Abstract

The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children is described and reflected in connections with modern education theories and approaches. The cognitive, psychomotor and affective outcomes were evaluated by (a) observation of the children in the laboratory and (b) individual interviews. Eight to ten y.o. children can be introduced into chemistry by quite complicated hands-on activity. The experiments should be quite bright, a little risky and employ different equipment. Such skills as dissolution, heating, weighting, grinding, filtering, boiling can be developed, at first – one at a time and then – in combinations. The initial instructions should be given in the way “do as I do”. Theoretical discussions should be restricted. In this age children do not ask questions “why” that makes inquiry-based learning impossible. Thus the main developmental purpose for this age should be maintaining interest to chemistry, developing observational and procedural skills and accumulating experience that would serve as groundwork for further studying chemistry.

Introduction

In 2013 Polytechnic Museum (Moscow) has launched an outreach program “Facets” where we organized practical sessions on chemistry for the children of 8–10 y.o. The program was commercial – the parents paid for the sessions. The idea of this program arose to meet the demand of parents to “make some chemistry with their children”. The program turned to be quite successful and popular and here we’d like to share our experience.

What to teach chemistry for?

When we launched the program, the only rationale for it was the demand of the parents. However they did not manage to explain why they wanted to teach their children chemistry and just expressed the expectation that it will be “interesting and useful”. The meaning of those words was a matter of our reflection. In literature we could find various ideas – to give or show fun (Haynes & Powell, 1976; Hill & Berger, 1989; Howard, Barnes, & Hollingsworth, 1989; Hufford, 1984; Tracy, Collins, & Langevin, 1995) or mystery (Bergmeier & Saunders, 1982); to develop curiosity or interest to chemistry (Keller, Paulson, & Benbow, 1990; Steffensky & Parchmann, 2007; Tracy et al., 1995; Waterman & Bilsing, 1983); to help to learn science or convey some chemical concepts (Howard et al., 1989; Jones & Monley, 1986; Keller et al., 1990; Steiner, 1984); to show its relevance to everyday life (Bergmeier & Saunders, 1982; Jones & Monley, 1986; Umland, 1985); to present chemistry as a science (Borer, 1977; Howard et al., 1989; Jones & Monley, 1986); to develop scientific or chemical skills (Bergmeier & Saunders, 1982; Mischnick, 2011; Umland, 1985); to encourage students to participate in scientific activities (Keller et al., 1990), etc. Very promising idea is the development of children-parents interaction (Keller et al., 1990; Koehler, Park, & Kaplan, 1999; O’Connor, 1960). Sometimes education for children was combined with education for teachers (Hufford, 1984; Mischnick, 2011; Steffensky & Parchmann, 2007; Umland, 1985).

However, the authors almost did not discuss whether they achieved the proclaimed goals and whether the early exposure to science contributes to child’s development. Basing on the literature cited above the following list of developmental outcomes could be offered:

positive attitudes towards science;

better understanding of the scientific concepts studied later in a formal way;

influencing the eventual development of scientific concepts;

development of scientific reasoning and thinking.

The idea of positive attitude seems conventional (at least if children are successful in performing given tasks), but its evidence is flimsy: tracing the references (Eshach & Fried, 2005) we did not come to origin source confirming it experimentally.

The ideas of “scientific reasoning” and “developing scientific thinking” seem controversial. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development age 8–10 corresponds to the beginning of the concrete operational stage (Nurrenbern, 2001). In this stage a person can do mental operations but only with real (concrete) objects, events, or situations. Herron (1975) noted that students can make observations and direct measurements but can-not make general conclusion (despite classification) and grasp concepts that are not connected with something visible (for example, a concept of acid as a substance that forms H+). So, actually children of this age are not ready for abstract theories that form science. Moreover, scientific thinking and even application of chemical concepts in real life requires profound level of domain-specific expertise (McNeill, Lizotte, Krajcik, & Marx, 2006; Ni, 1998; Tricot & Sweller, 2014) that children do not achieve (Klahr, Zimmerman, & Jirout, 2011; Zhilin & Tkachuk, 2013). On the other hand, 4–6 y.o. children put forward and test hypothesis and make causal inferences. Both of these skills are the basis of scientific thinking (Gopnik, 2012). However in terms of Perry Jr (1979) children are dualists, regarding all their hypotheses and inferences as “right” or “wrong” and not questioning their scopes, that is an essential part of science. Thinking circle (what is the problem – how I approach to it – I act – do I satisfy with result) is formed at six y.o. (Dejonckheere, Van De Keere, & Mestdagh, 2009). Source of knowledge (theory or evidence) is also distinguished by 6 y.o. children (Kuhn & Pearsall, 2000) along with development of its evaluation and basic understanding of experimentation (Piekny, Grube, & Maehler, 2014). The only feature of scientific thinking that emerges between 8 and 11 y.o. is controlling variables (“Can you find out whether X makes a difference in how far the ball rolls?”; Klahr et al., 2011) that requires direct instructions (Matlen & Klahr, 2013).

Thus at 8 y.o. low-order features of scientific thinking are emerged yet, whereas high-order features still can-not emerge. One obstacle is underdevelopment of formal operations (that hardly can be influenced) and the other – the lack of domain-specific expertise (that can be influenced).

Hence, teaching chemistry for 8–10 y.o. should be focused on gaining expertise in terms of Brooks and Shell (2006) (accumulating experience and making links between different concrete phenomena in long-term memory). It means the development of “eyes and hands” – observation and procedural skills, including their application in unknown situation. Curiosity and positive attitude to science also should be developed.

Assessment of success in teaching chemistry to 8–10 y.o. children

The other questions are “what to teach” (content) and “how to teach” (organization of activity). All over the world chemistry is taught for children from 12–15 y.o. (Risch, 2010) and the vast majority of the recommendations would be inadequate for 8–10 y.o. children due to different aims of teaching, psychological and physiological age features and very limited expertise of children. To answer these two questions we could have based on the reported successes and fails in teaching young children chemistry and conclude reasonable answers. However, it is quite difficult, because the concept “success” is complicated.

Abrahams and Millar (2008) offered to regard a practical work as successful if students actually do and learn what a teacher wants them to do and learn. But we can’t use this approach in commercial laboratory – parents pay for the development of their children, but not for fitting the teachers’ expectations. So we must regard the session successful if it has some learning outcomes for students. The most spread framework for the assessment of learning outcomes is Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, and Krathwohl’s (1956) taxonomy with numerous revisions – the latter conventional one is of Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). In some cases it is inadequate for teaching chemistry but it is the best what we have.

Bloom’s taxonomy divides learning outcomes into three domains (cognitive, psychomotor and affective) with different levels inside of each domain. The reporters that assessed the success of their programs dealt only with either low-order affective skills (receiving and responding) or low-order cognitive skills (remembering and understanding).

Children’s interest (affective domain) is the most widely discussed outcome. In terms of Bloom it becomes apparent in receiving and responding. The easiest way to assess them is to observe reaction of children: whether they do what a teacher expects (Jones & Monley, 1986; Powell, Bromund, Haynes, McElvany, & Pedersen, 1975), how enthusiastic they are (Borer, 1977), whether their reaction is favorable (Jones & Monley, 1986; Waterman & Bilsing, 1983), do they enjoyed the class (Howard et al., 1989). On these criteria the reported programs turned to be successful. However teachers’ observations are qualitative and notice only the outcomes of the most active children. Another way is to give written evaluation forms where children rate their activities (Haynes & Powell, 1976; Powell et al., 1975), however young children can be bored with written forms.

Steiner (1984), Keller et al. (1990), and Koehler et al. (1999) reported the willingness of children to continue their experiment at home. Undoubtedly “willing to do on one’s own” should be regarded as a success in affective domain, but it is not presented in Bloom’s taxonomy. Curiosity is also an important condition of learning (Litman, 2005) and should be developed within chemistry courses. However Bloom’s taxonomy doesn’t mention curiosity and, surprisingly, nobody of the reporters mentioned it. Demand from parents to continue (Borer, 1977; Steiner, 1984) is also a sign of success that lies apart of Bloom’s taxonomy.

Assessment of outcomes in cognitive domain is less evident. Hufford (1984), Howard et al. (1989), Keller et al. (1990), and Rowat, Hollar, Stone, and Rosenberg (2011) intended to develop various concepts (state of the matter, acidity, solubility, etc.), but didn’t provide evidence of their development. Steiner (1984) estimated the success in remembering by asking questions which should have been answered aloud (“What is everything made of?” – “Atoms!”). Umland (1985) provoked children to ask questions (with no criteria reported). However all these methods are relevant only to the most active children in the groups. Howard et al. (1989) analyzed students’ records to estimate using specific vocabulary and found that the students’ vocabulary “grown”.

Bloom’s taxonomy in psychomotor domain doesn’t include the skills for perception of experience (for example, as they are described by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) and thus seems to be inadequate for chemistry. The only authors who assessed these skills were Howard et al. (1989) who analyzed children’s records.

How to teach: organization of activity

First of all it is obvious from all the reports that hands-on activity is the most interesting for children. Survey of Powell et al. (1975) revealed that children of 9–12 y.o. did not want to sit passively watching someone else performing experiments. The gifted children of 8–11 y.o. liked to do their own experiments much more than the preset procedures (Howard et al., 1989). Hands-on activity is better than lectures because the attention span of children is short (Borer, 1977). Hart, Mulhall, Berry, Loughran, & Gunstone, 2000 object that laboratory achieves little meaningful learning, but this objection is relevant for older students. “The experiment should be simple and safe, illustrate important chemical principles, and be as visually and physically exciting as possible” (Howard et al., 1989). Trying to deliver knowledge and understanding one must take into account the claim that with a one-hour lesson only one or two major ideas can be treated successfully (Waterman & Bilsing, 1983).

All the reporters provided hands-on activities more or less strictly guided. It strongly coincides with arguments against minimal guidance that causes cognitive overload (Hodson 1996; Kirschner et al., 2006). So we decided to provide strong guidance trying sometimes to let the children reveal their spontaneous activity and to look what would happen.

We also avoided to sacrifice scientific accuracy to attraction (for example to call a burning of potassium chlorate:sugar mixture “The Atom Bomb” as Bergmeier and Saunders (1982) did) because it would form strongly resistant misconceptions (Chi, 2005; Nussbaum & Novik, 1982).

We decided to involve laboratory equipment and not to stick the household materials for the following reasons: (a) to use all the possibilities and features of our laboratory; (b) the reminiscences of the head of laboratory that in that age he would have been interested in working with complicated labware; (c) the observation of Mischnick (2011) that children were “proud to work in a real laboratory with a laboratory coat, gloves, and protecting goggles on, using professional glassware, pipettes, spatulas chemicals, etc.”

Thus we conducted sessions as strongly guided hands-on activity with interesting visible outcome and using real labware. We didn’t require recording the results except for some sessions when the children had to make a conclusion basing on the records (for example when they had to identify a substance among a set of investigates substances). We also did not raise discussions on theoretical questions. However we never oversimplified our explanations to avoid misconceptions.

What to teach: acquirable skills and concepts

The authors that tried to deliver theoretical concepts reported that children were successful in learning symbols of elements, but not ions (Powell et al., 1975), that is expectable for the stage of concrete operations. At this stage one should concentrate on the development of macroscopic level of chemical representation because digging into microscopic and symbolic level would overload the working memory (Johnstone, 2006).

A reasonable complexity of experiments that children can handle with is reported. Pupils of 9–12 y.o. successfully distinguished cations between six bottles (one type of cations in one bottle) immediately after experiments with analytical reactions. Distinguishing between six anions using records of a week and a half ago was more difficult but still successful. However the children even did not attempt to distinguish two cations in one bottle (Powell et al., 1975). They also could not handle with experiments of complicated logistics, which required dispensing of several solutions. The most obvious explanation is that the complexity of appropriate experiments is limited by their working memory (Reid, 2008). Distinguishing two cations can provoke split-attention effect (Yeung, Jin, & Sweller, 1988) causing its overload. Complicated logistics can produce the same result requiring to keep too many objects in working memory.

The majority of reporters did not evaluate the success of particular works. At the reports children rated as “super” the following activities: distillation of impure water; recording IR spectra and identifying substances; paper chromatography; polymers. Concerning “polymers” the authors note: “we suspect the raring was due to the excitement of the formation of the foam and nor to the more intellectually challenging work with starch and cellulose”. Thus many different laboratory works can be interesting for children if they are of reasonable complexity. Reports don’t allow to conclude any pattern, so it will be done in the present article.

Methodology

Participants

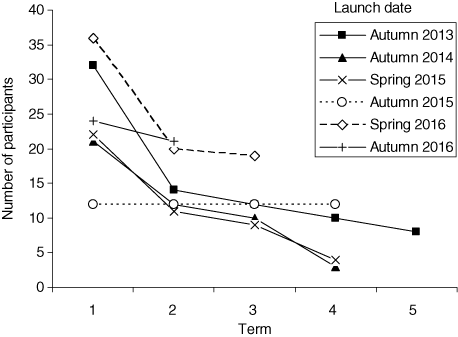

168 children participated the program (Figure 1), only 30 of them were girls. In 2013 we launched one group for 15 sessions and, later – two groups for 12 sessions. There was a strong parents’ demand to continue and we organized second-term course. At the same time two new groups (21 participants, three girls among them) were composed for 12-session first-term course, which was modified basing on feedback for 2013 first-term course. Later some children of those who passed the second-term course passed to the third-term and then – to the forth-term. For the initial group, that was launched in 2013 we even tried to organize the 5th term, however later we decided to restrict ourselves by four terms: we failed to invent the proper activities for five terms. Each time we modified the course basing on the feedback.

Number of participants.

The sessions were paid and the fee was relatively high. So, only motivated parents with above median income could afford it. It means that the sample of the participants is not representative.

Sessions

Herein we will discuss our experience for the first term, because now this course is quite well established.

The sessions took place on Saturdays or Sundays and lasted for 40–50 min, predominantly with hands-on activities. They were conducted in the laboratory equipped with chemical furniture, electricity and individual fume extractors.

The instructions were given in the way “do as I do” – the teacher explained what to do and showed how. The children followed instructions. Each step was quite simple – described with no more than 3–4 sentences. Usually the teacher asked the children what they observe or did they get what the teacher promised. When we wanted to make conclusions (for example, to make classifications or to choose the best way of making something) we discussed the observations.

To evaluate the sessions we have chosen the following data sources from the work of Bruce, Bruce, Conrad, & Huang, 1977: (a) observation in the laboratory and (b) interviews with children, focusing on their experiences and attitudes.

Observations

Observations were at each session either by a teacher who conducted the session itself, or by a dedicated person. The teacher recorded his observations immediately after each session. The “dedicated observer” made records during the session. The observers tracked (a) whether the children digressed from the process (if no, than the activity was successful); (b) whether they asked qualifying questions (if yes, than the instruction was confusing or caused cognitive overload); (c) whether they were keen to discuss observations (if yes, than the observations stimulated some mental processes); (d) whether they were looked satisfied. Recalls from the previous sessions were also recorded and sometimes provoked by questions.

Interviews

Interviews were taken in 2014 individually by a person who was not familiar to the children and who didn’t know anything about the particular sessions he asked about, but did know the material of the sessions and thus could understand the answers. Twelve children from the second-term group were asked to describe what had they remember from the previous term. It was the only question that was asked, with no prompts or qualifying questions. The answers were recorded and compared with the real content. Only three children were quite enthusiastic to talk a lot about their experience. The other regarded this interview as just a matter to shake off. Thus the main conclusions were based on the observations.

Ethical issues

The ethical issues were guided by national laws and ethical customs. They fully agree with BERA Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (2011). All the parents of the participants were aware beforehand that the program was new and experimental; that we should make notes on the results (not mentioning the names of the participants); that we could publish the results. The aim of the program was teaching the participants, and the presented research was just a by-product meaning that the interests of the children were primary. The participants could quit the program whenever they wanted. When the interviewed participants revealed discomfort the interview was stopped.

Results and discussion

Positive outcomes

Hands-on activity turned to be interesting and emotionally positive for children. Only one participant on one session demonstrated total absence of interest, playing his mobile phone. All the reminiscences of the children at the interview dealt with their activity – not theoretical ideas or personal relationships. The most memorable activities were making gunpowder by grinding the certain weights of sulfur, carbon and potassium nitrate (7 of 12 interviewed participants remembered that they made and burned gunpowder bud only two of them mentioned grinding), silvering a coin (4 of 12), manipulations with glass tubes (3 of 12) and pouring a melted metal into water (3 of 12).

Children easily follow instructions “do as I do” and develop manipulative skills very successfully. One session was enough to develop such skills as lighting gas burners, evaporation of water, measuring temperature by thermocouple, dissolution of substances, weighting etc. The exception was the heating of test-tubes: more than a half of the children repeated such mistakes as clutching a test-tube at the middle (not near the mouth), heating clutch along with a test-tube and so on. Thus if the children had performed some manipulation once we expected that they have remembered necessary procedures and just told them “do it” (“heat”, “weight”, etc.). This idea of scaffolding (McNeill et al. 2006) turned to be time-saving. At the second term they managed to obtain gases, mix them in the syringes and ignite gas mixtures; distillate water in an apparatus with two test-tubes; melt metals and make alloys. At the third term they made recrystallization of salts, synthesized and isolated insoluble salts by mixing solutions or pushing gas in solution. At the forth term the children could prepare solutions for oscillating reactions following written instructions. Thus this age is quite suitable for the development of complicated manipulative skills if the sequence of the skills fits the idea of scaffolding.

The observations clearly reveal that children and their parents can cope with a reasonable risk. Of course, they used laboratory coats, goggles and used fume extractors. However, some of the activities, while conducted in inappropriate way, could lead to finger burns or release of stinky gases. Children and parents were aware of it but agreed to these activities. The brightest example was the session “manipulations with glass tubes”. At the session about a half of the participants got finger burns, but it didn’t distract them from the process. Also when a teacher showed how to extinguish a candle fire by fingers the children observed it with caution until the bravest one tried to repeat. After that the majority of children also repeated this manipulation despite the teacher had not insisted on it.

Usually children performed activities following teacher’s instructions. However, after quite bright experiments (for example, burning of gunpowder) children asked “what will happen if we do something”. Usually we allowed children to answer their questions experimentally.

We can mark several extraneous factors (that don’t connect with the content) that increased children’s interest. The outcome of the experiment should be unexpected for children, meaning that while instructing a teacher should show all the necessary manipulations, but shouldn’t show the experiment itself. For example, when children obtained copper mirror reducing copper (II) chloride by hydrogen, they should have had to ignite released hydrogen which burned with blue flame. When children did it themselves, they were excited. When the teacher showed it to the other group, children were quite indifferent even when they ignited hydrogen themselves. It is also important for children that the experiment is successful. However to get maximal emotional outcome some experiments should be quite complex to be successful at the second attempt, not at the first. Changing activity in course of the session also benefits attention and attitude. Partly outdoor activities are very memorable. For example, at one of the sessions children prepared gunpowder in laboratory and then came outdoors to ignite it. In their reminiscences this activity was e mentioned by 7 of 12 of the interviewed children and all of them remembered that it ended outdoors. Moreover, before the next sessions some of them asked, whether they would come outdoors now. Various and quite difficult equipment also inspired enthusiasm. The most inspiring tool was a binocular – children looked through it for quite a long time, trying to look at different objects.

Corrected fails

Some of our activities initially failed. The children either distracted from the process or didn’t understand what to do. However we managed to correct these fails with subsequent groups. We’d mark out three reasons for the fails that could be corrected:

wrong sequence of topics, when the excellent performance requires too much skills or concepts that the children do not possess (in the terms of cognitive psychology according to Reid, 2008, the necessary chunks in the long-term memory are not formed);

relying on the concepts outside chemistry that children do not possess.

too vague instructions;

For example, in our initial program the session “The Surface of the Metals” was the forth. At this session the children observed the surface of metals, cleared the surface and covered one metal by another ending up by silvering a bronze coin. However the children often “hung” and made many mistakes. While analyzing the necessary and developing concepts we understood that we tried to explore the concept of the substitution that was not formed. Thus we changed the sequence of the sessions, putting forward the session “element” which clearly explains why one metal could be replaced with another.

The example of non-formed concept outside chemistry is a concept of ratio with an operation of division, which underlay the session “density”. Initially we suggested to weight a certain volume of a liquid and then to divide mass by volume. The children failed – they did not understand the sense of this operation. Then we compared weights of 1 mL of various liquids and connected it to a behavior of a piece of wood in the liquid. Then we put areometer into water, added salt and watched the scale. Thus we transferred from abstract operation of division to concrete observations that fit this age (Herron, 1975; Nurrenbern, 2001).

The example of the vague instructions was the synthesis of the plastic sulfur. There are two essential but subtle steps: heating sulfur to boiling and heating the walls of the test-tube to pour the boiling sulfur out. When we just explained it, the children didn’t heat neither sulfur nor the walls to a proper temperature. So it was that uncommon case where we showed the whole process with a result drawing a special attention to the appearance of boiling sulfur and the process of heating walls. The result was quite exciting for the children to repeat the experiment despite they knew its outcome.

Total fails

Some of our activities proved total failure that could not be corrected. We suggest that these activities either were too complicated or did not fit the age psychology.

For example, the following practical activities failed: making cuprammonium rayon (Knopp, 1997); soap boiling; measuring the mass portion of water in hydrous salts. The children also failed to determine the mass of a body “by sight”. We asked them to determine the mass “by sight”, write down their suggestion and compare it with the result of weighting. However they got confused in their own records. Virtually any activity that required making records was unsuccessful.

The students (even of the 4th term) refused to compose formulas basing on the valence of the elements. They also didn’t solve quantitative problems such as “how much sulfur should we take to react with one 1 g of copper when the equation is given”. Thus 8–10 y.o. is a wrong age to teach any qualitative ideas.

The children also didn’t support theoretical discussions, even the most primitive (e.g. classification of their observations). From a quarter to a half of children got bored after the first minute of discussion. They diverted their attention away, looked around, played with their mobile phones, chatted, etc., and returned to prescribe activity only when it was hands-on. In interviews children didn’t remember any theoretical ideas. It seems, that in this age they have better pictorial memory that at older age. As Zhilin (2014) has shown previously, symbolic level serves as a crutch to remember representations of chemical reactions for 15+ y.o. students, whereas 8–10 y.o. students recall pictorial description without employment of symbolic level that they don’t possess.

The question “what will happen if we do...” was the only type of questions they asked. They never asked “why”. It means that 8–10 y.o. children are not ready for inquiry-based learning, because asking “why” is essential for it.

The sequence of sessions

Until 2016 the sessions were organized into the consequent terms. However the children gradually withdrew (Figure 1) and at the 4th term we never got a full group. Thus we decided to change the sequence. We made the introductory series of 12 sessions for those who came to us for the first time and then several series of parallel sessions (“gases”, “metals”, “solutions” and “polymers and colloids”). The parallel series could be attended in any sequence; however the sequence of the sessions within a series is important.

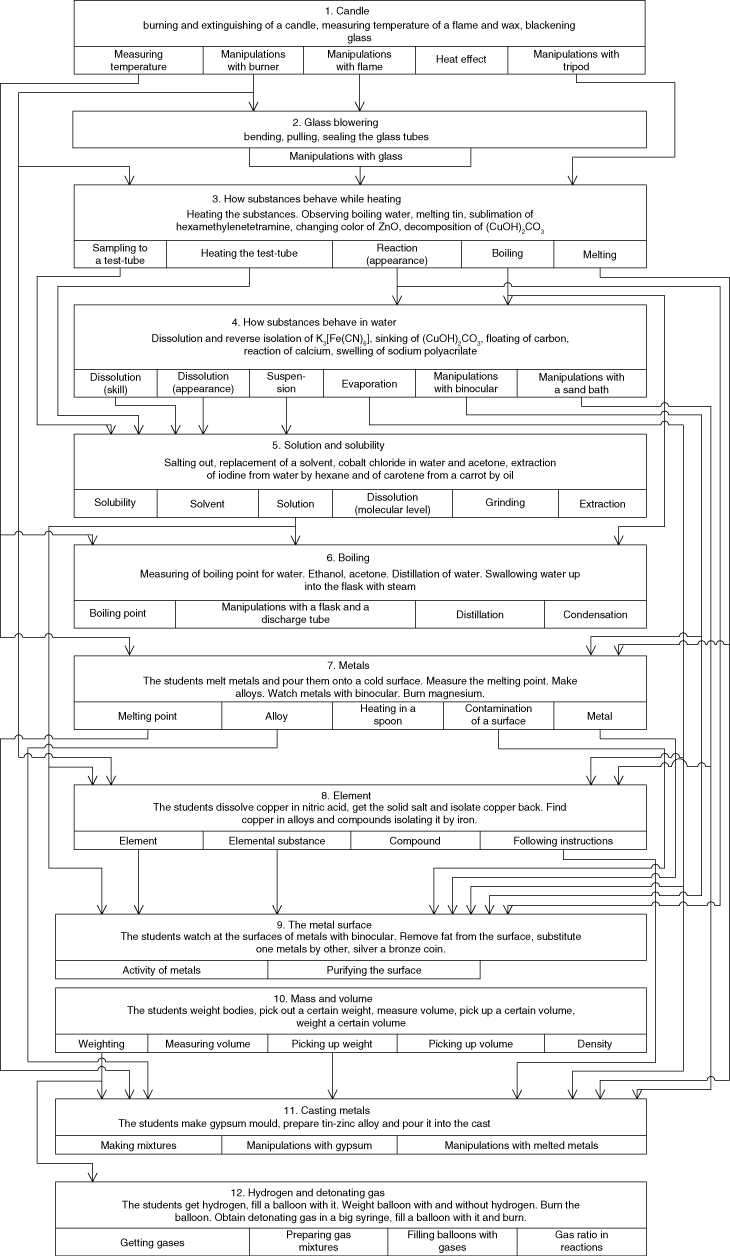

The first series was to develop all the skills that would be necessary in the parallel series. It was based on the sessions of the first term, but some sessions were added from the later terms. The sequence of the sessions within all the series fits the idea of scaffolding. One session develops some skills and concepts that are used in further sessions. The scheme of such a development is given at Figure 2.

The sequence of the sessions at the introductive series with the skills that are developed and then used.

The sequence of the introductory series was established since spring, 2016. Observations had shown that at all the sessions the children were addicted to the activity and asked very small number of qualifying questions. It means that these activities fit the abilities and interests of the participants. The children that continued the program performed at the second term all the necessary manipulations (dissolving, heating, weighting, grinding, collecting gases, making gas mixtures, etc.) without additional instructions and with no errors. They also recalled the reasons why they made a particular manipulation (for example, cleaned the surfaces or grinded solid components). Thus we can conclude that basic manipulative skills were developed successfully. At the second term the children also had no problems in noticing the features of the processes that they conducted. Thus observational skills were also developed.

Conclusions

It is possible to introduce 8–10 y.o. children into quite complicated chemical hands-on activity. To remain interesting the experiments should be quite bright, a little risky and employ different equipment. Such skills as dissolution, heating, weighting, grinding, filtering, boiling can be developed, at first – one at a time and then – in combinations. The initial instructions should be given in the way “do as I do”. When the necessary skills are already developed, it is enough to tell “do that”. Unexpectedness of the outcome and reasonable difficulties to achieve it are benefits. Theoretical discussions should be restricted to classification or new practical outcomes. In this age children do not ask questions “why” that makes inquiry-based learning impossible. Thus the main developmental purpose for this age should be maintaining interest to chemistry, developing observational and procedural skills and accumulating experience that would serve as groundwork for further studying chemistry.

The representativeness of this conclusion is limited to children whose parents are addicted to give them a good education. Its adequacy for other children was not investigated.

References

Abrahams, I., & Millar, R. (2008). Does practical work really work? A study of the effectiveness of practical work as a teaching and learning method in school science. International Journal of Science Education, 30(14), 1945–1969.10.1080/09500690701749305Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.Search in Google Scholar

Bergmeier, B. D., & Saunders, S. R. (1982). The chemistry magic and safety show. Journal of Chemical Education, 59(6), 529.10.1021/ed059p529Search in Google Scholar

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.Search in Google Scholar

Borer, L. (1977). Chemistry for elementary school children. Journal of Chemical Education, 54(11), 703.10.1021/ed054p703Search in Google Scholar

Brooks, D. W., & Shell, D. F. (2006). Working memory, motivation, and teacher-initiated learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15, 17–30.10.1007/s10956-006-0353-0Search in Google Scholar

Bruce, B. C., Bruce, S. P., Conrad, R. L., & Huang, H.-J. (1977). University science students as curriculum planners, teachers, and role models in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(1), 69–88.10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199701)34:1<69::AID-TEA6>3.0.CO;2-MSearch in Google Scholar

Chi, M. T. H. (2005). Commonsense conceptions of emergent processes: Why some misconceptions are robust. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(2), 161–199.10.1207/s15327809jls1402_1Search in Google Scholar

Dejonckheere, P. J. N., Van De Keere, K., & Mestdagh, N. (2009). Training the scientific thinking circle in pre- and primary school children. The Journal of Educational Research, 103(1), 1–16.10.1080/00220670903228595Search in Google Scholar

Eshach, H., & Fried, M. N. (2005). Should science be taught in early childhood? Journal of Science Education and Technology, 14(3), 315–336.10.1007/1-4020-4674-X_1Search in Google Scholar

Gopnik, A. (2012). Scientific thinking in young children: Theoretical advances, empirical research, and policy implications. Science, 337(6102), 1623–1627.10.1126/science.1223416Search in Google Scholar

Hart, C., Mulhall, P., Berry, A., Loughran, J., and Gunstone, R. (2000). What is the purpose of this experiment? Or can students learn something from doing experiments? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37(7), 655–675.10.1002/1098-2736(200009)37:7<655::AID-TEA3>3.0.CO;2-ESearch in Google Scholar

Haynes, W. L., & Powell, D. L. (1976). Kiddle Chem II. A course for children. Journal of Chemical Education, 53(11), 724–725.10.1021/ed053p724Search in Google Scholar

Herron, J. D. (1975). Piaget for Chemists. Journal of Chemical Education, 52, 146.10.1021/ed052p146Search in Google Scholar

Hill, A. E., & Berger, S. A. (1989). Adventures in chemistry for elementary and middle school. Journal of Chemical Education, 66(3), 230–231.10.1021/ed066p230Search in Google Scholar

Hodson, D. (1996). Laboratory work as scientific method: Three decades of confusion and distortion. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 28(2), 115–135.10.1080/0022027980280201Search in Google Scholar

Howard, R. E., Barnes, S., & Hollingsworth, P. (1989). Chemistry laboratory program for gifted elementary school children. Journal of Chemical Education, 66(6), 512–514.10.1021/ed066p512Search in Google Scholar

Hufford, K. D. (1984). Summer chemistry for fun. Journal of Chemical Education, 61(5), 427–428.10.1021/ed061p427Search in Google Scholar

Johnstone, A. H. (2006). Chemical education research in Glasgow in perspective. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 7(2), 49–63.10.1039/B5RP90021BSearch in Google Scholar

Jones, M. B., & Monley, R. (1986). College chemistry for kids. Journal of Chemical Education, 63(8), 698.10.1021/ed063p698.1Search in Google Scholar

Keller, P. B., Paulson, J. R., & Benbow, A. (1990). Kitchen chemistry. A PACTS workshop for economically disadvantaged parents and children. Journal of Chemical Education, 67(10), 892–895.10.1021/ed067p892Search in Google Scholar

Klahr, D., Zimmerman, C., & Jirout, J. (2011). Educational interventions to advance children’s scientific thinking. Science, 333, 971–975.10.1126/science.1204528Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Knopp, M. A. (1997). Rayon from dryer lint: A demonstration. Journal of Chemical Education, 74(4), 401.10.1021/ed074p401Search in Google Scholar

Koehler, B. G., Park, L. Y., & Kaplan, L. J. (1999). Science for kids outreach programs: College students teaching science to elementary school students and their parents. Journal of Chemical Education, 76(11), 1505–1509.10.1021/ed076p1505Search in Google Scholar

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1Search in Google Scholar

Kuhn, D., & Pearsall, S. (2000). Developmental origins of scientific thinking. Journal of Cognition and Development, 1(1), 113–129.10.1207/S15327647JCD0101N_11Search in Google Scholar

Litman, J. A. (2005). Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cognition and Emotion, 19(6), 793–814.10.1080/02699930541000101Search in Google Scholar

Matlen, B. J., & Klahr, D. (2013). Sequential effects of high and low instructional guidance on children’s acquisition of experimentation skills: Is it all in the timing? Instructional Science, 41(3), 621–634.10.1007/s11251-012-9248-zSearch in Google Scholar

McNeill, K. L., Lizotte, D. J., Krajcik, J., & Marx, R. W. (2006). Supporting students’ construction of scientific explanations by fading scaffolds in instructional materials. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15, 153–191.10.1207/s15327809jls1502_1Search in Google Scholar

Mischnick, P. (2011). Learning chemistry – the Agnes-Pockels-Student-Laboratory at the Technical University of Braunschweig, Germany. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 400, 1533–1535.10.1007/s00216-011-4914-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ni, Y. (1998). Cognitive structure, content knowledge, and classificatory reasoning. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159(3), 280–296.10.1080/00221329809596152Search in Google Scholar

Nurrenbern, S. (2001). Piaget’s theory of intellectual development revisited. Journal of Chemical Education, 78(8), 1107–1110.10.1021/ed078p1107.1Search in Google Scholar

Nussbaum, J. and Novik, S. (1982). Alternative frameworks, conceptual conflict and accommodation: Toward a principled teaching strategy. Instructional Science, 11(3), 183–200.10.1007/BF00414279Search in Google Scholar

O’Connor, R. (1960). Chemistry for parents and children. An experiment in community service. Journal of Chemical Education, 37(12), 639–640.10.1021/ed037p639Search in Google Scholar

Perry Jr, W. G. (1979). Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years: a scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.Search in Google Scholar

Piekny, J., Grube, D., & Maehler, C. (2014). The Development of experimentation and evidence evaluation skills at preschool age. International Journal of Science Education, 36(2), 334–354.10.1080/09500693.2013.776192Search in Google Scholar

Powell, D. R., Bromund, R. H., Haynes, L. W., McElvany, K. D., & Pedersen, J. D. (1975). Kiddie Chem. A course for children. Journal of Chemical Education, 52(11), 737–738.10.1021/ed052p737Search in Google Scholar

Reid, N. (2008). A scientific approach to the teaching of chemistry. What do we know about how students learn in the sciences, and how can we make our teaching match this to maximise performance? Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 9, 51–59.10.1039/B801297KSearch in Google Scholar

Risch, D. (Ed.). (2010). Teaching Chemistry around the World. Minster: Waxmann.Search in Google Scholar

Rowat, A. M., Hollar, K. A., Stone, H. A., & Rosenberg, D. (2011). The science of chocolate: Interactive activities on phase transitions, emulsification, and nucleation. Journal of Chemical Education, 88(1), 29–33.10.1021/ed100503pSearch in Google Scholar

Steffensky, M., & Parchmann, I. (2007). The project CHEMOL: Science education for children – Teacher education for students! Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 8(2), 120–129.10.1039/B6RP90025ASearch in Google Scholar

Steiner, R. (1984). Chemistry in the kindergarten classroom. Journal of Chemical Education, 61(11), 1013–1014.10.1021/ed061p1013Search in Google Scholar

Tracy, H. J., Collins, Ch., & Langevin, P. (1995). Chemistry abounds: An educational outreach program designed for elementary school audiences. Journal of Chemical Education, 72(12), 1111–1111.10.1021/ed072p1111Search in Google Scholar

Tricot, A., & Sweller, J. (2014). Domain-specific knowledge and why teaching generic skills does not work. Educational Psychology Review, 26(2), 265–283.10.1007/s10648-013-9243-1Search in Google Scholar

Umland, J. B. (1985). What do chemists do? A program for grades 1–3. Journal of Chemical Education, 62(2), 125–126.10.1021/ed062p125Search in Google Scholar

Waterman, E. L., & Bilsing, L. M. (1983). A unique demonstration show for the elementary classroom. Journal of Chemical Education, 60(5), 415–416.10.1021/ed060p415Search in Google Scholar

Yeung, A. S., Jin, P., & Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load and learner expertise: Split-attention and redundancy effects in reading with explanatory notes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23(1), 1–21.10.1006/ceps.1997.0951Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhilin, D. M. (2014). Representation of demonstrated reactions: imagery (macroscopic) or schematic (symbolic). Journal of Science Education, 15(1), 26–30.Search in Google Scholar

Zhilin, D., & Tkachuk, L. (2013). Chunking in chemistry. Eurasian Journal of Physics and Chemistry Education, 5(1), 39–56.10.51724/ijpce.v5i1.73Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 IUPAC & De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms