu, M., & Huang, C. (2022). Potential application of natural bioactive compounds as skin‐whitening agents: A review. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 21(12), 6669–6687. 19 p. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15437.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood