Abstract

The best tutors give a student the appropriate amount of guidance necessary for learning while helping the student stay confident, motivated and focused. So-called intelligent tutoring systems, trying to replicate the discipline-specific and the psychological dimensions of expert human tutoring, require enormous investments and are not accessible to the larger student population. PQtutor (physical quantities tutor) is a free online tutor designed to help students work out homework problems closely related to worked examples. The software is an extension of a free online calculator for science learners and uses problems from an open (free) textbook, making PQtutor accessible in terms of both technology and cost. PQtutor works by comparing student input to a model answer in order to generate prompts for finding a path to the solution and for correcting mistakes. The feedback is in the form of questions from a virtual study group suggesting problem-solving moves such as accessing relevant content knowledge, reviewing worked examples, or reflection on what their answer means. In cases where these moves have been exhausted but the problem remains unsolved, the tutoring system suggests seeking intelligent human help.

Introduction

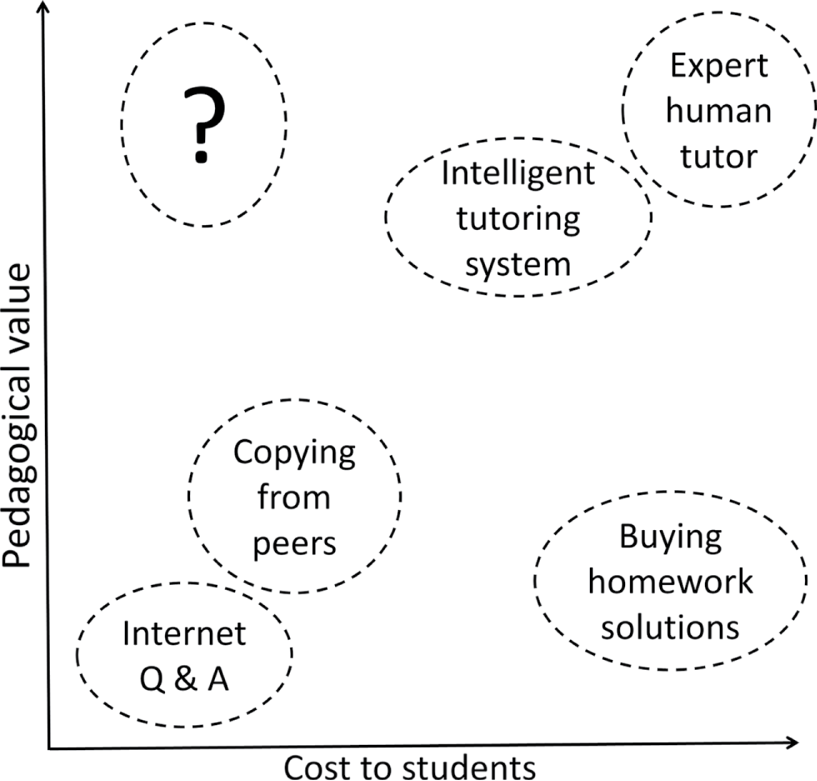

Learning to solve quantitative problems in college chemistry courses is a challenge for many students (Gulacar & Fynewever, 2010). Students have to integrate general problem-solving skills, chemical insight, unit algebra and error propagation into their solution, and learn how to tackle multi-step problems on paper. Learning happens mainly when students work out problems on their own and study for exams (Leinhardt, Cuadros, & Yaron, 2007). On the other hand, feedback is important in learning, and is most effective if it is timely (Crippen, Schraw, & Brooks, 2005). Some colleges provide drop-in help to support student’s independent study, offer supplemental instruction or recitations. In the absence of these, students who get frustrated or stuck while doing homework seek various forms of help. While there is a growing market for paid online supplements such as intelligent tutoring software (Wilson & Kennedy, 2017) or online human tutoring, not all students can afford these. There is also a growing amount of free help available on the internet’s question-and-answer sites, but these contain material that can be misleading, at an inappropriate level, or plain wrong. Overall, there is a lack of low-cost resources with high pedagogical value (Figure 1).

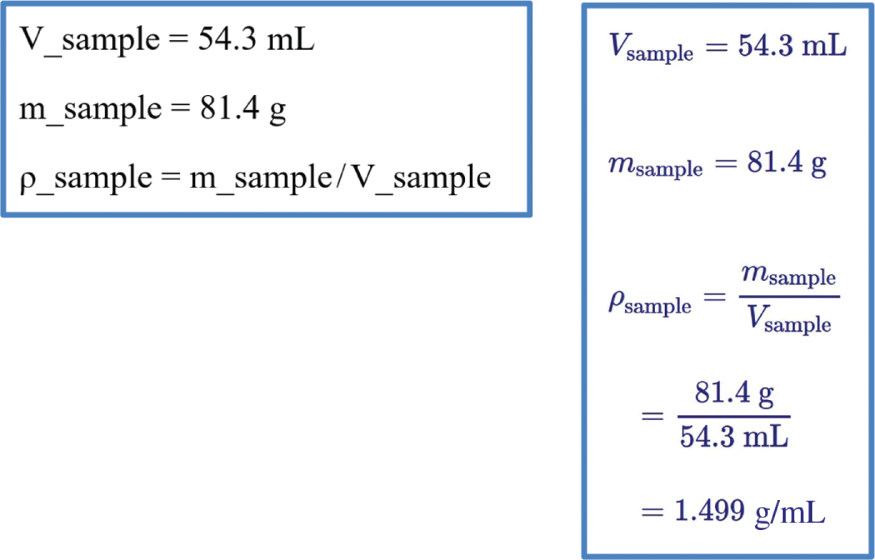

Striving to provide a free but valuable tutoring system to students, I decided to leverage two open resources, the OpenStax Chemistry textbook (Flowers et al., 2015) and the online calculator PQcalc developed in my previous work (Theis, 2015). The calculator PQcalc (short for Physical Quantities calculator) works through a browser, and input is plain text entered via the keyboard. Each input command starts with a name, describing the quantity one is defining or calculating, followed by a value or mathematical operations on quantities already defined. Figure 2 shows an example. To calculate the density ρ of a sample with a volume V of 54.3 mL and a mass m of 81.4 g, you would type commands into an input box and see the results after typing “return” or pressing “go”. Variable names and math are typeset in the output for better readability. For example, fractions are written with a fraction bar, and subscripts are used for chemical formulae and for variable names. The calculator takes care of the lower level mechanics such as number arithmetic, unit algebra and error propagation and catches errors such as trying to add a mass to a volume. The second open educational resource, the OpenStax chemistry textbook, contains material typically taught in General Chemistry I and II and provides hundreds of worked example problems as well as more than a thousand end-of-chapter problems. The online tutor PQtutor described here integrates selected problems from this textbook into the existing online calculator to create a free online homework system.

Different ways of getting help with homework. Students seeking help while trying to solve quantitative problems have a choice of options differing in cost and in value. There are expensive options (various forms of tutoring) that have been shown to support learning, cheap options that are of questionable pedagogical value, and unethical services that sell homework solutions. However, there is a lack of homework help that has high pedagogical value while being affordable to all (corresponding to the upper left quadrant labelled “?” in the graph).

User input (left) and output generated by PQcalc (right) for a one-step density calculation.

Objectives

The way PQtutor interacts with students is guided by three objectives. The first objective is to provide a tool that is easy to use and accessible, both while students are enrolled in a course and after. In an age where many students sell their textbooks after they complete a course and lose access to electronic resources just after learning how to use them, it is important to provide tools that remains available. To allow cheap development with limited resources, PQtutor is only quasi-intelligent in the sense that most of the knowledge lies in the model answers (Aleven, Mclaren, Sewall, & Koedinger, 2009). Also, to keep costs down, it does not maintain a model the student’s knowledge state (Desmarais & Baker, 2012). Despite this lack of artificial intelligence, it can assist learning nonetheless because students and instructors are intelligent (Baker, 2016).

The second objective of PQtutor is to preserve the merits of pencil-and-paper calculations (Smithrud & Pinhas, 2015) while providing closer connections to the chemistry context. On paper, students can summarize chemical information using formulas or equations, they can work out algebra and interpret the results of their calculations. Typically, however, the calculations are done with a hand-held calculator, removing the context (including the units) of the problem at hand. PQtutor allows students to practice quantitative problem-solving without losing sight of the chemistry context. Integrating the scientific context into the calculator is intended to bridge the divide between algorithmic and conceptual aspects of learning chemistry (Nakhleh & Mitchell, 1993; Cracolice, Deming, & Ehlert, 2008).

The third objective of PQtutor is to provide timely, useful, and friendly feedback to students. Asking for help triggers reminders of general problem-solving strategies first, followed by more specific hints that do not give away the answer (the numerical answer is in the textbook). The intent is to keep frustration and boredom at bay while encouraging students to think on their own (Baker, D’Mello, Rodrigo, & Graesser, 2010).

User interface

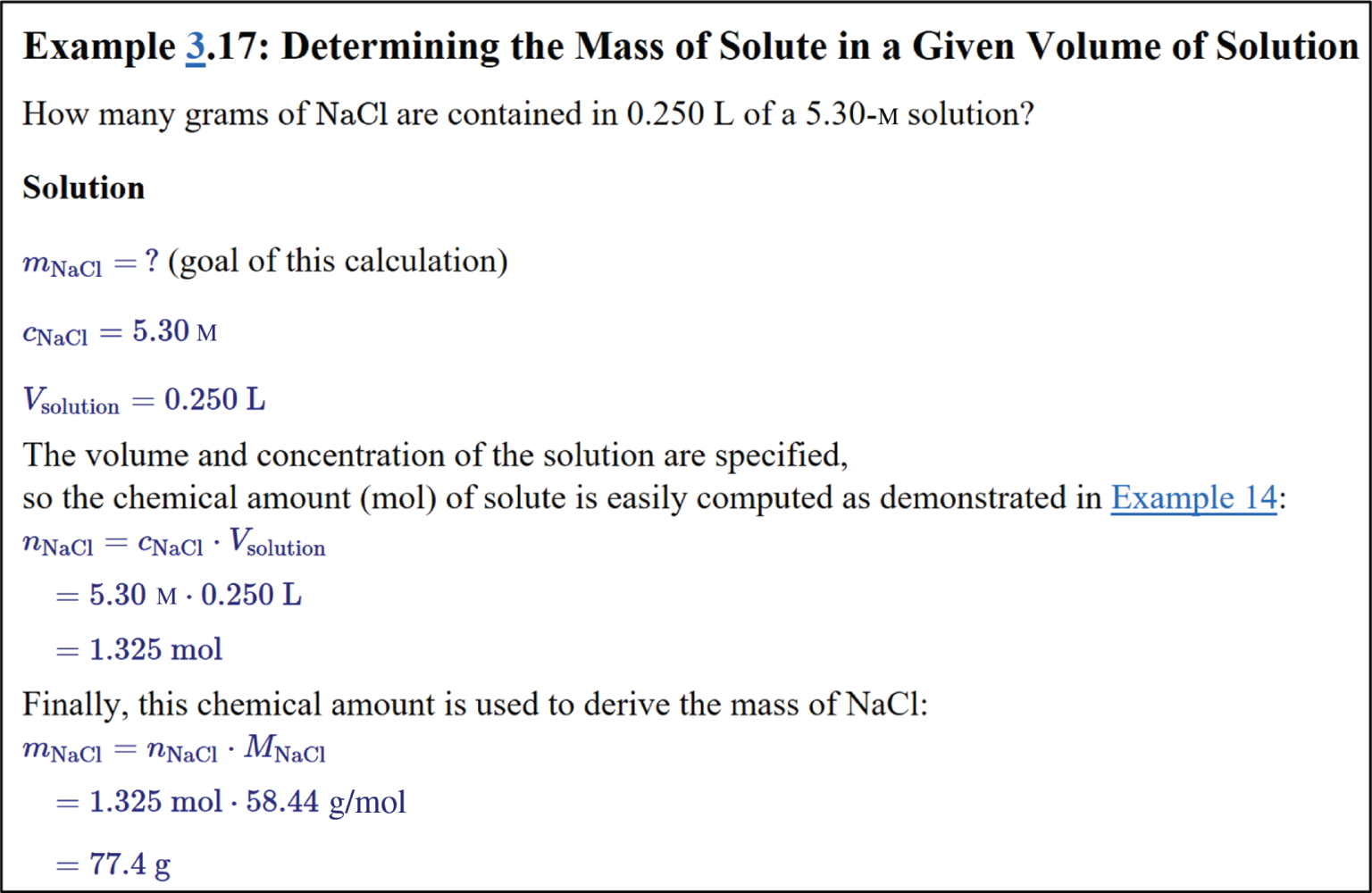

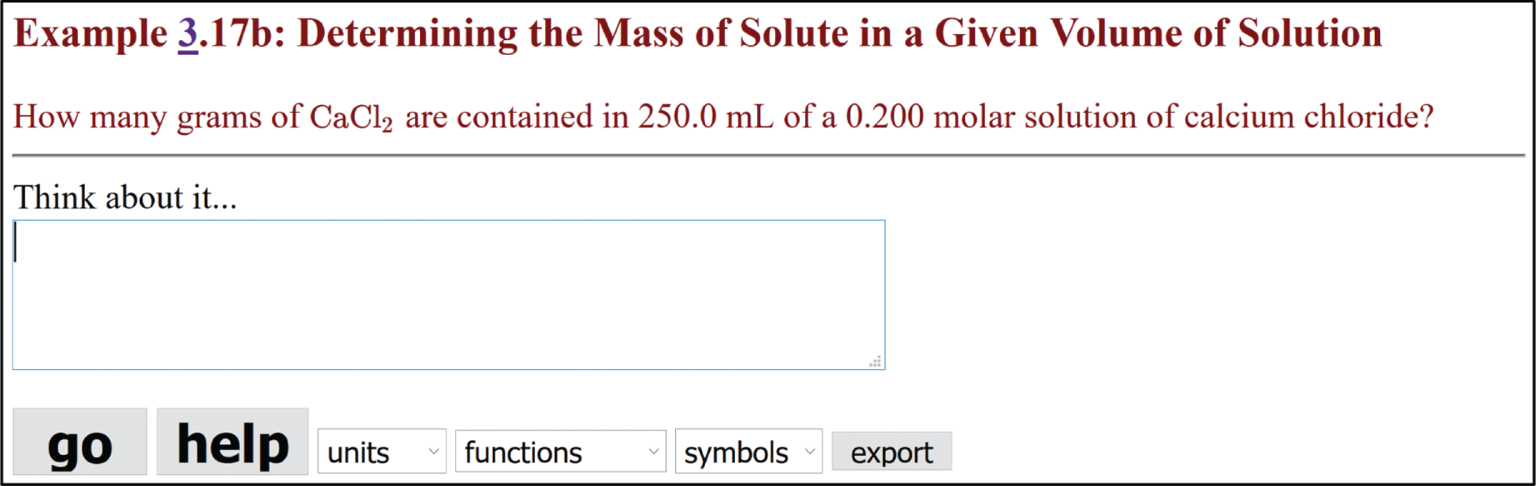

PQtutor works through a browser and has a user interface similar to the PQcalc calculator (Theis, 2015). Different parts of PQtutor are accessed through different links students receive from their instructor. The exercises currently available are all adapted from the OpenStax Chemistry textbook (Flowers et al., 2015). PQtutor displays worked examples from the textbook that demonstrate how to solve a certain type of problem (Figure 3 and link to PQtutor in Supplementary material S1). In the textbook, worked examples are paired with similar follow-up problems to which the numerical answer, but not the solution path is given. PQtutor displays these follow-up problems (or any other question) as well, and students enter commands into the input box to work out these problems (Figure 4 and link to live demo in Supplementary material S1). If students are unsure of how to proceed with a problem, or they just want feedback on what they already entered, they can request help from a virtual study group by just pressing go without any input. Before students submit their solution, they have to answer a multiple-choice question to reflect on the calculation and its meaning. A short video (Supplementary material S2) illustrates the mechanics of solving an exercise and submitting it to PQtutor (and the instructor).

PQtutor showing a worked example. Links (underlined, blue) are to the chapter summary and to a related worked example.

PQtutor posing a homework problem. The question is shown in maroon on the top. To work out the problem, students type commands into the input box.

Feedback and assessment

Tutors give feedback to students to scaffold their problem solving attempts. To achieve learning, the amount of information and the type of information given by the tutor has to be carefully chosen. Students should receive feedback, but not in a way that hinders self-regulated learning (Aleven, Roll, McLaren, & Koedinger, 2016; VanLehn, Siler, Murray, Yamauchi, & Baggett, 2003). In PQtutor, it is up to the student to seek help (by pressing go without entering any input) and to decide how much help to ask for. The feedback is structured around a problem solving model that guides students towards independent problem solving and self-regulated learning.

Problem solving model

When humans solve problems, they often first represent the problem in a way they understand, and then proceed to make a plan and execute it. While and after solving the problem, they monitor their progress. There are multiple models of problem solving (reviewed in Yuriev, Naidu, Schembri, & Short, 2017); in PQtutor, problem solving is broken down into three phases: (1) representing the problem (2) steps toward the answer (3) the answer. The software classifies elements of a solution – entered by a student or the model solution given for each problem – as known quantities (some explicitly in the text of the question, some pulled from other sources), goals (written in the form “q = ?” to show the intent to determine a quantity q), intermediate calculation steps, and answers. Chemical equations, comments containing algebra and other comments are recognized as such in the model solution, but not fully evaluated for their content. When students interact with the tutoring system, this model is used as a framework to analyze and discuss student work and to give feedback at a general level.

Virtual study group as pedagogical agents

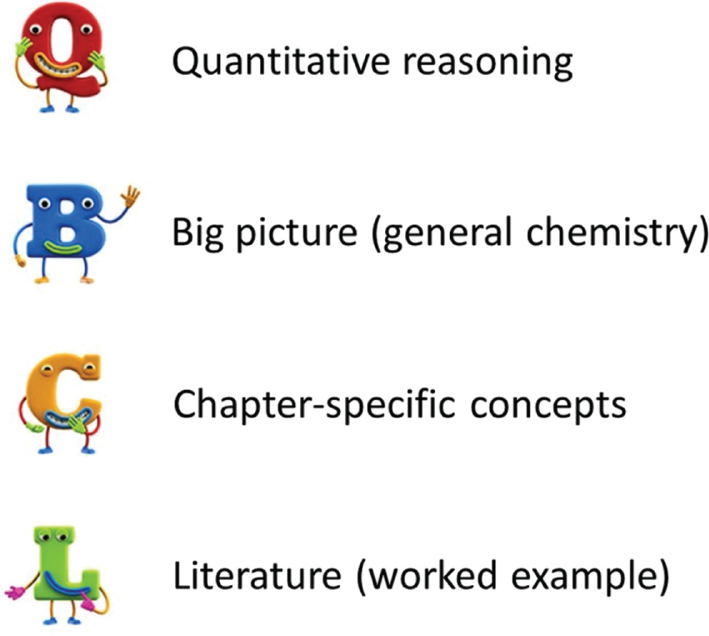

Tutoring in PQtutor occurs through interaction with a virtual study group that acts as a learning companion (Chou, Chan, & Lin, 2003). The study group provides encouragement and specific help on the question at hand, in a sometimes playful but always polite manner (Wang et al., 2008). There are four characters in the virtual study group, Q, B, C, and L (Figure 5). Each one of them represents a different set of skills, strategies or tactics to tackle quantitative problems. Student Q has general quantitative problem-solving skills such as considering the relationship between knowns and unknowns, performing dimensional analysis, picking up on common patterns (e.g. two-state problems), realizing the need to solve for an unknown and some general troubleshooting strategies. Student B has a firm grasp of the big picture tools chemistry has to offer, such as the periodic table, symbolic notation (chemical formulae and equations), conventions for naming different types of quantities, and data tables available in the textbooks. Student C is the expert on the specific chapter, including the new concepts introduced, the common pitfalls associated with the chapter, and the chapter-specific tools the textbook offers. Student L, finally, likes to look up how others have worked out similar problems, primarily by referring to the worked example. Comments from the study group come in two flavors, corrective feedback or pumps for more information (Graesser, Lu, Jackson, Ventura, & Olney, 2004); corrective feedback points out problems with the work so far, while pumps are leading questions suggesting what the student might do next.

Members of the virtual study group and their respective special power.

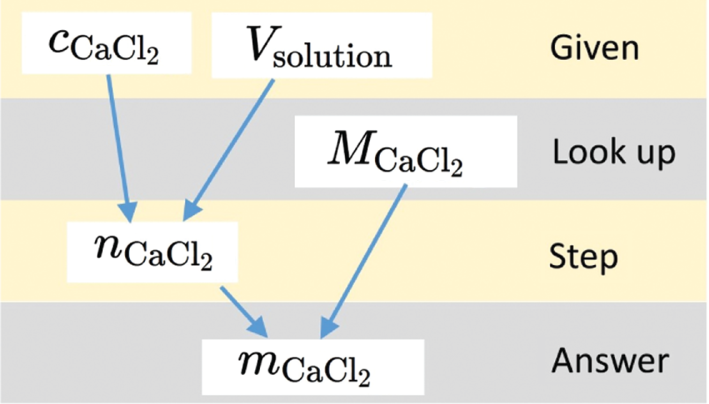

Pumps

Human tutors will prompt students to take the next step towards solving a problem, giving just the right amount of scaffolding so that students can figure out solutions by themselves. This requires substantial knowledge about the psychology of learning in general and about the discipline and the student specifically, none of which PQtutor possesses. Instead, PQtutor turns the model solution into a graph of dependencies (Figure 6), matches the student answer to the solution graph, and identifies reachable sub-goals. Then, characters in the virtual study group proceed to ask guiding questions about missing data from the question, missing data from other sources, relationships between knowns and unknowns, and sub-goals and goals (see video S3 and Supplementary material S1 for link to live demo). Pumps are given in order from general to specific. Students who take pride in figuring out a solution on their own will not receive help they did not ask for (i.e. as soon as one of the prompts gives them an idea on how to proceed, they can try on their own). Students who are trying to game the system and bottom-out the hints will receive plenty of hints, but the solution is never revealed directly (again, the numerical solution is available to students upfront). In fact, the bottom-out hint is a metacognitive one (Casselman & Atwood, 2017), suggesting to seek help from the instructor.

Solution graph for the example shown in Figure 4.

Corrective feedback

PQtutor checks given quantities for dimensions, value, number of significant figures and sensible name. When prompted, the study group gives corrective feedback (see video S4 and Supplementary material S1 for live demo). Results of calculations are matched with those in the model solution. If there is a no good match, the study group will comment. If there is some unexpected input, there will be feedback as well (Supplementary material S1 and video S4). Feedback is given in general terms, but there will be some more specific information (often about which line of input might be incorrect) when hovering over the character’s picture. Feedback never directly states that something is incorrect – it is up to the student to critically examine their work and correct it if necessary. The reason for this is two-fold: On the one hand, the software’s assessment of the students’ work is not flawless (especially if student work and model answer are very different), on the other hand, the students should develop a critical mindset and be responsible for their own conclusions.

Connecting an answer to the bigger picture

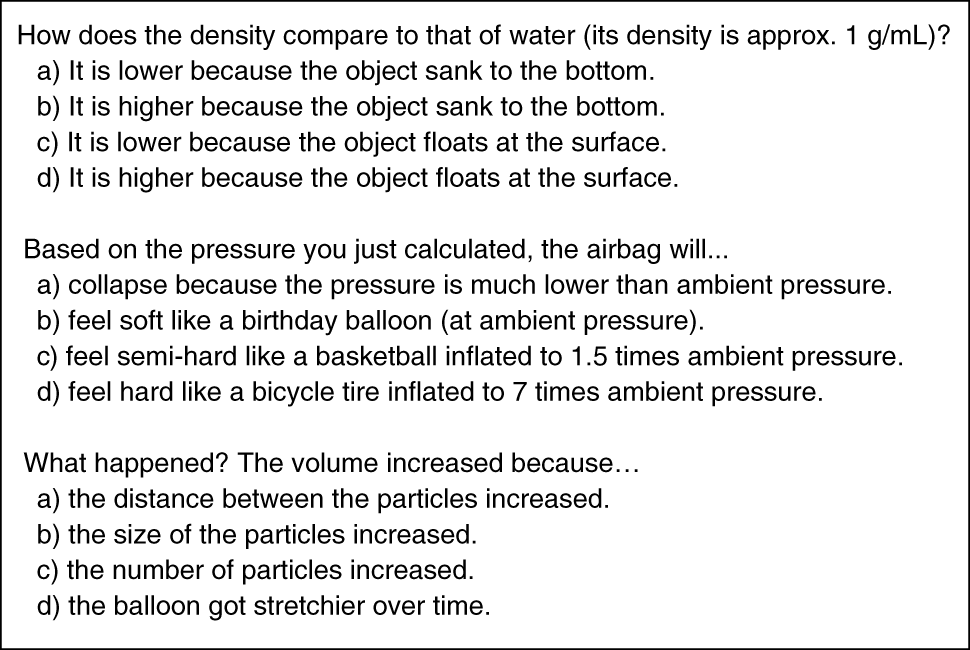

When students are ready to submit their solution to a homework question, they have to answer one final multiple-choice question before moving on. This final “What does the answer mean?” question was inspired by the last step in the COAST problem-solving recipe used in W.W. Norton’s chemistry textbooks (Gilbert, Kirss, Foster, Bretz, and Davies 2018). The purpose is to connect the numerical answer to the chemistry the student is learning in a given chapter, and to foster meaningful problem solving (Kennedy-Justice et al., 2000). The questions come in three flavors. Some ask whether the magnitude (or sign) of the result could have been anticipated from an estimate (Figure 7 top). Others ask for an interpretation of the calculated result (Figure 7 center). Finally, some go after common misconceptions (Figure 7 bottom). In all cases, the question asks the student to make a connection between the result of their calculation and concepts that they are familiar with or have just learned, and to evaluate their answer.

Examples of different types of “What does the answer mean?” questions.

Summative assessment

After the answer is submitted, PQtutor displays a brief written assessment of the work to the student, and sends the student input to the instructor. Grading of the work, if desired, is left to the instructor, who has access to the student work and the preliminary assessment from PQtutor. This models how human tutors and instructors interact when it comes to grading; the tutor can give some preliminary feedback how well students are doing, but the instructor is responsible for grading the student.

Textbook integration

A large portion of the effort behind PQtutor was to adopt the problems of the textbook in a format suitable for it, and writing “What does the answer mean” questions. A benefit of presenting the problems within PQtutor are links to dynamic textbook resources, including an electronic version of the text itself provided on the libretext site (Halpern & Larsen, 2017). To further support making connections between the problem and chemical knowledge, chemical data is available within PQtutor (e.g. molar masses, table of quantities and units) and via links to outside sources (e.g. periodic table, thermodynamic data). The process of adopting a wide range of problems and writing model answers led to ideas how to simplify and expand the ways students can document their problem-solving ideas in Pqtutor. Consequently, I incorporated these ideas into the user interface to improve it.

Adopting problems

It is fairly straightforward to adopt existing questions or author new ones, requiring minimal effort working within PQtutor. First, you provide a description of the problem in plain text. It will be formatted just like user input in PQtutor. Second, you formulate a solution that PQtutor understands, i.e. provide input for a correct solution. All logical intermediate steps should be shown to maximize feedback given to students. Third, you write a multiple-choice follow-up question, with the correct answer marked by an asterisk. For example, Figure 8 shows the text you would enter into a special question authoring form (see Supplementary material S1 for a link to the form) for the example 3.17b used throughout this paper. PQtutor has no other knowledge about this question, and generates the feedback and prompts from the model solution and from the logic of the underlying mathematics. It does have some general knowledge about dimensions, units, and commonly used symbols for certain quantities covering the concepts covered in General Chemistry I and II, so it makes sense to use the symbols for quantities according to IUPAC conventions (Nič, Jirát, Košata, Jenkins, & McNaught, 2009) and listed in a table available in PQtutor (Supplementary material S1).

Instructor input to define a new homework question.

Dynamic textbook resources

Sometimes, students are not aware of resources in their textbook that might help with quantitative problem solving. PQtutor integrates these tools into the hints given by the virtual study group (there is also a study tools page, see link in Supplementary material S1). The B character shows links to the periodic table, the appendices, and information about formulae introduced up to a given chapter. The Q character shows links to a table of quantities and units along with their definitions up to a given chapter. As mentioned above, the L character always seeks information from the matched worked example. Finally, the C character shows links to the chapter summaries and the explanation of keywords in the given chapter. If students adopt the strategies modeled by the virtual peer group, they will learn to make better use of these resources in the textbook (and discipline-specific resources like databases and primary literature later on).

Pilot study using PQtutor

To explore how the tutoring system works in practice, I piloted PQtutor in a General Chemistry I course. In total, 33 students participated working on 8 different questions, and 178 answers were submitted. During the course, students received credit for participation. After the semester concluded, I replayed all the submissions and fine-tuned how the virtual study group reacts to input that matched the model solution, and to input that did not. Moreover, this first field test with students provided important pointers on how one might rigorously test the impact of PQtutor on the development of quantitative problem-solving skills in students of general chemistry. Finally, this anecdotally showed how students fared solving homework problems outside of class using PQtutor.

PQtutor enforces rigor in representing problems

A large portion of the reasoning about student answers within PQtutor is based on quantities’ names and their units. Students who use the conventional symbols for quantities receive better feedback from the virtual study group. If students attempt a calculation that is dimensionally incorrect (such as adding a mass to a volume), they will receive immediate feedback in form of an error message from the calculator, so they have to pay attention to units throughout the calculations. PQtutor makes a clear distinction between measures of concentrations; the amount of substance concentration uses the symbol c (with units mol/L), while dimensionless measures of concentration are expressed using brackets (e.g. [NaCl]). Concerning temperature scales, PQcalc internally always uses the Kelvin scale for temperature. To be able to enter and display quantities using the Celsius scale, PQcalc allows separate units for absolute temperature (°aC) and temperature differences (°ΔC). In some student answers, symbols for quantities had the incorrect case (for example, using upper case C for a concentration). To respond more directly to this student input, PQtutor now tests for this possibility and gives appropriate feedback.

Adapting problem-solving techniques

In the pilot study, some students ran into trouble because they tried to use strategies they are familiar with from pencil-and-paper work. For example, students would take an equation such as the ideal gas law and substitute values into the expression. This does not work in PQtutor because for all input, the left-hand side of an equation has to be a single quantity (to be calculated), and the right-hand side can not contain any unknowns. Instead of using their strategy, PQtutor requires students to first use their algebra skills to solve for the unknown, and then let the software do the arithmetic for them. The benefit of the latter sequence (algebra first, arithmetic second) is that the algebraic result is reusable for an analogous problem with different values, letting students see the patterns.

The problem-solving experience

Although the way calculations are done in PQtutor is modeled on pencil-and-paper calculations, the experience in PQtutor is somewhat different. One practical difference is that it is easier for students to electronically disseminate their work or integrate it into, say, a lab report. Also, students save some time on tedious work through the integrated calculator. On the other hand, text-based computing (rather than using a pocket calculator) is unfamiliar to students and requires some initial effort. Compared to pencil-and-paper calculations, the focus is shifted from lower-level tasks (such as using a pocket calculator) to higher-level tasks (such as representing the homework problem formally within PQtutor, and reflecting on whether the result is plausible).

Using PQtutor in a course

Because PQtutor is an open educational resource, there is no registration or other time-consuming step to start working with it, and it can be used in a course as the sole online homework system or in combination with other tools without incurring additional cost to students. However, instructors should put some thought into how to introduce PQtutor to students, and how to integrate it into their course so it supports the learning objectives.

Introducing students to Pqtutor

Students will need some instructions specific to PQtutor before they are ready for homework assignments. For the pilot study, I first introduced the online calculator in class, displaying the user interface on the projection screen and asking them for prompts what I should do next. Then, I demonstrated an entire calculation in class, modeling the problem-solving steps and also showing how to seek help from the virtual study group. After this initial training, I gave students homework by posting the links to the problems. There is also a video demonstrating the steps of setting up and submitting a calculation (see S1 for link). For many students, this amount of training was sufficient to be able to attempt problems independently. Some students, however, would have benefited from more extensive training, as was clear from their subsequent struggle or frustration in using PQtutor on their own. In hindsight, scheduling a session in the computer lab and having students work in small groups to do the first homework assignment would be worthwhile. In order to use the full capabilities of documenting problem solving steps in PQtutor, students also have to learn the meanings of special characters “_ ! @ # [] {}” in naming quantities and annotating the solution with chemical and mathematical information as well as images. Moreover, there are multiple shortcuts (clicking on text to avoid retyping) that save time and let you focus on the problem-solving; students certainly should become familiar with these. There are tutorials built into PQtutor’s help pages that explain these features, and videos that walk you through their use (for links to tutorials see Supplementary material S1; videos are available as Supplementary materials S2, S3, S4).

Role of the instructor

Full-fledged intelligent tutoring systems have a model of a student’s current knowledge and capabilities, and choose question for the student at the appropriate level. This process has been called the outer loop (VanLehn, 2006). For PQtutor, which lacks this model, the instructor has to provide the outer loop, monitoring where students are at, and giving them homework in their proximal zone of development. Because instructors can quickly create new problems and store them in the PQtutor’s question database, they can always assign additional problems at the appropriate level. Finally, the instructor is responsible for deciding on the amount of scaffolding to provide (Puntambekar & Hubscher, 2005; Renkl & Atkinson, 2003). While the combination of worked solutions and follow-up problems gives a fairly high amount of scaffolding, it is possible to give even more structure (e.g. backward fading, Foster, Rawson, & Dunlosky, 2018) or less structure (asking students to work on problems where PQtutor has no answer, i.e. use PQtutor without tutoring). PQtutor was designed to help students practice low and mid-level quantitative reasoning. This allows the instructor to focus on higher-level work in class where PQtutor can serve as a fast calculator while most of the time is spent on problem representation, planning a solution and interpreting the numerical result.

Pedagogy supported by PQtutor

It is up to the instructor to choose how to integrate PQtutor into their course, and there are several options. Questions can be assigned as individual homework, as done in the pilot study described above. Alternatively, questions can be assigned as group work in class, for example for a flipped classroom, or as group work with guidance from a teaching assistant. This allows students to learn from their peers, and if the group encounters a stumbling block not resolved with the help of hints from the software, they can consult with the instructor or teaching assistant. Outside class, students can revisit questions when studying for an exam or use the calculator to check their pencil-and-paper work (and the instructor may choose to incentivize this by giving credit). Finally, PQtutor could also be used in a teaching laboratory, giving a worked example and asking students to solve a similar problem before lab, and then letting them use the calculator to work with the data they measure in lab or after lab. In all these scenarios, working with PQtutor helps students to systematically figure out solutions to problems and to document their work while ensuring correct arithmetic and unit algebra.

Curriculum integration

There is a certain amount of investment for students to learn how to use PQtutor. However, once they become familiar with it and see a benefit in using a calculator that works with units and significant figures and allows rich documentation of the problem-solving process, they can use the software in other contexts, for example when analyzing lab results and writing them up. If PQtutor is used in additional courses, there is no more initial investment, and student can get working right away. At one point in their career, however, they will have to transition to more powerful (and perhaps less friendly) software. Having had some experience with text-based calculations (i.e. coding), it should be easier to transition to other software, reclaiming part of the initial investment.

Discussion

The goal in creating the PQtutor software was to provide affordable tutoring software for students learning the quantitative aspects of chemistry. The user interface and the feedback are designed to allow students to integrate chemistry context and problem solving strategies while working on their homework. A pilot study in a General Chemistry I course suggested that PQtutor can play a valuable role in helping students to learn how to solve quantitative problems, but also that it has some limitations and room for further development.

Strengths

PQtutor is free and accessible through a browser, so there is no setup required. The software supports a range of skill levels, from computational mechanics all the way up to problem solving strategies and metacognitive skills. The textbook is tightly integrated, with worked examples available in the software, and links to the chapter overviews. To encourage meaningful problem solving, PQtutor requires all quantities to be given names, and poses a question about the meaning of the numerical result before students submit their work. Students do not receive feedback by the virtual study group unless they request it, encouraging them to think about when they may or may not need to seek help (i.e. engage in metacognition). When giving feedback, PQtutor starts by reminding students of general problem-solving strategies and progresses to specific hints if more help is requested. The software has mechanisms to recognize partial solutions (e.g. correct steps with incorrect input), improving the feedback given. While using PQtutor, students are introduced to text-based computing as a transferable skill that is helpful for learning to write scripts and code.

Limitations

As with any computer-based tools, students can get frustrated while interacting with the software. The PQtutor software does not detect students affect, so the instructor has to monitor how students are doing and help where needed (demonstrate use of software in class, offer drop-in help or facilitate group work, debrief in the classroom after students attempted problems). Problems could be too hard or too easy for individual students, and the system does not adapt; again, it falls on the instructor to assign homework in a way that helps all the students to learn.

Future development

As instructors use this tool with their students, they will experience how the feedback supports the students, and learn of situations where the dialog with the virtual study group needs tweaking. Because this is an open system, it invites the teaching community to expand or modify it (at the level of authoring problems, but also at the level of changing the software) and to study how it affects student learning. Thus, future development could be focused on expanding the number and type of problems and worked solutions, or on making the feedback more responsive to the most common misconceptions or obstacles students encounter when working on the existing problems.

Conclusions

The PQtutor software described here provides students with an accessible and affordable homework tutor that supports meaningful problem solving and gives timely feedback. It was designed to fill a need for high-quality supplements to existing high-quality open textbooks in chemistry. It focuses on quantitative problem solving, a set of skills that many students encounter as the main stumbling block to success in learning chemistry at the college level. When integrated into coursework in a thoughtful manner by an experienced instructor, it can play a role in increasing student success, helping to provide a solid foundation in quantitative problem solving as a preparation for careers that rely on generating and assessing data in a quantitative manner.

Supplementary information

S1: Links to live demonstrations of the software (attached below)

S2: Video of the user interface of PQtutor

S3: Video of how the virtual study group gives hints

S4: Video of how the virtual study group gives corrective feedback

Open source code available at github.com/ktheis/pqtutor. The online software is hosted at pqcalc.pythonanywhere.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning grant awarded by the Faculty Center of Westfield State University. I would like to acknowledge Westfield State University and my home department Chemical and Physical Sciences for granting the sabbatical that allowed me to work on this project. I would also like to thank Jonathan Gershenzon, Biochemistry department, Max-Planck-Institute of Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, for his gracious support in form of office space, and Estonia-based artists Vladimir and Maksim Loginov of handmadefonts.com for allowing me to use their characters for the virtual study group. The comments from participants in the Spring 2018 CCCE Newsletter (hosted by the American Chemical Society, Division for Education) have been invaluable. Finally, I would like to thank past and present students for their patience in testing and using the PQcalc and PQtutor software.

References

Aleven, V., Mclaren, B. M., Sewall, J., & Koedinger, K. R. (2009). Example-tracing tutors: A new paradigm for intelligent tutoring systems. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Education, 192(2), 105–154.Search in Google Scholar

Aleven, V., Roll, I., McLaren, B. M., & Koedinger, K. R. (2016). Help helps, but only so much: Research on help seeking with intelligent tutoring systems. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(1), 205–223.10.1007/s40593-015-0089-1Search in Google Scholar

Baker, R. S. (2016). Stupid tutoring systems, intelligent humans. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(2), 600–614.10.1007/s40593-016-0105-0Search in Google Scholar

Baker, R. S. J. d., D’Mello, S. K., Rodrigo, M. M. T., & Graesser, A. C. (2010). Better to be frustrated than bored: The incidence, persistence, and impact of learners’ cognitive–affective states during interactions with three different computer-based learning environments. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68(4), 223–241.10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.12.003Search in Google Scholar

Casselman, B. L., & Atwood, C. H. (2017). Improving general chemistry course performance through online homework-based metacognitive training. Journal of Chemical Education, 94(12), 1811–1821.10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00298Search in Google Scholar

Chou, C.-Y., Chan, T.-W., & Lin, C.-J. (2003). Redefining the learning companion: The past, present, and future of educational agents. Computers & Education, 40(3), 255–269.10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00130-6Search in Google Scholar

Cracolice, M. S., Deming, J. C., & Ehlert, B. (2008). Concept learning versus problem solving: A cognitive difference. Journal of Chemical Education, 85(6), 873.10.1021/ed085p873Search in Google Scholar

Crippen, K. J., Schraw, G., & Brooks, D. W. (2005). Performance-related feedback: The hallmark of efficient instruction. Journal of Chemical Education, 82(4), 641.10.1021/ed082p641Search in Google Scholar

Desmarais, M. C., & Baker, R. S. J. D. (2012). A review of recent advances in learner and skill modeling in intelligent learning environments. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 22(1–2), 9–38.10.1007/s11257-011-9106-8Search in Google Scholar

Flowers, P., Theopold, K., Langley, R., Robinson, W. R., Blaser, M., Bott, S., … OpenStax College. (2015). Chemistry. Retrieved from http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/chemistry.Search in Google Scholar

Foster, N. L., Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2018). Self-regulated learning of principle-based concepts: Do students prefer worked examples, faded examples, or problem solving? Learning and Instruction, 55, 124–138.10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.10.002Search in Google Scholar

Gilbert, T. R., Kirss, R. V., Foster, N., Bretz, S. L., & Davies, G. (2018). Chemistry: The science in context (5th. ed). New York: W. W. Norton & Co.Search in Google Scholar

Graesser, A. C., Lu, S., Jackson, G. T., Mitchell, H.H., Ventura, M., Olney, A., & Louwerse, M. M. (2004). AutoTutor: A tutor with dialogue in natural language. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 180–193.10.3758/BF03195563Search in Google Scholar

Gulacar, O., & Fynewever, H. (2010). A research methodology for studying what makes some problems difficult to solve. International Journal of Science Education, 32(16), 2167–2184.10.1080/09500690903358335Search in Google Scholar

Halpern, J. B., & Larsen, D. S. (2017). Driving broad adaptation of open on line educational resources. MRS Advances, 2(31–32), 1707–1712.10.1557/adv.2017.256Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy-Justice, M., DePierro, E., Garafalo, F., Pai, S., Torres, C., Toomey, R., & Cohen, J. (2000). Encouraging meaningful quantitative problem solving. Journal of Chemical Education, 77(9), 1166.10.1021/ed077p1166Search in Google Scholar

Leinhardt, G., Cuadros, J., & Yaron, D. (2007). “One firm spot”: The role of homework as lever in acquiring conceptual and performance competence in college chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 84(6), 1047.10.1021/ed084p1047Search in Google Scholar

Nakhleh, M. B., & Mitchell, R. C. (1993). Concept learning versus problem solving: There is a difference. Journal of Chemical Education, 70(3), 190.10.1021/ed070p190Search in Google Scholar

Nič, M., Jirát, J., Košata, B., Jenkins, A., & McNaught, A. (Eds.). (2009). IUPAC compendium of chemical terminology: Gold book (2.1.0). Research Triangle Park, NC: IUPAC. https://doi.org/10.1351/goldbook.10.1351/goldbookSearch in Google Scholar

Puntambekar, S., & Hubscher, R. (2005). Tools for scaffolding students in a complex learning environment: What have we gained and what have we missed? Educational Psychologist, 40(1), 1–12.10.1207/s15326985ep4001_1Search in Google Scholar

Renkl, A., & Atkinson, R. K. (2003). Structuring the transition from example study to problem solving in cognitive skill acquisition: A cognitive load perspective. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 15–22.10.1207/S15326985EP3801_3Search in Google Scholar

Smithrud, D. B., & Pinhas, A. R. (2015). Pencil–paper learning should be combined with online homework software. Journal of Chemical Education, 92(12), 1965–1970.10.1021/ed500594gSearch in Google Scholar

Theis, K. (2015). PQcalc, an online calculator for science learners. Journal of Chemical Education, 92(11), 1953–1955.10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00366Search in Google Scholar

VanLehn, K. (2006). The behavior of tutoring systems. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 16(3), 227–265.Search in Google Scholar

VanLehn, K., Siler, S., Murray, C., Yamauchi, T., & Baggett, W. B. (2003). Why do only some events cause learning during human tutoring? Cognition and Instruction, 21(3), 209–249.10.1207/S1532690XCI2103_01Search in Google Scholar

Wang, N., Johnson, W. L., Mayer, R. E., Rizzo, P., Shaw, E., & Collins, H. (2008). The politeness effect: Pedagogical agents and learning outcomes. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 66(2), 98–112.10.1016/j.ijhcs.2007.09.003Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, E. E., & Kennedy, S. A. (2017). Modern “homework” in general chemistry: An extensive review of the cognitive science principles, design, and impact of current online learning systems. In P. M. Sörensen & D. A. Canelas (Eds.), Online Approaches to Chemical Education. ACS Symposium Series (Vol. 1261, pp. 101–130). Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2017-1261.ch009.10.1021/bk-2017-1261.ch009Search in Google Scholar

Yuriev, E., Naidu, S., Schembri, L. S., & Short, J. L. (2017). Scaffolding the development of problem-solving skills in chemistry: Guiding novice students out of dead ends and false starts. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 18(3), 486–504.10.1039/C7RP00009JSearch in Google Scholar

Supplementary material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2018-0009).

© 2019 IUPAC & De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms

Articles in the same Issue

- Other

- A new classification scheme for teaching reaction types in general chemistry

- Proceedings Paper

- PQtutor, a quasi-intelligent tutoring system for quantitative problems in General Chemistry

- Case Report

- The experience of introducing 8–10 y.o. children into chemistry

- Review Article

- A systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education – analysis of earlier research and educational use through technological pedagogical content knowledge framework

- Good Practice Reports

- How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon’s test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes

- 3D-printed, home-made, UV-LED photoreactor as a simple and economic tool to perform photochemical reactions in high school laboratories

- Research Articles

- Organic chemistry lecture course and exercises based on true scale models

- Analysing the chemistry in beauty blogs for curriculum innovation

- Good Practice Report

- Chemical senses: a context-based approach to chemistry teaching for lower secondary school students

- Research Article

- Utilizing Rasch analysis to establish the psychometric properties of a concept inventory on concepts important for developing proficiency in organic reaction mechanisms