Abstract

To understand a text, or any other form of art work, as referring to a disease is not always obvious. This uncertainty, although confined to rare cases, nevertheless allows us to explore the limits and blind spots of certain frameworks proposed to think about the relationship between art and disease, notably Susan Sontag’s book Ilness as metaphor. In this article, I take a closer look at the calamity described in chapters 5 and 6 of the first book of Samuel and its various exegeses in the Western World. This calamity (still considered by many to be a bubonic plague), was not associated with the pandemic imaginary by ancient commentators, artists, and doctors, and it is only in modern times that medical diagnoses of the text change in this sense. I propose to see that these seemingly innocuous changes in diagnostic interpretations actually reflect deep changes in the relation between illness and divine agency. After a brief critical review of Susan Sontag’s writings on interpretation and their relationship to Ilness as Metaphor, I will proceed to trace the complex interpretation history of this calamity, before drawing observations about the place of interpretation in literary criticism and in the medical sciences.

1 Introduction

To understand a text, or any other form of art work, as referring to a disease is not always obvious. This uncertainty, although confined to rare cases, nevertheless allows us to explore the limits and blind spots of certain frameworks proposed to think about the relationship between art and disease, notably, Susan Sontag’s book Ilness as Metaphor. In this article, I take a closer look at chapters 5 and 6 of the first book of Samuel and its various exegeses in the Western World. As part of a larger story about the rivalry between the Philistines and Israel and the advent of Saul’s and then David’s kingship, this biblical passage narrates a strange calamity that is said to have struck the Philistine populations after they took the Ark of the Covenant following their victory in the second battle taking place between Eben-Ezer and Aphek. This calamity (still considered by many to be a bubonic plague), taking the form of an invasion of rodents associated with the appearance of mysterious growths on the bodies of the Philistines and a general panic, was not associated with the epidemic imaginary by ancient exegetes, painters, and medical experts. It is only in modern times that medical diagnoses of the text change in this sense, and that an epidemic or contagious (both terms are used as quasi-synonyms in the context of this article) reading of the text arose. I propose to see that these seemingly innocuous changes in diagnostic interpretations actually reflect deep changes in the relation between illness and divine agency.

After a brief critical review of Susan Sontag’s writings on interpretation and their relationship to Ilness as Metaphor, I will proceed to an introduction to chapters 5 and 6 of 1 Samuel and trace the complex history of their interpretation, before drawing observations about the place of interpretation in literary criticism and in the medical sciences.

2 On Transparency

Before jumping directly into the text that is the subject of this article, I think it is relevant to look at Sontag’s thinking about interpretation, both because Ilness as Metaphor is a direct extension of it and because this article deals specifically with interpretive texts.

At first glance, turning to Sontag to critique her work may seem anachronistic. Most of her essays were written between the 1960s and 1980s, and other more recent authors could be taken as a reflexive starting point. However, this would overlook the great return to the reading of Sontag’s essays that took place after the onset of the COVID 19 pandemic. A large number of authors (Aykutalp & Karakurt, 2020; Campo, 2023; Craig, 2020; Clark & Altin, 2022; Gao, 2022; Garzone, 2021; Krug, 2021; Kazemian et al., 2022; Sreekala, 2022; Saji et al., 2021; Semino, 2021) read, or re-read, Sontag in the context of the pandemic, using Ilness as Metaphor and Aids as Metaphor as framework for understanding Covid 19, but also other diseases evoked in its wake, such as the bubonic plague (Boucheron, Anno 1349). This return to the use of Sontag’s conceptual tools has also led others to a critical re-examination of these same tools (Fulk), an approach taken by this article.

Before publishing Ilness as Metaphor in 1978, Susan Sontag had already published several other works, including an article entitled Against Interpretation (1966). In the latter, she explains how interpretation, as a hegemonic relationship to the work of art, perpetuates what she considers an outdated and irrelevant distinction between content and form. By that, she targets specifically “a conscious act of the mind which illustrates a certain code, certain ‘rules’ of interpretation” (p. 15), which would distort the original work by turning it in something else. In this text, she strongly criticizes Philo of Alexandria, but more broadly the “Rabinic and Christian spiritual interpretations,” which, according to her, under the guise of delivering the substance of a text, only alter it. Among the interpreters, however, Sontag distinguishes two categories, the ancient and the modern: “The old style of interpretation was insistent, but respectful; it erected another meaning on top of the literal one. The modem style of interpretation excavates, and as it excavates, destroys; it digs ‘behind’ the text, to find a sub-text which is the true one” (p. 16). The hypothesis of a rupture of this type between ancient and modern would be difficult to defend today in view of the contemporary understanding of late antique and medieval literature, and it would be also wrong to say that the ancient commentators are building on the firm ground of literal meaning. In reality, they are very often the co-builder, when it is not even the co-editor, with the multiple additions and revisions of the successive copyists (to cite but one eloquent example: Tov, 2004). What Sontag says about the major modern ideologists: “According to Marx and Freud, these events only seem to be intelligible. Actually, they have no meaning without interpretation” (pp. 16–17) could very well be used to describe some of Origen’s theories, which deny the very existence of a literal meaning for certain biblical passages (King, 2005, pp. 38–76). Nevertheless, this distinction sheds light on Susan Sontag’s way of thinking, who seems to think that there is always a substratum, a reality, a literal meaning to which one can always return once the interpretation is discarded.

This idea of a substratum is one of the philosophical premises of a great part of her work, which we see especially appearing through the notion of “transparence/transparency,” one of the discreet leitmotiv of her essays. As early as Against Interpretation, she will say that: “Transparence is the highest, most liberating value in art - and in criticism - today. Transparence means experiencing the luminousness of the thing in itself, of things being what they are” (p. 23). Her interest for transparency is also one of the discreet foundations of Sontag’s interest in photography, because she finds in it, more than in the other arts, this transparency that is so important to her and that brings her closer to the task that she believes should be that of the critic: “While a painting or a prose description can never be other than a narrowly selective interpretation, a photograph can be treated as a narrowly selective transparency” (pp. 3–4) – Robert Frank was only being honest when he declared that “to produce an authentic contemporary document, the visual impact should be such as will nullify explanation. If photographs are messages, the message is both transparent and mysterious” (p. 86). Sontag’s discourse on the relation of art to reality is closely linked to her position of strict indistinction between content and form in art, notably expressed in Against Interpretation and in On Style, and this position complexifies greatly the role that plays in this report the notion of transparency that she develops, notably when it is question of nonfigurative art. Nevertheless, Sontag’s point is much clearer when it comes to the role of transparency in the relationship between a reality and its critique: here, transparency is what the “erotics of arts” she promotes tends towards and is the antithesis of the opacity towards which hermeneutics tends towards, without admitting it.

This strong relationship to reality manifested by Sontag’s interest in transparency is decisive for understanding the underlying logic of Ilness as Metaphor. For Sontag, the disease exists, it is a concrete and indubitable reality. The two main illnesses she presents, tuberculosis and cancer (which she was experiencing during the book writing and are discussed in Sontag, AIDS…), are two entities whose existence is unanimously recognized and with a quite consensual clinical picture. The historical and contextual variations she describes relate to causes and remedies, but not to the very existence of the illness. Thus, there is a reality, for example cancer, which is coated with a layer of metaphor that alters its flavour, but which is not necessary for its existence: as she presents it in the conclusion of her book, cancer will outlive its metaphors. The project of Illness as Metaphor, which is outlined in the introduction to her other book Aids and its Metaphor, is indeed to be critical of the interpretive system, in order to bring transparency and increase the luminescence captured from the reality of illness, which is somehow, to use an important word in Sontag’s vocabulary, a “mysterious” thing, to be experienced and explored beyond, or actually below, the phagocytizing interpretation, in a “radical contemplative” manner (Fulk, 2021).

Thus, we can say that Sontag maintains a positivist relationship to the disease, in that it has a reality that can be reached by science: the clinical picture is an expression of reality. However, even before Ilness as Metaphor was written, this model was already being challenged by the physician and literary critic Starobinski, who in his 1972 article Le démoniaque de Gérasa: analyse littéraire de Marc 5. 1-20 (translated in English the following year under the name: The Struggle with Legion: A Literary Analysis of Mark 5: 1-20) already emphasized the extent to which the diagnosis of a disease is an essentially hermeneutic act, the physician being the interpreter, in the strongest sense of the term, of the symptoms:

However acceptable the idea might seem that a series of facts, of givens, would precede, in virtue of being the first stratum, the interpretation subsequently given to them […] one cannot help suspecting that the opposite is also[1] admissible […] Therefore, it is no longer the morbid symptoms which are primary but the ‘cultural’ concept. (Starobinski, 1973).

Starobinski will introduce in this same article the notion of sociogenesis, or logogenesis of the symptom, in total mismatch with the positivist idea of the discovery or identification of the symptom, which Sontag tacitly adopts. Here, in agreement with Sontag, but going one step further, Starobinski recalls that:

Every interpretation which believes itself to be adequate claims for itself conformity to ‘the nature of things’. It prefers not to conceive of itself as an interpretation but as a statement of what in truth occurs, while reserving, with a pejorative nuance, the term ‘interpretation’ for all the preceding readings of the same given, readings which seem to it tainted by illusion, encumbered with imaginary projections, deformed by the prejudices of the interpreter. (Starobinski, 1973).

Sontag’s “stop block” is sent back by Starobinski to the world of interpretation: by wanting, in Ilness as Metaphor, to blow up the interpretative system of illness, she is in fact militating for the hegemony of her interpretative model, that of positivist medicine.

Starobinski developed these reflections in the context of an exegesis of the biblical text of Mark 5:1-20. The Bible is in fact, because of its long history of interpretation, a propitious ground for the establishment of fundamental epistemological reflections on hermeneutics, even if those on medical hermeneutics have been more marginal. However, the medical interpretations of certain texts, such as Mark 5:1-20, which have been proposed throughout the centuries, and which have greatly multiplied since the nineteenth century, are elements of choice for building a reflection on this subject: The fact that here, medical diagnoses are being proposed for texts, and not humans, provides a fertile, liminal ground that helps us to better understand what medical interpretation is and the troubling proximity it bears with literary interpretation.

In the following sections, I propose, following Jean Starobinski, to begin an excursion through a biblical text dealing with a physical illness and its reception to be able to feed the reflection on the articulation between medicine and interpretation. 1 Samuel 5-6 and its successive interpretations, more precisely in the passages relating to the so-called “plague” of Ashdod, allow me to show, in the prolongation of Starobinski (and also more recent anthropologist of the medical world, such as Laplantine (1992) or Fassin (2014, 2021)), to what extent translation, reading, rereading, interpretation, and diagnosis are words that are almost always interchangeable, and to what extent the diagnoses proposed for the illnesses presented in the text can also have, just like the allegorical readings, their underlying theology and imaginary too.

3 The Biblical Narrative

In 1942, Otto Neustätter published “Where did the identification of the Philistine plague (1* Samuel, 5 and 6) as bubonic plague originate?”, a landmark article, which is still used today as a reference by biblical exegetes (such as Walter Dietrich (2011) and Christophe Nihan (2022)). In this text, Neustätter notes the popularity of the plague hypothesis among some exegetes and physicians to explain the “ophelims” of 1 Sm 5-6 and places the origin of this hypothesis with the Swiss physician Jacob Scheuchzer in his work Physica Sacra published in 1725. Neustätter is to be lauded for his effort to do intellectual history in biblical exegesis, a field of study still little explored today. Nevertheless, there is a blind spot in Neustätter’s approach: while his article aims to give critical depth to the bubonic plague reading of the biblical passage, the author completely neglects to give an historiography of the epidemiological reading paradigm in which he evolves, of which bubonic plague reading is but a sub-category (as will be shown in later sections).

Indeed, Neustätter assumes that the Bible describes a “fierce, contagious sickness with quick and high mortality […]. One city after another to which the ark was taken showed an outbreak of the disease; death and excruciating pain befell the people, and the cry of the cities went up to heaven” (1942). Nevertheless, the idea of a “contagious sickness” is anything but obvious in the biblical text and in its reception, and appears to be a reading in a modern epidemiological paradigm of the narrative of 1 Samuel 5-6. Thus, the hypotheses maintaining that the Bible speaks here of a bubonic plague could only flourish within a hermeneutical paradigmatic framework of which Neustätter was still a part in the 1940s: that of an epidemiological reading of the disease of the Philistines, grouping together several families of hypotheses and forming part of the long history of the interpretation of 1 Sm 5-6, which should be retraced to understand its dynamics.

The basis of the whole affair, the narrative of chapters 5 and 6 of 1 Samuel, is as follows: Following a victory over Israel in a battle taking place between Eben-Ezer and Aphek, the Philistines seize the Ark of the Covenant a mysterious box-like religious artefact whose cultic and martial functions are not entirely clear to the exegetes (Porzig, 2009; Römer, 2020), which had been taken to the scene of the battle by the people of Israel. The Philistines brought the Ark back with them to Ashdod, one of their cities, and placed it in their temple to Dagon, their God. But God will cause several disturbances among the Philistines, who, after many months of suffering and consultation with their leaders, will return, with offerings in the form of gold mice and gold haemorrhoids, the Ark to Beit Shemesh where it will be recovered by Israel.

The description of the disturbances suffered by the Philistines is complex. We can distinguish four different ones: The first is the miraculous destruction of the statue of Dagon, recounted in great detail in 1 Sm 5:2-5, the second, often overlooked because wrongly perceived by many as a simple consequence of other disturbances, is a “deadly panic” (מהומת־מות) which struck the inhabitants of Gath in 1 Sm 5:9, then Eqron (Askalon in the Septuagint) in 1 Sm 5:11.

The following disturbance, mentioned in 1 Sm 5:6 and 1 Sm 5:12, is simply mentioned as follows: “הכו בעפלים”, literally: “he [YHWH] struck them from/by/in/on the ophelim.” These ophelims are at the origin, in the history of interpretation, of all medical speculations on the text. The meaning of these ophelim, and the more general nature of the divine scourge, has puzzled ancient exegetes and modern scholars alike. The term is almost an apax: it is only mentioned in one other place in the Bible, in Deuteronomy 28:27, which presents a context that refers to a form of God-sent disease, but without further clarification. In 1 Sm 6:11 and 17, the offering proposed in connection with the scourge of the ophelim are images of “טְחֹרִים“ (tehorim), which translates unambiguously as haemorrhoids,[2] which does not give as much context as one might think at first sight: Is the link with the abdomen, the anus, the shape of the ophelim, the digestive system, the visual or symbolic similarity of the two things? The link is well attested, but its nature and the reasoning behind it remain opaque to us. Contemporary exegetes and historical-critical philologists agree that, from a philological point of view, “swelling” seems to be the most accurate and least biased translation[3] of ophelim (Hunziker-Rodewald, 2021; Seppänen, 2018). The ancient interpreters of the text, and after them a good part of the modern researchers, tend to confuse this disturbance with the previous one, but as Regine Hunziker-Rodewald points out: “The ‘swellings’ are not lethal, they are an alternative to death. […] The ‘deadly panic’ in Eqron (מהומת־מות, 1 Sm 5:11b), initiated by YHWH, is lethal (v. 12aα, cf. Dt 7:23 and Is 22:5; Ez 7:7, Zec 14:13) but not the ‘swellings’.” As mentioned earlier, neither the text nor the term ophelim in itself evokes the idea of an epidemic, although, by habit more than by analytical conclusion, the critics still describes it as such, starting with Lawrence Conrad (1984), who was nevertheless a pioneer in his refusal to identify it with any disease recognized by today’s science.

The last disturbance is that of the mice, which God sends to invade the fields of the Philistines. The presence of this scourge in the original text of 1 Sm 5-6 is not certain. The Hebrew text does not mention that God sends this scourge upon the Philistines, but the Philistines nevertheless send offerings in the form of golden mice, in connection with a mice attack mentioned in 1 Sm 6:5. The Septuagint has a longer and more coherent text, where the mice are indeed one of the scourges sent in 1 Sm 5:6. On this well-known problem of textual criticism, identified by Bodner (2008), two main schools are in opposition: a French school, mainly inspired by the ‘Bible d’Alexandrie’ project started in 1986 by Marguerite Harl, is represented in the exegesis of this text by Nihan. Based on the approach of Angelini, Nihan sees the translators of the Septuagint as seeking above all to adapt the biblical text to the intellectual context in which they live, not refraining from amplifying, reducing, or altering the text; and a Finnish school, represented by Aejmelaeus and Tuukka (2017), Kauhannen (2012) and Seppänen (2018), which rather present the translators of the Septuagint as fairly faithful transmitters of the available Hebrew text of their time. The key question, often marking the divide between these two schools, is whether the Greek text presents a late literary addition (French school), or translates a tradition that may be older than that of the Hebrew Massoretic text (Finnish school; Aejmelaeus, 2008; Pakkala, 2013). Nihan proposes to see the scourge of mice as a later Hellenistic creation, while Seppänen proposes a model in which the original Septuagint source text, known as the ‘Vorlage’ (a German term), and the Masoretic Text reflect two editorial iterations that merged two narratives. One narrative speaks of a scourge of mice, while the other speaks of a scourge of ophelim. In several respects, the Septuagint Vorlage appears to preserve a more ancient version of the text than the Masoretic Hebrew. If Seppänen presents a series of very convincing philological arguments to show that the Masoretic text is not the oldest, the impossibility of reconstructing the two original narrative scourges still leaves us with a lot of unknowns as to the origin and meaning of 1 Sam 5-6, two of the four scourges mentioned posing major philological problems and the coherence of the scourges not being obvious.

If the philological reconstruction of the Hebrew original of the passage, as well as the interpretation of its general meaning, represents for contemporary research, a real crux, the first interpreters, that is to say the translators of the Septuagint, the Masoretes, and the Latin translators (of which Jerome), sought, each in the context of their textual tradition, nevertheless to give meaning to the text and to its ophelim. Thus, the Septuagint will decide to make the difference between ophelim and tehorim disappear, translating them both as “ἕδρα,” a translation obviously based on tehorim and designating a rectal problem, generally understood as haemorrhoids. The Massoretes, without touching the text, will propose in the same sense to systematically read as Queré tehorim when ophelim appears, again making the difference between the two terms disappear. The Vulgate will nevertheless try to render the distinction of terms found in the Hebrew, with the influence of the Septuagint. Ophelim is rendered as “in secretiori parte” and tehorim as “anus.” However, it accentuates the diagnosis of the Septuagint, by speaking of “their protruding rectums were rotting”[4] in v.9, and by glossing “and they crafted themselves fur-covered seats,”[5] confirming the hemorrhoidal rereading of the narrative.

4 To Diagnose a Miracle

The Septuagint, if it anchored the haemorrhoids as the classical and for a long-time favourite interpretation of the ophelim, was nevertheless not unanimous, and ancient authors sought, at least from the first century AD, to understand to which disease the text referred. Flavius Josephus is the first to reread the text, focusing on the disease, which he presents as dysentery, which becomes the cause of the death of the Philistines:

And lastly, a divine punishment and disease overcame the city of the Philistines and their land. For they were dying from dysentery, a severe affliction, and the most deadly destruction, inflicting them before their souls could be separated from their bodies. They expelled the things inside, vomiting out things corroded and destroyed in various ways by the disease. Moreover, a multitude of mice emerged in the country, laying waste to both plants and fruits.[6]

Flavius Josephus proceeds to a rereading of the text cantered on the disease, which becomes the cause of the death of the Philistines. It is noteworthy that in some Latin manuscripts (as in Bamberg Msc. Class. 78), the role of mice is overshadowed, and it is the human crowds that pounce on the plants and fruits. Flavius Josephus thus aggravates the account of the Septuagint: the haemorrhoids turn into deadly dysentery. Flavius nevertheless holds a different view in the De Bellum Judaicum (V, 385), showing that it is not systematic on the interpretation of this disease (Kottek, 1994, pp. 39–40). In the following century, Aquila and Symmachus, two translators of the Bible from Hebrew into Greek, each proposed an original translation of the tehorim, the first translating “φαγἐδαινα,” a cancerous tumour, and the second “κατὰ τῶν κρυπτῶν,” an expression which itself is not very clear, but which was understood by its early modern readers as referring to some form of organ descent. A contemporary, the Pseudo-Philon, also proposes a rereading of the passage, but gives coherence to the biblical text by eliminating the plague of the ophelim and by transforming the account into a massive and deadly attack of mice and crawling beasts which throw themselves on the cities of the Philistines (2018, p. 55; Jacobson, 2018, pp. 1136–1148), in a way very similar to the accounts of cities devastated by hordes of vermin that are presented in the same period by Pliny the Elder (8 :42–43,82). All these proposals reflect the fact that from the first century of our era, a context of shared ignorance about the meaning of ophelim is already present.

These propositions will form until the seventeenth century the inventory of possible interpretations of the text. If, for their authors, they seem to be mutually exclusive, later readers will have no problem superimposing some of them, just as they superimpose the disturbances mentioned in the story. Thus, long before the diagnosis of modern bubonic plague was proposed by Arnold Netter in 1897, the disease had been associated directly with mice in a variant of the Vetus Latina (the collective name for biblical translations predating the Vulgate) attested by a quote from Lucifer of Cagliari: “and mice bubbled to them in the seats” (De Athanasio, I 12).[7] It is possible that it is this textual variant that is the origin of a tradition about the plagues of the Philistines that is found in medieval Midrashic literature (Ginzberg, 2003, pp. 849–895), where the mice come up from the bottom of the philistines’ toilets in order to jerk their entrails through their anus. At the same time that this reading began to circulate, the correction of the ships[8] to the seats[9] in 1 Sm 5:6 is spotted in some minuscules of the Septuagint (Mss. 56; Mss 247; Aejmelaeus, 2008), modification bringing the biblical text into line with an interpretation popular at the time, in a context where the clear distinction between literal meaning and interpretation, as described by Sontag, did not exist. The Midrashic interpretation, which enjoyed a certain notoriety in the Middle Ages (Ginzberg, 2003, pp. 849–895), will pass quickly in the Christian world, by means of the Historia Scholastica, a biblical paraphrase extremely popular in the Middle Ages:

For this reason, no one entering the temple in Ashdod treads upon the threshold to this day, and the hand of the Lord was heavy upon the people of Ashdod, and He struck them in the hidden parts of their buttocks, and their protruding rectum became putrid. What Josephus says occurred from a cruel affliction of dysentery, so that their intestines rotted, and mice bubbling from the fields gnawed at their protruding rectum. (Historia Scholastica, Libri 1 Regum cap VIII).[10]

Here, the author, Petrus Comestor, confuses the rereading of Flavius Josephe and the aforementioned Midrash, attributing both to the former. Nevertheless, from then on, this link between the disease and the rats will be on the Christian “interpretative market.”

As is the case in the Historia Scolastica, haemorrhoids and dysentery will often be mixed or confused in the medieval reception, in that they refer to the anus and excretions, two things that are very symbolically charged. This was indeed the important point for the exegetes of the time, more concerned with what they defined according to their criteria (variable according to the authors) as the allegorical and ethical meaning of the text. Thus, the Glossa Ordinaria, the collection of authoritative patristic quotations accompanying the bibles from the twelfth to the fourteenth century, presents the Philistines as the allegory of nations receiving the gospel, represented by the Ark of the Covenant. But the latter, going back to their old custom, symbolized by the idolatry of the cult of Dagon, will be struck in their back. The idea of a contagious disease is not present in the exegesis of the time, the Glossa Ordinaria specifying that if the Philistines are all affected by the “plague,” it is because they have all erred:

In order that wherever he [the people] goes, a punishment accompanies him, we understand it to be a plague from God because it was done by the will and plan of God, so that it would be a shared scourge, as the fault was shared. (Glossa Ordinaria, PL113:546).[11]

This exegesis represents, with a few variations (the Ark of the Covenant can be understood as Christ instead of the Gospel), what we find in the ancient and medieval commentaries on 1 Sm 5-6. In the fifteenth century, Denis the Carthusian still present the same reading mixing haemorrhoids and dysentery, aiming at humiliating the Philistines in their idolatrous pride:

But the men of Ashdod, seeing such a scourge which, (according to the commentators unanimously), was a foul and severe dysentery, with a certain corruption and putrefaction of the lower intestines, to the extent that they were teeming with and protruding outward with worms, saw this scourge through experience within themselves, that is, they felt it or even observed it to apply a remedy. It is asked why they were struck by this plague more than any other. It can be answered that it was to humble their blasphemy, presumption, and most vile pride. (Opera omnia, Vol. 3, p. 286).[12]

To come back to the question of contagion, besides the fact that, as the Glossa Ordinaria says, the Philistines are struck by the action of God because of their sin, the diseases diagnosed are not understood at the time as being based on human contagion or zoonosis. Dysentery is a well-known disease of the Antiquity and the Middle Ages, where, according to the sources, it raged especially in the military camps (Lim & Wallace, 2004; Robb et al., 2021). Its “pestilential” character and its link with sanitation problems is also recognized throughout the Middle Ages, but without any thought of contagion through human or animal contact. Vegetius, a very popular author on strategy and medicine throughout the Middle Ages, already poses the problem of military camp epidemics, of which dysentery is a part, in a very pragmatic way: “For bad water, when drunk, similar to poison, generates pestilence in those who drink it” (De Re Militari, Vol 3, Chap 2).[13] In this, he follows the classical observation of Hippocrates, linking dysentery to dirty water and changes in climate (Lim & Wallace, 2004). Gregory of Tours, when he describes the “dysenteric disease”[14] which rages under Chilperic 1st, simply reports that: “However, many asserted that it was a hidden poison” (Historia Francorum, Vol. 5, col. 243). But it should be noted that the ancient and medieval interpreters of 1 Sm 5-6 were not primarily concerned with medical verisimilitude, and sought to emphasize, as the quotations from Flavius Josephus and Dionysius the Carthusian given earlier show, the uncommon and almost, if not completely, supernatural character of this dysentery.

As for the different types of haemorrhoids and fistulas, they never seem to have been perceived as diseases circulating by means of a contagion. Treatises of fistula in ano, haemorrhoids and clysters written in the fourteenth century by the surgeon John of Arderne, as well as the medical literature preceding and following it (Sobrado & Mester, 2020), does not recognize any pestilential or contagious character to these diseases. Also, ancient and medieval readers of 1 Sm 5-6 see, with the Latin of the Vulgate, that the Philistines are stricken with a “plaga,” but not with a “pestilence.”

5 Maybe Modern, but not Maverick

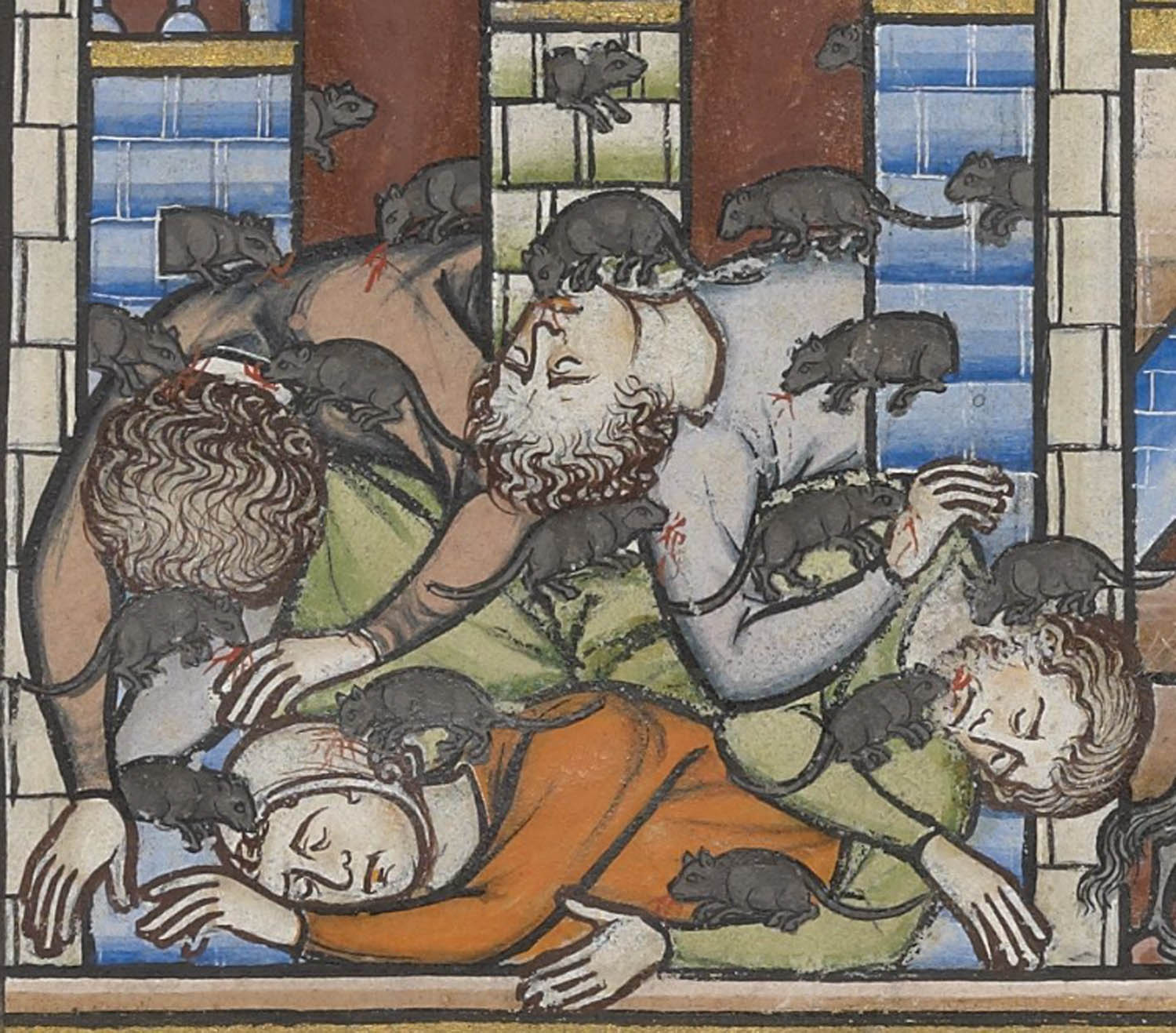

Since Adrien Proust and his treatise on the plague of 1887, a tenacious belief wants that it is Nicolas Poussin, with his painting The Plague of Ashdod (originally named “The Miracle of the Ark in the Temple of Dagon”) who would have initiated in 1630–1631 the link, in the modern West, between the biblical episode and the plague, but also between the plague and the rats. While this assessment has been re-evaluated by Barker (2004) who has shown that in the context of the sixteenth-century medicine, although in terms very different from those of contemporary medicine (Cole, 2010), the rat was seen as a possible etiology of the plague, it remains that an important part of historiography still sees in Poussin the creator of a visual stereotype of a symbolic rather than scientific association (Boucheron, 2021a,b). The sources, both literary and pictorial, of Poussin’s painting have been studied in detail (Boeckl, 1991; Keazor, 1996a,b), but concentrating on the paintings of the masters and strangely neglecting the previous pictorial representations of the biblical episode. Neustatter (1941), and latter Pamela Berger, looked at the medieval and early modern illustrations of 1 Sm 4-6 found in illustrated bibles, to show that already in the thirteenth century, before the Black Death appeared, the people of Europe were aware of the link between the bubonic plague and rats. Nevertheless, as Samuel Cohn (2009) points out in his review of Berger’s article: “the examples she cites of the twelfth- and thirteenth-century depictions of rats in plague gainsay any knowledge of bubonic plague” – observation is also valid for Neustater’s article, who did not wait for contemporary criticism to disavow his analysis in a second publication published only 1 year after the first (1942). This retraction may perhaps explain the lack of research interest in Poussin’s precursors in the representation of 1 Sm 5-6. If Keazor, in his investigation of the sources of the painting, did not consult Neustater, Boeckl, in her pioneering article, offers only these words: “by the thirteenth century there was an established tradition in book illumination for painting the victims of the scourge together with the rats.” It is nevertheless herself who puts us on the track of a reconsideration of these precursor illustrations, when she says, elsewhere in her article she mentions the: “resurgence of archaic iconography after the Council of Trent in 1545-63,” thus pointing to the importance of understanding medieval motifs for the analysis of Poussin’s painting. From the “established tradition,” we have in reality only two known witnesses, dissimilar between them and separated by more than two centuries. The first, the Crusader Bible (Figure 1) is the one that has attracted the most attention. It dates from the middle of the thirteenth century and depicts a city in which there is a pile of human bodies with no obvious signs of disease or tumour, covered with rats lacerating them from all sides.

“The Plague at Ashdod,” detail, illuminated manuscript, c. 1250, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, MS 638, folio 21 verso.

The second witness is an illustration of the Lübeck Master (Figure 2), present in the Lübeck Bible of 1494, an edition of the Bible in Low German. This one presents a very different situation, where living, dying, and dead people are represented outside. Two of the characters on the ground put their hand on their buttocks. The mice do not interact with the men, except for one that leans on the buttocks of one of the two aforementioned people, its snout turned in the general direction of its anus. These two images do illustrate the story of 1 Sm 5, and in this, they belong to a wider common tradition extending from the Middle Ages, of which many examples can be found in Neustatter (1941), and Pamela Berger. In addition to the temporal gap of more than two centuries between these two representations, the substantive difference in the treatment of the subject shows that these two images do not form, or are not part of, a common representational sub-tradition. On the contrary, they illustrate quite different exegetical traditions of 1 Sm 5. The image of the Crusader Bible represents a reading of the biblical text hermeneutically quite close to that of the Pseudo-Philon, where it is the swarms of pests that create death among the Philistines. The bloody lacerations made by the rats in the image indicate that they physically attack humans via their bites. The image contains no reference to tumours or any form of disease, and in another part of the same image, the Ark is seen being sent back to Bet Shemesh with three rats on golden pedestals - the ancient illustrations do not depict the golden tumours (1941). In her recent study on medieval images of the plague, Barker (2021) deals at length with this image, but she starts from the principle that the biblical text, as well as all its reception, includes in an obvious way the description of a “Philistines’ epidemic” (2021), which, in view of the elements mobilized so far, remains to be demonstrated. The description of the rats given by Barker in 2021 (‘The dead piled high in the streets outside where they are eaten by the rats that correspond to the plague of rats mentioned in the Septuagint’) is inadequate, for the Septuagint presents mice only as crop pests: only within the hermeneutical framework of the Pseudo-Philon is an attack, as represented in the image, depicted. Commenting again on this image, Barker says: “an important conceptual shift has occurred: in the European medieval imaginary, the understanding of a plague sent by God now incorporates the secular and material explanation of epidemic disease as a corruption of the air in a particular place” (2021). Nevertheless, the biblical commentators of the time, as well as those who preceded and those who will follow, will not evoke explanations related to air and miasmas: the ordinary medical explanation found in commentaries concerned with a reading of this type speaks either of haemorrhoids, simply following the Vulgate, or of dysentery for those following Flavius Josephus, whose conception did not really change between antiquity and the Middle Ages. It seems to me impossible to follow Barker when she says, on the basis of this image alone, that: “we find further evidence that educated elites in thirteenth-century France were beginning to regard the Biblical plagues as analogous to the pestilential epidemics with natural causes” (2021). In this, she takes up and slightly adapts the model established by Proust, then followed by Meige (1897), Neustater and Berger, consisting in seeing in the illustrations of 1 Sm 5-6 apaxs of an acute for their time conception of epidemic and plague. This image, as well as medieval exegesis more generally, whether literary or visual, bears no trace of an “epidemic perspective” on 1 Sm 5-6.

“The Plague at Ashdod,” detail, incunabula bible, 1494, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München, Rar. 880, folio 111 verso.

The illustration in the Lübeck Bible reflects different exegetical inspirations. The fact that the figures are depicted in different stages of illness (healthy, dying, dead) and the hand on their buttocks indicates the idea of a gastric or haemorrhoidal problem (or a combination of both), thus following the interpretations available in contemporary biblical commentaries of his time, based mainly on the interpretations included in the Vulgate translation and in Flavius Josephus. One can perhaps even see the discreet imprint of the Midrashic reading mentioned earlier in the illustration, with the mouse curiously bent over the buttocks of a character, even though the mice, according to the Vulgate, but also to other illustrations present in incunabula, seem to mill about in the fields surrounding the city without directly interacting with the humans.

This single mouse interacting equivocally with man may be the decisive element that led Scherf (2010) to claim that this illustration is the first visual representation of the plague in connection with rats, almost a century and a half before Poussin. But this hypothesis only shifts the enthusiasm some have for Poussin’s “maverick genius” to the Master of Lübeck, and misses a more thorough analysis of the different dynamics at work.

It is true that the Lübeck Master’s illustration is a precursor to Poussin’s work in several ways. They both illustrate the same text, and both present rats wandering around an unwell population, stricken with disease by God. It is more than likely that the Lübeck Bible illustration, or one of its lost copies (or inspirations), served as a model for Poussin’s other works. As has just been said, this model refers to a haemorrhoidal or dysenteric interpretation of 1 Sam 5-6: apart from the very contextual Midrashic sources mentioned earlier, which have nothing to do with the modern epidemic imagination and which have no medical significance, rats are never linked to dysentery or haemorrhoids. For this reason, there is no great conclusion to be drawn here either, as for the Crusader Bible, on the zoonotic considerations of the late fifteenth century. That being said, the hermeneutical leap made by Poussin’s painting must therefore be put into perspective. There is no doubt that it represents an epidemic perspective on 1 Sm 5-6, and commentators agree that it is inspired by several works representing the plague in an epidemic perspective, notably Il Morbetto (Barker, 2004, 2021; Hipp, 2007; Keazor, 1996) engraved around 1515 by Marcantonio Raimondi. “Poussin’s depictions of people trying to avoid plague in various ways: by running from the city, by pinching their noses in the vicinity of victims, and by blocking their eyes to avoid terrifying sights” (2021) references straight to the pestilential imagination of the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries. Nevertheless, all these elements are additions to a series of features that are common in the depiction of 1 Sm 5-6. In addition to the change from haemorrhoidal disease/dysentery to bubonic plague, Poussin’s painting reiterates rather than re-semanticize elements of the iconography of biblical illustrations.

The parallel with an engraving by Matthäus Merian representing 1 Sm 5-6 made in 1630 (Köhler & Köhler, 2003), that is to say, the same year as Poussin’s painting, allows us to underline the way in which Poussin affixes epidemic elements to a scenography that can do without them. The primary element that emerges from this comparison is that the main object of fear of the Philistines in both images is in fact the destruction of the statue of Dagon. In this sense, Hipp notes that: “It had been argued in early modern biblical commentary that the Philistines were punished not only for the theft of the ark, but also for their practice of idolatry,” but this is also true for medieval commentaries: Bèdes the Venerable and the Glossa Ordinaria, to cite two examples of interpretative sources of authority in the Middle Ages, emphasize that the Philistines, representing the gentiles as a whole, are struck down because they do not renounce idols, even though the Ark, the symbol of Christ or of the Gospels, was given to them by God. Also, if, as Boeckl points out, there is already a link since the sixteenth century between the representation of the plague and idolatry, one can only note Poussin’s affixing of the plague to a motif already long established on idolatry, and which one sees expressed independently the same year in Merian. Also, if we cannot invalidate Boucheron’s position that Poussin is making a “thucycidian rereading” (2021a,b) of the biblical passage, it is, however, necessary to underline that the idea of panic and disorganization is already, in addition to the iconographic parallels on the destruction of the statue of Dagon, present in the Vulgate, which speaks to us about “Confusion of death.”[15] The “rereading” can, on many points, be understood as a simple reading. The idea of representing pests in the city rather than in the countryside, where they are supposed to be, is consistent with what is commonly seen in medieval bibles (Berger, 2007), where it is a visual way to compile several elements or episodes of the story in a single image. Burgess (1976), if he admits that the rodents present on the painting of Poussin are not to be read in zoonotic key but well with 1 Sm 5-6 and its iconographic tradition, nevertheless asserts on the basis of Laurent Joubert’s 1566 Traité de la peste that the rat in the foreground of the painting is a symbol of pestilential danger. Joubert indeed puts the sudden appearances of creeping creatures, such as flies, spiders, especially those accustomed to living hidden like snakes, moles, and rats, are seen as a harbinger of the arrival of a pestilential disease. Nevertheless, Joubert speaks of creature swarms and not of a singular creature. Second, Joubert’s observation is by no means an advance on the epidemic thinking of early modernity. Joubert’s text is merely a reworking of Pliny the Elder, who already describes how pests have abilities to foretell all sorts of disasters - although he lends mice and rats special talents in this regard (8:42 -43, 82). Also, this rat, stoic in this moment of crisis, is no more a symbol of danger than any of the other rats depicted so far in the iconographic tradition of 1 Sm 5-6 and carries no significantly different connotation than the rats of the Lübeck or Merian Bible.

Thus, if we can see in Poussin an embryo of an epidemic reading of 1 Sm 5-6, it is in a much less organic way than it is commonly presented, the painter superimposing more than he re-semanticize. Moreover, despite the circulation of engravings and reproductions of the painting from the last quarter of the seventeenth century (Blunt, 1966), it was not until 1725 that Jacob Schezchzer proposed in Physica Sacra the first consistent exegesis of 1 Sm 5-6 as presenting an epidemic of bubonic plague, and this explanation itself remained largely ignored for another century.

6 Syphilis: The One No One Bet on

In his pioneering work on the history of the idea of epidemic and contagion, C. E. A. Winslow wrote: “the Black Death was the great teacher in this field. A preliminary course was, however, offered by leprosy and, at the end of the fifteenth century, a post-graduate course by syphilis” (Winslow, 1944). If leprosy and the black plague do not seem to have had an impact on the reading of 1 Sm 5-6, syphilis did begin to move the imagination, although only in the seventeenth century and in a very diffuse way.

The new translations of ophelim, in particular “marisca” that was proposed by Vatable, as well as the new philological considerations revealing textual problems having been lenited by the Septuagint and the Vulgate, stimulated the exegetes and invited them to propose new hypotheses for the comprehension of the term and the text. It is in this context that several minority proposals appear (or reappear), such as that of cancer, taken from the reading of the extracts of Aquila contained in the Hexaples, or of the organ descent - “ani projectionem” (Cornelius, 1687, Commentarius…, pp. 240–244; Calmet, 1718, pp. 386–388; Wegner, 1699, pp. 240–244). Cornélius a Lepide, after having listed all the known diagnoses will write, in the prolongation of the medieval idea of combination and confusion of diseases, in his commentary of 1639: “It seems that this disease was unique and new, and therefore not single, but many, singularly sent by God as a punishment to the Philistines”[16] (240–244). While he systematically reports every diagnosis to his diagnostician, Cornelius a Lapide nevertheless makes an exception, writing: “Others, venereal disease”[17] (240–244). This small allusion represents, to our knowledge, the first witness to a syphilitic reading of 1 Sm 5-6, and by the same token the first proposal for an epidemic understanding of 1 Sm 5-6, presenting a contagious disease that spreads via sexual contact. Given the extremely allusive nature of the text, it is nevertheless difficult to understand the reasoning behind the hypothesis without risking projection. Nevertheless, we can note Wilkinson’s description of the symptoms: “in its secondary stage it produces large soft warty swellings around the anus,” and assumed that this syphilitic reading shifts the ophelim from the anus, where other hypotheses place them, to the periphery of the anus, thus distancing itself from the traditional duo of haemorrhoids and dysentery, cantered on a wound linked to the anus as the end of the digestive process.

An allusion to the “lue Venerea,” in all respects similar to the previous one, will be found in the work of Trapp in 1662 (422), who was until then considered, following Neustätter (1940) as the first to evoke this diagnosis. It is probable that he is simply repeating Cornelius a Lapide, whom he does not quote, however, because Cornelius a Lapide himself simply echoes sources that he does not present. If Cornelius a Lapide recognized that syphilis could possibly play a role in the infectious cocktail of the Philistines, Trapp sides with the common opinion of his time, based philologically and traditionally, that it would be a question of haemorrhoids. Calmet in 1718, names syphilis, but simply because he takes up the list of diagnoses established by Cornelius a Lapide, which was the most supplied of the time (Calmet, 1718). A quick reference can be found in Johann Scheuchzer, who compares the “mariscas” of the Philistines to that of people suffering from a “venereal disease,” but without further development (483–484). This syphilitic reading was not taken up by Philipp Gabriel Hensler in his 1783 treatise on the history of the disease. This absence is not significant, however, because Hensler (1789) is a supporter of an American origin of the disease, and is therefore not interested in ancient sources. It was Haeser who, in 1839, laid the first stone of a syphilitic diagnosis:

In ancient times, it appears that leprosy, in its most developed form, was occasionally able to spread epidemically, much like syphilis did later on. At least to the Philistines, during an epidemic, golden images of their anorectal condylomata seemed to be a sufficiently valuable offering for appeasing the deity (1839, p. 19).

This leprous reading of 1 Sm 5-6, which takes the form of a diagnostic apax, is the first witness of a real epidemic understanding of the text and paves the way for a complete syphilitic exegesis. Indeed, for Haeser, as well as for some of his contemporaries, syphilis is a disease originating in Europe and having for ancestor leprosy, with which it shares multiple similarities (1839, p. 183).

The first clear and declared proponent of a syphilitic exegesis of the text appeared in 1848. It was the physician Johann Baptist Friedreich, who, directly inspired by Haeser’s remark a decade earlier, wrote:

Another view, that among the swellings, genital warts are to be understood, seems to have the most in its favor, for once the Hebrew word Efolim, which is considered authentic, is translated by Buxtorf as ‘marisca,’ and then, assuming a condition resembling syphilis, the rapid spread of the malady among several people, as well as its transmission from one place to another through the Philistines in charge of carrying the Ark, can be easily explained through contagion[18] (1848, pp. 244–245).

The term “Feigwarzen” (genital warts), used by Haeser, had already been proposed as a German translation of ophelim by J. F. von Meyer and represented the German parallel to Vatable’s “marisca.” If “Feigwarzen,” like its model, has a broad and polysemous medical understanding, Haeser reads it here in the marked sense of a syphilitic condyloma. In this excerpt, Friedreich well describes the “contagion,”[19] passing rapidly from man to man, in the context of a fully epidemic conception of 1 Sm 5-6. The absence of dysentery, the other historical “usual suspect” of 1 Sm 5-6, among the hypotheses studied by Friedreich can be explained by the progress of biblical philology, which led to a gradual loss of momentum of the hypothesis in favour of a more rigid perspective on the hemorrhoidal reading.

As interesting as the diagnosis produced by Friedreich is the refutation that he proposes of the hemorrhoidal diagnosis, that had until then for him the number, the antiquity and the philology as support:

Michaelis, Hezel, and subsequently Stark, believe that hemorrhoidal nodes should be understood in this context. However, it should be noted that not as many people are simultaneously affected by them and die from them as is claimed in the biblical narrative.[20] (1848, pp. 244–245).

Here, in a curious reversal, the symptoms of the disease take precedence over philology, and lethality and infectivity become the main criteria. The expression “that not so many people are afflicted with it at the same time and die from it”[21] (1848, pp. 244–245), marks, or at least testifies to, a theological turning point among some of the exegetes and physicians of the time.

If the exegesis of 1 Sm 5-6 had not, from antiquity to the first part of the modern era, been penetrated by the epidemiological imagination, it is because all interpreters relied on the tacit agreement that what was described was in the realm of the miraculous. The destruction of the statue of Dagon, the arrival of the mice and the mysterious swellings were three different miracles of God against the Philistines. In this, the interpreters were faithful to the biblical text, which presented all this as the fruit of the hardening of God’s hand. The illustration by the Lübeck master presents this direct divine agency, with God in Heaven pointing at the afflicted Philistines, as does this exegesis by Gottfried Wegner: “Moreover, God, not content with the idol having been removed and broken by itself, also wanted to punish its worshippers”[22] (1699, pp. 38–41). The idea, proposed by Cornelius a Lapide, of the unique and original infectious cocktail concocted by God for the Philistines fits totally into this paradigm of the miracle, where the laws of nature can be transgressed, or at least revealed in unexpected and unpredictable forms. But in the nineteenth century, with the ideas of the Enlightenment, and the circulation of criticisms brought to miracles by Hume, Spinoza, Kant, and many others, the model falters. The idea of fatal haemorrhoids rapidly reaching an entire population became improbable because it seemed to defy the observable laws of nature. The confrontation between the hemorrhoidal and syphilitic thesis observed in Friedreich actually reflects a collision point between two incompatible paradigms. The change in the disease diagnosed here does not so much reflect an advance in the medical knowledge of the time, as a change in the way of conceiving the Bible, God, and his relationship to the world. The epidemiological paradigm in the interpretation of 1 Sm 5-6 is, in essence, rationalistic, relying on human, viral, parasitic, or bacterial agency, but not on divine agency, and is part of the “new social and epidemiological consciousness” (Susser, Stein) which arose in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. More specifically, the idea of syphilis, by virtue of its sexual transmission, implies that scourge is the result of the sexual misconduct of the Philistines – who are already the target of a moral a priori in romantic literature (Jobling and Rose, 1996) – an outlook consistent with a morality and ethic-based perspective on the World and the Bible, as promoted by Kant, among others (Rimke, Hunt), in his Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason. Rationalism is the epidemic reading of 1 Sm 5-6’s place of sociogenesis, as it will be for the bubonic plague.

This paradigmatic shift occurred slowly, however, without any great revolution or maverick thinker. Haeser and Friedreich do not seem to have convinced many of their contemporaries, and their two diagnoses remained without any real echo among biblical scholars as well as syphilis experts, and Rosenbaum, although he adheres to the pre-Columbian thesis and deals with several biblical examples, does not mention it in his 1845 work. The syphilitic reading presented by Church in 1939, as part of his defence of the pre-Columbian origin of the disease, is to be read as an epiphenomenon. He does not seem to have read Haeser or Friedreich, and his etymology of ophelim is original. Church in 1939 states, “This word originates far back of the historical times in the Bible; original was ophelim, or omphelim…” When the Hindu Yogi, thousands of years ago made this sign and said ‘Om’, he was indicating the female. The word Phthallus has come over into Greek and Latin with the same significance that it has in medicine today. So, instead of Emerods, “they had woman-man diseases on their secret parts”, and the context explains itself as an epidemic of sexual diseases and the consequent deaths and misery. Neustatter (1940), supporting within the same paradigm the hypothesis of bubonic plague, will refute this proposal the year after (see also Wilkinson, 1977).

7 Bubonic Plague: Caught between Two Stools

As mentioned earlier, Neustätter (1942) has already done an admirable job in tracing the first occurrence of the plague hypothesis in 1725 in the Physica Sacra by Jacob Scheuchzer. He is nevertheless surprised that, despite the wide distribution of Scheuchzer’s book, and its translation into Latin and then into French, his hypothesis is not taken up anywhere, except in the quotation of Calmet’s notes arranged by C. Taylor and published in 1814. On the basis of the previous presentation of the two paradigms, miraculous and epidemic, an explanation can be found for this absence. First, it should be noted that Scheuchzer does not propose the plague as an alternative diagnosis, but as a complementary diagnosis to the ophelim. Scheuchzer indeed follows an idea expressed by Samuel Bochart in his Hierozoïcon (1663), who proposes to see the tehorim as something distinct from the ophelim, and not as a synonym. Therefore, in the inspiration of Cornélius a Lépide, Scheuchzer cocktailize two diseases: the “mariscis” (tehorim), not lethal, with the bubonic plague (ophelim), very lethal. Also, Scheuchzer’s explanation, if taken as a whole, represents a paradigmatic in-between, each of the two diseases belonging to a different paradigm, which can actually do without the other according to a simple principle of economy. Why go through the plague to explain lethality, in an understanding of the universe where God can miraculously create lethal haemorrhoids? From this angle, Scheuchzer’s hypothesis appears unnecessarily complicated, and little explains why it has been largely neglected.

Calmet’s note, apart from the fact that it is the only one referring to Scheuchzer, is also interesting for its positioning between the two paradigms: while supporting the hypothesis of haemorrhoids (or fistulas) that would have suddenly appeared among the Philistines, assuming a divine miracle, Calmet nevertheless seeks to respond to the objection of the low rate of morbidity, which he found in Scheuchzer. He then proposes four rationalistic leads, thus taking the fold of the epidemic paradigm: either the disease was more virulent at the time or it was accompanied by “other disorders of a fatal nature” (Taylor, 1814, p. 86). Either the weather aggravated the disease or the treatment that the Philistines tried to apply backfired and made them even sicker, or another more lethal disease accompanied the haemorrhoids, such as the plague (here the quotation from Scheuchzer is integrated). This note, denoting by its weak capacity to convince of the difficulty to make the two modes of thought compatible, is sufficient to complete or answer Scheuchzer, but in reality retains the miraculous paradigm only by one thread: the fact that the question of contagion is not asked. However, as was said earlier, the question will be put on the table by Haeser and then Friedreich. A similar in-between paradigm position is found in the 1885 English Revised Version (ERV) of the Bible, which translates ophelim as “tumors,” but offers in a marginal note “or plague-boils; as read by the Jews emerods,” not deciding for one paradigm or another.

It is therefore Otto Thenius, in his commentary on Samuel’s book in 1849 (one year after Friedreich’s syphilitic diagnosis in 1848), who first proposed an absolute bubonic plague diagnosis. Neustätter hypothesizes that Thenius was inspired by Scheuchzer without quoting him. It is possible but it must be understood that Thenius interprets the whole of scourge as bubonic plague, whereas Scheuchzer distinguished between haemorrhoids and a complementary disease which was bubonic plague. Thenius (1849) rather places his foundation in the translation of Aquilla (p. 27), who, according to him, already spoke of a glandular bubo (and not of cancer as the exegetes had understood it until then). Like Friedreich the year before, Thenius shifts completely to the epidemic paradigm, with a hypothesis that met with a certain success among rationalists, unlike Friedreich’s. Thus, Julius Wellhausen, a central figure in the historical criticism of the Bible, spoke of “Pest” in his work of textual criticism of the book of Samuel published in 1871.

8 1897: The Birth of an Ancestor

So far, we have seen the birth of Neustätter’s hypothesis, and the paradigmatic framework in which it evolves. However, if we have shown at the end of the last section that the idea of the bubonic plague had found an echo among certain critical biblical scholars, it remains to explain the path it took to become the majority interpretation of this passage during the twentieth century, and even up to the present day, and how the idea managed to escape from the circulation of critical biblical scholars to reach a wide audience.

In 1897, a sudden acceleration in the popularity of the hypothesis occurred with a small written intervention by the hygienist Arnold Netter. Here, the link between 1 Samuel and the Bubonic Plague makes a “species leap” from biblical exegetes to epidemiologists, but this passage implies some discreet but important epistemological adaptations. In the context of the debates between hygienists on the risks that plague represented for the twentieth century Europe, the accounts of plagues in India and China (Calcutta, Hong Kong, etc.) as well as the recent hypotheses (not yet unanimously accepted at the time) on the role of flies and rats (Yircin and Kitasato) in the transmission of the disease, Arnold Netter presents in the Revue d’hygiène et de police sanitaire of 1887: “a historical document that might lead one to believe that the relationship between plague and rats has been recognized for much longer. This document is provided by the Bible, Book 1 of Samuel, chapters VI and VII.” After summarizing the biblical episode, Netter comments on the text as follows:

The deadly disease that struck the Philistines was undoubtedly the plague. In favor of this opinion, already defended by Thenius, we can invoke the severity of the disease, its epidemic aspect, the existence of tumors in hidden parts, groin buboes and non-fatal cases in which only buboes are observed. The images of mice that accompanied the images of tumors would imply a relationship known to priests and diviners between the epidemic and rats or mice (there’s only one word in Hebrew for both species). (my translation).

A subtle difference marks a break between Netter’s position and that of Thenius, of which he nevertheless claims to be the author. Netter indeed speaks of the Bible as a “historical document.”[23] Thenius, as a member of the Historical–Theological Society[24] in Leipzig and a pioneer in grammatical–historical criticism of biblical texts, presented a relatively sceptical perspective on the historicity of the first chapters of the book of Samuel, detecting a “legendary aspect”[25] in them. Thenius treats 1 Samuel 5-6 with the reservation that it is primarily a literary source, whereas Netter sees it as a purely documentary source. It should be remembered here that Netter was, in addition to being a physician, an influential figure in Jewish associative networks (Weyl, 1996), creating a strong link with the rabbinical world which could give him a predisposition to link a face value reading of the Hebrew Bible with his research field. One should not forget the polemical context in which Netter expressed himself: in 1887, although the research of Yersin and Kitasso created enthusiasm in certain hygienist circles, their discovery on the plague bacillus and the role of the rat was far from being unanimously accepted. Simond’s advances on the rat flea dated only from the previous year (Latour, 2001), and the first works of Vladimir Vladimirovič Favre on Central Asian marmots (1899), the main permanent carriers of the plague, will be published only the following year. One of the major objections to the rat-flea transmission hypothesis was the fact that bubonic plague had never been linked to rats before. This observation has since been corrected: medieval Arabic sources have shown that the link between the presence of rats and the plague was already established in the Middle Ages, and an explanation for the absence of early European sources was found by Audoin-Rouzeau in 2003: in cold regions, rats hide to die, while in warm regions, they come out in the open to do so, making their presence, and their link with the plague, more obvious. Nevertheless, the defenders of the hypotheses of Yersin, Kitasso, and Simond found themselves in a rather uncomfortable situation where the only parallels available were in the colonial East. In the context of the “epidemiological orientalism” (Varlik, 2017; White, 2023), and the idea of the civilizing mission of the West in matters of hygiene, the fact that the colonized populations of China (Proust, 1897) and the Himalayas (Netter, (1887) and Lake Victoria (since the work of: Zupitza, 1899)) not only had superior epidemiological knowledge to Westerners, but they were also at the origin of relatively effective prophylactic measures (such as temporary departure from contaminated areas) which the West had been unable to implement and could be inspired by, was, if not problematic, at least outside the commonly used paradigm (for reference, see how prophylaxis in China is described by Proust). Also, rhetorically, Netter’s biblical parallel offered the possibility of saving the West’s face: one of his founding texts, relating events long before the practices of the colonized populations, already attested to the link between plague and rats. This association between plague and mice in 1 Sm 5-6 is the fruit of Netter himself: Thenius having written well before the work on the plague bacillus, buboes were the only element he mobilized in his diagnosis.

Despite the fact that he was the importer of this hypothesis into the field of epidemiology, Netter (1900) does not seem to have given it too much importance: not only does he make no reference to this biblical parallel in his 1900 work on the plague, but it does not even include Palestine in its list of endemic foci of the ancient world (p. 7). It was his colleague Adrien Proust, who repeated Netter’s words almost verbatim in his book of the same year, which will contribute to its diffusion to a wider public, and which will remain, more than Thenius or Netter, the reference for this exegesis. Adrien Proust will nevertheless add an element to Netter’s explanation, giving it more flesh and scope: the reference to Poussin’s painting, mentioned earlier. Even before presenting Netter’s reading, Proust writes:

The death of rats was not reported in the epidemics of the Middle Ages. However, Poussin depicts a number of rats in his painting of the Plague of the Philistines, in the Musée du Louvre. Diemerbrock spoke of the disease affecting birds, and Mead wondered whether the infection of these animals might not provide a means of control for disinfection. (p. 6).

In doing so, he solves the problem of the lack of historicity of the relationship between the plague and the rat: it is remarkable that Proust mentions Poussin’s painting before the biblical text, and without any causal link between the two, thus showing in a retrospective vision, that before the end of the nineteenth century when he expresses himself, the West had already understood the plague as a zoonosis since antiquity, with an attestation serving as a milestone at the beginning of the modern era. In the same year, the French neurologist Henry Meige took up the hypothesis and said, based on his observation of Poussin’s painting, that the seventeenth-century Europeans must have had much the same conception of the spread of the plague as Netter and Proust. In his article of the following year, Georg Sticker explains the decisive argumentative weight that history plays in supporting Yersin’s and Kitasso’s theories, while presenting as an established fact the idea that the Philistines would have been affected by a bubonic plague related to rodents:

What gives a solid foundation to all these only partially proven hypotheses is the fact of the plague among mice and rats and the undeniable experience that the plague among these subterranean creatures is closely connected to the plague among humans. In almost every account by chroniclers describing severe plague times, we find the specific information that before and alongside the outbreak of an epidemic, subterranean animals emerged from their hiding places and died in great numbers. Twelve hundred years before Christ, the Philistines recognized the connection between bubonic plague and the infestation of mice.[26] (Sticker, 1898).

In 1899, Tidswell and Dick also reinforced this perspective, which is also rooted in biblical exegetes, Henry P. Smith writing in his commentary of the same year: “we can hardly go astray in seeing a description of the bubonic plague.” In the space of a year, the pattern changed: where Netter brought the biblical passage as a parry to the frightening emptiness of the documentary absence of the link between rats and plague, Sticker made the first stone of a long history of recognition of the link between the two things. Three years after Simpson (1905) who will also do it, Sticker will support the line of his previous publication in his book on the history of the plague published in 1908, where the “Philisterpest” will be mentioned many times to support the existence, from the first recorded plague, of a link with rats, thus creating a form of circular reasoning:

Only a single family of animals is consistently present in all forms of plague involvement: the family of mice. Mice, especially rats, appear as harbingers, as warnings, as spreaders, and as victims of the plague. Throughout the centuries, rats and mice have never been absent from the epidemiology of the plague. From the mice during the Philistine plague around 1060 BC to the rats that are feared today in all continents as plague heralds, tracked as plague carriers and spreaders, an uninterrupted chain stretches.[27] (Sticker, 1908, p. 134).

It is also noteworthy that, somewhat contradicting his hypothesis on the role of rats as carriers of the disease, Sticker proposes another original interpretation of the calamity of 1 Sam 5-6, making him the father of another more minor interpretative current, that of the Ark as a bacteriological weapon:

One might be tempted to extract even more from the text, namely, to attribute to the Jewish high priests the same skill that Ammianus attributes to the Chaldeans, that of containing and preserving the plague germ. (Sticker, 1908, p. 71).

The first wholesale refutation of Netter’s and Proust’s exegesis appeared in 1901 in an article by Rudolf Abel, a Hamburg hygienist, who disagreed with the hypotheses of Yersin’s supporters. For Abel, if Yersin and Kitano had shown that rats could indeed carry the bubonic plague, they were not the first vectors of it:

The view that the plague is primarily a disease of rats and certain other rodents, and only secondarily affects humans, goes too far. The plague is a human disease and not merely a disease of animals transmissible to humans; typically, humans are the most dangerous disseminators of the disease, not rats.[28]

In his article, Abel undertakes the opposite enterprise of Sticker, namely, to dismantle the idea of the long duration of the perception of the link between bubonic plague and rat. Concerning the Philistine plague, Abel refers to the interpretative, not literal, character of the reading proposed by Sticker, Proust, and Netter:

Of course, it is open to anyone to attribute a deeper meaning to the passage. However, one must not forget that doing so involves speculations that lack any factual basis. To even claim, as Sticker does, that “the Philistines recognized the connection between the bubonic plague and the infestation of mice” is attempting to present a purely hypothetical view as a confirmed event with far too much certainty.[29]

Abel also refuses to see historical evidence of the connection between the rat and the plague in Poussin’s painting, saying:

But I know of only one image that depicts rats. It is from Nicolas Poussin around 1630, and what does it portray? The plague of the Philistines, which we mentioned earlier, in which the Bible simultaneously mentions a rat infestation. However, none of the five rats depicted in the image shows signs of illness; on the contrary, they all appear to be in the best of health–at least that’s what my eyes, somewhat sharpened through long experience with rats in the laboratory for animal behavior, can discern in the illustration.[30]

Nevertheless, Abel’s publication did not stop an interpretative paradigm that already had a consensus and that reached its climax with Merrins’ analysis in 1904, which provided the most detailed diagnosis of the Plague, going so far as to make observations on the climatology to support his thesis.

In 1905, Skinner plays on the same historical terrain as Sticker and Abel when he wants to present his third-party hypothesis presenting cattle ticks as the origin of the bubonic plague. After presenting data found in the colonies, in this case in India, he formulates his hypothesis and then begins an exegesis of 1 Sm 5-6, this time focusing not on rats but on cattle that transported the Ark between the Philistine cities and that caused heavy casualties in Beit-Semesh later in the story. This interpretation of the text, although it has no posterity in the continuation of medical hypotheses, underlines the interpretive dynamic at work at that time, which consists in first forming an opinion on the true vector of the plague on the basis of observations and experiments carried out in Asia, then establishing an exegesis of the Plague of the Philistines before completing the argument with other historical observations and medical data.

The picture of the birth of the epidemic paradigm of 1 Sm 5-6 would nevertheless be incomplete if we omitted another element, of major importance but more discreet, obscured by the repercussions of the proposals of Netter and Proust in 1897. For in this same year 1897, another bacilli was discovered, that of dysentery, by Kiyoshi Shiga (1898). From then on, the dysenteric hypothesis was given new conceptual elements (see Flexner, 1900) allowing it to be revived. If, as mentioned earlier, Johann Baptist Friedreich and his contemporaries of the nineteenth century that dysentery was a hypothesis that was tested by medical and philological knowledge, it now becomes a hypothesis that can be expressed in the same terms as the plague. If medieval and early modern commentators are not called upon, it is Flavius Josephus who will be re-evaluated in his medical analysis of the disease, Shrewsbury saying: “It is possible that Josephus had access to authentic material that has since been lost; it is certain that he was many centuries nearer the ancient Jewish tradition than we are, and, though it appears to be fashionable in some quarters to decry the value of tradition as an adjunct to history, it is not wise to ignore it,” and Russell (2005, 2006) later adding that he was in the context of the reading of 1 Sam 5-6: “a better Hebraist than any modern translator” (Postcript…). If Shrewsbury will provide in 1949 the modern dysenteric rereading of the text by proposing to see in it either an epidemic of Shigella sysenteriae or of Shigella flexneri, it is nevertheless from the beginning of the twentieth century that the old hypothesis of dysentery will receive this anachronistic epidemic colouring for all those who will reread it or those who already supported it (Underwood, 1964). Thus, in the space of the decade or so that marked the turn of the century, the imaginary of the Philistine scourge changed for the general public, which shifted it into the epidemic paradigm. From then on, the doors were open for other alternative epidemic readings, such as that of Hirst (1953), evoking cholera as the cause of the Philistines’ sickness.