Abstract

This article performs a close reading of HAVEN, a 2023 digital video installation by James Newitt. It analyses the way in which the work discusses issues around privacy, surveillance, and the management of digital data. Newitt’s work tells the story of how an abandoned anti-aircraft defence tower off the Suffolk coast in the North Sea was turned first into a pirate radio station and then into a data haven; a collection of servers meant to avoid early Internet regulation. Investigating the many ways in which HAVEN can be understood as noisy, a concept borrowed from Michel Serres, this article proposes that Newitt’s work is at its most generative in its suggestion of a theory of (auto-)immunity that complicates contemporary discussions of privacy centred on visibility (Derrida, Foucault). Moving away from a model of surveillance, and drawing on the work of Philip E. Agre, this text seeks to understand the dynamics of power made visible in HAVEN with reference to the notion of capture. The article proposes that HAVEN’s poetics are of interest both aesthetically and in terms of content as they examine a contemporary territorial logic of the Internet and its connections to empire.

1 Introduction

Haven

noun

noun: haven; plural noun: havens

1. a place of safety or refuge.

2. an inlet providing shelter for ships or boats; a harbour or small port.

HAVEN, 2023, is James Newitt’s most recent work that currently travels galleries and art spaces around the world in the form of a three-channel video installation. The work, which has a runtime of roughly 35 min and features a mixture of digital video footage, digitally rendered material, as well as archival film footage, concerns itself with the materiality of memory and memory loss, both embodied and in the form of digital data stored on computer servers. HAVEN is set on a platform that used to serve military purposes of air defence during World War II located just off the Suffolk coast in the North Sea. The platform was originally built in 1943 in international waters by the British and was occupied by Royal Navy personnel through 1956.[1] In 1967, the platform had become occupied by civilians who decided to found a pirate radio station there and declare the platform a sovereign territory separate from the United Kingdom under the name Principality of Sealand. As a result, a new micronation was born.[2]

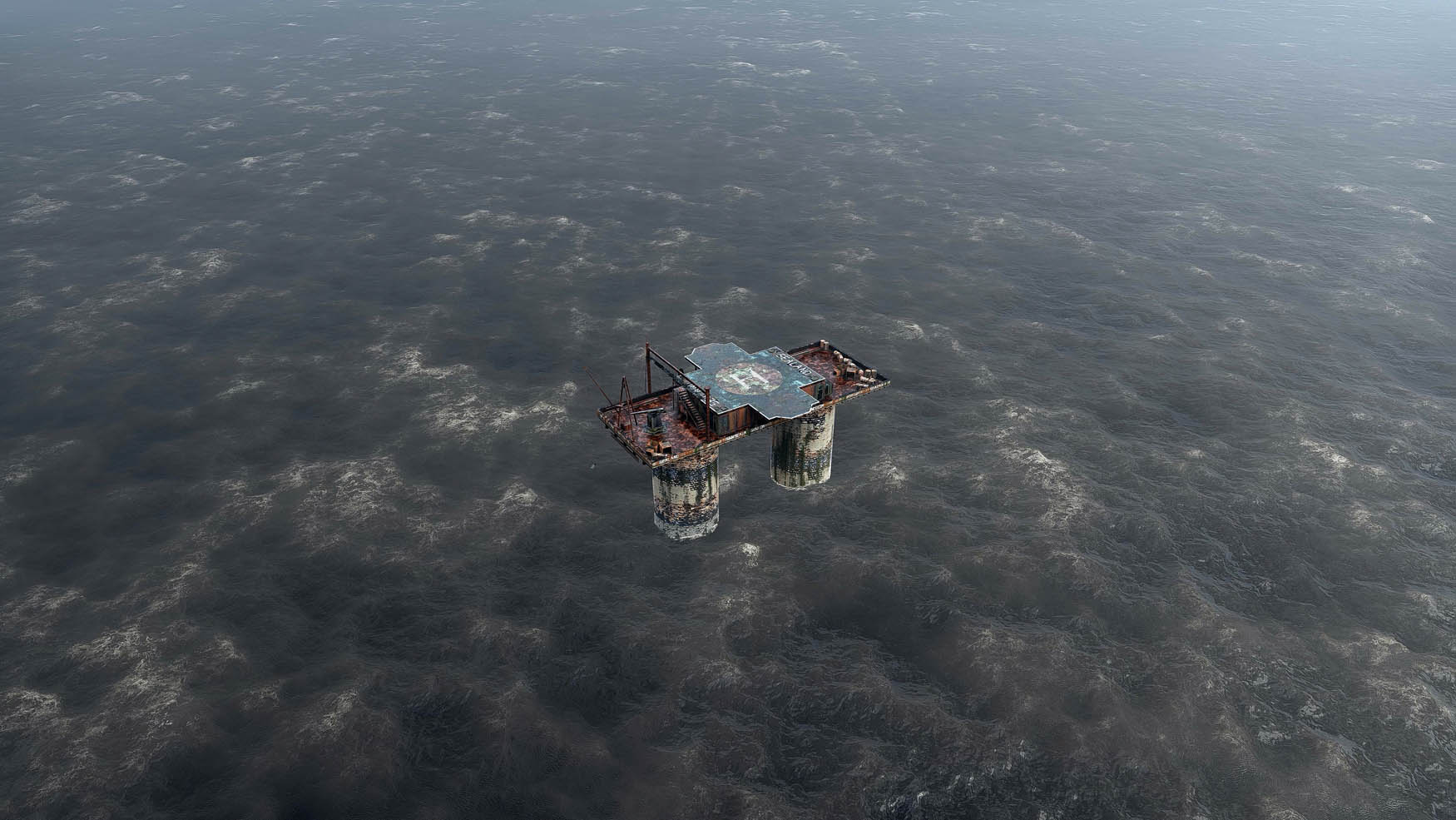

The artwork that I will be looking at is concerned with the history of that space and the different ways in which it has been used over time. HAVEN tells the story of how the platform was occupied and declared independent from the UK by a family who wanted to broadcast pirate radio, and of how it became, later on, the location of a data haven where information was stored on servers in an attempt to circumvent territorial control and jurisdiction. The work deals, then, with the negotiation of a bellicose and territorial history of the platform on the one hand, and the eventual utopian project of producing a safe place on the other (Figure 1).

“Digital rendition of the platform as seen from above in HAVEN.” Credits: “James Newitt, HAVEN, 2023, video still”.

By way of a close reading that centres around my own experience of watching HAVEN – both affective and analytical in nature – this article seeks to confront the installation with the concept of immunity. I thus try to gauge not only how notions of space and place made popular by authors like Yi-Fu Tuan and Michel de Certeau operate in Newitt’s work, but to propose, instead, that HAVEN produces an understanding of place and safety that is tuned to a logic of data and digitization always already enmeshed with what Philip E. Agre has coined a model of capture or what Michel Foucault before him referred to with the notion of security (Agre, 2003; de Certeau, 2002; Foucault, 2009; Tuan, 2002). The reading will proceed chronologically, that is to say – it will follow the rhetorical structure of the work. I have chosen this approach because it highlights the way in which HAVEN narrativizes, sorts, and structures its logic on the basis of what Lev Manovich has referred to as the symbolic form of the database (Manovich, 1999, p. 81).

The argument is that HAVEN employs an audio-visual rhetoric of parasitical noise as theorized by Michel Serres in order to speak about the ways in which the utopian project of creating a safe place, in this case a data haven, is always already auto-immune in the Derridean understanding of the word (Derrida, 2002, 2005; Serres, 2007). Steering away from the visual metaphors associated with the paradigm of surveillance, this article seeks to understand the power dynamics implicit in the relationship between this data haven and the infrastructure of the Internet through the concepts of noise, immunity, and capture.

The argument is that both the content and the aesthetics of HAVEN show how the Internet must not be understood as an essentially extra- or anti-territorial network of nodes and edges perverted by territoriality and surveillance, but as a territorial dispersion of ever-new places.[3] This text examines the data haven as one specific instance of such a place that seeks to situate itself at a distance from territory with reference to the paradoxical notion of legal immunity. HAVEN shows, I contend, how the colonial under- and overtones that come with appropriating a former air defence platform originally erected to defend the UK are not incidental to the way the Internet operates, much less immune to its logic of private property, but produce a noise that makes visible a logic of capture on which the data haven parasites.[4] The creation of a safe place from which data can circulate without obstruction at once disturbs the logic of territoriality but territoriality itself remains the bread and butter of the data haven, much like a fantasy of the Internet as a potentially anti-territorial interconnection of nodes feasts on the figure of the data haven as a metaphorical replacement for the free floating ship, symbol not only for ever increasing interconnectedness but also for discovery and the expansion of empire at the same time. Indeed, Foucault writes in his text on heterotopias to which I will return at the very end of this essay:

[…] the ship is a piece of floating space, a placeless place, that lives by its own devices, that is self-enclosed and, at the same time, delivered over to the boundless expanse of the ocean, and that goes from port to port … all the way to the colonies in search of the most precious treasures that lie waiting in their gardens[…] (Foucault, 1998, pp. 184–185).

If the safe space in HAVEN can indeed be read as a metaphorical ship, it is at the same time and much more literally, a small port. A port to which connections can be made digitally and which operates as a node within a wider network of places, some secure and others much less so. Tuan writes at the opening of Space and Place: “Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other.” (Tuan, 2002, p. 3). Implicitly this statement indicates the colonial fantasy to move out into a supposedly undefined and uncontaminated space in order to find a freedom there that nevertheless turns into security as soon as it has been captured and transformed into the safe place of the colony.

HAVEN shows how freedom from regulation predicated on immunity invariably runs the risk of becoming autoimmune. This text argues that safe places like the data haven in Newitt’s work are never safe in general but always in relation to a wider grammar that structures both the utopian fantasies of defenders of freedom on the Internet and those of large multinational corporations like Microsoft and Google who seek to immunize themselves against governmental oversight and regulation.

2 Parasites Boarding the Ship

HAVEN opens with a fight aboard the anti-aircraft platform in the North Sea. A female voice speaks of how her husband, Roy, came to this tower on a boat, with the intention of finding a place to broadcast pirate radio from. Upon arrival, Roy declared the gun tower occupied and offered it to his wife as a gift, introducing both the economy of appropriation and the logic of gift-giving. The footage we see is black and white. It features a woman looking into a mirror and making a bed. The narrator speaks about moving her family into the tower and declaring independence from Britain. She explains that they named the tower Sealand and that they gave it the motto e mare libertas; from the sea, freedom.[5]

HAVEN invites me to think about freedom through independence, strategies of territorial military defence, and the meaning of ownership through occupation. The audience is shown video footage from the air looking down on the structure that is made up of two large round columns rising from the water, featuring a rectangular platform top, and a few buildings on top of that, from which the occupants can look out over the North Sea.

The narrator proceeds to explain that as time passed the family was approached by three Americans around the turn of the millennium who wanted to create the first data haven in the world and locate it in Sealand. “They called themselves cypherpunks” the voiceover tells the audience, and the audience learns that they said “as governments tighten regulations on the internet, the data haven would be a place to defend data-privacy.” (HAVEN 03:00-04:00). Her husband, Roy, agreed to turn this extra-territorial, or newly territorial, structure into a location that would operate as a giant server; part of what we would, today, refer to with the aerial metaphor of the cloud.[6]

Sealand, first imagined by Roy as a pirate radio broadcasting station become family home, thus came to function as a host on which this data haven could parasite under the protection of international, and as per the motto, “free” waters. This protection is the protection to remain free from the regulation that the host, Roy and his family, had provided for themselves when they made sure to declare independence and freedom from British rule.[7] A protection structured on the idea of legal immunity, where immunity is understood as not having to comply with rules and regulations that others do have to comply with, whilst still being the beneficiary of some of the provisions usually only conferred upon those who do have to comply with those same obligations. But perhaps it would make more sense to suggest that the real host here is not Roy’s Sealand, but the anti-aircraft gun tower itself on whose structure Roy and his family were parasiting in the first place. After all, the structure was already there before Roy’s arrival, and in transforming the space he found there into a place where a radio station could be set up, he started to render the former logic of militarized aerial defence noisy in the sense that the very connection to the air became reconfigured in terms of broadcasting outside of territorial regulation instead of warfare in defence of British territory. And as the host shifts position, so does the position of the parasite (Figure 2).

“Aerial defence gun pointing at the sky in digital rendition as it appears in HAVEN.” Credits: “James Newitt, HAVEN, 2023, video still”.

When Serres defines the parasite as noise,[8] drawing on the double meaning of the French word parasite which refers to static that interrupts a signal and on the meaning known to English audiences,[9] he remarks that there can be no signal without noise already accompanying the message. In other words, noise, for Serres, is always already productive and interruptive; at the same time, it parasites on the signal and structures the signal; it eats its host but starts to live in it. This living-in is both consumption and structuration. The positions of parasite and host are never stable. What counts as a meaningful signal and what counts as noise remains a question of perspective. Cary Wolfe notes how Niklas Luhmann’s figure of the observer is both productive of a transformation in the system and interruptive of its workings. Similarly, noise paradoxically produces the signal which it also interrupts. It is its precondition, like the white space[10] on a piece of paper that interrupts the steady stream of words and operates as the necessary precondition for those words to become meaningful (Luhmann, 2004, pp. 146–147; Wolfe, 2007, pp. xxi–xxiii). Serres puts it this way:

The noise temporarily stops the system, makes it oscillate indefinitely. To eliminate the noise, a nonstop signal would be necessary; then the signal would no longer be a signal and everything would start again, more briskly than usual. Theorem: noise gives rise to a new system, an order that is more complex than the simple chain. This parasite interrupts at first glance, consolidates when you look again. The city rat gets used to it, is vaccinated, becomes immune. The town makes noise, but the noise makes the town. (Serres, 2007, p. 14).

I am presented with noise, immunity, inoculation, territoriality in the form of a town, and circulation in the shape of a signal that does not conform to the logic of a chain.

It is clear how the occupation of a gun tower by Roy and his family in order to produce a pirate radio station is a parasitical operation through which a structure meant for territorial defence is being consumed and restructured so as to work against the logic of British territoriality that it was meant to defend in the first place. The radio waves produced by the pirate station are a second form of noise if seen from the perspective of the British Office of Communications (Ofcom) which “regulate the TV, radio and video on demand sectors, fixed line telecoms, mobiles, postal services, plus the airwaves over which wireless devices operate” (Ofcom, 2023). This second form of noise is soon followed by a third when the cypherpunks enter and come to live in their host, consuming the “freedom” of the newly founded Sealand and introducing a problem of private property into the utopian fantasy that Roy and his family had imagined. They generate a fourth kind of noise within the larger system of the Internet and its regulatory mechanisms, which prior to the emergence of the cloud as an overarching paradigm for data storage, can be thought of according to Daniel van der Velden and Vinca Kruk as: “[…] a patchwork of city-states, or an archipelago of islands. User data and content materials are dispersed over different servers, domains, and jurisdictions (i.e., different sovereign countries).” (Van der Velden & Kruk, 2012, n.p.). The server on Sealand renders sovereign territoriality noisy at the very same time that it consolidates that territoriality, as we will see in a moment. But there are other instances of noise in HAVEN too, when, later on in the work, issues of memory loss and modes of communication that are continually interrupted appear and disappear. Parasites are abundant in the content of the work.

Lev Manovich uses the concept of the database as a symbolic form that allows one to convey meaning in a non-narratological way. The types of noise outlined above, I want to argue, can be thought of as parts of a symbolic reservoir from which HAVEN draws its meaning. The database in this sense shapes the content on which HAVEN is structured. The types of noise outlined above are so many data points that find themselves selected and ready to be transferred to an audience, and are as such part of the message that HAVEN conveys (Manovich, 1999, p. 81). If a signal is a matter of selecting data points, then noise arises from what has remained unselected. Indeed, HAVEN can be read as a collection of meaningful data points selected from a larger unselected mass of data. What might be called – in a more Deleuzian vocabulary that appears for example in a short text titled “Bergson 1859–1941” coincidentally linking the notions of memory, duration, and difference – the actualization of the virtual, where the virtual operates as a stand-in for noise (Deleuze et al., 2004, p. 29). HAVEN as an art installation paradoxically selects data points from the real-life events, documentation, and archival footage that it draws on while at the same time presenting some of those data points as partially unselected, forgotten, uncertain, and dubious. When the unselected resurfaces, it appears as noise. Defined in this way, noise is data that should not have been given. A gift that was never yours to give. A platform offered as property to his wife by a husband who never owned it. This way of phrasing things, however, introduces a problem inherent in speaking about noise: as soon as I say that the noise referred to above can be read as a selection on the basis of which HAVEN becomes meaningful, it seems to disappear. Selection and noise are, it turns out, antithetical to one another. Noise has already become the signal, and the occupation of the platform, the broadcasting of the pirate radio station, and the subsequent transformation into a data haven are all part of a message that is conveyed to us in Newitt’s work.[11] These parasites interrupt, as Serres said, but immediately consolidate upon the second inspection. The notion that a database operates as a structured collection of data means that those pieces of the database that are not referred to at any particular moment are part of the structural whole at the same time (Manovich, 1999, p. 81).

If it makes sense to think of the noise outlined above as part of a database, it makes sense as well, to think about the more formal elements of HAVEN in terms of how those data points are presented in audio-visual form. The same problem arises again, and Niall Martin usefully comments on the way in which the aesthetics of noice in their relation to virtuality carry forth a tension:

More generally it presents us with the paradox of the emergent: noise as the ‘outside’ of signal is a virtual property of all media but ceases to be noise when it is actualized as an aesthetic component within, for example, an image or as a marker of an aesthetic paradigm. (Martin, 2019, p. 246)

In HAVEN, aesthetic noise is produced through digital renderings that come undone, desktop error sounds that figure as interruptions to the narrative, and the appearance of glitches introduced throughout the work by Newitt. What first appears on the level of the database re-surfaces in the aesthetics of HAVEN to make the viewer aware that no signal will be produced by the pirate radio station or through the data haven that will not also already be noisy (Figure 3).

“The platform rendered noisy in HAVEN.” Credits: “James Newitt, HAVEN, 2023, video still”.

This more formal kind of noise, however, also seems to run counter to the noise of the database in that it destabilizes the discourse of the utopian vision of those working on the tower. What first appeared as a noisy interruption to the logic of the Internet as a “patchwork of city-states” is interrupted once more on this aesthetic level in HAVEN when immediately following the introduction of the cypherpunks, the image cuts to pixelated CGI footage that uses a glitch aesthetics. The voiceover tells us that when the operators of the data haven suggested that they would start hosting pirated materials from the tower, the family decided to destroy their servers and disallow the data haven to continue its operations. We are five minutes into the work when we are faced with three different shots of sky – the metaphorical cloud returning to its literal state here, in anachronistic fashion – and what follows is archival footage from inside the tower: stairs, the platform, people talking, hallways, servers in lockers, the sense of entering a vault. We hear the sound of the wind blowing, and a screeching sound, punctuated by the computerized “thump” that I recognize from clicking a button on a Windows operating system that I’m not supposed to be clicking on.

Both the pixelation and the error sound interrupt the idea of a data haven that might escape the regulatory force of the Internet. One type of noise is rendered noisy by a second type of noise, and the first parasite starts to be eaten by the second. The aesthetics employed in HAVEN make visible, I contend, not that the utopianism of the cypherpunks and their discourse on privacy and freedom from oversight was fraught to begin with, but that its noisy interruptions to the logic of the Internet are both interruptions and preconditions for its consolidation. There is database noise, and there is aesthetic noise but the confrontation between the two amounts to a meditation on the noisiness of the data haven as part and parcel to the Internet: by consolidating all the noise within, HAVEN reflects on the way the data haven itself supports a system in which regulation and territory remain central. The data haven seeks immunity from the system of the Internet.

3 Immunity and Territoriality

The data haven seeks immunity to the system of the Internet; it is the noise that structures its surroundings. This is to say that the data haven is the precondition for the Internet to exist as a modern territorial collection of places thoroughly dependent on what Roberto Esposito has called, in an attempt to make sense of Michel Foucault’s concept of biopower which connects the otherwise seemingly foreign realms of biological life on the one hand with juridical power or right on the other, the “immunitary paradigm” (Esposito, 2006, p. 24). I will return to a precursor to this notion of biopower in a moment through the notion of security closely related to that of immunitary life, as Nik Brown also notes in his Immunitary Life when he writes:

Here [in the work of Esposito, Sloterdijk, and Derrida], immunity is seen to resonate with cultural and historical shifts away from ‘community’ or the ‘commons’ and towards biological technologies of personal protection, security, isolation, defence and withdrawal. … But these literatures go beyond a simple dualistic binary pitching good against bad, community against immunity, the open against the closed. Instead, they take account of the complex interpenetrations and entanglements through which immunity makes life both possible and perilous. (Brown, 2019, p. 3).

Both Esposito and Brown produce a connection, then, between immunity on the one hand and specific forms of power on the other, predicated on the idea that immunity as a concept is related to a notion of life or bios. I would like to reinforce the connection to security as a specific shape that power takes, which can also be referred to with the notion of capture as we will see in a moment, but leave aside the popular idea that immunity is necessarily related to biological life.

When claiming that immunity is one of the preconditions for a concept of modern territorial space to arise, I am relying on a history of the notion of immunity outlined by Ed Cohen once more in the context of his work on immunity in relation to biomedicine. That context is foreign to this discussion of HAVEN because it deals with biomedicine and the metaphors that shape that discipline. Yet the conceptual apparatus that Cohen employs becomes strangely familiar to my current work when taking into consideration that the notion of the parasite is a metaphor, at least in its English invocation, borrowed by Serres from biology and incorporated into the language of information theory. Cohen points out that immunity travels from law into biomedicine and that its early conceptualization predates the biomedical one by around 2,000 years, which permits me to, for the moment, speak about immunity not in relation to life, but in relation to the data haven in HAVEN and the way it interfaces with contemporary understandings of Internet freedom.

Cohen shows that immunity in its legal meaning derives from the negation of belonging to a municipality, which itself exists as a form of belonging situated at a distance from more conventional territorial belonging as defined by a right of birth which ties one to a specific territorial place usually conceptualized through the notion of soil. The history that Cohen is referring to here is that of Ancient Rome in which a shift took place as a result of the rise of a new form of territorial government linked to the foundation of the first municipalities. These newly defined places were at once part of the Roman Empire but their citizens were not considered to have become citizens as a result of belonging to Roman soil. A new kind of belonging was invented, rooted in the obligation to adhere to Roman law and granting the adherents to it a set of rights similar to those whose belonging first arose by right of birth. It is for this reason that Cohen can claim that the rise of Roman municipalities brings the former understanding of territorial belonging as rooted in a notion of soil to a crisis (Cohen, 2009, p. 42). Immunity, then, becomes the mark of this contradiction between two opposing forms of belonging, where the im- signifies the negation of the obligations that the citizen who belongs to a municipality of Rome has. In other words: one can belong without belonging either to the soil or to the juridical realm of the Empire whilst at the same time profiting from the infrastructure that the Empire nonetheless affords.[12]

Cohen writes that immunity “uses exceptions to the law to demonstrate that the law remains without exception” and notes how it signals a surplus of attachment to the State outside of the obligations that would make one part of its territory (Cohen, 2009, p. 43). In our case, the data haven can be read as an attempt at remaining immune to the regulatory force of territorial jurisdiction that takes place on the Internet, all the while operating only in so far as it makes use of the infrastructure to which it nonetheless belongs. To rephrase Cohen’s interpretation of Derrida: the Internet contains a data haven that also contains it.[13] In the text cited above, Van der Velden and Kruk note the following:

The combined rights to a free flow of information, freedom of expression [sic], and freedom from censorship, have been described as a compound right to ‘internet freedom’. Indeed, Google’s Wael Ghonim at the beginning of this story suggested that unhindered access to, and use of, the internet enables the liberation of a society. (Van der Velden & Kruk, 2012, n.p.)

It is precisely this kind of “freedom” that the cypherpunks want to defend and affirm in their efforts at creating a safe place that would be immune to the obligations of an empire “on which the sun never sets” in an anachronistic reference to the British Empire of which the tower had first been part, and the metaphorical empire of the Internet as it consists of “an archipelago of islands” (Van der Velden & Kruk, 2012).

And if my reference to the British Empire seems farfetched at first, it becomes substantially less so when read in conjunction with the following fragment from HAVEN that appears a little later in the work. We are presented with a server room and a glitchy voiceover speaks about how the cypherpunks installed the servers in Sealand, and how they made sure that there would be time to destroy the hardware should there be a security breach to guarantee that the information stored there could be made irretrievable for law enforcement agents. The voice explains that there was a difference of opinion between the family who originally “discovered” or claimed Sealand as an independent territory, and the cypherpunks. There is talk of security software installed to ensure that as soon as there is a breach, the servers would start deleting information installed on them. We hear that “the software secondly gave the data haven control of its own memory.” (HAVEN 16:20). The audience is told about the issue of pirated materials being installed, and the difference of opinion between the family and the cypherpunks, this time told from the perspective of the latter. The voice renders the situation by saying that the family had already decided to “nationalize the data haven,” and that “the father was losing his memory” (HAVEN 17:00-17:03).

The footage, still CGI, is now of the insides of the tower. We hear the voice of a woman speaking about rain and memories, observational in tone as the imagery shows windows, bathrooms, and the inside of rooms. The woman’s voice is the same as the one at the opening of the film. She now speaks about her husband, Roy, and affirms the idea that he is losing his memory. She relates how he would write notes to remember things and leave them across Sealand. “He said he was proud to be English” we learn, and the voice continues “but then he would say how he wouldn’t let the Brits come and take us over./Other days he would talk about defending the empire./As he lost memory he felt that he was surrounded.” (HAVEN 20:00-21:00).

And so I am reminded through this voiceover that the issue is not just one of territoriality and borders, of defence and immunity, but indeed of the empire itself, not only in its geographical and colonial inflections, but in terms of data and information as well. Or, again, the memory of empire starts to infect the data haven retroactively, eating it from the inside out, where immunity spills over into autoimmunity and territory appears no longer external to the data haven but internal to the workings of Sealand itself. Territorial rule, international law, and privacy infringements are never foreign to the data haven and the territoriality of the Internet – even in its most de-territorialized moments, or at those nodes where the language of un- or deregulation is most insistent – also inhabits the data haven (Figure 4).

Memory of empire is adjacent to talk of security and it is between those two figures, the figure of empire and the figure of security, that immunity oscillates. How to belong and remain immune to the law of the land, or in HAVEN’s rendition: how to belong and secure immunity to the grammar of the Internet?.

![Figure 4

“Static on all three screens as shown in an exhibition space in Lisbon, Portugal.” Credits: “James Newitt, HAVEN, exhibition view at Galeria da Boavista, Lisbon, 2023. Photo: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the artist and Galerias Municipais de Lisboa/EGEAC.”]](/document/doi/10.1515/culture-2022-0202/asset/graphic/j_culture-2022-0202_fig_004.jpg)

“Static on all three screens as shown in an exhibition space in Lisbon, Portugal.” Credits: “James Newitt, HAVEN, exhibition view at Galeria da Boavista, Lisbon, 2023. Photo: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the artist and Galerias Municipais de Lisboa/EGEAC.”]

But this is not the first time that the issue of memory is raised in relation to the data haven. Just moments before, HAVEN presented its audience with a digital rendition of the inside of the two pillars on which the platform is structured. Three similar depictions of white static, noise again, are shown after which all three screens turn to grey, and the middle screen shows a text editor in which someone is addressing an email to a certain Ryan. Lines are being added and deleted, the address is directed at one of the cypherpunks, and at some point, the following appears on screen:

I wanted to ask you about the data haven./And if you think the sea is the safest place to keep information?/I imagine that you might also have a fear of forgetting./And that the data haven could have been a place to save memory. (HAVEN 07:07).

The email ends with the line “I’m trying to find a voice for you” which is then deleted, and replaced with the more formulaic “I hope to hear back from you./J.” (HAVEN 07:56). The “J.” presumably signifies the signing of James Newitt, the maker of HAVEN, and as such complicates the relationship between the work, the artist, and the viewer. The artist inscribes a biographical note into the work at the very moment that he purportedly asks Ryan, one of the instigators of the data haven, to reveal himself. It is through addressing Ryan who remains absent for the moment, apparently in need of a voice which he does not receive, that the author of HAVEN writes himself into his work. And it is as a result of this rhetorical address known as an apostrophe that the audience of HAVEN feels at once excluded from the conversation and invited to imagine a voice for Ryan with J., the author who now presents himself as present to a degree to which Ryan will not present himself for the moment. A form of security is at stake not only in the content of this writing on screen, but in the form it takes as well. A safe place is referred to in relation to data, but the very reference produces that of which it speaks performatively, be it elsewhere. If the data haven is supposed to securely store information, the apostrophe produces a conversational structure immune to the interruption of the third, the onlooker, the parasite, and the audience of HAVEN. The safety of the apostrophe and the safety of the data haven appear together as if to say that security exists by means of immunization.

4 Security and Inoculation

HAVEN is immune, HAVEN is secure. We cannot enter into its discourse, it is impenetrable, or better: even penetration does not affect it any longer. In Serres’ words: “The city rat gets used to it, is vaccinated, becomes immune.” (Serres, 2007, p. 14). Its audience remains at a distance, its audio-visual language does not grant entry into the conversation that it sets up, and yet we enter into it. “And yet”: immunity as exception.

If the last part of this article focussed on the concept of immunity, I now want to move on to the purpose and method of immunizing the data haven against outside meddling. How can this haven be at once safe and connected to the Internet? How can it circulate the data that it has, at the same time, captured, locked away, and trapped? Capture and free circulation may seem opposed at first but in Foucault’s lecture series Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978, they appear as co-constitutive when Foucault outlines a form of power that he calls security.

If sovereign power can be understood as the autocratic power of a king to kill, and disciplinary power is structured on the operative verb of surveillance that individualizes, security departs, instead, from the perspective of the population and the management of circulation (Foucault, 2009, p. 42). It is concerned with flows of data, in the form of statistical analyses and has as one of its newfound instruments what we now know as the normal distribution (Foucault, 2009, p. 62). Where discipline attaches itself to the body and soul of the individual, security is attached to the population as a network through which different types of information flow. Where sovereignty dealt with leprosy through exclusion, and discipline with the plague through quarantine, security deals with the smallpox through inoculation. The rise of variolization becomes the metaphor that Foucault employs to describe this new form of power that seeks to immunize not only individual bodies but entire populations against the outbreak of disease by allowing some disease into the body of healthy individuals (Foucault, 2009, pp. 9–10). Foucault describes the process as follows:

Now what was remarkable with variolization … is that it did not try to prevent smallpox so much as provoke it in inoculated individuals, but under conditions such that nullification of the disease could take place at the same time as this vaccination, which thus did not result in a total and complete disease. (Foucault, 2009, p. 59).

A type of immunization arises with security that does not rely on the absolute negation of disease, or on absolute control, but operates by means of a managed infection that then contributes to the management of the circulation of the disease throughout the population as a whole.

The problem of security shifts attention away from the territory as a whole to towns within that territory and their interrelationships. In terms of the network, one might say that there is a shift in emphasis from the network as bordered off by what is taking place on its borders to the nodes and edges that shape the network itself (Foucault, 2009, p. 64). The data haven in HAVEN remains, of course, just another node within the larger territorial space of the Internet in this sense, even as it tries to escape territorial rule associated with UK governance over that space. And where discipline imposes a norm from the outset, security arrives at a normal distribution first and then attempts to bring the data it seeks to capture in conformity with that distribution (Foucault, 2009, p. 63). In this sense, security is the paradigm that seeks to manage the virtual; to manage that which is not yet actualized; and to govern the future in the present.[14] It is the paradigm of insurance.

How does this relate to HAVEN and the figure of the apostrophe that I referred to above? The email addressed to Ryan by J. quoted earlier receives an unexpected response on screen, this time in the form of subtitles overlaying imagery of the sea and clouds above it. The viewer reads:

Hi James,/yeah, I read your email,/but I’m not sure if I understand what you’re looking for,/and why you are interested in a project that failed,/almost 20 years ago./That’s not me practicing Keno in the video./It’s Sean Hastings./We don’t speak anymore./Sean and I came up with the idea of creating a data haven./We met through a mail-list in the early nineties./It was set-up by people who were concerned about security -/and things that were happening with the emergence of the internet./We were looking for ways to protect information privacy -/and create spaces for unregulated data./We needed a place to build the data haven,/somewhere without law -/or at least very flexible law./[.]/OK… If you think you can take me back there./Then maybe we can find a way to talk. (HAVEN 08:32-10:20).

Here, the images on the screens cut to digital renditions of the sea so lifelike that upon first watching it, one is confused about the nature of the visual material. The camera moves over the CGI footage of the platform and the viewer slowly comes to realize that this footage is computer-made. As the camera pans across the open water and the structure reveals its rusty nature, an anti-aircraft cannon appears on the left-hand screen that slowly moves to the centre. It is pointing at the clouds, as if to protect not only against the military operations during the war but against the clouds themselves, as the viewer is reminded once more of the metaphorical language around data and information storage as something ephemeral and fleeting.

There is a superimposition at work here, a palimpsest of sorts, where the history of a British defence tower against German attacks, the history of pirate radio, and the history of a data haven concerned both with security and deregulation all appear within these digitally rendered animations of a platform now corroded and forlorn. Stuck between the sea and the clouds this structure sits like a ship that no longer moves, a space outside of territory, Foucault’s “placeless place,” immune, on the one hand to its logic, but so thoroughly connected to the concept of territoriality at the same time that in its very security, safety, and lawlessness, it has reintroduced the figure of the border” with a vehemence, recently registered by Achille Mbembe as a “renewed infatuation with borders” in a brief text on computational speed regimes titled “Bodies as Borders,” foreign to international waters elsewhere (Foucault, 1998, p. 185; Mbembe, 2019, p. 5). Foucault writes:

[…] we see the emergence of a completely different problem that is no longer that of fixing and demarcating the territory, but of allowing circulations to take place, of controlling them, sifting the good and the bad, ensuring that things are always in movement, constantly moving around, continually going from one point to another, but in such a way that the inherent dangers of this circulation are canceled out. No longer the safety (s û reté) of the Prince and his territory, but the security (sécurité) of the population and, consequently, of those who govern it. (Foucault, 2009, p. 64).

The logic in HAVEN is that of circulation and its management. Even if the language is that of security, interruption, and destruction of hardware, the intent is unobstructed dispersal, movement, and flow. The data haven is imagined from the start as a kind of vault that at once protects its contents against unwanted entry and allows them to circulate more freely than before. A kind of measured circulation that seeks to immunize the data contained there against the normative framework of a law that threatens its circulation from outside. And in the email conversation above, it is made clear that what is at stake is a form of security through deregulation or a form of deregulation through management. The relationship between the data haven as a safe place and the Internet is like the relationship between Rome and those immune to its rule. The Internet contains a data haven that also contains it. Inoculation against regulation through the introduction of a logic of security and capture.

5 Capture and Auto-Immunity

If security is one of Foucault’s words to describe what comes after discipline and surveillance, Philip E. Agre uses the word capture to speak about this new modality of power which uses linguistic metaphors as opposed to visual ones and operates through what he calls grammars of action. Agre highlights the way in which the model of capture as opposed to that of surveillance seeks to grasp structural phenomena at the level of relationships between data points without itself coinciding with those points of data. In other words: where surveillance is obsessed with visualizing the individual node, capture looks at a given structure at the level of a representational scheme that manages circulation within a system. In 1994, around the time of the conception of the data haven in HAVEN, Agre writes about these representational schemes as grammars of action with the following example:

A limited-access highway (such as the roads in the American interstate highway system) enforces, through both physical and legal means, a simple grammar of action whose elements are entrances, discrete continuous segments of traveled roadway, and exits. Toll-collection systems for such roads often employ a keypunch card which contains a table for mapping “grammatical” trips to collectible tolls. (Agre, 2003, p. 746).

And so we are back in the realm of topography. The data haven, understood from the perspective of capture, is not so much an extra-territorial space that either escapes or falls within the realm of territorial surveillance, but can be understood as one grammatical unit that is part of a grammar of action to which other segments of the infrastructure of the Internet also belong.

Seen from this perspective, it makes sense to suggest that the data haven operates not as a deregulated safe place in which data privacy can be protected, but as an immune part of the infrastructure which can nonetheless be described as one grammatical component within a larger linguistic edifice. A different way of phrasing this ambiguous status of the data haven is to say that though its founders speak the language of surveillance still, their project is already caught up in a model of security and capture. A model that seeks to manage the future in the present, as Frederik Tygstrup usefully reminds us with reference to the specific financialized form of insurance called the derivative, in “Information and the Vicissitudes of Representation” (Tygstrup, 2020, p. 21). Noise, in this framework, takes on a different meaning. Where earlier on noise appeared as data that should not have been given, it now resurfaces as data[15] refusing to be captured. It is here that HAVEN enters into a discussion on the equivalencies between the server and the psyche in relation to the memory, wondering which pieces of data can still be retrieved and which, instead, have become so noisy that they will continue to escape capture.

HAVEN continues where I left off in the last section of this text and after some more CGI footage of the tower at times breaking down into a pixelated version of the structure, the attempt at communication between James and Ryan picks up again:

Ryan,/Did you write yourself into the software?/Are you still there?/What happened with the cold data left behind?/Does it still exist if no one can access it, or interpret it?/Still waiting for your reply. (HAVEN 23:45).

In response, Ryan’s voiceover reappears speaking about a dream. There is static; crackling noises as if the recording is not coming through. As if something is captured insufficiently, escaping the model, grammatically incoherent. The dream that we are being told about takes place in the tower, and there is talk of information being inside the speaker. A shift from server to psyche where two iterations of memory are being substituted for one another. A dreamscape in which the information stored in the data haven is incorporated by Ryan’s psyche, nevertheless remaining distinct from it. Incorporation[16] of the outside, inside the subject who does the speaking thus deciphering and encrypting the data anew in the language of the unconscious gestured to in the form of a dream. The black box[17] of the data haven and the black box of the unconscious start to stand-in for one another, thus shifting attention from the informational to the psychic and reversing the logic of neural network metaphors that we have grown accustomed to in the age of deep learning algorithms that are said to mimic the operations of networks of neurons in the human brain.

The imagery shows black-and-white abstract visuals of networks that seem to be biological in nature and I am reminded of the biomedical resonances of immunity. Water is flowing in, entering through holes in the side of the structure, and flooding the structure itself, evidence of which is provided by the flooding of the camera lens. Voices appear in the background, but the noise is so bad that not a word can be distinguished. Where the tower first appeared as a metaphorical replacement for a ship at sea, or a safe haven providing shelter, HAVEN now moves to show a wreck at the bottom of the sea. The tower as a ship appears no longer immune to its surroundings, but drowned by the very surroundings on which immunity relied. Immunity becomes auto-immunity: no longer safely tucked away off the coast and apart from UK regulation, but drowned in the very water that was meant to keep it safe in the first place. The data haven has become a vault that, in order to protect its contents, destroys them. Derrida writes in a text on religion and technology titled “Faith and Knowledge”:

It conducts a terrible war against that which protects it only by threatening it, according to this double and contradictory structure: the immunitary and the auto-immunitary. … But the auto-immunitary haunts the community and its system of immunitary survival like the hyperbole of its own possibility. Nothing in common, nothing immune, safe and sound, heilig and holy, nothing unscathed in the most autonomous living present without a risk of autoimmunity. (Derrida, 2002, p. 82)

Nothing is immune without the risk of autoimmunity. If the Internet is understood as a network of nodes, a community that engenders communication, the data haven, in its attempt to immunize this community against regulation, turns autoimmune in the final moments of HAVEN. It is not a place of neutrality or safety, it is not a free-floating ship roaming the open waters of the Internet; it is always already moored to a specific grammar of action. And if the data haven ever produces any noise, that noise is autoimmune too. As soon as one tries to capture it, it escapes, it ceases to be noise and becomes a message instead. Where noise becomes the message, immunity becomes autoimmunity.

HAVEN closes by shifting the audience’s focus away from the data haven and on to a more contemporary instance of data being stored in open waters. After we see fish swimming next to a cylindrically shaped object at the bottom of the sea, the following words appear:

The sea continues to be exploited as a site for data storage,/as the cloud migrates offshore./Microsoft’s ‘Project Natick’ aims to move their cloud services underwater./In 2019 they tested a second generation prototype./A ‘lights out’ data centre that was sealed shut, filled with pure nitrogen/and sunk to the bottom of the North Sea for two years./Underwater data centres are designed to operate alone./The optimized atmosphere is not meant for human bodies./Kept out of sight./Processing memories we don’t yet have. (HAVEN 32:15-33:15).

And it is with this message that Newitt’s work leaves us. We are reminded for one final time, that safe places appear in different shapes and forms, and that safety on the Internet can mean both the attempts at immunization from territorial rule by Ryan and his fellow cypherpunks, or the immunization largely achieved today by companies like Microsoft, Facebook, and Google from legislative attempts to regulate their activities. This has important implications for how we think about the concept of safe places more generally. What HAVEN suggests is that safety through immunity always risks becoming autoimmune and that attempts to escape regulation are nevertheless structured according to highly specific grammars of action. With its final statements, HAVEN shows that the noise generated by pirate radio stations and cypherpunks on an anti-aircraft defence tower consolidates in the metaphorical dreams of expansion, empire, and colonialism taking place below the surface of that same North Sea. And though Microsoft’s website claims: “Natick is a codename and carries no special meaning. It is a town in Massachusetts” it remains worthy of note that the name Natick is commonly believed to derive from a Native American language and that it means: place of hills (Project Natick Phase 2, n.d.). The cloud has moved to the hills and is stored at the bottom of the sea. Whatever the case may be: a history of aerial defence, immunity to regulation, and aesthetic parasitism has sunk our metaphorical ship; the data haven no longer sails. And as Foucault once remarked in that most enigmatic of texts on space: “In civilizations without ships the dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police that of the corsairs.” (Foucault, 1998, p. 185). The safe place of the data haven has re-appeared in the form of a Microsoft server at the bottom of the North Sea, “kept out of sight, processing memories we don’t yet have” (HAVEN 33:13-33:15).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Janna Houwen for reading earlier drafts of this article, as well as the students at the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Analysis and University College Dublin for discussing the theoretical concerns central to this text with me. I would also like to thank James Newitt for providing unrestricted access to his work and for taking the time to discuss HAVEN at length. Finally, I wish to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who have been generous in their feedback and critique of this text.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Abraham, N., & Torok, M. (2008). The Wolf Man’s magic word: A cryptonymy. University of Minnesota Press (Original work published 1976).Suche in Google Scholar

Agre, P. E. (2003). Surveillance and capture: Two models of privacy. In N. Wardrip-Fruin & N. Montfort (Eds.), The new media reader. MIT Press (Original work published 1994).Suche in Google Scholar

Alfandary, I., & Nesme, A. (2011). Introduction. In I. Alfandary & A. Nesme (Eds.), Modernism and Unreadability (pp. 9–16). Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée. doi: 10.4000/books.pulm.13580.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, S. F. (2017). Technologies of vision: The war between data and images. The MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/10474.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Brown, N. (2019). Immunitary life: A biopolitics of immunity. Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-137-55247-1Suche in Google Scholar

de Certeau, M. (2002). The practice of everyday life In S. Rendall (Trans.). University of California Press (Original work published 1980).Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, E. (2009). A body worth defending: Immunity, biopolitics, and the apotheosis of the modern body. Durham and London: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780822391111.Suche in Google Scholar

Connor, S. (2009, November 26). Michel Serres: The Hard and the Soft. http://www.stevenconnor.com/hardsoft/hardsoft.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G., Lapoujade, D., & Taormina, M. (2004). Bergson, 1859-1941. In Desert islands and other texts, 1953–1974 (pp. 22–31). Semiotext(e).Suche in Google Scholar

Derrida, J. (1981). The double session. In Dissemination. Athlone Press (Original work published 1970).10.7208/chicago/9780226816340.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Derrida, J. (1990). Force de loi: Le “fondement mystique de l’autorité.” Cardozo Law Review, 11(5–6), 919–1045.Suche in Google Scholar

Derrida, J. (2002). Faith and knowledge: The two sources of “religion” at the limits of reason. In G. Anidjar (Ed.), Acts of religion (pp. 40–101). Routledge (Original work published 1996).Suche in Google Scholar

Derrida, J. (2005). Rogues: Two essays on reason. Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Derrida, J. (2008). Fors: The Anglish words of Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok. In The Wolf Man’s magic word: A cryptonymy (pp. xi–xlviii). University of Minnesota Press (Original work published 1977).Suche in Google Scholar

Drucker, J. (2011). Humanities approaches to graphical display. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 5(1). https://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq0/vol/5/1/000091/000091.html#.Suche in Google Scholar

Esposito, R. (2006). The immunization paradigm. In T. Campbell (Trans.). Diacritics, 36(2), 23–48.10.1353/dia.2008.0015Suche in Google Scholar

Foucault, M. (1998). Different spaces. In J. D. Faubion (Ed.), Aesthetics, method, and epistemology, Essential works of Foucault 1954–1984, Vol. 2 (Vol. 2, pp. 175–185). New Press (Original work published 1967).Suche in Google Scholar

Foucault, M. (2009). Security, territory, population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978. In G. Burchell (Trans.). Picador (Original work published 2004).Suche in Google Scholar

Galloway, A. R., & Thacker, E. (2007). The exploit: A theory of networks. University of Minnesota Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hobbs, H., & Williams, G. (2021). The demise of the ‘second largest country in Australia’: Micronations and Australian exceptionalism. Australian Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 206–223. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2021.1935450.Suche in Google Scholar

Larkin, B. (2013). The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.Suche in Google Scholar

Luhmann, N. (2004). Einführung in die Systemtheorie. Carl-Auer-Systeme Verlag (Original work published 1993).Suche in Google Scholar

Manovich, L. (1999). Database as symbolic form. Convergence, 5(2), 80–99. doi: 10.1177/135485659900500206.Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, N. (2019). Breath on the windowpane: Precarious aesthetics and diegetic noise in Nick Broomfield’s Ghosts. Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture, 10(2), 243–259.10.1386/cjmc_00005_1Suche in Google Scholar

Mbembe, A. (2019). Bodies as borders. From the European South a Transdisciplinary Journal of Postcolonial Humanities, 4, 5–18.Suche in Google Scholar

Newitt, J. (Director). (2023). HAVEN [Video Art].Suche in Google Scholar

Ofcom. (2023, May 17). Ofcom.Org.Uk. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/about-ofcom.Suche in Google Scholar

Parisi, L. (2007). Biotech: Life by contagion. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(6), 29–52. doi: 10.1177/0263276407078711.Suche in Google Scholar

Parisi, L. (2022). Contagious architecture: Computation, aesthetics, and space. MIT press.Suche in Google Scholar

Project Natick Phase 2. (n.d.). Microsoft.Com. Retrieved June 2, 2023, from https://natick.research.microsoft.com/#section-faq.Suche in Google Scholar

Serres, M. (2007). The Parasite In L. R. Schehr (Trans.). University of Minnesota Press (Original work published 1980).Suche in Google Scholar

Tuan, Y. (2002). Space and place: The perspective of experience. University of Minnesota press (Original work published 1977).Suche in Google Scholar

Tygstrup, F. (2020). Information and the Vicissitudes of Representation. Diffractions, 6(1),13–23. doi: 10.34632/DIFFRACTIONS.2020.8389.Suche in Google Scholar

Van der Velden, D., & Kruk, V. (2012). Captives of the Cloud: Part 1. E-Flux Journal, 37. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/37/61232/captives-of-the-cloud-part-i/.Suche in Google Scholar

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Principality of Sealand. Principality of Sealand. Retrieved August 9, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principality_of_Sealand.Suche in Google Scholar

Wolfe, C. (2007). Introduction to the New Edition: Bring the Noise: The Parasite and the Multiple Genealogies of Posthumanism. In L. R. Schehr (Trans.), The parasite (pp. xi–xxviii). University of Minnesota Press (Original work published 1980).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective