Abstract

I compare a photo album of the war in former Portuguese Guinea that I found in my home when I was a child with a collection of writings by Victor Bor, a healer and diviner whom I met in southern Guinea-Bissau who was a guerrilla during that country’s war of liberation and who was possessed by a vision that the Balanta people call Kyangyang [The Shadow]. I discuss the visuality and tactility of these two complex assemblages of images as tangible negative spaces that capture and shape the gaze. How do certain images have the power to enthrall, to trap the viewer? How can they intoxicate and mobilize into gang murder in a wartime setting? At the same time, I discuss the layers and characters that the gaze assumes in order for someone to create these images, and how they materialize a kind of exchange between generations. What is it that crosses the gaze of a previous generation through its images of violence? Yet, in parallel, there is the stunning effect of looking at shocking images of war, as opposed to being stunned by visions of lights and explosions that compel shocking actions in a post-war environment.

1 The Beginning

In 1974, the war in Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique between the Portuguese armed forces and the corresponding African liberation movements was officially over. Portuguese citizens who had been drafted to fight in the war returned to a radically changed nation after the April 1974 revolution ended a totalitarian regime based on early European fascist ideologies. The revolution was underway, and anything related to the colonial past became an embarrassment. The priority was to get rid of the colonies and traces of imperial discourse, and to continue the class struggle within the borders of a newborn Portugal, through profound processes of redistribution of property, agrarian reform, and nationalization of the economy. I was born 2 years after the turning point of 1974, when the revolution, the end of the empire, and the colonial war all came together. My father was a soldier in the Portuguese army in the former Portuguese Guinea, now Guinea-Bissau, between 1972 and 1974. For many years, my work, mainly as a visual artist, drew heavily on a collection of images he brought back from the war, which I collected as a child from his belongings scattered in the safety of our home. Over time, I have been able to think about this collection in relation to what several authors have done in the field of critical studies (Medeiros, 2002; Pinto Caldeira, 2019; Ramos, 2020).

This piece is about my trajectory as an ethnographer in the wake of my work as a visual artist toward a broader ethnographic landscape of imperial debris (Hunt, 2006; Stoler, 2013), a landscape where I met some of the people in those old images, but also people in Guinea-Bissau, former members of the liberation movement, who shared their images of war with me. From a (self-)reflexive framework, thinking about the urgency of working on private collections related to the colonial period, as claimed by Vicente (2014, p. 13), I think about the status of images produced in a colonial setting, asking what kind of spatial/temporal entanglements these images form. How do they connect geographies, past and present generations, articulate subjectivities, and objects?

This is primarily part of my anthropological research on images of colonial war, which stems from my artistic practice. It is therefore linked to a field of scholarship where anthropology meets art history and visual studies. In “An Anthropology of Images,” Hans Belting, one of the leading references on this threshold between anthropology and art theory, discusses the relationship between humans and images over time, i.e., the human body as a medium of immaterial images (Belting, 2014). My research enters this debate to further inquire into the significance of such a connection in shaping contemporary human behavior. Michael Taussig’s discussion of the tension between drawing, photography, and text in ethnography provides a point of entry into the fusion of artistic and anthropological methods that I find relevant to an anthropological approach to images.

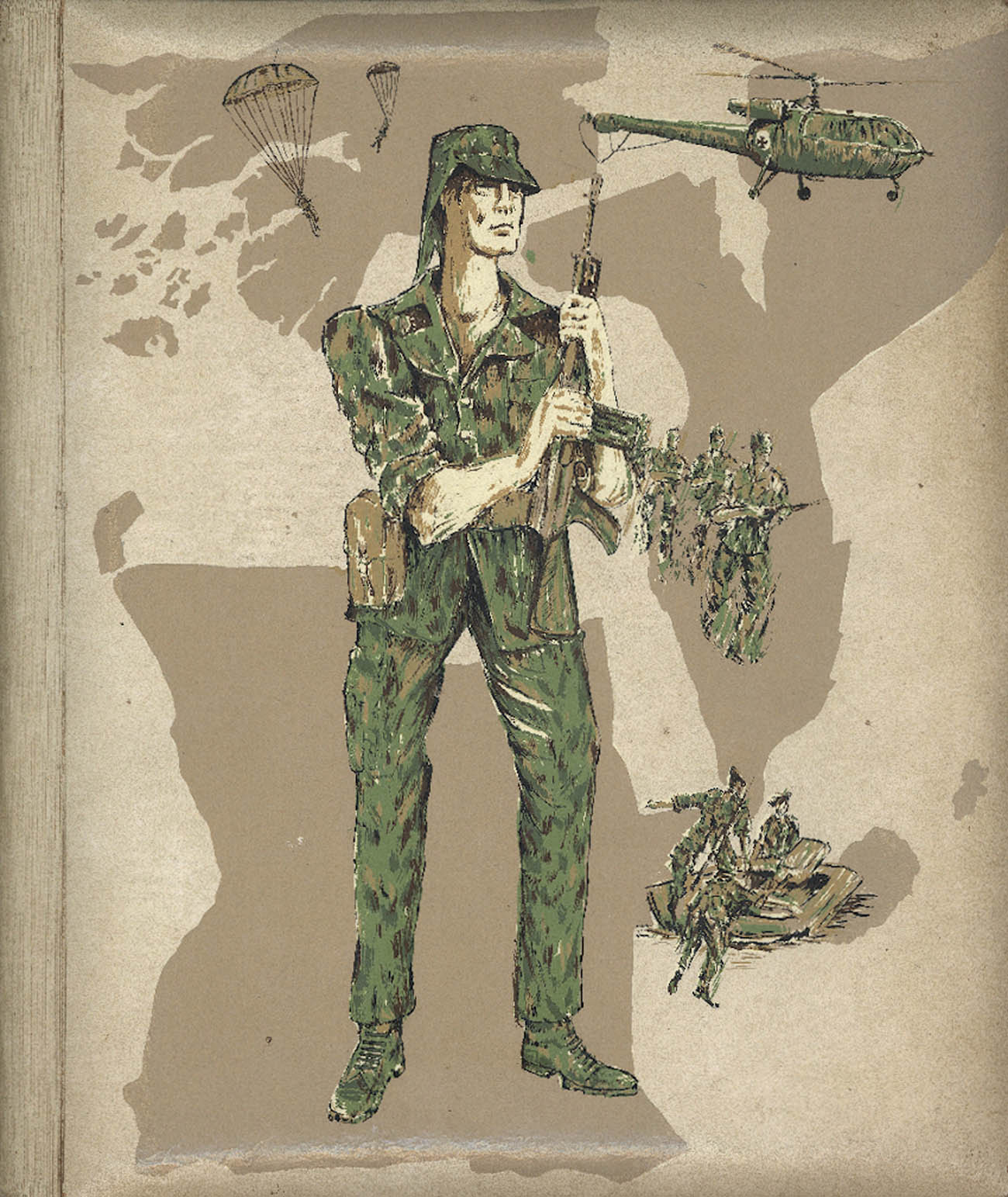

In the post-COVID-19 world in which we live today, where confinement has led us to reconsider some of the most hidden aspects of our lives, looking back at the images of the old war album from the former Portuguese Guinea that emerged in the safety of my childhood household seems like a relevant exercise in reassembling notions of safety and belonging (Figure 1).

Cover of the photo album from the war in former Portuguese Guinea. Private collection of Joaquim Barroca.

2 War Album

2.1 Tactility/Sticky Surfaces

The cover is very thick, yellowed, and dusty, and the texture of the surface is made of soft plastic with a tactility slightly similar to leather. Looking closely at the padding, I am surprised to see the meticulously folded corners and the finishing with a cardboard back that holds it to the rest of the sheets, bound with a plastic spiral to hold all together. The old remnants of acidic glue at the junctions of the assembled parts have lost their transparency and become darker than the paper. The plastic bindings aged similarly, becoming even cheaper than before. I try to remember the total number of pages, but I know that they are made of stiff cardboard with a square hole in one edge to fit the plastic cover. Each page is covered with a thin layer of plastic, with many horizontal lines of semi-fresh glue holding the photos to the surface. Once the images are in place, a sheet of sticky acetate charged with static electricity covers the entire page, giving it a uniform finish, almost as if someone had varnished it.

The glue on the pages remained soft over time; it never dried or hardened and remained sticky over the years. Therefore, it is always possible to remove any of the previously pasted images. Pasting an image on such a surface is not a graceful gesture, because as soon as the back of the photograph touches the glue, it immediately sticks – it’s extremely difficult to achieve a precise juxtaposition of the images. On the other hand, removing a photo is also a strange sensation, because it is difficult to calculate the right pressure to remove a photo without damaging it. Usually, the paper gets accidentally bent, or even torn when you try to move it under such conditions. Every time I manipulated the album by trying to detach a picture, I would get my finger stuck on one of those strips and feel the skin wrinkle before I was able to pull it out and free myself. In those moments, I also felt physically part of that intimate assemblage of materials, glued to it like any other of its elements. Even as I pull open these acetate sheets, I feel the static attract the hairs from my hands, and its clumsy magnetism entangles my fingers in the object.

The album has a squeaky viscosity (Deleuze, 1987, p. 4) that clings to and captures my nervous body from skin to eyes. In other words, the materiality of the album (Ingold, 2010) constitutes an infrastructure, an architecture, which houses a collection of photographs and sucks my self, my sense of personhood (Ingold, 1991; Pina-Cabral, 2018; Toren, 2012; Varela et al., 2016) into a redefined sense of scale that encapsulates my tactile body in its otherwise inhuman space (Yates, 2014).

2.2 Visual Assemblage

Sometimes these pages contain linear sequences of photographs, and sometimes they contain agglomerations of images that look like photographic patchworks. This is because none of the prints were ever physically cut. As a result, I see a constellation of superimpositions and overlays that hide parts of the images, reframing them, rearranging their original composition, in some cases revealing fragments (that could function independently as a whole), in others suggesting that something relevant has been hidden. If there are places where the arrangement seems completely random, there are others where it makes sense, as when the images are pressed together in such a way that the flatness of the surface is subtly relieved. The thickness that results from this layering points to other spaces, details, and temporal complexities that affect my perception of the whole object.

An apparatus or device is a technical mechanism capable of producing sounds and images, or “machines which make one see and speak.” (Deleuze, 1991, p. 160) Although it may require an operator, an apparatus is to some extent self-sufficient in mediating between a human operator and a visual referent. The following is a classic example: a photographic camera is an apparatus because, in capturing the image of an observed object, it also alters the affect on the camera operator and the person viewing the photograph resulting from the operator/camera interaction. By looking through the lens, the photographer rediscovers the photographed object; by looking at the image, the viewer rediscovers a familiar thing, place, or person through the mediation of the apparatus. Such a device, then, re-presents and re-affects the world by shifting the perception of it by placing it on a mediated level of inquiry. The discussion of the photographic apparatus and its power to create distorted perceptions of the world (Flusser, 1998; Benjamin, 2008) taps into a debate about the mediated perception of reality that goes back to antiquity (Plato, 2017). It is an old, but still relevant discussion that asserts that an imaging apparatus creates illusions that we largely take as truth. But what matters most for this anthropological discussion is that an apparatus is an immersive relational device that enhances the sociability between a human operator, a technical apparatus that is the photographic camera, the images that such interaction produces, and the material forms that these images take in social space, such as the war album I am discussing here (Spyer & Steedly, 2013). All of these parts are intimately connected in a great assemblage of affect and reciprocity in which we can distinguish the parts but not separate them.

The album is a visual apparatus that ultimately constitutes an assemblage (Deleuze, 1987, p. 4) made up of the interconnectedness of human and object, where both are unified in a sphere of intimacy where social meanings continue to resonate, become the object of internalized meditations, and eventually lead to shifts in our social behavior. Things like this war album, which have a tremendous power of attraction, of sucking us in and transforming our life trajectories, are far from being harmless safety zones. In their uncanny way of revealing hidden images, they can enthrall, captivate, and trap one’s gaze in limbic visions of the (un)real (Taussig, 1987). And this ability of the war album as an object to destabilize the perception of reality is the point at which we can begin to think about how this object, innocently dumped in the house where I grew up, undermines the very notion of home as a safe place.

2.3 Looking at Pictures

On the cover illustration, in the foreground, we see a clumsy depiction of a soldier. He is wearing a green camouflage uniform with a tiny hip pack, a soft cloth hat, combat boots also rendered in green, and an automatic rifle clumsily held with both hands. The proportions are awkward – the legs are too big for the feet, which seem too small for the rest of the body; the hips are too high, the pelvis resting on the navel; the left shoulder and arm are too big for the torso; the neck is also too big for the head, which seems too small for the rest of the body, as if it had been cut and pasted from another, shorter figure. Nothing seems to fit. The soldier’s figure looks human, but does not seem to function as such. On the layer directly behind it, we can see some camouflaged brown-gray areas that represent the map of the late Portuguese Empire. On the top left, we have Guinea-Bissau with two armed paratroopers falling from the sky. Next to it, on the right, is Mozambique, with a helicopter flying over the territory with a badge of the Portuguese Cross and a line of soldiers walking across the south. Below that is Angola, where the central figure is standing, and right next to it is São Tomé e Príncipe, with a group of three soldiers arriving on a motorized dinghy. The entire illustration looks as poorly rendered as the central figure. This strange depiction seems like a visual symptom of the anachronistic Portuguese decolonization process, whose narrative consistently lacks articulation.

I cannot remember the first time I came into contact with this object, the war album. I found it in my house as a child, a few years after the war. Or was it the other way around? Did I find the album or did it find me? I say I found it because I remember seeing it one day, clearly available, looking back at me (Didi-Huberman, 1998), ready to be picked out of our family memorabilia (Hirsch, 2016). Now it feels like it has come to the fore from a confusing background of mixed family images and narratives. I was a curious child, open to being impressed by pictures of my father in a past war in a distant country that people around me informally called Guiné.

The album offers a narrative of my father’s evolving experience in the war. At the end, on the last few pages, we see the only color pictures of Guinea-Bissau in the entire album (dated April 74), pictures of a destroyed Portuguese headquarters, its entire infrastructure reduced to rubble by a hail of rockets. These are images of the aftermath of war, where the rubble begins to be inhabited by new life. We do not see soldiers anymore. Instead, local people and their animals, goats and chickens, seem to roam amidst the debris of the Portuguese Empire (Stoler, 2013), adapting to a new reality.

The images my father collected in the album can be divided into two groups. In one group are images of himself as a soldier and other military personnel in training and combat situations, at dinner parties, and interacting with the locals, as described in other cases (Medeiros, 2002; Pinto Caldeira, 2019). And then, in the second group, we find images of his girlfriend at the beach, at the lake, surrounded by flowers in spring, with her sisters in their parents’ house in a mining town in southern Portugal. The pictures taken in Portugal were in color. Those from Guinea were black and white. This difference places them in different temporalities. The photos from Guinea seem to belong to a very distant and bleak past. The others, on the other hand, seem to be images of a happy promised land, which today I cannot stop myself from interpreting as an outdated idealization of the future. A future that was nothing more than a version of the present moment that functioned within the album as a temporal corridor that probably felt like an escape from the nightmare of war for an ordinary soldier like him, back in Guinea between 1972 and 1974.

As I looked through the album over the years, there were a few images that caught my attention. Figure 2, for example, shows seven soldiers in a Berlioz truck. The driver is looking straight down the road, his weapon next to the wheels, ready for anything. They are in the arid northern part of Guinea, where the landscape is thinner and drier than in the south. The big tires move slowly to keep balance on the steep ground. Next to the driver, a standing man looks directly into the camera. Two soldiers seated behind him look piercingly through the space between them and the photographer, like hunters spotting game. Their eyes, staring at the lens, are imprinted in my mind as a viewer, as if I were part of the situation being photographed. Time is confusing. This scene is no longer about the past, because the past is present through the way the image looks back at me as a viewer.

Portuguese soldiers on a Portuguese Army Berliet truck. Private collection of Joaquim Barroca.

There are many images of meals in the collection. Pinharanda wrote a remarkable essay in which he discussed these groups of soldiers posing at a dinner table as a repetition of the Last Supper (2013). In one of them (Figure 3), five men face the camera as they eat and drink. The one on the left is drinking a beer while looking out of the frame. Next to him, another soldier concentrates on cutting a piece of bloody meat. The one next to him stares at the camera while apparently talking nonsense. Next to him, someone looks into the lens while putting a piece of bread into his mouth, while the last in the row looks completely petrified by the photographic moment (Barthes, 2012). In front of them, the heads of two other people and a hand creep into the frame to grab a bottle of beer. In the background, there is a piece of furniture with a pile of objects next to an empty, dirty wall.

Portuguese soldiers eating at Piche. Private collection of Joaquim Barroca.

Three men and a dead gazelle are shown in Figure 4. All three men are seated on shallow benches, almost squatting. The one on the left, one of the few Africans in the entire album, is holding a wooden beam and looking at the man in the middle, who is carefully holding the animal’s head while turning it toward the camera at the moment of death. The eyes of the dead game look peaceful but uncomfortably intense: Is it alive? A bearded man with a nervous smile seems to be waiting for the photographic moment as he holds a knife against one of the gazelle’s legs. The white lines and dots on the animal’s fur, the diagonal position of the base on which it lies, and the shadows coming from above and below its body, which contrast with the horizontality of the background, add to the drama.

Two men from the Portuguese army and a presumably local young man slaughtering a gazelle. Private collection of Joaquim Barroca.

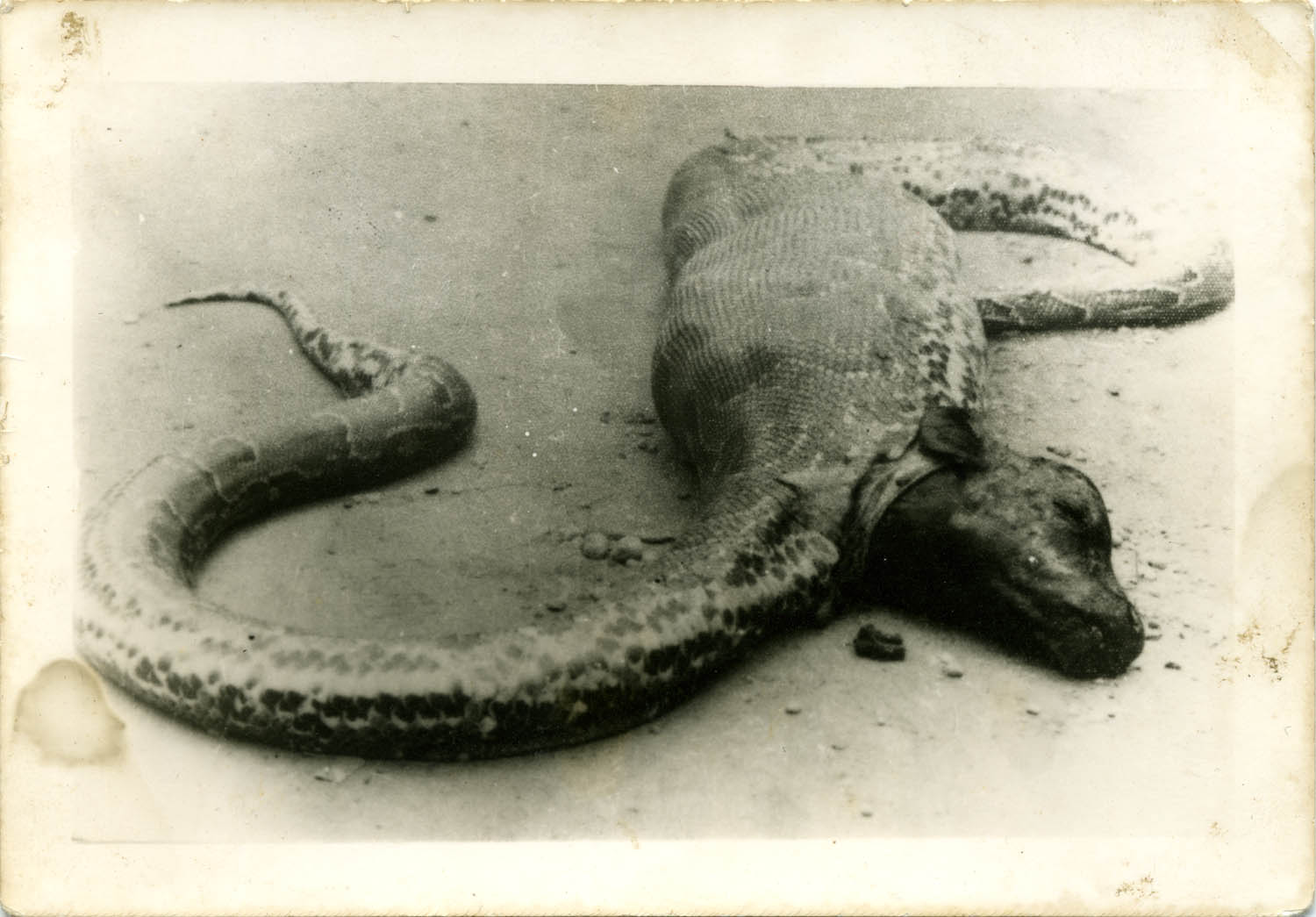

In another shot, a dead, deformed python lay on the ground (Figure 5). I know that its belly had been cut open by the soldiers, and that is why we see the head of a calf sticking out of its belly. The python was huge, and its long body curled up all over the picture, eerily hiding its head under the body. Again, the stains on the old print intensified the sense of death, already somewhat explicit in the dramatic black-and-white interplay of blood and shadows covering both animals.

Dead animals somewhere in former Portuguese Guinea. Private collection of Joaquim Barroca.

One day, the accumulation of images on one of the last pages of the album caught my attention. The thickness of one particular print struck me as odd, so I decided to take a closer look. I opened the acetate that covered the entire page. With the tip of my index fingernail, I carefully lifted the photo and realized that behind it was a perfectly hidden image. I had never seen it before. Its explicit violence echoes other accounts on Portuguese colonial war photography that I have been reading over the years (Medeiros, 2002, p. 103) – the bloody body of a young African man lying disorderly on the ground, beaten to death. The photographer twisted the shot to frame him completely. Right next to the body, I see the boots of four soldiers whose faces I cannot see. The dead man’s face is the most visible element in the image. His legs and feet lie behind him, disappearing into the dark background. His eyes are closed and swollen, his mouth slightly open, and his right cheek, terribly wounded, is turned up. From his left side, a deep traumatism runs from his left eyebrow to the tip of his nose and just below his right eye. His face is turned to the left, with his chin resting on his shoulder and his left cheek on the ground. His right arm extends to the edge of the frame; his hand is already out of the picture. The torso hides the other arm. The shirt is completely rolled up, leaving the belly almost uncovered up to the chest. Someone has decided to reach into his pockets. His sweater is stained with blood. Bloodstains on the floor show that someone dragged the body from left to right. The bloodstains, the lines they draw, are difficult to distinguish from the other marks on the damaged floor. The image is a garish display of lights and shadows, organized by diagonals that do not allow the eye to rest anywhere. The image screams death, war, and crime. There is confusion between the dark shadows, the dark skin, the dark blood, and the dark army boots and trousers. What was this picture doing in the safety of my home? (Figure 6).

Schema of a photograph of a dead young male in Piche, former Portuguese Guinea. Illustration by Daniel Barroca.

Years later, my father told me that he had bought this picture from another soldier when he arrived in Piche on the Eastern Front of the war. “Why would you want to buy a photograph like that?” I asked him angrily. He said that the photographer, a higher-ranking soldier, was selling it to the newcomers as a way to make some money out of team-building situations among the soldiers. But the distribution of these images also contributed to the intoxication and mobilization of the newcomers’ gaze (Comaroff & Comaroff, 1999, 2004). Thus, normalizing violence and killing by stunning recruits with shocking images, making them complicit in such violence just by looking at it ( Sontag, 2003; Ramos, 2020).

2.4 Into The Negative (Space)

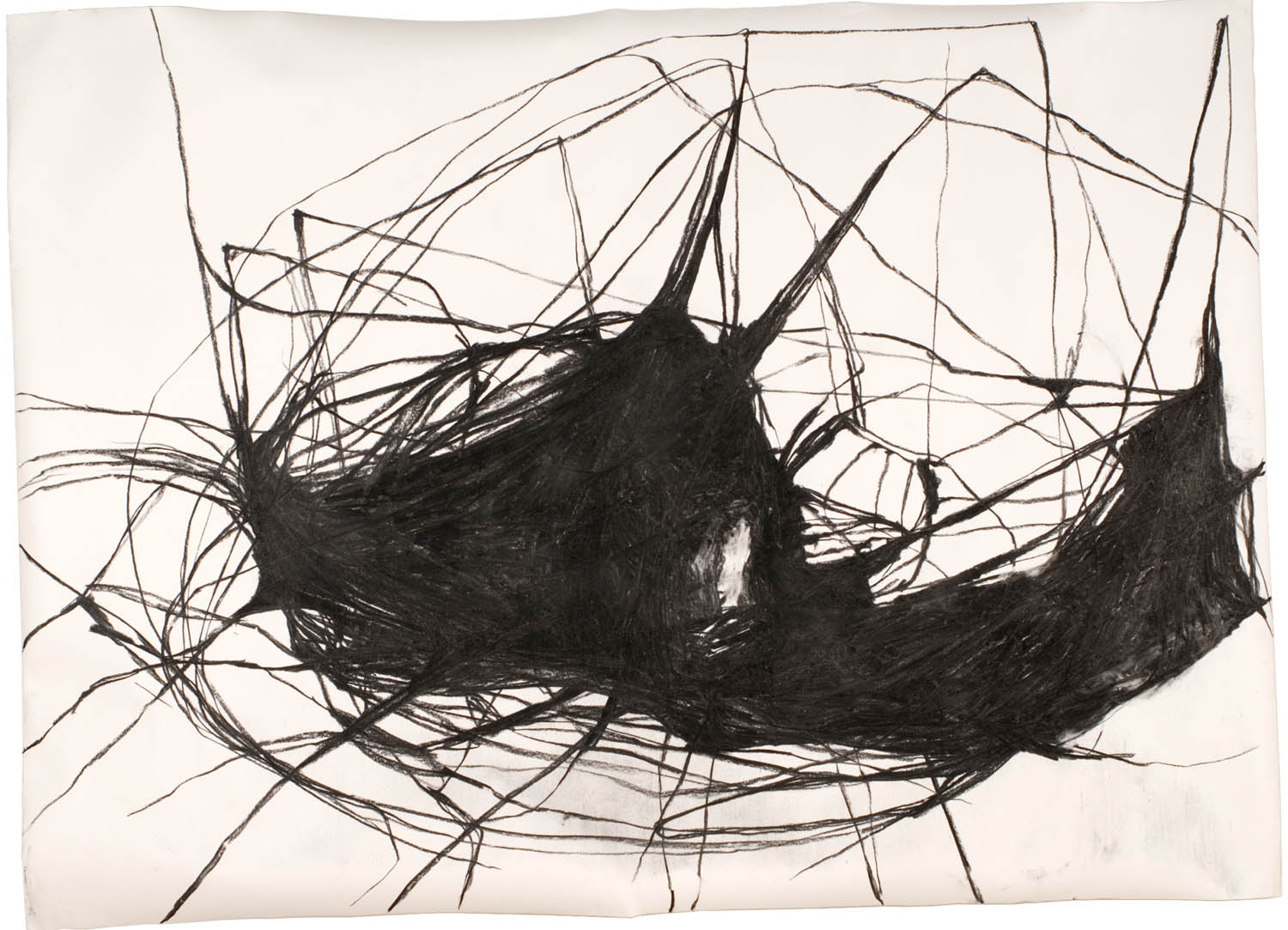

In his commentary on Nietzsche, Deleuze delves into the concept of force by analyzing the distinction between reactive and active forces, their positive and negative polarities, and their outcome in the idea of the inverted image (Deleuze, 2006). The inverted image is the negative of an image. In analog processes, photographers obtain the negative by photographing the real and then use it to reproduce and print the positive. Similarly, sculptors make casts of a form they wish to reproduce. These casts are the negatives that they fill with liquid materials that become solid to obtain the positives. The negative is a space, a void, that contains the matter that becomes the positive. The negative and the positive cannot exist without the other. But when we put them together, they cancel each other out and become a single block of matter. Let us say that the album, as an assemblage of tangible materials and images, is the negative space, and my gaze is the matter that fills it and becomes the positive (Figure 7).

War Drawing, Daniel Barroca, 2008.

The gaze is sucked into the empty negative spaces of the album and is shaped by them. To take on such a form could also be understood as being trapped in the void that the negative provides. A void that, for George Didi-Huberman, inspired by James Joyce and Merleau-Ponty, is inherent to the act of looking and thus constitutive of the person who looks (1998, p. 31). It would not be too much of a stretch to suggest that such a relationship between the gaze and what it observe is central to the concept of the anthropological image (Belting, 2014), and also relevant to understanding the notion of the punctum (Barthes, 2012), so often part of discussions of looking at photographs in many disciplines, including anthropology.

The emptiness of the negative space also has its own temporality. I write this piece primarily as an ethnographer. As such, I speak of what I observe, the forces that affect the present moment, referring back to Deleuze on Nietzsche (Deleuze, 1983), even when looking at memorabilia or archival material. I speak of my encounters with these materials in the present. I speak of how events that took place somewhere when I was not present come into my presence and make me think of the past in the present. The past becomes present – it is present. In this sense, the past is a construct of the present, not the other way around. The war album, its images, the stories around it, and the forces it activates are not lost in the oblivion of the past. They belong to the here and now. They are as constitutive of the present as any other image, thing, person, or voice that I can see, hear, and touch.

3 Death Is Not the End

3.1 Eastern Ghosts

The album connected me to a much smaller group of Portuguese veterans. All of them were in the same area of the war, more or less at the same time. That area is a triangle between Piche, Camquelifa, and Buruntuma in the east of the country, right next to Guinea Conakry, where the liberation movement had its bases during the war. An even smaller group within this already small unit of the Portuguese army was stationed on a bridge over a small river called Caium. Their mission was to protect the road between Nova Lamego, today’s Gabu, and Boruntuma, maintaining communication between the east and the center of the territory. In early 2016, I attended one of their meetings in Lisbon. I already knew two of these men from previous acquaintanceships. On this occasion, however, I was introduced to the whole group – João, Zé, Carlos, Orlando, Célio, Cláudio, and Bráz. I shook hands with three or four of them and nodded to the others. Ivan, the restaurant owner, arrived later than the others (Figure 8).

The bridge over the Caium River. Private collection of Joaquim Barroca.

Orlando was the most eccentric, constantly raising his voice and using old-fashioned slang for his barrack jokes. He covered his wrists with metal bracelets that jingled whenever he used his hands, a cross between a war veteran and an old hippie, with a couple of colored bead necklaces hanging from his neck into his slightly unbuttoned shirt, he was pretty good at getting laughs from the rest of the crowd. Still, the atmosphere was tense. People started conversations out of nowhere: “How’s work?”, “How’s the family?”, “Ah, I didn’t know your daughter got married!” Someone was loudly rubbing the palms of his hands on his arms. It was getting cold outside. Ivan, the restaurant owner, finally arrived from a bar across the street. He finally opened the restaurant and we went in.

I sat down between my father and Célio. He was a very gentle and thoughtful person, thin, with a thick white moustache and heavy glasses. The softness of his voice was very relaxing. He spent most of his time talking to me. I was the person sitting beside him. He told me about his group therapy after the war with a young doctor who had studied in the United States in the 1960s and had learned avant-garde treatments from the Americans during the Vietnam War. Célio confessed that although he could not deal with his war memories very well, he was much better than he was then.

Ivan started serving the red wine with some tasty appetizers – codfish biscuits, sliced ham, chorizo, and cheese. He was proud of my presence at their gathering. Bráz sat at a table on the other side of the room. He was the most mysterious of the group. His nickname was Rodinhas, little wheels in English, because he was the battalion mechanic. His figure was somehow strange. His arms were too short for his height, and he was the tallest of the group. His jaw moved diagonally to the right whenever he spoke or chewed his food. His voice had a strange tone, and he often spoke with his mouth full. Then he suddenly said: “after the war I stayed in Guinea-Bissau. Became a primary school teacher. got married and had some children. then I went to Algeria. Stayed there for a while. Then went to Cuba. Took a course on urban guerrilla.” Some of the others just chuckled. My father whispered, “He’s a little crazy.” His trajectory through his many afterlives was impressive, unpredictable, and engaging. Unfortunately, I have not been able to meet him since. I looked for him after a while, but he disappeared, and no one knew what happened to him.

The atmosphere gradually changed as we continued to drink, eat, and talk. Slowly, I felt that the sense of time was shifting. At some point, I looked at these people and instead of seeing the respectable fathers and husbands they were in their daily routines, I saw young brats in the bodies of older men telling silly jokes about a lost moment in their lives. It was as if they were back in the barracks, in the dining room I had only seen in the pictures they took in Portuguese Guinea during the war. They were no longer interested in the present moment of their lives. Instead, they were searching for a reconnection, or a collective re-tuning, to a past that was still quite mysterious to them and difficult to integrate into the wholeness of their lives. A time somehow outside of duration, as when Marc Augé speaks of ritual in his account of the temporalities of possession (Augé, 2004, p. 58). Possessed by themselves as young soldiers, repeating words, jokes, stories, physical interactions – body poses, handshakes, hugs – while sharing cigarettes, bottles of red wine, and whiskey, toward a collective emotional catharsis that ends in a photographic finale – a group picture like the ones I have seen all my life in my father’s album. Death is not the end.

3.2 The Bridge, The Threshold

April 2016. It was early morning in Gabu, the main Fulani town in Guinea-Bissau. We left the house and ran to the bus station. We found a big truck full of passengers on the way to Piche. The driver urged us to jump in the cabin while we were still negotiating the price of the trip. The truck was already moving before we had time to close the door. The road was bumpy and dusty for about 17 miles. The asphalt was from the colonial period, but all that was left were patches of tar that reminded me here and there of the stories I had heard in Lisbon about the army brigades that patrolled it during construction.

The main purpose of this trip was to get to the Caium Bridge, where many of the ghosts I had met in Lisbon, as figures of temporal multiplicity (Blanco & Peeren, 2013, p. 32), had been stationed almost 40 years ago. Once in Piche, we learned that there was no regular transportation to Camamjabá, the closest village to the bridge, so we decided to take a taxi to the site. My partner and I decided to tell the driver that we were visiting the bridge where my father spent time during the war to get him to lower the fare. But the effect was quite the opposite. Instead of building trust with the taxi driver, we started a rumor that quickly spread through the crowd. Suddenly, one after another, a number of elders approached me to tell me that they had been in the Portuguese army during the war (Rodrigues, 2022).

One of these men, Amadou Baldé, offered to come with us to the bridge. He said he had lived there as a young Fulani soldier in the Portuguese army during the war. From the start, he refused to speak Creole: “I went to the Portuguese school,” he said, “my Portuguese is much better than my Creole!” Baldé was obviously happy to come along. He could not stop telling stories about his time at the bridge. When we arrived, he explained how they built the barracks on top of the structure and how daily life took place in that reduced space. The bridge was much shorter and narrower than I had imagined. I had a hard time understanding how they were able to build a series of wooden and tin barracks and live for almost 2 years in such a small area. The entire infrastructure was covered with a thin layer of red dust that the wind blew into the cracks in the concrete. The iron fences were rusty and crumbling in places. It was the dry season, and the river was almost gone. It looked like a stinking pond without any signs of life.

There were two strange constructions on one of the sidewalks that crossed the bridge. One was the ruin of a small niche built by the soldiers in the 1970s to house a picture of the Virgin Mary. On the base, we can still read the inscription: “Nem só do pão vive o homem.” [“It takes more than bread for man to live.”] It is a ubiquitous Portuguese proverb, meaning that the human spirit needs as much nourishment as the body. The other was a small memorial to those who died on the site between 1972 and 1974. On the left side of the construction, they wrote the number of the company, 3346. and the company effigy, a humorous representation of a running ghost. Death is not the end.

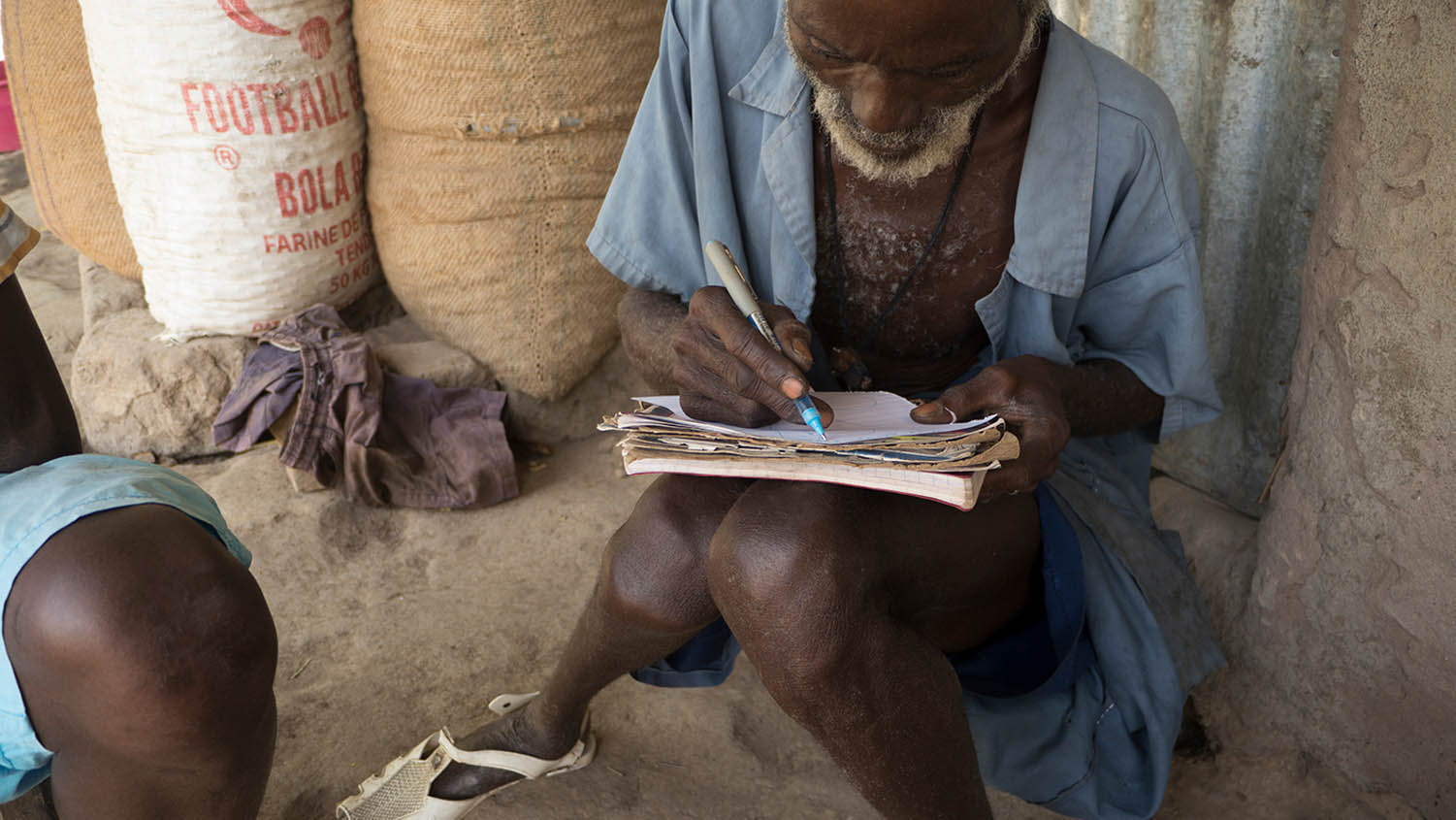

3.3 Victor Bor vs Van Gogh

Unal is a village in southeastern Guinea-Bissau, quite a distance from the Caium Bridge, where I met Victor Bor. Victor is known as the local djambakose, the name usually given to traditional diviners and healers. We made an appointment to meet him at his place of work, a small, dimly lit room in his mud house, to observe his divination. We arrived in the morning. A short line had already formed outside Victor’s house. We sat down and waited for our turn. After a while, Victor called us into his appointment room. We entered and sat down. Victor crouched down and brought out a tattered bag in which he kept his writing materials (Shaw, 2002). Before, I thought I had to start the conversation by telling him why I was there. So I decided to introduce myself as someone who wanted to study his work and whose father had been a soldier in the 1963/74 war. I wanted to hire him to cleanse my father’s past in the war, as I had heard other healers were doing in other parts of Guinea-Bissau. But as soon as I started talking, he immediately asked me to keep quiet, telling me that all he needed to know about me would come from reading his writings. After all, he was a soothsayer! He wrote some of his fragments on loose pieces of paper, some in notebooks, and some on thick pieces of cardboard.

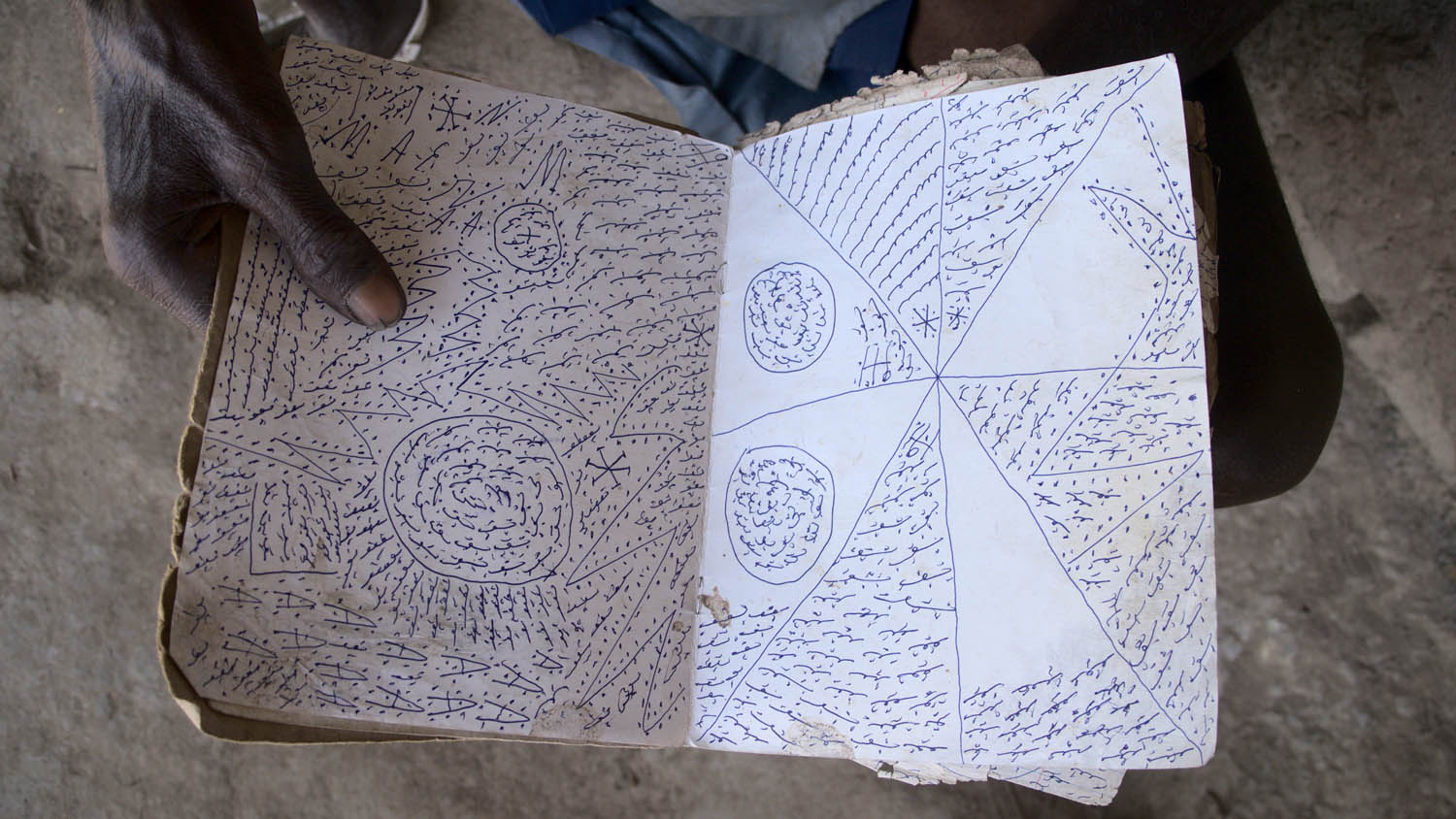

Victor opened one of the books with one hand and held a rosary with the other. As he counted the beads, his gaze moved across the composition, following a trajectory guided by the count, which seemed to lead him to become absorbed in the negative spaces within his writings, apparently in a similar way to what happened to me with my father’s album. As he counted, he nodded and occasionally pointed out some details in the drawing. After a while, he would turn the page, continue counting, and follow the paths in the writing. He acted like someone looking at a map and trying to find the way to a certain place. There was something about the number four, Victor counted sequences of four and his gaze changed direction. He later explained to me that he used cycles of 4 to structure his reading of the “map.”

It is obvious that this behavior was also part of the social performance that his community required of him as a djambakosse (healer). But even so, it was fascinating to watch the way he adjusted his gaze to the scale of the paper in front of him, counting the beads with his hand, looking at the drawing/writing in search of a meaning for my presence, or perhaps in search of some element that would allow him to dialogue with me as a patient. When I saw Victor Bor working with the space of his drawings in this way, I thought of my experience with my father’s photo album. It was then that I had the idea that when we look at and handle these kinds of objects, when we relate to them intimately, there is a negative space that opens up in front of us, which clearly grabs our attention and absorbs us in an immersive way. As discussed earlier, I would argue that this event shapes us as viewers in a way similar to making a positive from a photographic negative or plaster cast, but with the gaze.

When I asked him how he made these beautiful drawings, Victor told us that his deceased relatives would come into his dreams, sit in his mind, and dictate the writings. These writings seemed more like drawings to me. At least that’s how I felt about them. Texts written as if they were drawings? What were drawings to me, were texts to Victor, and this ambivalence of these materials places them in an interesting zone of hybridity that allows for a much more open analysis. Sometimes I use the term writings and sometimes drawings to talk about the same objects. Is that a conceptual conflict? In the end, it does not matter so much whether they functioned more like drawings or writings, what matters to me now is that they opened up spaces that held Victor’s attention within a negative space, much like when I described my relationship to my father’s war album.

In Victor Bor’s case, the negative space is the empty space that exists between the lines that make up his compositions, hybrids of writing and drawing, and in which Victor travels mentally as he counts his rosary, making his way through the complex configurations of his manuscripts. It is in these journeys that he finds the elements that allow him to provide answers to his clients’ problems. This space, into which his gaze is absorbed, or even sucked, is where Victor obtains the vision that lets him see beyond the surface of the paper. In other words, it is the space that shapes his sight to see beyond the visible. The space of his drawings/writings has a direct correspondence with the space of his dreams where the dead appear in his mind to teach him how to work out the processes that help him heal his community. In Victor’s case, the negative space is somewhat more complex than in the case of the relationship between my gaze and the photographic album of the war because it is a space that spans between the surface of his writings and the mental space in which Victor communicates with the dead.

Victor claimed no agency over the content he wrote with his own hands. On occasion, Victor also described his visions of explosions of light that he said Nhala [God] inflicted on him, provoking a sudden awareness. After these visions, he claimed to be seized by a clear and absolute view of everything – a kind of dying and coming back to life in the same persona, but ontologically transformed. Death is not the end. And suddenly he could see into people’s souls, heal them, and write in his own script because a thrilling vision gave him such power. As if he was no longer himself, but paradoxically more himself than ever.

I do not want to discuss Victor’s connection to Nhala [God] (Barroca, 2020), but his complex vision experience. I divide this experience into two distinct moments. First, Victor saw an overwhelming light that compelled him to perform several tasks. The light told him to heal others and to write. And it taught him how to do it and make it real and tangible. In a sense, the light became matter, a tactile experience. At the turn of the 1920s and 1930s, George Bataille wrote some manuscripts that became known as the Solar Texts (Bataille, 1994, 2007). In these essays, he reflected on looking at the face of the sun as a way of leaving human experience and being compelled to perform actions that he considered beyond human understanding. One of Bataille’s goals was to understand Van Gogh’s self-mutilation as the result of an intimate connection with the sun, rather than the common judgment that sees such an act as the result of a mental illness. For Bataille, the sun told Van Gogh to cut off his ear, and he did so only because he was a painter connected to forces that compelled him beyond his humanity. Bataille believed that the presence of the sun in many of Van Gogh’s paintings was evidence that his gaze, as a painter, was captured by the sun. Just as an overwhelming light captured Victor after he faced it in his dreams (Figure 9).

Victor Bor’s writings. Photograph by Catarina Laranjeiro.

Second, in his work as a healer, Victor Bor examined his visionary writings by simultaneously looking at them and touching them with his fingertips, as if reading a map. But this procedure mixes the senses, making the experience much more complex and sensual because the tactile informs the visual and vice versa. And one does not seem to distinguish between what is looked at and what is touched, making it a single phenomenological experience, “todo o visível é talhado no tangível” [all that is visible is engraved in the tangible] (Didi-Huberman, 1998, p. 31). Therefore, looking at Victor’s performance helped me to elaborate a more nuanced perspective on my experience of moving through the void of negative spaces in his writings and in my father’s war album from Guinea (Deleuze, 1983; Didi-Huberman, 1998). Furthermore, looking at his written pieces, I realized that either I was connecting with an artist similar to myself because I deeply identified with his work as an artistic endeavor, or the contact with Victor’s work revealed to me a more spectral side of my own artistic practice. It was as if his work showed me that just as he was captured by powerful apparitions of Nhala that he worked on in his writings or drawings, I was captured by ghosts (Blanco & Peeren, 2013) of the 1963/74 war that appeared to me in the photographs in my father’s photo album that I worked on through my artistic practice (Figure 10).

Victor Bor creating one of his writings. Photograph by Catarina Laranjeiro.

Victor Bor presents himself as a member of the Kyangyang – a modern religious community that combines Muslim, Christian and traditional elements (Callewaert, 2000; Sarró & Temudo, 2020). The role of dreams in the Kyangyang also has a parallel in the Muslim tradition: “Le message véridique arrive au dormer sous forme de parabole ou de symbole imagé” [A true message comes to the sleeper in the form of a parable or an imagistic symbol] (Lory, 2007, p. 85) through “l’apparition des défunts durant le sommeil.” [the apparition of the deceased during sleep] (Lory, 2007, p. 86). Islamic oneirocriticism – the science of dream interpretation practiced by Muslim scholars for centuries before Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams – was central to African Muslims, such as the Fulani Tijania marabouts neighboring Victor’s village, which he visited again and again. Since the time of the Prophet Muhammad, dreams have been important channels of divine revelation. Many Muslim leaders throughout history claimed to have had contact with the Prophet and other holy figures through dreams in which they received explicit divine messages (Lory, 2007, p. 76). Therefore, dreams, like most aspects of Muslim life, are thoroughly scrutinized by specialized scholars who decide, according to a strict set of rules related to Sharia law, whether these dreams are valid divine messages. If the dream was complete and symbolically coherent, they considered it valid. If it is fragmented, blurred, or confusing, they consider it demonic. Islamic clerical authorities took the interpretation of dreams very seriously, and over the centuries several authors wrote treatises on the subject (Lory, 2007, p. 91).

Victor was not under the scrutiny of any religious authority because his practice, associated with the Kyangyang, arose outside of any religious establishment, allowing him to use his divinatory creativity as he pleased. As a result, some writers consider the Kyangyang to be a product of modernity that only superficially appears traditional:

“It was as though, Balanta farmers, aware of their marginalization from the Bissau-Guinean public and political spheres (…) attempted, through conversion, to join the modern world they were explicitly expelled from. Through their exuberant religious imagination, they built or designed hospitals, schools, modern homes” (Sarró & de Barros, 2016, p. 13).

Others problematize it as a collective response to the war of liberation in a stateless country (de Jong & Reis, 2013; Laranjeiro, 2021). In other words, Kyangyang was a highly creative way to heal the trauma of the war of independence within the Balanta community in a country where the postcolonial state had virtually abandoned the rural areas and provided no safe places for public (mental) health care.

3.4 So, What About Safe Places?

In the safety of my childhood home, I found a collection of images from the war in former Portuguese Guinea, now Guinea-Bissau, that very clearly introduced the overwhelming power that images can have over people. Drawing on Deleuze’s commentary on Nietzsche (1983) and Didi-Huberman’s on James Joyce and Merleau-Ponty (1998), I tried to develop a theoretical argument, with a phenomenological bent, about the immaterial experience of a visual assemblage together with the tactile experience of its materiality. Or, in the terms I explored in this work, the negative spaces that such a relationship induces, inconspicuously, within our safe spaces.

To be clear, the negative space is not safe. It’s a space where we can unexpectedly see terrible things, that change the course of our lives, like the photograph of the guerrilla who was beaten to death by Portuguese soldiers in Piche during the colonial war, somewhere in the early 1970s (Figure 6). The negative space is a space that transforms those who experience it and is therefore a dangerous space, of spectralities and shadows, of disorientation, which opens up paths to strange temporalities where the past becomes suddenly and violently present. A past that, despite appearing spectrally, is paradoxically concrete in the ways it makes itself felt, whether through the sight of hidden photographic prints, in my case, or voices that reveal healing abilities, as in the case of Victor Bor. The intellectual exercise of this text allowed me to reflect on the complexity of the relationship between me and the album of war photographs I found in my house as a child, compared to the relationship between Victor Bor and his writings. I felt compelled to make this comparison when I met Victor in his Bissau-Guinean village of Unal and realized that he was as deeply affected by the tactile experience of his visual works as I was by my war album.

To better understand the links and connections between me and the war pictures, I decided to do some ethnography among some of the men who appear in the album and who went to war with my father. This ethnographic experience was followed by a trip to Guinea-Bissau, where I visited the area in the east where they were stationed during the war. Once there, I realized that their group was called the Eastern Ghosts, which is an uncanny coincidence when we consider that Victor Bor claims to speak to the dead when he sits and creates his fascinating manuscripts. In different ways, we both spent a lot of time listening to ghosts. Ghosts have a very tangible presence through objects like my war album and Victor’s writings – objects that have an enormous power of attraction and provide openings into the negative space where we are confronted with the densest and darkest aspects of a war that took place somewhere in time. The pull of these objects, such as the album and Victor’s writings, keeps us connected to their inner spaces. We cannot just get rid of them, because in some uncanny way, they give meaning to our lives and feed our ways of creating (un)safe zones where we can dwell. Death is not the end.

Acknowledgements

Victor Bor, Joaquim Barroca, Catarina Laranjeiro, Tânia Ganito, Ricardo Roque, Nancy Rose Hunt, Richard Kernaghan.

-

Funding information: This chapter derives from my PhD research funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interests.

References

Augé, M. (2004). Oblivion. University of Minnesota Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Barroca, D. (2020). Terramoto, sombra, corpos explosivos: Imagens do Kyangyang da Guiné-Bissau. Convocarte, Revista de Ciências Da Arte, 10(Arte e Loucura), 241–256.Suche in Google Scholar

Barthes, R. (2012). Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. The Noonday Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bataille, G. (1994). A Mutilação Sacrifial e a Orelha Cortada de Van Gogh. Hiena.Suche in Google Scholar

Bataille, G. (2007). O Ânus Solar (e outros textos do Sol). Assírio & Alvim.Suche in Google Scholar

Belting, H. (2014). An anthropology of images: Picture, medium, body. Princeton University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Benjamin, W. (2008). Little history of photography. In The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility, and other writings on media. Harvard University Press.10.2307/j.ctv1nzfgns.36Suche in Google Scholar

Blanco, M. D. P., & Peeren, E. (Eds.). (2013). The spectralities reader. Ghosts and haunting in contemporary cultural theory. Bloomsbury.Suche in Google Scholar

Callewaert, I. (2000). The birth of religion among the Balanta of Guinea-Bissau. Department of History of Religions, University of Lund.Suche in Google Scholar

Comaroff, J., & Comaroff, J. (1999). Occult economies and the violence of abstraction: Notes from the South African postcolony. American Ethnologist, 26(2), 279–303.10.1525/ae.1999.26.2.279Suche in Google Scholar

Comaroff, J., & Comaroff, J. (2004). Criminal obsessions, after Foucault: Postcoloniality, policing, and the metaphysics of disorder. Critical Inquiry, 30(4), 800–824.10.1086/423773Suche in Google Scholar

de Jong, J., & Reis, R. (2013). Collective trauma processing: Dissociation as a way of processing postwar traumatic stress in Guinea Bissau. Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(5), 644–661.10.1177/1363461513500517Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G. (1983). Nietzsche and philosophy. Athlone Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G. (1987). Introduction: Rhizome. In A throusand plateaus capitalism and schizophrenia (pp. 1–25). University of Minnesota Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G. (1991). What is a dispositif? In Michel Foucault Philosopher (pp. 159–168). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G. (2006). Active and reactive. In Nietzsche and philosophy (pp. 39–74). Columbia University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Didi-Huberman, G. (1998). O que vemos, o que nos olha. Ed. 34.Suche in Google Scholar

Flusser, V. (1998). Ensaio sobre a Fotografia. Relógio D’Água.Suche in Google Scholar

Hirsch, M. (2016). Family frames: Photography narrative and postmemory. Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hunt, N. R. (2006). A colonial lexicon of birth ritual, medicalization, and mobility in the Congo. Duke University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ingold, T. (1991). Becoming persons: Consciousness and sociality in human evolution. Cultural dynamics, 4(3), 355–378.10.1177/092137409100400307Suche in Google Scholar

Ingold, T. (2010). Bringing things to life: Creative entanglements in a world of materials. Realities Working Papers, 15.Suche in Google Scholar

Laranjeiro, C. (2021). Dos Sonhos e das Imagens: A Guerra de Libertação na Guiné-Bissau. Outro Modo.Suche in Google Scholar

Lory, P. (2007). L’interprétation des rêves dans la culture musulmane. In Coran et Talisman (pp. 75–94). Karthala.Suche in Google Scholar

Medeiros, P. D. (2002). War pics: Photographic representations of the colonial war. Luso-Brazilian Review, 39(2), 91–106.10.3368/lbr.39.2.91Suche in Google Scholar

Pina-Cabral, J. D. (2018). Modes of participation. Anthropological Theory, 18(4), 435–455.10.1177/1463499617751315Suche in Google Scholar

Pinharanda, J. (2013). Os que vão morrer te saúdam. In Uma linha raspada (pp. 2–7). Câmara Municipal de Vila Nova da Barquinha.Suche in Google Scholar

Pinto Caldeira, C. R. (2019). O Corpo nas imagens da guerra colonial portuguesa: Subjetividades em análise. Galaxia, 40, 17–40.10.1590/1982-25542019140716Suche in Google Scholar

Plato. (2017). The allegory of the cave. In B. Jowett (Trans.). Enhanced Media.10.4324/9781315303673-22Suche in Google Scholar

Ramos, A. (2020). The Fugitive Image: Colonial Terror and Contemporary Art. (OBS*) Observatório, Intermedialidades em Imagens (pós) coloniais, Special Issue, 73–87.10.15847/obsOBS0001815Suche in Google Scholar

Rodrigues, S. P. (2022). Comandos africanos: Memórias e testemunhos da Guerra Colonial e da descolonização da Guiné-Bissau. Universidade de Coimbra.Suche in Google Scholar

Sarró, R., & de Barros, M. (2016). History, mixture modernity: Religious Pluralism in Guinea-Bissau Today. In P. Chabal & T. Green (Eds.), Guinea-Bissau: Micro-State to Narco-State. Hurst Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Sarró, R., & Temudo, M. P. (2020). The shade of religion: Kyangyang and the works of prophetic imagination in Guinea-Bissau. Social Anthropology, 28(2), 451–465.10.1111/1469-8676.12768Suche in Google Scholar

Shaw, R. (2002). Memories of the slave trade: Ritual and the historical imagination in Sierra Leone. University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226764467.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the pain of others (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.10.3917/dio.201.0127Suche in Google Scholar

Spyer, P., & Steedly, M. M. (2013). Images that move. N.M.: SAR press.Suche in Google Scholar

Stoler, A. L. (2013). Imperial debris: On ruins and ruination. Duke University Press.10.1515/9780822395850Suche in Google Scholar

Taussig, M. T. (1987). Shamanism, colonialism, and the wild man. A study in terror and healing. The University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226790114.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Toren, C. (2012). Imagining the world that warrants our imagination – The revelation of ontogeny. Cambridge Anthropology, 1(30), 64–79. doi: 10.3167/ca.2012010101.Suche in Google Scholar

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (2016). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262529365.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Vicente, F. L. (2014). O Império da visão: Histórias de um livro. In O Império da Visão. Fotografia no Contexto Colonial Português (1860–1960) (pp. 11–30). Edições 70.Suche in Google Scholar

Yates, F. A. (2014). The art of memory. The Bodley Head.10.4324/9781315010960Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective