Abstract

During the course of an outbreak due to Verona integron-encoded Metallo-β-lactamase (VIM)-producing Klebsiella pneumonia (KP) in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Maggiore Hospital in Bologna (Italy), an 8-day-old extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infant developed a severe ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) with concomitant bacteraemia. Although the microorganism was susceptible only to colistin and tigecycline, the patient was successfully treated with a combination of antibiotics including high-dosage, prolonged infusion of meropenem (MEM) and intravenous plus aerosolised gentamicin (GEN). This report highlights that, even when the microorganism is considered non-susceptible to MEM and GEN, the combination of these two agents could have a significant survival benefit.

Introduction

In Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP), acquired resistance to penicillins, broad spectrum cephalosporins, and monobactams can be mediated by the production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs). Carbapenems or fluoroquinolones are commonly used to treat clinical infections caused by these organisms. More recently, resistance to carbapenems, particularly Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC) and class B metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), has emerged. The dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumonia (CPKP) is worrying as these species cause infections that are difficult to treat, have high mortality rates and are typically healthcare-associated [1]. Although most of these infections are reported in geriatric patients with underlying comorbidities, neonates in the neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are also at risk of colonisation and infection by carbapenemase-producing strains. Furthermore, an increasing number of NICU outbreaks, with high morbidity and mortality rate, are currently being reported worldwide [2]. The microorganisms colonise the digestive tract of patients and are spread by the hospital staff. Additionally, colonised mothers could represent a source of transmission to neonates, for the most part after recent hospitalisation or prolonged antibiotic therapy [3]. Low gestational age, low birth weight, duration of staying in the wards, assisted ventilation, presence of central venous catheters and previous antibiotic exposure have all been identified as significant risk factors for acquiring multidrug-resistant KP in NICUs [2]. Between August and October 2017, an outbreak due to a VIM-producing KP occurred in the NICU at Maggiore Hospital in Bologna, Italy. The index patient was a 35-day-old infant who had been transferred from the paediatric surgical ward. His rectal surveillance swab on admission was positive for VIM-producing KP. Over the next few weeks, despite the implementation of the standard infection control procedures, an additional seven patients were colonised and one extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infant developed ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) with concomitant bacteraemia.

Case report

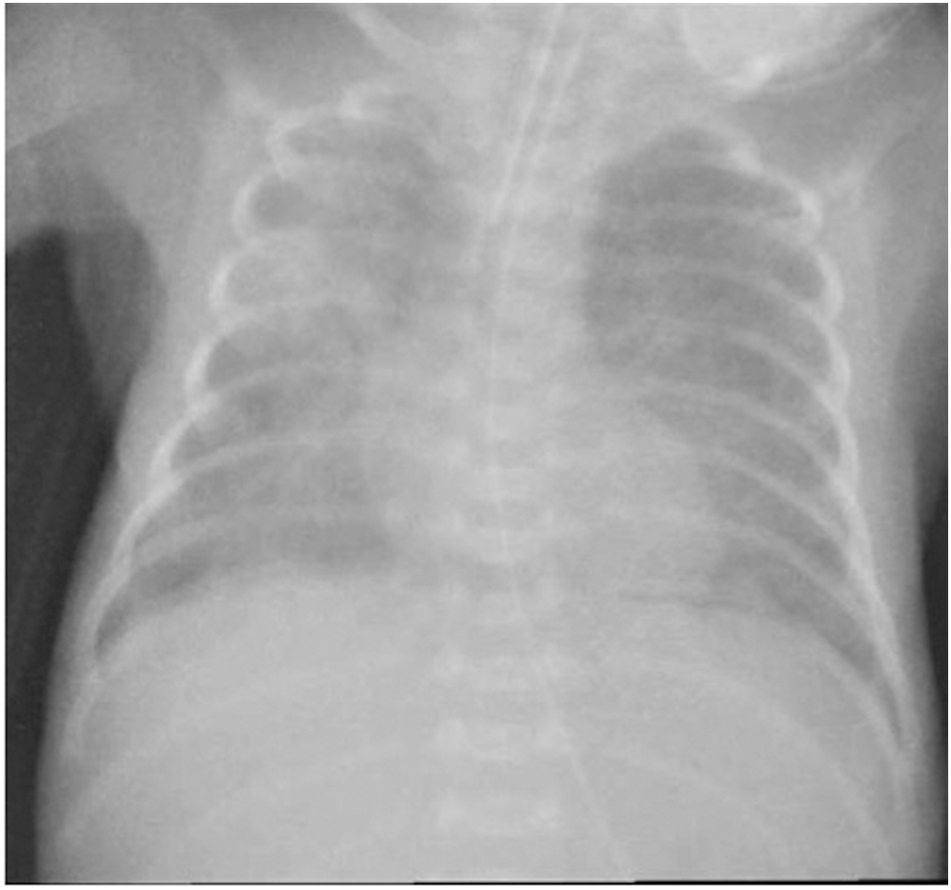

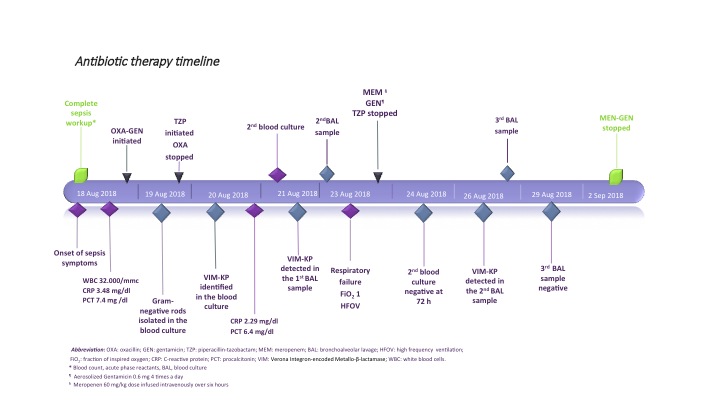

A 38-year-old woman (gravida 1, para 0) with threatening preterm labour was admitted to our hospital at 24+1 weeks’ gestation. The pregnancy was the result of “in vitro” fertilisation. Two doses of betamethasone were administered at the time of admission. The woman delivered a baby girl at 25 weeks and 1 day of gestation by spontaneous vaginal delivery. The baby was intubated in the delivery room for apnoea and admitted to our level III NICU for further management. Apgar scores were 5 at 1 min, and 7 at 5 min, respectively. Growth parameters at birth were: weight 750 g (72nd centile), length 33 cm (72nd centile) and head circumference 22.8 cm (36th centile). A chest radiograph revealed severe hyaline membrane disease. Surfactant, 200 mg/kg (Curosurf®, Chiesi Pharmaceutical, Parma, Italy), was administered and mechanical ventilation was initiated. After obtaining specimens for blood culture, empirical treatment with ampicillin and gentamicin (GEN) was started. The first blood culture was sterile at 48 h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was <0.5 mg/dL (normal value <0.5 mg/dL), therefore ampicillin and GEN were discontinued. On the 5th day of life, oxygen requirement increased, and a hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosous (PDA) was diagnosed. A course of ibuprofen was administered and a repeat echocardiogram confirmed the closed PDA. Extubation was unsuccessfully attempted on postnatal day 7. The following day, the baby started to show clinical decompensation with increasingly frequent desaturations, and decreased gas exchange. Conventional mechanical ventilation was shifted to high frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV). The peripheral white blood count was 32 x 109/L (neutrophils 0.58), the CRP level was 3.48 mg/dL, and the procalcitonin level 7.4 mg/dL (normal value <0.5 mg/dL). Blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) for analysis and culture were obtained and therapy with oxacillin (OXA) and GEN was initiated. Lumbar puncture was not performed because of the baby’s severe respiratory status. Echocardiography revealed no residual ductal shunting. Pulmonary X-ray showed asymmetric multifocal areas of opacity bilaterally (Figure 1). After 10 h of incubation, a blood culture bottle was flagged as positive and Gram staining showed Gram-negative rods. OXA was discontinued, and piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP) was added while awaiting culture identification and sensitivity. The central venous catheter was immediately replaced in order to eradicate the catheter-related bacteraemia. Blood culture and BAL samples demonstrated a VIM-producing KP. The isolates were susceptible only to tigecycline and colistin and resistant to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones and all the β-lactam antibiotics tested (Table 1). Species identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed using VitekMS matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (Maldi-TOF) (bioMerieux, Craponne, France) and Vitek2 (bioMerieux), respectively. Molecular identification of the carbapenemase gene was obtained by Xpert Carba-R (Cepheid). As the baby’s laboratory tests and clinical condition had improved at first the antibiotic treatment was not changed based on the antibiogram. On day 5 of therapy, the respiratory status deteriorated and the patient developed severe hypoxaemia and hypercapnia despite maximal ventilatory support. A chest radiograph revealed an extensive airspace infiltration in the right middle and lower lobes. A dishomogeneous consolidation also involved the left upper lobe (Figure 2). As shown in the antibiotic timeline (Figure 3), the initial antibiotic regimen was modified to meropenem (MEM) (60 mg/kg dose infused intravenously over 6 h, 4 times a day) plus GEN. Additionally, aerosolised GEN (0.6 mg in 2 mL of normal saline 4 times a day) was administered by means of a nebuliser. The new treatment led to a rapid improvement in the patient’s respiratory status and clearing of the strain of K. pneumoniae from the patient’s BAL. She completed 2 weeks of intravenous GEN and 10 days of MEM and nebulised GEN, with good results. Trough serum level of GEN was monitored, and was consistently in the therapeutic range. Complete blood count, serum creatinine and electrolytes were tested every 3 days, and transaminases were evaluated weekly during antibiotic administration. Based on these tests, there was no evidence of any biochemical or haematological toxicity resulting from the treatment. The infant was extubated at day 32 of life. After extubation, the baby remained on nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) for a total of 8 days. Respiratory support (high-flow nasal cannula therapy) was withdrawn completely at 37 weeks and 6 days post-conceptional age, and she started oxygenating well in room air. Sequential ultrasound examinations, including at discharge, did not detect any abnormal findings. There was no severe retinopathy of prematurity, only stage 2 in zone III without plus disease. She was vaccinated and sent home on day 96, weighing 2170 g, with a head circumference of 32 cm, and a length of 43 cm. During hospitalisation, VIM-producing KP was persistently detected in surveillance rectal swabs, but not from other sites. Contact isolation was maintained until the time of discharge from the hospital. A rectal swab obtained from the mother did not show any carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae ruling out the possibility of mother-to-child transmission at birth.

Chest radiograph, 8 days of age, showing asymmetric multifocal areas of opacity.

Susceptibility profile of VIM-producing K. Pneumonia isolates.

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/mL)a | Interpretationb |

|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | ≥32 | R |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | ≥32 | R |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≥128 | R |

| Cefotaxime | ≥64 | R |

| Ceftazidime | ≥64 | R |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≥4 | R |

| Gentamicin | ≥16 | R |

| Amikacin | ≥64 | R |

| Meropenem | ≥16 | R |

| Tigecycline | 1 | S |

| Colistin | 2 | S |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≥320 | R |

-

aMinimal inhibitory concentration, MIC (μg/mL). bInterpretation based on the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints).

Chest radiography, 13 days of life, showing extensive infiltrates in the right middle and lower lobes, and the left upper lobe with air bronchograms.

Antibiotic therapy timeline.

Discussion

Options for treating patients infected with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae are limited because these bacteria develop resistance to almost all classes of conventional antimicrobial agents with a consequent high risk of therapeutic failure [3]. The mechanisms that are involved in carbapenem resistance include the production of carbapenemases, in association with the presence of other types of ESBLs or ampicillin-resistance gene group C (AmpC) cephalosporinases. Expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are not indicated in the treatment of systemic infections caused by these bacteria. Moreover, most isolates are resistant to fluoroquinolones, aminoglicosydes and co-trimoxazole. Several isolates remain susceptible to amikacin and GEN, and most isolates remain susceptible to colistin and tigecycline [1], [3]. Colistin is one of the few agents still active against carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, but there is not enough data about its use and dosage in neonates. In adult patients, parenteral use of colistin has been known to cause renal toxicity. Acute tubular necrosis is the main concern, and haematuria, proteinuria and cylindruria can also occur. Since the less toxic colistimethate sodium became available, this complication is less frequently seen, especially if the simultaneous use of other nephrotoxic drugs is avoided. In the largest series of systemic colistin use in full-term and preterm neonates [4], three patients (4.6%) developed renal toxicity and another three patients (4.6%) had seizures. In all cases, renal function returned to normal after discontinuation of therapy. A similar retrospective study on preterm neonates reported a renal impairment rate of 19%, and an incidence of electrolyte disturbance of 24% [5]. The authors suggested that renal function testing and serum electrolytes should be monitored closely during the colistin parenteral therapy in preterm infants. Furthermore, the increasing use of this antimicrobial agent has led to the emergence of colistin-resistant strains among the population of multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Although chromosomally encoded resistance to colistin was first described long ago, more recently a plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene conferring colistin-resistance has been reported and seems to be spreading all over the world. All these considerations emphasise the importance of limiting colistin use also in NICUs [1], [3]. In the current case, the patient was successfully treated with a combination of antibiotics including high-dosage, prolonged infusion of MEM and intravenous plus aerosolised GEN, although the microorganism was susceptible only to colistin and tigecycline. Several observational studies conducted in recent years have investigated whether carbapenems can be used in the treatment of infections caused by carbapenemase-producing bacteria [6], [7]. Carbapenem activity is unrelated to plasma concentrations, and is dependent on the percentage of time the plasma concentrations are maintained above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the pathogen [6]. More precisely, their time-dependent bactericidal activity is optimised if free drug concentration remain above the MIC for approximately 40–50% of the time between dosing intervals. In order to achieve this objective, the dosage scheme, and/or the infusion times should be modified: higher doses, increased frequency of administration or prolonged duration of infusion have shown to increase antibacterial effectiveness [6]. Depending on the geographical origin of the carbapenemase-producing strains and the type of enzyme, the carbapenem MICs may vary within a broad value range. When the MIC value is low, the isolates might be susceptible to carbapenems in vivo, regardless of the production of carbapenemases. Studies performed on animal infection models have demonstrated that high-dose, prolonged-infusion regimens of carbapenems are able to achieve a bacteriostatic effect in animals infected by isolates with MICs up to 8 mg/L. If the usual 30-min infusion time is used, the drug serum concentration falls below 2 mg/L 5 h after administration. Prolonging the infusion time to 3 h resulted in a serum concentration above 2 mg/L for the whole period between dosages. The concentrations increased to above 4 mg/L when the MEM dose was doubled [6]. Bulik et al. evaluated the efficacy of 1 g and 2 g doses, and prolonged infusion of doripenem against CPKP with MICs ranging from 4 to 32 mg/L. The 1 g dose was able to produce a bacteriostatic response for the isolates with MICs of 4 and 8 mg/L. The 2 g dose achieved a similar effect for isolates with MICs of up to 16 mg/L [8]. Considering that the activity of carbapenems is determined by the length of time that tissue and serum concentrations are above the MIC during the dosing interval, we decided to administer high doses of MEM (60 mg/kg instead of the traditional dose of 20 mg/kg) and prolonged time of infusion (6 h instead of the traditional infusion time of 30 min). When continuous infusion administration of carbapenems is used, consideration should be given to the stability of the drugs. Berthoud et al. [9] demonstrated that the stability of MEM improves if temperature is kept at ≤25°C and solutions ≤4 g/100 mL are used. Both prerequisites were fulfilled in our patient. In addition, carbapenem effectiveness may be enhanced if used in combination with another active agent. When combination therapies containing carbapenems were compared to monotherapy, with either colistin or tigecycline, the combination appeared to be more effective than monotherapy also in patients who received an antibiotic agent that had no in vitro activity against the infecting pathogens [7]. The lowest mortality rate was observed among patients treated with a combination of two drugs, one of which was a carbapenem and the other an aminoglycoside, or colistin, or tigecycline. On the contrary, when carbapenems were used as monotherapy against extensively drug-resistant bacteria, that positive effect was not observed, especially when MICs were ≥16 mg/L [6], [7]. Finally, in our patient, the administration of GEN via the respiratory tract could have played a role in improving respiratory status. If systemically injected, aminoglycosides are not able to penetrate into respiratory secretions in adequate concentrations. By contrast, that class of antibiotics can be delivered efficiently with an aerosol to the lower respiratory tract in mechanically ventilated patients [10]. Thereby, the growth of pathogens can be effectively suppressed and the volume of respiratory secretions significantly reduced. In our patient, the tracheal secretions were negative after 3 days of treatment, and during therapy the baby showed progressive improvement in her overall respiratory status. No adverse effects were observed on respiratory function during the administration of the aerosolised GEN.

Conclusion

Due to its resistance to multiple antibiotics, VIM-producing KP is difficult to control and the infections are difficult to treat, especially in neonates. This descriptive report highlights that, even when the microorganism is considered non-susceptible to MEM and GEN, the combination of these two agents could have a significant survival benefit.

Furthermore, aerosolised antibiotic therapy may have a potential for treating nosocomial pneumonia in neonates.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alexandra Teff for editing the English text.

-

Financial disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

-

Funding: No external funding was obtained.

-

Potential conflict of interest: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

[1] Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Psichogiou M, Tassios PT, Daikos GL. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumonia and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:682–707.10.1128/CMR.05035-11Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Yu F, Ying Q, Chen C, Li T, Ding B, Liu Y, et al. Outbreak of pulmonary infection caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harbouring blaIMP-4 and blaDHA-1 in a neonatal intensive care unit in China. J Med Microbiol. 2012;6:984–9.10.1099/jmm.0.043000-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Folgori L, Bielicki J, Heath PT, Sharland M. Antimicrobial-resistant Gram-negative infections in neonates: burden of disease and challenges in treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30:281–8.10.1097/QCO.0000000000000371Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Cagan E, Bas EK, Asker HS. Use of colistin in a neonatal intensive care unit: a cohort study of 65 patients. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:548–54.10.12659/MSM.898213Search in Google Scholar

[5] Alan S, Yildiz D, Erdeve O, Cakir U, Kahvecioglu D, Okulu E, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous colistin in preterm infants with nosocomial sepsis caused by Acinetobacter baumanni. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:1079–86.10.1055/s-0034-1371361Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Daikos GL, Morkogiannakis A. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumonia: (when) might we still consider treating with carbapenems? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1135–41.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03553.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Hirsch EB, Guo B, Chang KT, Cao H, Ledesma KR, Singh M, et al. Assessment of antimicrobial combinations for Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:786–93.10.1093/infdis/jis766Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Bulik CC, Christensen H, Li P, Sutherland CA, Nicolau DP, Kuti JL. Comparison of activity of a human simulated, high-dose, prolonged infusion of meropenem against Klebsiella pneumoniae producing the KCP carbapenemase versus that against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:804–10.10.1128/AAC.01190-09Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Berthoud K, Le Duff CS, Marchand-Brynaert J, Carryn S, Tulkens PM. Stability of meropenem and doripenem solutions for administration by continuous infusion. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1073–5.10.1093/jac/dkq044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Ioannidou E, Siempios II, Falagas ME. Administration of antimicrobials via respiratory tract for the treatment of patients with nosocomial pneumonia: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:1216–26.10.1093/jac/dkm385Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Case Reports – Obstetrics

- Trisomy 9 presenting in the first trimester as a fetal lateral neck cyst and increased nuchal translucency

- A case of intrauterine closure of the ductus arteriosus and non-immune hydrops

- Pregnancy luteoma: a rare presentation and expectant management

- A pregnant woman with an operated bladder extrophy and a pregnancy complicated by placenta previa and preterm labor

- Consecutive successful pregnancies of a patient with nail-patella syndrome

- A multidisciplinary management approach for patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and multifetal gestation with successful outcomes

- A uterus didelphys with a spontaneous labor at term of pregnancy: a rare case and a review of the literature

- Case Reports – Fetus

- Prenatal diagnosis of ring chromosome 13: a rare chromosomal aberration

- Case Reports – Newborn

- Late-onset pubic-phallic idiopathic edema in premature recovering infants

- An unusual cause of neonatal shock: a case report

- Early ultrasonographic follow up in neonatal pneumatocele. Two case reports

- Nonsyndromic extremely premature eruption of teeth in preterm neonates – a report of three cases and a review of the literature

- Successful outcome of a preterm infant with severe oligohydramnios and suspected pulmonary hypoplasia following premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) at 18 weeks’ gestation

- Onset of Kawasaki disease immediately after birth

- Short rib-polydactyly syndrome (Saldino-Noonan type) undetected by standard prenatal genetic testing

- Severe congenital autoimmune neutropenia in preterm monozygotic twins: case series and literature review

- Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis in an extremely premature infant

Articles in the same Issue

- Case Reports – Obstetrics

- Trisomy 9 presenting in the first trimester as a fetal lateral neck cyst and increased nuchal translucency

- A case of intrauterine closure of the ductus arteriosus and non-immune hydrops

- Pregnancy luteoma: a rare presentation and expectant management

- A pregnant woman with an operated bladder extrophy and a pregnancy complicated by placenta previa and preterm labor

- Consecutive successful pregnancies of a patient with nail-patella syndrome

- A multidisciplinary management approach for patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and multifetal gestation with successful outcomes

- A uterus didelphys with a spontaneous labor at term of pregnancy: a rare case and a review of the literature

- Case Reports – Fetus

- Prenatal diagnosis of ring chromosome 13: a rare chromosomal aberration

- Case Reports – Newborn

- Late-onset pubic-phallic idiopathic edema in premature recovering infants

- An unusual cause of neonatal shock: a case report

- Early ultrasonographic follow up in neonatal pneumatocele. Two case reports

- Nonsyndromic extremely premature eruption of teeth in preterm neonates – a report of three cases and a review of the literature

- Successful outcome of a preterm infant with severe oligohydramnios and suspected pulmonary hypoplasia following premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) at 18 weeks’ gestation

- Onset of Kawasaki disease immediately after birth

- Short rib-polydactyly syndrome (Saldino-Noonan type) undetected by standard prenatal genetic testing

- Severe congenital autoimmune neutropenia in preterm monozygotic twins: case series and literature review

- Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis in an extremely premature infant