Abstract

Undergraduate organic chemistry has been found to be historically difficult for students and one area where students struggle is organic reaction mechanisms. The difficulties students face with reaction mechanisms has been a source of interest in chemical education research but most studies done have been purely qualitative. An assessment tool that could be used on a large-scale for instructors to gauge the difficulties their students face, would be useful. The aim of this pilot study is to use Rasch analysis to establish the validity and reliability of the concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms inventory (RMCPI). The test, containing 25 items, was administered to first semester organic chemistry students (N = 44) at a mid-sized university. The data was analyzed using Rasch techniques to explore the dimensionality of the instrument, the difficulty of the items, the item fit, and the reliability. The results indicate that the instrument is unidimensional and most of the items fit well to the dichotomous Rasch model. The test was found to be difficult and this will be explored further by increasing the sample size, administering the test to students from other universities and increasing the number of items on the inventory.

Introduction

Organic chemistry has a reputation for many students of being a gatekeeper course: difficult, complex and with some material that students may perceive as irrelevant (Grove, Cooper, & Cox, 2012). An important topic in this course is mechanisms of reactions. Organic reaction mechanisms are represented using curved-arrows which depict the movement of electrons during the process of bond breaking and bond forming. This helps visualize the reaction as the reactants are converted into products. The difficulties students face with understanding organic reaction mechanisms and the alternate conceptions they develop have been a source of interest in chemical education research since the understanding of this fundamental topic is essential to mastering the course. Most of these studies have focused on redesigning the introductory organic chemistry curriculum and understanding how students use their organic chemistry knowledge to solve mechanistic problems (Bhattacharyya, 2013; Bhattacharyya & Bodner, 2005; Flynn & Ogilvie, 2015; Grove et al., 2012; Grove, Cooper, & Rush, 2012). These studies have focused on individual students’ perceptions but there have been no intervention tools developed to assess the difficulties that an entire organic chemistry class faces and this understanding would help instructors address these problem areas. The purpose of this study is to assess and validate an inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms (RMCPI).

A crucial component of developing instruments is establishing psychometric properties which provide robust information about the instrument and its functionality. Establishing the validity and reliability of instruments like concept inventories, gives valuable information to the users regarding the quality of the items which is useful when using these instruments as diagnostic tools (Barbera, 2013). For instance, instructors will be able to use the RMCPI instrument to assess their students appropriately and determine if they are prepared to begin the study of organic reaction mechanisms.

A number of instruments developed in chemical education utilize Classical Test Theory (CTT) to establish validity and reliability of the data obtained with concept inventories (Brandriet & Bretz, 2014; Bretz & Murata Mayo, 2018; Chu, Treagust, Yeo, & Zadnik, 2012; Dick-Perez, Luxford, Windus, & Holme, 2016; Kamcharean & Wattanakasiwich, 2016; McClary & Bretz, 2012; Othman, Treagust, & Chandrasegaran, 2008; Prince, Vigeant, & Nottis, 2012; Sreenivasulu & Subramaniam, 2013). CTT is utilized regularly by researchers as the first step in establishing validity and reliability because it is based on relatively weak assumptions which are easily met by test data, simple mathematical techniques are used and moderate sample sizes are needed (Hambleton & Jones, 1993). The major drawback is item and person parameters are sample dependent. Item Response Theory (IRT) on the other hand is based on strong assumptions which are not easily met by the data but if the model fits the data then item and person parameters are sample independent (Hambleton & Jones, 1993). IRT models like the Rasch model, generally require larger sample sizes and this proves to be a drawback for researchers (Hambleton & Jones, 1993). Rasch analysis helps researchers determine the probability of an examinee answering an item which gives details on the test scores of an examinee population (Hambleton & Jones, 1993). This would be very useful information since the RMCPI instrument will be administered to organic chemistry students from different universities.

Literature review

Boone and Scantlebury (2006), used a science achievement test to describe the strengths of using the Rasch model as a psychometric tool and analysis technique. They state that Rasch techniques help researchers improve the quality of quantitative measurements by assisting them in monitoring scales and improving scales over time. This is especially useful for high-stakes assessment tests that are used in various areas of science. The strengths of using Rasch analysis to develop higher quality science education instruments has been reported and this helps science educators increase the rigor of instrument development and analysis (Boone, Townsend, & Staver, 2011).

In chemical education most of the instruments developed are relatively new (Arjoon, Xu, & Lewis, 2013). Therefore reporting the validity and reliability of these instruments is of great importance. Arjoon and co-workers (Arjoon et al., 2013) investigated the psychometric evidence reported in articles published in the Journal of Chemical Education between 2002 and 2011. It was found that researchers favor reporting test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and internal structure over response process validity. Thus there is a need for chemical educators to understand the importance of the quality of assessment tools used in research and to strive to give a detailed report of the quality of assessment tools which would assist future researchers.

Rasch analysis was used to assess the complexity of middle and high school students’ knowledge in various content areas of chemistry by predicting item difficulty (Bernholt & Parchmann, 2011). Rasch analysis was also used for investigating instrument functioning and item difficulty and person ability which helped validate an ordered multiple-choice test for assessing students’ understanding of matter (Hadenfeldt, Bernholt, Liu, Neumann, and Parchmann 2013). A similar study (Wei, Liu, Wang, & Wang, 2012) used partial-credit Rasch model to determine the validity and reliability of a computer-modeling based instrument to assess students’ understanding of matter. These studies demonstrate the limited use of the Rasch model in chemical education.

The Rasch model has been utilized sparingly while designing concept inventories. Rasch analysis was used on a thermochemistry concept inventory (TCI). It was reported that all the items showed good functioning, the TCI was well targeted to the ability of students and the TCI is a measure of overall student ability providing evidence of concurrent validity (Wren & Barbera, 2014).

The Rasch model however has been used to add to psychometric data on existing concept inventories. The Chemical Concepts Inventory (CCI) (Mulford & Robinson, 2002) has been the source of further investigations. A method based on Rasch modeling to measure learning gains in chemistry was introduced (Pentecost & Barbera, 2013). Gain analysis was compared using normalized learning gain calculations and Rasch modeling on data using the chemical concepts inventory (CCI) and it was found that Rasch modeling gave information on students’ learning of specific content by comparing item difficulty and student ability on the same scale. Additions were made to the existing psychometric data on the Chemical Concepts Inventory (CCI) by conducting CTT and Rasch analysis (Barbera, 2013). The unidimensionality, item fit and, reliability were reported using Rasch analysis.

In addition to Barbera’s (Barbera, 2013) work utilizing CTT and Rasch analysis to validate a concept inventory, these two models have been utilized together in chemical education research. CTT and Rasch analysis was employed to study the impact of the flipped classroom on students’ performance and retention rate where ACS general chemistry exam scores were used from pretest and posttest data and the items on the exam were validated (Ryan & Reid, 2016). CTT and Rasch analysis was also used to test the validity of the Chemical Representations Inventory (CRI) when administered to students and instructors and it was reported that the test functioned reasonably well for the intended purpose (Taskin, Bernholt, & Parchmann, 2015).

The presence of concept inventories in organic chemistry is lacking with the exception of ACID I (McClary & Bretz, 2012), which was used to test organic chemistry students’ alternate conceptions of acids and bases, and it was validated using only CTT. Hence the use of Rasch techniques to validate concept inventories in organic chemistry is absent. Rasch analysis was however used to explore the relationship between person ability and item difficulty on a questionnaire studying teaching assistants’ pedagogical content knowledge in 1H NMR spectroscopy (Connor & Shultz, 2018). Rasch techniques were used to validate an instrument developed to measure graduate students’ pedagogical content knowledge of thin layer chromatography (Hale, Lutter, & Shultz, 2016). These studies demonstrate that there are examples of Rasch analysis being utilized in organic chemistry education but none have utilized Rasch analysis to validate concept inventories.

These studies prove the importance of using Rasch analysis techniques in order to determine the quality of assessment tools in chemical education. Rasch techniques are useful when designing concept inventories to not only establish the reliability and validity of the instrument but to also place item difficulty and person ability on the same scale which gives information about the test scores of different examinee populations (Barbera, 2013). Rasch analysis will help establish the quality of the RMCPI instrument when administered to students from different universities and give psychometric data on an assessment tool in the field of organic chemistry which lacks such diagnostic tools.

The present study

The focus of the present study is to make use of Rasch analysis techniques to establish the construct validity and reliability of the RMCPI instrument. With this focus in mind, the study is guided by the following research questions:

Does person separation reliability (estimate of how well one can differentiate persons on the measured variable) support the reliability of the RMCPI items?

Is the RMCPI data unidimensional?

What is the difficulty of the items for the RMCPI data?

How well do the RMCPI items fit to the Rasch model?

Does the item difficulty data obtained from Rasch analysis compare with the theoretical construct map?

Method

Participants

Participants were 44 students from a first-semester organic chemistry class at a mid-sized university in the Rocky Mountain region of the U.S. Of the participants, 78% were female and the rest were male. All participants were in the age range of 19–22 years.

Instrument

The Reaction Mechanisms Concepts for Proficiency Inventory (RMCPI) is designed to assess undergraduate students’ understanding of the topics important for gaining proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms.

The pilot version of the RMCPI contains 25 items in a multiple-choice format. The responses were scored as correct or incorrect and they were aggregated to yield the total score. The maximum possible score on the RMCPI was 25 and the lowest possible score was 0. A higher score indicated that students had a lower level of alternate conceptions for these topics which are important for organic reaction mechanisms.

The items in the pilot version of the RMCPI are organized under 13 concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms: atomic structure, electronic configuration, Lewis structures, bonding, molecular geometry, hybridization, functional groups, polarity, acids/bases, electrophiles/nucleophiles, stereochemistry, resonance and inductive effects and stability of intermediates. There are 2 items under each concept except for functional groups which has only 1 item.

An example of an RMCPI item is shown below:

Please answer the following multiple-choice questions on a scantron and answer the demographic questions directly on the test.

Which is more acidic and why?

Thiol because S is more polarizable

Thiol because O–H bond is stronger than S–H bond

Thiol because it is more stable with a positive charge on it

Alcohol because oxygen is more electronegative

Alcohol because it is able to hold charge better

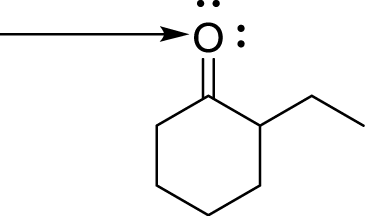

This item tests students’ understanding of the concept of acids and bases which was identified as one of the concepts important for gaining proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms. An example of an item in the RMCPI that tests the concept of hybridization is shown below.

What is the hybridization of the labelled atom in the following molecule?

sp

sp2

sp3

These items are therefore designed to test the conceptions of students towards these topics that are important for organic reaction mechanisms. The instrument also contains demographic questions on the gender, major and year of study of the participant.

Procedure

The only criterion for participant selection was that the participants had to be in a first semester organic chemistry class. The test was administered to the participants 1 month into the semester right before they started the study of reaction mechanisms. All the participants were from the same university.

The participants were provided with a periodic table and they were not allowed to use any other instructional materials during the test. The participants completed the test in approximately 30 min. The test was administered in person and participants took it during their regular class period.

Analysis

The main aim of the present study is to establish the reliability and validity of the RMCPI instrument using Rasch analysis. The Rasch model is a probabilistic model and the principle is that a person with a greater ability than another person should have the greater probability of answering any item. Also, if one item is more difficult than another, the probability of answering the easier item is higher (Bond & Fox, 2015). The general Rasch model equation is given below where item difficulty is denoted by δi and person ability is denoted by βn.

Equation 1 shows that the probability of correctly answering an item Pni(x = 1) where, n is person number and i is item number, is equal to the function of the difference between a person’s ability (βn) and the difficulty of the item (δi).

RQ 1 was aimed to be answered using person separation reliability which is an estimate of how well one can differentiate persons on the measured variable (Wright & Masters, 1982). This estimate is based on the same concept as Cronbach’s alpha and it gives information regarding the reliability of the instrument. The reliability estimate for persons range from 0 to 1 (Wright & Masters, 1982).

RQ 2 was aimed to be answered by analyzing the RMCPI data using principal component analysis (PCA) to see if it was unidimensional and if it fit well to the Rasch model. The data was also analyzed to see if the difficulty of the items is adequate for the RMCPI data using Wright maps in order to answer RQ 3. Wright maps place item difficulty and person ability on the same log-odds scale. The difficulty of items was also compared to the theoretical construct map to answer RQ 5.

RQ 4 was addressed using fit statistics to see how well the items fit to the Rasch model. This estimation begins with calculating response residuals for each person n and each item i. This is calculated as the difference between the actual response and the Rasch model expectation. These residuals are summarized in a fit statistic either as a mean square fit statistic or a standardized fit statistic. These fit statistics are characterized as outfit and infit statistics. The outfit statistic is an average of the standardized residual variance across both persons and items and gives emphasis on unexpected responses far from a person’s or item’s measure (Wright & Masters, 1982). The infit statistic is one where the residual are weighted by their individual variance so as to give emphasis on unexpected responses close to a person’s or item’s measure. Both fit statistics have an expected value of 1 but infit statistics is used more routinely because it is weighted and hence not sensitive to outlying scores. For a low stakes multiple-choice test the critical values for mean square fit statistics should be in the range of 0.70 – 1.30 (Bond & Fox, 2015). These fit statistics indicate whether the data accurately fit the dichotomous Rasch model.

Results

Reliability

The reliability of the RMCPI data is evaluated through person separation reliability (Bond & Fox, 2015). The separation reliability for items is 0.92 which is higher than the accepted value of 0.8 and hence it is adequate. The separation reliability for persons is 0.68 which is below the expected value which could be attributed to the relatively small size of the sample used in this study and the number of items in the inventory.

Unidimensionality

The Rasch model is based on the assumption that the scale is unidimensional which means that it measures a single latent trait (Bond & Fox, 2015). A latent trait is a hypothetical or unobserved characteristic or trait (Bandalos, 2018). For the RMCPI the latent trait can be defined as conceptual knowledge required for proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms. The unidimensionality within the Rasch model is analyzed by PCA of residuals. The PCA of the residuals for the RMCPI data, shows that 34.9 % of the total variance was explained by the Rasch model which suggests unidimensionality of the RMCPI data since the observed raw variance for measures is greater than 20 % (Bond & Fox, 2015).

Item difficulty and person ability

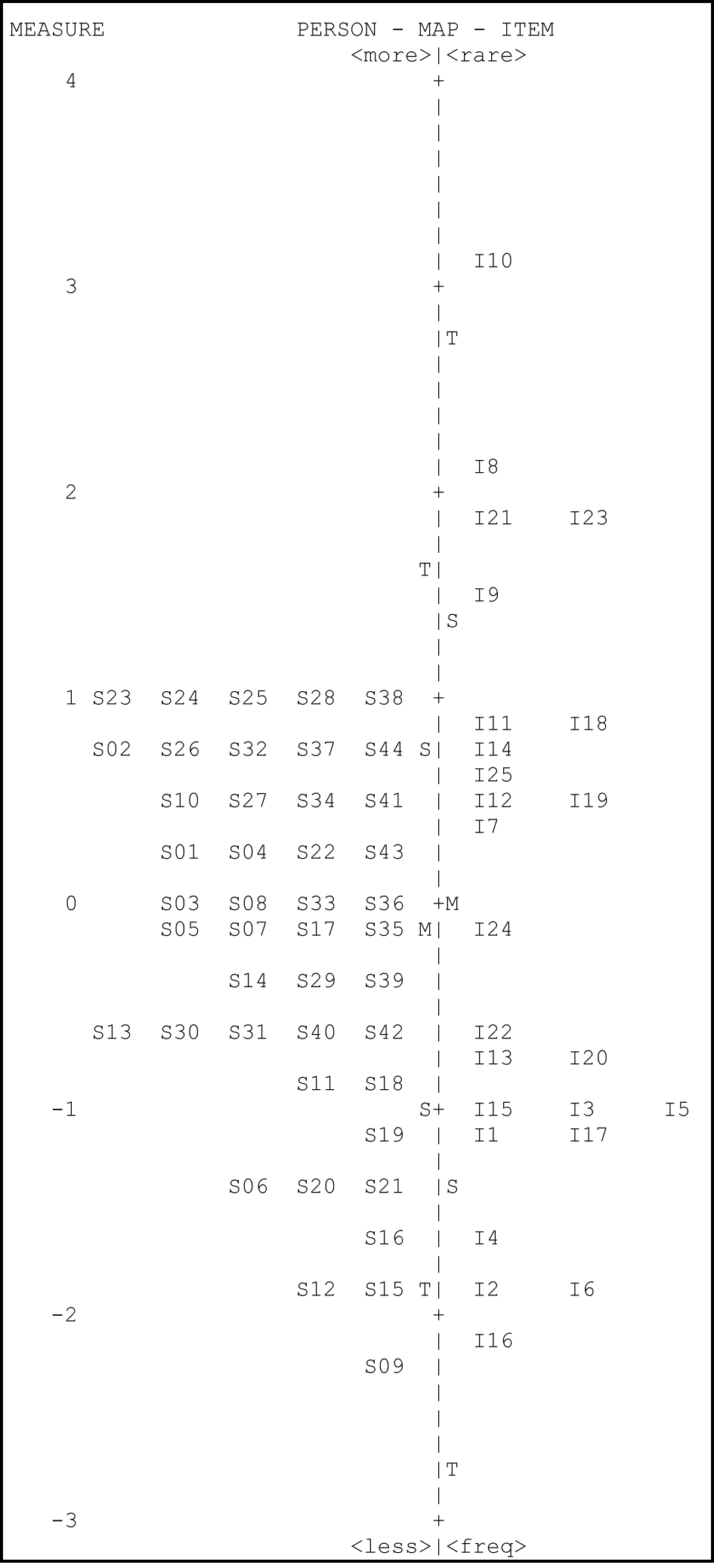

The Rasch model can be used to compare item difficulty and person ability by placing them on the same logit scale in the form of a vertical plot referred to as a Wright map. Figure 1 shows the Wright map for the RMCPI data.

Wright map of RMCPI data showing logit values for person ability and item difficulty. Note: The dashed vertical line separates the person ability data (left side) from the item difficulty data (right side).

The Wright map shows that the range of logit measures is from a low of −3 to a high of +4. This shows that the data is slightly skewed with respect to person ability. The test is difficult for the students since there are five items (8, 9, 10, 21 and 23) that are above the ability of the students. Item difficulties range from about −2.8 logits for the easiest item to about 3.2 logits for the most difficult item. There are some items with a similar difficulty level like items 3, 5 and 15. The items 8, 9, 10, 21 and 23 are not targeted well and hence the difficulty of these items was estimated with high imprecision.

Item fit

Model fit is evaluated using two residual analysis, infit (weighted) and outfit (unweighted) statistics and this helps in identifying problematic items. Table 1 shows the infit and outfit statistics for the RMCPI data.

Fit statistics for the RMCPI data.

| Item no. | Measure | SE | Infit MNSQ | Infit ZSTD | Outfit MNSQ | Outfit ZSTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 3.17 | 0.73 | 1.10 | 0.4 | 2.92 | 1.7 |

| 23 | 1.93 | 0.45 | 1.14 | 0.6 | 2.30 | 2.1 |

| 17 | −1.16 | 0.36 | 1.27 | 1.5 | 1.48 | 1.9 |

| 14 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 1.14 | 1.0 | 1.34 | 1.4 |

| 4 | −1.57 | 0.39 | 1.11 | 0.6 | 1.16 | 0.6 |

| 13 | −0.79 | 0.34 | 1.14 | 1.0 | 1.15 | 0.9 |

| 8 | 2.15 | 0.49 | 1.09 | 0.4 | 1.14 | 0.4 |

| 21 | 1.93 | 0.45 | .94 | −0.1 | 1.08 | 0.3 |

| 9 | 1.56 | 0.41 | 1.07 | 0.4 | 1.04 | 0.2 |

| 11 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 1.01 | 0.1 |

| 16 | −2.07 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.1 | 1.04 | 0.2 |

| 15 | −1.03 | 0.35 | 0.96 | −0.2 | 1.02 | 0.2 |

| 25 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.98 | −0.1 | 1.01 | 0.1 |

| 24 | −0.14 | 0.33 | 0.94 | −0.5 | 1.00 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.98 | −0.2 | 0.94 | −0.3 |

| 22 | −0.68 | 0.34 | 0.96 | −0.2 | 0.98 | 0.0 |

| 12 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.96 | −0.3 | 0.92 | −0.4 |

| 7 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.94 | −0.5 | 0.87 | −0.7 |

| 20 | −0.79 | 0.34 | 0.93 | −0.5 | 0.84 | −0.9 |

| 2 | −1.89 | 0.42 | 0.90 | −0.3 | 0.72 | −0.7 |

| 18 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.90 | −0.7 | 0.80 | −0.8 |

| 3 | −1.03 | 0.35 | 0.86 | −0.9 | 0.82 | −0.9 |

| 1 | −1.16 | 0.36 | 0.85 | −0.9 | 0.74 | −1.2 |

| 5 | −1.03 | 0.35 | 0.82 | −1.2 | 0.73 | −1.4 |

| 6 | −1.89 | 0.42 | 0.78 | −0.9 | 0.81 | −0.4 |

| M | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.99 | 0.0 | 1.11 | 0.1 |

| SD | 1.40 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.7 | 0.48 | 0.9 |

SE, Standard error; MNSQ, mean square value; ZSTD, standardized z-score.

The acceptable mean square (MNSQ) values for both infit and outfit statistics for a low stakes multiple-choice test is 0.70–1.30 (Bond & Fox, 2015). All the items have infit values which are within the acceptable range. Items 10, 23 and 17 have outfit values which are outside the acceptable range but since their infit values are well within the range, they are not considered to be problematic. The ZSTD data for both infit and outfit statistics for most items is within the acceptable range of −2.00 to +2.00 (Bond & Fox, 2015). This suggests that the items fit adequately to the dichotomous Rasch model.

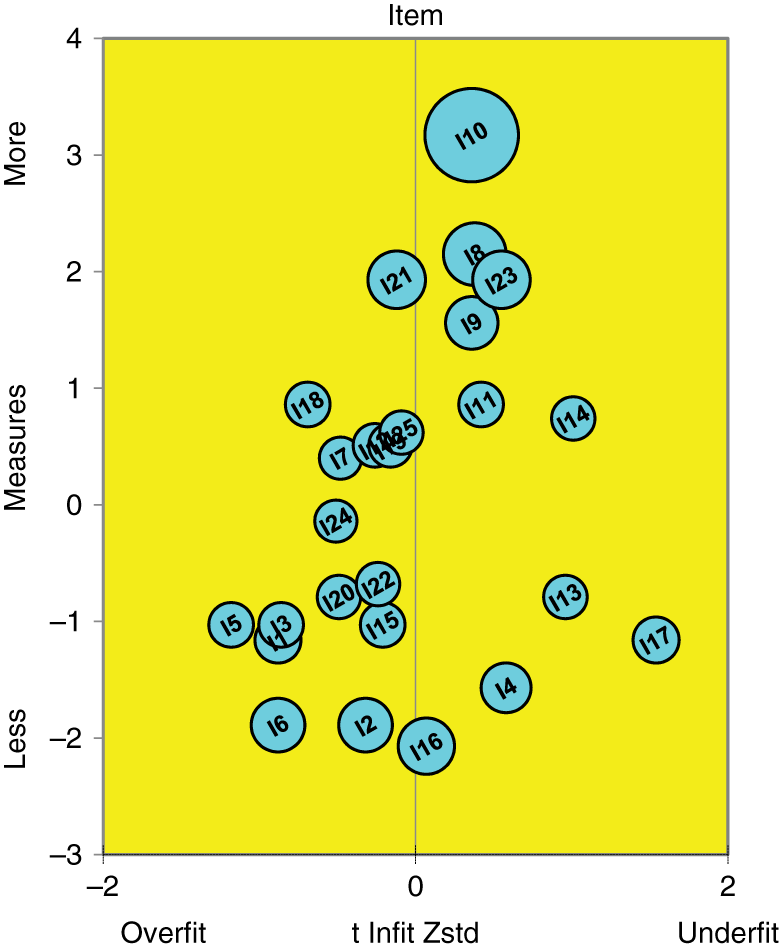

Item fit can also be analyzed by a bubble chart. Figure 2 shows the bubble chart for the RMCPI data. It can be seen from the bubble chart that most of the items function as expected according to Rasch model as they are within the quality control line of −2 to +2 (Bond & Fox, 2015).

Bubble chart for RMCPI items. Note: The bubble chart has item difficulty in logits on the y-axis and the standardized infit statistics on the x-axis. The bubbles represent the items.

Discussion

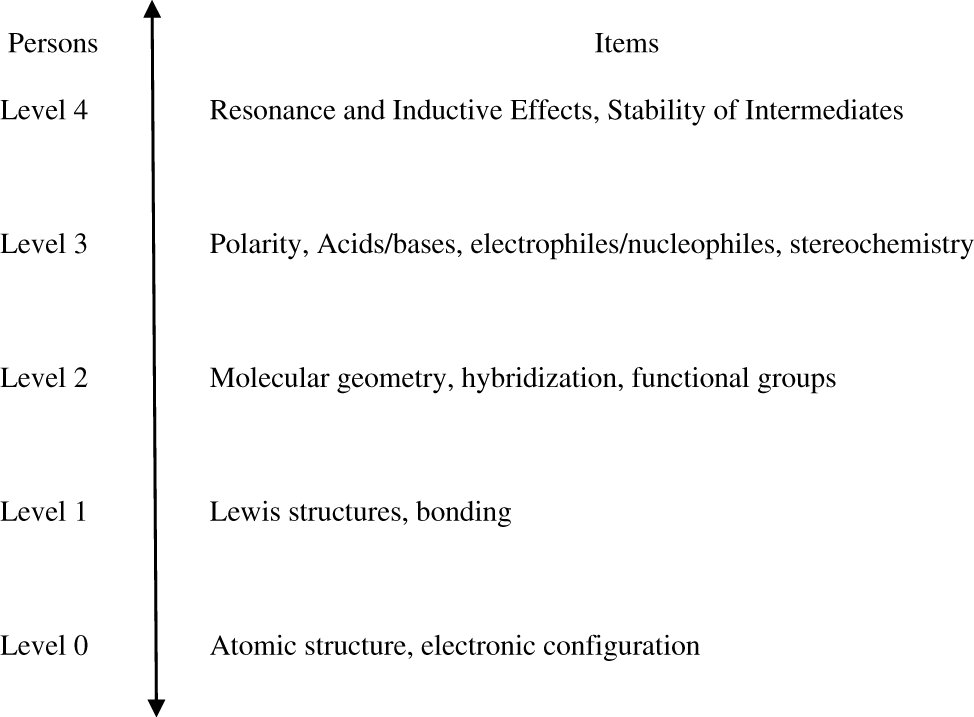

The PCA of the RMCPI data indicate that the instrument is unidimensional and this together with the fit statistics and the bubble chart indicate that the RMCPI data accurately fits the assumptions made by the dichotomous Rasch model. This suggests that there are no discrepancies between the observations and expectations for the RMCPI items. All items had good infit statistics which indicates good item functioning for students within the ability range of that item. These results, when compared to the theoretical construct map which is illustrated in Figure 3, establishes the construct validity of the RMCPI instrument. This suggests that the RMCPI instrument is measuring the unidimensional construct of students’ understanding of concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms.

Theoretical construct map for concepts related to RMCPI items. Note: The theoretical construct map shows the concepts related to RMCPI items ordered such that lower level concepts are fundamental concepts and higher level concepts are more advanced concepts.

The Wright map indicates that the test is difficult for the examinee population and the correlation between student ability and item difficulty is not adequate and the difficulty of items 8, 9, 10, 21 and 23 were estimated with high imprecision. Items 8, 9 and 10 are related to the concept of bonding which is a lower level concept that students learn in general chemistry. Additionally, a fundamental understanding of the concept of line drawings is also needed to answer item 10. These findings are consistent with previously reported results (Cooper, Grove, & Underwood, 2010) which indicate that students have difficulties with representational competence in chemistry. Items 21 and 23 are related to the concept of stability of intermediates and stereochemistry, respectively, which are higher order concepts that students traditionally find difficult in organic chemistry. One way to overcome this would be to increase the sample size in an attempt to see if these items are targeted well when more participants are recruited to represent a larger heterogeneous sample. Items 8, 9 and 10 may have to be modified to make them more explicit before collecting data on a larger sample. Items 21 and 23 may have to be eliminated because they are concepts that might not be introduced early on in the first semester of organic chemistry.

The development of a concept inventory is a multi-step, iterative process. Even after the alpha version of an inventory is finalized, the inventory may be subject to revisions based on data collected from additional institutions. Since the development of a concept inventory is an iterative process, further information regarding problematic items can be obtained by conducting additional interviews with students and by consulting the opinions of experts regarding the problematic items and the inventory as a whole. Rasch analysis can be used as one of the sources of information in this iterative process. The present manuscript is aimed at exhibiting the utility of Rasch analysis for obtaining information about items during the development phase of a concept inventory in chemical education where Rasch analysis is under-utilized.

The person separation reliability was not adequate and lower than the accepted value of 0.8 (Bond & Fox, 2015) and this indicates that there are problems with the consistency in the RMCPI items’ placement of students along the logit scale. This again could be due to the sample size and a larger sample size might help in overcoming this problem. This could additionally be attributed to the number of items in the inventory and having more items under each concept, might improve the person separation reliability. Additionally, interviews with students might also help give insight on whether students are actually using their conceptual knowledge to answer the questions (Wren & Barbera, 2013).

Limitations and future research directions

One of the limitations of the present study is the sample size and the generalizability of the sample. The sample is above the minimum sample size for dichotomous data which is 30. In order to increase the confidence interval from 95 % to 99 %, the minimum sample size needed would be 150 (Linacre, 1994). The other limitation of this study is that data was collected from only one university and therefore limited in its generalizability. Data will have to be collected from other universities to see if the items function well and if the results are reproducible (Barbera, 2013). A larger sample size would also be beneficial for measuring the item difficulty more precisely. Another limitation of this study is that the instrument contains only 25 items. More items could potentially help improve person separation reliability.

The RMCPI items will be modified based on the obtained results and more items will be added to the existing ones before collecting data on a larger sample. Classical test theory (CTT) will be utilized on this data to obtain the difficulty and discrimination and these results will be compared to the results obtained from Rasch analysis. The use of CTT and Rasch techniques will help add to the validity and reliability data for the RMCPI instrument. Rasch analysis helps assess properties beyond what CTT is capable of and this would contribute more to the psychometric properties of the instrument (Barbera, 2013). Distractor analysis will be used to test the quality of the distractors and remove under-utilized distractors.

Conclusion

Rasch analysis was utilized to establish the validity and reliability of the RMCPI instrument. The RMCPI items function well within the Rasch model and the unidimensionality of the instrument was established. This psychometric data is important while using the instrument because it establishes the fact that the instrument is measuring only the intended construct.

References

Arjoon, J. A., Xu, X., & Lewis, J. E. (2013). Understanding the state of the art for measurement in chemistry education research: Examining the psychometric evidence. Journal of Chemical Education, 90(5), 536–545.10.1021/ed3002013Search in Google Scholar

Bandalos, D. L. (2018). Measurement theory and applications for the social sciences. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barbera, J. (2013). A psychometric analysis of the chemical concepts inventory. Journal of Chemical Education, 90(5), 546–553.10.1021/ed3004353Search in Google Scholar

Bernholt, S., & Parchmann, I. (2011). Assessing the complexity of students’ knowledge in chemistry. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 12(2), 167–173.10.1039/C1RP90021HSearch in Google Scholar

Bhattacharyya, G. (2013). From source to sink: Mechanistic reasoning using the electron-pushing formalism. Journal of Chemical Education, 90(10), 1282–1289.10.1021/ed300765kSearch in Google Scholar

Bhattacharyya, G., & Bodner, G. M. (2005). “It Gets Me to the Product”: How students propose organic mechanisms. Journal of Chemical Education, 82(9), 1402.10.1021/ed082p1402Search in Google Scholar

Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2015). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. New York, NY: Routledge.10.4324/9781315814698Search in Google Scholar

Boone, W. J., & Scantlebury, K. (2006). The role of rasch analysis when conducting science education research utilizing multiple-choice tests. Science Education, 90(2), 253–269.10.1002/sce.20106Search in Google Scholar

Boone, W. J., Townsend, J. S., & Staver, J. (2011). Using Rasch theory to guide the practice of survey development and survey data analysis in science education and to inform science reform efforts: An exemplar utilizing STEBI self-efficacy data. Science Education, 95(2), 258–280.10.1002/sce.20413Search in Google Scholar

Brandriet, A. R., & Bretz, S. L. (2014). The development of the redox concept inventory as a measure of students’ symbolic and particulate Redox understandings and confidence. Journal of Chemical Education, 91(8), 1132–1144.10.1021/ed500051nSearch in Google Scholar

Bretz, S. L., & Murata Mayo, A. V. (2018). Development of the flame test concept inventory: Measuring student thinking about atomic emission. Journal of Chemical Education, 95(1), 17–27.10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00594Search in Google Scholar

Chu, H. E., Treagust, D. F., Yeo, S., & Zadnik, M. (2012). Evaluation of students’ understanding of thermal concepts in everyday contexts. International Journal of Science Education, 34(10), 1509–1534.10.1080/09500693.2012.657714Search in Google Scholar

Connor, M. C., & Shultz, G. V. (2018). Teaching assistants’ topic-specific pedagogical content knowledge in 1H NMR spectroscopy. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 19(3), 653–669.10.1039/C7RP00204ASearch in Google Scholar

Cooper, M. M., Grove, N., & Underwood, S. M. (2010). Lost in Lewis structures: An investigation of student difficulties in developing representational competence. Journal of Chemical Education, 87(8), 869–874.10.1021/ed900004ySearch in Google Scholar

Dick-Perez, M., Luxford, C. J., Windus, T. L., & Holme, T. (2016). A quantum chemistry concept inventory for physical chemistry classes. Journal of Chemical Education, 93(4), 605–612.10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00781Search in Google Scholar

Flynn, A. B., & Ogilvie, W. W. (2015). Mechanisms before reactions: A mechanistic approach to the organic chemistry curriculum based on patterns of electron flow. Journal of Chemical Education, 92(5), 803–810.10.1021/ed500284dSearch in Google Scholar

Grove, N. P., Cooper, M. M., & Cox, E. L. (2012). Does mechanistic thinking improve student success in organic chemistry? Journal of Chemical Education, 89(7), 850–853.10.1021/ed200394dSearch in Google Scholar

Grove, N. P., Cooper, M. M., & Rush, K. M. (2012). Decorating with arrows: Toward the development of representational competence in organic chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 89(7), 844–849.10.1021/ed2003934Search in Google Scholar

Hadenfeldt, J. C., Bernholt, S., Liu, X., Neumann, K., & Parchmann, I. (2013). Using ordered multiple-choice items to assess students’ understanding of the structure and composition of matter. Journal of Chemical Education, 90(12), 1602–1608.10.1021/ed3006192Search in Google Scholar

Hale, L. V. A., Lutter, J. C., & Shultz, G. V. (2016). The development of a tool for measuring graduate students’ topic specific pedagogical content knowledge of thin layer chromatography. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 17(4), 700–710.10.1039/C5RP00190KSearch in Google Scholar

Hambleton, R. K., & Jones, R. W. (1993). Comparison of classical test theory and item response theory and their applications to test development. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 12(3), 38–47.10.1111/j.1745-3992.1993.tb00543.xSearch in Google Scholar

Kamcharean, C., & Wattanakasiwich, P. (2016). Development and implication of a two-tier thermodynamic diagnostic test to survey students’ understanding in thermal physics. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education, 24(2), 14–36.Search in Google Scholar

Linacre, J. M. (1994). Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 7(4), 328–331.Search in Google Scholar

McClary, L. M., & Bretz, S. L. (2012). Development and assessment of a diagnostic tool to identify organic chemistry students’ alternative conceptions related to acid strength. International Journal of Science Education, 34(15), 2317–2341.10.1080/09500693.2012.684433Search in Google Scholar

Mulford, D. R., & Robinson, W. R. (2002). An inventory for alternate conceptions among first-semester general chemistry students. Journal of Chemical Education, 79(6), 739.10.1021/ed079p739Search in Google Scholar

Othman, J., Treagust, D. F., & Chandrasegaran, A. L. (2008). An investigation into the relationship between students’ conceptions of the particulate nature of matter and their understanding of chemical bonding. International Journal of Science Education, 30(11), 1531–1550.10.1080/09500690701459897Search in Google Scholar

Pentecost, T. C., & Barbera, J. (2013). Measuring learning gains in chemical education: A comparison of two methods. Journal of Chemical Education, 90(7), 839–845.10.1021/ed400018vSearch in Google Scholar

Prince, M., Vigeant, M., & Nottis, K. (2012). Development of the heat and energy concept inventory: Preliminary results on the prevalence and persistence of engineering students’ misconceptions. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(3), 412–438.10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.tb00056.xSearch in Google Scholar

Ryan, M. D., & Reid, S. A. (2016). Impact of the flipped classroom on student performance and retention: A parallel controlled study in general chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 93(1), 13–23.10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00717Search in Google Scholar

Sreenivasulu, B., & Subramaniam, R. (2013). University students’ understanding of chemical thermodynamics. International Journal of Science Education, 35(4), 601–635.10.1080/09500693.2012.683460Search in Google Scholar

Taskin, V., Bernholt, S., & Parchmann, I. (2015). An inventory for measuring student teachers’ knowledge of chemical representations: Design, validation, and psychometric analysis. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 16(3), 460–477.10.1039/C4RP00214HSearch in Google Scholar

Wei, S., Liu, X., Wang, Z., & Wang, X. (2012). Using Rasch measurement to develop a computer modeling-based instrument to assess students’ conceptual understanding of matter. Journal of Chemical Education, 89, 335–345.10.1021/ed100852tSearch in Google Scholar

Wren, D., & Barbera, J. (2013). Gathering evidence for validity during the design, development, and qualitative evaluation of Thermochemistry Concept Inventory items. Journal of Chemical Education, 90(12), 1590–1601.10.1021/ed400384gSearch in Google Scholar

Wren, D., & Barbera, J. (2014). Psychometric analysis of the thermochemistry concept inventory. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 15(3), 380–390.10.1039/C3RP00170ASearch in Google Scholar

Wright, B. D., & Masters, G. N. (1982). Rating scale analysis. Chicago, IL: MESA Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 IUPAC & De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms