Abstract

Corpus-based genre pedagogy (CBGP), the instructional integration of discourse-based rhetorical analysis and corpus-based linguistic analysis of diverse genres, has gained attention from English for Academic Purposes (EAP) researchers and practitioners aiming to cultivate the academic writing skills of second language (L2) learners. This has led to a need for the continuous conceptualization of CBGP (Lu, Xiaofei, J. Casal Elliott, and Yingying Liu. 2021. “Towards the Synergy of Genre- and Corpus-Based Approaches to Academic Writing Research and Pedagogy.” International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 11 (1): 59–71). Additionally, usage-based approaches to L2 acquisition (U-SLA), a collection of cognitive and potentially sociocognitive theoretical approaches to language and language acquisition (Ellis, Nick C., Ute Römer, and Matthew Brook O’Donnell. 2016. Usage-Based Approaches to Language Acquisition and Processing: Cognitive and Corpus Investigations. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell; Wulff, Stepanie, and Nick C. Ellis. 2018. “Usage-Based Approaches to Second Language Acquisition.” In Bilingual Cognition and Language: The State of the Science across its Subfields, edited by D. Miller, F. Bayram, J. Rothman, and L. Serratrice, 37–56. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), have called for more pedagogically oriented research informed by usage-based principles (e.g., Tyler, Andrea E., Hae In Park, Mariko Uno, and Lourdes Ortega, eds. 2018. Usage-inspired L2 Instruction: Researched Pedagogy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company). Responding to such calls, we argue for conceptualizing CBGP as usage-inspired instruction given its intersections with key U-SLA instructional tenets. We first systematically review empirical studies on CBGP. Then, we introduce relevant U-SLA instructional tenets and interpret the CBGP studies to illuminate the extent to which CBGP resonates with different aspects of the U-SLA tenets. Eventually, we argue that CBGP can potentially unify the “social” and the “cognitive” in U-SLA’s accounts of L2 teaching and learning, making it a feasible way to materialize usage-inspired L2 instruction in actual classroom practice. Finally, we discuss future research and practical directions.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, corpora and corpus tools have been increasingly used to establish the foundation and expansion of a fruitful line of pedagogically oriented research on foreign or second language (L2) teaching and learning. Such research has highlighted the effects and values of pedagogical corpus applications (Flowerdew 2012; Römer 2008, 2011), including indirect applications such as corpus-informed curricular or material development, direct applications such as teacher- and/or learner-directed exploration of and learner engagement with corpora, or a combination of both (e.g., Casal and Yoon 2023; Chang 2014; Charles 2007, 2011, 2012, 2014; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cortes 2006; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2015, 2016; Friginal 2013; Lee and Swales 2006; Poole 2016).

Among the applications mentioned above, corpus-based genre pedagogy (CBGP) has attracted attention from English for Academic Purposes (EAP) genre researchers, teacher educators, and practitioners interested in cultivating academic writing skills or, more broadly, genre competence (Tardy 2009), of university-level L2 learners. Collectively informed by corpus linguistics (Sinclair 1987), data-driven learning (Johns 1986, 1994), and the seminal works of Swales (1990, 2004 on genre research and analysis, CBGP involves EAP writing teachers in crafting and implementing lessons, activities, and assignments that systematically enable L2 learners to (1) conduct discourse-based, manual analysis of chunks of texts performing coherent communicative functions – i.e., rhetorical moves and steps (Moreno and Swales 2018; Swales 1990, 2004), (2) identify recurring linguistic patterns (e.g., lexical, phraseological, syntactic) using automated or semi-automated corpus tools, and (3) map the patterns to the moves/steps in terms of their intended rhetorical aims. Such pedagogy is rooted in the “Social/Genre” approach to academic writing instruction (Tribble 1997, 84–85; see also Tribble 2009), which emphasizes “the complexity of discursive practices” (Bhatia 2015, 9) that manifests intentions, conventions, and shared expectations of members of the academic discourse community. Overall, CBGP aims to raise L2 learners’ awareness of such complexity explicitly and subsequently facilitates the development of these writers’ genre competence comprising of rhetorical and formal/linguistic knowledge, among others (Polio 2017; Tardy 2009) so that they can succeed at and beyond the university level. Thus, recent calls have been made for the continuous conceptualization, application, and expansion of such pedagogy to effectively adapt to and address the diverse needs of L2 learners across different instructional contexts (e.g., Flowerdew 2015; Lu, Casal, and Liu 2021).

Potentially related to L2 teaching and learning are usage-based approaches to second language acquisition, i.e., U-SLA, which entails a collection of theoretical approaches to language and language acquisition (Wullf and Ellis 2018). Aiming to uncover how cognition, sociality, and language interact (Ellis, Römer, and O’Donnell 2016), U-SLA draws on concepts and insights from theory and research in psychology, psycholinguistics, first language (L1) acquisition, cognitive science, and linguistic theory (e.g., systemic functional linguistics), among others. Although U-SLA has been traditionally characterized as encapsulating various cognitive approaches to second or additional language acquisition (e.g., Behrens 2009; Ellis 2015; Tomasello 2003) with limited investigations into issues related to classroom instruction, recent trends have moved towards a reconciliation between the social and cognitive dimensions of language, language teaching, and language learning in terms of translating U-SLA insights into pedagogical practice (e.g., Douglas Fir Group 2016; Hulstijn et al. 2014). These trends have inspired an emerging line of pedagogically oriented research informed by usage-based principles (e.g., Cadierno and Eskildsen 2015; Tyler et al. 2018) and subsequently invoked ongoing calls for developing usage-based teaching strategies (e.g., Han 2021).

Responding to the trends and calls above, we argue for conceptualizing CBGP as usage-inspired instruction in L2 EAP writing classes given its multifaceted intersections with a series of key U-SLA instructional tenets. While recognizing that CBGP may not represent all aspects of U-SLA principles, we explore its potential for unifying the “social” and the “cognitive” in U-SLA’s accounts of L2 teaching and learning and illustrate how it may serve as a feasible way to materialize usage-inspired L2 instruction in actual classroom practice.

The remainder of this article is organized into four sections. In Section 2, we systematically review the body of research on the use and potential effects of CBGP in different types of EAP instructional contexts. Then, Section 3 introduces established usage-inspired L2 instructional tenets relevant to the purpose of this article. In Section 4, we reinterpret the studies reviewed in Section 2 to illuminate the extent to which CBGP resonates with different aspects of the tenets in Section 3. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss the implications of our argument and propose future research and pedagogical directions.

2 Pedagogically Oriented EAP Research on Corpus-Based Genre Pedagogy

CBGP derives from corpus-based genre analysis, which aims to reconcile the “form-function gap” (Moreno and Swales 2018, 41) in EAP writing scholarships by integrating discourse-based Swalesian rhetorical move-step analyses and corpus linguistic investigations. Genres are social or communicative events consisting of members with shared communicative purposes, the actions of those members, and socially recognized conventions (Bhatia 1993; Swales 1990, 2004). Within a text, such events are structured by rhetorical moves and steps realized by linguistic devices ranging from as elaborated as a clause to as minor as a lexical item. Corpus-based genre analysis contributes to EAP genre research by unifying the rhetorical/functional and linguistic/formal dimensions of academic genres. As Lu, Casal, and Liu (2021) argued, such analysis enriches pure corpus analysis by highlighting the textual context in which recurrent linguistic patterns appear and the communicative functions such patterns may accomplish. It also complements the often small-scale rhetorical move-step analysis by uncovering the vast linguistic resources used to build different moves/steps.

As a direct pedagogical application of corpus-based genre analysis, CBGP entails a combination of manual analysis of rhetorical moves/steps and corpus analysis of target linguistic features relevant to the moves/steps in L2 writing classes. It differs from characterizing pedagogical uses of corpora or corpus tools as “corpus-enhanced” (e.g., Cortes 2006, 401), “corpus-informed” (e.g., Friginal 2013, 210; Lee and Swales 2006, 58), “corpus-aided” (e.g., Poole 2016, 99), or “corpus-driven” (Chang 2014, 255), all of which primarily involve L2 learners in compiling corpora, learning about corpus tools, and/or conducting corpus searches on different linguistic features without explicitly having such learners perform rhetorical analysis and form-function mapping. While such research has illuminated the vital role and power of corpora in facilitating multiple aspects of L2 EAP writing instruction, it falls outside the scope of the current review, which focuses on the pedagogical integration of rhetorical and corpus linguistic analyses.

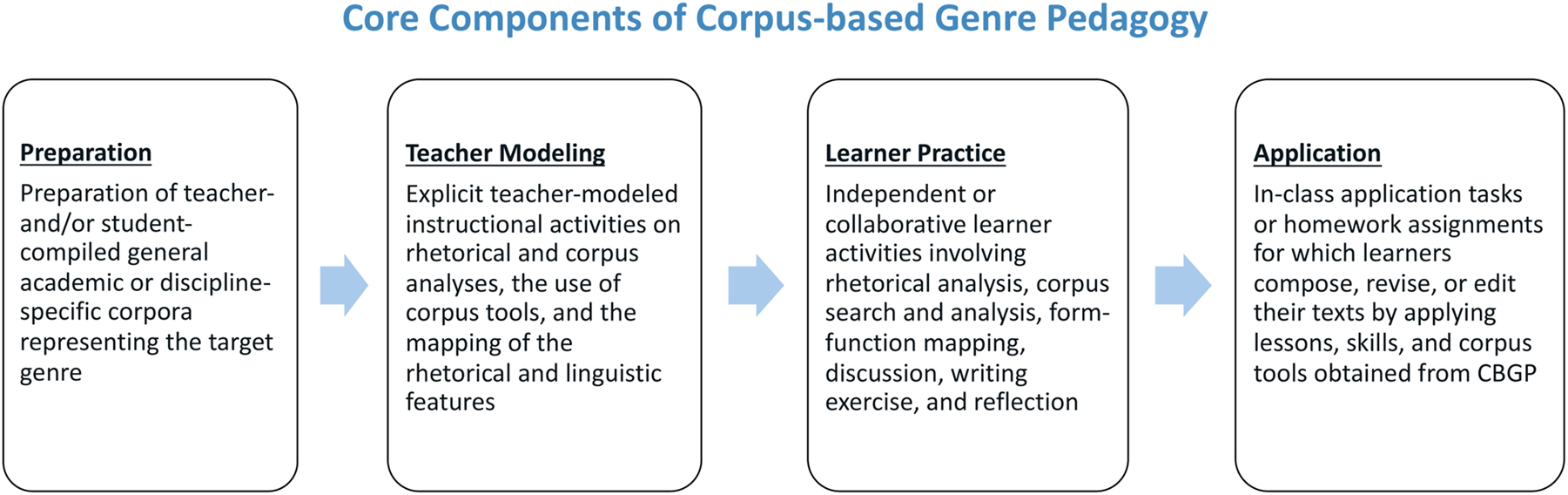

As Figure 1 illustrates, the enactment of CBGP typically includes four core components: (1) preparation of teacher-compiled and/or student-compiled corpora of general academic texts or discipline-specific texts representing the target genres or part-genres, (2) teacher-modeled instructional activities on rhetorical move or move-step analysis, use of corpus tools, and systematic mapping of target linguistic features into the rhetorical features, (3) in-class student activities in which L2 learners conduct rhetorical and corpus analyses on texts from the corpora and participate in different types of group tasks (e.g., collaborative searches of target linguistic features, collaborative form-function mapping, reflections, negotiations on meaning, etc.), and (4) application activities or homework assignments for which students apply their skills to their own writing projects (e.g., regular assignments, theses, dissertations, or manuscripts) with ongoing reinforcement tasks, such as practice of rhetorical and corpus-based linguistic analyses, exposure to different corpus tools, discussions, peer-reviews, revisions, and reflections, to exemplify but a few.

Core components of corpus-based genre pedagogy.

In contrast to the extensive body of corpus-based EAP genre research targeting diverse academic genres or part-genres in different academic disciplines or various genres in professional communities (e.g., Cortes 2013; Durrant and Mathews-Aydınlı 2011; Le and Harrington 2015; Lim 2010; Lu, Casal, and Liu 2020; Omidian, Shahriari, and Siyanova-Chanturia 2018; Yoon and Casal 2020), research on CBGP is still emerging (e.g., Casal and Yoon 2023; Charles 2007; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2015, 2016). Nonetheless, it has documented and examined the procedures, sequences, and potential outcomes of the four components above that structure CBGP in light of varied instructional foci in different L2 instructional contexts.

In Charles’ (2007) pioneering study, 40 international graduate students or student researchers from 27 disciplinary fields and various linguistic/cultural backgrounds participated in an eight-week L2 writing class at the University of Oxford with the potential learning goal of improving their thesis writing skills. The instructor implemented corpus-based pedagogy primarily from weeks three to five. The students were first instructed to analyze various rhetorical moves (e.g., Defending your research against criticism, Charles 2007, 293) by identifying stretches of texts showcasing how academic writers acknowledge and mediate weaknesses in their arguments in sample theses from two pre-built discipline-specific corpora: MPhil theses in politics/international relations and doctoral theses in material science. The students were then instructed to conduct concordance searches on lexico-grammatical items (e.g., while) that helped perform the function of doing concession, followed by optional self-directed searches for other lexico-grammatical items performing similar functions. Although Charles (2007) did not report relevant learning outcomes, the study represents a promising start for incorporating CBGP into L2 writing classes. In a series of subsequent studies that primarily aimed to explore L2 students’ experience in and engagement with self-compiled or general corpora in and beyond their EAP writing classes, Charles (2011, 2012, 2014 continued to argue for the needs and benefits of implementing and expanding CBGP, one that provides enriched linguistic input and support necessary for L2 students to make informed rhetorical choices in their writing.

Extending Charles’ (2007) focus on the use of CBGP in English as a Second Language (ESL) instructional contexts to English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts, Dong and Lu (2020) explored how CBGP could support the development of writing skills of 30 master’s students in engineering aiming to revise potentially publishable manuscripts in prestigious international peer-reviewed journals as part of their degree requirements. The students enrolled in a semester-long, discipline-specific EAP writing course at a Chinese university. The instructor and the students first collaboratively built a specialized corpus consisting of the introduction sections of engineering research articles (RAs), which was subsequently annotated for rhetorical moves using Swales’ (2004) CARS (Create a Research Space) Model. Then, through guided corpus-based genre analysis activities, the students iteratively identified annotated moves, analyzed concordance lines to locate recurrent linguistic features, and then searched for particular features and scrutinized their functions concerning relevant moves (Dong and Lu 2020, 140–144). By also triangulating evidence from pre- and post-instruction questionnaires, interviews, students’ reflective journals, and their writing samples, Dong and Lu (2020, 149) concluded that the CBGP effectively promoted the students’ genre awareness and competence.

While the above studies reported the application of CBGP in semester-long L2 writing courses, others explored it in intensive writing workshops embedded within broader instructional sequences (Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Flowerdew 2015). Flowerdew (2015), for example, examined the implementation of CBGP in a two-part workshop as part of a series of voluntary EAP writing workshops hosted at a Hong Kong university involving postgraduate students in science and engineering aiming to improve the writing of their theses. In the first part, the students were instructed to (1) perform manual rhetorical move analysis on sample texts representing discussion sections of RAs retrieved from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University Corpus of Research Articles (CRA), which contains RAs in Engineering and Applied Sciences and Humanities and Social Sciences, (2) identify prototypical move structure patterning, and (3) use corpus tools to search for frequently appearing lexical grammatical or phraseological features that potentially aligned with the move patterning. In the second part, the students were guided to (1) explore the variation of move structure patterning in discussion sections of RAs, (2) identify phrases retrieved from their thesis drafts, and (3) collaboratively discuss and negotiate on the meanings and functions of the phrases regarding the rhetorical moves (Flowerdew 2015, 59–65).

Based on positive comments from the workshop participants in Flowerdew (2015), Chen and Flowerdew (2018) recruited 473 postgraduate EFL students in Hong Kong to participate in a large-scale, three-phase CBGP intervention. The intervention was comprised of (1) an introduction to corpora and corpus techniques; (2) a series of activities on integrated rhetorical and corpus analyses on two corpora: (a) the written academic component of the BNCweb corpus and (b) a teacher-built discipline-specific corpus of RAs; and (3) a self-directed corpus-building and analysis activity that asked the student participants to compare their work to the expert corpus they compiled. While Chen and Flowerdew (2018, 107–109) did not explicitly assess student learning outcomes, the students self-reported positive perceptions of the CBGP intervention, especially in identifying and applying useful linguistic expressions to realize particular rhetorical goals.

While the studies reviewed above have documented the enactment and potential effects of CBGP in teaching established academic genres (e.g., RA part-genres & theses), others have focused on CBGP for teaching academic promotional genres (Bhatia 1993), such as grant proposals (Flowerdew 2016) and conference abstracts (CAs) (Casal and Yoon 2023). Flowerdew (2016) reported the application of CBGP in a course module about writing grant proposal abstracts for postgraduate students primarily in science and engineering at a Hong Kong university. Following instructional procedures comparable to that in Flowerdew (2015), Flowerdew (2016) guided the students to iteratively combine bottom–up and top–down rhetorical move analyses, conduct corpus searches on various lexico-grammatical and phraseological features, and match the linguistic features to the rhetorical moves in grant proposals from different disciplines. More recently, Casal and Yoon (2023) explored the use of CBGP in a six-week, multidisciplinary academic writing course for L2 graduate writers at a U.S. university. While a genre-based curriculum structured the entire course, it incorporated rhetorical analysis, corpus activities, teacher-compiled discipline-specific and cross-disciplinary corpora, and learner-compiled, discipline-specific corpora. In particular, throughout three class sessions that focused on writing CAs involving 10 student participants from eight disciplines, one researcher (who was also the course instructor) implemented teacher-led lectures of phraseological and rhetorical concepts in CAs, guided the students to search for phrase-frames (discontinuous multiword sequences) that were used to realize different moves and steps in CAs, and engaged the students into a variety of discussion and reflection activities. By synthesizing results from analyzing the students’ CA drafts and relevant revisions, post-intervention surveys, and semi-structured interviews with the students, Casal and Yoon (2023, 110–111) concluded that the students overall demonstrated a growing awareness of varying levels regarding making intentional rhetorical and linguistic choices in their academic writing.

Finally, given the growing trend of incorporating data-driven learning (Johns 1986, 1994) into EAP genre pedagogy, some researchers have explored how L2 learners interact with automated or semi-automated corpus platforms regarding their genre competence development. For example, Cotos, Huffman, and Link (2017) examined the impact of Reading Writing Tutor (RWT), a web-based platform containing a multidisciplinary corpus of 900 published RAs annotated for rhetorical moves and steps at different levels, on the learning of 23 native-speaking student writers of English and L2 student writers in a semester-long, graduate-level EAP writing class. Aiming to learn or improve their academic writing skills, the students iteratively interacted with RWT through “rhetorical composition analysis” and “language analysis” tasks (Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017, 115), in which they identified annotated texts, contemplated their rhetorical functions, engaged with the automated feedback generated by RWT, and searched for distribution and sequence in move-step patterning. Based on their learning with and through RWT, the students revised and annotated their drafts for moves and steps. Consistent with the findings from Casal and Yoon (2023), Cotos, Huffman, and Link (2017, 115–123) reported that the interaction with RWT promoted the students’ genre competence development and strengthened the quality of their genre writing, especially regarding the students’ growing awareness of rhetorical and linguistic patterns and their relationship in academic writing as the researchers compared improvement across the students’ first and final drafts.

The studies reviewed above show that CBGP can be flexibly adapted to diverse instructional contexts (e.g., EFL and ESL) and used in different instructional formats (e.g., semester-long courses and intensive workshops) to meet the various needs of L2 learners, ranging from improving general academic writing skills to discipline-specific or genre- and even part-genre specific writing skills (e.g., thesis, RA introductions, CAs, and grant proposals) for a variety of learning goals, including fulfilling course or degree requirements (Charles 2007; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2015), writing for publications/conference presentations (Casal and Yoon 2023; Dong and Lu 2020), and potentially applying for grants (Flowerdew 2016). Despite such flexible application, however, explicit teacher modeling on rhetorical and corpus analyses, collaborative learner engagement with corpora or corpus tools in terms of the linguistic realizations of different rhetorical components in different target genres, in-class discussions, and individual or collaborative application tasks with post-instruction reflections consistently appear at different phases of CBGP. On the one hand, CBGP has been employed to target different linguistic dimensions of L2 teaching and learning, ranging from lexico-grammatical features (Charles 2007; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Flowerdew 2015, 2016) to phraseological features (Casal and Yoon 2023) or a combination of both (Dong and Lu 2020) as exhibited and afforded by the pedagogical use of general or discipline-specific corpora. On the other hand, it continues to involve L2 learners in a series of carefully designed and hands-on instructional activities in which they closely interact with and actively apply a diverse repertoire of rhetorical and linguistic resources that collectively make scholarly written communication possible and meaningful. As will be interpreted below, CBGP can be conceptualized as a pedagogical manifestation of a range of usage-inspired tenets relevant to L2 classroom instruction.

3 A Synopsis of Usage-Inspired L2 Instructional Tenets

As briefly introduced in Section 1, U-SLA encompasses a range of theoretical approaches to studying L2 and L2 acquisition with strong implications for L2 teaching/learning. Informed by various U-SLA constructs and insights, the following tenets have been argued for and elucidated in recent conceptual and empirical research on translating U-SLA insights into classroom practice (e.g., Cadierno and Eskildsen 2015; Tyler et al. 2018) and therefore provide an insightful lens for conceptualizing CBGP. Moreover, while they do not fully cover all usage-inspired principles applicable to instruction, they collectively revolve around U-SLA’s ongoing aim of conceptualizing language as encapsulating both the “social” and the “cognitive” especially from a pedagogical perspective, a potential which CBGP possesses.

First and foremost, language comprises constructions, i.e., conventionalized form-meaning/function pairings, ranging from morphemes to words, phraseological units, and larger syntactic frames (Goldberg 1995, 2006). As building blocks of language, constructions relate different dimensions or properties of the target language (TL) with particular semantic, pragmatic, and discourse functions (Ellis and Cadierno 2009). Therefore, L2 learning, and by extension, L2 teaching should target constructions as instructional focus by intentionally and actively involving learners in recognizing, processing, practicing, and engaging with constructions.

Second, the learning of constructions is input- and frequency-driven and dependent on learners’ experience with form-meaning/function mappings in different contexts and through goal-directed, participatory experiences (Cadierno and Eskildsen 2015; Ellis and Cadierno 2009; Tyler and Ortega 2018). A related tenet is that learner engagement with the linguistic input they receive should be largely meaning-centered and function-oriented (Douglas Fir Group 2016; Tyler 2010; Tyler and Ortega 2018) while attending to linguistic form (Ellis and Cadierno 2009). This means that (1) the kinds of linguistic input, (2) the frequency of exposure to constructions of the TL in the contexts in which they are most likely to occur, and (3) the level of learner engagement with different dimensions of the constructions directed by specific learning goals and particular attention to meaning and function are driving forces for L2 learning and should thus inform L2 teaching in terms of development and implementation of curriculum, materials, or tasks and activities.

Related to input is the concept of output or production, which, from a usage-inspired instructional perspective, is the process of identifying the communicative intentions of interlocutors, tasks, or materials and subsequently adjusting or manipulating relevant semiotic resources to accomplish the observed functions (Tomasello 2003). Therefore, usage-inspired L2 pedagogy should equip L2 learners with a repertoire of resources to construct meaning, express ideas, and perform tasks while nudging them to marshal such resources to serve the communicative functions of a certain discourse.

Finally, U-SLA traditionally views L2 acquisition as primarily implicit (Ellis 2008), i.e., an unconscious, automatic process of induction leading to intuitive knowledge, such as how a mature L1 speaker uses L1 with both comprehension and production seemingly automatic and executed with ease. This is different from explicit knowledge, of which a learner is consciously and intentionally aware, can articulate verbally, and can be summoned on demand (e.g., Dörnyei 2009; Ellis 2004; Hulstijn 2005), such as performing form-meaning/function pairings or explaining constructions in metalinguistic terms. However, from a usage-inspired instructional perspective, implicit and explicit knowledge mutually complement one another, so both need to be acknowledged and cultivated in L2 classrooms (Tyler and Ortega 2018; see also Douglas Fir Group 2016).

4 CBGP as Usage-Inspired L2 Instruction

4.1 CBGP and Usage-Inspired Instructional Tenets

CBGP resonates with the usage-inspired L2 instructional tenets as explained above, making them “visible” and “doable” on various levels. To begin, it captures the idea of conceptualizing language as constructions and language learning as the learning of constructions by instructing learners to conduct form-meaning/function mapping between a wide variety of linguistic items (form) and rhetorical moves or steps (function) identified in different general or specialized academic corpora. Although the notion of “function” in constructions, which includes a combination of semantic, pragmatic, and discourse functions (Ellis and Cadierno 2009), may be different from that in Swalesian rhetorical move/step analysis, which primarily refers to communicative functions (Swales 1990, 2004), attending to the communicative functions manifested in as large as a chunk of text (e.g., a paragraph) or as small as a lexico-grammatical item (e.g., the word However) demands a robust analysis and interpretation of its meaning, use, and position in discourse. In Charles (2007), for example, the 40 students were guided to iteratively search for lexical-grammatical items that helped to realize the communicative functions of performing and defending criticism in RAs in the two discipline-specific corpora. As Charles (2007, 300) argued, orientating the students’ attention to and use of words and phrases that embodied the meaning of contrast, concession, and/or justification could equip the students with “a richer experience of the rhetorical pattern than would be achieved through work of either type [linguistic form or communicative function] alone.” For another example, Flowerdew (2015) observed that the CBGP deepened her students’ understanding of the rhetorical function of conditionals (e.g., if-clause) and could help them use conditionals more accurately and meaningfully in writing discussion sections for their graduate theses. Similar observations have also been reported and interpreted in other studies (Casal and Yoon 2023; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2016), which, from a usage-inspired L2 instructional perspective, collectively showcase the notion of constructions being incorporated into different stages of CBGP.

When L2 learners engage with constructions exhibited in different annotated corpora and facilitated by their L2 writing teachers, they are inherently provided with abundant linguistic resources frequently used by experts in their disciplinary communities or general academic writing contexts. This is another potential overlap between CBGP and one of the tenets above in that CBGP exposes L2 learners to a range of frequency-driven input. Corpora are the place to look for such input, as manifested in patterns of usage (e.g., lexico-grammatical and phraseological items) and determined by the frequency of occurrence of such patterns. Thus, CBGP creates hands-on opportunities in which L2 learners can iteratively interact with frequently appearing patterns as input through corpus searches, discussions, form-function mappings, and various applications. For example, Flowerdew’s (2016) students analyzed patterns of key moves in grant proposal abstracts written by novice and expert researchers and subsequently identified frequent linguistic features that signaled or implemented the move patterns. The researcher noticed that the students gained a reinforced understanding of the availability of a variety of recurrent general academic and discipline-specific linguistic resources for creating pragmatically appropriate and rhetorically powerful effects in the writing of grant proposals (Flowerdew 2016, 6), such as “insinuat[ing] the appropriacy of the technique [outlined in the proposal] by strategically linking the approach in an unproblematic way to accomplishing the research objective” (Hyland 2004, 73–74). Likewise, Cotos, Huffman, and Link (2017) documented evidence of increased transfers of their students’ corpus-based learning to their academic writing when the students continued to notice and frequently interact with the rhetorical and linguistic input as generated and facilitated by RWT.

In a usage-inspired L2 instructional account, integral to L2 learning in terms of L2 learners’ frequent exposure to and interaction with input are the particular goals in participatory learning experiences. CBGP resonates with this tenet by emphasizing a sense of intentionality in its design and implementation and addressing different L2 learners’ needs and expectations. On the one hand, it provides a series of goal-directed learning experiences in annotations and analyses of rhetorical moves and steps, the fundamental constructs in genre research and analysis (Swales 1990, 2004) that exhibit how writers intentionally deploy and manipulate different chunks of texts to achieve their rhetorical aims (Casal and Yoon 2023; Charles 2007; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2015, 2016). On the other hand, it targets a variety of L2 learners with a combination of high-stakes and low-stakes learning objectives. For example, for students in Charles (2007) and Dong and Lu (2020), CBGP addressed their objectives of learning to improve their thesis-writing for graduation or preparing a publishable manuscript to satisfy degree requirements, respectively, while students in other studies aimed to strengthen their academic writing skills for navigating different general or specialized academic genres or part-genres (Casal and Yoon 2023; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Flowerdew 2015, 2016).

Notably, the different needs and characteristics of L2 learners also shape the types and dimensions of input being emphasized in enacting CBGP. Given that the students in Cotos, Huffman, and Link (2017) included a mixture of L1 and advanced L2 learners, their primary learning objective was to identify and familiarize themselves with the rhetorical conventions (moves and steps) in the introduction sections of RAs facilitated by RWT. Therefore, their interaction with the linguistic input may have been less prioritized than the rhetorical input. On the contrary, the students in other studies are L2 learners, so their engagement with both rhetorical and linguistic input was more balanced (Casal and Yoon 2023; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Flowerdew 2015, 2016; Dong and Lu 2020). Overall, insofar as one of the usage-inspired L2 instructional tenets highlights the role of learner/learning goals in relation to the kinds of input being offered in the participatory experiences in L2 classrooms, CBGP captures this tenet by infusing myriad kinds of rhetorical and linguistic input and learner opportunities with such input in terms of their alignment with particular learner/learning goals.

While exposing L2 learners to meaning-focused, function-oriented, and frequency-driven input and creating goal-directed opportunities for them to interact with such input is important for invoking and sustaining L2 learning in the classroom, enabling L2 learners to actively apply what they have gained from the input through output or production is equally paramount from a usage-inspired perspective (Tomasello 2003). The body of research reviewed in Section 2 has gradually shifted from primarily exploring L2 learners’ or teachers’ perceptions of CBGP and relevant use of corpora or corpus tools as well as presenting researchers’ own observations of student learning (Charles 2007, 2011, 2012, 2014; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Flowerdew 2015, 2016) to explicitly and more rigorously delving into actual development in L2 learners’ genre awareness and knowledge as gauged in learner performance in a range of output or production tasks (Casal and Yoon 2023; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020). Specifically, students in the workshops of Charles (2007) and Flowerdew (2015) were provided with optional production tasks, such as writing a paragraph using a “two-part concession [rhetorical] pattern to defend their own work against criticisms” (Charles 2007, 295) as a homework assignment and collaboratively searching for and unpacking the meaning of engagement markers or phrases that were rhetorically appropriate for writing thesis discussion sections (Flowerdew 2015). However, students in other studies were given more sophisticated production tasks that demanded more autonomy and independence, including writing CAs (Casal and Yoon 2023), multiple drafts of RAs (Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017), or particular sections of RAs (Dong and Lu 2020). Moreover, a wide variety of measures, such as comparisons across student drafts and reflective journals, post-instruction questionnaires and interviews, and interpretations of advisor comments on students drafts, have been deployed to examine not only what the L2 learners and their EAP writing teachers thought of CBGP but also how the learners learned and what they actually learned (Casal and Yoon 2023; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020). In short, the continuous inclusion and implementation of production tasks in CBGP and the learning outcomes unveiled through the above measures have yielded convincing evidence on how CBGP potentially corroborates the usage-inspired instructional tenet in terms of the necessity and value of output in L2 learning.

Lastly, CBGP is linked to usage-inspired instructional tenets by addressing the cultivation of explicit knowledge in L2 learning with implications for the subsequent development of implicit knowledge. Notably, all studies reviewed in Section 2 primarily focus on and promote L2 learners’ genre competence and explicit awareness in terms of the relevant constructs, purpose, effects, and reasoning when conducting and applying rhetorical and corpus linguistic analyses (Casal and Yoon 2023; Charles 2007; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2015, 2016). While the L2 learners in Charles (2007), Flowerdew (2015, 2016, and Chen and Flowerdew (2018) began their learning in a more implicit way as their EAP writing teachers nudged them to scrutinize and collaboratively analyze the rhetorical and/or linguistic features of stretches of pre-assigned texts without being exposed to the notions of rhetorical moves and steps, they gradually moved towards the more explicit side by performing a combination of top–down and bottom–up rhetorical and corpus linguistic analyses and subsequently trying to articulate and explain their reasonings.

As compared to the L2 learners in the studies above, those in Cotos, Huffman, and Link (2017), Dong and Lu (2020), and Casal and Yoon (2023) participated in an iterative learning process of implicit exposure to CBGP and its related concepts through brainstorming and discussions and explicit practices such as conscious-raising exercises and application tasks. While Dong and Lu (2020, 149) highlighted that the CBGP activities created “useful inductive learning processes that helped them [the students] generalize linguistic patterns associated with different rhetorical moves and consolidate the genre knowledge they acquired in the writing course,” Casal and Yoon (2023, 110–112) reported “growing intentionality in [their students’] decisions regarding language and rhetoric” and increased awareness “in the way learners talk and think about writing” in terms of their metacognitive writing strategies.

Notably, all the studies above focused on the implementation of CBGP in intensive workshops or semester-long courses, so they did not track the extent to which the L2 learners’ explicit genre knowledge would be transferred or internalized into implicit knowledge, which often takes a longer time with a slower pace (Dörnyei 2009; Ellis 2004; Hulstijn 2005). However, they have yielded emerging yet compelling insights into how L2 learners could develop explicit knowledge from GBPG and could potentially rely on it to intentionally regulate and enrich their genre awareness, writing strategies, and overall meaning-making repertoire when navigating different genres or academic writing tasks in different contexts involving various rhetorical conventions, expectations, and purposes.

4.2 CBGP and the Bridging Between the Social and the Cognitive

As noted in Section 3, a unified understanding regarding the social and cognitive dimensions of language, language teaching, and language learning has been formulated and argued for in terms of applying U-SLA theoretical insights to inform classroom instruction (e.g., Douglas Fir Group 2016; Hulstijn et al. 2014). Such understanding views language as conceptual or cognitive representations situated in and emerging from human interactions with the physical and social world. Humans rely on their conceptualizations of the physical and social world as a foundation for representing and communicating internal phenomena, such as emotions, thoughts, and abstract concepts. They subsequently use language to convey the social or physical underpinning for conceptualization. In other words, humans regularly think and talk about internal phenomena in terms of the external world by using and adjusting their language in social interactions.

Such bridging between the social and cognitive of language from a usage-based point of view may be conceptually parallel to the notion of genre. As a series of communicative events, genre from the Swalesian perspective is both social and cognitive in that it encompasses writers’ intentional and strategic orchestration of a range of rhetorical and linguistic resources to create meanings, impart messages, and invoke reader–writer interactions (Bhatia 1993; Swales 1990, 2004). Pedagogically, this requires L2 writing teachers to conceptualize whatever texts they aim to target as discipline- and genre-specific forms of social interaction (Hyland 2004) and subsequently create opportunities that immerse students into such interaction in which they frequently and systematically adjust and manipulate what they communicate and how they communicate based on their detections of and continuous engagement with the set of shared conventions, expectations, and values upheld by members of their intended discourse communities. The social-cognitive bridging is substantiated in Casal and Yoon (2023, 111), in which the students were able to “identify instances of particular rhetorical features and explain the reasoning behind their decisions,” which demonstrates their utilization of metacognitive strategies to “navigate the cognitively demanding task [writing CAs].” Although more empirical investigations are expected to fully verify the presence and manifestation of this bridging in classrooms, the students’ ability, as evidenced in Casal and Yoon (2023), to articulate their cognitive processes and self-regulate their writing strategies underscores its potential.

From the above perspective, then, we interpret that CBGP possesses the potential of linking the social and the cognitive, particularly in terms of informing and advancing EAP writing pedagogy in L2 instructional contexts, given the multifaceted overlaps and resonations between CBGP and the set of usage-inspired L2 instructional tenets as described above. As usage-inspired instruction, CBGP concretizes language as a series of abstract constructions by directing L2 learners’ attention to the inseparable relationship between form, meaning, and function, as displayed in and mobilized by genre-related concepts such as rhetorical and linguistic resources – concepts that unpack how meanings may be created, how actions may be strategized based on differing rhetorical aims, and how interaction, negotiation, or engagement with conventions in discourse communities may be practiced in academic writing. Essentially, it exposes L2 learners to a diverse range of frequency-driven rhetorical and linguistic input as patterns that emerge from natural discourse (corpora), therefore establishing a foundation for EAP writing teachers to develop goal-directed tasks or activities in which their students can wrestle with the meaning and function of such patterns and apply them in different output tasks targeting a variety of genres or part-genres and based on different learner/learning needs.

5 Discussion and Future Directions

Conceptualizing CBGP as usage-inspired L2 instruction is conceptually and practically meaningful from multiple perspectives. In the field of corpus linguistics, scholars or researchers interested in classroom instruction have long bemoaned the disconnect between theory, research, method, and practice in terms of translating corpus linguistic insights into concrete pedagogical practices (e.g., Chambers 2019; Mukherjee 2006). One way to bridge this gap is to build a principled understanding of and approach to addressing the needs of L2 learners (Römer 2011). Specifically concerning the teaching of L2 writing, this entails teachers tapping into a range of resources to identify and comprehend how students acquire and grasp their L2, especially for academic communication through writing. Furthermore, it involves understanding the internal mechanisms that drive, facilitate, and promote such learning. Put simply, our conceptualization contributes theoretical insights to the body of research on pedagogical corpus applications (Flowerdew 2012; Römer 2008, 2011) in L2 EAP writing instructional contexts (Casal and Yoon 2023; Chang 2014; Charles 2007, 2011, 2012, 2014; Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Cortes 2006; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020; Flowerdew 2015, 2016; Friginal 2013; Lee and Swales 2006; Poole 2016) by validating it through the lens of usage-based concepts, such as input/output, frequency, form-meaning/function mappings, and potentially explicit/implicit knowledge development. These cognitive-related constructs offer rich conceptual resources by orienting L2 writing teachers’ attention to the fundamental principles of language learning: the unit, structure, processes, and procedures of English language learning (e.g., Dolgova and Tyler 2019). Eventually, they can enrich our understanding of CBGP, which has traditionally been characterized as “Social/Genre” approach to EAP writing instruction (Tribble 1997, 2009), potentially connecting the social with the cognitive. This captures the “social and cognitive moment” (Ellis 2015, 65) in usage-based accounts of language teaching and learning.

Moreover, a similar gap also exists in the field of U-SLA, involving challenges in translating usage-based theoretical insights into practical L2 classroom instruction, partly due to the scarcity of informed tools or materials for teachers (Tyler et al. 2018). Therefore, viewing CBGP as usage-inspired L2 instruction can reconcile this gap by making the design and implementation of such instruction feasible in EAP writing contexts with diverse types of L2 learners. This perspective not only expands the limited body of pedagogically oriented U-SLA research (e.g., Cadierno and Eskildsen 2015; Tyler et al. 2018) but also demonstrates the power of corpora or corpus tools in recognizing and presenting appropriate targets of EAP writing instruction, i.e., frequently appearing linguistic expressions and their realizations of rhetorical moves and steps, as recognized, mapped, and practiced by L2 learners in a range of guided exercises and application tasks. From a pedagogical standpoint, it proves that such targets are central to instruction not just because patterns of usage as detected by corpora are authentic, meaningful, and communicatively useful but because they align with learners’ objectives and, therefore, should be treated as actual areas of instructional need and focus. As such, recognizing CBGP as usage-inspired instruction compels EAP writing instructors to contemplate such issues as (1) the frequency of exposure to different input with well-reasoned rationales on the sequence of such input (e.g., prioritizing linguistic input over rhetorical input or vice versa), (2) the quality and level of intensity of such exposure as delivered by various corpus-based instructional activities, and (3) the kinds of output tasks associated with the input as directed by learners’ individual needs, among others, with subsequently more informed instructional decisions. In short, coupling CBGP to the instructional aspects of U-SLA highlights pedagogical corpus applications (Flowerdew 2012; Römer 2008, 2011) and usage-inspired instruction as a collective and “well-researched pedagogy” (Tyler and Ortega 2018, 321).

Based on the above discussion, multiple future research and pedagogical directions exist. First, researchers interested in the interplay between usage-inspired instruction and CBGP could examine how CBGP affects L2 learners’ mental representations, learning, and productions of the target constructions as presented by corpora by exploring such usage-based, cognitive-related constructs as general learning mechanisms (Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2009), salience (Ellis 2006), and learned attention (Ellis 2006). Second, the studies reviewed in Section 2 primarily delve into students’ engagement with and potential growth facilitated by CBGP over short-term periods, including intensive workshops (Chen and Flowerdew 2018; Flowerdew 2015) and lesson sequences within semester-long courses (Casal and Yoon 2023; Charles 2007; Cotos, Huffman, and Link 2017; Dong and Lu 2020). However, learners’ language knowledge development is a notably adaptive, dynamic, and complex process from a usage-based perspective. Consequently, more longitudinal investigations coupled with mixed-method research designs are desired to fully uncover how CBGP contributes to L2 learners’ development of genre competence, encompassing both rhetorical and linguistic knowledge (Polio 2017; Tardy 2009). These investigations can include more explicit measures of learning outcomes beyond teacher or researcher observations and students’ self-reported evidence. For example, syntactic complexity, an important indicator that reflects the writing and language development of L2 learners across grade levels and instructional contexts (e.g., Beers and Nagy 2011; Lu 2011), is an integral linguistic resource for academic writers to adapt to varying disciplinary, genre, and even part-genre conventions (e.g., Casal et al. 2021) and thus merits more research and instructional attention. This endeavor can compensate for the caveats in the studies reviewed in Section 2, further validating CBGP as empirically tested usage-inspired instruction and eventually illuminating how learners’ explicit genre knowledge is internalized into implicit knowledge.

For pedagogical directions, we advocate for the grounding of the design, implementation, and potential assessment of CBGP in two fundamental pedagogical principles, which we coin as Zooming out and Zooming in. In terms of Zooming out, we propose that EAP writing teachers broaden the application of CBGP to provide support not only for advanced graduate-level L2 learners in discipline-specific writing classes – predominantly featured in the student population and instructional context of the studies reviewed in Section 2 – but also extend this support for teaching undergraduate L2 learners in general EAP writing classes. Additionally, these teachers could consider expanding the scope of CBGP to teach academic genres beyond the established ones (e.g., RAs or RA sections), such as those performing promotional functions (e.g., conference proposals, Casal and Yoon 2023; teaching philosophy statements, Wang 2023), which have proven to be intricate for both novice and experienced L2 writers due to their highly flexible writing practices and nuanced audience expectations.

Shifting our focus to Zooming in, we encourage EAP writing teachers to experiment with using CBGP to teach fine-grained linguistic features that tap into the immediate needs of particular learners, such as syntactic complexity as mentioned above. In calling for both Zooming out and Zooming in, we also echo Swales’ (2019) personal call for integrating more contextualized, ethnographical activities into EAP writing instruction. For example, EAP writing teachers could encourage their students to conduct interviews with their advisors or disciplinary experts. The objective would be to assess the degree to which the rhetorical and linguistic patterns learned from CBGP actually capture disciplinary writing practices and conventions. Another feasible teaching strategy involves teachers orchestrating class-wide writer panels, enabling students to engage in conversations with a group of invited seasoned academic writers. The students would first present their learning outcomes and subsequently solicit expert writers’ evaluations and interpretations, such as how a rhetorical move can be flexibly deployed to accomplish different rhetorical aims or how the same linguistic device can invoke different meanings according to its corresponding moves. These activities can cultivate ample opportunities for students to actively reflect on their learning and to critically discern and appreciate how factors beyond the pure textual dimension, including general audience expectations, writers’ individual preferences, and disciplinary norms, inherently influence and complicate writing practices. Finally, given the immense conceptual and methodological stumbling blocks associated with the pedagogical applications of corpora or corpus tools (Flowerdew 2012; Römer 2008, 2011), we invite corpus specialists interested in teacher education to develop systematic training to foster EAP writing teachers’ corpus literacy (Callies 2019) so that they could better empower relevant L2 learners.

References

Beers, Scott F., and William E. Nagy. 2011. “Writing Development in Four Genres from Gades Three to Seven: Syntactic Complexity and Genre Differentiation.” Reading and Writing 24: 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9264-9.Search in Google Scholar

Behrens, Heike. 2009. “Usage-Based and Emergentist Approaches to Language Acquisition.” Linguistics 47: 383–411. https://doi.org/10.1515/LING.2009.014.Search in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Vijay K. 1993. Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Vijay K. 2015. “Critical Genre Analysis: Theoretical Preliminaries.” HERMES-Journal of Language and Communication in Business 54: 9–20. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v27i54.22944.Search in Google Scholar

Cadierno, Teresa, and Søren Wind Eskildsen. 2015. “Advancing Usage-Based Approaches to L2 Studies.” In Usage-Based Perspectives on Second Language Learning, edited by T. Cardierno, and S. W. Eskildsen, 1–16. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110378528-003Search in Google Scholar

Cadierno, Teresa, and Søren Wind Eskildsen, eds. 2015. Usage-Based Perspectives on Second Language Learning. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110378528Search in Google Scholar

Callies, Marcus. 2019. “Integrating Corpus Literacy into Language Teacher Education.” In Learner Corpora and Language Teaching, edited by J. Mukherjee, and S. Götz, 245–63. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/slcs.201.12calSearch in Google Scholar

Casal, J. Elliott, & Yoon, Jungwan. 2023. Frame-Based Formulaic Features in L2 Writing Pedagogy: Variants, Functions, and Student Writer Perceptions in Academic Writing. English for Specific Purposes, 71, 102–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2023.03.004.Search in Google Scholar

Casal, J. Elliott, Xiaofei Lu, Xixin Qiu, Yuanheng Wang, and Genggeng Zhang. 2021. “Syntactic Complexity across Academic Research Article Part-Genres: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 52: 100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2021.100996.Search in Google Scholar

Chambers, Angela. 2019. “Towards the Corpus Revolution? Bridging the Research-Practice Gap.” Language Teaching 52 (4): 460–75.10.1017/S0261444819000089Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Ji-Yeon. 2014. “The Use of General and Specialized Corpora as Reference Sources for Academic English Writing: A Case Study.” ReCALL 26 (2): 243–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344014000056.Search in Google Scholar

Charles, Maggie. 2007. “Reconciling Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches to Graduate Writing: Using A Corpus to Teach Rhetorical Functions.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6: 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2007.09.009.Search in Google Scholar

Charles, Maggie. 2011. “Using Hands-on Concordancing to Teach Rhetorical Functions: Evaluation and Implications for EAP Writing Classes.” In New Trends in Corpora and Language Learning, edited by A. Frankenberg-Garcia, L. Flowerdew, and G. Aston, 26–43. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

Charles, Maggie. 2012. “‘Proper Vocabulary and Juicy Collocations’: EAP Students Evaluate Do-It-Yourself Corpus-Building.” English for Specific Purposes 31 (2): 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2011.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Charles, Maggie. 2014. “Getting the Corpus Habit: EAP Students’ Long-Term Use of Personal Corpora.” English for Specific Purposes 35: 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2013.11.004.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Meilin, and Lynne Flowerdew. 2018. “Introducing Data-Driven Learning to Phd Students for Research Writing Purposes: A Territory-Wide Project in Hong Kong.” English for Specific Purposes 50: 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2017.11.004.Search in Google Scholar

Cortes, Viviana. 2006. “Teaching Lexical Bundles in the Disciplines: An Example from A Writing Intensive History Class.” Linguistics and Education 17 (4): 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2007.02.001.Search in Google Scholar

Cortes, Viviana. 2013. “The Purpose of This Study is to: Connecting Lexical Bundles and Moves in Research Article Introductions.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 12: 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2012.11.002.Search in Google Scholar

Cotos, Elena, Stephanie Link, and Sarah Huffman. 2017. “Effects of DDL Technology on Genre Learning.” Language Learning and Technology 21 (3): 104–30.Search in Google Scholar

Dolgova, Natalia, and Andrea Tyler. 2019. “Applications of Usage-Based Approaches to Language Teaching.” In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching, edited by X. Gao, 939–61. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_49Search in Google Scholar

Dong, Jihua, and Xiaofei Lu. 2020. “Promoting Discipline-Specific Genre Competence with Corpus-Based Genre Analysis Activities.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 58: 138–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.01.005.Search in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltan. 2009. The Psychology of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Douglas Fir Group. 2016. “A Transdisciplinary Framework for SLA in a Multilingual World.” The Modern Language Journal 100 (S1): 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12301.Search in Google Scholar

Durrant, Philip, and Julie Mathews-Aydınlı. 2011. “A Function-First Approach to Identifying Formulaic Language in Academic Writing.” English for Specific Purposes 30: 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2010.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Rod. 2004. “The Definition and Measurement of L2 Explicit Knowledge.” Language Learning 54: 227–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00255.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2006. “Selective Attention and Transfer Phenomena in L2 Acquisition: Contingency, Cue Competition, Salience, Interference, Overshadowing, Blocking, and Perceptual Learning.” Applied Linguistics 27 (2): 164–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/aml015.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2008. “Usage-Based and Form-Focused SLA: The Implicit and Explicit Learning of Constructions.” In Language in the Context of Use: Cognitive and Discourse Approaches to Language, edited by N. C. Ellis, 93–20. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110199123.1.93Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2015. “Cognitive and Social Aspects of Learning from Usage.” In Usage-Based Perspectives on Second Language Learning, edited by T. Cadierno, and S. W. Eskildsen, 49–73. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110378528-005Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C., and Teresa Cadierno. 2009. “Constructing a Second Language.” Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 7 (Special Section): 111–290. https://doi.org/10.1075/arcl.7.05ell.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C., and Diane Larsen-Freeman. 2009. “Constructing a Second Language: Analyses and Computational Simulations of the Emergence of Linguistic Constructions from Usage.” Language Learning 59 (s1): 90–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00537.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C., Ute Römer, and Matthew Brook O’Donnell. 2016. Usage-based Approaches to Language Acquisition and Processing: Cognitive and Corpus Investigations. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Flowerdew, Lynne. 2012. Corpora and Language Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230355569Search in Google Scholar

Flowerdew, Lynne. 2015. “Using Corpus-Based Research and Online Academic Corpora to Inform Writing of the Discussion Section of a Thesis.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 20: 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

Flowerdew, Lynne. 2016. “A Genre-Inspired and Lexico-Grammatical Approach for Helping Postgraduate Students Craft Research Grant Proposals.” English for Specific Purposes 42: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2015.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

Friginal, Eric. 2013. “Developing Research Report Writing Skills Using Corpora.” English for Specific Purposes 32 (4): 208–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2013.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago: Chicago University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Han, ZhaoHong. 2021. “Usage-Based Instruction, Systems Thinking, and the Role of Language Mining in Second Language Development.” Language Teaching 54 (4): 502–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444820000282.Search in Google Scholar

Hulstijn, Jan H. 2005. “Theoretical and Empirical Issues in the Study of Implicit and Explicit Second-Language Learning: Introduction.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 27: 129–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263105050084.Search in Google Scholar

Hulstijn, Jan H., Richard F. Young, Lourdes Ortega, Martha Bigelow, Robert DeKeyser, Nick C. Ellis, James P. Lantolf, Alison Mackey, and Steven Talmy. 2014. “Bridging the Gap: Cognitive and Social Approaches to Research in Second Language Learning and Teaching.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 36 (3): 361–421. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263114000035.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, Ken. 2004. Disciplinary Discourses: Social Interactions in Academic Writing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.Search in Google Scholar

Johns, Tim. 1986. “Microconcord: A Language-Learner’s Research Tool.” System 14 (2): 151–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(86)90004-7.Search in Google Scholar

Johns, Tim. 1994. “From Printout to Handout: Grammar and Vocabulary Teaching in the Context of Data-Driven Learning.” In Perspectives on Pedagogical Grammar, edited by T. Odlin, 27–45. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524605.014Search in Google Scholar

Le, Thi Ngoc Phuong, and Michael Harrington. 2015. “Phraseology Used to Comment on Results in the Discussion Section of Applied Linguistics Quantitative Research Articles.” English for Specific Purposes 39: 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2015.03.003.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, David, and John M. Swales. 2006. “A Corpus-Based EAP Course for NNS Doctoral Students: Moving from Available Specialized Corpora to Self-Compiled Corpora.” English for Specific Purposes 25 (1): 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2005.02.010.Search in Google Scholar

Lim, Jason Min-Hwa. 2010. “Commenting on Research Results in Applied Linguistics and Education: A Comparative Genre-Based Investigation.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 9: 280–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2010.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Xiaofei. 2011. “A Corpus‐Based Evaluation of Syntactic Complexity Measures as Indices of College‐Level ESL Writers’ Language Development.” TESOL Quarterly 45 (1): 36–62. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.240859.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Xiaofei, J. Elliott Casal, and Yingying Liu. 2020. “The Rhetorical Functions of Syntactically Complex Sentences in Social Science Research Article Introductions.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 44: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100832.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Xiaofei, J. Elliott Casal, and Yingying Liu. 2021. “Towards the Synergy of Genre- and Corpus-Based Approaches to Academic Writing Research and Pedagogy.” International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 11 (1): 59–71.10.4018/IJCALLT.2021010104Search in Google Scholar

Moreno, Ana I., and John M. Swales. 2018. “Strengthening Move Analysis Methodology Towards Bridging the Function-Form Gap.” English for Specific Purposes 50: 40–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2017.11.006.Search in Google Scholar

Mukherjee, Joybrato. 2006. “Corpus Linguistics and Language Pedagogy: The State of The Art–and Beyond.” In Corpus Technology and Language Pedagogy, edited by S. Bruan, K. Kohn, and J. Mukherjee, 5–24. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Omidian, Taha, Hesamoddin Shahriari, and Anna Siyanova-Chanturia. 2018. “A Cross- Disciplinary Investigation of Multi-Word Expressions in the Moves of Research Article Abstracts.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 36: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2018.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

Polio, Charlene. 2017. “Second Language Writing Development: A Research Agenda.” Language Teaching 50 (2): 261–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000015.Search in Google Scholar

Poole, Robert. 2016. “A Corpus-Aided Approach for the Teaching and Learning of Rhetoric in an Undergraduate Composition Course for L2 Writers.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 21: 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Römer, Ute. 2008. “Using General and Specialized Corpora in English Language Teaching: Past, Present, and Future.” In Corpus-based Approaches to English Language Teaching, edited by M. C. Campoy-Cubillo, B. Bellés-Fortuño, and M. L. Gea-Valor, 18–35. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

Römer, Ute. 2011. “Corpus Research Applications in Second Language Teaching.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 31: 205–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190511000055.Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, John. 1987. Looking Up. An Account of the COBUILD Project in Lexical Computing. London: Collins ELT.Search in Google Scholar

Swales, John M. 1990. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Swales, John M. 2004. Research Genres: Explorations and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524827Search in Google Scholar

Swales, John M. 2019. “The Futures of EAP Genre Studies: A Personal Viewpoint.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 38: 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

Tardy, Christine M. 2009. Building Genre Knowledge. Anderson: Parlor Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tomasello, Michael. 2003. Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tribble, Christopher. 1997. Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tribble, Christopher. 2009. “Writing Academic English – A Survey Review of Current Published Resources.” ELT Journal 63 (4): 400–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp073.Search in Google Scholar

Tyler, Andrea E. 2010. “Usage-Based Approaches to Language and Their Applications to Second Language Learning.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 30: 270–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190510000140.Search in Google Scholar

Tyler, Andrea E., and Lourdes Ortega. 2018. “Some Reflection and a Heuristic.” In Usage- Inspired L2 Instruction: Researched Pedagogy, edited by A. E. Ortega, H. I. Park, M. Uno, and L. Ortega, 315–21. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/lllt.49.14tylSearch in Google Scholar

Tyler, Andrea E., Hae In Park, Mariko Uno, and Lourdes Ortega, eds. 2018. Usage-Inspired L2 Instruction: Researched Pedagogy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/lllt.49Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Yuanheng (Arthur). 2023. “Demystifying Academic Promotional Genre: A Rhetorical Move-Step Analysis of Teaching Philosophy Statements (TPSs).” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 65: 101284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101284.Search in Google Scholar

Wulff, Stepanie, and Nick C. Ellis. 2018. “Usage-Based Approaches to Second Language Acquisition.” In Bilingual Cognition and Language: The State of the Science across its Subfields, edited by D. Miller, F. Bayram, J. Rothman, and L. Serratrice, 37–56. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/sibil.54.03wulSearch in Google Scholar

Yoon, Jungwan, & Casal, J. Elliott. 2020. P-Frames and Rhetorical Moves in Applied Linguistics Conference Proposals. In U. Römer, V. Cortes, & E. Friginal (Eds.), Advances in Corpus-Based Research on Academic Writing: Effects of Discipline, Register, and Writer Expertise (pp. 282–305). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/scl.95.12yooSearch in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shanghai International Studies University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- A Look at What is Lost: Combining Bibliographic and Corpus Data to Study Clichés of Translation

- Emotion and Ageing in Discourse: Do Older People Express More Positive Emotions?

- Multimodal Mediation in Translation and Communication of Chinese Museum Culture in the Era of Artificial Intelligence

- An Unsupervised Learning Study on International Media Responses Bias to the War in Ukraine

- Parts-of-Speech (PoS) Analysis and Classification of Various Text Genres

- Conceptualizing Corpus-Based Genre Pedagogy as Usage-Inspired Second Language Instruction

- Local Grammar Approach to Investigating Advanced Chinese EFL Learners’ Development of Communicative Competence in Academic Writing: The Case of ‘Exemplification’

- Building an Annotated L1 Arabic/L2 English Bilingual Writer Corpus: The Qatari Corpus of Argumentative Writing (QCAW)

- A Corpus-Assisted Comparative Study of Chinese and Western CEO Statements in Annual Reports: Discourse-Historical Approach

- Corpus-Based Diachronic Analysis on the Representations of China’s Poverty Alleviation in People’s Daily

- Book Reviews

- Anne McCabe: A Functional Linguistic Perspective on Developing Language

- The Linguistic Challenge of the Transition to Secondary School: A Corpus Study of Academic Language by Alice Deignan, Duygu Candarli, and Florence Oxley

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- A Look at What is Lost: Combining Bibliographic and Corpus Data to Study Clichés of Translation

- Emotion and Ageing in Discourse: Do Older People Express More Positive Emotions?

- Multimodal Mediation in Translation and Communication of Chinese Museum Culture in the Era of Artificial Intelligence

- An Unsupervised Learning Study on International Media Responses Bias to the War in Ukraine

- Parts-of-Speech (PoS) Analysis and Classification of Various Text Genres

- Conceptualizing Corpus-Based Genre Pedagogy as Usage-Inspired Second Language Instruction

- Local Grammar Approach to Investigating Advanced Chinese EFL Learners’ Development of Communicative Competence in Academic Writing: The Case of ‘Exemplification’

- Building an Annotated L1 Arabic/L2 English Bilingual Writer Corpus: The Qatari Corpus of Argumentative Writing (QCAW)

- A Corpus-Assisted Comparative Study of Chinese and Western CEO Statements in Annual Reports: Discourse-Historical Approach

- Corpus-Based Diachronic Analysis on the Representations of China’s Poverty Alleviation in People’s Daily

- Book Reviews

- Anne McCabe: A Functional Linguistic Perspective on Developing Language

- The Linguistic Challenge of the Transition to Secondary School: A Corpus Study of Academic Language by Alice Deignan, Duygu Candarli, and Florence Oxley