Abstract

This article delves into the trajectory of corpus translation studies (CTS) over the past two decades, summarizing key areas of existing research and identifying potential gaps and challenges within the field. The review encompasses various research areas, including translation universals, translator style, translation norms, and translation pedagogy. It acknowledges the valuable contributions made in these areas while also highlighting potential areas for improvement, such as the need to incorporate functional aspects in translator style research and align translation training programs with professional requirements. The review introduces (De Sutter, Gert, and Marie-Aude Lefer. 2020. “On the Need for a New Research Agenda for Corpus-Based Translation Studies: A Multi-Methodological, Multifactorial and Interdisciplinary Approach.” Perspectives 28 (1): 1–23) new research agenda for CTS, which advocates for multifactorial designs, methodological pluralism, and interdisciplinarity. This agenda facilitates two analysis modes: one utilizing corpus methods to examine translation products, and the other employing diverse methods to investigate products, processes, participants, and contexts in corpus-assisted translation practices. It is argued that these two analysis modes offer valuable guidance for future corpus-assisted translation studies.

1 Introduction

In the late 1970s, translation studies began to shift away from its prescriptive nature, which treated translation as a rule-based linguistic activity, to a broader understanding of it as a human endeavor (Cuéllar 2002, 64; Toury 1980, 79–81). This shift of perspective was marked by Holmes’s proposal of Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS) in 1972, focusing on what translation is, rather than what translation should be. As a result, DTS differentiates itself from previous studies of translations by shifting the research focus from source languages/cultures to target languages/cultures (Xia 2014, 12).

In the 1990s, Corpus Linguistics (CL), with its emphasis on empirical methodologies and contextualizable results, became popular across various linguistic research domains (Biber and Reppen 2015, 2–3; McCarthy and O’Keeffe 2010, 5). In translation studies, Baker (1993) recognized the potential of using corpus linguistic methods to examine the characteristics of translated language and to validate Toury’s concept of “translation norms” (Baker 1993, 239). This has led to the widespread use of corpora in DTS, analyzing products, processes, participants, and contexts in translation (Saldanha and O’Brien 2014).

Corpus-assisted Translation Studies (CTS) has developed several key research areas, expanding both the “pure” and “applied” branches of Holmes’s map of translation studies. This article will explore some of these areas, including translation universals, translator style, translation norms, and translation pedagogy. The selection of translation universals, translator style, translation norms, and translation pedagogy covers essential aspects of translation studies that benefit from corpus methodologies, combining theoretical insights with practical applications. These areas provide a balanced overview, allowing for an in-depth exploration of both the underlying theories and the practical aspects of translation. The focus of the following discussion will be placed on recent advancements and potential research gaps in each area, and future avenues of research to advance the field of studies.

2 Translation Universals

According to Baker (1993, 243), translation universals are proposed features that are believed to be found in all translated texts, regardless of the specific languages involved. These universals are thought to be independent of the linguistic systems and structures of individual languages. Frawley (1984) refers to these as the “third code” that differentiates translated from non-translated languages. Key universal features in translation include, but are not limited to, explicitation, implication, simplification, normalization, sanitation, leveling-out, and shining-through. Given their widespread occurrence, many previous studies (e.g., Gumul 2021; Liu, Liu, and Lei 2022; Szymor 2018; Zasiekin 2019) have been conducted to study each of these translation universals. Instead of dissecting each universal feature individually, the forthcoming section will offer a comprehensive overview, taking a holistic approach to the main topics explored in these studies. These topics concerns the classification and the causes of translation universals as well as the research designs in the investigation of translation universals (refer to Figure 1). This approach brings forth two distinct advantages. First, it provides a concise summary of noteworthy discoveries, enabling a collective evaluation of translation universals. Second, it avoids the need for justifying the selection criteria for specific universals, thus effectively reducing the potential biases to influence the review process.

Key topics in the corpus-assisted studies of translation universals.

2.1 Classification of Translation Universals

In the past decade, there has been a notable surge of interest in the classification of translation universals. One prominent classification was proposed by Chesterman (2010, 176), who categorized them into two types: S-universals and T-universals. S-universals primarily focus on the differences between translations and their source texts (STs). These universals shed light on the distinctive features that arise during the translation process, highlighting the changes, adaptations, or transformations that occur when moving from the source language to the target language. On the other hand, T-universals center around the distinctions between translations and non-translations in the target language (TTs). These universals explore the specific characteristics that set translations apart from other texts produced directly in the target language.

Besides, Zasiekin (2016) proposed an alternative approach of classification based on functional characteristics. Zasiekin’s classification focuses on two key aspects: the manipulation of information load and the manipulation of information complexity. The manipulation of information load refers to how translators handle the amount of information conveyed in the translation compared to the source text. This can involve condensing, expanding, or reorganizing the information to suit the target language and audience. The manipulation of information complexity, on the other hand, pertains to the level of complexity in the translation compared to the source text. Translators may simplify or amplify the complexity of the information to ensure its comprehensibility and effectiveness in the target language context.

While these classifications by Chesterman and Zasiekin offer a broad perspective on translation universals, there is still a need for a more nuanced understanding of individual features within these universals. Further research and analysis are required to delve deeper into the specific characteristics and mechanisms that underlie these universals, providing a more comprehensive and detailed account of their nature and implications.

Klaudy and Károly (1998) was the first to systematically classify single translation universals. Her classification encompassed four types of translation universals: obligatory, optional, pragmatic, and translation-inherent universals. This classification has prompted the analysis of subtle differences among universal features. For instance, Becher (2011) applied Hallidayan functional linguistic theories to categorize explicitation/implication into interactional shifts, cohesive shifts, and denotational shifts, corresponding respectively to the interpersonal, textual, and ideational metafunctions of language. Similarly, Kajzer-Wietrzny (2015) classified simplification into lexical, syntactic, and stylistic categories, each addressing different linguistic levels and purposes.

While the number of studies on this topic is limited, these classification efforts have greatly improved our theoretical grasp on the diverse phenomena covered by translation universals.

2.2 Causes of Translation Universals

There seem to be a consensus among scholars regarding the potential causes of translation universals, such as explicitation, implication, and simplification. These factors are widely recognized as influential forces that shape the translation process across various languages and contexts. Baumgarten, Meyer, and Özçetin (2008), Hu (2011), and Tang and Liu (2016) have identified linguistic and cultural differences between source and target texts, as well as translators’ stylistic preferences, as the primary causes of these universals. Recent psycholinguistic and neurolinguistic research has further enriched our understanding of the causes behind these universals. Zasiekin (2014, 2019 and O’Brien (2015) have highlighted the role of bilingual processing experience in shaping translators’ use of universal features. Notably, differences in the application of these features between professional and amateur translators have been observed. For instance, professionals tend to use more explicitation, while less experienced translators often lean towards implicitation. The research also connects the use of normalization to translators’ ability to manage fewer pragmatic markers and fillers, and links simplification to experience in handling personal pronouns.

These findings from psycholinguistic and neurolinguistic studies have not only broadened our understanding of the causes behind translation universals, but also revolutionized the methodologies employed in exploring these universals within translation studies.

2.3 Research Design

The research design in studying universal features of translation has evolved significantly, moving from unifactorial to multifactorial approaches. Early corpus-assisted studies of translation universals, such as those by Øverås (1998), Olohan (2003), and Ke (2005), primarily employed unifactorial designs that only involve single explanatory factors, such as translatorship and translation status. Recent developments in psycholinguistics and computational linguistics, however, have led to the adoption of multifactorial research designs. These designs combine psycholinguistic experiments with corpus analysis, revealing additional explanatory factors like bilingual experience and language proficiency that affect universal features, as demonstrated in studies by Hvelplund (2017), Zasiekin (2019), and Gumul (2021). Furthermore, incorporating computational techniques like entropy and principal component analyses into corpus studies (e.g., Liu, Liu, and Lei 2022; Luo and Li 2022) has verified the presence of universals like normalization and simplification in both directions of English-Chinese machine translation.

2.4 Discussion and Critique

Although significant strides have been made in the study of translation universals, there are still several gaps in research that need to be addressed. One of the primary challenges is the varying definitions and interpretations of universal features such as explicitation and leveling-out. This inconsistency makes it difficult to establish consistent criteria for identifying and categorizing these features in translation. For instance, some studies (e.g., De Metsenaere 2016; Kamenická 2007; Olohan and Baker 2000; Saldanha 2008) follow different interpretations, despite ostensibly utilizing the same definitions. This poses a challenge, as scholars believe they analyze identical concepts when in fact their notions diverge significantly. Moreover, most extant definitions lack concrete guidelines for determining the existence of these features in translation. What one person considers explicit, implicit, or leveled-out may not be perceived as such by another. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a shared understanding of these universal features in future research, not only as theoretical concepts, but as operational criteria in analysis.

Secondly, many classifications of specific translation universals lack clarity and operationality. For instance, Becher (2011, 90) acknowledged that his classification of explicitation was only applicable to his study of German-English bidirectional translation of business texts. Thus, classifications in prior research may not be applicable for analyzing translation universals in new contexts. To enable broad applicability, future attempts should focus on developing elaborate yet distinct, systematic classifications.

Thirdly, the quest to establish the universality of translation universals runs the risk of becoming an endless pursuit without definitive conclusions, primarily due to the absolute conceptualization of these universal features. By framing these features in absolute terms, it becomes challenging to assert their comprehensive applicability to all translation scenarios, which may prove impractical or even impossible, despite ongoing confirmatory research. Therefore, it could be beneficial to reframe universals as tendencies characterized by varying degrees of probability, rather than as unchangeable absolutes. This shift in perspective would allow for greater flexibility in demonstrating general patterns.

Fourthly, current studies of translation universals lack a concern for such human agents as translators and readers in translation. Recognizing translation as a fundamentally human activity (Toury 1980, 79–81), future studies should adopt multifactorial research designs that consider various factors influencing translation outcomes. Utilizing both experimental and non-experimental methods to focus on human participants can yield deeper insights into the root causes of universal translation features. Incorporating multifactorial designs in future research on translation universals can also provide new perspectives and contribute to a better understanding of definitions, classifications, and causes of these features.

3 Translator Style

Translation studies has long focused on the understanding and identification of translator style, a pursuit that highlights translators’ subjectivity and visibility (Venuti 2012, 393). Despite the concept of translator style is “notoriously difficult to define” (Li 2016, 103), the advent of CTS has enabled researchers to explore this concept using corpus methodologies and evidence.

Baker (2000) made a pivotal contribution by using corpora to analyze stylistic indices such as STTR (Standardized Type-Token Ratio), average sentence length, and the frequency of the report verb SAY in different translations by Peter Clark and Peter Bush. Her objective was to determine if these translators left distinct “thumbprints” in their target texts that were independent of the source texts. Baker’s work is notable for introducing a corpus-linguistic approach to studying translator style, defining it as consistent linguistic choices in target texts irrespective of source texts.

Following Baker’s work, various studies have used corpora to examine translator style, employing different methodologies. Olohan (2003), Saldanha (2011), and Li (2016) have focused on target texts, often comparing with a reference corpus of non-translated texts in the same language/genre to identify translators’ “thumbprints”. Conversely, Boase-Beier (2006); Malmkjær (2003); Winters (2004) have analyzed both source and target texts to explore how translators transfer various linguistic features from source texts into target texts. These studies have enhanced our understanding of translator style from both source-oriented and target-oriented perspectives, though not without limitations.

3.1 TT-Oriented Studies

TT-oriented studies compare stylistic features of translations from one translator with those of another or with a reference corpus of non-translated texts in the same language and genre. These studies (e.g., Baker 2000; Olohan 2004; Saldanha 2011) use comparable corpora and focus exclusively on target texts, particularly formal linguistic features and their statistics (e.g., STTR, average sentence length). These studies can encompass translations from either the same or different source texts, considering factors such as language and genre. When the source text is the same, this analysis approach is referred to as the “one-to-many” mode. On the other hand, when the source texts vary, it is known as the “many-to-many” mode. These modes allow for a comprehensive examination of translation patterns and variations across different source texts and translators.

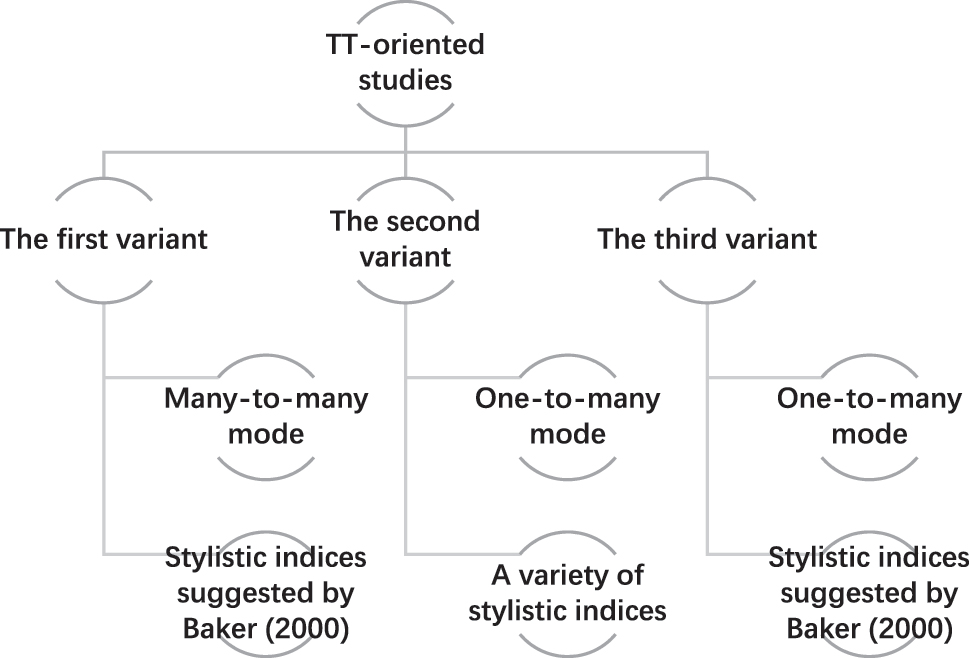

TT-oriented studies (e.g., Li, He, and Hou 2018; Li, Zhang, and Liu 2011; Yan 2015) often compare the styles of different translators working on the same or diverse source texts. In these cases, a translated text or a non-translated text corpus serves as a benchmark for assessing the styles of one or several translators. However, TT-oriented studies vary, especially in their corpus design and the selection of stylistic indices to represent translator style. As a result, three variants of TT-oriented studies have been identified, as depicted in Figure 2.

Variants of TT-oriented studies of translator style.

The first variant (TV-I) adopts the many-to-many mode and investigates translator style through the stylistic indices suggested by Baker (2000), STTR (standardized type-token ratio), average sentence length, and reporting verbs (e.g., say, tell). Such studies (e.g., Baker 2000; Saldanha 2011) compare translators’ styles across multiple translations of source texts which may differ in languages and/or genres with those of other translators. This comparison is made by extracting and analyzing the stylistic indices through comparable corpora. The main goal of such studies is to determine whether translators leave distinct thumbprints in their translations.

The second variant (TV-II) examines translator style using a broader range of formal stylistic indices, including those used in TV-I studies. Adopting the one-to-many mode, TV-II studies analyze various stylistic indices (e.g., STTR, reporting verbs, contractions, italics) to reveal translator style. This approach offers greater flexibility in the selection of stylistic indices. TV-II studies (e.g., Mastropierro 2018; Wang and Li 2020) seek to uncover stylistic differences between translators working on the same source text and to investigate sociocultural factors leading to these differences.

The third variant (TV-III) bridges TV-I and TV-II studies. TV-III studies tend to use the indices initially proposed by Baker, as in TV-I studies, but adopt the one-to-many mode of analysis found in TV-II studies. Consequently, despite using the same stylistic indices, TV-III studies (e.g., Li 2016; Olohan 2004) differ from TV-I studies because of different modes of analysis. TV-III studies also differ from TV-II studies in terms of the range of stylistic indices adopted, although both employ the one-to-many mode in their analysis.

3.2 ST-Oriented Studies

ST-oriented studies delve into the exploration of how translators transfer stylistic features from source texts to target texts. These studies aim to examine the variations in this transfer process among different translators. By analyzing the stylistic choices made by translators, researchers can gain insights into their individual approaches and preferences, shedding light on the diverse ways in which stylistic features are handled in translation. In the single mode, a single parallel corpus is used, consisting of a source text and multiple target texts. Researchers analyze and compare linguistic features, such as contractions, italics, and discourse presentation, in the target texts resulting from translators’ choices. These features are examined in relation to both the source text and among the different target texts. This mode allows for an in-depth exploration of how translators handle specific stylistic features and the variations that arise in their translation choices.

In the multiple mode, two or more sets of parallel corpora are utilized, each containing a source text and its multiple target texts. Analysis and comparison can be conducted within each set of parallel corpora and/or across different sets. This mode enables researchers to examine and contrast the stylistic choices made by different translators working on similar or different source texts. By comparing translations from various translators, insights can be gained into the range of stylistic approaches and variations in the transfer of stylistic features.

Many ST-oriented studies (e.g., Huang 2014; Munday 2008; Winters 2013) have compared how translators handled linguistic features in source texts and examined the resulting diversities in target texts. Similar to TT-oriented studies, ST-oriented studies also differ in the selection of stylistic indices that represent translator style. However, these differences primarily arise from the quality of the chosen stylistic indices (e.g., formal, functional), rather than the quantity or number of indices used. Consequently, there are two variants in ST-oriented studies (Figure 3).

Variants of ST-oriented studies of translator style.

The first variant (SV-I) focuses on how translators handle formal stylistic features (e.g., lexical and syntactic features) of the source text in their translations. SV-I studies establish a set of formal linguistic features from the source text as a benchmark to evaluate how translators reproduce these features. Deviations in these features in the target texts, compared to the source text, are seen as indicators of the translator’s style. Beyond analyzing these deviations, some SV-I studies (e.g., Chen and Li 2023; Liu and Afzaal 2021; Munday 2008) also explore stylistic differences between translators working on the same source text and consider various sociocultural factors contributing to these differences.

The second variant (SV-II) examines how translators interpret and translate literary functions (e.g., viewpoints, ironic effects) from the source text. Unlike SV-I, SV-II studies go beyond formal linguistic features and delve into the management of literary functions associated with these features in translation. These studies aim to understand how translators handle the stylistic nuances and literary effects present in the source text and how they are transferred to the target text. This approach, moving towards the functional aspects of translator style, deviates constructively from Baker’s (2000) original proposition of using formal linguistic features to indicate style. However, some existing SV-II studies (e.g., Boase-Beier 2006; Huang 2014; Winter 2013) displayed a narrow focus on “smaller/local” literary functions while overlooking “bigger/global” functions in translation. While some studies have extensively examined aspects such as viewpoints and character speech, there is a need to consider the broader literary functions that contribute to the overall construction of meaning and the creation of fictional worlds. Thematic construction, characterization, and the creation of fictional worlds are crucial elements in literary texts. These functions shape the narrative structure, convey the author’s intended themes, develop the personalities of characters, and establish the immersive fictional setting. Understanding how these functions are managed in translation is essential for comprehending the translator’s role in conveying the larger literary vision of the source text.

3.3 Discussion and Critique

Corpus-assisted studies of translator style have made significant contributions to the field of translation studies. However, they also face certain limitations that should be taken into consideration.

Firstly, there is a notable emphasis on the formal rather than the functional aspects of translator style in existing studies, especially in literary translation. This focus creates a gap in connecting linguistic description with literary appreciation (Mahlberg 2013). To address this, employing corpus stylistic methods could be effective, as they consider both formal and functional aspects of style.

Secondly, the criteria for selecting stylistic indices in many TT- and ST-oriented studies are often unclear. This lack of clarity hinders the establishment of systematic connections between stylistic indices and complicates the comparison of findings across different translator style studies. Here again, corpus stylistic methods could aid in creating systematic connections and enabling comparability by bridging linguistic description and literary appreciation.

Thirdly, there is a scarcity of interest in diachronic research on translator style. Diachronic studies, which examine how a translator’s style evolves over time influenced by temporal and historical factors, could provide insights into the development of a translator’s style(s). This diachronic interest in translator style research would also partly contribute to understanding the rationale behind specific translation choices by translators.

Fourthly, previous research has predominantly focused on literary texts like fiction, drama, and poetry, with less attention to non-literary texts such as journalistic reports, academic works, and business documents. This oversight leaves many questions about translator style in non-literary contexts unanswered. For instance, it is unclear if there are stylistic differences in the translation of literary versus non-literary texts by the same translator, or if stylistic indices used in literary contexts are applicable to non-literary translation contexts. Addressing these questions would significantly broaden our existing understanding of translator style.

4 Translation Norms

Chesterman (2013, 1) defines translation norms as the implicit rules and mechanisms that guide translatorial behavior and shape translation products. These norms, encompassing a range of principles and conventions, emerge from specific social, cultural, political, and historical contexts, and significantly influence translators’ decision-making (Munday 2012). Investigating translation norms across various cultures and historical periods is critical. This includes analyzing recurring patterns in translated texts, which is key to uncovering universal laws of translation (Schaffner 2007, xi). Scholars have developed different categorizations for translation norms to support this research. For instance, Toury (1995) proposed three categories: preliminary norms, initial norms, and operational norms. Similarly, Chesterman (1997) differentiated between “expectancy” norms and “professional” norms. These theoretical categorizations have provided a foundation for subsequent corpus-assisted studies of translation norms.

4.1 Identification and Generalization

Recent corpus-assisted research on translation norms has predominantly focused on both product-oriented and function-oriented descriptive studies. However, there have been only a limited number of studies employing corpora to explore translation norms, mainly concentrating on identifying and generalizing norms across various genres in bidirectional translations between English and different Asian languages. For example, Wen and van Heuven (2017) investigated the relationship between translation ambiguity, word frequency, and concreteness in Chinese translations of English words. Hu (2020) explored the negotiation and formation of translation norms within Chinese business contexts. Lee et al. (2022) examined potential norms in Malay-English translation by proficient Malay-English bilinguals, highlighting the impact of lexical characteristics on translation ambiguity.

These studies have provided insights into translation norms between English and Asian languages, offering a rich resource for bilingual language research involving these languages. Notably, these studies share a multifactorial research design that combines corpora with experimental methods. The multifactorial design is useful because it allows for a more comprehensive exploration of translation norms from various perspectives and facilitates the triangulation of results. Such triangulation is instrumental in uncovering and generalizing unique translation norms specific to different language pairs.

4.2 Discussion and Critique

While corpora have proven to be valuable tools for studying translation norms, their application in this area is not as developed or comprehensive as in other fields of corpus-assisted translation studies, such as studies of translation universals and translator style research.

Firstly, many current studies (e.g., Hu 2020; Wen and van Heuven 2017) have a limited research scope, primarily focusing on identifying and verifying Toury’s operational norms across different language pairs. The broader generalization of preliminary or initial norms is often neglected. Toury (1995) views translation norms as sociocultural phenomena, suggesting that their study requires more emphasis on sociocultural contexts, rather than just translation products. This limitation may be due to the fact that the current corpus tools used in translation studies, such as AntConc, Wordsmith, and Wmatrix, have limitations in capturing aspects beyond linguistic forms. These tools primarily focus on analyzing linguistic features, such as word frequency, collocations, or syntactic patterns. While these analyses provide valuable insights into the linguistic aspects of translation, they may not capture the full range of extra-linguistic elements that shape translation norms, thus making it difficult to analyze extra-linguistic elements of translation norms.

Secondly, there is a scarcity of diachronic studies in this area. While most corpus-assisted studies (e.g., Dai 2016; Hu 2020; Lee et al. 2022) on translation norms are synchronic, only a few (for instance, Xia 2014) have examined changes in translation norms over time. These diachronic studies often cover relatively short time spans, likely due to difficulties in accessing older manuscripts, resulting in a partial understanding of how translation norms evolve over longer periods of time.

Thirdly, corpus designs in translation norm studies typically exclude translators’ personal perspectives and experiences. This omission is problematic, considering that translators play a crucial role in shaping translation norms. For CTS aimed at capturing translation norms, it is essential to incorporate factors like translators’ stances, identities, and genders into the corpus design to provide a holistic and more balanced understanding of how translation norms are formed and influenced.

5 Translation Pedagogy

Laviosa and Falco (2021) expanded the scope of applied translation studies in Holmes’s map of DTS by introducing translation pedagogy as a distinct branch. This reconfiguration acknowledges translation in language teaching as a legitimate research area in its own right (Laviosa and Falco 2021, 9). Historically, research in translation pedagogy has been limited by the lack of effective methodologies and tools, often depending on the intuition and experience of researchers (Hu 2011, 178). However, since 1997, when the importance of corpus-assisted translator training was highlighted at the conference Corpus Use and Learning to Translate, there has been a growing focus on corpus-assisted approaches in this field. Scholars like Zanettin (1998), Bowker (2001), Pan and Laviosa (2023) argue that corpus-assisted pedagogical practices in translation have several benefits. They are data-driven and discovery-oriented, providing students with practical insights into translation skills and aiding in the enhancement of their translation competence. To date, corpus-assisted studies in translation pedagogy have primarily concentrated on areas such as translator training, translation quality assessment, and textbook compilation. These areas represent respectively the process, feedback, and resources in translation pedagogy (see Figure 4).

The process, feedback, and means in translation pedagogy.

5.1 Translator Training

The integration of technological tools and expertise, such as corpus software, translation memory systems, and computer literacy, has facilitated the incorporation of corpora into translator training (Laviosa and Falco 2023). As a result, numerous translator training projects have emerged, such as Castagnoli (2018) and Biel and Leńko-Szymańska (2021), focusing on “corpus use for learning to translate” and “learning corpus use to translate” (Frérot 2016, 40). The central focus of corpus-assisted translator training lies in the use of corpora, which enhances bilingual proficiency, cross-cultural awareness, and technical expertise. Hu (2011, 190) identifies three types of corpora widely employed in translator training: parallel corpora, monolingual corpora, and comparable corpora.

Parallel corpora consist of written materials in language A and their corresponding translations in language B (Zanettin 1998, 177–178). They serve as valuable tools for translation trainees to enhance their understanding of a translated language, as they demonstrate how professional translators convey the meaning and usage of a source text in translation (Bluemel 2019, 83). However, parallel corpora face limitations in terms of accessible bilingual concordance software and the availability of parallel texts for training purposes. Consequently, recent training projects, such as Kübler, Mestivier, and Pecman (2018), Torres-Simón and Pym (2019), and Granger and Lefer (2020), have focused more on monolingual and comparable corpora, as they are more readily available.

A monolingual corpus is a collection of written or spoken texts in a single language, which can be analyzed to gain insights into language usage (Mikhailov 2022, 226). In translator training, monolingual corpora can be either in the source language or the target language. Recent projects, such as Ramos (2016), Neshkovska (2019), and Mikhailov (2022), have demonstrated the usefulness of monolingual corpora in developing translation skills. By studying monolingual corpora containing different translations of the same source text, trainees can identify patterns, structures, and various translation interpretations. This helps them develop their own strategies and techniques, refining their skills through feedback. However, monolingual corpora have limitations in providing language resources for translated or non-translated languages. Therefore, comparable corpora are often used alongside monolingual corpora to enhance their effectiveness.

Comparable corpora in translator training refer to collections of texts in language A and language B that share similarities in subject matter or other relevant characteristics (Liu 2020; 21). This conceptualization of comparable corpora differs from that used in translation studies, which refer to a principled collection of translated and non-translated texts in the same language. Comparable corpora serve as valuable resources for training translators, bridging the gap between monolingual and parallel corpora (Bernardini 2003; 529). They offer advantages such as simpler corpus construction processes and a greater abundance of language resources for training. However, a limitation of comparable corpora is that they involve only one language, either the source or target language. Therefore, effective translator training requires the combined use of all three types of corpora to maximize their benefits and minimize limitations.

5.2 Translation Quality Assessment

The use of the three types of corpora in translator training not only helps develop trainees’ linguistic competence, but also serves as powerful tools for evaluating the quality of their translations. Previous corpus-assisted assessments of translation quality have identified two major approaches: the user-driven approach and the feature-driven approach (De Sutter et al. 2017, 26). Both approaches agree on using non-translated original texts as benchmarks for measuring the quality of translated texts (Hassani 2011, 352).

The user-driven approach evaluates the appropriateness of specific words and expressions in translated texts, using assessment corpora. Its objective is not to measure the overall appropriateness of a trainee’s translation, but rather to provide translation instructors and trainees with a tool for evaluating the suitability of certain words and structures in a specific translation. Studies adopting the user-driven approach, such as Bowker (2001), Pearson (2003), Hassani (2011), and Frankenberg-Garcia (2015), have shown that incorporating diverse types of assessment corpora (e.g., parallel, monolingual, comparable) enhances evaluators’ ability to detect errors in trainees’ translations and evaluate their suitability across different linguistic contexts and text genres. These studies have also demonstrated that evaluators using corpus-assisted methods in translation quality assessment tend to have higher levels of confidence in their feedback, which trainees perceive as more reliable.

On the other hand, the feature-driven approach evaluates the overall quality of translated texts by quantifying one or more pre-selected formal linguistic features (e.g., average sentence length, lexical density) considered relevant to the translation task. Studies adopting this approach, such as Xiao (2010), Cappelle (2012), Cappelle and Loock (2017), and Wurm (2020), assess the quality of translated texts across different genres by quantifying deviations in these linguistic features. They suggest a connection between translation quality and linguistic similarities between the original and translated texts, known as linguistic homogenization (Loock and O’Connor 2013). Specifically, an under or over-representation of a particular linguistic feature may indicate a violation of usage restrictions, resulting in less desirable translation quality (Loock and O’Connor 2013, 3). Therefore, according to the feature-driven approach, satisfactory translations are often characterized by linguistic homogenization, aiming for linguistic coherence and consistency between the source and target languages.

5.3 Textbooks Compilation for Translation Practices

Practices-oriented textbooks play a crucial role in translator training and serve as important indicators for evaluating teaching effectiveness (Hu 2011, 186). The incorporation of corpora in textbook compilation for translation practices has been explored in previous corpus-assisted studies, focusing on two main issues: the selection of bilingual examples and the design of translation exercises (Hu 2011; Kolahi, Khanmohammad, and Shirvani 2013; Siregar 2019; Stewart 2011; Tao 2016). These studies have identified two advantages of using corpora in textbook compilation.

Firstly, corpora provide textbook compilers with a vast collection of authentic bilingual materials for practice and research purposes. Compilers can include bilingual texts from diverse sources (e.g., newspapers, academic journals, social media) in the textbooks to demonstrate proper terminology, expressions, and linguistic features in translation. This exposure helps trainees understand cultural nuances and contextual influences on language use (Tao 2005, 191). Furthermore, corpora enable compilers to analyze language usage patterns, identifying common errors made by trainees in the target language. This analysis informs the creation of targeted exercises to address these errors and improve trainees’ language skills (Siregar 2019, 74). Additionally, corpora facilitate research into the challenges faced by translators and the effectiveness of various translation strategies and techniques. This support enhances the quality of translator training and informs the use of corpus tools and translation memory systems, including Wordsmith, Trados, and OmegaT.

Secondly, the use of corpora reduces the reliance on personal intuitions and experiences of textbook compilers when selecting demonstration examples and exercise tasks. Traditionally, compilers have relied on their own knowledge and experience, which may be biased and limited in reflecting real-world language use and variability in translation tasks (Tao 2016, 213). In contrast, corpora allow for a data-driven approach to selecting examples and exercises from a diverse collection of real-world language materials. This would help translation trainees learn language usage patterns in diverse linguistic and cultural contexts (Hu 2011, 188). Moreover, the use of corpora facilitates an evidence-based evaluation of the effectiveness of different translation strategies and techniques in producing appropriate translations. This evaluation informs the design of training textbooks aimed at improving trainees’ translation skills.

5.4 Discussion and Critique

Despite the effectiveness of corpora in translation pedagogy, some potential gaps remain in the field.

Firstly, the application of corpora in training programs has not been sufficiently tailored to meet diverse professional needs. Many corpus-assisted projects focus primarily on developing linguistic competence, often overlooking the specific professional requirements of trainees. Hennessy (2011) identified various types of translators in the industry, including professionals in governmental or corporate settings, freelance translators, and employees who translate occasionally. Therefore, it is crucial that the selection and design of corpora in training programs reflect these diverse professional demands, ensuring trainees acquire both linguistic and technological skills relevant to their future careers.

Secondly, the feature-driven approach to translation quality assessment is limited due to its over-reliance on frequency. Typically, such studies evaluate translation quality by comparing the frequency of certain linguistic features in a translation with those in a corpus of non-translated texts. This approach uses frequency patterns in non-translated texts as benchmarks, deviating from the descriptive nature of CTS. As Baker (1993, 33) notes, overuse and underuse in translations are descriptive terms and do not necessarily indicate quality issues. Thus, relying solely on frequency as a measure of quality can be problematic.

Thirdly, research on translation textbooks and their compilation lacks systematic investigation models. While studies have evolved from subjective assessments to more empirical approaches (Tao 2016, 215), there is still a need for models that systematically link textbooks with their participants (e.g., teachers, students), processes (e.g., publishing, compilation), and contexts (e.g., educational/training policies, objectives). Such models are vital as they can illuminate the societal functions of translation textbooks, offering insights into their roles and impacts in the broader context of translation education.

6 Future Research

Despite the advances in corpus-assisted translation studies over the past two decades, many studies have been constrained by monofactorial research designs, limited methodologies, and a lack of integration with other disciplines (De Sutter and Lefer 2020, 6). To overcome these limitations, De Sutter and Lefer (2020) propose a new research agenda for CTS, emphasizing multifactorial research designs, methodological pluralism, and interdisciplinarity.

This article proposes two analysis modes for operationalizing the new agenda within corpus-assisted translation studies. The first analysis mode (Mode I), narrower in methodology and scope, utilizes corpus methodologies like frequency comparison and concordance analysis to examine translation products. The second analysis mode (Mode II), broader in both methodology and scope, employs various methodologies, both corpus-based and non-corpus-based, to analyze the products, processes, participants, and contexts in translation practices. It is evident that while both modes of analysis seek to advance CTS through multifactorial designs, methodological pluralism, and interdisciplinarity, they differ in method and scope. Mode I, employing corpus methodologies, is limited to studying translation products. In contrast, Mode II encompasses a broader range, utilizing methods from various disciplines like linguistics, cognitive sciences, and sociology, to explore translation products, processes, participants, and contexts. It is crucial to emphasize that the classification of the two analysis modes in this article is provisional, ad hoc, and open to refinement in future studies. Considering their strong association with CTS, there might be some overlap between these modes. Hence, the primary purpose of the current classification is to provide clarity and identify promising avenues for future research within the realm of CTS.

In the following sections, this article will explore numerous potential applications of Modes I and II analyses in the context of CTS. These applications encompass a wide range of interdisciplinary fields, including critical discourse analysis, cognitive analysis, and conceptual analysis.

6.1 Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) in translation investigates social elements (e.g., power relations, ideologies, social identities) and translation elements (e.g., translation strategies, translation participants) in translated texts. With the rise of CTS, the use of corpora in this interdisciplinary field has become essential, facilitating efficient analysis of social and translation elements.

However, the majority of critical discourse analyses within CTS predominantly focus on power relations and ideologies represented in translation products, aligning primarily with Mode I analysis. For instance, several analyses have employed corpus methods to investigate social elements like power relations (e.g., Kim 2017; Pan and Li 2021) and ideologies (e.g., Caimotto Cristina and Gaspari 2018; Kim 2014; Pan and Li 2021) in translated texts. Consequently, these studies often fail to comprehensively uncover key translation elements that demonstrate the interplay between translation and discourse, especially through corpus-based explorations of translation products.

To carry out further research in this area, we propose undertaking Mode II analyses in order to focus on examining participants, including translators and readers, who are involved in both producing and evaluating translated discourse. Specifically, we suggest exploring translators’ styles and readers’ receptions as two potential areas for Mode II analyses in CDA. Corpus-assisted CDA of translators’ styles uncovers possible ideological components and power relations that shape translators’ stylistic idiosyncrasies. Similarly, corpus-assisted CDA of readers’ reception interprets their feedback using corpus data, thereby facilitating reception studies of translated works by illustrating potential ideological components in these responses.

The proposed Mode II analyses have the following advantages. Firstly, they enable multifactorial research designs by incorporating both products (i.e., translated discourse) and participants (i.e., translators and readers) as focal points in corpus-assisted Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of translation. Secondly, they help us systematically understand potential factors contributing to translators’ styles and readers’ reception through CDA frameworks.

6.2 Cognitive Analysis

Cognitive analyses in translation focus on human cognition in the products, processes, participants, and contexts of translation practices (Martín 2017, 555). To apply De Sutter and Lefer (2020) new agenda to CTS, we can investigate human cognition through both Mode I and Mode II analyses.

In Mode I analysis, we utilize corpus-assisted methods to explore linguistic elements in translated texts that involve human cognition. For example, when examining translators’ styles, we can focus on how they handle rhetorical devices like metaphor, metonymy, and synecdoche, all requiring cognitive processing in translation. Similarly, when exploring translation universals, we can study the connections between the translation of cognition-required rhetorical devices and the occurrence of universal features. Additionally, when investigating translation norms, we can concentrate on regular patterns in the translation of these rhetorical devices and generalize relevant translation norms based on these patterns.

In Mode II analysis, we can undertake a range of experiments to explore various aspects of cognition, such as cognitive load, working memory, and schema, within both pure and applied CTS. This is because these cognitive aspects can provide insights into the participants in translation practices from the perspective of translation processes. For instance, in pure CTS, when searching for translation universals, experiments can reveal the cognitive mechanisms behind them by studying translators’ brain activities during translation since “universals can be traced back to human cognition” (Laviosa 2010, 4). Similarly, in studies of translators’ styles, we can conduct experiments to explore cognitive factors (e.g., memory, attention) that influence a translator’s style(s) across different translations to deepen our understanding of this translatorial phenomenon.

In applied CTS, cognitive analyses also hold practical value. This is particularly the case in corpus-assisted translator training, where trainees’ performances can be traced through a series of experiments on how their brains work in the process, using such tools as eye-tracking, MRI, and EEG. Data retrieved from the cognitive analyses may offer valuable feedbacks on the corpus-assisted training, which in turn could optimize syllabi designs for the training. Moreover, in corpus-assisted translation quality assessment, we can design cognitive experiments that track processes of assessment based on these tools (e.g., eye-tracking, EEG, MRI) to unveil important cognitive activities/patterns inside the evaluators’ brains.

Overall, conducting cognitive analyses in CTS offers two advantages. Firstly, it facilitates interdisciplinarity by using analytical frameworks and experimental tools from cognitive sciences to study translation processes. This aligns well with the new agenda’s multi-methodological approach. Secondly, the multi-methodological approach, supported by cognitive evidence, provides diverse perspectives to CTS. This is consistent with the multifactorial design suggested by the new agenda.

6.3 Conceptual Analysis

Conceptual analysis investigates different social and political concepts (e.g., legalization, feminism, contraception) across disciplines such as sociology, translation studies, and digital humanities (Baker 2022). In CTS, conceptual analysis can be a useful tool for exploring the contexts of translation. Similar to critical discourse analysis and cognitive analysis, Mode I and II conceptual analyses advance CTS by incorporating multiple factors and methodologies.

Mode I conceptual analysis examines social, cultural, and political concepts in translated texts (translation products), using corpus methods such as concordance analysis, categorization of semantic domains, and analysis of semantic prosodies. Specifically, we can focus on intersubjective constructs (e.g., bias, risk, democracy) that are created and conveyed through language, and investigate how they are represented in (translated) texts using corpus-assisted approaches.

Mode II conceptual analysis explores key concepts (e.g., faithfulness, visibility, linguistic homogenization) that are related to the products, participants, processes, and contexts in corpus-assisted translation practices, such as translator training, translation quality assessment, and post-editing. To investigate these concepts, corpus methods (e.g., concordance analysis, analysis of semantic prosodies) and/or non-corpus methods (e.g., interviews, experiments) can be employed.

Overall, the two modes of conceptual analysis bring benefits to CTS. Firstly, Mode I conceptual analysis facilitates multifactorial research in CTS by shifting the research focus from formal linguistic features (e.g., STTR, frequency of occurrences) to concept-based functions (i.e., social, cultural, political concepts) conveyed in these linguistic features. Secondly, Mode II conceptual analysis reveals new concepts, ideas, and perspectives emerging from all types of pure and applied CTS, offering innovative perspectives that may advance existing CTS.

7 Conclusions

This comprehensive exploration of CTS spanning the last two decades has shed light on both the progress made and the gaps that still exist within the field. While research areas such as translation universals, translator style, translation norms, and translation pedagogy have seen significant advancements, there are crucial aspects that demand immediate attention. One such neglected area is the functional aspect of translator style research. By exploring how translators adapt their style to various literary contexts, researchers can bridge the gap between linguistic description and literary appreciation, unraveling new dimensions of translation practice.

The misalignment between translation training programs and professional requirements poses another pressing challenge. To equip future translators with the necessary skills, it is imperative for training programs to evolve in sync with the rapidly changing demands of the translation industry. Incorporating real-world translation projects and internships, as well as fostering collaborations between academia and industry stakeholders, will ensure that training programs remain relevant and effective.

To propel CTS forward, De Sutter and Lefer’s (2020) research agenda calls for multifactorial designs, methodological pluralism, and interdisciplinarity. By integrating diverse methodologies and approaches from various disciplines, such as critical discourse analysis, cognitive analysis, and conceptual analysis, researchers can unlock new insights and deepen our understanding of translation phenomena. We believe that by embracing the proposed research agenda and addressing the identified gaps, we can shape a dynamic and vibrant field that not only meets the challenges of today but also paves the way for future discoveries and advancements in corpus-assisted translation studies.

References

Baker, Mona. 1993. “Corpus Linguistics and Translation Studies: Implications and Applications.” In Text and Technology: In Honour of John Sinclair, edited by M. Baker, G. Francis, and E. Tognini-Bonelli, 233–50. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.64.15bakSearch in Google Scholar

Baker, Mona. 2000. “Towards a Methodology for Investigating the Style of a Literary Translator.” Target 12 (2): 241–66. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.12.2.04bak.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Mona. 2022 In preparation. “From Linguistic to Conceptual to Narrative Analysis: A Provisional Outline for a New Research Agenda for Corpus-Based Translation Studies.” Talk by Mona Baker.Search in Google Scholar

Baumgarten, Nicole, Bernd Meyer, and Demet Özçetin. 2008. “Explicitness in Translation and Interpreting: A Critical Review and Some Empirical Evidence (Of an Elusive Concept).” Across Languages and Cultures 9 (2): 177–203. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.9.2008.2.2.Search in Google Scholar

Becher, Viktor. 2011. “Explicitation and Implicitation in Business Translation: A Corpus-Based Study of English-German and German-English Translations of Business Texts.” PhD dissertation, University of Hamburg.Search in Google Scholar

Bernardini, Silvia. 2003. “Designing a corpus for translation and language teaching: The CEXI experience.” Tesol Quarterly 37 (3): 528–537.10.2307/3588403Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, and Randi Reppen. 2015. The Cambridge Handbook of English Corpus Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139764377Search in Google Scholar

Biel, Łucja, and Agnieszka Leńko-Szymańska. 2021. “Terminological Collocations in Trainee Legal Translations: A Learner-Corpus Study of L2 Company Law Translations.” In Using Corpora in Contrastive and Translation Studies Conference, edited by Sara Castagnoli, Ksenia Balakina, Silvia Bernardini, Erika Dalan, Ester Dolei, Adriano Ferraresi, Maja Petrović, and Maria Russo, 6th ed., 12–4. Bertinoro: UCCTS-6.Search in Google Scholar

Bluemel, Brody. 2019. “Pedagogical applications of Chinese parallel corpora.” Computational and Corpus Approaches to Chinese Language Learning 23: 81–98.10.1007/978-981-13-3570-9_5Search in Google Scholar

Boase-Beier, Jean. 2006. Stylistic Approaches to Translation. Manchester: St Jerome Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Bowker, Lynne. 2001. “Towards a Methodology for a Corpus-Based Approach to Translation Evaluation.” Meta 46 (2): 345–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/002135ar.Search in Google Scholar

Caimotto Cristina, Maria, and Federico Gaspari. 2018. “Corpus-Based Study of News Translation: Challenges and Possibilities.” Across Languages and Cultures 19 (2): 205–20. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2018.19.2.4.Search in Google Scholar

Cappelle, Bert. 2012. “English Is Less Rich in Manner-Of-Motion Verbs when Translated from French.” Across Languages and Cultures 13 (2): 173–95. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.13.2012.2.3.Search in Google Scholar

Cappelle, Bert, and Rudy Loock. 2017. “Typological Differences Shining through: The Case of Phrasal Verbs in Translated English.” In Empirical Translation Studies: New Theoretical and Methodological Traditions, 235–63. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110459586-009Search in Google Scholar

Castagnoli, Sara. 2018. “Translation Choices Compared: Investigating Translation Variation in a Learner Translation Corpus.” In CECL Papers, 36–7. Louvain-la-Neuve: Centre for English Corpus Linguistics: Université catholique de Louvain.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Fengde, and Defeng Li. 2023. “Patronage and Ideology: A Corpus-Assisted Investigation of Eileen Chang’s Style of Translating Herself and the Other.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 38 (1): 34–49.10.1093/llc/fqac015Search in Google Scholar

Chesterman, Andrew. 1997. Memes of Translation: The Spread of Ideas in Translation Theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/btl.22Search in Google Scholar

Chesterman, Andrew. 2010. “Why Study Translation Universals.” Acta Translatologica Helsingiensia 1: 38–48.Search in Google Scholar

Chesterman, Andrew. 2013. “Models of what Processes? Translation and Interpreting Studies.” The Journal of the American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association 8 (2): 155–68. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.8.2.02che.Search in Google Scholar

Cuéllar, Sergio Bolaños. 2002. “Equivalence Revisited: A Key Concept in Modern Translation Theory.” Forma y Función 15: 60–88.Search in Google Scholar

Dai, Guangrong. 2016. Hybridity in Translated Chinese. Singapore: New Frontiers in Translation Studies.10.1007/978-981-10-0742-2Search in Google Scholar

De Metsenaere, Hinde. 2016. “Explicitation and Implicitation of Dutch and German Nominal Compounds in Translated Fiction and Non-fiction.” In Translation and Cognition Symposium. Germersheim: Universiteit Gent.10.1515/les-2016-0006Search in Google Scholar

De Sutter, Gert, Bert Cappelle, Orphée Clercq, Rudy Loock, and Koen Plevoets. 2017. “Towards a corpus-based, statistical approach to translation quality: Measuring and visualizing linguistic deviance in student translations.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 16: 1–14.10.52034/lanstts.v16i0.440Search in Google Scholar

De Sutter, Gert, and Marie-Aude Lefer. 2020. “On the Need for a New Research Agenda for Corpus-Based Translation Studies: A Multi-Methodological, Multifactorial and Interdisciplinary Approach.” Perspectives 28 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2019.1611891.Search in Google Scholar

Frankenberg-Garcia, Ana. 2015. “Training Translators to Use Corpora Hands-On: Challenges and Reactions by a Group of Thirteen Students at a UK University.” Corpora 10 (3): 351–80. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2015.0081.Search in Google Scholar

Frawley, William, ed. 1984. Translation: Literary, Linguistic, and Philosophical Perspectives. Newark: University of Delaware Press; London: Associated University Presses.Search in Google Scholar

Frérot, Cécile. 2016. “Corpora and Corpus Technology for Translation Purposes in Professional and Academic Environments: Major Achievements and New Perspectives.” Cadernos de Tradução 36: 36–61. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7968.2016v36nesp1p36.Search in Google Scholar

Granger, Sylviane, and Marie-Aude Lefer. 2020. “The Multilingual Student Translation corpus: a resource for translation teaching and research.” Language Resources and Evaluation 54 (4): 1183–1199.10.1007/s10579-020-09485-6Search in Google Scholar

Gumul, Ewa. 2021. “Interpreters Who Explicate Talk More: On the Relationship between Explicating Styles and Retrospective Styles in Simultaneous Interpreting.” Perspectives 31: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2021.1991401.Search in Google Scholar

Hassani, Ghodrat. 2011. “A Corpus-Based Evaluation Approach to Translation Improvement.” Meta: Journal des traducteurs/Meta: Translators’ Journal 56 (2): 351–73. https://doi.org/10.7202/1006181ar.Search in Google Scholar

Hennessy, Eileen B. 2011. “Translator Training: The Need for New Directions.” Translation Journal 15 (1): 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Holmes, James S. 1972. “The Name and Nature of Translation Studies.” Translated 2: 67–80.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Bei. 2020. “How Are Translation Norms Negotiated? A Case Study of Risk Management in Chinese Institutional Translation.” Target: International Journal of Translation Studies 32 (1): 83–122. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19050.hu.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Kaibao. 2011. Introduction to Corpus Translation Studies. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Libo. 2014. “Translation of Narrative Discourse in Three English Versions of Rickshaw Boy: A Corpus-Based Study of Translator Style.” Journal of the PLA University of Foreign Languages 37 (1): 72–80.Search in Google Scholar

Hvelplund, Kristian T. 2017. “Four Fundamental Types of Reading during Translation.” In Translation in Transition: Between Cognition, Computing and Technology, 55–77. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/btl.133.02hveSearch in Google Scholar

Kajzer-Wietrzny, Marta. 2015. “Simplification in Interpreting and Translation.” Across Languages and Cultures 16 (2): 233–55. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2015.16.2.5.Search in Google Scholar

Kamenická, Renata. 2007. “Defining Explicitation in Translation.” Brno Studies in English 33: 46–57.Search in Google Scholar

Ke, Fei. 2005. “Implicit and Explicit in Translation.” Foreign Language Teaching and Research: Foreign Languages and Literature 37 (4): 303–7.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Kyung Hye. 2014. “Examining US News Media Discourses about North Korea: A Corpus-Based Critical Discourse Analysis.” Discourse & Society 25 (2): 221–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926513516043.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Kyung Hye. 2017. “Newsweek Discourses on China and Their Korean Translations: A Corpus-Based Approach.” Discourse, Context & Media 15: 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2016.11.003.Search in Google Scholar

Klaudy, Kinga, and Krisztina Károly. 1998. “Implication in Translation: Empirical Evidence for Operational Asymmetry in Translation.” Across Languages and Cultures 6 (1): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.6.2005.1.2.Search in Google Scholar

Kolahi, Sholeh, Hajar Khanmohammad, and Elaheh Shirvani. 2013. “A Comparison of the Application of Readability Formulas in English Translation Textbooks and Their Translations.” International Journal of English Language Education 1 (1): 140–61. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijele.v1i1.2963.Search in Google Scholar

Kübler, Natalie, Alexandra Mestivier, and Mojca Pecman. 2018. “Teaching specialised translation through corpus linguistics: translation quality assessment and methodology evaluation and enhancement by experimental approach.” Meta 63 (3): 807–825.10.7202/1060174arSearch in Google Scholar

Laviosa, Sara. 2010. “Corpus-Based Translation Studies 15 Years On: Theory, Findings, Applications.” SYNAPS 24: 3–12.Search in Google Scholar

Laviosa, Sara, and Gaetano Falco. 2021. “Using Corpora in Translation Pedagogy.” In New Perspectives on Corpus Translation Studies, 3–27. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-4918-9_1Search in Google Scholar

Laviosa, Sara, and Gaetano Falco. 2023. “Corpora and Translator Education: Past, Present, and Future.” In Corpora and Translation Education, edited by J. Pan, and S. Laviosa. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-99-6589-2_2Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Soon Tat, Walter J. B. van Heuven, Jessica M. Price, and Christine Xiang Ru Leong. 2022. “Translation Norms for Malay and English Words: The Effects of Word Class, Semantic Variability, Lexical Characteristics, and Language Proficiency on Translation.” Behavior Research Methods 55: 1–17.10.3758/s13428-022-01977-3Search in Google Scholar

Li, Defeng, Chunling Zhang, and Kanglong Liu. 2011. “Translation Style and Ideology: A Corpus-Assisted Analysis of Two English Translations of Hongloumeng.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 26 (2): 153–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqr001.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Defeng. 2016. “Translator Style: A Corpus-Assisted Approach.” In Corpus Methodologies Explained, 113–46. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Defeng, He Wenzhao, and Hou Linping. 2018. “Research Aided by a Translation Style Corpus of Blue Shi-Ling.” Foreign Language Teaching 39 (1): 70–6.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Kanglong. 2020. Corpus-Assisted Translation Teaching: Issues and Challenges. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-15-8995-9Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Kanglong, and Muhammad Afzaal. 2021. “Translator’s Style through Lexical Bundles: A Corpus-Driven Analysis of Two English Translations of Hongloumeng.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 633422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633422.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Kanglong, Zhongzhu Liu, and Lei Lei. 2022. “Simplification in Translated Chinese: An Entropy-Based Approach.” Lingua 275: 103364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103364.Search in Google Scholar

Loock, Rudy, and Kathleen O’Connor. 2013. “The discourse functions of nonverbal appositives.” Journal of English Linguistics, 41 (4): 332–358.10.1177/0075424213502236Search in Google Scholar

Luo, Jinru, and Dechao Li. 2022. “Universals in Machine Translation? A Corpus-Based Study of Chinese-English Translations by WeChat Translate.” International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 27 (1): 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.19127.luo.Search in Google Scholar

Mahlberg, Michaela. 2013. Corpus stylistics and Dickens’s fiction. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203076088Search in Google Scholar

Malmkjær, Kristen. 2003. “What happened to God and the Angels: An Exercise in Translational Stylistics.” Target 15 (1): 37–58.10.1075/target.15.1.03malSearch in Google Scholar

Martín, Ricardo Muñoz. 2017. “Looking toward the Future of Cognitive Translation Studies.” In The Handbook of Translation and Cognition, edited by J. W. Schwieter, and A. Ferreira, 555–72. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.10.1002/9781119241485.ch30Search in Google Scholar

Mastropierro, Lorenzo. 2018. Corpus Stylistics in Heart of Darkness and Its Italian Translations. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

McCarthy, Michael, and Anne O’Keeffe. 2010. “Historical Perspective: What Are Corpora and How Have They Evolved?” In The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics, 3–13. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203856949-1Search in Google Scholar

Mikhailov, Mikhail. 2022. “Text Corpora, Professional Translators and Translator Training.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 16 (2): 224–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2021.2001955.Search in Google Scholar

Munday, Jeremy. 2008. Style and Ideology in Translation: Latin American Writing in English. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Munday, Jeremy. 2012. Evaluation in Translation: Critical Points of Translator Decision-Making. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Neshkovska, Silvana. 2019. “The Role of Electronic Corpora in Translation Training.” Studies in Linguistics, Culture, and FLT 7 (3): 48–58. https://doi.org/10.46687/silc.2019.v07.004.Search in Google Scholar

O’Brien, Sharon. 2015. “The Borrowers: Researching the Cognitive Aspects of Translation.” In Interdisciplinary in Translation and Interpreting Process Research, edited by M. Ehrensberger-Dow, S. Göpferich, and S. O’Brien, 5–17. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Olohan, Meave. 2004. Introducing Corpora in Translation Studies. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203640005Search in Google Scholar

Olohan, Maeve, and Mona Baker. 2000. “Reporting that in Translated English: Evidence for Subconscious Processes of Explicitation?” Across Languages and Cultures 1 (2): 141–58. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.1.2000.2.1.Search in Google Scholar

Olohan, Maeve. 2003. “How Frequent Are the Contractions? A Study of Contracted Forms in the Translational English Corpus.” Target 15 (1): 59–89. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.15.1.04olo.Search in Google Scholar

Øverås, Linn. 1998. “In Search of the Third Code: An Investigation of Norms in Literary Translation.” Meta 43 (4): 571–88.10.7202/003775arSearch in Google Scholar

Pan, Jun, and Sara Laviosa. 2023. Corpora and Translation Education: Advances and Challenges. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-99-6589-2Search in Google Scholar

Pan, Feng, and Tao Li. 2021. “The retranslation of Chinese political texts: Ideology, norms, and evolution.” Target 33 (3): 381–409.10.1075/target.20057.panSearch in Google Scholar

Pearson, Jennifer. 2003. “Using Parallel Texts in Translation Training Environment.” In Corpora in Translator Education, edited by Federico Zanettin, Silvia Bernardini, and Dominic Stewart, 15–24. Manchester: St. Jerome.Search in Google Scholar

Ramos, María Del Mar Sánchez. 2016. “Using Monolingual Virtual Corpora in Public Service Legal Translator Training.” In Technology-Enhanced Language Learning for Specialized Domains, 250–62. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315651729-32Search in Google Scholar

Saldanha, Gabriela. 2008. “Explicitation Revisited: Bringing the Reader into the Picture.” Trans-kom 1 (1): 20–35.Search in Google Scholar

Saldanha, Gabriela. 2011. “Translator Style: Methodological Considerations.” The Translator 17 (1): 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2011.10799478.Search in Google Scholar

Saldanha, Gabriela, and Sharon O’Brien. 2014. Research Methodologies in Translation Studies. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315760100Search in Google Scholar

Schäffner, Christina. 2007. Translation and Norms. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

Siregar, Masitowarni. 2019. “Model of Translation Textbook for Teaching English as Foreign Language (TEFL) Pedagogical Purpose.” SALTeL Journal (Southeast Asia Language Teaching and Learning) 2 (2): 72–82. https://doi.org/10.35307/saltel.v2i2.34.Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, Dominic. 2011. “Translation Textbooks: Translation into English as a Foreign Language.” Intralinea On Line Translation Journal 13: 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Szymor, Nina. 2018. “Translation: Universals or Cognition? A Usage-Based Perspective.” Target: International Journal of Translation Studies 30 (1): 53–86. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.15155.szy.Search in Google Scholar

Tang, Fang, and Dechao Li. 2016. “Explicitation Patterns in English-Chinese Consecutive Interpreting: Differences between Professional and Trainee Interpreters.” Perspectives 24 (2): 235–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2015.1040033.Search in Google Scholar

Tao, Youlan. 2005. “Translation Studies and Textbooks.” Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 13 (3): 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760508668991.Search in Google Scholar

Tao, Youlan. 2016. “Translator Training and Education in China: Past, Present and Prospects.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 10 (2): 204–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2016.1204873.Search in Google Scholar

Torres-Simón, Esther, and Anthony Pym. 2019. “European Masters in Translation: A Comparative Study.” In The Evolving Curriculum in Interpreter and Translator Education: Stakeholder Perspectives and Voices. American Translators Association Scholarly Monograph Series, Vol. 19, edited by David Sawyer, Frank Austermühl, and Vanessa Enríquez Raído, 75–97. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/ata.xix.04torSearch in Google Scholar

Toury, Gideon. 1980. In Search of a Theory of Translation. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics.Search in Google Scholar

Toury, Gideon. 1995. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/btl.4Search in Google Scholar

Venuti, Lawrence. 2012. Translation changes everything: Theory and practice. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203074428Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Qin, and Defeng Li. 2020. “Looking for Translators’ Fingerprints: A Corpus-Based Study on Chinese Translations of Ulysses.” In Corpus-based Translation and Interpreting Studies in Chinese Contexts, edited by K. Hu, and K. Kim, Palgrave Studies in Translating and Interpreting. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-21440-1_6Search in Google Scholar

Wen, Yun, and Walter J. B. van Heuven. 2017. “Chinese Translation Norms for 1,429 English Words.” Behavior Research Methods 49 (3): 1006–19. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0761-x.Search in Google Scholar

Winters, Marion. 2004. German translations of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned: A corpus-based study of modal particles as features of translators’ style. Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth.10.1080/10228190408566215Search in Google Scholar

Winters, Marion. 2013. “German Modal Particles—From Lice in the Fur of Our Language to Manifestations of Translators’ Styles.” Perspectives 21 (3): 427–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2012.711842.Search in Google Scholar

Wurm, Andrea. 2020. “Translation Quality in an Error-Annotated Translation Learner Corpus.” Translating and Comparing Languages: Corpus-based Insights, Corpora and Language in Use Proceedings 6: 141–62.Search in Google Scholar

Xia, Yun. 2014. Normalization in Translation: Corpus-Assisted Diachronic Research into Twentieth-Century English-Chinese Fictional Translation. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Xiao, Richard. 2010. “How Different Is Translated Chinese from Native Chinese? A Corpus-Based Study of Translation Universals.” International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 15 (1): 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.1.01xia.Search in Google Scholar

Yan, Yidan. 2015. “Corpus-based Translator Style Research: A Case Study of Two English Versions of Lu Xun’s Novels.” Foreign Language Teaching 36 (2): 109–13.Search in Google Scholar

Zanettin, Federico. 1998. “Bilingual Comparable Corpora and the Training of Translators.” Meta: Journal des Traducteurs/Meta: Translators’ Journal 43 (4): 616–30. https://doi.org/10.7202/004638ar.Search in Google Scholar

Zasiekin, Serhii. 2014. “Literary Translation Universals: A Psycholinguistic Study of Novice Translators’ Choices.” East European Journal of Psycholinguistics 1 (1): 223–33.Search in Google Scholar

Zasiekin, Serhii. 2016. “Understanding Translation Universals.” Babel-International Journal of Translation 62 (1): 122–134.10.1075/babel.62.1.07zasSearch in Google Scholar

Zasiekin, Serhii. 2019. “Investigating Cognitive and Psycholinguistic Features of Translation Universals.” Psycholinguistics 26 (2): 114–34. https://doi.org/10.31470/2309-1797-2019-26-2-114-134.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shanghai International Studies University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Medicines as Subjects: A Corpus-Based Study of Subjectification in Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Policy

- Adjusting Mood in Mandarin Chinese: A Game Theory Approach to Double and Redundant Negation with Entropy

- Charting the Trajectory of Corpus Translation Studies: Exploring Future Avenues for Advancement

- Exploring Harmful Illocutionary Forces Expressed by Older Adults with and Without Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multimodal Perspective

- Categorizing and Quantifying Doctors’ Extended Answers and their Strategies in Teleconsultations: A Corpus-based Study

- Gunmen, Bandits and Ransom Demanders: A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Study of the Construction of Abduction in the Nigerian Press

- Three Faces of Heroism: An Empirical Study of Indirect Literary Translation Between Chinese-English-Portuguese of Wuxia Fiction

- From Traditional Narratives to Literary Innovation: A Quantitative Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s Stylistic Evolution

- Book Reviews

- A Corpus-Based Analysis of Discourses on the Belt and Road Initiative: Corpora and the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Medicines as Subjects: A Corpus-Based Study of Subjectification in Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Policy

- Adjusting Mood in Mandarin Chinese: A Game Theory Approach to Double and Redundant Negation with Entropy

- Charting the Trajectory of Corpus Translation Studies: Exploring Future Avenues for Advancement

- Exploring Harmful Illocutionary Forces Expressed by Older Adults with and Without Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multimodal Perspective

- Categorizing and Quantifying Doctors’ Extended Answers and their Strategies in Teleconsultations: A Corpus-based Study

- Gunmen, Bandits and Ransom Demanders: A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Study of the Construction of Abduction in the Nigerian Press

- Three Faces of Heroism: An Empirical Study of Indirect Literary Translation Between Chinese-English-Portuguese of Wuxia Fiction

- From Traditional Narratives to Literary Innovation: A Quantitative Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s Stylistic Evolution

- Book Reviews

- A Corpus-Based Analysis of Discourses on the Belt and Road Initiative: Corpora and the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy