Abstract

The Context-Based Science Education (CBSE) approach promotes the inclusion of scientific concepts in everyday situations. In this work, we present a non-traditional context-based teaching experience on the subject of chemical senses that seeks, through a unique didactic instrument, to generate cognitive conflicts in order to promote conceptual change from “common sense” to science-based ideas. This experience encourages the active role of the students and involves simple experiences with everyday materials. It was carried out with 95 students from 12 to 15 years old. The contents developed during the experience were focused on taste and smell and the concepts of perception and sensation. The activities were designed to promote students’ self-awareness on their previous knowledge in order to achieve a sustainable learning by constructing appropriate scientific concepts. Assessment of students’ motivation for learning and their conceptual change – from common sense ideas to science based ideas – was done through an initial survey and a post-test. Students’ perception on their commitment and enjoyment about the approach has been evaluated through a metacognitive poll. The results show that the activities were highly motivating and that students were aware of their improvement in knowledge and their own commitment to the task throughout the entire experience.

Introduction

The Context-Based Science Education approach (CBSE) is a fruitful line of research that has emerged as a science teaching innovative approach (Bennet & Lubben, 2006; Bennett, Lubben, & Hogarth, 2007; Caamaño 2011; 2015; Gilbert, Bulte, & Pilot, 2011; Marchán & Sanmartí, 2015; Meroni, Copello, & Paredes, 2015; Nentwig & Demuth, 2007) and promotes teaching scientific concepts by adressing real problems from an interdisciplinary perspective.

One main goal in science teaching is to help students to overcome their intuitive conceptions, or “implicit theories” (Pozo & Gómez Crespo, 1998) due to their “common sense” (or intuitive cognitive functioning) applied to the prediction and control of everyday phenomena. Those naïf ideas are structured around very different principles from those of scientific theories (Gómez Crespo, Pozo, & Gutiérrez Julián, 2004). Many authors have made proposals to achieve a “conceptual change” (Glynn & Duit, 1995; , 2002; Pozo & Gómez Crespo, 1998; Rodríguez Moneo, 1999; Schnotz, Vosniadou, & Carretero, 1999) and some authors have made students be aware of cognitive conflicts about controversial information in order to achieve this conceptual change (Posner, Strike, Hewson, & Gertzog, 1982; 2003; Galagovsky, 2004a, 2004b; Vosniadou, 2007).

Another main goal of science teaching approaches is to highlight the importance of emotional and positive aspects in the learning process (Bennett et al., 2007; Carrió & Costa, 2017; Marbà & Márquez, 2010; Mellado et al., 2014; Mourtos, DeJong-Okamoto, & Rhee, 2004; Otero, 2006; Ramsden, 1997; Sanmartí & Marchán, 2015; Sanmartí, Burgoa, & Nuño, 2011). A pleasant environment in the classroom, together with the acknowledgement of students’ own interests and efforts tend to positively predispose them to enjoy further learning (Keller, 2010; Sanmartí & Marchán, 2015).

In this work, we have combined those ideas with the CBSE approach in the design of an innovative context-based teaching experience on the subject of chemical senses that poses situations of “common sense” to raise cognitive conflicts about controversial information, promotes the active role of the students and involves simple experiences with everyday materials.

The content of chemical senses was chosen because too much wrong information about them is being introduced in textbooks and online material. The naïf ideas that humans only have five senses or that there are specific areas in the tongue for each taste (commonly known as “Map of the tongue”) are often properly dealt with in biology or medicine advanced literature but not in secondary school materials. Furthermore, chemical senses, as a context-based issue, would allow teachers to introduce the first notions about chemical concepts such as solubility, volatility, ligand-receptor interaction, chemical equilibrium and some ideas on stereochemistry.

The teaching approach displayed in this article has been previously experienced with teachers in service. They have considered it an innovative and enjoying proposal to take to their own classrooms (Edelsztein & Galagovsky, 2019). Encouraged by this outcome, we decided to carry out this experience with students from the lowest years of secondary school (ages 12–15).

Objectives

The general aim of this work has been to analyze the improvement on science-based ideas and the engagement of 12–15 year- old students presented with an innovative didactic experience.

The specific objectives of this work are:

To introduce chemical concepts such as volatility, solubility, equilibrium, intermolecular forces, stereochemistry (recognition of different molecular shapes) in a simple and contextualized way, as a first approach, so that students could understand the chemical basis of the senses of taste and smell.

To promote students active learning to achieve individual conceptual change (Galagovsky, 2004a, 2004b; Posner et al., 1982; , 2003; Vosniadou, 2007) on the subject of chemical senses: from “common sense” ideas to a scientific view in context-based situations.

To evaluate students’ motivation for learning and their metacognitive perceptions about the teaching approach.

Theoretical framework

Activities were designed by recommendations of the Sustainable Conscious Cognitive Learning Model (MACCS) and its communicational derivations (Galagovsky, 2004a, 2004b).

This model proposes that cognitive change would arise when students become aware of their idiosyncratic mental representations and could compare them with others’. Understanding controversial ideas or argumentation promote cognitive conflicts within each student’s working memory. This awareness of the diversity of possible valid arguments will be a fundamental motivational factor: each student would want to know the appropriate scientific idea to solve his/her own cognitive conflict, i.e. this would trigger motivation for more learning.

To achieve the before mentioned goals, an appropriate didactic instrument should be developed. The aim of this instrument will be to reveal the specific prior ideas on the chosen topic and their supporting arguments in a relaxed and friendly class environment where the students are not afraid of making mistakes and the teacher encourages them to participate by justifying and discussing the reasons for their choices.

Therefore, an initial ad hoc instrument called Initial Survey (IS) was designed to reveal students’ common sense ideas and/or wrong previous learning (Edelsztein and Galagovsky 2019). This instrument posed circulating “common sense” ideas that exist in specific teacher oriented literature, didactic units and pedagogical contents related to the human senses and, in particular, to chemical senses. Main ideas presented in the Initial Survey would also be useful to assess students’ final conceptual change.

Students’ metacognitive self-assessment after the whole activity involved a previously standardized instrument that relates emoticons and words (Pérgola, 2014; Lerman 2003; 2005; Sánchez Díaz, Pérgola, Galagovsky, Di Fuccia, & Valente, 2018).

Methodology and description of each proposed activity

This activity was carried out with a total of 95 students from three different secondary schools of the City of Buenos Aires; two of them private and the other one of state management.

We worked with five different groups: (a) two groups of 12–13 years old students (currently in 1st year class), involving a total of 43 students (G1) and (b) three groups of 14–15 years old students (currently in their 3rd year), involving a total of 52 students (G2).

The G1 students had not had a prior approach to chemistry contents while the G2 students were taking Physical Chemistry for the first time simultaneously with this work.

The teaching approach consisted of five activities (Activity 1–5) that were carried out five times identically with the students of groups G1 and G2. These activities were distributed in six 80-min classes over 10 weeks. Students’ responses and final assessment are presented by age groups as percentages considering each whole population of G1 and G2, respectively.

Activity 1: resolution of an initial survey

Students were asked to answer a printed Initial Survey during the initial 15 min of the first meeting, to let their individual previous knowledge emerge and be registered. The Initial Survey consisted of five triggering sentences that comprised subjects on general senses, taste and smell.

Students were asked to select, for each sentence, all the options (out of five) that they assumed to be right to correctly complete that sentence. Table 1–Table 3 present those five triggering sentences with their respective five options as well as the percentages of choice selected by G1 and G2.

Triggering sentence 1 with its options and percentages of choice selected by G1 and G2, respectively.

| On general senses | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. Senses in human beings... | % G1 | % G2 |

| a) are five: touch, sight, hearing, smell and taste | 93 | 90 |

| b) perceive information from the world that is then interpreted by the brain | 33 | 60 |

| c) provide information from the world through specific sensory organs | 33 | 56 |

| d) are much less developed than in the rest of animals | 9 | 29 |

| e) function mediated by receptors that interact with molecules or ions | 0 | 15 |

Correct or partially correct answers are indicated in italics.

Triggering sentences 2 and 3 with its options and percentages of choice selected by G1 and G2, respectively.

| On taste | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2. Our ability to sense tastes... | % G1 | % G2 |

| a) is limited only to five basic types, including sweet and salty | 47 | 46 |

| b) depends on the temperature of the food we are consuming | 14 | 27 |

| c) depends on the presence of saliva in our mouth | 35 | 23 |

| d) depends on the tongue area. For example, the receptors for sweet taste are at the tip of the tongue and for the bitter taste at the back | 35 | 50 |

| e) is not modified by external factors. It is genetically determined | 19 | 12 |

| 3. Two people may have different sensitivities to the same taste because... | ||

| a) one has fewer taste buds than the other | 40 | 37 |

| b) one is older than the other | 26 | 21 |

| c) one does not produce as much saliva as the other | 26 | 23 |

| d) The statement is false. All individuals have the same sensitivity to tastes | 19 | 8 |

| e) previous experiences condition our perceptions | 28 | 50 |

Correct or partially correct answers are indicated in italics.

Triggering sentences 4 and 5 with its options and percentages of choice selected by G1 and G2, respectively.

| On smell | ||

|---|---|---|

| 4. When we have a cold it is difficult to distinguish the flavor of food because... | % G1 | % G2 |

| a) inflammation in the area of the nose inhibits the taste buds | 42 | 38 |

| b) the mucosa that surrounds the region of the brain responsible for perceiving flavors is inflamed | 40 | 17 |

| c) the inflammation of the nasal mucous membranes diminishes our sense of smell and, without it, the tongue can not sense tastes | 40 | 54 |

| d) the ability to perceive odors is partially reduced and without them it is very difficult to identify flavors | 19 | 48 |

| e) the mucus covers the taste buds and prevents the interaction of molecules and ions with taste receptors | 21 | 27 |

| 5. As soon as we enter a room with an intense aroma we can perceive it perfectly but after a while we stop doing it because ... | ||

| a) olfactory receptors are saturated with aromatic molecules and can no longer sense new molecules | 21 | 29 |

| b) after being exposed to a stimulus for a while, olfactory receptors do not continue reacting at the same initial velocity | 23 | 44 |

| c) we get used to the aroma and it is no longer new for our olfactory receptors | 81 | 71 |

| d) it allows us to ignore continuous redundant information | 12 | 12 |

| e) the smell dissipates around us and we stop detecting it | 21 | 15 |

Correct or partially correct answers are indicated in italics.

Hands-on experiments on human senses of taste and smell.

| Experiment | Instructions | Questions for discussion | Expected outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry tongue | Dry your tongue with clean paper napkins. Then, place a pinch of sugar over the dried area. Finally, swallow the sugar | Can you taste something at first? Where did you feel the sweet taste after swallowing? (Usually on the palate and the upper part of the throat that are moist) | Students verify that it is necessary for the sugar to be dissolved in the saliva so that it can be detected and they realize that there are taste buds not only in the tongue |

| Map of the tongue in doubt | Place a pinch of salt on the tip of the tongue. The tongue must be moist | Can you taste the salt with the tip of your tongue? (Usually they can, although according to the “map” that is the place where to taste sweet exclusively) | The participants verify that they are able to perceive salty taste even if the salt is on the tip of the tongue. They can verify that the map of the tonge is false |

| Counting taste buds | In pairs, swab the tip of your partner’s tongue with a small amount of blue food coloring so that taste buds become evident as pink bumps over a blue background. Then, place a cardboard with a standard punch hole (6 mm) over the colored area and take a picture. After counting the taste buds, switch roles | How many taste buds can you count? Do you all have the same number of taste buds? Why is it important to always count the taste buds in the same place on the tongue for all the participants? | Students compare the results and verify that the number of taste buds is variable between individuals |

| Pinched nose | Pinch your nose and eat a chewable candy without seeing the color of the wrapper | Can you guess the flavor of the candy? What does it taste like? Release your nose, can you guess the flavor now? | They verify that, without access to visual and olfactory information, it is possible to detect the sweet taste of the candy but it is very difficult to identify its flavor (strawberry, pineapple, mint, etc.) |

| Odor eraser | Beforehand, teacher should prepare two containers: (1) cinnamon and (2) a mixture of cinnamon and cocoa powder. Smell container 2 first. Then, for 5–10 s smell container 1 and, quickly, switch to container 2 again | According to the smell, what is there in container 1? And in container 2? Did the smell of container 1 change? What do you think there is in both containers? | Students verify that, thanks to olfactory adaptation, when they return to container 2, the aroma of the cinnamon is no longer perceived, allowing them to detect the aroma of the cocoa that has been previously “hidden”. If guided by the teacher, they should be able to identify how the containers were prepared |

| Olfactory confusion | Beforehand, teacher should fill 8–10 transparent bottles with water and a few drops of food essence and coloring. In some bottles, color and essence are “coherent” (i.e., red-strawberry, green-mint, yellow-lemon) but in others, they are “incoherent” (green-strawberry, pinneaple-yellow, etc.) | Can you guess the aroma by smelling the content of the bottles? (Usually, “coherent” bottles are quite easy to identifiy but it is really hard to assign the proper aroma to the “incoherent” ones) | By comparing the results, students are able to verify that previous experiences condition perception (for the combination red-lemon they usually assigned “grapefruit”, for example, probably because it is the citric fruit with the most similar colour) and that, when the visual and olfactory information do not match, it is very difficult to identify a smell |

Activity 2: acknowledgement of the diversity of choices

Once all the students completed the Initial Survey by selecting all the options that could properly complete each sentence (Table 1–Table 3), students had to become aware of the diversity of choices made by the group as a whole. To achieve this goal, the teacher read each question with its options and requested that those who had chosen each option raise their hands. A quick count generated students’ astonishment when they acknowledged the great variety of elections. Then, a brief justification of their choices was asked to those who had chosen, or not, each option. Thus, mental representations, ideas and/or previous learning were clearly put forward.

After this activity, all students of each group requested to know which was/were the correct option/s. This was a piece of evidence to illustrate their motivation to learn.

Activity 3: introduction of the scientific subjects with performance of simple hands-on experiments

After the exchange about the Initial Survey options selected by the students, the teacher provided information to start a discussion from each triggering sentence with scientific arguments that would sustain -or not- each option. The theoretical content was adapted to the level of each group.

Some of the theoretical contents were reinforced with hands-on experiments. Since these were simple and brief experiences (see Table 4), all participants had the opportunity to experiment with their own senses of taste and smell. This instance was highly attractive for students.

Main scientific issues that should have been learnt (from the Initial Survey and the experiments) and their corresponding Post-test sentences.

| Main scientific issue for each sentence of the Initial Survey | Related experiment | Post-test |

|---|---|---|

| 1a) Senses in human beings are five: touch, sight, hearing, smell and taste | – | a) The senses in human beings are five. [FALSE] |

| 1b) Senses in human beings perceive information from the outside world that is then interpreted by the brain | – | b) The brain senses the information received [FALSE] |

| 2c) Our ability to sense tastes depends on the presence of saliva in our mouth | Dry tongue | c) Without saliva we cannot sense tastes. [TRUE] |

| 2d) Our ability to sense tastes depends on the tongue area | Map of the tongue in doubt | d) Different parts of the tongue are capable of sensing specific tastes. [FALSE] |

| 3e) Two people may have different sensitivities to the same taste because previous experiences condition our perceptions | Olfactory confusion | e) The flavour perception is genetically dependant only on taste and smell. [FALSE] |

| 4d) When we have a cold it is difficult to distinguish the flavor of food because the ability to perceive odors is partially reduced | Covered nose | f) Without the sense of smell it is very difficult to identify the flavor of food. [TRUE] |

A scientific explanation for each sentence and their relationship with the hands- on experiment are further introduced in this work.

Altogether, this activity demanded two classes.

Activity 4: special project for students – an artistic video production

Once discussed the contents related to the chemical senses, both theoretically and experimentally, students were given, during the fourth class, the instructions for a special final project. The class was divided into groups of 4–5 people. They had to choose one out of eight possible given titles: Map of the tongue?, Olfactory adaptation, The five basic tastes, Taste buds, Perception vs. Sensation, Taste and flavor, The sense of taste and The sense of smell. They had to prepare a 3-min video accompanied by a written account of their outcome about the selected topic.

They were given a month to prepare their video and, after that time, each group presented its production to the rest of the class. After each presentation, students were encouraged to self-criticize their work and to express constructive opinions about the work of the other groups.

Students’ presentations and their discussions demanded two classes.

Activity 5: resolution of a post-test

Before the end of the last class, students were asked to briefly solve a Post-test (PT) in order to analyze if the main scientific ideas presented in the Initial Survey had been achieved throughout the activities. It consisted of six sentences to which they should assign the values of true or false. Table 5 shows the correlation between main scientific issues that should have been learnt from the Initial Survey, the performed experiments, and the Post-test sentences. Results are shown in Table 6 as percentages of correct answers achieved for G1 and G2, respectively.

Comparison between students’ previous knowledge and their conceptual change, considering main theoretical contents that had been taught.

| Main theoretical content evaluated (table with the answers that account for it in the IS) % IS (item #) | G1 % PT (item #) | % IS (item #) | G2 % PT (item #) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senses in human beings (Table 1) | 7 (1a) | 81 (a) | 10 (1a) | 89 (a) |

| Sensation versus perception (Table 1) | 67 (1b) | 30 (b) | 45 (1b) | 30 (b) |

| The need of saliva for sensing tastes (Table 2) | 35 (2c) | 40 (c) | 23 (2c) | 84 (c) |

| Distribution of taste receptors in the tongue (Table 2) | 65 (2d) | 81 (d) | 50 (2d) | 71 (d) |

| Previous experiences condition perception (Table 3) | 28 (3e) | 100 (e) | 50 (3e) | 64 (e) |

| Smell as an important input for perception of flavor (Table 3) | 19 (4d) | 79 (d) | 48 (4d) | 91 (d) |

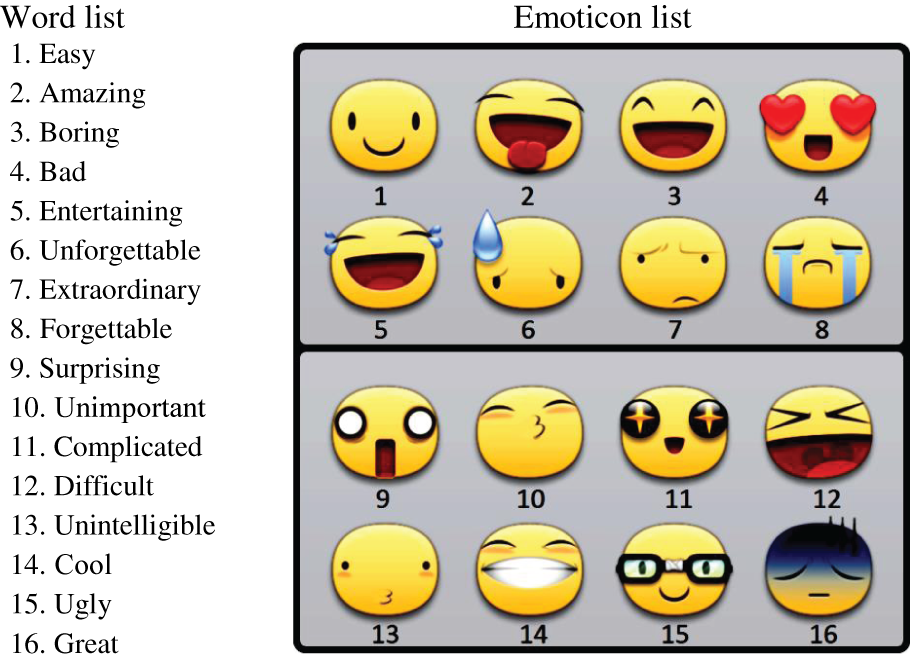

Classification for words and emoticons enlisted in Figure 1.

| # Word | # Emoticon | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 14, 16 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 14, 15 |

| Neutral | 1, 8, 10 | 13 |

| Negative | 3, 4, 11, 12, 13, 15 | 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 16 |

Results and discussion

Results obtained for the Initial Survey and the Post-test are shown below (Table 1–Table 3 and Table 6) along with a brief description of the theoretical content presented, the hands-on experiments (Table 4) and the discussion of the students’ answers.

Initial survey (IS)

The data collected from the Initial Survey are presented in Table 1–Table 3, expressed as percentages of choice by G1 and G2, respectively, for each option. The total sum of percentages of choice may exceed 100 % because participants could select more than one option. These figures are used for exclusively comparative purposes since their values are neither important nor generalizable to other populations, but pieces of evidence to analyze the development of students’ responses to the present approach.

Next, a brief description of scientific main issues involved in sentences of Table 1–Table 3 will be presented along with the corresponding discussion of the students’ answers.

The only correct option for this sentence is 1c. The senses, depending on their modality, are adapted to respond to the stimuli that occur in the environment thanks to specialized cells that are activated against a certain type of interaction (Foley & Matlin, 2010; Proctor & Proctor, 2006). This answer is correct but strictly incomplete because stimuli do not come only from the external world but also from the internal environment. Although 33 % of G1 and 56 % of G2 correctly chose this option, when carrying out the oral discussion it was evident that practically none of them knew that the information could also come from within their own body.

Option 1a is incorrect because, although smell, taste, touch, sight and hearing are the five traditional senses, today there is broad consensus that humans have many more, including thermoception, nociception, proprioception and equilibrium (Proske & Gandevia, 2012; , 2001). Unfortunately this information, which is well known in academic and medical fields, is not yet installed among teachers and continues to erroneously appear in school textbooks. An overwhelming majority of students chose option 1a as the correct one (93 % G1 and 90 % G2).

Option 1b is also incorrect because, though in colloquial terms, perception can be used as a synonym to sensation, both processes are physiologically different. While the sensory process receives simple isolated physical stimuli from the environment or the body itself, the perceptual process is an interpretation of that information provided by the sensory process. Thus, our senses do not perceive information but rather sense the stimuli (Foley & Matlin, 2010; Proctor & Proctor, 2006). Discussion with the students showed that the 33 % of G1 and 60 % of G2 who selected this option did not acknowledge a difference between these two meanings.

Option 1d is too general: it is not possible to assert that human beings have more or less developed senses than the rest of animals. It is not even possible to say that they are the same senses (Drake, 2011; Enjin et al., 2016; Wu & Dickman, 2012). Nine percent of G1 and 29 % of G2 % indicated this option as correct and their explanation was limited to the sense of smell in cats or dogs and the sight of some birds.

Regarding option 1e, among all the senses, only smell and taste are stimulated by the presence of chemical substances – molecules or ions – that interact with sensory cells (chemoreceptors). That is why they are often referred to as chemical senses (Buck, 2000a,Buck). Only 15 % of G2 and none of the students of G1 indicated this option but, during the oral discussion, it was clear that it was not because students knew that it was incorrect to generalize all sensory processes to interactions between ligands and receptors, but because they had not fully understood the sentence.

Table 1 also shows that older students (G2) felt more comfortable when choosing more than one option compared to G1.

When presented the theoretical content to the students, it was emphasized that many senses existed, beyond the five traditionally considered ones and, especially, that the chemical senses are the only ones mediated by chemoreceptors. This led to work on the concept of ligand-receptor interaction, i.e. the binding of a signaling molecule to its receiving macromolecule, as well as an introductory presentation of intermolecular forces. It was pointed out that receptors and ligands come in many forms, but they all have in common that the receptor is capable of recognizing just one (or a few) specific ligands, and a ligand is capable of binding to just one (or a few) target receptors. It was also highlighted that the binding of a ligand to a receptor changes its shape or activity, allowing it to transmit a signal or directly produce a change inside of the cell.

This idea was further explored in the theoretical discussion about the senses of taste and smell to introduce basic ideas about stereochemistry.

Regarding sentence 2, options 2a, 2b and 2c are correct. For sentence 3, options 3a, 3b, 3c and 3e are correct.

The human sense of taste is focused in the tongue, where the majority of the taste buds are located – although there are also taste receptors on the palate, the cheeks, the upper part of the throat and the epiglottis. Adults have between 2000 and 4000 taste buds and their distribution depends on each individual (Arvidson, 1979). While the ability to sense tastes is determined, in part, genetically, numerous non-genetic factors such as temperature (Verhagen & Engelen, 2006), saliva production (Matsuo, 2000), age (Mojet, Christ-Hazelhof, & Heidema, 2001; Stevens, Bartoshuk, & Cain, 1984), previous experiences (Small & Prescott, 2005) and non-sensory contextual factors have an impact (Duffy & Bartoshuk, 2000; Reed, 2008).

Human beings have specific receptors for only five basic tastes, that is, they do not result from the combination of others: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and umami (Chandrashekar, Hoon, Ryba, & Zuker, 2006; Ikeda, 2002). Less than half of the participants chose this option in both groups (2a, 47 % G1 and 46 % G2). During Activity 2, those who had not chosen it explained that, in their opinion, humans can sense much more than five tastes. This explanation may be due to the misconception of considering taste and flavor synonyms. (Rozin, 1982). Flavor is a more complex concept that results from different afferents including taste, smell and somatosensory fibers (Small & Prescott, 2005).

Options 2d and 2e are not correct although 2d was particularly highly selected. There is a very popular false belief that each basic taste is sensed in a different section of the tongue, a representation known as “map of the tongue”. Although the idea has been widely refuted, (Collings, 1974), 35 % of G1 and 50 % of G2 chose this option. These results could be due to the fact that it is still present in textbooks and through schooling progress, students would reinforce the misconceptions.

The discussion about these contents was complemented by three hands-on experiments: Dry tongue, Map of the tongue in doubt and Counting taste buds (Table 4).

During the theoretical discussion of these contents, the five basic tastes and representative ions and molecules capable of interacting with their specific receptors were presented. The existence of two different types of receptors was mentioned: ionotropic (for salty and acidic taste, i.e. Na+ or H+ and G protein-coupled receptors for bitter, sweet and umami tastes.

In the case of G2 students, as for the sweet taste receptor, the structure of different sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose) was shown and from the values of its sweetening power, it was discussed how the shape of the molecule influences its interaction with the receptor (how it “fits”). The structures of some commonly used sugar substitutes (Aspartame, Acesulfame, etc.) were also shown.

The concept of solubility was explained based on the “Dry tongue” experiment; it is observed that for taste receptors to sense molecules or sapid ions they must be dissolved. We delved into this topic with different mental experiments (for example, what would happen if our saliva was not composed mostly of water but by other types of solvents? Could we sense all tastes in the same way? What do you think would change?).

Regarding sentence 4, only option 4d is correct. The functioning of the olfactory sensoperceptive process is complex in humans (Buck 2000a; 2000b; Firestein, 2001; Su, Menuz, & Carlson, 2009). Olfactory information is key when it comes to identifying flavor (Rozin, 1982). If the smell is absent, due to some physiological problem or a cold, we are not able to perceive the differential aroma that characterizes each food although we can still identify the basic tastes and other somatic sensations. It is necessary to know the difference between the concepts of flavor and taste. Clearly, this was not the case for G1 students since option 4d was the least chosen (19 %).

For sentence 5, options 5b and 5d are correct. After being a long time exposed to a stimulus, the senses of taste and smell decrease and the receptors do not continue to react at the same initial speed even when the stimulus retains its intensity. This reduction of the response to a constant and uniform stimulus is called adaptation and is believed to be an important functional mechanism that prevents excess neuronal activity and it allows us to remain alert and to obtain new information (Köster & de Wijk, 1991). Students’ prevalent choice was that common sense idea about “getting used to” aromas, without any real understanding of what that means (option 5c, 81 % G1 and 71 % G2).

To broaden these explanations, three hands-on experiments were carried out: Pinched nose, Odor Eraser and Olfactory confusion, detailed in Table 4.

When it came to the theoretical discussion of the sense of smell, the concept of ligand-receptor interaction was retaken, but in this case, to deepen the notion of chemical equilibrium as a dynamic process in which the ligands are not “fixed” to the receptor but a permanent exchange takes place. Therefore, we emphasized that the concept of saturation (that can be further related to enzymatic dinamics) does not refer to a static situation; the sensorial process continues and what is modified is the transmission of the nervous impulse (its velocity or its intensity) once this sensing has taken place.

The concept of volatility was also presented. The amount of volatile compounds was related to the temperature at which food is served (for example, when comparing the flavor of hot and cold meat). In the case of G2 students, the chemical structures of compounds such as limonene were shown for an incipient analysis of intermolecular forces and its relation to vapour pressure of a given substance.

Post-test (PT)

The Post-test was taken after completion of Activity 4. It consisted of six sentences to which students should assign the values of true or false. These sentences are presented in the right column of Table 5 as well as their direct correlation with the ones that had been presented in the Initial Survey and with the contents related to the hands-on experiments.

Table 6 shows the comparative results of percentage of correct answers between the Initial Survey (equivalent to a pre-test) and the Post-test for G1 and G2, respectively.

While percentages are simply for comparative purposes, it is notorious that most of the concepts explained and experienced during the classes were incorporated, specially items a, d, e and f, by G1, and a, c, d and e by G2 students.

It is striking that G1 and G2 got only 30 % of FALSE answer in item b. This result may be driven from imprecision in sentence b of the Post-test. Indeed, the brain is the organ that centralizes and processes all the information coming either from external or internal stimuli. However, during classes, a semantic difference was given between the verb “sense” and “perceive”. Results may indicate that students did not understand those differences. Anyway, the fact that 70 % would have qualified sentence (b) as true still should be considered a progress on knowledge because of a previous frequent misunderstanding, as emerged during the theoretical explanation, which did not correlate with the functioning of sensorial organs with the brain.

Another interesting result is that only 40 % of G1 students responded properly about the need of saliva to sense taste. This could be due to the fact that these students do not yet handle concepts such as dissolution, molecules and ions, necessary to understand the phenomenon in depth. So, despite having conducted an experiment on the subject, most students have failed to give it the appropriate meaning.

Analysis of the teaching strategy

Results from the teaching strategy will be discussed from three points of view in order to assess the success of the whole experience:

Strategies developed to promote students’ motivation for learning

On the initial survey

As shown in Table 1–Table 3, a good dispersion of percentages was registered in the choice of the options proposed for each triggering sentence. Success achieved in the Initial Survey design is highlighted by two reasons:

Diversity in the answers. Every option was chosen for each question at least by 8 % of the students. This outcome shows that options indeed expressed ideas already established in the minds of the participants.

Multiple choices to select. The possibility of choosing more than one correct option for each question, challenged the strongly rooted ideas of the participants that “a single correct answer must be found”. This possibility was novel and, also, an opportunity to achieve a relaxed class environment, with a more playful approach where there was room for doubts and promotion of the awareness of what they already knew or believed. This device does support a comfortable way to promote conceptual change.

On the motivational aspects

During the development of the experience, it was possible to distinguish three clear moments of motivation:

The group discussion. The moment of sharing answers, after solving the surveys individually, was particularly mobilizing for the students: the evidence of the diversity of mental representations, opinions, knowledge and alternative arguments that operated in the participants was always surprising. Thus, although each individual was convinced that he or she had chosen the correct option(s), the diverse arguments and explanations of the other participants were also acceptable or possible. With interest and, occasionally, a hint of frustration, at the end of the group discussion of each item, the question inevitably arose: “So, what is the correct answer?” This motivation to receive more information, laid the foundation for the teacher to provide the necessary scientific data and/or propose a relevant experiment.

The students demand to know the correct answer. A relaxed atmosphere opened the possibility for the students to give their opinions without being labeled as shameful mistakes, without condemnation for being wrong or not knowing the answer, without pressure to guess the options, and to learn from “constructive errors” (Galagovsky, 2011). That is, the security in the response chosen by each individual was confronted permanently by the evidence of the wide variety of other choices. Thus, motivating cognitive conflicts emerged, being the participants themselves who demanded the teacher to satisfy their concerns to understand what would be the correct options and to understand the basis of the results of each experience. In conclusion, the function of cognitive conflict as a didactic device revealed its importance, both in its cognitive and communicational impact phase.

The hands on experiments. The attractive experimentation with their senses of taste and smell was always challenging and motivating.

Evidence of conceptual change and science-based ideas learning impact

Great cognitive advance could be perceived repeatedly after the discussion of each triggering sentence without the need of a formal evaluation. Students were aware of the adequacy or not of their ideas and previous knowledge, of their prejudices and how they had to modify them to correctly support concepts, to build their new knowledge. Some students could clearly express their astonishment at the arguments of other participants. The teacher took advantage and reinforced those moments, knowing that strong idiosyncratic mental representations act, very frequently, as obstacles in communication and/or learning (Garófalo, 2010). The possibility of “making mistakes” could be experienced as a stage of positive emotion, to be able to self-regulate and self-question, in opposition to the traditional negative sensation coming from an “external assessment”.

Furthermore, Post-test results show that many of the main scientific issues could be achieved.

Students’ metacognitive perceptions about their own learning processes

Immediately after completing the Post-test, students were asked to fill an anonymous written poll about their metacognitive perceptions on the whole experience in order to know their degree of self-commitment and their feelings towards the teaching approach. They were asked to choose from a list of words and emoticons those that best fitted their emotions during the activities considering what they had learnt, the experiments, the contents and the special project (artistic production) (Pérgola, 2014; Hugo, 2012; Sánchez Díaz et al., 2018).

The lists of words and emoticons are shown in Figure 1. This is a worthy instrument to evaluate students’ commitment because each number in the word list does not correlate with the number of an emoticon with the similar meaning.

List of words and emoticons given to the students to self-evaluation and assessment after the didactic approach, considering the following items: “what you have learnt”, “the experiments”, “the theoretical explanation‟, “the special project” and “what you remember now”.

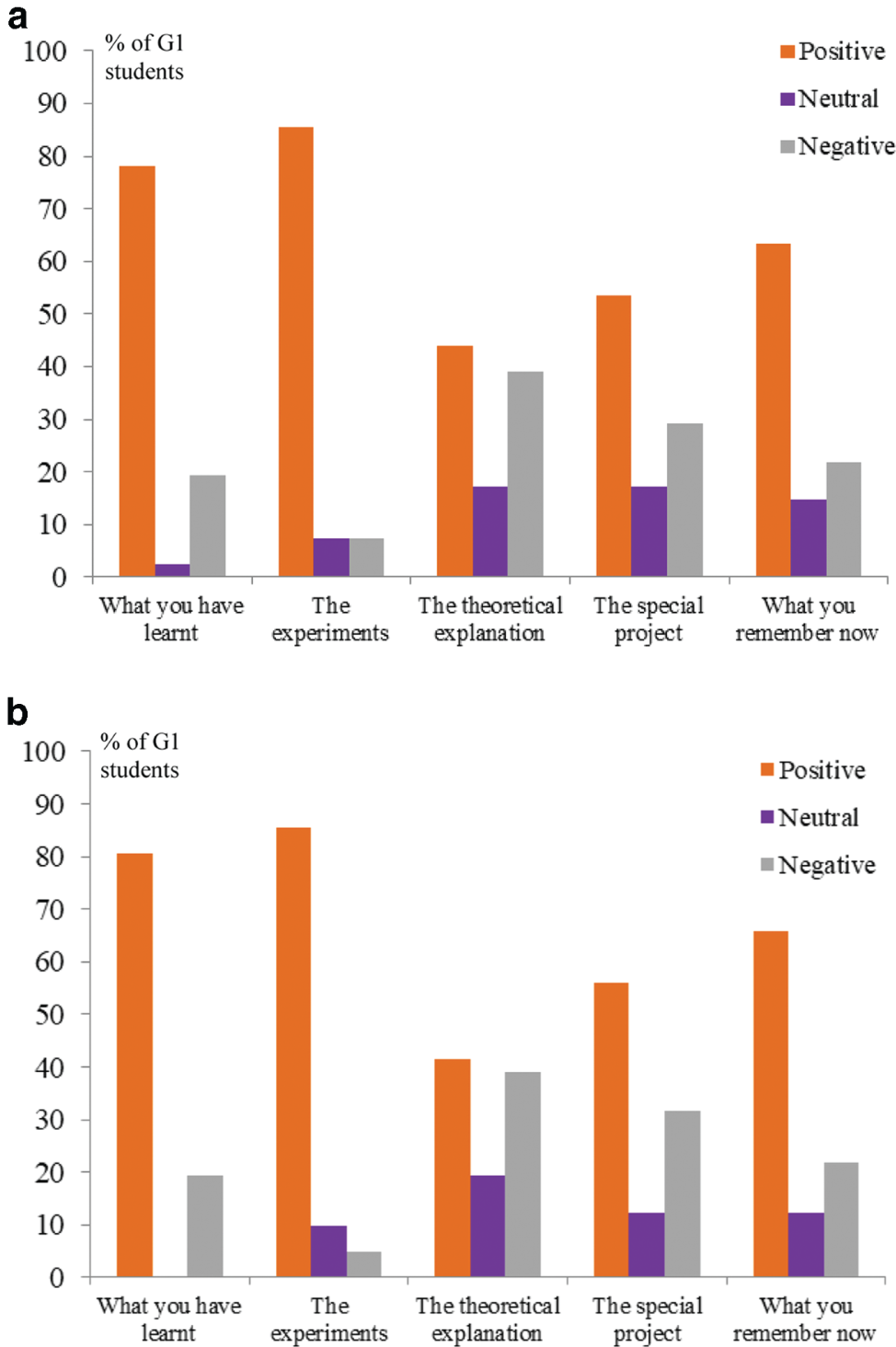

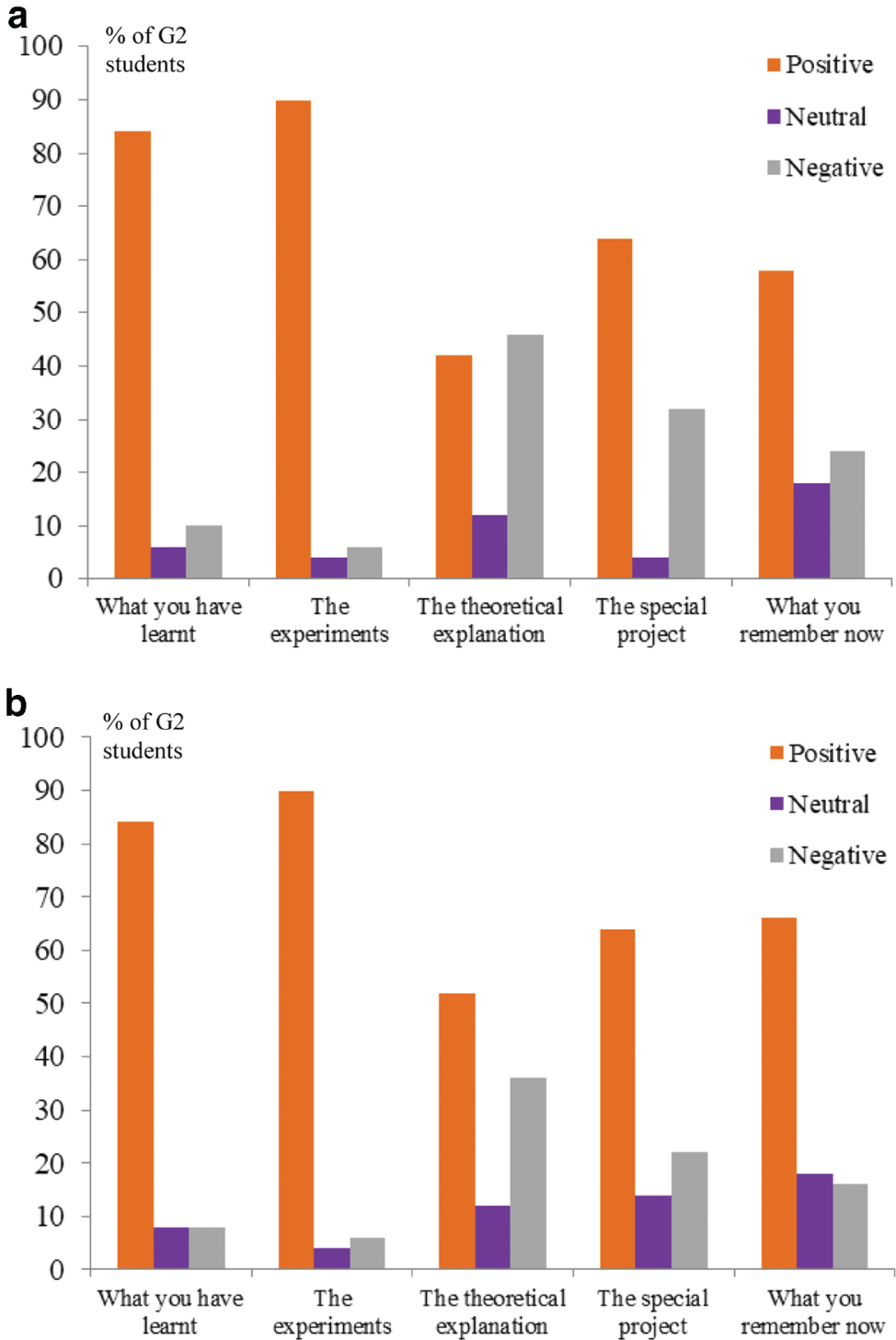

Table 7 shows a classification of those words and emoticons as positive, neutral or negative. This classification was known by the authors but not by the students. G1 and G2 choices of words and emoticons are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

G1 students’ opinions about the experience expressed (a) with words; (b) with emoticons.

G2 students’ opinions about the experience expressed (a) with words; (b) with emoticons.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the results from the polls separated by age groups (G1 and G2). In all cases, a very positive assessment of the experience was verified. The results from emoticons or words did not show major differences between them, which confirms that students made a committed selection and not a random one.

Comparison between G1 and G2 responses (Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively) show impressive similarities. Inside each group, 90 % of the students expressed their joy for doing experiments, and it is worthy to highlight that up to 80 % of students claimed that they had learnt and just 50 % admitted they had enjoyed the theoretical explanations.

The mixed results observed in “The theoretical explanation” category for G2 students (Figure 3) are considered to be due to two interrelated reasons: (i) issues of language and (ii) depth of the chemical content taught. On the one hand, words are clearer and more precise than emoticons to express emotions. For example, the negative assessment of the theoretical explanation by students (both G1 and G2) consisted, mainly, in the use of adjectives “complicated” and “difficult” with just a few “boring” while, in the case of emoticons, students used emoticons 6, 7, 8, 9, 16 (negative), 13 (neutral) and 15 (positive) indistinctly. It is this emoticon, number 15, which raises the controversy. In our categorization, emoticon 15 was considered positive but many students who valued the theoretical explanation as “difficult” or “complicated” chose this emoticon to represent it. We assume this is due to the stereotypes related to scientists (i.e. they are males; they wear glasses; they work on complicated subjects) (Finson, 2002). This would correspond to the second reason: the contents explained to G2 students were deeper from the chemical point of view, that is, more “scientific” and that possibly contributed to their choice of the stereotypically “scientific image" (emoticon 15).

Conclusions

In this work, we developed an innovative context-based teaching experience on the subject of chemical senses designed under recommendations from the Sustainable Conscious Cognitive Learning Model (MACCS) and its communicational derivations (Galagovsky, 2004a, 2004b) that pose situations of “common sense” in order to raise cognitive conflicts about controversial information.

Since the activities had been designed to promote students’ motivation and self-awareness on their previous knowledge, this approach was designed to facilitate a relaxed atmosphere in class where the aim was not to get the correct answer but it was the diversity of mental representations shown to account for their choice what was evaluated.

The successful outcome of this teaching approach has been shown by the results of the metacognitive poll (Figure 2 and Figure 3) that account for students’ motivation and from the results driven from the Post-Test (Table 6).

This proposal for teaching chemical senses could be used to establish ground concepts for further deepen teaching of canonical scientific subjects, such as solutions (related to sense of taste), volatility, biochemical and chemical equilibrium (related to senses of taste and smell), and as a starting point to explore the systems of the human body and their relationship with the scientific challenge of knowing the power of human brain and its mind. Moreover, non-traditional contents could be proposed like food marketing considering consumers’ decision involved in behavioral economics.

Finally, this type of contents could be used by students to analyze the material they find on the web critically, since many misconceptions about the chemical senses are still repeated and reinforced in videos and online material.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT), Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA) and Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) for financial support. Authors are also grateful to the anonymous referees who helped improve this work.

References

Arvidson, K. (1979). Location and variation in number of taste buds in human fungiform papillae. Scandinavian Journal of Dental Research, 87(6), 435–442.10.1111/j.1600-0722.1979.tb00705.xSearch in Google Scholar

Bennet, J., & Lubben, F. (2006). Context-based Chemistry: The Salters approach. International Journal of Science Education, 28(9), 999–1015.10.1080/09500690600702496Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, J., Lubben, F., & Hogarth, S. (2007) Bringing science to life: A synthesis of the research evidence on the effects of context-based and STS approaches to science teaching. Science Education, 91, 347–370.10.1002/sce.20186Search in Google Scholar

Buck, L. (2000a). The molecular architecture of odor and pheromone sensing in mammals. Cell, 100(6), 611–618.10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80698-4Search in Google Scholar

Buck, L. (2000b). Smell and taste: the chemical senses. In E. R. En Kandel, J. H. Schwartz & T. M. Jessell (Eds.), Principles of Neural Science. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.Search in Google Scholar

Caamaño, A. (2011) Enseñar Química mediante la contextualización, la indagación y la modelización. Alambique Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales, 69, 21–34.Search in Google Scholar

Caamaño, A. (2015). Del CBA i el CHEM a la química en context: un recorregut pels projectes de química des dels anys setanta fins a l’actualitat. EduQ, 20, 13–24.Search in Google Scholar

Carrió, M., & Costa, M. (2017). ¡Ha desaparecido un ratón! ¿Nos ayudáis a buscar al culpable? Análisis del impacto didáctico y emocional de un encargo ficticio. Enseñanza de las ciencias, 35(3), 151–173.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.2226Search in Google Scholar

Chandrashekar, J., Hoon, M. A., Ryba N. J. P., & Zuker, C. S. (2006). The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature, 444, 288–294.10.1038/nature05401Search in Google Scholar

Collings, V. B. (1974). Human taste response as a function of locus of stimulation on the tongue and soft palate. Perception & Psychophysics, 16(1), 169–174.10.3758/BF03203270Search in Google Scholar

Drake, N. (2011). Life: Dolphin can sense electric fields: Ability may help species track prey in murky waters. Science News, 180(5), 12.10.1002/scin.5591800512Search in Google Scholar

Duffy, V. B., & Bartoshuk, L. M. (2000). Food acceptance and genetic variation in taste. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100(6), 647–55.10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00191-7Search in Google Scholar

Edelsztein, V. C., & Galagovsky, L. (2019). Teaching about chemical senses. Inquiry into a motivating experience. Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Revista de investigación y experiencias didácticas, 37(1), 177–177.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.2553Search in Google Scholar

Enjin, A., Zaharieva, E. E., Frank, D. D., Mansourian, S., Suh, G. S., Gallio, M., Stensmyr, M. C. (2016). Humidity sensing in Drosophila. Current Biology, 26(10), 1352–1358.10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.049Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Finson, K. D. (2002), Drawing a scientist: What we do and do not know after fifty years of drawings. School Science and Mathematics, 102, 335–345.10.1111/j.1949-8594.2002.tb18217.xSearch in Google Scholar

Firestein, S. (2001). How the olfactory system makes sense of scents. Nature, 413, 211–218.10.1038/35093026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Foley, H., & Matlin, M. (2010). Sensation and Perception. 5th edition. Oxford: Taylor & Francis.Search in Google Scholar

Galagovsky, L. (2004a). Del Aprendizaje Significativo al Aprendizaje Sustentable. Parte 1: el modelo teórico. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 22(2), 229–240.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.3885Search in Google Scholar

Galagovsky, L. (2004b). Del Aprendizaje Significativo al Aprendizaje Sustentable. Parte 2: derivaciones comunicacionales y didácticas. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 22(3), 349–364.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.3869Search in Google Scholar

Galagovsky, Lydia R., & Adúriz-Bravo, Agustín. (2001). Modelos y analogías en la enseñanza de las ciencias naturales. El concepto de modelo didáctico analógico. Enseñanza de las ciencias: revista de investigación y experiencias didácticas, [en línea], 19(2), 231–42.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.4000Search in Google Scholar

Garófalo, S. J. (2010). Obstáculos epistémicos de aprendizaje del tema metabolismo de Hidratos de Carbono. Un estudio transversal. (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina.Search in Google Scholar

Gilbert, J. K., Bulte, A. M. W., & Pilot, A. (2011). Concept development and transfer in context-based science education. International Journal of Science Education, 33(6), 817–837.10.1080/09500693.2010.493185Search in Google Scholar

Glynn, S. M. & Duit, R. (eds.). (1995). Learning science in schools. Hillsdale, N. J.: Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Gómez Crespo, M. A, Pozo, J. I. & Gutiérrez Julián, M. S. (2004). Enseñando a comprender la naturaleza de la materia: el diálogo entre la química y nuestros sentidos. Educación Química, 15(3), 198–209.10.22201/fq.18708404e.2004.3.66177Search in Google Scholar

Hugo, D. V. (2012). Emociones y modelización escolar de procesos químicos mediados por las nuevas tecnologías de la información y Comunicación (TIC), Educación en la Química, 18(1), 38–44.10.15517/aie.v1i1.8459Search in Google Scholar

Ikeda. K. (2002). New Seasonings, Smell and taste: the chemical senses. Chemical Senses, 27(9), 847–849.10.1093/chemse/27.9.847Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Keller, J. (2010). Motivational design for learning and performance. The ARCS model approach. Berlín, Alemania: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4419-1250-3Search in Google Scholar

Köster E. P., & de Wijk R. A. (1991) Olfactory Adaptation. In D. G. En Laing, R. L. Doty, & W. Breipohl (Eds.), The Human Sense of Smell. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-76223-9_10Search in Google Scholar

Lerman, Z. M. (2003). Using the arts to make chemistry accessible to everybody. Journal of Chemical Education, 80(11), 1234–1243.10.1021/ed080p1234Search in Google Scholar

Lerman, Z. M. (2005). Chemistry: An inspiration for theater and dance. Chemical Education International, 6, 1–5.Search in Google Scholar

Limón, M. & Mason, L. (eds.). (2002). Reconsidering conceptual change. Dordrecht, Holanda: Kluwer.Search in Google Scholar

Marbà, A., & Márquez, C. (2010). ¿Qué opinan los estudiantes de las clases de ciencias? Un estudio transversal de sexto de primaria a 4° de ESO. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 28(1), 19–30.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.3618Search in Google Scholar

Marchán, I., & Sanmartí, N. (2015). Potencialitats i problemàtiques dels projectes de química en context. Educació Quimica, 20, 4–12.Search in Google Scholar

Matsuo, R. (2000) Role of saliva in the maintenance of taste sensitivity. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine, 11(2), 216–229.10.1177/10454411000110020501Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mellado, V., Borrachero, A. B., Brígido, M., Melo, L. V., Dávila, M. A., Cañada, F., Conde, M. C., Costillo, E., Cubero, J., Esteban, R., Martínez, G., Ruiz, C., Sánchez, J. (2014) Las emociones en la enseñanza de las ciencias. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 32(3), 11–36.10.5565/rev/ensciencias.1478Search in Google Scholar

Meroni, G., Copello, M. I., & Paredes, J. (2015). Enseñar química en contexto. Una dimensión de la innovación didáctica en educación secundaria. Educación Química, 26(4), 275–280.10.1016/j.eq.2015.07.002Search in Google Scholar

Mojet, J., Christ-Hazelhof, E., & Heidema. J. (2001). Taste perception with age: Generic or specific losses in threshold sensitivity to the five basic tastes? Chemical Senses, 26(7), 845–860.10.1093/chemse/26.7.845Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mourtos, N. J., DeJong-Okamoto, N., & Rhee, J. (2004). Open-ended problem-solving skills in thermal-fluids engineering. Global Journal of Engineering Education, 8(2), 189–199.Search in Google Scholar

Nentwig, P. M., & Demuth, R. (2007). Chemie im Kontext: Situating learning in relevant contexts while systematically developing basic chemical concepts. Journal of Chemical Education, 84(9), 1439–1444.10.1021/ed084p1439Search in Google Scholar

Otero, M. R. (2006). Emotions, feelings and reasoning in science education. Revista electrónica en Educación de las Ciencias, 1(2), 24–53.10.54343/reiec.v1i1.358Search in Google Scholar

Pérgola, Martín, & Galagovsky, Lydia. (2014). Puesta a prueba de una unidad didáctica dentro del enfoque de Química en contexto. Educación en la Química en Línea, 20, 143–155.Search in Google Scholar

Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211–227.10.1002/sce.3730660207Search in Google Scholar

Pozo, J. I., & Gómez Crespo, M. A. (1998). Aprender y enseñar ciencia. Madrid: Morata.Search in Google Scholar

Proctor, R. W., & Proctor, J. D. (2006). Sensation and Perception. In G. En Salvendy (Ed.), Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 3rd edition. NJ, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.10.1002/0470048204.ch3Search in Google Scholar

Proske, U., & Gandevia, S. C. (2012). The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiological Reviews, 92(4), 1651–1697.10.1152/physrev.00048.2011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Purves, D., Augustine, G. J., & Fitzpatrick, D. (Eds.). (2001). Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Ramsden, J. M. (1997). How does a context-based approach influence understanding of key chemical ideas at 16+? International Journal of Science Education, 19(6), 697–710.10.1080/0950069970190606Search in Google Scholar

Reed, D. R. (2008). Birth of a new breed of supertaster, Chemical Senses, 33(6), 489–491.10.1093/chemse/bjn031Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rodríguez Moneo, M. (1999). Conocimiento previo y cambio conceptual. Buenos Aires: Aique.Search in Google Scholar

Rozin, P. (1982) Taste-smell confusions and the duality of the olfactory sense. Perception & Psychophysics, 31, 397.10.3758/BF03202667Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Sánchez Díaz, I., Pérgola, M., Galagovsky, L., Di Fuccia, D. S., & Valente, V. (2018). Chemie im Kontext: The students’ view on its adaption in Spain and Argentina – two case studies. Scientia in educatione, 9(2), 131–145.10.14712/18047106.1028Search in Google Scholar

Sanmartí, N., & Marchán, I. (2015). La educación científica del siglo XXI: Retos y propuestas. Investigación y Ciencia, 469, 30–39.Search in Google Scholar

Sanmartí, N., Burgoa, B., & Nuño, T. (2011). ¿Por qué el alumnado tiene dificultad para utilizar sus conocimientos científicos escolares en situaciones cotidianas? Alambique, 67, 62–69.Search in Google Scholar

Schnotz, W., Vosniadou, S., & Carretero, M. (eds.). (1999). New Perspectives on conceptual change. Oxford: Elsevier Science.Search in Google Scholar

Sinatra, G. & Pintrich, P. R. (Eds.) (2003). Intentional conceptual change. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.10.4324/9781410606716Search in Google Scholar

Small, D. M., & Prescott, J. (2005). Odor/taste integration and the perception of flavor. Experimental Brain Research, 166, 345–357.10.1007/s00221-005-2376-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Stevens, J. C., Bartoshuk, L. M., & Cain, W. S. (1984). Chemical senses and aging: taste versus smell. Chemical Senses, 9(2), 167–179.10.1093/chemse/9.2.167Search in Google Scholar

Su, C-Y., Menuz, K., & Carlson, J. R. (2009). Olfactory perception: Receptors, cells, and circuits. Cell, 139(1), 45–59.10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Verhagen, J. V., & Engelen, L. (2006). The neurocognitive bases of human multimodal food perception: Sensory integration. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30, 613–650.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.11.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Vosniadou, S. (2007). The cognitive-situative divide and the problem of conceptual change. Educational Psychologist, 42(1), 55–66.10.1080/00461520709336918Search in Google Scholar

Wu, L.-Q., & Dickman, J. D. (2012). Neural correlates of a magnetic sense. Science, 336, 1054–1057.10.1126/science.1216567Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 IUPAC & De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms